User login

Most FGR patients deliver vaginally after induction of labor

CHICAGO – Induction of labor is reasonable in cases involving fetal growth restriction, as most patients who are induced deliver vaginally rather than by cesarean section, according to findings from a retrospective cohort study.

Of 134 patients who underwent induction of labor for fetal growth restriction (FGR), 81% delivered vaginally, Dr. Kari Horowitz reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In those who delivered by C-section, the indication was nonreassuring fetal heart rate in 88% of cases, according to Dr. Horowitz, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

The cesarean delivery rates were highest in cases involving nulliparity, prematurity, hypertension, oligohydramnios, and use of prostaglandins. Logistic regression analysis showed that only prematurity was significantly associated with cesarean delivery (odds ratio, 3.81).

The findings are based on a chart review of all patients with singleton pregnancy, a non-anomalous fetus, and suspected FGR (estimated fetal weight and/or fetal abdominal circumference less than the 10th percentile, or no interval growth) who delivered between January 2008 and December 2012. Patients were excluded from the study if there was multiple gestation; fetal anomalies or aneuploidy; malpresentation; a history of prior cesarean delivery; or other contraindications to vaginal delivery.

Although FGR is associated with neonatal risks, including intrauterine demise, neonatal morbidity and mortality, and postnatal morbidity, it is not considered an indication for cesarean delivery. Affected fetuses, however, may be at risk for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing and fetal distress due to uteroplacental insufficiency. Delivery at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks is recommended in cases of isolated FGR, and delivery before 38 weeks is recommended in cases with additional risk factors for adverse outcomes.

"Prior studies have found increased risk of cesarean delivery in FGR neonates undergoing induction of labor as compared to spontaneous labor, and no difference in rates of cesarean delivery or adverse outcomes in patients undergoing induction of labor versus expectant management. Term FGR fetuses have been found to have significantly higher rates of cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing," Dr. Horowitz noted.

"It is recommended that these patients undergo a trial of labor," Dr. Horowitz concluded, noting that preterm patients should be counseled about the increased risk of cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing.

Dr. Horowitz reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Induction of labor is reasonable in cases involving fetal growth restriction, as most patients who are induced deliver vaginally rather than by cesarean section, according to findings from a retrospective cohort study.

Of 134 patients who underwent induction of labor for fetal growth restriction (FGR), 81% delivered vaginally, Dr. Kari Horowitz reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In those who delivered by C-section, the indication was nonreassuring fetal heart rate in 88% of cases, according to Dr. Horowitz, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

The cesarean delivery rates were highest in cases involving nulliparity, prematurity, hypertension, oligohydramnios, and use of prostaglandins. Logistic regression analysis showed that only prematurity was significantly associated with cesarean delivery (odds ratio, 3.81).

The findings are based on a chart review of all patients with singleton pregnancy, a non-anomalous fetus, and suspected FGR (estimated fetal weight and/or fetal abdominal circumference less than the 10th percentile, or no interval growth) who delivered between January 2008 and December 2012. Patients were excluded from the study if there was multiple gestation; fetal anomalies or aneuploidy; malpresentation; a history of prior cesarean delivery; or other contraindications to vaginal delivery.

Although FGR is associated with neonatal risks, including intrauterine demise, neonatal morbidity and mortality, and postnatal morbidity, it is not considered an indication for cesarean delivery. Affected fetuses, however, may be at risk for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing and fetal distress due to uteroplacental insufficiency. Delivery at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks is recommended in cases of isolated FGR, and delivery before 38 weeks is recommended in cases with additional risk factors for adverse outcomes.

"Prior studies have found increased risk of cesarean delivery in FGR neonates undergoing induction of labor as compared to spontaneous labor, and no difference in rates of cesarean delivery or adverse outcomes in patients undergoing induction of labor versus expectant management. Term FGR fetuses have been found to have significantly higher rates of cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing," Dr. Horowitz noted.

"It is recommended that these patients undergo a trial of labor," Dr. Horowitz concluded, noting that preterm patients should be counseled about the increased risk of cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing.

Dr. Horowitz reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – Induction of labor is reasonable in cases involving fetal growth restriction, as most patients who are induced deliver vaginally rather than by cesarean section, according to findings from a retrospective cohort study.

Of 134 patients who underwent induction of labor for fetal growth restriction (FGR), 81% delivered vaginally, Dr. Kari Horowitz reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In those who delivered by C-section, the indication was nonreassuring fetal heart rate in 88% of cases, according to Dr. Horowitz, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

The cesarean delivery rates were highest in cases involving nulliparity, prematurity, hypertension, oligohydramnios, and use of prostaglandins. Logistic regression analysis showed that only prematurity was significantly associated with cesarean delivery (odds ratio, 3.81).

The findings are based on a chart review of all patients with singleton pregnancy, a non-anomalous fetus, and suspected FGR (estimated fetal weight and/or fetal abdominal circumference less than the 10th percentile, or no interval growth) who delivered between January 2008 and December 2012. Patients were excluded from the study if there was multiple gestation; fetal anomalies or aneuploidy; malpresentation; a history of prior cesarean delivery; or other contraindications to vaginal delivery.

Although FGR is associated with neonatal risks, including intrauterine demise, neonatal morbidity and mortality, and postnatal morbidity, it is not considered an indication for cesarean delivery. Affected fetuses, however, may be at risk for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing and fetal distress due to uteroplacental insufficiency. Delivery at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks is recommended in cases of isolated FGR, and delivery before 38 weeks is recommended in cases with additional risk factors for adverse outcomes.

"Prior studies have found increased risk of cesarean delivery in FGR neonates undergoing induction of labor as compared to spontaneous labor, and no difference in rates of cesarean delivery or adverse outcomes in patients undergoing induction of labor versus expectant management. Term FGR fetuses have been found to have significantly higher rates of cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing," Dr. Horowitz noted.

"It is recommended that these patients undergo a trial of labor," Dr. Horowitz concluded, noting that preterm patients should be counseled about the increased risk of cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart tracing.

Dr. Horowitz reported having no disclosures.

AT THE ACOG ANNUAL CLINICAL MEETING

A brief scale IDs sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy

CHICAGO – A four-item pregnancy-specific sleep disturbance scale proved valid as a screening tool for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy, and was associated with preeclampsia in a study of more than 1,100 women.

After adjustment for potential confounders – including sociodemographics, body mass index, and high blood pressure – a higher score on the short-form pregnancy-specific questionnaire (SF-SPQ) was significantly associated with an increase in the risk of preeclampsia (adjusted risk ratio, 1.54) Alpna Agrawal, Ph.D., of the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

"In a clinical setting, the short format and validity of SF-SPQ shown in this study suggests it may be a quick and effective method to screen women at risk for sleep-disordered breathing," Dr. Agrawal wrote.

The SF-SPQ was developed based on data collected from 1,153 pregnant women seen in three outpatient clinics between 2010 and 2013. Sleep patterns were assessed by the Berlin Questionnaire, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and by questions regarding napping behavior. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to develop a sensitive and specific sleep scale derived from the findings. The scale ultimately included "snoring frequently," "bothersome snoring," "stopped breathing while sleeping," and "falling asleep while driving."

"These items were conceptually related to sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy, statistically intercorrelated, and/or associated with adverse outcomes. CFA factor loadings were significant and model fit was good," Dr. Agrawal wrote.

In addition to higher score on the SF-SPQ, adjusted relative risks of adverse outcomes were associated with BMI greater than 30 (adjusted relative risk, 1.55), hypertension (adjusted RR, 5.07), and screening positive on the Berlin Questionnaire (adjusted RR, 2.45).

"These data suggest that comorbid conditions such as obesity and hypertension (which are themselves a part of the Berlin Questionnaire) drive association with pregnancy outcomes. However, preeclampsia was independently associated with the SF-SPQ," Dr. Agrawal noted.

Prior studies have demonstrated that sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, but an efficient and efficacious screening tool for sleep disorders has been lacking.

The findings are important, because in the United States, preeclampsia affects up to 6% of pregnancies and is linked with other morbidities such as intrauterine growth restriction, and because studies suggest that the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can reduce the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant patients with sleep-disordered breathing.

Additional research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of the SF-SPQ for detecting women at risk, Dr. Agrawal concluded.

Dr. Agrawal reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – A four-item pregnancy-specific sleep disturbance scale proved valid as a screening tool for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy, and was associated with preeclampsia in a study of more than 1,100 women.

After adjustment for potential confounders – including sociodemographics, body mass index, and high blood pressure – a higher score on the short-form pregnancy-specific questionnaire (SF-SPQ) was significantly associated with an increase in the risk of preeclampsia (adjusted risk ratio, 1.54) Alpna Agrawal, Ph.D., of the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

"In a clinical setting, the short format and validity of SF-SPQ shown in this study suggests it may be a quick and effective method to screen women at risk for sleep-disordered breathing," Dr. Agrawal wrote.

The SF-SPQ was developed based on data collected from 1,153 pregnant women seen in three outpatient clinics between 2010 and 2013. Sleep patterns were assessed by the Berlin Questionnaire, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and by questions regarding napping behavior. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to develop a sensitive and specific sleep scale derived from the findings. The scale ultimately included "snoring frequently," "bothersome snoring," "stopped breathing while sleeping," and "falling asleep while driving."

"These items were conceptually related to sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy, statistically intercorrelated, and/or associated with adverse outcomes. CFA factor loadings were significant and model fit was good," Dr. Agrawal wrote.

In addition to higher score on the SF-SPQ, adjusted relative risks of adverse outcomes were associated with BMI greater than 30 (adjusted relative risk, 1.55), hypertension (adjusted RR, 5.07), and screening positive on the Berlin Questionnaire (adjusted RR, 2.45).

"These data suggest that comorbid conditions such as obesity and hypertension (which are themselves a part of the Berlin Questionnaire) drive association with pregnancy outcomes. However, preeclampsia was independently associated with the SF-SPQ," Dr. Agrawal noted.

Prior studies have demonstrated that sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, but an efficient and efficacious screening tool for sleep disorders has been lacking.

The findings are important, because in the United States, preeclampsia affects up to 6% of pregnancies and is linked with other morbidities such as intrauterine growth restriction, and because studies suggest that the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can reduce the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant patients with sleep-disordered breathing.

Additional research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of the SF-SPQ for detecting women at risk, Dr. Agrawal concluded.

Dr. Agrawal reported having no disclosures.

CHICAGO – A four-item pregnancy-specific sleep disturbance scale proved valid as a screening tool for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy, and was associated with preeclampsia in a study of more than 1,100 women.

After adjustment for potential confounders – including sociodemographics, body mass index, and high blood pressure – a higher score on the short-form pregnancy-specific questionnaire (SF-SPQ) was significantly associated with an increase in the risk of preeclampsia (adjusted risk ratio, 1.54) Alpna Agrawal, Ph.D., of the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

"In a clinical setting, the short format and validity of SF-SPQ shown in this study suggests it may be a quick and effective method to screen women at risk for sleep-disordered breathing," Dr. Agrawal wrote.

The SF-SPQ was developed based on data collected from 1,153 pregnant women seen in three outpatient clinics between 2010 and 2013. Sleep patterns were assessed by the Berlin Questionnaire, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and by questions regarding napping behavior. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to develop a sensitive and specific sleep scale derived from the findings. The scale ultimately included "snoring frequently," "bothersome snoring," "stopped breathing while sleeping," and "falling asleep while driving."

"These items were conceptually related to sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy, statistically intercorrelated, and/or associated with adverse outcomes. CFA factor loadings were significant and model fit was good," Dr. Agrawal wrote.

In addition to higher score on the SF-SPQ, adjusted relative risks of adverse outcomes were associated with BMI greater than 30 (adjusted relative risk, 1.55), hypertension (adjusted RR, 5.07), and screening positive on the Berlin Questionnaire (adjusted RR, 2.45).

"These data suggest that comorbid conditions such as obesity and hypertension (which are themselves a part of the Berlin Questionnaire) drive association with pregnancy outcomes. However, preeclampsia was independently associated with the SF-SPQ," Dr. Agrawal noted.

Prior studies have demonstrated that sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, but an efficient and efficacious screening tool for sleep disorders has been lacking.

The findings are important, because in the United States, preeclampsia affects up to 6% of pregnancies and is linked with other morbidities such as intrauterine growth restriction, and because studies suggest that the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can reduce the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant patients with sleep-disordered breathing.

Additional research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of the SF-SPQ for detecting women at risk, Dr. Agrawal concluded.

Dr. Agrawal reported having no disclosures.

AT THE ACOG ANNUAL CLINICAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A short pregnancy-specific sleep disturbance scale may be useful as a screening tool for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy, which is associated with preeclampsia.

Major finding: Higher SF-SPQ score was significantly associated with an increase in the risk of preeclampsia (adjusted risk ratio, 1.54).

Data source: Confirmatory factor analysis of data from 1,153 pregnant women.

Disclosures: Dr. Agrawal reported having no disclosures

Jury Finds Fault With Midwife’s Care

During her pregnancy, a Wisconsin woman received care from a nurse-midwife. In late July 2001, misoprostol was administered to induce labor. The woman was admitted to the hospital in active labor at approximately 2 pm. She was 6 cm dilated. Dilation arrested three times, and then there was a two-hour failure to dilate.

The nurse-midwife then tried putting the mother in a water-birthing tub to stimulate contractions, without success. Oxytocin was then administered. Immediately thereafter, the patient developed uterine hyperstimulation, and the fetal heart rate strip showed late decelerations, indicative of fetal distress.

Despite these abnormalities, the nurse-midwife continued increasing oxytocin throughout labor, which continued for about 12 hours. The oxytocin dose exceeded the hospital’s recommended protocols. The patient reached a point at which she was having strong contractions every 1.5 min. Full dilation was not reached until 10:38 pm.

Around midnight, the electronic fetal monitor allegedly showed an abnormal heart pattern, with decelerations with almost every contraction. The mother was allowed to continue with labor, and the fetal monitoring equipment was removed at 1:26 am so the mother could be placed in the water-birthing tub again. Nurses took the fetal heart rate during this time and recorded it as normal.

When the child was delivered at approximately 2 am, she had a heart rate of 80 beats/min; she was apneic, cyanotic, and virtually lifeless. Apgar scores were recorded as 1 at one minute and 3 at five minutes. Arterial blood gas/pH was 7.165.

An attending physician was called and arrived within 20 min. The infant was resuscitated, intubated, and transferred to another hospital. A CT scan taken at 56 hours of life was read as normal. An MRl at nine months was also read as normal.

The child was subsequently diagnosed as having cerebral palsy. She requires a walker for ambulation and has arm and leg impairments and significant cognitive deficits, necessitating 24-hour assistance.

The plaintiff claimed that if oxytocin had been discontinued, she would have reached full dilation hours earlier than she did. She also claimed that a cesarean delivery or operative vaginal delivery should have been performed when the fetal monitor indicated an abnormal heart pattern. (She contended that the “normal” heart rate recorded around this time was actually the maternal heart rate.)

The parties did not dispute that the infant had experienced a hypoxic/ischemic event but disagreed on when it occurred. The plaintiff claimed that the ischemic event occurred during delivery. The defendants claimed that it occurred in utero prior to delivery. The plaintiff also disputed the MRI findings, which the plaintiff argued showed significant brain injury.

On the next page: Outcome >>

OUTCOME

A jury found the nurse-midwife 80% at fault and the hospital 20% at fault. The jury awarded $13.5 million to the child and $100,000 to the plaintiff. An additional $110,000 in past medical expenses was added to the verdict.

COMMENT

Obstetrics/midwifery accounts for a significant percentage of malpractice cases filed and monetary damages awarded. In this case, a substantial $13.5 million verdict was awarded, with 80% of the verdict against the midwife for inappropriate use of oxytocin and failure to refer for cesarean delivery.

A detailed discussion of obstetric management is beyond the scope of this article (in part because we don’t have access to much data, including fetal heart rate tracings). However, there are a few points to consider.

First, consider surgical options when appropriate. Without doubt, operative delivery by cesarean section is overused for all the wrong reasons. Some mothers, families, and clinicians strongly desire a more natural childbirth and strive to create such an experience—forgoing traditional medications and anesthesia. Often, this is perfectly safe, reasonable, and preferable.

However, if the perinatal course is rocky, it is wise to monitor closely and adopt a collaborative approach. When prenatal screening suggests a difficult delivery, exercise caution and have a fallback plan. Known high-risk deliveries should have a team approach from the outset, with all assets available to bedside on short notice.

While operative delivery is overused, it shouldn’t be demonized either. When genuinely needed, it can be lifesaving. Some patients do not want a cesarean delivery, and both the patient and the clinician may equate operative delivery with personal failure. However, that view may present a barrier to calling for consultation when it is genuinely needed.

For natural childbirth enthusiasts, think of the surgical delivery option as sealed in a glass case. Break that glass for all the right reasons: to preserve life or avoid significant fetal morbidity. Discuss the indications for surgical management ahead of time, so the mother is not surprised by a sudden rush to the operating room, feeling frightened and out of control.

It is recognized that patients and clinicians have firmly held beliefs, and opinions are strong on this subject. Patients have a right to self-determination and to select the birthing experience that will suit them best. Yet there is tension because jurors will expect a clinician to fully communicate known risks to patients and use all available resources to safeguard the mother and fetus at all times. In this case, the jury concluded that the midwife failed to refer for cesarean delivery after about 10 hours of labor, when the fetal heart rate pattern was nonreassuring. One of the plaintiff’s expert witnesses who criticized the defendant midwife’s care was herself a highly regarded midwife.

Continued on the next page >>

Second, use oxytocin carefully, slowing or stopping it when required. While we do not have access to the fetal heart rate monitor strips in this case, we do know that the plaintiff met her burden of proof and persuaded the jurors that the midwife inappropriately increased the drug in the setting of uterine hyperstimulation, with evidence of fetal distress. It seems surprising that the allegedly “normal” pattern recorded at 1:26 am could have been the maternal heart rate—but apparently, the jurors were convinced of this.

Third, when a facility has a medication protocol, follow it unless there is good cause not to. Medication protocols can be useful to establish operating guidelines and reduce medication errors. But they can also shackle clinicians by substituting tables and algorithms for clinical judgment. Problems arise when a protocol is sidestepped, and the clinician is raked over the coals for failing to adhere. If your facility has protocols that are important to your practice, read the documentation. Learn it, know it, live it.

If you operate outside a protocol, and your case goes to trial, the expert witness defending your care will be forced to take on both the plaintiff’s allegations and your own facility’s recommendations. The plaintiff’s closing argument will include a variation of “Mr. A did not even bother to follow his hospital’s own rules.” This argument is easy for jurors to understand, and many will reach a finding of negligence based on this fact alone. If you disagree with the protocol, or it is not reflective of your actual practice, either clinician practice or the protocol must be changed. Do not routinely circumvent protocols without good reason.

Ideally, protocols should be constructed to give clinicians flexibility based on clinical judgment and patient response. If you have a role in forming a protocol, consider advocating for less rigidity and allowing for professional judgment. If the protocol is rigid, be sure that everyone understands it and that it can be strictly followed in a real world practice environment. Put plainly, don’t install a set of rules you can’t live with—it is professionally constraining and legally risky.

IN SUM

From a legal standpoint, it is not safe to completely discard surgical delivery; when needed, it is required. Patients given oxytocin must be monitored closely, and the drug should be discontinued in the setting of uterine hyperactivity with fetal distress. Follow medication protocols or change them—but whatever you do, don’t ignore them.

During her pregnancy, a Wisconsin woman received care from a nurse-midwife. In late July 2001, misoprostol was administered to induce labor. The woman was admitted to the hospital in active labor at approximately 2 pm. She was 6 cm dilated. Dilation arrested three times, and then there was a two-hour failure to dilate.

The nurse-midwife then tried putting the mother in a water-birthing tub to stimulate contractions, without success. Oxytocin was then administered. Immediately thereafter, the patient developed uterine hyperstimulation, and the fetal heart rate strip showed late decelerations, indicative of fetal distress.

Despite these abnormalities, the nurse-midwife continued increasing oxytocin throughout labor, which continued for about 12 hours. The oxytocin dose exceeded the hospital’s recommended protocols. The patient reached a point at which she was having strong contractions every 1.5 min. Full dilation was not reached until 10:38 pm.

Around midnight, the electronic fetal monitor allegedly showed an abnormal heart pattern, with decelerations with almost every contraction. The mother was allowed to continue with labor, and the fetal monitoring equipment was removed at 1:26 am so the mother could be placed in the water-birthing tub again. Nurses took the fetal heart rate during this time and recorded it as normal.

When the child was delivered at approximately 2 am, she had a heart rate of 80 beats/min; she was apneic, cyanotic, and virtually lifeless. Apgar scores were recorded as 1 at one minute and 3 at five minutes. Arterial blood gas/pH was 7.165.

An attending physician was called and arrived within 20 min. The infant was resuscitated, intubated, and transferred to another hospital. A CT scan taken at 56 hours of life was read as normal. An MRl at nine months was also read as normal.

The child was subsequently diagnosed as having cerebral palsy. She requires a walker for ambulation and has arm and leg impairments and significant cognitive deficits, necessitating 24-hour assistance.

The plaintiff claimed that if oxytocin had been discontinued, she would have reached full dilation hours earlier than she did. She also claimed that a cesarean delivery or operative vaginal delivery should have been performed when the fetal monitor indicated an abnormal heart pattern. (She contended that the “normal” heart rate recorded around this time was actually the maternal heart rate.)

The parties did not dispute that the infant had experienced a hypoxic/ischemic event but disagreed on when it occurred. The plaintiff claimed that the ischemic event occurred during delivery. The defendants claimed that it occurred in utero prior to delivery. The plaintiff also disputed the MRI findings, which the plaintiff argued showed significant brain injury.

On the next page: Outcome >>

OUTCOME

A jury found the nurse-midwife 80% at fault and the hospital 20% at fault. The jury awarded $13.5 million to the child and $100,000 to the plaintiff. An additional $110,000 in past medical expenses was added to the verdict.

COMMENT

Obstetrics/midwifery accounts for a significant percentage of malpractice cases filed and monetary damages awarded. In this case, a substantial $13.5 million verdict was awarded, with 80% of the verdict against the midwife for inappropriate use of oxytocin and failure to refer for cesarean delivery.

A detailed discussion of obstetric management is beyond the scope of this article (in part because we don’t have access to much data, including fetal heart rate tracings). However, there are a few points to consider.

First, consider surgical options when appropriate. Without doubt, operative delivery by cesarean section is overused for all the wrong reasons. Some mothers, families, and clinicians strongly desire a more natural childbirth and strive to create such an experience—forgoing traditional medications and anesthesia. Often, this is perfectly safe, reasonable, and preferable.

However, if the perinatal course is rocky, it is wise to monitor closely and adopt a collaborative approach. When prenatal screening suggests a difficult delivery, exercise caution and have a fallback plan. Known high-risk deliveries should have a team approach from the outset, with all assets available to bedside on short notice.

While operative delivery is overused, it shouldn’t be demonized either. When genuinely needed, it can be lifesaving. Some patients do not want a cesarean delivery, and both the patient and the clinician may equate operative delivery with personal failure. However, that view may present a barrier to calling for consultation when it is genuinely needed.

For natural childbirth enthusiasts, think of the surgical delivery option as sealed in a glass case. Break that glass for all the right reasons: to preserve life or avoid significant fetal morbidity. Discuss the indications for surgical management ahead of time, so the mother is not surprised by a sudden rush to the operating room, feeling frightened and out of control.

It is recognized that patients and clinicians have firmly held beliefs, and opinions are strong on this subject. Patients have a right to self-determination and to select the birthing experience that will suit them best. Yet there is tension because jurors will expect a clinician to fully communicate known risks to patients and use all available resources to safeguard the mother and fetus at all times. In this case, the jury concluded that the midwife failed to refer for cesarean delivery after about 10 hours of labor, when the fetal heart rate pattern was nonreassuring. One of the plaintiff’s expert witnesses who criticized the defendant midwife’s care was herself a highly regarded midwife.

Continued on the next page >>

Second, use oxytocin carefully, slowing or stopping it when required. While we do not have access to the fetal heart rate monitor strips in this case, we do know that the plaintiff met her burden of proof and persuaded the jurors that the midwife inappropriately increased the drug in the setting of uterine hyperstimulation, with evidence of fetal distress. It seems surprising that the allegedly “normal” pattern recorded at 1:26 am could have been the maternal heart rate—but apparently, the jurors were convinced of this.

Third, when a facility has a medication protocol, follow it unless there is good cause not to. Medication protocols can be useful to establish operating guidelines and reduce medication errors. But they can also shackle clinicians by substituting tables and algorithms for clinical judgment. Problems arise when a protocol is sidestepped, and the clinician is raked over the coals for failing to adhere. If your facility has protocols that are important to your practice, read the documentation. Learn it, know it, live it.

If you operate outside a protocol, and your case goes to trial, the expert witness defending your care will be forced to take on both the plaintiff’s allegations and your own facility’s recommendations. The plaintiff’s closing argument will include a variation of “Mr. A did not even bother to follow his hospital’s own rules.” This argument is easy for jurors to understand, and many will reach a finding of negligence based on this fact alone. If you disagree with the protocol, or it is not reflective of your actual practice, either clinician practice or the protocol must be changed. Do not routinely circumvent protocols without good reason.

Ideally, protocols should be constructed to give clinicians flexibility based on clinical judgment and patient response. If you have a role in forming a protocol, consider advocating for less rigidity and allowing for professional judgment. If the protocol is rigid, be sure that everyone understands it and that it can be strictly followed in a real world practice environment. Put plainly, don’t install a set of rules you can’t live with—it is professionally constraining and legally risky.

IN SUM

From a legal standpoint, it is not safe to completely discard surgical delivery; when needed, it is required. Patients given oxytocin must be monitored closely, and the drug should be discontinued in the setting of uterine hyperactivity with fetal distress. Follow medication protocols or change them—but whatever you do, don’t ignore them.

During her pregnancy, a Wisconsin woman received care from a nurse-midwife. In late July 2001, misoprostol was administered to induce labor. The woman was admitted to the hospital in active labor at approximately 2 pm. She was 6 cm dilated. Dilation arrested three times, and then there was a two-hour failure to dilate.

The nurse-midwife then tried putting the mother in a water-birthing tub to stimulate contractions, without success. Oxytocin was then administered. Immediately thereafter, the patient developed uterine hyperstimulation, and the fetal heart rate strip showed late decelerations, indicative of fetal distress.

Despite these abnormalities, the nurse-midwife continued increasing oxytocin throughout labor, which continued for about 12 hours. The oxytocin dose exceeded the hospital’s recommended protocols. The patient reached a point at which she was having strong contractions every 1.5 min. Full dilation was not reached until 10:38 pm.

Around midnight, the electronic fetal monitor allegedly showed an abnormal heart pattern, with decelerations with almost every contraction. The mother was allowed to continue with labor, and the fetal monitoring equipment was removed at 1:26 am so the mother could be placed in the water-birthing tub again. Nurses took the fetal heart rate during this time and recorded it as normal.

When the child was delivered at approximately 2 am, she had a heart rate of 80 beats/min; she was apneic, cyanotic, and virtually lifeless. Apgar scores were recorded as 1 at one minute and 3 at five minutes. Arterial blood gas/pH was 7.165.

An attending physician was called and arrived within 20 min. The infant was resuscitated, intubated, and transferred to another hospital. A CT scan taken at 56 hours of life was read as normal. An MRl at nine months was also read as normal.

The child was subsequently diagnosed as having cerebral palsy. She requires a walker for ambulation and has arm and leg impairments and significant cognitive deficits, necessitating 24-hour assistance.

The plaintiff claimed that if oxytocin had been discontinued, she would have reached full dilation hours earlier than she did. She also claimed that a cesarean delivery or operative vaginal delivery should have been performed when the fetal monitor indicated an abnormal heart pattern. (She contended that the “normal” heart rate recorded around this time was actually the maternal heart rate.)

The parties did not dispute that the infant had experienced a hypoxic/ischemic event but disagreed on when it occurred. The plaintiff claimed that the ischemic event occurred during delivery. The defendants claimed that it occurred in utero prior to delivery. The plaintiff also disputed the MRI findings, which the plaintiff argued showed significant brain injury.

On the next page: Outcome >>

OUTCOME

A jury found the nurse-midwife 80% at fault and the hospital 20% at fault. The jury awarded $13.5 million to the child and $100,000 to the plaintiff. An additional $110,000 in past medical expenses was added to the verdict.

COMMENT

Obstetrics/midwifery accounts for a significant percentage of malpractice cases filed and monetary damages awarded. In this case, a substantial $13.5 million verdict was awarded, with 80% of the verdict against the midwife for inappropriate use of oxytocin and failure to refer for cesarean delivery.

A detailed discussion of obstetric management is beyond the scope of this article (in part because we don’t have access to much data, including fetal heart rate tracings). However, there are a few points to consider.

First, consider surgical options when appropriate. Without doubt, operative delivery by cesarean section is overused for all the wrong reasons. Some mothers, families, and clinicians strongly desire a more natural childbirth and strive to create such an experience—forgoing traditional medications and anesthesia. Often, this is perfectly safe, reasonable, and preferable.

However, if the perinatal course is rocky, it is wise to monitor closely and adopt a collaborative approach. When prenatal screening suggests a difficult delivery, exercise caution and have a fallback plan. Known high-risk deliveries should have a team approach from the outset, with all assets available to bedside on short notice.

While operative delivery is overused, it shouldn’t be demonized either. When genuinely needed, it can be lifesaving. Some patients do not want a cesarean delivery, and both the patient and the clinician may equate operative delivery with personal failure. However, that view may present a barrier to calling for consultation when it is genuinely needed.

For natural childbirth enthusiasts, think of the surgical delivery option as sealed in a glass case. Break that glass for all the right reasons: to preserve life or avoid significant fetal morbidity. Discuss the indications for surgical management ahead of time, so the mother is not surprised by a sudden rush to the operating room, feeling frightened and out of control.

It is recognized that patients and clinicians have firmly held beliefs, and opinions are strong on this subject. Patients have a right to self-determination and to select the birthing experience that will suit them best. Yet there is tension because jurors will expect a clinician to fully communicate known risks to patients and use all available resources to safeguard the mother and fetus at all times. In this case, the jury concluded that the midwife failed to refer for cesarean delivery after about 10 hours of labor, when the fetal heart rate pattern was nonreassuring. One of the plaintiff’s expert witnesses who criticized the defendant midwife’s care was herself a highly regarded midwife.

Continued on the next page >>

Second, use oxytocin carefully, slowing or stopping it when required. While we do not have access to the fetal heart rate monitor strips in this case, we do know that the plaintiff met her burden of proof and persuaded the jurors that the midwife inappropriately increased the drug in the setting of uterine hyperstimulation, with evidence of fetal distress. It seems surprising that the allegedly “normal” pattern recorded at 1:26 am could have been the maternal heart rate—but apparently, the jurors were convinced of this.

Third, when a facility has a medication protocol, follow it unless there is good cause not to. Medication protocols can be useful to establish operating guidelines and reduce medication errors. But they can also shackle clinicians by substituting tables and algorithms for clinical judgment. Problems arise when a protocol is sidestepped, and the clinician is raked over the coals for failing to adhere. If your facility has protocols that are important to your practice, read the documentation. Learn it, know it, live it.

If you operate outside a protocol, and your case goes to trial, the expert witness defending your care will be forced to take on both the plaintiff’s allegations and your own facility’s recommendations. The plaintiff’s closing argument will include a variation of “Mr. A did not even bother to follow his hospital’s own rules.” This argument is easy for jurors to understand, and many will reach a finding of negligence based on this fact alone. If you disagree with the protocol, or it is not reflective of your actual practice, either clinician practice or the protocol must be changed. Do not routinely circumvent protocols without good reason.

Ideally, protocols should be constructed to give clinicians flexibility based on clinical judgment and patient response. If you have a role in forming a protocol, consider advocating for less rigidity and allowing for professional judgment. If the protocol is rigid, be sure that everyone understands it and that it can be strictly followed in a real world practice environment. Put plainly, don’t install a set of rules you can’t live with—it is professionally constraining and legally risky.

IN SUM

From a legal standpoint, it is not safe to completely discard surgical delivery; when needed, it is required. Patients given oxytocin must be monitored closely, and the drug should be discontinued in the setting of uterine hyperactivity with fetal distress. Follow medication protocols or change them—but whatever you do, don’t ignore them.

VIDEO: Abnormal endocrinology labs? Look beyond ‘usual suspects’

PHILADELPHIA – Psychiatric medications can affect prolactin levels, while antibodies can affect thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. Hirsutism may be the result of polycystic ovary syndrome – but it may also be caused by congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

And if that’s not confounding enough, physicians should add to the medical factors that can influence lab reports what Dr. Ellen L. Connor says is the importance of "knowing the typical ranges of the assays you are using, and what the ranges considered normal are at the [laboratory] you’re working with."

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Dr. Connor of the department of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reviews what can change prolactin levels, how to get the most clinical utility out of thyroid tests, what is the gold standard for testosterone testing in women, how best to test and interpret vitamin D levels, and what adrenal malfunctions are possible in young women. She also stresses the value of working with knowledgeable lab personnel.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

PHILADELPHIA – Psychiatric medications can affect prolactin levels, while antibodies can affect thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. Hirsutism may be the result of polycystic ovary syndrome – but it may also be caused by congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

And if that’s not confounding enough, physicians should add to the medical factors that can influence lab reports what Dr. Ellen L. Connor says is the importance of "knowing the typical ranges of the assays you are using, and what the ranges considered normal are at the [laboratory] you’re working with."

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Dr. Connor of the department of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reviews what can change prolactin levels, how to get the most clinical utility out of thyroid tests, what is the gold standard for testosterone testing in women, how best to test and interpret vitamin D levels, and what adrenal malfunctions are possible in young women. She also stresses the value of working with knowledgeable lab personnel.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

PHILADELPHIA – Psychiatric medications can affect prolactin levels, while antibodies can affect thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. Hirsutism may be the result of polycystic ovary syndrome – but it may also be caused by congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

And if that’s not confounding enough, physicians should add to the medical factors that can influence lab reports what Dr. Ellen L. Connor says is the importance of "knowing the typical ranges of the assays you are using, and what the ranges considered normal are at the [laboratory] you’re working with."

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Dr. Connor of the department of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reviews what can change prolactin levels, how to get the most clinical utility out of thyroid tests, what is the gold standard for testosterone testing in women, how best to test and interpret vitamin D levels, and what adrenal malfunctions are possible in young women. She also stresses the value of working with knowledgeable lab personnel.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NASPAG 2014

How to identify and manage cesarean-scar pregnancy

Few ObGyn clinicians have faced a patient with a cesarean-scar pregnancy (CSP). Those few were confronted with a management dilemma. Continue the gestation, which would expose the mother to an elevated risk of heavy bleeding? Or terminate the pregnancy? And if termination is the patient’s choice, what is the most effective method?

The literature contains more than 750 reports of CSP, ranging from a single sporadic case to a series of one to two dozen cases. It is impossible to make sense of the numerous treatments used in the past, which were “tested” on extremely small numbers of patients (sometimes as few as one). In this article, we formulate a management plan for the diagnosis and treatment of CSP based on an in-depth review of the published literature and our personal experience in treating more than four dozen patients with CSP.

We’re all familiar with the “epidemic” of cesarean deliveries in this country, including late consequences of cesarean such as placenta previa and morbidly adherent placenta. One of the long-term consequences of cesarean delivery—the first-trimester CSP—is less well known and documented.

Our in-depth review of 751 CSP cases found no less than 30 published therapeutic approaches.1 No consensus exists as to management guidelines. We have formulated this clinical guide, based on the literature and our experience managing CSP, for clinicians who encounter this dangerous form of pregnancy.2

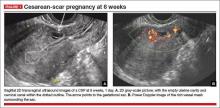

DIAGNOSIS REQUIRES TRANSVAGINAL SONOGRAPHY

Transvaginal sonography (TVS) is thought to be the best and first-line diagnostic tool, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reserved for cases in which there is a diagnostic problem.

In making a diagnosis, consider two main differential diagnoses:

- Cervical pregnancy—This type of gestation is more likely to occur in women with no history of cesarean delivery

- Spontaneous miscarriage in progress—In a number of cases, the miscarriage happened to be caught on imaging as it passed the area where the CSP usually resides. Because there is no live embryo or fetus in spontaneous miscarriage, a heartbeat cannot be documented.

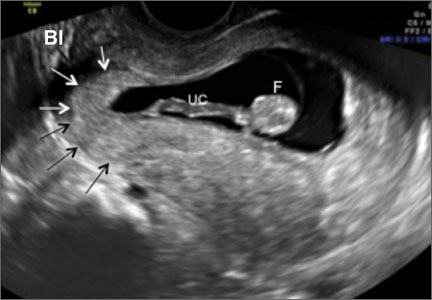

Components of diagnosis by TVS

Accurate identification of CSP depends on the following sonographic criteria:

- empty uterine cavity and cervical canal (FIGURE 1A)

- close proximity of the gestational sac and the placenta to the anterior uterine surface within the scar or niche of the previous cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1B, 2A, and 2B)

- color flow signals between the posterior bladder wall and the gestation within the placenta (FIGURES 1B, 2B, and 3B)

- abundant blood flow around the gestational sac, at times morphing into an arteriovenous malformation with a high peak systolic velocity blood flow demonstrable on pulsed Doppler.

Our analysis of 751 cases of CSP found that almost a third—30%—were misdiagnosed, contributing to a large number of treatment complications. Most of these complications could have been avoided if diagnosis had been early and correct. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the outcome seemed to be. This was true even when treatment modalities with slightly higher complication rates were used in very early gestation.

Related articles:

• Is the hCG discriminatory zone a reliable indicator of intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; February 2012)

• Can a single progesterone test distinguish viable and nonviable pregnancies accurately in women with pain or bleeding? Linda R. Chambliss, MD, MPH (Examining the Evidence; March 2013)

THOROUGH COUNSELING OF THE PATIENT IS PARAMOUNT

Once a diagnosis of CSP has been established, the patient should be counseled about her options. The presence of a live CSP requires immediate and decisive action to prevent further growth of the embryo or fetus. Literature from the past decade, particularly from the past several years, makes evidence-based counseling possible.

In general, treatment should be individualized, based on the patient’s age, number of previous cesarean deliveries, number of children, and the expertise of the clinicians managing her care. Options include:

- termination of the pregnancy

- continuation of the pregnancy with the possibility of delivering a live offspring, provided the patient understands that a morbidly adherent placenta may occur, often necessitating emergency hysterectomy.3,4

MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Most treatment regimens and combinations thereof can be classified as one of the following:

- Surgical—requiring general anesthesia and either laparotomy with excision or hysterectomy, or laparoscopic or hysteroscopic excision followed by dilation and curettage (D&C).

- Minimally invasive—involving local injection of methotrexate or potassium chloride or systemic intervention, involving a major procedure such as uterine artery embolization in combination with a less complicated one: intramuscular injection of methotrexate in a single or a multidose regimen.

A variety of simultaneous as well as sequential combination treatments also were used. More recently, an ingenious adjunct to treatment is gaining attention: insertion and inflation of a Foley balloon catheter to prevent or tamponade bleeding.

A large number of treatments described in the literature—and their different combinations—have been reported as relatively small case series. Gynecologic surgeons generally perform D&C, laparoscopy, and hysteroscopy or laparotomy as the first-line approach. Obstetricians, radiologists, and in vitro fertilization specialists usually prefer systemic, parenteral administration of methotrexate or ultrasound-guided local methotrexate (or potassium chloride) as an injection into the gestational sac. On occasion, the help of an interventional radiologist was requested to embolize the area of the CSP through the uterine arteries.

POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

In our analysis of 751 cases of CSP, we used a rigorous definition of complication, which included an immediate or delayed need for a secondary treatment for blood loss exceeding 200 mL or requiring blood transfusion. If general anesthesia or major surgery was required, we classified that need as a complication.

Utilizing these criteria, we observed an overall complication rate of 44.1% (331 of 751 cases).1

Complications occurred most often when the following treatment modalities were used alone:

- single systemic dose of methotrexate

- D&C

- uterine artery embolization.

Of the 751 cases reviewed, 21.8% resulted in major surgery or interventional radiology procedures (primary or emergency). The total planned primary (nonemergency) interventions performed were 66 (8.7%), which included 3 hysterectomies, 14 laparotomies, and 49 uterine artery embolizations or ligations. There were 98 (13.0%) emergency interventions, which included 36 hysterectomies, 40 laparotomies, and 22 uterine artery embolizations or ligations.1

Related article: Eight tools for improving obstetric patient safety and unit performance. Henry M. Lerner, MD (Professional Liability; March 2014)

NINE TREATMENTS AND THEIR COMPLICATIONS

1. Systemic, single-dose methotrexate

The usual protocols were 1 mg/kg of body weight or 50 mg/m2 of body surface area. This treatment was associated with a complication rate of 64.6%, mostly because it required a second treatment when the fetal heart beat did not cease after several days.1

We speculate that the high failure rate with this treatment may be caused by its slow action and questionable ability to stop cardiac activity and placental expansion. The expected result can take days, and all the while the gestational sac, the embryo or fetus, and its vascularity are growing. Secondary treatment has to address a larger gestation with more abundant vascularization.

2. Systemic, multidose, sequential methotrexate

In this regimen, the amounts of methotrexate injected are similar to the dose for the single-dose regimen. Two to three intramuscular injections (1 mg/kg of body weight or 50 mg/mm2 of surface area) are given at an interval of 2 or 3 days over the course of a week. Be aware of the cumulative adverse effects of this drug on the liver and bone marrow—and the fact that even multidose treatment can fail.1

We found it impossible to assess the complication rate associated with this approach because it was often used in conjunction with another “first-line” treatment or after it. However, it is clear that methotrexate can be combined with other, mostly nonsurgical treatments.

3. Suction aspiration or D&C, alone or in combination

This option requires general anesthesia. The 305 cases involving this treatment had a mean complication rate of about 62% (range, 29%–86%).1 This approach caused the greatest number of bleeding complications, necessitating a third-line treatment that almost always was surgical.

At delivery or the time of spontaneous abortion, the multilayered myometrial grid in the uterine body is able to contain bleeding vessels after placental separation. However, in CSP, the exposed vessels in the cervical scar tissue bleed because there is no muscle grid to contract and contain the profuse bleeding.

If you choose D&C or aspiration, have blood products available and a Foley balloon catheter handy! In several reports, a Foley balloon catheter was used as backup after significant bleeding occurred following curettage.5,6

In one of the series involving 45 cases treated by methotrexate followed by suction curettage, mean blood loss was significant at 707 mL (standard deviation, 642 mL; range, 100–2,000 mL), and treatment failed in three patients despite insertion of a Foley balloon catheter.

4. Uterine artery embolization, alone or in combination

This treatment requires general anesthesia. The complication rate was 47% among the 64 cases described in the literature.1 Uterine artery embolization appeared to work better when it was combined with other noninvasive treatments. It probably is not the best first-line treatment because the delay between treatment and effect allows the gestation to grow and vascularity to increase. And if uterine artery embolization fails, the clinician must contend with a larger gestation.

5. Excision by laparotomy, alone or in combination with hysteroscopy

General anesthesia is required. Of the 18 cases described in the literature, only five complications were reported—and only when used in an emergency situation.1

6. Laparoscopic excision

Again, general anesthesia is required. Fifteen of the 49 cases (30.6%) described in the literature involved complications, but only one of five cases (20%) experienced complications if hysteroscopy and laparoscopy were combined. Small numbers may not allow meaningful evaluation of the latter approach.1

7. Operative hysteroscopy, alone or in combination

General anesthesia is required. The overall complication rate for 108 cases was 13.8%. However, if hysteroscopy was combined with transabdominal ultrasound guidance (as it was in nine cases), no complications were noted. If hysteroscopy was combined with mifepristone, the complication rate was 17%.1 It appears that, when it is performed by an experienced clinician with ultrasound guidance, hysteroscopy may be a reasonable operative solution to CSP.

8. Intragestational-sac injection of methotrexate or potassium chloride, with ultrasound guidance

No anesthesia is required. This approach (FIGURE 4) had the fewest and least-involved complications. Of 83 cases, only 9 (10.8%) involved complications.

Cases performed with transabdominal sonography guidance had a slighter higher complication rate (15%) than those using TVS guidance.1

Because local injections are performed without general anesthesia and provide a final treatment by stopping heart activity, they appear to be the most effective intervention and may be especially useful when future fertility is desired.

9. Use of a Foley balloon catheter

Inserting a Foley balloon catheter and inflating it at the site of the CSP is an ingenious, relatively new approach.1,2,5–7 The catheters come with balloons of different capacity (FIGURE 5A). They can be used alone (usually in gestations of 5–7 weeks) in the hope of stopping the evolution of the pregnancy by placing pressure on a small gestational sac. Even so, this approach is almost always used in a planned fashion in conjunction with another treatment or as backup if bleeding occurs.

Our impression of the value of the balloon catheters is positive. We suggest the French-12 size 10-mL silicone balloon catheter (prices range from $2 to $20), although we used a French-14 catheter with a 30-mL balloon successfully in a case of an 8-week CSP.

Insert the catheter using real-time transabdominal sonographic guidance when the patient has a comfortably full bladder. One also can switch to TVS guidance to allow for more precise placement and assess the pressure, avoiding overinflation of the balloon (FIGURE 5B).

There is no information in the literature about how long such a catheter should be kept in place. In our experience, 24 to 48 hours is the preferred duration, with the outer end of the catheter fastened to the patient’s thigh. We also provide antibiotic coverage and reevaluate the effect in 2 days or as needed. General anesthesia is not required.

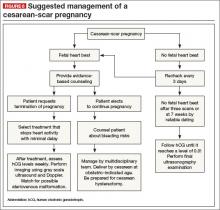

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Is there any single and effective treatment protocol? Probably not. Our management approach is presented as an algorithm (FIGURE 6).

We also offer the following guidelines:

- Do not confuse CSP with ectopic pregnancy. Such nomenclature has caused some referring physicians to simply use methotrexate protocols developed on “garden variety” tubal ectopic pregnancies, which not only failed but yielded disastrous results.

- Early diagnosis matters. TVS is the most effective and preferred diagnostic tool. Delay in the diagnosis delays treatment, increasing the possibility of complications.

- Cervical pregnancy is rare. In a patient who has had a cesarean delivery, a low chorionic sac is almost always a CSP.

- A key first step: Determine whether heart activity is present, and avoid methotrexate if no heart activity is observed.

- Counsel the patient. If heart activity is documented, provide evidence-based counseling about the patient’s options.

- Act fast. If continuation of the pregnancy is not desired, provide a reliable treatment that stops the embryonic or fetal heart beat without delay. Early treatment minimizes complications.

- Avoid single treatments unlikely to be effective, including D&C, suction curettage, single-dose intramuscular methotrexate, and uterine artery embolization applied alone.

- Keep a catheter at hand. Foley balloon tamponade to prevent or treat bleeding is a useful adjunct to have within easy reach.

- Consider combination treatments, as they may provide the best results.

- Fully inform the patient of the risks of pregnancy continuation. If a patient elects to continue the pregnancy, schedule an additional counseling session in which a more detailed overview of the anticipated clinical road is thoroughly explained.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to the Editor to: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. [published correction appears in Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(4):371–374.] Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14–29.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Santos R, Tsymbal T, Pineda G, Arslan AA. The diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):44.e1–e13.

- Ballas J, Pretorius D, Hull AD, Resnik R, Ramos GA. Identifying sonographic markers for placenta accreta in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(11):1835–1841.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Cali P, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy and early placenta accreta share a common histology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(4):383–395.

- Yu XL, Zhang N, Zuo WL. Cesarean scar pregnancy: An analysis of 100 cases [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;91(45):3186–3189.

- Jiang T, Liu G, Huang L, Ma H, Zhang S. Methotrexate therapy followed by suction curettage followed by Foley tamponade for cesarean scar pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156(2):209–211.

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(3):1–20.

Few ObGyn clinicians have faced a patient with a cesarean-scar pregnancy (CSP). Those few were confronted with a management dilemma. Continue the gestation, which would expose the mother to an elevated risk of heavy bleeding? Or terminate the pregnancy? And if termination is the patient’s choice, what is the most effective method?

The literature contains more than 750 reports of CSP, ranging from a single sporadic case to a series of one to two dozen cases. It is impossible to make sense of the numerous treatments used in the past, which were “tested” on extremely small numbers of patients (sometimes as few as one). In this article, we formulate a management plan for the diagnosis and treatment of CSP based on an in-depth review of the published literature and our personal experience in treating more than four dozen patients with CSP.

We’re all familiar with the “epidemic” of cesarean deliveries in this country, including late consequences of cesarean such as placenta previa and morbidly adherent placenta. One of the long-term consequences of cesarean delivery—the first-trimester CSP—is less well known and documented.

Our in-depth review of 751 CSP cases found no less than 30 published therapeutic approaches.1 No consensus exists as to management guidelines. We have formulated this clinical guide, based on the literature and our experience managing CSP, for clinicians who encounter this dangerous form of pregnancy.2

DIAGNOSIS REQUIRES TRANSVAGINAL SONOGRAPHY

Transvaginal sonography (TVS) is thought to be the best and first-line diagnostic tool, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reserved for cases in which there is a diagnostic problem.

In making a diagnosis, consider two main differential diagnoses:

- Cervical pregnancy—This type of gestation is more likely to occur in women with no history of cesarean delivery

- Spontaneous miscarriage in progress—In a number of cases, the miscarriage happened to be caught on imaging as it passed the area where the CSP usually resides. Because there is no live embryo or fetus in spontaneous miscarriage, a heartbeat cannot be documented.

Components of diagnosis by TVS

Accurate identification of CSP depends on the following sonographic criteria:

- empty uterine cavity and cervical canal (FIGURE 1A)

- close proximity of the gestational sac and the placenta to the anterior uterine surface within the scar or niche of the previous cesarean delivery (FIGURES 1B, 2A, and 2B)

- color flow signals between the posterior bladder wall and the gestation within the placenta (FIGURES 1B, 2B, and 3B)

- abundant blood flow around the gestational sac, at times morphing into an arteriovenous malformation with a high peak systolic velocity blood flow demonstrable on pulsed Doppler.

Our analysis of 751 cases of CSP found that almost a third—30%—were misdiagnosed, contributing to a large number of treatment complications. Most of these complications could have been avoided if diagnosis had been early and correct. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the outcome seemed to be. This was true even when treatment modalities with slightly higher complication rates were used in very early gestation.

Related articles:

• Is the hCG discriminatory zone a reliable indicator of intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; February 2012)

• Can a single progesterone test distinguish viable and nonviable pregnancies accurately in women with pain or bleeding? Linda R. Chambliss, MD, MPH (Examining the Evidence; March 2013)

THOROUGH COUNSELING OF THE PATIENT IS PARAMOUNT

Once a diagnosis of CSP has been established, the patient should be counseled about her options. The presence of a live CSP requires immediate and decisive action to prevent further growth of the embryo or fetus. Literature from the past decade, particularly from the past several years, makes evidence-based counseling possible.

In general, treatment should be individualized, based on the patient’s age, number of previous cesarean deliveries, number of children, and the expertise of the clinicians managing her care. Options include:

- termination of the pregnancy

- continuation of the pregnancy with the possibility of delivering a live offspring, provided the patient understands that a morbidly adherent placenta may occur, often necessitating emergency hysterectomy.3,4

MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Most treatment regimens and combinations thereof can be classified as one of the following:

- Surgical—requiring general anesthesia and either laparotomy with excision or hysterectomy, or laparoscopic or hysteroscopic excision followed by dilation and curettage (D&C).

- Minimally invasive—involving local injection of methotrexate or potassium chloride or systemic intervention, involving a major procedure such as uterine artery embolization in combination with a less complicated one: intramuscular injection of methotrexate in a single or a multidose regimen.

A variety of simultaneous as well as sequential combination treatments also were used. More recently, an ingenious adjunct to treatment is gaining attention: insertion and inflation of a Foley balloon catheter to prevent or tamponade bleeding.

A large number of treatments described in the literature—and their different combinations—have been reported as relatively small case series. Gynecologic surgeons generally perform D&C, laparoscopy, and hysteroscopy or laparotomy as the first-line approach. Obstetricians, radiologists, and in vitro fertilization specialists usually prefer systemic, parenteral administration of methotrexate or ultrasound-guided local methotrexate (or potassium chloride) as an injection into the gestational sac. On occasion, the help of an interventional radiologist was requested to embolize the area of the CSP through the uterine arteries.

POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

In our analysis of 751 cases of CSP, we used a rigorous definition of complication, which included an immediate or delayed need for a secondary treatment for blood loss exceeding 200 mL or requiring blood transfusion. If general anesthesia or major surgery was required, we classified that need as a complication.

Utilizing these criteria, we observed an overall complication rate of 44.1% (331 of 751 cases).1

Complications occurred most often when the following treatment modalities were used alone:

- single systemic dose of methotrexate

- D&C

- uterine artery embolization.

Of the 751 cases reviewed, 21.8% resulted in major surgery or interventional radiology procedures (primary or emergency). The total planned primary (nonemergency) interventions performed were 66 (8.7%), which included 3 hysterectomies, 14 laparotomies, and 49 uterine artery embolizations or ligations. There were 98 (13.0%) emergency interventions, which included 36 hysterectomies, 40 laparotomies, and 22 uterine artery embolizations or ligations.1

Related article: Eight tools for improving obstetric patient safety and unit performance. Henry M. Lerner, MD (Professional Liability; March 2014)

NINE TREATMENTS AND THEIR COMPLICATIONS

1. Systemic, single-dose methotrexate

The usual protocols were 1 mg/kg of body weight or 50 mg/m2 of body surface area. This treatment was associated with a complication rate of 64.6%, mostly because it required a second treatment when the fetal heart beat did not cease after several days.1

We speculate that the high failure rate with this treatment may be caused by its slow action and questionable ability to stop cardiac activity and placental expansion. The expected result can take days, and all the while the gestational sac, the embryo or fetus, and its vascularity are growing. Secondary treatment has to address a larger gestation with more abundant vascularization.

2. Systemic, multidose, sequential methotrexate

In this regimen, the amounts of methotrexate injected are similar to the dose for the single-dose regimen. Two to three intramuscular injections (1 mg/kg of body weight or 50 mg/mm2 of surface area) are given at an interval of 2 or 3 days over the course of a week. Be aware of the cumulative adverse effects of this drug on the liver and bone marrow—and the fact that even multidose treatment can fail.1

We found it impossible to assess the complication rate associated with this approach because it was often used in conjunction with another “first-line” treatment or after it. However, it is clear that methotrexate can be combined with other, mostly nonsurgical treatments.

3. Suction aspiration or D&C, alone or in combination

This option requires general anesthesia. The 305 cases involving this treatment had a mean complication rate of about 62% (range, 29%–86%).1 This approach caused the greatest number of bleeding complications, necessitating a third-line treatment that almost always was surgical.

At delivery or the time of spontaneous abortion, the multilayered myometrial grid in the uterine body is able to contain bleeding vessels after placental separation. However, in CSP, the exposed vessels in the cervical scar tissue bleed because there is no muscle grid to contract and contain the profuse bleeding.

If you choose D&C or aspiration, have blood products available and a Foley balloon catheter handy! In several reports, a Foley balloon catheter was used as backup after significant bleeding occurred following curettage.5,6

In one of the series involving 45 cases treated by methotrexate followed by suction curettage, mean blood loss was significant at 707 mL (standard deviation, 642 mL; range, 100–2,000 mL), and treatment failed in three patients despite insertion of a Foley balloon catheter.

4. Uterine artery embolization, alone or in combination

This treatment requires general anesthesia. The complication rate was 47% among the 64 cases described in the literature.1 Uterine artery embolization appeared to work better when it was combined with other noninvasive treatments. It probably is not the best first-line treatment because the delay between treatment and effect allows the gestation to grow and vascularity to increase. And if uterine artery embolization fails, the clinician must contend with a larger gestation.

5. Excision by laparotomy, alone or in combination with hysteroscopy

General anesthesia is required. Of the 18 cases described in the literature, only five complications were reported—and only when used in an emergency situation.1

6. Laparoscopic excision

Again, general anesthesia is required. Fifteen of the 49 cases (30.6%) described in the literature involved complications, but only one of five cases (20%) experienced complications if hysteroscopy and laparoscopy were combined. Small numbers may not allow meaningful evaluation of the latter approach.1

7. Operative hysteroscopy, alone or in combination

General anesthesia is required. The overall complication rate for 108 cases was 13.8%. However, if hysteroscopy was combined with transabdominal ultrasound guidance (as it was in nine cases), no complications were noted. If hysteroscopy was combined with mifepristone, the complication rate was 17%.1 It appears that, when it is performed by an experienced clinician with ultrasound guidance, hysteroscopy may be a reasonable operative solution to CSP.

8. Intragestational-sac injection of methotrexate or potassium chloride, with ultrasound guidance

No anesthesia is required. This approach (FIGURE 4) had the fewest and least-involved complications. Of 83 cases, only 9 (10.8%) involved complications.

Cases performed with transabdominal sonography guidance had a slighter higher complication rate (15%) than those using TVS guidance.1

Because local injections are performed without general anesthesia and provide a final treatment by stopping heart activity, they appear to be the most effective intervention and may be especially useful when future fertility is desired.

9. Use of a Foley balloon catheter

Inserting a Foley balloon catheter and inflating it at the site of the CSP is an ingenious, relatively new approach.1,2,5–7 The catheters come with balloons of different capacity (FIGURE 5A). They can be used alone (usually in gestations of 5–7 weeks) in the hope of stopping the evolution of the pregnancy by placing pressure on a small gestational sac. Even so, this approach is almost always used in a planned fashion in conjunction with another treatment or as backup if bleeding occurs.

Our impression of the value of the balloon catheters is positive. We suggest the French-12 size 10-mL silicone balloon catheter (prices range from $2 to $20), although we used a French-14 catheter with a 30-mL balloon successfully in a case of an 8-week CSP.

Insert the catheter using real-time transabdominal sonographic guidance when the patient has a comfortably full bladder. One also can switch to TVS guidance to allow for more precise placement and assess the pressure, avoiding overinflation of the balloon (FIGURE 5B).

There is no information in the literature about how long such a catheter should be kept in place. In our experience, 24 to 48 hours is the preferred duration, with the outer end of the catheter fastened to the patient’s thigh. We also provide antibiotic coverage and reevaluate the effect in 2 days or as needed. General anesthesia is not required.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Is there any single and effective treatment protocol? Probably not. Our management approach is presented as an algorithm (FIGURE 6).

We also offer the following guidelines:

- Do not confuse CSP with ectopic pregnancy. Such nomenclature has caused some referring physicians to simply use methotrexate protocols developed on “garden variety” tubal ectopic pregnancies, which not only failed but yielded disastrous results.

- Early diagnosis matters. TVS is the most effective and preferred diagnostic tool. Delay in the diagnosis delays treatment, increasing the possibility of complications.

- Cervical pregnancy is rare. In a patient who has had a cesarean delivery, a low chorionic sac is almost always a CSP.

- A key first step: Determine whether heart activity is present, and avoid methotrexate if no heart activity is observed.

- Counsel the patient. If heart activity is documented, provide evidence-based counseling about the patient’s options.

- Act fast. If continuation of the pregnancy is not desired, provide a reliable treatment that stops the embryonic or fetal heart beat without delay. Early treatment minimizes complications.

- Avoid single treatments unlikely to be effective, including D&C, suction curettage, single-dose intramuscular methotrexate, and uterine artery embolization applied alone.

- Keep a catheter at hand. Foley balloon tamponade to prevent or treat bleeding is a useful adjunct to have within easy reach.

- Consider combination treatments, as they may provide the best results.

- Fully inform the patient of the risks of pregnancy continuation. If a patient elects to continue the pregnancy, schedule an additional counseling session in which a more detailed overview of the anticipated clinical road is thoroughly explained.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your letter to the Editor to: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com Please include the city and state in which you practice.