User login

4 cases involving intraoperative injuries to adjacent organs

During surgery, the ObGyn discovered that pelvic adhesions had distorted the patient’s anatomy; he converted to laparotomy, which left a larger scar. Two days after surgery, the patient was found to have a bowel injury and underwent additional surgery that included placement of surgical mesh, leaving an enlarged scar.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in injuring the patient’s bowel during hysterectomy and not detecting the injury intraoperatively. Her scars were larger because of the additional repair operation.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Bowel injury is a known complication of the procedure. Many bowel injuries are not detected intraoperatively. The ObGyn made every effort to prevent and check for injury during the procedure.

VERDICT: An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Uterus and bowel injured during D&C: $1.5M verdict

A 56-year-old woman underwent hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage (D&C). During the procedure, the gynecologist recognized that he had perforated the uterus and injured the bowel and called in a general surgeon to resect 5 cm of the bowel and repair the uterus.

PATIENT'S CLAIM:The patient has a large abdominal scar and a chronically distended abdomen. She experienced a year of daily pain and suffering. The D&C was unnecessary and improperly performed: the standard of care is for the gynecologist to operate in a gentle manner; that did not occur.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE:The D&C was medically necessary. The gynecologist exercised the proper standard of care.

VERDICT:A $1.5 million New Jersey verdict was returned. The jury found the D&C necessary, but determined that the gynecologist deviated from the accepted standard of care in his performance of the procedure.

Bowel perforation during myomectomy: $200,000 verdictA 44-year-old woman underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy. During the procedure the ObGyn realized that he had perforated the uterus. He switched to a laparoscopic procedure, found a 3-cm uterine tear, and converted to laparotomy to repair the injury. The postsurgical pathology report revealed multiple colon fragments.

Three days after surgery, the patient became ill and was found to have a bowel injury. She underwent bowel resection with colostomy and, a year later, colostomy reversal. She sustained abdominal scarring.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in performing the myomectomy. He should have identified the bowel injury intraoperatively. When the pathology report indicated multiple colon fragments, he should have investigated rather than wait for the patient to develop symptoms.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Uterine and colon injuries are known complications of the procedure and can occur within the standard of care. The ObGyn intraoperatively inspected the organs adjacent to the uterus but there was no evident injury. The patient’s postsurgical treatment was proper.

VERDICT: A $200,000 Illinois verdict was returned.

Injured ureter allegedly not treatedA 42-year-old woman underwent hysterectomy on December 6. Postoperatively, she reported increasing dysuria with pain and fever. On December 13, a computed tomography (CT) scan suggested a partial ureter obstruction. Despite test results, the gynecologist elected to continue to monitor the patient. The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen and, on December 27, she underwent a second CT scan that identified an obstructed ureter. The gynecologist referred the patient to a urologist, who determined that the patient had sustained a significant ureter injury that required placement of a nephrostomy tube.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The gynecologist failed to identify the injury during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in not consulting a urologist after results of the first CT scan.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Uterine injury is a known complication of the procedure. The gynecologist inspected adjacent organs during surgery but did not find an injury. Postoperative treatment was appropriate.

VERDICT: The case was presented before a medical review board that concluded that there was no error after the first injury, there was no duty to trace the ureter, and a urology consult was not required after the first CT scan. A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

During surgery, the ObGyn discovered that pelvic adhesions had distorted the patient’s anatomy; he converted to laparotomy, which left a larger scar. Two days after surgery, the patient was found to have a bowel injury and underwent additional surgery that included placement of surgical mesh, leaving an enlarged scar.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in injuring the patient’s bowel during hysterectomy and not detecting the injury intraoperatively. Her scars were larger because of the additional repair operation.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Bowel injury is a known complication of the procedure. Many bowel injuries are not detected intraoperatively. The ObGyn made every effort to prevent and check for injury during the procedure.

VERDICT: An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Uterus and bowel injured during D&C: $1.5M verdict

A 56-year-old woman underwent hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage (D&C). During the procedure, the gynecologist recognized that he had perforated the uterus and injured the bowel and called in a general surgeon to resect 5 cm of the bowel and repair the uterus.

PATIENT'S CLAIM:The patient has a large abdominal scar and a chronically distended abdomen. She experienced a year of daily pain and suffering. The D&C was unnecessary and improperly performed: the standard of care is for the gynecologist to operate in a gentle manner; that did not occur.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE:The D&C was medically necessary. The gynecologist exercised the proper standard of care.

VERDICT:A $1.5 million New Jersey verdict was returned. The jury found the D&C necessary, but determined that the gynecologist deviated from the accepted standard of care in his performance of the procedure.

Bowel perforation during myomectomy: $200,000 verdictA 44-year-old woman underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy. During the procedure the ObGyn realized that he had perforated the uterus. He switched to a laparoscopic procedure, found a 3-cm uterine tear, and converted to laparotomy to repair the injury. The postsurgical pathology report revealed multiple colon fragments.

Three days after surgery, the patient became ill and was found to have a bowel injury. She underwent bowel resection with colostomy and, a year later, colostomy reversal. She sustained abdominal scarring.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in performing the myomectomy. He should have identified the bowel injury intraoperatively. When the pathology report indicated multiple colon fragments, he should have investigated rather than wait for the patient to develop symptoms.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Uterine and colon injuries are known complications of the procedure and can occur within the standard of care. The ObGyn intraoperatively inspected the organs adjacent to the uterus but there was no evident injury. The patient’s postsurgical treatment was proper.

VERDICT: A $200,000 Illinois verdict was returned.

Injured ureter allegedly not treatedA 42-year-old woman underwent hysterectomy on December 6. Postoperatively, she reported increasing dysuria with pain and fever. On December 13, a computed tomography (CT) scan suggested a partial ureter obstruction. Despite test results, the gynecologist elected to continue to monitor the patient. The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen and, on December 27, she underwent a second CT scan that identified an obstructed ureter. The gynecologist referred the patient to a urologist, who determined that the patient had sustained a significant ureter injury that required placement of a nephrostomy tube.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The gynecologist failed to identify the injury during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in not consulting a urologist after results of the first CT scan.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Uterine injury is a known complication of the procedure. The gynecologist inspected adjacent organs during surgery but did not find an injury. Postoperative treatment was appropriate.

VERDICT: The case was presented before a medical review board that concluded that there was no error after the first injury, there was no duty to trace the ureter, and a urology consult was not required after the first CT scan. A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

During surgery, the ObGyn discovered that pelvic adhesions had distorted the patient’s anatomy; he converted to laparotomy, which left a larger scar. Two days after surgery, the patient was found to have a bowel injury and underwent additional surgery that included placement of surgical mesh, leaving an enlarged scar.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in injuring the patient’s bowel during hysterectomy and not detecting the injury intraoperatively. Her scars were larger because of the additional repair operation.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Bowel injury is a known complication of the procedure. Many bowel injuries are not detected intraoperatively. The ObGyn made every effort to prevent and check for injury during the procedure.

VERDICT: An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Uterus and bowel injured during D&C: $1.5M verdict

A 56-year-old woman underwent hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage (D&C). During the procedure, the gynecologist recognized that he had perforated the uterus and injured the bowel and called in a general surgeon to resect 5 cm of the bowel and repair the uterus.

PATIENT'S CLAIM:The patient has a large abdominal scar and a chronically distended abdomen. She experienced a year of daily pain and suffering. The D&C was unnecessary and improperly performed: the standard of care is for the gynecologist to operate in a gentle manner; that did not occur.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE:The D&C was medically necessary. The gynecologist exercised the proper standard of care.

VERDICT:A $1.5 million New Jersey verdict was returned. The jury found the D&C necessary, but determined that the gynecologist deviated from the accepted standard of care in his performance of the procedure.

Bowel perforation during myomectomy: $200,000 verdictA 44-year-old woman underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy. During the procedure the ObGyn realized that he had perforated the uterus. He switched to a laparoscopic procedure, found a 3-cm uterine tear, and converted to laparotomy to repair the injury. The postsurgical pathology report revealed multiple colon fragments.

Three days after surgery, the patient became ill and was found to have a bowel injury. She underwent bowel resection with colostomy and, a year later, colostomy reversal. She sustained abdominal scarring.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The ObGyn was negligent in performing the myomectomy. He should have identified the bowel injury intraoperatively. When the pathology report indicated multiple colon fragments, he should have investigated rather than wait for the patient to develop symptoms.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Uterine and colon injuries are known complications of the procedure and can occur within the standard of care. The ObGyn intraoperatively inspected the organs adjacent to the uterus but there was no evident injury. The patient’s postsurgical treatment was proper.

VERDICT: A $200,000 Illinois verdict was returned.

Injured ureter allegedly not treatedA 42-year-old woman underwent hysterectomy on December 6. Postoperatively, she reported increasing dysuria with pain and fever. On December 13, a computed tomography (CT) scan suggested a partial ureter obstruction. Despite test results, the gynecologist elected to continue to monitor the patient. The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen and, on December 27, she underwent a second CT scan that identified an obstructed ureter. The gynecologist referred the patient to a urologist, who determined that the patient had sustained a significant ureter injury that required placement of a nephrostomy tube.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The gynecologist failed to identify the injury during surgery. The gynecologist was negligent in not consulting a urologist after results of the first CT scan.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: Uterine injury is a known complication of the procedure. The gynecologist inspected adjacent organs during surgery but did not find an injury. Postoperative treatment was appropriate.

VERDICT: The case was presented before a medical review board that concluded that there was no error after the first injury, there was no duty to trace the ureter, and a urology consult was not required after the first CT scan. A Louisiana defense verdict was returned.

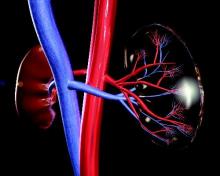

Syndecan-1 may predict kidney injury after ped heart surgery

Acute kidney injury is a common complication after pediatric cardiac surgery, but measuring for a specific genetic protein immediately after cardiac surgery may improve cardiac surgeons’ ability to predict patients at higher risk of AKI, according to researchers from Brazil. The study results are in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152-178-86).

“Plasma syndecan-1 levels measured early in the postoperative period were independently associated with severe acute kidney injury,” wrote Candice Torres de Melo Bezerra Cavalcante, MD, of Heart Hospital of Messejana and Federal University of Ceará.

Their prospective cohort study involved 289 pediatric patients who had cardiac surgery at their institution between September 2013 and December 2014.

Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues acknowledged that the traditional biomarker for renal function, serum creatinine, only increases appreciably after the glomerular filtration rate declines 50%, impairing physicians’ ability to detect AKI early enough to treat it. “This delay can explain, in part the, negative results in AKI therapeutic clinical trials,” they wrote.

They evaluated two different endothelial biomarkers in addition to syndecan-1 with regard to their capacity for predicting severe AKI: plasma ICAM-1, a marker of endothelial cell activation; and E-selectin, an endothelial cell adhesion molecule. Syndecan-1 works as a biomarker of injury to the glycocalyx protein that surrounds endothelial cell membranes that acts as a permeability barrier and prevents the cells from adhering to blood. They found that median syndecan-1 levels soon after surgery were higher in patients with severe AKI, 103.6 vs. 42.3 ng/mL.

“Although syndecan-1 is not a renal-specific biomarker, there has been recent increasing evidence that endothelial injury has an important role in AKI pathophysiology,” the researchers noted.

Study results showed the higher the level of syndecan-1, the greater the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for severe AKI. Levels of less than 17 ng/mL were considered normal; 17.1-46.7 ng/mL carried an adjusted OR of 1.42; 47.4-93.1 ng/mL had an adjusted OR of 2.05; and levels 96.3 or greater had an OR of 8.87.

“Maintenance of endothelial glycocalyx integrity can be a therapeutic target to reduce AKI in this setting,” the researchers wrote.

The authors acknowledged that the study was done at a single center that had dialysis and death rates three and five times higher, respectively, than those of developed countries; and it measured syndecan-1 at only one time point almost immediately after the operation.

“Adding postoperative syndecan-1, even when using a clinical model that already incorporates variables from renal angina index, results in significant improvement in the capacity to predict severe AKI,” Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues concluded.

They had no financial relationships to disclose.

Results of AKI in heart surgery patients have been “sobering,” with up to 56% of these patients being diagnosed with AKI, but research such as that by Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues represents a new approach to improving outcomes by combining clinical risk factors with specific biomarkers to identify patients at risk, Petros V. Anagnostopoulos, MD, of American Family Children’s Hospital, University of Wisconsin, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152[1]:187-8).

Dr. Anagnostopoulos acknowledged problems with traditional markers for renal function. “An ideal biomarker should be sensitive, easy to measure, reproducible, and inexpensive,” he said. “Finally, when combined with clinical prediction models, it should potentiate the discrimination of these models.”

Syndecan-1 answers that call, he said. “It peaks early and is cheap, fast, and easy to measure with readily available methods, which makes it an ideal early biomarker of AKI,” Dr. Anagnostopoulos said. Even so, he pointed out potential shortcomings of syndecan-1: It is not renal specific and it does not increase before the operation.

But he applauded Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues for pursuing research to combine clinical risk factors with specific biomarkers. “It is very likely that this type of clinical research will become prevalent in the near future and will hopefully produce results that will allow better individual patient-specific risk stratification,” Dr. Anagnostopoulos said.

He had no financial relationships to disclose.

Results of AKI in heart surgery patients have been “sobering,” with up to 56% of these patients being diagnosed with AKI, but research such as that by Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues represents a new approach to improving outcomes by combining clinical risk factors with specific biomarkers to identify patients at risk, Petros V. Anagnostopoulos, MD, of American Family Children’s Hospital, University of Wisconsin, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152[1]:187-8).

Dr. Anagnostopoulos acknowledged problems with traditional markers for renal function. “An ideal biomarker should be sensitive, easy to measure, reproducible, and inexpensive,” he said. “Finally, when combined with clinical prediction models, it should potentiate the discrimination of these models.”

Syndecan-1 answers that call, he said. “It peaks early and is cheap, fast, and easy to measure with readily available methods, which makes it an ideal early biomarker of AKI,” Dr. Anagnostopoulos said. Even so, he pointed out potential shortcomings of syndecan-1: It is not renal specific and it does not increase before the operation.

But he applauded Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues for pursuing research to combine clinical risk factors with specific biomarkers. “It is very likely that this type of clinical research will become prevalent in the near future and will hopefully produce results that will allow better individual patient-specific risk stratification,” Dr. Anagnostopoulos said.

He had no financial relationships to disclose.

Results of AKI in heart surgery patients have been “sobering,” with up to 56% of these patients being diagnosed with AKI, but research such as that by Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues represents a new approach to improving outcomes by combining clinical risk factors with specific biomarkers to identify patients at risk, Petros V. Anagnostopoulos, MD, of American Family Children’s Hospital, University of Wisconsin, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152[1]:187-8).

Dr. Anagnostopoulos acknowledged problems with traditional markers for renal function. “An ideal biomarker should be sensitive, easy to measure, reproducible, and inexpensive,” he said. “Finally, when combined with clinical prediction models, it should potentiate the discrimination of these models.”

Syndecan-1 answers that call, he said. “It peaks early and is cheap, fast, and easy to measure with readily available methods, which makes it an ideal early biomarker of AKI,” Dr. Anagnostopoulos said. Even so, he pointed out potential shortcomings of syndecan-1: It is not renal specific and it does not increase before the operation.

But he applauded Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues for pursuing research to combine clinical risk factors with specific biomarkers. “It is very likely that this type of clinical research will become prevalent in the near future and will hopefully produce results that will allow better individual patient-specific risk stratification,” Dr. Anagnostopoulos said.

He had no financial relationships to disclose.

Acute kidney injury is a common complication after pediatric cardiac surgery, but measuring for a specific genetic protein immediately after cardiac surgery may improve cardiac surgeons’ ability to predict patients at higher risk of AKI, according to researchers from Brazil. The study results are in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152-178-86).

“Plasma syndecan-1 levels measured early in the postoperative period were independently associated with severe acute kidney injury,” wrote Candice Torres de Melo Bezerra Cavalcante, MD, of Heart Hospital of Messejana and Federal University of Ceará.

Their prospective cohort study involved 289 pediatric patients who had cardiac surgery at their institution between September 2013 and December 2014.

Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues acknowledged that the traditional biomarker for renal function, serum creatinine, only increases appreciably after the glomerular filtration rate declines 50%, impairing physicians’ ability to detect AKI early enough to treat it. “This delay can explain, in part the, negative results in AKI therapeutic clinical trials,” they wrote.

They evaluated two different endothelial biomarkers in addition to syndecan-1 with regard to their capacity for predicting severe AKI: plasma ICAM-1, a marker of endothelial cell activation; and E-selectin, an endothelial cell adhesion molecule. Syndecan-1 works as a biomarker of injury to the glycocalyx protein that surrounds endothelial cell membranes that acts as a permeability barrier and prevents the cells from adhering to blood. They found that median syndecan-1 levels soon after surgery were higher in patients with severe AKI, 103.6 vs. 42.3 ng/mL.

“Although syndecan-1 is not a renal-specific biomarker, there has been recent increasing evidence that endothelial injury has an important role in AKI pathophysiology,” the researchers noted.

Study results showed the higher the level of syndecan-1, the greater the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for severe AKI. Levels of less than 17 ng/mL were considered normal; 17.1-46.7 ng/mL carried an adjusted OR of 1.42; 47.4-93.1 ng/mL had an adjusted OR of 2.05; and levels 96.3 or greater had an OR of 8.87.

“Maintenance of endothelial glycocalyx integrity can be a therapeutic target to reduce AKI in this setting,” the researchers wrote.

The authors acknowledged that the study was done at a single center that had dialysis and death rates three and five times higher, respectively, than those of developed countries; and it measured syndecan-1 at only one time point almost immediately after the operation.

“Adding postoperative syndecan-1, even when using a clinical model that already incorporates variables from renal angina index, results in significant improvement in the capacity to predict severe AKI,” Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues concluded.

They had no financial relationships to disclose.

Acute kidney injury is a common complication after pediatric cardiac surgery, but measuring for a specific genetic protein immediately after cardiac surgery may improve cardiac surgeons’ ability to predict patients at higher risk of AKI, according to researchers from Brazil. The study results are in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152-178-86).

“Plasma syndecan-1 levels measured early in the postoperative period were independently associated with severe acute kidney injury,” wrote Candice Torres de Melo Bezerra Cavalcante, MD, of Heart Hospital of Messejana and Federal University of Ceará.

Their prospective cohort study involved 289 pediatric patients who had cardiac surgery at their institution between September 2013 and December 2014.

Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues acknowledged that the traditional biomarker for renal function, serum creatinine, only increases appreciably after the glomerular filtration rate declines 50%, impairing physicians’ ability to detect AKI early enough to treat it. “This delay can explain, in part the, negative results in AKI therapeutic clinical trials,” they wrote.

They evaluated two different endothelial biomarkers in addition to syndecan-1 with regard to their capacity for predicting severe AKI: plasma ICAM-1, a marker of endothelial cell activation; and E-selectin, an endothelial cell adhesion molecule. Syndecan-1 works as a biomarker of injury to the glycocalyx protein that surrounds endothelial cell membranes that acts as a permeability barrier and prevents the cells from adhering to blood. They found that median syndecan-1 levels soon after surgery were higher in patients with severe AKI, 103.6 vs. 42.3 ng/mL.

“Although syndecan-1 is not a renal-specific biomarker, there has been recent increasing evidence that endothelial injury has an important role in AKI pathophysiology,” the researchers noted.

Study results showed the higher the level of syndecan-1, the greater the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for severe AKI. Levels of less than 17 ng/mL were considered normal; 17.1-46.7 ng/mL carried an adjusted OR of 1.42; 47.4-93.1 ng/mL had an adjusted OR of 2.05; and levels 96.3 or greater had an OR of 8.87.

“Maintenance of endothelial glycocalyx integrity can be a therapeutic target to reduce AKI in this setting,” the researchers wrote.

The authors acknowledged that the study was done at a single center that had dialysis and death rates three and five times higher, respectively, than those of developed countries; and it measured syndecan-1 at only one time point almost immediately after the operation.

“Adding postoperative syndecan-1, even when using a clinical model that already incorporates variables from renal angina index, results in significant improvement in the capacity to predict severe AKI,” Dr. Cavalcante and colleagues concluded.

They had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: The biomarker syndecan-1 may aid in determining acute kidney injury risk for children having cardiac surgery.

Major finding: Children with elevated levels of syndecan-1 had a two- to ninefold greater risk of acute kidney injury.

Data source: Single-institution, prospective cohort study of 289 pediatric patients who had cardiac surgery from September 2013 to December 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Cavalcante and coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Preventing and managing vaginal cuff dehiscence

Vaginal cuff dehiscence, or separation of the vaginal incision, is a rare postoperative complication unique to hysterectomy. Morbidity related to evisceration of abdominal contents can be profound and prompt intervention is required.

A 10-year observational study of 11,000 patients described a 0.24% cumulative incidence after all modes of hysterectomy.1 Though data are varied, the mode of hysterectomy does have an impact on the risk of dehiscence.

Laparoscopic (0.64%-1.35%) and robotic (0.46%-1.5%) hysterectomy have a higher incidence than abdominal (0.15%-0.26%) and vaginal (0.08%-0.25%) approaches.2 The use of monopolar cautery for colpotomy and different closure techniques may account for these differences.

Cuff cellulitis, early sexual intercourse, cigarette smoking, poor nutrition, obesity, menopausal status, and corticosteroid use are all proposed risk factors that promote infection, pressure at the vaginal cuff, and poor wound healing. Although some are modifiable, the rarity of this complication has made establishing causality and promoting prevention challenging.

Prevention

• Preoperatively. Treating bacterial vaginosis, Trichomonas vaginalis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia can decrease the risk of cuff cellulitis and dehiscence.3

• Intraoperatively. Surgeons should ensure adequate vaginal margins (greater than 1 cm) with full-thickness cuff closures while avoiding excessive electrocautery.4 Retrospective data show that transvaginal cuff closure is associated with a decreased risk of dehiscence.5 However, given the lack of randomized data and the difficulty controlling for surgeon experience, gynecologists should use the approach that they are most comfortable with. Though the various laparoscopic cuff closure techniques have limited evidence regarding superiority, some experts propose using two-layer cuff closure and barbed sutures.6-8 Several retrospective studies have found an equivalent or a decreased incidence of cuff dehiscence with barbed sutures, compared with other methods (e.g., 0-Vicryl, Endo Stitch).9,10

• Postoperatively. Women should avoid intercourse and lifting more than 15 pounds for at least 6-8 weeks as the vaginal cuff gains tensile strength. Vaginal estrogen can promote healing in postmenopausal patients.11

Management

Patients with vaginal cuff dehiscence commonly present within the first several weeks to months after surgery with pelvic pain (60%-100%), vaginal bleeding (30%-60%), vaginal discharge (30%), or vaginal pressure/mass (30%).1,7 Posthysterectomy patients with these complaints warrant an urgent evaluation. The diagnosis is made during a pelvic exam.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are necessary because all vaginal cuff separations or dehiscences expose the peritoneal cavity to vaginal flora. Nonsurgical management is reasonable for small separations – less than 25% of the cuff – if there is no evidence of evisceration.

However, surgically closing all recognized cuff dehiscences is reasonable, given the potential for further separation. A vaginal approach is preferred when possible. Women with vaginal cuff dehiscence, stable vital signs, and no evidence of bowel evisceration can be repaired vaginally without an abdominal survey.

In contrast, women with bowel evisceration have a surgical emergency because of the risk of peritonitis and bowel injury. If the eviscerated bowel is not reducible, it should be irrigated and wrapped in a warm moist towel or gauze in preparation for inspection and reduction in the operating room. If the bowel is reducible, the patient can be placed in Trendelenburg’s position. Her vagina should be packed to reduce the risk of re-evisceration as she moves toward operative cuff repair.

If the physician is concerned about bowel injury, inspection via laparoscopy or laparotomy would be reasonable. However, when bowel injury is not suspected, a vaginal technique for dehiscence repair has been described by Matthews et al.:12

1. Expose the cuff with a weighted speculum and Breisky-Navratil retractors.

2. Sharply debride the cuff edges back to viable tissue.

3. Dissect adherent bowel or omentum to allow for full-thickness closure.

4. Place full-thickness, interrupted delayed absorbable sutures to reapproximate the cuff edges.

Cuff dehiscence is a rare but potentially morbid complication of hysterectomy. Prevention, recognition, and appropriate management can avoid life-threatening sequelae.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Oct;118(4):794-801.

2. JSLS. 2012 Oct-Dec;16(4):530-6.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Sep;163(3):1016-21; discussion 1021-3.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Mar;121(3):654-73.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Sep;120(3):516-23.

6. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002 Nov;9(4):474-80.

7. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006 Mar 1;125(1):134-8.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Aug;114(2 Pt 1):231-5.

9. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):218-23.

10. Int J Surg. 2015 Jul;19:27-30.

11. Maturitas. 2006 Feb 20;53(3):282-98.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Oct;124(4):705-8.

Dr. Pierce is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Vaginal cuff dehiscence, or separation of the vaginal incision, is a rare postoperative complication unique to hysterectomy. Morbidity related to evisceration of abdominal contents can be profound and prompt intervention is required.

A 10-year observational study of 11,000 patients described a 0.24% cumulative incidence after all modes of hysterectomy.1 Though data are varied, the mode of hysterectomy does have an impact on the risk of dehiscence.

Laparoscopic (0.64%-1.35%) and robotic (0.46%-1.5%) hysterectomy have a higher incidence than abdominal (0.15%-0.26%) and vaginal (0.08%-0.25%) approaches.2 The use of monopolar cautery for colpotomy and different closure techniques may account for these differences.

Cuff cellulitis, early sexual intercourse, cigarette smoking, poor nutrition, obesity, menopausal status, and corticosteroid use are all proposed risk factors that promote infection, pressure at the vaginal cuff, and poor wound healing. Although some are modifiable, the rarity of this complication has made establishing causality and promoting prevention challenging.

Prevention

• Preoperatively. Treating bacterial vaginosis, Trichomonas vaginalis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia can decrease the risk of cuff cellulitis and dehiscence.3

• Intraoperatively. Surgeons should ensure adequate vaginal margins (greater than 1 cm) with full-thickness cuff closures while avoiding excessive electrocautery.4 Retrospective data show that transvaginal cuff closure is associated with a decreased risk of dehiscence.5 However, given the lack of randomized data and the difficulty controlling for surgeon experience, gynecologists should use the approach that they are most comfortable with. Though the various laparoscopic cuff closure techniques have limited evidence regarding superiority, some experts propose using two-layer cuff closure and barbed sutures.6-8 Several retrospective studies have found an equivalent or a decreased incidence of cuff dehiscence with barbed sutures, compared with other methods (e.g., 0-Vicryl, Endo Stitch).9,10

• Postoperatively. Women should avoid intercourse and lifting more than 15 pounds for at least 6-8 weeks as the vaginal cuff gains tensile strength. Vaginal estrogen can promote healing in postmenopausal patients.11

Management

Patients with vaginal cuff dehiscence commonly present within the first several weeks to months after surgery with pelvic pain (60%-100%), vaginal bleeding (30%-60%), vaginal discharge (30%), or vaginal pressure/mass (30%).1,7 Posthysterectomy patients with these complaints warrant an urgent evaluation. The diagnosis is made during a pelvic exam.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are necessary because all vaginal cuff separations or dehiscences expose the peritoneal cavity to vaginal flora. Nonsurgical management is reasonable for small separations – less than 25% of the cuff – if there is no evidence of evisceration.

However, surgically closing all recognized cuff dehiscences is reasonable, given the potential for further separation. A vaginal approach is preferred when possible. Women with vaginal cuff dehiscence, stable vital signs, and no evidence of bowel evisceration can be repaired vaginally without an abdominal survey.

In contrast, women with bowel evisceration have a surgical emergency because of the risk of peritonitis and bowel injury. If the eviscerated bowel is not reducible, it should be irrigated and wrapped in a warm moist towel or gauze in preparation for inspection and reduction in the operating room. If the bowel is reducible, the patient can be placed in Trendelenburg’s position. Her vagina should be packed to reduce the risk of re-evisceration as she moves toward operative cuff repair.

If the physician is concerned about bowel injury, inspection via laparoscopy or laparotomy would be reasonable. However, when bowel injury is not suspected, a vaginal technique for dehiscence repair has been described by Matthews et al.:12

1. Expose the cuff with a weighted speculum and Breisky-Navratil retractors.

2. Sharply debride the cuff edges back to viable tissue.

3. Dissect adherent bowel or omentum to allow for full-thickness closure.

4. Place full-thickness, interrupted delayed absorbable sutures to reapproximate the cuff edges.

Cuff dehiscence is a rare but potentially morbid complication of hysterectomy. Prevention, recognition, and appropriate management can avoid life-threatening sequelae.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Oct;118(4):794-801.

2. JSLS. 2012 Oct-Dec;16(4):530-6.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Sep;163(3):1016-21; discussion 1021-3.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Mar;121(3):654-73.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Sep;120(3):516-23.

6. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002 Nov;9(4):474-80.

7. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006 Mar 1;125(1):134-8.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Aug;114(2 Pt 1):231-5.

9. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):218-23.

10. Int J Surg. 2015 Jul;19:27-30.

11. Maturitas. 2006 Feb 20;53(3):282-98.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Oct;124(4):705-8.

Dr. Pierce is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Vaginal cuff dehiscence, or separation of the vaginal incision, is a rare postoperative complication unique to hysterectomy. Morbidity related to evisceration of abdominal contents can be profound and prompt intervention is required.

A 10-year observational study of 11,000 patients described a 0.24% cumulative incidence after all modes of hysterectomy.1 Though data are varied, the mode of hysterectomy does have an impact on the risk of dehiscence.

Laparoscopic (0.64%-1.35%) and robotic (0.46%-1.5%) hysterectomy have a higher incidence than abdominal (0.15%-0.26%) and vaginal (0.08%-0.25%) approaches.2 The use of monopolar cautery for colpotomy and different closure techniques may account for these differences.

Cuff cellulitis, early sexual intercourse, cigarette smoking, poor nutrition, obesity, menopausal status, and corticosteroid use are all proposed risk factors that promote infection, pressure at the vaginal cuff, and poor wound healing. Although some are modifiable, the rarity of this complication has made establishing causality and promoting prevention challenging.

Prevention

• Preoperatively. Treating bacterial vaginosis, Trichomonas vaginalis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia can decrease the risk of cuff cellulitis and dehiscence.3

• Intraoperatively. Surgeons should ensure adequate vaginal margins (greater than 1 cm) with full-thickness cuff closures while avoiding excessive electrocautery.4 Retrospective data show that transvaginal cuff closure is associated with a decreased risk of dehiscence.5 However, given the lack of randomized data and the difficulty controlling for surgeon experience, gynecologists should use the approach that they are most comfortable with. Though the various laparoscopic cuff closure techniques have limited evidence regarding superiority, some experts propose using two-layer cuff closure and barbed sutures.6-8 Several retrospective studies have found an equivalent or a decreased incidence of cuff dehiscence with barbed sutures, compared with other methods (e.g., 0-Vicryl, Endo Stitch).9,10

• Postoperatively. Women should avoid intercourse and lifting more than 15 pounds for at least 6-8 weeks as the vaginal cuff gains tensile strength. Vaginal estrogen can promote healing in postmenopausal patients.11

Management

Patients with vaginal cuff dehiscence commonly present within the first several weeks to months after surgery with pelvic pain (60%-100%), vaginal bleeding (30%-60%), vaginal discharge (30%), or vaginal pressure/mass (30%).1,7 Posthysterectomy patients with these complaints warrant an urgent evaluation. The diagnosis is made during a pelvic exam.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are necessary because all vaginal cuff separations or dehiscences expose the peritoneal cavity to vaginal flora. Nonsurgical management is reasonable for small separations – less than 25% of the cuff – if there is no evidence of evisceration.

However, surgically closing all recognized cuff dehiscences is reasonable, given the potential for further separation. A vaginal approach is preferred when possible. Women with vaginal cuff dehiscence, stable vital signs, and no evidence of bowel evisceration can be repaired vaginally without an abdominal survey.

In contrast, women with bowel evisceration have a surgical emergency because of the risk of peritonitis and bowel injury. If the eviscerated bowel is not reducible, it should be irrigated and wrapped in a warm moist towel or gauze in preparation for inspection and reduction in the operating room. If the bowel is reducible, the patient can be placed in Trendelenburg’s position. Her vagina should be packed to reduce the risk of re-evisceration as she moves toward operative cuff repair.

If the physician is concerned about bowel injury, inspection via laparoscopy or laparotomy would be reasonable. However, when bowel injury is not suspected, a vaginal technique for dehiscence repair has been described by Matthews et al.:12

1. Expose the cuff with a weighted speculum and Breisky-Navratil retractors.

2. Sharply debride the cuff edges back to viable tissue.

3. Dissect adherent bowel or omentum to allow for full-thickness closure.

4. Place full-thickness, interrupted delayed absorbable sutures to reapproximate the cuff edges.

Cuff dehiscence is a rare but potentially morbid complication of hysterectomy. Prevention, recognition, and appropriate management can avoid life-threatening sequelae.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Oct;118(4):794-801.

2. JSLS. 2012 Oct-Dec;16(4):530-6.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Sep;163(3):1016-21; discussion 1021-3.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Mar;121(3):654-73.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Sep;120(3):516-23.

6. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002 Nov;9(4):474-80.

7. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006 Mar 1;125(1):134-8.

8. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Aug;114(2 Pt 1):231-5.

9. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Mar-Apr;18(2):218-23.

10. Int J Surg. 2015 Jul;19:27-30.

11. Maturitas. 2006 Feb 20;53(3):282-98.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Oct;124(4):705-8.

Dr. Pierce is a gynecologic oncology fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology and professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

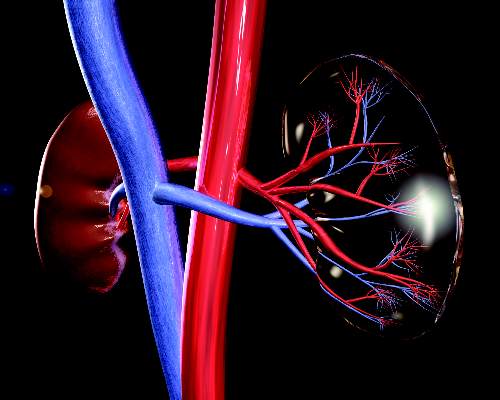

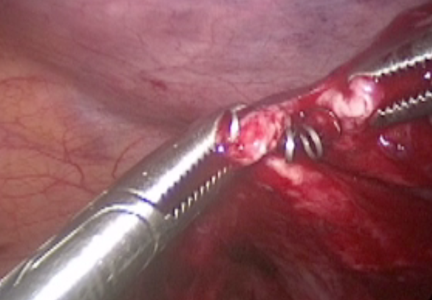

Laparoscopic salpingectomy and cornual resection repurposed

I am pleased to introduce this month’s video, from the Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (MIGS) at Penn State. Dr. Michelle Pacis addresses an increasingly important topic to MIGS surgeons: removal of previously hysteroscopically placed tubal occlusion devices. These devices offer a permanent alterative to laparoscopic sterilization. If women require their removal, however, whether desired or because of complications, gynecologic surgeons must be familiar with the steps involved.

The following video was produced in order to demonstrate a reproducible technique for laparoscopic removal of a device for women requesting this procedure. Key objectives of the video include:

- review of the techniques available to remove hysteroscopic tubal occlusion devices, as well as the contraindications and advantages/disadvantages of these approaches.

- discuss recommended imaging and materials required for the technique described and tips for their use.

- demonstrate salpingectomy and repair technique.

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

I am pleased to introduce this month’s video, from the Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (MIGS) at Penn State. Dr. Michelle Pacis addresses an increasingly important topic to MIGS surgeons: removal of previously hysteroscopically placed tubal occlusion devices. These devices offer a permanent alterative to laparoscopic sterilization. If women require their removal, however, whether desired or because of complications, gynecologic surgeons must be familiar with the steps involved.

The following video was produced in order to demonstrate a reproducible technique for laparoscopic removal of a device for women requesting this procedure. Key objectives of the video include:

- review of the techniques available to remove hysteroscopic tubal occlusion devices, as well as the contraindications and advantages/disadvantages of these approaches.

- discuss recommended imaging and materials required for the technique described and tips for their use.

- demonstrate salpingectomy and repair technique.

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

I am pleased to introduce this month’s video, from the Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (MIGS) at Penn State. Dr. Michelle Pacis addresses an increasingly important topic to MIGS surgeons: removal of previously hysteroscopically placed tubal occlusion devices. These devices offer a permanent alterative to laparoscopic sterilization. If women require their removal, however, whether desired or because of complications, gynecologic surgeons must be familiar with the steps involved.

The following video was produced in order to demonstrate a reproducible technique for laparoscopic removal of a device for women requesting this procedure. Key objectives of the video include:

- review of the techniques available to remove hysteroscopic tubal occlusion devices, as well as the contraindications and advantages/disadvantages of these approaches.

- discuss recommended imaging and materials required for the technique described and tips for their use.

- demonstrate salpingectomy and repair technique.

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

Failure to convert to laparotomy: $6.25M settlement

Failure to convert to laparotomy: $6.25M settlement

A 67-year-old woman with urinary incontinence underwent robot-assisted laparoscopic prolapse surgery and hysterectomy. Complications arose, including an injury to the transverse colon. Postoperatively, the patient developed sepsis and had multiple surgeries. At the time of trial, she used a colostomy bag and had a malabsorption syndrome that required frequent intravenous treatment for dehydration.

Patient's claim:

The gynecologist deviated from the standard of care by failing to convert from a laparoscopic procedure to an open procedure when complications developed.

Defendants' defense:

The procedure was properly performed.

Verdict:

A $6.25 million New Jersey settlement was reached, paid jointly by the gynecologist and the medical center.

Circumcision requires revision

A day after birth, a baby underwent circumcision performed by the mother’s ObGyn. Revision surgery was performed 2.5 years later. When the boy was age 7 years, urethral stricture developed and was treated.

Parents' claim:

Circumcision was improperly performed. Once the child was able to talk, he said that his penis constantly hurt. Pain was only relieved by revision surgery.

Physician's defense:

There was no negligence. Redundant foreskin is often left following a circumcision.

Verdict:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Mother with CP has child with CP

A pregnant woman with cerebral palsy (CP) reported a prior preterm delivery at 24 weeks’ gestation to a high-risk prenatal clinic. At that time, she was offered synthetic progesterone (170HP) injections, but she declined because of the cost. She declined 170HP several times. Nine weeks after her initial visit, she declined 170HP despite ultrasonography (US) showing a shortened cervical length (25 mm) for the gestational age. In 2 weeks, when the cervical length measured 9 mm, she was hospitalized to rule out preterm labor but, before tests began, she left the hospital. Five days later, when her cervical length was 11 mm, she received the first 170HP injection. In the next month she received 4 injections, but she failed to show for the fifth injection and US. The next day, she went to the hospital with cramping. She was given steroids and medication to stop labor. US results indicated that the baby was in breech position. The mother consented to cesarean delivery, but the baby was born vaginally an hour later. The child has mild brain damage, CP, developmental delays, and learning disabilities.

Parents' claim: The mother should have been offered vaginal progesterone, which is cheaper. Given the high risk of preterm birth, steroids administered earlier would have improved fetal development. Cesarean delivery should have been performed.

Defendants' defense: Vaginal progesterone was not available at the time. Starting steroids earlier would not have improved fetal outcome. A cesarean delivery was not possible because the baby was in the birth canal.

Verdict: A $3,500,000 Michigan settlement was reached.

Fallopian tubes grow back, pregnancy

A couple decided they did not want more children and sought counseling from the woman’s ObGyn, who recommended laparoscopic tubal ligation. Several months after surgery, the patient became pregnant and gave birth to a son.

Parents' claim:

The additional child placed an economic hardship on the family, now raising 4 children. The youngest child has language delays and learning disabilities.

Physician's defense:

Regrowth of the fallopian tubes resulting in unwanted pregnancy is a known complication of tubal ligation.

Verdict:

A $397,000 Maryland verdict was returned, including funds for the cost of raising the fourth child and to cope with the child’s special needs.

Challenges in managing labor

At 37 weeks' gestation, a woman was hospitalized in labor. At 1:15 pm, she was dilated 3 cm. At 1:30 pm, she was dilated 4−5 cm with increasing contractions and a reassuring fetal heart rate (FHR). The ObGyn covering for the mother’s ObGyn ordered oxytocin augmentation, which started at 2:45 pm. Shortly thereafter, contractions became more frequent and uterine tachysystole was observed. At 4:12 pm, FHR showed multiple deep decelerations with slow recovery. The baseline dropped to a 90-bpm range and remained that way for 17 minutes. At that point, the ObGyn stopped oxytocin and administered terbutaline; the FHR returned to baseline.

After vaginal delivery, the baby’s Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. Two days later, the baby had seizures and was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit. An electroencephalogram confirmed seizure activity. Initial imaging results were normal. However, magnetic resonance imaging performed a week after delivery showed bilateral brain damage. The child has spastic displegia, is unable to ambulate, and is blind.

Parents' claim: A suit was filed against the hospital and both ObGyns. The hospital settled before trial. The case was discontinued against the primary ObGyn. The covering ObGyn allegedly made 4 departures from accepted medical practice that caused the child’s injury: ordering and administering oxytocin, failing to closely monitor the FHR, failing to timely administer terbutaline, and failing to timely respond to and correct tachysystole.

Physician's defense: The child’s injury occurred before or after labor. The pregnancy was complicated by multiple kidney infections. A week before delivery, US revealed a blood-flow abnormality. An intranatal hypoxic event did not cause the injury, proven by the fact that, after terbutaline was administered, the FHR promptly normalized.

Verdict: A $3 million New York settlement was reached with the hospital. A $134 million verdict was returned against the covering ObGyn.

Brachial plexus injury during delivery

At 37 weeks' gestation, a mother was admitted to the hospital for induction of labor. Increasing doses of oxytocin were administered. Near midnight, FHR monitoring indicated fetal distress. The ObGyn was called and he ordered cesarean delivery. Once he arrived and examined the mother, he found no fetal concerns and decided to proceed with the original birth plan. At 3:30 am, the patient was fully dilated and in active labor. The ObGyn used a vacuum extractor. Upon delivery of the baby’s head, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia and called for assistance. The child was born with a near-total brachial plexus injury: avulsions of all 5 brachial plexus nerves with trauma to the cervical nerve roots at C5−C8 and T1. The child has undergone multiple nerve grafts and orthopedic operations.

Parents' claim: Fetal distress should have prompted the ObGyn to perform cesarean delivery. There was no reason to use vacuum extraction. Based on the severity of the outcome, the ObGyn must have applied excessive force and inappropriate traction during delivery maneuvers.

Physician's defense: The standard of care did not require a cesarean delivery. The vacuum extractor did not cause shoulder dystocia. The ObGyn did not apply excessive force or traction to complete the delivery. The extent of the outcome was partially due to a fetal anomaly and hypotonia.

Verdict: An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

HPV-positive pap tests results never reported

A single mother of 4 children underwent Papanicolaou (Pap) tests in 2004, 2005, and 2007 at a federally funded clinic. Each time, she tested positive for oncogenic human papillomaviruses. In 2011, the patient died of cervical cancer.

Estate's claim: The patient was never notified that the results of the 3 Pap tests were abnormal because all correspondence was sent to an outdated address although she had been treated at the same clinic for other issues during that period of time. Cervical dysplasia identified in 2004 progressed to cancer and metastasized, leading to her death 7 years later.

Defendants' defense: The case was settled during trial.

Verdict: A $4,950,000 Illinois settlement was reached.

Failure to convert to laparotomy: $6.25M settlement

A 67-year-old woman with urinary incontinence underwent robot-assisted laparoscopic prolapse surgery and hysterectomy. Complications arose, including an injury to the transverse colon. Postoperatively, the patient developed sepsis and had multiple surgeries. At the time of trial, she used a colostomy bag and had a malabsorption syndrome that required frequent intravenous treatment for dehydration.

Patient's claim:

The gynecologist deviated from the standard of care by failing to convert from a laparoscopic procedure to an open procedure when complications developed.

Defendants' defense:

The procedure was properly performed.

Verdict:

A $6.25 million New Jersey settlement was reached, paid jointly by the gynecologist and the medical center.

Circumcision requires revision

A day after birth, a baby underwent circumcision performed by the mother’s ObGyn. Revision surgery was performed 2.5 years later. When the boy was age 7 years, urethral stricture developed and was treated.

Parents' claim:

Circumcision was improperly performed. Once the child was able to talk, he said that his penis constantly hurt. Pain was only relieved by revision surgery.

Physician's defense:

There was no negligence. Redundant foreskin is often left following a circumcision.

Verdict:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Mother with CP has child with CP

A pregnant woman with cerebral palsy (CP) reported a prior preterm delivery at 24 weeks’ gestation to a high-risk prenatal clinic. At that time, she was offered synthetic progesterone (170HP) injections, but she declined because of the cost. She declined 170HP several times. Nine weeks after her initial visit, she declined 170HP despite ultrasonography (US) showing a shortened cervical length (25 mm) for the gestational age. In 2 weeks, when the cervical length measured 9 mm, she was hospitalized to rule out preterm labor but, before tests began, she left the hospital. Five days later, when her cervical length was 11 mm, she received the first 170HP injection. In the next month she received 4 injections, but she failed to show for the fifth injection and US. The next day, she went to the hospital with cramping. She was given steroids and medication to stop labor. US results indicated that the baby was in breech position. The mother consented to cesarean delivery, but the baby was born vaginally an hour later. The child has mild brain damage, CP, developmental delays, and learning disabilities.

Parents' claim: The mother should have been offered vaginal progesterone, which is cheaper. Given the high risk of preterm birth, steroids administered earlier would have improved fetal development. Cesarean delivery should have been performed.

Defendants' defense: Vaginal progesterone was not available at the time. Starting steroids earlier would not have improved fetal outcome. A cesarean delivery was not possible because the baby was in the birth canal.

Verdict: A $3,500,000 Michigan settlement was reached.

Fallopian tubes grow back, pregnancy

A couple decided they did not want more children and sought counseling from the woman’s ObGyn, who recommended laparoscopic tubal ligation. Several months after surgery, the patient became pregnant and gave birth to a son.

Parents' claim:

The additional child placed an economic hardship on the family, now raising 4 children. The youngest child has language delays and learning disabilities.

Physician's defense:

Regrowth of the fallopian tubes resulting in unwanted pregnancy is a known complication of tubal ligation.

Verdict:

A $397,000 Maryland verdict was returned, including funds for the cost of raising the fourth child and to cope with the child’s special needs.

Challenges in managing labor

At 37 weeks' gestation, a woman was hospitalized in labor. At 1:15 pm, she was dilated 3 cm. At 1:30 pm, she was dilated 4−5 cm with increasing contractions and a reassuring fetal heart rate (FHR). The ObGyn covering for the mother’s ObGyn ordered oxytocin augmentation, which started at 2:45 pm. Shortly thereafter, contractions became more frequent and uterine tachysystole was observed. At 4:12 pm, FHR showed multiple deep decelerations with slow recovery. The baseline dropped to a 90-bpm range and remained that way for 17 minutes. At that point, the ObGyn stopped oxytocin and administered terbutaline; the FHR returned to baseline.

After vaginal delivery, the baby’s Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. Two days later, the baby had seizures and was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit. An electroencephalogram confirmed seizure activity. Initial imaging results were normal. However, magnetic resonance imaging performed a week after delivery showed bilateral brain damage. The child has spastic displegia, is unable to ambulate, and is blind.

Parents' claim: A suit was filed against the hospital and both ObGyns. The hospital settled before trial. The case was discontinued against the primary ObGyn. The covering ObGyn allegedly made 4 departures from accepted medical practice that caused the child’s injury: ordering and administering oxytocin, failing to closely monitor the FHR, failing to timely administer terbutaline, and failing to timely respond to and correct tachysystole.

Physician's defense: The child’s injury occurred before or after labor. The pregnancy was complicated by multiple kidney infections. A week before delivery, US revealed a blood-flow abnormality. An intranatal hypoxic event did not cause the injury, proven by the fact that, after terbutaline was administered, the FHR promptly normalized.

Verdict: A $3 million New York settlement was reached with the hospital. A $134 million verdict was returned against the covering ObGyn.

Brachial plexus injury during delivery

At 37 weeks' gestation, a mother was admitted to the hospital for induction of labor. Increasing doses of oxytocin were administered. Near midnight, FHR monitoring indicated fetal distress. The ObGyn was called and he ordered cesarean delivery. Once he arrived and examined the mother, he found no fetal concerns and decided to proceed with the original birth plan. At 3:30 am, the patient was fully dilated and in active labor. The ObGyn used a vacuum extractor. Upon delivery of the baby’s head, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia and called for assistance. The child was born with a near-total brachial plexus injury: avulsions of all 5 brachial plexus nerves with trauma to the cervical nerve roots at C5−C8 and T1. The child has undergone multiple nerve grafts and orthopedic operations.

Parents' claim: Fetal distress should have prompted the ObGyn to perform cesarean delivery. There was no reason to use vacuum extraction. Based on the severity of the outcome, the ObGyn must have applied excessive force and inappropriate traction during delivery maneuvers.

Physician's defense: The standard of care did not require a cesarean delivery. The vacuum extractor did not cause shoulder dystocia. The ObGyn did not apply excessive force or traction to complete the delivery. The extent of the outcome was partially due to a fetal anomaly and hypotonia.

Verdict: An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

HPV-positive pap tests results never reported

A single mother of 4 children underwent Papanicolaou (Pap) tests in 2004, 2005, and 2007 at a federally funded clinic. Each time, she tested positive for oncogenic human papillomaviruses. In 2011, the patient died of cervical cancer.

Estate's claim: The patient was never notified that the results of the 3 Pap tests were abnormal because all correspondence was sent to an outdated address although she had been treated at the same clinic for other issues during that period of time. Cervical dysplasia identified in 2004 progressed to cancer and metastasized, leading to her death 7 years later.

Defendants' defense: The case was settled during trial.

Verdict: A $4,950,000 Illinois settlement was reached.

Failure to convert to laparotomy: $6.25M settlement

A 67-year-old woman with urinary incontinence underwent robot-assisted laparoscopic prolapse surgery and hysterectomy. Complications arose, including an injury to the transverse colon. Postoperatively, the patient developed sepsis and had multiple surgeries. At the time of trial, she used a colostomy bag and had a malabsorption syndrome that required frequent intravenous treatment for dehydration.

Patient's claim:

The gynecologist deviated from the standard of care by failing to convert from a laparoscopic procedure to an open procedure when complications developed.

Defendants' defense:

The procedure was properly performed.

Verdict:

A $6.25 million New Jersey settlement was reached, paid jointly by the gynecologist and the medical center.

Circumcision requires revision

A day after birth, a baby underwent circumcision performed by the mother’s ObGyn. Revision surgery was performed 2.5 years later. When the boy was age 7 years, urethral stricture developed and was treated.

Parents' claim:

Circumcision was improperly performed. Once the child was able to talk, he said that his penis constantly hurt. Pain was only relieved by revision surgery.

Physician's defense:

There was no negligence. Redundant foreskin is often left following a circumcision.

Verdict:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Mother with CP has child with CP

A pregnant woman with cerebral palsy (CP) reported a prior preterm delivery at 24 weeks’ gestation to a high-risk prenatal clinic. At that time, she was offered synthetic progesterone (170HP) injections, but she declined because of the cost. She declined 170HP several times. Nine weeks after her initial visit, she declined 170HP despite ultrasonography (US) showing a shortened cervical length (25 mm) for the gestational age. In 2 weeks, when the cervical length measured 9 mm, she was hospitalized to rule out preterm labor but, before tests began, she left the hospital. Five days later, when her cervical length was 11 mm, she received the first 170HP injection. In the next month she received 4 injections, but she failed to show for the fifth injection and US. The next day, she went to the hospital with cramping. She was given steroids and medication to stop labor. US results indicated that the baby was in breech position. The mother consented to cesarean delivery, but the baby was born vaginally an hour later. The child has mild brain damage, CP, developmental delays, and learning disabilities.

Parents' claim: The mother should have been offered vaginal progesterone, which is cheaper. Given the high risk of preterm birth, steroids administered earlier would have improved fetal development. Cesarean delivery should have been performed.

Defendants' defense: Vaginal progesterone was not available at the time. Starting steroids earlier would not have improved fetal outcome. A cesarean delivery was not possible because the baby was in the birth canal.

Verdict: A $3,500,000 Michigan settlement was reached.

Fallopian tubes grow back, pregnancy

A couple decided they did not want more children and sought counseling from the woman’s ObGyn, who recommended laparoscopic tubal ligation. Several months after surgery, the patient became pregnant and gave birth to a son.

Parents' claim:

The additional child placed an economic hardship on the family, now raising 4 children. The youngest child has language delays and learning disabilities.

Physician's defense:

Regrowth of the fallopian tubes resulting in unwanted pregnancy is a known complication of tubal ligation.

Verdict:

A $397,000 Maryland verdict was returned, including funds for the cost of raising the fourth child and to cope with the child’s special needs.

Challenges in managing labor

At 37 weeks' gestation, a woman was hospitalized in labor. At 1:15 pm, she was dilated 3 cm. At 1:30 pm, she was dilated 4−5 cm with increasing contractions and a reassuring fetal heart rate (FHR). The ObGyn covering for the mother’s ObGyn ordered oxytocin augmentation, which started at 2:45 pm. Shortly thereafter, contractions became more frequent and uterine tachysystole was observed. At 4:12 pm, FHR showed multiple deep decelerations with slow recovery. The baseline dropped to a 90-bpm range and remained that way for 17 minutes. At that point, the ObGyn stopped oxytocin and administered terbutaline; the FHR returned to baseline.

After vaginal delivery, the baby’s Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. Two days later, the baby had seizures and was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit. An electroencephalogram confirmed seizure activity. Initial imaging results were normal. However, magnetic resonance imaging performed a week after delivery showed bilateral brain damage. The child has spastic displegia, is unable to ambulate, and is blind.

Parents' claim: A suit was filed against the hospital and both ObGyns. The hospital settled before trial. The case was discontinued against the primary ObGyn. The covering ObGyn allegedly made 4 departures from accepted medical practice that caused the child’s injury: ordering and administering oxytocin, failing to closely monitor the FHR, failing to timely administer terbutaline, and failing to timely respond to and correct tachysystole.

Physician's defense: The child’s injury occurred before or after labor. The pregnancy was complicated by multiple kidney infections. A week before delivery, US revealed a blood-flow abnormality. An intranatal hypoxic event did not cause the injury, proven by the fact that, after terbutaline was administered, the FHR promptly normalized.

Verdict: A $3 million New York settlement was reached with the hospital. A $134 million verdict was returned against the covering ObGyn.

Brachial plexus injury during delivery

At 37 weeks' gestation, a mother was admitted to the hospital for induction of labor. Increasing doses of oxytocin were administered. Near midnight, FHR monitoring indicated fetal distress. The ObGyn was called and he ordered cesarean delivery. Once he arrived and examined the mother, he found no fetal concerns and decided to proceed with the original birth plan. At 3:30 am, the patient was fully dilated and in active labor. The ObGyn used a vacuum extractor. Upon delivery of the baby’s head, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia and called for assistance. The child was born with a near-total brachial plexus injury: avulsions of all 5 brachial plexus nerves with trauma to the cervical nerve roots at C5−C8 and T1. The child has undergone multiple nerve grafts and orthopedic operations.

Parents' claim: Fetal distress should have prompted the ObGyn to perform cesarean delivery. There was no reason to use vacuum extraction. Based on the severity of the outcome, the ObGyn must have applied excessive force and inappropriate traction during delivery maneuvers.

Physician's defense: The standard of care did not require a cesarean delivery. The vacuum extractor did not cause shoulder dystocia. The ObGyn did not apply excessive force or traction to complete the delivery. The extent of the outcome was partially due to a fetal anomaly and hypotonia.

Verdict: An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

HPV-positive pap tests results never reported

A single mother of 4 children underwent Papanicolaou (Pap) tests in 2004, 2005, and 2007 at a federally funded clinic. Each time, she tested positive for oncogenic human papillomaviruses. In 2011, the patient died of cervical cancer.

Estate's claim: The patient was never notified that the results of the 3 Pap tests were abnormal because all correspondence was sent to an outdated address although she had been treated at the same clinic for other issues during that period of time. Cervical dysplasia identified in 2004 progressed to cancer and metastasized, leading to her death 7 years later.

Defendants' defense: The case was settled during trial.

Verdict: A $4,950,000 Illinois settlement was reached.

Additional Medical Verdicts

• Circumcision requires revision

• Mother with CP has child with CP

• Fallopian tubes grow back, pregnancy

• Challenges in managing labor

• Brachial plexus injury during delivery

• HPV-positive Pap tests results never reported

Letters to the Editor: Determining fetal demise; SERMS in menopause; Aspirin for preeclampsia; Treating cesarean scar defect

Determining fetal demise

I appreciate and thank Drs. Esplin and Eller for their discussion of fetal monitoring pitfalls. I agree with their sentiment that this is an inexact science. After 40 years of looking at these strips, I am convinced there must be a better way. I look forward to some innovative approach to better determine fetal well-being in labor. This article raises a question I have asked, and sought the answer to, for years.

On occasion, I have diagnosed intrauterine fetal demise by detecting the maternal heart rate with an internal fetal scalp electrode. On one particular occasion, somewhere between the time of admission, spontaneous rupture of membranes, and applying the fetal scalp electrode, the fetus died. This case was similar to the one you describe in which early efforts with the external Doppler were unsatisfactory and fetal status was suspect. My question: “What is the time interval from the moment of fetal death and loss of fetal electrical activity until the fetus becomes an effective conduit for the conduction of the maternal cardiac signal? Is it minutes, hours, days? Clearly, this would be difficult to evaluate other than on animal models, but I have yet to find an answer.

Edward Hall, MD

Edgewood, Kentucky

Drs. Esplin and Eller respond

We are grateful for your interest in our article. Unfortunately the answer to your question about the timing between fetal demise and the appearance of maternal electrocardiac activity detected by a fetal scalp electrode after transmission through the fetal body is not clear. We are not aware of any data that would conclusively prove the time required for this to occur. It is likely that this type of information would require an animal model to elucidate. However, we are aware of at least 2 clinical cases in which fetal cardiac activity was convincingly documented at admission and for several hours intrapartum with subsequent episodic loss of signal and then delivery of a dead fetus wherein retrospective review confirmed that for a period of time the maternal heart rate was recorded and interpreted to be the fetal heart rate. From these experiences we conclude that this is possible shortly after the fetal demise, likely within minutes to hours.

Despite this uncertainty, we are confident that the information in our article will help clinicians identify and correct those instances when the maternal heart rate is being recorded instead of the fetal heart rate. Fortunately, this rarely involves a situation in which there has been an undiagnosed intrauterine fetal demise.

“SERMs” definition inaccurate

I disagree with Drs. Liu and Collins’ description of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) on page S18, in which they state, “Estrogens and SERMs are lipid-soluble steroid hormones that bind to 2 specific hormone receptors, estrogen receptor α and estrogen receptor β…” SERMs are not hormones, and they are defined improperly as such.

Gideon G. Panter, MD

New York, New York

Drs. Liu and Collins respond

Thank you for your interest in our article. SERMs are typically synthetic organic compounds that can activate estrogen receptors or modify activity of the estrogen receptor and, thus, can be considered hormones.

Stop aspirin in pregnancy?

Like many colleagues, I had been stopping low-dose aspirin prior to planned or expected delivery. Evidence suggests a bigger risk of rebound hypercoagulability than bleeding after stopping low-dose aspirin, according to an article on aspirin use in the perioperative period.1 Because of lack of benefit and increased risks of stopping aspirin, it may be time to change our practice and continue aspirin to minimize peridelivery thromboembolic risk.

Mark Jacobs, MD

Mill Valley, CA

Reference

- Gerstein NS, Schulman PM, Gerstein WH, Petersen TR, Tawil I. Should more patients continue aspirin therapy perioperatively?: clinical impact of aspirin withdrawal syndrome. Ann Surg. 2012;255:811–819.

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Jacobs for his advice to continue low-dose aspirin throughout pregnancy in women taking aspirin for prevention of preeclampsia. The review he references is focused on elderly patients taking aspirin for existing heart disease, which is a very different population than pregnant women. There are no high-quality data from clinical trials on whether to continue or stop low-dose aspirin in pregnant women as they approach their due date. I think obstetricians can use their best judgment in making the decision of whether to stop low-dose aspirin at 36 or 37 weeks or continue aspirin throughout the pregnancy.

Technique for preventing cesarean scar defect

I read with interest the proposed treatment options that Dr. Nezhat and colleagues suggested for cesarean scar defect. However, nowhere did I see mention of preventing this defect.

For 30 years I have been closing the hysterotomy in a fashion that I believe leaves no presence of an isthmocele and is a superior closure. I overlap the upper flap with the lower flap and, most importantly, close with chromic catgut. A cesarean scar “niche” occurs with involution of the uterus causing the suture line to bunch up. Chromic catgut has a shorter half-life and will “give;” a suture made of polypropylene will not stretch. I use a running interlocking line with sutures about 0.5 inches apart.

Donald M. Werner, MD

Binghamton, New York

Dr. Nezhat and colleagues respond

We thank Dr. Werner for his inquiry regarding the prevention of cesarean scar defects; as we all agree, the best treatment is prevention. As mentioned in our article, there are no definitive results from the studies published to date that show superiority of one surgical technique over another in regard to hysterotomy closure and prevention of cesarean scar defects. Possible risk factors for developing cesarean scar defects include low (cervical) hysterotomy, single-layer uterine wall closure, use of locking sutures, closure of hysterotomy with endometrial-sparing technique, and multiple cesarean deliveries. Although these factors may be associated with increased risk of cesarean scar defects, additional randomized controlled trials need to be performed prior to being able to offer a recommendation on a conclusive preventative measure. For additional information, I would direct you to references 3 and 4 in our article. We thank you for sharing your positive experience and eagerly await additional studies on the topic.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

Determining fetal demise