User login

Medical Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: Early Diagnosis is Key

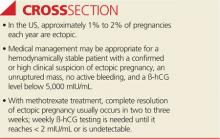

Ectopic pregnancy is a significant health risk to women during their childbearing years; approximately 6% of all pregnancy-related deaths are due to ectopic pregnancy.1-3 Some 1% to 2% of all pregnancies in the United States each year—approximately 100,000 cases—are ectopic, with an estimated annual cost of care approaching $1.1 billion.4 The incidence of ectopic pregnancy has increased in the past 20 years; in one analysis, ectopic pregnancy was diagnosed in 18% of women who presented to an emergency department (ED) with first trimester vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, or both.5 This growing prevalence is attributed to a number of factors, including the sensitivity of current diagnostic methods in detecting early ectopic pregnancy, the greater incidence of salpingitis, and the growing use of assisted reproductive technologies.2,6

While the number of ectopic pregnancies is on the rise, the proportion of patients requiring hospitalization for surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy has decreased significantly. Today, for appropriate patients, many clinicians manage ectopic pregnancy on an outpatient basis using the drug methotrexate.6

In this article, we will present an overview of the current status of medical management of ectopic pregnancy, along with a case study. The case study describes a patient diagnosed with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy who was managed medically with methotrexate. It illustrates how, with early diagnosis, clinicians can intervene to make medical management an effective treatment option in selected situations.

The patient reported a history of oral contraceptive use until approximately three months prior to this pregnancy. She was taking no medications and had no known drug allergies. Her previous pregnancies included two uncomplicated vaginal births at term and one miscarriage at six to seven weeks’ gestation two years ago. She also reported a dilation and curettage after the miscarriage. Her medical, surgical, and gynecologic histories were otherwise noncontributory. A review of systems was otherwise negative.

Sexual history revealed that the patient was married and monogamous with her husband of five years. She disclosed four previous sexual partners and inconsistent use of condoms with those partners; no current condom use was reported. Seven years ago, she tested positive for gonorrhea and chlamydia and was treated concurrently with her partner. Subsequent diagnostics were negative. She reported vaginal intercourse but no oral sex and denied any other sexual contact. All partners had been male.

On the next page: Diagnosis and case continuation >>

DIAGNOSIS

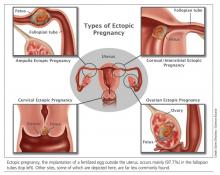

There is some variation in the presentation of women experiencing ectopic pregnancy; this may be due to differences in the pathologic mechanisms of ectopic pregnancy. Patients may be asymptomatic, hemodynamically compromised, or somewhere in between.3 Typical clinical signs include abdominal pain, amenorrhea, and vaginal bleeding. Approximately 40% to 50% of patients present with vaginal bleeding, 50% may have a palpable adnexal mass, and 75% may have abdominal tenderness.3 Only about 50% of women with ectopic pregnancies present with these typical symptoms.3

The patient may also experience common symptoms of early pregnancy, such as nausea, fatigue, and breast fullness. Worrisome signs and symptoms, including abdominal guarding, hypotension, tachycardia, shock, shoulder pain from peritoneal irritation, dizziness, fever, and vomiting, may also be present.3,7 Approximately 20% of patients with ectopic pregnancies are hemodynamically compromised at presentation, which is highly suggestive of rupture.3

Risk factors

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include previous ectopic pregnancy; previous tubal procedures; history of sexually transmitted disease or genital infections; infertility; use of assisted reproductive technology; previous abdominal or pelvic surgery; smoking; pelvic inflammatory disease; exposure in utero to diethylstilbestrol; and previous intrauterine device use.2,5,7,8 Knowledge of these risk factors can help identify a patient with an ectopic pregnancy.

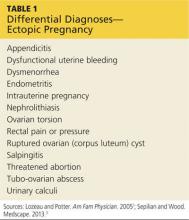

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is most certainly a clinical challenge. The differential diagnosis is based upon history and physical findings; the list can be lengthy if both vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain (nonspecific symptoms common in women who miscarry) are present.7 Prompt completion of diagnostic testing is critical in making a definitive diagnosis. Possible diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

CASE Upon examination, the patient appeared comfortable and relaxed, and there were no signs of distress. Blood pressure was 100/65 mm Hg, pulse rate was 72 beats/min, and temperature was 99.0°F. There was no tenderness upon abdominal examination. Pelvic examination revealed a small amount of brown vaginal discharge but no active bleeding or pooled blood, clots, or tissue. The cervical os was closed, and positive Chadwick sign was present. Bimanual examination revealed no cervical motion tenderness. The uterus was soft, mobile, and nontender, and consistent in size with a gestation at eight weeks. There were no palpable adnexa, ovaries, or masses. There was no pain with bimanual examination and no evidence of tenderness at the posterior fornix. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

It is important to note that examination results in the case patient are not unusual in a woman with a small, unruptured ectopic pregnancy. All findings were normal except for the scant brown vaginal discharge. Abdominal and adnexal tenderness are common, as is a palpable adnexal mass; but absence of a detectable mass does not exclude ectopic pregnancy.1 Pathologic findings may include severe abdominal tenderness and pain, significant vaginal bleeding, passage of clots, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension.

Diagnostic workup

Laboratory tests are critical to making an accurate diagnosis for women whose history and physical examination results are consistent with ectopic pregnancy. Assessment for ectopic pregnancy should include a urine pregnancy test, transvaginal ultrasound, measurement of serum ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) level, and occasionally, diagnostic curettage.1 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, a complete blood count (CBC) is necessary to assess anemia and platelet functioning. Coagulation tests may be required for worrisome bleeding. Blood type, Rh status, and antibody screen are also necessary to determine whether a patient who is Rh D-negative will require Rh immune globulin. See Table 2 for the patient’s laboratory test results.

In a patient with a ß-hCG level greater than the discriminatory cutoff value of 1,500 to 1,800 mIU/mL, the level above which an intrauterine gestational sac is visible on transvaginal ultrasound in a normal pregnancy, an empty uterus is considered an ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise.3 In a definite intrauterine pregnancy of about six weeks’ gestation, transvaginal ultrasound reveals a gestational sac that contains a yolk sac and a fetal pole.3

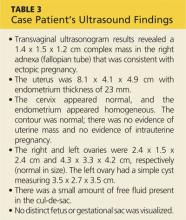

CASE The patient’s presenting symptoms, combined with a positive pregnancy test, ß-hCG level of 1,850 mIU/mL, and a complex adnexal mass in the right fallopian tube, were highly suggestive of an unruptured ectopic pregnancy (see Table 3 for the patient’s transvaginal ultrasound findings). There was also a secondary finding of a corpus luteum cyst. Other diagnoses were ruled out, and the patient was diagnosed with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

A patient with an ectopic pregnancy who presents with pain and hemodynamic instability should be referred immediately for appropriate surgical care.7 Otherwise, once the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is confirmed, the patient should be referred to an obstetric specialist. Treatments for ectopic pregnancy include expectant management and surgery—which will be discussed briefly—and medical management, which is the focus of this review.5

Expectant management

Most ectopic pregnancies are diagnosed early as a result of accurate, minimally invasive and noninvasive diagnostic tools and greater awareness of risk factors. Since the natural course of early ectopic pregnancy is often self-limited, eventually resulting in tubal abortion or reabsorption, expectant management is a viable option.9

This treatment option may be considered if the patient is asymptomatic; ß-hCG is < 200 mIU/mL; the ectopic mass is < 3 cm; and no fetal heartbeat is present.1,2 With this approach, patients must be willing to accept the risk for tubal rupture and agree to close monitoring of ß-hCG levels. The ß-hCG level must be measured every 24 to 48 hours in order to determine if it is declining adequately, plateauing, or increasing.2,5

Surgery

For the hemodynamically unstable patient, the treatment decision is relatively straightforward. Optimal treatment for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is immediate surgery, which may include salpingostomy or salpingectomy.10 Surgery may also be considered for hemodynamically stable patients with nonruptured ectopic pregnancies; in addition to her clinical presentation, overall management may be driven by a patient’s preferences.5 Salpingostomy and salpingectomy can be performed either laparoscopically or via laparotomy, depending on the specific situation.

Medical management

The use of methotrexate for the management of unruptured ectopic pregnancy was introduced in the early 1980s.11 Initially, protocols called for multiple doses administered during the course of an inpatient stay. Further research led to revised treatment recommendations and today, medical management most often consists of a single dose of methotrexate with outpatient follow-up.3

Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist often used as an antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent. In ectopic pregnancy, it inhibits growth of the rapidly dividing trophoblastic cells and ultimately ends the pregnancy.2 Outcomes of medical management are comparable to those of surgical treatment, including the potential for future normal pregnancies.2,5

An analysis of US trends in ectopic pregnancy management from 2002-2007 revealed that the use of methotrexate increased from 11.1% to 35.1% during that time, while the use of surgical approaches declined from 90% to 65%.10 Medical management of ectopic pregnancy eliminates the costs of surgery, anesthesia, and hospitalization and avoids potential complications of surgery and anesthesia.

Appropriate candidates

A hemodynamically stable patient with a confirmed or high clinical suspicion of ectopic pregnancy, an unruptured mass, no active bleeding, and low ß-hCG levels (< 5,000 mIU/mL) can be considered for methotrexate therapy.2,3,9 It is critical that medically managed patients be willing and able to adhere to all follow-up appointments.9 Before initiating treatment, normal serum creatinine and transaminase levels should be confirmed, and there should be no evidence of significant anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia.2 To detect any adverse effects of methotrexate on renal, hepatic, and hematologic functioning, these tests are repeated one week after administration.2

Contraindications

Contraindications to methotrexate treatment include breastfeeding, immunodeficiency, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease or other chronic liver disease, preexisting blood dyscrasias (eg, bone marrow hypoplasia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or significant anemia), known sensitivity to methotrexate, active pulmonary disease, peptic ulcer, and hepatic, renal, or hematologic dysfunction. Relative contraindications are a gestational sac larger than 3.5 cm and embryonic cardiac motion.2

On the next page: Patient education >>

PATIENT EDUCATION AND INFORMED CONSENT

A diagnosis of unruptured ectopic pregnancy requires patient education about the condition and its treatment options. The clinician should explain what an ectopic pregnancy is and distinguish between unruptured and ruptured. A discussion of the benefits and risks of each treatment option for which the patient is an appropriate candidate, as well as what to anticipate during treatment, is needed. Emotional support for impending pregnancy loss should also be provided.

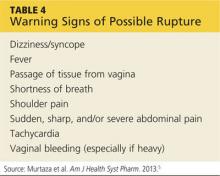

For patients who choose medical management, education includes methotrexate-specific information and written instructions to follow after methotrexate administration. Patients must be instructed about the use of safety precautions after treatment (eg, the toilet should be double-flushed with the lid closed during the first 72 hours after treatment to prevent exposing others to methotrexate in urine and stool), the need for adherence to follow-up visits, and warning signs of a possible rupture.5 These warning signs are listed in Table 4.

The most common adverse effects of methotrexate are gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, stomatitis). Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol, NSAIDs, folic acid supplements, excessive sun exposure (due to photosensitivity), strenuous exercise, and sexual intercourse until ß-hCG has returned to nonpregnant levels. Other adverse effects may include a temporary elevation in liver enzymes and rarely, alopecia. Abdominal pain may occur a few days after methotrexate administration, likely from the cytotoxic effects of the drug on the trophoblastic tissue.

Informed consent is required prior to methotrexate administration. The patient must be advised of the potential risks of medical management with methotrexate, including rupture of the ectopic pregnancy during treatment, inadvertent administration of methotrexate in the presence of an early intrauterine embryo, allergic reaction to methotrexate, and methotrexate-induced pneumonitis.5

CASE After lengthy discussion of the treatment options, the patient chose medical management with methotrexate. She verbalized her understanding of the teaching provided and signed an informed consent document.

METHOTREXATE REGIMENS

Protocols for single-dose, two-dose, and fixed multidose methotrexate regimens are described in the medical literature, according to a 2008 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin.2 A 2013 practice committee opinion of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) indicates that single-dose and multiple-dose regimens are used most often.12

With methotrexate treatment, complete resolution of ectopic pregnancy usually occurs in two to three weeks but may require up to six to eight weeks, depending on how high the ß-hCG level is when treatment begins.12

Single-dose

In the single-dose regimen, an intramuscular (IM) injection of methotrexate 50 mg/m2 is administered on day 1. The ß-hCG levels are measured on days 4 and 7 after administration; a decrease of at least 15% in the ß-hCG level should be observed. The ß-hCG level is then measured weekly until it reaches < 2 mIU/mL or is undetectable.2 If the level does not decline, a repeat dose of methotrexate can be given, with measurement of ß-hCG on days 4 and 7 after the repeat dose. If the ß-hCG level fails to decrease, additional methotrexate or surgical intervention should be considered.

The single-dose regimen is more frequently used and is most successful when ß-hCG levels are low (< 5,000 mIU/mL), the ectopic mass is small

(< 3.5 cm), and embryonic cardiac activity is not observed on ultrasound.2,3 Patients with ß-hCG levels > 5,000 mIU/mL may be appropriate candidates for additional doses of methotrexate.2 In fact, the single-dose protocol provides for repeat doses of methotrexate if the ß-hCG level is not decreasing adequately.12

Multiple-dose

With the multiple-dose regimen, methotrexate 1 mg/kg IM is administered on days 1, 3, 5, and 7; on days 2, 4, 6, and 8, the patient receives leucovorin (folinic acid) 0.1 mg/kg IM. The ß-hCG level is measured on days methotrexate is administered; once the minimum 15% decline is observed, ß-hCG is measured weekly until a nonpregnant level is reached.12

The patient received a single dose of methotrexate 50 mg/m2 IM on day 1 and returned to the clinic for follow-up on days 4 and 7 posttreatment. On day 4, her ß-hCG level was 1,060 mIU/mL; on day 7, it was 470 mIU/mL. Also on day 7, blood was drawn for a CBC and comprehensive metabolic panel; results were within normal limits. The patient continued weekly follow-up until her ß-hCG level decreased to < 2 mIU/mL.

On the next page: Follow-up and conclusion >>

FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRALS

Close monitoring of ß-hCG levels, as described previously, is essential after methotrexate treatment in order to confirm that the pregnancy has been terminated and reduce the risk for tubal rupture. Clinicians should also be sensitive to the sequelae of loss of a pregnancy and refer patients as needed to appropriate health care professionals for grief support.

CASE The patient was referred to an obstetrics clinic and reported for all scheduled follow-up appointments. She was discharged from care after a full reduction in her ß-hCG to nonpregnant levels. While at the clinic, the patient was referred to social services for psychosocial counseling.

CONCLUSION

Ectopic implantation is a serious complication that may occur during the first trimester of pregnancy. Worldwide, it is the leading cause of maternal death in the first trimester. For women who meet specific criteria, outpatient treatment of early ectopic pregnancy with methotrexate avoids surgery and decreases the overall cost of care. Medical management and conservative surgical management offer the patient comparable outcomes for tubal patency preservation and risk for ectopic pregnancy recurrence.11

REFERENCES

1. Lozeau AM, Potter B. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(9):1707-1714.

2. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 94: medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1479-1485.

3. Sepilian VP, Wood E. Ectopic pregnancy. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2041923-overview. Medscape. Accessed June 19, 2014.

4. Stein JC, Wang R, Adler N, et al. Emergency physician ultrasonography for evaluating patients at risk for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):674-683.

5. Murtaza UI, Ortmann MJ, Mando-Vandrick J, Lee ASD. Management of first-trimester complications in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(2):99-111.

6. Sewell CA, Cundiff GW. Trends for inpatient treatment of tubal pregnancy in Maryland. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):404-408.

7. Nama V, Manyonda I. Tubal ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(4):443-453.

8. Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Gracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic first-trimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(1):36-43.

9. Hajenius PJ, Mol F, Mol BW, et al. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD000324.

10. Hoover KW, Tao G, Kent CK. Trends in the diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3): 495-502.

11. Autry A. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy: is there something new? Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):733.

12. The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):638-644.

Ectopic pregnancy is a significant health risk to women during their childbearing years; approximately 6% of all pregnancy-related deaths are due to ectopic pregnancy.1-3 Some 1% to 2% of all pregnancies in the United States each year—approximately 100,000 cases—are ectopic, with an estimated annual cost of care approaching $1.1 billion.4 The incidence of ectopic pregnancy has increased in the past 20 years; in one analysis, ectopic pregnancy was diagnosed in 18% of women who presented to an emergency department (ED) with first trimester vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, or both.5 This growing prevalence is attributed to a number of factors, including the sensitivity of current diagnostic methods in detecting early ectopic pregnancy, the greater incidence of salpingitis, and the growing use of assisted reproductive technologies.2,6

While the number of ectopic pregnancies is on the rise, the proportion of patients requiring hospitalization for surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy has decreased significantly. Today, for appropriate patients, many clinicians manage ectopic pregnancy on an outpatient basis using the drug methotrexate.6

In this article, we will present an overview of the current status of medical management of ectopic pregnancy, along with a case study. The case study describes a patient diagnosed with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy who was managed medically with methotrexate. It illustrates how, with early diagnosis, clinicians can intervene to make medical management an effective treatment option in selected situations.

The patient reported a history of oral contraceptive use until approximately three months prior to this pregnancy. She was taking no medications and had no known drug allergies. Her previous pregnancies included two uncomplicated vaginal births at term and one miscarriage at six to seven weeks’ gestation two years ago. She also reported a dilation and curettage after the miscarriage. Her medical, surgical, and gynecologic histories were otherwise noncontributory. A review of systems was otherwise negative.

Sexual history revealed that the patient was married and monogamous with her husband of five years. She disclosed four previous sexual partners and inconsistent use of condoms with those partners; no current condom use was reported. Seven years ago, she tested positive for gonorrhea and chlamydia and was treated concurrently with her partner. Subsequent diagnostics were negative. She reported vaginal intercourse but no oral sex and denied any other sexual contact. All partners had been male.

On the next page: Diagnosis and case continuation >>

DIAGNOSIS

There is some variation in the presentation of women experiencing ectopic pregnancy; this may be due to differences in the pathologic mechanisms of ectopic pregnancy. Patients may be asymptomatic, hemodynamically compromised, or somewhere in between.3 Typical clinical signs include abdominal pain, amenorrhea, and vaginal bleeding. Approximately 40% to 50% of patients present with vaginal bleeding, 50% may have a palpable adnexal mass, and 75% may have abdominal tenderness.3 Only about 50% of women with ectopic pregnancies present with these typical symptoms.3

The patient may also experience common symptoms of early pregnancy, such as nausea, fatigue, and breast fullness. Worrisome signs and symptoms, including abdominal guarding, hypotension, tachycardia, shock, shoulder pain from peritoneal irritation, dizziness, fever, and vomiting, may also be present.3,7 Approximately 20% of patients with ectopic pregnancies are hemodynamically compromised at presentation, which is highly suggestive of rupture.3

Risk factors

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include previous ectopic pregnancy; previous tubal procedures; history of sexually transmitted disease or genital infections; infertility; use of assisted reproductive technology; previous abdominal or pelvic surgery; smoking; pelvic inflammatory disease; exposure in utero to diethylstilbestrol; and previous intrauterine device use.2,5,7,8 Knowledge of these risk factors can help identify a patient with an ectopic pregnancy.

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is most certainly a clinical challenge. The differential diagnosis is based upon history and physical findings; the list can be lengthy if both vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain (nonspecific symptoms common in women who miscarry) are present.7 Prompt completion of diagnostic testing is critical in making a definitive diagnosis. Possible diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

CASE Upon examination, the patient appeared comfortable and relaxed, and there were no signs of distress. Blood pressure was 100/65 mm Hg, pulse rate was 72 beats/min, and temperature was 99.0°F. There was no tenderness upon abdominal examination. Pelvic examination revealed a small amount of brown vaginal discharge but no active bleeding or pooled blood, clots, or tissue. The cervical os was closed, and positive Chadwick sign was present. Bimanual examination revealed no cervical motion tenderness. The uterus was soft, mobile, and nontender, and consistent in size with a gestation at eight weeks. There were no palpable adnexa, ovaries, or masses. There was no pain with bimanual examination and no evidence of tenderness at the posterior fornix. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

It is important to note that examination results in the case patient are not unusual in a woman with a small, unruptured ectopic pregnancy. All findings were normal except for the scant brown vaginal discharge. Abdominal and adnexal tenderness are common, as is a palpable adnexal mass; but absence of a detectable mass does not exclude ectopic pregnancy.1 Pathologic findings may include severe abdominal tenderness and pain, significant vaginal bleeding, passage of clots, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension.

Diagnostic workup

Laboratory tests are critical to making an accurate diagnosis for women whose history and physical examination results are consistent with ectopic pregnancy. Assessment for ectopic pregnancy should include a urine pregnancy test, transvaginal ultrasound, measurement of serum ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) level, and occasionally, diagnostic curettage.1 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, a complete blood count (CBC) is necessary to assess anemia and platelet functioning. Coagulation tests may be required for worrisome bleeding. Blood type, Rh status, and antibody screen are also necessary to determine whether a patient who is Rh D-negative will require Rh immune globulin. See Table 2 for the patient’s laboratory test results.

In a patient with a ß-hCG level greater than the discriminatory cutoff value of 1,500 to 1,800 mIU/mL, the level above which an intrauterine gestational sac is visible on transvaginal ultrasound in a normal pregnancy, an empty uterus is considered an ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise.3 In a definite intrauterine pregnancy of about six weeks’ gestation, transvaginal ultrasound reveals a gestational sac that contains a yolk sac and a fetal pole.3

CASE The patient’s presenting symptoms, combined with a positive pregnancy test, ß-hCG level of 1,850 mIU/mL, and a complex adnexal mass in the right fallopian tube, were highly suggestive of an unruptured ectopic pregnancy (see Table 3 for the patient’s transvaginal ultrasound findings). There was also a secondary finding of a corpus luteum cyst. Other diagnoses were ruled out, and the patient was diagnosed with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

A patient with an ectopic pregnancy who presents with pain and hemodynamic instability should be referred immediately for appropriate surgical care.7 Otherwise, once the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is confirmed, the patient should be referred to an obstetric specialist. Treatments for ectopic pregnancy include expectant management and surgery—which will be discussed briefly—and medical management, which is the focus of this review.5

Expectant management

Most ectopic pregnancies are diagnosed early as a result of accurate, minimally invasive and noninvasive diagnostic tools and greater awareness of risk factors. Since the natural course of early ectopic pregnancy is often self-limited, eventually resulting in tubal abortion or reabsorption, expectant management is a viable option.9

This treatment option may be considered if the patient is asymptomatic; ß-hCG is < 200 mIU/mL; the ectopic mass is < 3 cm; and no fetal heartbeat is present.1,2 With this approach, patients must be willing to accept the risk for tubal rupture and agree to close monitoring of ß-hCG levels. The ß-hCG level must be measured every 24 to 48 hours in order to determine if it is declining adequately, plateauing, or increasing.2,5

Surgery

For the hemodynamically unstable patient, the treatment decision is relatively straightforward. Optimal treatment for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is immediate surgery, which may include salpingostomy or salpingectomy.10 Surgery may also be considered for hemodynamically stable patients with nonruptured ectopic pregnancies; in addition to her clinical presentation, overall management may be driven by a patient’s preferences.5 Salpingostomy and salpingectomy can be performed either laparoscopically or via laparotomy, depending on the specific situation.

Medical management

The use of methotrexate for the management of unruptured ectopic pregnancy was introduced in the early 1980s.11 Initially, protocols called for multiple doses administered during the course of an inpatient stay. Further research led to revised treatment recommendations and today, medical management most often consists of a single dose of methotrexate with outpatient follow-up.3

Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist often used as an antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent. In ectopic pregnancy, it inhibits growth of the rapidly dividing trophoblastic cells and ultimately ends the pregnancy.2 Outcomes of medical management are comparable to those of surgical treatment, including the potential for future normal pregnancies.2,5

An analysis of US trends in ectopic pregnancy management from 2002-2007 revealed that the use of methotrexate increased from 11.1% to 35.1% during that time, while the use of surgical approaches declined from 90% to 65%.10 Medical management of ectopic pregnancy eliminates the costs of surgery, anesthesia, and hospitalization and avoids potential complications of surgery and anesthesia.

Appropriate candidates

A hemodynamically stable patient with a confirmed or high clinical suspicion of ectopic pregnancy, an unruptured mass, no active bleeding, and low ß-hCG levels (< 5,000 mIU/mL) can be considered for methotrexate therapy.2,3,9 It is critical that medically managed patients be willing and able to adhere to all follow-up appointments.9 Before initiating treatment, normal serum creatinine and transaminase levels should be confirmed, and there should be no evidence of significant anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia.2 To detect any adverse effects of methotrexate on renal, hepatic, and hematologic functioning, these tests are repeated one week after administration.2

Contraindications

Contraindications to methotrexate treatment include breastfeeding, immunodeficiency, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease or other chronic liver disease, preexisting blood dyscrasias (eg, bone marrow hypoplasia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or significant anemia), known sensitivity to methotrexate, active pulmonary disease, peptic ulcer, and hepatic, renal, or hematologic dysfunction. Relative contraindications are a gestational sac larger than 3.5 cm and embryonic cardiac motion.2

On the next page: Patient education >>

PATIENT EDUCATION AND INFORMED CONSENT

A diagnosis of unruptured ectopic pregnancy requires patient education about the condition and its treatment options. The clinician should explain what an ectopic pregnancy is and distinguish between unruptured and ruptured. A discussion of the benefits and risks of each treatment option for which the patient is an appropriate candidate, as well as what to anticipate during treatment, is needed. Emotional support for impending pregnancy loss should also be provided.

For patients who choose medical management, education includes methotrexate-specific information and written instructions to follow after methotrexate administration. Patients must be instructed about the use of safety precautions after treatment (eg, the toilet should be double-flushed with the lid closed during the first 72 hours after treatment to prevent exposing others to methotrexate in urine and stool), the need for adherence to follow-up visits, and warning signs of a possible rupture.5 These warning signs are listed in Table 4.

The most common adverse effects of methotrexate are gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, stomatitis). Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol, NSAIDs, folic acid supplements, excessive sun exposure (due to photosensitivity), strenuous exercise, and sexual intercourse until ß-hCG has returned to nonpregnant levels. Other adverse effects may include a temporary elevation in liver enzymes and rarely, alopecia. Abdominal pain may occur a few days after methotrexate administration, likely from the cytotoxic effects of the drug on the trophoblastic tissue.

Informed consent is required prior to methotrexate administration. The patient must be advised of the potential risks of medical management with methotrexate, including rupture of the ectopic pregnancy during treatment, inadvertent administration of methotrexate in the presence of an early intrauterine embryo, allergic reaction to methotrexate, and methotrexate-induced pneumonitis.5

CASE After lengthy discussion of the treatment options, the patient chose medical management with methotrexate. She verbalized her understanding of the teaching provided and signed an informed consent document.

METHOTREXATE REGIMENS

Protocols for single-dose, two-dose, and fixed multidose methotrexate regimens are described in the medical literature, according to a 2008 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin.2 A 2013 practice committee opinion of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) indicates that single-dose and multiple-dose regimens are used most often.12

With methotrexate treatment, complete resolution of ectopic pregnancy usually occurs in two to three weeks but may require up to six to eight weeks, depending on how high the ß-hCG level is when treatment begins.12

Single-dose

In the single-dose regimen, an intramuscular (IM) injection of methotrexate 50 mg/m2 is administered on day 1. The ß-hCG levels are measured on days 4 and 7 after administration; a decrease of at least 15% in the ß-hCG level should be observed. The ß-hCG level is then measured weekly until it reaches < 2 mIU/mL or is undetectable.2 If the level does not decline, a repeat dose of methotrexate can be given, with measurement of ß-hCG on days 4 and 7 after the repeat dose. If the ß-hCG level fails to decrease, additional methotrexate or surgical intervention should be considered.

The single-dose regimen is more frequently used and is most successful when ß-hCG levels are low (< 5,000 mIU/mL), the ectopic mass is small

(< 3.5 cm), and embryonic cardiac activity is not observed on ultrasound.2,3 Patients with ß-hCG levels > 5,000 mIU/mL may be appropriate candidates for additional doses of methotrexate.2 In fact, the single-dose protocol provides for repeat doses of methotrexate if the ß-hCG level is not decreasing adequately.12

Multiple-dose

With the multiple-dose regimen, methotrexate 1 mg/kg IM is administered on days 1, 3, 5, and 7; on days 2, 4, 6, and 8, the patient receives leucovorin (folinic acid) 0.1 mg/kg IM. The ß-hCG level is measured on days methotrexate is administered; once the minimum 15% decline is observed, ß-hCG is measured weekly until a nonpregnant level is reached.12

The patient received a single dose of methotrexate 50 mg/m2 IM on day 1 and returned to the clinic for follow-up on days 4 and 7 posttreatment. On day 4, her ß-hCG level was 1,060 mIU/mL; on day 7, it was 470 mIU/mL. Also on day 7, blood was drawn for a CBC and comprehensive metabolic panel; results were within normal limits. The patient continued weekly follow-up until her ß-hCG level decreased to < 2 mIU/mL.

On the next page: Follow-up and conclusion >>

FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRALS

Close monitoring of ß-hCG levels, as described previously, is essential after methotrexate treatment in order to confirm that the pregnancy has been terminated and reduce the risk for tubal rupture. Clinicians should also be sensitive to the sequelae of loss of a pregnancy and refer patients as needed to appropriate health care professionals for grief support.

CASE The patient was referred to an obstetrics clinic and reported for all scheduled follow-up appointments. She was discharged from care after a full reduction in her ß-hCG to nonpregnant levels. While at the clinic, the patient was referred to social services for psychosocial counseling.

CONCLUSION

Ectopic implantation is a serious complication that may occur during the first trimester of pregnancy. Worldwide, it is the leading cause of maternal death in the first trimester. For women who meet specific criteria, outpatient treatment of early ectopic pregnancy with methotrexate avoids surgery and decreases the overall cost of care. Medical management and conservative surgical management offer the patient comparable outcomes for tubal patency preservation and risk for ectopic pregnancy recurrence.11

REFERENCES

1. Lozeau AM, Potter B. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(9):1707-1714.

2. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 94: medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1479-1485.

3. Sepilian VP, Wood E. Ectopic pregnancy. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2041923-overview. Medscape. Accessed June 19, 2014.

4. Stein JC, Wang R, Adler N, et al. Emergency physician ultrasonography for evaluating patients at risk for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):674-683.

5. Murtaza UI, Ortmann MJ, Mando-Vandrick J, Lee ASD. Management of first-trimester complications in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(2):99-111.

6. Sewell CA, Cundiff GW. Trends for inpatient treatment of tubal pregnancy in Maryland. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):404-408.

7. Nama V, Manyonda I. Tubal ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(4):443-453.

8. Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Gracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic first-trimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(1):36-43.

9. Hajenius PJ, Mol F, Mol BW, et al. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD000324.

10. Hoover KW, Tao G, Kent CK. Trends in the diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3): 495-502.

11. Autry A. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy: is there something new? Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):733.

12. The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):638-644.

Ectopic pregnancy is a significant health risk to women during their childbearing years; approximately 6% of all pregnancy-related deaths are due to ectopic pregnancy.1-3 Some 1% to 2% of all pregnancies in the United States each year—approximately 100,000 cases—are ectopic, with an estimated annual cost of care approaching $1.1 billion.4 The incidence of ectopic pregnancy has increased in the past 20 years; in one analysis, ectopic pregnancy was diagnosed in 18% of women who presented to an emergency department (ED) with first trimester vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, or both.5 This growing prevalence is attributed to a number of factors, including the sensitivity of current diagnostic methods in detecting early ectopic pregnancy, the greater incidence of salpingitis, and the growing use of assisted reproductive technologies.2,6

While the number of ectopic pregnancies is on the rise, the proportion of patients requiring hospitalization for surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy has decreased significantly. Today, for appropriate patients, many clinicians manage ectopic pregnancy on an outpatient basis using the drug methotrexate.6

In this article, we will present an overview of the current status of medical management of ectopic pregnancy, along with a case study. The case study describes a patient diagnosed with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy who was managed medically with methotrexate. It illustrates how, with early diagnosis, clinicians can intervene to make medical management an effective treatment option in selected situations.

The patient reported a history of oral contraceptive use until approximately three months prior to this pregnancy. She was taking no medications and had no known drug allergies. Her previous pregnancies included two uncomplicated vaginal births at term and one miscarriage at six to seven weeks’ gestation two years ago. She also reported a dilation and curettage after the miscarriage. Her medical, surgical, and gynecologic histories were otherwise noncontributory. A review of systems was otherwise negative.

Sexual history revealed that the patient was married and monogamous with her husband of five years. She disclosed four previous sexual partners and inconsistent use of condoms with those partners; no current condom use was reported. Seven years ago, she tested positive for gonorrhea and chlamydia and was treated concurrently with her partner. Subsequent diagnostics were negative. She reported vaginal intercourse but no oral sex and denied any other sexual contact. All partners had been male.

On the next page: Diagnosis and case continuation >>

DIAGNOSIS

There is some variation in the presentation of women experiencing ectopic pregnancy; this may be due to differences in the pathologic mechanisms of ectopic pregnancy. Patients may be asymptomatic, hemodynamically compromised, or somewhere in between.3 Typical clinical signs include abdominal pain, amenorrhea, and vaginal bleeding. Approximately 40% to 50% of patients present with vaginal bleeding, 50% may have a palpable adnexal mass, and 75% may have abdominal tenderness.3 Only about 50% of women with ectopic pregnancies present with these typical symptoms.3

The patient may also experience common symptoms of early pregnancy, such as nausea, fatigue, and breast fullness. Worrisome signs and symptoms, including abdominal guarding, hypotension, tachycardia, shock, shoulder pain from peritoneal irritation, dizziness, fever, and vomiting, may also be present.3,7 Approximately 20% of patients with ectopic pregnancies are hemodynamically compromised at presentation, which is highly suggestive of rupture.3

Risk factors

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include previous ectopic pregnancy; previous tubal procedures; history of sexually transmitted disease or genital infections; infertility; use of assisted reproductive technology; previous abdominal or pelvic surgery; smoking; pelvic inflammatory disease; exposure in utero to diethylstilbestrol; and previous intrauterine device use.2,5,7,8 Knowledge of these risk factors can help identify a patient with an ectopic pregnancy.

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is most certainly a clinical challenge. The differential diagnosis is based upon history and physical findings; the list can be lengthy if both vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain (nonspecific symptoms common in women who miscarry) are present.7 Prompt completion of diagnostic testing is critical in making a definitive diagnosis. Possible diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

CASE Upon examination, the patient appeared comfortable and relaxed, and there were no signs of distress. Blood pressure was 100/65 mm Hg, pulse rate was 72 beats/min, and temperature was 99.0°F. There was no tenderness upon abdominal examination. Pelvic examination revealed a small amount of brown vaginal discharge but no active bleeding or pooled blood, clots, or tissue. The cervical os was closed, and positive Chadwick sign was present. Bimanual examination revealed no cervical motion tenderness. The uterus was soft, mobile, and nontender, and consistent in size with a gestation at eight weeks. There were no palpable adnexa, ovaries, or masses. There was no pain with bimanual examination and no evidence of tenderness at the posterior fornix. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

It is important to note that examination results in the case patient are not unusual in a woman with a small, unruptured ectopic pregnancy. All findings were normal except for the scant brown vaginal discharge. Abdominal and adnexal tenderness are common, as is a palpable adnexal mass; but absence of a detectable mass does not exclude ectopic pregnancy.1 Pathologic findings may include severe abdominal tenderness and pain, significant vaginal bleeding, passage of clots, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension.

Diagnostic workup

Laboratory tests are critical to making an accurate diagnosis for women whose history and physical examination results are consistent with ectopic pregnancy. Assessment for ectopic pregnancy should include a urine pregnancy test, transvaginal ultrasound, measurement of serum ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) level, and occasionally, diagnostic curettage.1 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, a complete blood count (CBC) is necessary to assess anemia and platelet functioning. Coagulation tests may be required for worrisome bleeding. Blood type, Rh status, and antibody screen are also necessary to determine whether a patient who is Rh D-negative will require Rh immune globulin. See Table 2 for the patient’s laboratory test results.

In a patient with a ß-hCG level greater than the discriminatory cutoff value of 1,500 to 1,800 mIU/mL, the level above which an intrauterine gestational sac is visible on transvaginal ultrasound in a normal pregnancy, an empty uterus is considered an ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise.3 In a definite intrauterine pregnancy of about six weeks’ gestation, transvaginal ultrasound reveals a gestational sac that contains a yolk sac and a fetal pole.3

CASE The patient’s presenting symptoms, combined with a positive pregnancy test, ß-hCG level of 1,850 mIU/mL, and a complex adnexal mass in the right fallopian tube, were highly suggestive of an unruptured ectopic pregnancy (see Table 3 for the patient’s transvaginal ultrasound findings). There was also a secondary finding of a corpus luteum cyst. Other diagnoses were ruled out, and the patient was diagnosed with an unruptured ectopic pregnancy.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

A patient with an ectopic pregnancy who presents with pain and hemodynamic instability should be referred immediately for appropriate surgical care.7 Otherwise, once the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is confirmed, the patient should be referred to an obstetric specialist. Treatments for ectopic pregnancy include expectant management and surgery—which will be discussed briefly—and medical management, which is the focus of this review.5

Expectant management

Most ectopic pregnancies are diagnosed early as a result of accurate, minimally invasive and noninvasive diagnostic tools and greater awareness of risk factors. Since the natural course of early ectopic pregnancy is often self-limited, eventually resulting in tubal abortion or reabsorption, expectant management is a viable option.9

This treatment option may be considered if the patient is asymptomatic; ß-hCG is < 200 mIU/mL; the ectopic mass is < 3 cm; and no fetal heartbeat is present.1,2 With this approach, patients must be willing to accept the risk for tubal rupture and agree to close monitoring of ß-hCG levels. The ß-hCG level must be measured every 24 to 48 hours in order to determine if it is declining adequately, plateauing, or increasing.2,5

Surgery

For the hemodynamically unstable patient, the treatment decision is relatively straightforward. Optimal treatment for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is immediate surgery, which may include salpingostomy or salpingectomy.10 Surgery may also be considered for hemodynamically stable patients with nonruptured ectopic pregnancies; in addition to her clinical presentation, overall management may be driven by a patient’s preferences.5 Salpingostomy and salpingectomy can be performed either laparoscopically or via laparotomy, depending on the specific situation.

Medical management

The use of methotrexate for the management of unruptured ectopic pregnancy was introduced in the early 1980s.11 Initially, protocols called for multiple doses administered during the course of an inpatient stay. Further research led to revised treatment recommendations and today, medical management most often consists of a single dose of methotrexate with outpatient follow-up.3

Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist often used as an antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent. In ectopic pregnancy, it inhibits growth of the rapidly dividing trophoblastic cells and ultimately ends the pregnancy.2 Outcomes of medical management are comparable to those of surgical treatment, including the potential for future normal pregnancies.2,5

An analysis of US trends in ectopic pregnancy management from 2002-2007 revealed that the use of methotrexate increased from 11.1% to 35.1% during that time, while the use of surgical approaches declined from 90% to 65%.10 Medical management of ectopic pregnancy eliminates the costs of surgery, anesthesia, and hospitalization and avoids potential complications of surgery and anesthesia.

Appropriate candidates

A hemodynamically stable patient with a confirmed or high clinical suspicion of ectopic pregnancy, an unruptured mass, no active bleeding, and low ß-hCG levels (< 5,000 mIU/mL) can be considered for methotrexate therapy.2,3,9 It is critical that medically managed patients be willing and able to adhere to all follow-up appointments.9 Before initiating treatment, normal serum creatinine and transaminase levels should be confirmed, and there should be no evidence of significant anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia.2 To detect any adverse effects of methotrexate on renal, hepatic, and hematologic functioning, these tests are repeated one week after administration.2

Contraindications

Contraindications to methotrexate treatment include breastfeeding, immunodeficiency, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease or other chronic liver disease, preexisting blood dyscrasias (eg, bone marrow hypoplasia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or significant anemia), known sensitivity to methotrexate, active pulmonary disease, peptic ulcer, and hepatic, renal, or hematologic dysfunction. Relative contraindications are a gestational sac larger than 3.5 cm and embryonic cardiac motion.2

On the next page: Patient education >>

PATIENT EDUCATION AND INFORMED CONSENT

A diagnosis of unruptured ectopic pregnancy requires patient education about the condition and its treatment options. The clinician should explain what an ectopic pregnancy is and distinguish between unruptured and ruptured. A discussion of the benefits and risks of each treatment option for which the patient is an appropriate candidate, as well as what to anticipate during treatment, is needed. Emotional support for impending pregnancy loss should also be provided.

For patients who choose medical management, education includes methotrexate-specific information and written instructions to follow after methotrexate administration. Patients must be instructed about the use of safety precautions after treatment (eg, the toilet should be double-flushed with the lid closed during the first 72 hours after treatment to prevent exposing others to methotrexate in urine and stool), the need for adherence to follow-up visits, and warning signs of a possible rupture.5 These warning signs are listed in Table 4.

The most common adverse effects of methotrexate are gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, stomatitis). Patients should be advised to avoid alcohol, NSAIDs, folic acid supplements, excessive sun exposure (due to photosensitivity), strenuous exercise, and sexual intercourse until ß-hCG has returned to nonpregnant levels. Other adverse effects may include a temporary elevation in liver enzymes and rarely, alopecia. Abdominal pain may occur a few days after methotrexate administration, likely from the cytotoxic effects of the drug on the trophoblastic tissue.

Informed consent is required prior to methotrexate administration. The patient must be advised of the potential risks of medical management with methotrexate, including rupture of the ectopic pregnancy during treatment, inadvertent administration of methotrexate in the presence of an early intrauterine embryo, allergic reaction to methotrexate, and methotrexate-induced pneumonitis.5

CASE After lengthy discussion of the treatment options, the patient chose medical management with methotrexate. She verbalized her understanding of the teaching provided and signed an informed consent document.

METHOTREXATE REGIMENS

Protocols for single-dose, two-dose, and fixed multidose methotrexate regimens are described in the medical literature, according to a 2008 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin.2 A 2013 practice committee opinion of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) indicates that single-dose and multiple-dose regimens are used most often.12

With methotrexate treatment, complete resolution of ectopic pregnancy usually occurs in two to three weeks but may require up to six to eight weeks, depending on how high the ß-hCG level is when treatment begins.12

Single-dose

In the single-dose regimen, an intramuscular (IM) injection of methotrexate 50 mg/m2 is administered on day 1. The ß-hCG levels are measured on days 4 and 7 after administration; a decrease of at least 15% in the ß-hCG level should be observed. The ß-hCG level is then measured weekly until it reaches < 2 mIU/mL or is undetectable.2 If the level does not decline, a repeat dose of methotrexate can be given, with measurement of ß-hCG on days 4 and 7 after the repeat dose. If the ß-hCG level fails to decrease, additional methotrexate or surgical intervention should be considered.

The single-dose regimen is more frequently used and is most successful when ß-hCG levels are low (< 5,000 mIU/mL), the ectopic mass is small

(< 3.5 cm), and embryonic cardiac activity is not observed on ultrasound.2,3 Patients with ß-hCG levels > 5,000 mIU/mL may be appropriate candidates for additional doses of methotrexate.2 In fact, the single-dose protocol provides for repeat doses of methotrexate if the ß-hCG level is not decreasing adequately.12

Multiple-dose

With the multiple-dose regimen, methotrexate 1 mg/kg IM is administered on days 1, 3, 5, and 7; on days 2, 4, 6, and 8, the patient receives leucovorin (folinic acid) 0.1 mg/kg IM. The ß-hCG level is measured on days methotrexate is administered; once the minimum 15% decline is observed, ß-hCG is measured weekly until a nonpregnant level is reached.12

The patient received a single dose of methotrexate 50 mg/m2 IM on day 1 and returned to the clinic for follow-up on days 4 and 7 posttreatment. On day 4, her ß-hCG level was 1,060 mIU/mL; on day 7, it was 470 mIU/mL. Also on day 7, blood was drawn for a CBC and comprehensive metabolic panel; results were within normal limits. The patient continued weekly follow-up until her ß-hCG level decreased to < 2 mIU/mL.

On the next page: Follow-up and conclusion >>

FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRALS

Close monitoring of ß-hCG levels, as described previously, is essential after methotrexate treatment in order to confirm that the pregnancy has been terminated and reduce the risk for tubal rupture. Clinicians should also be sensitive to the sequelae of loss of a pregnancy and refer patients as needed to appropriate health care professionals for grief support.

CASE The patient was referred to an obstetrics clinic and reported for all scheduled follow-up appointments. She was discharged from care after a full reduction in her ß-hCG to nonpregnant levels. While at the clinic, the patient was referred to social services for psychosocial counseling.

CONCLUSION

Ectopic implantation is a serious complication that may occur during the first trimester of pregnancy. Worldwide, it is the leading cause of maternal death in the first trimester. For women who meet specific criteria, outpatient treatment of early ectopic pregnancy with methotrexate avoids surgery and decreases the overall cost of care. Medical management and conservative surgical management offer the patient comparable outcomes for tubal patency preservation and risk for ectopic pregnancy recurrence.11

REFERENCES

1. Lozeau AM, Potter B. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(9):1707-1714.

2. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 94: medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1479-1485.

3. Sepilian VP, Wood E. Ectopic pregnancy. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2041923-overview. Medscape. Accessed June 19, 2014.

4. Stein JC, Wang R, Adler N, et al. Emergency physician ultrasonography for evaluating patients at risk for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(6):674-683.

5. Murtaza UI, Ortmann MJ, Mando-Vandrick J, Lee ASD. Management of first-trimester complications in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(2):99-111.

6. Sewell CA, Cundiff GW. Trends for inpatient treatment of tubal pregnancy in Maryland. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):404-408.

7. Nama V, Manyonda I. Tubal ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(4):443-453.

8. Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Gracia CR, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in women with symptomatic first-trimester pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(1):36-43.

9. Hajenius PJ, Mol F, Mol BW, et al. Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD000324.

10. Hoover KW, Tao G, Kent CK. Trends in the diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3): 495-502.

11. Autry A. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy: is there something new? Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):733.

12. The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):638-644.

Adding rapid trichomonas test to the sexually transmitted infection panel boosts rapid treatment

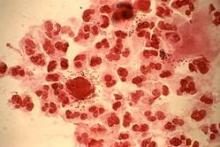

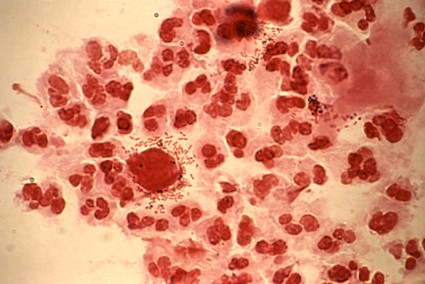

ATLANTA – Adding a rapid Trichomonas vaginalis test to the adolescent sexually transmitted infection laboratory regimen facilitated on-site diagnosis and treatment at an urban medical center emergency department.

The OSOM rapid trichomonas test provided point of care testing results in 10 minutes, with a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 99%, Dr. Heather Territo reported in a poster at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis approaches 25% in inner-city adolescents. Prior studies have demonstrated an association between Trichomonas vaginalis and cervical neoplasia, enhanced HIV transmission, and pregnancy complications.

After routine Trichomonas vaginalis testing was implemented at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, N.Y., in November 2011, 212 females aged 13-20 years were tested in the following year; 13.6% tested positive by rapid test and 15.5% by nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). In the year before routine testing was implemented, 31 of 234 patients were tested, based on a retrospective chart review. Treatment was administered to 24% and to 7% of patients during the respective study periods, said Dr. Territo of the hospital’s division of emergency medicine.

Additionally, two positive results were found in 20 males tested.

In the emergency department, Trichomonas vaginalis is often diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings; the positive predictive value of this approach is less than 50%. Direct microscopy of vaginal secretions has a sensitivity of about 60%-70%.

The rapid test and the NAAT test results were concordant in 178 of 188 cases (94.6%). Ten of the 33 positive NAAT tests (30%) were negative on the rapid test.

Dr. Territo reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Adding a rapid Trichomonas vaginalis test to the adolescent sexually transmitted infection laboratory regimen facilitated on-site diagnosis and treatment at an urban medical center emergency department.

The OSOM rapid trichomonas test provided point of care testing results in 10 minutes, with a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 99%, Dr. Heather Territo reported in a poster at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis approaches 25% in inner-city adolescents. Prior studies have demonstrated an association between Trichomonas vaginalis and cervical neoplasia, enhanced HIV transmission, and pregnancy complications.

After routine Trichomonas vaginalis testing was implemented at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, N.Y., in November 2011, 212 females aged 13-20 years were tested in the following year; 13.6% tested positive by rapid test and 15.5% by nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). In the year before routine testing was implemented, 31 of 234 patients were tested, based on a retrospective chart review. Treatment was administered to 24% and to 7% of patients during the respective study periods, said Dr. Territo of the hospital’s division of emergency medicine.

Additionally, two positive results were found in 20 males tested.

In the emergency department, Trichomonas vaginalis is often diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings; the positive predictive value of this approach is less than 50%. Direct microscopy of vaginal secretions has a sensitivity of about 60%-70%.

The rapid test and the NAAT test results were concordant in 178 of 188 cases (94.6%). Ten of the 33 positive NAAT tests (30%) were negative on the rapid test.

Dr. Territo reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Adding a rapid Trichomonas vaginalis test to the adolescent sexually transmitted infection laboratory regimen facilitated on-site diagnosis and treatment at an urban medical center emergency department.

The OSOM rapid trichomonas test provided point of care testing results in 10 minutes, with a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 99%, Dr. Heather Territo reported in a poster at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis approaches 25% in inner-city adolescents. Prior studies have demonstrated an association between Trichomonas vaginalis and cervical neoplasia, enhanced HIV transmission, and pregnancy complications.

After routine Trichomonas vaginalis testing was implemented at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, N.Y., in November 2011, 212 females aged 13-20 years were tested in the following year; 13.6% tested positive by rapid test and 15.5% by nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). In the year before routine testing was implemented, 31 of 234 patients were tested, based on a retrospective chart review. Treatment was administered to 24% and to 7% of patients during the respective study periods, said Dr. Territo of the hospital’s division of emergency medicine.

Additionally, two positive results were found in 20 males tested.

In the emergency department, Trichomonas vaginalis is often diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings; the positive predictive value of this approach is less than 50%. Direct microscopy of vaginal secretions has a sensitivity of about 60%-70%.

The rapid test and the NAAT test results were concordant in 178 of 188 cases (94.6%). Ten of the 33 positive NAAT tests (30%) were negative on the rapid test.

Dr. Territo reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE 2014 STD PREVENTION CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: A positive rapid trichomonas vaginalis test allows immediate treatment in the ED.

Major finding: Treatment was administered to 24% vs. 7% of patients before and after implementing routine testing.

Data source: A retrospective review of 234 patients, and a prospective evaluation of 212 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Territo reported having no disclosures.

U.S. gestational diabetes prevalence may be as high as 9.4%

The rate of gestational diabetes in the United States is somewhere between 4.6% and 9.4%, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Researchers compared data from birth certificates collected from 16 states to data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) in 21 states. PRAMS is a CDC-led surveillance project that works with state health departments to collect population-based data on maternal experiences before, during, and after pregnancy.

In 2010, the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus was 4.6% as listed on birth certificates, 8.7% on the PRAMS scale, and 9.2% as reported on either the PRAMS scale or birth certificates. The percent agreement between the sources was 94.1%, wrote Carla L. DeSisto, M.P.H., and her associates at the CDC (Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130415 [doi:10.5888/pcd11.130415]).

There was no significant difference in gestational diabetes prevalence between the two study periods examined – 8.1% in 2007-08 and 8.5% in 2009-10, according to an analysis of PRAMS data from 123,373 women. In both time periods, Utah had the lowest prevalence (5.7% and 5.6%, respectively) and Rhode Island had the highest (10.4% and 11.7%).

The rate of gestational diabetes in the United States is somewhere between 4.6% and 9.4%, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Researchers compared data from birth certificates collected from 16 states to data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) in 21 states. PRAMS is a CDC-led surveillance project that works with state health departments to collect population-based data on maternal experiences before, during, and after pregnancy.

In 2010, the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus was 4.6% as listed on birth certificates, 8.7% on the PRAMS scale, and 9.2% as reported on either the PRAMS scale or birth certificates. The percent agreement between the sources was 94.1%, wrote Carla L. DeSisto, M.P.H., and her associates at the CDC (Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130415 [doi:10.5888/pcd11.130415]).

There was no significant difference in gestational diabetes prevalence between the two study periods examined – 8.1% in 2007-08 and 8.5% in 2009-10, according to an analysis of PRAMS data from 123,373 women. In both time periods, Utah had the lowest prevalence (5.7% and 5.6%, respectively) and Rhode Island had the highest (10.4% and 11.7%).

The rate of gestational diabetes in the United States is somewhere between 4.6% and 9.4%, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Researchers compared data from birth certificates collected from 16 states to data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) in 21 states. PRAMS is a CDC-led surveillance project that works with state health departments to collect population-based data on maternal experiences before, during, and after pregnancy.

In 2010, the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus was 4.6% as listed on birth certificates, 8.7% on the PRAMS scale, and 9.2% as reported on either the PRAMS scale or birth certificates. The percent agreement between the sources was 94.1%, wrote Carla L. DeSisto, M.P.H., and her associates at the CDC (Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130415 [doi:10.5888/pcd11.130415]).

There was no significant difference in gestational diabetes prevalence between the two study periods examined – 8.1% in 2007-08 and 8.5% in 2009-10, according to an analysis of PRAMS data from 123,373 women. In both time periods, Utah had the lowest prevalence (5.7% and 5.6%, respectively) and Rhode Island had the highest (10.4% and 11.7%).

FROM PREVENTING CHRONIC DISEASE

Major finding: The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States is between 4.6% and 9.4%.

Data source: Statistical analysis of birth certificate data from 15 states and PRAMS data from 21 states.

Disclosures: No disclosures were reported.

Maternal antidepressants don’t increase infant cardiac malformations

Infants born to women who took antidepressants during the first trimester of their pregnancies showed no increase in cardiac malformations overall or in specific cardiac defects that earlier research had linked to fetal exposure to the drugs, investigators have reported.

Previously, paroxetine and sertraline had been associated with congenital cardiac malformations, chiefly septal defects, but "considerable controversy" remains on the subject, the researchers noted in a report published online June 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the current large, population-based cohort study, the investigators drew from Medicaid records for 46 states and the District of Columbia and identified 949,504 completed pregnancies during a 7-year period. A total of 64,389 of these women (6.8%) used an antidepressant during their first trimester, including SSRIs, tricyclics, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and bupropion.

The SSRIs taken by women most frequently were sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine, wrote Krista F. Huybrechts, Ph.D., of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates.

In the study’s initial analysis, cardiac malformations were diagnosed in 6,403 infants not exposed to antidepressants, for a rate of 72.3 malformations per 10,000 infants, and in 580 infants exposed to antidepressants, for a rate of 90.1 malformations per 10,000 infants. Once these data were adjusted to account for the effect of the underlying depression (indication bias), however, there was no association between the use of antidepressants in general and infant cardiac malformations, nor between specific antidepressants and specific cardiac malformations.

In particular, "we found no significant associations between paroxetine and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction or between sertraline and ventricular septal defect," Dr. Huybrechts and her associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 June 19 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828]).

In addition, numerous subgroup and sensitivity analyses found no such associations regardless of the women’s age, race, or use of monotherapy vs. polytherapy, and no dose-response relationships. In contrast, the data confirmed well-known associations between infant cardiac malformations and maternal diabetes, maternal use of anticonvulsants, and multiple gestations, which supports the premise that "the outcomes of interest were well captured in our study," the investigators said.

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Huybrechts reported no financial conflicts of interest; her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Infants born to women who took antidepressants during the first trimester of their pregnancies showed no increase in cardiac malformations overall or in specific cardiac defects that earlier research had linked to fetal exposure to the drugs, investigators have reported.

Previously, paroxetine and sertraline had been associated with congenital cardiac malformations, chiefly septal defects, but "considerable controversy" remains on the subject, the researchers noted in a report published online June 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the current large, population-based cohort study, the investigators drew from Medicaid records for 46 states and the District of Columbia and identified 949,504 completed pregnancies during a 7-year period. A total of 64,389 of these women (6.8%) used an antidepressant during their first trimester, including SSRIs, tricyclics, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and bupropion.

The SSRIs taken by women most frequently were sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine, wrote Krista F. Huybrechts, Ph.D., of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates.

In the study’s initial analysis, cardiac malformations were diagnosed in 6,403 infants not exposed to antidepressants, for a rate of 72.3 malformations per 10,000 infants, and in 580 infants exposed to antidepressants, for a rate of 90.1 malformations per 10,000 infants. Once these data were adjusted to account for the effect of the underlying depression (indication bias), however, there was no association between the use of antidepressants in general and infant cardiac malformations, nor between specific antidepressants and specific cardiac malformations.

In particular, "we found no significant associations between paroxetine and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction or between sertraline and ventricular septal defect," Dr. Huybrechts and her associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 June 19 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828]).

In addition, numerous subgroup and sensitivity analyses found no such associations regardless of the women’s age, race, or use of monotherapy vs. polytherapy, and no dose-response relationships. In contrast, the data confirmed well-known associations between infant cardiac malformations and maternal diabetes, maternal use of anticonvulsants, and multiple gestations, which supports the premise that "the outcomes of interest were well captured in our study," the investigators said.

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Huybrechts reported no financial conflicts of interest; her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Infants born to women who took antidepressants during the first trimester of their pregnancies showed no increase in cardiac malformations overall or in specific cardiac defects that earlier research had linked to fetal exposure to the drugs, investigators have reported.

Previously, paroxetine and sertraline had been associated with congenital cardiac malformations, chiefly septal defects, but "considerable controversy" remains on the subject, the researchers noted in a report published online June 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the current large, population-based cohort study, the investigators drew from Medicaid records for 46 states and the District of Columbia and identified 949,504 completed pregnancies during a 7-year period. A total of 64,389 of these women (6.8%) used an antidepressant during their first trimester, including SSRIs, tricyclics, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and bupropion.

The SSRIs taken by women most frequently were sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine, wrote Krista F. Huybrechts, Ph.D., of the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates.

In the study’s initial analysis, cardiac malformations were diagnosed in 6,403 infants not exposed to antidepressants, for a rate of 72.3 malformations per 10,000 infants, and in 580 infants exposed to antidepressants, for a rate of 90.1 malformations per 10,000 infants. Once these data were adjusted to account for the effect of the underlying depression (indication bias), however, there was no association between the use of antidepressants in general and infant cardiac malformations, nor between specific antidepressants and specific cardiac malformations.

In particular, "we found no significant associations between paroxetine and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction or between sertraline and ventricular septal defect," Dr. Huybrechts and her associates said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2014 June 19 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828]).

In addition, numerous subgroup and sensitivity analyses found no such associations regardless of the women’s age, race, or use of monotherapy vs. polytherapy, and no dose-response relationships. In contrast, the data confirmed well-known associations between infant cardiac malformations and maternal diabetes, maternal use of anticonvulsants, and multiple gestations, which supports the premise that "the outcomes of interest were well captured in our study," the investigators said.

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Huybrechts reported no financial conflicts of interest; her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: First trimester use of antidepressants does not significantly increase fetal cardiac malformation risk.

Major finding: After adjustment, there was no association between the use of antidepressants in general and infant cardiac malformations, nor between specific antidepressants and specific cardiac malformations.

Data source: A nationwide cohort study involving 949,504 pregnancies in which 6.8% of the women took antidepressants during the first trimester.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Huybrechts reported no financial conflicts of interest; her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Maternal infections associated with increased risk of cerebral palsy

VANCOUVER, B.C. – Intra- or extra-amniotic fluid infections during pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of having a child with cerebral palsy, according to analysis of six million California birth records.

Researchers found that pregnant women who were hospitalized with diagnosis of chorioamnionitis had a fourfold increase in risk of having a child with cerebral palsy (CP), while genitourinary and respiratory infections increased that risk by twofold, each.