User login

Brodalumab achieved primary endpoints for moderate to severe psoriasis at 52 weeks

SAN FRANCISCO– Significantly more psoriasis patients who received the investigational biologic agent brodalumab achieved a PASI 100 response compared with those who received ustekinumab, and clinical responses persisted through 52 weeks, according to data from the pivotal phase III AMAGINE-2 trial.

Brodalumab also met its co-primary endpoints (PASI 75 and sPGA 0 or 1) compared with placebo at week 12 when given at doses of either 210 or 140 mg every two weeks, Dr. Mark Lebwohl said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

But patients maintained the best responses at the higher brodalumab dose, Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chair of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, reported. “Nearly 44% of patients in this group had not a dot of psoriasis left,” he said.

The interleukin-17 (IL-17) receptor and cytokine family play a key role in the pathogenesis of plaque psoriasis. Brodalumab works by binding the IL-17 receptor, thereby blocking binding by the A, F, and A/F IL-17 cytokines. The AMAGINE-2 trial is the last of a trio of phase III studies to assess brodalumab’s safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, Dr. Lebwohl and his associates noted. The findings are consistent with those from earlier trials, they said.

For the study, the researchers enrolled 1,831 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, of whom 1,776 completed the 12-week induction phase. During induction, patients received either 210 or 140 mg brodalumab, 45 mg of ustekinumab (or 90 mg if they weighed more than 100 kg), or placebo. At week 12, patients were re-randomized to one of the brodalumab or ustekinumab arms.

Fully 44% of patients who received 210 mg brodalumab achieved total clearance of skin disease, or Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) 100 – twice the proportion of the ustekinumab group (22%; P < .001), Dr. Lebwohl said. The 210-mg brodalumab dose also achieved the highest PASI 75 response rate (86%, compared with 70% for ustekinumab, 67% for 140 mg brodalumab, and 8% for placebo), although the adjusted p-value comparing 210 mg brodalumab and ustekinumab did not reach statistical significance (P = .078), he noted. Finally, 79% of patients who received 210 mg brodalumab and 58% of those who received 140 mg brodalumab achieved clear or almost clear skin at week 12 according to the static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA), compared with only 4% of the placebo group (P < .001), he reported.

Brodalumab’s safety profile during the 12-week induction phase resembled that for previous trials, said Dr. Lebwohl. The most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and arthralgia. “But the punch line was Candida,” he said. Candidiasis affected 0.6% of patients in the placebo arm, compared with 1.4% for brodalumab-treated patients at week 12. By week 52, about 4% to 6.5% of treated patients had developed Candida infections.

Similarly small proportions of patients across all arms experienced serious side effects (1% to 2.6%) during the placebo-controlled period, noted Dr. Lebwohl. After adjusting for exposure time, rates of adverse events were similar for all groups, he said. “However, due to disparity in patient-years of exposure between treatment groups, we cannot draw conclusions about potential dose effects,” he added.

Dr. Lebwohl reported receiving research support from Amgen, which is developing brodalumab together with AstraZeneca/MedImmune.

SAN FRANCISCO– Significantly more psoriasis patients who received the investigational biologic agent brodalumab achieved a PASI 100 response compared with those who received ustekinumab, and clinical responses persisted through 52 weeks, according to data from the pivotal phase III AMAGINE-2 trial.

Brodalumab also met its co-primary endpoints (PASI 75 and sPGA 0 or 1) compared with placebo at week 12 when given at doses of either 210 or 140 mg every two weeks, Dr. Mark Lebwohl said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

But patients maintained the best responses at the higher brodalumab dose, Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chair of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, reported. “Nearly 44% of patients in this group had not a dot of psoriasis left,” he said.

The interleukin-17 (IL-17) receptor and cytokine family play a key role in the pathogenesis of plaque psoriasis. Brodalumab works by binding the IL-17 receptor, thereby blocking binding by the A, F, and A/F IL-17 cytokines. The AMAGINE-2 trial is the last of a trio of phase III studies to assess brodalumab’s safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, Dr. Lebwohl and his associates noted. The findings are consistent with those from earlier trials, they said.

For the study, the researchers enrolled 1,831 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, of whom 1,776 completed the 12-week induction phase. During induction, patients received either 210 or 140 mg brodalumab, 45 mg of ustekinumab (or 90 mg if they weighed more than 100 kg), or placebo. At week 12, patients were re-randomized to one of the brodalumab or ustekinumab arms.

Fully 44% of patients who received 210 mg brodalumab achieved total clearance of skin disease, or Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) 100 – twice the proportion of the ustekinumab group (22%; P < .001), Dr. Lebwohl said. The 210-mg brodalumab dose also achieved the highest PASI 75 response rate (86%, compared with 70% for ustekinumab, 67% for 140 mg brodalumab, and 8% for placebo), although the adjusted p-value comparing 210 mg brodalumab and ustekinumab did not reach statistical significance (P = .078), he noted. Finally, 79% of patients who received 210 mg brodalumab and 58% of those who received 140 mg brodalumab achieved clear or almost clear skin at week 12 according to the static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA), compared with only 4% of the placebo group (P < .001), he reported.

Brodalumab’s safety profile during the 12-week induction phase resembled that for previous trials, said Dr. Lebwohl. The most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and arthralgia. “But the punch line was Candida,” he said. Candidiasis affected 0.6% of patients in the placebo arm, compared with 1.4% for brodalumab-treated patients at week 12. By week 52, about 4% to 6.5% of treated patients had developed Candida infections.

Similarly small proportions of patients across all arms experienced serious side effects (1% to 2.6%) during the placebo-controlled period, noted Dr. Lebwohl. After adjusting for exposure time, rates of adverse events were similar for all groups, he said. “However, due to disparity in patient-years of exposure between treatment groups, we cannot draw conclusions about potential dose effects,” he added.

Dr. Lebwohl reported receiving research support from Amgen, which is developing brodalumab together with AstraZeneca/MedImmune.

SAN FRANCISCO– Significantly more psoriasis patients who received the investigational biologic agent brodalumab achieved a PASI 100 response compared with those who received ustekinumab, and clinical responses persisted through 52 weeks, according to data from the pivotal phase III AMAGINE-2 trial.

Brodalumab also met its co-primary endpoints (PASI 75 and sPGA 0 or 1) compared with placebo at week 12 when given at doses of either 210 or 140 mg every two weeks, Dr. Mark Lebwohl said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

But patients maintained the best responses at the higher brodalumab dose, Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chair of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, reported. “Nearly 44% of patients in this group had not a dot of psoriasis left,” he said.

The interleukin-17 (IL-17) receptor and cytokine family play a key role in the pathogenesis of plaque psoriasis. Brodalumab works by binding the IL-17 receptor, thereby blocking binding by the A, F, and A/F IL-17 cytokines. The AMAGINE-2 trial is the last of a trio of phase III studies to assess brodalumab’s safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, Dr. Lebwohl and his associates noted. The findings are consistent with those from earlier trials, they said.

For the study, the researchers enrolled 1,831 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, of whom 1,776 completed the 12-week induction phase. During induction, patients received either 210 or 140 mg brodalumab, 45 mg of ustekinumab (or 90 mg if they weighed more than 100 kg), or placebo. At week 12, patients were re-randomized to one of the brodalumab or ustekinumab arms.

Fully 44% of patients who received 210 mg brodalumab achieved total clearance of skin disease, or Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) 100 – twice the proportion of the ustekinumab group (22%; P < .001), Dr. Lebwohl said. The 210-mg brodalumab dose also achieved the highest PASI 75 response rate (86%, compared with 70% for ustekinumab, 67% for 140 mg brodalumab, and 8% for placebo), although the adjusted p-value comparing 210 mg brodalumab and ustekinumab did not reach statistical significance (P = .078), he noted. Finally, 79% of patients who received 210 mg brodalumab and 58% of those who received 140 mg brodalumab achieved clear or almost clear skin at week 12 according to the static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA), compared with only 4% of the placebo group (P < .001), he reported.

Brodalumab’s safety profile during the 12-week induction phase resembled that for previous trials, said Dr. Lebwohl. The most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and arthralgia. “But the punch line was Candida,” he said. Candidiasis affected 0.6% of patients in the placebo arm, compared with 1.4% for brodalumab-treated patients at week 12. By week 52, about 4% to 6.5% of treated patients had developed Candida infections.

Similarly small proportions of patients across all arms experienced serious side effects (1% to 2.6%) during the placebo-controlled period, noted Dr. Lebwohl. After adjusting for exposure time, rates of adverse events were similar for all groups, he said. “However, due to disparity in patient-years of exposure between treatment groups, we cannot draw conclusions about potential dose effects,” he added.

Dr. Lebwohl reported receiving research support from Amgen, which is developing brodalumab together with AstraZeneca/MedImmune.

Key clinical point: At 52 weeks, brodalumab met its PASI 100 endpoint compared with ustekinumab in the pivotal phase III AMAGINE-2 trial.

Major finding: Forty-four percent of patients who received 210 mg brodalumab achieved PASI 100 compared with 22% of the ustekinumab group (P < .001).

Data source: Randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial of brodalumab, ustekinumab, and placebo in 1,831 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Disclosures: Dr. Lebwohl reported receiving research support from Amgen, which is developing brodalumab together with AstraZeneca/MedImmune.

Halting biologics before surgery tied to flares in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis

Interrupting biologic therapy before surgery led to flares in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and did not appear to prevent postoperative complications in a small, retrospective cohort study.

“Our findings are in keeping with most of the existing literature on this topic,” said Dr. Waseem Bakkour and his associates at the University of Manchester (England). “However, it is important to acknowledge the deficiencies of our data, in particular the small data set and retrospective study design with numerous complexities associated with interpreting it” (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015 Mar. 2 [doi:10.1111/jdv.12997]).

The British Association of Dermatologists and the British Society for Rheumatology recommend stopping biologics for at least four half-lives before surgery, but the guideline is based mostly on retrospective studies of rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, the researchers said. For their study, they reviewed electronic health records from 42 patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis who underwent 77 major and minor surgical procedures during a 6-year period. Discontinuing biologic therapy before surgery was linked to a significant risk of flare of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (40% with stoppage vs. 8.7% with continuation; P = .003). For three-quarters of procedures, patients continued biologic therapy (usually etanercept, but also adalimumab and infliximab), with no apparent effect on rates of postoperative infections or delayed wound healing. About 48% of procedures required general anesthesia, and most of the rest were skin surgeries.

The findings contradict those from a larger retrospective study (Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:333-7) that linked biologic therapy before orthopedic surgery to a fourfold rise in the odds of postoperative infections, the investigators noted. “Whilst the current evidence, not surprisingly, suggests a link between stopping treatment and disease flare, it remains equivocal regarding the question of whether continuing biologic therapy perioperatively increases the risk of postsurgical complications,” they wrote.

The authors reported no funding sources. They disclosed financial and advisory relationships with many companies that manufacture biologic therapies.

Interrupting biologic therapy before surgery led to flares in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and did not appear to prevent postoperative complications in a small, retrospective cohort study.

“Our findings are in keeping with most of the existing literature on this topic,” said Dr. Waseem Bakkour and his associates at the University of Manchester (England). “However, it is important to acknowledge the deficiencies of our data, in particular the small data set and retrospective study design with numerous complexities associated with interpreting it” (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015 Mar. 2 [doi:10.1111/jdv.12997]).

The British Association of Dermatologists and the British Society for Rheumatology recommend stopping biologics for at least four half-lives before surgery, but the guideline is based mostly on retrospective studies of rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, the researchers said. For their study, they reviewed electronic health records from 42 patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis who underwent 77 major and minor surgical procedures during a 6-year period. Discontinuing biologic therapy before surgery was linked to a significant risk of flare of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (40% with stoppage vs. 8.7% with continuation; P = .003). For three-quarters of procedures, patients continued biologic therapy (usually etanercept, but also adalimumab and infliximab), with no apparent effect on rates of postoperative infections or delayed wound healing. About 48% of procedures required general anesthesia, and most of the rest were skin surgeries.

The findings contradict those from a larger retrospective study (Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:333-7) that linked biologic therapy before orthopedic surgery to a fourfold rise in the odds of postoperative infections, the investigators noted. “Whilst the current evidence, not surprisingly, suggests a link between stopping treatment and disease flare, it remains equivocal regarding the question of whether continuing biologic therapy perioperatively increases the risk of postsurgical complications,” they wrote.

The authors reported no funding sources. They disclosed financial and advisory relationships with many companies that manufacture biologic therapies.

Interrupting biologic therapy before surgery led to flares in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and did not appear to prevent postoperative complications in a small, retrospective cohort study.

“Our findings are in keeping with most of the existing literature on this topic,” said Dr. Waseem Bakkour and his associates at the University of Manchester (England). “However, it is important to acknowledge the deficiencies of our data, in particular the small data set and retrospective study design with numerous complexities associated with interpreting it” (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015 Mar. 2 [doi:10.1111/jdv.12997]).

The British Association of Dermatologists and the British Society for Rheumatology recommend stopping biologics for at least four half-lives before surgery, but the guideline is based mostly on retrospective studies of rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, the researchers said. For their study, they reviewed electronic health records from 42 patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis who underwent 77 major and minor surgical procedures during a 6-year period. Discontinuing biologic therapy before surgery was linked to a significant risk of flare of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (40% with stoppage vs. 8.7% with continuation; P = .003). For three-quarters of procedures, patients continued biologic therapy (usually etanercept, but also adalimumab and infliximab), with no apparent effect on rates of postoperative infections or delayed wound healing. About 48% of procedures required general anesthesia, and most of the rest were skin surgeries.

The findings contradict those from a larger retrospective study (Arthritis Care Res. 2006;55:333-7) that linked biologic therapy before orthopedic surgery to a fourfold rise in the odds of postoperative infections, the investigators noted. “Whilst the current evidence, not surprisingly, suggests a link between stopping treatment and disease flare, it remains equivocal regarding the question of whether continuing biologic therapy perioperatively increases the risk of postsurgical complications,” they wrote.

The authors reported no funding sources. They disclosed financial and advisory relationships with many companies that manufacture biologic therapies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY AND VENEREOLOGY

Key clinical point: Interrupting biologic therapy before surgery led to flares in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Major finding: Discontinuing biologic therapy before surgery was associated with a significant risk of flare (40% with stoppage vs. 8.7% with continuation; P = .003).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 42 patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis who underwent 77 surgical procedures.

Disclosures: The authors reported no funding sources. They disclosed financial and advisory relationships with many companies that manufacture biologic therapies.

Novel Psoriasis Therapies and Patient Outcomes, Part 1: Topical Medications

Topical therapies are a mainstay in the management of patients with mild to moderate psoriasis (Figure). Presently, US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical medications that are commercially available for use in patients with psoriasis include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 analogues, calcineurin inhibitors, retinoids, anthralin, and tar-based formulations.1 In recent years, research has furthered our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of psoriasis and has afforded the development of more targeted therapies. Novel topical medications currently in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials are discussed in this article, and a summary is provided in the Table.

AN2728 (Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor)

AN2728 (Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc) is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that blocks the inactivation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, resulting in decreased production of inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α]).2,3 In a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 clinical trial (N=35), 40% of patients treated with AN2728 ointment 5% reported improvement of more than 2 points in overall target plaque severity score versus 6% of patients treated with vehicle. In another randomized, double-blind, dose-response trial of 145 patients, those treated with AN2728 ointment 2% twice daily reported a 60% improvement versus 40% improvement in those treated with AN2728 ointment 0.5% once daily.3 In total, 3 phase 1 trials (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01258088, NCT00762658, NCT00763204) and 4 phase 2 trials (NCT01029405, NCT00755196, NCT00759161, NCT01300052) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

AS101 (Integrin Inhibitor)

AS101 (BioMAS Ltd), or ammonium trichloro (dioxoethylene-o,o') tellurate, acts as stimulator of regulatory T cells and a redox modulator inhibiting the leukocyte integrins α4β1 and α4β7 that enable CD4+ T-cell and macrophage extravasation; it also limits expression of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-17.4 A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy of AS101 cream 4% twice daily for 12 weeks was withdrawn prior to enrollment (NCT00788424).

Tofacitinib (Janus Kinase 1 and 3 Inhibitor)

Tofacitinib (formerly known as CP-690,550)(Pfizer Inc) is a selective Janus kinase (Jak) 1 and Jak3 inhibitor that limits expression of cytokines that promote inflammation (eg, IFN-γ) and inhibits helper T cells (TH17) by downregulating expression of the IL-23 receptor. Epidermal keratinocyte proliferation in psoriasis is activated by TH17 cells that release IL-17 as well as TH1 cells that release IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor. A phase 2a trial showed statistically significant improvement from baseline in the target plaque severity score for tofacitinib ointment 2% (least squares mean, −54.4%) versus vehicle (least squares mean, −41.5%).5 Two other phase 2 trials (NCT01246583, NCT00678561) assessing the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of tofacitinib ointment in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 2b study that compared 2 dose strengths of tofacitinib ointment—10 mg/g and 20 mg/g—versus placebo over a 12-week period also was completed (NCT01831466); results were not available at the time of publication.

CT327 (Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor)

CT327 (Creabilis SA) is a tyrosine kinase A (TrkA) inhibitor that affords a novel perspective in the treatment of pruritus by shifting the focus to sensory neurons. In a phase 2b study of 160 patients, a 60% change in the visual analog scale was noted at 8 weeks in the treatment group versus 21% in the placebo group.6 Two other phase 2 studies have been completed, one with a cream formulation of pegylated K252a (NCT00995969) and another with an ointment formulation (NCT01465282); results were not available at the time of publication.

DPS-101 (Vitamin D Analogue)

DPS-101 (Dermipsor Ltd) is a combination of calcipotriol and niacinamide. Calcipotriol is a vitamin D3 analogue that increases IL-10 expression while decreasing IL-8 expression.7 It curbs epidermal keratinocyte proliferation by limiting the expression of polo-like kinase 2 and early growth response-1.8 It also may induce keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Niacinamide is the amide of vitamin B3 and inhibits proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8.10 In a dose-response phase 2b trial of 168 patients, DPS-101 demonstrated better results than either calcipotriol or niacinamide alone.11

IDP-118 (Proprietary Steroid and Retinoid Combination)

IDP-118 (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc) is a combination of halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01% (a topical corticosteroid) and tazar-otene 0.045% (a selective topical retinoid) in a lotion formulation. In isolation, tazarotene is as effective as a mid to highly potent corticosteroid, but irritation may limit its tolerability. The use of combination treatments of mid to highly potent corticosteroids and tazarotene has shown enhanced tolerability and therapeutic efficacy.12 Ongoing studies include a phase 1 trial and a phase 2 trial to evaluate low- and high-strength preparations of IDP-118, respectively (NCT01670513). Another phase 2 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of IDP-118 lotion (HP 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045%) versus IDP-118 monad HP 0.01% lotion, IDP-118 monad tazar-otene 0.045% lotion, and placebo has been completed (NCT02045277); results were not available at the time of publication.

Ruxolitinib (Jak1 and Jak2 Inhibitor)

Ruxolitinib (formerly known as INCB18424)(Incyte Corporation) is a selective Jak1 and Jak2 inhibitor. A phase 2 trial of ruxolitinib showed a 53% decline in the score for mean total lesions in patients treated with ruxolitinib phosphate cream 1% (P=.033) versus 54% in those treated with ruxolitinib phosphate cream 1.5% (P=.056) and 32% in those treated with placebo.13 Three other phase 2 studies (NCT00617994, NCT00820950, NCT00778700) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

LAS41004 (Proprietary Steroid and Retinoid Combination)

LAS41004 (Almirall, SA) is an ointment containing the corticosteroid betamethasone dipropionate and the retinoid bexarotene that is being evaluated for treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis. Five phase 2 studies (NCT01119339, NCT01283698, NCT01360944, NCT02111499, NCT01462643) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2a study (NCT02180464) with a left-right design assessing clinical response to LAS41004 versus control in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis was actively recruiting at the time of publication.

LEO 80190 (Vitamin D3 Analogue and Steroid Combination)

LEO 80190 (LEO Pharma) is a combination of the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol and the corticosteroid hydrocortisone. It was developed as a treatment for sensitive areas such as the face and intertriginous regions. A randomized, investigator-blind, phase 3 trial (NCT00640822) of LEO 80190 ointment versus tacalcitol ointment and placebo once daily for 8 weeks demonstrated controlled disease of the face in 56.8% (183/322) of patients in the LEO 80190 group, 46.4% (147/317) in the tacalcitol group, and 36.3% (37/102) in the placebo group.14 Another phase 2 study (NCT00704262) and 2 phase 3 studies (NCT00691002, NCT01007591) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

LEO 90100 (Vitamin D Analogue and Steroid Combination)

LEO 90100 (LEO Pharma) contains the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol and the corticosteroid betamethasone. Three phase 2 studies (NCT01347255, NCT01536886, NCT01536938) and a phase 3 study (NCT01866163) examining the efficacy and safety of various vehicles and formulations of LEO 90100 have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. Another phase 3 study (NCT02132936) is ongoing but not recruiting participants. Other completed studies whose results were not yet available include a phase 1 pharmacodynamic study (NCT01946386), a phase 1 study that used patch testing to assess the degree of skin irritation and sensitization associated with LEO 90100 (NCT01935869), and a phase 2 study examining the impact of LEO 90100 on calcium metabolism and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (NCT01600222).

M518101 (Vitamin D Analogue)

M518101 (Maruho Co, Ltd) is a novel topical vitamin D3 analogue. Phase 1 (NCT01844973) and phase 2 (NCT01301157, NCT00884169) trials evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of M518101 have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 3 study (NCT01989429) assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of M518101 according to changes in the modified psoriasis area and severity index over an 8-week treatment period also has been completed; results were not yet available. Three phase 3 studies assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of M518101 are ongoing: one is currently closed to recruitment (NCT01908595) and 2 are actively recruiting participants at the time of publication (NCT01878461, NCT01873677).

MOL4239 and MOL4249 (Phosphorylated Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Inhibitors)

MOL4239 (Moleculin, LLC) is a novel topical agent for use in mild to moderate psoriasis that acts via phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3) inhibition.15 The p-STAT3 protein has increased expression in psoriasis.16 A phase 2 trial of MOL4239 ointment (NCT01826201) has been completed, showing a greater mean (standard deviation) change in the psoriasis severity score in lesions treated at 28 days with MOL4239 ointment 10% (−1.9 [1.45]) versus lesions treated with placebo ointment (−1.5 [1.87]).17

MOL4249 (Moleculin, LLC) is more potent than MOL4239 with better lipid solubility. In the MOL4249 subset of a placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2a study of 16 patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, 10% (1/10) of patients experienced complete clearance of psoriatic plaques, 30% (3/10) of patients experienced 75% or greater improvement, and 50% (5/10) of patients experienced 50% or greater improvement compared to 17% (1/6) in the placebo group. Currently, a phase 2a contralateral study, a phase 2b psoriasis area and severity index trial, and a phase 3 pivotal trial are planned, according to the manufacturer.18

MQX-5902 (Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitor)

MQX-5902 (MediQuest Therapeutics) is a topical preparation of methotrexate for the treatment of fingernail psoriasis. Methotrexate is a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor and antimetabolite that inhibits folic acid metabolism, thereby disrupting DNA synthesis.19 A phase 2b dose-ranging trial (NCT00666354) was designed to assess the therapeutic efficacy and safety of MQX-5902 delivered via a proprietary drug delivery formulation in fingernail psoriasis; the outcome of this trial was not available at the time of publication.

PH-10 (Xanthine Dye)

PH-10 (Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, Inc) is a topical aqueous hydrogel derived from rose bengal disodium that may be beneficial in treating skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis and mild to moderate psoriasis. Rose bengal disodium is a hydrophilic xanthine dye with diagnostic utility in ophthalmology and gastroenterology as well as projected use as a melanoma treatment as demonstrated in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials of PV-10 (Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, Inc).20 Two phase 2 studies assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of PH-10 in psoriasis (NCT01247818, NCT00941278) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

STF115469 (Vitamin D Analogue)

STF115469 (GlaxoSmithKline) is a calcipotriene foam. At the time of publication, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial (NCT01582932) of this vitamin D3 analogue with a projected enrollment of 180 participants was actively recruiting patients aged 2 to 11 years with mild to moderate plaque psoriasis to study the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of STF115469, as well as its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

WBI-1001 (Proprietary Product)

WBI-1001 (Welichem Biotech Inc), or 2-isopropyl-5-[(E)-2-phenylethenyl] benzene-1, 3-diol, is a novel proprietary agent that inhibits proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IFN-γ, TNF-α). A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 1 trial (NCT00830817) assessing the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of WBI-1001 has been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. Another randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial (NCT01098721) evaluating its efficacy and safety according to the physician’s global assessment demonstrated a therapeutic benefit of 62.8% in patients treated with WBI-1001 cream 1% versus 13.0% in those treated with a placebo after a 12-week treatment period (P<.0001).21 WBI-1001 may offer a novel approach in the treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis.

Conclusion

Enhanced knowledge of the underlying pathogeneses of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has identified new therapeutic targets and enabled the development of exciting novel treatments for these conditions. The topical agents currently in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials show promise in enhancing the way physicians treat psoriasis. There is hope for more individualized treatment regimens with improved tolerability and better safety profiles with increased therapeutic efficacy. As our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of psoriasis continues to deepen, it will afford the development of even more innovative therapeutics for use in the management of psoriasis.

1. Mason A, Mason J, Cork M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: an abridged Cochrane systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:799-807.

2. Nazarian R, Weinberg JM. AN-2728, a PDE4 inhibitor for the potential topical treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1236-1242.

3. Moustafa F, Feldman SR. A review of phosphodiesterase-inhibition and the potential role for phosphodiesterase 4-inhibitors in clinical dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22608.

4. Halpert G, Sredni B. The effect of the novel tellurium compound AS101 on autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1230-1235.

5. Ports WC, Khan S, Lan S, et al. A randomized phase 2a efficacy and safety trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:137-145.

6. Yosipovitch G, Roblin D, Traversa S, et al. A novel topical targeted anti-pruritic treatment in phase 2b development for chronic pruritus. Paper presented at: 72nd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 21-25, 2014; Denver, CO.

7. Kang S, Yi S, Griffiths CE, et al. Calcipotriene-induced improvement in psoriasis is associated with reduced interleukin-8 and increased interleukin-10 levels within lesions. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:77-83.

8. Kristl J, Slanc P, Krasna M, et al. Calcipotriol affects keratinocyte proliferation by decreasing expression of early growth response-1 and polo-like kinase-2. Pharm Res. 2008;25:521-529.

9. Tiberio R, Bozzo C, Pertusi G, et al. Calcipotriol induces apoptosis in psoriatic keratinocytes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e972-e974.

10. Luger T, Seite S, Humbert P, et al. Recommendations for adjunctive basic skin care in patients with psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:194-200.

11. Dermipsor reports good results in DPS-101 Phase IIb study for plaque psoriasis [press release]. Evaluate Web site. http://www.evaluategroup.com/Universal/View.aspx?type=Story&id=250042. Published October 15, 2007. Accessed February 13, 2015.

12. Rivera AM, Hsu S. Topical halobetasol propionate in the treatment of plaque psoriasis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:311-316.

13. Punwani N, Scherle P, Flores R, et al. Preliminary clinical activity of a topical JAK1/2 inhibitor in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:658-664.

14. Efficacy and safety of calcipotriol plus hydrocortisone ointment compared with tacalcitol ointment in patients with psoriasis on the face and skin folds (NCT00640822). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00640822?term=NCT00640822&rank=1. Updated October 21, 2013. Accessed May 30, 2014.

15. Product candidates: targeting p-STAT3 for improved psoriasis treatment. Moleculin Web site. http://moleculin.com/product-candidates/mol4239. Accessed February 13, 2015.

16. Chowdhari S, Saini N. hsa-miR-4516 mediated downregulation of STAT3/CDK6/UBE2N plays a role in PUVA induced apoptosis in keratinocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:1630-1638.

17. Paired psoriasis lesion, comparative, study to evaluate MOL4239 in psoriasis (NCT01826201). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01826201?term=NCT01826201&rank=1§=X01256#all. Updated December 22, 2014. Accessed February 25, 2015.

18. Clinical development pipeline. Moleculin Web site. http://moleculin.com/clinical-trials/psoriasis-trials. Accessed February 13, 2015.

19. de la Brassinne M, Nikkels A. Psoriasis: state of the art 2013. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:433-441.

20. Ross MI. Intralesional therapy with PV-10 (Rose Bengal) for in-transit melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:314-319.

21. Bissonnette R, Bolduc C, Maari C, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical WBI-1001 in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis: results from a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase II trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1516-1521.

Topical therapies are a mainstay in the management of patients with mild to moderate psoriasis (Figure). Presently, US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical medications that are commercially available for use in patients with psoriasis include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 analogues, calcineurin inhibitors, retinoids, anthralin, and tar-based formulations.1 In recent years, research has furthered our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of psoriasis and has afforded the development of more targeted therapies. Novel topical medications currently in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials are discussed in this article, and a summary is provided in the Table.

AN2728 (Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor)

AN2728 (Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc) is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that blocks the inactivation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, resulting in decreased production of inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α]).2,3 In a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 clinical trial (N=35), 40% of patients treated with AN2728 ointment 5% reported improvement of more than 2 points in overall target plaque severity score versus 6% of patients treated with vehicle. In another randomized, double-blind, dose-response trial of 145 patients, those treated with AN2728 ointment 2% twice daily reported a 60% improvement versus 40% improvement in those treated with AN2728 ointment 0.5% once daily.3 In total, 3 phase 1 trials (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01258088, NCT00762658, NCT00763204) and 4 phase 2 trials (NCT01029405, NCT00755196, NCT00759161, NCT01300052) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

AS101 (Integrin Inhibitor)

AS101 (BioMAS Ltd), or ammonium trichloro (dioxoethylene-o,o') tellurate, acts as stimulator of regulatory T cells and a redox modulator inhibiting the leukocyte integrins α4β1 and α4β7 that enable CD4+ T-cell and macrophage extravasation; it also limits expression of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-17.4 A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy of AS101 cream 4% twice daily for 12 weeks was withdrawn prior to enrollment (NCT00788424).

Tofacitinib (Janus Kinase 1 and 3 Inhibitor)

Tofacitinib (formerly known as CP-690,550)(Pfizer Inc) is a selective Janus kinase (Jak) 1 and Jak3 inhibitor that limits expression of cytokines that promote inflammation (eg, IFN-γ) and inhibits helper T cells (TH17) by downregulating expression of the IL-23 receptor. Epidermal keratinocyte proliferation in psoriasis is activated by TH17 cells that release IL-17 as well as TH1 cells that release IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor. A phase 2a trial showed statistically significant improvement from baseline in the target plaque severity score for tofacitinib ointment 2% (least squares mean, −54.4%) versus vehicle (least squares mean, −41.5%).5 Two other phase 2 trials (NCT01246583, NCT00678561) assessing the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of tofacitinib ointment in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 2b study that compared 2 dose strengths of tofacitinib ointment—10 mg/g and 20 mg/g—versus placebo over a 12-week period also was completed (NCT01831466); results were not available at the time of publication.

CT327 (Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor)

CT327 (Creabilis SA) is a tyrosine kinase A (TrkA) inhibitor that affords a novel perspective in the treatment of pruritus by shifting the focus to sensory neurons. In a phase 2b study of 160 patients, a 60% change in the visual analog scale was noted at 8 weeks in the treatment group versus 21% in the placebo group.6 Two other phase 2 studies have been completed, one with a cream formulation of pegylated K252a (NCT00995969) and another with an ointment formulation (NCT01465282); results were not available at the time of publication.

DPS-101 (Vitamin D Analogue)

DPS-101 (Dermipsor Ltd) is a combination of calcipotriol and niacinamide. Calcipotriol is a vitamin D3 analogue that increases IL-10 expression while decreasing IL-8 expression.7 It curbs epidermal keratinocyte proliferation by limiting the expression of polo-like kinase 2 and early growth response-1.8 It also may induce keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Niacinamide is the amide of vitamin B3 and inhibits proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8.10 In a dose-response phase 2b trial of 168 patients, DPS-101 demonstrated better results than either calcipotriol or niacinamide alone.11

IDP-118 (Proprietary Steroid and Retinoid Combination)

IDP-118 (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc) is a combination of halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01% (a topical corticosteroid) and tazar-otene 0.045% (a selective topical retinoid) in a lotion formulation. In isolation, tazarotene is as effective as a mid to highly potent corticosteroid, but irritation may limit its tolerability. The use of combination treatments of mid to highly potent corticosteroids and tazarotene has shown enhanced tolerability and therapeutic efficacy.12 Ongoing studies include a phase 1 trial and a phase 2 trial to evaluate low- and high-strength preparations of IDP-118, respectively (NCT01670513). Another phase 2 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of IDP-118 lotion (HP 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045%) versus IDP-118 monad HP 0.01% lotion, IDP-118 monad tazar-otene 0.045% lotion, and placebo has been completed (NCT02045277); results were not available at the time of publication.

Ruxolitinib (Jak1 and Jak2 Inhibitor)

Ruxolitinib (formerly known as INCB18424)(Incyte Corporation) is a selective Jak1 and Jak2 inhibitor. A phase 2 trial of ruxolitinib showed a 53% decline in the score for mean total lesions in patients treated with ruxolitinib phosphate cream 1% (P=.033) versus 54% in those treated with ruxolitinib phosphate cream 1.5% (P=.056) and 32% in those treated with placebo.13 Three other phase 2 studies (NCT00617994, NCT00820950, NCT00778700) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

LAS41004 (Proprietary Steroid and Retinoid Combination)

LAS41004 (Almirall, SA) is an ointment containing the corticosteroid betamethasone dipropionate and the retinoid bexarotene that is being evaluated for treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis. Five phase 2 studies (NCT01119339, NCT01283698, NCT01360944, NCT02111499, NCT01462643) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2a study (NCT02180464) with a left-right design assessing clinical response to LAS41004 versus control in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis was actively recruiting at the time of publication.

LEO 80190 (Vitamin D3 Analogue and Steroid Combination)

LEO 80190 (LEO Pharma) is a combination of the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol and the corticosteroid hydrocortisone. It was developed as a treatment for sensitive areas such as the face and intertriginous regions. A randomized, investigator-blind, phase 3 trial (NCT00640822) of LEO 80190 ointment versus tacalcitol ointment and placebo once daily for 8 weeks demonstrated controlled disease of the face in 56.8% (183/322) of patients in the LEO 80190 group, 46.4% (147/317) in the tacalcitol group, and 36.3% (37/102) in the placebo group.14 Another phase 2 study (NCT00704262) and 2 phase 3 studies (NCT00691002, NCT01007591) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

LEO 90100 (Vitamin D Analogue and Steroid Combination)

LEO 90100 (LEO Pharma) contains the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol and the corticosteroid betamethasone. Three phase 2 studies (NCT01347255, NCT01536886, NCT01536938) and a phase 3 study (NCT01866163) examining the efficacy and safety of various vehicles and formulations of LEO 90100 have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. Another phase 3 study (NCT02132936) is ongoing but not recruiting participants. Other completed studies whose results were not yet available include a phase 1 pharmacodynamic study (NCT01946386), a phase 1 study that used patch testing to assess the degree of skin irritation and sensitization associated with LEO 90100 (NCT01935869), and a phase 2 study examining the impact of LEO 90100 on calcium metabolism and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (NCT01600222).

M518101 (Vitamin D Analogue)

M518101 (Maruho Co, Ltd) is a novel topical vitamin D3 analogue. Phase 1 (NCT01844973) and phase 2 (NCT01301157, NCT00884169) trials evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of M518101 have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 3 study (NCT01989429) assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of M518101 according to changes in the modified psoriasis area and severity index over an 8-week treatment period also has been completed; results were not yet available. Three phase 3 studies assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of M518101 are ongoing: one is currently closed to recruitment (NCT01908595) and 2 are actively recruiting participants at the time of publication (NCT01878461, NCT01873677).

MOL4239 and MOL4249 (Phosphorylated Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Inhibitors)

MOL4239 (Moleculin, LLC) is a novel topical agent for use in mild to moderate psoriasis that acts via phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3) inhibition.15 The p-STAT3 protein has increased expression in psoriasis.16 A phase 2 trial of MOL4239 ointment (NCT01826201) has been completed, showing a greater mean (standard deviation) change in the psoriasis severity score in lesions treated at 28 days with MOL4239 ointment 10% (−1.9 [1.45]) versus lesions treated with placebo ointment (−1.5 [1.87]).17

MOL4249 (Moleculin, LLC) is more potent than MOL4239 with better lipid solubility. In the MOL4249 subset of a placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2a study of 16 patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, 10% (1/10) of patients experienced complete clearance of psoriatic plaques, 30% (3/10) of patients experienced 75% or greater improvement, and 50% (5/10) of patients experienced 50% or greater improvement compared to 17% (1/6) in the placebo group. Currently, a phase 2a contralateral study, a phase 2b psoriasis area and severity index trial, and a phase 3 pivotal trial are planned, according to the manufacturer.18

MQX-5902 (Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitor)

MQX-5902 (MediQuest Therapeutics) is a topical preparation of methotrexate for the treatment of fingernail psoriasis. Methotrexate is a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor and antimetabolite that inhibits folic acid metabolism, thereby disrupting DNA synthesis.19 A phase 2b dose-ranging trial (NCT00666354) was designed to assess the therapeutic efficacy and safety of MQX-5902 delivered via a proprietary drug delivery formulation in fingernail psoriasis; the outcome of this trial was not available at the time of publication.

PH-10 (Xanthine Dye)

PH-10 (Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, Inc) is a topical aqueous hydrogel derived from rose bengal disodium that may be beneficial in treating skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis and mild to moderate psoriasis. Rose bengal disodium is a hydrophilic xanthine dye with diagnostic utility in ophthalmology and gastroenterology as well as projected use as a melanoma treatment as demonstrated in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials of PV-10 (Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, Inc).20 Two phase 2 studies assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of PH-10 in psoriasis (NCT01247818, NCT00941278) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

STF115469 (Vitamin D Analogue)

STF115469 (GlaxoSmithKline) is a calcipotriene foam. At the time of publication, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial (NCT01582932) of this vitamin D3 analogue with a projected enrollment of 180 participants was actively recruiting patients aged 2 to 11 years with mild to moderate plaque psoriasis to study the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of STF115469, as well as its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

WBI-1001 (Proprietary Product)

WBI-1001 (Welichem Biotech Inc), or 2-isopropyl-5-[(E)-2-phenylethenyl] benzene-1, 3-diol, is a novel proprietary agent that inhibits proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IFN-γ, TNF-α). A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 1 trial (NCT00830817) assessing the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of WBI-1001 has been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. Another randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial (NCT01098721) evaluating its efficacy and safety according to the physician’s global assessment demonstrated a therapeutic benefit of 62.8% in patients treated with WBI-1001 cream 1% versus 13.0% in those treated with a placebo after a 12-week treatment period (P<.0001).21 WBI-1001 may offer a novel approach in the treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis.

Conclusion

Enhanced knowledge of the underlying pathogeneses of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has identified new therapeutic targets and enabled the development of exciting novel treatments for these conditions. The topical agents currently in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials show promise in enhancing the way physicians treat psoriasis. There is hope for more individualized treatment regimens with improved tolerability and better safety profiles with increased therapeutic efficacy. As our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of psoriasis continues to deepen, it will afford the development of even more innovative therapeutics for use in the management of psoriasis.

Topical therapies are a mainstay in the management of patients with mild to moderate psoriasis (Figure). Presently, US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical medications that are commercially available for use in patients with psoriasis include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 analogues, calcineurin inhibitors, retinoids, anthralin, and tar-based formulations.1 In recent years, research has furthered our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of psoriasis and has afforded the development of more targeted therapies. Novel topical medications currently in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials are discussed in this article, and a summary is provided in the Table.

AN2728 (Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor)

AN2728 (Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc) is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that blocks the inactivation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, resulting in decreased production of inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α]).2,3 In a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 clinical trial (N=35), 40% of patients treated with AN2728 ointment 5% reported improvement of more than 2 points in overall target plaque severity score versus 6% of patients treated with vehicle. In another randomized, double-blind, dose-response trial of 145 patients, those treated with AN2728 ointment 2% twice daily reported a 60% improvement versus 40% improvement in those treated with AN2728 ointment 0.5% once daily.3 In total, 3 phase 1 trials (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01258088, NCT00762658, NCT00763204) and 4 phase 2 trials (NCT01029405, NCT00755196, NCT00759161, NCT01300052) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

AS101 (Integrin Inhibitor)

AS101 (BioMAS Ltd), or ammonium trichloro (dioxoethylene-o,o') tellurate, acts as stimulator of regulatory T cells and a redox modulator inhibiting the leukocyte integrins α4β1 and α4β7 that enable CD4+ T-cell and macrophage extravasation; it also limits expression of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-17.4 A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy of AS101 cream 4% twice daily for 12 weeks was withdrawn prior to enrollment (NCT00788424).

Tofacitinib (Janus Kinase 1 and 3 Inhibitor)

Tofacitinib (formerly known as CP-690,550)(Pfizer Inc) is a selective Janus kinase (Jak) 1 and Jak3 inhibitor that limits expression of cytokines that promote inflammation (eg, IFN-γ) and inhibits helper T cells (TH17) by downregulating expression of the IL-23 receptor. Epidermal keratinocyte proliferation in psoriasis is activated by TH17 cells that release IL-17 as well as TH1 cells that release IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor. A phase 2a trial showed statistically significant improvement from baseline in the target plaque severity score for tofacitinib ointment 2% (least squares mean, −54.4%) versus vehicle (least squares mean, −41.5%).5 Two other phase 2 trials (NCT01246583, NCT00678561) assessing the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of tofacitinib ointment in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 2b study that compared 2 dose strengths of tofacitinib ointment—10 mg/g and 20 mg/g—versus placebo over a 12-week period also was completed (NCT01831466); results were not available at the time of publication.

CT327 (Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor)

CT327 (Creabilis SA) is a tyrosine kinase A (TrkA) inhibitor that affords a novel perspective in the treatment of pruritus by shifting the focus to sensory neurons. In a phase 2b study of 160 patients, a 60% change in the visual analog scale was noted at 8 weeks in the treatment group versus 21% in the placebo group.6 Two other phase 2 studies have been completed, one with a cream formulation of pegylated K252a (NCT00995969) and another with an ointment formulation (NCT01465282); results were not available at the time of publication.

DPS-101 (Vitamin D Analogue)

DPS-101 (Dermipsor Ltd) is a combination of calcipotriol and niacinamide. Calcipotriol is a vitamin D3 analogue that increases IL-10 expression while decreasing IL-8 expression.7 It curbs epidermal keratinocyte proliferation by limiting the expression of polo-like kinase 2 and early growth response-1.8 It also may induce keratinocyte apoptosis.9 Niacinamide is the amide of vitamin B3 and inhibits proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8.10 In a dose-response phase 2b trial of 168 patients, DPS-101 demonstrated better results than either calcipotriol or niacinamide alone.11

IDP-118 (Proprietary Steroid and Retinoid Combination)

IDP-118 (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc) is a combination of halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01% (a topical corticosteroid) and tazar-otene 0.045% (a selective topical retinoid) in a lotion formulation. In isolation, tazarotene is as effective as a mid to highly potent corticosteroid, but irritation may limit its tolerability. The use of combination treatments of mid to highly potent corticosteroids and tazarotene has shown enhanced tolerability and therapeutic efficacy.12 Ongoing studies include a phase 1 trial and a phase 2 trial to evaluate low- and high-strength preparations of IDP-118, respectively (NCT01670513). Another phase 2 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of IDP-118 lotion (HP 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045%) versus IDP-118 monad HP 0.01% lotion, IDP-118 monad tazar-otene 0.045% lotion, and placebo has been completed (NCT02045277); results were not available at the time of publication.

Ruxolitinib (Jak1 and Jak2 Inhibitor)

Ruxolitinib (formerly known as INCB18424)(Incyte Corporation) is a selective Jak1 and Jak2 inhibitor. A phase 2 trial of ruxolitinib showed a 53% decline in the score for mean total lesions in patients treated with ruxolitinib phosphate cream 1% (P=.033) versus 54% in those treated with ruxolitinib phosphate cream 1.5% (P=.056) and 32% in those treated with placebo.13 Three other phase 2 studies (NCT00617994, NCT00820950, NCT00778700) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

LAS41004 (Proprietary Steroid and Retinoid Combination)

LAS41004 (Almirall, SA) is an ointment containing the corticosteroid betamethasone dipropionate and the retinoid bexarotene that is being evaluated for treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis. Five phase 2 studies (NCT01119339, NCT01283698, NCT01360944, NCT02111499, NCT01462643) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2a study (NCT02180464) with a left-right design assessing clinical response to LAS41004 versus control in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis was actively recruiting at the time of publication.

LEO 80190 (Vitamin D3 Analogue and Steroid Combination)

LEO 80190 (LEO Pharma) is a combination of the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol and the corticosteroid hydrocortisone. It was developed as a treatment for sensitive areas such as the face and intertriginous regions. A randomized, investigator-blind, phase 3 trial (NCT00640822) of LEO 80190 ointment versus tacalcitol ointment and placebo once daily for 8 weeks demonstrated controlled disease of the face in 56.8% (183/322) of patients in the LEO 80190 group, 46.4% (147/317) in the tacalcitol group, and 36.3% (37/102) in the placebo group.14 Another phase 2 study (NCT00704262) and 2 phase 3 studies (NCT00691002, NCT01007591) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

LEO 90100 (Vitamin D Analogue and Steroid Combination)

LEO 90100 (LEO Pharma) contains the vitamin D3 analogue calcipotriol and the corticosteroid betamethasone. Three phase 2 studies (NCT01347255, NCT01536886, NCT01536938) and a phase 3 study (NCT01866163) examining the efficacy and safety of various vehicles and formulations of LEO 90100 have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. Another phase 3 study (NCT02132936) is ongoing but not recruiting participants. Other completed studies whose results were not yet available include a phase 1 pharmacodynamic study (NCT01946386), a phase 1 study that used patch testing to assess the degree of skin irritation and sensitization associated with LEO 90100 (NCT01935869), and a phase 2 study examining the impact of LEO 90100 on calcium metabolism and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (NCT01600222).

M518101 (Vitamin D Analogue)

M518101 (Maruho Co, Ltd) is a novel topical vitamin D3 analogue. Phase 1 (NCT01844973) and phase 2 (NCT01301157, NCT00884169) trials evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of M518101 have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 3 study (NCT01989429) assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of M518101 according to changes in the modified psoriasis area and severity index over an 8-week treatment period also has been completed; results were not yet available. Three phase 3 studies assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of M518101 are ongoing: one is currently closed to recruitment (NCT01908595) and 2 are actively recruiting participants at the time of publication (NCT01878461, NCT01873677).

MOL4239 and MOL4249 (Phosphorylated Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Inhibitors)

MOL4239 (Moleculin, LLC) is a novel topical agent for use in mild to moderate psoriasis that acts via phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (p-STAT3) inhibition.15 The p-STAT3 protein has increased expression in psoriasis.16 A phase 2 trial of MOL4239 ointment (NCT01826201) has been completed, showing a greater mean (standard deviation) change in the psoriasis severity score in lesions treated at 28 days with MOL4239 ointment 10% (−1.9 [1.45]) versus lesions treated with placebo ointment (−1.5 [1.87]).17

MOL4249 (Moleculin, LLC) is more potent than MOL4239 with better lipid solubility. In the MOL4249 subset of a placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2a study of 16 patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, 10% (1/10) of patients experienced complete clearance of psoriatic plaques, 30% (3/10) of patients experienced 75% or greater improvement, and 50% (5/10) of patients experienced 50% or greater improvement compared to 17% (1/6) in the placebo group. Currently, a phase 2a contralateral study, a phase 2b psoriasis area and severity index trial, and a phase 3 pivotal trial are planned, according to the manufacturer.18

MQX-5902 (Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitor)

MQX-5902 (MediQuest Therapeutics) is a topical preparation of methotrexate for the treatment of fingernail psoriasis. Methotrexate is a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor and antimetabolite that inhibits folic acid metabolism, thereby disrupting DNA synthesis.19 A phase 2b dose-ranging trial (NCT00666354) was designed to assess the therapeutic efficacy and safety of MQX-5902 delivered via a proprietary drug delivery formulation in fingernail psoriasis; the outcome of this trial was not available at the time of publication.

PH-10 (Xanthine Dye)

PH-10 (Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, Inc) is a topical aqueous hydrogel derived from rose bengal disodium that may be beneficial in treating skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis and mild to moderate psoriasis. Rose bengal disodium is a hydrophilic xanthine dye with diagnostic utility in ophthalmology and gastroenterology as well as projected use as a melanoma treatment as demonstrated in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials of PV-10 (Provectus Biopharmaceuticals, Inc).20 Two phase 2 studies assessing the safety and therapeutic efficacy of PH-10 in psoriasis (NCT01247818, NCT00941278) have been completed; results were not available at the time of publication.

STF115469 (Vitamin D Analogue)

STF115469 (GlaxoSmithKline) is a calcipotriene foam. At the time of publication, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial (NCT01582932) of this vitamin D3 analogue with a projected enrollment of 180 participants was actively recruiting patients aged 2 to 11 years with mild to moderate plaque psoriasis to study the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of STF115469, as well as its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

WBI-1001 (Proprietary Product)

WBI-1001 (Welichem Biotech Inc), or 2-isopropyl-5-[(E)-2-phenylethenyl] benzene-1, 3-diol, is a novel proprietary agent that inhibits proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IFN-γ, TNF-α). A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 1 trial (NCT00830817) assessing the efficacy, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of WBI-1001 has been completed; results were not available at the time of publication. Another randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial (NCT01098721) evaluating its efficacy and safety according to the physician’s global assessment demonstrated a therapeutic benefit of 62.8% in patients treated with WBI-1001 cream 1% versus 13.0% in those treated with a placebo after a 12-week treatment period (P<.0001).21 WBI-1001 may offer a novel approach in the treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis.

Conclusion

Enhanced knowledge of the underlying pathogeneses of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has identified new therapeutic targets and enabled the development of exciting novel treatments for these conditions. The topical agents currently in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials show promise in enhancing the way physicians treat psoriasis. There is hope for more individualized treatment regimens with improved tolerability and better safety profiles with increased therapeutic efficacy. As our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of psoriasis continues to deepen, it will afford the development of even more innovative therapeutics for use in the management of psoriasis.

1. Mason A, Mason J, Cork M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: an abridged Cochrane systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:799-807.

2. Nazarian R, Weinberg JM. AN-2728, a PDE4 inhibitor for the potential topical treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1236-1242.

3. Moustafa F, Feldman SR. A review of phosphodiesterase-inhibition and the potential role for phosphodiesterase 4-inhibitors in clinical dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22608.

4. Halpert G, Sredni B. The effect of the novel tellurium compound AS101 on autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1230-1235.

5. Ports WC, Khan S, Lan S, et al. A randomized phase 2a efficacy and safety trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:137-145.

6. Yosipovitch G, Roblin D, Traversa S, et al. A novel topical targeted anti-pruritic treatment in phase 2b development for chronic pruritus. Paper presented at: 72nd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 21-25, 2014; Denver, CO.

7. Kang S, Yi S, Griffiths CE, et al. Calcipotriene-induced improvement in psoriasis is associated with reduced interleukin-8 and increased interleukin-10 levels within lesions. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:77-83.

8. Kristl J, Slanc P, Krasna M, et al. Calcipotriol affects keratinocyte proliferation by decreasing expression of early growth response-1 and polo-like kinase-2. Pharm Res. 2008;25:521-529.

9. Tiberio R, Bozzo C, Pertusi G, et al. Calcipotriol induces apoptosis in psoriatic keratinocytes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e972-e974.

10. Luger T, Seite S, Humbert P, et al. Recommendations for adjunctive basic skin care in patients with psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:194-200.

11. Dermipsor reports good results in DPS-101 Phase IIb study for plaque psoriasis [press release]. Evaluate Web site. http://www.evaluategroup.com/Universal/View.aspx?type=Story&id=250042. Published October 15, 2007. Accessed February 13, 2015.

12. Rivera AM, Hsu S. Topical halobetasol propionate in the treatment of plaque psoriasis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:311-316.

13. Punwani N, Scherle P, Flores R, et al. Preliminary clinical activity of a topical JAK1/2 inhibitor in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:658-664.

14. Efficacy and safety of calcipotriol plus hydrocortisone ointment compared with tacalcitol ointment in patients with psoriasis on the face and skin folds (NCT00640822). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00640822?term=NCT00640822&rank=1. Updated October 21, 2013. Accessed May 30, 2014.

15. Product candidates: targeting p-STAT3 for improved psoriasis treatment. Moleculin Web site. http://moleculin.com/product-candidates/mol4239. Accessed February 13, 2015.

16. Chowdhari S, Saini N. hsa-miR-4516 mediated downregulation of STAT3/CDK6/UBE2N plays a role in PUVA induced apoptosis in keratinocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:1630-1638.

17. Paired psoriasis lesion, comparative, study to evaluate MOL4239 in psoriasis (NCT01826201). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01826201?term=NCT01826201&rank=1§=X01256#all. Updated December 22, 2014. Accessed February 25, 2015.

18. Clinical development pipeline. Moleculin Web site. http://moleculin.com/clinical-trials/psoriasis-trials. Accessed February 13, 2015.

19. de la Brassinne M, Nikkels A. Psoriasis: state of the art 2013. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:433-441.

20. Ross MI. Intralesional therapy with PV-10 (Rose Bengal) for in-transit melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:314-319.

21. Bissonnette R, Bolduc C, Maari C, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical WBI-1001 in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis: results from a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase II trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1516-1521.

1. Mason A, Mason J, Cork M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: an abridged Cochrane systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:799-807.

2. Nazarian R, Weinberg JM. AN-2728, a PDE4 inhibitor for the potential topical treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1236-1242.

3. Moustafa F, Feldman SR. A review of phosphodiesterase-inhibition and the potential role for phosphodiesterase 4-inhibitors in clinical dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22608.

4. Halpert G, Sredni B. The effect of the novel tellurium compound AS101 on autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1230-1235.

5. Ports WC, Khan S, Lan S, et al. A randomized phase 2a efficacy and safety trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:137-145.

6. Yosipovitch G, Roblin D, Traversa S, et al. A novel topical targeted anti-pruritic treatment in phase 2b development for chronic pruritus. Paper presented at: 72nd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 21-25, 2014; Denver, CO.

7. Kang S, Yi S, Griffiths CE, et al. Calcipotriene-induced improvement in psoriasis is associated with reduced interleukin-8 and increased interleukin-10 levels within lesions. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:77-83.

8. Kristl J, Slanc P, Krasna M, et al. Calcipotriol affects keratinocyte proliferation by decreasing expression of early growth response-1 and polo-like kinase-2. Pharm Res. 2008;25:521-529.

9. Tiberio R, Bozzo C, Pertusi G, et al. Calcipotriol induces apoptosis in psoriatic keratinocytes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e972-e974.

10. Luger T, Seite S, Humbert P, et al. Recommendations for adjunctive basic skin care in patients with psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:194-200.

11. Dermipsor reports good results in DPS-101 Phase IIb study for plaque psoriasis [press release]. Evaluate Web site. http://www.evaluategroup.com/Universal/View.aspx?type=Story&id=250042. Published October 15, 2007. Accessed February 13, 2015.

12. Rivera AM, Hsu S. Topical halobetasol propionate in the treatment of plaque psoriasis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:311-316.

13. Punwani N, Scherle P, Flores R, et al. Preliminary clinical activity of a topical JAK1/2 inhibitor in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:658-664.

14. Efficacy and safety of calcipotriol plus hydrocortisone ointment compared with tacalcitol ointment in patients with psoriasis on the face and skin folds (NCT00640822). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00640822?term=NCT00640822&rank=1. Updated October 21, 2013. Accessed May 30, 2014.

15. Product candidates: targeting p-STAT3 for improved psoriasis treatment. Moleculin Web site. http://moleculin.com/product-candidates/mol4239. Accessed February 13, 2015.

16. Chowdhari S, Saini N. hsa-miR-4516 mediated downregulation of STAT3/CDK6/UBE2N plays a role in PUVA induced apoptosis in keratinocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:1630-1638.

17. Paired psoriasis lesion, comparative, study to evaluate MOL4239 in psoriasis (NCT01826201). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01826201?term=NCT01826201&rank=1§=X01256#all. Updated December 22, 2014. Accessed February 25, 2015.

18. Clinical development pipeline. Moleculin Web site. http://moleculin.com/clinical-trials/psoriasis-trials. Accessed February 13, 2015.

19. de la Brassinne M, Nikkels A. Psoriasis: state of the art 2013. Acta Clin Belg. 2013;68:433-441.

20. Ross MI. Intralesional therapy with PV-10 (Rose Bengal) for in-transit melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:314-319.

21. Bissonnette R, Bolduc C, Maari C, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical WBI-1001 in patients with mild to moderate psoriasis: results from a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase II trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1516-1521.

Practice Points

- Topical therapies are the cornerstone of treating patients with mild to moderate psoriasis. Commercially available medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with psoriasis include corticosteroids, vitamin D3 analogues, calcineurin inhibitors, retinoids, anthralin, and tar-based formulations.

- Recent developments in our understanding of inflammatory mediators and the underlying pathogenesis of psoriasis have revealed new potential therapeutic targets, leading to the discovery of many promising treatments.

- Novel topical therapies currently in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis may offer hope to patients who have reported a suboptimal therapeutic response to conventional treatments.

New Systemic Therapies for Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting 1% to 8% of the world population, depending on the country.1 Psoriasis can greatly impact quality of life in affected individuals, even in those with limited body surface involvement.2 Studies have demonstrated a high degree of psychological distress associated with psoriasis, leading to depression and poor self-esteem.3

Over the last decade, our improved understanding of the autoimmune inflammatory pathways and the associated changing concepts in psoriasis pathogenesis have led to the development of biological drugs targeting specific components of effector immune mechanisms, and these biological drugs have revolutionized the treatment of psoriasis.4 Although response rates of these biological agents are greater compared to those of conventional systemic drugs,5 current biological drugs fail to demonstrate efficacy in some patients or lose their efficacy over time. In addition to the high costs associated with these drugs, these limitations have driven a continued search for alternative therapies.

Helper T cells (TH17) and the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17 have been shown to play a key role in the pathophysiology of psoriasis, bridging innate and adaptive immune responses. IL-17 is involved in the modulation of proinflammatory cytokines, hematopoietic growth factors, antimicrobial peptides, and chemokines. Increased TH17 activity and high levels of IL-17 have been found in psoriatic plaques, and increased levels of TH17 are found in the plasma of psoriasis patients.6 Increased IL-17 induces neutrophilia, inflammation, and angiogenesis.7 Other cytokines that are highly upregulated in involved skin are tumor necrosis factor a (TNF-α), IL-23, IL-22, and IL-21.8 IL-23 is involved in regulating TH17 cells and is a potent activator of keratinocyte proliferation.9 Blockade of IL-12/23 causes downregulation of TH17 and TH22 cell responses.10 As IL-17 has a key role in protecting skin and mucous membranes from bacterial and fungal infections, IL-17 inhibition can potentially interfere with the inflammatory cascade. However, available data suggest that sufficient residual IL-17 activity remains to maintain immunity against infections.11

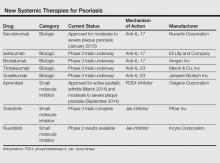

Currently approved biological agents for psoriasis target proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, or the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. A number of novel targeted therapies including biologics as well as small molecule inhibitors targeting various cytokines and molecules involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis are currently in different stages of development (Table). These drugs include 3 IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab); 2 IL-23 blockers (tildrakizumab and guselkumab); and small molecule inhibitors that target the kinase pathway including apremilast (a phosphodiesterase 4 [PDE4] inhibitor), as well as tofacitinib, baricitinib, and ruxolitinib (Janus kinase [Jak] inhibitors). Small molecule inhibitors can be administered orally and are less expensive to produce than biological agents. This article reviews available data on these new systemic agents in the pipeline.

Novel Biologics

Secukinumab

Secukinumab is a fully human monoclonal IgG1k antibody that selectively binds and neutralizes IL-17A.12 It is the first of the IL-17 antibodies to receive approval for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. In 2 phase 3, double-blind, 52-week trials—ERASURE (Efficacy of Response and Safety of Two Fixed Secukinumab Regimens in Psoriasis) and FIXTURE (Full Year Investigative Examination of Secukinumab vs Etanercept Using Two Dosing Regimens to Determine Efficacy in Psoriasis)—participants were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous secukinumab at doses of 300 mg (n=245 and n=327, respectively) or 150 mg (n=245 and n=327, respectively) once weekly for 5 weeks then every 4 weeks, or placebo (n=248 and n=326, respectively); in the FIXTURE study only, an etanercept group (n=326) was given a 50-mg dose twice weekly for 12 weeks then once weekly.13

In the ERASURE study, the proportion of participants showing a reduction of 75% or more in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score from baseline to week 12 was 81.6% with secukinumab 300 mg, 71.6% with secukinumab 150 mg, and 4.5% with placebo.13 Secondary end point results demonstrated the proportion of participants showing a 90% reduction in PASI score was 59.2% with secukinumab 300 mg and 39.1% with secukinumab 150 mg, which were both superior to placebo (1.2%). The proportion of participants who met the criteria for 100% reduction in PASI score at week 12 also was greater with each secukinumab dose than with placebo.13

In the FIXTURE study, the proportion of participants showing a reduction of 75% or more from baseline in PASI score at week 12 was 77.1% with secukinumab 300 mg, 67.0% with secukinumab 150 mg, 44.0% with etanercept, and 4.9% with placebo.13 Secondary end point results demonstrated the proportion of participants showing a 90% reduction in PASI score was 54.2% with secukinumab 300 mg, 41.9% with secukinumab 150 mg, 20.7% with etanercept, and 1.5% with placebo. The speed of response, which was assessed as the median time to a 50% reduction in mean PASI score from baseline, was significantly shorter with both doses of secukinumab (3.0 weeks and 3.9 weeks, respectively) than with etanercept (7.0 weeks)(P<.001 for both).13