User login

Study links severe childhood eczema to sedentary behaviors

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Children with severe atopic dermatitis were significantly more likely to log at least 5 hours of screen time a day, and were significantly less likely to exercise than were nonatopic controls, said the lead investigator of a large national study.

“Atopic dermatitis overall was not associated with sedentary behavior. It was severe disease only,” said Mark Strom of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Patients tended to be even more sedentary if they suffered from disturbed sleep in addition to severe eczema, he added.

Heat and sweat worsen the intense itch of atopic dermatitis. Hypothesizing that this would deter affected children from physical activity, Mr. Strom and his associates analyzed data for 131,783 respondents aged 18 and under from the National Survey of Children’s Health. The survey assesses physical activity by asking how many days a week the respondent sweated and breathed hard for at least 20 minutes. Screen time is measured by asking about daily hours spent watching television and playing video games, and sleep quality is assessed by asking how many nights a week the child slept the normal amount for his or her age.

Simply having atopic dermatitis was linked with only a slight increase in the chance of having a sedentary lifestyle after controlling for demographic factors, insurance status, geographic location, and educational level, according to Mr. Strom. Specifically, eczema was significantly associated with a 12% lower odds of having exercised on at least 3 days of the previous week (odds ratio, 0.88). However, severe atopic dermatitis significantly reduced the odds that a child exercised at least one day a week by 61% (OR, 0.39). Furthermore, severe atopic dermatitis was associated with more than double the odds of having at least 5 hours of daily screen time (OR, 2.62). And having either moderate or severe eczema was tied to a significant decrease in the odds of having participated in sports in the past year, Mr. Strom said.

“Atopic dermatitis and sleep disturbance each contribute to sedentary behavior,” he reported. Nonatopic children who did not sleep enough on most nights had nearly double the odds of heavy television and video game use, compared with children who slept more, a significant difference. When poor sleepers also had atopic dermatitis, their odds of heavy screen use more than tripled. Poor sleepers were also significantly less likely to join sports teams, even when they did not have eczema, Mr. Strom said.

“Children with more severe atopic dermatitis may have more profound exacerbations of activity-related symptoms, which would lead to these findings,” he concluded. Future studies should explore whether better symptom control can help improve sedentary behaviors, he added.

The study was sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mr. Strom had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Children with severe atopic dermatitis were significantly more likely to log at least 5 hours of screen time a day, and were significantly less likely to exercise than were nonatopic controls, said the lead investigator of a large national study.

“Atopic dermatitis overall was not associated with sedentary behavior. It was severe disease only,” said Mark Strom of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Patients tended to be even more sedentary if they suffered from disturbed sleep in addition to severe eczema, he added.

Heat and sweat worsen the intense itch of atopic dermatitis. Hypothesizing that this would deter affected children from physical activity, Mr. Strom and his associates analyzed data for 131,783 respondents aged 18 and under from the National Survey of Children’s Health. The survey assesses physical activity by asking how many days a week the respondent sweated and breathed hard for at least 20 minutes. Screen time is measured by asking about daily hours spent watching television and playing video games, and sleep quality is assessed by asking how many nights a week the child slept the normal amount for his or her age.

Simply having atopic dermatitis was linked with only a slight increase in the chance of having a sedentary lifestyle after controlling for demographic factors, insurance status, geographic location, and educational level, according to Mr. Strom. Specifically, eczema was significantly associated with a 12% lower odds of having exercised on at least 3 days of the previous week (odds ratio, 0.88). However, severe atopic dermatitis significantly reduced the odds that a child exercised at least one day a week by 61% (OR, 0.39). Furthermore, severe atopic dermatitis was associated with more than double the odds of having at least 5 hours of daily screen time (OR, 2.62). And having either moderate or severe eczema was tied to a significant decrease in the odds of having participated in sports in the past year, Mr. Strom said.

“Atopic dermatitis and sleep disturbance each contribute to sedentary behavior,” he reported. Nonatopic children who did not sleep enough on most nights had nearly double the odds of heavy television and video game use, compared with children who slept more, a significant difference. When poor sleepers also had atopic dermatitis, their odds of heavy screen use more than tripled. Poor sleepers were also significantly less likely to join sports teams, even when they did not have eczema, Mr. Strom said.

“Children with more severe atopic dermatitis may have more profound exacerbations of activity-related symptoms, which would lead to these findings,” he concluded. Future studies should explore whether better symptom control can help improve sedentary behaviors, he added.

The study was sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mr. Strom had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Children with severe atopic dermatitis were significantly more likely to log at least 5 hours of screen time a day, and were significantly less likely to exercise than were nonatopic controls, said the lead investigator of a large national study.

“Atopic dermatitis overall was not associated with sedentary behavior. It was severe disease only,” said Mark Strom of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Patients tended to be even more sedentary if they suffered from disturbed sleep in addition to severe eczema, he added.

Heat and sweat worsen the intense itch of atopic dermatitis. Hypothesizing that this would deter affected children from physical activity, Mr. Strom and his associates analyzed data for 131,783 respondents aged 18 and under from the National Survey of Children’s Health. The survey assesses physical activity by asking how many days a week the respondent sweated and breathed hard for at least 20 minutes. Screen time is measured by asking about daily hours spent watching television and playing video games, and sleep quality is assessed by asking how many nights a week the child slept the normal amount for his or her age.

Simply having atopic dermatitis was linked with only a slight increase in the chance of having a sedentary lifestyle after controlling for demographic factors, insurance status, geographic location, and educational level, according to Mr. Strom. Specifically, eczema was significantly associated with a 12% lower odds of having exercised on at least 3 days of the previous week (odds ratio, 0.88). However, severe atopic dermatitis significantly reduced the odds that a child exercised at least one day a week by 61% (OR, 0.39). Furthermore, severe atopic dermatitis was associated with more than double the odds of having at least 5 hours of daily screen time (OR, 2.62). And having either moderate or severe eczema was tied to a significant decrease in the odds of having participated in sports in the past year, Mr. Strom said.

“Atopic dermatitis and sleep disturbance each contribute to sedentary behavior,” he reported. Nonatopic children who did not sleep enough on most nights had nearly double the odds of heavy television and video game use, compared with children who slept more, a significant difference. When poor sleepers also had atopic dermatitis, their odds of heavy screen use more than tripled. Poor sleepers were also significantly less likely to join sports teams, even when they did not have eczema, Mr. Strom said.

“Children with more severe atopic dermatitis may have more profound exacerbations of activity-related symptoms, which would lead to these findings,” he concluded. Future studies should explore whether better symptom control can help improve sedentary behaviors, he added.

The study was sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mr. Strom had no disclosures.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A large national study linked severe atopic dermatitis to sedentary behaviors and screen time.

Major finding: Compared with children without eczema, those with severe disease were about 60% less likely to exercise at least once a week (OR, 0.39).

Data source: An analysis of data for 131,783 children from the National Survey of Children’s Health.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mr. Strom had no disclosures.

Nonwhite race, lower socioeconomic status predicts persistently active AD

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. –Among patients with atopic dermatitis, persistently active disease was significantly more common among females of nonwhite race with a history of atopy than among patients without these characteristics, in an analysis of survey data from the Pediatric Elective Eczema Registry.

Annual household income under $50,000 also was a significant predictor of persistently active eczema, according to Katrina Abuabara, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates, who reported their results in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis often persists into adulthood, but few studies have explored contributors to poor disease control. To help fill that gap, the investigators analyzed 65,237 surveys from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), which tracks children and young adults aged 2-26 years with physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis. The average age of the 6,237 patients was 7 years at enrollment (standard deviation, 4 years). They were followed at 6-month intervals for up to 10 years, with an average of about 10 surveys per respondent (standard deviation, 6.3 surveys).

In all, 4,607 patients (74% of the cohort) returned surveys spanning early childhood through their mid-20s. Only 15% of patients had “resolving” disease, meaning that as they aged, they increasingly reported complete disease control for periods of 6 months and longer.

The remaining 85% of patients had persistently active disease. In this group, 54% were female, 77% had a household income under $50,000 per year, 71% were nonwhite, and 75% had a history of atopy. Each of these characteristics significantly increased the odds of persistently active atopic dermatitis in the multivariable model (P less than .05 for each association).

Nonwhite race and history of atopy were the strongest predictors of persistently active disease – each lowered the odds of complete disease control by almost 50% (odds ratio, 0.53). Furthermore, females had 37% lower odds of complete disease control compared with males (OR, 0.63), and individuals with household income under $50,000 had 16% lower odds of complete disease control compared with those with higher annual incomes (OR, 0.84).

The link between lower socioeconomic status and persistently active eczema belies previous findings, the researchers noted. Those studies found that individuals of higher socioeconomic status were at greater risk for developing atopic dermatitis, but “failed to account for the chronic nature of the disease. In contrast, our results suggest that atopic dermatitis persistence may be associated with lower income and nonwhite race, and highlight the importance of longitudinal studies that permit analysis of mechanisms of disease control over time.”

Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. –Among patients with atopic dermatitis, persistently active disease was significantly more common among females of nonwhite race with a history of atopy than among patients without these characteristics, in an analysis of survey data from the Pediatric Elective Eczema Registry.

Annual household income under $50,000 also was a significant predictor of persistently active eczema, according to Katrina Abuabara, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates, who reported their results in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis often persists into adulthood, but few studies have explored contributors to poor disease control. To help fill that gap, the investigators analyzed 65,237 surveys from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), which tracks children and young adults aged 2-26 years with physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis. The average age of the 6,237 patients was 7 years at enrollment (standard deviation, 4 years). They were followed at 6-month intervals for up to 10 years, with an average of about 10 surveys per respondent (standard deviation, 6.3 surveys).

In all, 4,607 patients (74% of the cohort) returned surveys spanning early childhood through their mid-20s. Only 15% of patients had “resolving” disease, meaning that as they aged, they increasingly reported complete disease control for periods of 6 months and longer.

The remaining 85% of patients had persistently active disease. In this group, 54% were female, 77% had a household income under $50,000 per year, 71% were nonwhite, and 75% had a history of atopy. Each of these characteristics significantly increased the odds of persistently active atopic dermatitis in the multivariable model (P less than .05 for each association).

Nonwhite race and history of atopy were the strongest predictors of persistently active disease – each lowered the odds of complete disease control by almost 50% (odds ratio, 0.53). Furthermore, females had 37% lower odds of complete disease control compared with males (OR, 0.63), and individuals with household income under $50,000 had 16% lower odds of complete disease control compared with those with higher annual incomes (OR, 0.84).

The link between lower socioeconomic status and persistently active eczema belies previous findings, the researchers noted. Those studies found that individuals of higher socioeconomic status were at greater risk for developing atopic dermatitis, but “failed to account for the chronic nature of the disease. In contrast, our results suggest that atopic dermatitis persistence may be associated with lower income and nonwhite race, and highlight the importance of longitudinal studies that permit analysis of mechanisms of disease control over time.”

Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. –Among patients with atopic dermatitis, persistently active disease was significantly more common among females of nonwhite race with a history of atopy than among patients without these characteristics, in an analysis of survey data from the Pediatric Elective Eczema Registry.

Annual household income under $50,000 also was a significant predictor of persistently active eczema, according to Katrina Abuabara, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates, who reported their results in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis often persists into adulthood, but few studies have explored contributors to poor disease control. To help fill that gap, the investigators analyzed 65,237 surveys from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), which tracks children and young adults aged 2-26 years with physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis. The average age of the 6,237 patients was 7 years at enrollment (standard deviation, 4 years). They were followed at 6-month intervals for up to 10 years, with an average of about 10 surveys per respondent (standard deviation, 6.3 surveys).

In all, 4,607 patients (74% of the cohort) returned surveys spanning early childhood through their mid-20s. Only 15% of patients had “resolving” disease, meaning that as they aged, they increasingly reported complete disease control for periods of 6 months and longer.

The remaining 85% of patients had persistently active disease. In this group, 54% were female, 77% had a household income under $50,000 per year, 71% were nonwhite, and 75% had a history of atopy. Each of these characteristics significantly increased the odds of persistently active atopic dermatitis in the multivariable model (P less than .05 for each association).

Nonwhite race and history of atopy were the strongest predictors of persistently active disease – each lowered the odds of complete disease control by almost 50% (odds ratio, 0.53). Furthermore, females had 37% lower odds of complete disease control compared with males (OR, 0.63), and individuals with household income under $50,000 had 16% lower odds of complete disease control compared with those with higher annual incomes (OR, 0.84).

The link between lower socioeconomic status and persistently active eczema belies previous findings, the researchers noted. Those studies found that individuals of higher socioeconomic status were at greater risk for developing atopic dermatitis, but “failed to account for the chronic nature of the disease. In contrast, our results suggest that atopic dermatitis persistence may be associated with lower income and nonwhite race, and highlight the importance of longitudinal studies that permit analysis of mechanisms of disease control over time.”

Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Persistently active atopic dermatitis is associated with nonwhite race, annual household income under $50,000, female sex, and history of atopy.

Major finding: Nonwhite race and history of atopy each lowered the odds of complete disease control by about 43% (odds ratios, 0.53; P less than .05).

Data source: A longitudinal cohort study of 6,237 patients aged 2-26 years from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER).

Disclosures: Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

Nonwhite race, lower socioeconomic status predicts persistently active AD

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. –Among patients with atopic dermatitis, persistently active disease was significantly more common among females of nonwhite race with a history of atopy than among patients without these characteristics, in an analysis of survey data from the Pediatric Elective Eczema Registry.

Annual household income under $50,000 also was a significant predictor of persistently active eczema, according to Katrina Abuabara, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates, who reported their results in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis often persists into adulthood, but few studies have explored contributors to poor disease control. To help fill that gap, the investigators analyzed 65,237 surveys from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), which tracks children and young adults aged 2-26 years with physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis. The average age of the 6,237 patients was 7 years at enrollment (standard deviation, 4 years). They were followed at 6-month intervals for up to 10 years, with an average of about 10 surveys per respondent (standard deviation, 6.3 surveys).

In all, 4,607 patients (74% of the cohort) returned surveys spanning early childhood through their mid-20s. Only 15% of patients had “resolving” disease, meaning that as they aged, they increasingly reported complete disease control for periods of 6 months and longer.

The remaining 85% of patients had persistently active disease. In this group, 54% were female, 77% had a household income under $50,000 per year, 71% were nonwhite, and 75% had a history of atopy. Each of these characteristics significantly increased the odds of persistently active atopic dermatitis in the multivariable model (P less than .05 for each association).

Nonwhite race and history of atopy were the strongest predictors of persistently active disease – each lowered the odds of complete disease control by almost 50% (odds ratio, 0.53). Furthermore, females had 37% lower odds of complete disease control compared with males (OR, 0.63), and individuals with household income under $50,000 had 16% lower odds of complete disease control compared with those with higher annual incomes (OR, 0.84).

The link between lower socioeconomic status and persistently active eczema belies previous findings, the researchers noted. Those studies found that individuals of higher socioeconomic status were at greater risk for developing atopic dermatitis, but “failed to account for the chronic nature of the disease. In contrast, our results suggest that atopic dermatitis persistence may be associated with lower income and nonwhite race, and highlight the importance of longitudinal studies that permit analysis of mechanisms of disease control over time.”

Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. –Among patients with atopic dermatitis, persistently active disease was significantly more common among females of nonwhite race with a history of atopy than among patients without these characteristics, in an analysis of survey data from the Pediatric Elective Eczema Registry.

Annual household income under $50,000 also was a significant predictor of persistently active eczema, according to Katrina Abuabara, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates, who reported their results in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis often persists into adulthood, but few studies have explored contributors to poor disease control. To help fill that gap, the investigators analyzed 65,237 surveys from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), which tracks children and young adults aged 2-26 years with physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis. The average age of the 6,237 patients was 7 years at enrollment (standard deviation, 4 years). They were followed at 6-month intervals for up to 10 years, with an average of about 10 surveys per respondent (standard deviation, 6.3 surveys).

In all, 4,607 patients (74% of the cohort) returned surveys spanning early childhood through their mid-20s. Only 15% of patients had “resolving” disease, meaning that as they aged, they increasingly reported complete disease control for periods of 6 months and longer.

The remaining 85% of patients had persistently active disease. In this group, 54% were female, 77% had a household income under $50,000 per year, 71% were nonwhite, and 75% had a history of atopy. Each of these characteristics significantly increased the odds of persistently active atopic dermatitis in the multivariable model (P less than .05 for each association).

Nonwhite race and history of atopy were the strongest predictors of persistently active disease – each lowered the odds of complete disease control by almost 50% (odds ratio, 0.53). Furthermore, females had 37% lower odds of complete disease control compared with males (OR, 0.63), and individuals with household income under $50,000 had 16% lower odds of complete disease control compared with those with higher annual incomes (OR, 0.84).

The link between lower socioeconomic status and persistently active eczema belies previous findings, the researchers noted. Those studies found that individuals of higher socioeconomic status were at greater risk for developing atopic dermatitis, but “failed to account for the chronic nature of the disease. In contrast, our results suggest that atopic dermatitis persistence may be associated with lower income and nonwhite race, and highlight the importance of longitudinal studies that permit analysis of mechanisms of disease control over time.”

Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. –Among patients with atopic dermatitis, persistently active disease was significantly more common among females of nonwhite race with a history of atopy than among patients without these characteristics, in an analysis of survey data from the Pediatric Elective Eczema Registry.

Annual household income under $50,000 also was a significant predictor of persistently active eczema, according to Katrina Abuabara, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of California, San Francisco, and her associates, who reported their results in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Atopic dermatitis often persists into adulthood, but few studies have explored contributors to poor disease control. To help fill that gap, the investigators analyzed 65,237 surveys from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), which tracks children and young adults aged 2-26 years with physician-diagnosed atopic dermatitis. The average age of the 6,237 patients was 7 years at enrollment (standard deviation, 4 years). They were followed at 6-month intervals for up to 10 years, with an average of about 10 surveys per respondent (standard deviation, 6.3 surveys).

In all, 4,607 patients (74% of the cohort) returned surveys spanning early childhood through their mid-20s. Only 15% of patients had “resolving” disease, meaning that as they aged, they increasingly reported complete disease control for periods of 6 months and longer.

The remaining 85% of patients had persistently active disease. In this group, 54% were female, 77% had a household income under $50,000 per year, 71% were nonwhite, and 75% had a history of atopy. Each of these characteristics significantly increased the odds of persistently active atopic dermatitis in the multivariable model (P less than .05 for each association).

Nonwhite race and history of atopy were the strongest predictors of persistently active disease – each lowered the odds of complete disease control by almost 50% (odds ratio, 0.53). Furthermore, females had 37% lower odds of complete disease control compared with males (OR, 0.63), and individuals with household income under $50,000 had 16% lower odds of complete disease control compared with those with higher annual incomes (OR, 0.84).

The link between lower socioeconomic status and persistently active eczema belies previous findings, the researchers noted. Those studies found that individuals of higher socioeconomic status were at greater risk for developing atopic dermatitis, but “failed to account for the chronic nature of the disease. In contrast, our results suggest that atopic dermatitis persistence may be associated with lower income and nonwhite race, and highlight the importance of longitudinal studies that permit analysis of mechanisms of disease control over time.”

Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Persistently active atopic dermatitis is associated with nonwhite race, annual household income under $50,000, female sex, and history of atopy.

Major finding: Nonwhite race and history of atopy each lowered the odds of complete disease control by about 43% (odds ratios, 0.53; P less than .05).

Data source: A longitudinal cohort study of 6,237 patients aged 2-26 years from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER).

Disclosures: Dr. Abuabara received a grant from the Clinical & Translational Science Institute of UCSF. She had no disclosures.

Febrile, Immunocompromised Man With Rash

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

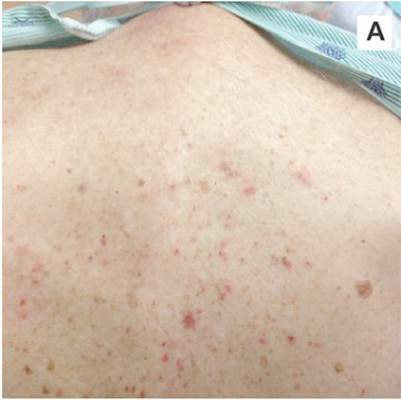

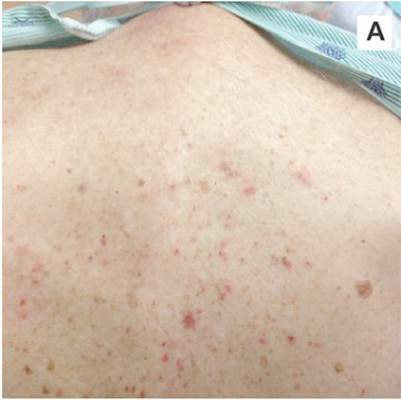

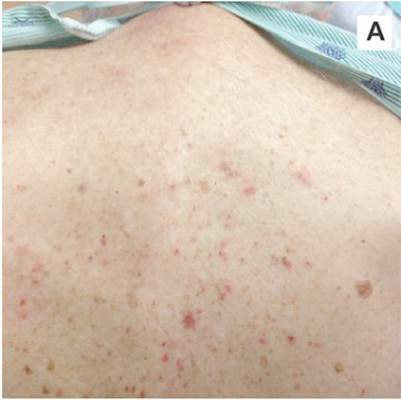

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

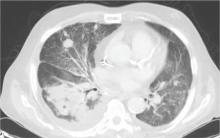

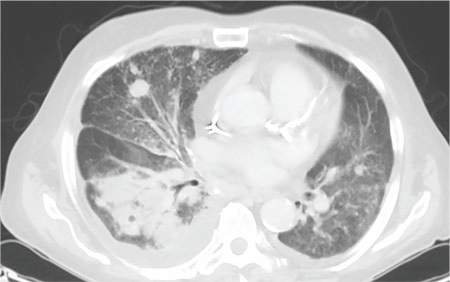

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|  |

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

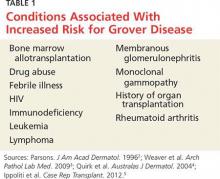

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

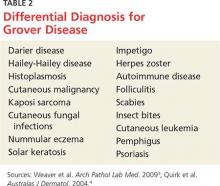

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|  |

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|  |

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

The Promise of Peanut Allergy Prevention Lies in Draft Guidelines

Updated guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for the early introduction of peanut-containing foods to children at increased risk for peanut allergies are on the horizon, pending final approval.

“Two studies recently showed that infants at high risk of developing peanut allergy [infants with egg allergy and or severe eczema] were much less likely to have peanut allergy at age 5 years if they were able to incorporate peanut regularly into the diet between 4 and 11 months of age,” said Dr. Scott H. Sicherer, the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Professor of Pediatrics, Allergy and Immunology, and chief of the division of allergy and immunology in the department of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“However, adding peanut to the diet at this age requires caution because these infants may already be allergic to peanut, and so allergy testing and care in adding peanut to the diet with medical supervision is needed in this high-risk group,” noted Dr. Sicherer, a member of the expert panel that worked on the guidelines.

The draft guidelines include 43 clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies in children, according to the NIAID website. In particular, the draft guidelines recommend introducing peanut-containing foods to infants aged 4-6 months who are at increased risk for peanut allergy because of severe eczema and/or egg allergies, after an evaluation with skin prick testing or peanut-specific IgE testing.

“Peanut allergy is relatively common and often persistent, and so a strategy that could prevent the allergy is very important,” Dr. Sicherer said in an interview. “However, peanut can be a choking hazard as peanuts or peanut butter, and so families should talk to their pediatrician about how and when to incorporate peanut into the diet, and whether allergy testing and referral to an allergist is needed.”

Support for the guidelines comes from several large studies with promising results, notably the LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) trial. A recent extension of that study, known as LEAP-On (Persistence of Oral Tolerance to Peanut), showed that regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to 5 years provided ongoing protection against allergies, even 6 years after peanut consumption was discontinued for a 1-year period in 550 children (N Eng J Med. 2016 Apr 14;374:1435-43).

In the original LEAP study, 640 infants aged 4-11 months with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both were randomized to dietary peanut consumption or avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372[9]:803-13). The prevalence of peanut allergy at 5 years of age was approximately 2% in the peanut-consumption group, compared with 14% in the peanut-avoidance group.

Another significant randomized trial, the EAT study (Enquiring About Tolerance) tested not only peanut, but also the early introduction of cooked egg, cow’s milk, sesame, wheat, and fish to 1,303 infants aged 3 months and older in the general population. The study’s strict protocol made adherence difficult, but researchers found a significant 67% reduction in the prevalence of food allergies at age 3 years among the children who followed the protocol, compared with controls, with relative risk reductions of 100% and 75%, respectively, for peanut and egg allergies (N Engl J Med. 2016 May 5;374:1733-43).

The next steps for research should make early introduction of peanut-containing foods even more effective at allergy prevention, Dr. Sicherer noted.

“We need to learn more about how much peanut should be incorporated into the diet, how long the protein has to be kept in the diet to have the best preventative effect, and whether this strategy applies to other foods,” he said.

Updated guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for the early introduction of peanut-containing foods to children at increased risk for peanut allergies are on the horizon, pending final approval.

“Two studies recently showed that infants at high risk of developing peanut allergy [infants with egg allergy and or severe eczema] were much less likely to have peanut allergy at age 5 years if they were able to incorporate peanut regularly into the diet between 4 and 11 months of age,” said Dr. Scott H. Sicherer, the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Professor of Pediatrics, Allergy and Immunology, and chief of the division of allergy and immunology in the department of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“However, adding peanut to the diet at this age requires caution because these infants may already be allergic to peanut, and so allergy testing and care in adding peanut to the diet with medical supervision is needed in this high-risk group,” noted Dr. Sicherer, a member of the expert panel that worked on the guidelines.

The draft guidelines include 43 clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies in children, according to the NIAID website. In particular, the draft guidelines recommend introducing peanut-containing foods to infants aged 4-6 months who are at increased risk for peanut allergy because of severe eczema and/or egg allergies, after an evaluation with skin prick testing or peanut-specific IgE testing.

“Peanut allergy is relatively common and often persistent, and so a strategy that could prevent the allergy is very important,” Dr. Sicherer said in an interview. “However, peanut can be a choking hazard as peanuts or peanut butter, and so families should talk to their pediatrician about how and when to incorporate peanut into the diet, and whether allergy testing and referral to an allergist is needed.”

Support for the guidelines comes from several large studies with promising results, notably the LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) trial. A recent extension of that study, known as LEAP-On (Persistence of Oral Tolerance to Peanut), showed that regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to 5 years provided ongoing protection against allergies, even 6 years after peanut consumption was discontinued for a 1-year period in 550 children (N Eng J Med. 2016 Apr 14;374:1435-43).

In the original LEAP study, 640 infants aged 4-11 months with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both were randomized to dietary peanut consumption or avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372[9]:803-13). The prevalence of peanut allergy at 5 years of age was approximately 2% in the peanut-consumption group, compared with 14% in the peanut-avoidance group.

Another significant randomized trial, the EAT study (Enquiring About Tolerance) tested not only peanut, but also the early introduction of cooked egg, cow’s milk, sesame, wheat, and fish to 1,303 infants aged 3 months and older in the general population. The study’s strict protocol made adherence difficult, but researchers found a significant 67% reduction in the prevalence of food allergies at age 3 years among the children who followed the protocol, compared with controls, with relative risk reductions of 100% and 75%, respectively, for peanut and egg allergies (N Engl J Med. 2016 May 5;374:1733-43).

The next steps for research should make early introduction of peanut-containing foods even more effective at allergy prevention, Dr. Sicherer noted.

“We need to learn more about how much peanut should be incorporated into the diet, how long the protein has to be kept in the diet to have the best preventative effect, and whether this strategy applies to other foods,” he said.

Updated guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for the early introduction of peanut-containing foods to children at increased risk for peanut allergies are on the horizon, pending final approval.

“Two studies recently showed that infants at high risk of developing peanut allergy [infants with egg allergy and or severe eczema] were much less likely to have peanut allergy at age 5 years if they were able to incorporate peanut regularly into the diet between 4 and 11 months of age,” said Dr. Scott H. Sicherer, the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Professor of Pediatrics, Allergy and Immunology, and chief of the division of allergy and immunology in the department of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“However, adding peanut to the diet at this age requires caution because these infants may already be allergic to peanut, and so allergy testing and care in adding peanut to the diet with medical supervision is needed in this high-risk group,” noted Dr. Sicherer, a member of the expert panel that worked on the guidelines.

The draft guidelines include 43 clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies in children, according to the NIAID website. In particular, the draft guidelines recommend introducing peanut-containing foods to infants aged 4-6 months who are at increased risk for peanut allergy because of severe eczema and/or egg allergies, after an evaluation with skin prick testing or peanut-specific IgE testing.

“Peanut allergy is relatively common and often persistent, and so a strategy that could prevent the allergy is very important,” Dr. Sicherer said in an interview. “However, peanut can be a choking hazard as peanuts or peanut butter, and so families should talk to their pediatrician about how and when to incorporate peanut into the diet, and whether allergy testing and referral to an allergist is needed.”

Support for the guidelines comes from several large studies with promising results, notably the LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) trial. A recent extension of that study, known as LEAP-On (Persistence of Oral Tolerance to Peanut), showed that regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to 5 years provided ongoing protection against allergies, even 6 years after peanut consumption was discontinued for a 1-year period in 550 children (N Eng J Med. 2016 Apr 14;374:1435-43).

In the original LEAP study, 640 infants aged 4-11 months with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both were randomized to dietary peanut consumption or avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372[9]:803-13). The prevalence of peanut allergy at 5 years of age was approximately 2% in the peanut-consumption group, compared with 14% in the peanut-avoidance group.

Another significant randomized trial, the EAT study (Enquiring About Tolerance) tested not only peanut, but also the early introduction of cooked egg, cow’s milk, sesame, wheat, and fish to 1,303 infants aged 3 months and older in the general population. The study’s strict protocol made adherence difficult, but researchers found a significant 67% reduction in the prevalence of food allergies at age 3 years among the children who followed the protocol, compared with controls, with relative risk reductions of 100% and 75%, respectively, for peanut and egg allergies (N Engl J Med. 2016 May 5;374:1733-43).

The next steps for research should make early introduction of peanut-containing foods even more effective at allergy prevention, Dr. Sicherer noted.

“We need to learn more about how much peanut should be incorporated into the diet, how long the protein has to be kept in the diet to have the best preventative effect, and whether this strategy applies to other foods,” he said.

The promise of peanut allergy prevention lies in draft guidelines

Updated guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for the early introduction of peanut-containing foods to children at increased risk for peanut allergies are on the horizon, pending final approval.

“Two studies recently showed that infants at high risk of developing peanut allergy [infants with egg allergy and or severe eczema] were much less likely to have peanut allergy at age 5 years if they were able to incorporate peanut regularly into the diet between 4 and 11 months of age,” said Dr. Scott H. Sicherer, the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Professor of Pediatrics, Allergy and Immunology, and chief of the division of allergy and immunology in the department of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“However, adding peanut to the diet at this age requires caution because these infants may already be allergic to peanut, and so allergy testing and care in adding peanut to the diet with medical supervision is needed in this high-risk group,” noted Dr. Sicherer, a member of the expert panel that worked on the guidelines.

The draft guidelines include 43 clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies in children, according to the NIAID website. In particular, the draft guidelines recommend introducing peanut-containing foods to infants aged 4-6 months who are at increased risk for peanut allergy because of severe eczema and/or egg allergies, after an evaluation with skin prick testing or peanut-specific IgE testing.

“Peanut allergy is relatively common and often persistent, and so a strategy that could prevent the allergy is very important,” Dr. Sicherer said in an interview. “However, peanut can be a choking hazard as peanuts or peanut butter, and so families should talk to their pediatrician about how and when to incorporate peanut into the diet, and whether allergy testing and referral to an allergist is needed.”

Support for the guidelines comes from several large studies with promising results, notably the LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) trial. A recent extension of that study, known as LEAP-On (Persistence of Oral Tolerance to Peanut), showed that regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to 5 years provided ongoing protection against allergies, even 6 years after peanut consumption was discontinued for a 1-year period in 550 children (N Eng J Med. 2016 Apr 14;374:1435-43).

In the original LEAP study, 640 infants aged 4-11 months with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both were randomized to dietary peanut consumption or avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372[9]:803-13). The prevalence of peanut allergy at 5 years of age was approximately 2% in the peanut-consumption group, compared with 14% in the peanut-avoidance group.

Another significant randomized trial, the EAT study (Enquiring About Tolerance) tested not only peanut, but also the early introduction of cooked egg, cow’s milk, sesame, wheat, and fish to 1,303 infants aged 3 months and older in the general population. The study’s strict protocol made adherence difficult, but researchers found a significant 67% reduction in the prevalence of food allergies at age 3 years among the children who followed the protocol, compared with controls, with relative risk reductions of 100% and 75%, respectively, for peanut and egg allergies (N Engl J Med. 2016 May 5;374:1733-43).

The next steps for research should make early introduction of peanut-containing foods even more effective at allergy prevention, Dr. Sicherer noted.

“We need to learn more about how much peanut should be incorporated into the diet, how long the protein has to be kept in the diet to have the best preventative effect, and whether this strategy applies to other foods,” he said.

Updated guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for the early introduction of peanut-containing foods to children at increased risk for peanut allergies are on the horizon, pending final approval.

“Two studies recently showed that infants at high risk of developing peanut allergy [infants with egg allergy and or severe eczema] were much less likely to have peanut allergy at age 5 years if they were able to incorporate peanut regularly into the diet between 4 and 11 months of age,” said Dr. Scott H. Sicherer, the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Professor of Pediatrics, Allergy and Immunology, and chief of the division of allergy and immunology in the department of pediatrics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“However, adding peanut to the diet at this age requires caution because these infants may already be allergic to peanut, and so allergy testing and care in adding peanut to the diet with medical supervision is needed in this high-risk group,” noted Dr. Sicherer, a member of the expert panel that worked on the guidelines.

The draft guidelines include 43 clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of food allergies in children, according to the NIAID website. In particular, the draft guidelines recommend introducing peanut-containing foods to infants aged 4-6 months who are at increased risk for peanut allergy because of severe eczema and/or egg allergies, after an evaluation with skin prick testing or peanut-specific IgE testing.

“Peanut allergy is relatively common and often persistent, and so a strategy that could prevent the allergy is very important,” Dr. Sicherer said in an interview. “However, peanut can be a choking hazard as peanuts or peanut butter, and so families should talk to their pediatrician about how and when to incorporate peanut into the diet, and whether allergy testing and referral to an allergist is needed.”

Support for the guidelines comes from several large studies with promising results, notably the LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) trial. A recent extension of that study, known as LEAP-On (Persistence of Oral Tolerance to Peanut), showed that regular consumption of peanut-containing foods from infancy to 5 years provided ongoing protection against allergies, even 6 years after peanut consumption was discontinued for a 1-year period in 550 children (N Eng J Med. 2016 Apr 14;374:1435-43).

In the original LEAP study, 640 infants aged 4-11 months with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both were randomized to dietary peanut consumption or avoidance (N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372[9]:803-13). The prevalence of peanut allergy at 5 years of age was approximately 2% in the peanut-consumption group, compared with 14% in the peanut-avoidance group.

Another significant randomized trial, the EAT study (Enquiring About Tolerance) tested not only peanut, but also the early introduction of cooked egg, cow’s milk, sesame, wheat, and fish to 1,303 infants aged 3 months and older in the general population. The study’s strict protocol made adherence difficult, but researchers found a significant 67% reduction in the prevalence of food allergies at age 3 years among the children who followed the protocol, compared with controls, with relative risk reductions of 100% and 75%, respectively, for peanut and egg allergies (N Engl J Med. 2016 May 5;374:1733-43).