User login

Prophylactic antibiotics for myomectomy?

In the 1990s, researchers found that patients undergoing any type of surgical procedure were more than twice as likely to die if they developed postsurgical infection.1 Work to reduce surgical site infection (SSI) has and does continue, with perioperative antibiotics representing a good part of that effort. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends such antibiotic therapy for women undergoing laparotomy and laparoscopic hysterectomy.2 ACOG does not, however, recommend prophylactic antibiotics for myomectomy procedures.3 Rates of infection for hysterectomy have been reported to be 3.9% for abdominal and 1.4% for minimally invasive approaches.4

To determine the current use of antibiotics during myomectomy and associated rates of SSI at their institutions, Dipti Banerjee, MD, and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of women undergoing laparoscopic or abdominal myomectomy between February 2013 and December 2017 at the University of California, Los Angeles and Hoag Memorial Hospital in Orange County, California. They presented their study results at AAGL’s 49th Global Congress on MIGS, held virtually November 6-14, 2020.3

Rate of SSI after myomectomy

A total of 620 women underwent laparoscopic myomectomy and 563 underwent open myomectomy during the study period. Antibiotics were used in 76.9% of cases. SSI developed within 6 weeks of surgery in 34 women (2.9%) overall. The women undergoing abdominal myomectomy without antibiotics were more likely to experience SSI than the women who received antibiotics (odds ratio [OR], 4.89; confidence interval [CI], 1.80–13.27; P = .0006). For laparoscopic myomectomy, antibiotic use did not affect the odds of developing SSI (OR, 1.08; CI, 0.35–3.35).

Antibiotics were more likely to be used in certain cases

Antibiotics were more likely to be administered for patients who:

- were obese (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2) (P = .009)

- underwent previous abdominal surgery (P = .001)

- underwent laparotomy (P <.0001)

- had endometrial cavity entry (P <.0001)

- had >1 fibroid (P = .0004) or an aggregate fibroid weight >500 g (P <.0001).

More data on antibiotics for myomectomy

In a retrospective study conducted at 2 academic hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts, 1,211 women underwent myomectomy from 2009 to 2016. (Exclusions were use of vaginal or hysteroscopic myomectomy, chromopertubation, or conversion to hysterectomy.) More than 92% of the women received perioperative antibiotics at the time of surgery. Although demographics were similar between women receiving and not receiving antibiotics, women who received antibiotics were more likely to have longer operative times (median 140 vs 85 min), a greater myoma burden (7 vs 2 myomas removed and weight 255 vs 53 g), and lose blood during the procedure (137 vs 50 mL). These women also were 4 times less likely to have surgical site infection (adjusted OR, 3.77; 95% CI, 1.30–10.97; P = .015).5,6

Banerjee and colleagues say that their California study demonstrates “that the majority of surgeons elect to use antibiotics prophylactically” during myomectomy, despite current ACOG guidelines, and that their findings of benefit for abdominal myomectomy but not for laparoscopic myomectomy should inform future guidance on antibiotics for myomectomy surgery.3

- Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, et al. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725-730.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 195: prevention of infection after gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e172-e189.

- Banerjee D, Dejbakhsh S, Patel HH, et al. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in myomectomy surgery. Paper presented at 49th Annual Meeting of the AAGL; November 2020.

- Uppal S, Harris J, Al-Niaimi A. Prophylactic antibiotic choice and risk of surgical site infection after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:321-329.

- Kim AJ, Clark NV, Jansen LJ, et al. Perioperative antibiotic use and associated infectious outcomes at the time of myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:626-635.

- Rebar RW. Should perioperative antibiotics at myomectomy be universal? NEJM J Watch. March 11, 2019.

In the 1990s, researchers found that patients undergoing any type of surgical procedure were more than twice as likely to die if they developed postsurgical infection.1 Work to reduce surgical site infection (SSI) has and does continue, with perioperative antibiotics representing a good part of that effort. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends such antibiotic therapy for women undergoing laparotomy and laparoscopic hysterectomy.2 ACOG does not, however, recommend prophylactic antibiotics for myomectomy procedures.3 Rates of infection for hysterectomy have been reported to be 3.9% for abdominal and 1.4% for minimally invasive approaches.4

To determine the current use of antibiotics during myomectomy and associated rates of SSI at their institutions, Dipti Banerjee, MD, and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of women undergoing laparoscopic or abdominal myomectomy between February 2013 and December 2017 at the University of California, Los Angeles and Hoag Memorial Hospital in Orange County, California. They presented their study results at AAGL’s 49th Global Congress on MIGS, held virtually November 6-14, 2020.3

Rate of SSI after myomectomy

A total of 620 women underwent laparoscopic myomectomy and 563 underwent open myomectomy during the study period. Antibiotics were used in 76.9% of cases. SSI developed within 6 weeks of surgery in 34 women (2.9%) overall. The women undergoing abdominal myomectomy without antibiotics were more likely to experience SSI than the women who received antibiotics (odds ratio [OR], 4.89; confidence interval [CI], 1.80–13.27; P = .0006). For laparoscopic myomectomy, antibiotic use did not affect the odds of developing SSI (OR, 1.08; CI, 0.35–3.35).

Antibiotics were more likely to be used in certain cases

Antibiotics were more likely to be administered for patients who:

- were obese (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2) (P = .009)

- underwent previous abdominal surgery (P = .001)

- underwent laparotomy (P <.0001)

- had endometrial cavity entry (P <.0001)

- had >1 fibroid (P = .0004) or an aggregate fibroid weight >500 g (P <.0001).

More data on antibiotics for myomectomy

In a retrospective study conducted at 2 academic hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts, 1,211 women underwent myomectomy from 2009 to 2016. (Exclusions were use of vaginal or hysteroscopic myomectomy, chromopertubation, or conversion to hysterectomy.) More than 92% of the women received perioperative antibiotics at the time of surgery. Although demographics were similar between women receiving and not receiving antibiotics, women who received antibiotics were more likely to have longer operative times (median 140 vs 85 min), a greater myoma burden (7 vs 2 myomas removed and weight 255 vs 53 g), and lose blood during the procedure (137 vs 50 mL). These women also were 4 times less likely to have surgical site infection (adjusted OR, 3.77; 95% CI, 1.30–10.97; P = .015).5,6

Banerjee and colleagues say that their California study demonstrates “that the majority of surgeons elect to use antibiotics prophylactically” during myomectomy, despite current ACOG guidelines, and that their findings of benefit for abdominal myomectomy but not for laparoscopic myomectomy should inform future guidance on antibiotics for myomectomy surgery.3

In the 1990s, researchers found that patients undergoing any type of surgical procedure were more than twice as likely to die if they developed postsurgical infection.1 Work to reduce surgical site infection (SSI) has and does continue, with perioperative antibiotics representing a good part of that effort. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends such antibiotic therapy for women undergoing laparotomy and laparoscopic hysterectomy.2 ACOG does not, however, recommend prophylactic antibiotics for myomectomy procedures.3 Rates of infection for hysterectomy have been reported to be 3.9% for abdominal and 1.4% for minimally invasive approaches.4

To determine the current use of antibiotics during myomectomy and associated rates of SSI at their institutions, Dipti Banerjee, MD, and colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of women undergoing laparoscopic or abdominal myomectomy between February 2013 and December 2017 at the University of California, Los Angeles and Hoag Memorial Hospital in Orange County, California. They presented their study results at AAGL’s 49th Global Congress on MIGS, held virtually November 6-14, 2020.3

Rate of SSI after myomectomy

A total of 620 women underwent laparoscopic myomectomy and 563 underwent open myomectomy during the study period. Antibiotics were used in 76.9% of cases. SSI developed within 6 weeks of surgery in 34 women (2.9%) overall. The women undergoing abdominal myomectomy without antibiotics were more likely to experience SSI than the women who received antibiotics (odds ratio [OR], 4.89; confidence interval [CI], 1.80–13.27; P = .0006). For laparoscopic myomectomy, antibiotic use did not affect the odds of developing SSI (OR, 1.08; CI, 0.35–3.35).

Antibiotics were more likely to be used in certain cases

Antibiotics were more likely to be administered for patients who:

- were obese (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2) (P = .009)

- underwent previous abdominal surgery (P = .001)

- underwent laparotomy (P <.0001)

- had endometrial cavity entry (P <.0001)

- had >1 fibroid (P = .0004) or an aggregate fibroid weight >500 g (P <.0001).

More data on antibiotics for myomectomy

In a retrospective study conducted at 2 academic hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts, 1,211 women underwent myomectomy from 2009 to 2016. (Exclusions were use of vaginal or hysteroscopic myomectomy, chromopertubation, or conversion to hysterectomy.) More than 92% of the women received perioperative antibiotics at the time of surgery. Although demographics were similar between women receiving and not receiving antibiotics, women who received antibiotics were more likely to have longer operative times (median 140 vs 85 min), a greater myoma burden (7 vs 2 myomas removed and weight 255 vs 53 g), and lose blood during the procedure (137 vs 50 mL). These women also were 4 times less likely to have surgical site infection (adjusted OR, 3.77; 95% CI, 1.30–10.97; P = .015).5,6

Banerjee and colleagues say that their California study demonstrates “that the majority of surgeons elect to use antibiotics prophylactically” during myomectomy, despite current ACOG guidelines, and that their findings of benefit for abdominal myomectomy but not for laparoscopic myomectomy should inform future guidance on antibiotics for myomectomy surgery.3

- Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, et al. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725-730.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 195: prevention of infection after gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e172-e189.

- Banerjee D, Dejbakhsh S, Patel HH, et al. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in myomectomy surgery. Paper presented at 49th Annual Meeting of the AAGL; November 2020.

- Uppal S, Harris J, Al-Niaimi A. Prophylactic antibiotic choice and risk of surgical site infection after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:321-329.

- Kim AJ, Clark NV, Jansen LJ, et al. Perioperative antibiotic use and associated infectious outcomes at the time of myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:626-635.

- Rebar RW. Should perioperative antibiotics at myomectomy be universal? NEJM J Watch. March 11, 2019.

- Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, et al. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725-730.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 195: prevention of infection after gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e172-e189.

- Banerjee D, Dejbakhsh S, Patel HH, et al. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in myomectomy surgery. Paper presented at 49th Annual Meeting of the AAGL; November 2020.

- Uppal S, Harris J, Al-Niaimi A. Prophylactic antibiotic choice and risk of surgical site infection after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:321-329.

- Kim AJ, Clark NV, Jansen LJ, et al. Perioperative antibiotic use and associated infectious outcomes at the time of myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:626-635.

- Rebar RW. Should perioperative antibiotics at myomectomy be universal? NEJM J Watch. March 11, 2019.

Hysteroscopy and COVID-19: Have recommended techniques changed due to the pandemic?

The emergence of the coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) in December 2019, has resulted in a global pandemic that has challenged the medical community and will continue to represent a public health emergency for the next several months.1 It has rapidly spread globally, infecting many individuals in an unprecedented rate of infection and worldwide reach. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID-19 as a pandemic. While the majority of infected individuals are asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, some have an unfortunate clinical course resulting in multi-organ failure and death.2

It is accepted that the virus mainly spreads during close contact and via respiratory droplets.3 The average time from infection to onset of symptoms ranges from 2 to 14 days, with an average of 5 days.4 Recommended measures to prevent the spread of the infection include social distancing (at least 6 feet from others), meticulous hand hygiene, and wearing a mask covering the mouth and nose when in public.5 Aiming to mitigate the risk of viral dissemination for patients and health care providers, and to preserve hospital resources, all nonessential medical interventions were initially suspended. Recently, the American College of Surgeons in a joint statement with 9 women’s health care societies have provided recommendations on how to resume clinical activities as we recover from the pandemic.6

As we reinitiate clinical activities, gynecologists have been alerted of the potential risk of viral dissemination during gynecologic minimally invasive surgical procedures due to the presence of the virus in blood, stool, and the potential risk of aerosolization of the virus, especially when using smoke-generating devices.7,8 This risk is not limited to intubation and extubation of the airway during anesthesia; the risk also presents itself during other aerosol-generating procedures, such as laparoscopy or robotic surgery.9,10

Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard procedure for the diagnosis and management of intrauterine pathologies.11 It is frequently performed in an office setting without the use of anesthesia.11,12 It is usually well tolerated, with only a few patients reporting discomfort.12 It allows for immediate treatment (using the “see and treat” approach) while avoiding not only the risk of anesthesia, as stated, but also the need for intubation—which has a high risk of droplet contamination in COVID-19–infected individuals.13

Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures?

The novel and rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic present many challenges to the gynecologist. Significant concerns have been raised regarding potential risk of viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery due to aerosolization of viral particles and the presence of the virus in blood and the gastrointestinal tract of infected patients.7 Diagnostic, and some simple, hysteroscopic procedures are commonly performed in an outpatient setting, with the patient awake. Complex hysteroscopic interventions, however, are generally performed in the operating room, typically with the use of general anesthesia. Hysteroscopy has the theoretical risks of viral dissemination when performed in COVID-19–positive patients. Two important questions must be addressed to better understand the potential risk of COVID-19 viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures.

Continue to: 1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?...

1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of viral particles in urine, feces, blood, and tears in addition to the respiratory tract in patients infected with COVID-19.3,14,15 The presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the female genital system is currently unknown. Previous studies, of other epidemic viral infections, have demonstrated the presence of the virus in the female genital tract in affected patients of Zika virus and Ebola.16,17 However, 2 recent studies have failed to demonstrate the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the vaginal fluid of pregnant14 and not pregnant18 women with severe COVID-19 infection.

2. Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopy if using electrosurgery?

There are significant concerns with possible risk of COVID-19 transmission to health care providers in direct contact with infected patients during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures due to direct contamination and aerosolization of the virus.10,19 Current data on COVID-19 transmission during surgery are limited. However, it is important to recognize that viral aerosolization has been documented with other viral diseases, such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B.20 A recent report called for awareness in the surgical community about the potential risks of COVID-19 viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery. Among other recommendations, international experts advised minimizing the use of electrosurgery to reduce the creation of surgical plume, decreasing the pneumoperitoneum pressure to minimum levels, and using suction devices in a closed system.21 Although these preventive measures apply to laparoscopic surgery, it is important to consider that hysteroscopy is performed in a unique environment.

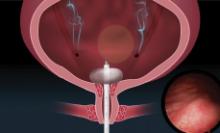

During hysteroscopy the uterine cavity is distended with a liquid medium (normal saline or electrolyte-free solutions); this is opposed to gynecologic laparoscopy, in which the peritoneal cavity is distended with carbon dioxide.22 The smoke produced with the use of hysteroscopic electrosurgical instruments generates bubbles that are immediately cooled down to the temperature of the distention media and subsequently dissolve into it. Therefore, there are no bubbles generated during hysteroscopic surgery that are subsequently released into the air. This results in a low risk for viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures. Nevertheless, the necessary precautions to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission during hysteroscopic intervention are extremely important.

Recommendations for hysteroscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic

We provide our overall recommendations for hysteroscopy, as well as those specific to the office and hospital setting.

Recommendations: General

Limit hysteroscopic procedures to COVID-19–negative patients and to those patients in whom delaying the procedure could result in adverse clinical outcomes.23

Universally screen for potential COVID-19 infection. When possible, a phone interview to triage patients based on their symptoms and infection exposure status should take place before the patient arrives to the health care center. Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection who require immediate evaluation should be directed to COVID-19–designated emergency areas.

Universally test for SARS-CoV-2 before procedures performed in the operating room (OR). Using nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of viral RNA, employing molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), within 48 to 72 hours prior to all OR hysteroscopic procedures is strongly recommended. Adopting this testing strategy will aid to identify asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2‒infected patients, allowing to defer the procedure, if possible, among patients testing positive. If tests are limited, testing only patients scheduled for hysteroscopic procedures in which general or regional anesthesia will be required is acceptable.

Universal SARS-CoV-2 testing of patients undergoing in-office hysteroscopic diagnostic or minor operative procedures without the use of anesthesia is not required.

Limit the presence of a companion. It is understood that visitor policies may vary at the discretion of each institution’s guidelines. Children and individuals over the age of 60 years should not be granted access to the center. Companions will be subjected to the same screening criteria as patients.

Provide for social distancing and other precautionary measures. If more than one patient is scheduled to be at the facility at the same time, ensure that the facility provides adequate space to allow the appropriate social distancing recommendations between patients. Hand sanitizers and facemasks should be available for patients and companions.

Provide PPE for clinicians. All health care providers in close contact with the patient must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes an apron and gown, a surgical mask, eye protection, and gloves. Health care providers should wear PPE deemed appropriate by their regulatory institutions following their local and national guidelines during clinical patient interactions.

Restrict surgical attendees to vital personnel. The participation of learners by physical presence in the office or operating room should be restricted.

Continue to: Recommendations: Office setting...

Recommendations: Office setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Advise patients to come to the office alone. If the patient requires a companion, a maximum of one adult companion under the age of 60 should be accepted.

- Limit the number of health care team members present in the procedure room.

Intraprocedural recommendations

- Choose the appropriate device(s) that will allow for an effective and fast procedure.

- Use the recommended PPE for all clinicians.

- Limit the movement of staff members in and out of the procedure room.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same procedure room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Allow for patients to recover from the procedure in the same room as the procedure took place in order to avoid potential contamination of multiple rooms.

- Expedite patient discharge.

- Follow up after the procedure by phone or telemedicine.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Continue to: Recommendations: Operating room setting...

Recommendations: Operating room setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Perform adequate patient screening for potential COVID-19 infection. (Screening should be independent of symptoms and not be limited to those with clinical symptoms.)

- Limit the number of health care team members in the operating procedure room.

- To minimize unnecessary staff exposure, have surgeons and staff not needed for intubation remain outside the OR until intubation is completed and leave the OR before extubation.

Intraprocedure recommendations

- Limit personnel in the OR to a minimum.

- Staff should not enter or leave the room during the procedure.

- When possible, use conscious sedation or regional anesthesia to avoid the risk of viral dissemination at the time of intubation/extubation.

- Choose the device that will allow an effective and fast procedure.

- Favor non–smoke-generating devices, such as hysteroscopic scissors, graspers, and tissue retrieval systems.

- Connect active suction to the outflow, especially when using smoke-generating instruments, to facilitate the extraction of surgical smoke.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Expedite postprocedure recovery and patient discharge.

- After completion of the procedure, staff should remove scrubs and change into clean clothing.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global health emergency. Our knowledge of this devastating virus is constantly evolving as we continue to fight this overwhelming disease. Theoretical risk of “viral” dissemination is considered extremely low, or negligible, during hysterosocopy. Hysteroscopic procedures in COVID-19–positive patients with life-threatening conditions or in patients in whom delaying the procedure could worsen outcomes should be performed taking appropriate measures. Patients who test negative for COVID-19 (confirmed by PCR) and require hysteroscopic procedures, should be treated using universal precautions. ●

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25:e936-e945.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843-1844.

- Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:793-798.

- Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al; Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e261-e270.

- American College of Surgeons, American Society of Aesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, American Hospital Association. Joint Statement: Roadmap for resuming elective surgery after COVID-19 pandemic. April 16, 2020. https://www.aorn.org/guidelines/aorn-support/roadmap-for-resuming-elective-surgery-after-covid-19. Accessed August 27, 2020.

- Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386-389.

- Mowbray NG, Ansell J, Horwood J, et al. Safe management of surgical smoke in the age of COVID-19. Br J Surg. May 3, 2020. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11679.

- Cohen SL, Liu G, Abrao M, et al. Perspectives on surgery in the time of COVID-19: safety first. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:792-793.

- COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:703-708.

- Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568-576.

- Aslan MM, Yuvaci HU, Köse O, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not present in the vaginal fluid of pregnant women with COVID-19. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1-3. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1793318.

- Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:833-840.

- Prisant N, Bujan L, Benichou H, et al. Zika virus in the female genital tract. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1000-1001.

- Rodriguez LL, De Roo A, Guimard Y, et al. Persistence and genetic stability of Ebola virus during the outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999;179 Suppl 1:S170-S176.

- Qiu L, Liu X, Xiao M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not detectable in the vaginal fluid of women with severe COVID-19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:813-817.

- Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, et al. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID-19 outbreak: a narrative review and clinical considerations. Ann Surg. April 17, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926.

- Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:857-863.

- Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e5-e6.

- Catena U. Surgical smoke in hysteroscopic surgery: does it really matter in COVID-19 times? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2020;12:67-68.

- Carugno J, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Alonso L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic. Impact on hysteroscopic procedures: a consensus statement from the Global Congress of Hysteroscopy Scientific Committee. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:988-992.

The emergence of the coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) in December 2019, has resulted in a global pandemic that has challenged the medical community and will continue to represent a public health emergency for the next several months.1 It has rapidly spread globally, infecting many individuals in an unprecedented rate of infection and worldwide reach. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID-19 as a pandemic. While the majority of infected individuals are asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, some have an unfortunate clinical course resulting in multi-organ failure and death.2

It is accepted that the virus mainly spreads during close contact and via respiratory droplets.3 The average time from infection to onset of symptoms ranges from 2 to 14 days, with an average of 5 days.4 Recommended measures to prevent the spread of the infection include social distancing (at least 6 feet from others), meticulous hand hygiene, and wearing a mask covering the mouth and nose when in public.5 Aiming to mitigate the risk of viral dissemination for patients and health care providers, and to preserve hospital resources, all nonessential medical interventions were initially suspended. Recently, the American College of Surgeons in a joint statement with 9 women’s health care societies have provided recommendations on how to resume clinical activities as we recover from the pandemic.6

As we reinitiate clinical activities, gynecologists have been alerted of the potential risk of viral dissemination during gynecologic minimally invasive surgical procedures due to the presence of the virus in blood, stool, and the potential risk of aerosolization of the virus, especially when using smoke-generating devices.7,8 This risk is not limited to intubation and extubation of the airway during anesthesia; the risk also presents itself during other aerosol-generating procedures, such as laparoscopy or robotic surgery.9,10

Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard procedure for the diagnosis and management of intrauterine pathologies.11 It is frequently performed in an office setting without the use of anesthesia.11,12 It is usually well tolerated, with only a few patients reporting discomfort.12 It allows for immediate treatment (using the “see and treat” approach) while avoiding not only the risk of anesthesia, as stated, but also the need for intubation—which has a high risk of droplet contamination in COVID-19–infected individuals.13

Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures?

The novel and rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic present many challenges to the gynecologist. Significant concerns have been raised regarding potential risk of viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery due to aerosolization of viral particles and the presence of the virus in blood and the gastrointestinal tract of infected patients.7 Diagnostic, and some simple, hysteroscopic procedures are commonly performed in an outpatient setting, with the patient awake. Complex hysteroscopic interventions, however, are generally performed in the operating room, typically with the use of general anesthesia. Hysteroscopy has the theoretical risks of viral dissemination when performed in COVID-19–positive patients. Two important questions must be addressed to better understand the potential risk of COVID-19 viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures.

Continue to: 1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?...

1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of viral particles in urine, feces, blood, and tears in addition to the respiratory tract in patients infected with COVID-19.3,14,15 The presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the female genital system is currently unknown. Previous studies, of other epidemic viral infections, have demonstrated the presence of the virus in the female genital tract in affected patients of Zika virus and Ebola.16,17 However, 2 recent studies have failed to demonstrate the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the vaginal fluid of pregnant14 and not pregnant18 women with severe COVID-19 infection.

2. Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopy if using electrosurgery?

There are significant concerns with possible risk of COVID-19 transmission to health care providers in direct contact with infected patients during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures due to direct contamination and aerosolization of the virus.10,19 Current data on COVID-19 transmission during surgery are limited. However, it is important to recognize that viral aerosolization has been documented with other viral diseases, such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B.20 A recent report called for awareness in the surgical community about the potential risks of COVID-19 viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery. Among other recommendations, international experts advised minimizing the use of electrosurgery to reduce the creation of surgical plume, decreasing the pneumoperitoneum pressure to minimum levels, and using suction devices in a closed system.21 Although these preventive measures apply to laparoscopic surgery, it is important to consider that hysteroscopy is performed in a unique environment.

During hysteroscopy the uterine cavity is distended with a liquid medium (normal saline or electrolyte-free solutions); this is opposed to gynecologic laparoscopy, in which the peritoneal cavity is distended with carbon dioxide.22 The smoke produced with the use of hysteroscopic electrosurgical instruments generates bubbles that are immediately cooled down to the temperature of the distention media and subsequently dissolve into it. Therefore, there are no bubbles generated during hysteroscopic surgery that are subsequently released into the air. This results in a low risk for viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures. Nevertheless, the necessary precautions to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission during hysteroscopic intervention are extremely important.

Recommendations for hysteroscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic

We provide our overall recommendations for hysteroscopy, as well as those specific to the office and hospital setting.

Recommendations: General

Limit hysteroscopic procedures to COVID-19–negative patients and to those patients in whom delaying the procedure could result in adverse clinical outcomes.23

Universally screen for potential COVID-19 infection. When possible, a phone interview to triage patients based on their symptoms and infection exposure status should take place before the patient arrives to the health care center. Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection who require immediate evaluation should be directed to COVID-19–designated emergency areas.

Universally test for SARS-CoV-2 before procedures performed in the operating room (OR). Using nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of viral RNA, employing molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), within 48 to 72 hours prior to all OR hysteroscopic procedures is strongly recommended. Adopting this testing strategy will aid to identify asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2‒infected patients, allowing to defer the procedure, if possible, among patients testing positive. If tests are limited, testing only patients scheduled for hysteroscopic procedures in which general or regional anesthesia will be required is acceptable.

Universal SARS-CoV-2 testing of patients undergoing in-office hysteroscopic diagnostic or minor operative procedures without the use of anesthesia is not required.

Limit the presence of a companion. It is understood that visitor policies may vary at the discretion of each institution’s guidelines. Children and individuals over the age of 60 years should not be granted access to the center. Companions will be subjected to the same screening criteria as patients.

Provide for social distancing and other precautionary measures. If more than one patient is scheduled to be at the facility at the same time, ensure that the facility provides adequate space to allow the appropriate social distancing recommendations between patients. Hand sanitizers and facemasks should be available for patients and companions.

Provide PPE for clinicians. All health care providers in close contact with the patient must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes an apron and gown, a surgical mask, eye protection, and gloves. Health care providers should wear PPE deemed appropriate by their regulatory institutions following their local and national guidelines during clinical patient interactions.

Restrict surgical attendees to vital personnel. The participation of learners by physical presence in the office or operating room should be restricted.

Continue to: Recommendations: Office setting...

Recommendations: Office setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Advise patients to come to the office alone. If the patient requires a companion, a maximum of one adult companion under the age of 60 should be accepted.

- Limit the number of health care team members present in the procedure room.

Intraprocedural recommendations

- Choose the appropriate device(s) that will allow for an effective and fast procedure.

- Use the recommended PPE for all clinicians.

- Limit the movement of staff members in and out of the procedure room.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same procedure room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Allow for patients to recover from the procedure in the same room as the procedure took place in order to avoid potential contamination of multiple rooms.

- Expedite patient discharge.

- Follow up after the procedure by phone or telemedicine.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Continue to: Recommendations: Operating room setting...

Recommendations: Operating room setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Perform adequate patient screening for potential COVID-19 infection. (Screening should be independent of symptoms and not be limited to those with clinical symptoms.)

- Limit the number of health care team members in the operating procedure room.

- To minimize unnecessary staff exposure, have surgeons and staff not needed for intubation remain outside the OR until intubation is completed and leave the OR before extubation.

Intraprocedure recommendations

- Limit personnel in the OR to a minimum.

- Staff should not enter or leave the room during the procedure.

- When possible, use conscious sedation or regional anesthesia to avoid the risk of viral dissemination at the time of intubation/extubation.

- Choose the device that will allow an effective and fast procedure.

- Favor non–smoke-generating devices, such as hysteroscopic scissors, graspers, and tissue retrieval systems.

- Connect active suction to the outflow, especially when using smoke-generating instruments, to facilitate the extraction of surgical smoke.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Expedite postprocedure recovery and patient discharge.

- After completion of the procedure, staff should remove scrubs and change into clean clothing.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global health emergency. Our knowledge of this devastating virus is constantly evolving as we continue to fight this overwhelming disease. Theoretical risk of “viral” dissemination is considered extremely low, or negligible, during hysterosocopy. Hysteroscopic procedures in COVID-19–positive patients with life-threatening conditions or in patients in whom delaying the procedure could worsen outcomes should be performed taking appropriate measures. Patients who test negative for COVID-19 (confirmed by PCR) and require hysteroscopic procedures, should be treated using universal precautions. ●

The emergence of the coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) in December 2019, has resulted in a global pandemic that has challenged the medical community and will continue to represent a public health emergency for the next several months.1 It has rapidly spread globally, infecting many individuals in an unprecedented rate of infection and worldwide reach. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID-19 as a pandemic. While the majority of infected individuals are asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, some have an unfortunate clinical course resulting in multi-organ failure and death.2

It is accepted that the virus mainly spreads during close contact and via respiratory droplets.3 The average time from infection to onset of symptoms ranges from 2 to 14 days, with an average of 5 days.4 Recommended measures to prevent the spread of the infection include social distancing (at least 6 feet from others), meticulous hand hygiene, and wearing a mask covering the mouth and nose when in public.5 Aiming to mitigate the risk of viral dissemination for patients and health care providers, and to preserve hospital resources, all nonessential medical interventions were initially suspended. Recently, the American College of Surgeons in a joint statement with 9 women’s health care societies have provided recommendations on how to resume clinical activities as we recover from the pandemic.6

As we reinitiate clinical activities, gynecologists have been alerted of the potential risk of viral dissemination during gynecologic minimally invasive surgical procedures due to the presence of the virus in blood, stool, and the potential risk of aerosolization of the virus, especially when using smoke-generating devices.7,8 This risk is not limited to intubation and extubation of the airway during anesthesia; the risk also presents itself during other aerosol-generating procedures, such as laparoscopy or robotic surgery.9,10

Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard procedure for the diagnosis and management of intrauterine pathologies.11 It is frequently performed in an office setting without the use of anesthesia.11,12 It is usually well tolerated, with only a few patients reporting discomfort.12 It allows for immediate treatment (using the “see and treat” approach) while avoiding not only the risk of anesthesia, as stated, but also the need for intubation—which has a high risk of droplet contamination in COVID-19–infected individuals.13

Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures?

The novel and rapidly changing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic present many challenges to the gynecologist. Significant concerns have been raised regarding potential risk of viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery due to aerosolization of viral particles and the presence of the virus in blood and the gastrointestinal tract of infected patients.7 Diagnostic, and some simple, hysteroscopic procedures are commonly performed in an outpatient setting, with the patient awake. Complex hysteroscopic interventions, however, are generally performed in the operating room, typically with the use of general anesthesia. Hysteroscopy has the theoretical risks of viral dissemination when performed in COVID-19–positive patients. Two important questions must be addressed to better understand the potential risk of COVID-19 viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures.

Continue to: 1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?...

1. Is the virus present in the vaginal fluid of women infected with COVID-19?

Recent studies have confirmed the presence of viral particles in urine, feces, blood, and tears in addition to the respiratory tract in patients infected with COVID-19.3,14,15 The presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the female genital system is currently unknown. Previous studies, of other epidemic viral infections, have demonstrated the presence of the virus in the female genital tract in affected patients of Zika virus and Ebola.16,17 However, 2 recent studies have failed to demonstrate the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the vaginal fluid of pregnant14 and not pregnant18 women with severe COVID-19 infection.

2. Is there risk of viral dissemination during hysteroscopy if using electrosurgery?

There are significant concerns with possible risk of COVID-19 transmission to health care providers in direct contact with infected patients during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures due to direct contamination and aerosolization of the virus.10,19 Current data on COVID-19 transmission during surgery are limited. However, it is important to recognize that viral aerosolization has been documented with other viral diseases, such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B.20 A recent report called for awareness in the surgical community about the potential risks of COVID-19 viral dissemination during laparoscopic surgery. Among other recommendations, international experts advised minimizing the use of electrosurgery to reduce the creation of surgical plume, decreasing the pneumoperitoneum pressure to minimum levels, and using suction devices in a closed system.21 Although these preventive measures apply to laparoscopic surgery, it is important to consider that hysteroscopy is performed in a unique environment.

During hysteroscopy the uterine cavity is distended with a liquid medium (normal saline or electrolyte-free solutions); this is opposed to gynecologic laparoscopy, in which the peritoneal cavity is distended with carbon dioxide.22 The smoke produced with the use of hysteroscopic electrosurgical instruments generates bubbles that are immediately cooled down to the temperature of the distention media and subsequently dissolve into it. Therefore, there are no bubbles generated during hysteroscopic surgery that are subsequently released into the air. This results in a low risk for viral dissemination during hysteroscopic procedures. Nevertheless, the necessary precautions to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission during hysteroscopic intervention are extremely important.

Recommendations for hysteroscopic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic

We provide our overall recommendations for hysteroscopy, as well as those specific to the office and hospital setting.

Recommendations: General

Limit hysteroscopic procedures to COVID-19–negative patients and to those patients in whom delaying the procedure could result in adverse clinical outcomes.23

Universally screen for potential COVID-19 infection. When possible, a phone interview to triage patients based on their symptoms and infection exposure status should take place before the patient arrives to the health care center. Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection who require immediate evaluation should be directed to COVID-19–designated emergency areas.

Universally test for SARS-CoV-2 before procedures performed in the operating room (OR). Using nasopharyngeal swabs for the detection of viral RNA, employing molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), within 48 to 72 hours prior to all OR hysteroscopic procedures is strongly recommended. Adopting this testing strategy will aid to identify asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2‒infected patients, allowing to defer the procedure, if possible, among patients testing positive. If tests are limited, testing only patients scheduled for hysteroscopic procedures in which general or regional anesthesia will be required is acceptable.

Universal SARS-CoV-2 testing of patients undergoing in-office hysteroscopic diagnostic or minor operative procedures without the use of anesthesia is not required.

Limit the presence of a companion. It is understood that visitor policies may vary at the discretion of each institution’s guidelines. Children and individuals over the age of 60 years should not be granted access to the center. Companions will be subjected to the same screening criteria as patients.

Provide for social distancing and other precautionary measures. If more than one patient is scheduled to be at the facility at the same time, ensure that the facility provides adequate space to allow the appropriate social distancing recommendations between patients. Hand sanitizers and facemasks should be available for patients and companions.

Provide PPE for clinicians. All health care providers in close contact with the patient must wear personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes an apron and gown, a surgical mask, eye protection, and gloves. Health care providers should wear PPE deemed appropriate by their regulatory institutions following their local and national guidelines during clinical patient interactions.

Restrict surgical attendees to vital personnel. The participation of learners by physical presence in the office or operating room should be restricted.

Continue to: Recommendations: Office setting...

Recommendations: Office setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Advise patients to come to the office alone. If the patient requires a companion, a maximum of one adult companion under the age of 60 should be accepted.

- Limit the number of health care team members present in the procedure room.

Intraprocedural recommendations

- Choose the appropriate device(s) that will allow for an effective and fast procedure.

- Use the recommended PPE for all clinicians.

- Limit the movement of staff members in and out of the procedure room.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same procedure room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Allow for patients to recover from the procedure in the same room as the procedure took place in order to avoid potential contamination of multiple rooms.

- Expedite patient discharge.

- Follow up after the procedure by phone or telemedicine.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Continue to: Recommendations: Operating room setting...

Recommendations: Operating room setting

Preprocedural recommendations

- Perform adequate patient screening for potential COVID-19 infection. (Screening should be independent of symptoms and not be limited to those with clinical symptoms.)

- Limit the number of health care team members in the operating procedure room.

- To minimize unnecessary staff exposure, have surgeons and staff not needed for intubation remain outside the OR until intubation is completed and leave the OR before extubation.

Intraprocedure recommendations

- Limit personnel in the OR to a minimum.

- Staff should not enter or leave the room during the procedure.

- When possible, use conscious sedation or regional anesthesia to avoid the risk of viral dissemination at the time of intubation/extubation.

- Choose the device that will allow an effective and fast procedure.

- Favor non–smoke-generating devices, such as hysteroscopic scissors, graspers, and tissue retrieval systems.

- Connect active suction to the outflow, especially when using smoke-generating instruments, to facilitate the extraction of surgical smoke.

Postprocedure recommendations

- When more than one case is scheduled to be performed in the same room, allow enough time in between cases to grant a thorough OR decontamination.

- Expedite postprocedure recovery and patient discharge.

- After completion of the procedure, staff should remove scrubs and change into clean clothing.

- Use standard endoscope disinfection procedures, as they are effective and should not be modified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a global health emergency. Our knowledge of this devastating virus is constantly evolving as we continue to fight this overwhelming disease. Theoretical risk of “viral” dissemination is considered extremely low, or negligible, during hysterosocopy. Hysteroscopic procedures in COVID-19–positive patients with life-threatening conditions or in patients in whom delaying the procedure could worsen outcomes should be performed taking appropriate measures. Patients who test negative for COVID-19 (confirmed by PCR) and require hysteroscopic procedures, should be treated using universal precautions. ●

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25:e936-e945.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843-1844.

- Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:793-798.

- Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al; Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e261-e270.

- American College of Surgeons, American Society of Aesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, American Hospital Association. Joint Statement: Roadmap for resuming elective surgery after COVID-19 pandemic. April 16, 2020. https://www.aorn.org/guidelines/aorn-support/roadmap-for-resuming-elective-surgery-after-covid-19. Accessed August 27, 2020.

- Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386-389.

- Mowbray NG, Ansell J, Horwood J, et al. Safe management of surgical smoke in the age of COVID-19. Br J Surg. May 3, 2020. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11679.

- Cohen SL, Liu G, Abrao M, et al. Perspectives on surgery in the time of COVID-19: safety first. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:792-793.

- COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:703-708.

- Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568-576.

- Aslan MM, Yuvaci HU, Köse O, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not present in the vaginal fluid of pregnant women with COVID-19. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1-3. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1793318.

- Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:833-840.

- Prisant N, Bujan L, Benichou H, et al. Zika virus in the female genital tract. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1000-1001.

- Rodriguez LL, De Roo A, Guimard Y, et al. Persistence and genetic stability of Ebola virus during the outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999;179 Suppl 1:S170-S176.

- Qiu L, Liu X, Xiao M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not detectable in the vaginal fluid of women with severe COVID-19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:813-817.

- Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, et al. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID-19 outbreak: a narrative review and clinical considerations. Ann Surg. April 17, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926.

- Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:857-863.

- Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e5-e6.

- Catena U. Surgical smoke in hysteroscopic surgery: does it really matter in COVID-19 times? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2020;12:67-68.

- Carugno J, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Alonso L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic. Impact on hysteroscopic procedures: a consensus statement from the Global Congress of Hysteroscopy Scientific Committee. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:988-992.

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an international collaborative group. Oncologist. 2020;25:e936-e945.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. February 24, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

- Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843-1844.

- Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:793-798.

- Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al; Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e261-e270.

- American College of Surgeons, American Society of Aesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, American Hospital Association. Joint Statement: Roadmap for resuming elective surgery after COVID-19 pandemic. April 16, 2020. https://www.aorn.org/guidelines/aorn-support/roadmap-for-resuming-elective-surgery-after-covid-19. Accessed August 27, 2020.

- Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386-389.

- Mowbray NG, Ansell J, Horwood J, et al. Safe management of surgical smoke in the age of COVID-19. Br J Surg. May 3, 2020. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11679.

- Cohen SL, Liu G, Abrao M, et al. Perspectives on surgery in the time of COVID-19: safety first. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:792-793.

- COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922.

- Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office operative hysteroscopy: an update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208.

- Cicinelli E. Hysteroscopy without anesthesia: review of recent literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:703-708.

- Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568-576.

- Aslan MM, Yuvaci HU, Köse O, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not present in the vaginal fluid of pregnant women with COVID-19. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020:1-3. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1793318.

- Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:833-840.

- Prisant N, Bujan L, Benichou H, et al. Zika virus in the female genital tract. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1000-1001.

- Rodriguez LL, De Roo A, Guimard Y, et al. Persistence and genetic stability of Ebola virus during the outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999;179 Suppl 1:S170-S176.

- Qiu L, Liu X, Xiao M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not detectable in the vaginal fluid of women with severe COVID-19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:813-817.

- Brat GA, Hersey S, Chhabra K, et al. Protecting surgical teams during the COVID-19 outbreak: a narrative review and clinical considerations. Ann Surg. April 17, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003926.

- Kwak HD, Kim SH, Seo YS, et al. Detecting hepatitis B virus in surgical smoke emitted during laparoscopic surgery. Occup Environ Med. 2016;73:857-863.

- Zheng MH, Boni L, Fingerhut A. Minimally invasive surgery and the novel coronavirus outbreak: lessons learned in China and Italy. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e5-e6.

- Catena U. Surgical smoke in hysteroscopic surgery: does it really matter in COVID-19 times? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2020;12:67-68.

- Carugno J, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Alonso L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic. Impact on hysteroscopic procedures: a consensus statement from the Global Congress of Hysteroscopy Scientific Committee. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:988-992.

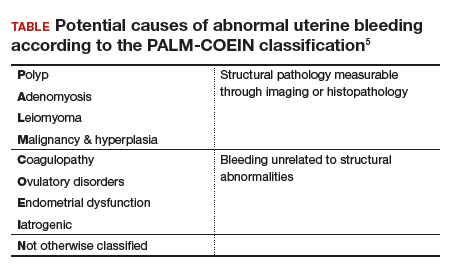

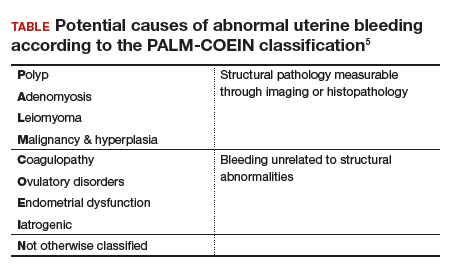

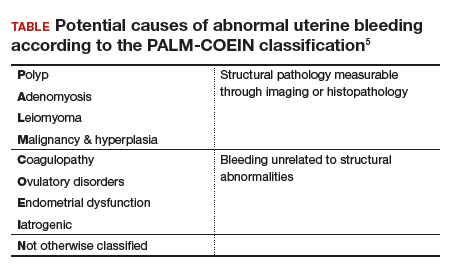

New hormonal medical treatment is an important advance for AUB caused by uterine fibroids

Uterine leiomyomata (fibroids) are the most common pelvic tumor diagnosed in women.1 Women with symptomatic fibroids often report abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) and pelvic cramping, fullness, or pain. Fibroids also may cause frequency of urination and contribute to fertility and pregnancy problems. Treatment options for the AUB caused by fibroids include, but are not limited to, hysterectomy, myomectomy, uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation, insertion of a levonorgestrel intrauterine device, focused ultrasound surgery, radiofrequency ablation, leuprolide acetate, and elagolix plus low-dose hormone add-back (Oriahnn; AbbVie, North Chicago, Illinois).1 Oriahnn is the most recent addition to our treatment armamentarium for fibroids and represents the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved long-term hormonal option for AUB caused by fibroids.

Gene dysregulation contributes to fibroid development

Most uterine fibroids are clonal tumors, which develop following a somatic mutation in a precursor uterine myocyte. The somatic mutation causes gene dysregulation that stimulates cell growth resulting in a benign tumor mass. The majority of fibroids contain a mutation in one of the following 6 genes: mediator complex subunit 12 (MED12), high mobility group AT-hook (HMGA2 or HMGA1), RAD51B, fumarate hydratase (FH), collagen type IV, alpha 5 chain (COL4A5), or collagen type IV alpha 6 chain (COL4A6).2

Gene dysregulation in fibroids may arise following chromothripsis of the uterine myocyte genome

Chromothripsis is a catastrophic intracellular genetic event in which one or more chromosomes are broken and reassemble in a new nucleic acid sequence, producing a derivative chromosome that contains complex genetic rearrangements.3 Chromothripsis is believed to occur frequently in uterine myocytes. It is unknown why uterine myocytes are susceptible to chromothripsis,3 or why a catastrophic intracellular event such as chromothripsis results in preferential mutations in the 6 genes that are associated with myoma formation.

Estrogen and progesterone influence fibroid size and cell activity

Although uterine fibroids are clonal tumors containing broken genes, they are also exquisitely responsive to estradiol and progesterone. Estradiol and progesterone play an important role in regulating fibroid size and function.4 Estrogen stimulates uterine fibroids to increase in size. In a hypoestrogenic state, uterine fibroids decrease in size. In addition, a hypoestrogenic state results in an atrophic endometrium and thereby reduces AUB. For women with uterine fibroids and AUB, a reversible hypoestrogenic state can be induced either with a parenteral GnRH-agonist analogue (leuprolide) or an oral GnRH-antagonist (elagolix). Both leuprolide and elagolix are approved for the treatment of uterine fibroids (see below).

Surprisingly, progesterone stimulates cell division in normal uterine myocytes and fibroid cells.5 In the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, uterine myocyte mitoses are more frequent than in the follicular phase. In addition, synthetic progestins appear to maintain fibroid size in a hypoestrogenic environment. In one randomized trial, women with uterine fibroids treated with leuprolide acetate plus a placebo pill for 24 weeks had a 51% reduction in uterine volume as measured by ultrasound.6 Women with uterine fibroids treated with leuprolide acetate plus the synthetic progestin, oral medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg daily, had only a 15% reduction in uterine volume.6 This finding suggests that synthetic progestins partially block the decrease in uterine volume that occurs in a hypoestrogenic state.

Further evidence that progesterone plays a role in fibroid biology is the observation that treatment of women with uterine fibroids with the antiprogestin ulipristal decreases fibroid size and reduces AUB.7-9 Ulipristal was approved for the treatment of fibroids in many countries but not the United States. Reports of severe, life-threatening liver injury—some necessitating liver transplantation—among women using ulipristal prompted the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2020 to recommend that women stop taking ulipristal. In addition, the EMA recommended that no woman should initiate ulipristal treatment at this time.10

Continue to: Leuprolide acetate...

Leuprolide acetate

Leuprolide acetate is a peptide GnRH-agonist analogue. Initiation of leuprolide treatment stimulates gonadotropin release, but with chronic administration pituitary secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) decreases, resulting in reduced ovarian follicular activity, anovulation, and low serum concentration of estradiol and progesterone. Leuprolide treatment concomitant with iron therapy is approved by the FDA for improving red blood cell volume prior to surgery in women with fibroids, AUB, and anemia.11 Among women with fibroids, AUB, and anemia, after 12 weeks of treatment, the hemoglobin concentration was ≥12 g/dL in 79% treated with leuprolide plus iron and 56% treated with iron alone.11 The FDA recommends limiting preoperative leuprolide treatment to no more than 3 months. The approved leuprolide regimens are a maximum of 3 monthly injections of leuprolide 3.75 mg or a single injection of leuprolide 11.25 mg. Leuprolide treatment prior to hysterectomy surgery for uterine fibroids usually will result in a decrease in uterine size and may facilitate vaginal hysterectomy.

Elagolix plus estradiol plus norethindrone acetate (Oriahnn)

GnRH analogues cause a hypoestrogenic state resulting in adverse effects, including moderate to severe hot flashes and a reduction in bone mineral density. One approach to reducing the unwanted effects of hot flashes and decreased bone density is to combine a GnRH analogue with low-dose steroid hormone add-back therapy. Combining a GnRH analogue with low-dose steroid hormone add-back permits long-term treatment of AUB caused by fibroids, with few hot flashes and a minimal decrease in bone mineral density. The FDA recently has approved the combination of elagolix plus low-dose estradiol and norethindrone acetate (Oriahnn) for the long-term treatment of AUB caused by fibroids.

Elagolix is a nonpeptide oral GnRH antagonist that reduces pituitary secretion of LH and FSH, resulting in a decrease in ovarian follicular activity, anovulation, and low serum concentration of estradiol and progesterone. Unlike leuprolide, which causes an initial increase in LH and FSH secretion, the initiation of elagolix treatment causes an immediate and sustained reduction in LH and FSH secretion. Combining elagolix with a low dose of estradiol and norethindrone acetate reduces the side effects of hot flashes and decreased bone density. Clinical trials have reported that the combination of elagolix (300 mg) twice daily plus estradiol (1 mg) and norethindrone acetate (0.5 mg) once daily is an effective long-term treatment of AUB caused by uterine fibroids.

To study the efficacy of elagolix (alone or with estrogen-progestin add-back therapy) for the treatment of AUB caused by uterine fibroids, two identical trials were performed,12 in which 790 women participated. The participants had a mean age of 42 years and were documented to have heavy menstrual bleeding (>80 mL blood loss per cycle) and ultrasound-diagnosed uterine fibroids. The participants were randomized to one of 3 groups:

- elagolix (300 mg twice daily) plus low-dose steroid add-back (1 mg estradiol and 0.5 mg norethindrone acetate once daily),

- elagolix 300 mg twice daily with no steroid add-back (elagolix alone), or

- placebo for 6 months.12

Menstrual blood loss was quantified using the alkaline hematin method on collected sanitary products. The primary endpoint was menstrual blood loss <80 mL per cycle as well as a ≥50% reduction in quantified blood loss from baseline during the final month of treatment. At 6 months, the percentage of women achieving the primary endpoint in the first trial was 84% (elagolix alone), 69% (elagolix plus add-back), and 9% (placebo). Mean changes from baseline in lumbar spine bone density were −2.95% (elagolix alone), −0.76% (elagolix plus add-back), and −0.21% (placebo). The percentage of women reporting hot flashes was 64% in the elagolix group, 20% in the elagolix plus low-dose steroid add-back group, and 9% in the placebo group. Results were similar in the second trial.12

The initial trials were extended to 12 months with two groups: elagolix 300 mg twice daily plus low-dose hormone add-back with 1 mg estradiol and 0.5 mg norethindrone acetate once daily (n = 218) or elagolix 300 mg twice daily (elagolix alone) (n = 98).13 Following 12 months of treatment, heavy menstrual bleeding was controlled in 88% and 89% of women treated with elagolix plus add-back and elagolix alone, respectively. Amenorrhea was reported by 65% of the women in the elagolix plus add-back group. Compared with baseline bone density, at the end of 12 months of treatment, bone mineral density in the lumbar spine was reduced by -1.5% and -4.8% in the women treated with elagolix plus add-back and elagolix alone, respectively. Compared with baseline bone density, at 1 year following completion of treatment, bone mineral density in the lumbar spine was reduced by -0.6% and -2.0% in the women treated with elagolix plus add-back and elagolix alone, respectively. Similar trends were observed in total hip and femoral neck bone density. During treatment with elagolix plus add-back, adverse effects were modest, including hot flushes (6%), night sweats (3.2%), headache (5.5%), and nausea (4.1%). Two women developed liver transaminase levels >3 times the upper limit of normal, resulting in one woman discontinuing treatment.13

Continue to: Contraindications to Oriahnn include known allergies...

Contraindications to Oriahnn include known allergies to the components of the medication (including the yellow dye tartrazine); high risk of arterial, venous thrombotic or thromboembolic disorders; pregnancy; known osteoporosis; current breast cancer or other hormonally-sensitive malignancies; known liver disease; and concurrent use of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 inhibitors, which includes many HIV antiviral medications.14 Undiagnosed AUB is a contraindication, and all women prescribed Oriahnn should have endometrial sampling before initiating treatment. Oriahnn should not be used for more than 24 months due to the risk of irreversible bone loss.14 Systemic estrogen and progestin combinations, a component of Oriahnn, increases the risk for pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction, especially in women at increased risk for these events (such as women >35 years who smoke cigarettes and women with uncontrolled hypertension).14 In two studies there was a higher incidence of depression, depressed mood, and/or tearfulness in women taking Oriahnn (3%) compared with those taking a placebo (1%).14 The FDA recommends promptly evaluating women with depressive symptoms to determine the risks of initiating and continuing Oriahnn therapy. In two studies there was a higher risk of reported alopecia among women taking Oriahnn (3.5%) compared with placebo (1%).14

It should be noted that elagolix is approved for the treatment of pelvic pain caused by endometriosis at a dose of 150 mg daily for 24 months or 200 mg twice daily for 6 months. The elagolix dose for the treatment of AUB caused by fibroids is 300 mg twice daily for up to 24 months, necessitating the addition of low-dose estradiol-norethindrone add-back to reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes and minimize the loss of bone density. Norethindrone acetate also protects the endometrium from the stimulatory effect of estradiol, reducing the risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Oriahnn is formulated as two different capsules. A yellow and white capsule contains elagolix 300 mg plus estradiol 1 mg and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg to be taken in the morning, and a blue and white capsule contains elagolix 300 mg to be taken in the evening.

AUB caused by fibroids is a common problem in gyn practice

There are many procedural interventions that are effective in reducing AUB caused by fibroids. However, prior to the approval of Oriahnn there were no hormonal medications that were FDA approved for the long-term treatment of AUB caused by fibroids. Hence, Oriahnn represents an important advance in the hormonal treatment of AUB caused by fibroids and expands the treatment options available to our patients. ●

Black women are more likely to develop fibroids and experience more severe fibroid symptoms. Obstetrician-gynecologists are experts in the diagnosis and treatment of fibroids. We play a key role in partnering with Black women to reduce fibroid disease burden.

Factors that increase the risk of developing fibroids include: increasing age, Black race, nulliparity, early menarche (<10 years of age), obesity, and consumption of red meat.1 The Nurses Health Study II is the largest prospective study of the factors that influence fibroid development.2 A total of 95,061 premenopausal nurses aged 25 to 44 years were followed from September 1989 through May 1993. Review of a sample of medical records demonstrated that the nurses participating in the study were reliable reporters of whether or not they had been diagnosed with fibroids. Based on a report of an ultrasound or hysterectomy diagnosis, the incidence rate for fibroids increased with age. Incidence rate per 1,000 women-years was 4.3 (age 25 to 29 years), 9.0 (30 to 34 years), 14.7 (age 35 to 39 years), and 22.5 (40 to 44 years). Compared with White race, Black race (but not Hispanic ethnicity or Asian race) was associated with an increased incidence of fibroids. Incidence rate per 1,000 women-years was 12.5 (White race), 37.9 (Black race), 14.5 (Hispanic ethnicity), and 10.4 (Asian race). The risk of developing fibroids was 3.25 times (95% CI, 2.71 to 3.88) greater among Black compared with White women after controlling for body mass index, age at first birth, years since last birth, history of infertility, age at first oral contraceptive use, marital status, and current alcohol use.2

Other epidemiology studies also report an increased incidence of fibroids among Black women.3,4 The size of the uterus, the size and number of fibroids, and the severity of fibroid symptoms are greater among Black versus White women.5,6 The molecular factors that increase fibroid incidence among Black women are unknown. Given the burden of fibroid disease among Black women, obstetrician-gynecologists are best positioned to ensure early diagnosis and to develop an effective follow-up and treatment plan for affected women.

References

1. Stewart EA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Catherino WH, et al. Uterine fibroids. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16043.

2. Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:967-973.

3. Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

4. Brett KM, Marsh JV, Madans JH. Epidemiology of hysterectomy in the United States: demographic and reproductive factors in a nationally representative sample. J Womens Health. 1997;6:309-316.

5. Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1988719892.

6. Huyck KL, Panhuysen CI, Cuenco KT, et al. The impact of race as a risk factor for symptom severity and age at diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata among affected sisters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:168.e1-e9.

- Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1646-1655.