User login

Who is liable when a surgical error occurs?

CASE Surgeon accused of operating outside her scope of expertise

A 38-year-old woman (G2 P2002) presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute pelvic pain involving the right lower quadrant (RLQ). The patient had a history of stage IV endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain, primarily affecting the RLQ, that was treated by total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 6 months earlier. Pertinent findings on physical examination included hypoactive bowel sounds and rebound tenderness. The ED physician ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, which showed no evidence of ureteral injury or other abnormality. The gynecologist who performed the surgery 6 months ago evaluated the patient in the ED.

The gynecologist decided to perform operative laparoscopy because of the severity of the patient’s pain and duration of symptoms. Informed consent obtained in the ED before the patient received analgesics included a handwritten note that said “and other indicated procedures.” The patient signed the document prior to being taken to the operating room (OR). Time out occurred in the OR before anesthesia induction. The gynecologist proceeded with laparoscopic adhesiolysis with planned appendectomy, as she was trained. A normal appendix was noted and left intact. RLQ adhesions involving the colon and abdominal wall were treated with electrosurgical cautery. When the gynecologist found adhesions between the liver and diaphragm in the right upper quadrant (RUQ), she continued adhesiolysis. However, the diaphragm was inadvertently punctured.

As the gynecologist attempted to suture the defect laparoscopically, she encountered difficulty and converted to laparotomy. Adhesions were dense and initially precluded adequate closure of the diaphragmatic defect. The gynecologist persisted and ultimately the closure was adequate; laparotomy concluded. Postoperatively, the patient was given a diagnosis of atelectasis, primarily on the right side; a chest tube was placed by the general surgery team. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period and was discharged on postoperative day 5. One month later she returned to the ED with evidence of pneumonia; she was given a diagnosis of empyema, and antibiotics were administered. She responded well and was discharged after 6 days.

The patient filed a malpractice lawsuit against the gynecologist, the hospital, and associated practitioners. The suit made 3 negligence claims: 1) the surgery was improperly performed, as evidenced by the diaphragmatic perforation; 2) the gynecologist was not adequately trained for RUQ surgery, and 3) the hospital should not have permitted RUQ surgery to proceed. The liability claim cited the lack of qualification of a gynecologic surgeon to proceed with surgical intervention near the diaphragm and the associated consequences of practicing outside the scope of expertise.

Fitz-Hugh Curtis syndrome, a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease that may cause adhesions, was raised as the initial finding at the second surgical procedure and documented as such in the operative report. The plaintiff’s counsel questioned whether surgical correction of this syndrome was within the realm of a gynecologic surgeon. The plaintiff’s counsel argued that the laparoscopic surgical procedure involved bowel and liver; diaphragmatic adhesiolysis was not indicated, especially with normal abdominal CT scan results and the absence of RUQ symptoms. The claim specified that the surgery and care, as a consequence of the RUQ adhesiolysis, resulted in atelectasis, pneumonia, and empyema, with pain and suffering. The plaintiff sought unspecified monetary damages for these results.

What’s the verdict?

The case is in negotiation prior to trial.

Legal and medical considerations

“To err is not just human but intrinsically biological and no profession is exempt from fallibility.”1

Error and liability

To err may be human, but human error is not necessarily the cause of every suboptimal medical outcome. In fact, the overall surgical complication rate has been reported at 3.4%.2 Even when there is an error, it may not have been the kind of error that gives rise to medical malpractice liability. When it comes to surgical errors, the most common are those that actually relate to medications given at surgery that appear to be more common—one recent study found that 1 in 20 perioperative medication administrations resulted in a medication error or an adverse drug event.3

Medical error vs medical malpractice

The fact is that medical error and medical malpractice (or professional negligence) are not the same thing. It is critical to understand the difference.

Medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 It is defined as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim,”5 or, in the Canadian literature, “an act of omission or commission in planning or execution that contributes or could contribute to an unintended result.”6 The gamut of medical errors spans (among others) problems with technique, judgment, medication administration, diagnostic and surgical errors, and incomplete record keeping.5

Negligent error, on the other hand, is generally a subset of medical error recognized by the law. It is error that occurs because of carelessness. Technically, to give rise to liability for negligence (or malpractice) there must be duty, breach, causation, and injury. That is, the physician must owe a duty to the patient, the duty must have been breached, and that breach must have caused an injury.7

Usually the duty in medical practice is that the physician must have acted as a reasonable and prudent professional would have performed under the circumstances. For the most part, malpractice is a level of practice that the profession itself would not view as reasonable practice.8 Specialists usually are held to the higher standards of the specialty. It also can be negligent to undertake practice or a procedure for which the physician is not adequately trained, or for failing to refer the patient to another more qualified physician.

The duty in medicine usually arises from the physician-patient relationship (clearly present here). It is reasonably clear in this case that there was an injury, but, in fact, the question is whether the physician acted carelessly in a way that caused that injury. Our facts leave some ambiguity—unfortunately,a common problem in the real world.

It is possible that the gynecologist was negligent in puncturing the diaphragm. It may have been carelessness, for example, in the way the procedure was performed, or in the decision to proceed despite the difficulties encountered. It is also possible that the gynecologist was not appropriately trained and experienced in the surgery that was undertaken, in which case the decision to do the surgery (rather than to refer to another physician) could well have been negligent. In either of those cases, negligence liability (malpractice) is a possibility.

Proving negligence. It is the plaintiff (the patient) who must prove the elements of negligence (including causation).8 The plaintiff will have to demonstrate not only carelessness, but that carelessness is what caused the injuries for which she is seeking compensation. In this case, the injuries are the consequence of puncturing the diaphragm. The potential damages would be the money to cover the additional medical costs and other expenses, lost wages, and noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering.

The hospital’s role in negligence

The issue of informed consent is also raised in this case, with a handwritten note prior to surgery (but the focus of this article is on medical errors). In addition to the gynecologist, the hospital and other medical personnelwere sued. The hospital is responsible for the acts of its agents, notably its employees. Even if the physicians are not technically hospital employees, the hospital may in some cases be responsible. Among other things, the hospital likely has an obligation to prevent physicians from undertaking inappropriate procedures, including those for which the physician is not appropriately trained. If the gynecologist in this case did not have privileges to perform surgery in this category, the hospital may have an obligation to not schedule the surgery or to intraoperatively question her credentials for such a procedure. In any event, the hospital will have a major role in this case and its interests may, in some instances, be inconsistent with the interests of the physician.

Why settlement discussions?

The case description ends with a note that settlement discussions were underway. If the plaintiff must prove all of the elements of negligence, why have these discussions? First, such discussions are common in almost all negligence cases. This does not mean that the case actually will be settled by the insurance company representing the physician or hospital; many malpractice cases simply fade away because the patient drops the action. Second, there are ambiguities in the facts, and it is sometimes impossible to determine whether or not a jury would find negligence. The hospital may be inclined to settle if there is any realistic chance of a jury ruling against it. Paying a small settlement may be worth avoiding high legal expenses and the risk of an adverse outcome at trial.9

Reducing medical/surgical error through a team approach

Recognizing that “human performance can be affected by many factors that include circadian rhythms, state of mind, physical health, attitude, emotions, propensity for certain common mistakes and errors, and cognitive biases,”10 health care professionals have a commitment to reduce the errors in the interest of patient safety and best practice.

The surgical environment is an opportunity to provide a team approach to patient safety. Surgical risk is a reflection of operative performance, the main factor in the development of postoperative complications.11 We wish to broaden the perspective that gynecologic surgeons, like all surgeons, must keep in mind a number of concerns that can be associated with problems related to surgical procedures, including12:

- visual perception difficulties

- stress

- loss of haptic perception (feedback using touch), as with robot-assisted procedures

- lack of situational awareness (a term we borrow from the aviation industry)

- long-term (and short-term) memory problems.

Analysis of surgical errors shows that they are related to, in order of frequency 1:

- surgical technique

- judgment

- inattention to detail

- incomplete understanding of the problem or surgical situation.

Medical errors: Caring for the second victim (you)

Patrice M. Weiss, MD

We use the term “victim” to refer to the patient and her family following a medical error. The phrase “the second victim” was coined by Dr. Albert Wu in an article in the British Medical Journal1 and describes how a clinician and team of health care professionals also can be affected by medical errors.

What signs and symptoms identify a second victim?Those suffering as a second victim may show signs of depression, loss of joy in work, and difficulty sleeping. They also may replay the events, question their own ability, and feel fearful about making another error. These reactions can lead to burnout—a serious issue that 46% of physicians report.2

As colleagues of those involved in a medical error, we should be cognizant of changes in behavior such as excessive irritability, showing up late for work, or agitation. It may be easier to recognize these symptoms in others rather than in ourselves because we often do not take time to examine how our experiences may affect us personally. Heightening awareness can help us recognize those suffering as second victims and identify the second victim symptoms in ourselves.

How can we help second victims?One challenge second victims face is not being allowed to discuss a medical error. Certainly, due to confidentiality requirements during professional liability cases, we should not talk freely about the event. However, silence creates a barrier that prevents a second victim from processing the incident.

Some hospitals offer forums to discuss medical errors, with the goal of preventing reoccurrence: morbidity and mortality conferences, morning report, Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings, and root cause analyses. These forums often are not perceived by institutions’ employees in a positive way. Are they really meant to improve patient care or do they single out an individual or group in a “name/blame/shame game”? An intimidating process will only worsen a second victim’s symptoms. It is not necessary, however, to create a whole new process; it is possible to restructure, reframe, and change the culture of an existing practice.

Some institutions have developed a formalized program to help second victims. The University of Missouri has a “forYOU team,” an internal, rapid response group that provides emotional first aid to the entire team involved in a medical error case. These responders are not from human resources and do not need to be sought out; they are peers who have been educated about the struggles of the second victim. They will not discuss the case or how care was rendered; they naturally and instinctively provide emotional support to their colleagues.

At my institution, the Carilion Clinic at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, “The Trust Program” encourages truth, respectfulness, understanding, support, and transparency. All health care clinicians receive basic training, but many have volunteered for additional instruction to become mentors because they have experienced second-victim symptoms themselves.

Clinicians want assistance when dealing with a medical error. One poll reports that 90% of physicians felt that health care organizations did not adequately help them cope with the stresses associated with a medical error.3 The goal is to have all institutions recognize that clinicians can be affected by a medical error and offer support.

To hear an expanded audiocast from Dr. Weiss on “the second victim” click here.

Dr. Weiss is Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President, Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, Virginia.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–727.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2015. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2015/public/overview#1. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- White AA, Waterman AD, McCotter P, Boyle DJ, Gallagher TH. Supporting health care workers after medical error: considerations for health care leaders. JCOM. 2008;15(5):240–247.

“Inadequacy” with regard to surgical proceduresIndication for surgery is intrinsic to provision of appropriate care. Surgery inherently poses the possibility of unexpected problems. Adequate training and skill, therefore, must include the ability to deal with a range of problems that arise in the course of surgery. The spectrum related to inadequacy as related to surgical problems includes “failed surgery,” defined as “if despite the utmost care of everyone involved and with the responsible consideration of all knowledge, the designed aim is not achieved, surgery by itself has failed.”5 Of paramount importance is the surgeon’s knowledge of technology and the ability to troubleshoot, as well as the OR team’s responsibility for proper maintenance of equipment to ensure optimal functionality.1

Aviation industry studies indicate that “high performing cockpit crews have been shown to devote one third of their communications to discuss threats and mistakes in their environment, while poor performing teams devoted much less, about 5%, of their time to such.”1,13 A well-trained and well-motivated OR nursing team has been equated with reduction in operative time and rate of conversion to laparotomy.14 Outdated instruments may also contribute to surgical errors.1

Moving the “learning curve” out of the OR and into the simulation lab remains valuable, which is also confirmed by the aviation industry.15 The significance of loss of haptic perception continues to be debated between laparoscopic (straight-stick) surgeons and those performing robotic approaches. Does haptic perception play a major role in surgical intervention? Most surgeons do not view loss of haptic perception, as with minimally invasive procedures, as a major impediment to successful surgery. From the legal perspective, loss of haptic perception has not been well addressed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has focused on patient safety in the surgical environment including concerns for wrong-patient surgery, wrong-side surgery, wrong-level surgery, and wrong-part surgery.16 The Joint Commission has identified factors that may enhance the risk of wrong-site surgery: multiple surgeons involved in the case, multiple procedures during a single surgical visit, unusual time pressures to start or complete the surgery, and unusual physical characteristics including morbid obesity or physical deformity.16

10 starting points for medical error preventionSo what are we to do? Consider:

- Using a preprocedure verification checklist.

- Marking the operative site.

- Completing a time out process prior to starting the procedure, according to the Joint Commission protocol. [For more information on Joint Commission-recommended time out protocols and ways to prevent medical errors, click here.]

- Involving the patient in the identification and procedure definition process. (This is an important part of informed consent.)

- Providing appropriate proctoring and sign-off for new procedures and technology.

- Avoiding sleep deprivation situations, especially with regard to emergency procedures.

- Using only radiopaque-labeled materials placed into the operating cavity.

- Considering medication effect on a fetus, if applicable.

- Reducing distractions from pagers, telephone calls, etc.

- Maintaining a “sterile cockpit” (or distraction free) environment for everyone in the OR.

Set the stage for best outcomesA true team approach is an excellent modus operandi before, during, and after surgery,setting the stage for best outcomes for patients.

“As human beings, surgeons will commit errors and for this reason they have to adopt and utilize stringent defense systems to minimize the incidence of these adverse events … Transparency is the first step on the way to a new safety culture with the acknowledgement of errors when they occur with adoption of systems destined to establish their cause and future prevention.”1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Galleano R, Franceschi A, Ciciliot M, Falchero F, Cuschieri A. Errors in laparoscopic surgery: what surgeons should know. Mineva Chir. 2011;66(2):107−117.

- Fabri P, Zyas-Castro J. Human error, not communication and systems, underlies surgical complications. Surgery. 2008;144(4):557−565.

- Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25−34.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error−the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2139. Balogun J, Bramall A, Berstein M. How surgical trainees handle catastrophic errors: a qualitative study. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1179−1184.

- Grober E, Bohnen J. Defining medical error. Can J Surg. 2005;48(1):39−44.

- Anderson RE, ed. Medical Malpractice: A Physician's Sourcebook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc; 2004.

- Mehlman MJ. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. 44 Arizona State Law J. 2012;44:1165−1777. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2205485. Revised February 13, 2013.

- Hyman DA, Silver C. On the table: an examination of medical malpractice, litigation, and methods of reform: healthcare quality, patient safety, and the culture of medicine: "Denial Ain't Just a River in Egypt." New Eng Law Rev. 2012;46:417−931.

- Landers R. Reducing surgical errors: implementing a three-hinge approach to success. AORN J. 2015;101(6):657−665.

- Pettigrew R, Burns H, Carter D. Evaluating surgical risk: the importance of technical factors in determining outcome. Br J Surg. 1987;74(9):791−794.

- Parker W. Understanding errors during laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37(3):437−449.

- Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Analyzing cockpit communications: the links between language, performance, error, and workload. Hum Perf Extrem Environ. 2000;5(1):63−68.

- Kenyon T, Lenker M, Bax R, Swanstrom L. Cost and benefit of the trained laparoscopic team: a comparative study of a designated nursing team vs. a non-trained team. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(8):812−814.

- Woodman R. Surgeons should train like pilots. BMJ. 1999;319:1321.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 464: Patient safety in the surgical environment. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):786−790.

CASE Surgeon accused of operating outside her scope of expertise

A 38-year-old woman (G2 P2002) presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute pelvic pain involving the right lower quadrant (RLQ). The patient had a history of stage IV endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain, primarily affecting the RLQ, that was treated by total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 6 months earlier. Pertinent findings on physical examination included hypoactive bowel sounds and rebound tenderness. The ED physician ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, which showed no evidence of ureteral injury or other abnormality. The gynecologist who performed the surgery 6 months ago evaluated the patient in the ED.

The gynecologist decided to perform operative laparoscopy because of the severity of the patient’s pain and duration of symptoms. Informed consent obtained in the ED before the patient received analgesics included a handwritten note that said “and other indicated procedures.” The patient signed the document prior to being taken to the operating room (OR). Time out occurred in the OR before anesthesia induction. The gynecologist proceeded with laparoscopic adhesiolysis with planned appendectomy, as she was trained. A normal appendix was noted and left intact. RLQ adhesions involving the colon and abdominal wall were treated with electrosurgical cautery. When the gynecologist found adhesions between the liver and diaphragm in the right upper quadrant (RUQ), she continued adhesiolysis. However, the diaphragm was inadvertently punctured.

As the gynecologist attempted to suture the defect laparoscopically, she encountered difficulty and converted to laparotomy. Adhesions were dense and initially precluded adequate closure of the diaphragmatic defect. The gynecologist persisted and ultimately the closure was adequate; laparotomy concluded. Postoperatively, the patient was given a diagnosis of atelectasis, primarily on the right side; a chest tube was placed by the general surgery team. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period and was discharged on postoperative day 5. One month later she returned to the ED with evidence of pneumonia; she was given a diagnosis of empyema, and antibiotics were administered. She responded well and was discharged after 6 days.

The patient filed a malpractice lawsuit against the gynecologist, the hospital, and associated practitioners. The suit made 3 negligence claims: 1) the surgery was improperly performed, as evidenced by the diaphragmatic perforation; 2) the gynecologist was not adequately trained for RUQ surgery, and 3) the hospital should not have permitted RUQ surgery to proceed. The liability claim cited the lack of qualification of a gynecologic surgeon to proceed with surgical intervention near the diaphragm and the associated consequences of practicing outside the scope of expertise.

Fitz-Hugh Curtis syndrome, a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease that may cause adhesions, was raised as the initial finding at the second surgical procedure and documented as such in the operative report. The plaintiff’s counsel questioned whether surgical correction of this syndrome was within the realm of a gynecologic surgeon. The plaintiff’s counsel argued that the laparoscopic surgical procedure involved bowel and liver; diaphragmatic adhesiolysis was not indicated, especially with normal abdominal CT scan results and the absence of RUQ symptoms. The claim specified that the surgery and care, as a consequence of the RUQ adhesiolysis, resulted in atelectasis, pneumonia, and empyema, with pain and suffering. The plaintiff sought unspecified monetary damages for these results.

What’s the verdict?

The case is in negotiation prior to trial.

Legal and medical considerations

“To err is not just human but intrinsically biological and no profession is exempt from fallibility.”1

Error and liability

To err may be human, but human error is not necessarily the cause of every suboptimal medical outcome. In fact, the overall surgical complication rate has been reported at 3.4%.2 Even when there is an error, it may not have been the kind of error that gives rise to medical malpractice liability. When it comes to surgical errors, the most common are those that actually relate to medications given at surgery that appear to be more common—one recent study found that 1 in 20 perioperative medication administrations resulted in a medication error or an adverse drug event.3

Medical error vs medical malpractice

The fact is that medical error and medical malpractice (or professional negligence) are not the same thing. It is critical to understand the difference.

Medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 It is defined as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim,”5 or, in the Canadian literature, “an act of omission or commission in planning or execution that contributes or could contribute to an unintended result.”6 The gamut of medical errors spans (among others) problems with technique, judgment, medication administration, diagnostic and surgical errors, and incomplete record keeping.5

Negligent error, on the other hand, is generally a subset of medical error recognized by the law. It is error that occurs because of carelessness. Technically, to give rise to liability for negligence (or malpractice) there must be duty, breach, causation, and injury. That is, the physician must owe a duty to the patient, the duty must have been breached, and that breach must have caused an injury.7

Usually the duty in medical practice is that the physician must have acted as a reasonable and prudent professional would have performed under the circumstances. For the most part, malpractice is a level of practice that the profession itself would not view as reasonable practice.8 Specialists usually are held to the higher standards of the specialty. It also can be negligent to undertake practice or a procedure for which the physician is not adequately trained, or for failing to refer the patient to another more qualified physician.

The duty in medicine usually arises from the physician-patient relationship (clearly present here). It is reasonably clear in this case that there was an injury, but, in fact, the question is whether the physician acted carelessly in a way that caused that injury. Our facts leave some ambiguity—unfortunately,a common problem in the real world.

It is possible that the gynecologist was negligent in puncturing the diaphragm. It may have been carelessness, for example, in the way the procedure was performed, or in the decision to proceed despite the difficulties encountered. It is also possible that the gynecologist was not appropriately trained and experienced in the surgery that was undertaken, in which case the decision to do the surgery (rather than to refer to another physician) could well have been negligent. In either of those cases, negligence liability (malpractice) is a possibility.

Proving negligence. It is the plaintiff (the patient) who must prove the elements of negligence (including causation).8 The plaintiff will have to demonstrate not only carelessness, but that carelessness is what caused the injuries for which she is seeking compensation. In this case, the injuries are the consequence of puncturing the diaphragm. The potential damages would be the money to cover the additional medical costs and other expenses, lost wages, and noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering.

The hospital’s role in negligence

The issue of informed consent is also raised in this case, with a handwritten note prior to surgery (but the focus of this article is on medical errors). In addition to the gynecologist, the hospital and other medical personnelwere sued. The hospital is responsible for the acts of its agents, notably its employees. Even if the physicians are not technically hospital employees, the hospital may in some cases be responsible. Among other things, the hospital likely has an obligation to prevent physicians from undertaking inappropriate procedures, including those for which the physician is not appropriately trained. If the gynecologist in this case did not have privileges to perform surgery in this category, the hospital may have an obligation to not schedule the surgery or to intraoperatively question her credentials for such a procedure. In any event, the hospital will have a major role in this case and its interests may, in some instances, be inconsistent with the interests of the physician.

Why settlement discussions?

The case description ends with a note that settlement discussions were underway. If the plaintiff must prove all of the elements of negligence, why have these discussions? First, such discussions are common in almost all negligence cases. This does not mean that the case actually will be settled by the insurance company representing the physician or hospital; many malpractice cases simply fade away because the patient drops the action. Second, there are ambiguities in the facts, and it is sometimes impossible to determine whether or not a jury would find negligence. The hospital may be inclined to settle if there is any realistic chance of a jury ruling against it. Paying a small settlement may be worth avoiding high legal expenses and the risk of an adverse outcome at trial.9

Reducing medical/surgical error through a team approach

Recognizing that “human performance can be affected by many factors that include circadian rhythms, state of mind, physical health, attitude, emotions, propensity for certain common mistakes and errors, and cognitive biases,”10 health care professionals have a commitment to reduce the errors in the interest of patient safety and best practice.

The surgical environment is an opportunity to provide a team approach to patient safety. Surgical risk is a reflection of operative performance, the main factor in the development of postoperative complications.11 We wish to broaden the perspective that gynecologic surgeons, like all surgeons, must keep in mind a number of concerns that can be associated with problems related to surgical procedures, including12:

- visual perception difficulties

- stress

- loss of haptic perception (feedback using touch), as with robot-assisted procedures

- lack of situational awareness (a term we borrow from the aviation industry)

- long-term (and short-term) memory problems.

Analysis of surgical errors shows that they are related to, in order of frequency 1:

- surgical technique

- judgment

- inattention to detail

- incomplete understanding of the problem or surgical situation.

Medical errors: Caring for the second victim (you)

Patrice M. Weiss, MD

We use the term “victim” to refer to the patient and her family following a medical error. The phrase “the second victim” was coined by Dr. Albert Wu in an article in the British Medical Journal1 and describes how a clinician and team of health care professionals also can be affected by medical errors.

What signs and symptoms identify a second victim?Those suffering as a second victim may show signs of depression, loss of joy in work, and difficulty sleeping. They also may replay the events, question their own ability, and feel fearful about making another error. These reactions can lead to burnout—a serious issue that 46% of physicians report.2

As colleagues of those involved in a medical error, we should be cognizant of changes in behavior such as excessive irritability, showing up late for work, or agitation. It may be easier to recognize these symptoms in others rather than in ourselves because we often do not take time to examine how our experiences may affect us personally. Heightening awareness can help us recognize those suffering as second victims and identify the second victim symptoms in ourselves.

How can we help second victims?One challenge second victims face is not being allowed to discuss a medical error. Certainly, due to confidentiality requirements during professional liability cases, we should not talk freely about the event. However, silence creates a barrier that prevents a second victim from processing the incident.

Some hospitals offer forums to discuss medical errors, with the goal of preventing reoccurrence: morbidity and mortality conferences, morning report, Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings, and root cause analyses. These forums often are not perceived by institutions’ employees in a positive way. Are they really meant to improve patient care or do they single out an individual or group in a “name/blame/shame game”? An intimidating process will only worsen a second victim’s symptoms. It is not necessary, however, to create a whole new process; it is possible to restructure, reframe, and change the culture of an existing practice.

Some institutions have developed a formalized program to help second victims. The University of Missouri has a “forYOU team,” an internal, rapid response group that provides emotional first aid to the entire team involved in a medical error case. These responders are not from human resources and do not need to be sought out; they are peers who have been educated about the struggles of the second victim. They will not discuss the case or how care was rendered; they naturally and instinctively provide emotional support to their colleagues.

At my institution, the Carilion Clinic at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, “The Trust Program” encourages truth, respectfulness, understanding, support, and transparency. All health care clinicians receive basic training, but many have volunteered for additional instruction to become mentors because they have experienced second-victim symptoms themselves.

Clinicians want assistance when dealing with a medical error. One poll reports that 90% of physicians felt that health care organizations did not adequately help them cope with the stresses associated with a medical error.3 The goal is to have all institutions recognize that clinicians can be affected by a medical error and offer support.

To hear an expanded audiocast from Dr. Weiss on “the second victim” click here.

Dr. Weiss is Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President, Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, Virginia.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–727.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2015. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2015/public/overview#1. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- White AA, Waterman AD, McCotter P, Boyle DJ, Gallagher TH. Supporting health care workers after medical error: considerations for health care leaders. JCOM. 2008;15(5):240–247.

“Inadequacy” with regard to surgical proceduresIndication for surgery is intrinsic to provision of appropriate care. Surgery inherently poses the possibility of unexpected problems. Adequate training and skill, therefore, must include the ability to deal with a range of problems that arise in the course of surgery. The spectrum related to inadequacy as related to surgical problems includes “failed surgery,” defined as “if despite the utmost care of everyone involved and with the responsible consideration of all knowledge, the designed aim is not achieved, surgery by itself has failed.”5 Of paramount importance is the surgeon’s knowledge of technology and the ability to troubleshoot, as well as the OR team’s responsibility for proper maintenance of equipment to ensure optimal functionality.1

Aviation industry studies indicate that “high performing cockpit crews have been shown to devote one third of their communications to discuss threats and mistakes in their environment, while poor performing teams devoted much less, about 5%, of their time to such.”1,13 A well-trained and well-motivated OR nursing team has been equated with reduction in operative time and rate of conversion to laparotomy.14 Outdated instruments may also contribute to surgical errors.1

Moving the “learning curve” out of the OR and into the simulation lab remains valuable, which is also confirmed by the aviation industry.15 The significance of loss of haptic perception continues to be debated between laparoscopic (straight-stick) surgeons and those performing robotic approaches. Does haptic perception play a major role in surgical intervention? Most surgeons do not view loss of haptic perception, as with minimally invasive procedures, as a major impediment to successful surgery. From the legal perspective, loss of haptic perception has not been well addressed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has focused on patient safety in the surgical environment including concerns for wrong-patient surgery, wrong-side surgery, wrong-level surgery, and wrong-part surgery.16 The Joint Commission has identified factors that may enhance the risk of wrong-site surgery: multiple surgeons involved in the case, multiple procedures during a single surgical visit, unusual time pressures to start or complete the surgery, and unusual physical characteristics including morbid obesity or physical deformity.16

10 starting points for medical error preventionSo what are we to do? Consider:

- Using a preprocedure verification checklist.

- Marking the operative site.

- Completing a time out process prior to starting the procedure, according to the Joint Commission protocol. [For more information on Joint Commission-recommended time out protocols and ways to prevent medical errors, click here.]

- Involving the patient in the identification and procedure definition process. (This is an important part of informed consent.)

- Providing appropriate proctoring and sign-off for new procedures and technology.

- Avoiding sleep deprivation situations, especially with regard to emergency procedures.

- Using only radiopaque-labeled materials placed into the operating cavity.

- Considering medication effect on a fetus, if applicable.

- Reducing distractions from pagers, telephone calls, etc.

- Maintaining a “sterile cockpit” (or distraction free) environment for everyone in the OR.

Set the stage for best outcomesA true team approach is an excellent modus operandi before, during, and after surgery,setting the stage for best outcomes for patients.

“As human beings, surgeons will commit errors and for this reason they have to adopt and utilize stringent defense systems to minimize the incidence of these adverse events … Transparency is the first step on the way to a new safety culture with the acknowledgement of errors when they occur with adoption of systems destined to establish their cause and future prevention.”1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Surgeon accused of operating outside her scope of expertise

A 38-year-old woman (G2 P2002) presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute pelvic pain involving the right lower quadrant (RLQ). The patient had a history of stage IV endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain, primarily affecting the RLQ, that was treated by total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 6 months earlier. Pertinent findings on physical examination included hypoactive bowel sounds and rebound tenderness. The ED physician ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, which showed no evidence of ureteral injury or other abnormality. The gynecologist who performed the surgery 6 months ago evaluated the patient in the ED.

The gynecologist decided to perform operative laparoscopy because of the severity of the patient’s pain and duration of symptoms. Informed consent obtained in the ED before the patient received analgesics included a handwritten note that said “and other indicated procedures.” The patient signed the document prior to being taken to the operating room (OR). Time out occurred in the OR before anesthesia induction. The gynecologist proceeded with laparoscopic adhesiolysis with planned appendectomy, as she was trained. A normal appendix was noted and left intact. RLQ adhesions involving the colon and abdominal wall were treated with electrosurgical cautery. When the gynecologist found adhesions between the liver and diaphragm in the right upper quadrant (RUQ), she continued adhesiolysis. However, the diaphragm was inadvertently punctured.

As the gynecologist attempted to suture the defect laparoscopically, she encountered difficulty and converted to laparotomy. Adhesions were dense and initially precluded adequate closure of the diaphragmatic defect. The gynecologist persisted and ultimately the closure was adequate; laparotomy concluded. Postoperatively, the patient was given a diagnosis of atelectasis, primarily on the right side; a chest tube was placed by the general surgery team. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period and was discharged on postoperative day 5. One month later she returned to the ED with evidence of pneumonia; she was given a diagnosis of empyema, and antibiotics were administered. She responded well and was discharged after 6 days.

The patient filed a malpractice lawsuit against the gynecologist, the hospital, and associated practitioners. The suit made 3 negligence claims: 1) the surgery was improperly performed, as evidenced by the diaphragmatic perforation; 2) the gynecologist was not adequately trained for RUQ surgery, and 3) the hospital should not have permitted RUQ surgery to proceed. The liability claim cited the lack of qualification of a gynecologic surgeon to proceed with surgical intervention near the diaphragm and the associated consequences of practicing outside the scope of expertise.

Fitz-Hugh Curtis syndrome, a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease that may cause adhesions, was raised as the initial finding at the second surgical procedure and documented as such in the operative report. The plaintiff’s counsel questioned whether surgical correction of this syndrome was within the realm of a gynecologic surgeon. The plaintiff’s counsel argued that the laparoscopic surgical procedure involved bowel and liver; diaphragmatic adhesiolysis was not indicated, especially with normal abdominal CT scan results and the absence of RUQ symptoms. The claim specified that the surgery and care, as a consequence of the RUQ adhesiolysis, resulted in atelectasis, pneumonia, and empyema, with pain and suffering. The plaintiff sought unspecified monetary damages for these results.

What’s the verdict?

The case is in negotiation prior to trial.

Legal and medical considerations

“To err is not just human but intrinsically biological and no profession is exempt from fallibility.”1

Error and liability

To err may be human, but human error is not necessarily the cause of every suboptimal medical outcome. In fact, the overall surgical complication rate has been reported at 3.4%.2 Even when there is an error, it may not have been the kind of error that gives rise to medical malpractice liability. When it comes to surgical errors, the most common are those that actually relate to medications given at surgery that appear to be more common—one recent study found that 1 in 20 perioperative medication administrations resulted in a medication error or an adverse drug event.3

Medical error vs medical malpractice

The fact is that medical error and medical malpractice (or professional negligence) are not the same thing. It is critical to understand the difference.

Medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 It is defined as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim,”5 or, in the Canadian literature, “an act of omission or commission in planning or execution that contributes or could contribute to an unintended result.”6 The gamut of medical errors spans (among others) problems with technique, judgment, medication administration, diagnostic and surgical errors, and incomplete record keeping.5

Negligent error, on the other hand, is generally a subset of medical error recognized by the law. It is error that occurs because of carelessness. Technically, to give rise to liability for negligence (or malpractice) there must be duty, breach, causation, and injury. That is, the physician must owe a duty to the patient, the duty must have been breached, and that breach must have caused an injury.7

Usually the duty in medical practice is that the physician must have acted as a reasonable and prudent professional would have performed under the circumstances. For the most part, malpractice is a level of practice that the profession itself would not view as reasonable practice.8 Specialists usually are held to the higher standards of the specialty. It also can be negligent to undertake practice or a procedure for which the physician is not adequately trained, or for failing to refer the patient to another more qualified physician.

The duty in medicine usually arises from the physician-patient relationship (clearly present here). It is reasonably clear in this case that there was an injury, but, in fact, the question is whether the physician acted carelessly in a way that caused that injury. Our facts leave some ambiguity—unfortunately,a common problem in the real world.

It is possible that the gynecologist was negligent in puncturing the diaphragm. It may have been carelessness, for example, in the way the procedure was performed, or in the decision to proceed despite the difficulties encountered. It is also possible that the gynecologist was not appropriately trained and experienced in the surgery that was undertaken, in which case the decision to do the surgery (rather than to refer to another physician) could well have been negligent. In either of those cases, negligence liability (malpractice) is a possibility.

Proving negligence. It is the plaintiff (the patient) who must prove the elements of negligence (including causation).8 The plaintiff will have to demonstrate not only carelessness, but that carelessness is what caused the injuries for which she is seeking compensation. In this case, the injuries are the consequence of puncturing the diaphragm. The potential damages would be the money to cover the additional medical costs and other expenses, lost wages, and noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering.

The hospital’s role in negligence

The issue of informed consent is also raised in this case, with a handwritten note prior to surgery (but the focus of this article is on medical errors). In addition to the gynecologist, the hospital and other medical personnelwere sued. The hospital is responsible for the acts of its agents, notably its employees. Even if the physicians are not technically hospital employees, the hospital may in some cases be responsible. Among other things, the hospital likely has an obligation to prevent physicians from undertaking inappropriate procedures, including those for which the physician is not appropriately trained. If the gynecologist in this case did not have privileges to perform surgery in this category, the hospital may have an obligation to not schedule the surgery or to intraoperatively question her credentials for such a procedure. In any event, the hospital will have a major role in this case and its interests may, in some instances, be inconsistent with the interests of the physician.

Why settlement discussions?

The case description ends with a note that settlement discussions were underway. If the plaintiff must prove all of the elements of negligence, why have these discussions? First, such discussions are common in almost all negligence cases. This does not mean that the case actually will be settled by the insurance company representing the physician or hospital; many malpractice cases simply fade away because the patient drops the action. Second, there are ambiguities in the facts, and it is sometimes impossible to determine whether or not a jury would find negligence. The hospital may be inclined to settle if there is any realistic chance of a jury ruling against it. Paying a small settlement may be worth avoiding high legal expenses and the risk of an adverse outcome at trial.9

Reducing medical/surgical error through a team approach

Recognizing that “human performance can be affected by many factors that include circadian rhythms, state of mind, physical health, attitude, emotions, propensity for certain common mistakes and errors, and cognitive biases,”10 health care professionals have a commitment to reduce the errors in the interest of patient safety and best practice.

The surgical environment is an opportunity to provide a team approach to patient safety. Surgical risk is a reflection of operative performance, the main factor in the development of postoperative complications.11 We wish to broaden the perspective that gynecologic surgeons, like all surgeons, must keep in mind a number of concerns that can be associated with problems related to surgical procedures, including12:

- visual perception difficulties

- stress

- loss of haptic perception (feedback using touch), as with robot-assisted procedures

- lack of situational awareness (a term we borrow from the aviation industry)

- long-term (and short-term) memory problems.

Analysis of surgical errors shows that they are related to, in order of frequency 1:

- surgical technique

- judgment

- inattention to detail

- incomplete understanding of the problem or surgical situation.

Medical errors: Caring for the second victim (you)

Patrice M. Weiss, MD

We use the term “victim” to refer to the patient and her family following a medical error. The phrase “the second victim” was coined by Dr. Albert Wu in an article in the British Medical Journal1 and describes how a clinician and team of health care professionals also can be affected by medical errors.

What signs and symptoms identify a second victim?Those suffering as a second victim may show signs of depression, loss of joy in work, and difficulty sleeping. They also may replay the events, question their own ability, and feel fearful about making another error. These reactions can lead to burnout—a serious issue that 46% of physicians report.2

As colleagues of those involved in a medical error, we should be cognizant of changes in behavior such as excessive irritability, showing up late for work, or agitation. It may be easier to recognize these symptoms in others rather than in ourselves because we often do not take time to examine how our experiences may affect us personally. Heightening awareness can help us recognize those suffering as second victims and identify the second victim symptoms in ourselves.

How can we help second victims?One challenge second victims face is not being allowed to discuss a medical error. Certainly, due to confidentiality requirements during professional liability cases, we should not talk freely about the event. However, silence creates a barrier that prevents a second victim from processing the incident.

Some hospitals offer forums to discuss medical errors, with the goal of preventing reoccurrence: morbidity and mortality conferences, morning report, Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings, and root cause analyses. These forums often are not perceived by institutions’ employees in a positive way. Are they really meant to improve patient care or do they single out an individual or group in a “name/blame/shame game”? An intimidating process will only worsen a second victim’s symptoms. It is not necessary, however, to create a whole new process; it is possible to restructure, reframe, and change the culture of an existing practice.

Some institutions have developed a formalized program to help second victims. The University of Missouri has a “forYOU team,” an internal, rapid response group that provides emotional first aid to the entire team involved in a medical error case. These responders are not from human resources and do not need to be sought out; they are peers who have been educated about the struggles of the second victim. They will not discuss the case or how care was rendered; they naturally and instinctively provide emotional support to their colleagues.

At my institution, the Carilion Clinic at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, “The Trust Program” encourages truth, respectfulness, understanding, support, and transparency. All health care clinicians receive basic training, but many have volunteered for additional instruction to become mentors because they have experienced second-victim symptoms themselves.

Clinicians want assistance when dealing with a medical error. One poll reports that 90% of physicians felt that health care organizations did not adequately help them cope with the stresses associated with a medical error.3 The goal is to have all institutions recognize that clinicians can be affected by a medical error and offer support.

To hear an expanded audiocast from Dr. Weiss on “the second victim” click here.

Dr. Weiss is Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President, Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, Virginia.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–727.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2015. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2015/public/overview#1. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- White AA, Waterman AD, McCotter P, Boyle DJ, Gallagher TH. Supporting health care workers after medical error: considerations for health care leaders. JCOM. 2008;15(5):240–247.

“Inadequacy” with regard to surgical proceduresIndication for surgery is intrinsic to provision of appropriate care. Surgery inherently poses the possibility of unexpected problems. Adequate training and skill, therefore, must include the ability to deal with a range of problems that arise in the course of surgery. The spectrum related to inadequacy as related to surgical problems includes “failed surgery,” defined as “if despite the utmost care of everyone involved and with the responsible consideration of all knowledge, the designed aim is not achieved, surgery by itself has failed.”5 Of paramount importance is the surgeon’s knowledge of technology and the ability to troubleshoot, as well as the OR team’s responsibility for proper maintenance of equipment to ensure optimal functionality.1

Aviation industry studies indicate that “high performing cockpit crews have been shown to devote one third of their communications to discuss threats and mistakes in their environment, while poor performing teams devoted much less, about 5%, of their time to such.”1,13 A well-trained and well-motivated OR nursing team has been equated with reduction in operative time and rate of conversion to laparotomy.14 Outdated instruments may also contribute to surgical errors.1

Moving the “learning curve” out of the OR and into the simulation lab remains valuable, which is also confirmed by the aviation industry.15 The significance of loss of haptic perception continues to be debated between laparoscopic (straight-stick) surgeons and those performing robotic approaches. Does haptic perception play a major role in surgical intervention? Most surgeons do not view loss of haptic perception, as with minimally invasive procedures, as a major impediment to successful surgery. From the legal perspective, loss of haptic perception has not been well addressed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has focused on patient safety in the surgical environment including concerns for wrong-patient surgery, wrong-side surgery, wrong-level surgery, and wrong-part surgery.16 The Joint Commission has identified factors that may enhance the risk of wrong-site surgery: multiple surgeons involved in the case, multiple procedures during a single surgical visit, unusual time pressures to start or complete the surgery, and unusual physical characteristics including morbid obesity or physical deformity.16

10 starting points for medical error preventionSo what are we to do? Consider:

- Using a preprocedure verification checklist.

- Marking the operative site.

- Completing a time out process prior to starting the procedure, according to the Joint Commission protocol. [For more information on Joint Commission-recommended time out protocols and ways to prevent medical errors, click here.]

- Involving the patient in the identification and procedure definition process. (This is an important part of informed consent.)

- Providing appropriate proctoring and sign-off for new procedures and technology.

- Avoiding sleep deprivation situations, especially with regard to emergency procedures.

- Using only radiopaque-labeled materials placed into the operating cavity.

- Considering medication effect on a fetus, if applicable.

- Reducing distractions from pagers, telephone calls, etc.

- Maintaining a “sterile cockpit” (or distraction free) environment for everyone in the OR.

Set the stage for best outcomesA true team approach is an excellent modus operandi before, during, and after surgery,setting the stage for best outcomes for patients.

“As human beings, surgeons will commit errors and for this reason they have to adopt and utilize stringent defense systems to minimize the incidence of these adverse events … Transparency is the first step on the way to a new safety culture with the acknowledgement of errors when they occur with adoption of systems destined to establish their cause and future prevention.”1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Galleano R, Franceschi A, Ciciliot M, Falchero F, Cuschieri A. Errors in laparoscopic surgery: what surgeons should know. Mineva Chir. 2011;66(2):107−117.

- Fabri P, Zyas-Castro J. Human error, not communication and systems, underlies surgical complications. Surgery. 2008;144(4):557−565.

- Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25−34.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error−the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2139. Balogun J, Bramall A, Berstein M. How surgical trainees handle catastrophic errors: a qualitative study. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1179−1184.

- Grober E, Bohnen J. Defining medical error. Can J Surg. 2005;48(1):39−44.

- Anderson RE, ed. Medical Malpractice: A Physician's Sourcebook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc; 2004.

- Mehlman MJ. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. 44 Arizona State Law J. 2012;44:1165−1777. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2205485. Revised February 13, 2013.

- Hyman DA, Silver C. On the table: an examination of medical malpractice, litigation, and methods of reform: healthcare quality, patient safety, and the culture of medicine: "Denial Ain't Just a River in Egypt." New Eng Law Rev. 2012;46:417−931.

- Landers R. Reducing surgical errors: implementing a three-hinge approach to success. AORN J. 2015;101(6):657−665.

- Pettigrew R, Burns H, Carter D. Evaluating surgical risk: the importance of technical factors in determining outcome. Br J Surg. 1987;74(9):791−794.

- Parker W. Understanding errors during laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37(3):437−449.

- Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Analyzing cockpit communications: the links between language, performance, error, and workload. Hum Perf Extrem Environ. 2000;5(1):63−68.

- Kenyon T, Lenker M, Bax R, Swanstrom L. Cost and benefit of the trained laparoscopic team: a comparative study of a designated nursing team vs. a non-trained team. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(8):812−814.

- Woodman R. Surgeons should train like pilots. BMJ. 1999;319:1321.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 464: Patient safety in the surgical environment. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):786−790.

- Galleano R, Franceschi A, Ciciliot M, Falchero F, Cuschieri A. Errors in laparoscopic surgery: what surgeons should know. Mineva Chir. 2011;66(2):107−117.

- Fabri P, Zyas-Castro J. Human error, not communication and systems, underlies surgical complications. Surgery. 2008;144(4):557−565.

- Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25−34.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error−the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2139. Balogun J, Bramall A, Berstein M. How surgical trainees handle catastrophic errors: a qualitative study. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1179−1184.

- Grober E, Bohnen J. Defining medical error. Can J Surg. 2005;48(1):39−44.

- Anderson RE, ed. Medical Malpractice: A Physician's Sourcebook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc; 2004.

- Mehlman MJ. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. 44 Arizona State Law J. 2012;44:1165−1777. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2205485. Revised February 13, 2013.

- Hyman DA, Silver C. On the table: an examination of medical malpractice, litigation, and methods of reform: healthcare quality, patient safety, and the culture of medicine: "Denial Ain't Just a River in Egypt." New Eng Law Rev. 2012;46:417−931.

- Landers R. Reducing surgical errors: implementing a three-hinge approach to success. AORN J. 2015;101(6):657−665.

- Pettigrew R, Burns H, Carter D. Evaluating surgical risk: the importance of technical factors in determining outcome. Br J Surg. 1987;74(9):791−794.

- Parker W. Understanding errors during laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37(3):437−449.

- Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Analyzing cockpit communications: the links between language, performance, error, and workload. Hum Perf Extrem Environ. 2000;5(1):63−68.

- Kenyon T, Lenker M, Bax R, Swanstrom L. Cost and benefit of the trained laparoscopic team: a comparative study of a designated nursing team vs. a non-trained team. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(8):812−814.

- Woodman R. Surgeons should train like pilots. BMJ. 1999;319:1321.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 464: Patient safety in the surgical environment. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):786−790.

In this Article

- Medical error vs negligence

- Caring for the second victim

- 10 starting points for reducing medical errors

How gynecologic procedures and pharmacologic treatments can affect the uterus

Transvaginal ultrasound: We are gaining a better understanding of its clinical applications

Steven R. Goldstein, MD

In my first book I coined the phrase "sonomicroscopy." We are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) that you could not see with your naked eye even if you could it hold it at arms length and squint at it. For instance, cardiac activity can be seen easily within an embryo of 4 mm at 47 days since the last menstrual period. If there were any possible way to hold this 4-mm embryo in your hand, you would not appreciate cardiac pulsations contained within it! This is one of the beauties, and yet potential foibles, of TVUS.

In this excellent pictorial article, Michelle Stalnaker Ozcan, MD, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, have done an outstanding job of turning this low-power "sonomicroscope" into the uterus to better understand a number of unique yet important clinical applications of TVUS.

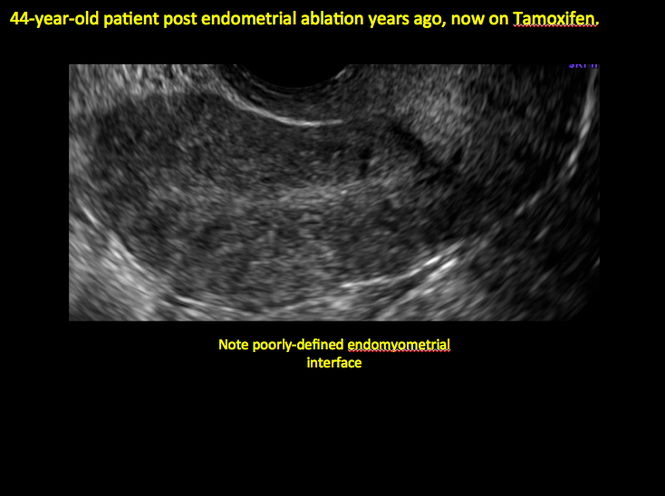

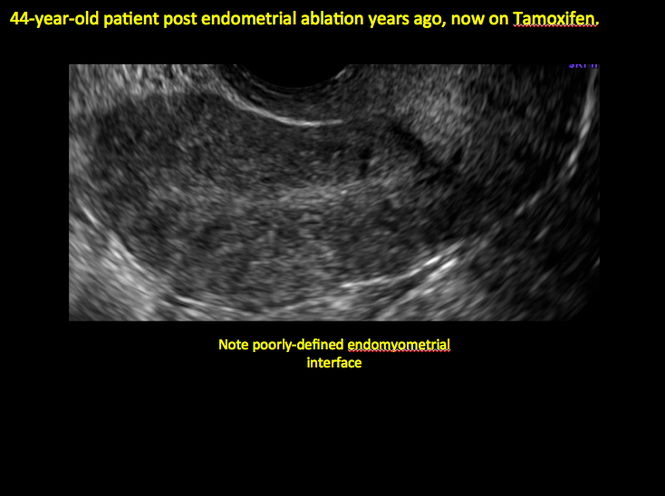

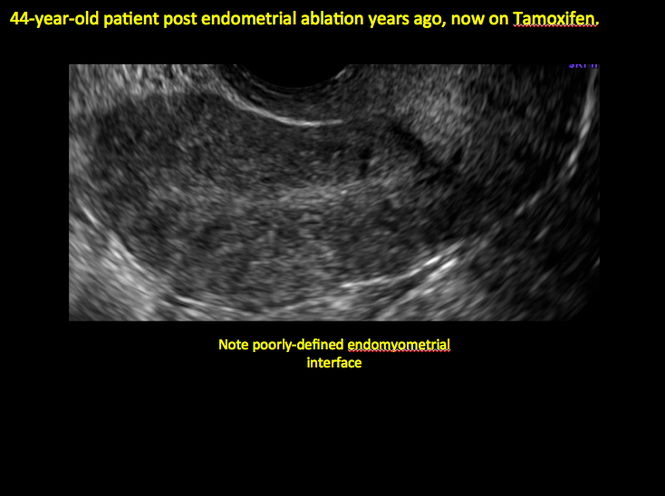

Tamoxifen is known to cause a slight but statistically significant increase in endometrial cancer. In 1994, I first described an unusual ultrasound appearance in the uterus of patients receiving tamoxifen, which was being misinterpreted as "endometrial thickening," and resulted in many unnecessary biopsies and dilation and curettage procedures.1 This type of uterine change has been seen in other selective estrogen-receptor modulators as well.2,3 In this article, Drs. Ozcan and Kaunitz correctly point out that such an ultrasound pattern does not necessitate any intervention in the absence of bleeding.

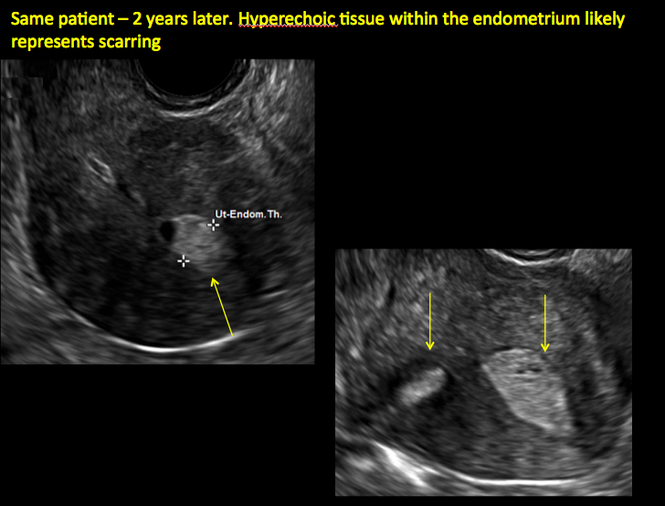

Another common question I am often asked is, "How do we handle the patient whose status is post-endometrial ablation and presents with staining?" The scarring shown in the figures that follow make any kind of meaningful evaluation extremely difficult.

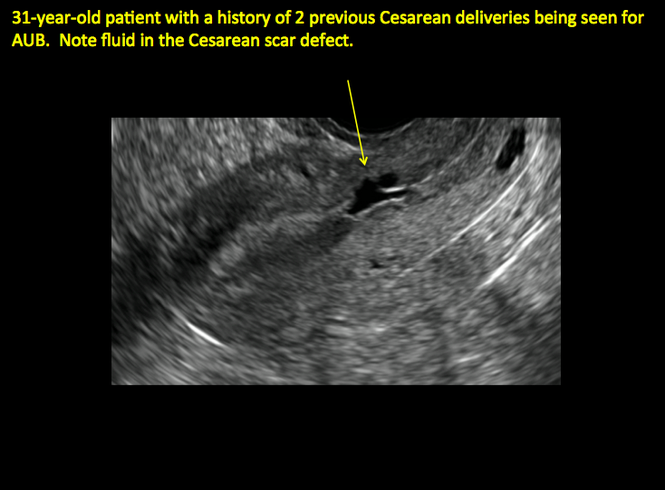

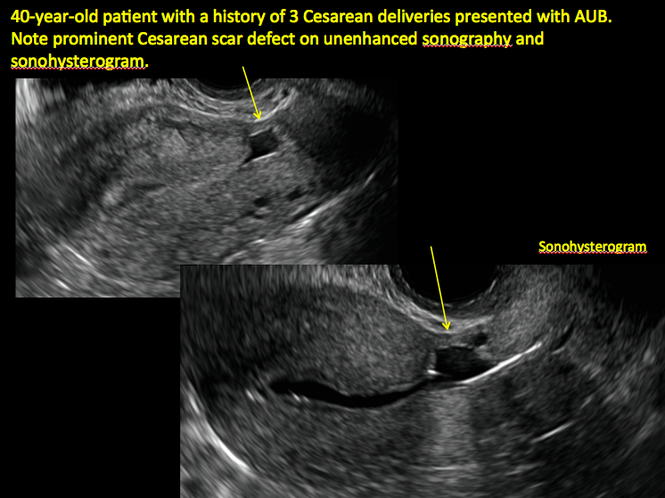

There has been an epidemic of cesarean scar pregnancies when a subsequent gestation implants in the cesarean scar defect.4 Perhaps the time has come when all patients with a previous cesarean delivery should have their lower uterine segment scanned to look for such a defect as shown in the pictures that follow. If we are not yet ready for that, at least early TVUS scans in subsequent pregnancies, in my opinion, should be employed to make an early diagnosis of such cases that are the precursors of morbidly adherent placenta, a potentially life-threatening situation that appears to be increasing in frequency.

Finally, look to obgmanagement.com for next month's web-exclusive look at outstanding images of patients who have undergone transcervical sterilization.

Dr. Goldstein is Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine, Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound, and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center. He also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Dr. Goldstein reports that he has an equipment loan from Philips, and is past President of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine.

References

- Goldstein SR. Unusual ultrasonographic appearance of the uterus in patients receiving tamoxifen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(2):447–451.

- Goldstein SR, Neven P, Cummings S, et al. Postmenopausal evaluation and risk reduction with lasofoxifene (PEARL) trial: 5-year gynecological outcomes. Menopause. 2011;18(1):17–22.

- Goldstein SR, Nanavati N. Adverse events that are associated with the selective estrogen receptor modulator levormeloxifene in an aborted phase III osteoporosis treatment study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):521–527.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14–29.

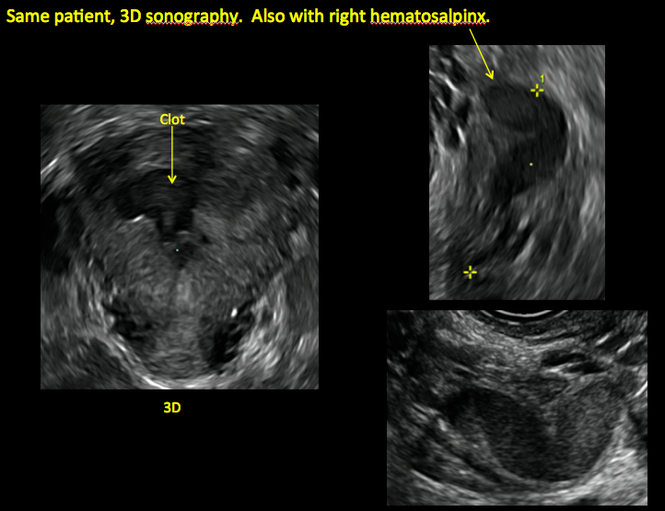

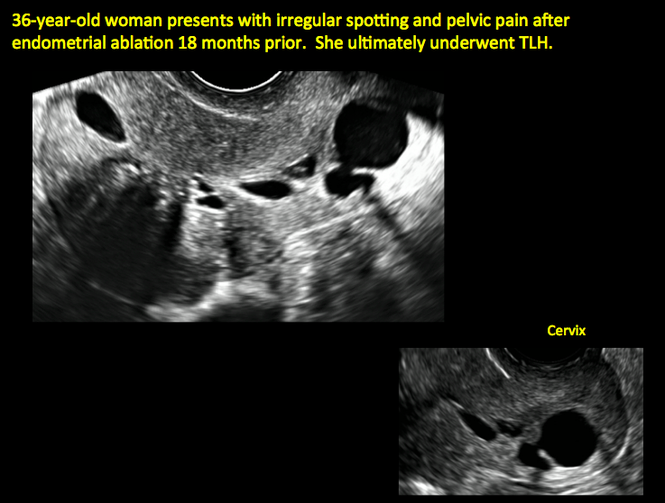

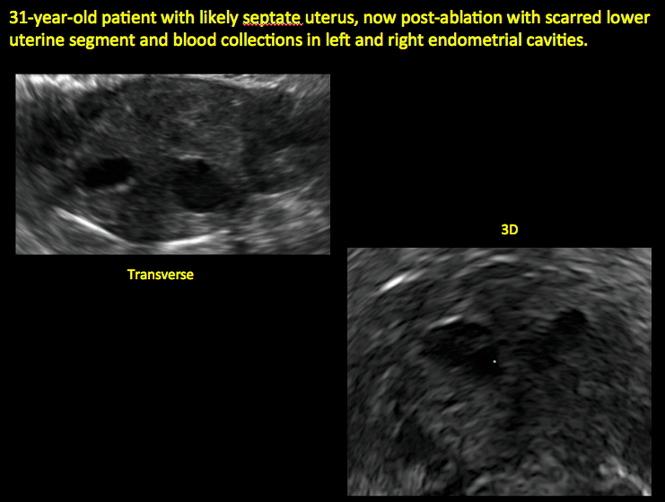

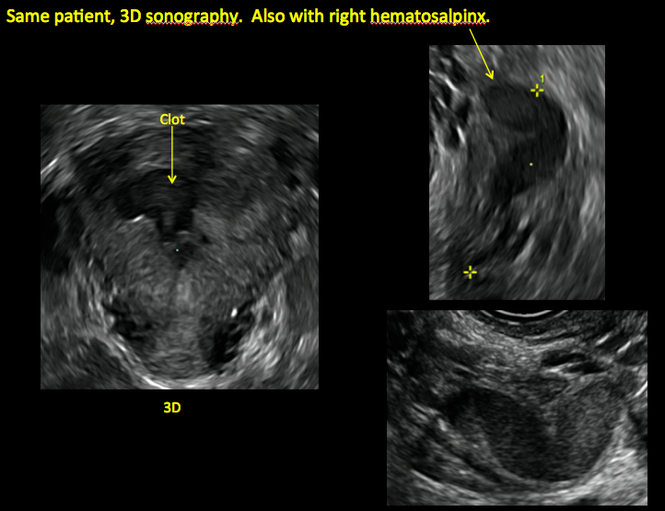

New technology, minimally invasive surgical procedures, and medications continue to change how physicians manage specific medical issues. Many procedures and medications used by gynecologists can cause characteristic findings on sonography. These findings can guide subsequent counseling and management decisions and are important to accurately interpret on imaging. Among these conditions are Asherman syndrome, postendometrial ablation uterine damage, cesarean scar defect, and altered endometrium as a result of tamoxifen use. In this article, we provide 2 dimensional and 3 dimensional sono‑graphic images of uterine presentations of these 4 conditions.

Asherman syndromeCharacterized by variable scarring, or intrauterine adhesions, inside the uterine cavity following endometrial trauma due to surgical procedures, Asherman syndrome can cause menstrual changes and infertility. Should pregnancy occur in the setting of Asherman syndrome, placental abnormalities may result.1 Intrauterine adhesions can follow many surgical procedures, including curettage (diagnostic or for missed/elective abortion or retained products of conception), cesarean delivery, and hysteroscopic myomectomy. They may even occur after spontaneous abortion without curettage. Rates of Asherman syndrome are highest after procedures that tend to cause the most intrauterine inflammation, including2:

- curettage after septic abortion

- late curettage after retained products of conception

- hysteroscopy with multiple myomectomies.

In severe cases Asherman syndrome can result in complete obliteration of the uterine cavity.3

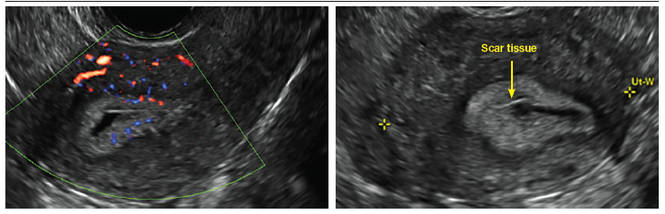

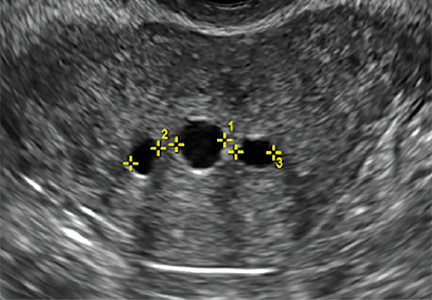

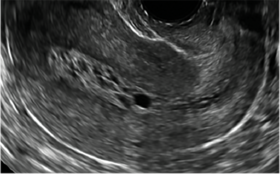

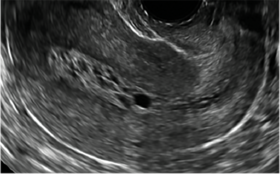

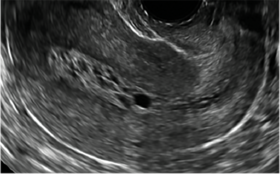

Clinicians should be cognizant of the appearance of Asherman syndrome on imaging because patients reporting menstrual abnormalities, pelvic pain (FIGURE 1), infertility, and other symptoms may exhibit intrauterine lesions on sonohysterography, or sometimes unenhanced sonography if endometrial fluid/blood is present. Depending on symptoms and patient reproductive plans, treatment may be indicated.2

| FIGURE 1 Asherman syndrome | ||||

|

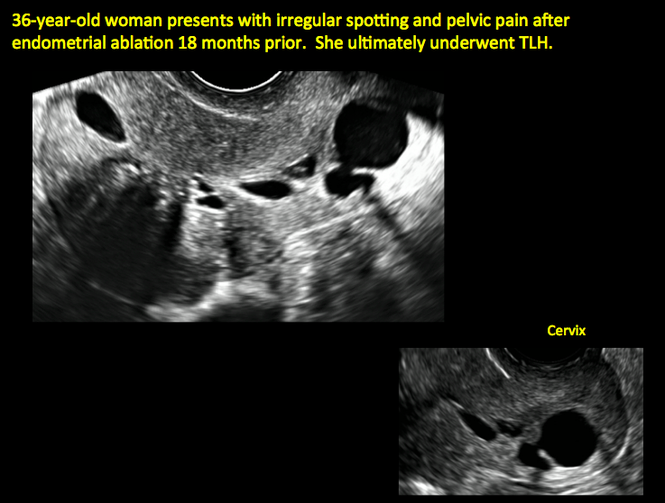

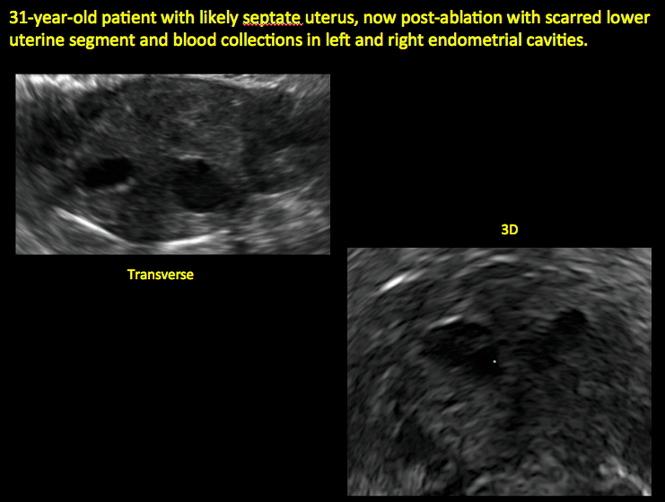

Postablation endometrial destruction

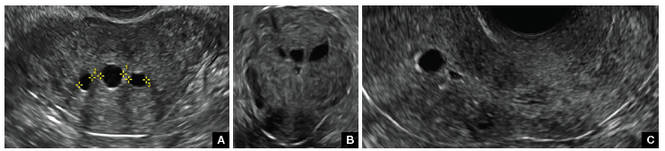

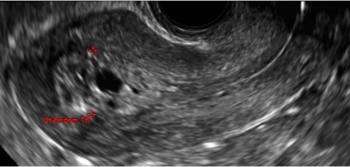

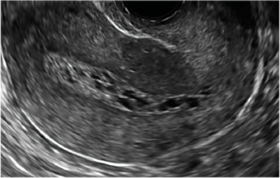

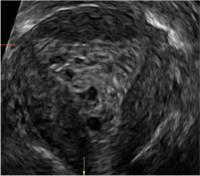

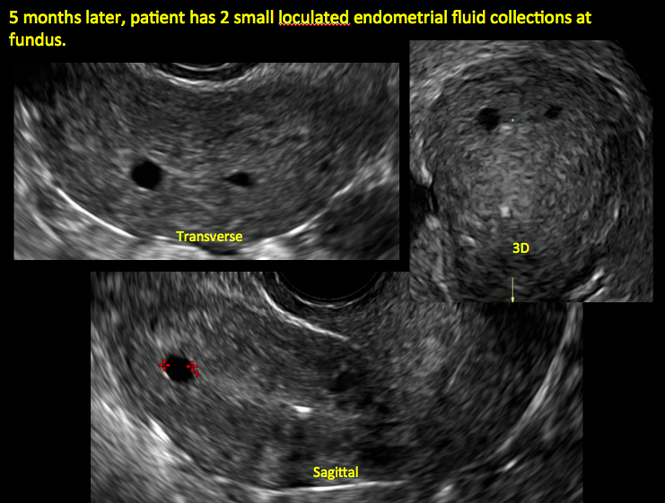

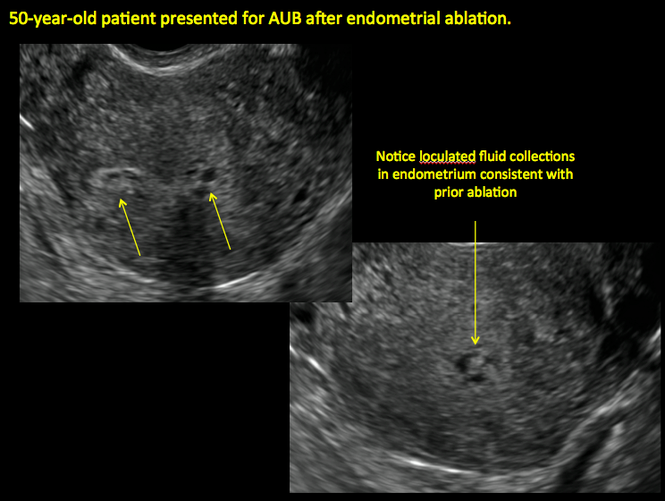

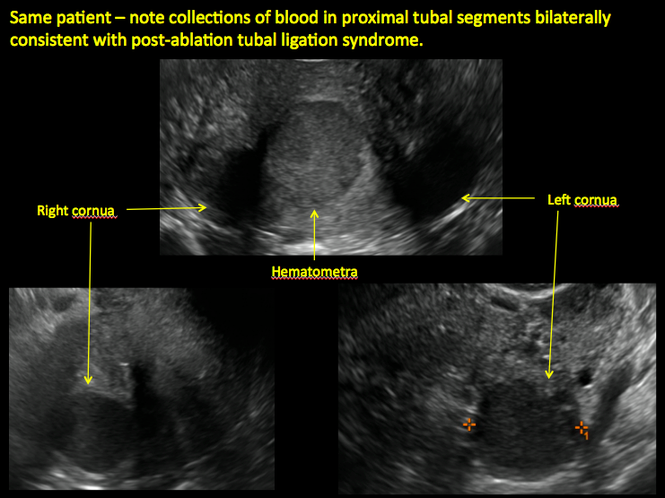

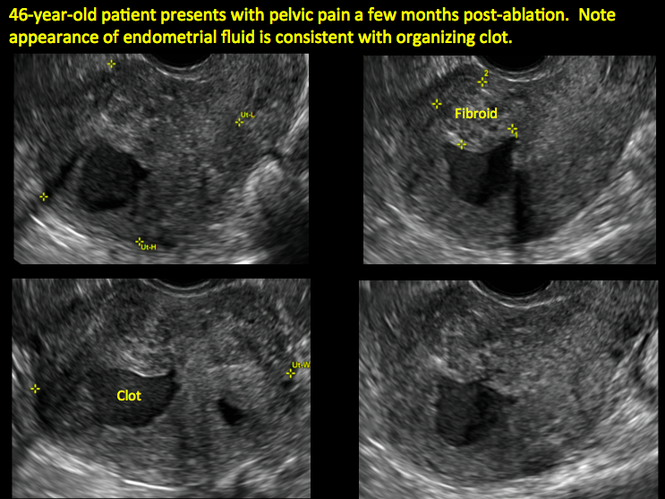

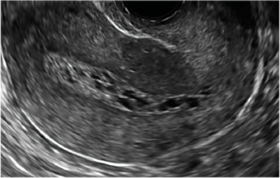

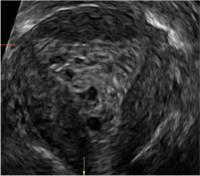

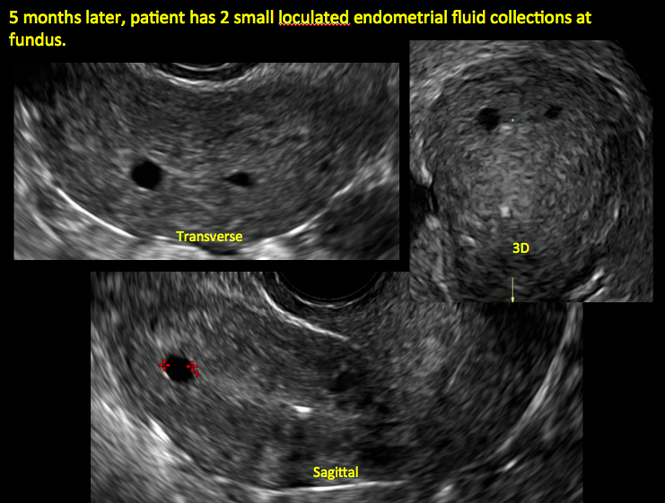

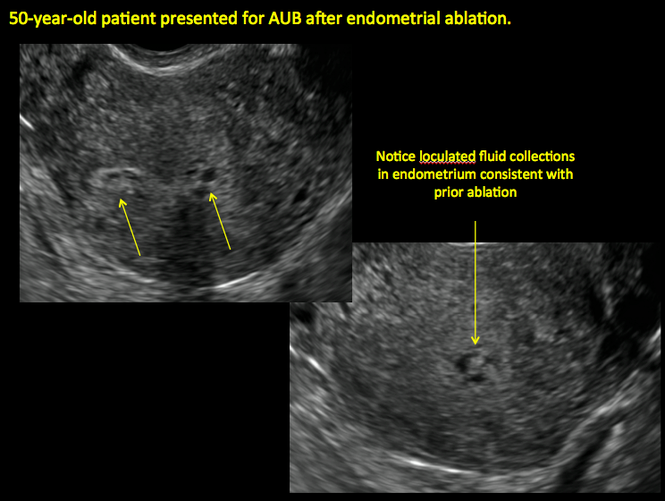

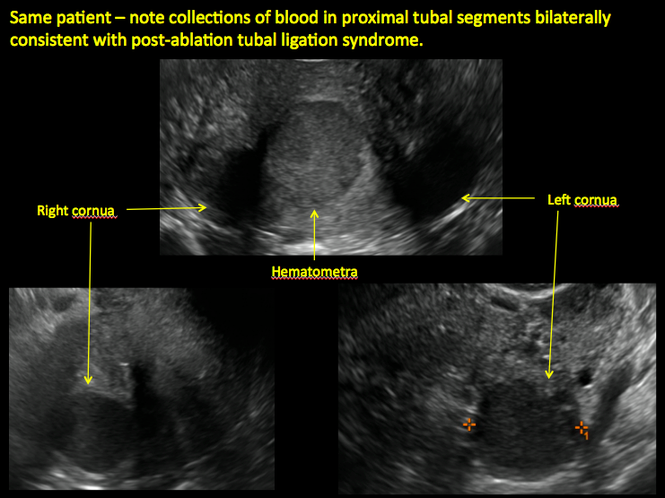

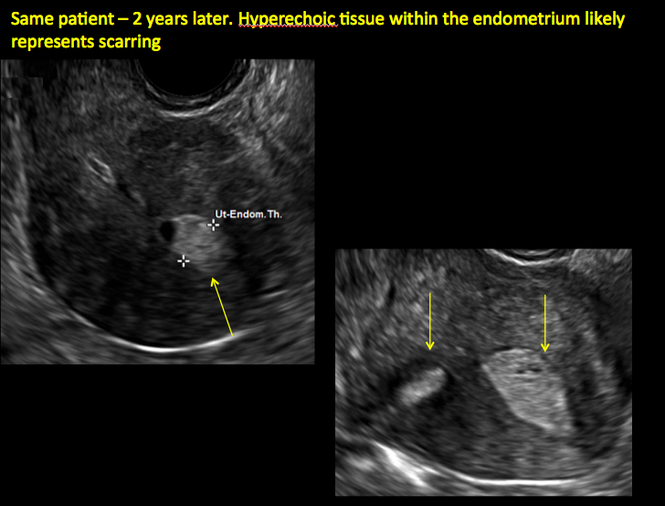

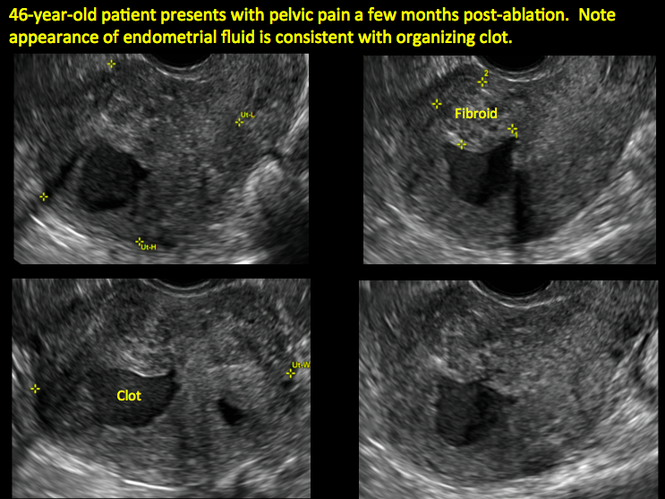

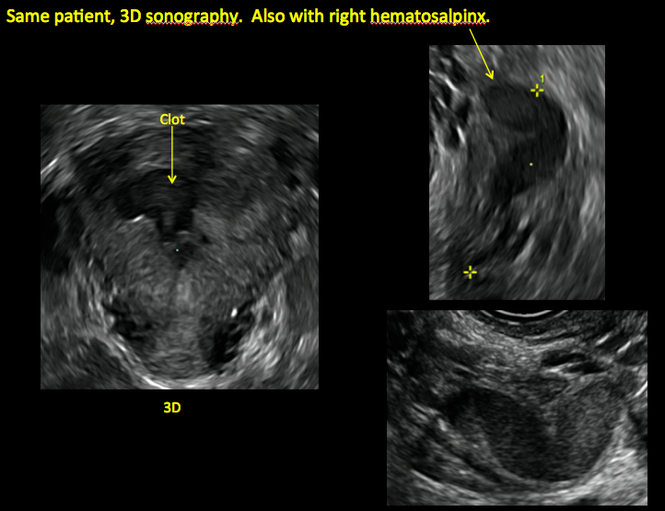

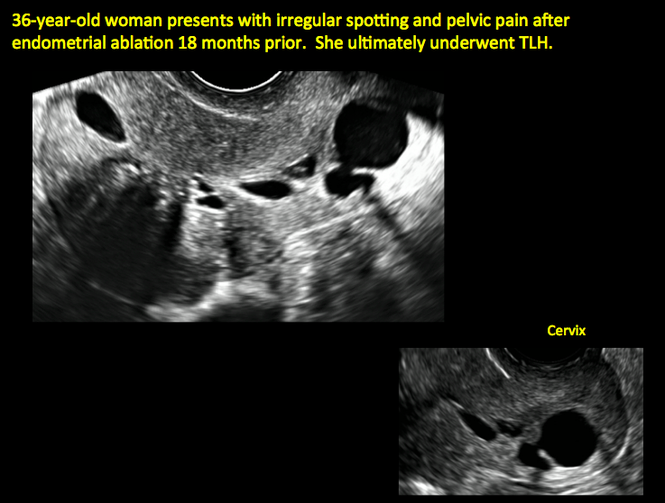

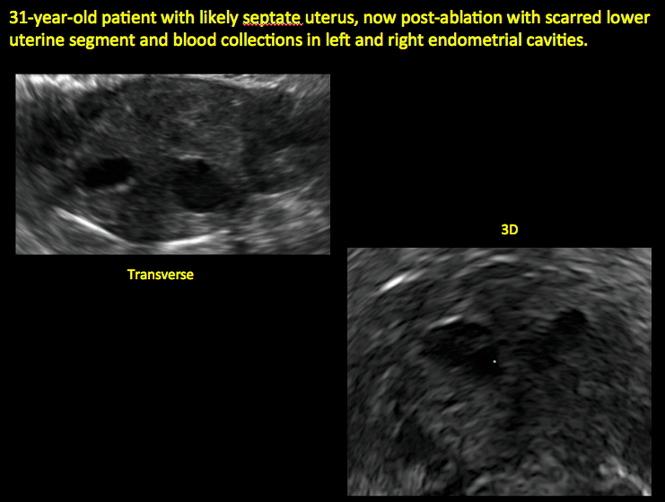

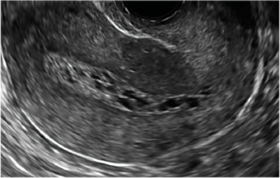

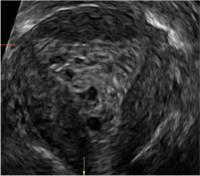

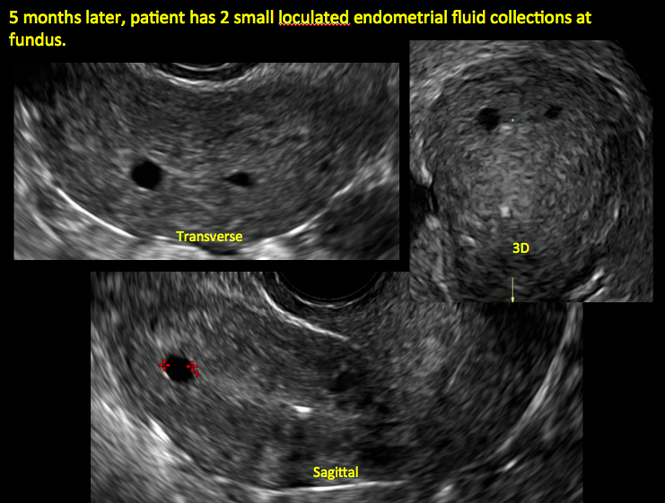

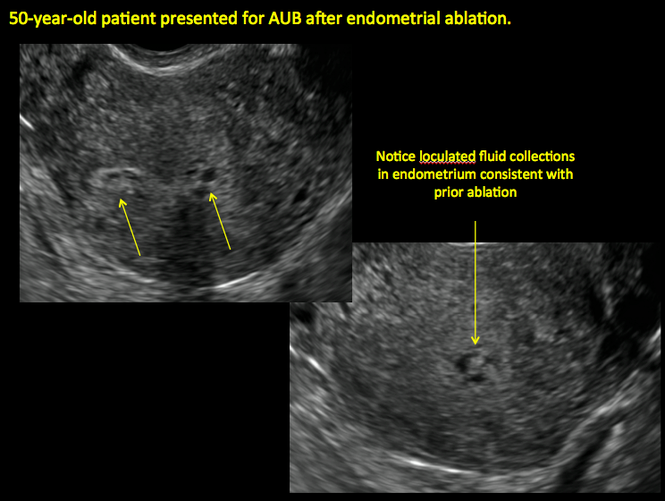

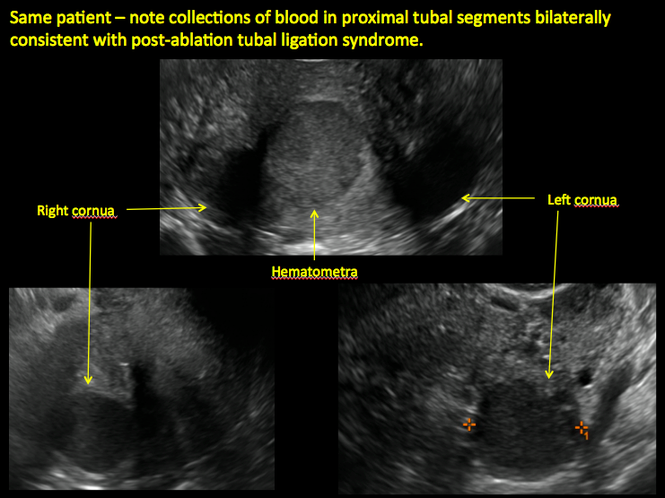

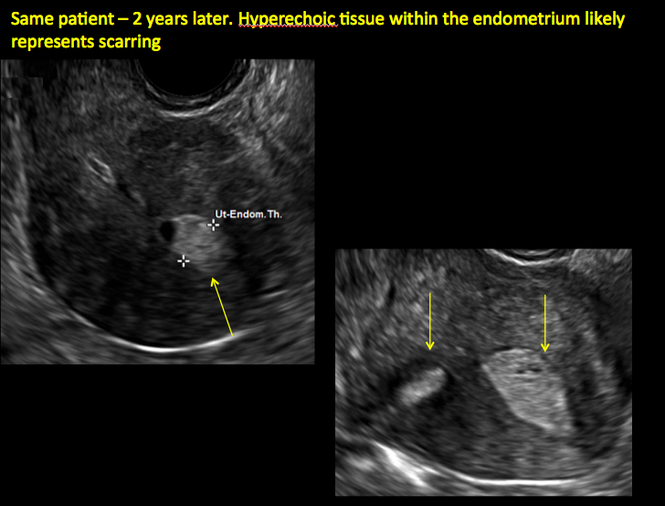

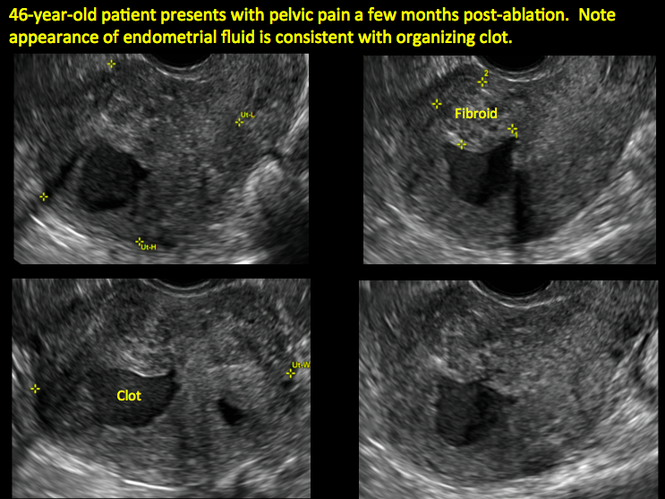

Surgical destruction of the endometrium to the level of the basalis has been associated with the formation of intrauterine adhesions (FIGURE 2) as well as pockets of hematometra (FIGURE 3). In a large Cochrane systematic review, the reported rate of hematometra was 0.9% following non− resectoscopic ablation and 2.4% following resectoscopic ablation.4

FIGURE 2 Intrauterine changes postablation | ||||

| ||||

| Loculated fluid collections in the endometrium on transverse (A), sagittal (B), and 3 dimensional images (C) of a 41-year-old patient who presented with dysmenorrhea 3 years after an endometrial ablation procedure. The patient ultimately underwent transvaginal hysterectomy. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| 2 dimensional sonograms of a 40-year-old patient with a history of bilateral tubal ligation who presented for severe cyclic pelvic pain postablation. |

Postablation tubal sterilization syndrome—cyclic cramping with or without vaginal bleeding—occurs in up to 10% of previously sterilized women who undergo endometrial ablation.4 The syndrome is thought to be caused by bleeding from active endometrium trapped at the uterine cornua by intrauterine adhesions postablation.

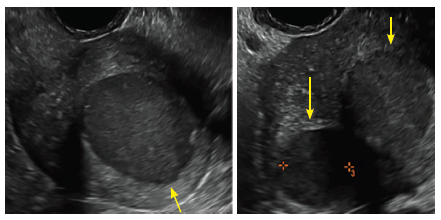

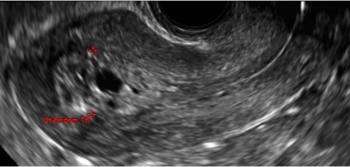

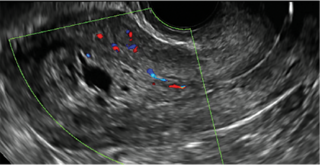

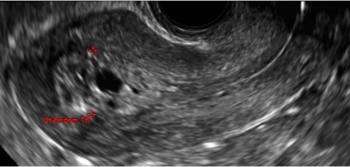

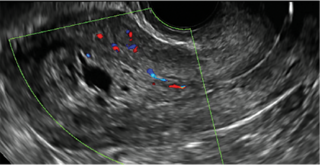

FIGURE 4 Cesarean scar defect with 1 previous cesarean delivery | ||||

| ||||

| Unenhanced sonogram in a 41-year-old patient. Myometrial notch is seen at both the endometrial surface and the serosal surface. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Unenhanced sonogram (A) and sonohysterogram (B) in a 40-year-old patient. |

In patients with postablation tubal sterilization syndrome, imaging can reveal loculated endometrial fluid collections, hyperechoic foci/scarring, and a poorly defined endomyometrial interface. See ADDITIONAL CASES-Postablation at the bottom of this article for additional imaging case presentations.

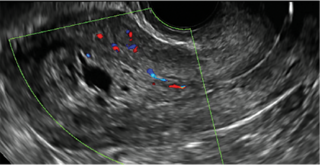

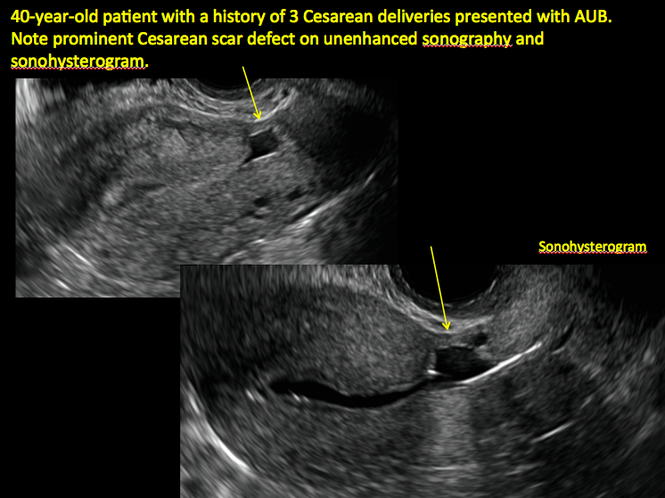

Cesarean scar defect on imaging

In 1961, Poidevin first described the lower uterine segment myometrial notch or “niche,” now known as cesarean scar defect, as a wedge-shaped defect in the myometrium of women who had undergone cesarean delivery. He noted that it appeared after a 6-month healing period.5

Using sonography with Doppler to view the defect, it appears relatively avascular and may decrease in size over time (FIGURES 4 and 5). Studies now are focusing on sonographic measurement of the cesarean scar defect as a clinical predictor of outcome for future pregnancies, as uterine rupture and abnormal placentation, including cesarean scar ectopics, can be associated with it.6-8

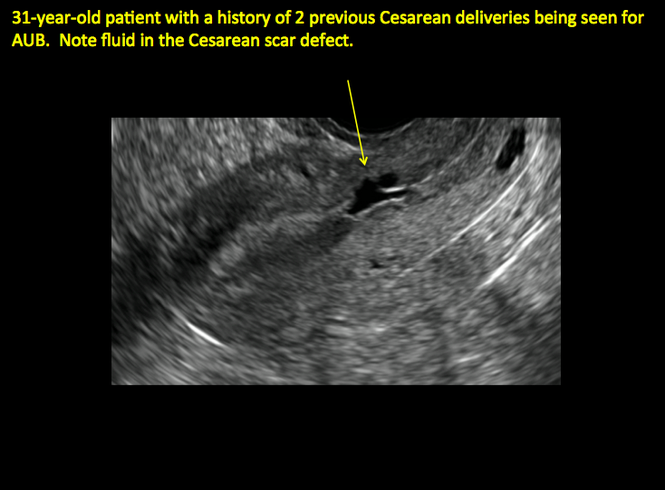

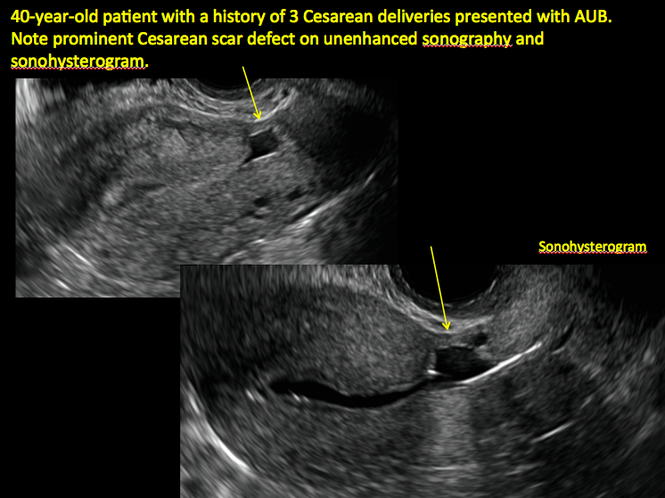

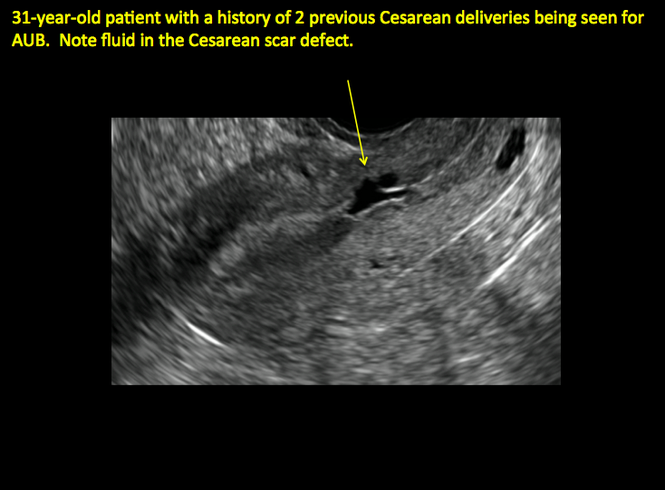

See ADDITIONAL CASES-Cesarean scar defect at the bottom of this article for 2 imaging case presentations.

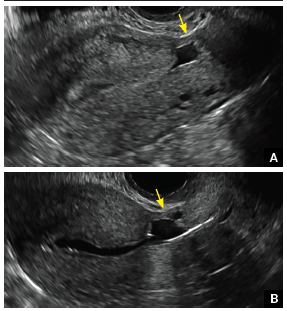

Endometrial changes with tamoxifen use

Tamoxifen use causes changes in the endometrium that on sonography can appear concerning for endometrial cancer. These changes include endometrial thickening and hyperechogenicity as well as cystic and heterogenous areas.9

Despite this imaging presentation, endometrial changes on sonography in the setting of tamoxifen use have been shown to be a poor predictor of actual endometrial pathology. In a study by Gerber and colleagues, the endometrial thickness in patients taking tamoxifen increased from a mean of 3.5 mm pretreatment to a mean of 9.2 mm after 3-year treatment.9 Using a cutoff value of 10 mm for abnormal endometrial thickness, screening transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) resulted in a high false-positive rate and iatrogenic morbidity. Endometrial cancer was detected in only 0.4% of patients (1 case), atrophy in 73%, polyps in 4%, and hyperplasia in 2%.9

Thus, routine screening sonographic assessment of the endometrium in asymptomatic women taking tamoxifen is not recommended. For women presenting with abnormal bleeding or other concerns, however, TVUS is appropriate (CASES 1 and 2).

| CASE 1 Endometrial polyps identified with tamoxifen use | ||||

| A 56-year-old patient with a history of breast cancer presently taking tamoxifen presented with postmenopausal bleeding. Endometrial biopsy results revealed endometrial polyps. | ||||

|  |  | ||

| CASE 2 Benign endometrial changes with tamoxifen use | ||||

| A 50-year-old patient with a history of breast cancer currently taking tamoxifen presented with abnormal uterine bleeding. Endometrial biopsy results indicated benign endometrial changes. | ||||

|  |  | ||

ADDITIONAL CASES - Postablation

ADDITIONAL CASES - Cesarean scar defect

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Engelbrechtsen L, Langhoff-Roos J, Kjer JJ, Istre O. Placenta accreta: adherent placenta due to Asherman syndrome. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3(3):175−178.

- Conforti A, Alviggi C, Mollo A, De Placido G, Magos A. The management of Asherman syndrome: a review of literature. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:118.

- Song D, Xia E, Xiao Y, Li TC, Huang X, Liu Y. Management of false passage created during hysteroscopic adhesiolysis for Asherman’s syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36(1):87−92.

- Lethaby A, Hickey M, Garry R, Penninx J. Endometrial resection/ablation techniques for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD001501.

- Poidevin LO. The value of hysterography in the prediction of cesarean section wound defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;81:67−71.

- Naji O, Abdallah Y, Bij De Vaate AJ, et al. Standardized approach for imaging and measuring Cesarean section scars using ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39(3):252−259.

- Kok N, Wiersma IC, Opmeer BC, et al. Sonographic measurement of lower uterine segment thickness to predict uterine rupture during a trial of labor in women with previous Cesarean section: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(2):132−139.

- Nezhat C, Grace L, Soliemannjad R, Razavi GM, Nezhat A. Cesarean scar defect: What is it and how should it be treated? OBG Manag. 2016;28(4):32, 34, 36, 38–39, 53.

- Gerber B, Krause A, Müller H, et al. Effects of adjuvant tamoxifen on the endometrium in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: a prospective long-term study using transvaginal ultrasound. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18(20):3464–3667.

Transvaginal ultrasound: We are gaining a better understanding of its clinical applications

Steven R. Goldstein, MD

In my first book I coined the phrase "sonomicroscopy." We are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) that you could not see with your naked eye even if you could it hold it at arms length and squint at it. For instance, cardiac activity can be seen easily within an embryo of 4 mm at 47 days since the last menstrual period. If there were any possible way to hold this 4-mm embryo in your hand, you would not appreciate cardiac pulsations contained within it! This is one of the beauties, and yet potential foibles, of TVUS.

In this excellent pictorial article, Michelle Stalnaker Ozcan, MD, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, have done an outstanding job of turning this low-power "sonomicroscope" into the uterus to better understand a number of unique yet important clinical applications of TVUS.

Tamoxifen is known to cause a slight but statistically significant increase in endometrial cancer. In 1994, I first described an unusual ultrasound appearance in the uterus of patients receiving tamoxifen, which was being misinterpreted as "endometrial thickening," and resulted in many unnecessary biopsies and dilation and curettage procedures.1 This type of uterine change has been seen in other selective estrogen-receptor modulators as well.2,3 In this article, Drs. Ozcan and Kaunitz correctly point out that such an ultrasound pattern does not necessitate any intervention in the absence of bleeding.

Another common question I am often asked is, "How do we handle the patient whose status is post-endometrial ablation and presents with staining?" The scarring shown in the figures that follow make any kind of meaningful evaluation extremely difficult.