User login

Baseline neuromotor abnormalities persist in schizophrenia

Neuromotor abnormalities in psychotic disorders have long been ignored as side effects of antipsychotic drugs, but they are gaining new attention as a component of the disease process, with implications for outcomes and management, wrote Victor Peralta, MD, PhD, of Servicio Navarro de Salud, Pamplona, Spain, and colleagues.

Previous research has suggested links between increased levels of parkinsonism, dyskinesia, and NSS and poor symptomatic and functional outcomes, but “the impact of primary neuromotor dysfunction on the long-term course and outcome of psychotic disorders remains largely unknown,” they said.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research , the investigators identified 243 consecutive schizophrenia patients admitted to a psychiatric ward at a single center.

Patients were assessed at baseline for variables including parkinsonism, dyskinesia, NSS, and catatonia, and were reassessed 21 years later for the same variables, along with psychopathology, functioning, personal recovery, cognitive performance, and comorbidity.

Overall, baseline dyskinesia and NSS measures were stable over time, with Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) of 0.92 and 0.86, respectively, while rating stability was low for parkinsonism and catatonia (ICC = 0.42 and 0.31, respectively).

Baseline dyskinesia and NSS each were independent predictors of more positive and negative symptoms, poor functioning, and less personal recovery at 21 years. In a multivariate model, neuromotor dysfunction at follow-up was significantly associated with family history of schizophrenia, obstetric complications, neurodevelopmental delay, and premorbid IQ, as well as baseline dyskinesia and NSS; “these variables explained 51% of the variance in the neuromotor outcome, 35% of which corresponded to baseline dyskinesia and NSS,” the researchers said. As for other outcomes, baseline neuromotor ratings predicted a range from 4% for medical comorbidity to 15% for cognitive impairment.

“The distinction between primary and drug-induced neuromotor dysfunction is a very complex issue, mainly because antipsychotic drugs may cause de novo motor dysfunction, such as improve or worsen the disease-based motor dysfunction,” the researchers explained in their discussion.

Baseline parkinsonism, dyskinesia, and NSS were significantly related to increased risk of antipsychotic exposure over the illness course, possibly because primary neuromotor dysfunction was predictive of greater severity of illness in general, which confounds differentiation between primary and drug-induced motor symptoms, they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including potential selection bias because of the selection of first-admission psychosis, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the use of standard clinical rating scales rather than instrumental procedures to measuring neuromotor abnormalities.

However, “our findings confirm the significance of baseline and follow-up neuromotor abnormalities as a core dimension of psychosis,” and future studies “should complement clinical rating scales with instrumental assessment to capture neuromotor dysfunction more comprehensively,” they said.

The results highlight the clinical relevance of examining neuromotor abnormalities as a routine part of practice prior to starting antipsychotics because of their potential as predictors of long-term outcomes “and to disentangle the primary versus drug-induced character of neuromotor impairment in treated patients,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness, and the Regional Government of Navarra. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Neuromotor abnormalities in psychotic disorders have long been ignored as side effects of antipsychotic drugs, but they are gaining new attention as a component of the disease process, with implications for outcomes and management, wrote Victor Peralta, MD, PhD, of Servicio Navarro de Salud, Pamplona, Spain, and colleagues.

Previous research has suggested links between increased levels of parkinsonism, dyskinesia, and NSS and poor symptomatic and functional outcomes, but “the impact of primary neuromotor dysfunction on the long-term course and outcome of psychotic disorders remains largely unknown,” they said.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research , the investigators identified 243 consecutive schizophrenia patients admitted to a psychiatric ward at a single center.

Patients were assessed at baseline for variables including parkinsonism, dyskinesia, NSS, and catatonia, and were reassessed 21 years later for the same variables, along with psychopathology, functioning, personal recovery, cognitive performance, and comorbidity.

Overall, baseline dyskinesia and NSS measures were stable over time, with Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) of 0.92 and 0.86, respectively, while rating stability was low for parkinsonism and catatonia (ICC = 0.42 and 0.31, respectively).

Baseline dyskinesia and NSS each were independent predictors of more positive and negative symptoms, poor functioning, and less personal recovery at 21 years. In a multivariate model, neuromotor dysfunction at follow-up was significantly associated with family history of schizophrenia, obstetric complications, neurodevelopmental delay, and premorbid IQ, as well as baseline dyskinesia and NSS; “these variables explained 51% of the variance in the neuromotor outcome, 35% of which corresponded to baseline dyskinesia and NSS,” the researchers said. As for other outcomes, baseline neuromotor ratings predicted a range from 4% for medical comorbidity to 15% for cognitive impairment.

“The distinction between primary and drug-induced neuromotor dysfunction is a very complex issue, mainly because antipsychotic drugs may cause de novo motor dysfunction, such as improve or worsen the disease-based motor dysfunction,” the researchers explained in their discussion.

Baseline parkinsonism, dyskinesia, and NSS were significantly related to increased risk of antipsychotic exposure over the illness course, possibly because primary neuromotor dysfunction was predictive of greater severity of illness in general, which confounds differentiation between primary and drug-induced motor symptoms, they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including potential selection bias because of the selection of first-admission psychosis, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the use of standard clinical rating scales rather than instrumental procedures to measuring neuromotor abnormalities.

However, “our findings confirm the significance of baseline and follow-up neuromotor abnormalities as a core dimension of psychosis,” and future studies “should complement clinical rating scales with instrumental assessment to capture neuromotor dysfunction more comprehensively,” they said.

The results highlight the clinical relevance of examining neuromotor abnormalities as a routine part of practice prior to starting antipsychotics because of their potential as predictors of long-term outcomes “and to disentangle the primary versus drug-induced character of neuromotor impairment in treated patients,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness, and the Regional Government of Navarra. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Neuromotor abnormalities in psychotic disorders have long been ignored as side effects of antipsychotic drugs, but they are gaining new attention as a component of the disease process, with implications for outcomes and management, wrote Victor Peralta, MD, PhD, of Servicio Navarro de Salud, Pamplona, Spain, and colleagues.

Previous research has suggested links between increased levels of parkinsonism, dyskinesia, and NSS and poor symptomatic and functional outcomes, but “the impact of primary neuromotor dysfunction on the long-term course and outcome of psychotic disorders remains largely unknown,” they said.

In a study published in Schizophrenia Research , the investigators identified 243 consecutive schizophrenia patients admitted to a psychiatric ward at a single center.

Patients were assessed at baseline for variables including parkinsonism, dyskinesia, NSS, and catatonia, and were reassessed 21 years later for the same variables, along with psychopathology, functioning, personal recovery, cognitive performance, and comorbidity.

Overall, baseline dyskinesia and NSS measures were stable over time, with Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) of 0.92 and 0.86, respectively, while rating stability was low for parkinsonism and catatonia (ICC = 0.42 and 0.31, respectively).

Baseline dyskinesia and NSS each were independent predictors of more positive and negative symptoms, poor functioning, and less personal recovery at 21 years. In a multivariate model, neuromotor dysfunction at follow-up was significantly associated with family history of schizophrenia, obstetric complications, neurodevelopmental delay, and premorbid IQ, as well as baseline dyskinesia and NSS; “these variables explained 51% of the variance in the neuromotor outcome, 35% of which corresponded to baseline dyskinesia and NSS,” the researchers said. As for other outcomes, baseline neuromotor ratings predicted a range from 4% for medical comorbidity to 15% for cognitive impairment.

“The distinction between primary and drug-induced neuromotor dysfunction is a very complex issue, mainly because antipsychotic drugs may cause de novo motor dysfunction, such as improve or worsen the disease-based motor dysfunction,” the researchers explained in their discussion.

Baseline parkinsonism, dyskinesia, and NSS were significantly related to increased risk of antipsychotic exposure over the illness course, possibly because primary neuromotor dysfunction was predictive of greater severity of illness in general, which confounds differentiation between primary and drug-induced motor symptoms, they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including potential selection bias because of the selection of first-admission psychosis, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the use of standard clinical rating scales rather than instrumental procedures to measuring neuromotor abnormalities.

However, “our findings confirm the significance of baseline and follow-up neuromotor abnormalities as a core dimension of psychosis,” and future studies “should complement clinical rating scales with instrumental assessment to capture neuromotor dysfunction more comprehensively,” they said.

The results highlight the clinical relevance of examining neuromotor abnormalities as a routine part of practice prior to starting antipsychotics because of their potential as predictors of long-term outcomes “and to disentangle the primary versus drug-induced character of neuromotor impairment in treated patients,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness, and the Regional Government of Navarra. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SCHIZOPHRENIA RESEARCH

Subtle visual dysfunctions often precede early-stage psychosis

A multinational group of investigators found that VisDys were reported considerably more often by patients with recent-onset psychosis and CHR than by those with recent-onset depression or a group acting as healthy control participants.

In addition, vision problems of higher severity were associated with less functional remission both for patients at CHR and those with recent-onset psychosis. Among patients with CHR, VisDys was also linked to lower quality of life (QOL), higher depressiveness, and more severe impairment of visuospatial constructability.

The researchers used fMRI imaging to compare resting-state functional brain connectivity in participants with recent-onset psychosis, CHR, and recent-onset depression. They found that the occipital (ON) and frontoparietal (FPN) subnetworks were particularly implicated in VisDys.

“Subtle VisDys should be regarded as a frequent phenomenon across the psychosis spectrum, impinging negatively on patients’ current ability to function in several settings of their daily and social life, their QOL, and visuospatial abilities,” write investigators led by Johanna Schwarzer, Institute for Translational Psychiatry, University of Muenster (Germany).

“These large-sample study findings suggest that VisDys are clinically highly relevant not only in [recent-onset psychosis] but especially in CHR,” they stated.

The findings were published online in Neuropsychopharmacology.

Subtle, underrecognized

Unlike patients with nonpsychotic disorders, approximately 50%-60% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia report VisDys involving brightness, motion, form, color perception, or distorted perception of their own face, the researchers reported.

These “subtle” VisDys are “often underrecognized during clinical examination, despite their clinical relevance related to suicidal ideation, cognitive impairment, or poorer treatment response,” they wrote.

Most research into these vision problems in patients with schizophrenia has focused on patients in which the illness is in a stable, chronic state – although VisDys often appear years before the diagnosis of a psychotic disorder.

Moreover, there has been little research into the neurobiological underpinnings of VisDys, specifically in early states of psychosis and/or in comparison to other disorders, such as depression.

The Personalised Prognostic Indicators for Early Psychosis Management (PRONIA) Consortium studied the psychophysiological phenomenon of VisDys in a large sample of adolescents and young adults. The sample consisted of three diagnostic groups: those with recent-onset psychosis, those with CHR, and those with recent-onset depression.

VisDys in daily life were measured using the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument–Adult Scale (SPI-A), which assesses basic symptoms that indicate increased risk for psychosis.

Visual information processing

Resting-state imaging data on intrinsic brain networks were also assessed in the PRONIA sample and were analyzed across 12,720 functional connectivities between 160 regions of interest across the whole brain.

In particular, the researchers were interested in the primary networks involved in visual information processing, especially the dorsal visual stream, with further focus on the ON and FPN intrinsic subnetworks.

The ON was chosen because it comprises “primary visual processing pathways,” while the FPN is “widely suggested to modulate attention related to visual information processing at higher cognitive levels.”

The investigators used a machine-learning multivariate pattern analysis approach that “enables the consideration of multiple interactions within brain systems.”

The current study involved 721 participants from the PRONIA database, including 147 participants with recent-onset psychosis (mean age, 28.45 years; 60.5% men), 143 with CHR (mean age, 26.97 years; about 50% men), 151 with recent-onset depression (mean age, 29.13 years; 47% men), and 280 in the healthy-controls group (mean age, 28.54 years; 39.4% men).

The researchers selected 14 items to assess from the SPI-A that represented different aspects of VisDys. Severity was defined by the maximum frequency within the past 3 months – from 1 (never) to 6 (daily).

The 14 items were as follows: oversensitivity to light and/or certain visual perception objects, photopsia, micropsia/macropsia, near and tele-vision, metamorphopsia, changes in color vision, altered perception of a patient’s own face, pseudomovements of optic stimuli, diplopia or oblique vision, disturbances of the estimation of distances or sizes, disturbances of the perception of straight lines/contours, maintenance of optic stimuli “visual echoes,” partial seeing (including tubular vision), and captivation of attention by details of the visual field.

Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory–II scale (BDI-II), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Functional Remission in General Schizophrenia, and several other scales that measure global and social functioning.

Other assessments included QOL and the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, which is a neuropsychological measurement of visuospatial constructability.

Specific to early-stage psychosis?

Results showed that VisDys were reported more frequently in both recent-onset psychosis and CHR groups compared with the recent-onset depression and healthy control groups (50.34% and 55.94% vs. 16.56% and 4.28%, respectively).

The investigators noted that VisDys sum scores “showed high internal consistency” (Cronbachs alpha, 0.78 over all participants).

Among those with recent-onset psychosis, a higher VisDys sum score was correlated with lower scores for functional remission (P = .036) and social functioning (P = .014).

In CHR, higher VisDys sum scores were associated with lower scores for health-related functional remission (P = .024), lower physical and psychological QOL (P = .004 and P = .015, respectively), more severe depression on the BDI-II (P = .021), and more impaired visuospatial constructability (P = .027).

Among those with recent-onset depression and their healthy peers, “no relevant correlations were found between VisDys sum scores and any parameters representing functional remission, QOL, depressiveness, or visuospatial constructability,” the researchers wrote.

A total of 135 participants with recent-onset psychosis, 128 with CHR, and 134 with recent-onset depression also underwent resting-state fMRI.

ON functional connectivity predicted presence of VisDys in patients with recent-onset psychosis and those with CHR, with a balanced accuracy of 60.17% (P = .0001) and 67.38% (P = .029), respectively. In the combined recent-onset psychosis plus CHR sample, VisDys were predicted by FPN functional connectivity (balanced accuracy, 61.1%; P = .006).

“Findings from multivariate pattern analysis support a model of functional integrity within ON and FPN driving the VisDys phenomenon and being implicated in core disease mechanisms of early psychosis states,” the investigators noted.

“The main findings from this large sample study support the idea of VisDys being specific to the psychosis spectrum already at early stages,” while being less frequently reported in recent-onset depression, they wrote. VisDys also “appeared negligible” among those without psychiatric disorders.

Regular assessment needed

Steven Silverstein, PhD, professor of biopsychosocial medicine and professor of psychiatry, neuroscience, and ophthalmology, Center for Visual Science, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, called the findings “important” because “they will increase appreciation in the field of mental health for the frequency and disabling nature of visual symptoms and the need for regular assessment in routine clinical practice with people at risk for or with psychotic disorders.”

In addition, “the brain imaging findings are providing needed information that could lead to treatments that target the brain networks generating the visual symptoms,” such as neurofeedback or brain stimulation, said Dr. Silverstein, who was not involved with the research.

The study was funded by a grant for the PRONIA Consortium. Individual researchers received funding from NARSAD Young Investigator Award of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Koeln Fortune Program/Faculty of Medicine, the University of Cologne, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. Open Access funding was enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Ms. Schwarzer and Dr. Silverstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A multinational group of investigators found that VisDys were reported considerably more often by patients with recent-onset psychosis and CHR than by those with recent-onset depression or a group acting as healthy control participants.

In addition, vision problems of higher severity were associated with less functional remission both for patients at CHR and those with recent-onset psychosis. Among patients with CHR, VisDys was also linked to lower quality of life (QOL), higher depressiveness, and more severe impairment of visuospatial constructability.

The researchers used fMRI imaging to compare resting-state functional brain connectivity in participants with recent-onset psychosis, CHR, and recent-onset depression. They found that the occipital (ON) and frontoparietal (FPN) subnetworks were particularly implicated in VisDys.

“Subtle VisDys should be regarded as a frequent phenomenon across the psychosis spectrum, impinging negatively on patients’ current ability to function in several settings of their daily and social life, their QOL, and visuospatial abilities,” write investigators led by Johanna Schwarzer, Institute for Translational Psychiatry, University of Muenster (Germany).

“These large-sample study findings suggest that VisDys are clinically highly relevant not only in [recent-onset psychosis] but especially in CHR,” they stated.

The findings were published online in Neuropsychopharmacology.

Subtle, underrecognized

Unlike patients with nonpsychotic disorders, approximately 50%-60% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia report VisDys involving brightness, motion, form, color perception, or distorted perception of their own face, the researchers reported.

These “subtle” VisDys are “often underrecognized during clinical examination, despite their clinical relevance related to suicidal ideation, cognitive impairment, or poorer treatment response,” they wrote.

Most research into these vision problems in patients with schizophrenia has focused on patients in which the illness is in a stable, chronic state – although VisDys often appear years before the diagnosis of a psychotic disorder.

Moreover, there has been little research into the neurobiological underpinnings of VisDys, specifically in early states of psychosis and/or in comparison to other disorders, such as depression.

The Personalised Prognostic Indicators for Early Psychosis Management (PRONIA) Consortium studied the psychophysiological phenomenon of VisDys in a large sample of adolescents and young adults. The sample consisted of three diagnostic groups: those with recent-onset psychosis, those with CHR, and those with recent-onset depression.

VisDys in daily life were measured using the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument–Adult Scale (SPI-A), which assesses basic symptoms that indicate increased risk for psychosis.

Visual information processing

Resting-state imaging data on intrinsic brain networks were also assessed in the PRONIA sample and were analyzed across 12,720 functional connectivities between 160 regions of interest across the whole brain.

In particular, the researchers were interested in the primary networks involved in visual information processing, especially the dorsal visual stream, with further focus on the ON and FPN intrinsic subnetworks.

The ON was chosen because it comprises “primary visual processing pathways,” while the FPN is “widely suggested to modulate attention related to visual information processing at higher cognitive levels.”

The investigators used a machine-learning multivariate pattern analysis approach that “enables the consideration of multiple interactions within brain systems.”

The current study involved 721 participants from the PRONIA database, including 147 participants with recent-onset psychosis (mean age, 28.45 years; 60.5% men), 143 with CHR (mean age, 26.97 years; about 50% men), 151 with recent-onset depression (mean age, 29.13 years; 47% men), and 280 in the healthy-controls group (mean age, 28.54 years; 39.4% men).

The researchers selected 14 items to assess from the SPI-A that represented different aspects of VisDys. Severity was defined by the maximum frequency within the past 3 months – from 1 (never) to 6 (daily).

The 14 items were as follows: oversensitivity to light and/or certain visual perception objects, photopsia, micropsia/macropsia, near and tele-vision, metamorphopsia, changes in color vision, altered perception of a patient’s own face, pseudomovements of optic stimuli, diplopia or oblique vision, disturbances of the estimation of distances or sizes, disturbances of the perception of straight lines/contours, maintenance of optic stimuli “visual echoes,” partial seeing (including tubular vision), and captivation of attention by details of the visual field.

Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory–II scale (BDI-II), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Functional Remission in General Schizophrenia, and several other scales that measure global and social functioning.

Other assessments included QOL and the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, which is a neuropsychological measurement of visuospatial constructability.

Specific to early-stage psychosis?

Results showed that VisDys were reported more frequently in both recent-onset psychosis and CHR groups compared with the recent-onset depression and healthy control groups (50.34% and 55.94% vs. 16.56% and 4.28%, respectively).

The investigators noted that VisDys sum scores “showed high internal consistency” (Cronbachs alpha, 0.78 over all participants).

Among those with recent-onset psychosis, a higher VisDys sum score was correlated with lower scores for functional remission (P = .036) and social functioning (P = .014).

In CHR, higher VisDys sum scores were associated with lower scores for health-related functional remission (P = .024), lower physical and psychological QOL (P = .004 and P = .015, respectively), more severe depression on the BDI-II (P = .021), and more impaired visuospatial constructability (P = .027).

Among those with recent-onset depression and their healthy peers, “no relevant correlations were found between VisDys sum scores and any parameters representing functional remission, QOL, depressiveness, or visuospatial constructability,” the researchers wrote.

A total of 135 participants with recent-onset psychosis, 128 with CHR, and 134 with recent-onset depression also underwent resting-state fMRI.

ON functional connectivity predicted presence of VisDys in patients with recent-onset psychosis and those with CHR, with a balanced accuracy of 60.17% (P = .0001) and 67.38% (P = .029), respectively. In the combined recent-onset psychosis plus CHR sample, VisDys were predicted by FPN functional connectivity (balanced accuracy, 61.1%; P = .006).

“Findings from multivariate pattern analysis support a model of functional integrity within ON and FPN driving the VisDys phenomenon and being implicated in core disease mechanisms of early psychosis states,” the investigators noted.

“The main findings from this large sample study support the idea of VisDys being specific to the psychosis spectrum already at early stages,” while being less frequently reported in recent-onset depression, they wrote. VisDys also “appeared negligible” among those without psychiatric disorders.

Regular assessment needed

Steven Silverstein, PhD, professor of biopsychosocial medicine and professor of psychiatry, neuroscience, and ophthalmology, Center for Visual Science, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, called the findings “important” because “they will increase appreciation in the field of mental health for the frequency and disabling nature of visual symptoms and the need for regular assessment in routine clinical practice with people at risk for or with psychotic disorders.”

In addition, “the brain imaging findings are providing needed information that could lead to treatments that target the brain networks generating the visual symptoms,” such as neurofeedback or brain stimulation, said Dr. Silverstein, who was not involved with the research.

The study was funded by a grant for the PRONIA Consortium. Individual researchers received funding from NARSAD Young Investigator Award of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Koeln Fortune Program/Faculty of Medicine, the University of Cologne, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. Open Access funding was enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Ms. Schwarzer and Dr. Silverstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A multinational group of investigators found that VisDys were reported considerably more often by patients with recent-onset psychosis and CHR than by those with recent-onset depression or a group acting as healthy control participants.

In addition, vision problems of higher severity were associated with less functional remission both for patients at CHR and those with recent-onset psychosis. Among patients with CHR, VisDys was also linked to lower quality of life (QOL), higher depressiveness, and more severe impairment of visuospatial constructability.

The researchers used fMRI imaging to compare resting-state functional brain connectivity in participants with recent-onset psychosis, CHR, and recent-onset depression. They found that the occipital (ON) and frontoparietal (FPN) subnetworks were particularly implicated in VisDys.

“Subtle VisDys should be regarded as a frequent phenomenon across the psychosis spectrum, impinging negatively on patients’ current ability to function in several settings of their daily and social life, their QOL, and visuospatial abilities,” write investigators led by Johanna Schwarzer, Institute for Translational Psychiatry, University of Muenster (Germany).

“These large-sample study findings suggest that VisDys are clinically highly relevant not only in [recent-onset psychosis] but especially in CHR,” they stated.

The findings were published online in Neuropsychopharmacology.

Subtle, underrecognized

Unlike patients with nonpsychotic disorders, approximately 50%-60% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia report VisDys involving brightness, motion, form, color perception, or distorted perception of their own face, the researchers reported.

These “subtle” VisDys are “often underrecognized during clinical examination, despite their clinical relevance related to suicidal ideation, cognitive impairment, or poorer treatment response,” they wrote.

Most research into these vision problems in patients with schizophrenia has focused on patients in which the illness is in a stable, chronic state – although VisDys often appear years before the diagnosis of a psychotic disorder.

Moreover, there has been little research into the neurobiological underpinnings of VisDys, specifically in early states of psychosis and/or in comparison to other disorders, such as depression.

The Personalised Prognostic Indicators for Early Psychosis Management (PRONIA) Consortium studied the psychophysiological phenomenon of VisDys in a large sample of adolescents and young adults. The sample consisted of three diagnostic groups: those with recent-onset psychosis, those with CHR, and those with recent-onset depression.

VisDys in daily life were measured using the Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument–Adult Scale (SPI-A), which assesses basic symptoms that indicate increased risk for psychosis.

Visual information processing

Resting-state imaging data on intrinsic brain networks were also assessed in the PRONIA sample and were analyzed across 12,720 functional connectivities between 160 regions of interest across the whole brain.

In particular, the researchers were interested in the primary networks involved in visual information processing, especially the dorsal visual stream, with further focus on the ON and FPN intrinsic subnetworks.

The ON was chosen because it comprises “primary visual processing pathways,” while the FPN is “widely suggested to modulate attention related to visual information processing at higher cognitive levels.”

The investigators used a machine-learning multivariate pattern analysis approach that “enables the consideration of multiple interactions within brain systems.”

The current study involved 721 participants from the PRONIA database, including 147 participants with recent-onset psychosis (mean age, 28.45 years; 60.5% men), 143 with CHR (mean age, 26.97 years; about 50% men), 151 with recent-onset depression (mean age, 29.13 years; 47% men), and 280 in the healthy-controls group (mean age, 28.54 years; 39.4% men).

The researchers selected 14 items to assess from the SPI-A that represented different aspects of VisDys. Severity was defined by the maximum frequency within the past 3 months – from 1 (never) to 6 (daily).

The 14 items were as follows: oversensitivity to light and/or certain visual perception objects, photopsia, micropsia/macropsia, near and tele-vision, metamorphopsia, changes in color vision, altered perception of a patient’s own face, pseudomovements of optic stimuli, diplopia or oblique vision, disturbances of the estimation of distances or sizes, disturbances of the perception of straight lines/contours, maintenance of optic stimuli “visual echoes,” partial seeing (including tubular vision), and captivation of attention by details of the visual field.

Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory–II scale (BDI-II), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Functional Remission in General Schizophrenia, and several other scales that measure global and social functioning.

Other assessments included QOL and the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, which is a neuropsychological measurement of visuospatial constructability.

Specific to early-stage psychosis?

Results showed that VisDys were reported more frequently in both recent-onset psychosis and CHR groups compared with the recent-onset depression and healthy control groups (50.34% and 55.94% vs. 16.56% and 4.28%, respectively).

The investigators noted that VisDys sum scores “showed high internal consistency” (Cronbachs alpha, 0.78 over all participants).

Among those with recent-onset psychosis, a higher VisDys sum score was correlated with lower scores for functional remission (P = .036) and social functioning (P = .014).

In CHR, higher VisDys sum scores were associated with lower scores for health-related functional remission (P = .024), lower physical and psychological QOL (P = .004 and P = .015, respectively), more severe depression on the BDI-II (P = .021), and more impaired visuospatial constructability (P = .027).

Among those with recent-onset depression and their healthy peers, “no relevant correlations were found between VisDys sum scores and any parameters representing functional remission, QOL, depressiveness, or visuospatial constructability,” the researchers wrote.

A total of 135 participants with recent-onset psychosis, 128 with CHR, and 134 with recent-onset depression also underwent resting-state fMRI.

ON functional connectivity predicted presence of VisDys in patients with recent-onset psychosis and those with CHR, with a balanced accuracy of 60.17% (P = .0001) and 67.38% (P = .029), respectively. In the combined recent-onset psychosis plus CHR sample, VisDys were predicted by FPN functional connectivity (balanced accuracy, 61.1%; P = .006).

“Findings from multivariate pattern analysis support a model of functional integrity within ON and FPN driving the VisDys phenomenon and being implicated in core disease mechanisms of early psychosis states,” the investigators noted.

“The main findings from this large sample study support the idea of VisDys being specific to the psychosis spectrum already at early stages,” while being less frequently reported in recent-onset depression, they wrote. VisDys also “appeared negligible” among those without psychiatric disorders.

Regular assessment needed

Steven Silverstein, PhD, professor of biopsychosocial medicine and professor of psychiatry, neuroscience, and ophthalmology, Center for Visual Science, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, called the findings “important” because “they will increase appreciation in the field of mental health for the frequency and disabling nature of visual symptoms and the need for regular assessment in routine clinical practice with people at risk for or with psychotic disorders.”

In addition, “the brain imaging findings are providing needed information that could lead to treatments that target the brain networks generating the visual symptoms,” such as neurofeedback or brain stimulation, said Dr. Silverstein, who was not involved with the research.

The study was funded by a grant for the PRONIA Consortium. Individual researchers received funding from NARSAD Young Investigator Award of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Koeln Fortune Program/Faculty of Medicine, the University of Cologne, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. Open Access funding was enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Ms. Schwarzer and Dr. Silverstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY

Neuropsychiatric symptoms after stroke

Many patients experience neuropsychiatric symptoms following stroke. There is tremendous variation in the type, severity, and timeline of these symptoms, which have the potential to significantly impact patients’ quality of life. Some symptoms occur as a direct result of ischemic injury to brain structures regulating behavior, executive function, perception, or affect. Other symptoms occur indirectly due to the patient’s often-difficult experiences with the health care system, disrupted routines, or altered poststroke functional abilities. Psychiatric symptoms are not as easily recognized as classic stroke symptoms (such as hemiparesis) and are frequently overlooked, especially in the acute phase. However, these symptoms can negatively influence patients’ interpersonal relationships, rehabilitation, and employment.

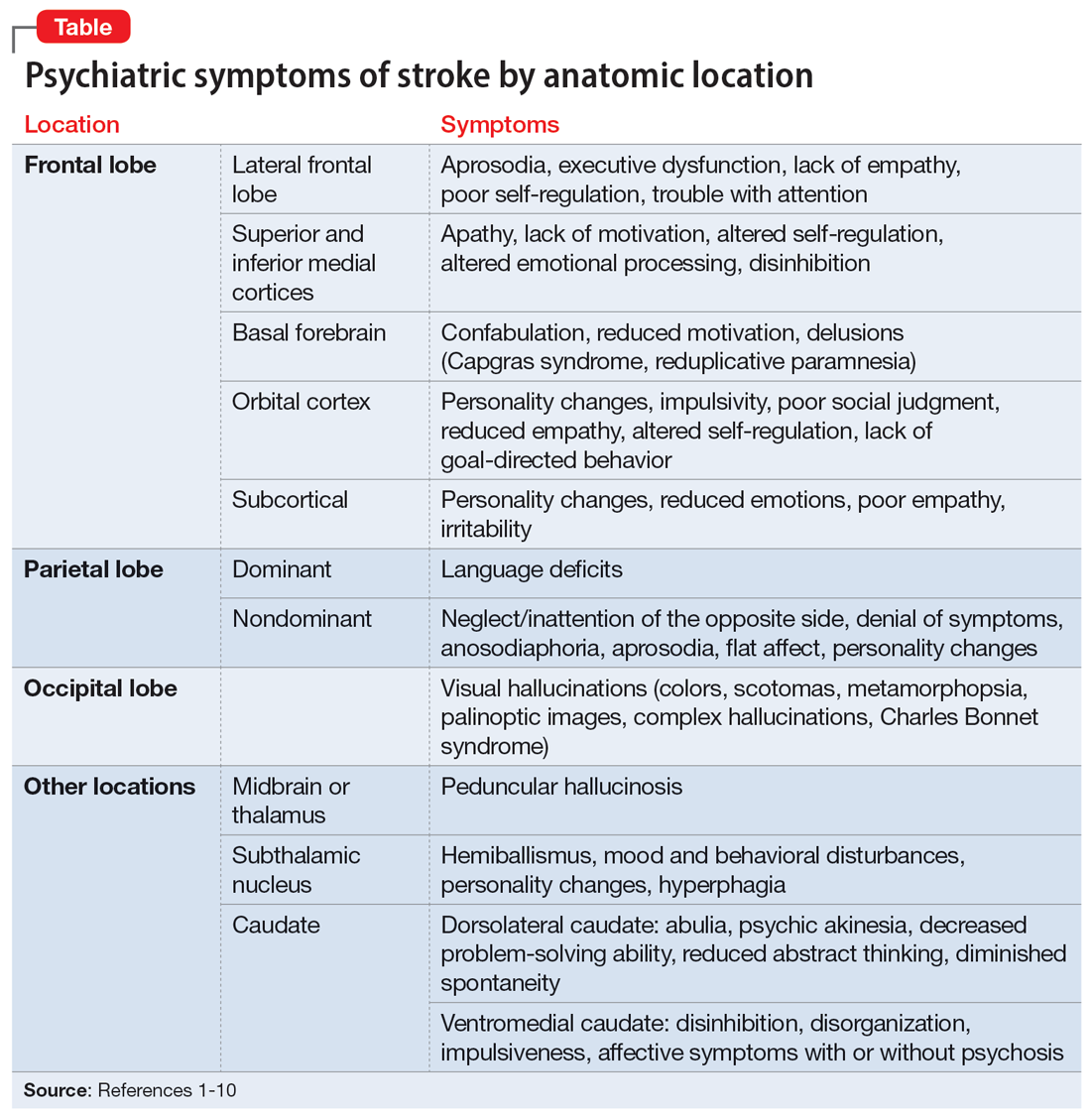

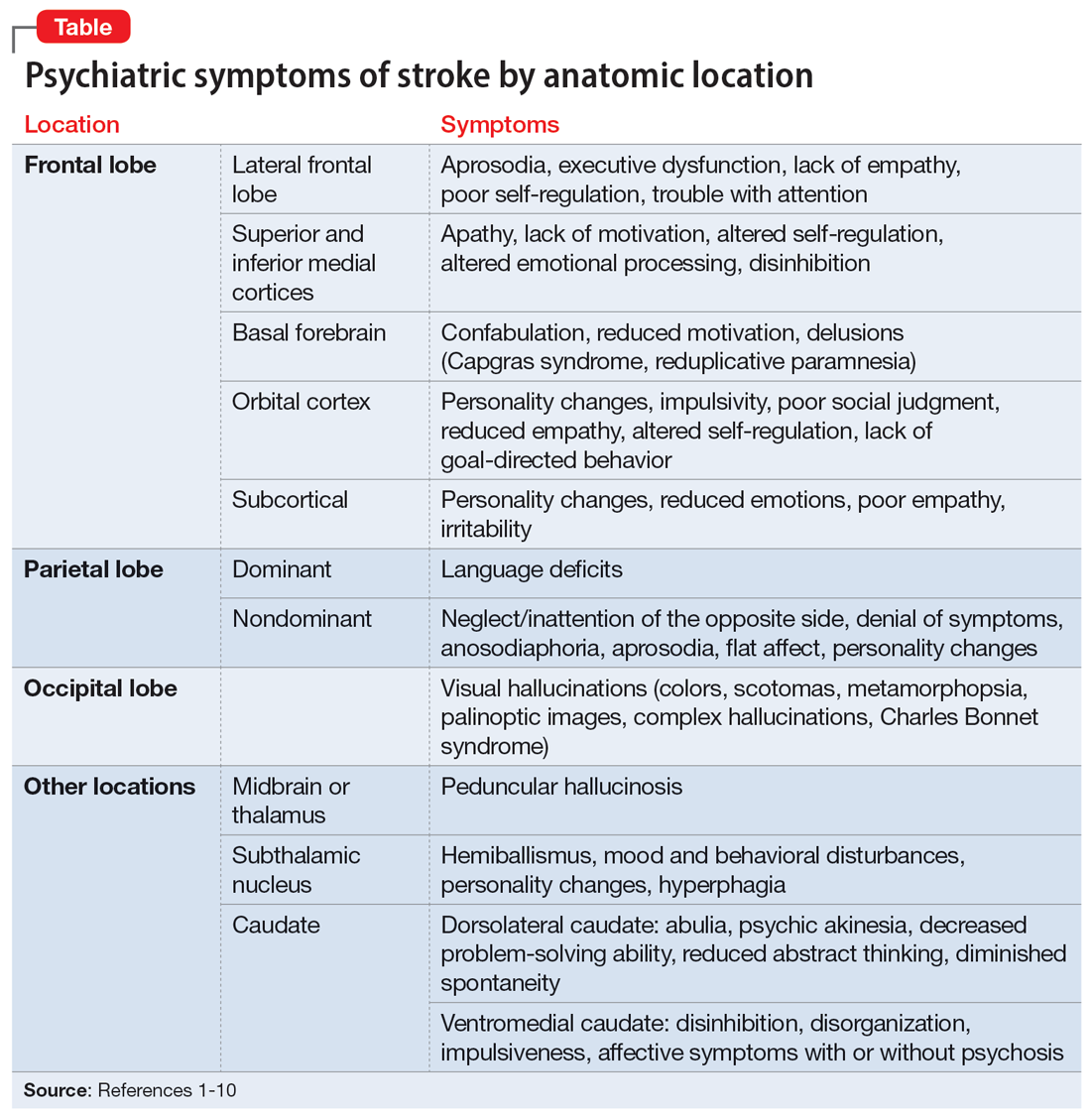

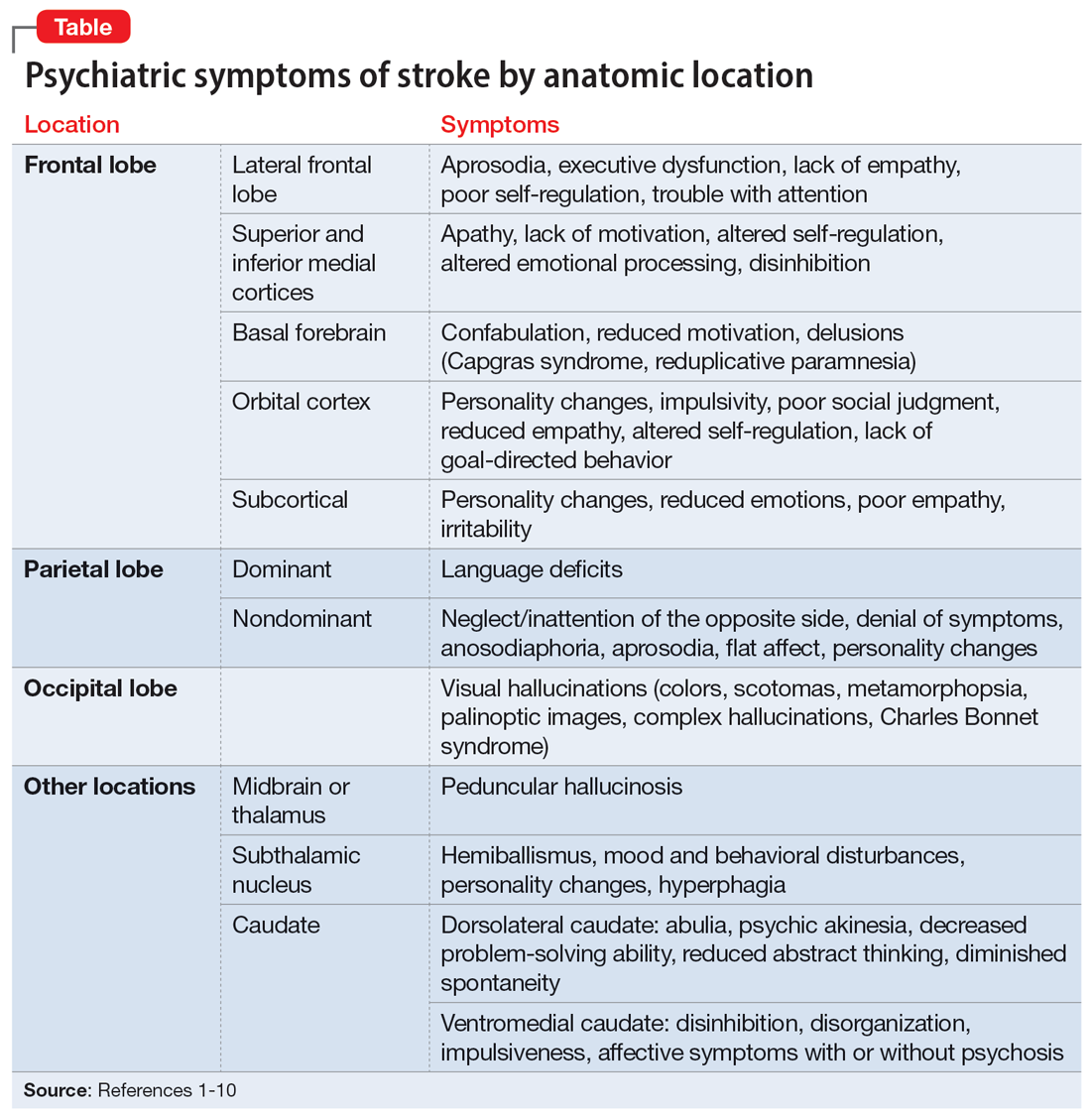

Patients and families may not realize certain symptoms are stroke-related and may not discuss them with their clinicians. It is important to ask about and recognize psychiatric symptoms in patients who have experienced a stroke so you can provide optimal education and treatment. In this article, we review the types of psychiatric symptoms associated with strokes in specific brain regions (Table1-10). We also describe symptoms that do not appear directly related to the anatomical structures affected by the infarct, including delirium, psychosis, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress.

Symptoms associated with stroke in specific regions

Frontal lobe strokes

The frontal lobes are the largest lobes in the brain, and damage to areas within these lobes can cause behavioral and personality changes. Lesions in the lateral frontal cortex can cause aprosodia (difficulty expressing or comprehending variations in tone of voice), which can lead to communication errors. Lateral frontal cortex injury can cause executive dysfunction and a lack of empathy1 as well as trouble with attention, planning, and self-regulation that may affect daily functioning. Strokes affecting the superior and inferior mesial cortices may result in apathy, lack of motivation, altered self-regulation, altered emotional processing, and disinhibition. Patients who experience a basal forebrain stroke may exhibit confabulation, reduced motivation, and delusions such as Capgras syndrome (the belief that a person or place has been replaced by an exact copy) and reduplicative paramnesia (the belief that a place has been either moved, duplicated, or exists in 2 places simultaneously). Strokes involving the orbital cortex can be associated with personality changes, impulsivity, poor social judgment, reduced empathy, altered self-regulation, lack of goal-directed behavior, and environmental dependency.

Some strokes may occur primarily in the subcortical white matter within the frontal lobes. Symptoms may be due to a single stroke with sudden onset, or due to repeated ischemic events that accumulate over time, as seen with microvascular disease. In the case of microvascular disease, the onset of symptoms may be insidious and the course progressive. Infarcts in the subcortical area can also cause personality changes (though typically more subtle when compared to orbitofrontal strokes), reduced emotions, poor empathy, and irritability.1 Patients may lack insight into some of or all these symptoms following a frontal lobe infarct, which makes it critical to gather collateral information from the patient’s friends or family.

Parietal lobe strokes

Symptomatology from parietal strokes depends on whether the stroke affects the dominant or nondominant hemisphere. Dominant parietal lesions cause language deficits, and psychiatric symptoms may be difficult to elucidate due to the patient’s inability to communicate.2 On the other hand, patients with nondominant parietal stroke may have neglect of, or inattention to, the opposite (typically left) side.3 This often manifests as a reluctance to use the affected limb or limbs, in some cases despite a lack of true weakness or motor dysfunction. In addition, patients may also have visual and/or tactile inattention towards the affected side, despite a lack of gross visual or sensory impairment.2 In rare cases, a patient’s stroke may be misdiagnosed as a functional disorder due to the perceived unwillingness to use a neurologically intact limb. In severe cases, patients may not recognize an affected extremity as their own. Patients are also frequently unaware of deficits affecting their nondominant side and may argue with those attempting to explain their deficit. Anosodiaphoria—an abnormal lack of concern regarding their deficits—may also be observed. Additionally, aprosodia, flat affect, and personality changes may result from strokes affecting the nondominant hemisphere, which can impact the patient’s relationships and social functioning.3

Occipital lobe strokes

While negative or loss-of-function symptomatology is one of the hallmarks of stroke, occipital lobe infarcts can pose an exception. Although vision loss is the most common symptom with occipital lobe strokes, some patients experience visual hallucinations that may occur acutely or subacutely. In the acute phase, patients may report hallucinations of varied description,4 including poorly formed areas of color, scotomas, metamorphopsia (visual distortion in which straight lines appear curved), more complex and formed hallucinations and/or palinoptic images (images or brief scenes that continue to be perceived after looking away). These hallucinations, often referred to as release phenomena or release hallucinations, are thought to result from disinhibition of the visual cortex, which then fires spontaneously.

Hallucinations are associated with either infarction or hemorrhage in the posterior cerebral artery territory. In some cases, the hallucinations may take on a formed, complex appearance, and Charles Bonnet syndrome (visual hallucinations in the setting of vision loss, with insight into the hallucinations) has been identified in a small portion of patients.5

Continue to: The duration of these...

The duration of these hallucinations varies. Some patients describe very short periods of the disturbance, lasting minutes to hours and corresponding with the onset of their stroke. Others experience prolonged hallucinations, which frequently evolve into formed, complex images, lasting from days to months.6 In the setting of cortical stroke, patients may be at risk for seizures, which could manifest as visual hallucinations. It is essential to ensure that epileptic causes of hallucinations have been ruled out, because seizures may require treatment and other precautions.

Other stroke locations

Strokes in other locations also can result in psychiatric or behavioral symptoms. Acute stroke in the subcortical midbrain or thalamus may result in peduncular hallucinosis, a syndrome of vivid visual hallucinations.7 The midbrain (most commonly the reticular formation) is usually affected; however, certain lesions of the thalamus may also cause peduncular hallucinosis. This phenomenon is theorized to be due to an increase in serotonin activity relative to acetylcholine and is often accompanied by drowsiness.

The subthalamic nucleus is most frequently associated with disordered movement such as hemiballismus, but also causes disturbances in mood and behavior, including hyperphagia and personality changes.8 Irritability, aggressiveness, disinhibition, anxiety, and obscene speech may also be seen with lesions of the subthalamic nucleus.

Finally, the caudate nucleus may cause alterations in executive functioning and behavior.9 A stroke in the dorsolateral caudate may cause abulia and psychic akinesia, decreased problem-solving ability, reduced abstract thinking, and/or diminished spontaneity, whereas an infarct in the ventromedial region of the nucleus may cause disinhibition, disorganization, impulsiveness, and, in severe cases, affective symptoms with psychosis.10 Strokes in any of these areas are at risk for being misdiagnosed because patients may not have a hemiparesis, and isolated positive or psychiatric symptoms may not be recognized as stroke.

Symptoms not related to stroke location

Delirium and psychosis

Following a stroke, a patient may exhibit neuropsychiatric symptoms that do not appear to relate directly to the anatomical structures affected by the infarct. In the acute phase, factors such as older age and medical complications (including infection, metabolic derangement, and lack of sleep due to frequent neurologic checks) create a high risk of delirium.11 Differentiating delirium from alterations in mental status due to seizure, cerebral edema, or other medical complications is essential, and delirium precautions should be exercised to the greatest extent possible. Other neuropsychiatric symptoms may manifest following hospitalization.

Continue to: Poststroke psychosis...

Poststroke psychosis often presents subacutely. Among these patients, the most common psychosis is delusion disorder, followed by schizophrenia-like psychosis and mood disorder with psychotic features.12 Some evidence suggests antipsychotics may be highly effective for many of these patients.12 Poststroke psychosis does appear to correlate somewhat with nondominant hemisphere lesions, including the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and/or caudate nucleus. Because high mortality and poor functional outcomes have been associated with poststroke psychosis, early intervention is essential.

Depression

Depression is a common problem following stroke, affecting approximately 35% of stroke patients.13 In addition to impairing quality of life, depression negatively impacts rehabilitation and increases caregiver burden. There is significant variability regarding risk factors that increases the likelihood of poststroke depression; however, psychiatric history, dysphagia, and poor social support consistently correlate with a higher risk.14,15 Characteristics of a patient’s stroke, such as lesion volume and the ability to perform activities of daily living, are also risk factors. Identifying depression among patients who recently had a stroke is sometimes difficult due to a plethora of confounding factors. Patients may not communicate well due to aphasia, while strokes in other locations may result in an altered affect. Depending on the stroke location, patients may also suffer anosognosia (a lack of awareness of their deficits), which may impair their ability to learn and use adaptive strategies and equipment. An additional confounder is the significant overlap between depressive symptoms and those seen in the setting of a major medical event or hospitalization (decreased appetite, fatigue, etc). The prevalence of depression peaks approximately 3 to 6 months after stroke, with symptoms lasting 9 to 12 months on average, although many patients experience symptoms significantly longer.14 Because symptoms can begin within hours to days following a stroke, it is essential that both hospital and outpatient clinicians assess for depression when indicated. Patients with poststroke depression should receive prompt treatment because appropriate treatment correlates with improved rehabilitation, and most patients respond well to antidepressants.16 Early treatment reduces mortality and improves compliance with secondary stroke prevention measures, including pharmacotherapy.17

Anxiety and posttraumatic stress

Anxiety and anxiety-related disorders are additional potential complications following stroke that significantly influence patient outcomes and well-being. The abrupt, unexpected onset of stroke is often frightening to patients and families. The potential for life-altering deficits as well as intense, often invasive, interactions with the health care system does little to assuage patients’ fear. Stroke patients must contend with a change in neurologic function while processing their difficult experiences, and may develop profound fear of a recurrent stroke. As many as 22% of patients have an anxiety disorder 3 months after they have a stroke.18 Phobic disorder is the most prevalent subtype, followed by generalized anxiety disorder. Younger age and previous anxiety or depression place patients at greater risk of developing poststroke anxiety. Patients suffering from poststroke anxiety have a reduced quality of life, are more dependent, and show restricted participation in rehabilitation, all of which culminate in poorer outcomes.

Many patients describe their experiences surrounding their stroke as traumatic, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is increasingly acknowledged as a potential complication for patients with recent stroke.19 PTSD profoundly impacts patient quality of life. Interestingly, most patients who develop poststroke PTSD do not have a history of other psychiatric illness, and it is difficult to predict who may develop PTSD. Relatively little is known regarding optimal treatment strategies for poststroke PTSD, or the efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapeutic strategies to treat it.

Goals: Improve recovery and quality of life

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common following a stroke and may manifest in a variety of ways. While some symptoms are a direct consequence of injury to a specific brain region, other symptoms may be a response to loss of independence, disability, experience with the medical system, or fear of recurrent stroke. The onset of psychiatric symptoms can be acute, beginning during hospitalization, or delayed. Understanding the association of psychiatric symptoms with the anatomical location of stroke may assist clinicians in identifying such symptoms. This knowledge informs conversations with patients and their caregivers, who may benefit from understanding that such symptoms are common after stroke. Furthermore, identifying psychiatric complications following stroke may affect rehabilitation. Additional investigation is necessary to find more effective treatment modalities and improve early intervention.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are frequently overlooked in patients with recent stroke. These symptoms include delirium, psychosis, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder, and can be the direct result of injury to neuroanatomical structures or a consequence of the patient’s experience. Prompt treatment can maximize stroke recovery and quality of life.

Related Resources

- Zhang S, Xu M, Liu ZJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric issues after stroke: clinical significance and therapeutic implications. World J Psychiatry. 2020;10(6):125-138. doi:10.5498/wjp. v10.i6.125

- Saha G, Chakraborty K, Pattojoshi A. Management of psychiatric disorders in patients with stroke and traumatic brain injury. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64(Suppl 2): S344-S354.

1. Eslinger PJ, Reichwein RK. Frontal lobe stroke syndromes. In: Caplan LR, van Gijn J, eds. Stroke Syndromes. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2012:232-241.

2. Critchley M, Russell WR, Zangwill OL. Discussion on parietal lobe syndromes. Proc R Soc Med. 1951;44(4):337-346.

3. Hier DB, Mondlock J, Caplan LR. Behavioral abnormalities after right hemisphere stroke. Neurology. 1983;33(3):337-344.

4. Brust JC, Behrens MM. “Release hallucinations” as the major symptom of posterior cerebral artery occlusion: a report of 2 cases. Ann Neurol. 1977;2(5):432-436.

5. Kumral E, Uluakay A, Donmez A. Complex visual hallucinations following stroke: epileptic origin or a deafferentiation phenomenon? Austin J Cerebrovasc Dis & Stroke. 2014;1(1):1005.

6. Lee JS, Ko KH, Oh JH, et al. Charles Bonnet syndrome after occipital infarction. J Neurosonol Neuroimag. 2018;10(2):154-157.

7. Young JB. Peduncular hallucinosis. In: Aminoff MJ, Daroff RB, eds. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014:848.

8. Etemadifar M, Abtahi SH, Abtahi SM, et al. Hemiballismus, hyperphagia, and behavioral changes following subthalamic infarct. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:768580. doi:10.1155/2012/768580

9. Kumral E, Evyapan D, Balkir K. Acute caudate vascular lesions. Stroke. 1999;30(1):100-108.

10. Wang PY. Neurobehavioral changes following caudate infarct: a case report with literature review. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1991;47(3):199-203.

11. Ahmed S, Leurent B, Sampson EL. Risk factors for incident delirium among older people in acute hospital medical units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014;43(3):326-33.

12. Stangeland H, Orgeta V, Bell V. Poststroke psychosis: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(8):879-885.

13. Lenzi GL, Altieri M, Maestrini I. Post-stroke depression. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2008;164(10):837-840.

14. Whyte EM, Mulsant BH. Post stroke depression: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and biological treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):253-264.

15. Pritchard KT, Hreha KP, Hong I. Dysphagia associated with risk of depressive symptoms among stroke survivors after discharge from a cluster of inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Swallowing Rehabil. 2020;3(1):33-44.

16. Wiart L, Petit H, Joseph PA, et al. Fluoxetine in early poststroke depression: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Stroke. 2000;31(8):1829-1832.

17. Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Arndt S, et al. Mortality and poststroke depression: a placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1823-1829.

18. Chun HY, Whiteley WN, Dennis MS, et al. Anxiety after stroke: the importance of subtyping. Stroke. 2018;49(3):556-564.

19. Garton AL, Sisti JA, Gupta VP, et al. Poststroke post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Stroke. 2017;48(2):507-512.

Many patients experience neuropsychiatric symptoms following stroke. There is tremendous variation in the type, severity, and timeline of these symptoms, which have the potential to significantly impact patients’ quality of life. Some symptoms occur as a direct result of ischemic injury to brain structures regulating behavior, executive function, perception, or affect. Other symptoms occur indirectly due to the patient’s often-difficult experiences with the health care system, disrupted routines, or altered poststroke functional abilities. Psychiatric symptoms are not as easily recognized as classic stroke symptoms (such as hemiparesis) and are frequently overlooked, especially in the acute phase. However, these symptoms can negatively influence patients’ interpersonal relationships, rehabilitation, and employment.

Patients and families may not realize certain symptoms are stroke-related and may not discuss them with their clinicians. It is important to ask about and recognize psychiatric symptoms in patients who have experienced a stroke so you can provide optimal education and treatment. In this article, we review the types of psychiatric symptoms associated with strokes in specific brain regions (Table1-10). We also describe symptoms that do not appear directly related to the anatomical structures affected by the infarct, including delirium, psychosis, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress.

Symptoms associated with stroke in specific regions

Frontal lobe strokes

The frontal lobes are the largest lobes in the brain, and damage to areas within these lobes can cause behavioral and personality changes. Lesions in the lateral frontal cortex can cause aprosodia (difficulty expressing or comprehending variations in tone of voice), which can lead to communication errors. Lateral frontal cortex injury can cause executive dysfunction and a lack of empathy1 as well as trouble with attention, planning, and self-regulation that may affect daily functioning. Strokes affecting the superior and inferior mesial cortices may result in apathy, lack of motivation, altered self-regulation, altered emotional processing, and disinhibition. Patients who experience a basal forebrain stroke may exhibit confabulation, reduced motivation, and delusions such as Capgras syndrome (the belief that a person or place has been replaced by an exact copy) and reduplicative paramnesia (the belief that a place has been either moved, duplicated, or exists in 2 places simultaneously). Strokes involving the orbital cortex can be associated with personality changes, impulsivity, poor social judgment, reduced empathy, altered self-regulation, lack of goal-directed behavior, and environmental dependency.

Some strokes may occur primarily in the subcortical white matter within the frontal lobes. Symptoms may be due to a single stroke with sudden onset, or due to repeated ischemic events that accumulate over time, as seen with microvascular disease. In the case of microvascular disease, the onset of symptoms may be insidious and the course progressive. Infarcts in the subcortical area can also cause personality changes (though typically more subtle when compared to orbitofrontal strokes), reduced emotions, poor empathy, and irritability.1 Patients may lack insight into some of or all these symptoms following a frontal lobe infarct, which makes it critical to gather collateral information from the patient’s friends or family.

Parietal lobe strokes

Symptomatology from parietal strokes depends on whether the stroke affects the dominant or nondominant hemisphere. Dominant parietal lesions cause language deficits, and psychiatric symptoms may be difficult to elucidate due to the patient’s inability to communicate.2 On the other hand, patients with nondominant parietal stroke may have neglect of, or inattention to, the opposite (typically left) side.3 This often manifests as a reluctance to use the affected limb or limbs, in some cases despite a lack of true weakness or motor dysfunction. In addition, patients may also have visual and/or tactile inattention towards the affected side, despite a lack of gross visual or sensory impairment.2 In rare cases, a patient’s stroke may be misdiagnosed as a functional disorder due to the perceived unwillingness to use a neurologically intact limb. In severe cases, patients may not recognize an affected extremity as their own. Patients are also frequently unaware of deficits affecting their nondominant side and may argue with those attempting to explain their deficit. Anosodiaphoria—an abnormal lack of concern regarding their deficits—may also be observed. Additionally, aprosodia, flat affect, and personality changes may result from strokes affecting the nondominant hemisphere, which can impact the patient’s relationships and social functioning.3

Occipital lobe strokes

While negative or loss-of-function symptomatology is one of the hallmarks of stroke, occipital lobe infarcts can pose an exception. Although vision loss is the most common symptom with occipital lobe strokes, some patients experience visual hallucinations that may occur acutely or subacutely. In the acute phase, patients may report hallucinations of varied description,4 including poorly formed areas of color, scotomas, metamorphopsia (visual distortion in which straight lines appear curved), more complex and formed hallucinations and/or palinoptic images (images or brief scenes that continue to be perceived after looking away). These hallucinations, often referred to as release phenomena or release hallucinations, are thought to result from disinhibition of the visual cortex, which then fires spontaneously.

Hallucinations are associated with either infarction or hemorrhage in the posterior cerebral artery territory. In some cases, the hallucinations may take on a formed, complex appearance, and Charles Bonnet syndrome (visual hallucinations in the setting of vision loss, with insight into the hallucinations) has been identified in a small portion of patients.5

Continue to: The duration of these...

The duration of these hallucinations varies. Some patients describe very short periods of the disturbance, lasting minutes to hours and corresponding with the onset of their stroke. Others experience prolonged hallucinations, which frequently evolve into formed, complex images, lasting from days to months.6 In the setting of cortical stroke, patients may be at risk for seizures, which could manifest as visual hallucinations. It is essential to ensure that epileptic causes of hallucinations have been ruled out, because seizures may require treatment and other precautions.

Other stroke locations

Strokes in other locations also can result in psychiatric or behavioral symptoms. Acute stroke in the subcortical midbrain or thalamus may result in peduncular hallucinosis, a syndrome of vivid visual hallucinations.7 The midbrain (most commonly the reticular formation) is usually affected; however, certain lesions of the thalamus may also cause peduncular hallucinosis. This phenomenon is theorized to be due to an increase in serotonin activity relative to acetylcholine and is often accompanied by drowsiness.

The subthalamic nucleus is most frequently associated with disordered movement such as hemiballismus, but also causes disturbances in mood and behavior, including hyperphagia and personality changes.8 Irritability, aggressiveness, disinhibition, anxiety, and obscene speech may also be seen with lesions of the subthalamic nucleus.

Finally, the caudate nucleus may cause alterations in executive functioning and behavior.9 A stroke in the dorsolateral caudate may cause abulia and psychic akinesia, decreased problem-solving ability, reduced abstract thinking, and/or diminished spontaneity, whereas an infarct in the ventromedial region of the nucleus may cause disinhibition, disorganization, impulsiveness, and, in severe cases, affective symptoms with psychosis.10 Strokes in any of these areas are at risk for being misdiagnosed because patients may not have a hemiparesis, and isolated positive or psychiatric symptoms may not be recognized as stroke.

Symptoms not related to stroke location

Delirium and psychosis

Following a stroke, a patient may exhibit neuropsychiatric symptoms that do not appear to relate directly to the anatomical structures affected by the infarct. In the acute phase, factors such as older age and medical complications (including infection, metabolic derangement, and lack of sleep due to frequent neurologic checks) create a high risk of delirium.11 Differentiating delirium from alterations in mental status due to seizure, cerebral edema, or other medical complications is essential, and delirium precautions should be exercised to the greatest extent possible. Other neuropsychiatric symptoms may manifest following hospitalization.

Continue to: Poststroke psychosis...

Poststroke psychosis often presents subacutely. Among these patients, the most common psychosis is delusion disorder, followed by schizophrenia-like psychosis and mood disorder with psychotic features.12 Some evidence suggests antipsychotics may be highly effective for many of these patients.12 Poststroke psychosis does appear to correlate somewhat with nondominant hemisphere lesions, including the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and/or caudate nucleus. Because high mortality and poor functional outcomes have been associated with poststroke psychosis, early intervention is essential.

Depression

Depression is a common problem following stroke, affecting approximately 35% of stroke patients.13 In addition to impairing quality of life, depression negatively impacts rehabilitation and increases caregiver burden. There is significant variability regarding risk factors that increases the likelihood of poststroke depression; however, psychiatric history, dysphagia, and poor social support consistently correlate with a higher risk.14,15 Characteristics of a patient’s stroke, such as lesion volume and the ability to perform activities of daily living, are also risk factors. Identifying depression among patients who recently had a stroke is sometimes difficult due to a plethora of confounding factors. Patients may not communicate well due to aphasia, while strokes in other locations may result in an altered affect. Depending on the stroke location, patients may also suffer anosognosia (a lack of awareness of their deficits), which may impair their ability to learn and use adaptive strategies and equipment. An additional confounder is the significant overlap between depressive symptoms and those seen in the setting of a major medical event or hospitalization (decreased appetite, fatigue, etc). The prevalence of depression peaks approximately 3 to 6 months after stroke, with symptoms lasting 9 to 12 months on average, although many patients experience symptoms significantly longer.14 Because symptoms can begin within hours to days following a stroke, it is essential that both hospital and outpatient clinicians assess for depression when indicated. Patients with poststroke depression should receive prompt treatment because appropriate treatment correlates with improved rehabilitation, and most patients respond well to antidepressants.16 Early treatment reduces mortality and improves compliance with secondary stroke prevention measures, including pharmacotherapy.17

Anxiety and posttraumatic stress

Anxiety and anxiety-related disorders are additional potential complications following stroke that significantly influence patient outcomes and well-being. The abrupt, unexpected onset of stroke is often frightening to patients and families. The potential for life-altering deficits as well as intense, often invasive, interactions with the health care system does little to assuage patients’ fear. Stroke patients must contend with a change in neurologic function while processing their difficult experiences, and may develop profound fear of a recurrent stroke. As many as 22% of patients have an anxiety disorder 3 months after they have a stroke.18 Phobic disorder is the most prevalent subtype, followed by generalized anxiety disorder. Younger age and previous anxiety or depression place patients at greater risk of developing poststroke anxiety. Patients suffering from poststroke anxiety have a reduced quality of life, are more dependent, and show restricted participation in rehabilitation, all of which culminate in poorer outcomes.

Many patients describe their experiences surrounding their stroke as traumatic, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is increasingly acknowledged as a potential complication for patients with recent stroke.19 PTSD profoundly impacts patient quality of life. Interestingly, most patients who develop poststroke PTSD do not have a history of other psychiatric illness, and it is difficult to predict who may develop PTSD. Relatively little is known regarding optimal treatment strategies for poststroke PTSD, or the efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapeutic strategies to treat it.

Goals: Improve recovery and quality of life

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common following a stroke and may manifest in a variety of ways. While some symptoms are a direct consequence of injury to a specific brain region, other symptoms may be a response to loss of independence, disability, experience with the medical system, or fear of recurrent stroke. The onset of psychiatric symptoms can be acute, beginning during hospitalization, or delayed. Understanding the association of psychiatric symptoms with the anatomical location of stroke may assist clinicians in identifying such symptoms. This knowledge informs conversations with patients and their caregivers, who may benefit from understanding that such symptoms are common after stroke. Furthermore, identifying psychiatric complications following stroke may affect rehabilitation. Additional investigation is necessary to find more effective treatment modalities and improve early intervention.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are frequently overlooked in patients with recent stroke. These symptoms include delirium, psychosis, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder, and can be the direct result of injury to neuroanatomical structures or a consequence of the patient’s experience. Prompt treatment can maximize stroke recovery and quality of life.

Related Resources

- Zhang S, Xu M, Liu ZJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric issues after stroke: clinical significance and therapeutic implications. World J Psychiatry. 2020;10(6):125-138. doi:10.5498/wjp. v10.i6.125

- Saha G, Chakraborty K, Pattojoshi A. Management of psychiatric disorders in patients with stroke and traumatic brain injury. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64(Suppl 2): S344-S354.

Many patients experience neuropsychiatric symptoms following stroke. There is tremendous variation in the type, severity, and timeline of these symptoms, which have the potential to significantly impact patients’ quality of life. Some symptoms occur as a direct result of ischemic injury to brain structures regulating behavior, executive function, perception, or affect. Other symptoms occur indirectly due to the patient’s often-difficult experiences with the health care system, disrupted routines, or altered poststroke functional abilities. Psychiatric symptoms are not as easily recognized as classic stroke symptoms (such as hemiparesis) and are frequently overlooked, especially in the acute phase. However, these symptoms can negatively influence patients’ interpersonal relationships, rehabilitation, and employment.

Patients and families may not realize certain symptoms are stroke-related and may not discuss them with their clinicians. It is important to ask about and recognize psychiatric symptoms in patients who have experienced a stroke so you can provide optimal education and treatment. In this article, we review the types of psychiatric symptoms associated with strokes in specific brain regions (Table1-10). We also describe symptoms that do not appear directly related to the anatomical structures affected by the infarct, including delirium, psychosis, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress.

Symptoms associated with stroke in specific regions

Frontal lobe strokes

The frontal lobes are the largest lobes in the brain, and damage to areas within these lobes can cause behavioral and personality changes. Lesions in the lateral frontal cortex can cause aprosodia (difficulty expressing or comprehending variations in tone of voice), which can lead to communication errors. Lateral frontal cortex injury can cause executive dysfunction and a lack of empathy1 as well as trouble with attention, planning, and self-regulation that may affect daily functioning. Strokes affecting the superior and inferior mesial cortices may result in apathy, lack of motivation, altered self-regulation, altered emotional processing, and disinhibition. Patients who experience a basal forebrain stroke may exhibit confabulation, reduced motivation, and delusions such as Capgras syndrome (the belief that a person or place has been replaced by an exact copy) and reduplicative paramnesia (the belief that a place has been either moved, duplicated, or exists in 2 places simultaneously). Strokes involving the orbital cortex can be associated with personality changes, impulsivity, poor social judgment, reduced empathy, altered self-regulation, lack of goal-directed behavior, and environmental dependency.

Some strokes may occur primarily in the subcortical white matter within the frontal lobes. Symptoms may be due to a single stroke with sudden onset, or due to repeated ischemic events that accumulate over time, as seen with microvascular disease. In the case of microvascular disease, the onset of symptoms may be insidious and the course progressive. Infarcts in the subcortical area can also cause personality changes (though typically more subtle when compared to orbitofrontal strokes), reduced emotions, poor empathy, and irritability.1 Patients may lack insight into some of or all these symptoms following a frontal lobe infarct, which makes it critical to gather collateral information from the patient’s friends or family.

Parietal lobe strokes

Symptomatology from parietal strokes depends on whether the stroke affects the dominant or nondominant hemisphere. Dominant parietal lesions cause language deficits, and psychiatric symptoms may be difficult to elucidate due to the patient’s inability to communicate.2 On the other hand, patients with nondominant parietal stroke may have neglect of, or inattention to, the opposite (typically left) side.3 This often manifests as a reluctance to use the affected limb or limbs, in some cases despite a lack of true weakness or motor dysfunction. In addition, patients may also have visual and/or tactile inattention towards the affected side, despite a lack of gross visual or sensory impairment.2 In rare cases, a patient’s stroke may be misdiagnosed as a functional disorder due to the perceived unwillingness to use a neurologically intact limb. In severe cases, patients may not recognize an affected extremity as their own. Patients are also frequently unaware of deficits affecting their nondominant side and may argue with those attempting to explain their deficit. Anosodiaphoria—an abnormal lack of concern regarding their deficits—may also be observed. Additionally, aprosodia, flat affect, and personality changes may result from strokes affecting the nondominant hemisphere, which can impact the patient’s relationships and social functioning.3

Occipital lobe strokes

While negative or loss-of-function symptomatology is one of the hallmarks of stroke, occipital lobe infarcts can pose an exception. Although vision loss is the most common symptom with occipital lobe strokes, some patients experience visual hallucinations that may occur acutely or subacutely. In the acute phase, patients may report hallucinations of varied description,4 including poorly formed areas of color, scotomas, metamorphopsia (visual distortion in which straight lines appear curved), more complex and formed hallucinations and/or palinoptic images (images or brief scenes that continue to be perceived after looking away). These hallucinations, often referred to as release phenomena or release hallucinations, are thought to result from disinhibition of the visual cortex, which then fires spontaneously.

Hallucinations are associated with either infarction or hemorrhage in the posterior cerebral artery territory. In some cases, the hallucinations may take on a formed, complex appearance, and Charles Bonnet syndrome (visual hallucinations in the setting of vision loss, with insight into the hallucinations) has been identified in a small portion of patients.5

Continue to: The duration of these...

The duration of these hallucinations varies. Some patients describe very short periods of the disturbance, lasting minutes to hours and corresponding with the onset of their stroke. Others experience prolonged hallucinations, which frequently evolve into formed, complex images, lasting from days to months.6 In the setting of cortical stroke, patients may be at risk for seizures, which could manifest as visual hallucinations. It is essential to ensure that epileptic causes of hallucinations have been ruled out, because seizures may require treatment and other precautions.

Other stroke locations

Strokes in other locations also can result in psychiatric or behavioral symptoms. Acute stroke in the subcortical midbrain or thalamus may result in peduncular hallucinosis, a syndrome of vivid visual hallucinations.7 The midbrain (most commonly the reticular formation) is usually affected; however, certain lesions of the thalamus may also cause peduncular hallucinosis. This phenomenon is theorized to be due to an increase in serotonin activity relative to acetylcholine and is often accompanied by drowsiness.

The subthalamic nucleus is most frequently associated with disordered movement such as hemiballismus, but also causes disturbances in mood and behavior, including hyperphagia and personality changes.8 Irritability, aggressiveness, disinhibition, anxiety, and obscene speech may also be seen with lesions of the subthalamic nucleus.

Finally, the caudate nucleus may cause alterations in executive functioning and behavior.9 A stroke in the dorsolateral caudate may cause abulia and psychic akinesia, decreased problem-solving ability, reduced abstract thinking, and/or diminished spontaneity, whereas an infarct in the ventromedial region of the nucleus may cause disinhibition, disorganization, impulsiveness, and, in severe cases, affective symptoms with psychosis.10 Strokes in any of these areas are at risk for being misdiagnosed because patients may not have a hemiparesis, and isolated positive or psychiatric symptoms may not be recognized as stroke.

Symptoms not related to stroke location

Delirium and psychosis