User login

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Does UVB Phototherapy Cause Skin Cancer?

Myth: UVB phototherapy causes skin cancer

Phototherapy is a common treatment modality for psoriasis patients that can be used in the physician’s office or psoriasis clinic or at home. Options include UVB phototherapy (broadband and narrowband), which slows the growth of affected skin cells; psoralen plus UVA (PUVA), which slows excessive skin cell growth; and excimer laser therapy, which targets select areas of the skin affected by mild to moderate psoriasis and is particularly useful for scalp psoriasis. Each of these therapies may be combined with other topical and/or systemic psoriasis treatments. The effects of UV light on the skin and the connection to skin cancer is widely known. Therefore, patient education on the risk for skin cancer with phototherapy is essential.

Evidence suggests that UVB phototherapy remains a safe treatment modality. In a 2005 analysis of prospective and retrospective studies on skin cancer risk from UVB phototherapy, 11 studies (10 concerning psoriasis patients) were reviewed and the researchers concluded that all studies eventually showed no increased skin cancer risk with UVB phototherapy. One of the PUVA cohort studies examined genital skin cancers and found an increased rate of genital tumors associated with UVB phototherapy.

Another analysis to define the long-term carcinogenic risk for narrowband UVB treatment found that there was no association between narrowband UVB exposure alone (without PUVA) and any skin cancer. For patients treated with narrowband UVB and PUVA, there was a small increase in basal cell carcinomas.

Dermatologists should monitor psoriasis patients for self-administered treatment with tanning beds. Based on a questionnaire sent to approximately 14,000 subscribers of National Psoriasis Foundation emails, 62% of 617 tanners started tanning to treat psoriasis; they were more likely to have received medical phototherapy and had more severe psoriasis. Approximately 30% of these patients indicated that they used tanning as a self-treatment for psoriasis because of the inconvenience and cost of UV light treatment in a physician’s office as well as treatment failure of other therapies prescribed by the physician. “Our results imply that tanning bed usage among psoriasis sufferers is widespread and linked with tanning addiction,” reported Felton et al. “Practitioners should be particularly vigilant to the possibility of tanning bed usage in at-risk patients.” These patients may be at increased risk for skin cancer. Problematic tanning behaviors may be seen in younger female patients diagnosed with psoriasis at an early age as well as patients with severe psoriasis who were previously prescribed phototherapy treatment.

Expert Commentary on next page

Expert Commentary

UVB phototherapy is an effective therapy that does not increase the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), according to the 2 analyses mentioned above. When I discuss the risks and benefits of UVB phototherapy with psoriasis patients, I do say that there is a theoretical increased risk for NMSC but that the 2005 study mentioned above does not indicate an increased risk. However, UVB phototherapy and cyclosporine should not be combined, as this combination does increase the risk for NMSC.

Psoralen plus UVA definitely will increase the risk for NMSC, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. However, in this age of the biologics, PUVA use has fallen out of favor, partly due to the increased risk for NMSC, and many patients will not encounter dermatology practices that still use PUVA.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

Hearn RM, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, et al. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:931-935.

Lee E, Koo J, Berger T. UVB phototherapy and skin cancer risk: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:355-360.

Phototherapy. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/phototherapy . Accessed October 4, 2016.

Myth: UVB phototherapy causes skin cancer

Phototherapy is a common treatment modality for psoriasis patients that can be used in the physician’s office or psoriasis clinic or at home. Options include UVB phototherapy (broadband and narrowband), which slows the growth of affected skin cells; psoralen plus UVA (PUVA), which slows excessive skin cell growth; and excimer laser therapy, which targets select areas of the skin affected by mild to moderate psoriasis and is particularly useful for scalp psoriasis. Each of these therapies may be combined with other topical and/or systemic psoriasis treatments. The effects of UV light on the skin and the connection to skin cancer is widely known. Therefore, patient education on the risk for skin cancer with phototherapy is essential.

Evidence suggests that UVB phototherapy remains a safe treatment modality. In a 2005 analysis of prospective and retrospective studies on skin cancer risk from UVB phototherapy, 11 studies (10 concerning psoriasis patients) were reviewed and the researchers concluded that all studies eventually showed no increased skin cancer risk with UVB phototherapy. One of the PUVA cohort studies examined genital skin cancers and found an increased rate of genital tumors associated with UVB phototherapy.

Another analysis to define the long-term carcinogenic risk for narrowband UVB treatment found that there was no association between narrowband UVB exposure alone (without PUVA) and any skin cancer. For patients treated with narrowband UVB and PUVA, there was a small increase in basal cell carcinomas.

Dermatologists should monitor psoriasis patients for self-administered treatment with tanning beds. Based on a questionnaire sent to approximately 14,000 subscribers of National Psoriasis Foundation emails, 62% of 617 tanners started tanning to treat psoriasis; they were more likely to have received medical phototherapy and had more severe psoriasis. Approximately 30% of these patients indicated that they used tanning as a self-treatment for psoriasis because of the inconvenience and cost of UV light treatment in a physician’s office as well as treatment failure of other therapies prescribed by the physician. “Our results imply that tanning bed usage among psoriasis sufferers is widespread and linked with tanning addiction,” reported Felton et al. “Practitioners should be particularly vigilant to the possibility of tanning bed usage in at-risk patients.” These patients may be at increased risk for skin cancer. Problematic tanning behaviors may be seen in younger female patients diagnosed with psoriasis at an early age as well as patients with severe psoriasis who were previously prescribed phototherapy treatment.

Expert Commentary on next page

Expert Commentary

UVB phototherapy is an effective therapy that does not increase the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), according to the 2 analyses mentioned above. When I discuss the risks and benefits of UVB phototherapy with psoriasis patients, I do say that there is a theoretical increased risk for NMSC but that the 2005 study mentioned above does not indicate an increased risk. However, UVB phototherapy and cyclosporine should not be combined, as this combination does increase the risk for NMSC.

Psoralen plus UVA definitely will increase the risk for NMSC, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. However, in this age of the biologics, PUVA use has fallen out of favor, partly due to the increased risk for NMSC, and many patients will not encounter dermatology practices that still use PUVA.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Myth: UVB phototherapy causes skin cancer

Phototherapy is a common treatment modality for psoriasis patients that can be used in the physician’s office or psoriasis clinic or at home. Options include UVB phototherapy (broadband and narrowband), which slows the growth of affected skin cells; psoralen plus UVA (PUVA), which slows excessive skin cell growth; and excimer laser therapy, which targets select areas of the skin affected by mild to moderate psoriasis and is particularly useful for scalp psoriasis. Each of these therapies may be combined with other topical and/or systemic psoriasis treatments. The effects of UV light on the skin and the connection to skin cancer is widely known. Therefore, patient education on the risk for skin cancer with phototherapy is essential.

Evidence suggests that UVB phototherapy remains a safe treatment modality. In a 2005 analysis of prospective and retrospective studies on skin cancer risk from UVB phototherapy, 11 studies (10 concerning psoriasis patients) were reviewed and the researchers concluded that all studies eventually showed no increased skin cancer risk with UVB phototherapy. One of the PUVA cohort studies examined genital skin cancers and found an increased rate of genital tumors associated with UVB phototherapy.

Another analysis to define the long-term carcinogenic risk for narrowband UVB treatment found that there was no association between narrowband UVB exposure alone (without PUVA) and any skin cancer. For patients treated with narrowband UVB and PUVA, there was a small increase in basal cell carcinomas.

Dermatologists should monitor psoriasis patients for self-administered treatment with tanning beds. Based on a questionnaire sent to approximately 14,000 subscribers of National Psoriasis Foundation emails, 62% of 617 tanners started tanning to treat psoriasis; they were more likely to have received medical phototherapy and had more severe psoriasis. Approximately 30% of these patients indicated that they used tanning as a self-treatment for psoriasis because of the inconvenience and cost of UV light treatment in a physician’s office as well as treatment failure of other therapies prescribed by the physician. “Our results imply that tanning bed usage among psoriasis sufferers is widespread and linked with tanning addiction,” reported Felton et al. “Practitioners should be particularly vigilant to the possibility of tanning bed usage in at-risk patients.” These patients may be at increased risk for skin cancer. Problematic tanning behaviors may be seen in younger female patients diagnosed with psoriasis at an early age as well as patients with severe psoriasis who were previously prescribed phototherapy treatment.

Expert Commentary on next page

Expert Commentary

UVB phototherapy is an effective therapy that does not increase the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), according to the 2 analyses mentioned above. When I discuss the risks and benefits of UVB phototherapy with psoriasis patients, I do say that there is a theoretical increased risk for NMSC but that the 2005 study mentioned above does not indicate an increased risk. However, UVB phototherapy and cyclosporine should not be combined, as this combination does increase the risk for NMSC.

Psoralen plus UVA definitely will increase the risk for NMSC, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. However, in this age of the biologics, PUVA use has fallen out of favor, partly due to the increased risk for NMSC, and many patients will not encounter dermatology practices that still use PUVA.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

Hearn RM, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, et al. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:931-935.

Lee E, Koo J, Berger T. UVB phototherapy and skin cancer risk: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:355-360.

Phototherapy. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/phototherapy . Accessed October 4, 2016.

Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

Hearn RM, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, et al. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:931-935.

Lee E, Koo J, Berger T. UVB phototherapy and skin cancer risk: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:355-360.

Phototherapy. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/phototherapy . Accessed October 4, 2016.

Presenting Treatment Safety Data: Subjective Interpretations of Objective Information

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

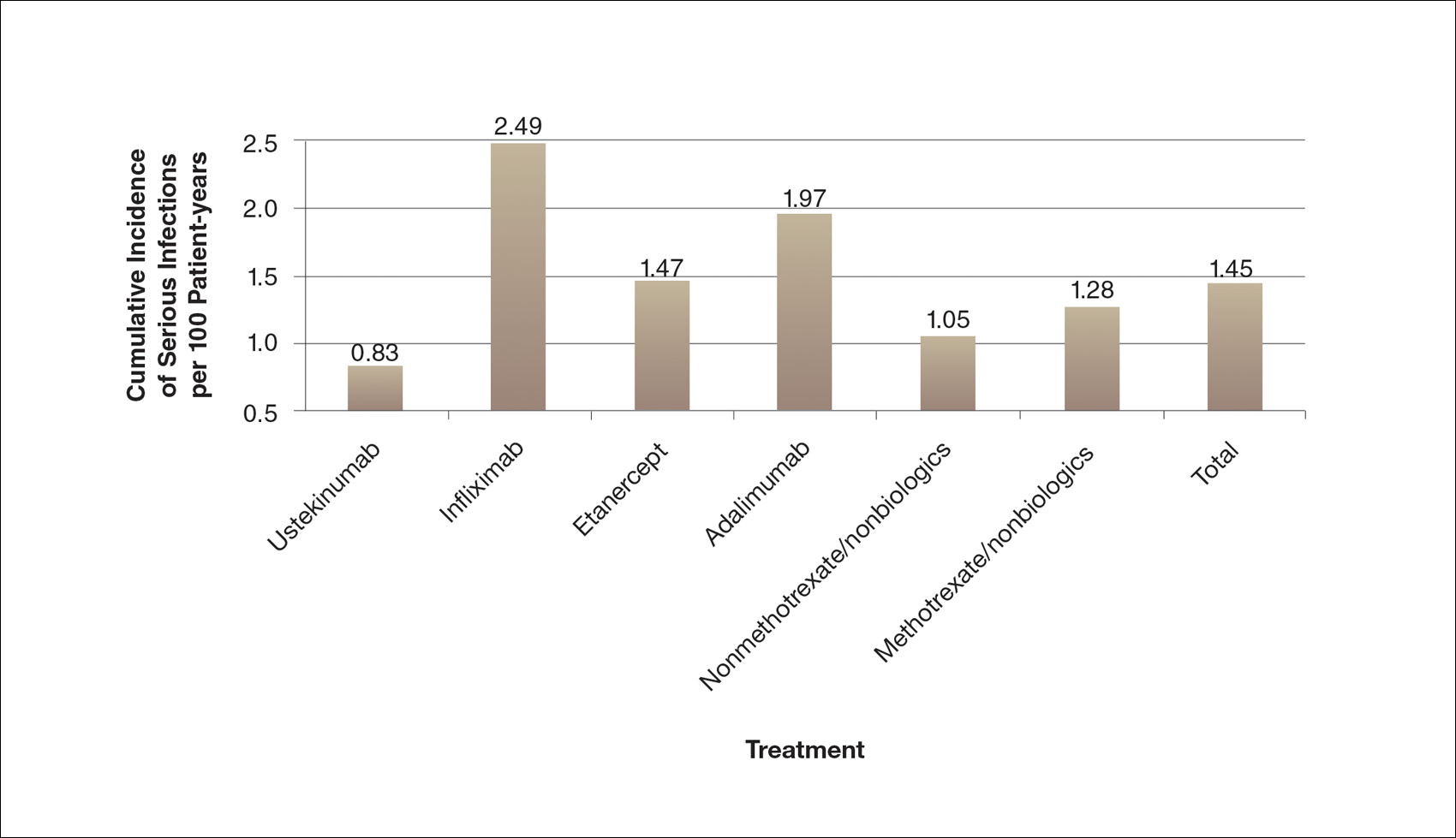

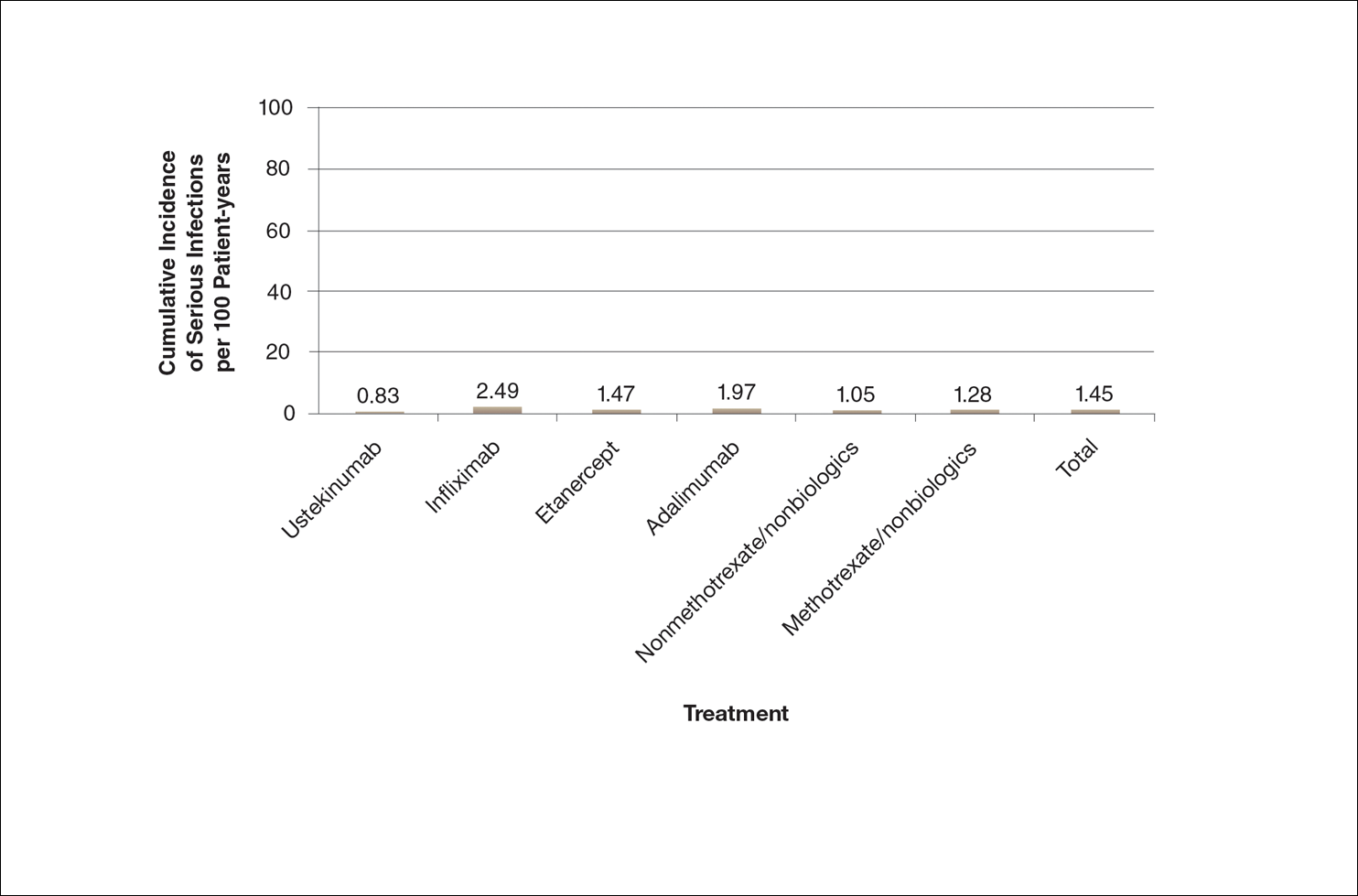

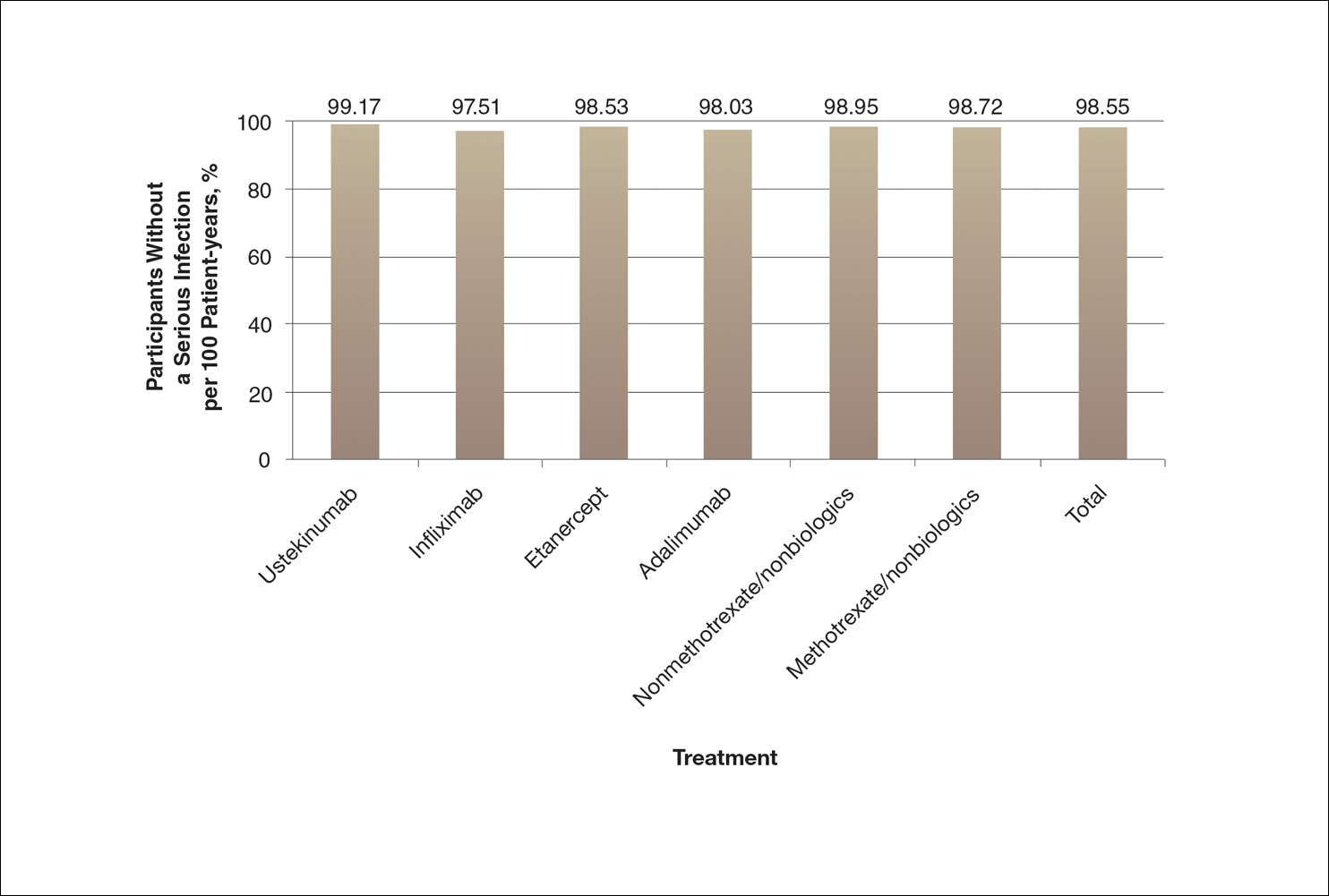

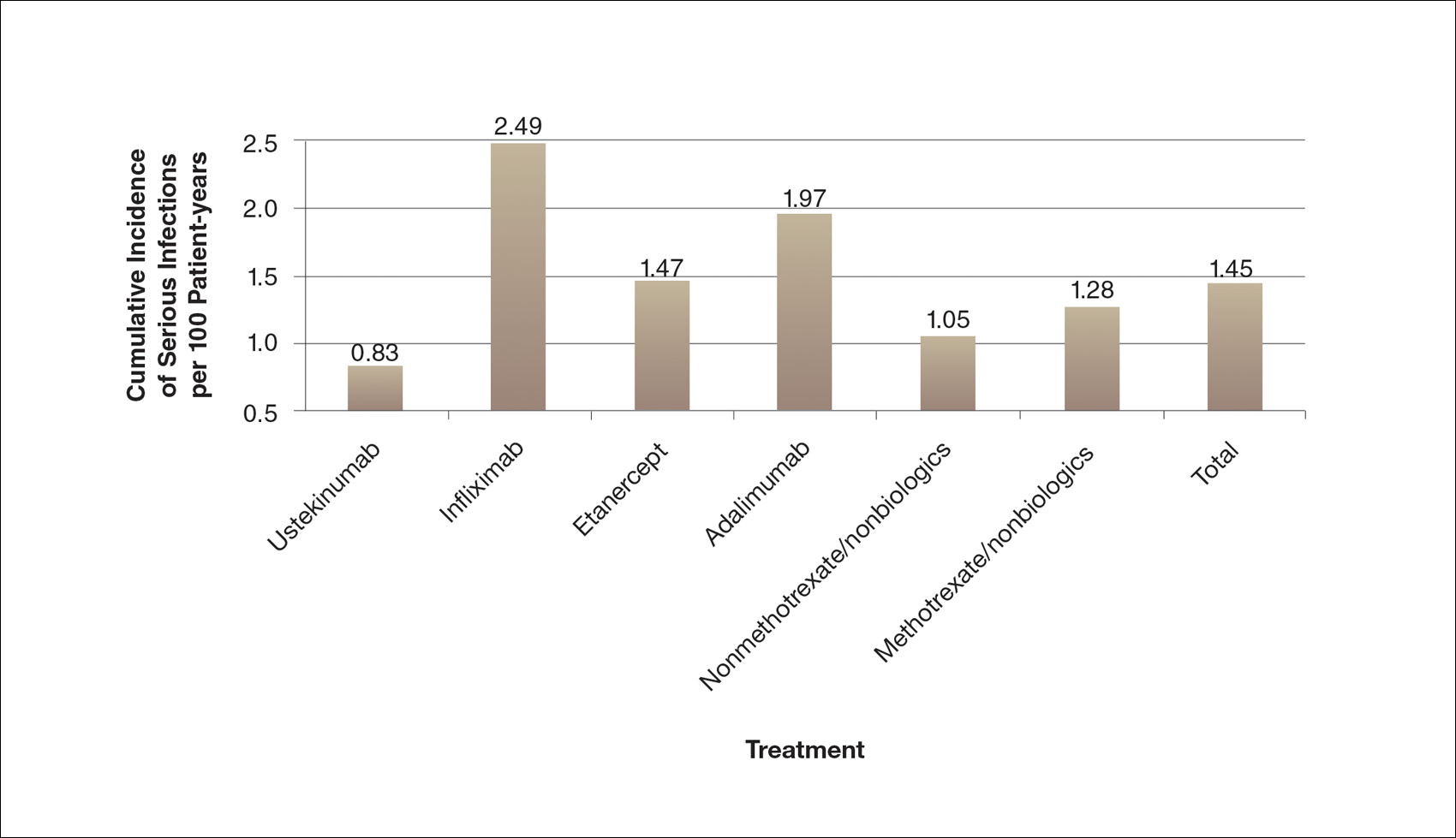

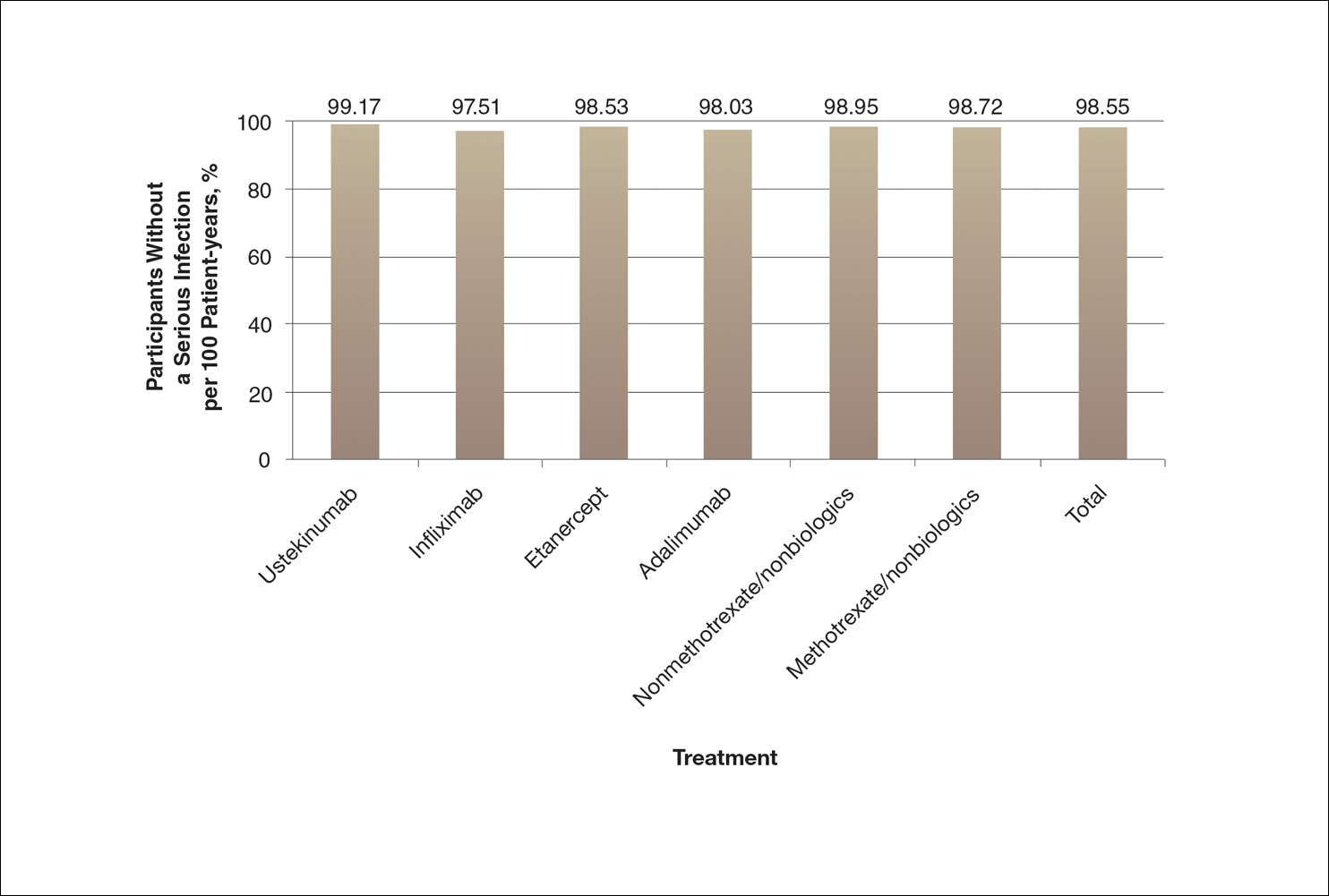

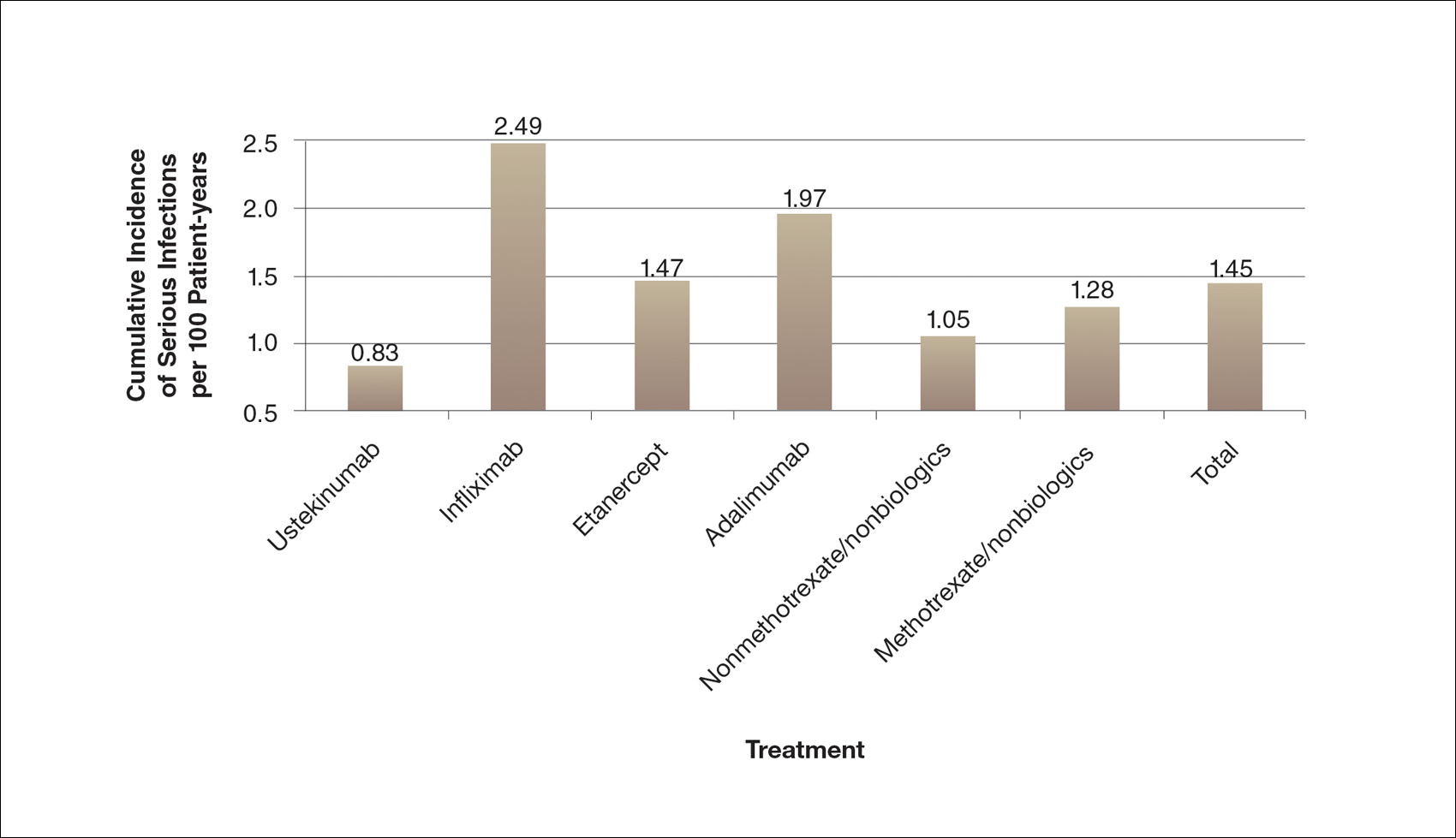

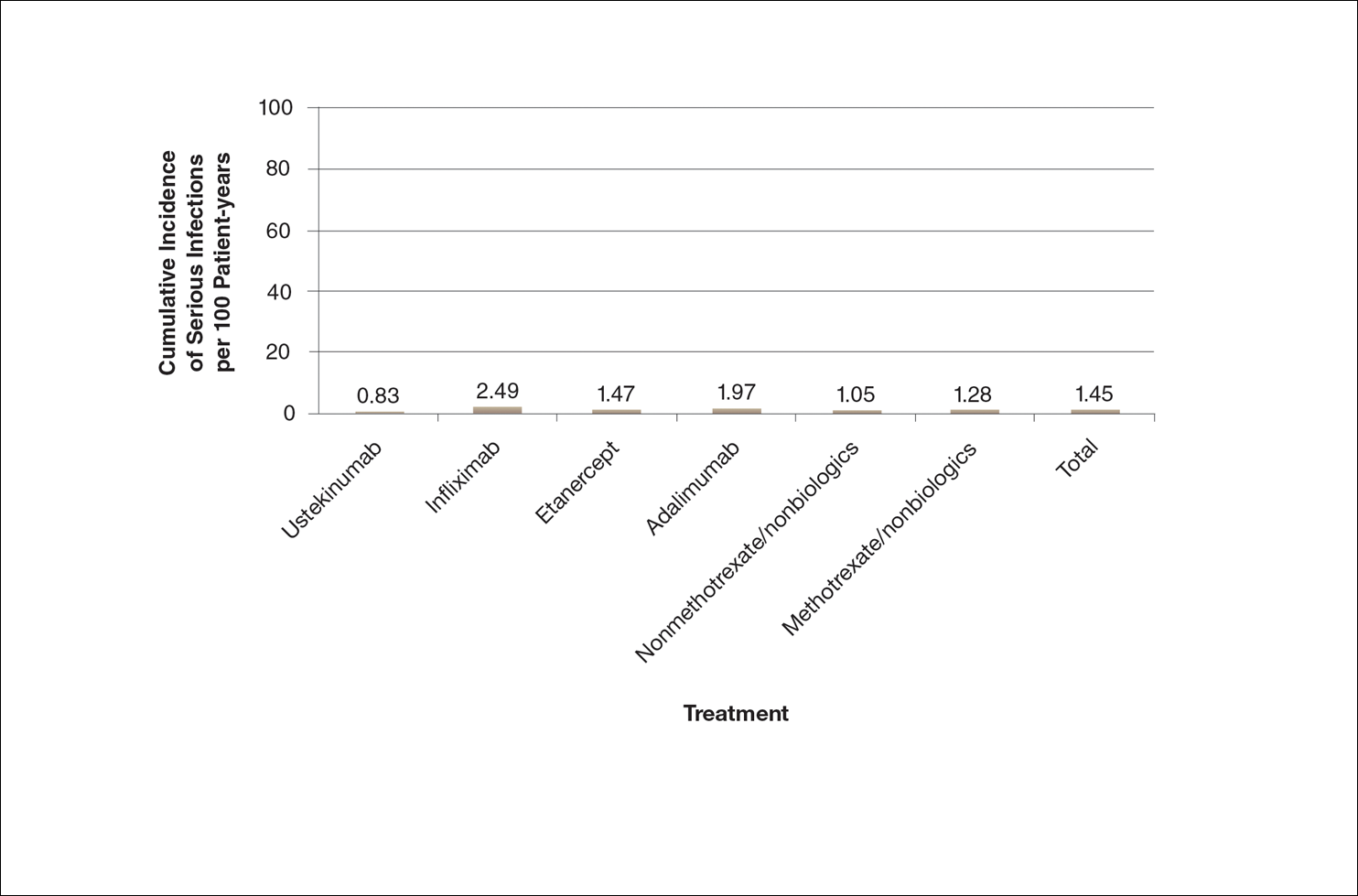

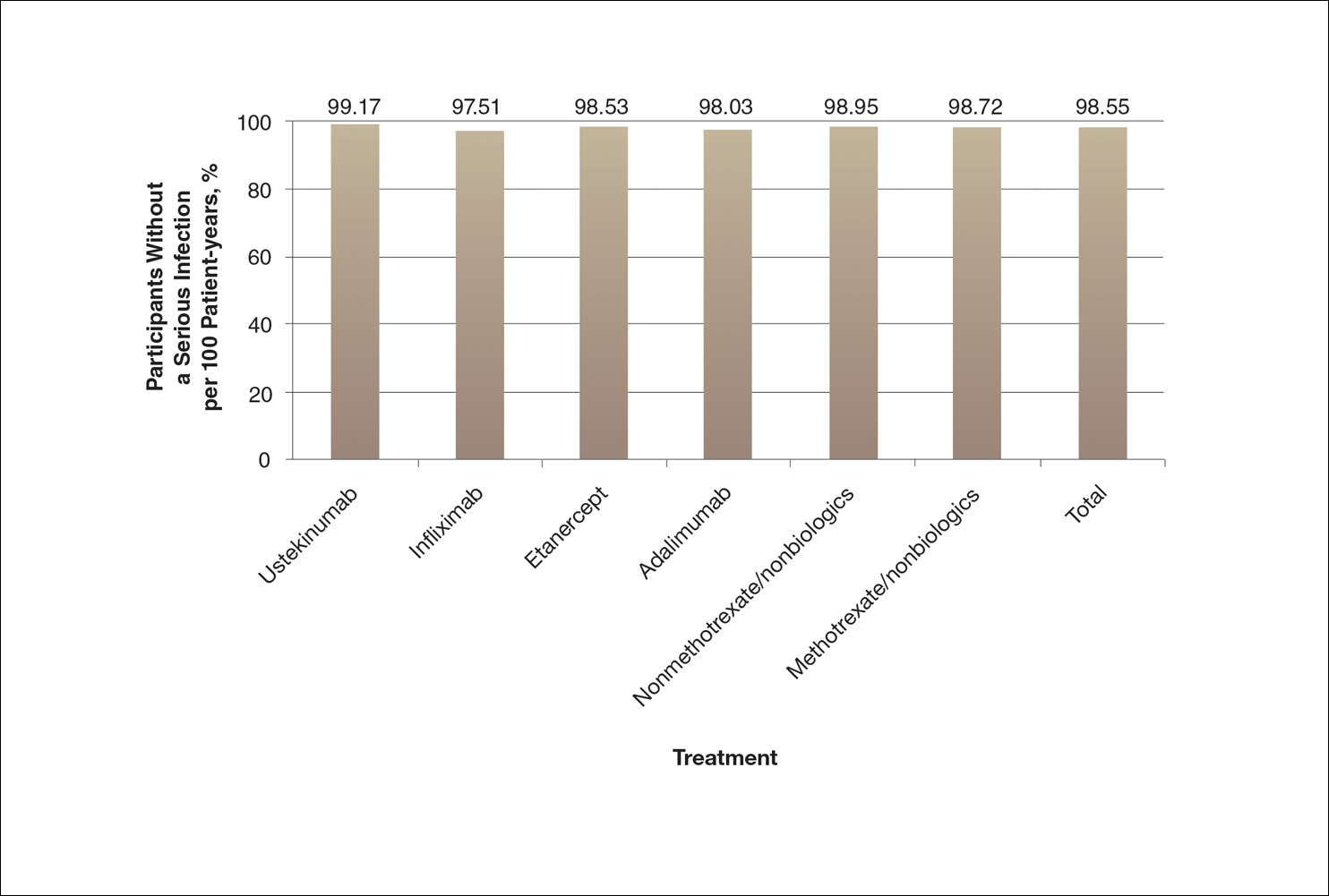

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

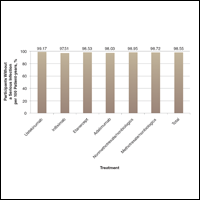

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

Practice Points

- Physicians can guide patients’ perceptions of drug safety by the way safety data are presented.

- For patients who are concerned about rare treatment risks, presenting data on the patients who have not experienced adverse effects can be reassuring.

Psoriasis not consistently linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes

Psoriasis was not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across nine studies in a systematic review of the literature, but four of the studies reported significant increases in at least one adverse outcome among women with psoriasis, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Many women with psoriasis develop the disorder during their reproductive years, and more than 100,000 births to such patients are estimated to occur in the United States each year. Other autoimmune diseases are known to adversely affect pregnancy outcomes, but the issue has not been well studied among women with psoriasis, said Robert Bobotsis, a medical student at Western University, London (Ont.), and his associates.

They performed a systematic review of the literature to examine a possible link, but were only able to find nine fair- or good-quality studies involving a total of 4,756 pregnancies from which to extract data concerning a possible association. This small sample size may have been underpowered to detect the uncommon adverse pregnancy outcomes being assessed. Moreover, the investigators were unable to conduct a meta-analysis pooling the data because the effect measures were inconsistent across the nine studies, Mr. Bobotsis and his associates noted.

The review included a retrospective case series, a retrospective case control study, three retrospective cohort studies, two prospective cohort studies, one cross-sectional study, and one study combining prospective and retrospective cohorts. It “did not demonstrate an increased risk of poor outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis” (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Jul 24;175:464-72).

However, four studies showed that compared with women who didn’t have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6. “Our results should be viewed as an opportunity to further research pregnancy outcomes in psoriasis,” the investigators said.

Psoriasis was not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across nine studies in a systematic review of the literature, but four of the studies reported significant increases in at least one adverse outcome among women with psoriasis, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Many women with psoriasis develop the disorder during their reproductive years, and more than 100,000 births to such patients are estimated to occur in the United States each year. Other autoimmune diseases are known to adversely affect pregnancy outcomes, but the issue has not been well studied among women with psoriasis, said Robert Bobotsis, a medical student at Western University, London (Ont.), and his associates.

They performed a systematic review of the literature to examine a possible link, but were only able to find nine fair- or good-quality studies involving a total of 4,756 pregnancies from which to extract data concerning a possible association. This small sample size may have been underpowered to detect the uncommon adverse pregnancy outcomes being assessed. Moreover, the investigators were unable to conduct a meta-analysis pooling the data because the effect measures were inconsistent across the nine studies, Mr. Bobotsis and his associates noted.

The review included a retrospective case series, a retrospective case control study, three retrospective cohort studies, two prospective cohort studies, one cross-sectional study, and one study combining prospective and retrospective cohorts. It “did not demonstrate an increased risk of poor outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis” (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Jul 24;175:464-72).

However, four studies showed that compared with women who didn’t have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6. “Our results should be viewed as an opportunity to further research pregnancy outcomes in psoriasis,” the investigators said.

Psoriasis was not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across nine studies in a systematic review of the literature, but four of the studies reported significant increases in at least one adverse outcome among women with psoriasis, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Many women with psoriasis develop the disorder during their reproductive years, and more than 100,000 births to such patients are estimated to occur in the United States each year. Other autoimmune diseases are known to adversely affect pregnancy outcomes, but the issue has not been well studied among women with psoriasis, said Robert Bobotsis, a medical student at Western University, London (Ont.), and his associates.

They performed a systematic review of the literature to examine a possible link, but were only able to find nine fair- or good-quality studies involving a total of 4,756 pregnancies from which to extract data concerning a possible association. This small sample size may have been underpowered to detect the uncommon adverse pregnancy outcomes being assessed. Moreover, the investigators were unable to conduct a meta-analysis pooling the data because the effect measures were inconsistent across the nine studies, Mr. Bobotsis and his associates noted.

The review included a retrospective case series, a retrospective case control study, three retrospective cohort studies, two prospective cohort studies, one cross-sectional study, and one study combining prospective and retrospective cohorts. It “did not demonstrate an increased risk of poor outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis” (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Jul 24;175:464-72).

However, four studies showed that compared with women who didn’t have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6. “Our results should be viewed as an opportunity to further research pregnancy outcomes in psoriasis,” the investigators said.

Key clinical point: Psoriasis is not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across studies, but individual studies reported such links.

Major finding: Four of nine studies showed that compared with women who did not have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6.

Data source: A systematic review of nine reports in the literature concerning adverse outcomes in 4,756 pregnancies among women with psoriasis.

Disclosures: The authors reported that this work had no funding sources. Mr. Bobotsis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bio-K, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Valeant.

Development of Bullous Pemphigoid in a Patient With Psoriasis and Metabolic Syndrome

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease.1 The majority of BP cases are idiopathic and occur in patients older than 60 years. The disease is characterized by the development of circulating IgG autoantibodies reacting with the BP180 antigen of the basement membrane zone.1 Psoriasis vulgaris (PV) is a common, chronic, immune-mediated disease affecting approximately 2% of the world’s population including children and adults.2 Both entities may coexist with internal disorders such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, and cerebrovascular accident. It has been postulated that BP more often coexists with neurological disorders, such as stroke and Parkinson disease,3 whereas PV usually is associated with cardiovascular disorders and diabetes mellitus.2 We report the case of a 35-year-old man with chronic PV and metabolic syndrome who developed BP that was successfully treated with methotrexate (MTX).

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a 15-year history of PV, class 3 obesity (body mass index, 69.2), and thrombosis of the left leg was referred to the dermatology department due to a sudden extensive erythematous and bullous eruption located on the trunk, arms, and legs with involvement of the oral mucosa that had started 4 weeks prior. The skin lesions were accompanied by severe pruritus. On admission to the hospital, the patient presented with stable psoriatic plaques located on the trunk, arms, and proximal part of the lower legs with a psoriasis area severity index score of 11.8 (Figure 1A). He also had disseminated tense blisters and erosions partially arranged in an annular pattern located on the border of the psoriatic plaques as well as on an erythematous base or within unaffected skin (Figure 1B). Additionally, a few small erosions were present on the oral mucosa.

The patient’s father had a history of PV, but there was no family history of obesity or autoimmune blistering disorders. On physical examination, central obesity was noted with a waist circumference of 180 cm and a body mass index of 69.2; his blood pressure was 220/150 mm Hg. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (20.06×109/L [reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L]) with neutrophilia (16.2×109/L [reference range, 1.6–7.6×109/L]; 80.9% [reference range, 40.0%–70.0%]), eosinophilia (1.01×109/L [reference range, 0–0.5×109/L]), elevated C-reactive protein levels (49.4 mg/L [reference range, 0.0–9.0 mg/L]), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (35 mm/h [reference range, 0–12 mm/h]), elevated γ-glutamyltransferase (66 U/L [reference range, 0–55 U/L]), decreased high-density lipoprotein levels (38 mg/dL [reference range, ≥40 mg/dL]), elevated fasting plasma glucose (116 mg/dL or 6.4 mmol/L [reference range, 70–99 mg/dL or 3.9–5.5 mmol/L]), elevated total IgE (1540 µg/L [reference range, 0–1000 µg/L]), elevated D-dimer (3.21 µg/mL [reference range, <0.5 µg/mL]), and low free triiodothyronine levels (130 pg/dL [reference range, 171–371 pg/dL]). The total protein level was 6.5 g/dL (reference range, 6.0–8.0 g/dL) and albumin level was 3.2 g/dL (reference range, 4.02–4.76 g/dL). A chest radiograph showed no abnormalities.

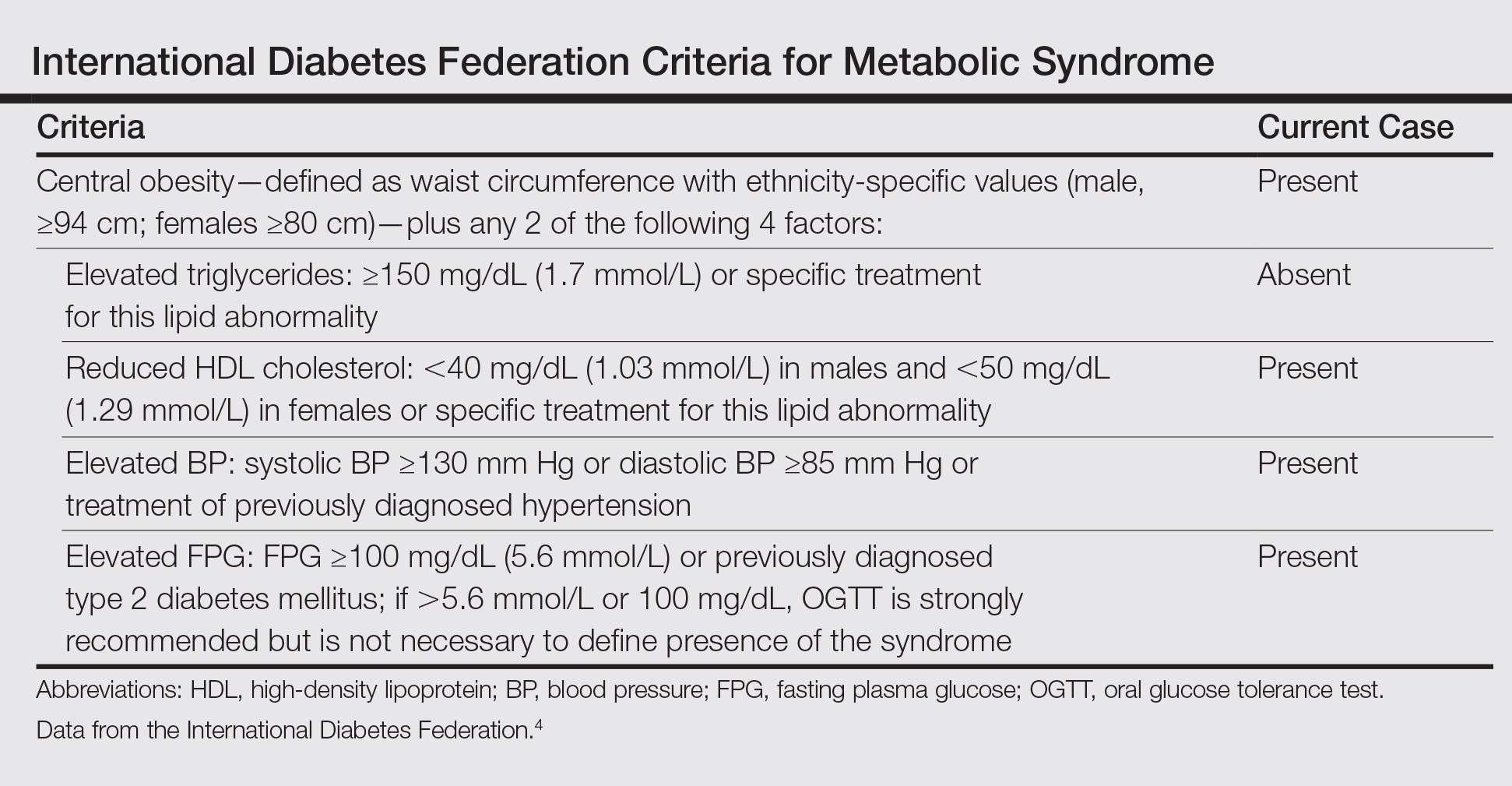

Based on the physical examination and laboratory testing, it was determined that the patient fulfilled 4 of 5 criteria for metabolic syndrome described by the International Diabetes Federation in 2006 (Table).4 Direct immunofluorescence performed on normal-appearing perilesional skin demonstrated linear IgG and C3 deposits along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence detected circulating IgG autoantibodies at a titer of 1:80. Serum studies using biochip mosaics5 revealed the reactivity of circulating IgG antibodies to the epidermal side of salt-split skin and with antigen dots of tetrameric BP180-NC16a, which prompted the diagnosis of BP (Figure 2).

Oral treatment with MTX 12.5 mg once weekly with clobetasol propionate cream applied to affected skin was initiated for 4 weeks. The PV resolved completely and blister formation stopped. A few weeks later BP reappeared, even though the patient was still taking MTX. The treatment failure may have been related to the patient’s class 3 obesity; therefore, the dose was increased to 20 mg once weekly for 8 weeks, which led to rapid healing of BP erosions. The patient was monitored for 2 months with no symptoms of recurrence.

Comment

Psoriasis Comorbidities

The correlation between PV and cardiovascular disorders such as myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, and pulmonary embolism has been well established and is widely accepted.2 It also has been documented that the risk for metabolic syndrome with components such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, lipid abnormalities, obesity, and arteriosclerosis is notably increased in PV patients.6 Moreover, associated internal disorders are responsible for a 3- to 4-year reduction in life expectancy in patients with moderate to severe PV.7

Correlation of PV and BP

Psoriasis also may coexist with autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, and blistering disorders.8 There are more than 60 known cases reporting PV in association with various types of subepidermal blistering diseases, including pemphigus vulgaris, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, anti-p200 pemphigoid, and BP.8,9 The pathogenetic relationship between BP and PV remains obscure. In most published cases, PV preceded BP by 5 to 30 years, possibly ascribable to patients being diagnosed with PV at a younger age.9 In general, patients with BP and PV are younger than patients with BP only, with a mean age of 62 years.9 Because our patient was in his mid-30s when he developed BP, in such cases physicians should take under consideration any triggering factors (eg, drugs). Physical examination and detailed laboratory findings allowed us to make the patient aware of the potential for development of metabolic syndrome. This condition in combination with PV could be a predisposing factor for BP development. According to more recent research, PV is considered a generalized inflammatory process rather than a disorder limited to the skin and joints.10 The chronic inflammatory process in psoriatic skin results in exposure of autoantigens, leading to an immune response and the production of BP antibodies. The neutrophil elastase enzyme present in psoriatic lesions also may take part in dermoepidermal junction degradation and blister formation of BP.11 According to other observations, some antipsoriatic therapies (eg, psoralen plus UVA, UVB, dithranol, coal tar) could be associated with development of BP.12 Moreover, it was shown that psoralen plus UVA therapy, which is widely used in PV treatment, alters the cytokine profile from helper T cells TH1 to TH2.12 TH2-dependent cytokines predominate the sera and erosions in BP patients and seem to be notably relevant to the pathophysiology of the disease.13 The history of our patient’s psoriatic treatment included only topical corticosteroids, keratolytic agents, and occasionally dithranol and coal tar; however, UV phototherapy or any other systemic therapies had never been utilized. Three previously reported cases of patients with PV and BP also revealed no history of UV phototherapy,8,9 which suggests that mechanisms responsible for coexistence of PV and BP are more complex. It has been proven that proinflammatory cytokines secreted by TH1 and TH17 cells, in particular tumor necrosis factor α, IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23, play an important role in the development of psoriatic lesions.10 On the other hand, these cytokines are known to contribute to vascular inflammation, leading to development of arteriosclerosis, as well as to regulate adipogenesis and obesity.14,15 Arakawa et al16 reported increased expression of IL-17 in lesional skin in BP. They concluded that IL-17 may contribute to the recruitment of eosinophils and neutrophils and tissue damage in BP. Therefore, it is highly likely that IL-17 might be a common factor underlying the coexistence of BP with PV and metabolic syndrome. More such reports are required for better understanding this association.

BP Treatment

Selecting a therapy for BP with coexistent PV is challenging, especially in patients with extreme obesity and metabolic syndrome. It is well established that obesity correlates with a higher incidence of PV and more severe disease. On the other hand, obesity also influences response to therapy. Systemic corticosteroids are contraindicated in psoriasis patients because of severe side effects, such as rebound phenomenon of psoriatic lesions and risk for development of generalized pustular PV. Although systemic corticosteroids are effective in BP, high-dose therapy may potentially be life-threatening, particularly in these obese patients with conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, among others,1 as was observed in our case. Taking into consideration the above mentioned conditions and our experience on such cases, the current patient had received MTX (12.5 mg once weekly) and clobetasol propionate cream, which led to the rapid healing of the psoriatic plaques, whereas BP was more resistant to this therapy. This response may be explained by our patient’s class 3 obesity (body mass index, 69.2). Therefore, the dose of MTX was increased to 20 mg once weekly and was successful. The decision to use MTX was supported by evidence that this medicine may reduce the risk for arteriosclerosis and cardiovascular disorders.17

There are some alternative therapeutic options for patients with coexisting BP and PV, such as cyclosporine,18 combination low-dose cyclosporine and low-dose systemic corticosteroids,19 dapsone,20 azathioprine,21 mycophenolate mofetil,22 and acitretin.23 It also has been shown that biologics (eg, ustekinumab) may be a successful solution in patients with PV and antilaminin-γ1 pemphigoid.24 However, these alternative therapeutic regimens could not be considered in our patient because of serious coexisting internal disorders.

Conclusion

We present a case of concomitant BP and PV in a patient with metabolic syndrome. Although the pathogenic role of this unique coexistence is not fully understood, MTX proved suitable and effective in this single case. Further studies should be performed to elucidate the pathogenic relationship and therapeutic solutions for cases with coexisting PV, BP, and metabolic syndrome.

- Rzany B, Partscht K, Jung M, et al. Risk factors for lethal outcome in patients with bullous pemphigoid: low serum albumin level, high dosage of gluco-corticosteroids, and old age. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:903-908.

- Pietrzak A, Bartosinska J, Chodorowska G, et al. Cardiovascular aspects of psoriasis vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:153-162.

- Stinco G, Codutti R, Scarbolo M, et al. A retrospective epidemiological study on the association of bullous pemphigoid and neurological diseases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:136-139.

- International Diabetes Federation. The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Foundation; 2006. http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/IDF_Meta_def_final.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- Van Beek N, Rentzsch K, Probst C, et al. Serological diagnosis of autoimmune bullous skin diseases: prospective comparison of the BIOCHIP mosaic-based indirect immunofluorescence technique with the conventional multi-step single test strategy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:49.

- Sommer DM, Jenisch S, Suchan M, et al. Increased prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;298:321-328.

- Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-1499.

- Lazarczyk M, Wozniak K, Ishii N, et al. Coexistence of psoriasis and pemphigoid—only a coincidence? Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:619-623.

- Yasuda H, Tomita Y, Shibaki A, et al. Two cases of subepidermal blistering disease with anti-p200 or 180-kD bullous pemphigoid antigen associated with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2004;209:149-155.

- Malakouti M, Brown GE, Wang E, et al. The role of IL-17 in psoriasis [published online February 20, 2014]. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:41-44.

- Glinski W, Jarzabek-Chorzelska M, Pierozynska-Dubowska M, et al. Basement membrane zone as a target for human neutrophil elastase in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 1990;282:506-511.

- Klosner G, Trautinger F, Knobler R, et al. Treatment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with 8-methoxypsoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation induces a shift in cytokine expression from a Th1 to a Th2 response. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:459-462.

- Gounni AS, Wellemans V, Agouli M, et al. Increased expression of Th2-associated chemokines in bullous pemphigoid disease. role of eosinophils in the production and release of these chemokines. Clin Immunol. 2006;120:220-231.

- Gao Q, Jiang Y, Ma T, et al. A critical function of Th17 proinflammatory cells in the development of atherosclerotic plaque in mice. J Immunol. 2010;185:5820-5827.

- Zúñiga LA, Shen WJ, Joyce-Shaikh B, et al. IL-17 regulates adipogenesis, glucose homeostasis, and obesity. J Immunol. 2010;185:6947-6959.

- Arakawa M, Dainichi T, Ishii N, et al. Lesional Th17 cells and regulatory T cells in bullous pemphigoid. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:1022-1024.

- Everett BM, Pradhan AD, Solomon DH, et al. Rationale and design of the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial: a test of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis. Am Heart J. 2013;166:199-207.

- Boixeda JP, Soria C, Medina S, et al. Bullous pemphigoid and psoriasis: treatment with cyclosporine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:152.

- Bianchi L, Gatti S, Nini G. Bullous pemphigoid and severe erythrodermic psoriasis: combined low-dose treatment with cyclosporine and systemic steroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(2, pt 1):278.

- Hisler BM, Blumenthal NC, Aronson PJ, et al. Bullous pemphigoid in psoriatic lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:683-684.

- Primka EJ III, Camisa C. Psoriasis and bullous pemphigoid treated with azathioprine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:121-123.

- Nousari HC, Sragovich A, Kimyai-Asadi A, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in autoimmune and inflammatory skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:265-268.

- Kobayashi TT, Elston DM, Libow LF, et al. A case of bullous pemphigoid limited to psoriatic plaques. Cutis. 2002;70:283-287.

- Maijima Y, Yagi H, Tateishi C, et al. A successful treatment with ustekinumab in case of antilaminin-γ1 pemphigoid associated with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1367-1369.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease.1 The majority of BP cases are idiopathic and occur in patients older than 60 years. The disease is characterized by the development of circulating IgG autoantibodies reacting with the BP180 antigen of the basement membrane zone.1 Psoriasis vulgaris (PV) is a common, chronic, immune-mediated disease affecting approximately 2% of the world’s population including children and adults.2 Both entities may coexist with internal disorders such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, and cerebrovascular accident. It has been postulated that BP more often coexists with neurological disorders, such as stroke and Parkinson disease,3 whereas PV usually is associated with cardiovascular disorders and diabetes mellitus.2 We report the case of a 35-year-old man with chronic PV and metabolic syndrome who developed BP that was successfully treated with methotrexate (MTX).

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a 15-year history of PV, class 3 obesity (body mass index, 69.2), and thrombosis of the left leg was referred to the dermatology department due to a sudden extensive erythematous and bullous eruption located on the trunk, arms, and legs with involvement of the oral mucosa that had started 4 weeks prior. The skin lesions were accompanied by severe pruritus. On admission to the hospital, the patient presented with stable psoriatic plaques located on the trunk, arms, and proximal part of the lower legs with a psoriasis area severity index score of 11.8 (Figure 1A). He also had disseminated tense blisters and erosions partially arranged in an annular pattern located on the border of the psoriatic plaques as well as on an erythematous base or within unaffected skin (Figure 1B). Additionally, a few small erosions were present on the oral mucosa.

The patient’s father had a history of PV, but there was no family history of obesity or autoimmune blistering disorders. On physical examination, central obesity was noted with a waist circumference of 180 cm and a body mass index of 69.2; his blood pressure was 220/150 mm Hg. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (20.06×109/L [reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L]) with neutrophilia (16.2×109/L [reference range, 1.6–7.6×109/L]; 80.9% [reference range, 40.0%–70.0%]), eosinophilia (1.01×109/L [reference range, 0–0.5×109/L]), elevated C-reactive protein levels (49.4 mg/L [reference range, 0.0–9.0 mg/L]), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (35 mm/h [reference range, 0–12 mm/h]), elevated γ-glutamyltransferase (66 U/L [reference range, 0–55 U/L]), decreased high-density lipoprotein levels (38 mg/dL [reference range, ≥40 mg/dL]), elevated fasting plasma glucose (116 mg/dL or 6.4 mmol/L [reference range, 70–99 mg/dL or 3.9–5.5 mmol/L]), elevated total IgE (1540 µg/L [reference range, 0–1000 µg/L]), elevated D-dimer (3.21 µg/mL [reference range, <0.5 µg/mL]), and low free triiodothyronine levels (130 pg/dL [reference range, 171–371 pg/dL]). The total protein level was 6.5 g/dL (reference range, 6.0–8.0 g/dL) and albumin level was 3.2 g/dL (reference range, 4.02–4.76 g/dL). A chest radiograph showed no abnormalities.

Based on the physical examination and laboratory testing, it was determined that the patient fulfilled 4 of 5 criteria for metabolic syndrome described by the International Diabetes Federation in 2006 (Table).4 Direct immunofluorescence performed on normal-appearing perilesional skin demonstrated linear IgG and C3 deposits along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence detected circulating IgG autoantibodies at a titer of 1:80. Serum studies using biochip mosaics5 revealed the reactivity of circulating IgG antibodies to the epidermal side of salt-split skin and with antigen dots of tetrameric BP180-NC16a, which prompted the diagnosis of BP (Figure 2).

Oral treatment with MTX 12.5 mg once weekly with clobetasol propionate cream applied to affected skin was initiated for 4 weeks. The PV resolved completely and blister formation stopped. A few weeks later BP reappeared, even though the patient was still taking MTX. The treatment failure may have been related to the patient’s class 3 obesity; therefore, the dose was increased to 20 mg once weekly for 8 weeks, which led to rapid healing of BP erosions. The patient was monitored for 2 months with no symptoms of recurrence.

Comment

Psoriasis Comorbidities

The correlation between PV and cardiovascular disorders such as myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, and pulmonary embolism has been well established and is widely accepted.2 It also has been documented that the risk for metabolic syndrome with components such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, lipid abnormalities, obesity, and arteriosclerosis is notably increased in PV patients.6 Moreover, associated internal disorders are responsible for a 3- to 4-year reduction in life expectancy in patients with moderate to severe PV.7

Correlation of PV and BP

Psoriasis also may coexist with autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, and blistering disorders.8 There are more than 60 known cases reporting PV in association with various types of subepidermal blistering diseases, including pemphigus vulgaris, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, anti-p200 pemphigoid, and BP.8,9 The pathogenetic relationship between BP and PV remains obscure. In most published cases, PV preceded BP by 5 to 30 years, possibly ascribable to patients being diagnosed with PV at a younger age.9 In general, patients with BP and PV are younger than patients with BP only, with a mean age of 62 years.9 Because our patient was in his mid-30s when he developed BP, in such cases physicians should take under consideration any triggering factors (eg, drugs). Physical examination and detailed laboratory findings allowed us to make the patient aware of the potential for development of metabolic syndrome. This condition in combination with PV could be a predisposing factor for BP development. According to more recent research, PV is considered a generalized inflammatory process rather than a disorder limited to the skin and joints.10 The chronic inflammatory process in psoriatic skin results in exposure of autoantigens, leading to an immune response and the production of BP antibodies. The neutrophil elastase enzyme present in psoriatic lesions also may take part in dermoepidermal junction degradation and blister formation of BP.11 According to other observations, some antipsoriatic therapies (eg, psoralen plus UVA, UVB, dithranol, coal tar) could be associated with development of BP.12 Moreover, it was shown that psoralen plus UVA therapy, which is widely used in PV treatment, alters the cytokine profile from helper T cells TH1 to TH2.12 TH2-dependent cytokines predominate the sera and erosions in BP patients and seem to be notably relevant to the pathophysiology of the disease.13 The history of our patient’s psoriatic treatment included only topical corticosteroids, keratolytic agents, and occasionally dithranol and coal tar; however, UV phototherapy or any other systemic therapies had never been utilized. Three previously reported cases of patients with PV and BP also revealed no history of UV phototherapy,8,9 which suggests that mechanisms responsible for coexistence of PV and BP are more complex. It has been proven that proinflammatory cytokines secreted by TH1 and TH17 cells, in particular tumor necrosis factor α, IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23, play an important role in the development of psoriatic lesions.10 On the other hand, these cytokines are known to contribute to vascular inflammation, leading to development of arteriosclerosis, as well as to regulate adipogenesis and obesity.14,15 Arakawa et al16 reported increased expression of IL-17 in lesional skin in BP. They concluded that IL-17 may contribute to the recruitment of eosinophils and neutrophils and tissue damage in BP. Therefore, it is highly likely that IL-17 might be a common factor underlying the coexistence of BP with PV and metabolic syndrome. More such reports are required for better understanding this association.

BP Treatment

Selecting a therapy for BP with coexistent PV is challenging, especially in patients with extreme obesity and metabolic syndrome. It is well established that obesity correlates with a higher incidence of PV and more severe disease. On the other hand, obesity also influences response to therapy. Systemic corticosteroids are contraindicated in psoriasis patients because of severe side effects, such as rebound phenomenon of psoriatic lesions and risk for development of generalized pustular PV. Although systemic corticosteroids are effective in BP, high-dose therapy may potentially be life-threatening, particularly in these obese patients with conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, among others,1 as was observed in our case. Taking into consideration the above mentioned conditions and our experience on such cases, the current patient had received MTX (12.5 mg once weekly) and clobetasol propionate cream, which led to the rapid healing of the psoriatic plaques, whereas BP was more resistant to this therapy. This response may be explained by our patient’s class 3 obesity (body mass index, 69.2). Therefore, the dose of MTX was increased to 20 mg once weekly and was successful. The decision to use MTX was supported by evidence that this medicine may reduce the risk for arteriosclerosis and cardiovascular disorders.17

There are some alternative therapeutic options for patients with coexisting BP and PV, such as cyclosporine,18 combination low-dose cyclosporine and low-dose systemic corticosteroids,19 dapsone,20 azathioprine,21 mycophenolate mofetil,22 and acitretin.23 It also has been shown that biologics (eg, ustekinumab) may be a successful solution in patients with PV and antilaminin-γ1 pemphigoid.24 However, these alternative therapeutic regimens could not be considered in our patient because of serious coexisting internal disorders.

Conclusion

We present a case of concomitant BP and PV in a patient with metabolic syndrome. Although the pathogenic role of this unique coexistence is not fully understood, MTX proved suitable and effective in this single case. Further studies should be performed to elucidate the pathogenic relationship and therapeutic solutions for cases with coexisting PV, BP, and metabolic syndrome.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease.1 The majority of BP cases are idiopathic and occur in patients older than 60 years. The disease is characterized by the development of circulating IgG autoantibodies reacting with the BP180 antigen of the basement membrane zone.1 Psoriasis vulgaris (PV) is a common, chronic, immune-mediated disease affecting approximately 2% of the world’s population including children and adults.2 Both entities may coexist with internal disorders such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, and cerebrovascular accident. It has been postulated that BP more often coexists with neurological disorders, such as stroke and Parkinson disease,3 whereas PV usually is associated with cardiovascular disorders and diabetes mellitus.2 We report the case of a 35-year-old man with chronic PV and metabolic syndrome who developed BP that was successfully treated with methotrexate (MTX).

Case Report

A 35-year-old man with a 15-year history of PV, class 3 obesity (body mass index, 69.2), and thrombosis of the left leg was referred to the dermatology department due to a sudden extensive erythematous and bullous eruption located on the trunk, arms, and legs with involvement of the oral mucosa that had started 4 weeks prior. The skin lesions were accompanied by severe pruritus. On admission to the hospital, the patient presented with stable psoriatic plaques located on the trunk, arms, and proximal part of the lower legs with a psoriasis area severity index score of 11.8 (Figure 1A). He also had disseminated tense blisters and erosions partially arranged in an annular pattern located on the border of the psoriatic plaques as well as on an erythematous base or within unaffected skin (Figure 1B). Additionally, a few small erosions were present on the oral mucosa.