User login

Weight Loss in Obesity May Create ‘Positive’ Hormone Changes

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In middle-aged patients with severe obesity, changes in endogenous sex hormones may be proportional to the amount of weight loss after bariatric surgery and dietary intervention, leading to an improved hormonal balance, with more pronounced androgen changes in women.

METHODOLOGY:

- Obesity-related hormonal imbalances are common among those seeking weight loss treatment.

- This prospective observational study evaluated the incremental effect of weight loss by three bariatric procedures and a dietary intervention on endogenous sex hormones in men and women over 3 years.

- The study included 61 adults (median age, 50.9 years; baseline mean body mass index, 40.2; 72% women) from obesity clinics and private bariatric services in Sydney, Australia, between 2009 and 2012, who underwent bariatric surgery or received dietary interventions based on their probability of diabetes remission.

- The researchers evaluated weight loss and hormone levels at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Changes in hormones were also compared among patients who received dietary intervention and those who underwent bariatric procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic gastric banding.

TAKEAWAY:

- In women, testosterone levels decreased and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) levels increased at 6 months; these changes were maintained at 24 and 36 months and remained statistically significant when controlled for age and menopausal status.

- In men, testosterone levels were significantly higher at 12, 24, and 36 months, and SHBG levels increased at 12 and 24 months. There were no differences in the estradiol levels among men and women.

- Women who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery experienced the greatest weight loss and the largest reduction (54%) in testosterone levels (P = .004), and sleeve gastrectomy led to an increase of 51% in SHBG levels (P = .0001), all compared with dietary interventions. In men, there were no differences in testosterone and SHBG levels between the diet and surgical groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Ongoing monitoring of hormone levels and metabolic parameters is crucial for patients undergoing bariatric procedures to ensure long-term optimal health outcomes,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Malgorzata M. Brzozowska, MD, PhD, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, and was published online in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The main limitations were a small sample size, lack of randomization, and absence of data on clinical outcomes related to hormone changes. Additionally, the researchers did not evaluate women for polycystic ovary syndrome or menstrual irregularities, and the clinical significance of testosterone reductions within the normal range remains unknown.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. Some authors have received honoraria and consulting and research support from various pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gut Microbiota Tied to Food Addiction Vulnerability

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Food addiction, characterized by a loss of control over food intake, may promote obesity and alter gut microbiota composition.

- Researchers used the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 criteria to classify extreme food addiction and nonaddiction in mouse models and humans.

- The gut microbiota between addicted and nonaddicted mice were compared to identify factors related to food addiction in the murine model. Researchers subsequently gave mice drinking water with the prebiotics lactulose or rhamnose and the bacterium Blautia wexlerae, which has been associated with a reduced risk for obesity and diabetes.

- Gut microbiota signatures were also analyzed in 15 individuals with food addiction and 13 matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

- In both humans and mice, gut microbiome signatures suggested possible nonbeneficial effects of bacteria in the Proteobacteria phylum and potential protective effects of Actinobacteria against the development of food addiction.

- In correlational analyses, decreased relative abundance of the species B wexlerae was observed in addicted humans and of the Blautia genus in addicted mice.

- Administration of the nondigestible carbohydrates lactulose and rhamnose, known to favor Blautia growth, led to increased relative abundance of Blautia in mouse feces, as well as “dramatic improvements” in food addiction.

- In functional validation experiments, oral administration of B wexlerae in mice led to similar improvement.

IN PRACTICE:

“This novel understanding of the role of gut microbiota in the development of food addiction may open new approaches for developing biomarkers and innovative therapies for food addiction and related eating disorders,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Solveiga Samulėnaitė, a doctoral student at Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, was published online in Gut.

LIMITATIONS:

Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying the potential use of gut microbiota for treating food addiction and to test the safety and efficacy in humans.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by La Caixa Health and numerous grants from Spanish ministries and institutions and the European Union. No competing interests were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Food addiction, characterized by a loss of control over food intake, may promote obesity and alter gut microbiota composition.

- Researchers used the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 criteria to classify extreme food addiction and nonaddiction in mouse models and humans.

- The gut microbiota between addicted and nonaddicted mice were compared to identify factors related to food addiction in the murine model. Researchers subsequently gave mice drinking water with the prebiotics lactulose or rhamnose and the bacterium Blautia wexlerae, which has been associated with a reduced risk for obesity and diabetes.

- Gut microbiota signatures were also analyzed in 15 individuals with food addiction and 13 matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

- In both humans and mice, gut microbiome signatures suggested possible nonbeneficial effects of bacteria in the Proteobacteria phylum and potential protective effects of Actinobacteria against the development of food addiction.

- In correlational analyses, decreased relative abundance of the species B wexlerae was observed in addicted humans and of the Blautia genus in addicted mice.

- Administration of the nondigestible carbohydrates lactulose and rhamnose, known to favor Blautia growth, led to increased relative abundance of Blautia in mouse feces, as well as “dramatic improvements” in food addiction.

- In functional validation experiments, oral administration of B wexlerae in mice led to similar improvement.

IN PRACTICE:

“This novel understanding of the role of gut microbiota in the development of food addiction may open new approaches for developing biomarkers and innovative therapies for food addiction and related eating disorders,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Solveiga Samulėnaitė, a doctoral student at Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, was published online in Gut.

LIMITATIONS:

Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying the potential use of gut microbiota for treating food addiction and to test the safety and efficacy in humans.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by La Caixa Health and numerous grants from Spanish ministries and institutions and the European Union. No competing interests were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Food addiction, characterized by a loss of control over food intake, may promote obesity and alter gut microbiota composition.

- Researchers used the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 criteria to classify extreme food addiction and nonaddiction in mouse models and humans.

- The gut microbiota between addicted and nonaddicted mice were compared to identify factors related to food addiction in the murine model. Researchers subsequently gave mice drinking water with the prebiotics lactulose or rhamnose and the bacterium Blautia wexlerae, which has been associated with a reduced risk for obesity and diabetes.

- Gut microbiota signatures were also analyzed in 15 individuals with food addiction and 13 matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

- In both humans and mice, gut microbiome signatures suggested possible nonbeneficial effects of bacteria in the Proteobacteria phylum and potential protective effects of Actinobacteria against the development of food addiction.

- In correlational analyses, decreased relative abundance of the species B wexlerae was observed in addicted humans and of the Blautia genus in addicted mice.

- Administration of the nondigestible carbohydrates lactulose and rhamnose, known to favor Blautia growth, led to increased relative abundance of Blautia in mouse feces, as well as “dramatic improvements” in food addiction.

- In functional validation experiments, oral administration of B wexlerae in mice led to similar improvement.

IN PRACTICE:

“This novel understanding of the role of gut microbiota in the development of food addiction may open new approaches for developing biomarkers and innovative therapies for food addiction and related eating disorders,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Solveiga Samulėnaitė, a doctoral student at Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, was published online in Gut.

LIMITATIONS:

Further research is needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying the potential use of gut microbiota for treating food addiction and to test the safety and efficacy in humans.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by La Caixa Health and numerous grants from Spanish ministries and institutions and the European Union. No competing interests were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity: The Basics

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Non-Prescription Semaglutide Purchased Online Poses Risks

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.

“Semaglutide products are actively being sold without prescription by illegal online pharmacies, with vendors shipping unregistered and falsified products,” wrote Amir Reza Ashraf, PharmD, of the University of Pécs, Hungary, and colleagues in their paper, published online on August 2, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted in July 2023, but its publication comes a week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert about dosing errors in compounded semaglutide, which typically does require a prescription.

Study coauthor Tim K. Mackey, PhD, told this news organization, “Compounding pharmacies are another element of this risk that has become more prominent now but arguably have more controls if prescribed appropriately, while the traditional ‘no-prescription’ online market still exists and will continue to evolve.”

Overall, said Dr. Mackey, professor of global health at the University of California San Diego and director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute,

He advises clinicians to actively discuss with their patients the risks associated with semaglutide and, specifically, the dangers of buying it online. “Clinicians can act as a primary information source for patient safety information by letting their patients know about these risks ... and also asking where patients get their medications in case they are concerned about reports of adverse events or other patient safety issues.”

Buyer Beware: Online Semaglutide Purchases Not as They Seem

The investigators began by searching online for websites advertising semaglutide without a prescription. They ordered products from six online vendors that showed up prominently in the searches. Of those, three offered prefilled 0.25 mg/dose semaglutide injection pens, while the other three sold vials of lyophilized semaglutide powder to be reconstituted to solution for injection. Prices for the smallest dose and quantity ranged from $113 to $360.

Only three of the ordered products — all vials — actually showed up. The advertised prefilled pens were all nondelivery scams, with requests for an extra payment of $650-$1200 purportedly to clear customs. This was confirmed as fraudulent by customs agencies, the authors noted.

The three vial products were received and assessed physically, of both the packaging and the actual product, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine purity and peptide concentration, and microbiologically, to examine sterility.

Using a checklist from the International Pharmaceutical Federation, Dr. Ashraf and colleagues found “clear discrepancies in regulatory registration information, accurate labeling, and evidence products were likely unregistered or unlicensed.”

Quality testing showed that one sample had an elevated presence of endotoxin suggesting possible contamination. While all three actually did contain semaglutide, the measured content exceeded the labeled amount by 29%-39%, posing a risk that users could receive up to 39% more than intended per injection, “particularly concerning if a consumer has to reconstitute and self-inject,” Dr. Mackey noted.

At least one of these sites in this study, “semaspace.com,” was subsequently sent a warning letter by the FDA for unauthorized semaglutide sale, Mackey noted.

Unfortunately, he told this news organization, these dangers are likely to persist. “There is a strong market opportunity to introduce counterfeit and unauthorized versions of semaglutide. Counterfeiters will continue to innovate with where they sell products, what products they offer, and how they mislead consumers about the safety and legality of what they are offering online. We are likely just at the beginning of counterfeiting of semaglutide, and it is likely that these false products will become endemic in our supply chain.”

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund. The authors had no further disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.

“Semaglutide products are actively being sold without prescription by illegal online pharmacies, with vendors shipping unregistered and falsified products,” wrote Amir Reza Ashraf, PharmD, of the University of Pécs, Hungary, and colleagues in their paper, published online on August 2, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted in July 2023, but its publication comes a week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert about dosing errors in compounded semaglutide, which typically does require a prescription.

Study coauthor Tim K. Mackey, PhD, told this news organization, “Compounding pharmacies are another element of this risk that has become more prominent now but arguably have more controls if prescribed appropriately, while the traditional ‘no-prescription’ online market still exists and will continue to evolve.”

Overall, said Dr. Mackey, professor of global health at the University of California San Diego and director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute,

He advises clinicians to actively discuss with their patients the risks associated with semaglutide and, specifically, the dangers of buying it online. “Clinicians can act as a primary information source for patient safety information by letting their patients know about these risks ... and also asking where patients get their medications in case they are concerned about reports of adverse events or other patient safety issues.”

Buyer Beware: Online Semaglutide Purchases Not as They Seem

The investigators began by searching online for websites advertising semaglutide without a prescription. They ordered products from six online vendors that showed up prominently in the searches. Of those, three offered prefilled 0.25 mg/dose semaglutide injection pens, while the other three sold vials of lyophilized semaglutide powder to be reconstituted to solution for injection. Prices for the smallest dose and quantity ranged from $113 to $360.

Only three of the ordered products — all vials — actually showed up. The advertised prefilled pens were all nondelivery scams, with requests for an extra payment of $650-$1200 purportedly to clear customs. This was confirmed as fraudulent by customs agencies, the authors noted.

The three vial products were received and assessed physically, of both the packaging and the actual product, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine purity and peptide concentration, and microbiologically, to examine sterility.

Using a checklist from the International Pharmaceutical Federation, Dr. Ashraf and colleagues found “clear discrepancies in regulatory registration information, accurate labeling, and evidence products were likely unregistered or unlicensed.”

Quality testing showed that one sample had an elevated presence of endotoxin suggesting possible contamination. While all three actually did contain semaglutide, the measured content exceeded the labeled amount by 29%-39%, posing a risk that users could receive up to 39% more than intended per injection, “particularly concerning if a consumer has to reconstitute and self-inject,” Dr. Mackey noted.

At least one of these sites in this study, “semaspace.com,” was subsequently sent a warning letter by the FDA for unauthorized semaglutide sale, Mackey noted.

Unfortunately, he told this news organization, these dangers are likely to persist. “There is a strong market opportunity to introduce counterfeit and unauthorized versions of semaglutide. Counterfeiters will continue to innovate with where they sell products, what products they offer, and how they mislead consumers about the safety and legality of what they are offering online. We are likely just at the beginning of counterfeiting of semaglutide, and it is likely that these false products will become endemic in our supply chain.”

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund. The authors had no further disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Semaglutide products sold online without a prescription may pose multiple risks to consumers, new research found.

Of six test purchases of semaglutide products offered online without a prescription, only three were actually received. The other three vendors demanded additional payment. Of the three delivered, one was potentially contaminated, and all three contained higher concentrations of semaglutide than indicated on the label, potentially resulting in an overdose.

“Semaglutide products are actively being sold without prescription by illegal online pharmacies, with vendors shipping unregistered and falsified products,” wrote Amir Reza Ashraf, PharmD, of the University of Pécs, Hungary, and colleagues in their paper, published online on August 2, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted in July 2023, but its publication comes a week after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert about dosing errors in compounded semaglutide, which typically does require a prescription.

Study coauthor Tim K. Mackey, PhD, told this news organization, “Compounding pharmacies are another element of this risk that has become more prominent now but arguably have more controls if prescribed appropriately, while the traditional ‘no-prescription’ online market still exists and will continue to evolve.”

Overall, said Dr. Mackey, professor of global health at the University of California San Diego and director of the Global Health Policy and Data Institute,

He advises clinicians to actively discuss with their patients the risks associated with semaglutide and, specifically, the dangers of buying it online. “Clinicians can act as a primary information source for patient safety information by letting their patients know about these risks ... and also asking where patients get their medications in case they are concerned about reports of adverse events or other patient safety issues.”

Buyer Beware: Online Semaglutide Purchases Not as They Seem

The investigators began by searching online for websites advertising semaglutide without a prescription. They ordered products from six online vendors that showed up prominently in the searches. Of those, three offered prefilled 0.25 mg/dose semaglutide injection pens, while the other three sold vials of lyophilized semaglutide powder to be reconstituted to solution for injection. Prices for the smallest dose and quantity ranged from $113 to $360.

Only three of the ordered products — all vials — actually showed up. The advertised prefilled pens were all nondelivery scams, with requests for an extra payment of $650-$1200 purportedly to clear customs. This was confirmed as fraudulent by customs agencies, the authors noted.

The three vial products were received and assessed physically, of both the packaging and the actual product, by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine purity and peptide concentration, and microbiologically, to examine sterility.

Using a checklist from the International Pharmaceutical Federation, Dr. Ashraf and colleagues found “clear discrepancies in regulatory registration information, accurate labeling, and evidence products were likely unregistered or unlicensed.”

Quality testing showed that one sample had an elevated presence of endotoxin suggesting possible contamination. While all three actually did contain semaglutide, the measured content exceeded the labeled amount by 29%-39%, posing a risk that users could receive up to 39% more than intended per injection, “particularly concerning if a consumer has to reconstitute and self-inject,” Dr. Mackey noted.

At least one of these sites in this study, “semaspace.com,” was subsequently sent a warning letter by the FDA for unauthorized semaglutide sale, Mackey noted.

Unfortunately, he told this news organization, these dangers are likely to persist. “There is a strong market opportunity to introduce counterfeit and unauthorized versions of semaglutide. Counterfeiters will continue to innovate with where they sell products, what products they offer, and how they mislead consumers about the safety and legality of what they are offering online. We are likely just at the beginning of counterfeiting of semaglutide, and it is likely that these false products will become endemic in our supply chain.”

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund. The authors had no further disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Ozempic Curbs Hunger – And Not Just for Food

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’ve been paying attention only to the headlines, when you think of “Ozempic” you’ll think of a few things: a blockbuster weight loss drug or the tip of the spear of a completely new industry — why not? A drug so popular that the people it was invented for (those with diabetes) can’t even get it.

Ozempic and other GLP-1 receptor agonists are undeniable game changers. Insofar as obesity is the number-one public health risk in the United States, antiobesity drugs hold immense promise even if all they do is reduce obesity.

In 2023, an article in Scientific Reports presented data suggesting that people on Ozempic might be reducing their alcohol intake, not just their total calories.

A 2024 article in Molecular Psychiatry found that the drug might positively impact cannabis use disorder. An article from Brain Sciences suggests that the drug reduces compulsive shopping.

A picture is starting to form, a picture that suggests these drugs curb hunger both literally and figuratively. That GLP-1 receptor agonists like Ozempic and Mounjaro are fundamentally anticonsumption drugs. In a society that — some would argue — is plagued by overconsumption, these drugs might be just what the doctor ordered.

If only they could stop people from smoking.

Oh, wait — they can.

At least it seems they can, based on a new study appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

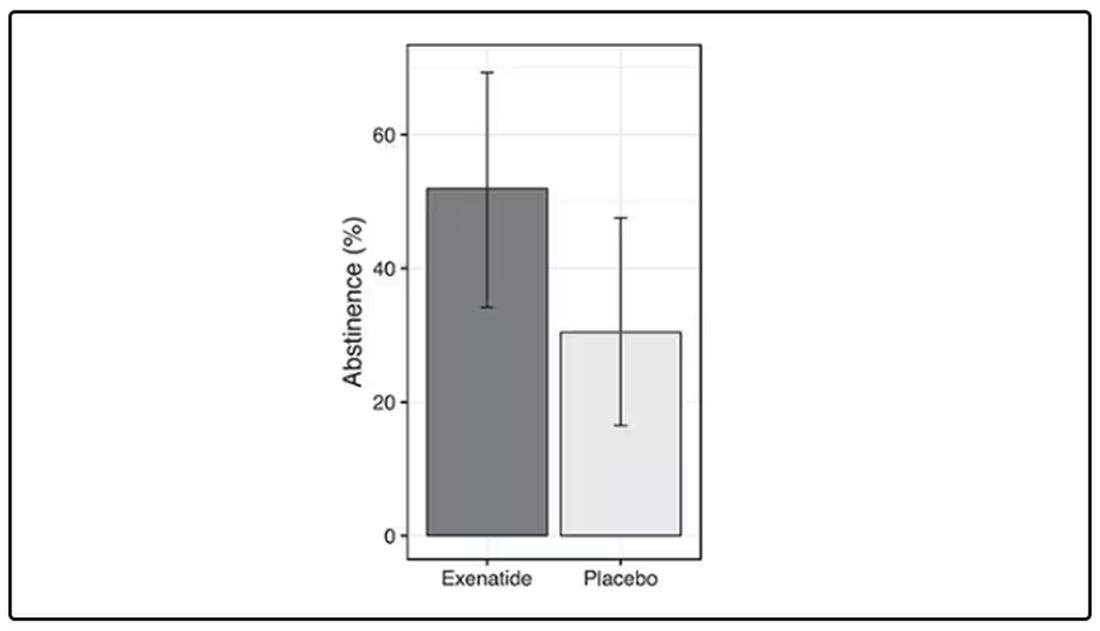

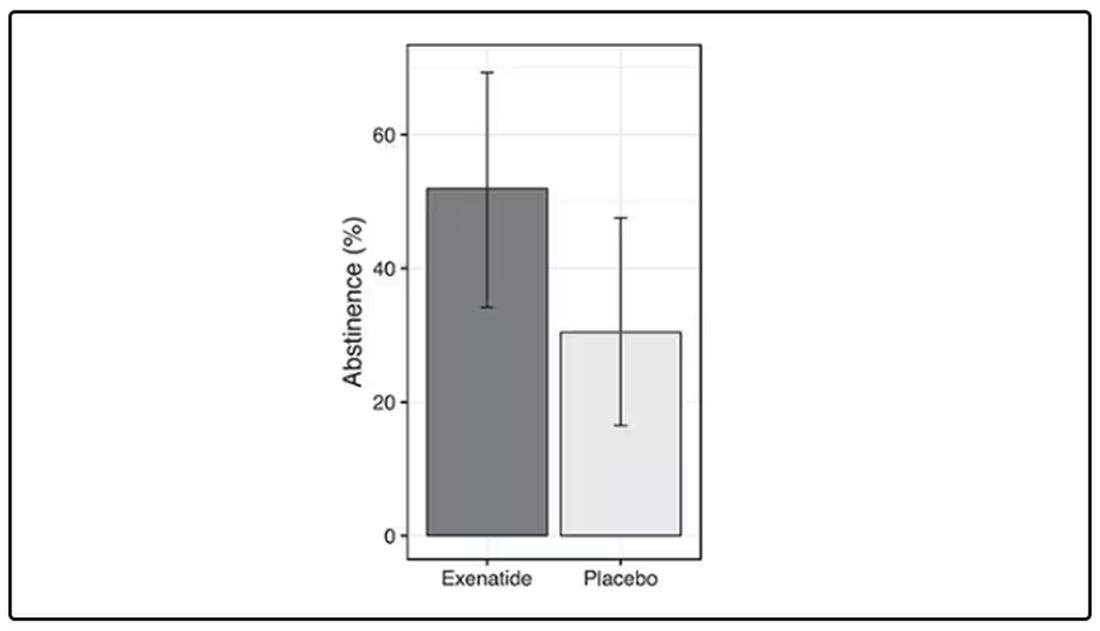

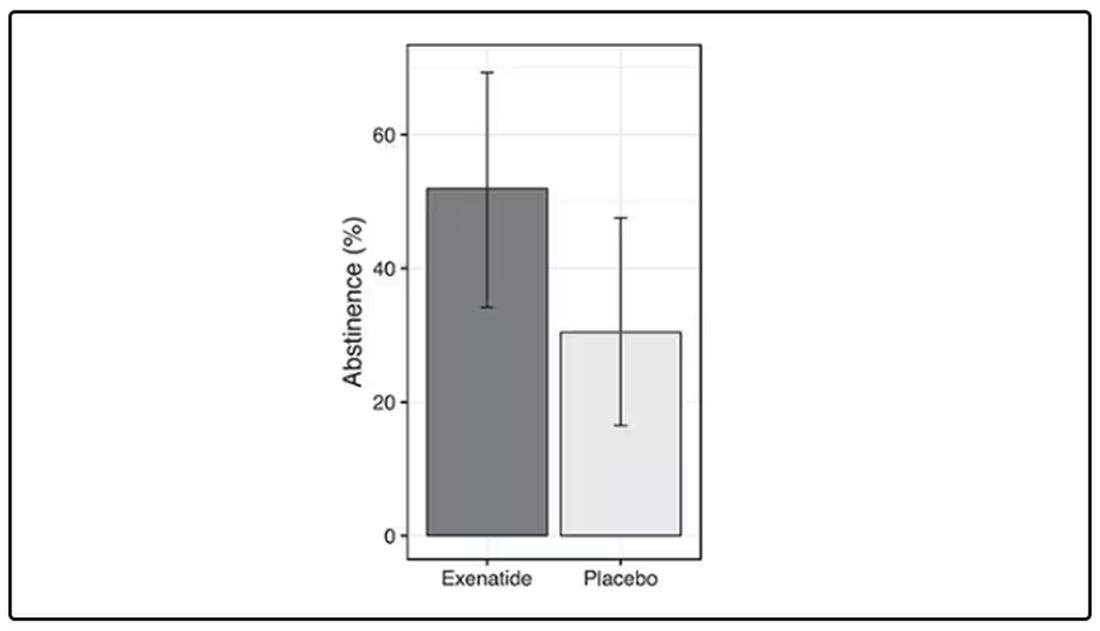

Before we get too excited, this is not a randomized trial. There actually was a small randomized trial of exenatide (Byetta), which is in the same class as Ozempic but probably a bit less potent, with promising results for smoking cessation.

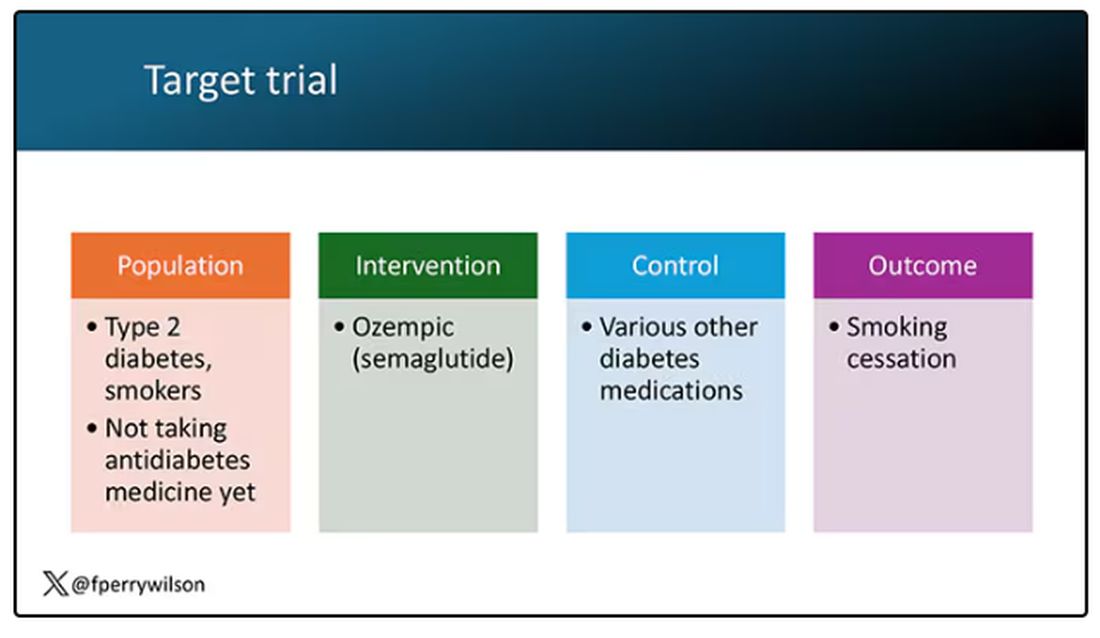

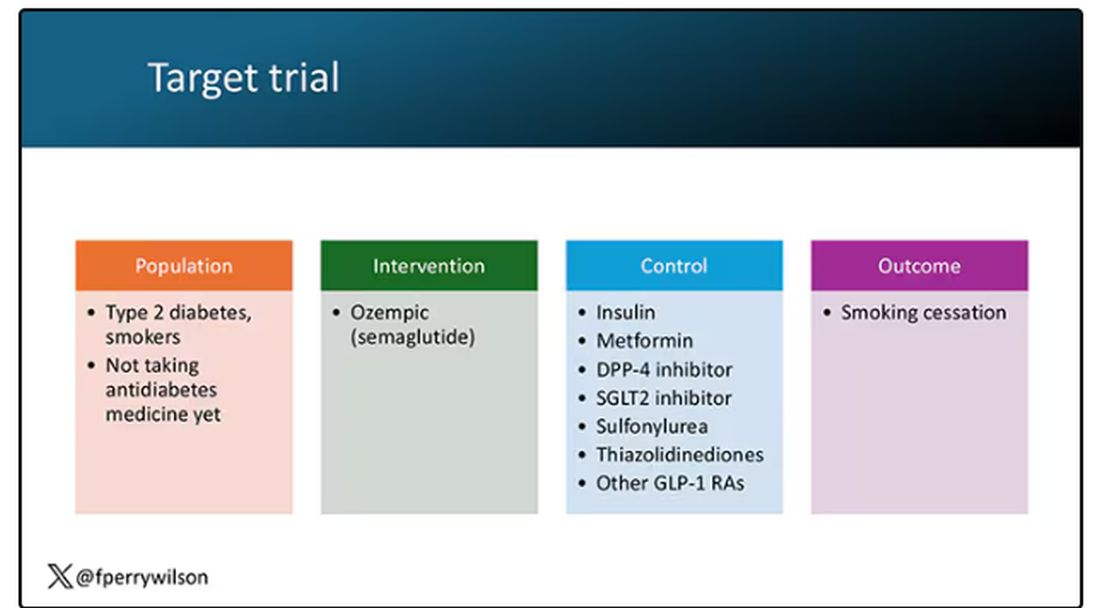

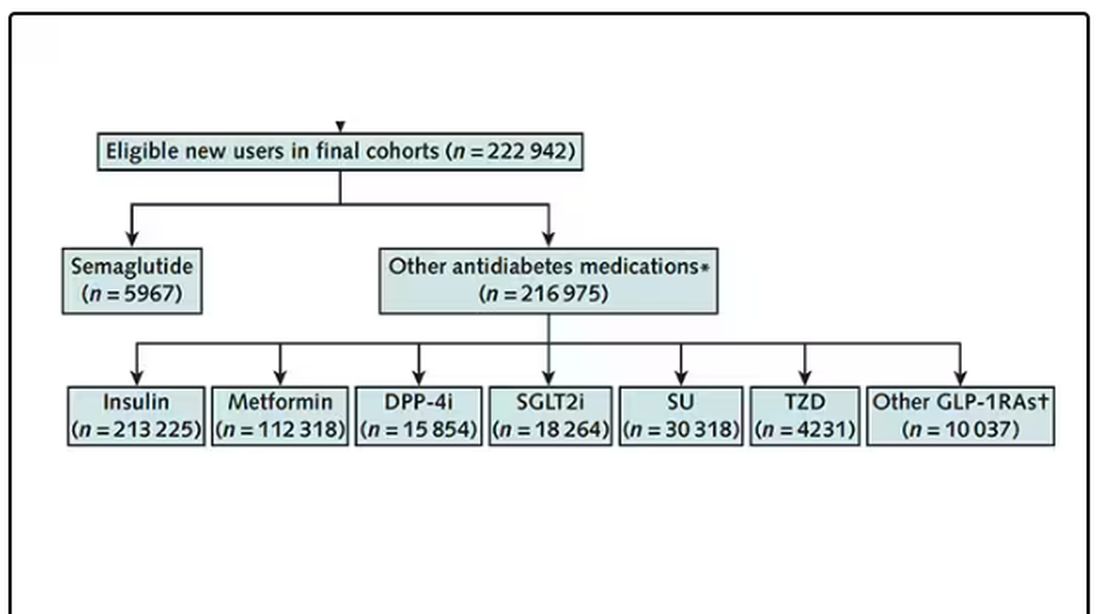

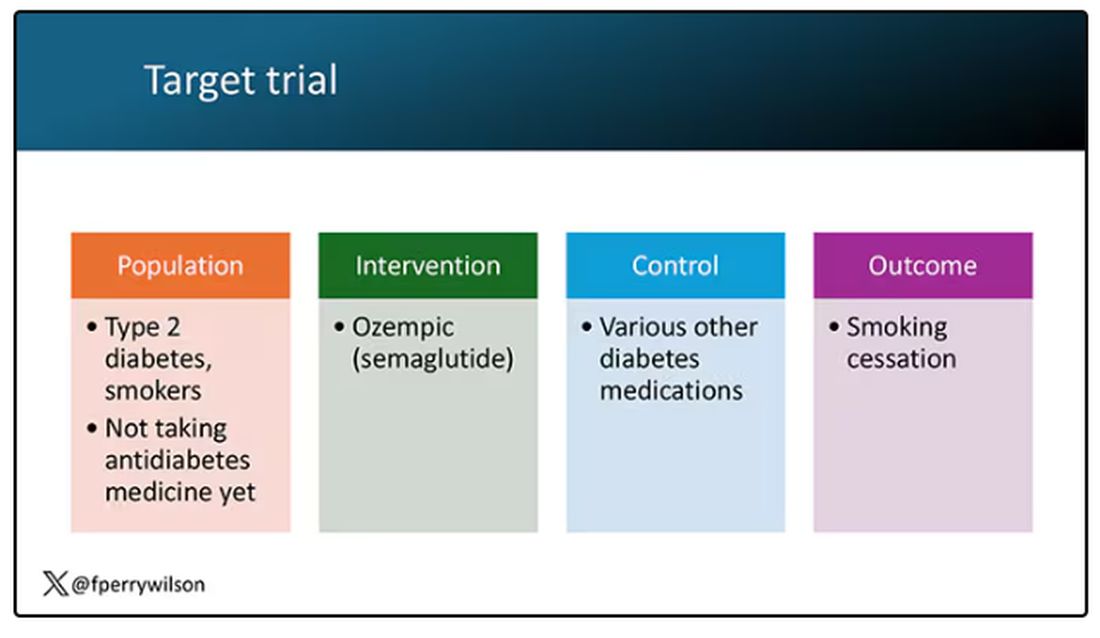

But Byetta is the weaker drug in this class; the market leader is Ozempic. So how can you figure out whether Ozempic can reduce smoking without doing a huge and expensive randomized trial? You can do what Nora Volkow and colleagues from the National Institute on Drug Abuse did: a target trial emulation study.

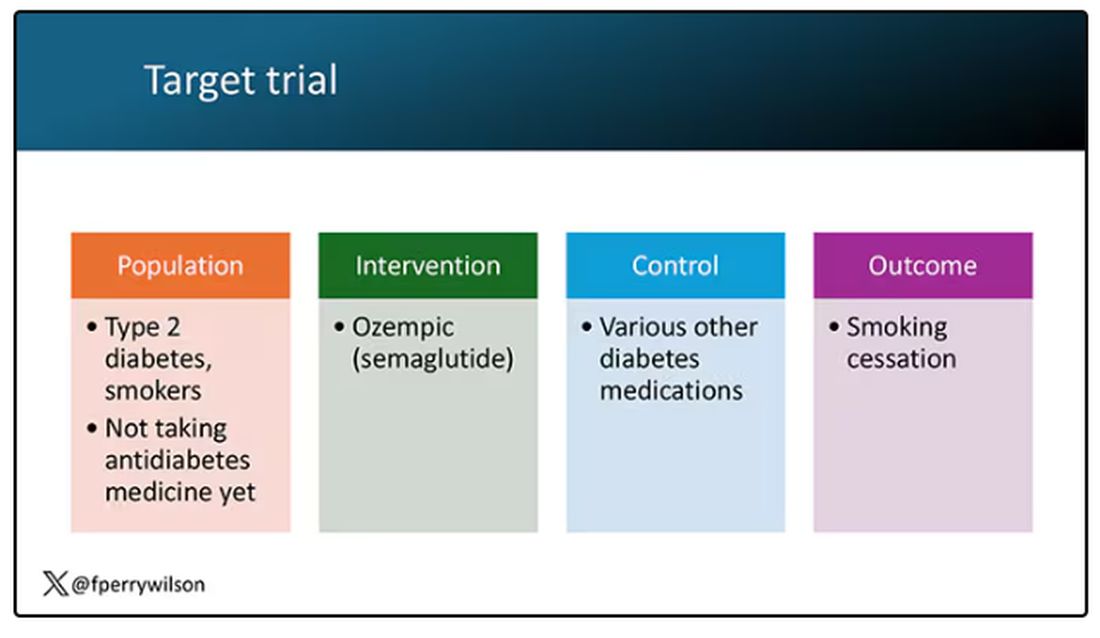

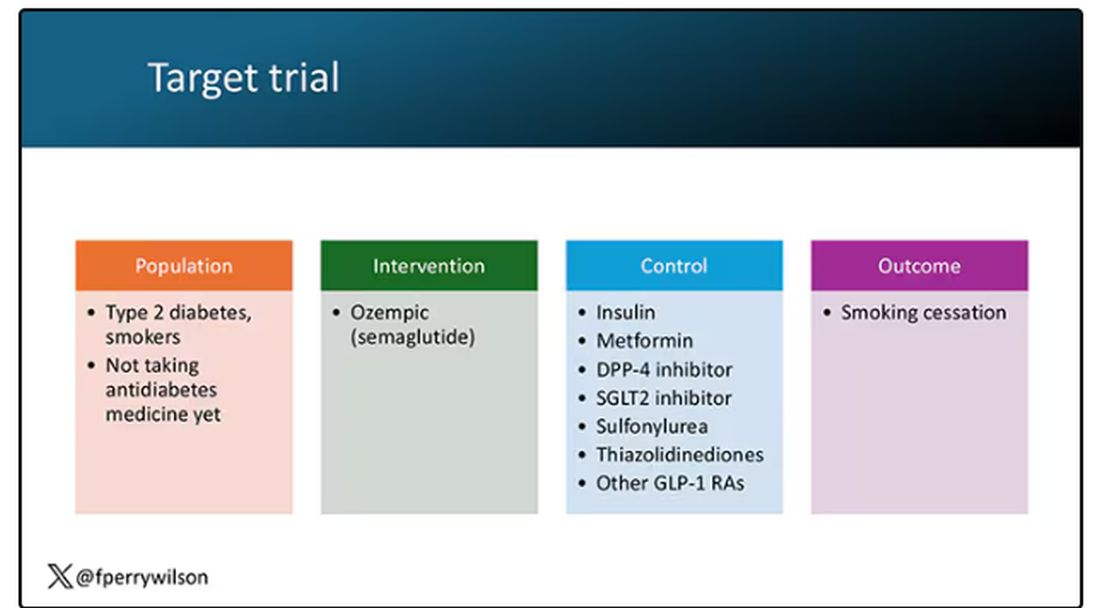

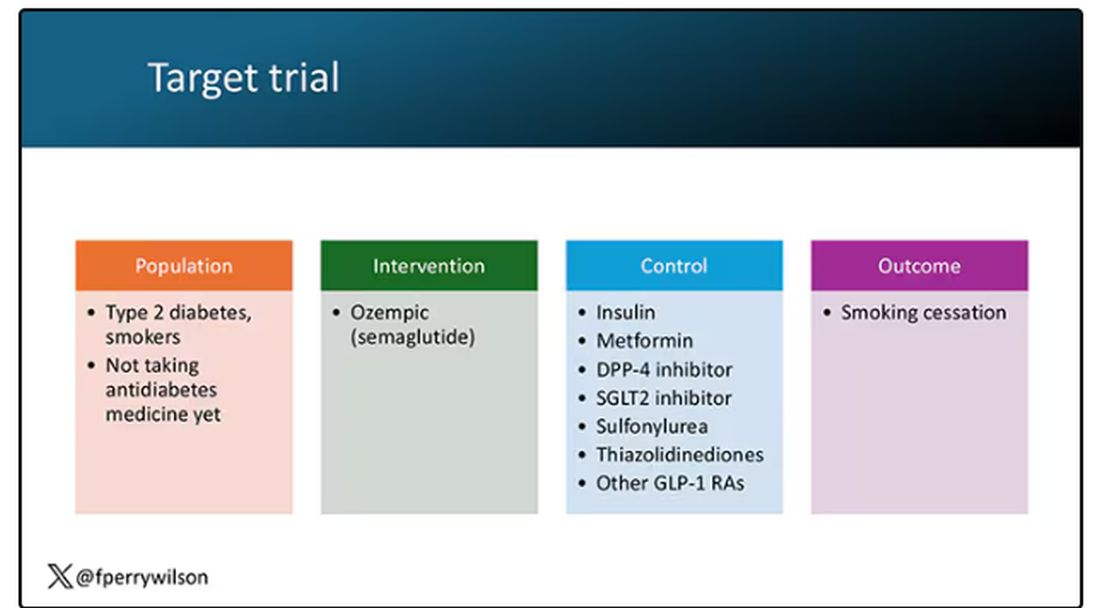

A target trial emulation study is more or less what it sounds like. First, you decide what your dream randomized controlled trial would be and you plan it all out in great detail. You define the population you would recruit, with all the relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria. You define the intervention and the control, and you define the outcome.

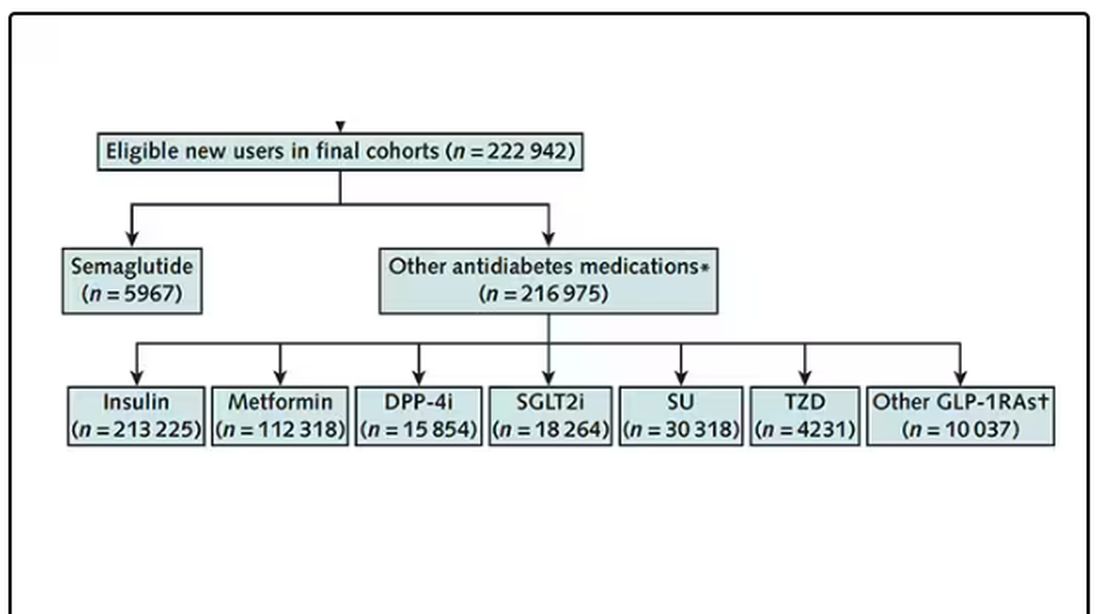

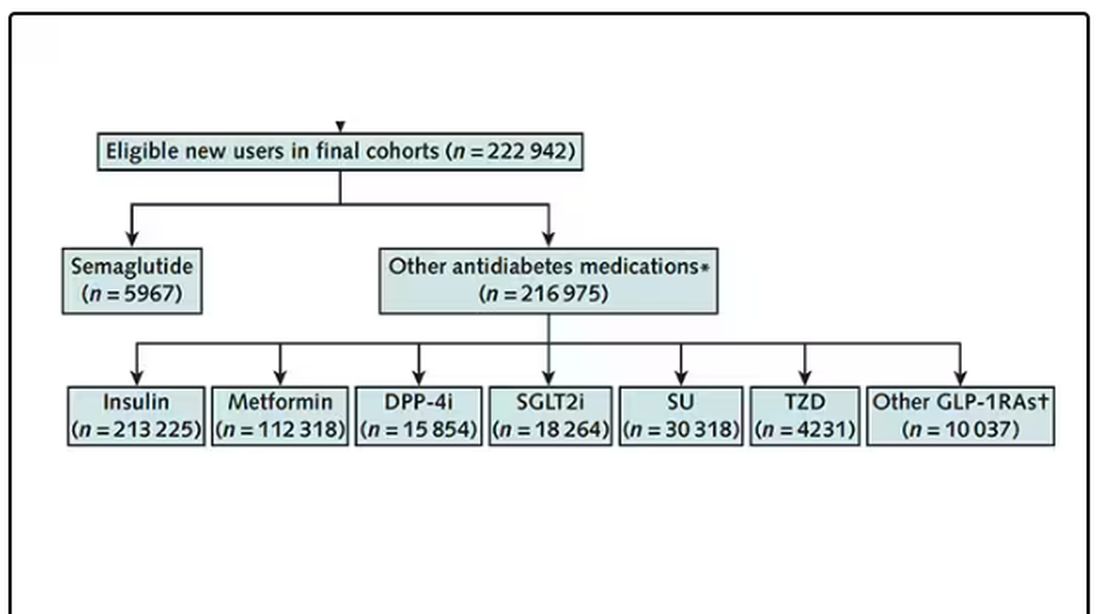

But you don’t actually do the trial. You could if someone would lend you $10-$50 million, but assuming you don’t have that lying around, you do the next best thing, which is to dig into a medical record database to find all the people who would be eligible for your imaginary trial. And you analyze them.

The authors wanted to study the effect of Ozempic on smoking among people with diabetes; that’s why all the comparator agents are antidiabetes drugs. They figured out whether these folks were smoking on the basis of a medical record diagnosis of tobacco use disorder before they started one of the drugs of interest. This code is fairly specific: If a patient has it, you can be pretty sure they are smoking. But it’s not very sensitive; not every smoker has this diagnostic code. This is an age-old limitation of using EHR data instead of asking patients, but it’s part of the tradeoff for not having to spend $50 million.

After applying all those inclusion and exclusion criteria, they have a defined population who could be in their dream trial. And, as luck would have it, some of those people really were treated with Ozempic and some really were treated with those other agents. Although decisions about what to prescribe were not randomized, the authors account for this confounding-by-indication using propensity-score matching. You can find a little explainer on propensity-score matching in an earlier column here.

It’s easy enough, using the EHR, to figure out who has diabetes and who got which drug. But how do you know who quit smoking? Remember, everyone had a diagnosis code for tobacco use disorder prior to starting Ozempic or a comparator drug. The authors decided that if the patient had a medical visit where someone again coded tobacco-use disorder, they were still smoking. If someone prescribed smoking cessation meds like a nicotine patch or varenicline, they were obviously still smoking. If someone billed for tobacco-cessation counseling, the patient is still smoking. We’ll get back to the implications of this outcome definition in a minute.

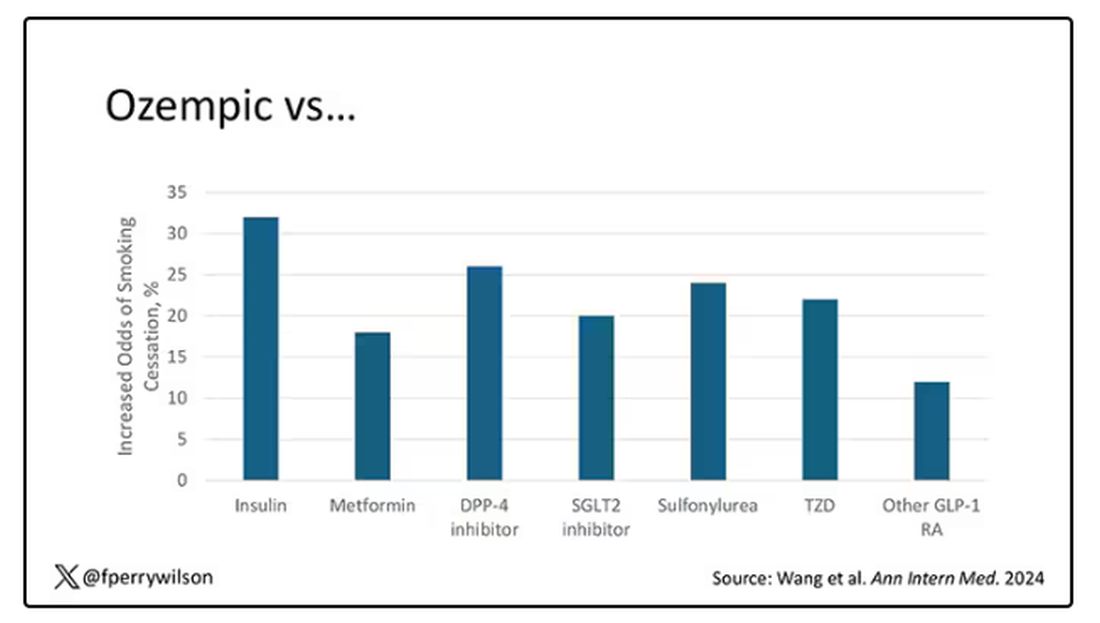

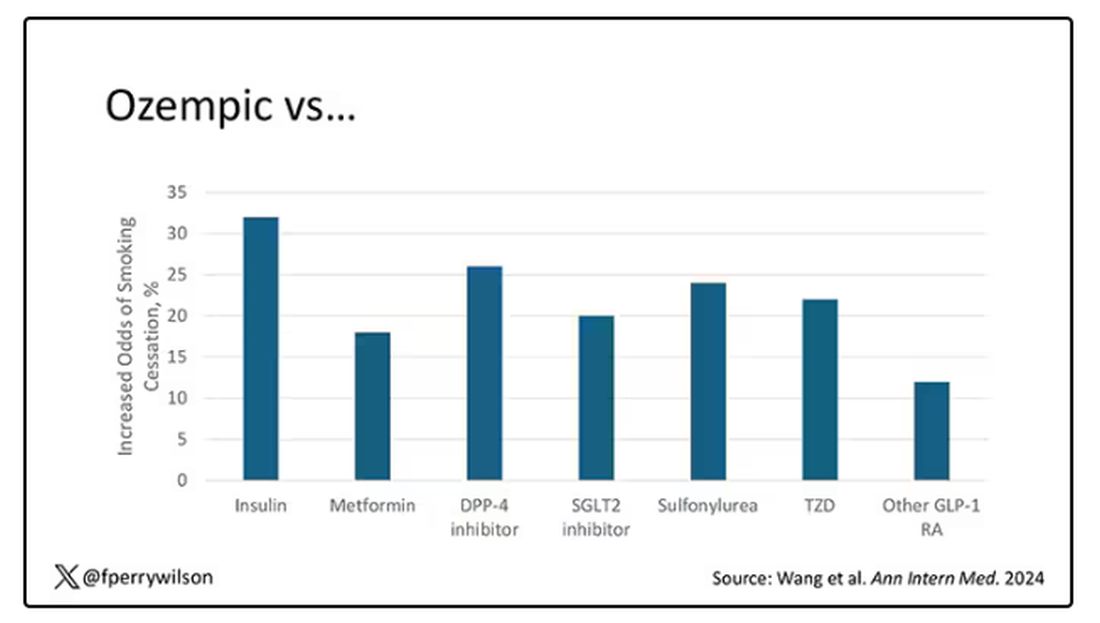

Let’s talk about the results, which are pretty intriguing.

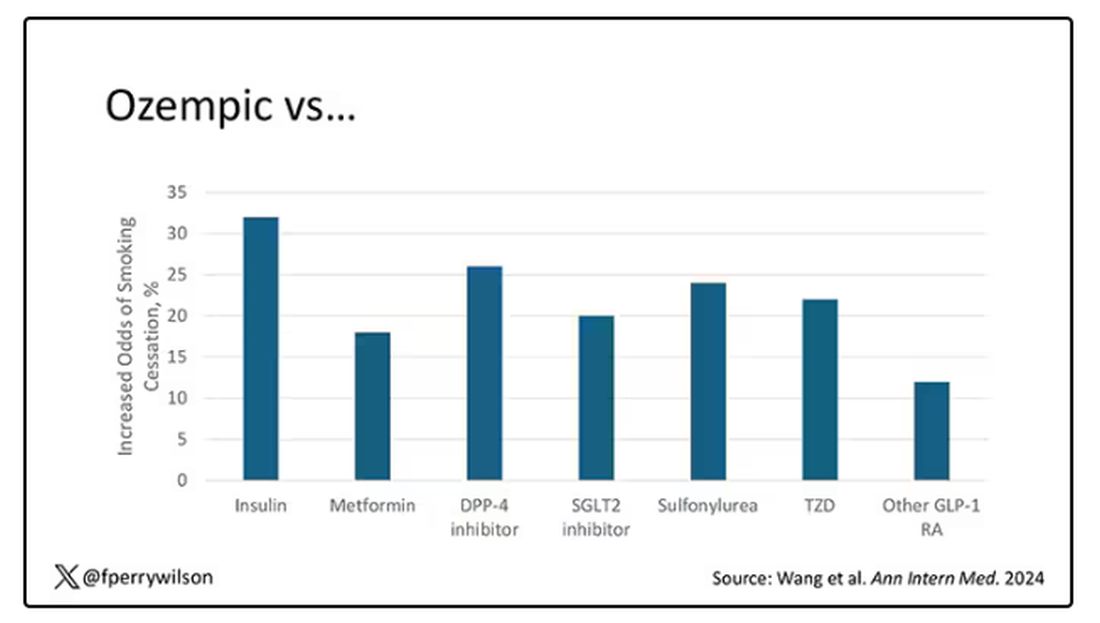

When Ozempic is compared with insulin among smokers with diabetes, those on Ozempic were about 30% more likely to quit smoking. They were about 18% more likely to quit smoking than those who took metformin. They were even slightly more likely to quit smoking than those on other GLP-1 receptor antagonists, though I should note that Mounjaro, which is probably the more potent GLP-1 drug in terms of weight loss, was not among the comparators.

This is pretty impressive for a drug that was not designed to be a smoking cessation drug. It speaks to this emerging idea that these drugs do more than curb appetite by slowing down gastric emptying or something. They work in the brain, modulating some of the reward circuitry that keeps us locked into our bad habits.

There are, of course, some caveats. As I pointed out, this study captured the idea of “still smoking” through the use of administrative codes in the EHR and prescription of smoking cessation aids. You could see similar results if taking Ozempic makes people less likely to address their smoking at all; maybe they shut down the doctor before they even talk about it, or there is too much to discuss during these visits to even get to the subject of smoking. You could also see results like this if people taking Ozempic had fewer visits overall, but the authors showed that that, at least, was not the case.

I’m inclined to believe that this effect is real, simply because we keep seeing signals from multiple sources. If that turns out to be the case, these new “weight loss” drugs may prove to be much more than that; they may turn out to be the drugs that can finally save us from ourselves.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’ve been paying attention only to the headlines, when you think of “Ozempic” you’ll think of a few things: a blockbuster weight loss drug or the tip of the spear of a completely new industry — why not? A drug so popular that the people it was invented for (those with diabetes) can’t even get it.

Ozempic and other GLP-1 receptor agonists are undeniable game changers. Insofar as obesity is the number-one public health risk in the United States, antiobesity drugs hold immense promise even if all they do is reduce obesity.

In 2023, an article in Scientific Reports presented data suggesting that people on Ozempic might be reducing their alcohol intake, not just their total calories.

A 2024 article in Molecular Psychiatry found that the drug might positively impact cannabis use disorder. An article from Brain Sciences suggests that the drug reduces compulsive shopping.

A picture is starting to form, a picture that suggests these drugs curb hunger both literally and figuratively. That GLP-1 receptor agonists like Ozempic and Mounjaro are fundamentally anticonsumption drugs. In a society that — some would argue — is plagued by overconsumption, these drugs might be just what the doctor ordered.

If only they could stop people from smoking.

Oh, wait — they can.

At least it seems they can, based on a new study appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Before we get too excited, this is not a randomized trial. There actually was a small randomized trial of exenatide (Byetta), which is in the same class as Ozempic but probably a bit less potent, with promising results for smoking cessation.

But Byetta is the weaker drug in this class; the market leader is Ozempic. So how can you figure out whether Ozempic can reduce smoking without doing a huge and expensive randomized trial? You can do what Nora Volkow and colleagues from the National Institute on Drug Abuse did: a target trial emulation study.

A target trial emulation study is more or less what it sounds like. First, you decide what your dream randomized controlled trial would be and you plan it all out in great detail. You define the population you would recruit, with all the relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria. You define the intervention and the control, and you define the outcome.

But you don’t actually do the trial. You could if someone would lend you $10-$50 million, but assuming you don’t have that lying around, you do the next best thing, which is to dig into a medical record database to find all the people who would be eligible for your imaginary trial. And you analyze them.

The authors wanted to study the effect of Ozempic on smoking among people with diabetes; that’s why all the comparator agents are antidiabetes drugs. They figured out whether these folks were smoking on the basis of a medical record diagnosis of tobacco use disorder before they started one of the drugs of interest. This code is fairly specific: If a patient has it, you can be pretty sure they are smoking. But it’s not very sensitive; not every smoker has this diagnostic code. This is an age-old limitation of using EHR data instead of asking patients, but it’s part of the tradeoff for not having to spend $50 million.

After applying all those inclusion and exclusion criteria, they have a defined population who could be in their dream trial. And, as luck would have it, some of those people really were treated with Ozempic and some really were treated with those other agents. Although decisions about what to prescribe were not randomized, the authors account for this confounding-by-indication using propensity-score matching. You can find a little explainer on propensity-score matching in an earlier column here.

It’s easy enough, using the EHR, to figure out who has diabetes and who got which drug. But how do you know who quit smoking? Remember, everyone had a diagnosis code for tobacco use disorder prior to starting Ozempic or a comparator drug. The authors decided that if the patient had a medical visit where someone again coded tobacco-use disorder, they were still smoking. If someone prescribed smoking cessation meds like a nicotine patch or varenicline, they were obviously still smoking. If someone billed for tobacco-cessation counseling, the patient is still smoking. We’ll get back to the implications of this outcome definition in a minute.

Let’s talk about the results, which are pretty intriguing.

When Ozempic is compared with insulin among smokers with diabetes, those on Ozempic were about 30% more likely to quit smoking. They were about 18% more likely to quit smoking than those who took metformin. They were even slightly more likely to quit smoking than those on other GLP-1 receptor antagonists, though I should note that Mounjaro, which is probably the more potent GLP-1 drug in terms of weight loss, was not among the comparators.

This is pretty impressive for a drug that was not designed to be a smoking cessation drug. It speaks to this emerging idea that these drugs do more than curb appetite by slowing down gastric emptying or something. They work in the brain, modulating some of the reward circuitry that keeps us locked into our bad habits.

There are, of course, some caveats. As I pointed out, this study captured the idea of “still smoking” through the use of administrative codes in the EHR and prescription of smoking cessation aids. You could see similar results if taking Ozempic makes people less likely to address their smoking at all; maybe they shut down the doctor before they even talk about it, or there is too much to discuss during these visits to even get to the subject of smoking. You could also see results like this if people taking Ozempic had fewer visits overall, but the authors showed that that, at least, was not the case.

I’m inclined to believe that this effect is real, simply because we keep seeing signals from multiple sources. If that turns out to be the case, these new “weight loss” drugs may prove to be much more than that; they may turn out to be the drugs that can finally save us from ourselves.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If you’ve been paying attention only to the headlines, when you think of “Ozempic” you’ll think of a few things: a blockbuster weight loss drug or the tip of the spear of a completely new industry — why not? A drug so popular that the people it was invented for (those with diabetes) can’t even get it.

Ozempic and other GLP-1 receptor agonists are undeniable game changers. Insofar as obesity is the number-one public health risk in the United States, antiobesity drugs hold immense promise even if all they do is reduce obesity.

In 2023, an article in Scientific Reports presented data suggesting that people on Ozempic might be reducing their alcohol intake, not just their total calories.

A 2024 article in Molecular Psychiatry found that the drug might positively impact cannabis use disorder. An article from Brain Sciences suggests that the drug reduces compulsive shopping.

A picture is starting to form, a picture that suggests these drugs curb hunger both literally and figuratively. That GLP-1 receptor agonists like Ozempic and Mounjaro are fundamentally anticonsumption drugs. In a society that — some would argue — is plagued by overconsumption, these drugs might be just what the doctor ordered.

If only they could stop people from smoking.

Oh, wait — they can.

At least it seems they can, based on a new study appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Before we get too excited, this is not a randomized trial. There actually was a small randomized trial of exenatide (Byetta), which is in the same class as Ozempic but probably a bit less potent, with promising results for smoking cessation.

But Byetta is the weaker drug in this class; the market leader is Ozempic. So how can you figure out whether Ozempic can reduce smoking without doing a huge and expensive randomized trial? You can do what Nora Volkow and colleagues from the National Institute on Drug Abuse did: a target trial emulation study.

A target trial emulation study is more or less what it sounds like. First, you decide what your dream randomized controlled trial would be and you plan it all out in great detail. You define the population you would recruit, with all the relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria. You define the intervention and the control, and you define the outcome.

But you don’t actually do the trial. You could if someone would lend you $10-$50 million, but assuming you don’t have that lying around, you do the next best thing, which is to dig into a medical record database to find all the people who would be eligible for your imaginary trial. And you analyze them.

The authors wanted to study the effect of Ozempic on smoking among people with diabetes; that’s why all the comparator agents are antidiabetes drugs. They figured out whether these folks were smoking on the basis of a medical record diagnosis of tobacco use disorder before they started one of the drugs of interest. This code is fairly specific: If a patient has it, you can be pretty sure they are smoking. But it’s not very sensitive; not every smoker has this diagnostic code. This is an age-old limitation of using EHR data instead of asking patients, but it’s part of the tradeoff for not having to spend $50 million.

After applying all those inclusion and exclusion criteria, they have a defined population who could be in their dream trial. And, as luck would have it, some of those people really were treated with Ozempic and some really were treated with those other agents. Although decisions about what to prescribe were not randomized, the authors account for this confounding-by-indication using propensity-score matching. You can find a little explainer on propensity-score matching in an earlier column here.

It’s easy enough, using the EHR, to figure out who has diabetes and who got which drug. But how do you know who quit smoking? Remember, everyone had a diagnosis code for tobacco use disorder prior to starting Ozempic or a comparator drug. The authors decided that if the patient had a medical visit where someone again coded tobacco-use disorder, they were still smoking. If someone prescribed smoking cessation meds like a nicotine patch or varenicline, they were obviously still smoking. If someone billed for tobacco-cessation counseling, the patient is still smoking. We’ll get back to the implications of this outcome definition in a minute.

Let’s talk about the results, which are pretty intriguing.

When Ozempic is compared with insulin among smokers with diabetes, those on Ozempic were about 30% more likely to quit smoking. They were about 18% more likely to quit smoking than those who took metformin. They were even slightly more likely to quit smoking than those on other GLP-1 receptor antagonists, though I should note that Mounjaro, which is probably the more potent GLP-1 drug in terms of weight loss, was not among the comparators.

This is pretty impressive for a drug that was not designed to be a smoking cessation drug. It speaks to this emerging idea that these drugs do more than curb appetite by slowing down gastric emptying or something. They work in the brain, modulating some of the reward circuitry that keeps us locked into our bad habits.

There are, of course, some caveats. As I pointed out, this study captured the idea of “still smoking” through the use of administrative codes in the EHR and prescription of smoking cessation aids. You could see similar results if taking Ozempic makes people less likely to address their smoking at all; maybe they shut down the doctor before they even talk about it, or there is too much to discuss during these visits to even get to the subject of smoking. You could also see results like this if people taking Ozempic had fewer visits overall, but the authors showed that that, at least, was not the case.

I’m inclined to believe that this effect is real, simply because we keep seeing signals from multiple sources. If that turns out to be the case, these new “weight loss” drugs may prove to be much more than that; they may turn out to be the drugs that can finally save us from ourselves.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lancet Commission Aims for a Clearer Definition of Obesity

Although obesity affects more than 1 billion people worldwide, according to a global analysis published in The Lancet, it still lacks a clear “identity” in research, social perception, and the healthcare sector. This lack of clarity hinders accurate diagnoses and treatments, while also perpetuating stigma and prejudice. Specialists argue that obesity is a chronic disease rather than just a condition that leads to other diseases.

At the latest International Congress on Obesity held in São Paulo, Brazil from June 26 to 29, The Lancet Commission on the Definition and Diagnosis of Clinical Obesity announced that it is conducting a global study to create a clear definition for obesity. This condition is often wrongly associated solely with individual choices. Ricardo Cohen, MD, PhD, coordinator of the Obesity and Diabetes Specialized Center at the Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital, São Paulo, and a key researcher in the study, made the announcement. “The current definition of obesity is too broad and ineffective for our needs,” said Dr. Cohen.

Dr. Cohen highlighted several challenges stemming from the lack of a precise definition, including confusion between prevention and treatment strategies, inadequate access to evidence-based treatments, and misconceptions about obesity and its reversibility. He also pointed out the limited understanding of the metabolic and biological complexity of the disease. “Society is comfortable with the current scenario because people are commonly blamed for their obesity. This is evident in the acceptance of so-called ‘magic solutions,’ such as fad diets, and the idea that obesity is merely a result of overeating and underexercising,” he said, noting the mental health damage that this perception can cause.

The difficulty in defining obesity stems from its common classification as a risk factor rather than a disease, said Dr. Cohen. Obesity meets the criteria to be considered a disease, such as well-defined pathophysiologic and etiologic mechanisms. In this way, obesity resembles diabetes and depressive disorders, which are classified as diseases based on the same criteria. This inconsistency, maintained by societal perceptions and the healthcare sector, creates confusion. Many professionals still lack a clear understanding of obesity as a disease.

This confusion perpetuates stigma and ignores the unique metabolic function in individuals. As a result, treatments often focus on preventing secondary diseases like diabetes and hypertension rather than on addressing obesity itself. Dr. Cohen recounted the case of a patient with fatigue, knee pain, and osteolysis who couldn’t perform daily activities but did not receive the necessary care. “If he had diabetes, he could have access to treatment because diabetes is recognized as a disease and needs to be treated. But since obesity is not recognized as such, he was sent home.”

To address these challenges, The Lancet Commission’s study, which is expected to be published this year, aims to establish clear diagnostic criteria for adults and children. Drawing inspiration from medical disciplines with well-established diagnostic criteria, such as rheumatology and psychiatry, the research has defined 18 criteria for adults and 14 for children.

The study also redefines treatment outcomes, sets standards for clinical remission of obesity, and proposes clear recommendations for clinical practice and public health policies. The ultimate goal, according to Dr. Cohen, is to transform the global treatment spectrum of obesity and improve access to necessary care.

“Our plan is to recognize obesity as a disease so that health policies, societal attitudes, and treatments will address it more effectively. This approach will also help reduce the harm caused by stigma and prejudice,” concluded Dr. Cohen.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although obesity affects more than 1 billion people worldwide, according to a global analysis published in The Lancet, it still lacks a clear “identity” in research, social perception, and the healthcare sector. This lack of clarity hinders accurate diagnoses and treatments, while also perpetuating stigma and prejudice. Specialists argue that obesity is a chronic disease rather than just a condition that leads to other diseases.

At the latest International Congress on Obesity held in São Paulo, Brazil from June 26 to 29, The Lancet Commission on the Definition and Diagnosis of Clinical Obesity announced that it is conducting a global study to create a clear definition for obesity. This condition is often wrongly associated solely with individual choices. Ricardo Cohen, MD, PhD, coordinator of the Obesity and Diabetes Specialized Center at the Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital, São Paulo, and a key researcher in the study, made the announcement. “The current definition of obesity is too broad and ineffective for our needs,” said Dr. Cohen.

Dr. Cohen highlighted several challenges stemming from the lack of a precise definition, including confusion between prevention and treatment strategies, inadequate access to evidence-based treatments, and misconceptions about obesity and its reversibility. He also pointed out the limited understanding of the metabolic and biological complexity of the disease. “Society is comfortable with the current scenario because people are commonly blamed for their obesity. This is evident in the acceptance of so-called ‘magic solutions,’ such as fad diets, and the idea that obesity is merely a result of overeating and underexercising,” he said, noting the mental health damage that this perception can cause.

The difficulty in defining obesity stems from its common classification as a risk factor rather than a disease, said Dr. Cohen. Obesity meets the criteria to be considered a disease, such as well-defined pathophysiologic and etiologic mechanisms. In this way, obesity resembles diabetes and depressive disorders, which are classified as diseases based on the same criteria. This inconsistency, maintained by societal perceptions and the healthcare sector, creates confusion. Many professionals still lack a clear understanding of obesity as a disease.

This confusion perpetuates stigma and ignores the unique metabolic function in individuals. As a result, treatments often focus on preventing secondary diseases like diabetes and hypertension rather than on addressing obesity itself. Dr. Cohen recounted the case of a patient with fatigue, knee pain, and osteolysis who couldn’t perform daily activities but did not receive the necessary care. “If he had diabetes, he could have access to treatment because diabetes is recognized as a disease and needs to be treated. But since obesity is not recognized as such, he was sent home.”

To address these challenges, The Lancet Commission’s study, which is expected to be published this year, aims to establish clear diagnostic criteria for adults and children. Drawing inspiration from medical disciplines with well-established diagnostic criteria, such as rheumatology and psychiatry, the research has defined 18 criteria for adults and 14 for children.

The study also redefines treatment outcomes, sets standards for clinical remission of obesity, and proposes clear recommendations for clinical practice and public health policies. The ultimate goal, according to Dr. Cohen, is to transform the global treatment spectrum of obesity and improve access to necessary care.

“Our plan is to recognize obesity as a disease so that health policies, societal attitudes, and treatments will address it more effectively. This approach will also help reduce the harm caused by stigma and prejudice,” concluded Dr. Cohen.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although obesity affects more than 1 billion people worldwide, according to a global analysis published in The Lancet, it still lacks a clear “identity” in research, social perception, and the healthcare sector. This lack of clarity hinders accurate diagnoses and treatments, while also perpetuating stigma and prejudice. Specialists argue that obesity is a chronic disease rather than just a condition that leads to other diseases.

At the latest International Congress on Obesity held in São Paulo, Brazil from June 26 to 29, The Lancet Commission on the Definition and Diagnosis of Clinical Obesity announced that it is conducting a global study to create a clear definition for obesity. This condition is often wrongly associated solely with individual choices. Ricardo Cohen, MD, PhD, coordinator of the Obesity and Diabetes Specialized Center at the Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital, São Paulo, and a key researcher in the study, made the announcement. “The current definition of obesity is too broad and ineffective for our needs,” said Dr. Cohen.

Dr. Cohen highlighted several challenges stemming from the lack of a precise definition, including confusion between prevention and treatment strategies, inadequate access to evidence-based treatments, and misconceptions about obesity and its reversibility. He also pointed out the limited understanding of the metabolic and biological complexity of the disease. “Society is comfortable with the current scenario because people are commonly blamed for their obesity. This is evident in the acceptance of so-called ‘magic solutions,’ such as fad diets, and the idea that obesity is merely a result of overeating and underexercising,” he said, noting the mental health damage that this perception can cause.

The difficulty in defining obesity stems from its common classification as a risk factor rather than a disease, said Dr. Cohen. Obesity meets the criteria to be considered a disease, such as well-defined pathophysiologic and etiologic mechanisms. In this way, obesity resembles diabetes and depressive disorders, which are classified as diseases based on the same criteria. This inconsistency, maintained by societal perceptions and the healthcare sector, creates confusion. Many professionals still lack a clear understanding of obesity as a disease.

This confusion perpetuates stigma and ignores the unique metabolic function in individuals. As a result, treatments often focus on preventing secondary diseases like diabetes and hypertension rather than on addressing obesity itself. Dr. Cohen recounted the case of a patient with fatigue, knee pain, and osteolysis who couldn’t perform daily activities but did not receive the necessary care. “If he had diabetes, he could have access to treatment because diabetes is recognized as a disease and needs to be treated. But since obesity is not recognized as such, he was sent home.”

To address these challenges, The Lancet Commission’s study, which is expected to be published this year, aims to establish clear diagnostic criteria for adults and children. Drawing inspiration from medical disciplines with well-established diagnostic criteria, such as rheumatology and psychiatry, the research has defined 18 criteria for adults and 14 for children.

The study also redefines treatment outcomes, sets standards for clinical remission of obesity, and proposes clear recommendations for clinical practice and public health policies. The ultimate goal, according to Dr. Cohen, is to transform the global treatment spectrum of obesity and improve access to necessary care.

“Our plan is to recognize obesity as a disease so that health policies, societal attitudes, and treatments will address it more effectively. This approach will also help reduce the harm caused by stigma and prejudice,” concluded Dr. Cohen.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lipedema: Current Diagnostic and Treatment Evidence

Lipedema affects about 11% of cisgender women, according to the Brazilian Society of Angiology and Vascular Surgery. Yet the condition remains wrapped in uncertainties. Despite significant advancements in understanding its physiology, diagnosis, and treatment, more clarity is needed as awareness and diagnoses increase.

At the latest International Congress on Obesity (ICO) in São Paulo, Brazil, Philipp Scherer, PhD, director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center, discussed the complexities of lipedema. “It is an extremely frustrating condition for someone like me, who has spent a lifetime studying functional and dysfunctional adipose tissue. We are trying to understand the physiology of this pathology, but it is challenging, and so far, we have not been able to find a concrete answer,” he noted.

Lipedema is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of subcutaneous adipose tissue, especially in the lower limbs, and almost exclusively affects cisgender women. The reason for this gender disparity is unclear. It could be an intrinsic characteristic of the disease or a result from clinicians’ lack of familiarity with lipedema, which often leads to misdiagnosis as obesity. This misdiagnosis results in fewer men seeking treatment.

Research has predominantly focused on women, and evidence suggests that hormones play a crucial role in the disease’s pathophysiology. Lipedema typically manifests during periods of hormonal changes, such as puberty, pregnancy, menopause, and hormone replacement therapies, reinforcing the idea that hormones significantly influence the condition’s development and progression.

Main Symptoms

Jonathan Kartt, CEO of the Lipedema Foundation, emphasized that intense pain in the areas of adipose tissue accumulation is a hallmark symptom of lipedema, setting it apart from obesity. Pain levels can vary widely among patients, ranging from moderate to severe, with unbearable peaks on certain days. Mr. Kartt stressed the importance of recognizing and addressing this often underestimated symptom.

Lipedema is characterized by a bilateral, symmetrical increase in mass compared with the rest of the body. This is commonly distinguished by the “cuff sign,” a separation between normal tissue in the feet and abnormal tissue from the ankle upward. Other frequent symptoms include a feeling of heaviness, discomfort, fatigue, frequent bruising, and tiredness. A notable sign is the presence of subcutaneous nodules with a texture similar to that of rice grains, which are crucial for differentiating lipedema from other conditions. Palpation during anamnesis is essential to identify these nodules and confirm the diagnosis.

“It is crucial to investigate the family history for genetic predisposition. Additionally, it is fundamental to ask whether, even with weight loss, the affected areas retain accumulated fat. Hormonal changes, pain symptoms, and impact on quality of life should also be carefully evaluated,” advised Mr. Kartt.

Diagnostic Tools

André Murad, MD, a clinical consultant at the Instituto Lipedema Brazil, has been exploring new diagnostic approaches for lipedema beyond traditional anamnesis. During his presentation at the ICO, he shared studies on the efficacy of imaging exams such as ultrasound, tomography, and MRI in diagnosing the characteristic lipedema-associated increase in subcutaneous tissue.

He also discussed lymphangiography and lymphoscintigraphy, highlighting the use of magnetic resonance lymphangiography to evaluate dilated lymphatic vessels often observed in patients with lipedema. “By injecting contrast into the feet, this technique allows the evaluation of vessels, which are usually dilated, indicating characteristic lymphatic system overload in lipedema. Lymphoscintigraphy is crucial for detecting associated lymphedema, revealing delayed lymphatic flow and asymmetry between limbs in cases of lipedema without lymphedema,” he explained.

Despite the various diagnostic options, Dr. Murad highlighted two highly effective studies. A Brazilian study used ultrasound to establish a cutoff point of 11.7 mm in the pretibial subcutaneous tissue thickness, achieving 96% specificity for diagnosis. Another study emphasized the value of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which demonstrated 95% sensitivity. This method assesses fat distribution by correlating the amount present in the legs with the total body, providing a cost-effective and accessible option for specialists.

“DXA allows for a precise mathematical evaluation of fat distribution relative to the total body. A ratio of 0.38 in the leg-to-body relationship is a significant indicator of high suspicion of lipedema,” highlighted Dr. Murad. “In clinical practice, many patients self-diagnose with lipedema, but the clinical exam often reveals no disproportion, with the leg-to-body ratio below 0.38 being common in these cases,” he added.

Treatment Approaches

Treatments for lipedema are still evolving, with considerable debate about the best approach. While some specialists advocate exclusively for conservative treatment, others recommend combining these methods with surgical interventions, depending on the stage of the disease. The relative novelty of lipedema and the scarcity of robust, long-term studies contribute to the uncertainty around treatment efficacy.

Conservative treatment typically includes compression, lymphatic drainage techniques, and pressure therapy. An active lifestyle and a healthy diet are also recommended. Although these measures do not prevent the accumulation of adipose tissue, they help reduce inflammation and improve quality of life. “Even though the causes of lipedema are not fully known, lifestyle management is essential for controlling symptoms, starting with an anti-inflammatory diet,” emphasized Dr. Murad.

Because insulin promotes lipogenesis, a diet that avoids spikes in glycemic and insulin levels is advisable. Insulin resistance can exacerbate edema formation, so a Mediterranean diet may be beneficial. This diet limits fast-absorbing carbohydrates, such as added sugar, refined grains, and ultraprocessed foods, while promoting complex carbohydrates from whole grains and legumes.

Dr. Murad also presented a study evaluating the potential benefits of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet for patients with lipedema. The study demonstrated weight loss, reduced body fat, controlled leg volume, and, notably, pain relief.

For more advanced stages of lipedema, plastic surgery is often considered when conservative approaches do not yield satisfactory results. Some specialists advocate for surgery as an effective way to remove diseased adipose cells and reduce excess fat accumulation, which can improve physical appearance and associated pain. There is a growing consensus that surgical intervention should be performed early, ideally in stage I of IV, to maximize efficacy and prevent disease progression.

Fábio Masato Kamamoto, MD, a plastic surgeon and director of the Instituto Lipedema Brazil, shared insights into surgical treatments for lipedema. He discussed techniques from liposuction to advanced skin retraction and dermolipectomy, crucial for addressing more advanced stages of the condition. “It’s a complex process that demands precision to protect the lymphatic system, especially considering the characteristic nodules of lipedema,” he noted.

Dr. Kamamoto discussed a former patient with stage III lipedema. In the initial stage, he performed liposuction, removing 8 L of fat and 3.4 kg of skin. After 6 months, a follow-up procedure resulted in a total removal of 15 kg. Complementary procedures, such as microneedling, were performed to stimulate collagen production and reduce skin sagging. In addition to cosmetic improvements, the procedure also removed the distinctive lipedema nodules, which Mr. Kartt described as feeling like “rice grains.” Removing these nodules significantly alleviates pain, according to Dr. Kamamoto.

The benefits of surgical treatment for lipedema can be long lasting. Dr. Kamamoto noted that fat tends not to reaccumulate in treated areas, with patients often experiencing lower weight, reduced edema, and decreased pain over time. “While we hope that patients do not regain weight, the benefits of surgery persist even if weight is regained. Therefore, combining conservative and surgical treatments remains a valid and effective approach,” he concluded.

Dr. Scherer highlighted that despite various approaches, there is still no definitive “magic signature” that fully explains lipedema. This lack of clarity directly affects the effectiveness of diagnoses and treatments. He expressed hope that future integration of data from different studies and approaches will lead to the identification of a clinically useful molecular signature. “The true cause of lipedema remains unknown, requiring more speculation, hypothesis formulation, and testing for significant discoveries. This situation is frustrating, as the disease affects many women who lack a clear diagnosis that differentiates them from patients with obesity, as well as evidence-based recommendations,” he concluded.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lipedema affects about 11% of cisgender women, according to the Brazilian Society of Angiology and Vascular Surgery. Yet the condition remains wrapped in uncertainties. Despite significant advancements in understanding its physiology, diagnosis, and treatment, more clarity is needed as awareness and diagnoses increase.

At the latest International Congress on Obesity (ICO) in São Paulo, Brazil, Philipp Scherer, PhD, director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center, discussed the complexities of lipedema. “It is an extremely frustrating condition for someone like me, who has spent a lifetime studying functional and dysfunctional adipose tissue. We are trying to understand the physiology of this pathology, but it is challenging, and so far, we have not been able to find a concrete answer,” he noted.

Lipedema is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of subcutaneous adipose tissue, especially in the lower limbs, and almost exclusively affects cisgender women. The reason for this gender disparity is unclear. It could be an intrinsic characteristic of the disease or a result from clinicians’ lack of familiarity with lipedema, which often leads to misdiagnosis as obesity. This misdiagnosis results in fewer men seeking treatment.

Research has predominantly focused on women, and evidence suggests that hormones play a crucial role in the disease’s pathophysiology. Lipedema typically manifests during periods of hormonal changes, such as puberty, pregnancy, menopause, and hormone replacement therapies, reinforcing the idea that hormones significantly influence the condition’s development and progression.

Main Symptoms

Jonathan Kartt, CEO of the Lipedema Foundation, emphasized that intense pain in the areas of adipose tissue accumulation is a hallmark symptom of lipedema, setting it apart from obesity. Pain levels can vary widely among patients, ranging from moderate to severe, with unbearable peaks on certain days. Mr. Kartt stressed the importance of recognizing and addressing this often underestimated symptom.

Lipedema is characterized by a bilateral, symmetrical increase in mass compared with the rest of the body. This is commonly distinguished by the “cuff sign,” a separation between normal tissue in the feet and abnormal tissue from the ankle upward. Other frequent symptoms include a feeling of heaviness, discomfort, fatigue, frequent bruising, and tiredness. A notable sign is the presence of subcutaneous nodules with a texture similar to that of rice grains, which are crucial for differentiating lipedema from other conditions. Palpation during anamnesis is essential to identify these nodules and confirm the diagnosis.

“It is crucial to investigate the family history for genetic predisposition. Additionally, it is fundamental to ask whether, even with weight loss, the affected areas retain accumulated fat. Hormonal changes, pain symptoms, and impact on quality of life should also be carefully evaluated,” advised Mr. Kartt.

Diagnostic Tools

André Murad, MD, a clinical consultant at the Instituto Lipedema Brazil, has been exploring new diagnostic approaches for lipedema beyond traditional anamnesis. During his presentation at the ICO, he shared studies on the efficacy of imaging exams such as ultrasound, tomography, and MRI in diagnosing the characteristic lipedema-associated increase in subcutaneous tissue.

He also discussed lymphangiography and lymphoscintigraphy, highlighting the use of magnetic resonance lymphangiography to evaluate dilated lymphatic vessels often observed in patients with lipedema. “By injecting contrast into the feet, this technique allows the evaluation of vessels, which are usually dilated, indicating characteristic lymphatic system overload in lipedema. Lymphoscintigraphy is crucial for detecting associated lymphedema, revealing delayed lymphatic flow and asymmetry between limbs in cases of lipedema without lymphedema,” he explained.

Despite the various diagnostic options, Dr. Murad highlighted two highly effective studies. A Brazilian study used ultrasound to establish a cutoff point of 11.7 mm in the pretibial subcutaneous tissue thickness, achieving 96% specificity for diagnosis. Another study emphasized the value of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which demonstrated 95% sensitivity. This method assesses fat distribution by correlating the amount present in the legs with the total body, providing a cost-effective and accessible option for specialists.

“DXA allows for a precise mathematical evaluation of fat distribution relative to the total body. A ratio of 0.38 in the leg-to-body relationship is a significant indicator of high suspicion of lipedema,” highlighted Dr. Murad. “In clinical practice, many patients self-diagnose with lipedema, but the clinical exam often reveals no disproportion, with the leg-to-body ratio below 0.38 being common in these cases,” he added.

Treatment Approaches

Treatments for lipedema are still evolving, with considerable debate about the best approach. While some specialists advocate exclusively for conservative treatment, others recommend combining these methods with surgical interventions, depending on the stage of the disease. The relative novelty of lipedema and the scarcity of robust, long-term studies contribute to the uncertainty around treatment efficacy.

Conservative treatment typically includes compression, lymphatic drainage techniques, and pressure therapy. An active lifestyle and a healthy diet are also recommended. Although these measures do not prevent the accumulation of adipose tissue, they help reduce inflammation and improve quality of life. “Even though the causes of lipedema are not fully known, lifestyle management is essential for controlling symptoms, starting with an anti-inflammatory diet,” emphasized Dr. Murad.

Because insulin promotes lipogenesis, a diet that avoids spikes in glycemic and insulin levels is advisable. Insulin resistance can exacerbate edema formation, so a Mediterranean diet may be beneficial. This diet limits fast-absorbing carbohydrates, such as added sugar, refined grains, and ultraprocessed foods, while promoting complex carbohydrates from whole grains and legumes.

Dr. Murad also presented a study evaluating the potential benefits of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet for patients with lipedema. The study demonstrated weight loss, reduced body fat, controlled leg volume, and, notably, pain relief.

For more advanced stages of lipedema, plastic surgery is often considered when conservative approaches do not yield satisfactory results. Some specialists advocate for surgery as an effective way to remove diseased adipose cells and reduce excess fat accumulation, which can improve physical appearance and associated pain. There is a growing consensus that surgical intervention should be performed early, ideally in stage I of IV, to maximize efficacy and prevent disease progression.