User login

Multidisciplinary care improves surgical outcomes for elderly patients

and were able to leave the hospital after a shorter stay, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 400 patients.

Data from previous studies suggest that preoperative assessment by geriatric experts can improve outcomes for the elderly, who are more likely than are younger patients to develop preventable postoperative complications, and “this evidence supports the formulation of a different approach to preoperative assessment and postoperative care for this population,” wrote Shelley R. McDonald, DO, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

The intervention, known as the Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH), was described as “a quality improvement initiative with prospective data collection.” Patients in a geriatrics clinic within an academic center were selected for the study if they were at high risk for complications linked to elective abdominal surgery. High risk was defined as older than 85 years of age, or older than 65 years of age with conditions including cognitive impairment, recent weight loss, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy (JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513).

The POSH intervention patients received preoperative evaluation from a team including a geriatrician, geriatric resource nurse, social worker, program administrator, and nurse practitioner from the preoperative anesthesia testing clinic. Patients and families were advised on risk management and care optimization involving cognition, comorbidities, medications, mobility, functional status, nutrition, hydration, pain, and advanced care planning.

Patients in the POSH group were on average older, had more comorbidities, and were more likely to be smokers. But despite these disadvantaging characteristics, they still had better outcomes in several important variables than did those in the control group.

The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays, compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days), and significantly lower all-cause readmission rates at both 7 days (2.8% vs. 9.9%) and 30 days (7.8% vs. 18.3%). The significance persisted whether the surgeries were laparoscopic or open.

The overall complication rate was lower in the POSH group, compared with the controls, but fell short of statistical significance (44.8% vs. 58.7%, P = .01). However, rates of specific complications were significantly lower in the POSH group, compared with controls, including postoperative cardiogenic or hypovolemic shock (2.2% vs. 8.4%), bleeding, either during or after surgery (6.1% vs. 15.4%), and postoperative ileus (4.9% vs. 20.3%).

“Delirium was identified in POSH patients at higher rates than in the control group, which is not unexpected because higher postoperative delirium rates are known to be identified with increased screening,” the researchers noted. “Collaborative care allows for increasing the recognition of geriatric syndromes like delirium, more focus on symptom management, and proactively anticipating complications,” they said.

The study results were limited by several factors including a long enrollment period for the POSH patients, and potential changes in surgical protocols, the researchers said. However, the findings support the need for further research and more refined analysis to identify the most beneficial aspects of care, and to support better clinical decision making about the timing of interventions and the type of patient who could benefit, they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence National Program Award provided salary and database support.

SOURCE: McDonald S et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513.

and were able to leave the hospital after a shorter stay, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 400 patients.

Data from previous studies suggest that preoperative assessment by geriatric experts can improve outcomes for the elderly, who are more likely than are younger patients to develop preventable postoperative complications, and “this evidence supports the formulation of a different approach to preoperative assessment and postoperative care for this population,” wrote Shelley R. McDonald, DO, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

The intervention, known as the Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH), was described as “a quality improvement initiative with prospective data collection.” Patients in a geriatrics clinic within an academic center were selected for the study if they were at high risk for complications linked to elective abdominal surgery. High risk was defined as older than 85 years of age, or older than 65 years of age with conditions including cognitive impairment, recent weight loss, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy (JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513).

The POSH intervention patients received preoperative evaluation from a team including a geriatrician, geriatric resource nurse, social worker, program administrator, and nurse practitioner from the preoperative anesthesia testing clinic. Patients and families were advised on risk management and care optimization involving cognition, comorbidities, medications, mobility, functional status, nutrition, hydration, pain, and advanced care planning.

Patients in the POSH group were on average older, had more comorbidities, and were more likely to be smokers. But despite these disadvantaging characteristics, they still had better outcomes in several important variables than did those in the control group.

The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays, compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days), and significantly lower all-cause readmission rates at both 7 days (2.8% vs. 9.9%) and 30 days (7.8% vs. 18.3%). The significance persisted whether the surgeries were laparoscopic or open.

The overall complication rate was lower in the POSH group, compared with the controls, but fell short of statistical significance (44.8% vs. 58.7%, P = .01). However, rates of specific complications were significantly lower in the POSH group, compared with controls, including postoperative cardiogenic or hypovolemic shock (2.2% vs. 8.4%), bleeding, either during or after surgery (6.1% vs. 15.4%), and postoperative ileus (4.9% vs. 20.3%).

“Delirium was identified in POSH patients at higher rates than in the control group, which is not unexpected because higher postoperative delirium rates are known to be identified with increased screening,” the researchers noted. “Collaborative care allows for increasing the recognition of geriatric syndromes like delirium, more focus on symptom management, and proactively anticipating complications,” they said.

The study results were limited by several factors including a long enrollment period for the POSH patients, and potential changes in surgical protocols, the researchers said. However, the findings support the need for further research and more refined analysis to identify the most beneficial aspects of care, and to support better clinical decision making about the timing of interventions and the type of patient who could benefit, they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence National Program Award provided salary and database support.

SOURCE: McDonald S et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513.

and were able to leave the hospital after a shorter stay, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 400 patients.

Data from previous studies suggest that preoperative assessment by geriatric experts can improve outcomes for the elderly, who are more likely than are younger patients to develop preventable postoperative complications, and “this evidence supports the formulation of a different approach to preoperative assessment and postoperative care for this population,” wrote Shelley R. McDonald, DO, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

The intervention, known as the Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH), was described as “a quality improvement initiative with prospective data collection.” Patients in a geriatrics clinic within an academic center were selected for the study if they were at high risk for complications linked to elective abdominal surgery. High risk was defined as older than 85 years of age, or older than 65 years of age with conditions including cognitive impairment, recent weight loss, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy (JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513).

The POSH intervention patients received preoperative evaluation from a team including a geriatrician, geriatric resource nurse, social worker, program administrator, and nurse practitioner from the preoperative anesthesia testing clinic. Patients and families were advised on risk management and care optimization involving cognition, comorbidities, medications, mobility, functional status, nutrition, hydration, pain, and advanced care planning.

Patients in the POSH group were on average older, had more comorbidities, and were more likely to be smokers. But despite these disadvantaging characteristics, they still had better outcomes in several important variables than did those in the control group.

The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays, compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days), and significantly lower all-cause readmission rates at both 7 days (2.8% vs. 9.9%) and 30 days (7.8% vs. 18.3%). The significance persisted whether the surgeries were laparoscopic or open.

The overall complication rate was lower in the POSH group, compared with the controls, but fell short of statistical significance (44.8% vs. 58.7%, P = .01). However, rates of specific complications were significantly lower in the POSH group, compared with controls, including postoperative cardiogenic or hypovolemic shock (2.2% vs. 8.4%), bleeding, either during or after surgery (6.1% vs. 15.4%), and postoperative ileus (4.9% vs. 20.3%).

“Delirium was identified in POSH patients at higher rates than in the control group, which is not unexpected because higher postoperative delirium rates are known to be identified with increased screening,” the researchers noted. “Collaborative care allows for increasing the recognition of geriatric syndromes like delirium, more focus on symptom management, and proactively anticipating complications,” they said.

The study results were limited by several factors including a long enrollment period for the POSH patients, and potential changes in surgical protocols, the researchers said. However, the findings support the need for further research and more refined analysis to identify the most beneficial aspects of care, and to support better clinical decision making about the timing of interventions and the type of patient who could benefit, they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence National Program Award provided salary and database support.

SOURCE: McDonald S et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: A preoperative surgical intervention improved outcomes and shortened hospital stays for seniors.

Major finding: The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days).

Study details: The data come from a study of 183 surgery patients and 143 controls.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: McDonald S JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513

Persistent opioid use a risk after surgery in teens and young adults

For a subset of opioid-naive adolescents and young adults who received perioperative opioid scripts, those prescriptions were filled for months after the surgery, raising concerns about long-term risk for substance use disorder.

To get an idea of the teen opioid problem, from 1997 to 2012 for adolescents aged 15-19 years, the incidence of hospitalizations for opioid poisonings per 100,000 teens increased from 3.69 to 10.17, an increase of 176%, according to a study in JAMA Pediatrics (2016;170[12]:1195-201). Adolescents are at a three to five time higher risk for serious medical outcomes when hospitalized with opioid poisoning, such as life-threatening symptoms or death, compared with younger children, according to a study reporting prescription drug exposures among children (Pediatrics. 2017;139[4]:e20163382).

These figures are concerning in part because “a significant association between medical use of prescription opioids alone in adolescence and subsequent nonmedical use of prescription opioids was observed at age 35 years” in a national longitudinal study reported in the journal Pain (2016 Oct;157[10]:2173-8), said Calista M. Harbaugh, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her study coauthors.

The study in Pediatrics, which drew from a large national insurance claims database, found some patient characteristics had independent associations with increased risk of persistent opioid use. These included being female or older, as well as having a prior history of substance use disorder, chronic pain, or filling an opioid prescription preoperatively.

Dr. Harbaugh and her collaborators used a large national research database to select opioid-naive patients aged 13-21 years who received 1 of 13 surgical procedures. A total of 88,637 opioid-naive surgical patients were included in the study, with 110,432 control nonsurgical patients. The control group consisted of 3% of the database’s nonsurgical patients who met age and opioid-naivete criteria. Patients in both groups also had to have continuous insurance for the prior 12 months, not have had an opioid prescription filled within the prior year, and not have received any subsequent surgical procedures during the study period.

To be able to compare medication use among patients receiving different types of opioids, the opioid component of all prescriptions was converted to milligrams, and then used to calculate oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) for each prescription.

Although the most common procedures were tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (35.9% of patients), arthroscopic knee repair (25.3%), and appendectomy, (18.6%), these were not the procedures that were most associated with persistent opioid use.

Overall, 7.1% of patients had an initial daily dosage greater than 100 OMEs for their first postoperative prescription. These high opioid doses were likely to be seen in patients undergoing three procedures known to have considerable postoperative pain: pectus repair, posterior arthrodesis, and supracondylar fracture fixation. However, patients undergoing these procedures weren’t more likely to have persistent opioid use than other surgical patients in the study, the researchers said.

Rather, cholecystectomy and colectomy had the highest risk for persistent opioid use, with adjusted odds ratios of 1.13 and 2.33, respectively. Dr. Harbaugh and her collaborators, in discussing the study’s findings, noted that these two conditions involve high levels of preoperative inflammation and are characterized by visceral pain. This scenario, they said, may set these patients up for visceral and central sensitization and present an increased risk for chronic pain.

Dr. Harbaugh and her colleagues called for preoperative screening for risk factors for persistent opioid use, so that at-risk patients can receive closer monitoring and attention. “We are not suggesting that … pain should be underappreciated or undertreated,” or that at-risk patients should not be prescribed opioids.

The investigators said that their work “points toward the multifactorial etiology of postoperative pain and its complex nature in both the short and long term.” They called for more work to “elucidate the mechanism that underlies new persistent opioid use after certain procedures,” as well as more efforts to better understand how best to use multimodal pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain control measures in the adolescent and young adult population.

The study was funded by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Harbaugh reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures. Some of the other investigators received grants from various agencies.

SOURCE: Harbaugh CM et al. Pediatrics 2018 Jan 1;141(1):e20172439

For a subset of opioid-naive adolescents and young adults who received perioperative opioid scripts, those prescriptions were filled for months after the surgery, raising concerns about long-term risk for substance use disorder.

To get an idea of the teen opioid problem, from 1997 to 2012 for adolescents aged 15-19 years, the incidence of hospitalizations for opioid poisonings per 100,000 teens increased from 3.69 to 10.17, an increase of 176%, according to a study in JAMA Pediatrics (2016;170[12]:1195-201). Adolescents are at a three to five time higher risk for serious medical outcomes when hospitalized with opioid poisoning, such as life-threatening symptoms or death, compared with younger children, according to a study reporting prescription drug exposures among children (Pediatrics. 2017;139[4]:e20163382).

These figures are concerning in part because “a significant association between medical use of prescription opioids alone in adolescence and subsequent nonmedical use of prescription opioids was observed at age 35 years” in a national longitudinal study reported in the journal Pain (2016 Oct;157[10]:2173-8), said Calista M. Harbaugh, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her study coauthors.

The study in Pediatrics, which drew from a large national insurance claims database, found some patient characteristics had independent associations with increased risk of persistent opioid use. These included being female or older, as well as having a prior history of substance use disorder, chronic pain, or filling an opioid prescription preoperatively.

Dr. Harbaugh and her collaborators used a large national research database to select opioid-naive patients aged 13-21 years who received 1 of 13 surgical procedures. A total of 88,637 opioid-naive surgical patients were included in the study, with 110,432 control nonsurgical patients. The control group consisted of 3% of the database’s nonsurgical patients who met age and opioid-naivete criteria. Patients in both groups also had to have continuous insurance for the prior 12 months, not have had an opioid prescription filled within the prior year, and not have received any subsequent surgical procedures during the study period.

To be able to compare medication use among patients receiving different types of opioids, the opioid component of all prescriptions was converted to milligrams, and then used to calculate oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) for each prescription.

Although the most common procedures were tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (35.9% of patients), arthroscopic knee repair (25.3%), and appendectomy, (18.6%), these were not the procedures that were most associated with persistent opioid use.

Overall, 7.1% of patients had an initial daily dosage greater than 100 OMEs for their first postoperative prescription. These high opioid doses were likely to be seen in patients undergoing three procedures known to have considerable postoperative pain: pectus repair, posterior arthrodesis, and supracondylar fracture fixation. However, patients undergoing these procedures weren’t more likely to have persistent opioid use than other surgical patients in the study, the researchers said.

Rather, cholecystectomy and colectomy had the highest risk for persistent opioid use, with adjusted odds ratios of 1.13 and 2.33, respectively. Dr. Harbaugh and her collaborators, in discussing the study’s findings, noted that these two conditions involve high levels of preoperative inflammation and are characterized by visceral pain. This scenario, they said, may set these patients up for visceral and central sensitization and present an increased risk for chronic pain.

Dr. Harbaugh and her colleagues called for preoperative screening for risk factors for persistent opioid use, so that at-risk patients can receive closer monitoring and attention. “We are not suggesting that … pain should be underappreciated or undertreated,” or that at-risk patients should not be prescribed opioids.

The investigators said that their work “points toward the multifactorial etiology of postoperative pain and its complex nature in both the short and long term.” They called for more work to “elucidate the mechanism that underlies new persistent opioid use after certain procedures,” as well as more efforts to better understand how best to use multimodal pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain control measures in the adolescent and young adult population.

The study was funded by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Harbaugh reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures. Some of the other investigators received grants from various agencies.

SOURCE: Harbaugh CM et al. Pediatrics 2018 Jan 1;141(1):e20172439

For a subset of opioid-naive adolescents and young adults who received perioperative opioid scripts, those prescriptions were filled for months after the surgery, raising concerns about long-term risk for substance use disorder.

To get an idea of the teen opioid problem, from 1997 to 2012 for adolescents aged 15-19 years, the incidence of hospitalizations for opioid poisonings per 100,000 teens increased from 3.69 to 10.17, an increase of 176%, according to a study in JAMA Pediatrics (2016;170[12]:1195-201). Adolescents are at a three to five time higher risk for serious medical outcomes when hospitalized with opioid poisoning, such as life-threatening symptoms or death, compared with younger children, according to a study reporting prescription drug exposures among children (Pediatrics. 2017;139[4]:e20163382).

These figures are concerning in part because “a significant association between medical use of prescription opioids alone in adolescence and subsequent nonmedical use of prescription opioids was observed at age 35 years” in a national longitudinal study reported in the journal Pain (2016 Oct;157[10]:2173-8), said Calista M. Harbaugh, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her study coauthors.

The study in Pediatrics, which drew from a large national insurance claims database, found some patient characteristics had independent associations with increased risk of persistent opioid use. These included being female or older, as well as having a prior history of substance use disorder, chronic pain, or filling an opioid prescription preoperatively.

Dr. Harbaugh and her collaborators used a large national research database to select opioid-naive patients aged 13-21 years who received 1 of 13 surgical procedures. A total of 88,637 opioid-naive surgical patients were included in the study, with 110,432 control nonsurgical patients. The control group consisted of 3% of the database’s nonsurgical patients who met age and opioid-naivete criteria. Patients in both groups also had to have continuous insurance for the prior 12 months, not have had an opioid prescription filled within the prior year, and not have received any subsequent surgical procedures during the study period.

To be able to compare medication use among patients receiving different types of opioids, the opioid component of all prescriptions was converted to milligrams, and then used to calculate oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) for each prescription.

Although the most common procedures were tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (35.9% of patients), arthroscopic knee repair (25.3%), and appendectomy, (18.6%), these were not the procedures that were most associated with persistent opioid use.

Overall, 7.1% of patients had an initial daily dosage greater than 100 OMEs for their first postoperative prescription. These high opioid doses were likely to be seen in patients undergoing three procedures known to have considerable postoperative pain: pectus repair, posterior arthrodesis, and supracondylar fracture fixation. However, patients undergoing these procedures weren’t more likely to have persistent opioid use than other surgical patients in the study, the researchers said.

Rather, cholecystectomy and colectomy had the highest risk for persistent opioid use, with adjusted odds ratios of 1.13 and 2.33, respectively. Dr. Harbaugh and her collaborators, in discussing the study’s findings, noted that these two conditions involve high levels of preoperative inflammation and are characterized by visceral pain. This scenario, they said, may set these patients up for visceral and central sensitization and present an increased risk for chronic pain.

Dr. Harbaugh and her colleagues called for preoperative screening for risk factors for persistent opioid use, so that at-risk patients can receive closer monitoring and attention. “We are not suggesting that … pain should be underappreciated or undertreated,” or that at-risk patients should not be prescribed opioids.

The investigators said that their work “points toward the multifactorial etiology of postoperative pain and its complex nature in both the short and long term.” They called for more work to “elucidate the mechanism that underlies new persistent opioid use after certain procedures,” as well as more efforts to better understand how best to use multimodal pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain control measures in the adolescent and young adult population.

The study was funded by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Harbaugh reported that she had no relevant financial disclosures. Some of the other investigators received grants from various agencies.

SOURCE: Harbaugh CM et al. Pediatrics 2018 Jan 1;141(1):e20172439

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Especially for females, older teens, and young adults, there’s a risk for persistent postsurgical opioid use.

Major finding: Opioid use persisted for 4.8% of patients undergoing surgery, compared with 0.1% of patients who did not have surgery.

Study details: Retrospective review of claims database including 88,637 adolescent and young adult patients undergoing surgery, and 110,432 controls who did not have surgery.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Harbaugh reported that she had no conflicts of interest. Some of the other investigators received grants from various agencies.

Source: Harbaugh CM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Jan 1;141(1):e20172439

Predicting MDR Gram-negative infection mortality risk

Source control, defined as location and elimination of the source of the infection, was critical for patient survival in the case of multidrug resistant bacterial infection, according to the results of a case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients who were assessed between 2011 and 2014.

Researchers examined the characteristics of infected patients surviving to hospital discharge compared with those of nonsurvivors to look for predictive factors. Demographically, patients had an overall mean age of 62 years; 30.6% were women; 69.4% were white. The first culture obtained during a surgical ICU admission that grew a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or MDR Acinetobacter spp. was defined as the index culture.

“In this study, 33.9% [21/62] of critically ill surgical patients with a culture positive for MDR Gram-negative bacteria died prior to hospital discharge,” according to Andrew S. Jarrell, PharmD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

With multivariate logistic regression, achievement of source control was the only variable associated with decreased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio 0.04, 95% confidence interval, 0.003-0.52); P = .01).

“Source control status was predictive of in-hospital mortality after controlling for other factors. Specifically, the odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved as compared to when source control was not achieved,” the authors stated (J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6).

Scenarios in which source control was not applicable (pneumonia and urinary tract infection) were also similarly distributed between survivors and nonsurvivors, they reported.

Other than source control, the only significant risk factors for mortality, as seen in univariate analysis, all occurred prior to index culture. They were: vasopressor use (46.3% of survivors, vs. 76.2% of nonsurvivors, P = .03); mechanical ventilation (63.4% vs. 100%, P = .001); and median ICU length of stay (10 days vs. 18 days, P = .001).

“Achievement of source control stands out as a critical factor for patient survival. Clinicians should take this, along with prior ICU LOS, vasopressor use, and mechanical ventilation status, into consideration when evaluating patient prognosis,” Dr. Jarrell and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

Source control, defined as location and elimination of the source of the infection, was critical for patient survival in the case of multidrug resistant bacterial infection, according to the results of a case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients who were assessed between 2011 and 2014.

Researchers examined the characteristics of infected patients surviving to hospital discharge compared with those of nonsurvivors to look for predictive factors. Demographically, patients had an overall mean age of 62 years; 30.6% were women; 69.4% were white. The first culture obtained during a surgical ICU admission that grew a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or MDR Acinetobacter spp. was defined as the index culture.

“In this study, 33.9% [21/62] of critically ill surgical patients with a culture positive for MDR Gram-negative bacteria died prior to hospital discharge,” according to Andrew S. Jarrell, PharmD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

With multivariate logistic regression, achievement of source control was the only variable associated with decreased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio 0.04, 95% confidence interval, 0.003-0.52); P = .01).

“Source control status was predictive of in-hospital mortality after controlling for other factors. Specifically, the odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved as compared to when source control was not achieved,” the authors stated (J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6).

Scenarios in which source control was not applicable (pneumonia and urinary tract infection) were also similarly distributed between survivors and nonsurvivors, they reported.

Other than source control, the only significant risk factors for mortality, as seen in univariate analysis, all occurred prior to index culture. They were: vasopressor use (46.3% of survivors, vs. 76.2% of nonsurvivors, P = .03); mechanical ventilation (63.4% vs. 100%, P = .001); and median ICU length of stay (10 days vs. 18 days, P = .001).

“Achievement of source control stands out as a critical factor for patient survival. Clinicians should take this, along with prior ICU LOS, vasopressor use, and mechanical ventilation status, into consideration when evaluating patient prognosis,” Dr. Jarrell and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

Source control, defined as location and elimination of the source of the infection, was critical for patient survival in the case of multidrug resistant bacterial infection, according to the results of a case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients who were assessed between 2011 and 2014.

Researchers examined the characteristics of infected patients surviving to hospital discharge compared with those of nonsurvivors to look for predictive factors. Demographically, patients had an overall mean age of 62 years; 30.6% were women; 69.4% were white. The first culture obtained during a surgical ICU admission that grew a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or MDR Acinetobacter spp. was defined as the index culture.

“In this study, 33.9% [21/62] of critically ill surgical patients with a culture positive for MDR Gram-negative bacteria died prior to hospital discharge,” according to Andrew S. Jarrell, PharmD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

With multivariate logistic regression, achievement of source control was the only variable associated with decreased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio 0.04, 95% confidence interval, 0.003-0.52); P = .01).

“Source control status was predictive of in-hospital mortality after controlling for other factors. Specifically, the odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved as compared to when source control was not achieved,” the authors stated (J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6).

Scenarios in which source control was not applicable (pneumonia and urinary tract infection) were also similarly distributed between survivors and nonsurvivors, they reported.

Other than source control, the only significant risk factors for mortality, as seen in univariate analysis, all occurred prior to index culture. They were: vasopressor use (46.3% of survivors, vs. 76.2% of nonsurvivors, P = .03); mechanical ventilation (63.4% vs. 100%, P = .001); and median ICU length of stay (10 days vs. 18 days, P = .001).

“Achievement of source control stands out as a critical factor for patient survival. Clinicians should take this, along with prior ICU LOS, vasopressor use, and mechanical ventilation status, into consideration when evaluating patient prognosis,” Dr. Jarrell and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE

Key clinical point: Source control was the most important predictor of MDR Gram-negative infection mortality in hospitalized patients.

Major finding: The odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved.

Study details: Case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients from 2011 to 2014 who had an MDR infection.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

Implementing enhanced recovery protocols for gynecologic surgery

“Enhanced Recovery After Surgery” (ERAS) practices and protocols have been increasingly refined and adopted for the field of gynecology, and there is hope among gynecologic surgeons – and some recent evidence – that, with the ERAS movement, we are improving patient recoveries and outcomes and minimizing the need for opioids.

This applies not only to open surgeries but also to the minimally invasive procedures that already are prized for significant reductions in morbidity and length of stay. The overarching and guiding principle of ERAS is that any surgery – whether open or minimally invasive, major or minor – places stress on the body and is associated with risks and morbidity.

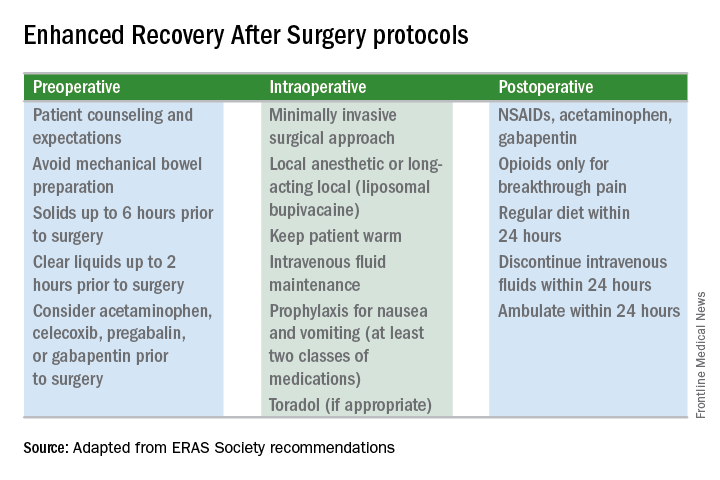

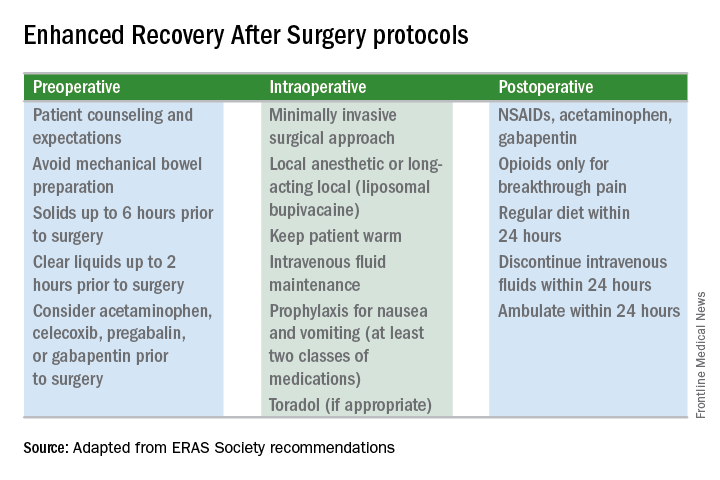

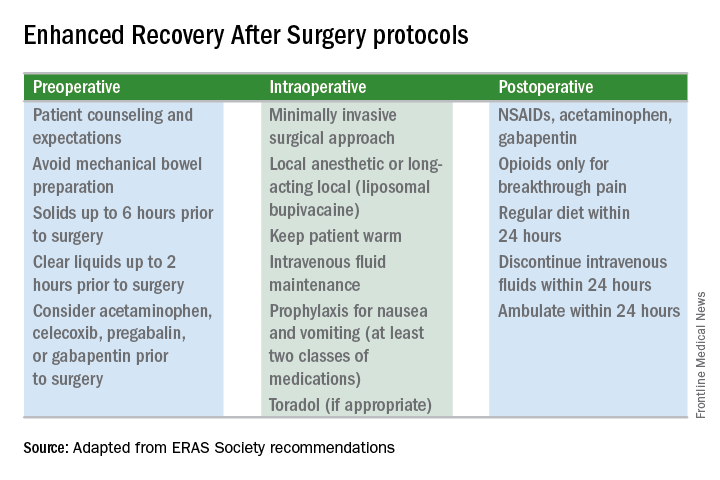

Enhanced recovery protocols are multidisciplinary, perioperative approaches designed to lessen the body’s stress response to surgery. The protocols and pathways offer us a menu of small changes that, in the aggregate, can lead to large and demonstrable benefits – especially when these small changes are chosen across the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative arenas and then standardized in one’s practice. Among the major components of ERAS practices and protocols are limiting preoperative fasting, employing multimodal analgesia, encouraging early ambulation and early postsurgical feeding, and creating culture shift that includes greater emphasis on patient expectations.

In our practice, we are incorporating ERAS practices not only in hopes of reducing the stress of all surgeries before, during, and after, but also with the goal of achieving a postoperative opioid-free hysterectomy, myomectomy, and extensive endometriosis surgery. (All of our advanced procedures are performed laparoscopically or robotically.)

Over the past 7 or so years, we have adopted a multimodal approach to pain control that includes a bundle of preoperative analgesics – acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib (we call it “TLC” for Tylenol, Lyrica, and Celebrex) – and the use of liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries. We are now turning toward ERAS nutritional changes, most of which run counter to traditional paradigms for surgical care. And in other areas, such as dedicated preoperative counseling, we continue to refine and improve our practices.

Improved Outcomes

The ERAS mindset notably intersected gynecology with the publication in 2016 of a two-part series of guidelines for gynecology/oncology surgery from the ERAS Society. The 8-year-old society has its roots in a study group of European surgeons and others who decided to examine surgical practices and the concept of multimodal surgical care put forth in the 1990s by Henrik Kehlet, MD, PhD, then a professor at the University of Copenhagen.

The first set of recommendations addressed pre- and intraoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22), and the second set addressed postoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32). Similar evidence-based recommendations were previously written for colonic resections, rectal and pelvic surgery, and other surgical specialties.

Most of the published outcomes of enhanced recovery protocols come from colorectal surgery. As noted in the ERAS Society gynecology/oncology guidelines, the benefits include an average reduction in length of stay of 2.5 days and a decrease in complications by as much as 50%.

There is growing evidence, however, that ERAS programs are also beneficial for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, and outcomes from gynecology – including minimally invasive surgery – are also being reported.

For instance, a retrospective case-control study of 55 consecutive gynecologic oncology patients treated at the University of California, San Francisco, with laparoscopic or robotic surgery and an enhanced recovery pathway – and 110 historical control patients matched on the basis of age and surgery type – found significant improvements in recovery time, decreased pain despite reduced opioid use, and overall lower hospital costs (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;128[1]:138-44).

The enhanced recovery pathway included patient education, multimodal antiemetics, multimodal analgesia, and balanced fluid administration. Early catheter removal, ambulation, and feeding were also components. Analgesia included routine preoperative gabapentin, diclofenac, and acetaminophen; routine postoperative gabapentin, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen; and transversus abdominis plane blocks in 32 of the ERAS patients.

ERAS patients were significantly more likely to be discharged on day 1 (91%, compared with 60% in the control group). Opioid use decreased by 30%, and pain scores on postoperative day 1 were significantly lower.

Another study looking at the effect of enhanced recovery implementation in gynecologic surgeries at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, (gynecologic oncology, urogynecology, and general gynecology) similarly reported benefits for vaginal and minimally invasive procedures, as well as for open procedures (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128[3]:457-66).

In the minimally invasive group, investigators compared 324 patients before ERAS implementation with 249 patients afterward and found that the median length of stay was unchanged (1 day). However, intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption decreased significantly and – even though actual pain scores improved only slightly – patient satisfaction scores improved markedly among post-ERAS patients. Patients gave higher marks, for instance, to questions regarding pain control (“how well your pain was controlled”) and teamwork (“staff worked together to care for you”).

Reducing Opioids

New opioid use that persists after a surgical procedure is a postsurgical complication that we all should be working to prevent. It has been estimated that 6% of surgical patients – even those who’ve had relatively minor surgical procedures – will become long-term opioid users, developing a dependence on the drugs prescribed to them for postsurgical pain.

This was shown last year in a national study of insurance claims data from between 2013 and 2014; investigators identified adults without opioid use in the year prior to surgery (including hysterectomy) and found that 5.9%-6.5% were filling opioid prescriptions 90-180 days after their surgical procedure. The incidence in a nonoperative control cohort was 0.4% (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jun 21;152[6]:e170504). Notably, this prolonged use was greatest in patients with prior pain conditions, substance abuse, and mental health disorders – a finding that may have implications for the counseling we provide prior to surgery.

It’s not clear what the optimal analgesic regimen is for minimally invasive or other gynecologic surgeries. What is clearly recommended, however, is that the approach be multifaceted. In our practice, we believe that the preoperative use of acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib plays an important role in reducing postoperative pain and opioid use. But we also have striven to create a practice-wide culture shift (throughout the operating and recovery rooms), for instance, that encourages using the least amounts of narcotics possible and using the shortest-acting formulations possible.

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are also often part of ERAS protocols; they have been shown in at least two randomized controlled trials of abdominal hysterectomy to reduce intraoperative fentanyl requirements and to reduce immediate postoperative pain scores and postoperative morphine requirements (Anesth Analg. 2008 Dec;107[6]:2056-60; J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Jul-Sep;30[3]:391-6).

More recently, liposomal bupivacaine, which is slowly released over several days, has gained traction as a substitute for standard bupivacaine and other agents in TAP blocks. In one recent retrospective study, abdominal incision infiltration with liposomal bupivacaine was associated with less opioid use (with no change in pain scores), compared with bupivacaine hydrochloride after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128[5]:1009-17). It’s significantly more expensive, however, making it likely that the formulation is being used more judiciously in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery than in open surgeries.

Because of costs, we currently are restricted to using liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries only. In our practice, the single 20 mL vial (266 mg of liposomal bupivacaine) is diluted with 20 mL of normal saline, but it can be further diluted without loss of efficacy. With a 16-gauge needle, the liposomal bupivacaine is distributed across the incisions (usually 20 mL in the umbilicus with a larger incision and 10 mL in each of the two lateral incisions). Patients are counseled that they may have more discomfort after 3 days, but by this point most are mobile and feeling relatively well with a combination of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

With growing visibility of the problem of narcotic dependence in the United States, patients seem increasingly receptive and even eager to limit or avoid the use of opioids. Patients should be counseled that minimizing or avoiding opioids may also speed recovery. Narcotics cause gut motility to slow down, which may hinder mobilization. Early mobilization (within 24 hours) is among the enhanced recovery elements that the ERAS Society guidelines say is “of particular value” for minimally invasive surgery, along with maintenance of normothermia and normovolemia with maintenance of adequate cardiac output.

Selecting Steps

Our practice is also trying to reduce preoperative bowel preparation and preoperative fasting, both of which have been found to be stressful for the body without evidence of benefit. These practices can lead to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are associated with increased morbidity and length of stay.

It is now recommended that clear fluids be allowed up to 2 hours before surgery and solids up to 6 hours before. Some health systems and practices also recommend presurgical carbohydrate loading (for example, 10 ounces of apple juice 2 hours before surgery) – another small change on the ERAS menu – to further reduce postoperative insulin resistance and help the body cope with its stress response to surgery.

Along with nutritional changes are also various measures aimed at optimizing the body’s functionality before surgery (“prehabilitation”), from walking 30 minutes a day to abstaining from alcohol for patients who drink heavily.

Throughout the country, enhanced recovery protocols are taking shape in gynecologic surgery. ERAS was featured in an aptly titled panel session at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists: “Outpatient Hysterectomy, ERAS, and Same-Day Discharge: The Next Big Thing in Gyn Surgery.” Others are applying ERAS to scheduled cesarean sections. And in our practice, I believe that if we continue making small changes, we will reach our goal of opioid-free recoveries and a better surgical experience for our patients.

Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is an associate of the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

“Enhanced Recovery After Surgery” (ERAS) practices and protocols have been increasingly refined and adopted for the field of gynecology, and there is hope among gynecologic surgeons – and some recent evidence – that, with the ERAS movement, we are improving patient recoveries and outcomes and minimizing the need for opioids.

This applies not only to open surgeries but also to the minimally invasive procedures that already are prized for significant reductions in morbidity and length of stay. The overarching and guiding principle of ERAS is that any surgery – whether open or minimally invasive, major or minor – places stress on the body and is associated with risks and morbidity.

Enhanced recovery protocols are multidisciplinary, perioperative approaches designed to lessen the body’s stress response to surgery. The protocols and pathways offer us a menu of small changes that, in the aggregate, can lead to large and demonstrable benefits – especially when these small changes are chosen across the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative arenas and then standardized in one’s practice. Among the major components of ERAS practices and protocols are limiting preoperative fasting, employing multimodal analgesia, encouraging early ambulation and early postsurgical feeding, and creating culture shift that includes greater emphasis on patient expectations.

In our practice, we are incorporating ERAS practices not only in hopes of reducing the stress of all surgeries before, during, and after, but also with the goal of achieving a postoperative opioid-free hysterectomy, myomectomy, and extensive endometriosis surgery. (All of our advanced procedures are performed laparoscopically or robotically.)

Over the past 7 or so years, we have adopted a multimodal approach to pain control that includes a bundle of preoperative analgesics – acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib (we call it “TLC” for Tylenol, Lyrica, and Celebrex) – and the use of liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries. We are now turning toward ERAS nutritional changes, most of which run counter to traditional paradigms for surgical care. And in other areas, such as dedicated preoperative counseling, we continue to refine and improve our practices.

Improved Outcomes

The ERAS mindset notably intersected gynecology with the publication in 2016 of a two-part series of guidelines for gynecology/oncology surgery from the ERAS Society. The 8-year-old society has its roots in a study group of European surgeons and others who decided to examine surgical practices and the concept of multimodal surgical care put forth in the 1990s by Henrik Kehlet, MD, PhD, then a professor at the University of Copenhagen.

The first set of recommendations addressed pre- and intraoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22), and the second set addressed postoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32). Similar evidence-based recommendations were previously written for colonic resections, rectal and pelvic surgery, and other surgical specialties.

Most of the published outcomes of enhanced recovery protocols come from colorectal surgery. As noted in the ERAS Society gynecology/oncology guidelines, the benefits include an average reduction in length of stay of 2.5 days and a decrease in complications by as much as 50%.

There is growing evidence, however, that ERAS programs are also beneficial for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, and outcomes from gynecology – including minimally invasive surgery – are also being reported.

For instance, a retrospective case-control study of 55 consecutive gynecologic oncology patients treated at the University of California, San Francisco, with laparoscopic or robotic surgery and an enhanced recovery pathway – and 110 historical control patients matched on the basis of age and surgery type – found significant improvements in recovery time, decreased pain despite reduced opioid use, and overall lower hospital costs (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;128[1]:138-44).

The enhanced recovery pathway included patient education, multimodal antiemetics, multimodal analgesia, and balanced fluid administration. Early catheter removal, ambulation, and feeding were also components. Analgesia included routine preoperative gabapentin, diclofenac, and acetaminophen; routine postoperative gabapentin, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen; and transversus abdominis plane blocks in 32 of the ERAS patients.

ERAS patients were significantly more likely to be discharged on day 1 (91%, compared with 60% in the control group). Opioid use decreased by 30%, and pain scores on postoperative day 1 were significantly lower.

Another study looking at the effect of enhanced recovery implementation in gynecologic surgeries at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, (gynecologic oncology, urogynecology, and general gynecology) similarly reported benefits for vaginal and minimally invasive procedures, as well as for open procedures (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128[3]:457-66).

In the minimally invasive group, investigators compared 324 patients before ERAS implementation with 249 patients afterward and found that the median length of stay was unchanged (1 day). However, intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption decreased significantly and – even though actual pain scores improved only slightly – patient satisfaction scores improved markedly among post-ERAS patients. Patients gave higher marks, for instance, to questions regarding pain control (“how well your pain was controlled”) and teamwork (“staff worked together to care for you”).

Reducing Opioids

New opioid use that persists after a surgical procedure is a postsurgical complication that we all should be working to prevent. It has been estimated that 6% of surgical patients – even those who’ve had relatively minor surgical procedures – will become long-term opioid users, developing a dependence on the drugs prescribed to them for postsurgical pain.

This was shown last year in a national study of insurance claims data from between 2013 and 2014; investigators identified adults without opioid use in the year prior to surgery (including hysterectomy) and found that 5.9%-6.5% were filling opioid prescriptions 90-180 days after their surgical procedure. The incidence in a nonoperative control cohort was 0.4% (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jun 21;152[6]:e170504). Notably, this prolonged use was greatest in patients with prior pain conditions, substance abuse, and mental health disorders – a finding that may have implications for the counseling we provide prior to surgery.

It’s not clear what the optimal analgesic regimen is for minimally invasive or other gynecologic surgeries. What is clearly recommended, however, is that the approach be multifaceted. In our practice, we believe that the preoperative use of acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib plays an important role in reducing postoperative pain and opioid use. But we also have striven to create a practice-wide culture shift (throughout the operating and recovery rooms), for instance, that encourages using the least amounts of narcotics possible and using the shortest-acting formulations possible.

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are also often part of ERAS protocols; they have been shown in at least two randomized controlled trials of abdominal hysterectomy to reduce intraoperative fentanyl requirements and to reduce immediate postoperative pain scores and postoperative morphine requirements (Anesth Analg. 2008 Dec;107[6]:2056-60; J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Jul-Sep;30[3]:391-6).

More recently, liposomal bupivacaine, which is slowly released over several days, has gained traction as a substitute for standard bupivacaine and other agents in TAP blocks. In one recent retrospective study, abdominal incision infiltration with liposomal bupivacaine was associated with less opioid use (with no change in pain scores), compared with bupivacaine hydrochloride after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128[5]:1009-17). It’s significantly more expensive, however, making it likely that the formulation is being used more judiciously in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery than in open surgeries.

Because of costs, we currently are restricted to using liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries only. In our practice, the single 20 mL vial (266 mg of liposomal bupivacaine) is diluted with 20 mL of normal saline, but it can be further diluted without loss of efficacy. With a 16-gauge needle, the liposomal bupivacaine is distributed across the incisions (usually 20 mL in the umbilicus with a larger incision and 10 mL in each of the two lateral incisions). Patients are counseled that they may have more discomfort after 3 days, but by this point most are mobile and feeling relatively well with a combination of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

With growing visibility of the problem of narcotic dependence in the United States, patients seem increasingly receptive and even eager to limit or avoid the use of opioids. Patients should be counseled that minimizing or avoiding opioids may also speed recovery. Narcotics cause gut motility to slow down, which may hinder mobilization. Early mobilization (within 24 hours) is among the enhanced recovery elements that the ERAS Society guidelines say is “of particular value” for minimally invasive surgery, along with maintenance of normothermia and normovolemia with maintenance of adequate cardiac output.

Selecting Steps

Our practice is also trying to reduce preoperative bowel preparation and preoperative fasting, both of which have been found to be stressful for the body without evidence of benefit. These practices can lead to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are associated with increased morbidity and length of stay.

It is now recommended that clear fluids be allowed up to 2 hours before surgery and solids up to 6 hours before. Some health systems and practices also recommend presurgical carbohydrate loading (for example, 10 ounces of apple juice 2 hours before surgery) – another small change on the ERAS menu – to further reduce postoperative insulin resistance and help the body cope with its stress response to surgery.

Along with nutritional changes are also various measures aimed at optimizing the body’s functionality before surgery (“prehabilitation”), from walking 30 minutes a day to abstaining from alcohol for patients who drink heavily.

Throughout the country, enhanced recovery protocols are taking shape in gynecologic surgery. ERAS was featured in an aptly titled panel session at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists: “Outpatient Hysterectomy, ERAS, and Same-Day Discharge: The Next Big Thing in Gyn Surgery.” Others are applying ERAS to scheduled cesarean sections. And in our practice, I believe that if we continue making small changes, we will reach our goal of opioid-free recoveries and a better surgical experience for our patients.

Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is an associate of the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

“Enhanced Recovery After Surgery” (ERAS) practices and protocols have been increasingly refined and adopted for the field of gynecology, and there is hope among gynecologic surgeons – and some recent evidence – that, with the ERAS movement, we are improving patient recoveries and outcomes and minimizing the need for opioids.

This applies not only to open surgeries but also to the minimally invasive procedures that already are prized for significant reductions in morbidity and length of stay. The overarching and guiding principle of ERAS is that any surgery – whether open or minimally invasive, major or minor – places stress on the body and is associated with risks and morbidity.

Enhanced recovery protocols are multidisciplinary, perioperative approaches designed to lessen the body’s stress response to surgery. The protocols and pathways offer us a menu of small changes that, in the aggregate, can lead to large and demonstrable benefits – especially when these small changes are chosen across the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative arenas and then standardized in one’s practice. Among the major components of ERAS practices and protocols are limiting preoperative fasting, employing multimodal analgesia, encouraging early ambulation and early postsurgical feeding, and creating culture shift that includes greater emphasis on patient expectations.

In our practice, we are incorporating ERAS practices not only in hopes of reducing the stress of all surgeries before, during, and after, but also with the goal of achieving a postoperative opioid-free hysterectomy, myomectomy, and extensive endometriosis surgery. (All of our advanced procedures are performed laparoscopically or robotically.)

Over the past 7 or so years, we have adopted a multimodal approach to pain control that includes a bundle of preoperative analgesics – acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib (we call it “TLC” for Tylenol, Lyrica, and Celebrex) – and the use of liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries. We are now turning toward ERAS nutritional changes, most of which run counter to traditional paradigms for surgical care. And in other areas, such as dedicated preoperative counseling, we continue to refine and improve our practices.

Improved Outcomes

The ERAS mindset notably intersected gynecology with the publication in 2016 of a two-part series of guidelines for gynecology/oncology surgery from the ERAS Society. The 8-year-old society has its roots in a study group of European surgeons and others who decided to examine surgical practices and the concept of multimodal surgical care put forth in the 1990s by Henrik Kehlet, MD, PhD, then a professor at the University of Copenhagen.

The first set of recommendations addressed pre- and intraoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22), and the second set addressed postoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32). Similar evidence-based recommendations were previously written for colonic resections, rectal and pelvic surgery, and other surgical specialties.

Most of the published outcomes of enhanced recovery protocols come from colorectal surgery. As noted in the ERAS Society gynecology/oncology guidelines, the benefits include an average reduction in length of stay of 2.5 days and a decrease in complications by as much as 50%.

There is growing evidence, however, that ERAS programs are also beneficial for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, and outcomes from gynecology – including minimally invasive surgery – are also being reported.

For instance, a retrospective case-control study of 55 consecutive gynecologic oncology patients treated at the University of California, San Francisco, with laparoscopic or robotic surgery and an enhanced recovery pathway – and 110 historical control patients matched on the basis of age and surgery type – found significant improvements in recovery time, decreased pain despite reduced opioid use, and overall lower hospital costs (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;128[1]:138-44).

The enhanced recovery pathway included patient education, multimodal antiemetics, multimodal analgesia, and balanced fluid administration. Early catheter removal, ambulation, and feeding were also components. Analgesia included routine preoperative gabapentin, diclofenac, and acetaminophen; routine postoperative gabapentin, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen; and transversus abdominis plane blocks in 32 of the ERAS patients.

ERAS patients were significantly more likely to be discharged on day 1 (91%, compared with 60% in the control group). Opioid use decreased by 30%, and pain scores on postoperative day 1 were significantly lower.

Another study looking at the effect of enhanced recovery implementation in gynecologic surgeries at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, (gynecologic oncology, urogynecology, and general gynecology) similarly reported benefits for vaginal and minimally invasive procedures, as well as for open procedures (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128[3]:457-66).

In the minimally invasive group, investigators compared 324 patients before ERAS implementation with 249 patients afterward and found that the median length of stay was unchanged (1 day). However, intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption decreased significantly and – even though actual pain scores improved only slightly – patient satisfaction scores improved markedly among post-ERAS patients. Patients gave higher marks, for instance, to questions regarding pain control (“how well your pain was controlled”) and teamwork (“staff worked together to care for you”).

Reducing Opioids

New opioid use that persists after a surgical procedure is a postsurgical complication that we all should be working to prevent. It has been estimated that 6% of surgical patients – even those who’ve had relatively minor surgical procedures – will become long-term opioid users, developing a dependence on the drugs prescribed to them for postsurgical pain.

This was shown last year in a national study of insurance claims data from between 2013 and 2014; investigators identified adults without opioid use in the year prior to surgery (including hysterectomy) and found that 5.9%-6.5% were filling opioid prescriptions 90-180 days after their surgical procedure. The incidence in a nonoperative control cohort was 0.4% (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jun 21;152[6]:e170504). Notably, this prolonged use was greatest in patients with prior pain conditions, substance abuse, and mental health disorders – a finding that may have implications for the counseling we provide prior to surgery.

It’s not clear what the optimal analgesic regimen is for minimally invasive or other gynecologic surgeries. What is clearly recommended, however, is that the approach be multifaceted. In our practice, we believe that the preoperative use of acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib plays an important role in reducing postoperative pain and opioid use. But we also have striven to create a practice-wide culture shift (throughout the operating and recovery rooms), for instance, that encourages using the least amounts of narcotics possible and using the shortest-acting formulations possible.

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are also often part of ERAS protocols; they have been shown in at least two randomized controlled trials of abdominal hysterectomy to reduce intraoperative fentanyl requirements and to reduce immediate postoperative pain scores and postoperative morphine requirements (Anesth Analg. 2008 Dec;107[6]:2056-60; J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Jul-Sep;30[3]:391-6).

More recently, liposomal bupivacaine, which is slowly released over several days, has gained traction as a substitute for standard bupivacaine and other agents in TAP blocks. In one recent retrospective study, abdominal incision infiltration with liposomal bupivacaine was associated with less opioid use (with no change in pain scores), compared with bupivacaine hydrochloride after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128[5]:1009-17). It’s significantly more expensive, however, making it likely that the formulation is being used more judiciously in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery than in open surgeries.

Because of costs, we currently are restricted to using liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries only. In our practice, the single 20 mL vial (266 mg of liposomal bupivacaine) is diluted with 20 mL of normal saline, but it can be further diluted without loss of efficacy. With a 16-gauge needle, the liposomal bupivacaine is distributed across the incisions (usually 20 mL in the umbilicus with a larger incision and 10 mL in each of the two lateral incisions). Patients are counseled that they may have more discomfort after 3 days, but by this point most are mobile and feeling relatively well with a combination of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

With growing visibility of the problem of narcotic dependence in the United States, patients seem increasingly receptive and even eager to limit or avoid the use of opioids. Patients should be counseled that minimizing or avoiding opioids may also speed recovery. Narcotics cause gut motility to slow down, which may hinder mobilization. Early mobilization (within 24 hours) is among the enhanced recovery elements that the ERAS Society guidelines say is “of particular value” for minimally invasive surgery, along with maintenance of normothermia and normovolemia with maintenance of adequate cardiac output.

Selecting Steps

Our practice is also trying to reduce preoperative bowel preparation and preoperative fasting, both of which have been found to be stressful for the body without evidence of benefit. These practices can lead to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are associated with increased morbidity and length of stay.

It is now recommended that clear fluids be allowed up to 2 hours before surgery and solids up to 6 hours before. Some health systems and practices also recommend presurgical carbohydrate loading (for example, 10 ounces of apple juice 2 hours before surgery) – another small change on the ERAS menu – to further reduce postoperative insulin resistance and help the body cope with its stress response to surgery.

Along with nutritional changes are also various measures aimed at optimizing the body’s functionality before surgery (“prehabilitation”), from walking 30 minutes a day to abstaining from alcohol for patients who drink heavily.

Throughout the country, enhanced recovery protocols are taking shape in gynecologic surgery. ERAS was featured in an aptly titled panel session at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists: “Outpatient Hysterectomy, ERAS, and Same-Day Discharge: The Next Big Thing in Gyn Surgery.” Others are applying ERAS to scheduled cesarean sections. And in our practice, I believe that if we continue making small changes, we will reach our goal of opioid-free recoveries and a better surgical experience for our patients.

Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is an associate of the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Protocols to reduce opioid use and shorten length of stay

While originally pioneered by European anesthesiologists and surgeons in Europe in the 1990s, enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs, also known as enhanced recovery protocols or fast-track surgery, have now gained popularity across the surgical spectrum within the United States. The goal of these programs is to utilize multidisciplinary and multimodal interventions to minimize the physiologic changes associated with surgery and thereby enhance the perioperative experience – reduced morbidity and mortality, shorter length of stay, less postoperative opioid use, and faster resumption to normal activity, at a decreased cost of care.

1. Enhanced patient education, including managing expectations.

2. Decreased perioperative fasting periods.

3. Blood volume and temperature maintenance intraoperatively.

4. Postoperative mobilization early and often.

5. Multimodal pain relief and nausea/vomiting prophylaxis.

6. Use of postoperative drains and catheters only as long as required.

Today, I have asked Kirsten Sasaki, MD, to discuss some of these ERAS concepts. I have asked Dr. Sasaki to especially focus on decreasing opioid utilization. For a thorough discussion on ERAS recommendations using an evidence-based approach, one can review two excellent papers by Nelson et al. (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22; Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32).

Dr. Sasaki completed her internship and residency at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. Dr. Sasaki then went on to become our second fellow at the Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery in affiliation with AAGL and Society of Reproductive Surgeons at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. As a Fellow, Dr. Sasaki was recognized for her excellent teaching and research capabilities. Ultimately, however, it was her tremendous surgical skills and surgical sense that led me to invite her to join my practice in 2014.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

While originally pioneered by European anesthesiologists and surgeons in Europe in the 1990s, enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs, also known as enhanced recovery protocols or fast-track surgery, have now gained popularity across the surgical spectrum within the United States. The goal of these programs is to utilize multidisciplinary and multimodal interventions to minimize the physiologic changes associated with surgery and thereby enhance the perioperative experience – reduced morbidity and mortality, shorter length of stay, less postoperative opioid use, and faster resumption to normal activity, at a decreased cost of care.

1. Enhanced patient education, including managing expectations.

2. Decreased perioperative fasting periods.

3. Blood volume and temperature maintenance intraoperatively.

4. Postoperative mobilization early and often.

5. Multimodal pain relief and nausea/vomiting prophylaxis.

6. Use of postoperative drains and catheters only as long as required.

Today, I have asked Kirsten Sasaki, MD, to discuss some of these ERAS concepts. I have asked Dr. Sasaki to especially focus on decreasing opioid utilization. For a thorough discussion on ERAS recommendations using an evidence-based approach, one can review two excellent papers by Nelson et al. (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22; Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32).

Dr. Sasaki completed her internship and residency at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. Dr. Sasaki then went on to become our second fellow at the Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery in affiliation with AAGL and Society of Reproductive Surgeons at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. As a Fellow, Dr. Sasaki was recognized for her excellent teaching and research capabilities. Ultimately, however, it was her tremendous surgical skills and surgical sense that led me to invite her to join my practice in 2014.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

While originally pioneered by European anesthesiologists and surgeons in Europe in the 1990s, enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs, also known as enhanced recovery protocols or fast-track surgery, have now gained popularity across the surgical spectrum within the United States. The goal of these programs is to utilize multidisciplinary and multimodal interventions to minimize the physiologic changes associated with surgery and thereby enhance the perioperative experience – reduced morbidity and mortality, shorter length of stay, less postoperative opioid use, and faster resumption to normal activity, at a decreased cost of care.

1. Enhanced patient education, including managing expectations.

2. Decreased perioperative fasting periods.

3. Blood volume and temperature maintenance intraoperatively.

4. Postoperative mobilization early and often.

5. Multimodal pain relief and nausea/vomiting prophylaxis.

6. Use of postoperative drains and catheters only as long as required.

Today, I have asked Kirsten Sasaki, MD, to discuss some of these ERAS concepts. I have asked Dr. Sasaki to especially focus on decreasing opioid utilization. For a thorough discussion on ERAS recommendations using an evidence-based approach, one can review two excellent papers by Nelson et al. (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22; Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32).

Dr. Sasaki completed her internship and residency at Tufts Medical Center, Boston. Dr. Sasaki then went on to become our second fellow at the Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery in affiliation with AAGL and Society of Reproductive Surgeons at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. As a Fellow, Dr. Sasaki was recognized for her excellent teaching and research capabilities. Ultimately, however, it was her tremendous surgical skills and surgical sense that led me to invite her to join my practice in 2014.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Clinical rule decreased pediatric trauma CT scans

ORLANDO – A according to a study presented at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

With values for five clinical variables, the prediction rule would eliminate the need to subject some patients to unwarranted radiation exposure, which has become a growing health and financial concern for medical institutions.

“CT utilization rates in pediatric blunt trauma are very high, at a rate of 40%-60%, despite a relatively low incidence of intra-abdominal injury after abdominal trauma,” according to presenter Chase A. Arbra, MD, of the department of surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. “With increasing concerns regarding the cost and radiation exposure in children, our group is focusing on research to safely avoid these unnecessary scans.”

The rule, developed by the Pediatric Surgery Research Collaborative (PedSRC), evaluates abdominal wall trauma and tenderness, complaint of abdominal pain, aspartate aminotransferase level greater than 200 U/L, abnormal pancreatic enzymes, and abnormal chest x-rays to determine a patient’s risk of having an intra-abdominal injury (IAI). If none of the five variables in a patient is abnormal, the finding is considered negative and the patient is considered to be at very low risk for having an IAI or an IAI requiring acute intervention (IAI-I).

Investigators studied 2,435 pediatric blunt trauma patients with all five clinical variables documented within 6 hours of arrival, using data gathered from the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network.

Patients were an average of 9.4 years old, with an IAI rate of 9.7% (n = 235) and an IAI-I rate of 2.5% (n = 60); 61.1% of the patients had a CT scan.

Prediction sensitivity of the method was 97.5% for IAI and 100% for IAI-I, said Dr. Arbra. Negative predictive value for the model was 99.3% for IAI and 100% for IAI-I.

Patients who were found to have aspartate aminotransferase level greater than 200 U/L were at the highest risk of IAI (52.6%) and IAI-I (11.9%), according to investigators. One-third of the test population was found to be at very low risk after using the prediction model, according to Dr. Arbra, with 46.8% of them still undergoing a CT scan. Of those tested, six patients had IAI that was not predicted by the model, three of whom were intubated. Because CT scans were not required and there was no follow-up after discharge, investigators are not able to determine if any minor IAI was missed.

Despite these limitations, the highly sensitive rule shows great promise, according to Dr. Arbra.

“Patients with 0-5 variables, even patients who were involved in a high impact mechanism, could potentially forgo CT scans safely.”

A closer look at the 26 patients who only had abdominal pain showed that only 1 had IAI, suggesting that patients with only abdominal pain could be safely observed with only serial exams, according to Dr. Arbra.

Investigators plan to conduct a prospective study that will include older patients.

Dr. Arbra concluded, “The rule could potentially help centers to determine who could avoid imaging prior to transfer and potentially could one day be used to see who could be discharged.”

Dr. Arbra reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com