User login

CHMP recommends drug for WM

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is recommending that ibrutinib (Imbruvica) be approved to treat Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

The CHMP is recommending the drug for use in WM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy as well as previously untreated WM patients who are not suitable candidates for chemo-immunotherapy.

The European Commission will review this recommendation and should make a decision later this year.

Ibrutinib is already approved to treat WM in the US. The drug is also approved in the European Union, the US, and other countries to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma.

Janssen-Cilag International NV (Janssen) holds the marketing authorization for ibrutinib in Europe, and its affiliates market the drug in Europe and the rest of the world. In the US, ibrutinib is under joint development by Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Phase 2 study

The CHMP’s recommendation for ibrutinib was based on a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers tested the drug in 63 patients with previously treated WM. Initial data showed an overall response rate of 87.3% in patients who received the drug for a median of 11.7 months.

Updated results from the study were published in NEJM in April. After a median treatment duration of 19.1 months, the overall response rate was 91%.

At 24 months, the estimated rate of progression-free survival was 69%, and the estimated rate of overall survival was 95%.

The most common grade 2-4 adverse events were neutropenia (22%) and thrombocytopenia (14%). Ibrutinib-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reversible but required a dose reduction in 3 patients and treatment discontinuation in 4 patients.

Grade 2 or higher bleeding events occurred in 4 patients, and there were 15 infections considered possibly related to ibrutinib.

Treatment-related atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurred in 3 patients, all of whom had a prior history of paroxysmal AFib. AFib resolved when treatment was withheld, and all 3 patients were able to continue on therapy per protocol without an additional event. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is recommending that ibrutinib (Imbruvica) be approved to treat Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

The CHMP is recommending the drug for use in WM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy as well as previously untreated WM patients who are not suitable candidates for chemo-immunotherapy.

The European Commission will review this recommendation and should make a decision later this year.

Ibrutinib is already approved to treat WM in the US. The drug is also approved in the European Union, the US, and other countries to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma.

Janssen-Cilag International NV (Janssen) holds the marketing authorization for ibrutinib in Europe, and its affiliates market the drug in Europe and the rest of the world. In the US, ibrutinib is under joint development by Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Phase 2 study

The CHMP’s recommendation for ibrutinib was based on a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers tested the drug in 63 patients with previously treated WM. Initial data showed an overall response rate of 87.3% in patients who received the drug for a median of 11.7 months.

Updated results from the study were published in NEJM in April. After a median treatment duration of 19.1 months, the overall response rate was 91%.

At 24 months, the estimated rate of progression-free survival was 69%, and the estimated rate of overall survival was 95%.

The most common grade 2-4 adverse events were neutropenia (22%) and thrombocytopenia (14%). Ibrutinib-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reversible but required a dose reduction in 3 patients and treatment discontinuation in 4 patients.

Grade 2 or higher bleeding events occurred in 4 patients, and there were 15 infections considered possibly related to ibrutinib.

Treatment-related atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurred in 3 patients, all of whom had a prior history of paroxysmal AFib. AFib resolved when treatment was withheld, and all 3 patients were able to continue on therapy per protocol without an additional event. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is recommending that ibrutinib (Imbruvica) be approved to treat Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

The CHMP is recommending the drug for use in WM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy as well as previously untreated WM patients who are not suitable candidates for chemo-immunotherapy.

The European Commission will review this recommendation and should make a decision later this year.

Ibrutinib is already approved to treat WM in the US. The drug is also approved in the European Union, the US, and other countries to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma.

Janssen-Cilag International NV (Janssen) holds the marketing authorization for ibrutinib in Europe, and its affiliates market the drug in Europe and the rest of the world. In the US, ibrutinib is under joint development by Pharmacyclics and Janssen Biotech, Inc.

Phase 2 study

The CHMP’s recommendation for ibrutinib was based on a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers tested the drug in 63 patients with previously treated WM. Initial data showed an overall response rate of 87.3% in patients who received the drug for a median of 11.7 months.

Updated results from the study were published in NEJM in April. After a median treatment duration of 19.1 months, the overall response rate was 91%.

At 24 months, the estimated rate of progression-free survival was 69%, and the estimated rate of overall survival was 95%.

The most common grade 2-4 adverse events were neutropenia (22%) and thrombocytopenia (14%). Ibrutinib-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reversible but required a dose reduction in 3 patients and treatment discontinuation in 4 patients.

Grade 2 or higher bleeding events occurred in 4 patients, and there were 15 infections considered possibly related to ibrutinib.

Treatment-related atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurred in 3 patients, all of whom had a prior history of paroxysmal AFib. AFib resolved when treatment was withheld, and all 3 patients were able to continue on therapy per protocol without an additional event. ![]()

Team reports new method to identify immune cells

Photo by Graham Colm

A new method for identifying immune cells could pave the way for rapid detection of hematologic malignancies from a small blood sample, according to researchers.

The team found they could use wavelength modulated Raman spectroscopy (WMRS) to identify subsets of T cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells.

Traditional methods of identifying these cells usually involve labeling them with fluorescent or magnetically labeled antibodies.

Using WMRS, the researchers were able to identify immune cells with no labeling at all, thus permitting rapid identification and further analysis to take place with no potential alteration to the cells.

Simon Powis, PhD, of the University of St Andrews in Fife, Scotland, and his colleagues described this work in PLOS ONE.

Raman scattering refers to light scattering from molecules in a sample where the light energy can be shifted up or down and recorded as a “molecular fingerprint” that can be used for identification. Normally, this process is very weak and further hampered by other background light (eg, fluorescence).

WMRS subtly changes the incident laser light that, in turn, results in a modulation of the Raman signal, allowing it to be extracted from any (stationary) interfering signal.

Using WMRS, Dr Powis and his colleagues found they could identify CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD56+ natural killer cells, CD303+ lymphoid/plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cells.

“Under a normal light microscope, these immune cells essentially all look identical,” Dr Powis said. “With this new method, we can identify key cell types without any labeling.”

“Our next goal is to make a full catalogue of all the normal cell types of the immune system that can be detected in the bloodstream. Once we have this completed, we can then collaborate with our clinical colleagues to start identifying when these immune cells are altered, in conditions such as leukemia and lymphoma, potentially providing a rapid detection system from just a small blood sample.” ![]()

Photo by Graham Colm

A new method for identifying immune cells could pave the way for rapid detection of hematologic malignancies from a small blood sample, according to researchers.

The team found they could use wavelength modulated Raman spectroscopy (WMRS) to identify subsets of T cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells.

Traditional methods of identifying these cells usually involve labeling them with fluorescent or magnetically labeled antibodies.

Using WMRS, the researchers were able to identify immune cells with no labeling at all, thus permitting rapid identification and further analysis to take place with no potential alteration to the cells.

Simon Powis, PhD, of the University of St Andrews in Fife, Scotland, and his colleagues described this work in PLOS ONE.

Raman scattering refers to light scattering from molecules in a sample where the light energy can be shifted up or down and recorded as a “molecular fingerprint” that can be used for identification. Normally, this process is very weak and further hampered by other background light (eg, fluorescence).

WMRS subtly changes the incident laser light that, in turn, results in a modulation of the Raman signal, allowing it to be extracted from any (stationary) interfering signal.

Using WMRS, Dr Powis and his colleagues found they could identify CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD56+ natural killer cells, CD303+ lymphoid/plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cells.

“Under a normal light microscope, these immune cells essentially all look identical,” Dr Powis said. “With this new method, we can identify key cell types without any labeling.”

“Our next goal is to make a full catalogue of all the normal cell types of the immune system that can be detected in the bloodstream. Once we have this completed, we can then collaborate with our clinical colleagues to start identifying when these immune cells are altered, in conditions such as leukemia and lymphoma, potentially providing a rapid detection system from just a small blood sample.” ![]()

Photo by Graham Colm

A new method for identifying immune cells could pave the way for rapid detection of hematologic malignancies from a small blood sample, according to researchers.

The team found they could use wavelength modulated Raman spectroscopy (WMRS) to identify subsets of T cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells.

Traditional methods of identifying these cells usually involve labeling them with fluorescent or magnetically labeled antibodies.

Using WMRS, the researchers were able to identify immune cells with no labeling at all, thus permitting rapid identification and further analysis to take place with no potential alteration to the cells.

Simon Powis, PhD, of the University of St Andrews in Fife, Scotland, and his colleagues described this work in PLOS ONE.

Raman scattering refers to light scattering from molecules in a sample where the light energy can be shifted up or down and recorded as a “molecular fingerprint” that can be used for identification. Normally, this process is very weak and further hampered by other background light (eg, fluorescence).

WMRS subtly changes the incident laser light that, in turn, results in a modulation of the Raman signal, allowing it to be extracted from any (stationary) interfering signal.

Using WMRS, Dr Powis and his colleagues found they could identify CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD56+ natural killer cells, CD303+ lymphoid/plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cells.

“Under a normal light microscope, these immune cells essentially all look identical,” Dr Powis said. “With this new method, we can identify key cell types without any labeling.”

“Our next goal is to make a full catalogue of all the normal cell types of the immune system that can be detected in the bloodstream. Once we have this completed, we can then collaborate with our clinical colleagues to start identifying when these immune cells are altered, in conditions such as leukemia and lymphoma, potentially providing a rapid detection system from just a small blood sample.” ![]()

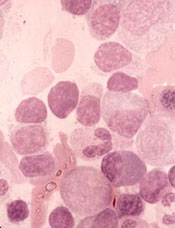

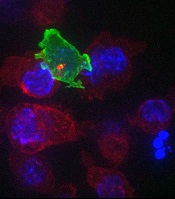

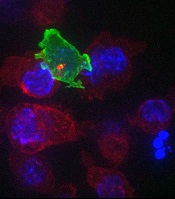

CTLs captured on video destroying cancer cells

cancer cells (blue)

Image courtesy of Gillian

Griffiths and Jonny Settle

New research has illuminated the behavior of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) as they hunt down and eliminate cancer cells.

Investigators used novel imaging techniques to capture the process on film and described their findings in an article published in Immunity.

The team captured the footage through high-resolution, 3D, time-lapse, multi-color imaging, making use of both spinning disk confocal microscopy and lattice light sheet microscopy.

These techniques involve capturing “slices” of an object and “stitching” them together to provide the final 3D images across the whole cell.

These approaches allowed the investigators to determine the order of events leading to the lethal “hit” CTLs deliver to cancer cells.

“Inside all of us lurks an army of ‘serial killers’ whose primary function is to kill again and again,” said study author Gillian Griffiths, PhD, of the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research in the UK.

“These [CTLs] patrol our bodies, identifying and destroying virally infected and cancer cells, and they do so with remarkable precision and efficiency.”

The CTLs, seen in the video as orange or green amorphous “blobs,” move around rapidly, investigating their environment as they travel.

When a CTL finds a cancer cell (blue), membrane protrusions rapidly explore the surface of the cell, checking for tell-tale signs that this is an uninvited guest.

The CTL binds to the cancer cell and injects cytotoxins (red) down microtubules to the interface between the T cell and the cancer cell, before puncturing the surface of the cancer cell and delivering its deadly cargo.

“In our bodies, where cells are packed together, it’s essential that the T cell focuses the lethal hit on its target,” Dr Griffiths explained. “Otherwise, it will cause collateral damage to neighboring, healthy cells.”

“Once the cytotoxins are injected into the cancer cell, its fate is sealed, and we can watch as it withers and dies. The T cell then moves on, hungry to find another victim.”

The investigators’ video is available on YouTube. ![]()

cancer cells (blue)

Image courtesy of Gillian

Griffiths and Jonny Settle

New research has illuminated the behavior of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) as they hunt down and eliminate cancer cells.

Investigators used novel imaging techniques to capture the process on film and described their findings in an article published in Immunity.

The team captured the footage through high-resolution, 3D, time-lapse, multi-color imaging, making use of both spinning disk confocal microscopy and lattice light sheet microscopy.

These techniques involve capturing “slices” of an object and “stitching” them together to provide the final 3D images across the whole cell.

These approaches allowed the investigators to determine the order of events leading to the lethal “hit” CTLs deliver to cancer cells.

“Inside all of us lurks an army of ‘serial killers’ whose primary function is to kill again and again,” said study author Gillian Griffiths, PhD, of the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research in the UK.

“These [CTLs] patrol our bodies, identifying and destroying virally infected and cancer cells, and they do so with remarkable precision and efficiency.”

The CTLs, seen in the video as orange or green amorphous “blobs,” move around rapidly, investigating their environment as they travel.

When a CTL finds a cancer cell (blue), membrane protrusions rapidly explore the surface of the cell, checking for tell-tale signs that this is an uninvited guest.

The CTL binds to the cancer cell and injects cytotoxins (red) down microtubules to the interface between the T cell and the cancer cell, before puncturing the surface of the cancer cell and delivering its deadly cargo.

“In our bodies, where cells are packed together, it’s essential that the T cell focuses the lethal hit on its target,” Dr Griffiths explained. “Otherwise, it will cause collateral damage to neighboring, healthy cells.”

“Once the cytotoxins are injected into the cancer cell, its fate is sealed, and we can watch as it withers and dies. The T cell then moves on, hungry to find another victim.”

The investigators’ video is available on YouTube. ![]()

cancer cells (blue)

Image courtesy of Gillian

Griffiths and Jonny Settle

New research has illuminated the behavior of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) as they hunt down and eliminate cancer cells.

Investigators used novel imaging techniques to capture the process on film and described their findings in an article published in Immunity.

The team captured the footage through high-resolution, 3D, time-lapse, multi-color imaging, making use of both spinning disk confocal microscopy and lattice light sheet microscopy.

These techniques involve capturing “slices” of an object and “stitching” them together to provide the final 3D images across the whole cell.

These approaches allowed the investigators to determine the order of events leading to the lethal “hit” CTLs deliver to cancer cells.

“Inside all of us lurks an army of ‘serial killers’ whose primary function is to kill again and again,” said study author Gillian Griffiths, PhD, of the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research in the UK.

“These [CTLs] patrol our bodies, identifying and destroying virally infected and cancer cells, and they do so with remarkable precision and efficiency.”

The CTLs, seen in the video as orange or green amorphous “blobs,” move around rapidly, investigating their environment as they travel.

When a CTL finds a cancer cell (blue), membrane protrusions rapidly explore the surface of the cell, checking for tell-tale signs that this is an uninvited guest.

The CTL binds to the cancer cell and injects cytotoxins (red) down microtubules to the interface between the T cell and the cancer cell, before puncturing the surface of the cancer cell and delivering its deadly cargo.

“In our bodies, where cells are packed together, it’s essential that the T cell focuses the lethal hit on its target,” Dr Griffiths explained. “Otherwise, it will cause collateral damage to neighboring, healthy cells.”

“Once the cytotoxins are injected into the cancer cell, its fate is sealed, and we can watch as it withers and dies. The T cell then moves on, hungry to find another victim.”

The investigators’ video is available on YouTube. ![]()

Combo targets AML, BL in the same way

Image by Ed Uthman

Combining a cholesterol-lowering drug and a contraceptive steroid could be a safe, effective treatment for leukemias, lymphomas, and other malignancies, according to researchers.

Their work helps explain how this combination treatment, bezafibrate and medroxyprogesterone acetate (BaP), kills cancer cells.

The team discovered that BaP’s mechanism of action is the same in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cells.

The findings have been published in Cancer Research.

BaP has been shown to prolong survival in early stage trials of elderly AML patients, when compared to standard palliative care. BaP has also been used alongside chemotherapy to successfully treat children with BL.

However, it was unclear whether BaP’s activity against these 2 very different malignancies was mediated by a common mechanism or by different effects in each cancer.

To gain some insight, Andrew Southam, PhD, of the University of Birmingham in the UK, and his colleagues investigated the drugs’ effects on the metabolism and chemical make-up of AML and BL cells.

They found that, in both cell types, BaP blocks stearoyl CoA desaturase, an enzyme crucial to the production of fatty acids, which cancer cells need to grow and multiply. The team also showed that BaP’s ability to deactivate stearoyl CoA desaturase was what prompted the cancer cells to die.

“Developing drugs to target the fatty-acid building blocks of cancer cells has been a promising area of research in recent years,” Dr Southam said. “It is very exciting we have identified these non-toxic drugs already sitting on pharmacy shelves.”

He and his colleagues believe these findings also open up the possibility that BaP could be used to treat other cancers that rely on high levels of stearoyl CoA desaturase to grow, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia and some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as prostate, colon, and esophageal cancers.

“This drug combination shows real promise,” said Chris Bunce, PhD, also of the University of Birmingham.

“Affordable, effective, non-toxic treatments that extend survival, while offering a good quality of life, are in demand for almost all types of cancer.” ![]()

Image by Ed Uthman

Combining a cholesterol-lowering drug and a contraceptive steroid could be a safe, effective treatment for leukemias, lymphomas, and other malignancies, according to researchers.

Their work helps explain how this combination treatment, bezafibrate and medroxyprogesterone acetate (BaP), kills cancer cells.

The team discovered that BaP’s mechanism of action is the same in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cells.

The findings have been published in Cancer Research.

BaP has been shown to prolong survival in early stage trials of elderly AML patients, when compared to standard palliative care. BaP has also been used alongside chemotherapy to successfully treat children with BL.

However, it was unclear whether BaP’s activity against these 2 very different malignancies was mediated by a common mechanism or by different effects in each cancer.

To gain some insight, Andrew Southam, PhD, of the University of Birmingham in the UK, and his colleagues investigated the drugs’ effects on the metabolism and chemical make-up of AML and BL cells.

They found that, in both cell types, BaP blocks stearoyl CoA desaturase, an enzyme crucial to the production of fatty acids, which cancer cells need to grow and multiply. The team also showed that BaP’s ability to deactivate stearoyl CoA desaturase was what prompted the cancer cells to die.

“Developing drugs to target the fatty-acid building blocks of cancer cells has been a promising area of research in recent years,” Dr Southam said. “It is very exciting we have identified these non-toxic drugs already sitting on pharmacy shelves.”

He and his colleagues believe these findings also open up the possibility that BaP could be used to treat other cancers that rely on high levels of stearoyl CoA desaturase to grow, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia and some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as prostate, colon, and esophageal cancers.

“This drug combination shows real promise,” said Chris Bunce, PhD, also of the University of Birmingham.

“Affordable, effective, non-toxic treatments that extend survival, while offering a good quality of life, are in demand for almost all types of cancer.” ![]()

Image by Ed Uthman

Combining a cholesterol-lowering drug and a contraceptive steroid could be a safe, effective treatment for leukemias, lymphomas, and other malignancies, according to researchers.

Their work helps explain how this combination treatment, bezafibrate and medroxyprogesterone acetate (BaP), kills cancer cells.

The team discovered that BaP’s mechanism of action is the same in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cells.

The findings have been published in Cancer Research.

BaP has been shown to prolong survival in early stage trials of elderly AML patients, when compared to standard palliative care. BaP has also been used alongside chemotherapy to successfully treat children with BL.

However, it was unclear whether BaP’s activity against these 2 very different malignancies was mediated by a common mechanism or by different effects in each cancer.

To gain some insight, Andrew Southam, PhD, of the University of Birmingham in the UK, and his colleagues investigated the drugs’ effects on the metabolism and chemical make-up of AML and BL cells.

They found that, in both cell types, BaP blocks stearoyl CoA desaturase, an enzyme crucial to the production of fatty acids, which cancer cells need to grow and multiply. The team also showed that BaP’s ability to deactivate stearoyl CoA desaturase was what prompted the cancer cells to die.

“Developing drugs to target the fatty-acid building blocks of cancer cells has been a promising area of research in recent years,” Dr Southam said. “It is very exciting we have identified these non-toxic drugs already sitting on pharmacy shelves.”

He and his colleagues believe these findings also open up the possibility that BaP could be used to treat other cancers that rely on high levels of stearoyl CoA desaturase to grow, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia and some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as prostate, colon, and esophageal cancers.

“This drug combination shows real promise,” said Chris Bunce, PhD, also of the University of Birmingham.

“Affordable, effective, non-toxic treatments that extend survival, while offering a good quality of life, are in demand for almost all types of cancer.” ![]()

How mAbs produce lasting antitumor effects

Photo by Linda Bartlett

Results of preclinical research help explain how antitumor monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) fight lymphoma.

Researchers uncovered a 2-step process that revolves around 2 antibody-binding receptors found on different types of immune cells.

Experiments suggested that these Fc receptors are needed to eradicate lymphoma and ensure it doesn’t return.

The researchers reported these findings in an article published in Cell.

“These findings suggests ways current anticancer antibody treatments might be improved, as well as combined with other immune-system-stimulating therapies to help cancer patients,” said study author Jeffrey Ravetch, MD, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York.

Previous research has shown that antitumor mAbs bind to Fc receptors on activated immune cells, prompting those immune cells to kill tumors.

However, it was unclear which Fc receptors are involved or how the tumor killing led the immune system to generate memory T cells against these same antigens, in case the tumor producing them should return.

Dr Ravetch and David DiLillo, PhD, also of The Rockefeller University, investigated this process by injecting CD20-expressing lymphoma cells into mice with immune systems engineered to contain human Fc receptors, treating the mice with anti-CD20 mAbs, and then re-introducing lymphoma.

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice received syngeneic EL4 lymphoma cells expressing human CD20 (EL4-hCD20 cells). When these mice received treatment with an mIgG2a isotype anti-hCD20 mAb, they all survived.

Ninety days later, after the mAb had been cleared from their systems, the mice were re-challenged with EL4-hCD20 tumor cells, at a dose 10-fold greater than the initial challenge, but they did not receive any additional mAb.

All of these mice survived, but tumor/mAb-primed mice that were re-challenged with EL4-wild-type cells, which don’t express hCD20, had poor survival. Results were similar with a different anti-hCD20 mAb, clone 2B8.

The researchers also re-challenged tumor/mAb-primed mice with B6BL lymphoma cells that expressed either hCD20 or an irrelevant antigen, mCD20. All of the mice re-challenged with B6BL-mCD20 cells had died by day 31, but 80% of the mice re-challenged with B6BL-hCD20 cells survived at least 90 days.

Drs Ravetch and DiLillo said these results suggest an anti-hCD20 immune response is generated after the initial FcγR-mediated clearance of tumor cells by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

The researchers then took a closer look at the role of Fc receptors, keeping in mind that different types of immune cells can express different receptors.

Based on the cells the researchers thought were involved, they looked to the Fc receptors expressed by cytotoxic immune cells that carried out the initial attack on tumors, as well as the Fc receptors found on dendritic cells, which are crucial to the formation of memory T cells.

To test the involvement of these receptors, the pair altered the mAbs delivered to the lymphoma-infected mice so as to change their affinity for the receptors. Then, they looked for changes in the survival rate of the mice after the first and second challenges with lymphoma cells.

When they dissected this process, the researchers uncovered 2 steps. The Fc receptor FcγRIIIA, which is found on macrophages, responded to mAbs and prompted the macrophages to engulf and destroy the antibody-laden tumor cells.

These same antibodies, still attached to tumor antigens, activated a second receptor, FcγRIIA, on dendritic cells, which used the antigen to prime T cells. The result was the generation of a T-cell memory response that protected the mice against future lymphoma cells expressing CD20.

“By engineering the antibodies so as to increase their affinity for both FcγRIIIA and FcγRIIA, we were able to optimize both steps in this process,” Dr DiLillo said.

“Current antibody therapies are only engineered to improve the immediate killing of tumor cells but not the formation of immunological memory. We are proposing that an ideal antibody therapy would be engineered to take full advantage of both steps.” ![]()

Photo by Linda Bartlett

Results of preclinical research help explain how antitumor monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) fight lymphoma.

Researchers uncovered a 2-step process that revolves around 2 antibody-binding receptors found on different types of immune cells.

Experiments suggested that these Fc receptors are needed to eradicate lymphoma and ensure it doesn’t return.

The researchers reported these findings in an article published in Cell.

“These findings suggests ways current anticancer antibody treatments might be improved, as well as combined with other immune-system-stimulating therapies to help cancer patients,” said study author Jeffrey Ravetch, MD, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York.

Previous research has shown that antitumor mAbs bind to Fc receptors on activated immune cells, prompting those immune cells to kill tumors.

However, it was unclear which Fc receptors are involved or how the tumor killing led the immune system to generate memory T cells against these same antigens, in case the tumor producing them should return.

Dr Ravetch and David DiLillo, PhD, also of The Rockefeller University, investigated this process by injecting CD20-expressing lymphoma cells into mice with immune systems engineered to contain human Fc receptors, treating the mice with anti-CD20 mAbs, and then re-introducing lymphoma.

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice received syngeneic EL4 lymphoma cells expressing human CD20 (EL4-hCD20 cells). When these mice received treatment with an mIgG2a isotype anti-hCD20 mAb, they all survived.

Ninety days later, after the mAb had been cleared from their systems, the mice were re-challenged with EL4-hCD20 tumor cells, at a dose 10-fold greater than the initial challenge, but they did not receive any additional mAb.

All of these mice survived, but tumor/mAb-primed mice that were re-challenged with EL4-wild-type cells, which don’t express hCD20, had poor survival. Results were similar with a different anti-hCD20 mAb, clone 2B8.

The researchers also re-challenged tumor/mAb-primed mice with B6BL lymphoma cells that expressed either hCD20 or an irrelevant antigen, mCD20. All of the mice re-challenged with B6BL-mCD20 cells had died by day 31, but 80% of the mice re-challenged with B6BL-hCD20 cells survived at least 90 days.

Drs Ravetch and DiLillo said these results suggest an anti-hCD20 immune response is generated after the initial FcγR-mediated clearance of tumor cells by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

The researchers then took a closer look at the role of Fc receptors, keeping in mind that different types of immune cells can express different receptors.

Based on the cells the researchers thought were involved, they looked to the Fc receptors expressed by cytotoxic immune cells that carried out the initial attack on tumors, as well as the Fc receptors found on dendritic cells, which are crucial to the formation of memory T cells.

To test the involvement of these receptors, the pair altered the mAbs delivered to the lymphoma-infected mice so as to change their affinity for the receptors. Then, they looked for changes in the survival rate of the mice after the first and second challenges with lymphoma cells.

When they dissected this process, the researchers uncovered 2 steps. The Fc receptor FcγRIIIA, which is found on macrophages, responded to mAbs and prompted the macrophages to engulf and destroy the antibody-laden tumor cells.

These same antibodies, still attached to tumor antigens, activated a second receptor, FcγRIIA, on dendritic cells, which used the antigen to prime T cells. The result was the generation of a T-cell memory response that protected the mice against future lymphoma cells expressing CD20.

“By engineering the antibodies so as to increase their affinity for both FcγRIIIA and FcγRIIA, we were able to optimize both steps in this process,” Dr DiLillo said.

“Current antibody therapies are only engineered to improve the immediate killing of tumor cells but not the formation of immunological memory. We are proposing that an ideal antibody therapy would be engineered to take full advantage of both steps.” ![]()

Photo by Linda Bartlett

Results of preclinical research help explain how antitumor monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) fight lymphoma.

Researchers uncovered a 2-step process that revolves around 2 antibody-binding receptors found on different types of immune cells.

Experiments suggested that these Fc receptors are needed to eradicate lymphoma and ensure it doesn’t return.

The researchers reported these findings in an article published in Cell.

“These findings suggests ways current anticancer antibody treatments might be improved, as well as combined with other immune-system-stimulating therapies to help cancer patients,” said study author Jeffrey Ravetch, MD, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York.

Previous research has shown that antitumor mAbs bind to Fc receptors on activated immune cells, prompting those immune cells to kill tumors.

However, it was unclear which Fc receptors are involved or how the tumor killing led the immune system to generate memory T cells against these same antigens, in case the tumor producing them should return.

Dr Ravetch and David DiLillo, PhD, also of The Rockefeller University, investigated this process by injecting CD20-expressing lymphoma cells into mice with immune systems engineered to contain human Fc receptors, treating the mice with anti-CD20 mAbs, and then re-introducing lymphoma.

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice received syngeneic EL4 lymphoma cells expressing human CD20 (EL4-hCD20 cells). When these mice received treatment with an mIgG2a isotype anti-hCD20 mAb, they all survived.

Ninety days later, after the mAb had been cleared from their systems, the mice were re-challenged with EL4-hCD20 tumor cells, at a dose 10-fold greater than the initial challenge, but they did not receive any additional mAb.

All of these mice survived, but tumor/mAb-primed mice that were re-challenged with EL4-wild-type cells, which don’t express hCD20, had poor survival. Results were similar with a different anti-hCD20 mAb, clone 2B8.

The researchers also re-challenged tumor/mAb-primed mice with B6BL lymphoma cells that expressed either hCD20 or an irrelevant antigen, mCD20. All of the mice re-challenged with B6BL-mCD20 cells had died by day 31, but 80% of the mice re-challenged with B6BL-hCD20 cells survived at least 90 days.

Drs Ravetch and DiLillo said these results suggest an anti-hCD20 immune response is generated after the initial FcγR-mediated clearance of tumor cells by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

The researchers then took a closer look at the role of Fc receptors, keeping in mind that different types of immune cells can express different receptors.

Based on the cells the researchers thought were involved, they looked to the Fc receptors expressed by cytotoxic immune cells that carried out the initial attack on tumors, as well as the Fc receptors found on dendritic cells, which are crucial to the formation of memory T cells.

To test the involvement of these receptors, the pair altered the mAbs delivered to the lymphoma-infected mice so as to change their affinity for the receptors. Then, they looked for changes in the survival rate of the mice after the first and second challenges with lymphoma cells.

When they dissected this process, the researchers uncovered 2 steps. The Fc receptor FcγRIIIA, which is found on macrophages, responded to mAbs and prompted the macrophages to engulf and destroy the antibody-laden tumor cells.

These same antibodies, still attached to tumor antigens, activated a second receptor, FcγRIIA, on dendritic cells, which used the antigen to prime T cells. The result was the generation of a T-cell memory response that protected the mice against future lymphoma cells expressing CD20.

“By engineering the antibodies so as to increase their affinity for both FcγRIIIA and FcγRIIA, we were able to optimize both steps in this process,” Dr DiLillo said.

“Current antibody therapies are only engineered to improve the immediate killing of tumor cells but not the formation of immunological memory. We are proposing that an ideal antibody therapy would be engineered to take full advantage of both steps.” ![]()

Company stops phase 3 PTCL trial

for use in a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited has announced its decision to discontinue its phase 3 trial of the aurora A kinase inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Results of a pre-specified interim analysis indicated that alisertib was unlikely to meet the study’s primary endpoint: providing superior progression-free survival over the standard of care for PTCL.

Takeda said patients enrolled in the trial may continue to receive alisertib if they are thought to be benefitting from it and no safety concerns are present.

The company is encouraging patients to consult their study investigators to address any questions and before making any changes to their medication.

Takeda is working with trial investigators and local regulatory authorities to ensure that PTCL patients who participated in the study receive appropriate care.

The company is still investigating alisertib for use in small-cell lung cancer.

“While we are disappointed that alisertib will not be further investigated for relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma, we are optimistic about alisertib’s clinical development program in small-cell lung cancer,” said Michael Vasconcelles, MD, global head of the Takeda Oncology Therapeutic Unit.

“The randomized, phase 2 study of alisertib in small-cell lung cancer will continue as planned and is currently underway. Takeda also continues to support investigator-initiated research with alisertib and will evaluate its potential use in other oncology indications going forward.” ![]()

for use in a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited has announced its decision to discontinue its phase 3 trial of the aurora A kinase inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Results of a pre-specified interim analysis indicated that alisertib was unlikely to meet the study’s primary endpoint: providing superior progression-free survival over the standard of care for PTCL.

Takeda said patients enrolled in the trial may continue to receive alisertib if they are thought to be benefitting from it and no safety concerns are present.

The company is encouraging patients to consult their study investigators to address any questions and before making any changes to their medication.

Takeda is working with trial investigators and local regulatory authorities to ensure that PTCL patients who participated in the study receive appropriate care.

The company is still investigating alisertib for use in small-cell lung cancer.

“While we are disappointed that alisertib will not be further investigated for relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma, we are optimistic about alisertib’s clinical development program in small-cell lung cancer,” said Michael Vasconcelles, MD, global head of the Takeda Oncology Therapeutic Unit.

“The randomized, phase 2 study of alisertib in small-cell lung cancer will continue as planned and is currently underway. Takeda also continues to support investigator-initiated research with alisertib and will evaluate its potential use in other oncology indications going forward.” ![]()

for use in a clinical trial

Photo by Esther Dyson

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited has announced its decision to discontinue its phase 3 trial of the aurora A kinase inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Results of a pre-specified interim analysis indicated that alisertib was unlikely to meet the study’s primary endpoint: providing superior progression-free survival over the standard of care for PTCL.

Takeda said patients enrolled in the trial may continue to receive alisertib if they are thought to be benefitting from it and no safety concerns are present.

The company is encouraging patients to consult their study investigators to address any questions and before making any changes to their medication.

Takeda is working with trial investigators and local regulatory authorities to ensure that PTCL patients who participated in the study receive appropriate care.

The company is still investigating alisertib for use in small-cell lung cancer.

“While we are disappointed that alisertib will not be further investigated for relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma, we are optimistic about alisertib’s clinical development program in small-cell lung cancer,” said Michael Vasconcelles, MD, global head of the Takeda Oncology Therapeutic Unit.

“The randomized, phase 2 study of alisertib in small-cell lung cancer will continue as planned and is currently underway. Takeda also continues to support investigator-initiated research with alisertib and will evaluate its potential use in other oncology indications going forward.” ![]()

Familial factors linked to child’s risk of blood cancer

A new study has linked a father’s age at his child’s birth to the risk that the child will develop a hematologic malignancy as an adult, but this risk only proved significant among children without siblings.

Only-children whose fathers were 35 or older at the child’s birth were significantly more likely to develop hematologic malignancies than only-children with fathers who were younger than 25 at the child’s birth.

There was no association between these cancers and a mother’s age, either among only-children or those with siblings.

A previous study of more than 100,000 women also showed an association between paternal—but not maternal—age at a child’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy.

To further investigate the association, Lauren Teras, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues analyzed data from women and men enrolled in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.

The team reported their findings in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Among the 138,003 participants, there were 2532 cases of hematologic malignancies diagnosed between 1992 and 2009.

Subjects’ mothers tended to be younger at their birth than fathers, with median ages of 27 and 31, respectively. Almost a third of the fathers were 35 or older when a subject was born, compared with 17% of the mothers.

In the categorical analysis, the researchers found a positive association between older paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancies in male, but not female, subjects. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.35 for male subjects with fathers aged 35 and older compared to those whose fathers were younger than 25.

On the other hand, when paternal age was modeled as a continuous variable, there was no association with the risk of hematologic malignancy for males or females. Likewise, there was no association between maternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy in male or female subjects.

However, among subjects without siblings, there was a significant, positive association with paternal age and the risk of hematologic malignancy (P=0.002).

When the researchers separated only-children by sex, they found a suggestive positive association between paternal age and hematologic malignancy for females (HR=1.40) and a significant association for males (HR=1.84). However, the linear spline was significant for males (P=0.01) and females (P=0.04).

There was no association between paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with at least 1 sibling (HR=1.06).

The researchers said the fact that the association between paternal age and malignancy was significant in subjects with no siblings suggests it may be related to the “hygiene hypothesis”—the idea that exposure to mild infections in childhood, which might be more numerous with more siblings, are important to immune system development and may reduce the risk of immune-related diseases.

It is possible that the combination of having an older father and no siblings may promote cell proliferation in those individuals with an underdeveloped immune system and, as such, favors the development of cancers related to the immune system, the team said.

They added that this study suggests a need for further research to better understand the association between paternal age at a child’s birth and hematologic malignancies.

“The lifetime risk of these cancers is fairly low—about 1 in 20 men and women will be diagnosed with lymphoma, leukemia, or myeloma at some point during their lifetime—so people born to older fathers should not be alarmed,” Dr Teras said.

“Still, the study does highlight the need for more research to confirm these findings and to clarify the biologic underpinning for this association, given the growing number of children born to older fathers in the United States and worldwide.” ![]()

A new study has linked a father’s age at his child’s birth to the risk that the child will develop a hematologic malignancy as an adult, but this risk only proved significant among children without siblings.

Only-children whose fathers were 35 or older at the child’s birth were significantly more likely to develop hematologic malignancies than only-children with fathers who were younger than 25 at the child’s birth.

There was no association between these cancers and a mother’s age, either among only-children or those with siblings.

A previous study of more than 100,000 women also showed an association between paternal—but not maternal—age at a child’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy.

To further investigate the association, Lauren Teras, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues analyzed data from women and men enrolled in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.

The team reported their findings in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Among the 138,003 participants, there were 2532 cases of hematologic malignancies diagnosed between 1992 and 2009.

Subjects’ mothers tended to be younger at their birth than fathers, with median ages of 27 and 31, respectively. Almost a third of the fathers were 35 or older when a subject was born, compared with 17% of the mothers.

In the categorical analysis, the researchers found a positive association between older paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancies in male, but not female, subjects. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.35 for male subjects with fathers aged 35 and older compared to those whose fathers were younger than 25.

On the other hand, when paternal age was modeled as a continuous variable, there was no association with the risk of hematologic malignancy for males or females. Likewise, there was no association between maternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy in male or female subjects.

However, among subjects without siblings, there was a significant, positive association with paternal age and the risk of hematologic malignancy (P=0.002).

When the researchers separated only-children by sex, they found a suggestive positive association between paternal age and hematologic malignancy for females (HR=1.40) and a significant association for males (HR=1.84). However, the linear spline was significant for males (P=0.01) and females (P=0.04).

There was no association between paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with at least 1 sibling (HR=1.06).

The researchers said the fact that the association between paternal age and malignancy was significant in subjects with no siblings suggests it may be related to the “hygiene hypothesis”—the idea that exposure to mild infections in childhood, which might be more numerous with more siblings, are important to immune system development and may reduce the risk of immune-related diseases.

It is possible that the combination of having an older father and no siblings may promote cell proliferation in those individuals with an underdeveloped immune system and, as such, favors the development of cancers related to the immune system, the team said.

They added that this study suggests a need for further research to better understand the association between paternal age at a child’s birth and hematologic malignancies.

“The lifetime risk of these cancers is fairly low—about 1 in 20 men and women will be diagnosed with lymphoma, leukemia, or myeloma at some point during their lifetime—so people born to older fathers should not be alarmed,” Dr Teras said.

“Still, the study does highlight the need for more research to confirm these findings and to clarify the biologic underpinning for this association, given the growing number of children born to older fathers in the United States and worldwide.” ![]()

A new study has linked a father’s age at his child’s birth to the risk that the child will develop a hematologic malignancy as an adult, but this risk only proved significant among children without siblings.

Only-children whose fathers were 35 or older at the child’s birth were significantly more likely to develop hematologic malignancies than only-children with fathers who were younger than 25 at the child’s birth.

There was no association between these cancers and a mother’s age, either among only-children or those with siblings.

A previous study of more than 100,000 women also showed an association between paternal—but not maternal—age at a child’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy.

To further investigate the association, Lauren Teras, PhD, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues analyzed data from women and men enrolled in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort.

The team reported their findings in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Among the 138,003 participants, there were 2532 cases of hematologic malignancies diagnosed between 1992 and 2009.

Subjects’ mothers tended to be younger at their birth than fathers, with median ages of 27 and 31, respectively. Almost a third of the fathers were 35 or older when a subject was born, compared with 17% of the mothers.

In the categorical analysis, the researchers found a positive association between older paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancies in male, but not female, subjects. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.35 for male subjects with fathers aged 35 and older compared to those whose fathers were younger than 25.

On the other hand, when paternal age was modeled as a continuous variable, there was no association with the risk of hematologic malignancy for males or females. Likewise, there was no association between maternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy in male or female subjects.

However, among subjects without siblings, there was a significant, positive association with paternal age and the risk of hematologic malignancy (P=0.002).

When the researchers separated only-children by sex, they found a suggestive positive association between paternal age and hematologic malignancy for females (HR=1.40) and a significant association for males (HR=1.84). However, the linear spline was significant for males (P=0.01) and females (P=0.04).

There was no association between paternal age at a subject’s birth and the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with at least 1 sibling (HR=1.06).

The researchers said the fact that the association between paternal age and malignancy was significant in subjects with no siblings suggests it may be related to the “hygiene hypothesis”—the idea that exposure to mild infections in childhood, which might be more numerous with more siblings, are important to immune system development and may reduce the risk of immune-related diseases.

It is possible that the combination of having an older father and no siblings may promote cell proliferation in those individuals with an underdeveloped immune system and, as such, favors the development of cancers related to the immune system, the team said.

They added that this study suggests a need for further research to better understand the association between paternal age at a child’s birth and hematologic malignancies.

“The lifetime risk of these cancers is fairly low—about 1 in 20 men and women will be diagnosed with lymphoma, leukemia, or myeloma at some point during their lifetime—so people born to older fathers should not be alarmed,” Dr Teras said.

“Still, the study does highlight the need for more research to confirm these findings and to clarify the biologic underpinning for this association, given the growing number of children born to older fathers in the United States and worldwide.”

Study helps explain how drug fights DLBCL

PHILADELPHIA—The tumor microenvironment may play a key role in treatment with CUDC-427, according to researchers.

Their experiments showed that certain diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell lines were sensitive to CUDC-427, and others were not.

However, co-culturing with stromal cells or TNF family ligands made resistant cell lines sensitive to CUDC-427.

And mice bearing cells that resisted CUDC-427 in vitro responded very well to treatment, experiencing complete tumor regression.

Ze Tian, PhD, and her colleagues from Curis, Inc. (the company developing CUDC-427) presented these findings at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 (abstract 5502).

CUDC-427 is an inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) antagonist that is in early stage clinical testing in patients with solid tumors and lymphomas.

For the current research, Dr Tian and her colleagues first evaluated the effects of CUDC-427 against a range of hematologic malignancies in vitro. They tested the drug in activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL, germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL, other non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and various leukemia cell lines.

DLBCL cells (both ABC and GCB) proved the most sensitive to treatment, and CUDC-427 induced apoptosis in these cells. However, certain DLBCL cell lines, such as Karpas 422, were not sensitive to treatment.

The researchers found they could remedy that in two ways. The presence of stromal cells in culture sensitized resistant DLBCL cells to treatment, as did TNF family ligands (TNFα or TRAIL). In previous research, TNF family ligands were shown to synergize with IAP antagonists.

The investigators then analyzed CUDC-427’s mechanism of action. In the sensitive WSU-DLCL2 cell line, the drug worked by activating caspases 3, 8, and 9 by inhibiting cIAP1 and XIAP, as well as activating the non-canonical NF-ĸB pathway and inducing TNFα.

In the resistant Karpas 422 cell line, there was no caspase activity following CUDC-427 treatment. However, when the researchers co-cultured the cell line with stromal cells, they saw caspase activity.

“Because of this finding, we think that the microenvironment may play a role in CUDC-427 treatment,” Dr Tian said.

So the investigators went on to test CUDC-427 in mouse models. The drug inhibited tumor growth by 94% in the WSU-DLCL2 xenograft model. But CUDC-427 induced complete tumor regression in the Karpas 422 xenograft model.

To further investigate the interaction between the tumor microenvironment and CUDC-427, the researchers tested the drug in the A20 B-cell lymphoma mouse syngeneic model.

They found that CUDC-427 induced tumor stasis in this fast-growing lymphoma. They believe this may be due, in part, to the high levels of TRAIL in this model.

Dr Tian and her colleagues said the interaction between CUDC-427 and TNF family ligands or stromal cells warrants further analysis. And this research supports additional investigation to improve outcomes in patients with DLBCL.

PHILADELPHIA—The tumor microenvironment may play a key role in treatment with CUDC-427, according to researchers.

Their experiments showed that certain diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell lines were sensitive to CUDC-427, and others were not.

However, co-culturing with stromal cells or TNF family ligands made resistant cell lines sensitive to CUDC-427.

And mice bearing cells that resisted CUDC-427 in vitro responded very well to treatment, experiencing complete tumor regression.

Ze Tian, PhD, and her colleagues from Curis, Inc. (the company developing CUDC-427) presented these findings at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 (abstract 5502).

CUDC-427 is an inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) antagonist that is in early stage clinical testing in patients with solid tumors and lymphomas.

For the current research, Dr Tian and her colleagues first evaluated the effects of CUDC-427 against a range of hematologic malignancies in vitro. They tested the drug in activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL, germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL, other non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and various leukemia cell lines.

DLBCL cells (both ABC and GCB) proved the most sensitive to treatment, and CUDC-427 induced apoptosis in these cells. However, certain DLBCL cell lines, such as Karpas 422, were not sensitive to treatment.

The researchers found they could remedy that in two ways. The presence of stromal cells in culture sensitized resistant DLBCL cells to treatment, as did TNF family ligands (TNFα or TRAIL). In previous research, TNF family ligands were shown to synergize with IAP antagonists.

The investigators then analyzed CUDC-427’s mechanism of action. In the sensitive WSU-DLCL2 cell line, the drug worked by activating caspases 3, 8, and 9 by inhibiting cIAP1 and XIAP, as well as activating the non-canonical NF-ĸB pathway and inducing TNFα.

In the resistant Karpas 422 cell line, there was no caspase activity following CUDC-427 treatment. However, when the researchers co-cultured the cell line with stromal cells, they saw caspase activity.

“Because of this finding, we think that the microenvironment may play a role in CUDC-427 treatment,” Dr Tian said.

So the investigators went on to test CUDC-427 in mouse models. The drug inhibited tumor growth by 94% in the WSU-DLCL2 xenograft model. But CUDC-427 induced complete tumor regression in the Karpas 422 xenograft model.

To further investigate the interaction between the tumor microenvironment and CUDC-427, the researchers tested the drug in the A20 B-cell lymphoma mouse syngeneic model.

They found that CUDC-427 induced tumor stasis in this fast-growing lymphoma. They believe this may be due, in part, to the high levels of TRAIL in this model.

Dr Tian and her colleagues said the interaction between CUDC-427 and TNF family ligands or stromal cells warrants further analysis. And this research supports additional investigation to improve outcomes in patients with DLBCL.

PHILADELPHIA—The tumor microenvironment may play a key role in treatment with CUDC-427, according to researchers.

Their experiments showed that certain diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell lines were sensitive to CUDC-427, and others were not.

However, co-culturing with stromal cells or TNF family ligands made resistant cell lines sensitive to CUDC-427.

And mice bearing cells that resisted CUDC-427 in vitro responded very well to treatment, experiencing complete tumor regression.

Ze Tian, PhD, and her colleagues from Curis, Inc. (the company developing CUDC-427) presented these findings at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 (abstract 5502).

CUDC-427 is an inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) antagonist that is in early stage clinical testing in patients with solid tumors and lymphomas.

For the current research, Dr Tian and her colleagues first evaluated the effects of CUDC-427 against a range of hematologic malignancies in vitro. They tested the drug in activated B-cell-like (ABC) DLBCL, germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL, other non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and various leukemia cell lines.

DLBCL cells (both ABC and GCB) proved the most sensitive to treatment, and CUDC-427 induced apoptosis in these cells. However, certain DLBCL cell lines, such as Karpas 422, were not sensitive to treatment.

The researchers found they could remedy that in two ways. The presence of stromal cells in culture sensitized resistant DLBCL cells to treatment, as did TNF family ligands (TNFα or TRAIL). In previous research, TNF family ligands were shown to synergize with IAP antagonists.

The investigators then analyzed CUDC-427’s mechanism of action. In the sensitive WSU-DLCL2 cell line, the drug worked by activating caspases 3, 8, and 9 by inhibiting cIAP1 and XIAP, as well as activating the non-canonical NF-ĸB pathway and inducing TNFα.

In the resistant Karpas 422 cell line, there was no caspase activity following CUDC-427 treatment. However, when the researchers co-cultured the cell line with stromal cells, they saw caspase activity.

“Because of this finding, we think that the microenvironment may play a role in CUDC-427 treatment,” Dr Tian said.

So the investigators went on to test CUDC-427 in mouse models. The drug inhibited tumor growth by 94% in the WSU-DLCL2 xenograft model. But CUDC-427 induced complete tumor regression in the Karpas 422 xenograft model.

To further investigate the interaction between the tumor microenvironment and CUDC-427, the researchers tested the drug in the A20 B-cell lymphoma mouse syngeneic model.

They found that CUDC-427 induced tumor stasis in this fast-growing lymphoma. They believe this may be due, in part, to the high levels of TRAIL in this model.

Dr Tian and her colleagues said the interaction between CUDC-427 and TNF family ligands or stromal cells warrants further analysis. And this research supports additional investigation to improve outcomes in patients with DLBCL.

Explaining obesity in cancer survivors

Researchers have identified several factors that may influence the risk of obesity in childhood cancer survivors.

Previous research showed that obesity rates are elevated in childhood cancer survivors who were exposed to cranial radiation.

But the new study has shown that other types of treatment, a patient’s age, and certain genetic variants are associated with obesity in this population.

Carmen Wilson, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

The researchers evaluated 1,996 childhood cancer survivors treated at St. Jude. The patients’ median age at diagnosis was 7.2 years (range, 0.1-24.8), and their median age at follow-up was 32.4 years (range, 18.9-63.8).

At the time of evaluation, 645 patients (32.3%) were of normal weight, 71 (3.6%) were underweight, 556 (27.9%) were overweight, and 723 (36.2%) were obese.

The prevalence of obesity was highest in male leukemia survivors (42.5%) and females who survived neuroblastoma (43.6%), followed closely by those who survived leukemia (43.1%).

Multivariable analyses showed that 3 factors were independently associated with an increased risk of obesity: older age at the time of evaluation (≥30 years vs <30 years; P<0.001), undergoing cranial radiation (P<0.001), and receiving glucocorticoids (P=0.004).

On the other hand, receiving chest, abdominal, or pelvic radiation was associated with a decreased risk of obesity (P<0.001).

The researchers also identified 166 single nucleotide polymorphisms that were associated with obesity among cancer survivors who had received cranial radiation. The strongest association was in variants of genes involved in neuron growth, repair, and connectivity.

Among survivors who did not receive cranial radiation, only 1 single nucleotide polymorphism—rs12073359, located on chromosome 1—was associated with an increased risk of obesity.

Dr Wilson said these findings might help us identify the childhood cancer survivors who are most likely to become obese. The results may also provide a foundation for future research efforts aimed at characterizing molecular pathways involved in the link between childhood cancer treatment and obesity.

Researchers have identified several factors that may influence the risk of obesity in childhood cancer survivors.

Previous research showed that obesity rates are elevated in childhood cancer survivors who were exposed to cranial radiation.

But the new study has shown that other types of treatment, a patient’s age, and certain genetic variants are associated with obesity in this population.

Carmen Wilson, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

The researchers evaluated 1,996 childhood cancer survivors treated at St. Jude. The patients’ median age at diagnosis was 7.2 years (range, 0.1-24.8), and their median age at follow-up was 32.4 years (range, 18.9-63.8).

At the time of evaluation, 645 patients (32.3%) were of normal weight, 71 (3.6%) were underweight, 556 (27.9%) were overweight, and 723 (36.2%) were obese.

The prevalence of obesity was highest in male leukemia survivors (42.5%) and females who survived neuroblastoma (43.6%), followed closely by those who survived leukemia (43.1%).

Multivariable analyses showed that 3 factors were independently associated with an increased risk of obesity: older age at the time of evaluation (≥30 years vs <30 years; P<0.001), undergoing cranial radiation (P<0.001), and receiving glucocorticoids (P=0.004).

On the other hand, receiving chest, abdominal, or pelvic radiation was associated with a decreased risk of obesity (P<0.001).

The researchers also identified 166 single nucleotide polymorphisms that were associated with obesity among cancer survivors who had received cranial radiation. The strongest association was in variants of genes involved in neuron growth, repair, and connectivity.

Among survivors who did not receive cranial radiation, only 1 single nucleotide polymorphism—rs12073359, located on chromosome 1—was associated with an increased risk of obesity.

Dr Wilson said these findings might help us identify the childhood cancer survivors who are most likely to become obese. The results may also provide a foundation for future research efforts aimed at characterizing molecular pathways involved in the link between childhood cancer treatment and obesity.

Researchers have identified several factors that may influence the risk of obesity in childhood cancer survivors.

Previous research showed that obesity rates are elevated in childhood cancer survivors who were exposed to cranial radiation.

But the new study has shown that other types of treatment, a patient’s age, and certain genetic variants are associated with obesity in this population.

Carmen Wilson, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

The researchers evaluated 1,996 childhood cancer survivors treated at St. Jude. The patients’ median age at diagnosis was 7.2 years (range, 0.1-24.8), and their median age at follow-up was 32.4 years (range, 18.9-63.8).

At the time of evaluation, 645 patients (32.3%) were of normal weight, 71 (3.6%) were underweight, 556 (27.9%) were overweight, and 723 (36.2%) were obese.

The prevalence of obesity was highest in male leukemia survivors (42.5%) and females who survived neuroblastoma (43.6%), followed closely by those who survived leukemia (43.1%).

Multivariable analyses showed that 3 factors were independently associated with an increased risk of obesity: older age at the time of evaluation (≥30 years vs <30 years; P<0.001), undergoing cranial radiation (P<0.001), and receiving glucocorticoids (P=0.004).

On the other hand, receiving chest, abdominal, or pelvic radiation was associated with a decreased risk of obesity (P<0.001).

The researchers also identified 166 single nucleotide polymorphisms that were associated with obesity among cancer survivors who had received cranial radiation. The strongest association was in variants of genes involved in neuron growth, repair, and connectivity.

Among survivors who did not receive cranial radiation, only 1 single nucleotide polymorphism—rs12073359, located on chromosome 1—was associated with an increased risk of obesity.

Dr Wilson said these findings might help us identify the childhood cancer survivors who are most likely to become obese. The results may also provide a foundation for future research efforts aimed at characterizing molecular pathways involved in the link between childhood cancer treatment and obesity.

GIST patients have higher risk of NHL, other cancers

Photo courtesy of CDC

Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) have an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and other cancers, a new study suggests.

About 1 in 6 of the patients studied were diagnosed with an additional malignancy.

The patients had an increased risk of other sarcomas, NHL, carcinoid tumors, melanoma, and colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, hepatobiliary, non-small cell lung, prostate, and renal cell cancers.

“Only 5% of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors have a hereditary disorder that predisposes them to develop multiple benign and malignant tumors,” said study author Jason K. Sicklick, MD, of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

“The research indicates that these patients may develop cancers outside of these syndromes, but the exact mechanisms are not yet known.”

Dr Sicklick and his colleagues described their research in Cancer.

The team analyzed 6112 GIST patients and found that 1047 of them (17.1%) had additional cancers.

When compared to the general US population, patients had a 44% increased prevalence of cancers occurring before a GIST diagnosis and a 66% higher risk of developing cancers after GIST diagnosis.

That corresponds to a standardized prevalence ratio (SPR) of 1.44 (risk before GIST diagnosis) and a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.66 (risk after GIST diagnosis).

Both before and after GIST diagnosis, patients had a significantly increased risk of NHL (SPR=1.69, SIR=1.76), other sarcomas (SPR=5.24, SIR=4.02), neuroendocrine-carcinoid tumors (SPR=3.56, SIR=4.79), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.51, SIR=2.16).

Before GIST diagnosis, patients had an increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (SPR=12.0), bladder adenocarcinoma (SPR=7.51), melanoma (SPR=1.46), and prostate adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.20).

And after GIST diagnosis, they had an increased risk of ovarian carcinoma (SIR=8.72), small intestine adenocarcinoma (SIR=5.89), papillary thyroid cancer (SIR=5.16), renal cell carcinoma (SIR=4.46), hepatobiliary adenocarcinoma (SIR=3.10), gastric adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.70), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.03), uterine adenocarcinoma (SIR=1.96), non-small cell lung cancer (SIR=1.74), and transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (SIR=1.65).

The researchers said further studies are needed to understand the connection between GIST and other cancers, but these findings may have clinical implications.

“Patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumors may warrant consideration for additional screenings based on the other cancers that they are most susceptible to contract,” said James D. Murphy, MD, also of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

Photo courtesy of CDC

Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) have an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and other cancers, a new study suggests.

About 1 in 6 of the patients studied were diagnosed with an additional malignancy.

The patients had an increased risk of other sarcomas, NHL, carcinoid tumors, melanoma, and colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, hepatobiliary, non-small cell lung, prostate, and renal cell cancers.

“Only 5% of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors have a hereditary disorder that predisposes them to develop multiple benign and malignant tumors,” said study author Jason K. Sicklick, MD, of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

“The research indicates that these patients may develop cancers outside of these syndromes, but the exact mechanisms are not yet known.”

Dr Sicklick and his colleagues described their research in Cancer.

The team analyzed 6112 GIST patients and found that 1047 of them (17.1%) had additional cancers.

When compared to the general US population, patients had a 44% increased prevalence of cancers occurring before a GIST diagnosis and a 66% higher risk of developing cancers after GIST diagnosis.

That corresponds to a standardized prevalence ratio (SPR) of 1.44 (risk before GIST diagnosis) and a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.66 (risk after GIST diagnosis).

Both before and after GIST diagnosis, patients had a significantly increased risk of NHL (SPR=1.69, SIR=1.76), other sarcomas (SPR=5.24, SIR=4.02), neuroendocrine-carcinoid tumors (SPR=3.56, SIR=4.79), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.51, SIR=2.16).

Before GIST diagnosis, patients had an increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (SPR=12.0), bladder adenocarcinoma (SPR=7.51), melanoma (SPR=1.46), and prostate adenocarcinoma (SPR=1.20).

And after GIST diagnosis, they had an increased risk of ovarian carcinoma (SIR=8.72), small intestine adenocarcinoma (SIR=5.89), papillary thyroid cancer (SIR=5.16), renal cell carcinoma (SIR=4.46), hepatobiliary adenocarcinoma (SIR=3.10), gastric adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.70), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (SIR=2.03), uterine adenocarcinoma (SIR=1.96), non-small cell lung cancer (SIR=1.74), and transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (SIR=1.65).

The researchers said further studies are needed to understand the connection between GIST and other cancers, but these findings may have clinical implications.

“Patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumors may warrant consideration for additional screenings based on the other cancers that they are most susceptible to contract,” said James D. Murphy, MD, also of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

Photo courtesy of CDC

Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) have an increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and other cancers, a new study suggests.

About 1 in 6 of the patients studied were diagnosed with an additional malignancy.

The patients had an increased risk of other sarcomas, NHL, carcinoid tumors, melanoma, and colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, hepatobiliary, non-small cell lung, prostate, and renal cell cancers.

“Only 5% of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors have a hereditary disorder that predisposes them to develop multiple benign and malignant tumors,” said study author Jason K. Sicklick, MD, of the University of California San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

“The research indicates that these patients may develop cancers outside of these syndromes, but the exact mechanisms are not yet known.”

Dr Sicklick and his colleagues described their research in Cancer.

The team analyzed 6112 GIST patients and found that 1047 of them (17.1%) had additional cancers.

When compared to the general US population, patients had a 44% increased prevalence of cancers occurring before a GIST diagnosis and a 66% higher risk of developing cancers after GIST diagnosis.

That corresponds to a standardized prevalence ratio (SPR) of 1.44 (risk before GIST diagnosis) and a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.66 (risk after GIST diagnosis).