User login

New data on worldwide mental health impact of COVID-19

A new survey that assessed the mental health impact of COVID-19 across the globe shows high rates of trauma and clinical mood disorders related to the pandemic.

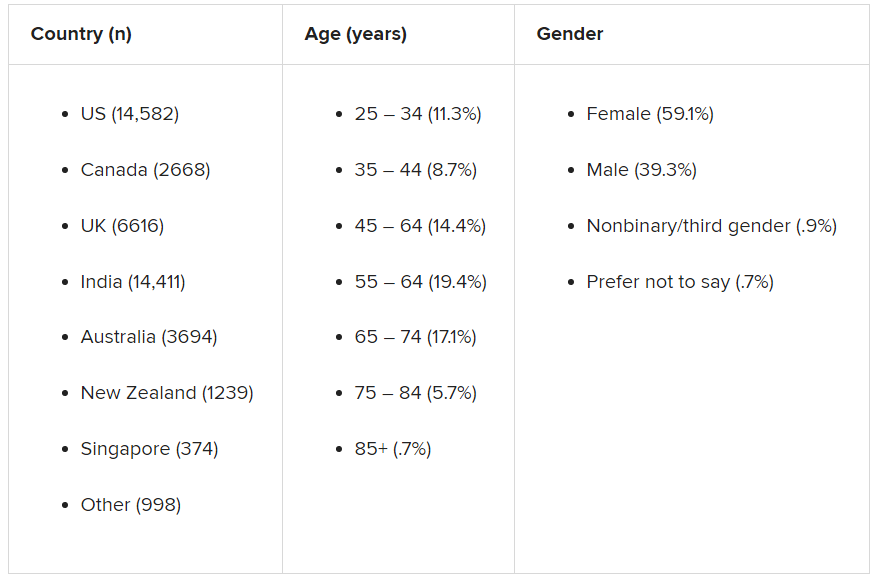

The survey, carried out by Sapien Labs, was conducted in eight English-speaking countries and included 49,000 adults. It showed that 57% of respondents experienced some COVID-19–related adversity or trauma.

Roughly one-quarter showed clinical signs of or were at risk for a mood disorder, and 40% described themselves as “succeeding or thriving.”

Those who reported the poorest mental health were young adults and individuals who experienced financial adversity or were unable to receive care for other medical conditions. Nonbinary gender and not getting enough sleep, exercise, or face-to-face socialization also increased the risk for poorer mental well-being.

“The data suggest that there will be long-term fallout from the pandemic on the mental health front,” Tara Thiagarajan, PhD, Sapien Labs founder and chief scientist, said in a press release.

Novel initiative

Dr. Thiagarajan said in an interview that she was running a company that provided microloans to 30,000 villages in India. The company included a research group the goal of which was to understand what predicts success in an individual and in a particular ecosystem, she said – “Why did some villages succeed and others didn’t?”

Dr. Thiagarajan and associates thought that “something big is happening in our life circumstances that causes changes in our brain and felt that we need to understand what they are and how they affect humanity. This was the impetus for founding Sapien Labs. “

The survey, which is part of the company’s Mental Health Million project, is an ongoing research initiative that makes data freely available to other researchers.

The investigators developed a “free and anonymous assessment tool,” the Mental Health Quotient (MHQ), which “encompasses a comprehensive view of our emotional, social, and cognitive function and capability,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

The MHQ consists of 47 “elements of mental well-being.” Respondents’ MHQ scores ranged from –100 to +200. Negative scores indicate poorer mental well-being. Respondents were categorized as clinical, at risk, enduring, managing, succeeding, and thriving.

MHQ scores were computed for six “broad dimensions” of mental health: Core cognition, complex cognition, mood and outlook, drive and motivation, social self, and mind-body connection.

Participants were recruited through advertising on Google and Facebook in eight English-speaking countries – Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and India. The researchers collected demographic information, including age, education, and gender.

First step

The assessment was completed by 48,808 respondents between April 8 and Dec. 31, 2020.

A smaller sample of 2,000 people from the same countries who were polled by the investigators in 2019 was used as a comparator.

Taken together, the overall mental well-being score for 2020 was 8% lower than the score obtained in 2019 from the same countries, and the percentage of respondents who fell into the “clinical” category increased from 14% in 2009 to 26% in 2020.

Residents of Singapore had the highest MHQ score, followed by residents of the United States. At the other extreme, respondents from the United Kingdom and South Africa had the poorest MHQ scores.

“It is important to keep in mind that the English-speaking, Internet-enabled populace is not necessarily representative of each country as a whole,” the authors noted.

Youth hardest hit

whose average MHQ score was 29% lower than those aged at least 65 years.

Worldwide, 70% of respondents aged at least 65 years fell into the categories of “succeeding” or “thriving,” compared with just 17% of those aged 18-24 years.

“We saw a massive trend of diminishing mental well-being in younger individuals, suggesting that some societal force is at play that we need to get to the bottom of,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

“Young people are still learning how to calibrate themselves in the world, and with age comes maturity, leading to a difference in emotional resilience,” she said.

Highest risk group

Mental well-being was poorest among nonbinary/third-gender respondents. Among those persons, more than 50% were classified as being at clinical risk, in comparison with males and females combined, and their MHQ scores were about 47 points lower.

Nonbinary individuals “are universally doing very poorly, relative to males or females,” said Dr. Thiagarajan. “This is a demographic at very high risk with a lot of suicidal thoughts.”

Respondents who had insufficient sleep, who lacked social interaction, and whose level of exercise was insufficient had lower MHQ scores of an “unexpected magnitude,” compared with their counterparts who had sufficient sleep, more social interaction, and more exercise (a discrepancy of 82, 66, and 46 points, respectively).

Only 3.9% of respondents reported having had COVID-19; 0.7% reported having had a severe case. Yet 57% of respondents reported that the pandemic had had negative consequences with regard to their health or their finances or social situation.

Those who were unable to get care for their other health conditions because of the pandemic (2% of all respondents) reported the worst mental well-being, followed by those who struggled for basic necessities (1.4%).

Reduced household income was associated with a 4% lower score but affected a higher percentage of people (17%). Social isolation was associated with a score of about 20 less. Higher rates of lifetime traumas and adversities were likewise associated with lower scores for mental well-being.

Creative, generous approach

Commenting on the survey results, Ken Duckworth, MD, clinical professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and chief medical officer of the National Alliance of Mental Illness, noted that the findings were similar to findings from studies in the United States, which showed disproportionately higher rates of mental health problems in younger individuals. Dr. Duckworth was not involved with the survey.

“The idea that this is an international phenomenon and the broad-stroke finding that younger people are suffering across nations is compelling and important for policymakers to look at,” he said.

Dr. Duckworth noted that although the findings are not “representative” of entire populations in a given country, the report is a “first step in a long journey.”

He described the report as “extremely brilliant, creative, and generous, allowing any academician to get access to the data.”

He saw it “less as a definitive report and more as a directionally informative survey that will yield great fruit over time.”

In a comment, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on the Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster, said: “One of the important things a document like this highlights is the importance of understanding more where risk [for mental health disorders] is concentrated and what things have occurred or might occur that can buffer against that risk or protect us from it. We see that each nation has similar but also different challenges.”

Dr. Thiagarajan is the founder and chief scientist of Sapien Labs. Her coauthors are employees of Sapien Labs. Dr. Duckworth and Dr. Morganstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey that assessed the mental health impact of COVID-19 across the globe shows high rates of trauma and clinical mood disorders related to the pandemic.

The survey, carried out by Sapien Labs, was conducted in eight English-speaking countries and included 49,000 adults. It showed that 57% of respondents experienced some COVID-19–related adversity or trauma.

Roughly one-quarter showed clinical signs of or were at risk for a mood disorder, and 40% described themselves as “succeeding or thriving.”

Those who reported the poorest mental health were young adults and individuals who experienced financial adversity or were unable to receive care for other medical conditions. Nonbinary gender and not getting enough sleep, exercise, or face-to-face socialization also increased the risk for poorer mental well-being.

“The data suggest that there will be long-term fallout from the pandemic on the mental health front,” Tara Thiagarajan, PhD, Sapien Labs founder and chief scientist, said in a press release.

Novel initiative

Dr. Thiagarajan said in an interview that she was running a company that provided microloans to 30,000 villages in India. The company included a research group the goal of which was to understand what predicts success in an individual and in a particular ecosystem, she said – “Why did some villages succeed and others didn’t?”

Dr. Thiagarajan and associates thought that “something big is happening in our life circumstances that causes changes in our brain and felt that we need to understand what they are and how they affect humanity. This was the impetus for founding Sapien Labs. “

The survey, which is part of the company’s Mental Health Million project, is an ongoing research initiative that makes data freely available to other researchers.

The investigators developed a “free and anonymous assessment tool,” the Mental Health Quotient (MHQ), which “encompasses a comprehensive view of our emotional, social, and cognitive function and capability,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

The MHQ consists of 47 “elements of mental well-being.” Respondents’ MHQ scores ranged from –100 to +200. Negative scores indicate poorer mental well-being. Respondents were categorized as clinical, at risk, enduring, managing, succeeding, and thriving.

MHQ scores were computed for six “broad dimensions” of mental health: Core cognition, complex cognition, mood and outlook, drive and motivation, social self, and mind-body connection.

Participants were recruited through advertising on Google and Facebook in eight English-speaking countries – Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and India. The researchers collected demographic information, including age, education, and gender.

First step

The assessment was completed by 48,808 respondents between April 8 and Dec. 31, 2020.

A smaller sample of 2,000 people from the same countries who were polled by the investigators in 2019 was used as a comparator.

Taken together, the overall mental well-being score for 2020 was 8% lower than the score obtained in 2019 from the same countries, and the percentage of respondents who fell into the “clinical” category increased from 14% in 2009 to 26% in 2020.

Residents of Singapore had the highest MHQ score, followed by residents of the United States. At the other extreme, respondents from the United Kingdom and South Africa had the poorest MHQ scores.

“It is important to keep in mind that the English-speaking, Internet-enabled populace is not necessarily representative of each country as a whole,” the authors noted.

Youth hardest hit

whose average MHQ score was 29% lower than those aged at least 65 years.

Worldwide, 70% of respondents aged at least 65 years fell into the categories of “succeeding” or “thriving,” compared with just 17% of those aged 18-24 years.

“We saw a massive trend of diminishing mental well-being in younger individuals, suggesting that some societal force is at play that we need to get to the bottom of,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

“Young people are still learning how to calibrate themselves in the world, and with age comes maturity, leading to a difference in emotional resilience,” she said.

Highest risk group

Mental well-being was poorest among nonbinary/third-gender respondents. Among those persons, more than 50% were classified as being at clinical risk, in comparison with males and females combined, and their MHQ scores were about 47 points lower.

Nonbinary individuals “are universally doing very poorly, relative to males or females,” said Dr. Thiagarajan. “This is a demographic at very high risk with a lot of suicidal thoughts.”

Respondents who had insufficient sleep, who lacked social interaction, and whose level of exercise was insufficient had lower MHQ scores of an “unexpected magnitude,” compared with their counterparts who had sufficient sleep, more social interaction, and more exercise (a discrepancy of 82, 66, and 46 points, respectively).

Only 3.9% of respondents reported having had COVID-19; 0.7% reported having had a severe case. Yet 57% of respondents reported that the pandemic had had negative consequences with regard to their health or their finances or social situation.

Those who were unable to get care for their other health conditions because of the pandemic (2% of all respondents) reported the worst mental well-being, followed by those who struggled for basic necessities (1.4%).

Reduced household income was associated with a 4% lower score but affected a higher percentage of people (17%). Social isolation was associated with a score of about 20 less. Higher rates of lifetime traumas and adversities were likewise associated with lower scores for mental well-being.

Creative, generous approach

Commenting on the survey results, Ken Duckworth, MD, clinical professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and chief medical officer of the National Alliance of Mental Illness, noted that the findings were similar to findings from studies in the United States, which showed disproportionately higher rates of mental health problems in younger individuals. Dr. Duckworth was not involved with the survey.

“The idea that this is an international phenomenon and the broad-stroke finding that younger people are suffering across nations is compelling and important for policymakers to look at,” he said.

Dr. Duckworth noted that although the findings are not “representative” of entire populations in a given country, the report is a “first step in a long journey.”

He described the report as “extremely brilliant, creative, and generous, allowing any academician to get access to the data.”

He saw it “less as a definitive report and more as a directionally informative survey that will yield great fruit over time.”

In a comment, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on the Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster, said: “One of the important things a document like this highlights is the importance of understanding more where risk [for mental health disorders] is concentrated and what things have occurred or might occur that can buffer against that risk or protect us from it. We see that each nation has similar but also different challenges.”

Dr. Thiagarajan is the founder and chief scientist of Sapien Labs. Her coauthors are employees of Sapien Labs. Dr. Duckworth and Dr. Morganstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey that assessed the mental health impact of COVID-19 across the globe shows high rates of trauma and clinical mood disorders related to the pandemic.

The survey, carried out by Sapien Labs, was conducted in eight English-speaking countries and included 49,000 adults. It showed that 57% of respondents experienced some COVID-19–related adversity or trauma.

Roughly one-quarter showed clinical signs of or were at risk for a mood disorder, and 40% described themselves as “succeeding or thriving.”

Those who reported the poorest mental health were young adults and individuals who experienced financial adversity or were unable to receive care for other medical conditions. Nonbinary gender and not getting enough sleep, exercise, or face-to-face socialization also increased the risk for poorer mental well-being.

“The data suggest that there will be long-term fallout from the pandemic on the mental health front,” Tara Thiagarajan, PhD, Sapien Labs founder and chief scientist, said in a press release.

Novel initiative

Dr. Thiagarajan said in an interview that she was running a company that provided microloans to 30,000 villages in India. The company included a research group the goal of which was to understand what predicts success in an individual and in a particular ecosystem, she said – “Why did some villages succeed and others didn’t?”

Dr. Thiagarajan and associates thought that “something big is happening in our life circumstances that causes changes in our brain and felt that we need to understand what they are and how they affect humanity. This was the impetus for founding Sapien Labs. “

The survey, which is part of the company’s Mental Health Million project, is an ongoing research initiative that makes data freely available to other researchers.

The investigators developed a “free and anonymous assessment tool,” the Mental Health Quotient (MHQ), which “encompasses a comprehensive view of our emotional, social, and cognitive function and capability,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

The MHQ consists of 47 “elements of mental well-being.” Respondents’ MHQ scores ranged from –100 to +200. Negative scores indicate poorer mental well-being. Respondents were categorized as clinical, at risk, enduring, managing, succeeding, and thriving.

MHQ scores were computed for six “broad dimensions” of mental health: Core cognition, complex cognition, mood and outlook, drive and motivation, social self, and mind-body connection.

Participants were recruited through advertising on Google and Facebook in eight English-speaking countries – Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and India. The researchers collected demographic information, including age, education, and gender.

First step

The assessment was completed by 48,808 respondents between April 8 and Dec. 31, 2020.

A smaller sample of 2,000 people from the same countries who were polled by the investigators in 2019 was used as a comparator.

Taken together, the overall mental well-being score for 2020 was 8% lower than the score obtained in 2019 from the same countries, and the percentage of respondents who fell into the “clinical” category increased from 14% in 2009 to 26% in 2020.

Residents of Singapore had the highest MHQ score, followed by residents of the United States. At the other extreme, respondents from the United Kingdom and South Africa had the poorest MHQ scores.

“It is important to keep in mind that the English-speaking, Internet-enabled populace is not necessarily representative of each country as a whole,” the authors noted.

Youth hardest hit

whose average MHQ score was 29% lower than those aged at least 65 years.

Worldwide, 70% of respondents aged at least 65 years fell into the categories of “succeeding” or “thriving,” compared with just 17% of those aged 18-24 years.

“We saw a massive trend of diminishing mental well-being in younger individuals, suggesting that some societal force is at play that we need to get to the bottom of,” said Dr. Thiagarajan.

“Young people are still learning how to calibrate themselves in the world, and with age comes maturity, leading to a difference in emotional resilience,” she said.

Highest risk group

Mental well-being was poorest among nonbinary/third-gender respondents. Among those persons, more than 50% were classified as being at clinical risk, in comparison with males and females combined, and their MHQ scores were about 47 points lower.

Nonbinary individuals “are universally doing very poorly, relative to males or females,” said Dr. Thiagarajan. “This is a demographic at very high risk with a lot of suicidal thoughts.”

Respondents who had insufficient sleep, who lacked social interaction, and whose level of exercise was insufficient had lower MHQ scores of an “unexpected magnitude,” compared with their counterparts who had sufficient sleep, more social interaction, and more exercise (a discrepancy of 82, 66, and 46 points, respectively).

Only 3.9% of respondents reported having had COVID-19; 0.7% reported having had a severe case. Yet 57% of respondents reported that the pandemic had had negative consequences with regard to their health or their finances or social situation.

Those who were unable to get care for their other health conditions because of the pandemic (2% of all respondents) reported the worst mental well-being, followed by those who struggled for basic necessities (1.4%).

Reduced household income was associated with a 4% lower score but affected a higher percentage of people (17%). Social isolation was associated with a score of about 20 less. Higher rates of lifetime traumas and adversities were likewise associated with lower scores for mental well-being.

Creative, generous approach

Commenting on the survey results, Ken Duckworth, MD, clinical professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and chief medical officer of the National Alliance of Mental Illness, noted that the findings were similar to findings from studies in the United States, which showed disproportionately higher rates of mental health problems in younger individuals. Dr. Duckworth was not involved with the survey.

“The idea that this is an international phenomenon and the broad-stroke finding that younger people are suffering across nations is compelling and important for policymakers to look at,” he said.

Dr. Duckworth noted that although the findings are not “representative” of entire populations in a given country, the report is a “first step in a long journey.”

He described the report as “extremely brilliant, creative, and generous, allowing any academician to get access to the data.”

He saw it “less as a definitive report and more as a directionally informative survey that will yield great fruit over time.”

In a comment, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on the Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster, said: “One of the important things a document like this highlights is the importance of understanding more where risk [for mental health disorders] is concentrated and what things have occurred or might occur that can buffer against that risk or protect us from it. We see that each nation has similar but also different challenges.”

Dr. Thiagarajan is the founder and chief scientist of Sapien Labs. Her coauthors are employees of Sapien Labs. Dr. Duckworth and Dr. Morganstein disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The lasting effects of childhood trauma

Childhood trauma, which is also called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), can have lasting detrimental effects on individuals as they grow and mature into adulthood. ACEs may occur in children age ≤18 years if they experience abuse or neglect, violence, or other traumatic losses. More than 60% of people experience at least 1 ACE, and 1 in 6 individuals reported that they had experienced ≥4 ACEs.1 Subsequent additional ACEs have a cumulative deteriorating impact on the brain. This predisposes individuals to mental health disorders, substance use disorders, and other psychosocial problems. The efficacy of current therapeutic approaches provides only partial symptom resolution. For such individuals, the illness load and health care costs typically remain high across the lifespan.1,2

In this article, we discuss types of ACEs, protective factors and risk factors that influence the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in individuals who experience ACEs, how ACEs can negatively impact mental health in adulthood, and approaches to prevent or treat PTSD and other symptoms.

Types of trauma and correlation with PTSD

ACEs can be indexed as neglect or emotional, physical, or sexual abuse. Physical and sexual abuse strongly correlate with an increased risk of PTSD.3 Although neglect and emotional abuse do not directly predict the development of PTSD, these experiences foretell high rates of lifelong trauma exposure and are indirectly related to late PTSD symptoms.4,5 ACEs can impede an individual’s cognitive, social, and emotional development, diminish quality of life, and lead to an early death.6 The lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 6.1% to 9.2%.7 Compared with men, women are 4 times more likely to develop PTSD following a traumatic event.7

The development of PTSD is influenced by the nature, duration, and degree of trauma, and age at the time of exposure to trauma. Children who survive complex trauma (≥2 types of trauma) have a higher likelihood of developing PTSD.8 Prolonged trauma exposure has a more substantial negative impact than a one-time occurrence. However, it is an erroneous oversimplification to assume that each type of ACE has an equally traumatic effect.6

Factors that protect against PTSD

Factors that can protect against developing PTSD are listed in Table 1.7 Two of these are resilience and hope.

Resilience is defined as an individual’s strength to cope with difficulties in life.9 Resilience has internal psychological characteristics and external factors that aid in protecting against childhood adversities.10,11 The Brief Resilience Scale is a self-assessment that measures innate abilities to cope, including optimism, self-efficacy, patience, faith, and humor.12,13 External factors associated with resilience are family, friends, and community support.11,13

Hope can help in surmounting ACEs. The Adult Hope Scale has been used in many studies to assess this construct in individuals who have survived trauma.13 Some studies have found decreased hope in individuals who sustained early trauma and were diagnosed with PTSD in adulthood.14 A study examining children exposed to domestic violence found that children who showed high hope, endurance, and curiosity were better able to cope with adversities.15

Continue to: PTSD risk factors

PTSD risk factors

Many individual and societal risk factors can influence the likelihood of developing PTSD. Some of these factors are outlined in Table 1.7

Pathophysiology of PTSD

Multiple brain regions, pathways, and neurotransmitters are involved in the development of PTSD. Neuroimaging has identified volume and activity changes of the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala in patients with early trauma and PTSD. Some researchers have suggested a gross reduction in locus coeruleus neuronal volume in war veterans with a likely diagnosis of PTSD compared with controls.16,17 In other studies, chronic stress exposure has been found to cause neuronal cell death and affect neuronal plasticity in the limbic area of the brain.18

Diagnosing PTSD

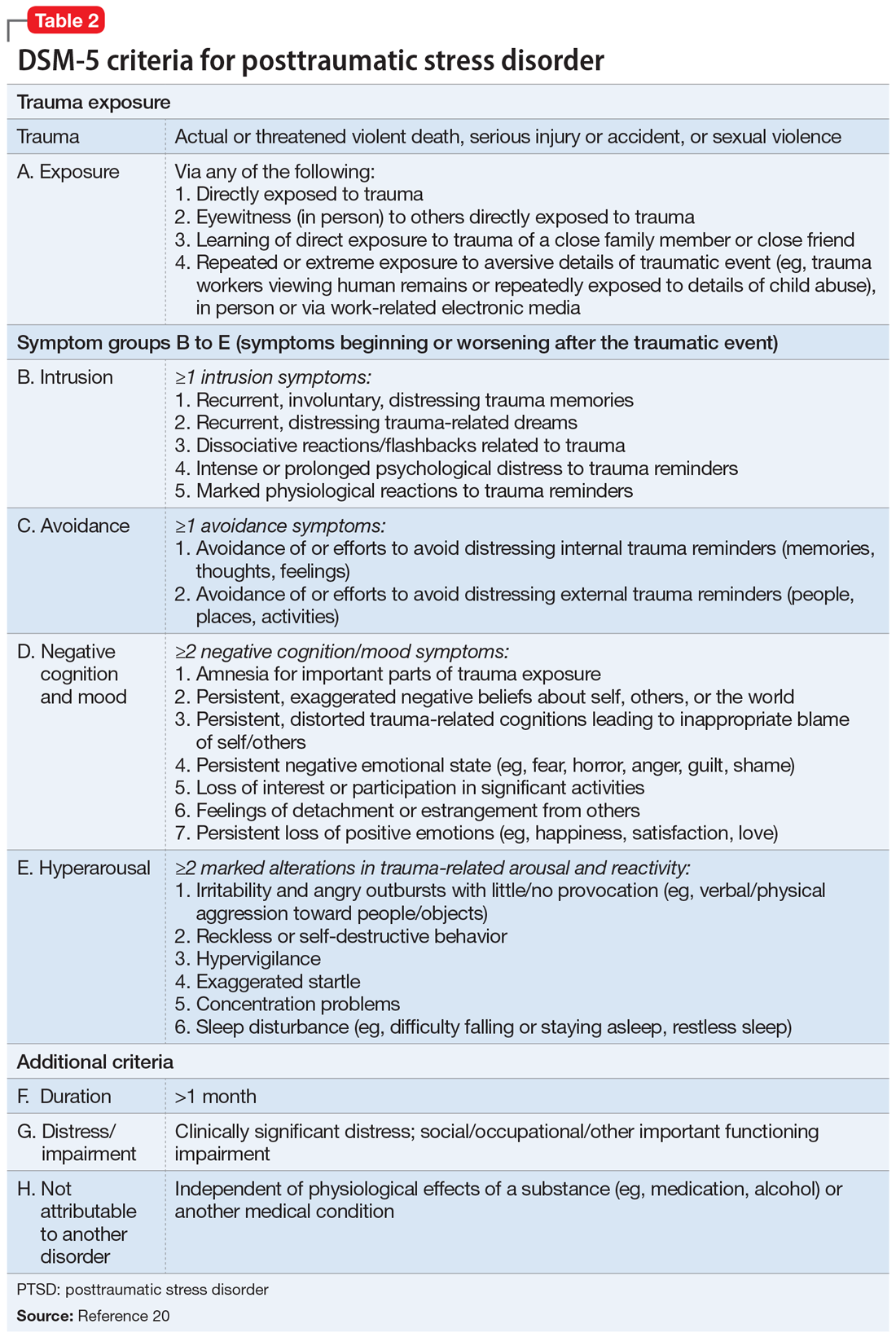

More than 30% of individuals who experience ACEs develop PTSD.19 The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD are outlined in Table 2.20 Several instruments are used to determine the diagnosis and assess the severity of PTSD. These include the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5,21 which is a 30-item structured interview that can be administered in 45 to 60 minutes; the PTSD Symptom Scale Self-Report Version, which is a 17-item, Likert scale, self-report questionnaire; and the Structured Clinical Interview: PTSD Module, which is a semi-structured interview that can take up to several hours to administer.21

Other disorders. In addition to PTSD, individuals with ACEs are at high risk for other mental health issues throughout their lifetime. Individuals with ACE often experience depressive symptoms (approximately 40%); anxiety (approximately 30%); anger; guilt or shame; negative self-cognition; interpersonal difficulties; rumination; and thoughts of self-harm and suicide.22 Epidemiological studies suggest that patients who experience childhood sexual abuse are more likely to develop mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in adulthood.23,24

Psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses the relationship between an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. CBT can be used to treat adults and children with PTSD. Before starting CBT, assess the patient’s current safety to ensure that they have the coping skills to manage distress related to their ACEs, and address any coexisting substance use.25

Continue to: According to the American Psychological Association...

According to the American Psychological Association, several CBT-based psychotherapies are recommended for treating PTSD26:

Trauma-focused–CBT includes psychoeducation, trauma narrative, processing, exposure, and relaxation skills training. It consists of approximately 12 to 16 sessions and incorporates elements of family therapy.

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) focuses on helping patients develop adaptive cognitive domains about the self, the people around them, and the world. CPT therapists assist in information processing by accessing the traumatic memory and trying to eliminate emotions tied to it.25,27 CPT consists of 12 to 16 structured individual, group, or combined sessions.

Prolonged exposure (PE) targets fear-related emotions and works on the principles of habituation to extinguish trauma and fear response to the trigger. This increases self-reliance and competence and decreases the generalization of anxiety to innocuous triggers. PE typically consists of 9 to 12 sessions. PE alone or in combination with cognitive restructuring is successful in treating patients with PTSD, but cognitive restructuring has limited utility in young children.25,27

Cognitive exposure can be individual or group therapy delivered over 3 months, where negative self-evaluation and traumatic memories are challenged with the goal of interrupting maladaptive behaviors and thoughts.27

Continue to: Stress inoculation training

Stress inoculation training (SIT) provides psychoeducation, skills training, role-playing, deep muscle relaxation, paced breathing, and thought stopping. Emphasis is on coaching skills to alleviate anxiety, fear, and symptoms of depression associated with trauma. In SIT, exposures to traumatic memories are indirect (eg, role play), compared with PE, where the exposures are direct.25

The American Psychological Association conditionally recommended several other forms for psychotherapy for treating patients with PTSD26:

Brief eclectic psychotherapy uses CBT and psychodynamic approaches to target feelings of guilt and shame in 16 sessions.27

Narrative exposure therapy consists of 4 to 10 group sessions in which individuals provide detailed narration of the events; the focus is on self-respect and personal rights.27

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a 6- to 12-session, 8-phase treatment that uses principles of accelerated information processing to target nonverbal expression of trauma and dissociative experiences. Patients with PTSD are suggested to have disrupted rapid eye movements. In EMDR, patients follow rhythmic movements of the therapist’s hands or flashed light. This is designed to decrease stress associated with accessing trauma memories, the emotional/physiologic response from the memories, and negative cognitive distortions about self, and to replace negative cognition distortions with positive thoughts about self.25,27

Continue to: Accelerated resolution therapy

Accelerated resolution therapy is a derivative of EMDR. It helps to reconsolidate the emotional and physical experiences associated with distressing memories by replacing them with positive ones or decreasing physiological arousal and anxiety related to the recall of traumatic memories.28

Pharmacologic treatments

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Multiple studies using different scales have found that paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine can decrease PTSD symptoms. Approximately 60% of patients treated with SSRIs experience partial remission of symptoms, and 20% to 30% experience complete symptom resolution.29 Davidson et al30 found that 22% of patients with PTSD who received fluoxetine had a relapse of symptoms, compared with 50% of patients who received placebo.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other antidepressants. The SNRIs venlafaxine and duloxetine can help reduce hyperarousal symptoms and improve mood, anxiety, and sleep.26 Mirtazapine, an alpha 2A/2C adrenoceptor antagonist/5-HT 2A/2C/3 antagonist, can address PTSD symptoms from both serotonergic pathways and increase norepinephrine release by blocking autoreceptors and enhancing alpha-1 receptor activity. This alleviates hyperarousal symptoms and promotes sleep.29 In addition to having monoaminergic effects, antidepressant medications also regulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis response to stress and promote neurogenesis in the hippocampal region.29

Adrenergic agents

Adrenergic receptor antagonists. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist, decreases hyperarousal symptoms, improves sleep, and decreases nightmares related to PTSD by decreasing noradrenergic hyperactivity.29

Beta-blockers such as propranolol can decrease physiological response to trauma but have mixed results in the prevention or improvement of PTSD symptoms.29,31

Continue to: Glucocorticoid receptor agonists

Glucocorticoid receptor agonists. In a very small study, low-dose cortisol decreased the severity of traumatic memory (consolidation phase).32 Glucocorticoid receptor agonists can also diminish memory retrieval (reconsolidation phase) through intrusive thoughts and flashbacks.29

Anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics

These medications have had a limited role in the treatment of PTSD.26,29

Future directions: Preventive treatments

Because PTSD has a profound impact on an individual’s quality of life and the development of other illnesses, there is strong interest in finding treatments that can prevent PTSD. Based on limited evidence primarily from animal studies, some researchers have suggested that certain agents may someday be helpful for PTSD prevention29:

Glucocorticoid antagonists such as corticotropin-releasing factor 1 (CRF1) antagonists or cholecystokinin 2 (CCK2) receptor antagonists might promote resilience to stress by inhibiting the HPA axis and influencing the amygdala by decreasing fear conditioning, as observed in animal models. Similarly, in animal models, CRF1 and CCK2 are predicted to decrease memory consolidation in response to exposure to stress.

Adrenoceptor antagonists and agonists also might have a role in preventive treatment, but the evidence is scarce. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist, was ineffective in animal models.29,31 Propranolol, a beta-adrenoceptor blocker, has had mixed results but can decrease trauma-induced physiological arousal when administered soon after exposure.29

Continue to: N-methyl-

N-methyl-

Bottom Line

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are strong predictors for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health or medical issues in late adolescence and adulthood. Experiencing a higher number of ACEs increases the risk of developing PTSD as an adult. Timely psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic interventions can help limit symptoms and reduce the severity of PTSD.

Related Resources

- Smith P, Dalglesih T, Meiser-Stedman R. Practitioner review: posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(5):500-515.

- North CS, Hong BA, Downs DL. PTSD: a systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment. Current Psychiatry 2018;17(4):35-43.

Drug Brand Names

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal, Pronol

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing adverse childhood experiences. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/aces/fastfact.html

2. Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:378-385.

3. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, et al. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

4. Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, et al. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(11):1247-1258.

5. Glück TM, Knefel M, Lueger-Schuster B. A network analysis of anger, shame, proposed ICD-11 post-traumatic stress disorder, and different types of childhood trauma in foster care settings in a sample of adult survivors. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(suppl 3):1372543. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1372543

6. Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, et al. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1453-1460.

7. Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated December 3, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-in-adults-epidemiology-pathophysiology-clinical-manifestations-course-assessment-and-diagnosis

8. Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999:156;1223-1229.

9. Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(3):316-331.

10. Ahern NR, Kiehl EM, Sole ML, et al. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2006;29(2):103-125.

11. Zimmerman MA. Resiliency theory: a strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):381-383.

12. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82.

13. Munoz RT, Hanks H, Hellman CM. Hope and resilience as distinct contributors to psychological flourishing among childhood trauma survivors. Traumatology. 2020;26(2):177-184.

14. Baxter MA, Hemming EJ, McIntosh HC, et al. Exploring the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and hope. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(8):948-956.

15. Hellman CM, Gwinn C. Camp HOPE as an intervention for children exposed to domestic violence: a program evaluation of hope, and strength of character. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2017;34:269-276.

16. Bracha HS, Garcia-Rill E, Mrak RE, et al. Postmortem locus coeruleus neuron count in three American veterans with probable or possible war-related PTSD. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(4):503-9.

17. de Lange GM. Understanding the cellular and molecular alterations in PTSD brains: the necessity of post-mortem brain tissue. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1341824. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1341824

18. Zunszain PA, Anacker C, Cattaneo A, et al. Glucocorticoids, cytokines and brain abnormalities in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):722-729.

19. Greeson JKP, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, et al. Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: findings from the national child traumatic stress network. Child Welfare. 2011;90(6):91-108.

20. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

21. American Psychological Association. PTSD assessment instruments. Updated September 26, 2018. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/assessment/

22. Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, et al. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e517-e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8

23. Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:721-732.

24. Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women. An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):953-959.

25. Chard KM, Gilman R. Counseling trauma victims: 4 brief therapies meet the test. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(8):50,55-58,61-62.

26. Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, American Psychological Association. Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. American Psychol. 2019;74(5):596-607.

27. American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. PTSD treatments. Updated June 2020. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/

28. Kip KE, Elk CA, Sullivan KL, et al. Brief treatment of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by use of accelerated resolution therapy (ART(®)). Behav Sci (Basel). 2012;2(2):115-134.

29. Steckler T, Risbrough V. Pharmacological treatment of PTSD - established and new approaches. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):617-627.

30. Davidson JR, Connor KM, Hertzberg MA, et al. Maintenance therapy with fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(2):166-169.

31. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):204-213.

32. Aerni A, Traber R, Hock C, et al. Low-dose cortisol for symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiat. 2004;161(8):1488-1490.

33. McGhee LL, Maani CV, Garza TH, et al. The correlation between ketamine and posttraumatic stress disorder in burned service members. J Trauma. 2008;64(2 suppl):S195-S198. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160ba1d

Childhood trauma, which is also called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), can have lasting detrimental effects on individuals as they grow and mature into adulthood. ACEs may occur in children age ≤18 years if they experience abuse or neglect, violence, or other traumatic losses. More than 60% of people experience at least 1 ACE, and 1 in 6 individuals reported that they had experienced ≥4 ACEs.1 Subsequent additional ACEs have a cumulative deteriorating impact on the brain. This predisposes individuals to mental health disorders, substance use disorders, and other psychosocial problems. The efficacy of current therapeutic approaches provides only partial symptom resolution. For such individuals, the illness load and health care costs typically remain high across the lifespan.1,2

In this article, we discuss types of ACEs, protective factors and risk factors that influence the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in individuals who experience ACEs, how ACEs can negatively impact mental health in adulthood, and approaches to prevent or treat PTSD and other symptoms.

Types of trauma and correlation with PTSD

ACEs can be indexed as neglect or emotional, physical, or sexual abuse. Physical and sexual abuse strongly correlate with an increased risk of PTSD.3 Although neglect and emotional abuse do not directly predict the development of PTSD, these experiences foretell high rates of lifelong trauma exposure and are indirectly related to late PTSD symptoms.4,5 ACEs can impede an individual’s cognitive, social, and emotional development, diminish quality of life, and lead to an early death.6 The lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 6.1% to 9.2%.7 Compared with men, women are 4 times more likely to develop PTSD following a traumatic event.7

The development of PTSD is influenced by the nature, duration, and degree of trauma, and age at the time of exposure to trauma. Children who survive complex trauma (≥2 types of trauma) have a higher likelihood of developing PTSD.8 Prolonged trauma exposure has a more substantial negative impact than a one-time occurrence. However, it is an erroneous oversimplification to assume that each type of ACE has an equally traumatic effect.6

Factors that protect against PTSD

Factors that can protect against developing PTSD are listed in Table 1.7 Two of these are resilience and hope.

Resilience is defined as an individual’s strength to cope with difficulties in life.9 Resilience has internal psychological characteristics and external factors that aid in protecting against childhood adversities.10,11 The Brief Resilience Scale is a self-assessment that measures innate abilities to cope, including optimism, self-efficacy, patience, faith, and humor.12,13 External factors associated with resilience are family, friends, and community support.11,13

Hope can help in surmounting ACEs. The Adult Hope Scale has been used in many studies to assess this construct in individuals who have survived trauma.13 Some studies have found decreased hope in individuals who sustained early trauma and were diagnosed with PTSD in adulthood.14 A study examining children exposed to domestic violence found that children who showed high hope, endurance, and curiosity were better able to cope with adversities.15

Continue to: PTSD risk factors

PTSD risk factors

Many individual and societal risk factors can influence the likelihood of developing PTSD. Some of these factors are outlined in Table 1.7

Pathophysiology of PTSD

Multiple brain regions, pathways, and neurotransmitters are involved in the development of PTSD. Neuroimaging has identified volume and activity changes of the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala in patients with early trauma and PTSD. Some researchers have suggested a gross reduction in locus coeruleus neuronal volume in war veterans with a likely diagnosis of PTSD compared with controls.16,17 In other studies, chronic stress exposure has been found to cause neuronal cell death and affect neuronal plasticity in the limbic area of the brain.18

Diagnosing PTSD

More than 30% of individuals who experience ACEs develop PTSD.19 The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD are outlined in Table 2.20 Several instruments are used to determine the diagnosis and assess the severity of PTSD. These include the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5,21 which is a 30-item structured interview that can be administered in 45 to 60 minutes; the PTSD Symptom Scale Self-Report Version, which is a 17-item, Likert scale, self-report questionnaire; and the Structured Clinical Interview: PTSD Module, which is a semi-structured interview that can take up to several hours to administer.21

Other disorders. In addition to PTSD, individuals with ACEs are at high risk for other mental health issues throughout their lifetime. Individuals with ACE often experience depressive symptoms (approximately 40%); anxiety (approximately 30%); anger; guilt or shame; negative self-cognition; interpersonal difficulties; rumination; and thoughts of self-harm and suicide.22 Epidemiological studies suggest that patients who experience childhood sexual abuse are more likely to develop mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in adulthood.23,24

Psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses the relationship between an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. CBT can be used to treat adults and children with PTSD. Before starting CBT, assess the patient’s current safety to ensure that they have the coping skills to manage distress related to their ACEs, and address any coexisting substance use.25

Continue to: According to the American Psychological Association...

According to the American Psychological Association, several CBT-based psychotherapies are recommended for treating PTSD26:

Trauma-focused–CBT includes psychoeducation, trauma narrative, processing, exposure, and relaxation skills training. It consists of approximately 12 to 16 sessions and incorporates elements of family therapy.

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) focuses on helping patients develop adaptive cognitive domains about the self, the people around them, and the world. CPT therapists assist in information processing by accessing the traumatic memory and trying to eliminate emotions tied to it.25,27 CPT consists of 12 to 16 structured individual, group, or combined sessions.

Prolonged exposure (PE) targets fear-related emotions and works on the principles of habituation to extinguish trauma and fear response to the trigger. This increases self-reliance and competence and decreases the generalization of anxiety to innocuous triggers. PE typically consists of 9 to 12 sessions. PE alone or in combination with cognitive restructuring is successful in treating patients with PTSD, but cognitive restructuring has limited utility in young children.25,27

Cognitive exposure can be individual or group therapy delivered over 3 months, where negative self-evaluation and traumatic memories are challenged with the goal of interrupting maladaptive behaviors and thoughts.27

Continue to: Stress inoculation training

Stress inoculation training (SIT) provides psychoeducation, skills training, role-playing, deep muscle relaxation, paced breathing, and thought stopping. Emphasis is on coaching skills to alleviate anxiety, fear, and symptoms of depression associated with trauma. In SIT, exposures to traumatic memories are indirect (eg, role play), compared with PE, where the exposures are direct.25

The American Psychological Association conditionally recommended several other forms for psychotherapy for treating patients with PTSD26:

Brief eclectic psychotherapy uses CBT and psychodynamic approaches to target feelings of guilt and shame in 16 sessions.27

Narrative exposure therapy consists of 4 to 10 group sessions in which individuals provide detailed narration of the events; the focus is on self-respect and personal rights.27

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a 6- to 12-session, 8-phase treatment that uses principles of accelerated information processing to target nonverbal expression of trauma and dissociative experiences. Patients with PTSD are suggested to have disrupted rapid eye movements. In EMDR, patients follow rhythmic movements of the therapist’s hands or flashed light. This is designed to decrease stress associated with accessing trauma memories, the emotional/physiologic response from the memories, and negative cognitive distortions about self, and to replace negative cognition distortions with positive thoughts about self.25,27

Continue to: Accelerated resolution therapy

Accelerated resolution therapy is a derivative of EMDR. It helps to reconsolidate the emotional and physical experiences associated with distressing memories by replacing them with positive ones or decreasing physiological arousal and anxiety related to the recall of traumatic memories.28

Pharmacologic treatments

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Multiple studies using different scales have found that paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine can decrease PTSD symptoms. Approximately 60% of patients treated with SSRIs experience partial remission of symptoms, and 20% to 30% experience complete symptom resolution.29 Davidson et al30 found that 22% of patients with PTSD who received fluoxetine had a relapse of symptoms, compared with 50% of patients who received placebo.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other antidepressants. The SNRIs venlafaxine and duloxetine can help reduce hyperarousal symptoms and improve mood, anxiety, and sleep.26 Mirtazapine, an alpha 2A/2C adrenoceptor antagonist/5-HT 2A/2C/3 antagonist, can address PTSD symptoms from both serotonergic pathways and increase norepinephrine release by blocking autoreceptors and enhancing alpha-1 receptor activity. This alleviates hyperarousal symptoms and promotes sleep.29 In addition to having monoaminergic effects, antidepressant medications also regulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis response to stress and promote neurogenesis in the hippocampal region.29

Adrenergic agents

Adrenergic receptor antagonists. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist, decreases hyperarousal symptoms, improves sleep, and decreases nightmares related to PTSD by decreasing noradrenergic hyperactivity.29

Beta-blockers such as propranolol can decrease physiological response to trauma but have mixed results in the prevention or improvement of PTSD symptoms.29,31

Continue to: Glucocorticoid receptor agonists

Glucocorticoid receptor agonists. In a very small study, low-dose cortisol decreased the severity of traumatic memory (consolidation phase).32 Glucocorticoid receptor agonists can also diminish memory retrieval (reconsolidation phase) through intrusive thoughts and flashbacks.29

Anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics

These medications have had a limited role in the treatment of PTSD.26,29

Future directions: Preventive treatments

Because PTSD has a profound impact on an individual’s quality of life and the development of other illnesses, there is strong interest in finding treatments that can prevent PTSD. Based on limited evidence primarily from animal studies, some researchers have suggested that certain agents may someday be helpful for PTSD prevention29:

Glucocorticoid antagonists such as corticotropin-releasing factor 1 (CRF1) antagonists or cholecystokinin 2 (CCK2) receptor antagonists might promote resilience to stress by inhibiting the HPA axis and influencing the amygdala by decreasing fear conditioning, as observed in animal models. Similarly, in animal models, CRF1 and CCK2 are predicted to decrease memory consolidation in response to exposure to stress.

Adrenoceptor antagonists and agonists also might have a role in preventive treatment, but the evidence is scarce. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist, was ineffective in animal models.29,31 Propranolol, a beta-adrenoceptor blocker, has had mixed results but can decrease trauma-induced physiological arousal when administered soon after exposure.29

Continue to: N-methyl-

N-methyl-

Bottom Line

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are strong predictors for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health or medical issues in late adolescence and adulthood. Experiencing a higher number of ACEs increases the risk of developing PTSD as an adult. Timely psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic interventions can help limit symptoms and reduce the severity of PTSD.

Related Resources

- Smith P, Dalglesih T, Meiser-Stedman R. Practitioner review: posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(5):500-515.

- North CS, Hong BA, Downs DL. PTSD: a systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment. Current Psychiatry 2018;17(4):35-43.

Drug Brand Names

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal, Pronol

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Childhood trauma, which is also called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), can have lasting detrimental effects on individuals as they grow and mature into adulthood. ACEs may occur in children age ≤18 years if they experience abuse or neglect, violence, or other traumatic losses. More than 60% of people experience at least 1 ACE, and 1 in 6 individuals reported that they had experienced ≥4 ACEs.1 Subsequent additional ACEs have a cumulative deteriorating impact on the brain. This predisposes individuals to mental health disorders, substance use disorders, and other psychosocial problems. The efficacy of current therapeutic approaches provides only partial symptom resolution. For such individuals, the illness load and health care costs typically remain high across the lifespan.1,2

In this article, we discuss types of ACEs, protective factors and risk factors that influence the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in individuals who experience ACEs, how ACEs can negatively impact mental health in adulthood, and approaches to prevent or treat PTSD and other symptoms.

Types of trauma and correlation with PTSD

ACEs can be indexed as neglect or emotional, physical, or sexual abuse. Physical and sexual abuse strongly correlate with an increased risk of PTSD.3 Although neglect and emotional abuse do not directly predict the development of PTSD, these experiences foretell high rates of lifelong trauma exposure and are indirectly related to late PTSD symptoms.4,5 ACEs can impede an individual’s cognitive, social, and emotional development, diminish quality of life, and lead to an early death.6 The lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 6.1% to 9.2%.7 Compared with men, women are 4 times more likely to develop PTSD following a traumatic event.7

The development of PTSD is influenced by the nature, duration, and degree of trauma, and age at the time of exposure to trauma. Children who survive complex trauma (≥2 types of trauma) have a higher likelihood of developing PTSD.8 Prolonged trauma exposure has a more substantial negative impact than a one-time occurrence. However, it is an erroneous oversimplification to assume that each type of ACE has an equally traumatic effect.6

Factors that protect against PTSD

Factors that can protect against developing PTSD are listed in Table 1.7 Two of these are resilience and hope.

Resilience is defined as an individual’s strength to cope with difficulties in life.9 Resilience has internal psychological characteristics and external factors that aid in protecting against childhood adversities.10,11 The Brief Resilience Scale is a self-assessment that measures innate abilities to cope, including optimism, self-efficacy, patience, faith, and humor.12,13 External factors associated with resilience are family, friends, and community support.11,13

Hope can help in surmounting ACEs. The Adult Hope Scale has been used in many studies to assess this construct in individuals who have survived trauma.13 Some studies have found decreased hope in individuals who sustained early trauma and were diagnosed with PTSD in adulthood.14 A study examining children exposed to domestic violence found that children who showed high hope, endurance, and curiosity were better able to cope with adversities.15

Continue to: PTSD risk factors

PTSD risk factors

Many individual and societal risk factors can influence the likelihood of developing PTSD. Some of these factors are outlined in Table 1.7

Pathophysiology of PTSD

Multiple brain regions, pathways, and neurotransmitters are involved in the development of PTSD. Neuroimaging has identified volume and activity changes of the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala in patients with early trauma and PTSD. Some researchers have suggested a gross reduction in locus coeruleus neuronal volume in war veterans with a likely diagnosis of PTSD compared with controls.16,17 In other studies, chronic stress exposure has been found to cause neuronal cell death and affect neuronal plasticity in the limbic area of the brain.18

Diagnosing PTSD

More than 30% of individuals who experience ACEs develop PTSD.19 The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD are outlined in Table 2.20 Several instruments are used to determine the diagnosis and assess the severity of PTSD. These include the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5,21 which is a 30-item structured interview that can be administered in 45 to 60 minutes; the PTSD Symptom Scale Self-Report Version, which is a 17-item, Likert scale, self-report questionnaire; and the Structured Clinical Interview: PTSD Module, which is a semi-structured interview that can take up to several hours to administer.21

Other disorders. In addition to PTSD, individuals with ACEs are at high risk for other mental health issues throughout their lifetime. Individuals with ACE often experience depressive symptoms (approximately 40%); anxiety (approximately 30%); anger; guilt or shame; negative self-cognition; interpersonal difficulties; rumination; and thoughts of self-harm and suicide.22 Epidemiological studies suggest that patients who experience childhood sexual abuse are more likely to develop mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in adulthood.23,24

Psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses the relationship between an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. CBT can be used to treat adults and children with PTSD. Before starting CBT, assess the patient’s current safety to ensure that they have the coping skills to manage distress related to their ACEs, and address any coexisting substance use.25

Continue to: According to the American Psychological Association...

According to the American Psychological Association, several CBT-based psychotherapies are recommended for treating PTSD26:

Trauma-focused–CBT includes psychoeducation, trauma narrative, processing, exposure, and relaxation skills training. It consists of approximately 12 to 16 sessions and incorporates elements of family therapy.

Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) focuses on helping patients develop adaptive cognitive domains about the self, the people around them, and the world. CPT therapists assist in information processing by accessing the traumatic memory and trying to eliminate emotions tied to it.25,27 CPT consists of 12 to 16 structured individual, group, or combined sessions.

Prolonged exposure (PE) targets fear-related emotions and works on the principles of habituation to extinguish trauma and fear response to the trigger. This increases self-reliance and competence and decreases the generalization of anxiety to innocuous triggers. PE typically consists of 9 to 12 sessions. PE alone or in combination with cognitive restructuring is successful in treating patients with PTSD, but cognitive restructuring has limited utility in young children.25,27

Cognitive exposure can be individual or group therapy delivered over 3 months, where negative self-evaluation and traumatic memories are challenged with the goal of interrupting maladaptive behaviors and thoughts.27

Continue to: Stress inoculation training

Stress inoculation training (SIT) provides psychoeducation, skills training, role-playing, deep muscle relaxation, paced breathing, and thought stopping. Emphasis is on coaching skills to alleviate anxiety, fear, and symptoms of depression associated with trauma. In SIT, exposures to traumatic memories are indirect (eg, role play), compared with PE, where the exposures are direct.25

The American Psychological Association conditionally recommended several other forms for psychotherapy for treating patients with PTSD26:

Brief eclectic psychotherapy uses CBT and psychodynamic approaches to target feelings of guilt and shame in 16 sessions.27

Narrative exposure therapy consists of 4 to 10 group sessions in which individuals provide detailed narration of the events; the focus is on self-respect and personal rights.27

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a 6- to 12-session, 8-phase treatment that uses principles of accelerated information processing to target nonverbal expression of trauma and dissociative experiences. Patients with PTSD are suggested to have disrupted rapid eye movements. In EMDR, patients follow rhythmic movements of the therapist’s hands or flashed light. This is designed to decrease stress associated with accessing trauma memories, the emotional/physiologic response from the memories, and negative cognitive distortions about self, and to replace negative cognition distortions with positive thoughts about self.25,27

Continue to: Accelerated resolution therapy

Accelerated resolution therapy is a derivative of EMDR. It helps to reconsolidate the emotional and physical experiences associated with distressing memories by replacing them with positive ones or decreasing physiological arousal and anxiety related to the recall of traumatic memories.28

Pharmacologic treatments

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Multiple studies using different scales have found that paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine can decrease PTSD symptoms. Approximately 60% of patients treated with SSRIs experience partial remission of symptoms, and 20% to 30% experience complete symptom resolution.29 Davidson et al30 found that 22% of patients with PTSD who received fluoxetine had a relapse of symptoms, compared with 50% of patients who received placebo.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other antidepressants. The SNRIs venlafaxine and duloxetine can help reduce hyperarousal symptoms and improve mood, anxiety, and sleep.26 Mirtazapine, an alpha 2A/2C adrenoceptor antagonist/5-HT 2A/2C/3 antagonist, can address PTSD symptoms from both serotonergic pathways and increase norepinephrine release by blocking autoreceptors and enhancing alpha-1 receptor activity. This alleviates hyperarousal symptoms and promotes sleep.29 In addition to having monoaminergic effects, antidepressant medications also regulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis response to stress and promote neurogenesis in the hippocampal region.29

Adrenergic agents

Adrenergic receptor antagonists. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist, decreases hyperarousal symptoms, improves sleep, and decreases nightmares related to PTSD by decreasing noradrenergic hyperactivity.29

Beta-blockers such as propranolol can decrease physiological response to trauma but have mixed results in the prevention or improvement of PTSD symptoms.29,31

Continue to: Glucocorticoid receptor agonists

Glucocorticoid receptor agonists. In a very small study, low-dose cortisol decreased the severity of traumatic memory (consolidation phase).32 Glucocorticoid receptor agonists can also diminish memory retrieval (reconsolidation phase) through intrusive thoughts and flashbacks.29

Anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics

These medications have had a limited role in the treatment of PTSD.26,29

Future directions: Preventive treatments

Because PTSD has a profound impact on an individual’s quality of life and the development of other illnesses, there is strong interest in finding treatments that can prevent PTSD. Based on limited evidence primarily from animal studies, some researchers have suggested that certain agents may someday be helpful for PTSD prevention29:

Glucocorticoid antagonists such as corticotropin-releasing factor 1 (CRF1) antagonists or cholecystokinin 2 (CCK2) receptor antagonists might promote resilience to stress by inhibiting the HPA axis and influencing the amygdala by decreasing fear conditioning, as observed in animal models. Similarly, in animal models, CRF1 and CCK2 are predicted to decrease memory consolidation in response to exposure to stress.

Adrenoceptor antagonists and agonists also might have a role in preventive treatment, but the evidence is scarce. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenoceptor antagonist, was ineffective in animal models.29,31 Propranolol, a beta-adrenoceptor blocker, has had mixed results but can decrease trauma-induced physiological arousal when administered soon after exposure.29

Continue to: N-methyl-

N-methyl-

Bottom Line

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are strong predictors for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health or medical issues in late adolescence and adulthood. Experiencing a higher number of ACEs increases the risk of developing PTSD as an adult. Timely psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic interventions can help limit symptoms and reduce the severity of PTSD.

Related Resources

- Smith P, Dalglesih T, Meiser-Stedman R. Practitioner review: posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(5):500-515.

- North CS, Hong BA, Downs DL. PTSD: a systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment. Current Psychiatry 2018;17(4):35-43.

Drug Brand Names

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal, Pronol

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing adverse childhood experiences. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/aces/fastfact.html

2. Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:378-385.

3. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, et al. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

4. Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, et al. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(11):1247-1258.

5. Glück TM, Knefel M, Lueger-Schuster B. A network analysis of anger, shame, proposed ICD-11 post-traumatic stress disorder, and different types of childhood trauma in foster care settings in a sample of adult survivors. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(suppl 3):1372543. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1372543

6. Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, et al. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1453-1460.

7. Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated December 3, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-in-adults-epidemiology-pathophysiology-clinical-manifestations-course-assessment-and-diagnosis

8. Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999:156;1223-1229.

9. Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(3):316-331.

10. Ahern NR, Kiehl EM, Sole ML, et al. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2006;29(2):103-125.

11. Zimmerman MA. Resiliency theory: a strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):381-383.

12. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82.

13. Munoz RT, Hanks H, Hellman CM. Hope and resilience as distinct contributors to psychological flourishing among childhood trauma survivors. Traumatology. 2020;26(2):177-184.

14. Baxter MA, Hemming EJ, McIntosh HC, et al. Exploring the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and hope. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(8):948-956.

15. Hellman CM, Gwinn C. Camp HOPE as an intervention for children exposed to domestic violence: a program evaluation of hope, and strength of character. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2017;34:269-276.

16. Bracha HS, Garcia-Rill E, Mrak RE, et al. Postmortem locus coeruleus neuron count in three American veterans with probable or possible war-related PTSD. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(4):503-9.

17. de Lange GM. Understanding the cellular and molecular alterations in PTSD brains: the necessity of post-mortem brain tissue. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1341824. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1341824

18. Zunszain PA, Anacker C, Cattaneo A, et al. Glucocorticoids, cytokines and brain abnormalities in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):722-729.

19. Greeson JKP, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, et al. Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: findings from the national child traumatic stress network. Child Welfare. 2011;90(6):91-108.

20. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

21. American Psychological Association. PTSD assessment instruments. Updated September 26, 2018. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/assessment/

22. Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, et al. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e517-e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8

23. Mullen PE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and mental health in adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:721-732.

24. Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women. An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):953-959.

25. Chard KM, Gilman R. Counseling trauma victims: 4 brief therapies meet the test. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(8):50,55-58,61-62.

26. Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, American Psychological Association. Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. American Psychol. 2019;74(5):596-607.

27. American Psychological Association. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. PTSD treatments. Updated June 2020. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/

28. Kip KE, Elk CA, Sullivan KL, et al. Brief treatment of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by use of accelerated resolution therapy (ART(®)). Behav Sci (Basel). 2012;2(2):115-134.

29. Steckler T, Risbrough V. Pharmacological treatment of PTSD - established and new approaches. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(2):617-627.

30. Davidson JR, Connor KM, Hertzberg MA, et al. Maintenance therapy with fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(2):166-169.

31. Benedek DM, Friedman MJ, Zatzick D, et al. Guideline watch (March 2009): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Focus. 2009;7(2):204-213.

32. Aerni A, Traber R, Hock C, et al. Low-dose cortisol for symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiat. 2004;161(8):1488-1490.

33. McGhee LL, Maani CV, Garza TH, et al. The correlation between ketamine and posttraumatic stress disorder in burned service members. J Trauma. 2008;64(2 suppl):S195-S198. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160ba1d

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing adverse childhood experiences. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/aces/fastfact.html

2. Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:378-385.

3. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, et al. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

4. Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, et al. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(11):1247-1258.

5. Glück TM, Knefel M, Lueger-Schuster B. A network analysis of anger, shame, proposed ICD-11 post-traumatic stress disorder, and different types of childhood trauma in foster care settings in a sample of adult survivors. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(suppl 3):1372543. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1372543

6. Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, et al. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1453-1460.

7. Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated December 3, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-in-adults-epidemiology-pathophysiology-clinical-manifestations-course-assessment-and-diagnosis

8. Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999:156;1223-1229.

9. Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57(3):316-331.

10. Ahern NR, Kiehl EM, Sole ML, et al. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2006;29(2):103-125.

11. Zimmerman MA. Resiliency theory: a strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(4):381-383.

12. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82.

13. Munoz RT, Hanks H, Hellman CM. Hope and resilience as distinct contributors to psychological flourishing among childhood trauma survivors. Traumatology. 2020;26(2):177-184.

14. Baxter MA, Hemming EJ, McIntosh HC, et al. Exploring the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and hope. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(8):948-956.

15. Hellman CM, Gwinn C. Camp HOPE as an intervention for children exposed to domestic violence: a program evaluation of hope, and strength of character. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2017;34:269-276.