User login

Outcomes After Endoscopic Dilation of Laryngotracheal Stenosis: An Analysis of ACS-NSQIP

From the Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL (Mr. Bavishi, Dr. Lavin), the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Boss), Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC (Dr. Shah), and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL (Dr. Lavin).

Abstract

- Background: Endoscopic management of pediatric subglottic stenosis is common; however, no multiinstitutional studies have assessed its perioperative outcomes. The American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program – Pediatric (ACS-NSQIP-P) represents a source of such data.

- Objective: To investigate 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation of the pediatric airway and to compare these outcomes to those seen with open reconstruction techniques.

- Methods: Current procedural terminology (CPT) codes were queried for endoscopic or open airway reconstruction in the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P Public Use File (PUF). Demographics and 30-day events were abstracted to compare open to endoscopic techniques and to assess for risk factors for varied outcomes after endoscopic dilation. Outcome measures included length of stay (LOS), 30-day rates of reintubation, readmission, and reoperation.

- Results: 171 endoscopic and 116 open procedures were identified. Mean age at endoscopic and open procedures was 4.1 (SEM = 0.37) and 5.4 years (SEM = 0.40). Mean LOS was shorter after endoscopic procedures (5.5 days, SEM = 1.13 vs. 11.3 days SEM = 1.01, P < 0.001). Open procedures had higher rates of reintubation (OR = 7.41, P = 0.026) and reoperation (OR = 3.09, P = 0.009). In patients undergoing endoscopic dilation, children < 1 year were more likely to require readmission (OR = 4.21, P = 0.03) and reoperation (OR = 4.39, P = 0.03) when compared with older children.

- Conclusion: Open airway reconstruction is associated with longer LOS and increased reintubations and reoperations, suggesting a possible opportunity to improve value in health care in the appropriately selected patient. Reoperations and readmissions following endoscopic dilation are more prevalent in children younger than 1 year.

Keywords: airway stenosis; subglottic stenosis; endoscopic dilation; pediatrics; outcomes.

Historically, pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis was managed using open reconstruction techniques, including laryngoplasty, tracheal resection, and cervical tracheoplasty. Initial reports of endoscopic dilation were described in the 1980s as a means to salvage re-stenosis after open reconstruction [1]. Currently, primary endoscopic dilation has become commonplace in otolaryngology due to its less invasive nature as well as—in cases of balloon dilation—minimization of tissue damage [2]. The advancements made in endoscopic balloon dilation have reduced the frequency with which open reconstruction is performed.

Systematic reviews and case series investigating endoscopic dilation indicate a 70% to 80% success rate in preventing future open surgery or tracheostomy [2–5]. While increased severity of stenosis has been associated with poorer outcomes in endoscopic procedures, few other risk factors that influence surgical success have been identified [4,5]. In a single study in the adult literature, open surgical management of idiopathic subglottic stenosis was associated with improved outcomes when compared to endoscopic techniques [5]. Such findings suggest a need to identify these factors for the purpose of optimizing clinical decision-making.

As laryngotracheal stenosis is rare, postoperative outcomes and risk factors are best identified on a multiinstitutional level. Due to its participation from 80 hospitals and its accurate and reliable reporting of both demographic and risk-stratified 30-day outcomes data, the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program – Pediatric (ACS NSQIP-P) provides such a platform [6–8]. Thirty-day outcomes and risk factors for open reconstruction utilizing the ACS NSQIP-P database have previously been reported; however, no such outcomes for endoscopic dilation have been described, and no comparison between endoscopic and open procedures has been made [9]. The purpose of this study was to utilize the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P database to investigate 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation of the pediatric airway and to compare these outcomes to open reconstruction techniques. Secondarily, we aimed to determine if any demographic factors or medical comorbidities are associated with varied outcomes in endoscopic reconstruction. While these data reflect safety and quality of this procedure in the United States, findings may potentially be applied across international settings.

Methods

Data Source

Data was obtained from the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P Public Use File (PUF). Due to the de-identified and public nature of these data, this research was exempt from review by the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago review board. Data collection methods for ACS-NSQIP-P have previously been described [10]. In brief, data was collected from 80 hospitals on approximately 120 preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables. Cases are systematically sampled on an 8-day cycle basis, where the first 35 cases meeting the inclusion criteria in each hospital in each cycle are submitted to ACS-NSQIP-P.

Variables and Outcomes

Airway procedures for endoscopic dilations and open reconstructions were obtained by CPT code. Endoscopic dilations (CPT 31528) were compared to open reconstructions, which included laryngoplasty (31580, 31582), cervical tracheoplasty (31750), cricoid split (31587), and tracheal resection (31780). Demographic variables included age, sex, race, and history of prematurity. Presence of specific comorbid diseases were also collected and tested for significance.

Dependent outcomes of interest were unplanned 30-day postoperative events grouped as reoperation, unplanned readmission, and postoperative reintubation. In the case of endoscopic procedures, the presence of salvage open reconstruction or tracheostomy within 30 days of surgery was also recorded. Length of stay (LOS) after the procedure was collected. Specific postoperative complications and reasons for readmission were recorded within the limitations of data available in the PUF.

Analysis

Analysis was performed using descriptive statistics and frequency analysis where appropriate. Chi-square analysis was used to compare adverse events between open and endoscopic procedures. Logistic regression with calculation of odds ratio (OR) was performed to determine predictive factors for reoperation, readmission, and reintubation in all pediatric airway reconstructive procedures in adjusted and unadjusted models. T-test and linear regression was performed on the continuous outcome of length of stay. For all analyses, a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All variable recoding and statistical analyses were performed in SAS/STAT software (Cary, NC).

Results

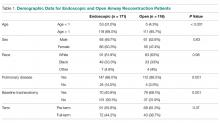

A total of 84,056 pediatric procedures were extracted from the 2015 NSQIP-P PUFs. Using the above CPT codes, 171 endoscopic dilations and 116 open airway reconstructions were identified, with patient age ranging from 0 days to 17.6 years. Average age of patients undergoing endoscopic dilation and open reconstruction was 4.1 and 5.4 years, respectively (Table 1).

Potential confounders were tested with univariate logistic regression to determine if they had a significant impact on readmission, reintubation, or reoperation rates. These variables (Table 2)

In patients undergoing endoscopic dilation, average length of stay was 5.5 days (SEM = 1.13), with 79 (48.5%) patients having a length of stay of zero days. Of all patients who had endoscopic dilations, 70 (40.1%) had a pre-existing tracheostomy and these accounted for the majority (73%) of patients who had zero days as their LOS. LOS after endoscopic management was significantly shorter than the mean of 11.3 days (SEM = 1.01) reported in those undergoing open reconstruction (P < 0.001).

With respect to 30-day adverse events, 2 patients in the endoscopic group (1.1%) required reintubation. Thirteen endoscopic dilation cases (7.6%) had an unplanned readmission, four (2.3%) of which were associated with reoperation within 30 days of the primary surgical procedure. There were 9 other reoperations unassociated with unplanned readmission. Three of these reoperations were due to failed endoscopic dilations, resulting in 2 tracheostomies and one open airway reconstruction. There was one patient death, in a 0-day old with tetralogy of Fallot, trachea-esophageal fistula, and ventilator dependence who underwent emergent endoscopic dilation and died the same day.

Open procedures were associated with 11 unplanned readmissions (9.5%), 7 re-intubations (6%) and 18 reoperations (15.5%). Of patents undergoing reoperation, one patient undergoing open reconstruction underwent tracheostomy within 30 days of surgery.

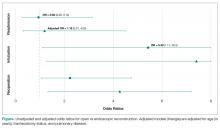

When comparing open reconstruction to endoscopic dilation, there was a significant increase in reintubation (OR = 7.41, P = 0.026) and reoperation (OR = 3.09, P = 0.009) for open procedures, even with adjustment for age, tracheostomy status, and pulmonary disease. There was no significant difference between the two for unplanned readmissions (OR = 1.19, P = 0.79) (Figure

Younger age was also found to be significantly associated with reoperation rates, in an adjusted logistic model that accounted for tracheostomy status, type of surgery, and pulmonary disease. Per year of life, younger children had higher reoperation rates than older children (OR = 1.91, P = 0.017). When endoscopic dilation was individually examined, children younger than 1 year of age were more likely to undergo reoperation after an endoscopic dilation than children older than 1 (OR = 4.39, P = 0.03). Children under age 1 were also more likely to have an unplanned readmission after an endoscopic dilation (OR = 4.21, P = 0.03). The relationship between age and re-intubation was not significant (OR = 0, P = 0.95). For open reconstruction, this age dichotomization was not associated with any increased reoperation (OR = 2.3, P = 0.52), readmission (OR = 0, P = 0.97), or reintubation (OR = 0, P = 0.94).

T-test analysis was performed to determine if children < 1 year old also had significantly longer hospital stays after endoscopic dilation than older children (mean 14.1 days vs 1.9 days, P < 0.001). This relationship held true in a linear regression after adjustment for pulmonary disease and tracheostomy, with length of stay decreasing by 0.48 days per year of life (P = 0.03). For endoscopic dilations, the same relationship held true, where length of stay decreased by 0.75 days per year of life.

Discussion

Endoscopic dilation for primary management of pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis has become commonplace. Despite this, outcomes of this procedure have only been described in case series and meta-analyses [2–5]. The relative rarity of pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis suggests the need for large, multi-institutional data for purposes of patient selection and medical decision-making.

This study utilized the ACS-NSQIP-Pediatric database to highlight 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation and to compare these outcomes to those of open airway reconstruction procedures. The ACS-NSQIP database has been endorsed by multiple organizations, including the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Joint Commission, and the American Medical Association. It has been shown to have higher sensitivity and a lower false-positive rate when compared to administrative data, in part due to data collection from trained personnel [11]. Furthermore, ACS-NSQIP use has the additional benefit of reporting an unplanned admission—a feature unavailable in review of claims data [12].

With respect to adverse events, our study demonstrates that endoscopic dilation is associated with an equally high rate of unplanned readmission when compared to open reconstruction. The high prevalence of comorbid disease such as chronic lung disease (32% of endoscopic dilation and 43% of open reconstruction) can account for some of the morbidity associated with any airway procedures.

Despite high rates of unplanned readmission, patients undergoing endoscopic dilation were less likely to have reoperations within 30 days of initial surgery when compared to those undergoing open reconstruction. While differences in disease severity may be partially responsible for this difference in the reoperation rate, this finding is notable given the health care costs associated with multiple operations as well as safety concerns with multiple anesthetics in the very young [13,14].

The ACS-NSQIP platform does not distinguish unplanned from planned reoperations. In the setting of airway surgery, where multiple planned reoperations are commonplace, this metric is a suboptimal stand-alone indicator of adverse outcomes. Other markers available in the database—such as reintubations and performance of tracheostomy or open airway reconstruction within 30-days of surgery—are more indicative of surgical outcome in the setting of airway surgery. We found that both reintubations and salvage open reconstruction within 30-days were rare. It should be noted that the ACS-NSQIP data does not report any events occurring outside of the 30-day postoperative period, representing potential limitation of the use of this database. As was previously advocated by Roxbury and colleagues, procedure/subspecialty specific outcome data collection would also improve outcome analysis of airway and other otolaryngologic procedures [9]. In the setting of airway reconstruction, this would include data pertaining to Cotton-Meyer grading systems well as postoperative voice and swallow outcomes.

In addition to safety profile, endoscopic procedures were associated with shorter LOS when compared with open reconstruction, representing another potential source of cost savings with this less invasive method. This is especially significant given that open reconstruction patients spend much of their inpatient stay in an ICU setting. In patients who are candidates for endoscopic procedures, this lower-risk, lower-cost profile of endoscopic dilation has the opportunity to improve value in health care and may be the source of future improvement initiatives.

In addition to comparing overall outcomes between endoscopic and open management of laryngotracheal stenosis, our study aimed to identify factors that were associated with varied outcomes in patients undergoing primary endoscopic dilation. We found that children younger than 1 year of age were 5.8 times more likely to undergo an unplanned reoperation after an endoscopic dilation than children over 1 year. A similar finding was reported in open airway surgeries, with increased reoperation rates in children < 3 years old [9]. The justification of a dichotomization at 1 year was made as expert opinion recognizes that the infant airway is less forgiving to intervention given its small size. Young age was also a factor in prolonged LOS as was determined by linear regression. It is likely that this increased LOS may be in part due to associations of young age and the neonatal ICU population. One must balance the increased risk of surgery in the young with that of tracheostomy, which has a published complication rate of 18% to 50% and direct mortality rate of 1% to 2% in the pediatric population [15–18]. Understanding these relative risks may help guide the airway surgeon in preoperative counseling with families and medical decision-making.

As discussed above, the limitation of data to a 30-day period is a relative weakness of ACS-NSQIP database use for studies of airway reconstruction, as the ultimate outcome—a stable, decannulated airway—may occur outside of this time period. As many quality metrics utilize data from the 30-day postoperative period, knowledge of these outcomes remains valuable in surgical decision-making. Ultimately, collection of data in a large, long-term dataset would allow broader generalizations to be made about the differences between open and endoscopic procedures and would also give a more comprehensive picture of the outcomes of endoscopic dilation.

In conclusion, this study is the first to analyze 30-day postoperative outcomes in pediatric endoscopic airway dilations using data aggregated by ACS-NSQIP from institutions across the United States. This data indicates that endoscopic airway dilation is a relatively safe procedure, especially compared with open reconstruction; however, additional data on disease severity and other outcomes is necessary to draw final conclusions of superiority of technique. Future improvement initiatives could be aimed at the impact of this lower-risk, lower-cost procedure in the appropriately selected patient. Outcomes of endoscopic dilation are poorer in those less than 1 year of age, as they are associated with increased reoperation rates and increased length of stay compared to older children. One must balance these risks in the very young with the risks associated with tracheostomy and other alternative airway management modalities.

Note: This work was presented in a paper at the AAO-HNS 2017 meeting, Chicago, IL, 10 Sep 2017.

Corresponding author: Jennifer Lavin, MD, MS, 225 E Chicago Ave., Box 25, Chicago, IL 60611, JLavin@luriechildrens.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Cohen MD, Weber TR, Rao CC. Balloon dilatation of tracheal and bronchial stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984;142:477–8.

2. Chueng K, Chadha NK. Primary dilatation as a treatment for pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013;77:623–8.

3. Hautefort C, Teissier N, Viala P, Van Den Abbeele T. Balloon dilation laryngoplasty for subglottic stenosis in children: eight years’ experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;138:235–40.

4. Lang M, Brietzke SE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic balloon dilation of pediatric subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;150:174–9.

5. Maresh A, Preciado DA, O’Connell AP, Zalzal GH. A comparative analysis of open surgery vs endoscopic balloon dilation for pediatric subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:901–5.

6. Gelbard A, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J, et al. Disease homogeneity and treatment heterogeneity in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 2016;126:1390–6.

7. ACS-NSQIP. ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program® (ACS NSQIP®). 2017. Available at: http://site.acsnsqip.org/program-specifics/scr-training-and-resources. Accessed June 2 2017.

8. Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:6–16.

9. Roxbury CR, Jatana KR, Shah RK, Boss EF. Safety and postoperative adverse events in pediatric airway reconstruction: Analysis of ACS-NSQIP-P 30-day outcomes. Laryngoscope 2017;127:504–8.

10. Raval MV, Dillon PW, Bruny JL, et al. Pediatric American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: feasibility of a novel, prospective assessment of surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46:115–21.

11. Lawson EH, Louie R, Zingmond DS, et al. A comparison of clinical registry versus administrative claims data for reporting of 30-day surgical complications. Ann Surg 2012;256:973–81.

12. Sellers MM, Merkow RP, Halverson A, et al. Validation of new readmission data in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:420–7.

13. Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci 2003;23:876–82.

14. Patel P, Sun L. Update on neonatal anesthetic neurotoxicity: insight into molecular mechanisms and relevance to humans. Anesthesiology 2009;110:703–8.

15. Crysdale WS, Feldman RI, Naito K. Tracheotomies: a 10-year experience in 319 children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1988;97(5 Pt 1):439–43.

16. Goldenberg D, Ari EG, Golz A, et al. Tracheotomy complications: a retrospective study of 1130 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:495–500.

17. Mahadevan M, Barber C, Salkeld L, et al N. Pediatric tracheotomy: 17 year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71:1829–35.

18. Ozmen S, Ozmen OA, Unal OF. Pediatric tracheotomies: a 37-year experience in 282 children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009;73:959–61.

From the Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL (Mr. Bavishi, Dr. Lavin), the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Boss), Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC (Dr. Shah), and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL (Dr. Lavin).

Abstract

- Background: Endoscopic management of pediatric subglottic stenosis is common; however, no multiinstitutional studies have assessed its perioperative outcomes. The American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program – Pediatric (ACS-NSQIP-P) represents a source of such data.

- Objective: To investigate 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation of the pediatric airway and to compare these outcomes to those seen with open reconstruction techniques.

- Methods: Current procedural terminology (CPT) codes were queried for endoscopic or open airway reconstruction in the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P Public Use File (PUF). Demographics and 30-day events were abstracted to compare open to endoscopic techniques and to assess for risk factors for varied outcomes after endoscopic dilation. Outcome measures included length of stay (LOS), 30-day rates of reintubation, readmission, and reoperation.

- Results: 171 endoscopic and 116 open procedures were identified. Mean age at endoscopic and open procedures was 4.1 (SEM = 0.37) and 5.4 years (SEM = 0.40). Mean LOS was shorter after endoscopic procedures (5.5 days, SEM = 1.13 vs. 11.3 days SEM = 1.01, P < 0.001). Open procedures had higher rates of reintubation (OR = 7.41, P = 0.026) and reoperation (OR = 3.09, P = 0.009). In patients undergoing endoscopic dilation, children < 1 year were more likely to require readmission (OR = 4.21, P = 0.03) and reoperation (OR = 4.39, P = 0.03) when compared with older children.

- Conclusion: Open airway reconstruction is associated with longer LOS and increased reintubations and reoperations, suggesting a possible opportunity to improve value in health care in the appropriately selected patient. Reoperations and readmissions following endoscopic dilation are more prevalent in children younger than 1 year.

Keywords: airway stenosis; subglottic stenosis; endoscopic dilation; pediatrics; outcomes.

Historically, pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis was managed using open reconstruction techniques, including laryngoplasty, tracheal resection, and cervical tracheoplasty. Initial reports of endoscopic dilation were described in the 1980s as a means to salvage re-stenosis after open reconstruction [1]. Currently, primary endoscopic dilation has become commonplace in otolaryngology due to its less invasive nature as well as—in cases of balloon dilation—minimization of tissue damage [2]. The advancements made in endoscopic balloon dilation have reduced the frequency with which open reconstruction is performed.

Systematic reviews and case series investigating endoscopic dilation indicate a 70% to 80% success rate in preventing future open surgery or tracheostomy [2–5]. While increased severity of stenosis has been associated with poorer outcomes in endoscopic procedures, few other risk factors that influence surgical success have been identified [4,5]. In a single study in the adult literature, open surgical management of idiopathic subglottic stenosis was associated with improved outcomes when compared to endoscopic techniques [5]. Such findings suggest a need to identify these factors for the purpose of optimizing clinical decision-making.

As laryngotracheal stenosis is rare, postoperative outcomes and risk factors are best identified on a multiinstitutional level. Due to its participation from 80 hospitals and its accurate and reliable reporting of both demographic and risk-stratified 30-day outcomes data, the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program – Pediatric (ACS NSQIP-P) provides such a platform [6–8]. Thirty-day outcomes and risk factors for open reconstruction utilizing the ACS NSQIP-P database have previously been reported; however, no such outcomes for endoscopic dilation have been described, and no comparison between endoscopic and open procedures has been made [9]. The purpose of this study was to utilize the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P database to investigate 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation of the pediatric airway and to compare these outcomes to open reconstruction techniques. Secondarily, we aimed to determine if any demographic factors or medical comorbidities are associated with varied outcomes in endoscopic reconstruction. While these data reflect safety and quality of this procedure in the United States, findings may potentially be applied across international settings.

Methods

Data Source

Data was obtained from the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P Public Use File (PUF). Due to the de-identified and public nature of these data, this research was exempt from review by the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago review board. Data collection methods for ACS-NSQIP-P have previously been described [10]. In brief, data was collected from 80 hospitals on approximately 120 preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables. Cases are systematically sampled on an 8-day cycle basis, where the first 35 cases meeting the inclusion criteria in each hospital in each cycle are submitted to ACS-NSQIP-P.

Variables and Outcomes

Airway procedures for endoscopic dilations and open reconstructions were obtained by CPT code. Endoscopic dilations (CPT 31528) were compared to open reconstructions, which included laryngoplasty (31580, 31582), cervical tracheoplasty (31750), cricoid split (31587), and tracheal resection (31780). Demographic variables included age, sex, race, and history of prematurity. Presence of specific comorbid diseases were also collected and tested for significance.

Dependent outcomes of interest were unplanned 30-day postoperative events grouped as reoperation, unplanned readmission, and postoperative reintubation. In the case of endoscopic procedures, the presence of salvage open reconstruction or tracheostomy within 30 days of surgery was also recorded. Length of stay (LOS) after the procedure was collected. Specific postoperative complications and reasons for readmission were recorded within the limitations of data available in the PUF.

Analysis

Analysis was performed using descriptive statistics and frequency analysis where appropriate. Chi-square analysis was used to compare adverse events between open and endoscopic procedures. Logistic regression with calculation of odds ratio (OR) was performed to determine predictive factors for reoperation, readmission, and reintubation in all pediatric airway reconstructive procedures in adjusted and unadjusted models. T-test and linear regression was performed on the continuous outcome of length of stay. For all analyses, a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All variable recoding and statistical analyses were performed in SAS/STAT software (Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 84,056 pediatric procedures were extracted from the 2015 NSQIP-P PUFs. Using the above CPT codes, 171 endoscopic dilations and 116 open airway reconstructions were identified, with patient age ranging from 0 days to 17.6 years. Average age of patients undergoing endoscopic dilation and open reconstruction was 4.1 and 5.4 years, respectively (Table 1).

Potential confounders were tested with univariate logistic regression to determine if they had a significant impact on readmission, reintubation, or reoperation rates. These variables (Table 2)

In patients undergoing endoscopic dilation, average length of stay was 5.5 days (SEM = 1.13), with 79 (48.5%) patients having a length of stay of zero days. Of all patients who had endoscopic dilations, 70 (40.1%) had a pre-existing tracheostomy and these accounted for the majority (73%) of patients who had zero days as their LOS. LOS after endoscopic management was significantly shorter than the mean of 11.3 days (SEM = 1.01) reported in those undergoing open reconstruction (P < 0.001).

With respect to 30-day adverse events, 2 patients in the endoscopic group (1.1%) required reintubation. Thirteen endoscopic dilation cases (7.6%) had an unplanned readmission, four (2.3%) of which were associated with reoperation within 30 days of the primary surgical procedure. There were 9 other reoperations unassociated with unplanned readmission. Three of these reoperations were due to failed endoscopic dilations, resulting in 2 tracheostomies and one open airway reconstruction. There was one patient death, in a 0-day old with tetralogy of Fallot, trachea-esophageal fistula, and ventilator dependence who underwent emergent endoscopic dilation and died the same day.

Open procedures were associated with 11 unplanned readmissions (9.5%), 7 re-intubations (6%) and 18 reoperations (15.5%). Of patents undergoing reoperation, one patient undergoing open reconstruction underwent tracheostomy within 30 days of surgery.

When comparing open reconstruction to endoscopic dilation, there was a significant increase in reintubation (OR = 7.41, P = 0.026) and reoperation (OR = 3.09, P = 0.009) for open procedures, even with adjustment for age, tracheostomy status, and pulmonary disease. There was no significant difference between the two for unplanned readmissions (OR = 1.19, P = 0.79) (Figure

Younger age was also found to be significantly associated with reoperation rates, in an adjusted logistic model that accounted for tracheostomy status, type of surgery, and pulmonary disease. Per year of life, younger children had higher reoperation rates than older children (OR = 1.91, P = 0.017). When endoscopic dilation was individually examined, children younger than 1 year of age were more likely to undergo reoperation after an endoscopic dilation than children older than 1 (OR = 4.39, P = 0.03). Children under age 1 were also more likely to have an unplanned readmission after an endoscopic dilation (OR = 4.21, P = 0.03). The relationship between age and re-intubation was not significant (OR = 0, P = 0.95). For open reconstruction, this age dichotomization was not associated with any increased reoperation (OR = 2.3, P = 0.52), readmission (OR = 0, P = 0.97), or reintubation (OR = 0, P = 0.94).

T-test analysis was performed to determine if children < 1 year old also had significantly longer hospital stays after endoscopic dilation than older children (mean 14.1 days vs 1.9 days, P < 0.001). This relationship held true in a linear regression after adjustment for pulmonary disease and tracheostomy, with length of stay decreasing by 0.48 days per year of life (P = 0.03). For endoscopic dilations, the same relationship held true, where length of stay decreased by 0.75 days per year of life.

Discussion

Endoscopic dilation for primary management of pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis has become commonplace. Despite this, outcomes of this procedure have only been described in case series and meta-analyses [2–5]. The relative rarity of pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis suggests the need for large, multi-institutional data for purposes of patient selection and medical decision-making.

This study utilized the ACS-NSQIP-Pediatric database to highlight 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation and to compare these outcomes to those of open airway reconstruction procedures. The ACS-NSQIP database has been endorsed by multiple organizations, including the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Joint Commission, and the American Medical Association. It has been shown to have higher sensitivity and a lower false-positive rate when compared to administrative data, in part due to data collection from trained personnel [11]. Furthermore, ACS-NSQIP use has the additional benefit of reporting an unplanned admission—a feature unavailable in review of claims data [12].

With respect to adverse events, our study demonstrates that endoscopic dilation is associated with an equally high rate of unplanned readmission when compared to open reconstruction. The high prevalence of comorbid disease such as chronic lung disease (32% of endoscopic dilation and 43% of open reconstruction) can account for some of the morbidity associated with any airway procedures.

Despite high rates of unplanned readmission, patients undergoing endoscopic dilation were less likely to have reoperations within 30 days of initial surgery when compared to those undergoing open reconstruction. While differences in disease severity may be partially responsible for this difference in the reoperation rate, this finding is notable given the health care costs associated with multiple operations as well as safety concerns with multiple anesthetics in the very young [13,14].

The ACS-NSQIP platform does not distinguish unplanned from planned reoperations. In the setting of airway surgery, where multiple planned reoperations are commonplace, this metric is a suboptimal stand-alone indicator of adverse outcomes. Other markers available in the database—such as reintubations and performance of tracheostomy or open airway reconstruction within 30-days of surgery—are more indicative of surgical outcome in the setting of airway surgery. We found that both reintubations and salvage open reconstruction within 30-days were rare. It should be noted that the ACS-NSQIP data does not report any events occurring outside of the 30-day postoperative period, representing potential limitation of the use of this database. As was previously advocated by Roxbury and colleagues, procedure/subspecialty specific outcome data collection would also improve outcome analysis of airway and other otolaryngologic procedures [9]. In the setting of airway reconstruction, this would include data pertaining to Cotton-Meyer grading systems well as postoperative voice and swallow outcomes.

In addition to safety profile, endoscopic procedures were associated with shorter LOS when compared with open reconstruction, representing another potential source of cost savings with this less invasive method. This is especially significant given that open reconstruction patients spend much of their inpatient stay in an ICU setting. In patients who are candidates for endoscopic procedures, this lower-risk, lower-cost profile of endoscopic dilation has the opportunity to improve value in health care and may be the source of future improvement initiatives.

In addition to comparing overall outcomes between endoscopic and open management of laryngotracheal stenosis, our study aimed to identify factors that were associated with varied outcomes in patients undergoing primary endoscopic dilation. We found that children younger than 1 year of age were 5.8 times more likely to undergo an unplanned reoperation after an endoscopic dilation than children over 1 year. A similar finding was reported in open airway surgeries, with increased reoperation rates in children < 3 years old [9]. The justification of a dichotomization at 1 year was made as expert opinion recognizes that the infant airway is less forgiving to intervention given its small size. Young age was also a factor in prolonged LOS as was determined by linear regression. It is likely that this increased LOS may be in part due to associations of young age and the neonatal ICU population. One must balance the increased risk of surgery in the young with that of tracheostomy, which has a published complication rate of 18% to 50% and direct mortality rate of 1% to 2% in the pediatric population [15–18]. Understanding these relative risks may help guide the airway surgeon in preoperative counseling with families and medical decision-making.

As discussed above, the limitation of data to a 30-day period is a relative weakness of ACS-NSQIP database use for studies of airway reconstruction, as the ultimate outcome—a stable, decannulated airway—may occur outside of this time period. As many quality metrics utilize data from the 30-day postoperative period, knowledge of these outcomes remains valuable in surgical decision-making. Ultimately, collection of data in a large, long-term dataset would allow broader generalizations to be made about the differences between open and endoscopic procedures and would also give a more comprehensive picture of the outcomes of endoscopic dilation.

In conclusion, this study is the first to analyze 30-day postoperative outcomes in pediatric endoscopic airway dilations using data aggregated by ACS-NSQIP from institutions across the United States. This data indicates that endoscopic airway dilation is a relatively safe procedure, especially compared with open reconstruction; however, additional data on disease severity and other outcomes is necessary to draw final conclusions of superiority of technique. Future improvement initiatives could be aimed at the impact of this lower-risk, lower-cost procedure in the appropriately selected patient. Outcomes of endoscopic dilation are poorer in those less than 1 year of age, as they are associated with increased reoperation rates and increased length of stay compared to older children. One must balance these risks in the very young with the risks associated with tracheostomy and other alternative airway management modalities.

Note: This work was presented in a paper at the AAO-HNS 2017 meeting, Chicago, IL, 10 Sep 2017.

Corresponding author: Jennifer Lavin, MD, MS, 225 E Chicago Ave., Box 25, Chicago, IL 60611, JLavin@luriechildrens.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL (Mr. Bavishi, Dr. Lavin), the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD (Dr. Boss), Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC (Dr. Shah), and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL (Dr. Lavin).

Abstract

- Background: Endoscopic management of pediatric subglottic stenosis is common; however, no multiinstitutional studies have assessed its perioperative outcomes. The American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program – Pediatric (ACS-NSQIP-P) represents a source of such data.

- Objective: To investigate 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation of the pediatric airway and to compare these outcomes to those seen with open reconstruction techniques.

- Methods: Current procedural terminology (CPT) codes were queried for endoscopic or open airway reconstruction in the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P Public Use File (PUF). Demographics and 30-day events were abstracted to compare open to endoscopic techniques and to assess for risk factors for varied outcomes after endoscopic dilation. Outcome measures included length of stay (LOS), 30-day rates of reintubation, readmission, and reoperation.

- Results: 171 endoscopic and 116 open procedures were identified. Mean age at endoscopic and open procedures was 4.1 (SEM = 0.37) and 5.4 years (SEM = 0.40). Mean LOS was shorter after endoscopic procedures (5.5 days, SEM = 1.13 vs. 11.3 days SEM = 1.01, P < 0.001). Open procedures had higher rates of reintubation (OR = 7.41, P = 0.026) and reoperation (OR = 3.09, P = 0.009). In patients undergoing endoscopic dilation, children < 1 year were more likely to require readmission (OR = 4.21, P = 0.03) and reoperation (OR = 4.39, P = 0.03) when compared with older children.

- Conclusion: Open airway reconstruction is associated with longer LOS and increased reintubations and reoperations, suggesting a possible opportunity to improve value in health care in the appropriately selected patient. Reoperations and readmissions following endoscopic dilation are more prevalent in children younger than 1 year.

Keywords: airway stenosis; subglottic stenosis; endoscopic dilation; pediatrics; outcomes.

Historically, pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis was managed using open reconstruction techniques, including laryngoplasty, tracheal resection, and cervical tracheoplasty. Initial reports of endoscopic dilation were described in the 1980s as a means to salvage re-stenosis after open reconstruction [1]. Currently, primary endoscopic dilation has become commonplace in otolaryngology due to its less invasive nature as well as—in cases of balloon dilation—minimization of tissue damage [2]. The advancements made in endoscopic balloon dilation have reduced the frequency with which open reconstruction is performed.

Systematic reviews and case series investigating endoscopic dilation indicate a 70% to 80% success rate in preventing future open surgery or tracheostomy [2–5]. While increased severity of stenosis has been associated with poorer outcomes in endoscopic procedures, few other risk factors that influence surgical success have been identified [4,5]. In a single study in the adult literature, open surgical management of idiopathic subglottic stenosis was associated with improved outcomes when compared to endoscopic techniques [5]. Such findings suggest a need to identify these factors for the purpose of optimizing clinical decision-making.

As laryngotracheal stenosis is rare, postoperative outcomes and risk factors are best identified on a multiinstitutional level. Due to its participation from 80 hospitals and its accurate and reliable reporting of both demographic and risk-stratified 30-day outcomes data, the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program – Pediatric (ACS NSQIP-P) provides such a platform [6–8]. Thirty-day outcomes and risk factors for open reconstruction utilizing the ACS NSQIP-P database have previously been reported; however, no such outcomes for endoscopic dilation have been described, and no comparison between endoscopic and open procedures has been made [9]. The purpose of this study was to utilize the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P database to investigate 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation of the pediatric airway and to compare these outcomes to open reconstruction techniques. Secondarily, we aimed to determine if any demographic factors or medical comorbidities are associated with varied outcomes in endoscopic reconstruction. While these data reflect safety and quality of this procedure in the United States, findings may potentially be applied across international settings.

Methods

Data Source

Data was obtained from the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P Public Use File (PUF). Due to the de-identified and public nature of these data, this research was exempt from review by the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago review board. Data collection methods for ACS-NSQIP-P have previously been described [10]. In brief, data was collected from 80 hospitals on approximately 120 preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables. Cases are systematically sampled on an 8-day cycle basis, where the first 35 cases meeting the inclusion criteria in each hospital in each cycle are submitted to ACS-NSQIP-P.

Variables and Outcomes

Airway procedures for endoscopic dilations and open reconstructions were obtained by CPT code. Endoscopic dilations (CPT 31528) were compared to open reconstructions, which included laryngoplasty (31580, 31582), cervical tracheoplasty (31750), cricoid split (31587), and tracheal resection (31780). Demographic variables included age, sex, race, and history of prematurity. Presence of specific comorbid diseases were also collected and tested for significance.

Dependent outcomes of interest were unplanned 30-day postoperative events grouped as reoperation, unplanned readmission, and postoperative reintubation. In the case of endoscopic procedures, the presence of salvage open reconstruction or tracheostomy within 30 days of surgery was also recorded. Length of stay (LOS) after the procedure was collected. Specific postoperative complications and reasons for readmission were recorded within the limitations of data available in the PUF.

Analysis

Analysis was performed using descriptive statistics and frequency analysis where appropriate. Chi-square analysis was used to compare adverse events between open and endoscopic procedures. Logistic regression with calculation of odds ratio (OR) was performed to determine predictive factors for reoperation, readmission, and reintubation in all pediatric airway reconstructive procedures in adjusted and unadjusted models. T-test and linear regression was performed on the continuous outcome of length of stay. For all analyses, a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All variable recoding and statistical analyses were performed in SAS/STAT software (Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 84,056 pediatric procedures were extracted from the 2015 NSQIP-P PUFs. Using the above CPT codes, 171 endoscopic dilations and 116 open airway reconstructions were identified, with patient age ranging from 0 days to 17.6 years. Average age of patients undergoing endoscopic dilation and open reconstruction was 4.1 and 5.4 years, respectively (Table 1).

Potential confounders were tested with univariate logistic regression to determine if they had a significant impact on readmission, reintubation, or reoperation rates. These variables (Table 2)

In patients undergoing endoscopic dilation, average length of stay was 5.5 days (SEM = 1.13), with 79 (48.5%) patients having a length of stay of zero days. Of all patients who had endoscopic dilations, 70 (40.1%) had a pre-existing tracheostomy and these accounted for the majority (73%) of patients who had zero days as their LOS. LOS after endoscopic management was significantly shorter than the mean of 11.3 days (SEM = 1.01) reported in those undergoing open reconstruction (P < 0.001).

With respect to 30-day adverse events, 2 patients in the endoscopic group (1.1%) required reintubation. Thirteen endoscopic dilation cases (7.6%) had an unplanned readmission, four (2.3%) of which were associated with reoperation within 30 days of the primary surgical procedure. There were 9 other reoperations unassociated with unplanned readmission. Three of these reoperations were due to failed endoscopic dilations, resulting in 2 tracheostomies and one open airway reconstruction. There was one patient death, in a 0-day old with tetralogy of Fallot, trachea-esophageal fistula, and ventilator dependence who underwent emergent endoscopic dilation and died the same day.

Open procedures were associated with 11 unplanned readmissions (9.5%), 7 re-intubations (6%) and 18 reoperations (15.5%). Of patents undergoing reoperation, one patient undergoing open reconstruction underwent tracheostomy within 30 days of surgery.

When comparing open reconstruction to endoscopic dilation, there was a significant increase in reintubation (OR = 7.41, P = 0.026) and reoperation (OR = 3.09, P = 0.009) for open procedures, even with adjustment for age, tracheostomy status, and pulmonary disease. There was no significant difference between the two for unplanned readmissions (OR = 1.19, P = 0.79) (Figure

Younger age was also found to be significantly associated with reoperation rates, in an adjusted logistic model that accounted for tracheostomy status, type of surgery, and pulmonary disease. Per year of life, younger children had higher reoperation rates than older children (OR = 1.91, P = 0.017). When endoscopic dilation was individually examined, children younger than 1 year of age were more likely to undergo reoperation after an endoscopic dilation than children older than 1 (OR = 4.39, P = 0.03). Children under age 1 were also more likely to have an unplanned readmission after an endoscopic dilation (OR = 4.21, P = 0.03). The relationship between age and re-intubation was not significant (OR = 0, P = 0.95). For open reconstruction, this age dichotomization was not associated with any increased reoperation (OR = 2.3, P = 0.52), readmission (OR = 0, P = 0.97), or reintubation (OR = 0, P = 0.94).

T-test analysis was performed to determine if children < 1 year old also had significantly longer hospital stays after endoscopic dilation than older children (mean 14.1 days vs 1.9 days, P < 0.001). This relationship held true in a linear regression after adjustment for pulmonary disease and tracheostomy, with length of stay decreasing by 0.48 days per year of life (P = 0.03). For endoscopic dilations, the same relationship held true, where length of stay decreased by 0.75 days per year of life.

Discussion

Endoscopic dilation for primary management of pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis has become commonplace. Despite this, outcomes of this procedure have only been described in case series and meta-analyses [2–5]. The relative rarity of pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis suggests the need for large, multi-institutional data for purposes of patient selection and medical decision-making.

This study utilized the ACS-NSQIP-Pediatric database to highlight 30-day outcomes of endoscopic dilation and to compare these outcomes to those of open airway reconstruction procedures. The ACS-NSQIP database has been endorsed by multiple organizations, including the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Joint Commission, and the American Medical Association. It has been shown to have higher sensitivity and a lower false-positive rate when compared to administrative data, in part due to data collection from trained personnel [11]. Furthermore, ACS-NSQIP use has the additional benefit of reporting an unplanned admission—a feature unavailable in review of claims data [12].

With respect to adverse events, our study demonstrates that endoscopic dilation is associated with an equally high rate of unplanned readmission when compared to open reconstruction. The high prevalence of comorbid disease such as chronic lung disease (32% of endoscopic dilation and 43% of open reconstruction) can account for some of the morbidity associated with any airway procedures.

Despite high rates of unplanned readmission, patients undergoing endoscopic dilation were less likely to have reoperations within 30 days of initial surgery when compared to those undergoing open reconstruction. While differences in disease severity may be partially responsible for this difference in the reoperation rate, this finding is notable given the health care costs associated with multiple operations as well as safety concerns with multiple anesthetics in the very young [13,14].

The ACS-NSQIP platform does not distinguish unplanned from planned reoperations. In the setting of airway surgery, where multiple planned reoperations are commonplace, this metric is a suboptimal stand-alone indicator of adverse outcomes. Other markers available in the database—such as reintubations and performance of tracheostomy or open airway reconstruction within 30-days of surgery—are more indicative of surgical outcome in the setting of airway surgery. We found that both reintubations and salvage open reconstruction within 30-days were rare. It should be noted that the ACS-NSQIP data does not report any events occurring outside of the 30-day postoperative period, representing potential limitation of the use of this database. As was previously advocated by Roxbury and colleagues, procedure/subspecialty specific outcome data collection would also improve outcome analysis of airway and other otolaryngologic procedures [9]. In the setting of airway reconstruction, this would include data pertaining to Cotton-Meyer grading systems well as postoperative voice and swallow outcomes.

In addition to safety profile, endoscopic procedures were associated with shorter LOS when compared with open reconstruction, representing another potential source of cost savings with this less invasive method. This is especially significant given that open reconstruction patients spend much of their inpatient stay in an ICU setting. In patients who are candidates for endoscopic procedures, this lower-risk, lower-cost profile of endoscopic dilation has the opportunity to improve value in health care and may be the source of future improvement initiatives.

In addition to comparing overall outcomes between endoscopic and open management of laryngotracheal stenosis, our study aimed to identify factors that were associated with varied outcomes in patients undergoing primary endoscopic dilation. We found that children younger than 1 year of age were 5.8 times more likely to undergo an unplanned reoperation after an endoscopic dilation than children over 1 year. A similar finding was reported in open airway surgeries, with increased reoperation rates in children < 3 years old [9]. The justification of a dichotomization at 1 year was made as expert opinion recognizes that the infant airway is less forgiving to intervention given its small size. Young age was also a factor in prolonged LOS as was determined by linear regression. It is likely that this increased LOS may be in part due to associations of young age and the neonatal ICU population. One must balance the increased risk of surgery in the young with that of tracheostomy, which has a published complication rate of 18% to 50% and direct mortality rate of 1% to 2% in the pediatric population [15–18]. Understanding these relative risks may help guide the airway surgeon in preoperative counseling with families and medical decision-making.

As discussed above, the limitation of data to a 30-day period is a relative weakness of ACS-NSQIP database use for studies of airway reconstruction, as the ultimate outcome—a stable, decannulated airway—may occur outside of this time period. As many quality metrics utilize data from the 30-day postoperative period, knowledge of these outcomes remains valuable in surgical decision-making. Ultimately, collection of data in a large, long-term dataset would allow broader generalizations to be made about the differences between open and endoscopic procedures and would also give a more comprehensive picture of the outcomes of endoscopic dilation.

In conclusion, this study is the first to analyze 30-day postoperative outcomes in pediatric endoscopic airway dilations using data aggregated by ACS-NSQIP from institutions across the United States. This data indicates that endoscopic airway dilation is a relatively safe procedure, especially compared with open reconstruction; however, additional data on disease severity and other outcomes is necessary to draw final conclusions of superiority of technique. Future improvement initiatives could be aimed at the impact of this lower-risk, lower-cost procedure in the appropriately selected patient. Outcomes of endoscopic dilation are poorer in those less than 1 year of age, as they are associated with increased reoperation rates and increased length of stay compared to older children. One must balance these risks in the very young with the risks associated with tracheostomy and other alternative airway management modalities.

Note: This work was presented in a paper at the AAO-HNS 2017 meeting, Chicago, IL, 10 Sep 2017.

Corresponding author: Jennifer Lavin, MD, MS, 225 E Chicago Ave., Box 25, Chicago, IL 60611, JLavin@luriechildrens.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Cohen MD, Weber TR, Rao CC. Balloon dilatation of tracheal and bronchial stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984;142:477–8.

2. Chueng K, Chadha NK. Primary dilatation as a treatment for pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013;77:623–8.

3. Hautefort C, Teissier N, Viala P, Van Den Abbeele T. Balloon dilation laryngoplasty for subglottic stenosis in children: eight years’ experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;138:235–40.

4. Lang M, Brietzke SE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic balloon dilation of pediatric subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;150:174–9.

5. Maresh A, Preciado DA, O’Connell AP, Zalzal GH. A comparative analysis of open surgery vs endoscopic balloon dilation for pediatric subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:901–5.

6. Gelbard A, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J, et al. Disease homogeneity and treatment heterogeneity in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 2016;126:1390–6.

7. ACS-NSQIP. ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program® (ACS NSQIP®). 2017. Available at: http://site.acsnsqip.org/program-specifics/scr-training-and-resources. Accessed June 2 2017.

8. Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:6–16.

9. Roxbury CR, Jatana KR, Shah RK, Boss EF. Safety and postoperative adverse events in pediatric airway reconstruction: Analysis of ACS-NSQIP-P 30-day outcomes. Laryngoscope 2017;127:504–8.

10. Raval MV, Dillon PW, Bruny JL, et al. Pediatric American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: feasibility of a novel, prospective assessment of surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46:115–21.

11. Lawson EH, Louie R, Zingmond DS, et al. A comparison of clinical registry versus administrative claims data for reporting of 30-day surgical complications. Ann Surg 2012;256:973–81.

12. Sellers MM, Merkow RP, Halverson A, et al. Validation of new readmission data in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:420–7.

13. Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci 2003;23:876–82.

14. Patel P, Sun L. Update on neonatal anesthetic neurotoxicity: insight into molecular mechanisms and relevance to humans. Anesthesiology 2009;110:703–8.

15. Crysdale WS, Feldman RI, Naito K. Tracheotomies: a 10-year experience in 319 children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1988;97(5 Pt 1):439–43.

16. Goldenberg D, Ari EG, Golz A, et al. Tracheotomy complications: a retrospective study of 1130 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:495–500.

17. Mahadevan M, Barber C, Salkeld L, et al N. Pediatric tracheotomy: 17 year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71:1829–35.

18. Ozmen S, Ozmen OA, Unal OF. Pediatric tracheotomies: a 37-year experience in 282 children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009;73:959–61.

1. Cohen MD, Weber TR, Rao CC. Balloon dilatation of tracheal and bronchial stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1984;142:477–8.

2. Chueng K, Chadha NK. Primary dilatation as a treatment for pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013;77:623–8.

3. Hautefort C, Teissier N, Viala P, Van Den Abbeele T. Balloon dilation laryngoplasty for subglottic stenosis in children: eight years’ experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;138:235–40.

4. Lang M, Brietzke SE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic balloon dilation of pediatric subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;150:174–9.

5. Maresh A, Preciado DA, O’Connell AP, Zalzal GH. A comparative analysis of open surgery vs endoscopic balloon dilation for pediatric subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:901–5.

6. Gelbard A, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J, et al. Disease homogeneity and treatment heterogeneity in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 2016;126:1390–6.

7. ACS-NSQIP. ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program® (ACS NSQIP®). 2017. Available at: http://site.acsnsqip.org/program-specifics/scr-training-and-resources. Accessed June 2 2017.

8. Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:6–16.

9. Roxbury CR, Jatana KR, Shah RK, Boss EF. Safety and postoperative adverse events in pediatric airway reconstruction: Analysis of ACS-NSQIP-P 30-day outcomes. Laryngoscope 2017;127:504–8.

10. Raval MV, Dillon PW, Bruny JL, et al. Pediatric American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: feasibility of a novel, prospective assessment of surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2011;46:115–21.

11. Lawson EH, Louie R, Zingmond DS, et al. A comparison of clinical registry versus administrative claims data for reporting of 30-day surgical complications. Ann Surg 2012;256:973–81.

12. Sellers MM, Merkow RP, Halverson A, et al. Validation of new readmission data in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:420–7.

13. Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, et al. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci 2003;23:876–82.

14. Patel P, Sun L. Update on neonatal anesthetic neurotoxicity: insight into molecular mechanisms and relevance to humans. Anesthesiology 2009;110:703–8.

15. Crysdale WS, Feldman RI, Naito K. Tracheotomies: a 10-year experience in 319 children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1988;97(5 Pt 1):439–43.

16. Goldenberg D, Ari EG, Golz A, et al. Tracheotomy complications: a retrospective study of 1130 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:495–500.

17. Mahadevan M, Barber C, Salkeld L, et al N. Pediatric tracheotomy: 17 year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71:1829–35.

18. Ozmen S, Ozmen OA, Unal OF. Pediatric tracheotomies: a 37-year experience in 282 children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009;73:959–61.

No clear winner in Pfannenstiel vs. vertical incision for high BMI cesareans

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.

The Bayesian analysis allowed ascertainment of the probability of treatment benefit despite the lower-than-hoped-for enrollment numbers. The primary weakness of the study, said Dr. Marrs, centered around the low consent rate, which led to a small study that was prematurely terminated.

“It’s difficult to enroll women in a trial that requires random allocation of skin incision, due to their preference to choose their own incision. A larger trial would likewise be challenging, and unlikely to yield different results,” said Dr. Marrs.

Dr. Marrs reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Marrs CC et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S29.

DALLAS – though enrollment difficulties limited study numbers, with almost two-thirds of eligible women declining to participate in the surgical trial.

At 6 weeks postdelivery, 21.1% of women who had a vertical incision experienced wound complications, compared with 18.6% of those who had a Pfannenstiel incision, a nonsignificant difference. This was a smaller difference than was seen at 2 weeks postpartum, when 20% of the vertical incision group had wound complications, compared with 10.4% of those who had a Pfannenstiel, also a nonsignificant difference. Maternal and fetal outcomes didn’t differ significantly with the two surgical approaches.

Though there had been several observational studies comparing vertical with Pfannenstiel incisions for cesarean delivery in women with obesity, no randomized, controlled trials had been conducted, and observational study results were mixed, said Dr. Marrs.

Each approach comes with theoretical pros and cons: For women who have a large pannus, the incision site may lie in a moist environment with a low transverse incision, and oxygen tension may be low. However, a Pfannenstiel incision usually will have better cosmesis than will a vertical incision, and generally will result in less postoperative pain.

On the other hand, said Dr. Marrs, vertical incisions can provide improved exposure of the uterus during delivery, and the moist environment underlying the pannus is avoided. However, wound tension may be higher, and subcutaneous thickness is likely to be higher than at the Pfannenstiel incision site.

The study, conducted at two academic medical centers, enrolled women with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40 kg/m2 at a gestational age of 24 weeks or greater who required cesarean delivery. Consenting women were then randomized to receive Pfannenstiel or vertical incisions.

Women who had clinical chorioamnionitis, whose amniotic membranes had been ruptured for 18 hours or more, or who had placenta accreta were excluded. Also excluded were women with a private physician and those desiring vaginal delivery, said Dr. Marrs, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The study’s primary outcome measure was a composite of wound complications seen within 6 weeks of delivery, including surgical site infection, whether superficial, deep, or involving an organ or tissue space; cellulitis; seroma or hematoma; and wound separation. Other maternal outcomes tracked in the study included postoperative length of stay, transfusion requirement, sepsis, readmission, and death.

Cesarean-specific secondary outcomes included operative time and time from skin incision to delivery, estimated blood loss, and any incidence of hysterectomy through a low transverse incision. Neonatal outcomes included a 5-minute Apgar score of less than 7, umbilical cord pH of less than 7, and neonatal ICU admissions.

Dr. Mars said that the goal enrollment for the study was 300 patients, to ensure adequate statistical power. However, they found enrollment a challenge, with low consent rates during the defined time period from October 2013 to May 2017. They shifted their statistical technique to a Bayesian analysis, taking into account the estimated probability of treatment benefit.

Using this approach, they found a 59% probability that a Pfannenstiel incision would lead to a lower primary outcome rate – a better result – than would a vertical incision. This result just missed the predetermined threshold of 60%, said Dr. Marrs.

Of the 789 women who met the BMI threshold for eligibility assessment, 420 (65%) who passed the screening declined to participate. Of those who consented to participation, an additional 137 women either withdrew consent or failed further screening, leaving 50 women who were randomized to the Pfannenstiel arm and 41 who were randomized to the vertical incision arm.

Baseline characteristics were similar between groups, with a mean maternal age of 30 years in the Pfannenstiel group and 28 years in the vertical incision group. Gestational age at delivery was a mean of 37 weeks in both groups, and mean BMI was 48-50 kg/m2.

Most patients (80%-90%) had public insurance. Diabetes was more common in the Pfannenstiel group (48%) than in the vertical incision cohort (32%). Just over 40% of patients were African American.

Two women in the Pfannenstiel group and three in the vertical incision group did not receive the intended incision. After accounting for patients lost to follow-up by 6 weeks, 43 women who received Pfannenstiel and 38 women who received vertical incisions were available for full evaluation.

Dr. Marrs said that the study, the first randomized trial to address this issue, had several strengths, including its being conducted at two sites with appropriate stratification for the sites. Also, an independent data safety monitoring board and two chart reviewers helped overcome some of the limitations of a surgical study, where complete blinding is impossible.