User login

Question 2

Correct answer: B. Selenium exposure.

Rationale

Helicobacter pylori infection is by far the most important risk factor for gastric cancer worldwide. Less common risk factors for gastric cancer include Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Menetrier's disease, and germline mutations in the CDH gene (encoding E-cadherin). However, there is some evidence that selenium, as well as high consumption of fruits and vegetables, may have protective effects against gastric cancer.

References

de Martel C et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013 Jun;42(2):219-40.

Giardiello FM et al. N Engl J Med. 1987 Jun 11;316(24):1511-4.

Qiao YL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009 Apr 1;101(7):507-18.

Correct answer: B. Selenium exposure.

Rationale

Helicobacter pylori infection is by far the most important risk factor for gastric cancer worldwide. Less common risk factors for gastric cancer include Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Menetrier's disease, and germline mutations in the CDH gene (encoding E-cadherin). However, there is some evidence that selenium, as well as high consumption of fruits and vegetables, may have protective effects against gastric cancer.

References

de Martel C et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013 Jun;42(2):219-40.

Giardiello FM et al. N Engl J Med. 1987 Jun 11;316(24):1511-4.

Qiao YL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009 Apr 1;101(7):507-18.

Correct answer: B. Selenium exposure.

Rationale

Helicobacter pylori infection is by far the most important risk factor for gastric cancer worldwide. Less common risk factors for gastric cancer include Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Menetrier's disease, and germline mutations in the CDH gene (encoding E-cadherin). However, there is some evidence that selenium, as well as high consumption of fruits and vegetables, may have protective effects against gastric cancer.

References

de Martel C et al. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013 Jun;42(2):219-40.

Giardiello FM et al. N Engl J Med. 1987 Jun 11;316(24):1511-4.

Qiao YL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009 Apr 1;101(7):507-18.

.

Question 1

Correct answer: E. Cervical dysplasia.

Rationale

In a nationwide cohort study, women with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis were found to have an increased risk of cervical dysplasia. Patients with ulcerative colitis had increased risks of low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, whereas patients with Crohn's disease also had increased risks of cervical cancer. Age-appropriate screening with pap smears is important for women diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease regardless of treatment type.

Reference

Rungoe et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Apr;13(4):693-700.e1.

Correct answer: E. Cervical dysplasia.

Rationale

In a nationwide cohort study, women with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis were found to have an increased risk of cervical dysplasia. Patients with ulcerative colitis had increased risks of low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, whereas patients with Crohn's disease also had increased risks of cervical cancer. Age-appropriate screening with pap smears is important for women diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease regardless of treatment type.

Reference

Rungoe et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Apr;13(4):693-700.e1.

Correct answer: E. Cervical dysplasia.

Rationale

In a nationwide cohort study, women with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis were found to have an increased risk of cervical dysplasia. Patients with ulcerative colitis had increased risks of low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, whereas patients with Crohn's disease also had increased risks of cervical cancer. Age-appropriate screening with pap smears is important for women diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease regardless of treatment type.

Reference

Rungoe et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Apr;13(4):693-700.e1.

Q1. A 25-year-old woman with colonic Crohn's disease presents for routine follow-up. She is in remission on her regimen of vedolizumab. When discussing her medication regimen, she asks about the long-term risks associated with her Crohn's disease and treatment.

Which of the following is a nonsurgical treatment for stress urinary incontinence?

[polldaddy:11216821]

[polldaddy:11216821]

[polldaddy:11216821]

What's your diagnosis?

Whipple's disease

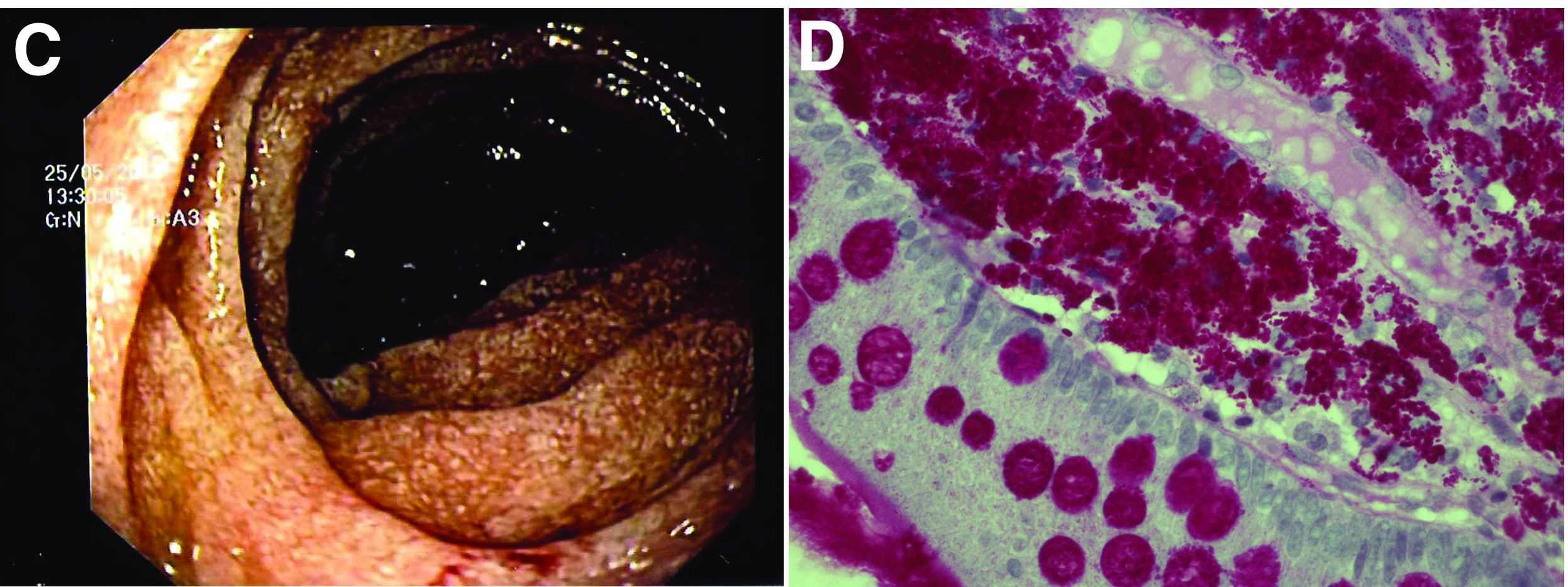

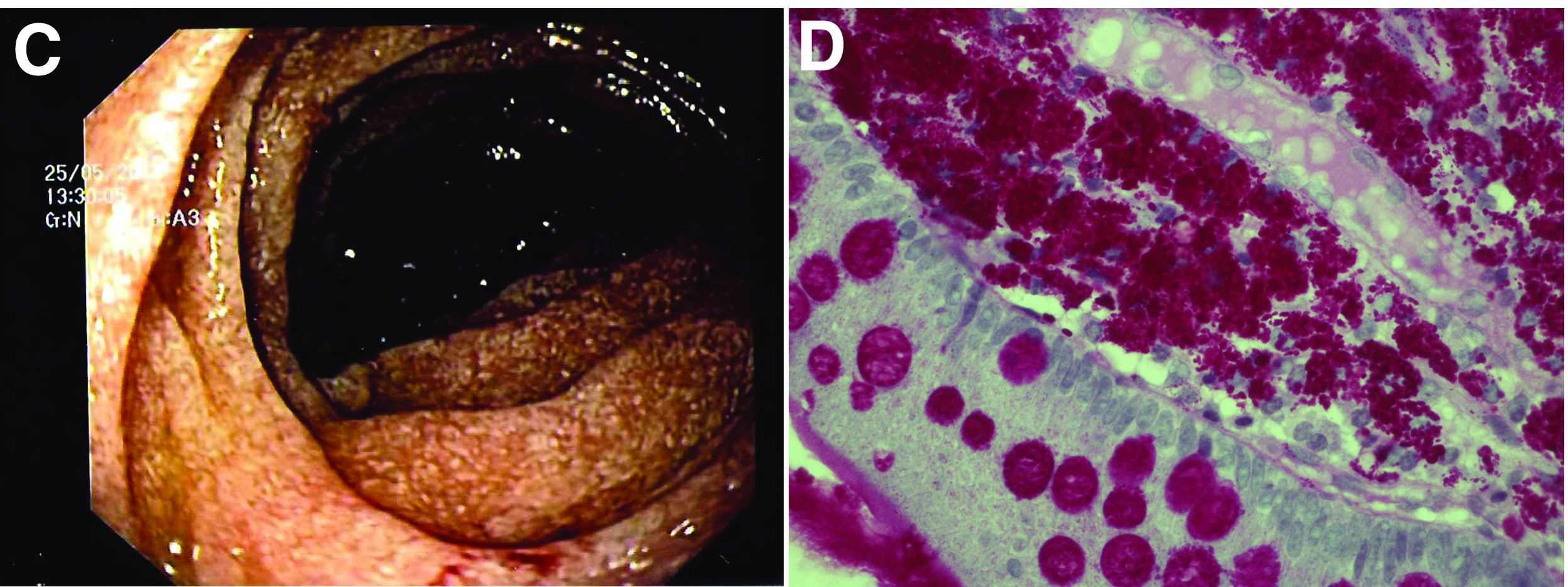

The ultrasound features were highly suggestive of malabsorption, a hypothesis that was supported by the laboratory findings. Celiac disease, one of the most common causes of malabsorption, was excluded by serology tests. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was therefore repeated: The mucosa of the distal first part and second part of the duodenum appeared completely covered with tiny white spots (Figure C). Histologic examination revealed that the mucosal architecture of the villi was altered by the presence of infiltrates of macrophages with wide cytoplasm filled with round periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive inclusions, associated to aggregates of neutrophils attacking the epithelium (Figure D). These histologic findings are consistent with Whipple's disease.

Whipple's disease is a chronic infectious disease caused by a gram-positive ubiquitous bacterium named Tropheryma whipplei. In predisposed subjects with an insufficient T-helper response, for example, those undergoing treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors as in our patient, T. whipplei is able to survive and replicate inside the macrophages of the intestinal mucosa and to spread to other organs.1 Whipple's disease can thus manifest as a multisystemic disease or as a single-organ disease with extraintestinal involvement (e.g., central nervous system, eyes, heart, or lung). The classic form is characterized by weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and signs of malabsorption, typically preceded by a history of arthralgia. The arthralgia is often misdiagnosed as a form of rheumatoid arthritis and therefore treated with immunosuppressant therapy, which favors the onset of the classic intestinal symptoms.

In the literature, few case reports describe the ultrasound findings in patients with Whipple's disease. The most frequent sonographic features include small-bowel dilatation with wall thickening, the presence of peri-intestinal fluid effusion and mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.2,3

The final diagnosis relies on intestinal biopsy and the histologic finding of foamy macrophages containing large amounts of diastase-resistant PAS-positive particles in the lamina propria of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or gastric antral region.

The diagnosis, particularly in cases of extraintestinal involvement, can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction positivity for T. whipplei in the examined tissue.

Therapy consists of the administration of ceftriaxone (2 g IV once daily) for 2 weeks followed by oral therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 1 year.

References

1. Schneider T et al. Whipple's disease: New aspects of pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:179-90.

2. Brindicci D et al. Ultrasonic findings in Whipple's disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:286-8.

3. Neye H et al. Der Morbus Whipple's Disease - A rare intestinal disease and its sonographic characteristics. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(04):314-5.

Whipple's disease

The ultrasound features were highly suggestive of malabsorption, a hypothesis that was supported by the laboratory findings. Celiac disease, one of the most common causes of malabsorption, was excluded by serology tests. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was therefore repeated: The mucosa of the distal first part and second part of the duodenum appeared completely covered with tiny white spots (Figure C). Histologic examination revealed that the mucosal architecture of the villi was altered by the presence of infiltrates of macrophages with wide cytoplasm filled with round periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive inclusions, associated to aggregates of neutrophils attacking the epithelium (Figure D). These histologic findings are consistent with Whipple's disease.

Whipple's disease is a chronic infectious disease caused by a gram-positive ubiquitous bacterium named Tropheryma whipplei. In predisposed subjects with an insufficient T-helper response, for example, those undergoing treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors as in our patient, T. whipplei is able to survive and replicate inside the macrophages of the intestinal mucosa and to spread to other organs.1 Whipple's disease can thus manifest as a multisystemic disease or as a single-organ disease with extraintestinal involvement (e.g., central nervous system, eyes, heart, or lung). The classic form is characterized by weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and signs of malabsorption, typically preceded by a history of arthralgia. The arthralgia is often misdiagnosed as a form of rheumatoid arthritis and therefore treated with immunosuppressant therapy, which favors the onset of the classic intestinal symptoms.

In the literature, few case reports describe the ultrasound findings in patients with Whipple's disease. The most frequent sonographic features include small-bowel dilatation with wall thickening, the presence of peri-intestinal fluid effusion and mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.2,3

The final diagnosis relies on intestinal biopsy and the histologic finding of foamy macrophages containing large amounts of diastase-resistant PAS-positive particles in the lamina propria of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or gastric antral region.

The diagnosis, particularly in cases of extraintestinal involvement, can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction positivity for T. whipplei in the examined tissue.

Therapy consists of the administration of ceftriaxone (2 g IV once daily) for 2 weeks followed by oral therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 1 year.

References

1. Schneider T et al. Whipple's disease: New aspects of pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:179-90.

2. Brindicci D et al. Ultrasonic findings in Whipple's disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:286-8.

3. Neye H et al. Der Morbus Whipple's Disease - A rare intestinal disease and its sonographic characteristics. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(04):314-5.

Whipple's disease

The ultrasound features were highly suggestive of malabsorption, a hypothesis that was supported by the laboratory findings. Celiac disease, one of the most common causes of malabsorption, was excluded by serology tests. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was therefore repeated: The mucosa of the distal first part and second part of the duodenum appeared completely covered with tiny white spots (Figure C). Histologic examination revealed that the mucosal architecture of the villi was altered by the presence of infiltrates of macrophages with wide cytoplasm filled with round periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive inclusions, associated to aggregates of neutrophils attacking the epithelium (Figure D). These histologic findings are consistent with Whipple's disease.

Whipple's disease is a chronic infectious disease caused by a gram-positive ubiquitous bacterium named Tropheryma whipplei. In predisposed subjects with an insufficient T-helper response, for example, those undergoing treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors as in our patient, T. whipplei is able to survive and replicate inside the macrophages of the intestinal mucosa and to spread to other organs.1 Whipple's disease can thus manifest as a multisystemic disease or as a single-organ disease with extraintestinal involvement (e.g., central nervous system, eyes, heart, or lung). The classic form is characterized by weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and signs of malabsorption, typically preceded by a history of arthralgia. The arthralgia is often misdiagnosed as a form of rheumatoid arthritis and therefore treated with immunosuppressant therapy, which favors the onset of the classic intestinal symptoms.

In the literature, few case reports describe the ultrasound findings in patients with Whipple's disease. The most frequent sonographic features include small-bowel dilatation with wall thickening, the presence of peri-intestinal fluid effusion and mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.2,3

The final diagnosis relies on intestinal biopsy and the histologic finding of foamy macrophages containing large amounts of diastase-resistant PAS-positive particles in the lamina propria of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or gastric antral region.

The diagnosis, particularly in cases of extraintestinal involvement, can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction positivity for T. whipplei in the examined tissue.

Therapy consists of the administration of ceftriaxone (2 g IV once daily) for 2 weeks followed by oral therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 1 year.

References

1. Schneider T et al. Whipple's disease: New aspects of pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:179-90.

2. Brindicci D et al. Ultrasonic findings in Whipple's disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:286-8.

3. Neye H et al. Der Morbus Whipple's Disease - A rare intestinal disease and its sonographic characteristics. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(04):314-5.

67-year-old woman presented with a year-long history of general malaise, low-grade fever, diarrhea, and a 20-kg weight loss. She had a history of hypertension and depressive disorder. In the previous 4 years, she had undergone several rheumatologic examinations for polyarthritis and, having been diagnosed with seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, she had been treated with steroids, methotrexate, and etanercept, with little benefit.

Recent laboratory tests showed: hemoglobin, 8.3 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 70 fL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 78; and C-reactive protein, 6.4 mg/dL. To evaluate the microcytic anemia and the diarrhea, endoscopic investigations had been performed a few months earlier. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed villous atrophy at the level of DII; histology was compatible with intramucosal xanthoma. There were no pathologic findings at colonoscopy. The situation had not been further investigated.

At presentation, the physical examination revealed lower-limb edema, skin and mucosal pallor, and a body mass index of 17.4 kg/m2. Laboratory tests showed microcytic anemia (hemoglobin, 10.0 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 74 fL), increased acute-phase proteins (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 59; C-reactive protein, 8.53 mg/dL), and malabsorption (albumin, 2.5 g/dL; multiple electrolytes deficiencies including iron, vitamin A, and vitamin D deficiency).

Abdominal ultrasound examination revealed three small lymph nodes in the periaortic region (maximum diameter, 10 mm), marked mesenteric and ileal wall thickening, mild jejunal wall thickening, an increased number of connivent valves, and a mild amount of peri-intestinal fluid effusion (Figure A, B).

What is the likely diagnosis and the appropriate treatment?

Question 2

Q2. Correct answer: D. Treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease is imatinib.

Rationale

This patient has a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the stomach. GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumor found in the stomach. Gastric GISTs have a better prognosis than those found in the small intestine. GISTs are often found incidentally but can cause symptoms such as bleeding due to ulceration. Pathology of a GIST shows spindle cells that stain positive for CD117 and harbor KIT mutations. Malignant potential and decreased survival are associated with size more than 2 cm and high mitotic index (more than 5/50 high power field). Endoscopic ultrasound with tissue sampling is the preferred diagnostic technique. High-risk features include lobulated or irregular borders, invasion into adjacent structures and heterogeneity. Fine needle aspirate may be suboptimal, and core biopsy is an acceptable alternative. Resection is indicated for lesions that are symptomatic, size more than 2 cm or high-risk EUS features. Lesions less than 2 cm without high-risk features can be surveyed by EUS annually. Endoscopic resection might be possible for small lesions but should be done in specialized centers. Metastatic or recurrent lesions are treated with imatinib.

Reference

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jul;82(1):1-8.

Q2. Correct answer: D. Treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease is imatinib.

Rationale

This patient has a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the stomach. GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumor found in the stomach. Gastric GISTs have a better prognosis than those found in the small intestine. GISTs are often found incidentally but can cause symptoms such as bleeding due to ulceration. Pathology of a GIST shows spindle cells that stain positive for CD117 and harbor KIT mutations. Malignant potential and decreased survival are associated with size more than 2 cm and high mitotic index (more than 5/50 high power field). Endoscopic ultrasound with tissue sampling is the preferred diagnostic technique. High-risk features include lobulated or irregular borders, invasion into adjacent structures and heterogeneity. Fine needle aspirate may be suboptimal, and core biopsy is an acceptable alternative. Resection is indicated for lesions that are symptomatic, size more than 2 cm or high-risk EUS features. Lesions less than 2 cm without high-risk features can be surveyed by EUS annually. Endoscopic resection might be possible for small lesions but should be done in specialized centers. Metastatic or recurrent lesions are treated with imatinib.

Reference

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jul;82(1):1-8.

Q2. Correct answer: D. Treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease is imatinib.

Rationale

This patient has a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the stomach. GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumor found in the stomach. Gastric GISTs have a better prognosis than those found in the small intestine. GISTs are often found incidentally but can cause symptoms such as bleeding due to ulceration. Pathology of a GIST shows spindle cells that stain positive for CD117 and harbor KIT mutations. Malignant potential and decreased survival are associated with size more than 2 cm and high mitotic index (more than 5/50 high power field). Endoscopic ultrasound with tissue sampling is the preferred diagnostic technique. High-risk features include lobulated or irregular borders, invasion into adjacent structures and heterogeneity. Fine needle aspirate may be suboptimal, and core biopsy is an acceptable alternative. Resection is indicated for lesions that are symptomatic, size more than 2 cm or high-risk EUS features. Lesions less than 2 cm without high-risk features can be surveyed by EUS annually. Endoscopic resection might be possible for small lesions but should be done in specialized centers. Metastatic or recurrent lesions are treated with imatinib.

Reference

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jul;82(1):1-8.

Q2. A 65-year-old man undergoes upper endoscopy for epigastric discomfort. The exam results are normal, except for a 3-cm submucosal mass in the body of the stomach. Endoscopic ultrasound shows that the mass arises from the fourth layer of the stomach wall. CT of the abdomen confirms the solid gastric mass with several small lesions in the liver concerning for metastatic disease. Biopsy of the mass shows CD117-positive spindle cells.

Question 1

Q1. Correct answer: D. Lorcaserin (Belviq).

Rationale

Lorcaserin may cause valvulopathy, attention, or memory disturbance. This patient has normal ECHO and does not work with heavy machinery. Given his other history, this may be the best choice for him. Naltrexone/bupropion extended release is contraindicated in patients with seizure disorder, chronic opioid use, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or antiepileptic drugs because bupropion lowers the seizure threshold. Liraglutide is contraindicated with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or MENII. In addition, GLP1 receptor agonists can increase the risk of pancreatitis in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Phentermine/topiramate can increase the risk of nephrolithiasis. All of these medications are contraindicated in pregnancy and in patients with hypersensitivity to the drug and drug class.

References

Bays HE et al. Obesity algorithm, presented by the Obesity Medical Association. 2016-2017. https://cmcoem.info/pdf/curso/evaluacion_preoperatoria/oma_obesity-algorithm.pdf.

Steelman M and Westman E. Obesity: Evaluation and Treatment Essentials. Boca Raton: CRC press, 2016. https://www.abom.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Obesity-Evaluation-and-Treatment-Essentials.pdf.

Liraglutide Prescribing Information (Saxenda). https://www.novo-pi.com/saxenda.pdf.

Lorcaserin (Belviq) Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022529lbl.pdf.

Naltrexone HCl/Bupropion HCl Extended Release Prescribing Information (CONTRAVE). https://contrave.com/contrave-pi/.

Phentermine HCl/Topiramate Extended Release Prescribing Information (Qsymia). https://qsymia.com/patient/include/media/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf

Q1. Correct answer: D. Lorcaserin (Belviq).

Rationale

Lorcaserin may cause valvulopathy, attention, or memory disturbance. This patient has normal ECHO and does not work with heavy machinery. Given his other history, this may be the best choice for him. Naltrexone/bupropion extended release is contraindicated in patients with seizure disorder, chronic opioid use, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or antiepileptic drugs because bupropion lowers the seizure threshold. Liraglutide is contraindicated with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or MENII. In addition, GLP1 receptor agonists can increase the risk of pancreatitis in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Phentermine/topiramate can increase the risk of nephrolithiasis. All of these medications are contraindicated in pregnancy and in patients with hypersensitivity to the drug and drug class.

References

Bays HE et al. Obesity algorithm, presented by the Obesity Medical Association. 2016-2017. https://cmcoem.info/pdf/curso/evaluacion_preoperatoria/oma_obesity-algorithm.pdf.

Steelman M and Westman E. Obesity: Evaluation and Treatment Essentials. Boca Raton: CRC press, 2016. https://www.abom.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Obesity-Evaluation-and-Treatment-Essentials.pdf.

Liraglutide Prescribing Information (Saxenda). https://www.novo-pi.com/saxenda.pdf.

Lorcaserin (Belviq) Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022529lbl.pdf.

Naltrexone HCl/Bupropion HCl Extended Release Prescribing Information (CONTRAVE). https://contrave.com/contrave-pi/.

Phentermine HCl/Topiramate Extended Release Prescribing Information (Qsymia). https://qsymia.com/patient/include/media/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf

Q1. Correct answer: D. Lorcaserin (Belviq).

Rationale

Lorcaserin may cause valvulopathy, attention, or memory disturbance. This patient has normal ECHO and does not work with heavy machinery. Given his other history, this may be the best choice for him. Naltrexone/bupropion extended release is contraindicated in patients with seizure disorder, chronic opioid use, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or antiepileptic drugs because bupropion lowers the seizure threshold. Liraglutide is contraindicated with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or MENII. In addition, GLP1 receptor agonists can increase the risk of pancreatitis in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Phentermine/topiramate can increase the risk of nephrolithiasis. All of these medications are contraindicated in pregnancy and in patients with hypersensitivity to the drug and drug class.

References

Bays HE et al. Obesity algorithm, presented by the Obesity Medical Association. 2016-2017. https://cmcoem.info/pdf/curso/evaluacion_preoperatoria/oma_obesity-algorithm.pdf.

Steelman M and Westman E. Obesity: Evaluation and Treatment Essentials. Boca Raton: CRC press, 2016. https://www.abom.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Obesity-Evaluation-and-Treatment-Essentials.pdf.

Liraglutide Prescribing Information (Saxenda). https://www.novo-pi.com/saxenda.pdf.

Lorcaserin (Belviq) Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022529lbl.pdf.

Naltrexone HCl/Bupropion HCl Extended Release Prescribing Information (CONTRAVE). https://contrave.com/contrave-pi/.

Phentermine HCl/Topiramate Extended Release Prescribing Information (Qsymia). https://qsymia.com/patient/include/media/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf

Q1. A 54-year-old male is referred to you for advice on weight-loss management. His body mass index is currently 37 kg/m2; he exercises regularly and is interested in starting medications for weight loss. He is a chronic alcoholic who has a history of pancreatitis in the past and a few admissions for management of alcohol withdrawal, which included seizures. However, he has maintained his job as a cook at the local diner. The only other history is kidney stones as a teenager. He recently visited his primary care physician who "cleared" him. He remembers going for a sonogram of the heart, which was normal. He claims that he has been depressed about his brother's recent diagnosis of thyroid cancer and has vowed to stop drinking and lose weight.

Which state had the lowest primary cesarean delivery rate (15.5%) in 2021?

[polldaddy:11183184]

[polldaddy:11183184]

[polldaddy:11183184]

What's your diagnosis?

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising from main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with inadvertent main pancreatic duct stenting.

The FNA was positive for carcinoma with abundant mucin, which, taken together with the imaging findings, was indicative of pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising from main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (M-IPMN).

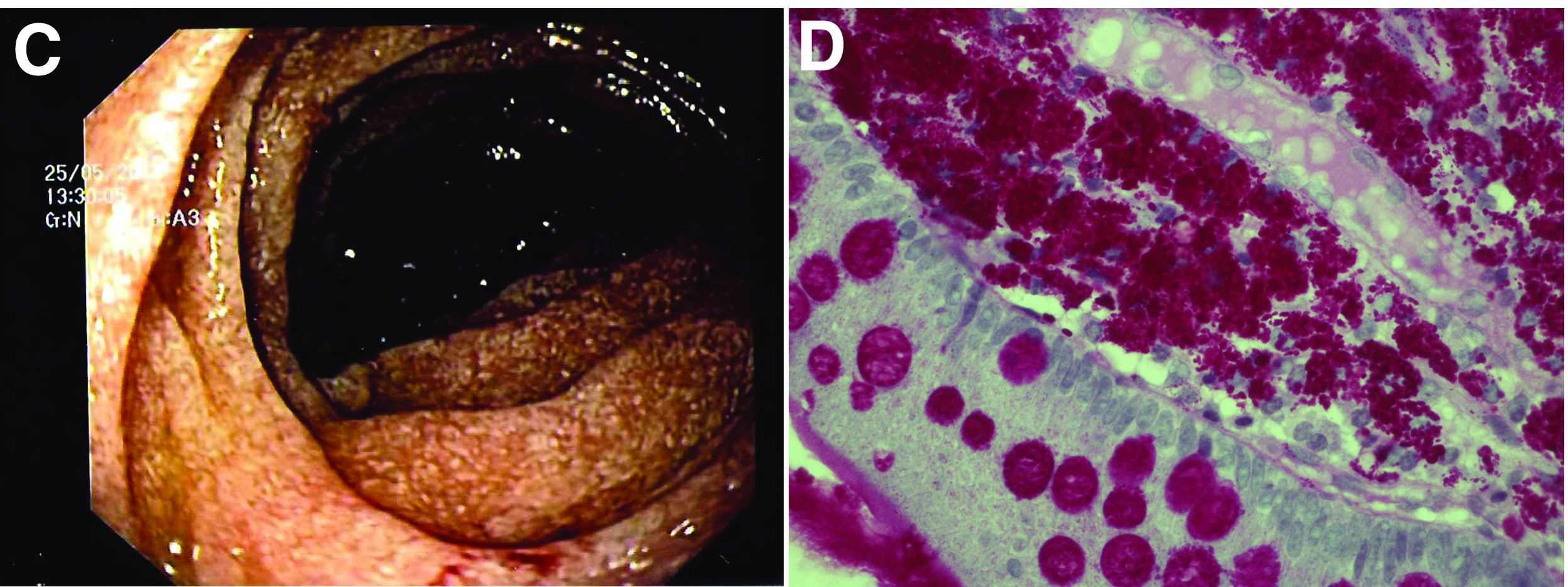

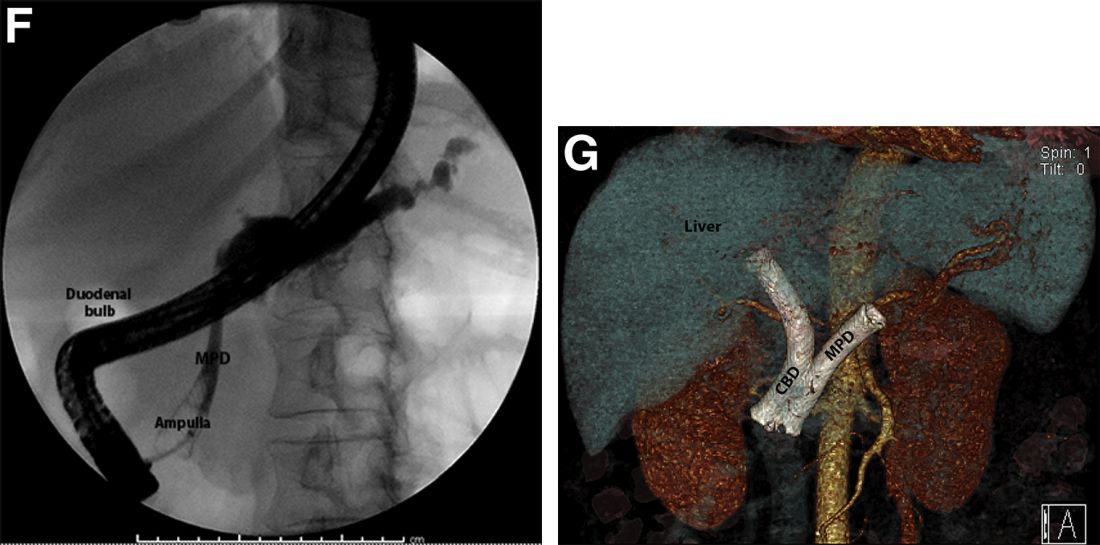

The post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) CT revealed inadvertent placement of the fully covered self-expanding metallic stent (fcSEMS) within the main pancreatic duct (MPD) stricture and persistent common bile duct (CBD) obstruction. On post hoc review of the fluoroscopic and cross-sectional imaging, it became evident that the massively dilated MPD was mistaken during ERCP for the CBD and left hepatic duct (Figure F). In addition, the patient also had several cysts within the liver (compatible with incidental polycystic liver disease), which further complicated real-time image interpretation.

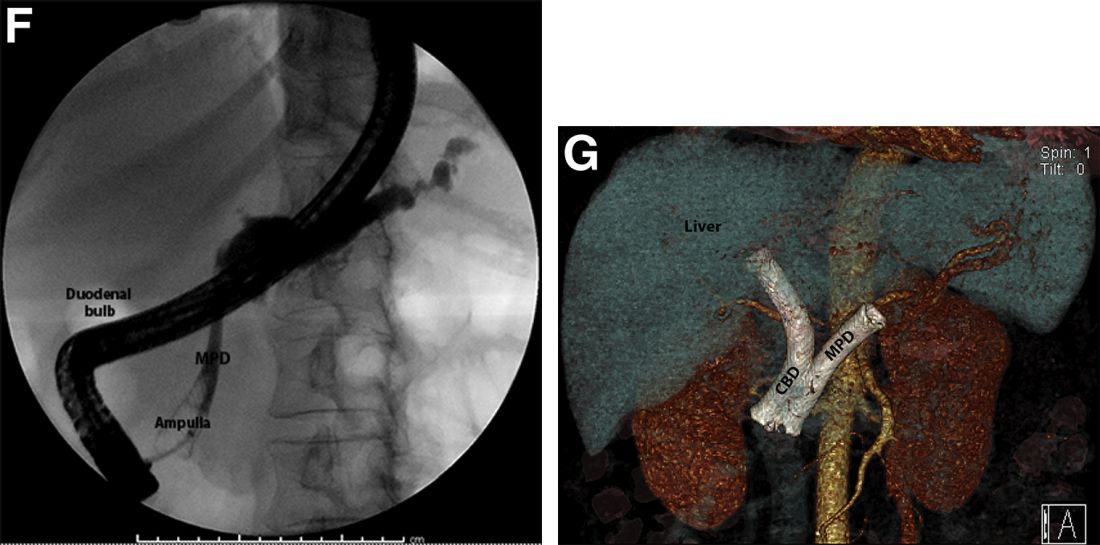

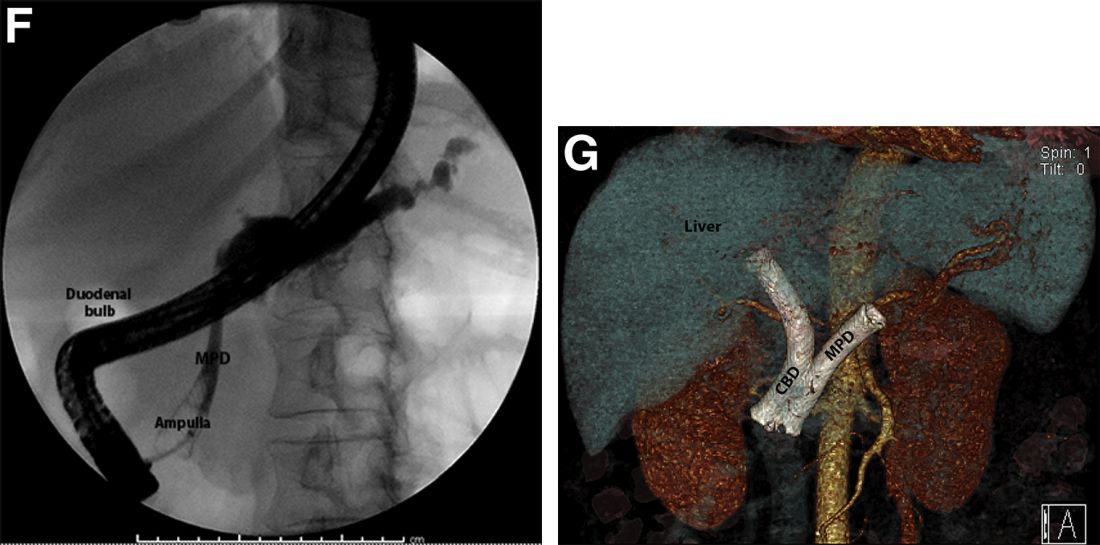

Based on multidisciplinary discussion, the precedent of a prior series of successful palliative MPD stenting in the setting of adenocarcinoma,1 and the notable improvement in the patient's steatorrhea and abdominal pain, the initially placed fcSEMS was left in situ across the MPD stricture, and a second fcSEMS was successfully deployed across the CBD stricture (Figure G), resulting in prompt improvement in serum liver tests. The patient was thereafter initiated on palliative chemotherapy with gemcitabine and abraxane and has maintained clinically stable disease for the last 9 months.

M-IPMN is a premalignant condition in which endoscopy plays an important role. In our patient, because of anatomic and morphologic abnormalities, including the massive dilation of the MPD and severe distal biliary compression in the context of an obstructing pancreatic head mass arising from M-IPMN, initial deployment of the fcSEMS occurred unwittingly into the MPD. Little is known about the impact of fcSEMS in the MPD in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, although in select cases, alleviation of pain caused by MPD obstruction and improvement in quality of life have been reported.2,3 In the case of our patient, fcSEMS placement in the MPD indeed led to symptomatic relief as manifested by a decrease in both diarrhea and pain and an increase in appetite; the addition of a fcSEMS in the CBD led to serum liver test normalization and permitted the initiation of chemotherapy. Further studies are needed to examine the outcomes of palliative MPD stenting in patients with obstructing pancreatic malignancies as well as the epidemiology and biology of M-IPMN and associated pancreatic adenocarcinoma in minority populations.

References

1. Tham TC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Apr;95(4):956-60.

2. Grimm IS, Baron TH. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jul;149(1):20-2.

3. Wehrmann T et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Dec;17(12):1395-400.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising from main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with inadvertent main pancreatic duct stenting.

The FNA was positive for carcinoma with abundant mucin, which, taken together with the imaging findings, was indicative of pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising from main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (M-IPMN).

The post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) CT revealed inadvertent placement of the fully covered self-expanding metallic stent (fcSEMS) within the main pancreatic duct (MPD) stricture and persistent common bile duct (CBD) obstruction. On post hoc review of the fluoroscopic and cross-sectional imaging, it became evident that the massively dilated MPD was mistaken during ERCP for the CBD and left hepatic duct (Figure F). In addition, the patient also had several cysts within the liver (compatible with incidental polycystic liver disease), which further complicated real-time image interpretation.

Based on multidisciplinary discussion, the precedent of a prior series of successful palliative MPD stenting in the setting of adenocarcinoma,1 and the notable improvement in the patient's steatorrhea and abdominal pain, the initially placed fcSEMS was left in situ across the MPD stricture, and a second fcSEMS was successfully deployed across the CBD stricture (Figure G), resulting in prompt improvement in serum liver tests. The patient was thereafter initiated on palliative chemotherapy with gemcitabine and abraxane and has maintained clinically stable disease for the last 9 months.

M-IPMN is a premalignant condition in which endoscopy plays an important role. In our patient, because of anatomic and morphologic abnormalities, including the massive dilation of the MPD and severe distal biliary compression in the context of an obstructing pancreatic head mass arising from M-IPMN, initial deployment of the fcSEMS occurred unwittingly into the MPD. Little is known about the impact of fcSEMS in the MPD in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, although in select cases, alleviation of pain caused by MPD obstruction and improvement in quality of life have been reported.2,3 In the case of our patient, fcSEMS placement in the MPD indeed led to symptomatic relief as manifested by a decrease in both diarrhea and pain and an increase in appetite; the addition of a fcSEMS in the CBD led to serum liver test normalization and permitted the initiation of chemotherapy. Further studies are needed to examine the outcomes of palliative MPD stenting in patients with obstructing pancreatic malignancies as well as the epidemiology and biology of M-IPMN and associated pancreatic adenocarcinoma in minority populations.

References

1. Tham TC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Apr;95(4):956-60.

2. Grimm IS, Baron TH. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jul;149(1):20-2.

3. Wehrmann T et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Dec;17(12):1395-400.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising from main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with inadvertent main pancreatic duct stenting.

The FNA was positive for carcinoma with abundant mucin, which, taken together with the imaging findings, was indicative of pancreatic adenocarcinoma arising from main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (M-IPMN).

The post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) CT revealed inadvertent placement of the fully covered self-expanding metallic stent (fcSEMS) within the main pancreatic duct (MPD) stricture and persistent common bile duct (CBD) obstruction. On post hoc review of the fluoroscopic and cross-sectional imaging, it became evident that the massively dilated MPD was mistaken during ERCP for the CBD and left hepatic duct (Figure F). In addition, the patient also had several cysts within the liver (compatible with incidental polycystic liver disease), which further complicated real-time image interpretation.

Based on multidisciplinary discussion, the precedent of a prior series of successful palliative MPD stenting in the setting of adenocarcinoma,1 and the notable improvement in the patient's steatorrhea and abdominal pain, the initially placed fcSEMS was left in situ across the MPD stricture, and a second fcSEMS was successfully deployed across the CBD stricture (Figure G), resulting in prompt improvement in serum liver tests. The patient was thereafter initiated on palliative chemotherapy with gemcitabine and abraxane and has maintained clinically stable disease for the last 9 months.

M-IPMN is a premalignant condition in which endoscopy plays an important role. In our patient, because of anatomic and morphologic abnormalities, including the massive dilation of the MPD and severe distal biliary compression in the context of an obstructing pancreatic head mass arising from M-IPMN, initial deployment of the fcSEMS occurred unwittingly into the MPD. Little is known about the impact of fcSEMS in the MPD in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, although in select cases, alleviation of pain caused by MPD obstruction and improvement in quality of life have been reported.2,3 In the case of our patient, fcSEMS placement in the MPD indeed led to symptomatic relief as manifested by a decrease in both diarrhea and pain and an increase in appetite; the addition of a fcSEMS in the CBD led to serum liver test normalization and permitted the initiation of chemotherapy. Further studies are needed to examine the outcomes of palliative MPD stenting in patients with obstructing pancreatic malignancies as well as the epidemiology and biology of M-IPMN and associated pancreatic adenocarcinoma in minority populations.

References

1. Tham TC et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Apr;95(4):956-60.

2. Grimm IS, Baron TH. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jul;149(1):20-2.

3. Wehrmann T et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Dec;17(12):1395-400.

A 69-year-old Filipino American woman presented with increasing epigastralgia, worsening appetite, jaundice, and oily diarrhea over the course of 3 months. Her past medical history consisted of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and osteopenia being managed with metformin, losartan, and atorvastatin, respectively.

Physical examination revealed she was thin (body mass index, 22 kg/m2) and jaundiced with moderate tenderness to epigastric palpation and 1+ peripheral pitting edema. Laboratory tests were significant for normal complete blood count and elevated alanine aminotransferase (113 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (235 U/L), bilirubin (7.3 mg/dL), international normalized ratio (1.3), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (7886 U/L). A CT scan of the abdomen revealed severe extrahepatic and intrahepatic ductal dilation, with a common bile duct (CBD) and main pancreatic duct (MPD) diameter of 2.5 and 1.7 cm, respectively, as well an infiltrating, malignant-appearing, 4.5-cm spheroid mass in the head of the pancreas (Figure A). The mass involved the superior mesenteric vein at the portal confluence and encased >50% of the superior mesenteric artery.

To further characterize these findings, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was performed, which additionally revealed multifocal cysts throughout the liver ranging from 0.5 to 5.0 cm in greatest diameter, as seen on maximal intensity projection algorithm (Figure B).

The patient was referred for same-session endoscopic ultrasound examination with fine needle aspiration (FNA) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for further diagnosis and treatment. Endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated a large, hypoechoic mass in the pancreatic head with severe CBD and MPD dilation proximally, corresponding with the cross-sectional imaging findings; FNA was performed. ERCP demonstrated a long, distal CBD stricture and what appeared to be nonopacification of the right hepatic ductal system; a 10 × 60-mm fully covered self-expanding metallic stent (fcSEMS) was placed across the stricture (Figure C, D). Over the subsequent 3 days, the patient's diarrhea resolved and epigastralgia improved; however, serum liver tests did not downtrend, thus prompting repeat imaging (Figure E).

Based on the patient's clinical history, cross-sectional imaging findings, and only partial response to therapeutic ERCP, what are the patient's likely diagnoses?

Guidelines vary on what age to begin screening for cervical cancer. What age do you typically recommend for patients?

[polldaddy:11135441]

[polldaddy:11135441]

[polldaddy:11135441]

Question 2

Q2. Correct answer: A. Reassurance and consideration of cow milk protein soy intolerance with elimination of these antigens in mother's diet.

Rationale

The differential diagnosis of hematochezia in infants is relatively small. The most likely considerations are anal fissures, vascular malformations, cow milk protein soy intolerance, bleeding diatheses, swallowed maternal blood in the first 1-2 days of life, and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. In the setting of an otherwise healthy term infant who presents with hematochezia without anorectal malformations, the most likely etiology is cow milk protein soy intolerance. This is an IgG-mediated disorder that does not necessarily construe other predilections to food allergies. Most infants outgrow this by 1 year of life or thereafter. In mother's who are breastfeeding, it is recommended that they eliminate both cow milk and soymilk proteins from their diet. There is a 70% cross-reactivity between cow milk and soymilk proteins. In infants who are formula feeding or those who do not respond to maternal elimination diets, it is recommended that they consume partially hydrolyzed or fully hydrolyzed formula. Such infants are usually able to tolerate cow and soy proteins later in life.

Reference

Mäkinen OE et al. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(3):339-49.

Q2. Correct answer: A. Reassurance and consideration of cow milk protein soy intolerance with elimination of these antigens in mother's diet.

Rationale

The differential diagnosis of hematochezia in infants is relatively small. The most likely considerations are anal fissures, vascular malformations, cow milk protein soy intolerance, bleeding diatheses, swallowed maternal blood in the first 1-2 days of life, and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. In the setting of an otherwise healthy term infant who presents with hematochezia without anorectal malformations, the most likely etiology is cow milk protein soy intolerance. This is an IgG-mediated disorder that does not necessarily construe other predilections to food allergies. Most infants outgrow this by 1 year of life or thereafter. In mother's who are breastfeeding, it is recommended that they eliminate both cow milk and soymilk proteins from their diet. There is a 70% cross-reactivity between cow milk and soymilk proteins. In infants who are formula feeding or those who do not respond to maternal elimination diets, it is recommended that they consume partially hydrolyzed or fully hydrolyzed formula. Such infants are usually able to tolerate cow and soy proteins later in life.

Reference

Mäkinen OE et al. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(3):339-49.

Q2. Correct answer: A. Reassurance and consideration of cow milk protein soy intolerance with elimination of these antigens in mother's diet.

Rationale

The differential diagnosis of hematochezia in infants is relatively small. The most likely considerations are anal fissures, vascular malformations, cow milk protein soy intolerance, bleeding diatheses, swallowed maternal blood in the first 1-2 days of life, and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. In the setting of an otherwise healthy term infant who presents with hematochezia without anorectal malformations, the most likely etiology is cow milk protein soy intolerance. This is an IgG-mediated disorder that does not necessarily construe other predilections to food allergies. Most infants outgrow this by 1 year of life or thereafter. In mother's who are breastfeeding, it is recommended that they eliminate both cow milk and soymilk proteins from their diet. There is a 70% cross-reactivity between cow milk and soymilk proteins. In infants who are formula feeding or those who do not respond to maternal elimination diets, it is recommended that they consume partially hydrolyzed or fully hydrolyzed formula. Such infants are usually able to tolerate cow and soy proteins later in life.

Reference

Mäkinen OE et al. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(3):339-49.

Q2. A 6-week-old otherwise healthy female term infant presents to the office for evaluation of hematochezia. Her pre- and perinatal course was uncomplicated. Her mother has been breastfeeding her and noted evidence of small streaks of blood in her diaper with some mucus over the last 1-2 weeks. There have been no associated fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. She is otherwise breastfeeding well, and her mother has not introduced any formulas. There is no report of bleeding diatheses. She has no bruising or other abnormalities. Her mother is very concerned.