User login

More on climate change and mental health, burnout among surgeons

More on climate change and mental health

Your recent editorial (“A toxic and fractured political system can breed angst and PTSD”

The article suggested that psychiatrists are unequivocally tasked with managing the psychological aftermath of climate-related disasters. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this is an assumption and lacks empirical evidence. I concur with the authors’ recognition of the grave environmental concerns posed by pollution, but it is valid to question the extent to which these concerns are fueled by mass hysteria, exacerbated by articles such as this one. Climate change undoubtedly is a multifaceted issue at times exploited for political purposes. As a result, terms such as “climate change denialism” are warped expressions that polarize the public even further, hindering constructive dialogue. Rather than denying the issue at hand, I am advocating for environmentally friendly solutions that do not come at the cost of manipulating public sentiment for political gain.

Additionally, I would argue trauma often does not arise from climate change itself, but instead from the actions of misguided radical environmentalist policy that unwittingly can cause more harm than good. The devastating destruction in Maui is a case in point. The article focuses on climate change as a cause of nihilism in this country; however, there is serious need to explore broader sociological issues that underlie this sense of nihilism and lack of life meaning, especially in the young.

It is essential to engage in a balanced and evidence-based discussion regarding climate change and its potential mental health implications. While some concerns the authors raised are valid, it is equally important to avoid fomenting hysteria and consider alternative perspectives that may help bridge gaps in understanding and unite us in effectively addressing this global challenge.

Robert Barris, MD

Flushing, New York

I want to send my appreciation for publishing in the same issue your editorial “A toxic and fractured political system can breed angst and PTSD” and the article “Climate change and mental illness: What psychiatrists can do.” I believe the issues addressed are important and belong in the mainstream of current psychiatric discussion.

Regarding the differing views of optimists and pessimists, I agree that narrative is bound for destruction. Because of that, several months ago I decided to deliberately cultivate and maintain a sense of optimism while knowing the facts! I believe that stance is the only one that strategically can lead towards progress.

I also want to comment on the “religification” of politics. While I believe secular religions exist, I also believe what we are currently seeing in the United States is not the rise of secular religions, but instead an attempt to insert extreme religious beliefs into politics while using language to create the illusion that the Constitution’s barrier against the merging of church and state is not being breached. I don’t think we are seeing secular religion, but God-based religion masking as secular religion.

Michael A. Kalm, MD

Salt Lake City, Utah

More on physician burnout

I am writing in reference to “Burnout among surgeons: Lessons for psychiatrists” (

It would behoove institutions to teach methods to mitigate burnout starting with first-year medical students instead of waiting until the increased stress, workload, and responsibility of their intern year. Knowing there is a potential negative downstream effect on patient care, in addition to the negative personal and professional impact on surgeons, is significant. By taking the time to engage all medical students in confidential, affordable, accessible mental health care, institutions would not only decrease burnout in this population of physicians but decrease the likelihood of negative outcomes in patient care.

Elina Maymind, MD

Mt. Laurel, New Jersey

More on climate change and mental health

Your recent editorial (“A toxic and fractured political system can breed angst and PTSD”

The article suggested that psychiatrists are unequivocally tasked with managing the psychological aftermath of climate-related disasters. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this is an assumption and lacks empirical evidence. I concur with the authors’ recognition of the grave environmental concerns posed by pollution, but it is valid to question the extent to which these concerns are fueled by mass hysteria, exacerbated by articles such as this one. Climate change undoubtedly is a multifaceted issue at times exploited for political purposes. As a result, terms such as “climate change denialism” are warped expressions that polarize the public even further, hindering constructive dialogue. Rather than denying the issue at hand, I am advocating for environmentally friendly solutions that do not come at the cost of manipulating public sentiment for political gain.

Additionally, I would argue trauma often does not arise from climate change itself, but instead from the actions of misguided radical environmentalist policy that unwittingly can cause more harm than good. The devastating destruction in Maui is a case in point. The article focuses on climate change as a cause of nihilism in this country; however, there is serious need to explore broader sociological issues that underlie this sense of nihilism and lack of life meaning, especially in the young.

It is essential to engage in a balanced and evidence-based discussion regarding climate change and its potential mental health implications. While some concerns the authors raised are valid, it is equally important to avoid fomenting hysteria and consider alternative perspectives that may help bridge gaps in understanding and unite us in effectively addressing this global challenge.

Robert Barris, MD

Flushing, New York

I want to send my appreciation for publishing in the same issue your editorial “A toxic and fractured political system can breed angst and PTSD” and the article “Climate change and mental illness: What psychiatrists can do.” I believe the issues addressed are important and belong in the mainstream of current psychiatric discussion.

Regarding the differing views of optimists and pessimists, I agree that narrative is bound for destruction. Because of that, several months ago I decided to deliberately cultivate and maintain a sense of optimism while knowing the facts! I believe that stance is the only one that strategically can lead towards progress.

I also want to comment on the “religification” of politics. While I believe secular religions exist, I also believe what we are currently seeing in the United States is not the rise of secular religions, but instead an attempt to insert extreme religious beliefs into politics while using language to create the illusion that the Constitution’s barrier against the merging of church and state is not being breached. I don’t think we are seeing secular religion, but God-based religion masking as secular religion.

Michael A. Kalm, MD

Salt Lake City, Utah

More on physician burnout

I am writing in reference to “Burnout among surgeons: Lessons for psychiatrists” (

It would behoove institutions to teach methods to mitigate burnout starting with first-year medical students instead of waiting until the increased stress, workload, and responsibility of their intern year. Knowing there is a potential negative downstream effect on patient care, in addition to the negative personal and professional impact on surgeons, is significant. By taking the time to engage all medical students in confidential, affordable, accessible mental health care, institutions would not only decrease burnout in this population of physicians but decrease the likelihood of negative outcomes in patient care.

Elina Maymind, MD

Mt. Laurel, New Jersey

More on climate change and mental health

Your recent editorial (“A toxic and fractured political system can breed angst and PTSD”

The article suggested that psychiatrists are unequivocally tasked with managing the psychological aftermath of climate-related disasters. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this is an assumption and lacks empirical evidence. I concur with the authors’ recognition of the grave environmental concerns posed by pollution, but it is valid to question the extent to which these concerns are fueled by mass hysteria, exacerbated by articles such as this one. Climate change undoubtedly is a multifaceted issue at times exploited for political purposes. As a result, terms such as “climate change denialism” are warped expressions that polarize the public even further, hindering constructive dialogue. Rather than denying the issue at hand, I am advocating for environmentally friendly solutions that do not come at the cost of manipulating public sentiment for political gain.

Additionally, I would argue trauma often does not arise from climate change itself, but instead from the actions of misguided radical environmentalist policy that unwittingly can cause more harm than good. The devastating destruction in Maui is a case in point. The article focuses on climate change as a cause of nihilism in this country; however, there is serious need to explore broader sociological issues that underlie this sense of nihilism and lack of life meaning, especially in the young.

It is essential to engage in a balanced and evidence-based discussion regarding climate change and its potential mental health implications. While some concerns the authors raised are valid, it is equally important to avoid fomenting hysteria and consider alternative perspectives that may help bridge gaps in understanding and unite us in effectively addressing this global challenge.

Robert Barris, MD

Flushing, New York

I want to send my appreciation for publishing in the same issue your editorial “A toxic and fractured political system can breed angst and PTSD” and the article “Climate change and mental illness: What psychiatrists can do.” I believe the issues addressed are important and belong in the mainstream of current psychiatric discussion.

Regarding the differing views of optimists and pessimists, I agree that narrative is bound for destruction. Because of that, several months ago I decided to deliberately cultivate and maintain a sense of optimism while knowing the facts! I believe that stance is the only one that strategically can lead towards progress.

I also want to comment on the “religification” of politics. While I believe secular religions exist, I also believe what we are currently seeing in the United States is not the rise of secular religions, but instead an attempt to insert extreme religious beliefs into politics while using language to create the illusion that the Constitution’s barrier against the merging of church and state is not being breached. I don’t think we are seeing secular religion, but God-based religion masking as secular religion.

Michael A. Kalm, MD

Salt Lake City, Utah

More on physician burnout

I am writing in reference to “Burnout among surgeons: Lessons for psychiatrists” (

It would behoove institutions to teach methods to mitigate burnout starting with first-year medical students instead of waiting until the increased stress, workload, and responsibility of their intern year. Knowing there is a potential negative downstream effect on patient care, in addition to the negative personal and professional impact on surgeons, is significant. By taking the time to engage all medical students in confidential, affordable, accessible mental health care, institutions would not only decrease burnout in this population of physicians but decrease the likelihood of negative outcomes in patient care.

Elina Maymind, MD

Mt. Laurel, New Jersey

Managing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis

Ms. K, age 32, presents to the psychiatric clinic for a routine follow-up. Her history includes agoraphobia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Ms. K’s current medications are oral hydroxyzine 50 mg 4 times daily as needed for anxiety and paliperidone palmitate 234 mg IM monthly. Since her last follow-up, she has been switched from oral sertraline 150 mg/d to oral paroxetine 20 mg/d. Ms. K reports having constipation (which improves by taking oral docusate 100 mg twice daily) and generalized hyperhidrosis. She wants to alleviate the hyperhidrosis without changing her paroxetine because that medication improved her symptoms.

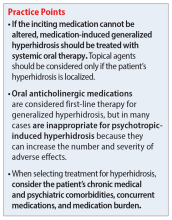

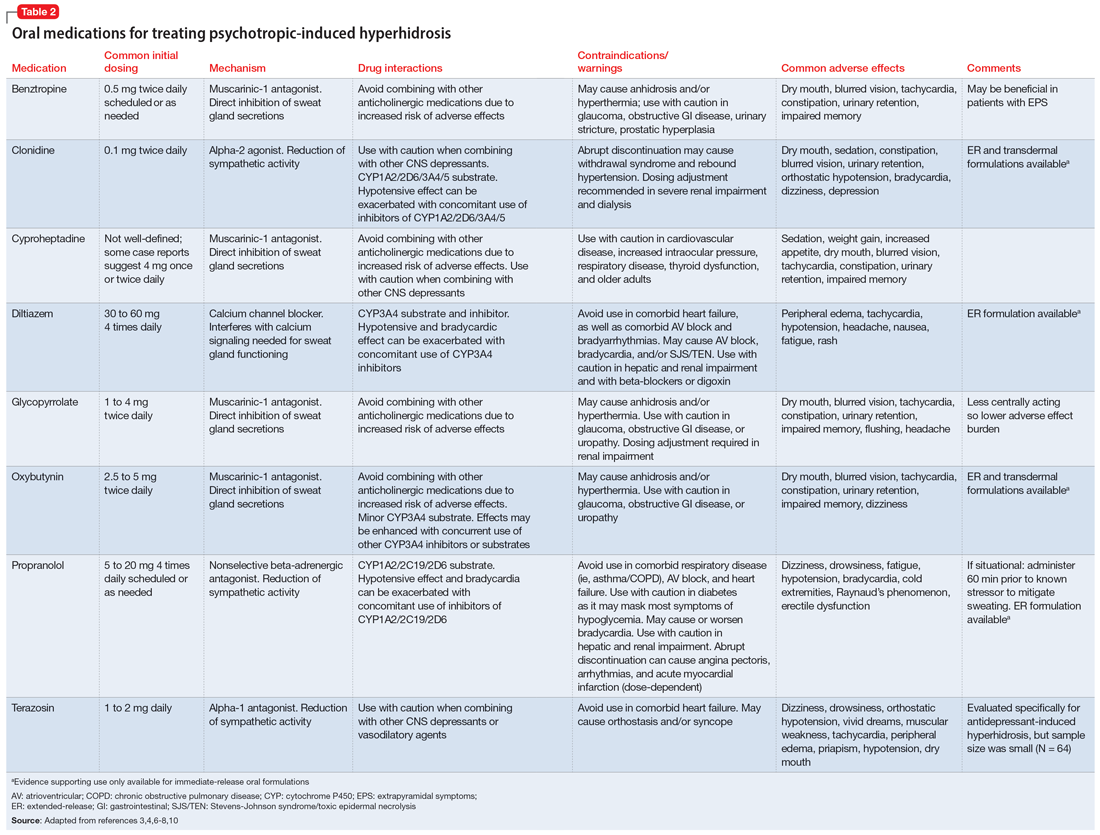

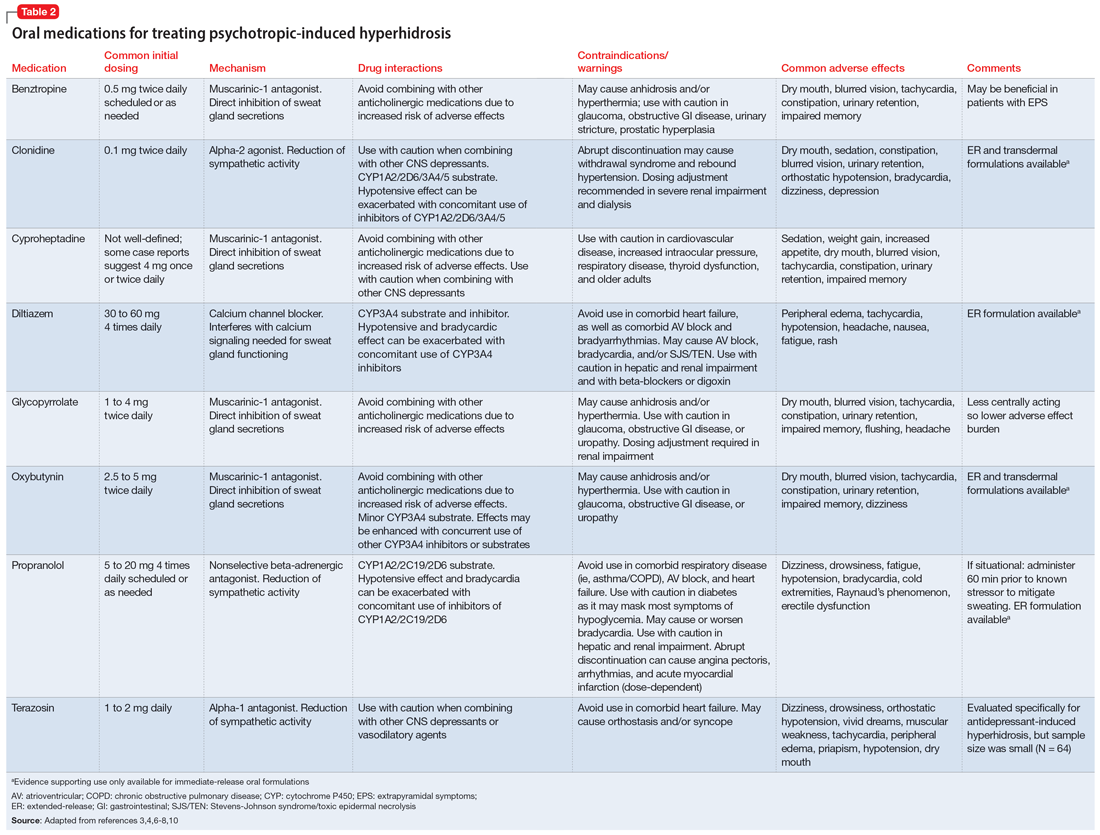

Hyperhidrosis—excessive sweating not needed to maintain a normal body temperature—is an uncommon and uncomfortable adverse effect of many medications, including psychotropics.1 This long-term adverse effect typically is not dose-related and does not remit with continued therapy.2Table 11-3 lists psychotropic medications associated with hyperhidrosis as well as postulated mechanisms.

The incidence of medication-induced hyperhidrosis is unknown,but for psychotropic medications it is estimated to be 5% to 20%.3 Patients may not report hyperhidrosis due to embarrassment; in clinical trials, reporting measures may be inconsistent and, in some cases, misleading. For example, it is possible hyperhidrosis that appears to be associated with buprenorphine is actually a symptom of the withdrawal syndrome rather than a direct effect of the medication. Also, some medications, including certain psychotropics (eg, paroxetine4 and topiramate3) may cause either hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (decreased sweating). Few medications carry labeled warnings for hypohidrosis; the condition generally is not of clinical concern unless patients experience heat intolerance or hyperthermia.3

Psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis is likely an idiopathic effect. There are few known predisposing factors, but some medications carry a greater risk than others. In a meta-analysis, Beyer et al2 found certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, had a higher risk of causing hyperhidrosis. Fluvoxamine, bupropion, and vortioxetine had the lowest risk. The class risk for SSRIs was comparable to that of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which all carried a comparable risk. In this analysis, neither indication nor dose were reliable indicators of risk of causing hyperhidrosis. However, the study found that for both SSRIs and SNRIs, increased affinity for the dopamine transporter was correlated with an increased risk of hyperhidrosis.2

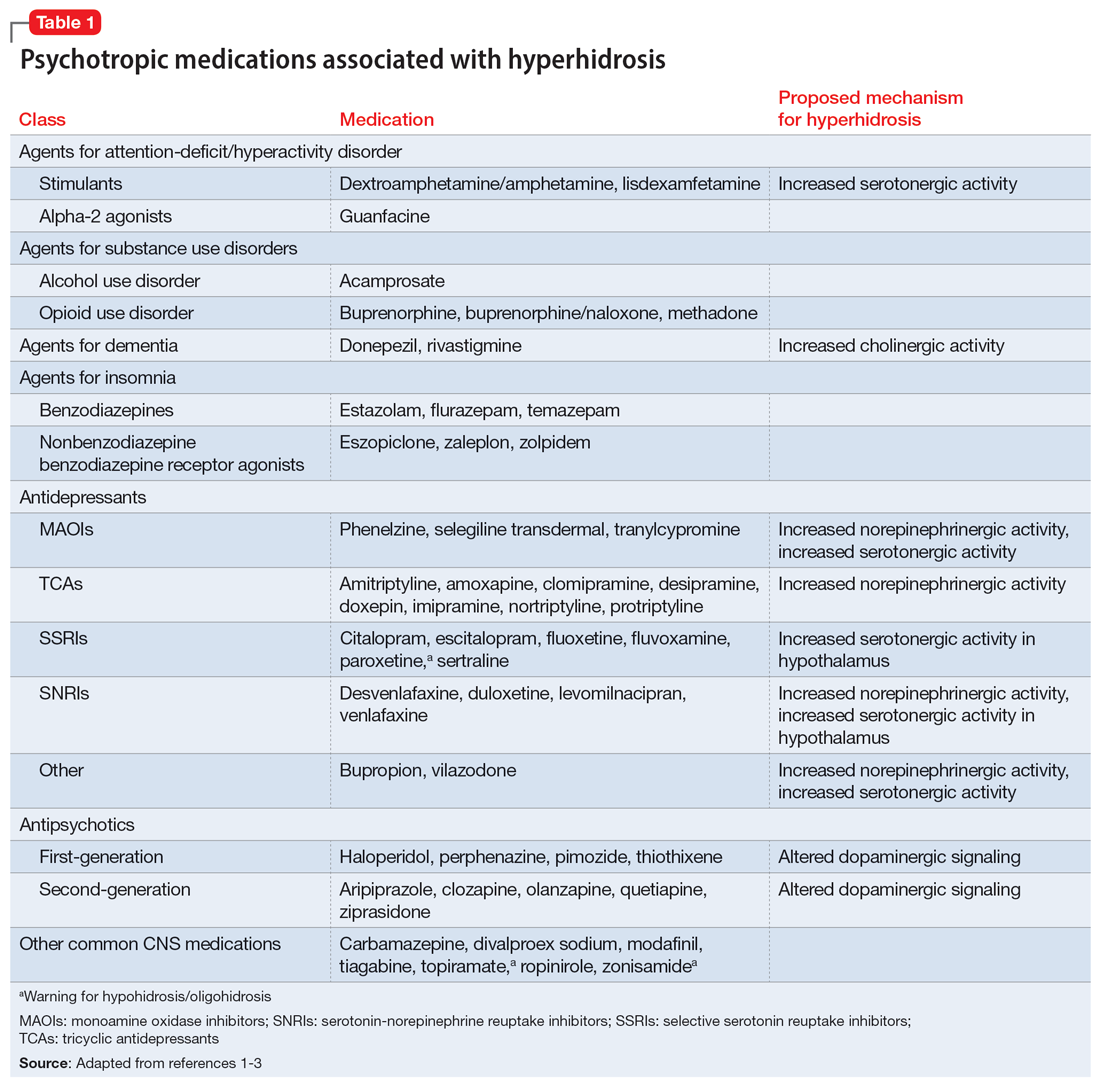

Treatment

Treatment of hyperhidrosis depends on its cause and presentation.5 Hyperhidrosis may be categorized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (also termed diaphoresis), and either focal or generalized.6 Many treatment recommendations focus on primary or focal hyperhidrosis and prioritize topical therapies.5 Because medication-induced hyperhidrosis most commonly presents as generalized3 and thus affects a large body surface area, the use of topical therapies is precluded. Topical therapy for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be pursued only if the patient’s sweating is localized.

Treating medication-induced hyperhidrosis becomes more complicated if it is not possible to alter the inciting medication (ie, because the medication is effective or the patient is resistant to change). In such scenarios, discontinuing the medication and initiating an alternative therapy may not be effective or feasible.2 For generalized presentations of medication-induced hyperhidrosis, if the inciting medication cannot be altered, initiating an oral systemic therapy is the preferred treatment.3,5

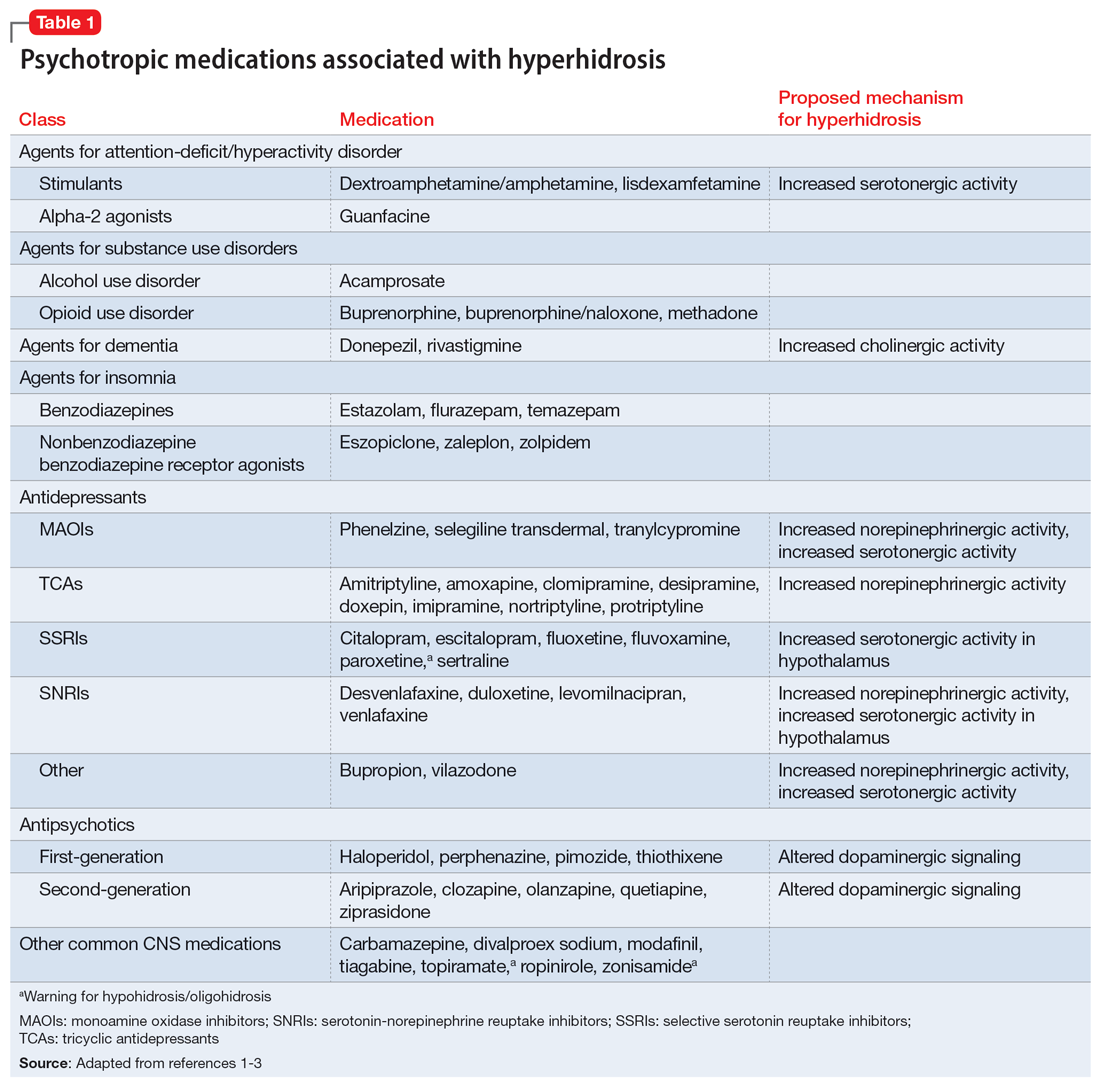

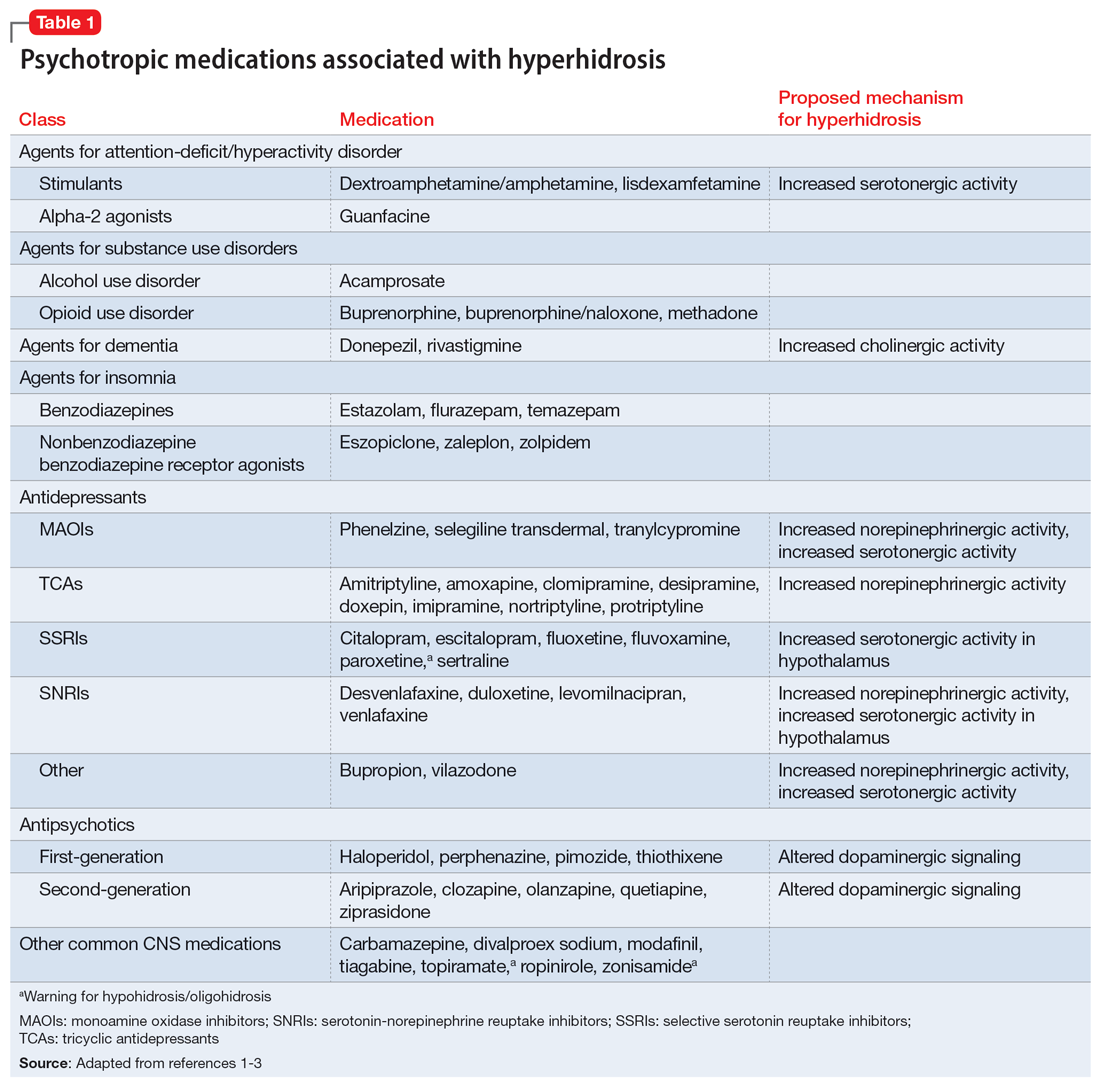

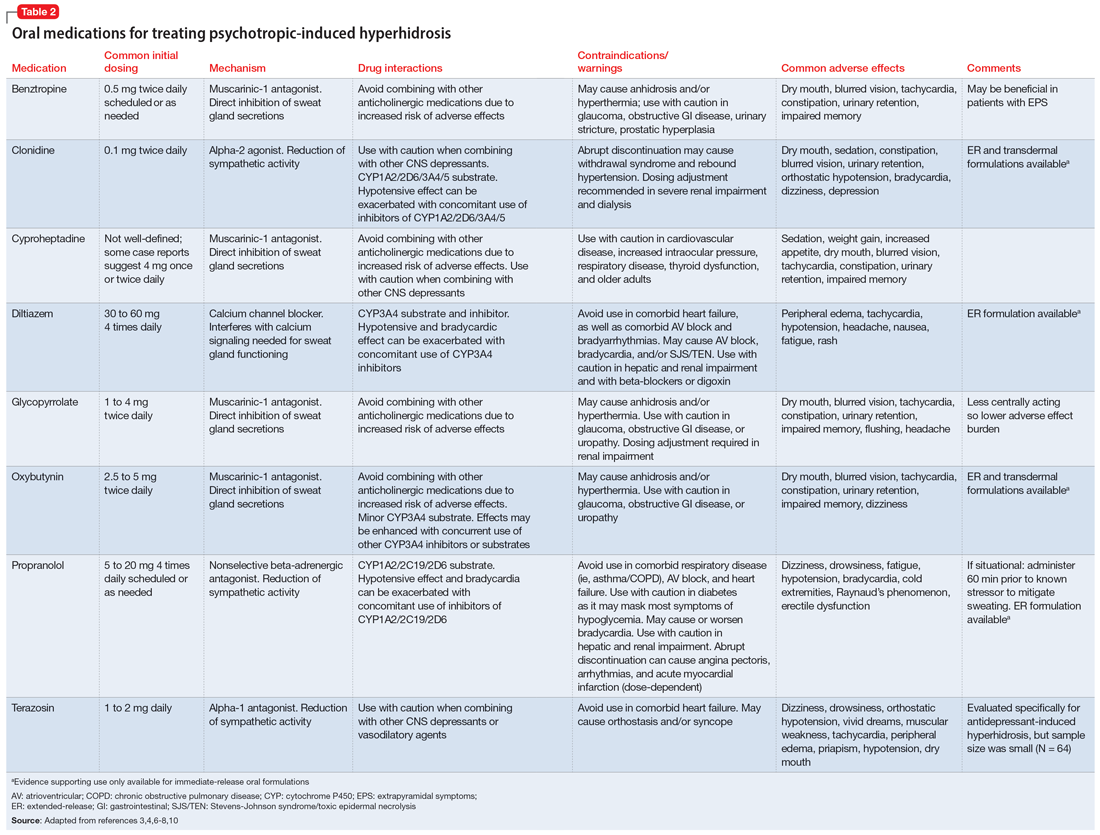

Oral anticholinergic medications (eg, benztropine, glycopyrrolate, and oxybutynin),4-6 act directly on muscarinic receptors within the eccrine sweat glands to decrease or stop sweating. They are considered first-line for generalized hyperhidrosis but may be inappropriate for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis because many psychotropics (eg, tricyclic antidepressants, paroxetine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine) have anticholinergic properties. Adding an anticholinergic medication to these patients’ regimens may increase the adverse effect burden and worsen cognitive deficits. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients discontinue anticholinergic medications due to tolerability issues (eg, dry mouth).

Continue to: However, anticholinergic medications...

However, anticholinergic medications may still have a role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis. Benztropine3,7,8 and cyproheptadine2,3,9 may be effective options, though their role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be limited and reserved for patients who have another compelling indication for these medications (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms) or when other treatment options are ineffective or intolerable.

Avoiding anticholinergic medications can also be justified based on the proposed mechanism of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as an extension of the medication’s toxic effects. Conceptualizing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as similar to the diaphoresis and hyperthermia observed in neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome offers a clearer target for treatment. Though the specifics of the mechanisms remain unknown,2 many medications that cause hyperhidrosis do so by increasing sweat gland secretions, either directly by increasing cholinergic activity or indirectly via increased sympathetic transmission.

Considering this pathophysiology, another target for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis may be altered and/or excessive catecholamine activity. The use of medications such as clonidine,3-6 propranolol,4-6 or terazosin2,3,10 should be considered given their beneficial effects on the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, although clonidine also possesses anticholinergic activity. The calcium channel blocker diltiazem can improve hyperhidrosis symptoms by interfering with the calcium signaling necessary for normal sweat gland function.4,5 Comorbid cardiovascular diseases and tachycardia, an adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, may also be managed with these treatment options. Some research suggests using benzodiazepines to treat psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis.4-6 As is the case for anticholinergic medications, the use of benzodiazepines would require another compelling indication for long-term use.

Table 23,4,6-8,10 provides recommended dosing and caveats for the use of these medications and other potentially appropriate medications.

Research of investigational treatments for generalized hyperhidrosis is ongoing. It is possible some of these medications may have a future role in the treatment of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis, with improved efficacy and better tolerability.

Continue to: CASE CONTINUED

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. K’s medication-induced hyperhidrosis is generalized and therefore ineligible for topical therapies, and because the inciting medication (paroxetine) cannot be switched to an alternative, the treatment team considers adding an oral medication. Treatment with an anticholinergic medication, such as benztropine, is not preferred due to the anticholinergic activity associated with paroxetine and Ms. K’s history of constipation. After discussing other oral treatment options with Ms. K, the team ultimately decides to initiate propranolol at a low dose (5 mg twice daily) to minimize the chances of an interaction with paroxetine, and titrate based on efficacy and tolerability.

Related Resources

- International Hyperhidrosis Society. Hyperhidrosis treatment overview. www.sweathelp.org/hyperhidrosis-treatments/treatment-overview.html

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buprenorphine • Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Zubsolv

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Divalproex • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Doxepin • Silenor

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Glycopyrrolate • Cuvposa

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Modafinil • Provigil

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimozide • Orap

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Selegiline transdermal • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Temazepam • Restoril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Topiramate • Topamax

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Zonisamide • Zonegran

1. International Hyperhidrosis Society. Drugs/medications known to cause hyperhidrosis. Sweathelp.org. 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/drugs_2009.pdf

2. Beyer C, Cappetta K, Johnson JA, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of hyperhidrosis with second-generation antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(12):1134-1146. doi:10.1002/da.22680

3. Cheshire WP, Fealey RD. Drug-induced hyperhidrosis and hypohidrosis: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2008;31(2):109-126. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831020-00002

4. del Boz J. Systemic treatment of hyperhidrosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(4):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2014.11.012

5. Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: a comprehensive review: therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):669-680. doi:10.1016/j.jaad2018.11.066

6. Glaser DA. Oral medications. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(4):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.06.002

7. Garber A, Gregory RJ. Benztropine in the treatment of venlafaxine-induced sweating. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):176-177. doi:10.4088/jcp.v58n0407e

8. Kolli V, Ramaswamy S. Improvement of antidepressant-induced sweating with as-required benztropine. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(11-12):10-11.

9. Ashton AK, Weinstein WL. Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):875. doi:10.1176/APPI.AJP.159.5.874-A

10. Ghaleiha A, Shahidi KM, Afzali S, et al. Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(1):44-47. doi:10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

Ms. K, age 32, presents to the psychiatric clinic for a routine follow-up. Her history includes agoraphobia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Ms. K’s current medications are oral hydroxyzine 50 mg 4 times daily as needed for anxiety and paliperidone palmitate 234 mg IM monthly. Since her last follow-up, she has been switched from oral sertraline 150 mg/d to oral paroxetine 20 mg/d. Ms. K reports having constipation (which improves by taking oral docusate 100 mg twice daily) and generalized hyperhidrosis. She wants to alleviate the hyperhidrosis without changing her paroxetine because that medication improved her symptoms.

Hyperhidrosis—excessive sweating not needed to maintain a normal body temperature—is an uncommon and uncomfortable adverse effect of many medications, including psychotropics.1 This long-term adverse effect typically is not dose-related and does not remit with continued therapy.2Table 11-3 lists psychotropic medications associated with hyperhidrosis as well as postulated mechanisms.

The incidence of medication-induced hyperhidrosis is unknown,but for psychotropic medications it is estimated to be 5% to 20%.3 Patients may not report hyperhidrosis due to embarrassment; in clinical trials, reporting measures may be inconsistent and, in some cases, misleading. For example, it is possible hyperhidrosis that appears to be associated with buprenorphine is actually a symptom of the withdrawal syndrome rather than a direct effect of the medication. Also, some medications, including certain psychotropics (eg, paroxetine4 and topiramate3) may cause either hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (decreased sweating). Few medications carry labeled warnings for hypohidrosis; the condition generally is not of clinical concern unless patients experience heat intolerance or hyperthermia.3

Psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis is likely an idiopathic effect. There are few known predisposing factors, but some medications carry a greater risk than others. In a meta-analysis, Beyer et al2 found certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, had a higher risk of causing hyperhidrosis. Fluvoxamine, bupropion, and vortioxetine had the lowest risk. The class risk for SSRIs was comparable to that of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which all carried a comparable risk. In this analysis, neither indication nor dose were reliable indicators of risk of causing hyperhidrosis. However, the study found that for both SSRIs and SNRIs, increased affinity for the dopamine transporter was correlated with an increased risk of hyperhidrosis.2

Treatment

Treatment of hyperhidrosis depends on its cause and presentation.5 Hyperhidrosis may be categorized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (also termed diaphoresis), and either focal or generalized.6 Many treatment recommendations focus on primary or focal hyperhidrosis and prioritize topical therapies.5 Because medication-induced hyperhidrosis most commonly presents as generalized3 and thus affects a large body surface area, the use of topical therapies is precluded. Topical therapy for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be pursued only if the patient’s sweating is localized.

Treating medication-induced hyperhidrosis becomes more complicated if it is not possible to alter the inciting medication (ie, because the medication is effective or the patient is resistant to change). In such scenarios, discontinuing the medication and initiating an alternative therapy may not be effective or feasible.2 For generalized presentations of medication-induced hyperhidrosis, if the inciting medication cannot be altered, initiating an oral systemic therapy is the preferred treatment.3,5

Oral anticholinergic medications (eg, benztropine, glycopyrrolate, and oxybutynin),4-6 act directly on muscarinic receptors within the eccrine sweat glands to decrease or stop sweating. They are considered first-line for generalized hyperhidrosis but may be inappropriate for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis because many psychotropics (eg, tricyclic antidepressants, paroxetine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine) have anticholinergic properties. Adding an anticholinergic medication to these patients’ regimens may increase the adverse effect burden and worsen cognitive deficits. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients discontinue anticholinergic medications due to tolerability issues (eg, dry mouth).

Continue to: However, anticholinergic medications...

However, anticholinergic medications may still have a role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis. Benztropine3,7,8 and cyproheptadine2,3,9 may be effective options, though their role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be limited and reserved for patients who have another compelling indication for these medications (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms) or when other treatment options are ineffective or intolerable.

Avoiding anticholinergic medications can also be justified based on the proposed mechanism of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as an extension of the medication’s toxic effects. Conceptualizing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as similar to the diaphoresis and hyperthermia observed in neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome offers a clearer target for treatment. Though the specifics of the mechanisms remain unknown,2 many medications that cause hyperhidrosis do so by increasing sweat gland secretions, either directly by increasing cholinergic activity or indirectly via increased sympathetic transmission.

Considering this pathophysiology, another target for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis may be altered and/or excessive catecholamine activity. The use of medications such as clonidine,3-6 propranolol,4-6 or terazosin2,3,10 should be considered given their beneficial effects on the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, although clonidine also possesses anticholinergic activity. The calcium channel blocker diltiazem can improve hyperhidrosis symptoms by interfering with the calcium signaling necessary for normal sweat gland function.4,5 Comorbid cardiovascular diseases and tachycardia, an adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, may also be managed with these treatment options. Some research suggests using benzodiazepines to treat psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis.4-6 As is the case for anticholinergic medications, the use of benzodiazepines would require another compelling indication for long-term use.

Table 23,4,6-8,10 provides recommended dosing and caveats for the use of these medications and other potentially appropriate medications.

Research of investigational treatments for generalized hyperhidrosis is ongoing. It is possible some of these medications may have a future role in the treatment of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis, with improved efficacy and better tolerability.

Continue to: CASE CONTINUED

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. K’s medication-induced hyperhidrosis is generalized and therefore ineligible for topical therapies, and because the inciting medication (paroxetine) cannot be switched to an alternative, the treatment team considers adding an oral medication. Treatment with an anticholinergic medication, such as benztropine, is not preferred due to the anticholinergic activity associated with paroxetine and Ms. K’s history of constipation. After discussing other oral treatment options with Ms. K, the team ultimately decides to initiate propranolol at a low dose (5 mg twice daily) to minimize the chances of an interaction with paroxetine, and titrate based on efficacy and tolerability.

Related Resources

- International Hyperhidrosis Society. Hyperhidrosis treatment overview. www.sweathelp.org/hyperhidrosis-treatments/treatment-overview.html

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buprenorphine • Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Zubsolv

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Divalproex • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Doxepin • Silenor

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Glycopyrrolate • Cuvposa

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Modafinil • Provigil

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimozide • Orap

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Selegiline transdermal • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Temazepam • Restoril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Topiramate • Topamax

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Ms. K, age 32, presents to the psychiatric clinic for a routine follow-up. Her history includes agoraphobia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Ms. K’s current medications are oral hydroxyzine 50 mg 4 times daily as needed for anxiety and paliperidone palmitate 234 mg IM monthly. Since her last follow-up, she has been switched from oral sertraline 150 mg/d to oral paroxetine 20 mg/d. Ms. K reports having constipation (which improves by taking oral docusate 100 mg twice daily) and generalized hyperhidrosis. She wants to alleviate the hyperhidrosis without changing her paroxetine because that medication improved her symptoms.

Hyperhidrosis—excessive sweating not needed to maintain a normal body temperature—is an uncommon and uncomfortable adverse effect of many medications, including psychotropics.1 This long-term adverse effect typically is not dose-related and does not remit with continued therapy.2Table 11-3 lists psychotropic medications associated with hyperhidrosis as well as postulated mechanisms.

The incidence of medication-induced hyperhidrosis is unknown,but for psychotropic medications it is estimated to be 5% to 20%.3 Patients may not report hyperhidrosis due to embarrassment; in clinical trials, reporting measures may be inconsistent and, in some cases, misleading. For example, it is possible hyperhidrosis that appears to be associated with buprenorphine is actually a symptom of the withdrawal syndrome rather than a direct effect of the medication. Also, some medications, including certain psychotropics (eg, paroxetine4 and topiramate3) may cause either hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (decreased sweating). Few medications carry labeled warnings for hypohidrosis; the condition generally is not of clinical concern unless patients experience heat intolerance or hyperthermia.3

Psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis is likely an idiopathic effect. There are few known predisposing factors, but some medications carry a greater risk than others. In a meta-analysis, Beyer et al2 found certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, had a higher risk of causing hyperhidrosis. Fluvoxamine, bupropion, and vortioxetine had the lowest risk. The class risk for SSRIs was comparable to that of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which all carried a comparable risk. In this analysis, neither indication nor dose were reliable indicators of risk of causing hyperhidrosis. However, the study found that for both SSRIs and SNRIs, increased affinity for the dopamine transporter was correlated with an increased risk of hyperhidrosis.2

Treatment

Treatment of hyperhidrosis depends on its cause and presentation.5 Hyperhidrosis may be categorized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (also termed diaphoresis), and either focal or generalized.6 Many treatment recommendations focus on primary or focal hyperhidrosis and prioritize topical therapies.5 Because medication-induced hyperhidrosis most commonly presents as generalized3 and thus affects a large body surface area, the use of topical therapies is precluded. Topical therapy for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be pursued only if the patient’s sweating is localized.

Treating medication-induced hyperhidrosis becomes more complicated if it is not possible to alter the inciting medication (ie, because the medication is effective or the patient is resistant to change). In such scenarios, discontinuing the medication and initiating an alternative therapy may not be effective or feasible.2 For generalized presentations of medication-induced hyperhidrosis, if the inciting medication cannot be altered, initiating an oral systemic therapy is the preferred treatment.3,5

Oral anticholinergic medications (eg, benztropine, glycopyrrolate, and oxybutynin),4-6 act directly on muscarinic receptors within the eccrine sweat glands to decrease or stop sweating. They are considered first-line for generalized hyperhidrosis but may be inappropriate for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis because many psychotropics (eg, tricyclic antidepressants, paroxetine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine) have anticholinergic properties. Adding an anticholinergic medication to these patients’ regimens may increase the adverse effect burden and worsen cognitive deficits. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients discontinue anticholinergic medications due to tolerability issues (eg, dry mouth).

Continue to: However, anticholinergic medications...

However, anticholinergic medications may still have a role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis. Benztropine3,7,8 and cyproheptadine2,3,9 may be effective options, though their role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be limited and reserved for patients who have another compelling indication for these medications (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms) or when other treatment options are ineffective or intolerable.

Avoiding anticholinergic medications can also be justified based on the proposed mechanism of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as an extension of the medication’s toxic effects. Conceptualizing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as similar to the diaphoresis and hyperthermia observed in neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome offers a clearer target for treatment. Though the specifics of the mechanisms remain unknown,2 many medications that cause hyperhidrosis do so by increasing sweat gland secretions, either directly by increasing cholinergic activity or indirectly via increased sympathetic transmission.

Considering this pathophysiology, another target for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis may be altered and/or excessive catecholamine activity. The use of medications such as clonidine,3-6 propranolol,4-6 or terazosin2,3,10 should be considered given their beneficial effects on the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, although clonidine also possesses anticholinergic activity. The calcium channel blocker diltiazem can improve hyperhidrosis symptoms by interfering with the calcium signaling necessary for normal sweat gland function.4,5 Comorbid cardiovascular diseases and tachycardia, an adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, may also be managed with these treatment options. Some research suggests using benzodiazepines to treat psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis.4-6 As is the case for anticholinergic medications, the use of benzodiazepines would require another compelling indication for long-term use.

Table 23,4,6-8,10 provides recommended dosing and caveats for the use of these medications and other potentially appropriate medications.

Research of investigational treatments for generalized hyperhidrosis is ongoing. It is possible some of these medications may have a future role in the treatment of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis, with improved efficacy and better tolerability.

Continue to: CASE CONTINUED

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. K’s medication-induced hyperhidrosis is generalized and therefore ineligible for topical therapies, and because the inciting medication (paroxetine) cannot be switched to an alternative, the treatment team considers adding an oral medication. Treatment with an anticholinergic medication, such as benztropine, is not preferred due to the anticholinergic activity associated with paroxetine and Ms. K’s history of constipation. After discussing other oral treatment options with Ms. K, the team ultimately decides to initiate propranolol at a low dose (5 mg twice daily) to minimize the chances of an interaction with paroxetine, and titrate based on efficacy and tolerability.

Related Resources

- International Hyperhidrosis Society. Hyperhidrosis treatment overview. www.sweathelp.org/hyperhidrosis-treatments/treatment-overview.html

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buprenorphine • Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Zubsolv

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Divalproex • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Doxepin • Silenor

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Glycopyrrolate • Cuvposa

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Modafinil • Provigil

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimozide • Orap

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Selegiline transdermal • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Temazepam • Restoril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Topiramate • Topamax

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Zonisamide • Zonegran

1. International Hyperhidrosis Society. Drugs/medications known to cause hyperhidrosis. Sweathelp.org. 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/drugs_2009.pdf

2. Beyer C, Cappetta K, Johnson JA, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of hyperhidrosis with second-generation antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(12):1134-1146. doi:10.1002/da.22680

3. Cheshire WP, Fealey RD. Drug-induced hyperhidrosis and hypohidrosis: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2008;31(2):109-126. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831020-00002

4. del Boz J. Systemic treatment of hyperhidrosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(4):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2014.11.012

5. Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: a comprehensive review: therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):669-680. doi:10.1016/j.jaad2018.11.066

6. Glaser DA. Oral medications. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(4):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.06.002

7. Garber A, Gregory RJ. Benztropine in the treatment of venlafaxine-induced sweating. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):176-177. doi:10.4088/jcp.v58n0407e

8. Kolli V, Ramaswamy S. Improvement of antidepressant-induced sweating with as-required benztropine. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(11-12):10-11.

9. Ashton AK, Weinstein WL. Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):875. doi:10.1176/APPI.AJP.159.5.874-A

10. Ghaleiha A, Shahidi KM, Afzali S, et al. Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(1):44-47. doi:10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

1. International Hyperhidrosis Society. Drugs/medications known to cause hyperhidrosis. Sweathelp.org. 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/drugs_2009.pdf

2. Beyer C, Cappetta K, Johnson JA, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of hyperhidrosis with second-generation antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(12):1134-1146. doi:10.1002/da.22680

3. Cheshire WP, Fealey RD. Drug-induced hyperhidrosis and hypohidrosis: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2008;31(2):109-126. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831020-00002

4. del Boz J. Systemic treatment of hyperhidrosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(4):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2014.11.012

5. Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: a comprehensive review: therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):669-680. doi:10.1016/j.jaad2018.11.066

6. Glaser DA. Oral medications. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(4):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.06.002

7. Garber A, Gregory RJ. Benztropine in the treatment of venlafaxine-induced sweating. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):176-177. doi:10.4088/jcp.v58n0407e

8. Kolli V, Ramaswamy S. Improvement of antidepressant-induced sweating with as-required benztropine. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(11-12):10-11.

9. Ashton AK, Weinstein WL. Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):875. doi:10.1176/APPI.AJP.159.5.874-A

10. Ghaleiha A, Shahidi KM, Afzali S, et al. Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(1):44-47. doi:10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

Supervising residents in an outpatient setting: 6 tips for success

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires supervision of residents “provides safe and effective care to patients; ensures each resident’s development of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to enter the unsupervised practice of medicine; and establishes a foundation for continued professional growth.”1 Beyond delineating supervision types (direct, indirect, or oversight), best practices for outpatient supervision are lacking, which perhaps contributes to challenges and discrepancies in experiences involving both trainees and supervisors.2 In this article, I provide 6 practical recommendations for supervisors to address and overcome these challenges.

1. Don’t skip orientation

Resist the pressure to jump directly into clinical care. Devote the first supervision session to learner orientation about expectations (eg, documentation and between-visit patient outreach), logistics (eg, electronic health record or absences), clinic workflow and processes (eg, no-shows or referrals), and team members. Provide this verbally and in writing; the former fosters additional discussion and prompts questions, while the latter serves as a useful reference.

2. Plan for the end at the beginning

Plan ahead for end-of-rotation issues (eg, transfers of care or clinician sign-out), particularly because handoffs are known patient safety risks.3 Provide a written sign-out template or example, set a deadline for the first draft, and ensure known verbal sign-out occurs to both you and any trainees coming into the rotation.

3. Facilitate self-identification of strengths, weaknesses, and goals

Individual learning plans (ILPs) are a fundamental component of adult learning theory, allowing for self-directed learning and ongoing assessment by trainee and supervisor. Complete the ILP together at the beginning of the rotation and regularly devote time to revisit and revise it. This process ensures targeted feedback, which will reduce the stress and potential surprises often associated with end-of-rotation evaluations.

4. Consider the homework you assign

Be intentional about assigned readings. Consider their frequency and length, highlight where you want learners to focus, provide self-reflection questions/prompts, and take time to discuss during supervision. If you use a structured curriculum, maintain flexibility so your trainees’ interests, topics arising in real-time clinical care, and relevant in-press articles can be included.

5. Use direct observation

Whenever possible, directly observe clinical care, particularly a patient’s intake. To reduce trainee (and patient) anxiety and preserve independence, state, “I’m the attending physician supervising Dr. (NAME), who will be your doctor. We provide feedback to trainees right up to graduation so I’m here to observe and will be quiet in the background.” While direct observation is associated with early learners and inpatient settings, it is also preferred by senior outpatient psychiatry residents4 and associated with positive educational and patient outcomes.5

6. Offer supplemental experiences

If feasible, offer additional interdisciplinary supervision (eg, social workers, psychologists, or peer support), scholarly opportunities (eg, case report collaboration or clinic talk), psychotherapy cases, or meeting with patients on your caseload (eg, patients with a rare diagnosis or unique presentation). These align with ACGME’s broad supervision requirements and offer much-appreciated individualized learning tailored to the trainee.

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency). Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf

2. Newman M, Ravindranath D, Figueroa S, et al. Perceptions of supervision in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):153-156. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0191-y

3. The Joint Commission. Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert. Issue 58. September 12, 2017. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_58_hand_off_comms_9_6_17_final_(1).pdf

4. Tan LL, Kam CJW. How psychiatry residents perceive clinical teaching effectiveness with or without direct supervision. The Asia-Pacific Scholar. 2020;5(2):14-21.

5. Galanter CA, Nikolov R, Green N, et al. Direct supervision in outpatient psychiatric graduate medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):157-163. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0247-z

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires supervision of residents “provides safe and effective care to patients; ensures each resident’s development of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to enter the unsupervised practice of medicine; and establishes a foundation for continued professional growth.”1 Beyond delineating supervision types (direct, indirect, or oversight), best practices for outpatient supervision are lacking, which perhaps contributes to challenges and discrepancies in experiences involving both trainees and supervisors.2 In this article, I provide 6 practical recommendations for supervisors to address and overcome these challenges.

1. Don’t skip orientation

Resist the pressure to jump directly into clinical care. Devote the first supervision session to learner orientation about expectations (eg, documentation and between-visit patient outreach), logistics (eg, electronic health record or absences), clinic workflow and processes (eg, no-shows or referrals), and team members. Provide this verbally and in writing; the former fosters additional discussion and prompts questions, while the latter serves as a useful reference.

2. Plan for the end at the beginning

Plan ahead for end-of-rotation issues (eg, transfers of care or clinician sign-out), particularly because handoffs are known patient safety risks.3 Provide a written sign-out template or example, set a deadline for the first draft, and ensure known verbal sign-out occurs to both you and any trainees coming into the rotation.

3. Facilitate self-identification of strengths, weaknesses, and goals

Individual learning plans (ILPs) are a fundamental component of adult learning theory, allowing for self-directed learning and ongoing assessment by trainee and supervisor. Complete the ILP together at the beginning of the rotation and regularly devote time to revisit and revise it. This process ensures targeted feedback, which will reduce the stress and potential surprises often associated with end-of-rotation evaluations.

4. Consider the homework you assign

Be intentional about assigned readings. Consider their frequency and length, highlight where you want learners to focus, provide self-reflection questions/prompts, and take time to discuss during supervision. If you use a structured curriculum, maintain flexibility so your trainees’ interests, topics arising in real-time clinical care, and relevant in-press articles can be included.

5. Use direct observation

Whenever possible, directly observe clinical care, particularly a patient’s intake. To reduce trainee (and patient) anxiety and preserve independence, state, “I’m the attending physician supervising Dr. (NAME), who will be your doctor. We provide feedback to trainees right up to graduation so I’m here to observe and will be quiet in the background.” While direct observation is associated with early learners and inpatient settings, it is also preferred by senior outpatient psychiatry residents4 and associated with positive educational and patient outcomes.5

6. Offer supplemental experiences

If feasible, offer additional interdisciplinary supervision (eg, social workers, psychologists, or peer support), scholarly opportunities (eg, case report collaboration or clinic talk), psychotherapy cases, or meeting with patients on your caseload (eg, patients with a rare diagnosis or unique presentation). These align with ACGME’s broad supervision requirements and offer much-appreciated individualized learning tailored to the trainee.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires supervision of residents “provides safe and effective care to patients; ensures each resident’s development of the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to enter the unsupervised practice of medicine; and establishes a foundation for continued professional growth.”1 Beyond delineating supervision types (direct, indirect, or oversight), best practices for outpatient supervision are lacking, which perhaps contributes to challenges and discrepancies in experiences involving both trainees and supervisors.2 In this article, I provide 6 practical recommendations for supervisors to address and overcome these challenges.

1. Don’t skip orientation

Resist the pressure to jump directly into clinical care. Devote the first supervision session to learner orientation about expectations (eg, documentation and between-visit patient outreach), logistics (eg, electronic health record or absences), clinic workflow and processes (eg, no-shows or referrals), and team members. Provide this verbally and in writing; the former fosters additional discussion and prompts questions, while the latter serves as a useful reference.

2. Plan for the end at the beginning

Plan ahead for end-of-rotation issues (eg, transfers of care or clinician sign-out), particularly because handoffs are known patient safety risks.3 Provide a written sign-out template or example, set a deadline for the first draft, and ensure known verbal sign-out occurs to both you and any trainees coming into the rotation.

3. Facilitate self-identification of strengths, weaknesses, and goals

Individual learning plans (ILPs) are a fundamental component of adult learning theory, allowing for self-directed learning and ongoing assessment by trainee and supervisor. Complete the ILP together at the beginning of the rotation and regularly devote time to revisit and revise it. This process ensures targeted feedback, which will reduce the stress and potential surprises often associated with end-of-rotation evaluations.

4. Consider the homework you assign

Be intentional about assigned readings. Consider their frequency and length, highlight where you want learners to focus, provide self-reflection questions/prompts, and take time to discuss during supervision. If you use a structured curriculum, maintain flexibility so your trainees’ interests, topics arising in real-time clinical care, and relevant in-press articles can be included.

5. Use direct observation

Whenever possible, directly observe clinical care, particularly a patient’s intake. To reduce trainee (and patient) anxiety and preserve independence, state, “I’m the attending physician supervising Dr. (NAME), who will be your doctor. We provide feedback to trainees right up to graduation so I’m here to observe and will be quiet in the background.” While direct observation is associated with early learners and inpatient settings, it is also preferred by senior outpatient psychiatry residents4 and associated with positive educational and patient outcomes.5

6. Offer supplemental experiences

If feasible, offer additional interdisciplinary supervision (eg, social workers, psychologists, or peer support), scholarly opportunities (eg, case report collaboration or clinic talk), psychotherapy cases, or meeting with patients on your caseload (eg, patients with a rare diagnosis or unique presentation). These align with ACGME’s broad supervision requirements and offer much-appreciated individualized learning tailored to the trainee.

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency). Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf

2. Newman M, Ravindranath D, Figueroa S, et al. Perceptions of supervision in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):153-156. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0191-y

3. The Joint Commission. Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert. Issue 58. September 12, 2017. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_58_hand_off_comms_9_6_17_final_(1).pdf

4. Tan LL, Kam CJW. How psychiatry residents perceive clinical teaching effectiveness with or without direct supervision. The Asia-Pacific Scholar. 2020;5(2):14-21.

5. Galanter CA, Nikolov R, Green N, et al. Direct supervision in outpatient psychiatric graduate medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):157-163. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0247-z

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency). Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2022v3.pdf

2. Newman M, Ravindranath D, Figueroa S, et al. Perceptions of supervision in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):153-156. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0191-y

3. The Joint Commission. Inadequate hand-off communication. Sentinel Event Alert. Issue 58. September 12, 2017. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_58_hand_off_comms_9_6_17_final_(1).pdf

4. Tan LL, Kam CJW. How psychiatry residents perceive clinical teaching effectiveness with or without direct supervision. The Asia-Pacific Scholar. 2020;5(2):14-21.

5. Galanter CA, Nikolov R, Green N, et al. Direct supervision in outpatient psychiatric graduate medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):157-163. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0247-z

Interviewing a patient experiencing psychosis

Clinicians of all experience levels, particularly trainees, may struggle when interviewing an individual experiencing psychosis. Many clinicians feel unsure what to say when a patient expresses fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change despite conflicting evidence, or worry about inadvertently affirming these beliefs. Supporting and empathizing with a person experiencing psychosis while avoiding reinforcing delusional beliefs is an important skillset for clinicians to have. While there is no single “correct” approach to interviewing individuals with psychosis, key principles include:

1. Do not begin by challenging delusions

People experiencing delusions often feel strongly about the validity of their beliefs and find evidence to support them. Directly challenging these beliefs from the beginning may alienate them. Instead, explore with neutral questioning: “Can you tell me more about X?” “What did you notice that made you believe Y?” Later, when rapport is established, it may be appropriate to explore discrepancies that provide insight into their delusions, a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis.

2. Validate the emotion, not the psychosis

Many interviewers worry that talking about a patient’s delusions or voices will inadvertently reinforce them. Instead of agreeing with the content, listen for and empathize with the emotion (which is often fear): “That sounds frightening.” If the emotion is unclear, ask: “How did you feel when that happened?” When unsure what to say, sometimes a neutral “mmm” conveys listening without reinforcing the psychosis.

3. Explicitly state emotions and intentions

People with psychosis may have difficulty processing others’ emotions and facial expressions.1 We recommend using verbal cues to assist them in recognizing emotions and intentions: “It makes me sad to hear how alone you felt,” or “I’m here to help you.” The interviewer may mildly “amplify” their facial expressions so that the person experiencing psychosis can more clearly identify the expressed emotion, though not all individuals with psychosis respond well to this.

4. Reflect the patient’s own words

We recommend using the patient’s exact (typically nonclinical) words in referring to their experiences to build rapport and a shared understanding of their subjective experience.2 Avoid introducing clinical jargon, such as “delusion” or “hallucination.” For example, the interviewer might follow a patient’s explanation of their experiences by asking: “You heard voices in the walls—what did they say?” If the patient uses clinical jargon, the interviewer should clarify their meaning: “When you say ‘paranoid,’ what does that mean to you?”

5. Be intentional with gestures and positioning

People with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders may have difficulty interpreting gestures and are more likely to perceive gestures as self-referential.1 We recommend minimizing gestures or using simple, neutral-to-positive movements appropriate to cultural context. For example, in the United States, hands with palms up in front of the body generally convey openness, whereas arms crossed over the chest may convey anger. We recommend that to avoid appearing confrontational, interviewers do not position themselves directly in front of the patient, instead positioning themselves at an angle. Consider mirroring patients’ gestures or postures to convey empathy and build rapport.3

1. Chapellier V, Pavlidou A, Maderthaner L, et al. The impact of poor nonverbal social perception on functional capacity in schizophrenia. Front Psychol. 2022;13:804093. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.804093

2. Olson M, Seikkula J, Ziedonis D. The key elements of dialogic practice in Open Dialogue: fidelity criteria. University of Massachusetts Medical School. Published September 2, 2014. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/psychiatry/open-dialogue/keyelementsv1.109022014.pdf

3. Raffard S, Salesse RN, Bortolon C, et al. Using mimicry of body movements by a virtual agent to increase synchronization behavior and rapport in individuals with schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17356. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35813-6

Clinicians of all experience levels, particularly trainees, may struggle when interviewing an individual experiencing psychosis. Many clinicians feel unsure what to say when a patient expresses fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change despite conflicting evidence, or worry about inadvertently affirming these beliefs. Supporting and empathizing with a person experiencing psychosis while avoiding reinforcing delusional beliefs is an important skillset for clinicians to have. While there is no single “correct” approach to interviewing individuals with psychosis, key principles include:

1. Do not begin by challenging delusions

People experiencing delusions often feel strongly about the validity of their beliefs and find evidence to support them. Directly challenging these beliefs from the beginning may alienate them. Instead, explore with neutral questioning: “Can you tell me more about X?” “What did you notice that made you believe Y?” Later, when rapport is established, it may be appropriate to explore discrepancies that provide insight into their delusions, a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis.

2. Validate the emotion, not the psychosis

Many interviewers worry that talking about a patient’s delusions or voices will inadvertently reinforce them. Instead of agreeing with the content, listen for and empathize with the emotion (which is often fear): “That sounds frightening.” If the emotion is unclear, ask: “How did you feel when that happened?” When unsure what to say, sometimes a neutral “mmm” conveys listening without reinforcing the psychosis.

3. Explicitly state emotions and intentions

People with psychosis may have difficulty processing others’ emotions and facial expressions.1 We recommend using verbal cues to assist them in recognizing emotions and intentions: “It makes me sad to hear how alone you felt,” or “I’m here to help you.” The interviewer may mildly “amplify” their facial expressions so that the person experiencing psychosis can more clearly identify the expressed emotion, though not all individuals with psychosis respond well to this.

4. Reflect the patient’s own words

We recommend using the patient’s exact (typically nonclinical) words in referring to their experiences to build rapport and a shared understanding of their subjective experience.2 Avoid introducing clinical jargon, such as “delusion” or “hallucination.” For example, the interviewer might follow a patient’s explanation of their experiences by asking: “You heard voices in the walls—what did they say?” If the patient uses clinical jargon, the interviewer should clarify their meaning: “When you say ‘paranoid,’ what does that mean to you?”

5. Be intentional with gestures and positioning

People with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders may have difficulty interpreting gestures and are more likely to perceive gestures as self-referential.1 We recommend minimizing gestures or using simple, neutral-to-positive movements appropriate to cultural context. For example, in the United States, hands with palms up in front of the body generally convey openness, whereas arms crossed over the chest may convey anger. We recommend that to avoid appearing confrontational, interviewers do not position themselves directly in front of the patient, instead positioning themselves at an angle. Consider mirroring patients’ gestures or postures to convey empathy and build rapport.3

Clinicians of all experience levels, particularly trainees, may struggle when interviewing an individual experiencing psychosis. Many clinicians feel unsure what to say when a patient expresses fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change despite conflicting evidence, or worry about inadvertently affirming these beliefs. Supporting and empathizing with a person experiencing psychosis while avoiding reinforcing delusional beliefs is an important skillset for clinicians to have. While there is no single “correct” approach to interviewing individuals with psychosis, key principles include:

1. Do not begin by challenging delusions

People experiencing delusions often feel strongly about the validity of their beliefs and find evidence to support them. Directly challenging these beliefs from the beginning may alienate them. Instead, explore with neutral questioning: “Can you tell me more about X?” “What did you notice that made you believe Y?” Later, when rapport is established, it may be appropriate to explore discrepancies that provide insight into their delusions, a technique used in cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis.

2. Validate the emotion, not the psychosis

Many interviewers worry that talking about a patient’s delusions or voices will inadvertently reinforce them. Instead of agreeing with the content, listen for and empathize with the emotion (which is often fear): “That sounds frightening.” If the emotion is unclear, ask: “How did you feel when that happened?” When unsure what to say, sometimes a neutral “mmm” conveys listening without reinforcing the psychosis.

3. Explicitly state emotions and intentions

People with psychosis may have difficulty processing others’ emotions and facial expressions.1 We recommend using verbal cues to assist them in recognizing emotions and intentions: “It makes me sad to hear how alone you felt,” or “I’m here to help you.” The interviewer may mildly “amplify” their facial expressions so that the person experiencing psychosis can more clearly identify the expressed emotion, though not all individuals with psychosis respond well to this.

4. Reflect the patient’s own words

We recommend using the patient’s exact (typically nonclinical) words in referring to their experiences to build rapport and a shared understanding of their subjective experience.2 Avoid introducing clinical jargon, such as “delusion” or “hallucination.” For example, the interviewer might follow a patient’s explanation of their experiences by asking: “You heard voices in the walls—what did they say?” If the patient uses clinical jargon, the interviewer should clarify their meaning: “When you say ‘paranoid,’ what does that mean to you?”

5. Be intentional with gestures and positioning

People with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders may have difficulty interpreting gestures and are more likely to perceive gestures as self-referential.1 We recommend minimizing gestures or using simple, neutral-to-positive movements appropriate to cultural context. For example, in the United States, hands with palms up in front of the body generally convey openness, whereas arms crossed over the chest may convey anger. We recommend that to avoid appearing confrontational, interviewers do not position themselves directly in front of the patient, instead positioning themselves at an angle. Consider mirroring patients’ gestures or postures to convey empathy and build rapport.3

1. Chapellier V, Pavlidou A, Maderthaner L, et al. The impact of poor nonverbal social perception on functional capacity in schizophrenia. Front Psychol. 2022;13:804093. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.804093

2. Olson M, Seikkula J, Ziedonis D. The key elements of dialogic practice in Open Dialogue: fidelity criteria. University of Massachusetts Medical School. Published September 2, 2014. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/psychiatry/open-dialogue/keyelementsv1.109022014.pdf

3. Raffard S, Salesse RN, Bortolon C, et al. Using mimicry of body movements by a virtual agent to increase synchronization behavior and rapport in individuals with schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17356. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35813-6

1. Chapellier V, Pavlidou A, Maderthaner L, et al. The impact of poor nonverbal social perception on functional capacity in schizophrenia. Front Psychol. 2022;13:804093. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.804093

2. Olson M, Seikkula J, Ziedonis D. The key elements of dialogic practice in Open Dialogue: fidelity criteria. University of Massachusetts Medical School. Published September 2, 2014. Accessed August 16, 2023. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/psychiatry/open-dialogue/keyelementsv1.109022014.pdf

3. Raffard S, Salesse RN, Bortolon C, et al. Using mimicry of body movements by a virtual agent to increase synchronization behavior and rapport in individuals with schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17356. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35813-6

The ‘borderlinization’ of our society and the mental health crisis

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

We appreciated Dr. Nasrallah’s recent editorial1 that implicated smartphones, social media, and video game addiction, combined with the pandemic, in causing default mode network (DMN) dysfunction. The United States Surgeon General’s May 2023 report echoed these concerns and recommended limiting the use of these platforms.2 While devices are accelerants on a raging fire of mental illness, we observe a more insidious etiology that kindled the flame long before the proliferation of social media use during the pandemic. I (MZP) call this the “borderlinization” of society.

Imagine living somewhere in America that time had forgotten, where youth did not use smartphones and social media or play video games, and throughout the pandemic, people continued to congregate and socialize. These are the religious enclaves throughout New York and New Jersey that we (MZP and RLP) serve. Yet if devices were predominantly to blame for the contemporary mental health crisis, we would not expect the growing mental health problems we encounter. So, what is going on?

Over the past decade, mental health awareness has permeated all institutions of education, media, business, and government, which has increased compassion for marginalized groups. Consequently, people who may have previously silently suffered have become encouraged and supported in seeking help. That is good news. The bad news is that we have also come to pathologize, label, and attempt to treat nearly all of life’s struggles, and have been exporting mental disease around the world.3 We are losing the sense of “normal” when more than one-half of all Americans will receive a DSM diagnosis in their lifetime.4

Traits of borderline personality disorder (BPD)—such as abandonment fears, unstable relationships, identity disturbance, affective instability, emptiness, anger, mistrust, and dissociation5—that previously were seen less often are now more commonplace among our patients. These patients’ therapists have “validated” their “victimization” of “microaggressions” such that they now require “trigger warnings,” “safe spaces,” and psychiatric “diagnosis and treatment” to be able to function “normally.” These developments have also positioned parents, educators, employers, and psychiatrists, who may share “power and privilege,” to “walk on eggshells” so as not to offend newfound hypersensitivities. Interestingly, the DMN may be a major, reversible driver in BPD,6 a possible final common pathway that is further impaired by devices starting to creep into our communities and amplify the dysfunction.

Beyond treating individual patients, we must consider mandating time away from devices to nourish our DMN. During a 25-hour period each week, we (MZP and RLP) unplug from all forms of work and electronics, remember the past, consider the future, reflect on self and others, connect with nature, meditate, and eat mindfully—all of which are DMN functions. We call it Shabbat, which people have observed for thousands of years to process the week before and rejuvenate for the week ahead. Excluding smartphones from school premises has also been helpful7 and could be implemented as a nationwide commitment to the developing brains of our youth. Finally, we need to look to our profession to promote resilience over dependence, distress tolerance over avoidance, and empathic communication over “cancellation” to help heal a divisive society.

1. Nasrallah HA. Is the contemporary mental health crisis among youth due to DMN disruption? Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(6):10-11,21. doi:10.12788/cp.0372

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon general issues new advisory about effects social media use has on youth mental health. May 23, 2023. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/05/23/surgeon-general-issues-new-advisory-about-effects-social-media-use-has-youth-mental-health.html

3. Watters E. Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche. Free Press; 2011.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About mental health. April 25, 2023. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/learn/index.htm

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

6. Amiri S, Mirfazeli FS, Grafman J, et al. Alternation in functional connectivity within default mode network after psychodynamic psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2023;22(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12991-023-00449-y

7. Beland LP, Murphy R. Ill communication: technology, distraction & student performance. Labour Economics. 2016;41:61-76. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2016.04.004

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

We appreciated Dr. Nasrallah’s recent editorial1 that implicated smartphones, social media, and video game addiction, combined with the pandemic, in causing default mode network (DMN) dysfunction. The United States Surgeon General’s May 2023 report echoed these concerns and recommended limiting the use of these platforms.2 While devices are accelerants on a raging fire of mental illness, we observe a more insidious etiology that kindled the flame long before the proliferation of social media use during the pandemic. I (MZP) call this the “borderlinization” of society.

Imagine living somewhere in America that time had forgotten, where youth did not use smartphones and social media or play video games, and throughout the pandemic, people continued to congregate and socialize. These are the religious enclaves throughout New York and New Jersey that we (MZP and RLP) serve. Yet if devices were predominantly to blame for the contemporary mental health crisis, we would not expect the growing mental health problems we encounter. So, what is going on?

Over the past decade, mental health awareness has permeated all institutions of education, media, business, and government, which has increased compassion for marginalized groups. Consequently, people who may have previously silently suffered have become encouraged and supported in seeking help. That is good news. The bad news is that we have also come to pathologize, label, and attempt to treat nearly all of life’s struggles, and have been exporting mental disease around the world.3 We are losing the sense of “normal” when more than one-half of all Americans will receive a DSM diagnosis in their lifetime.4