User login

Easing dementia caregiver burden, addressing interpersonal violence

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

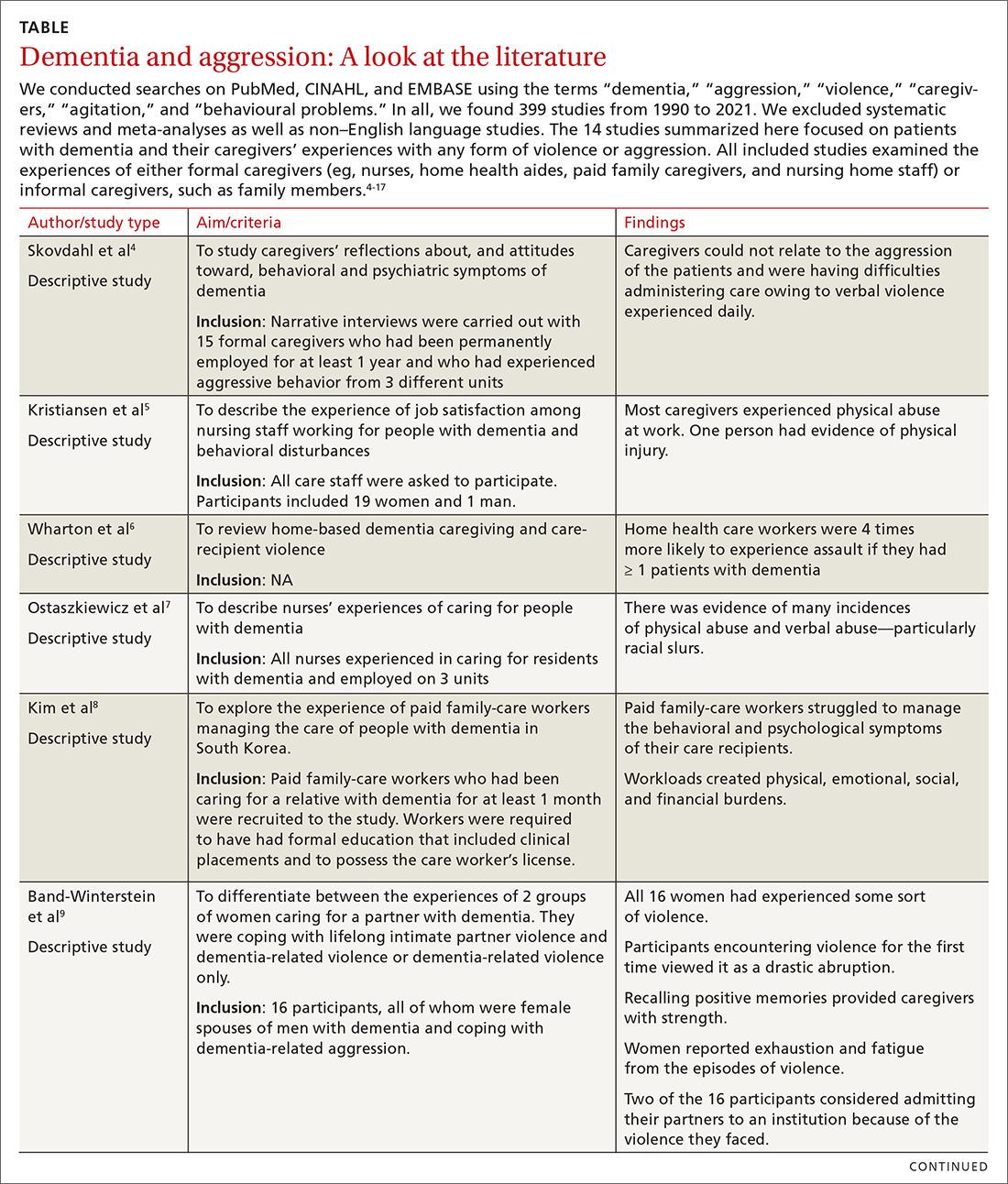

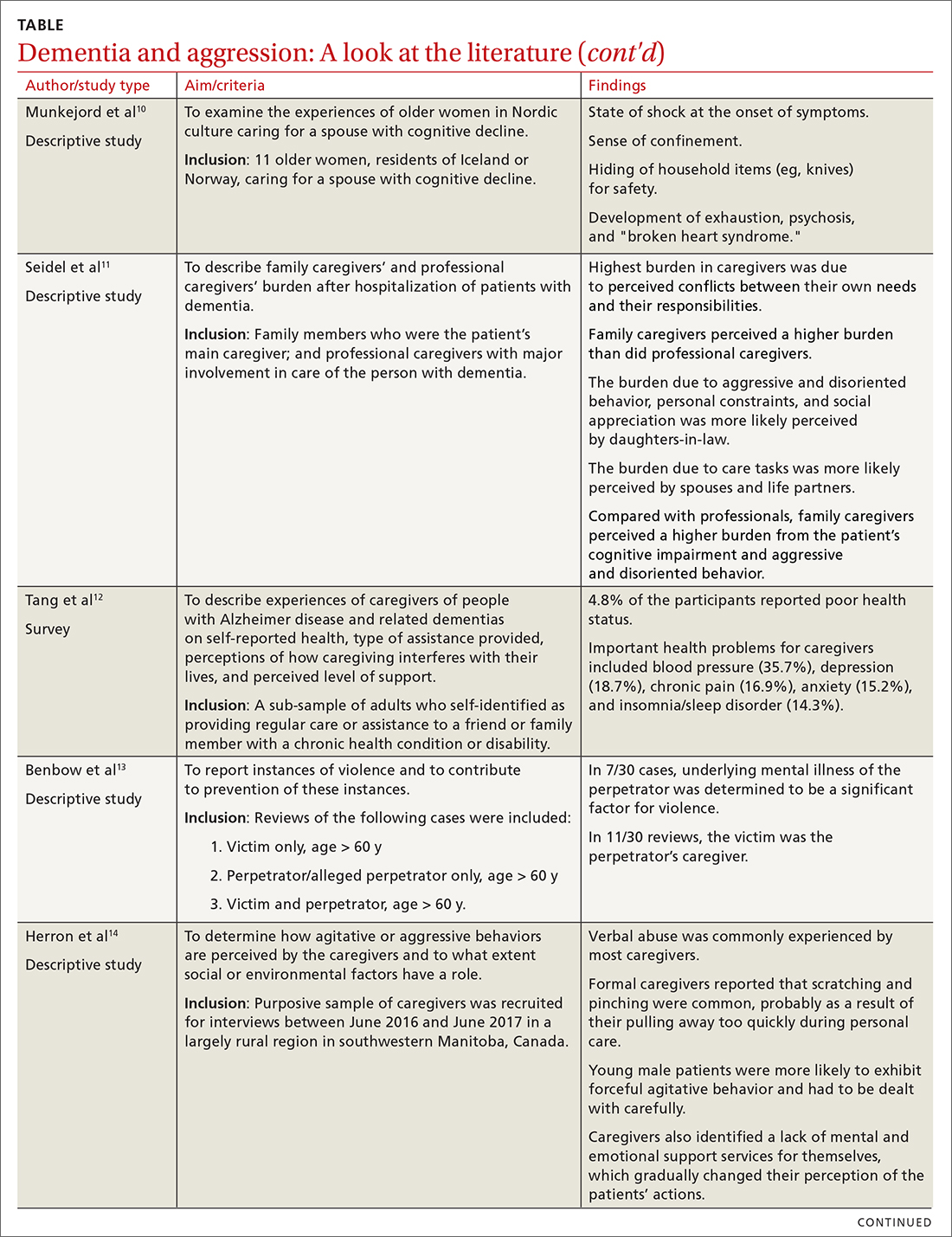

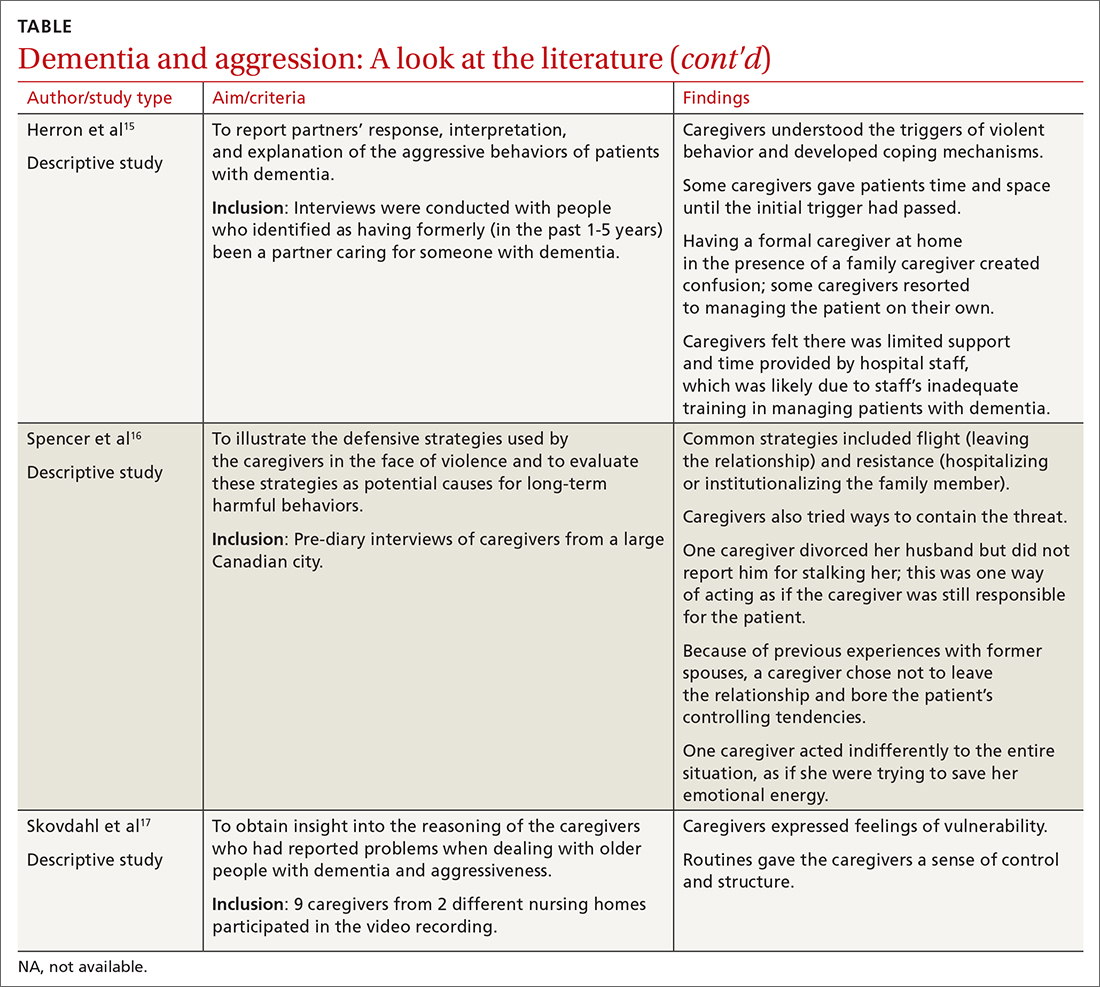

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of PTSD with depression, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder/dependence, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was brought to his PCP by his wife. She said he had recently been unable to keep appointment times, pay bills, or take his usual medications, venlafaxine and bupropion. She also said his PTSD symptoms had worsened. He was sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day and was increasingly irritable. The patient denied any concerns or changes in his behavior.

The PCP administered a Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination to screen for cognitive impairment.19 The patient scored 14/30 (less than 20 is indicative of dementia). He was unable to complete a simple math problem, recall any items from a list of 5, count in reverse, draw a clock correctly, or recall a full story. Throughout the exam, the patient demonstrated minimal effort and was often only able to complete a task after further prompting by the examiner.

A computed tomography scan of the head revealed no signs of hemorrhage or damage. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and vitamin B12 levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin test result was negative. The patient was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Donepezil was added to the patient’s medications, starting at 5 mg and then increased to 10 mg. His wife began to assist him with his tasks of daily living. His mood improved, and his wife noted he began to remember his appointments and take his medications with assistance.

However, the patient’s irritability continued to escalate. He grew paranoid and accused his wife of mismanaging their money. This pattern steadily worsened over the course of 6 months. The situation escalated until one day the patient’s wife called a mental health hotline reporting that her husband was holding her hostage and threatening to kill her with a gun. He told her, “I can do something to you, and they won’t even find a fingernail. It doesn’t have to be with a gun either.” She was counseled to try to stay calm to avoid aggravating the situation and to go to a safe place and stay there until help arrived.

His memory had worsened to the point that he could not recall any events from the previous 2 years. He was paranoid about anyone entering his home and would not allow his deteriorating roof to be repaired or his yard to be maintained. He did not shower for weeks at a time. He slept holding a rifle and accused his wife of embezzlement.

Continue to: The patient was evaluated...

The patient was evaluated by another specialist, who assessed his SLUMS score to be 18/30. He increased the patient’s donepezil dose, initiated a bupropion taper, and added sertraline to the regimen. The PCP spoke to the patient’s wife regarding options for her safety including leaving the home, hiding firearms, and calling the police in cases of interpersonal violence. The wife said she did not want to pursue these options. She expressed worry that he might be harmed if he was uncooperative with the police and said there was no one except her to take care of him.

Caregivers struggle to care for their loved ones

Instances of personal violence lead to shock, astonishment, heartbreak, and fear. Anticipation of a recurrence of violence causes many partners and caregivers to feel exhausted, because there is minimal hope for any chance of improvement. There are a few exceptions, however, as our case will show. In addition to emotional exhaustion, there is also a never-ending sense of self-doubt, leading many caregivers to question their ability to handle their family member.20,21 Over time, this leads to caregiver burnout, leaving them unable to understand their family member’s aggression. The sudden loss of caregiver control in dealing with the patient may also result in the family member exhibiting behavioral changes reflecting emotional trauma. For caregivers who do not live with the patient, they may choose to make fewer or shorter visits—or not visit at all—because they fear being abused.7,22

Caregivers of patients with dementia often feel helpless and powerless once abrupt and drastic changes in personality lead to some form of interpersonal violence. Additionally, caregivers with a poor health status are more likely to have lower physical function and experience greater caregiving stress overall.23 Other factors increasing stress are longer years of caregiving and the severity of a patient’s dementia and functional impairment.23

Interventions to reduce caregiver burden

Many studies have assessed the role of different interventions to reduce caregiver burden, such as teaching them problem-solving skills, increasing their knowledge of dementia, recommending social resources, providing emotional support, changing caregiver perceptions of the care situation, introducing coping strategies, relying on strengths and experiences in caregiving, help-seeking, and engaging in activity programs.24-28 For Hispanic caregivers, a structured and self-paced online telenovela format has been effective in improving care and relieving caregiver stress.29 Online positive emotion regulators helped in significantly improving quality of life and physical health in the caregivers.30 In this last intervention, caregivers had 6 online sessions with a facilitator who taught them emotional regulation skills that included: noticing positive events, capitalizing on them, and feeling gratitude; practicing mindfulness; doing a positive reappraisal; acknowledging personal strengths and setting attainable goals; and performing acts of kindness. Empowerment programs have also shown significant improvement in the well-being of caregivers.31

Caregivers may reject support.

Continue to: These practical tips can help

These practical tips can help

Based on our review of the literature, we recommend offering the following supports to caregivers:

- Counsel caregivers early on in a patient’s dementia that behavior changes are likely and may be unpredictable. Explain that dementia can involve changes to personality and behavior as well as memory difficulties.33,34

- Describe resources for support, such as day programs for senior adults, insurance coverage for caregiver respite programs, and the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org/). Encourage caregivers to seek general medical and mental health care for themselves. Caregivers should have opportunities and support to discuss their experiences and to be appropriately trained for the challenge of caring for a family member with dementia.35

- Encourage disclosure about abrupt changes in the patient’s behavior. This invites families to discuss issues with you and may make them more comfortable with such conversations.

- Involve ancillary services (eg, social worker) to plan for a higher level of care well in advance of it becoming necessary.

- Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter a patient’s set routines such as bedtimes and mealtimes.33,34

- Discuss when and how to involve law enforcement, if necessary.33,34 Emphasize the importance of removing firearms from the home as a safety measure. Although federal laws do not explicitly prohibit possession of arms by patients with neurologic damage, a few states mention “organic brain syndrome” or “dementia” as conditions prohibiting use or possession of firearms.36

- Suggest, as feasible, nonpharmacologic aids for the patient such as massage therapy, animal-assisted therapy, personalized interventions, music therapy, and light therapy.37 Prescribe medications to the patient to aid in behavior modification when appropriate.

- Screen caregivers and family members for signs of interpersonal violence. Take notice of changes in caregiver behavior or irregularity in attending follow-up appointments.

CASE

Over the next month, the patient’s symptoms further deteriorated. His PCP recommended hospitalization, but the patient and his wife declined. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain revealed severe confluent and patchy regions of white matter and T2 signal hyperintensity, consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. An old, small, left parietal lobe infarct was also noted.

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department. His symptoms were largely unchanged, but his wife indicated that she could no longer live at home due to burnout. The patient’s medications were adjusted, but he was not admitted for inpatient care. His wife said they needed help at home, but the patient opposed the idea any time that it was mentioned.

A few weeks later, the patient presented for outpatient follow-up. He was delusional, believing that the government was compelling citizens to take sertraline in order to harm their mental health. He had also begun viewing online pornography in front of his wife and attempting to remove all of his money from the bank. He was prescribed aripiprazole 15 mg, and his symptoms began to improve. Soon after, however, he threatened to kill his grandson, then took all his Lasix pills (a 7-day supply) simultaneously. The patient denied that this was a suicide attempt.

Over the course of the next month, the patient began to report hearing voices. A neuropsychological evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia with psychiatric symptoms due to neurologic injury. The patient was referred to a geriatric psychiatrist and continued to be managed medically. He was assigned a multidisciplinary team comprising palliative care, social work, and care management to assist in his care and provide support to the family. His behavior improved.

Continue to: At the time of this publication...

At the time of this publication, the patient’s irritability and paranoia had subsided and he had made no further threats to his family. He has allowed a home health aide into the house and has agreed to have his roof repaired. His wife still lives with him and assists him with activities of daily living.

Interprofessional teams are key

Caregiver burnout increases the risk of patient neglect or abuse, as individuals who have been the targets of aggressive behavior are more likely to leave demented patients unattended.8,16,23 Although tools are available to screen caregivers for depression and burnout, an important step forward would be to develop an interprofessional team to aid in identifying and closely following high-risk patient–caregiver groups. This continual and varied assessment of psychosocial stressors could help prevent the development of violent interactions. These teams would allow integration with the primary health care system by frequent and effective shared communication of knowledge, development of goals, and shared decision-making.38 Setting expectations, providing support, and discussing safety strategies can improve the health and welfare of caregivers and patients with dementia alike.

CORRESPONDENCE

Abu Baker Sheikh, MD, MSC 10-5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; absheikh@salud.unm.edu.

1. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327-339.

2. Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, et al. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:111-115.

3. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, et al. Violent and criminal manifestations in dementia patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:541-549.

4. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia—narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:277-286.

5. Kristiansen L, Hellzén O, Asplund K. Swedish assistant nurses’ experiences of job satisfaction when caring for persons suffering from dementia and behavioural disturbances. An interview study. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-being. 2006;1:245-256.

6. Wharton TC, Ford BK. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:460-477.

7. Ostaszkiewicz J, Lakhan P, O’Connell B, et al. Ongoing challenges responding to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:506-516.

8. Kim J, De Bellis AM, Xiao LD. The experience of paid family-care workers of people with dementia in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12:34-41.

9. Band-Winterstein T, Avieli H. Women coping with a partner’s dementia-related violence: a qualitative study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019; 51:368-379.

10. Munkejord MC, Stefansdottir OA, Sveinbjarnardottir EK. Who cares for the carer? The suffering, struggles and unmet needs of older women caring for husbands living with cognitive decline. Int Pract Devel J. 2020;10:1-11.

11. Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655-663.

12. Tang W, Friedman DB, Kannaley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers by care recipient’s health condition: a study of caregivers for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias versus other chronic conditions. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:181-184.

13. Benbow SM, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Older adults and violence: an analysis of domestic homicide reviews in England involving adults over 60 years of age. Ageing Soc. 2018;39:1097-1121.

14. Herron RV, Wrathall MA. Putting responsive behaviours in place: examining how formal and informal carers understand the actions of people with dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:9-15.

15. Herron RV, Rosenberg MW. Responding to aggression and reactive behaviours in the home. Dementia (London). 2019;18:1328-1340.

16. Spencer D, Funk LM, Herron RV, et al. Fear, defensive strategies and caring for cognitively impaired family members. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:67-85.

17. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Dementia and aggressiveness: stimulated recall interviews with caregivers after video-recorded interactions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:515-525.

18. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:283-296.

19. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) - a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;14:900-910.

20. Janzen S, Zecevic AA, Kloseck M, et al. Managing agitation using nonpharmacological interventions for seniors with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:524-532.

21. Zeller A, Dassen T, Kok G, et al. Nursing home caregivers’ explanations for and coping strategies with residents’ aggression: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2469-2478.

22. Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: homecare. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

23. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Refining caregiver vulnerability for clinical practice: determinants of self-rated health in spousal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:18.

24. Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 15:20-25.

25. Wawrziczny E, Larochette C, Papo D, et al. A customized intervention for dementia caregivers: a quasi-experimental design. J Aging Health. 2019;31:1172-1195.

26. Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, et al. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:92-102.

27. de Oliveira AM, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, et al. An intervention to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia: preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program-outpatient version. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1301-1307.

28. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6276.

29. Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, et al. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:209-216.

30. Moskowitz JT, Cheung EO, Snowberg KE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019;38:391-402.

31. Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37:222-233.

32. Zwingmann I, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Esser A, et al. Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:121.

33. Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T. Caregivers’ perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2713-2726.

34. Nakaishi L, Moss H, Weinstein M, et al. Exploring workplace violence among home care workers in a consumer-driven home health care program. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61:441-450.

35. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1-98.

36. Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, et al. Firearms and dementia: clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:47-49.

37. Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103489.

38. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230.

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of PTSD with depression, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder/dependence, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was brought to his PCP by his wife. She said he had recently been unable to keep appointment times, pay bills, or take his usual medications, venlafaxine and bupropion. She also said his PTSD symptoms had worsened. He was sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day and was increasingly irritable. The patient denied any concerns or changes in his behavior.

The PCP administered a Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination to screen for cognitive impairment.19 The patient scored 14/30 (less than 20 is indicative of dementia). He was unable to complete a simple math problem, recall any items from a list of 5, count in reverse, draw a clock correctly, or recall a full story. Throughout the exam, the patient demonstrated minimal effort and was often only able to complete a task after further prompting by the examiner.

A computed tomography scan of the head revealed no signs of hemorrhage or damage. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and vitamin B12 levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin test result was negative. The patient was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Donepezil was added to the patient’s medications, starting at 5 mg and then increased to 10 mg. His wife began to assist him with his tasks of daily living. His mood improved, and his wife noted he began to remember his appointments and take his medications with assistance.

However, the patient’s irritability continued to escalate. He grew paranoid and accused his wife of mismanaging their money. This pattern steadily worsened over the course of 6 months. The situation escalated until one day the patient’s wife called a mental health hotline reporting that her husband was holding her hostage and threatening to kill her with a gun. He told her, “I can do something to you, and they won’t even find a fingernail. It doesn’t have to be with a gun either.” She was counseled to try to stay calm to avoid aggravating the situation and to go to a safe place and stay there until help arrived.

His memory had worsened to the point that he could not recall any events from the previous 2 years. He was paranoid about anyone entering his home and would not allow his deteriorating roof to be repaired or his yard to be maintained. He did not shower for weeks at a time. He slept holding a rifle and accused his wife of embezzlement.

Continue to: The patient was evaluated...

The patient was evaluated by another specialist, who assessed his SLUMS score to be 18/30. He increased the patient’s donepezil dose, initiated a bupropion taper, and added sertraline to the regimen. The PCP spoke to the patient’s wife regarding options for her safety including leaving the home, hiding firearms, and calling the police in cases of interpersonal violence. The wife said she did not want to pursue these options. She expressed worry that he might be harmed if he was uncooperative with the police and said there was no one except her to take care of him.

Caregivers struggle to care for their loved ones

Instances of personal violence lead to shock, astonishment, heartbreak, and fear. Anticipation of a recurrence of violence causes many partners and caregivers to feel exhausted, because there is minimal hope for any chance of improvement. There are a few exceptions, however, as our case will show. In addition to emotional exhaustion, there is also a never-ending sense of self-doubt, leading many caregivers to question their ability to handle their family member.20,21 Over time, this leads to caregiver burnout, leaving them unable to understand their family member’s aggression. The sudden loss of caregiver control in dealing with the patient may also result in the family member exhibiting behavioral changes reflecting emotional trauma. For caregivers who do not live with the patient, they may choose to make fewer or shorter visits—or not visit at all—because they fear being abused.7,22

Caregivers of patients with dementia often feel helpless and powerless once abrupt and drastic changes in personality lead to some form of interpersonal violence. Additionally, caregivers with a poor health status are more likely to have lower physical function and experience greater caregiving stress overall.23 Other factors increasing stress are longer years of caregiving and the severity of a patient’s dementia and functional impairment.23

Interventions to reduce caregiver burden

Many studies have assessed the role of different interventions to reduce caregiver burden, such as teaching them problem-solving skills, increasing their knowledge of dementia, recommending social resources, providing emotional support, changing caregiver perceptions of the care situation, introducing coping strategies, relying on strengths and experiences in caregiving, help-seeking, and engaging in activity programs.24-28 For Hispanic caregivers, a structured and self-paced online telenovela format has been effective in improving care and relieving caregiver stress.29 Online positive emotion regulators helped in significantly improving quality of life and physical health in the caregivers.30 In this last intervention, caregivers had 6 online sessions with a facilitator who taught them emotional regulation skills that included: noticing positive events, capitalizing on them, and feeling gratitude; practicing mindfulness; doing a positive reappraisal; acknowledging personal strengths and setting attainable goals; and performing acts of kindness. Empowerment programs have also shown significant improvement in the well-being of caregivers.31

Caregivers may reject support.

Continue to: These practical tips can help

These practical tips can help

Based on our review of the literature, we recommend offering the following supports to caregivers:

- Counsel caregivers early on in a patient’s dementia that behavior changes are likely and may be unpredictable. Explain that dementia can involve changes to personality and behavior as well as memory difficulties.33,34

- Describe resources for support, such as day programs for senior adults, insurance coverage for caregiver respite programs, and the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org/). Encourage caregivers to seek general medical and mental health care for themselves. Caregivers should have opportunities and support to discuss their experiences and to be appropriately trained for the challenge of caring for a family member with dementia.35

- Encourage disclosure about abrupt changes in the patient’s behavior. This invites families to discuss issues with you and may make them more comfortable with such conversations.

- Involve ancillary services (eg, social worker) to plan for a higher level of care well in advance of it becoming necessary.

- Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter a patient’s set routines such as bedtimes and mealtimes.33,34

- Discuss when and how to involve law enforcement, if necessary.33,34 Emphasize the importance of removing firearms from the home as a safety measure. Although federal laws do not explicitly prohibit possession of arms by patients with neurologic damage, a few states mention “organic brain syndrome” or “dementia” as conditions prohibiting use or possession of firearms.36

- Suggest, as feasible, nonpharmacologic aids for the patient such as massage therapy, animal-assisted therapy, personalized interventions, music therapy, and light therapy.37 Prescribe medications to the patient to aid in behavior modification when appropriate.

- Screen caregivers and family members for signs of interpersonal violence. Take notice of changes in caregiver behavior or irregularity in attending follow-up appointments.

CASE

Over the next month, the patient’s symptoms further deteriorated. His PCP recommended hospitalization, but the patient and his wife declined. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain revealed severe confluent and patchy regions of white matter and T2 signal hyperintensity, consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. An old, small, left parietal lobe infarct was also noted.

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department. His symptoms were largely unchanged, but his wife indicated that she could no longer live at home due to burnout. The patient’s medications were adjusted, but he was not admitted for inpatient care. His wife said they needed help at home, but the patient opposed the idea any time that it was mentioned.

A few weeks later, the patient presented for outpatient follow-up. He was delusional, believing that the government was compelling citizens to take sertraline in order to harm their mental health. He had also begun viewing online pornography in front of his wife and attempting to remove all of his money from the bank. He was prescribed aripiprazole 15 mg, and his symptoms began to improve. Soon after, however, he threatened to kill his grandson, then took all his Lasix pills (a 7-day supply) simultaneously. The patient denied that this was a suicide attempt.

Over the course of the next month, the patient began to report hearing voices. A neuropsychological evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia with psychiatric symptoms due to neurologic injury. The patient was referred to a geriatric psychiatrist and continued to be managed medically. He was assigned a multidisciplinary team comprising palliative care, social work, and care management to assist in his care and provide support to the family. His behavior improved.

Continue to: At the time of this publication...

At the time of this publication, the patient’s irritability and paranoia had subsided and he had made no further threats to his family. He has allowed a home health aide into the house and has agreed to have his roof repaired. His wife still lives with him and assists him with activities of daily living.

Interprofessional teams are key

Caregiver burnout increases the risk of patient neglect or abuse, as individuals who have been the targets of aggressive behavior are more likely to leave demented patients unattended.8,16,23 Although tools are available to screen caregivers for depression and burnout, an important step forward would be to develop an interprofessional team to aid in identifying and closely following high-risk patient–caregiver groups. This continual and varied assessment of psychosocial stressors could help prevent the development of violent interactions. These teams would allow integration with the primary health care system by frequent and effective shared communication of knowledge, development of goals, and shared decision-making.38 Setting expectations, providing support, and discussing safety strategies can improve the health and welfare of caregivers and patients with dementia alike.

CORRESPONDENCE

Abu Baker Sheikh, MD, MSC 10-5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; absheikh@salud.unm.edu.

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of PTSD with depression, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder/dependence, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was brought to his PCP by his wife. She said he had recently been unable to keep appointment times, pay bills, or take his usual medications, venlafaxine and bupropion. She also said his PTSD symptoms had worsened. He was sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day and was increasingly irritable. The patient denied any concerns or changes in his behavior.

The PCP administered a Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination to screen for cognitive impairment.19 The patient scored 14/30 (less than 20 is indicative of dementia). He was unable to complete a simple math problem, recall any items from a list of 5, count in reverse, draw a clock correctly, or recall a full story. Throughout the exam, the patient demonstrated minimal effort and was often only able to complete a task after further prompting by the examiner.

A computed tomography scan of the head revealed no signs of hemorrhage or damage. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and vitamin B12 levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin test result was negative. The patient was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Donepezil was added to the patient’s medications, starting at 5 mg and then increased to 10 mg. His wife began to assist him with his tasks of daily living. His mood improved, and his wife noted he began to remember his appointments and take his medications with assistance.

However, the patient’s irritability continued to escalate. He grew paranoid and accused his wife of mismanaging their money. This pattern steadily worsened over the course of 6 months. The situation escalated until one day the patient’s wife called a mental health hotline reporting that her husband was holding her hostage and threatening to kill her with a gun. He told her, “I can do something to you, and they won’t even find a fingernail. It doesn’t have to be with a gun either.” She was counseled to try to stay calm to avoid aggravating the situation and to go to a safe place and stay there until help arrived.

His memory had worsened to the point that he could not recall any events from the previous 2 years. He was paranoid about anyone entering his home and would not allow his deteriorating roof to be repaired or his yard to be maintained. He did not shower for weeks at a time. He slept holding a rifle and accused his wife of embezzlement.

Continue to: The patient was evaluated...

The patient was evaluated by another specialist, who assessed his SLUMS score to be 18/30. He increased the patient’s donepezil dose, initiated a bupropion taper, and added sertraline to the regimen. The PCP spoke to the patient’s wife regarding options for her safety including leaving the home, hiding firearms, and calling the police in cases of interpersonal violence. The wife said she did not want to pursue these options. She expressed worry that he might be harmed if he was uncooperative with the police and said there was no one except her to take care of him.

Caregivers struggle to care for their loved ones

Instances of personal violence lead to shock, astonishment, heartbreak, and fear. Anticipation of a recurrence of violence causes many partners and caregivers to feel exhausted, because there is minimal hope for any chance of improvement. There are a few exceptions, however, as our case will show. In addition to emotional exhaustion, there is also a never-ending sense of self-doubt, leading many caregivers to question their ability to handle their family member.20,21 Over time, this leads to caregiver burnout, leaving them unable to understand their family member’s aggression. The sudden loss of caregiver control in dealing with the patient may also result in the family member exhibiting behavioral changes reflecting emotional trauma. For caregivers who do not live with the patient, they may choose to make fewer or shorter visits—or not visit at all—because they fear being abused.7,22

Caregivers of patients with dementia often feel helpless and powerless once abrupt and drastic changes in personality lead to some form of interpersonal violence. Additionally, caregivers with a poor health status are more likely to have lower physical function and experience greater caregiving stress overall.23 Other factors increasing stress are longer years of caregiving and the severity of a patient’s dementia and functional impairment.23

Interventions to reduce caregiver burden

Many studies have assessed the role of different interventions to reduce caregiver burden, such as teaching them problem-solving skills, increasing their knowledge of dementia, recommending social resources, providing emotional support, changing caregiver perceptions of the care situation, introducing coping strategies, relying on strengths and experiences in caregiving, help-seeking, and engaging in activity programs.24-28 For Hispanic caregivers, a structured and self-paced online telenovela format has been effective in improving care and relieving caregiver stress.29 Online positive emotion regulators helped in significantly improving quality of life and physical health in the caregivers.30 In this last intervention, caregivers had 6 online sessions with a facilitator who taught them emotional regulation skills that included: noticing positive events, capitalizing on them, and feeling gratitude; practicing mindfulness; doing a positive reappraisal; acknowledging personal strengths and setting attainable goals; and performing acts of kindness. Empowerment programs have also shown significant improvement in the well-being of caregivers.31

Caregivers may reject support.

Continue to: These practical tips can help

These practical tips can help

Based on our review of the literature, we recommend offering the following supports to caregivers:

- Counsel caregivers early on in a patient’s dementia that behavior changes are likely and may be unpredictable. Explain that dementia can involve changes to personality and behavior as well as memory difficulties.33,34

- Describe resources for support, such as day programs for senior adults, insurance coverage for caregiver respite programs, and the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org/). Encourage caregivers to seek general medical and mental health care for themselves. Caregivers should have opportunities and support to discuss their experiences and to be appropriately trained for the challenge of caring for a family member with dementia.35

- Encourage disclosure about abrupt changes in the patient’s behavior. This invites families to discuss issues with you and may make them more comfortable with such conversations.

- Involve ancillary services (eg, social worker) to plan for a higher level of care well in advance of it becoming necessary.

- Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter a patient’s set routines such as bedtimes and mealtimes.33,34

- Discuss when and how to involve law enforcement, if necessary.33,34 Emphasize the importance of removing firearms from the home as a safety measure. Although federal laws do not explicitly prohibit possession of arms by patients with neurologic damage, a few states mention “organic brain syndrome” or “dementia” as conditions prohibiting use or possession of firearms.36

- Suggest, as feasible, nonpharmacologic aids for the patient such as massage therapy, animal-assisted therapy, personalized interventions, music therapy, and light therapy.37 Prescribe medications to the patient to aid in behavior modification when appropriate.

- Screen caregivers and family members for signs of interpersonal violence. Take notice of changes in caregiver behavior or irregularity in attending follow-up appointments.

CASE

Over the next month, the patient’s symptoms further deteriorated. His PCP recommended hospitalization, but the patient and his wife declined. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain revealed severe confluent and patchy regions of white matter and T2 signal hyperintensity, consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. An old, small, left parietal lobe infarct was also noted.

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department. His symptoms were largely unchanged, but his wife indicated that she could no longer live at home due to burnout. The patient’s medications were adjusted, but he was not admitted for inpatient care. His wife said they needed help at home, but the patient opposed the idea any time that it was mentioned.

A few weeks later, the patient presented for outpatient follow-up. He was delusional, believing that the government was compelling citizens to take sertraline in order to harm their mental health. He had also begun viewing online pornography in front of his wife and attempting to remove all of his money from the bank. He was prescribed aripiprazole 15 mg, and his symptoms began to improve. Soon after, however, he threatened to kill his grandson, then took all his Lasix pills (a 7-day supply) simultaneously. The patient denied that this was a suicide attempt.

Over the course of the next month, the patient began to report hearing voices. A neuropsychological evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia with psychiatric symptoms due to neurologic injury. The patient was referred to a geriatric psychiatrist and continued to be managed medically. He was assigned a multidisciplinary team comprising palliative care, social work, and care management to assist in his care and provide support to the family. His behavior improved.

Continue to: At the time of this publication...

At the time of this publication, the patient’s irritability and paranoia had subsided and he had made no further threats to his family. He has allowed a home health aide into the house and has agreed to have his roof repaired. His wife still lives with him and assists him with activities of daily living.

Interprofessional teams are key

Caregiver burnout increases the risk of patient neglect or abuse, as individuals who have been the targets of aggressive behavior are more likely to leave demented patients unattended.8,16,23 Although tools are available to screen caregivers for depression and burnout, an important step forward would be to develop an interprofessional team to aid in identifying and closely following high-risk patient–caregiver groups. This continual and varied assessment of psychosocial stressors could help prevent the development of violent interactions. These teams would allow integration with the primary health care system by frequent and effective shared communication of knowledge, development of goals, and shared decision-making.38 Setting expectations, providing support, and discussing safety strategies can improve the health and welfare of caregivers and patients with dementia alike.

CORRESPONDENCE

Abu Baker Sheikh, MD, MSC 10-5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; absheikh@salud.unm.edu.

1. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327-339.

2. Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, et al. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:111-115.

3. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, et al. Violent and criminal manifestations in dementia patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:541-549.

4. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia—narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:277-286.

5. Kristiansen L, Hellzén O, Asplund K. Swedish assistant nurses’ experiences of job satisfaction when caring for persons suffering from dementia and behavioural disturbances. An interview study. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-being. 2006;1:245-256.

6. Wharton TC, Ford BK. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:460-477.

7. Ostaszkiewicz J, Lakhan P, O’Connell B, et al. Ongoing challenges responding to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:506-516.

8. Kim J, De Bellis AM, Xiao LD. The experience of paid family-care workers of people with dementia in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12:34-41.

9. Band-Winterstein T, Avieli H. Women coping with a partner’s dementia-related violence: a qualitative study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019; 51:368-379.

10. Munkejord MC, Stefansdottir OA, Sveinbjarnardottir EK. Who cares for the carer? The suffering, struggles and unmet needs of older women caring for husbands living with cognitive decline. Int Pract Devel J. 2020;10:1-11.

11. Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655-663.

12. Tang W, Friedman DB, Kannaley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers by care recipient’s health condition: a study of caregivers for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias versus other chronic conditions. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:181-184.

13. Benbow SM, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Older adults and violence: an analysis of domestic homicide reviews in England involving adults over 60 years of age. Ageing Soc. 2018;39:1097-1121.

14. Herron RV, Wrathall MA. Putting responsive behaviours in place: examining how formal and informal carers understand the actions of people with dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:9-15.

15. Herron RV, Rosenberg MW. Responding to aggression and reactive behaviours in the home. Dementia (London). 2019;18:1328-1340.

16. Spencer D, Funk LM, Herron RV, et al. Fear, defensive strategies and caring for cognitively impaired family members. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:67-85.

17. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Dementia and aggressiveness: stimulated recall interviews with caregivers after video-recorded interactions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:515-525.

18. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:283-296.

19. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) - a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;14:900-910.

20. Janzen S, Zecevic AA, Kloseck M, et al. Managing agitation using nonpharmacological interventions for seniors with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:524-532.

21. Zeller A, Dassen T, Kok G, et al. Nursing home caregivers’ explanations for and coping strategies with residents’ aggression: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2469-2478.

22. Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: homecare. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

23. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Refining caregiver vulnerability for clinical practice: determinants of self-rated health in spousal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:18.

24. Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 15:20-25.

25. Wawrziczny E, Larochette C, Papo D, et al. A customized intervention for dementia caregivers: a quasi-experimental design. J Aging Health. 2019;31:1172-1195.

26. Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, et al. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:92-102.

27. de Oliveira AM, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, et al. An intervention to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia: preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program-outpatient version. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1301-1307.

28. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6276.

29. Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, et al. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:209-216.

30. Moskowitz JT, Cheung EO, Snowberg KE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019;38:391-402.

31. Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37:222-233.

32. Zwingmann I, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Esser A, et al. Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:121.

33. Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T. Caregivers’ perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2713-2726.

34. Nakaishi L, Moss H, Weinstein M, et al. Exploring workplace violence among home care workers in a consumer-driven home health care program. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61:441-450.

35. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1-98.

36. Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, et al. Firearms and dementia: clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:47-49.

37. Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103489.

38. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230.

1. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327-339.

2. Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, et al. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:111-115.

3. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, et al. Violent and criminal manifestations in dementia patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:541-549.

4. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia—narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:277-286.

5. Kristiansen L, Hellzén O, Asplund K. Swedish assistant nurses’ experiences of job satisfaction when caring for persons suffering from dementia and behavioural disturbances. An interview study. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-being. 2006;1:245-256.

6. Wharton TC, Ford BK. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:460-477.

7. Ostaszkiewicz J, Lakhan P, O’Connell B, et al. Ongoing challenges responding to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:506-516.

8. Kim J, De Bellis AM, Xiao LD. The experience of paid family-care workers of people with dementia in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12:34-41.

9. Band-Winterstein T, Avieli H. Women coping with a partner’s dementia-related violence: a qualitative study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019; 51:368-379.

10. Munkejord MC, Stefansdottir OA, Sveinbjarnardottir EK. Who cares for the carer? The suffering, struggles and unmet needs of older women caring for husbands living with cognitive decline. Int Pract Devel J. 2020;10:1-11.

11. Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655-663.

12. Tang W, Friedman DB, Kannaley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers by care recipient’s health condition: a study of caregivers for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias versus other chronic conditions. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:181-184.

13. Benbow SM, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Older adults and violence: an analysis of domestic homicide reviews in England involving adults over 60 years of age. Ageing Soc. 2018;39:1097-1121.

14. Herron RV, Wrathall MA. Putting responsive behaviours in place: examining how formal and informal carers understand the actions of people with dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:9-15.

15. Herron RV, Rosenberg MW. Responding to aggression and reactive behaviours in the home. Dementia (London). 2019;18:1328-1340.

16. Spencer D, Funk LM, Herron RV, et al. Fear, defensive strategies and caring for cognitively impaired family members. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:67-85.

17. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Dementia and aggressiveness: stimulated recall interviews with caregivers after video-recorded interactions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:515-525.

18. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:283-296.

19. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) - a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;14:900-910.

20. Janzen S, Zecevic AA, Kloseck M, et al. Managing agitation using nonpharmacological interventions for seniors with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:524-532.

21. Zeller A, Dassen T, Kok G, et al. Nursing home caregivers’ explanations for and coping strategies with residents’ aggression: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2469-2478.

22. Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: homecare. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

23. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Refining caregiver vulnerability for clinical practice: determinants of self-rated health in spousal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:18.

24. Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 15:20-25.

25. Wawrziczny E, Larochette C, Papo D, et al. A customized intervention for dementia caregivers: a quasi-experimental design. J Aging Health. 2019;31:1172-1195.

26. Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, et al. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:92-102.

27. de Oliveira AM, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, et al. An intervention to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia: preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program-outpatient version. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1301-1307.

28. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6276.

29. Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, et al. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:209-216.

30. Moskowitz JT, Cheung EO, Snowberg KE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019;38:391-402.

31. Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37:222-233.

32. Zwingmann I, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Esser A, et al. Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:121.

33. Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T. Caregivers’ perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2713-2726.

34. Nakaishi L, Moss H, Weinstein M, et al. Exploring workplace violence among home care workers in a consumer-driven home health care program. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61:441-450.

35. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1-98.

36. Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, et al. Firearms and dementia: clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:47-49.

37. Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103489.

38. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Screen caregivers and family members of patients with dementia for signs of interpersonal violence. C

› Counsel caregivers early on that behavior changes in patients with dementia are likely and may be unpredictable. C

› Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter routines such as bedtimes and meals. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Siblings of people with bipolar disorder have higher cancer risk

, according to new research from Taiwan.

“To our knowledge, our study is the first to report an increased overall cancer risk as well as increased risks of breast and ectodermal cancer among the unaffected siblings aged < 50 years of patients with bipolar disorder,” Ya-Mei Bai, MD, PhD, of National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan, and colleagues write in an article published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

Most, but not all, previous studies have shown a link between bipolar disorder and cancer. Whether the elevated risk of malignancy extends to family members without the mental health condition has not been elucidated.

To investigate, the researchers turned to the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan. They identified 25,356 individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder by a psychiatrist between 1996 and 2010 and the same number of unaffected siblings, as well as more than 100,000 age-, sex-, income-, and residence-matched controls without severe mental illness.

Compared with the control group, people with bipolar disorder (odds ratio, 1.22) and their unaffected siblings (OR, 1.17) both had a higher risk of developing malignant cancer of any kind. The researchers also found that both groups were at higher risk for breast cancer, with odds ratios of 1.98 in individuals with bipolar disorder and 1.73 in their unaffected siblings.

However, the risk of skin cancer was only high in people with bipolar disorder (OR, 2.70) and not in their siblings (OR, 0.62). And conversely, the risk of kidney cancer was significantly increased in unaffected siblings (OR, 2.45) but not in people with bipolar disorder (OR, 0.47).

When stratified by the embryonic developmental layer from which tumors had originated – ectodermal, mesodermal, or endodermal – the authors observed a significantly increased risk for only ectodermal cancers. In addition, only people under age 50 in both groups (OR, 1.90 for those with bipolar disorder; OR, 1.65 for siblings) were more likely to develop an ectodermal cancer, especially of the breast, compared with the control group. The risks remained elevated after excluding breast cancer but were no longer significant.

When stratified by age, the risk of developing any cancer in both groups also only appeared to be greater for those under age 50 (OR, 1.34 in people with bipolar disorder; OR, 1.32 in siblings) compared with those aged 50 and over (OR, 0.97 and 0.99, respectively). The authors highlighted these figures in the supplemental data set but did not discuss it further in the study beyond a brief mention that “younger patients with bipolar disorder and younger unaffected siblings (< 50 years), but not older ones (≥ 50 years), were more likely to develop any malignancy during the follow-up than matched controls.”

“This paper essentially finds what we have found in our previous work – that people with bipolar disorder have a greater risk of cancer,” said Michael Berk, MBBCh, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at the Deakin University School of Medicine in Geelong, Australia, who published a systematic review and meta-analysis last spring on cancer risk and the role of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder.

“The interesting finding in our work,” Dr. Berk told this news organization, “is that this risk is attenuated by use of lithium but not other agents.”

The Taiwanese researchers propose a “biopsychosocial explanation” for their results, noting that both the nervous system and the breast and skin develop from the ectoderm, and that cancer risk factors such as smoking and obesity are more common in people with bipolar disorder and their unaffected siblings.

“The findings,” they write, “imply a genetic overlap in neurodevelopment and malignancy pathogenesis and may encourage clinicians to closely monitor patients with bipolar disorder and their unaffected siblings for cancer warning signs.”

The authors, however, caution that their study needs validation and had several limitations, including lack of adjustment for drug treatment and lifestyle and environmental factors.

“Our findings may persuade clinicians and researchers to reevaluate the cancer risk among the unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder because these two severe mental disorders may have a common biopsychosocial pathophysiology,” the team writes.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation, and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to new research from Taiwan.

“To our knowledge, our study is the first to report an increased overall cancer risk as well as increased risks of breast and ectodermal cancer among the unaffected siblings aged < 50 years of patients with bipolar disorder,” Ya-Mei Bai, MD, PhD, of National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan, and colleagues write in an article published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

Most, but not all, previous studies have shown a link between bipolar disorder and cancer. Whether the elevated risk of malignancy extends to family members without the mental health condition has not been elucidated.

To investigate, the researchers turned to the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan. They identified 25,356 individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder by a psychiatrist between 1996 and 2010 and the same number of unaffected siblings, as well as more than 100,000 age-, sex-, income-, and residence-matched controls without severe mental illness.

Compared with the control group, people with bipolar disorder (odds ratio, 1.22) and their unaffected siblings (OR, 1.17) both had a higher risk of developing malignant cancer of any kind. The researchers also found that both groups were at higher risk for breast cancer, with odds ratios of 1.98 in individuals with bipolar disorder and 1.73 in their unaffected siblings.

However, the risk of skin cancer was only high in people with bipolar disorder (OR, 2.70) and not in their siblings (OR, 0.62). And conversely, the risk of kidney cancer was significantly increased in unaffected siblings (OR, 2.45) but not in people with bipolar disorder (OR, 0.47).

When stratified by the embryonic developmental layer from which tumors had originated – ectodermal, mesodermal, or endodermal – the authors observed a significantly increased risk for only ectodermal cancers. In addition, only people under age 50 in both groups (OR, 1.90 for those with bipolar disorder; OR, 1.65 for siblings) were more likely to develop an ectodermal cancer, especially of the breast, compared with the control group. The risks remained elevated after excluding breast cancer but were no longer significant.

When stratified by age, the risk of developing any cancer in both groups also only appeared to be greater for those under age 50 (OR, 1.34 in people with bipolar disorder; OR, 1.32 in siblings) compared with those aged 50 and over (OR, 0.97 and 0.99, respectively). The authors highlighted these figures in the supplemental data set but did not discuss it further in the study beyond a brief mention that “younger patients with bipolar disorder and younger unaffected siblings (< 50 years), but not older ones (≥ 50 years), were more likely to develop any malignancy during the follow-up than matched controls.”

“This paper essentially finds what we have found in our previous work – that people with bipolar disorder have a greater risk of cancer,” said Michael Berk, MBBCh, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at the Deakin University School of Medicine in Geelong, Australia, who published a systematic review and meta-analysis last spring on cancer risk and the role of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder.

“The interesting finding in our work,” Dr. Berk told this news organization, “is that this risk is attenuated by use of lithium but not other agents.”

The Taiwanese researchers propose a “biopsychosocial explanation” for their results, noting that both the nervous system and the breast and skin develop from the ectoderm, and that cancer risk factors such as smoking and obesity are more common in people with bipolar disorder and their unaffected siblings.

“The findings,” they write, “imply a genetic overlap in neurodevelopment and malignancy pathogenesis and may encourage clinicians to closely monitor patients with bipolar disorder and their unaffected siblings for cancer warning signs.”

The authors, however, caution that their study needs validation and had several limitations, including lack of adjustment for drug treatment and lifestyle and environmental factors.

“Our findings may persuade clinicians and researchers to reevaluate the cancer risk among the unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder because these two severe mental disorders may have a common biopsychosocial pathophysiology,” the team writes.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation, and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to new research from Taiwan.

“To our knowledge, our study is the first to report an increased overall cancer risk as well as increased risks of breast and ectodermal cancer among the unaffected siblings aged < 50 years of patients with bipolar disorder,” Ya-Mei Bai, MD, PhD, of National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan, and colleagues write in an article published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

Most, but not all, previous studies have shown a link between bipolar disorder and cancer. Whether the elevated risk of malignancy extends to family members without the mental health condition has not been elucidated.

To investigate, the researchers turned to the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan. They identified 25,356 individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder by a psychiatrist between 1996 and 2010 and the same number of unaffected siblings, as well as more than 100,000 age-, sex-, income-, and residence-matched controls without severe mental illness.

Compared with the control group, people with bipolar disorder (odds ratio, 1.22) and their unaffected siblings (OR, 1.17) both had a higher risk of developing malignant cancer of any kind. The researchers also found that both groups were at higher risk for breast cancer, with odds ratios of 1.98 in individuals with bipolar disorder and 1.73 in their unaffected siblings.

However, the risk of skin cancer was only high in people with bipolar disorder (OR, 2.70) and not in their siblings (OR, 0.62). And conversely, the risk of kidney cancer was significantly increased in unaffected siblings (OR, 2.45) but not in people with bipolar disorder (OR, 0.47).

When stratified by the embryonic developmental layer from which tumors had originated – ectodermal, mesodermal, or endodermal – the authors observed a significantly increased risk for only ectodermal cancers. In addition, only people under age 50 in both groups (OR, 1.90 for those with bipolar disorder; OR, 1.65 for siblings) were more likely to develop an ectodermal cancer, especially of the breast, compared with the control group. The risks remained elevated after excluding breast cancer but were no longer significant.

When stratified by age, the risk of developing any cancer in both groups also only appeared to be greater for those under age 50 (OR, 1.34 in people with bipolar disorder; OR, 1.32 in siblings) compared with those aged 50 and over (OR, 0.97 and 0.99, respectively). The authors highlighted these figures in the supplemental data set but did not discuss it further in the study beyond a brief mention that “younger patients with bipolar disorder and younger unaffected siblings (< 50 years), but not older ones (≥ 50 years), were more likely to develop any malignancy during the follow-up than matched controls.”

“This paper essentially finds what we have found in our previous work – that people with bipolar disorder have a greater risk of cancer,” said Michael Berk, MBBCh, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at the Deakin University School of Medicine in Geelong, Australia, who published a systematic review and meta-analysis last spring on cancer risk and the role of lithium treatment in bipolar disorder.

“The interesting finding in our work,” Dr. Berk told this news organization, “is that this risk is attenuated by use of lithium but not other agents.”

The Taiwanese researchers propose a “biopsychosocial explanation” for their results, noting that both the nervous system and the breast and skin develop from the ectoderm, and that cancer risk factors such as smoking and obesity are more common in people with bipolar disorder and their unaffected siblings.

“The findings,” they write, “imply a genetic overlap in neurodevelopment and malignancy pathogenesis and may encourage clinicians to closely monitor patients with bipolar disorder and their unaffected siblings for cancer warning signs.”

The authors, however, caution that their study needs validation and had several limitations, including lack of adjustment for drug treatment and lifestyle and environmental factors.

“Our findings may persuade clinicians and researchers to reevaluate the cancer risk among the unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder because these two severe mental disorders may have a common biopsychosocial pathophysiology,” the team writes.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation, and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CANCER

Novel biomarker found for Alzheimer’s disease

The study covered in this summary was published in medRxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Estimated beta-amyloid (Aβ42) cellular uptake can be more than two times greater in AD patients compared to cognitively normal subjects. A less pronounced yet increased uptake rate was also observed in patients with late-onset mild cognitive impairment (MCI). This increased uptake may prove to be a key mechanism defining age-related AD progression.

- The increased cellular amyloid uptake in AD and LMCI may lead to quicker disease progression, but early-onset MCI may result from increased production of toxic amyloid metabolites.

Why this matters

- Additional biomarkers for AD could greatly aid diagnosis and course prediction, as they are currently limited to PET scan analysis of amyloid plaque deposits and concentration of Aβ42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

- Amyloid deposits found by PET have a positive correlation with AD diagnosis. In contrast, CSF-Aβ42 and AD diagnosis or cognitive decline are negatively correlated. Normal cognition (NC) is associated with higher CSF beta-amyloid levels, but previous research has not explained why CSF-Aβ42 levels can be equivalent in patients with NC but high amyloid load and patients with AD and low amyloid load.

Study design

- The authors of this retrospective study used anonymized data obtained from the Alzheimer’s’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). ADNI’s goal has been to test whether serial MRI scans, PET scans, biomarkers, and clinical/neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and AD.

- Study subjects had either an AD diagnosis or NC and were divided into two groups: low amyloid load and high amyloid load. The fraction of patients with an AD diagnosis was calculated as a function of CSF-Aβ42.

- Calculations and statistical comparisons were performed using Microsoft Excel and custom-written C++ programs.

Key results

- The lowest levels of CSF-Aβ42 correlated with the highest percentage of AD-diagnosed patients, estimated to be 27% in subjects with low amyloid deposit density and 65% in those with high deposit density.

- The relationship between CSF-Aβ42 levels and amyloid load can be described using a simple mathematical model: Amyloid concentration in the interstitial cells is equal to the synthesis rate divided by the density of amyloid deposits plus the sum of the rate of amyloid removal through the CSF and the cellular amyloid uptake rate.

- AD and late-onset MCI patients had a significantly higher amyloid removal rate compared to NC subjects.

- Early-onset MCI patients had Aβ42 turnover similar to that of NC subjects, pointing to a different underlying mechanism such as enzymatic disbalance.

Limitations

- The model used to explain amyloid exchange between the interstitial space and the CSF is oversimplified; the actual process is more complex.

- Synthesis and uptake rates of Aβ42 vary throughout areas of the brain. The model assumes a homogeneous distribution within the interstitial compartment.

Study disclosures

- Research reported in this publication was not supported by any external funding. Data collection and sharing for this project were funded by ADNI.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study covered in this summary was published in medRxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Estimated beta-amyloid (Aβ42) cellular uptake can be more than two times greater in AD patients compared to cognitively normal subjects. A less pronounced yet increased uptake rate was also observed in patients with late-onset mild cognitive impairment (MCI). This increased uptake may prove to be a key mechanism defining age-related AD progression.

- The increased cellular amyloid uptake in AD and LMCI may lead to quicker disease progression, but early-onset MCI may result from increased production of toxic amyloid metabolites.