User login

Postcesarean SSI rate declines with care bundle*

DALLAS – A surgical site infection care bundle reduced the rate of surgical site infections (SSIs) after cesarean delivery by more than half, according to a case-control study examining data from more than 2,000 patients.

At the health center where the SSI bundle was implemented, rates per 1,000 women undergoing cesarean delivery fell from 2.44 to 1.10 (P = .013).

The study showed the effectiveness of implementing evidence-based and -supported recommendations, and of having standardized protocols with little variation, said Christina Davidson, MD, presenting the pre-post findings during a plenary session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The bundle of interventions was developed over the course of 3 months in late 2013 and early 2014 by a multidisciplinary task force, drawing from colorectal surgery literature about SSI prevention. Both nurses and physicians were on the task force, and representatives came from the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, anesthesia, and infection prevention, said Dr. Davidson of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. All inpatient and outpatient clinical care sites had representation.

After the bundle elements were identified, a full month was devoted to education and team training, with full bundle implementation occurring in April 2014. “Visual aids were placed in close proximity to the operating rooms,” said Dr. Davidson. For example, antimicrobial prophylaxis cards were placed on all anesthetic carts.

“A surgical checklist was placed in the chart for each patient undergoing cesarean delivery and compliance was tracked for the first 12 months of implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. Additionally, members of the care team received feedback in the form of quarterly reports on SSI rates and statistics about bundle compliance.

Care bundle elements included a set of instructions for pre- and postoperative antiseptic skin cleaning, wound care, and glycemic control in patients. Women were given chlorhexidine cleanser and asked to use it when showering the day before and the morning of surgery for planned deliveries. Forced warm-air blankets maintained patient normothermia in the preoperative holding area.

A group of intraoperative interventions included use of antiseptic skin and vaginal preparations, double-gloving, and having all scrubbed members of the surgical team change their outer gloves for fascial closure. A new instrument tray also was used for fascial closure. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and doses were readministered based on the length of the procedure.

Postoperatively, said Dr. Davidson, “a set of insulin orders within the electronic medical record [was] used to maintain euglycemia in all diabetic patients.”

After the surgical dressing was removed on the 2nd postoperative day, patients were given a handout and education about wound control and infection prevention.

Finally, all patients received postdischarge follow-up calls from nurses within 72 hours after discharge.

Patient characteristics generally were similar before (n = 1,085) and after (n = 1,261) SSI bundle implementation. Body mass index was slightly higher in the postbundle group, and women in this group also were less likely to have had a prior cesarean delivery. There were no significant differences in age, gravidity, ethnicity, or race.

The study showed that with continued tracking, data-sharing, and reeducation efforts, “The SSI rate was sustained after bundle implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. The implementation team, working with hospital departments, was able to achieve a high compliance rate. And, she said, the effect size of the intervention was large enough to show significant reduction from an already low SSI rate.

However, Dr. Davidson also noted some limitations: All of the bundle elements were implemented simultaneously, so it wasn’t possible to tell which components had the greatest effect. Also, not all demographic data were available, and the type of SSI was sometimes unavailable from the deidentified data repository used for analysis, she said. “We weren’t able to tease out individual patient-level characteristics” about the timing and type of SSI in a patient-by-patient fashion, she said during discussion following her presentation.

All in all, she said, the bundle’s effectiveness “supports the synergistic effects of multiple strategies and the impact of a multidisciplinary team approach.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Davidson C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S46.

Correction, 3/5/18: An earlier version of this article omitted the word "rate" from the headline and Vitals section.

DALLAS – A surgical site infection care bundle reduced the rate of surgical site infections (SSIs) after cesarean delivery by more than half, according to a case-control study examining data from more than 2,000 patients.

At the health center where the SSI bundle was implemented, rates per 1,000 women undergoing cesarean delivery fell from 2.44 to 1.10 (P = .013).

The study showed the effectiveness of implementing evidence-based and -supported recommendations, and of having standardized protocols with little variation, said Christina Davidson, MD, presenting the pre-post findings during a plenary session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The bundle of interventions was developed over the course of 3 months in late 2013 and early 2014 by a multidisciplinary task force, drawing from colorectal surgery literature about SSI prevention. Both nurses and physicians were on the task force, and representatives came from the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, anesthesia, and infection prevention, said Dr. Davidson of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. All inpatient and outpatient clinical care sites had representation.

After the bundle elements were identified, a full month was devoted to education and team training, with full bundle implementation occurring in April 2014. “Visual aids were placed in close proximity to the operating rooms,” said Dr. Davidson. For example, antimicrobial prophylaxis cards were placed on all anesthetic carts.

“A surgical checklist was placed in the chart for each patient undergoing cesarean delivery and compliance was tracked for the first 12 months of implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. Additionally, members of the care team received feedback in the form of quarterly reports on SSI rates and statistics about bundle compliance.

Care bundle elements included a set of instructions for pre- and postoperative antiseptic skin cleaning, wound care, and glycemic control in patients. Women were given chlorhexidine cleanser and asked to use it when showering the day before and the morning of surgery for planned deliveries. Forced warm-air blankets maintained patient normothermia in the preoperative holding area.

A group of intraoperative interventions included use of antiseptic skin and vaginal preparations, double-gloving, and having all scrubbed members of the surgical team change their outer gloves for fascial closure. A new instrument tray also was used for fascial closure. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and doses were readministered based on the length of the procedure.

Postoperatively, said Dr. Davidson, “a set of insulin orders within the electronic medical record [was] used to maintain euglycemia in all diabetic patients.”

After the surgical dressing was removed on the 2nd postoperative day, patients were given a handout and education about wound control and infection prevention.

Finally, all patients received postdischarge follow-up calls from nurses within 72 hours after discharge.

Patient characteristics generally were similar before (n = 1,085) and after (n = 1,261) SSI bundle implementation. Body mass index was slightly higher in the postbundle group, and women in this group also were less likely to have had a prior cesarean delivery. There were no significant differences in age, gravidity, ethnicity, or race.

The study showed that with continued tracking, data-sharing, and reeducation efforts, “The SSI rate was sustained after bundle implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. The implementation team, working with hospital departments, was able to achieve a high compliance rate. And, she said, the effect size of the intervention was large enough to show significant reduction from an already low SSI rate.

However, Dr. Davidson also noted some limitations: All of the bundle elements were implemented simultaneously, so it wasn’t possible to tell which components had the greatest effect. Also, not all demographic data were available, and the type of SSI was sometimes unavailable from the deidentified data repository used for analysis, she said. “We weren’t able to tease out individual patient-level characteristics” about the timing and type of SSI in a patient-by-patient fashion, she said during discussion following her presentation.

All in all, she said, the bundle’s effectiveness “supports the synergistic effects of multiple strategies and the impact of a multidisciplinary team approach.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Davidson C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S46.

Correction, 3/5/18: An earlier version of this article omitted the word "rate" from the headline and Vitals section.

DALLAS – A surgical site infection care bundle reduced the rate of surgical site infections (SSIs) after cesarean delivery by more than half, according to a case-control study examining data from more than 2,000 patients.

At the health center where the SSI bundle was implemented, rates per 1,000 women undergoing cesarean delivery fell from 2.44 to 1.10 (P = .013).

The study showed the effectiveness of implementing evidence-based and -supported recommendations, and of having standardized protocols with little variation, said Christina Davidson, MD, presenting the pre-post findings during a plenary session at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The bundle of interventions was developed over the course of 3 months in late 2013 and early 2014 by a multidisciplinary task force, drawing from colorectal surgery literature about SSI prevention. Both nurses and physicians were on the task force, and representatives came from the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, anesthesia, and infection prevention, said Dr. Davidson of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. All inpatient and outpatient clinical care sites had representation.

After the bundle elements were identified, a full month was devoted to education and team training, with full bundle implementation occurring in April 2014. “Visual aids were placed in close proximity to the operating rooms,” said Dr. Davidson. For example, antimicrobial prophylaxis cards were placed on all anesthetic carts.

“A surgical checklist was placed in the chart for each patient undergoing cesarean delivery and compliance was tracked for the first 12 months of implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. Additionally, members of the care team received feedback in the form of quarterly reports on SSI rates and statistics about bundle compliance.

Care bundle elements included a set of instructions for pre- and postoperative antiseptic skin cleaning, wound care, and glycemic control in patients. Women were given chlorhexidine cleanser and asked to use it when showering the day before and the morning of surgery for planned deliveries. Forced warm-air blankets maintained patient normothermia in the preoperative holding area.

A group of intraoperative interventions included use of antiseptic skin and vaginal preparations, double-gloving, and having all scrubbed members of the surgical team change their outer gloves for fascial closure. A new instrument tray also was used for fascial closure. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered within 1 hour of skin incision, and doses were readministered based on the length of the procedure.

Postoperatively, said Dr. Davidson, “a set of insulin orders within the electronic medical record [was] used to maintain euglycemia in all diabetic patients.”

After the surgical dressing was removed on the 2nd postoperative day, patients were given a handout and education about wound control and infection prevention.

Finally, all patients received postdischarge follow-up calls from nurses within 72 hours after discharge.

Patient characteristics generally were similar before (n = 1,085) and after (n = 1,261) SSI bundle implementation. Body mass index was slightly higher in the postbundle group, and women in this group also were less likely to have had a prior cesarean delivery. There were no significant differences in age, gravidity, ethnicity, or race.

The study showed that with continued tracking, data-sharing, and reeducation efforts, “The SSI rate was sustained after bundle implementation,” said Dr. Davidson. The implementation team, working with hospital departments, was able to achieve a high compliance rate. And, she said, the effect size of the intervention was large enough to show significant reduction from an already low SSI rate.

However, Dr. Davidson also noted some limitations: All of the bundle elements were implemented simultaneously, so it wasn’t possible to tell which components had the greatest effect. Also, not all demographic data were available, and the type of SSI was sometimes unavailable from the deidentified data repository used for analysis, she said. “We weren’t able to tease out individual patient-level characteristics” about the timing and type of SSI in a patient-by-patient fashion, she said during discussion following her presentation.

All in all, she said, the bundle’s effectiveness “supports the synergistic effects of multiple strategies and the impact of a multidisciplinary team approach.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Davidson C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S46.

Correction, 3/5/18: An earlier version of this article omitted the word "rate" from the headline and Vitals section.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: The postcesarean surgical site infection rate dropped by more than half after a multicomponent care bundle was put in place.*

Major finding: SSIs patients went from 2.44 to 1.10/1,000 after the bundle was implemented (P = .013).

Study details: Case-control study of 1,085 women pre– and 1,261 women post–care bundle implementation.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Davidson C et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S46.

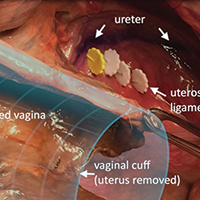

Surgical anatomy and steps of the uterosacral ligament colpopexy

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by

Video roundtable–Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Read the article: Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Read the article: Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

Read the article: Endometriosis: Expert perspectives on medical and surgical management

How to avoid and manage complications when placing ports and docking

No link found between OR skullcaps and infection

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Surgeons who choose to wear a skullcap in the OR can point to yet another study with evidence to bolster their preference.

Two major hospital and nursing credentialing organizations have recommended that hospitals ban skullcaps from the operating room as a practice to control surgical site infections, but a study of almost 2,000 operations at an academic medical center has found that strictly enforcing the ban had no impact on infection rates, according to results of a study presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The study, conducted at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, showed that rates of surgical site infections (SSIs) were almost identical in the year before and the year after the institution implemented the skullcap ban. “The overall surgical site infection rate was 5.4%, and there were no differences in surgical site infections before or after the headwear policy was adopted,” said Arturo J. Rios-Diaz, MD. The Joint Commission and the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses recommend against the use of skullcaps.

The study reviewed American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data on 1,901 patients who had 1,950 clean or clean-contaminated general surgery procedures in 2015, the year before the ban was implemented, and in 2016 (767 in 2015 and 1,183 in 2016). The most common procedures were colectomy (18.2%), pancreatectomy (13.5%), and ventral hernia repair (9.9%). The study excluded orthopedic and vascular operations and any cases with sepsis or an active infection at the time of surgery.

There were some differences between the pre- and postban patient groups. The preban group was younger (median age, 57.91 years vs. 59.75, P = .01) but had more patients who were obese, measured as body mass index above 30 kg/m2 (42.37% vs. 35.23%, P less than .01), and smokers (16.18% vs. 12.27%, P = .02). Wound classification also differed: clean, 38.55% before vs. 43.91% after; and clean-contaminated, 61.45% vs. 56.09% (P = .02). All other demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups.

“In multivariate logistic regression models controlling for these confounders, there was no association of the banning of skullcaps with decreased surgical site infection rates,” Dr. Rios-Diaz said.

“The adoption of guidelines targeted to optimize patient care should always be welcomed by surgeons,” he said. “However, if they’re going to be implemented on a national level, these policies must be based on higher levels of evidence, so further studies are warranted to assess the validity of the [Joint Commission] headwear guidelines.” According to Dr. Rios-Diaz, the recommendations from the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses are based on two case series from the 1960s and 1970s.

Thomas Jefferson University once again allows skullcaps in the OR, he said.

Dr. Rios-Diaz and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Rios-Diaz AJ et al. Annual Academic Surgical Congress. Abstract 09.11.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Surgeons who choose to wear a skullcap in the OR can point to yet another study with evidence to bolster their preference.

Two major hospital and nursing credentialing organizations have recommended that hospitals ban skullcaps from the operating room as a practice to control surgical site infections, but a study of almost 2,000 operations at an academic medical center has found that strictly enforcing the ban had no impact on infection rates, according to results of a study presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The study, conducted at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, showed that rates of surgical site infections (SSIs) were almost identical in the year before and the year after the institution implemented the skullcap ban. “The overall surgical site infection rate was 5.4%, and there were no differences in surgical site infections before or after the headwear policy was adopted,” said Arturo J. Rios-Diaz, MD. The Joint Commission and the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses recommend against the use of skullcaps.

The study reviewed American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data on 1,901 patients who had 1,950 clean or clean-contaminated general surgery procedures in 2015, the year before the ban was implemented, and in 2016 (767 in 2015 and 1,183 in 2016). The most common procedures were colectomy (18.2%), pancreatectomy (13.5%), and ventral hernia repair (9.9%). The study excluded orthopedic and vascular operations and any cases with sepsis or an active infection at the time of surgery.

There were some differences between the pre- and postban patient groups. The preban group was younger (median age, 57.91 years vs. 59.75, P = .01) but had more patients who were obese, measured as body mass index above 30 kg/m2 (42.37% vs. 35.23%, P less than .01), and smokers (16.18% vs. 12.27%, P = .02). Wound classification also differed: clean, 38.55% before vs. 43.91% after; and clean-contaminated, 61.45% vs. 56.09% (P = .02). All other demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups.

“In multivariate logistic regression models controlling for these confounders, there was no association of the banning of skullcaps with decreased surgical site infection rates,” Dr. Rios-Diaz said.

“The adoption of guidelines targeted to optimize patient care should always be welcomed by surgeons,” he said. “However, if they’re going to be implemented on a national level, these policies must be based on higher levels of evidence, so further studies are warranted to assess the validity of the [Joint Commission] headwear guidelines.” According to Dr. Rios-Diaz, the recommendations from the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses are based on two case series from the 1960s and 1970s.

Thomas Jefferson University once again allows skullcaps in the OR, he said.

Dr. Rios-Diaz and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Rios-Diaz AJ et al. Annual Academic Surgical Congress. Abstract 09.11.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Surgeons who choose to wear a skullcap in the OR can point to yet another study with evidence to bolster their preference.

Two major hospital and nursing credentialing organizations have recommended that hospitals ban skullcaps from the operating room as a practice to control surgical site infections, but a study of almost 2,000 operations at an academic medical center has found that strictly enforcing the ban had no impact on infection rates, according to results of a study presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

The study, conducted at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, showed that rates of surgical site infections (SSIs) were almost identical in the year before and the year after the institution implemented the skullcap ban. “The overall surgical site infection rate was 5.4%, and there were no differences in surgical site infections before or after the headwear policy was adopted,” said Arturo J. Rios-Diaz, MD. The Joint Commission and the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses recommend against the use of skullcaps.

The study reviewed American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data on 1,901 patients who had 1,950 clean or clean-contaminated general surgery procedures in 2015, the year before the ban was implemented, and in 2016 (767 in 2015 and 1,183 in 2016). The most common procedures were colectomy (18.2%), pancreatectomy (13.5%), and ventral hernia repair (9.9%). The study excluded orthopedic and vascular operations and any cases with sepsis or an active infection at the time of surgery.

There were some differences between the pre- and postban patient groups. The preban group was younger (median age, 57.91 years vs. 59.75, P = .01) but had more patients who were obese, measured as body mass index above 30 kg/m2 (42.37% vs. 35.23%, P less than .01), and smokers (16.18% vs. 12.27%, P = .02). Wound classification also differed: clean, 38.55% before vs. 43.91% after; and clean-contaminated, 61.45% vs. 56.09% (P = .02). All other demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups.

“In multivariate logistic regression models controlling for these confounders, there was no association of the banning of skullcaps with decreased surgical site infection rates,” Dr. Rios-Diaz said.

“The adoption of guidelines targeted to optimize patient care should always be welcomed by surgeons,” he said. “However, if they’re going to be implemented on a national level, these policies must be based on higher levels of evidence, so further studies are warranted to assess the validity of the [Joint Commission] headwear guidelines.” According to Dr. Rios-Diaz, the recommendations from the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses are based on two case series from the 1960s and 1970s.

Thomas Jefferson University once again allows skullcaps in the OR, he said.

Dr. Rios-Diaz and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Rios-Diaz AJ et al. Annual Academic Surgical Congress. Abstract 09.11.

REPORTING FROM THE ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Findings of this study do not support the ban on surgical skullcaps.

Major finding: No association was found between the skullcap ban and decreased surgical site infection.

Study details: Analysis of ACS NSQIP data on 1,950 surgical cases from before and after the skullcap ban.

Disclosures: The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Rios-Diaz AJ et al. Annual Academic Surgical Congress. Abstract 09.11.

An intervention to track fetal movement attempts to prevent stillbirth

DALLAS – A hospital-wide intervention designed to prevent stillbirth by focusing on reduced fetal movement failed to do so – but did result in significant increases in labor induction and cesarean sections.

After the interventions was implemented, hospitals achieved a stillbirth rate of 4 per 1,000 – not significantly different than the 4.4 per 1,000 rate in the controls, Jane Norman, MD, reported at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. On the other hand, the risk of a C-section increased by 9% and the risk of a labor induction by 8%, said Prof. Norman of the University of Edinburgh.

The results are disappointing, but consistent with most of the literature on this topic, she said.

“There is very good evidence that, if you ask women to count kicks, it doesn’t prevent stillbirth,” said Dr. Norman, referring to a 2015 Cochrane review. That paper, which examined five studies comprising more than 71,000 women, found that rates of stillbirth were similar between those who employed kick counts and those who did not.

Still, said Dr. Norman, there is evidence that stillbirth often is preceded by a period of reduced fetal movement. And a 2009 quality improvement project conducted in Oslo has driven enthusiasm for the idea of implementing some form of maternal and provider awareness of this area of obstetric care.

Stillbirth rates fell about 2% after the participating hospitals provided written information to women about fetal activity and reduced fetal movement, including an invitation to monitor fetal movements and formalized clinical guidelines for management of reduced fetal movement.

“There is a huge interest in the United Kingdom right now in using reduced fetal movement as an alert to act on to prevent stillbirth,” Dr. Norman said. “The National Health Service has recommended that we talk with women and clinicians about reduced fetal movement,” and try to incorporate it into clinical care.

Dr. Norman and her team wanted to emulate the Oslo experience, with a target of a 30% reduction in stillbirth rate.

The AFFIRM trial employed a clinical management guideline and patient education handout to raise awareness of reduced fetal movement as a trigger to investigate fetal well-being. The study used hospital records from 37 institutions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, which sequentially implemented the package. Hospitals were grouped into eight clusters. The trial began in January 2014. The first cluster began the intervention in mid-March; a new cluster came online every 3 months thereafter, until April 2016. Each cluster used its own baseline data as control.

The leaflet educated women about what fetal movements should feel like in all stages of pregnancy and what to expect from normal fetal movement. It encouraged them to report any lessening or cessation of fetal movement to their health care provider without delay.

The clinical guideline was matched to different gestational stages, but generally advocated cardiotocography and scans to estimate amniotic fluid volume and fetal size in cases of reduced movement with a low threshold for early delivery if there were abnormal findings at 37 weeks or later.

The final sample comprised 385,582 births, with 157,692 in the control period and 227,860 in the intervention period. The mean age of women was 30 years; 50% were white, 50% were overweight or obese, and 15% smoked. About 40% were nulliparous.

In the control arm, there were 691 stillbirths at 24 weeks’ gestational age or older (4.4/1,000). In the intervention arm, there were 921 events (4.06/1,000). The 10% risk reduction was not statistically significant.

The investigators also examined stillbirths occurring at 22 weeks or older, 28 weeks or older, and 37 weeks or older. Again, there were no significant between-group differences. Nor was there a difference in the perinatal mortality rate (0.68% vs. 0.62%).

There were, however, differences in interventions. The risk of a C-section increased by 5% (25.5% vs. 28.5%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.05), and the risk of induction by 9% (33.6% vs. 39.8%; AOR, 1.09). Most of the induction risk was driven by an 11% increase in induction risk at 39 weeks or older. The team also found a 5% increase in the chance of an elective delivery at 39 weeks or older (45.2% vs. 52.4%; AOR, 1.05)

There was a corresponding significant 10% decrease in the chance of spontaneous vaginal delivery (59.8% vs. 57.4%; AOR, 0.90).

Although there was no overall increase in the risk of a neonatal ICU admission, there was a significant 12% increase in the risk of a neonatal ICU admission of at least 48 hours (6.2% vs. 6.7%; AOR, 1.12). There were no other significant differences in neonatal outcomes (gestational age, size at birth, preterm delivery).

“We also looked at the potential impact if we implemented this intervention on a population of 10,000 pregnancies,” Dr. Norman said. “We would have 5 fewer stillbirths – but potentially anywhere from 11 fewer to 3 more. However, we would have 162 more cesarean deliveries and 108 more inductions.”

The AFFIRM trial was sponsored by the University of Edinburgh and the National Health Service. Dr. Norman had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Norman JE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218,S603.

DALLAS – A hospital-wide intervention designed to prevent stillbirth by focusing on reduced fetal movement failed to do so – but did result in significant increases in labor induction and cesarean sections.

After the interventions was implemented, hospitals achieved a stillbirth rate of 4 per 1,000 – not significantly different than the 4.4 per 1,000 rate in the controls, Jane Norman, MD, reported at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. On the other hand, the risk of a C-section increased by 9% and the risk of a labor induction by 8%, said Prof. Norman of the University of Edinburgh.

The results are disappointing, but consistent with most of the literature on this topic, she said.

“There is very good evidence that, if you ask women to count kicks, it doesn’t prevent stillbirth,” said Dr. Norman, referring to a 2015 Cochrane review. That paper, which examined five studies comprising more than 71,000 women, found that rates of stillbirth were similar between those who employed kick counts and those who did not.

Still, said Dr. Norman, there is evidence that stillbirth often is preceded by a period of reduced fetal movement. And a 2009 quality improvement project conducted in Oslo has driven enthusiasm for the idea of implementing some form of maternal and provider awareness of this area of obstetric care.

Stillbirth rates fell about 2% after the participating hospitals provided written information to women about fetal activity and reduced fetal movement, including an invitation to monitor fetal movements and formalized clinical guidelines for management of reduced fetal movement.

“There is a huge interest in the United Kingdom right now in using reduced fetal movement as an alert to act on to prevent stillbirth,” Dr. Norman said. “The National Health Service has recommended that we talk with women and clinicians about reduced fetal movement,” and try to incorporate it into clinical care.

Dr. Norman and her team wanted to emulate the Oslo experience, with a target of a 30% reduction in stillbirth rate.

The AFFIRM trial employed a clinical management guideline and patient education handout to raise awareness of reduced fetal movement as a trigger to investigate fetal well-being. The study used hospital records from 37 institutions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, which sequentially implemented the package. Hospitals were grouped into eight clusters. The trial began in January 2014. The first cluster began the intervention in mid-March; a new cluster came online every 3 months thereafter, until April 2016. Each cluster used its own baseline data as control.

The leaflet educated women about what fetal movements should feel like in all stages of pregnancy and what to expect from normal fetal movement. It encouraged them to report any lessening or cessation of fetal movement to their health care provider without delay.

The clinical guideline was matched to different gestational stages, but generally advocated cardiotocography and scans to estimate amniotic fluid volume and fetal size in cases of reduced movement with a low threshold for early delivery if there were abnormal findings at 37 weeks or later.

The final sample comprised 385,582 births, with 157,692 in the control period and 227,860 in the intervention period. The mean age of women was 30 years; 50% were white, 50% were overweight or obese, and 15% smoked. About 40% were nulliparous.

In the control arm, there were 691 stillbirths at 24 weeks’ gestational age or older (4.4/1,000). In the intervention arm, there were 921 events (4.06/1,000). The 10% risk reduction was not statistically significant.

The investigators also examined stillbirths occurring at 22 weeks or older, 28 weeks or older, and 37 weeks or older. Again, there were no significant between-group differences. Nor was there a difference in the perinatal mortality rate (0.68% vs. 0.62%).

There were, however, differences in interventions. The risk of a C-section increased by 5% (25.5% vs. 28.5%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.05), and the risk of induction by 9% (33.6% vs. 39.8%; AOR, 1.09). Most of the induction risk was driven by an 11% increase in induction risk at 39 weeks or older. The team also found a 5% increase in the chance of an elective delivery at 39 weeks or older (45.2% vs. 52.4%; AOR, 1.05)

There was a corresponding significant 10% decrease in the chance of spontaneous vaginal delivery (59.8% vs. 57.4%; AOR, 0.90).

Although there was no overall increase in the risk of a neonatal ICU admission, there was a significant 12% increase in the risk of a neonatal ICU admission of at least 48 hours (6.2% vs. 6.7%; AOR, 1.12). There were no other significant differences in neonatal outcomes (gestational age, size at birth, preterm delivery).

“We also looked at the potential impact if we implemented this intervention on a population of 10,000 pregnancies,” Dr. Norman said. “We would have 5 fewer stillbirths – but potentially anywhere from 11 fewer to 3 more. However, we would have 162 more cesarean deliveries and 108 more inductions.”

The AFFIRM trial was sponsored by the University of Edinburgh and the National Health Service. Dr. Norman had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Norman JE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218,S603.

DALLAS – A hospital-wide intervention designed to prevent stillbirth by focusing on reduced fetal movement failed to do so – but did result in significant increases in labor induction and cesarean sections.

After the interventions was implemented, hospitals achieved a stillbirth rate of 4 per 1,000 – not significantly different than the 4.4 per 1,000 rate in the controls, Jane Norman, MD, reported at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. On the other hand, the risk of a C-section increased by 9% and the risk of a labor induction by 8%, said Prof. Norman of the University of Edinburgh.

The results are disappointing, but consistent with most of the literature on this topic, she said.

“There is very good evidence that, if you ask women to count kicks, it doesn’t prevent stillbirth,” said Dr. Norman, referring to a 2015 Cochrane review. That paper, which examined five studies comprising more than 71,000 women, found that rates of stillbirth were similar between those who employed kick counts and those who did not.

Still, said Dr. Norman, there is evidence that stillbirth often is preceded by a period of reduced fetal movement. And a 2009 quality improvement project conducted in Oslo has driven enthusiasm for the idea of implementing some form of maternal and provider awareness of this area of obstetric care.

Stillbirth rates fell about 2% after the participating hospitals provided written information to women about fetal activity and reduced fetal movement, including an invitation to monitor fetal movements and formalized clinical guidelines for management of reduced fetal movement.

“There is a huge interest in the United Kingdom right now in using reduced fetal movement as an alert to act on to prevent stillbirth,” Dr. Norman said. “The National Health Service has recommended that we talk with women and clinicians about reduced fetal movement,” and try to incorporate it into clinical care.

Dr. Norman and her team wanted to emulate the Oslo experience, with a target of a 30% reduction in stillbirth rate.

The AFFIRM trial employed a clinical management guideline and patient education handout to raise awareness of reduced fetal movement as a trigger to investigate fetal well-being. The study used hospital records from 37 institutions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, which sequentially implemented the package. Hospitals were grouped into eight clusters. The trial began in January 2014. The first cluster began the intervention in mid-March; a new cluster came online every 3 months thereafter, until April 2016. Each cluster used its own baseline data as control.

The leaflet educated women about what fetal movements should feel like in all stages of pregnancy and what to expect from normal fetal movement. It encouraged them to report any lessening or cessation of fetal movement to their health care provider without delay.

The clinical guideline was matched to different gestational stages, but generally advocated cardiotocography and scans to estimate amniotic fluid volume and fetal size in cases of reduced movement with a low threshold for early delivery if there were abnormal findings at 37 weeks or later.

The final sample comprised 385,582 births, with 157,692 in the control period and 227,860 in the intervention period. The mean age of women was 30 years; 50% were white, 50% were overweight or obese, and 15% smoked. About 40% were nulliparous.

In the control arm, there were 691 stillbirths at 24 weeks’ gestational age or older (4.4/1,000). In the intervention arm, there were 921 events (4.06/1,000). The 10% risk reduction was not statistically significant.

The investigators also examined stillbirths occurring at 22 weeks or older, 28 weeks or older, and 37 weeks or older. Again, there were no significant between-group differences. Nor was there a difference in the perinatal mortality rate (0.68% vs. 0.62%).

There were, however, differences in interventions. The risk of a C-section increased by 5% (25.5% vs. 28.5%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.05), and the risk of induction by 9% (33.6% vs. 39.8%; AOR, 1.09). Most of the induction risk was driven by an 11% increase in induction risk at 39 weeks or older. The team also found a 5% increase in the chance of an elective delivery at 39 weeks or older (45.2% vs. 52.4%; AOR, 1.05)

There was a corresponding significant 10% decrease in the chance of spontaneous vaginal delivery (59.8% vs. 57.4%; AOR, 0.90).

Although there was no overall increase in the risk of a neonatal ICU admission, there was a significant 12% increase in the risk of a neonatal ICU admission of at least 48 hours (6.2% vs. 6.7%; AOR, 1.12). There were no other significant differences in neonatal outcomes (gestational age, size at birth, preterm delivery).

“We also looked at the potential impact if we implemented this intervention on a population of 10,000 pregnancies,” Dr. Norman said. “We would have 5 fewer stillbirths – but potentially anywhere from 11 fewer to 3 more. However, we would have 162 more cesarean deliveries and 108 more inductions.”

The AFFIRM trial was sponsored by the University of Edinburgh and the National Health Service. Dr. Norman had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Norman JE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218,S603.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Reduced fetal movements as an alert for investigation didn’t reduce stillbirth rates.

Major finding: Hospitals achieved a stillbirth rate of 4/1,000 – not significantly different than the 4.4/1,000 rate before the intervention.

Study details: The randomized, cluster trial comprised 37 hospitals in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Disclosures: The University of Edinburgh and the National Health Service sponsored the trial. Dr. Norman had no financial disclosures.

Source: Norman JE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218,S603.

Endometriosis surgery on a young woman: $483,351 award

Endometriosis surgery on a young woman: $483,351 award

A 17-year-old woman reported cramping and heavy bleeding during her menses. Her gynecologist suspected that the patient had endometriosis and recommended laparoscopic surgery with cauterization.

During surgery, the gynecologist found 2 metal staples in the patient’s pelvic region from a prior appendectomy. He continued with the surgery as planned, using monopolar cauterization to excise the endometriosis.

The following day, the patient sought emergency treatment for pain. Physicians discovered 2 perforations in her anterior rectum and performed an emergency colectomy. She spent 18 days in the hospital. When the colectomy was reversed 3 months later, she was hospitalized for 8 days and later developed a postoperative surgical site infection requiring IV antibiotics and weeks of wound care.

The patient was in the middle of her senior year of high school when she had the colectomy and could not return to normal activities. She was unable to graduate with her class and had to relinquish a college scholarship. As a result, she completed her senior year via homeschooling and graduated a year later.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The gynecologist’s negligent use of the cautery device within millimeters of the staples caused the bowel injury and necessitated the colectomy. The electric current from the cautery device heated the staples, injuring the rectum, which became necrotic. While she had no long-term physical limitations, wearing the colostomy bag, missing her senior year, not being able to graduate with her class, and not being able to participate in typical senior year activities left her emotionally distressed.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The staples were not found near the rectal injury. The injury was a known complication of cauterization, not a result of negligence.

VERDICT: A $588,351 California verdict was returned but was reduced to $483,351 because of the state cap on pain and suffering.

RELATED

Surgical excision of the most severe form of endometriosis

Sigmoid colon injury during hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman had uterine fibroids that caused such heavy bleeding that she became anemic and required a transfusion. On June 26, she underwent laparoscopic-assisted supracervical hysterectomy performed by her primary ObGyn and an assisting ObGyn.

The next day, the patient developed pain and fever and her vital signs were unstable. The primary ObGyn called in a general surgeon. A CT scan showed a tear on the underside of the sigmoid colon. The general surgeon performed a laparotomy, resected the colon, and created a temporary colostomy. The colostomy reversal took place on September 25.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient sued both ObGyns, alleging that they should have found the colon injury during surgery. The primary ObGyn settled before trial and the case continued against the assisting ObGyn. It was undisputed that one or both of the physicians caused the tear, but that was not the patient’s claim. The patient alleged that negligence occurred when the injury was not intraoperatively detected. Had the injury been found during surgery, a general surgeon could have performed a primary repair, saving the patient from further surgery and colostomy. The patient claimed mental anguish and embarrassment from the colostomy. Her abdomen is still tender and she has significant scarring.

PHYSICIAN'S CLAIM: There was no negligence. Nothing was unusual about the nature of the procedure, and nothing unusual was seen intraoperatively that would have led them to search for an injury. They performed adequate and appropriate exploration before closing. The linear tear on the underside of the sigmoid colon was very inconspicuous in size, shape, and location, and was away from the operative area. The injury likely occurred during manipulation of the sigmoid colon, which generally has to be retracted before the uterus can be removed. Even if the injury had been found intraoperatively, a general surgeon would have had to convert to laparoscopy to repair the colon.

VERDICT: After a settlement was reached with the primary gynecologist, a Texas defense verdict was returned for the assisting gynecologist.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endometriosis surgery on a young woman: $483,351 award

A 17-year-old woman reported cramping and heavy bleeding during her menses. Her gynecologist suspected that the patient had endometriosis and recommended laparoscopic surgery with cauterization.

During surgery, the gynecologist found 2 metal staples in the patient’s pelvic region from a prior appendectomy. He continued with the surgery as planned, using monopolar cauterization to excise the endometriosis.

The following day, the patient sought emergency treatment for pain. Physicians discovered 2 perforations in her anterior rectum and performed an emergency colectomy. She spent 18 days in the hospital. When the colectomy was reversed 3 months later, she was hospitalized for 8 days and later developed a postoperative surgical site infection requiring IV antibiotics and weeks of wound care.

The patient was in the middle of her senior year of high school when she had the colectomy and could not return to normal activities. She was unable to graduate with her class and had to relinquish a college scholarship. As a result, she completed her senior year via homeschooling and graduated a year later.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The gynecologist’s negligent use of the cautery device within millimeters of the staples caused the bowel injury and necessitated the colectomy. The electric current from the cautery device heated the staples, injuring the rectum, which became necrotic. While she had no long-term physical limitations, wearing the colostomy bag, missing her senior year, not being able to graduate with her class, and not being able to participate in typical senior year activities left her emotionally distressed.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The staples were not found near the rectal injury. The injury was a known complication of cauterization, not a result of negligence.

VERDICT: A $588,351 California verdict was returned but was reduced to $483,351 because of the state cap on pain and suffering.

RELATED

Surgical excision of the most severe form of endometriosis

Sigmoid colon injury during hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman had uterine fibroids that caused such heavy bleeding that she became anemic and required a transfusion. On June 26, she underwent laparoscopic-assisted supracervical hysterectomy performed by her primary ObGyn and an assisting ObGyn.

The next day, the patient developed pain and fever and her vital signs were unstable. The primary ObGyn called in a general surgeon. A CT scan showed a tear on the underside of the sigmoid colon. The general surgeon performed a laparotomy, resected the colon, and created a temporary colostomy. The colostomy reversal took place on September 25.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient sued both ObGyns, alleging that they should have found the colon injury during surgery. The primary ObGyn settled before trial and the case continued against the assisting ObGyn. It was undisputed that one or both of the physicians caused the tear, but that was not the patient’s claim. The patient alleged that negligence occurred when the injury was not intraoperatively detected. Had the injury been found during surgery, a general surgeon could have performed a primary repair, saving the patient from further surgery and colostomy. The patient claimed mental anguish and embarrassment from the colostomy. Her abdomen is still tender and she has significant scarring.

PHYSICIAN'S CLAIM: There was no negligence. Nothing was unusual about the nature of the procedure, and nothing unusual was seen intraoperatively that would have led them to search for an injury. They performed adequate and appropriate exploration before closing. The linear tear on the underside of the sigmoid colon was very inconspicuous in size, shape, and location, and was away from the operative area. The injury likely occurred during manipulation of the sigmoid colon, which generally has to be retracted before the uterus can be removed. Even if the injury had been found intraoperatively, a general surgeon would have had to convert to laparoscopy to repair the colon.

VERDICT: After a settlement was reached with the primary gynecologist, a Texas defense verdict was returned for the assisting gynecologist.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endometriosis surgery on a young woman: $483,351 award

A 17-year-old woman reported cramping and heavy bleeding during her menses. Her gynecologist suspected that the patient had endometriosis and recommended laparoscopic surgery with cauterization.

During surgery, the gynecologist found 2 metal staples in the patient’s pelvic region from a prior appendectomy. He continued with the surgery as planned, using monopolar cauterization to excise the endometriosis.

The following day, the patient sought emergency treatment for pain. Physicians discovered 2 perforations in her anterior rectum and performed an emergency colectomy. She spent 18 days in the hospital. When the colectomy was reversed 3 months later, she was hospitalized for 8 days and later developed a postoperative surgical site infection requiring IV antibiotics and weeks of wound care.

The patient was in the middle of her senior year of high school when she had the colectomy and could not return to normal activities. She was unable to graduate with her class and had to relinquish a college scholarship. As a result, she completed her senior year via homeschooling and graduated a year later.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The gynecologist’s negligent use of the cautery device within millimeters of the staples caused the bowel injury and necessitated the colectomy. The electric current from the cautery device heated the staples, injuring the rectum, which became necrotic. While she had no long-term physical limitations, wearing the colostomy bag, missing her senior year, not being able to graduate with her class, and not being able to participate in typical senior year activities left her emotionally distressed.

PHYSICIAN'S DEFENSE: The staples were not found near the rectal injury. The injury was a known complication of cauterization, not a result of negligence.

VERDICT: A $588,351 California verdict was returned but was reduced to $483,351 because of the state cap on pain and suffering.

RELATED

Surgical excision of the most severe form of endometriosis

Sigmoid colon injury during hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman had uterine fibroids that caused such heavy bleeding that she became anemic and required a transfusion. On June 26, she underwent laparoscopic-assisted supracervical hysterectomy performed by her primary ObGyn and an assisting ObGyn.

The next day, the patient developed pain and fever and her vital signs were unstable. The primary ObGyn called in a general surgeon. A CT scan showed a tear on the underside of the sigmoid colon. The general surgeon performed a laparotomy, resected the colon, and created a temporary colostomy. The colostomy reversal took place on September 25.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The patient sued both ObGyns, alleging that they should have found the colon injury during surgery. The primary ObGyn settled before trial and the case continued against the assisting ObGyn. It was undisputed that one or both of the physicians caused the tear, but that was not the patient’s claim. The patient alleged that negligence occurred when the injury was not intraoperatively detected. Had the injury been found during surgery, a general surgeon could have performed a primary repair, saving the patient from further surgery and colostomy. The patient claimed mental anguish and embarrassment from the colostomy. Her abdomen is still tender and she has significant scarring.

PHYSICIAN'S CLAIM: There was no negligence. Nothing was unusual about the nature of the procedure, and nothing unusual was seen intraoperatively that would have led them to search for an injury. They performed adequate and appropriate exploration before closing. The linear tear on the underside of the sigmoid colon was very inconspicuous in size, shape, and location, and was away from the operative area. The injury likely occurred during manipulation of the sigmoid colon, which generally has to be retracted before the uterus can be removed. Even if the injury had been found intraoperatively, a general surgeon would have had to convert to laparoscopy to repair the colon.

VERDICT: After a settlement was reached with the primary gynecologist, a Texas defense verdict was returned for the assisting gynecologist.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Barbed sutures shorten cesarean closure time, reduce blood loss

DALLAS – Using knotless barbed sutures to close the uterine incision after cesarean delivery reduced operating time and blood loss, according to a recent randomized controlled study.

“On average, knotless barbed sutures were 1 minute and 43 seconds faster,” said David Peleg, MD, discussing the study results at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Average uterine closure time with knotless barbed sutures was 3 minutes and 37 seconds; with smooth sutures, average closure time was 5 minutes and 20 seconds (103-second difference; 95% confidence interval, 67.69-138.47 seconds; P less than .001).

Barbed sutures, in contrast, are usually made of monofilament with barbs created by the addition of tiny diagonal cuts made just partway through the suture material. When the suture is pulled through with the angle of the barbs, it pulls smoothly, but pulling back against the barb angle causes the barbs to protrude and catch against tissue, preventing slippage and eliminating the need for knots.

The fact that the monofilament has been partially cut to create the barbs can also reduce tensile strength, but some of the other disadvantages of smooth sutures are avoided, said Dr. Peleg.

The suture material used for the study was bidirectional, with the barbs running in opposite directions from the midline and a needle swaged onto each end; other barbed suture systems have an integral loop at one end of a unidirectionally barbed length of suture material that is used to anchor the first suture. The brand used was Stratafix.

The prospective study was necessarily unblinded, and compared the knotless barbed sutures with smooth sutures using polyglactin 910 braided material (Vicryl) for use during closure of the uterine incision during cesarean section procedures.

Patients were eligible if they were having an elective cesarean section after at least 38 weeks’ gestation, or if they were having a cesarean for the usual obstetric indications after laboring. Women with previous cesareans who failed a trial of labor were eligible.

The primary outcome was the length of time to close the uterine incision, measured from the start of suturing until hemostasis was achieved; the time included hemostatic suturing.

After a small pilot study that established a baseline suturing time with polyglactin 910 sutures of 6 minutes (standard deviation, 2 minutes and 10 seconds), Dr. Peleg and his collaborators determined that they would need to enroll at least 34 women per study arm to detect a decrease of 25% in suture time – to 4.5 minutes – with barbed sutures.

“The decrease in closure time is not linear,” said Dr. Peleg, so they increased their sample size by 50%, to 51 patients in each group, to ensure statistical significance of the results.

One of the challenges of a surgical randomized controlled trial is ensuring uniform technique; for this study, all patients had epidural or spinal anesthesia and antibiotics before opening. Surgeon clinical judgment was used to determine whether a Pfannenstiel or low transverse incision was made. In either case, there was no closure of the parietal peritoneum or the rectus muscles, and subcutaneous closure was used if tissues were greater than 2 cm in depth. Subcuticular stitches were used if possible.

Looking at secondary outcomes, there was a trend toward shorter total operative time with barbed sutures that didn’t reach statistical significance (20.1 min for barbed sutures vs. 23.1 for conventional, P = .062). However, fewer hemostatic sutures were required when barbed sutures were used: Extra sutures were used in 16 of the barbed group vs. 41 who had conventional sutures (P less than .001). Those receiving barbed sutures also had significantly less blood loss and estimated total blood loss during uterine closure than the conventional suture group (P = .005 and P = .002, respectively).

No study patients experienced serious postoperative complications; there were no infections, hematomas, or other wound complications, said Dr. Peleg of Bar-Ilan University, Zefat, Israel.

On the pro side for wider implementation of the use of barbed sutures for uterine closure stand the quicker closure and better hemostasis, along with the theoretical benefits of having no knots. Additionally, said Dr. Peleg, “there’s a gentle learning curve – it’s relatively easy to get used to the technique” of using barbed sutures. And, he said, “surgeons find them satisfying to use.”

However, he acknowledged the extra expense of barbed suture material – depending on the location and supplier, he estimated the cost could run from 7- to 20-fold for the barbed sutures, which he said cost $23.50 apiece. Also, he said, though the results were statistically significant, “Are they clinically significant? Does a difference in closure time of one minute 43 seconds, and a decrease in blood loss of 47 milliliters matter?”

Other considerations, he said, will require longer-term study. Polydioxanone, used for the barbed sutures, has a longer absorption time – a factor with unknown clinical implications in this application. Other longer-term outcomes, such as vaginal birth after cesarean success rates, rates of uterine rupture, the thickness of the uterine scar, and rates of adhesions and placenta accreta, will need to be tracked for years.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest and specifically reported that they had no relevant consulting or research agreements with suture manufacturers or marketers.

SOURCE: Peleg D et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract 32.

DALLAS – Using knotless barbed sutures to close the uterine incision after cesarean delivery reduced operating time and blood loss, according to a recent randomized controlled study.

“On average, knotless barbed sutures were 1 minute and 43 seconds faster,” said David Peleg, MD, discussing the study results at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Average uterine closure time with knotless barbed sutures was 3 minutes and 37 seconds; with smooth sutures, average closure time was 5 minutes and 20 seconds (103-second difference; 95% confidence interval, 67.69-138.47 seconds; P less than .001).

Barbed sutures, in contrast, are usually made of monofilament with barbs created by the addition of tiny diagonal cuts made just partway through the suture material. When the suture is pulled through with the angle of the barbs, it pulls smoothly, but pulling back against the barb angle causes the barbs to protrude and catch against tissue, preventing slippage and eliminating the need for knots.

The fact that the monofilament has been partially cut to create the barbs can also reduce tensile strength, but some of the other disadvantages of smooth sutures are avoided, said Dr. Peleg.

The suture material used for the study was bidirectional, with the barbs running in opposite directions from the midline and a needle swaged onto each end; other barbed suture systems have an integral loop at one end of a unidirectionally barbed length of suture material that is used to anchor the first suture. The brand used was Stratafix.

The prospective study was necessarily unblinded, and compared the knotless barbed sutures with smooth sutures using polyglactin 910 braided material (Vicryl) for use during closure of the uterine incision during cesarean section procedures.

Patients were eligible if they were having an elective cesarean section after at least 38 weeks’ gestation, or if they were having a cesarean for the usual obstetric indications after laboring. Women with previous cesareans who failed a trial of labor were eligible.

The primary outcome was the length of time to close the uterine incision, measured from the start of suturing until hemostasis was achieved; the time included hemostatic suturing.

After a small pilot study that established a baseline suturing time with polyglactin 910 sutures of 6 minutes (standard deviation, 2 minutes and 10 seconds), Dr. Peleg and his collaborators determined that they would need to enroll at least 34 women per study arm to detect a decrease of 25% in suture time – to 4.5 minutes – with barbed sutures.

“The decrease in closure time is not linear,” said Dr. Peleg, so they increased their sample size by 50%, to 51 patients in each group, to ensure statistical significance of the results.

One of the challenges of a surgical randomized controlled trial is ensuring uniform technique; for this study, all patients had epidural or spinal anesthesia and antibiotics before opening. Surgeon clinical judgment was used to determine whether a Pfannenstiel or low transverse incision was made. In either case, there was no closure of the parietal peritoneum or the rectus muscles, and subcutaneous closure was used if tissues were greater than 2 cm in depth. Subcuticular stitches were used if possible.

Looking at secondary outcomes, there was a trend toward shorter total operative time with barbed sutures that didn’t reach statistical significance (20.1 min for barbed sutures vs. 23.1 for conventional, P = .062). However, fewer hemostatic sutures were required when barbed sutures were used: Extra sutures were used in 16 of the barbed group vs. 41 who had conventional sutures (P less than .001). Those receiving barbed sutures also had significantly less blood loss and estimated total blood loss during uterine closure than the conventional suture group (P = .005 and P = .002, respectively).

No study patients experienced serious postoperative complications; there were no infections, hematomas, or other wound complications, said Dr. Peleg of Bar-Ilan University, Zefat, Israel.

On the pro side for wider implementation of the use of barbed sutures for uterine closure stand the quicker closure and better hemostasis, along with the theoretical benefits of having no knots. Additionally, said Dr. Peleg, “there’s a gentle learning curve – it’s relatively easy to get used to the technique” of using barbed sutures. And, he said, “surgeons find them satisfying to use.”

However, he acknowledged the extra expense of barbed suture material – depending on the location and supplier, he estimated the cost could run from 7- to 20-fold for the barbed sutures, which he said cost $23.50 apiece. Also, he said, though the results were statistically significant, “Are they clinically significant? Does a difference in closure time of one minute 43 seconds, and a decrease in blood loss of 47 milliliters matter?”

Other considerations, he said, will require longer-term study. Polydioxanone, used for the barbed sutures, has a longer absorption time – a factor with unknown clinical implications in this application. Other longer-term outcomes, such as vaginal birth after cesarean success rates, rates of uterine rupture, the thickness of the uterine scar, and rates of adhesions and placenta accreta, will need to be tracked for years.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest and specifically reported that they had no relevant consulting or research agreements with suture manufacturers or marketers.

SOURCE: Peleg D et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract 32.

DALLAS – Using knotless barbed sutures to close the uterine incision after cesarean delivery reduced operating time and blood loss, according to a recent randomized controlled study.

“On average, knotless barbed sutures were 1 minute and 43 seconds faster,” said David Peleg, MD, discussing the study results at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Average uterine closure time with knotless barbed sutures was 3 minutes and 37 seconds; with smooth sutures, average closure time was 5 minutes and 20 seconds (103-second difference; 95% confidence interval, 67.69-138.47 seconds; P less than .001).

Barbed sutures, in contrast, are usually made of monofilament with barbs created by the addition of tiny diagonal cuts made just partway through the suture material. When the suture is pulled through with the angle of the barbs, it pulls smoothly, but pulling back against the barb angle causes the barbs to protrude and catch against tissue, preventing slippage and eliminating the need for knots.

The fact that the monofilament has been partially cut to create the barbs can also reduce tensile strength, but some of the other disadvantages of smooth sutures are avoided, said Dr. Peleg.

The suture material used for the study was bidirectional, with the barbs running in opposite directions from the midline and a needle swaged onto each end; other barbed suture systems have an integral loop at one end of a unidirectionally barbed length of suture material that is used to anchor the first suture. The brand used was Stratafix.

The prospective study was necessarily unblinded, and compared the knotless barbed sutures with smooth sutures using polyglactin 910 braided material (Vicryl) for use during closure of the uterine incision during cesarean section procedures.

Patients were eligible if they were having an elective cesarean section after at least 38 weeks’ gestation, or if they were having a cesarean for the usual obstetric indications after laboring. Women with previous cesareans who failed a trial of labor were eligible.

The primary outcome was the length of time to close the uterine incision, measured from the start of suturing until hemostasis was achieved; the time included hemostatic suturing.

After a small pilot study that established a baseline suturing time with polyglactin 910 sutures of 6 minutes (standard deviation, 2 minutes and 10 seconds), Dr. Peleg and his collaborators determined that they would need to enroll at least 34 women per study arm to detect a decrease of 25% in suture time – to 4.5 minutes – with barbed sutures.

“The decrease in closure time is not linear,” said Dr. Peleg, so they increased their sample size by 50%, to 51 patients in each group, to ensure statistical significance of the results.

One of the challenges of a surgical randomized controlled trial is ensuring uniform technique; for this study, all patients had epidural or spinal anesthesia and antibiotics before opening. Surgeon clinical judgment was used to determine whether a Pfannenstiel or low transverse incision was made. In either case, there was no closure of the parietal peritoneum or the rectus muscles, and subcutaneous closure was used if tissues were greater than 2 cm in depth. Subcuticular stitches were used if possible.

Looking at secondary outcomes, there was a trend toward shorter total operative time with barbed sutures that didn’t reach statistical significance (20.1 min for barbed sutures vs. 23.1 for conventional, P = .062). However, fewer hemostatic sutures were required when barbed sutures were used: Extra sutures were used in 16 of the barbed group vs. 41 who had conventional sutures (P less than .001). Those receiving barbed sutures also had significantly less blood loss and estimated total blood loss during uterine closure than the conventional suture group (P = .005 and P = .002, respectively).

No study patients experienced serious postoperative complications; there were no infections, hematomas, or other wound complications, said Dr. Peleg of Bar-Ilan University, Zefat, Israel.

On the pro side for wider implementation of the use of barbed sutures for uterine closure stand the quicker closure and better hemostasis, along with the theoretical benefits of having no knots. Additionally, said Dr. Peleg, “there’s a gentle learning curve – it’s relatively easy to get used to the technique” of using barbed sutures. And, he said, “surgeons find them satisfying to use.”

However, he acknowledged the extra expense of barbed suture material – depending on the location and supplier, he estimated the cost could run from 7- to 20-fold for the barbed sutures, which he said cost $23.50 apiece. Also, he said, though the results were statistically significant, “Are they clinically significant? Does a difference in closure time of one minute 43 seconds, and a decrease in blood loss of 47 milliliters matter?”

Other considerations, he said, will require longer-term study. Polydioxanone, used for the barbed sutures, has a longer absorption time – a factor with unknown clinical implications in this application. Other longer-term outcomes, such as vaginal birth after cesarean success rates, rates of uterine rupture, the thickness of the uterine scar, and rates of adhesions and placenta accreta, will need to be tracked for years.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest and specifically reported that they had no relevant consulting or research agreements with suture manufacturers or marketers.

SOURCE: Peleg D et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract 32.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Closure time and blood loss were less with barbed sutures closing the uterine incision.

Major finding: Average uterine incision closure time was 3:37 minutes with knotless barbed sutures and 5:20 minutes with conventional smooth sutures.

Study details: Randomized controlled trial of 102 women undergoing cesarean section.

Disclosures: The study had no external sources of funding, and the study authors reported no relevant outside support.

Source: Peleg D et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract 32.

These amniotic biomarkers predicted pPROM in women undergoing fetal surgery for spinal cord defect

DALLAS – Two molecular biomarkers in amniotic fluid seem to predict preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM) and subsequent premature delivery in women whose fetuses undergo surgical repair of spinal cord defects.

Matrix metalloproteinase–8 (MMP-8) and lactic acid levels were significantly higher in these women than in a comparator group of women who did not deliver a premature infant after the repair, Aikaterini Athanasiou, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine.

“Based on this pilot study, it appears that elevated amniotic levels of lactic acid and MMP-8 at time of surgery might identify a subset of women with increased susceptibility for pPROM and shorter time to delivery,” said Dr. Athanasiou, a fellow in obstetrics and gynecology at Cornell University, New York. She presented the work on behalf of primary author Antonio Moron, MD, PhD, of the Federal University of São Paulo.

Dr. Athanasiou was part of the Cornell team that conducted molecular assays on amniotic fluid samples drawn from 26 women carrying fetuses about to have corrective surgery for spinal defects in the fetuses. The women were all patients at the Federal Hospital of São Paulo. Samples were drawn immediately before surgery commenced, frozen, and shipped to Cornell for assay.

After surgical repair, 7 of the women (27%) later experienced pPROM and 19 did not.

At baseline, there were no significant differences between the groups. Women were a mean age of 32 years, with a mean of two prior pregnancies. There were no differences in prior cesarean and vaginal births, smoking status, and fetal gender. The defect was most commonly a myelomeningocele (about 70% of each group). Rachischisis was next most common, occurring in 27% of the pPROM group and 21% of the non-pPROM group. There were two cases of encephalocele, both in the non-pPROM group.

The length of surgery was not significantly different between those who experienced pPROM and those who did not (121 vs. 130 minutes). Wound healing time was 7 days for each group, as was the mean length of hospital stay.

Both groups went a mean of 57 days from surgery to delivery, although the fetal gestational age was almost a week younger in the pPROM group (33.7 vs. 34.4 weeks). These infants were also smaller at birth (2,247 g vs. 2,410 g).

The Cornell team examined five potential biomarkers in each amniotic fluid sample: MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-2, lactic acid, and interleukin-6 (IL-6). The levels of IL-6, MMP-2, and MMP-9 were similar between groups.

However, lactic acid was significantly higher in the pPROM group (7.1 vs. 5.9 mU/mL). MMP-8 was also significantly elevated in the pPROM group (1.7 vs. 0.6 mcg/mL).

Dr. Athanasiou and her colleagues also observed an inverse relationship between MMP-8 levels and gestational age at delivery, which was statistically significant. There was also an inverse relationship between lactic acid levels and gestational age, but this did not reach statistical significance.

“While further investigations are needed to verify our findings, our data suggest that these differences are present before fetal surgery and that an increase in intra-amniotic anaerobic glycolysis as evidenced by elevated lactic acid may enhance MMP-8 production, which will weaken the maternal-fetal membranes,” Dr. Athanasiou said. “The mechanism may not be related to inflammation, as evidenced by the lack of association between pPROM and IL-6.”

She had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Moron A et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan:218(1);S64.

DALLAS – Two molecular biomarkers in amniotic fluid seem to predict preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM) and subsequent premature delivery in women whose fetuses undergo surgical repair of spinal cord defects.

Matrix metalloproteinase–8 (MMP-8) and lactic acid levels were significantly higher in these women than in a comparator group of women who did not deliver a premature infant after the repair, Aikaterini Athanasiou, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine.