User login

Question 1

Q1. Correct answer: A. Normal Ph/Impedance probe findings during sleeping.

Rationale

Rumination syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disorder that can present in all age groups. The true prevalence of the disorder is unknown, but the condition can be seen more commonly in patients with developmental disorders and other high-risk groups like teenage females. The ROME IV criteria for the condition include at least 2 months of the following: Repeated regurgitation and rechewing or expulsion of food that begins soon after eating and stops with sleeping, is not proceeded by retching, and has no other clear etiology for symptoms. This patient is at higher risk for rumination syndrome with her developmental differences. Her painless regurgitation after eating meets criteria for the condition. Prolonged high-resolution esophageal manometry can identify specific subgroups of rumination. Antroduodenal manometry can detect simultaneous contractions called R-waves that can be seen in some patients with rumination syndrome. Since regurgitation stops with sleeping, pH/Impedance probes demonstrate resolution of symptoms with sleep. The condition is primarily diagnosed clinically, with other studies performed as clinically indicated. Treatment typically consists of behavioral management.

Reference

Hyams J et al. Gastroenterology. 2006 Apr;130(5):1527-37.

Q1. Correct answer: A. Normal Ph/Impedance probe findings during sleeping.

Rationale

Rumination syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disorder that can present in all age groups. The true prevalence of the disorder is unknown, but the condition can be seen more commonly in patients with developmental disorders and other high-risk groups like teenage females. The ROME IV criteria for the condition include at least 2 months of the following: Repeated regurgitation and rechewing or expulsion of food that begins soon after eating and stops with sleeping, is not proceeded by retching, and has no other clear etiology for symptoms. This patient is at higher risk for rumination syndrome with her developmental differences. Her painless regurgitation after eating meets criteria for the condition. Prolonged high-resolution esophageal manometry can identify specific subgroups of rumination. Antroduodenal manometry can detect simultaneous contractions called R-waves that can be seen in some patients with rumination syndrome. Since regurgitation stops with sleeping, pH/Impedance probes demonstrate resolution of symptoms with sleep. The condition is primarily diagnosed clinically, with other studies performed as clinically indicated. Treatment typically consists of behavioral management.

Reference

Hyams J et al. Gastroenterology. 2006 Apr;130(5):1527-37.

Q1. Correct answer: A. Normal Ph/Impedance probe findings during sleeping.

Rationale

Rumination syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disorder that can present in all age groups. The true prevalence of the disorder is unknown, but the condition can be seen more commonly in patients with developmental disorders and other high-risk groups like teenage females. The ROME IV criteria for the condition include at least 2 months of the following: Repeated regurgitation and rechewing or expulsion of food that begins soon after eating and stops with sleeping, is not proceeded by retching, and has no other clear etiology for symptoms. This patient is at higher risk for rumination syndrome with her developmental differences. Her painless regurgitation after eating meets criteria for the condition. Prolonged high-resolution esophageal manometry can identify specific subgroups of rumination. Antroduodenal manometry can detect simultaneous contractions called R-waves that can be seen in some patients with rumination syndrome. Since regurgitation stops with sleeping, pH/Impedance probes demonstrate resolution of symptoms with sleep. The condition is primarily diagnosed clinically, with other studies performed as clinically indicated. Treatment typically consists of behavioral management.

Reference

Hyams J et al. Gastroenterology. 2006 Apr;130(5):1527-37.

Q1. A 14-year-old female with a history of cerebral palsy presents for evaluation due to recurrent regurgitation. By report, she is regurgitating food into her mouth several times daily following meals. Her parents report that the regurgitation does not appear to be painful.

Clinician experience has been cited for declining operative vaginal delivery rates. Are you comfortable performing OVD as an alternative to cesarean?

[polldaddy:11086729]

[polldaddy:11086729]

[polldaddy:11086729]

Vegetative Plaques on the Face

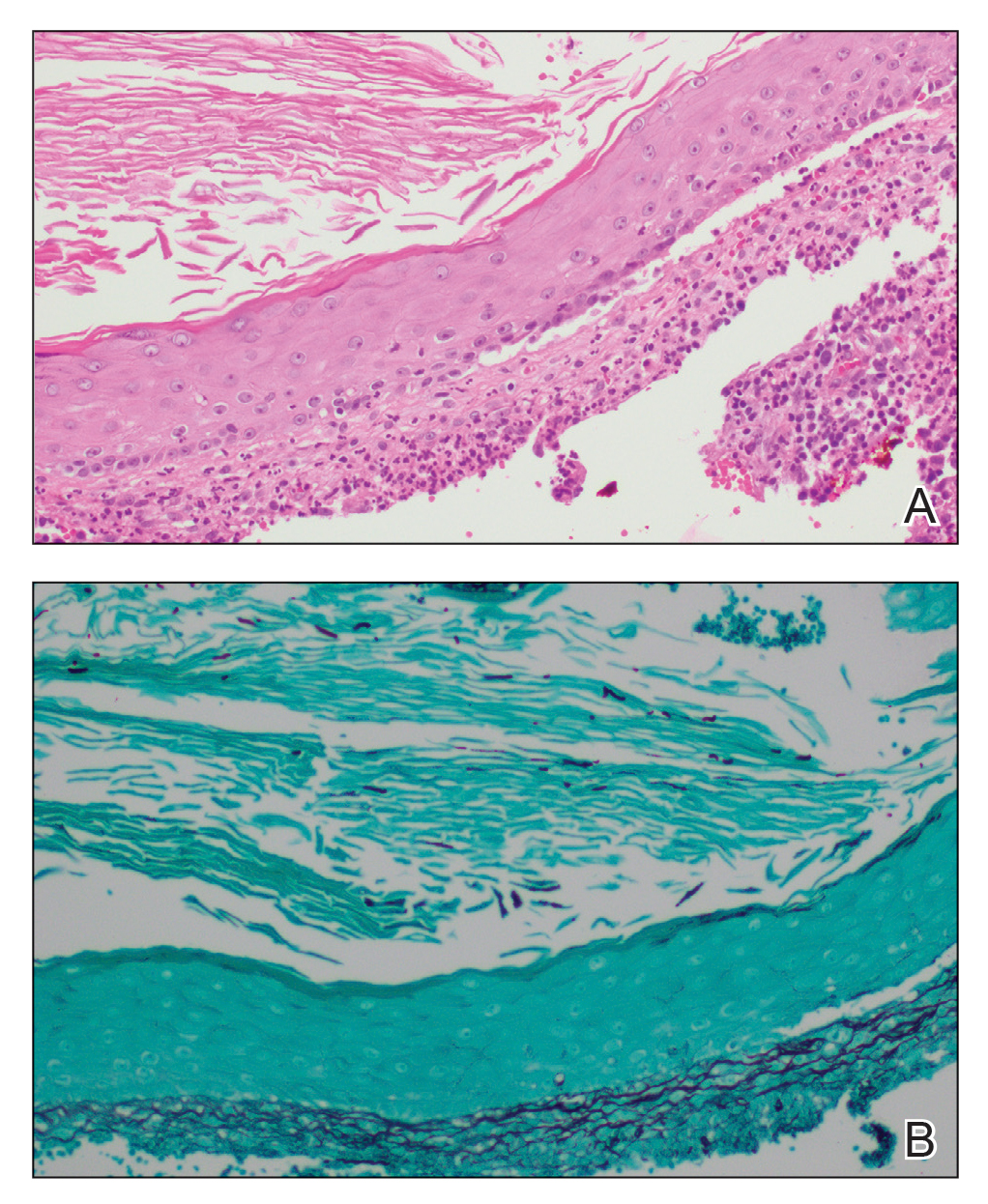

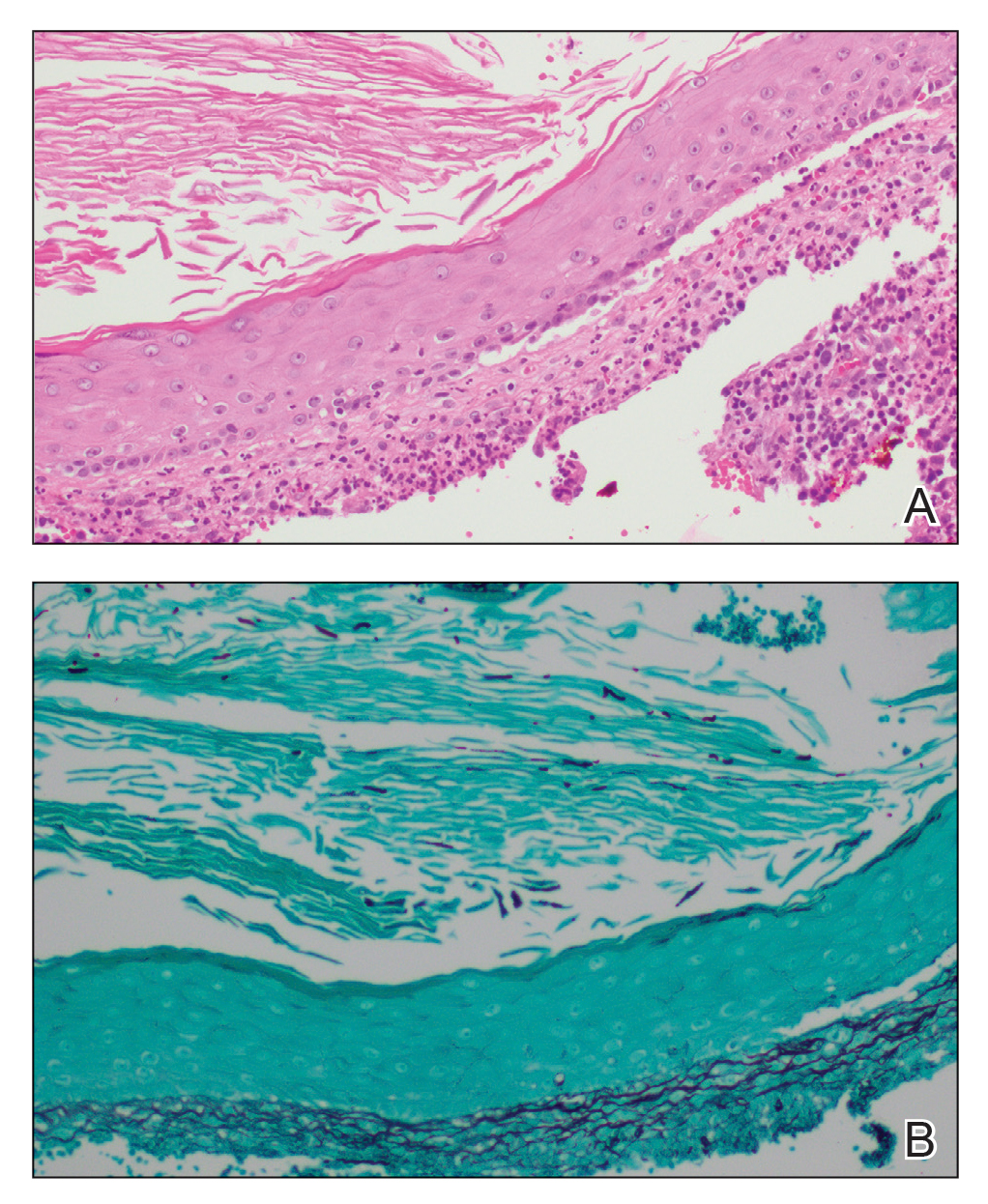

THE DIAGNOSIS: Vegetative Majocchi Granuloma

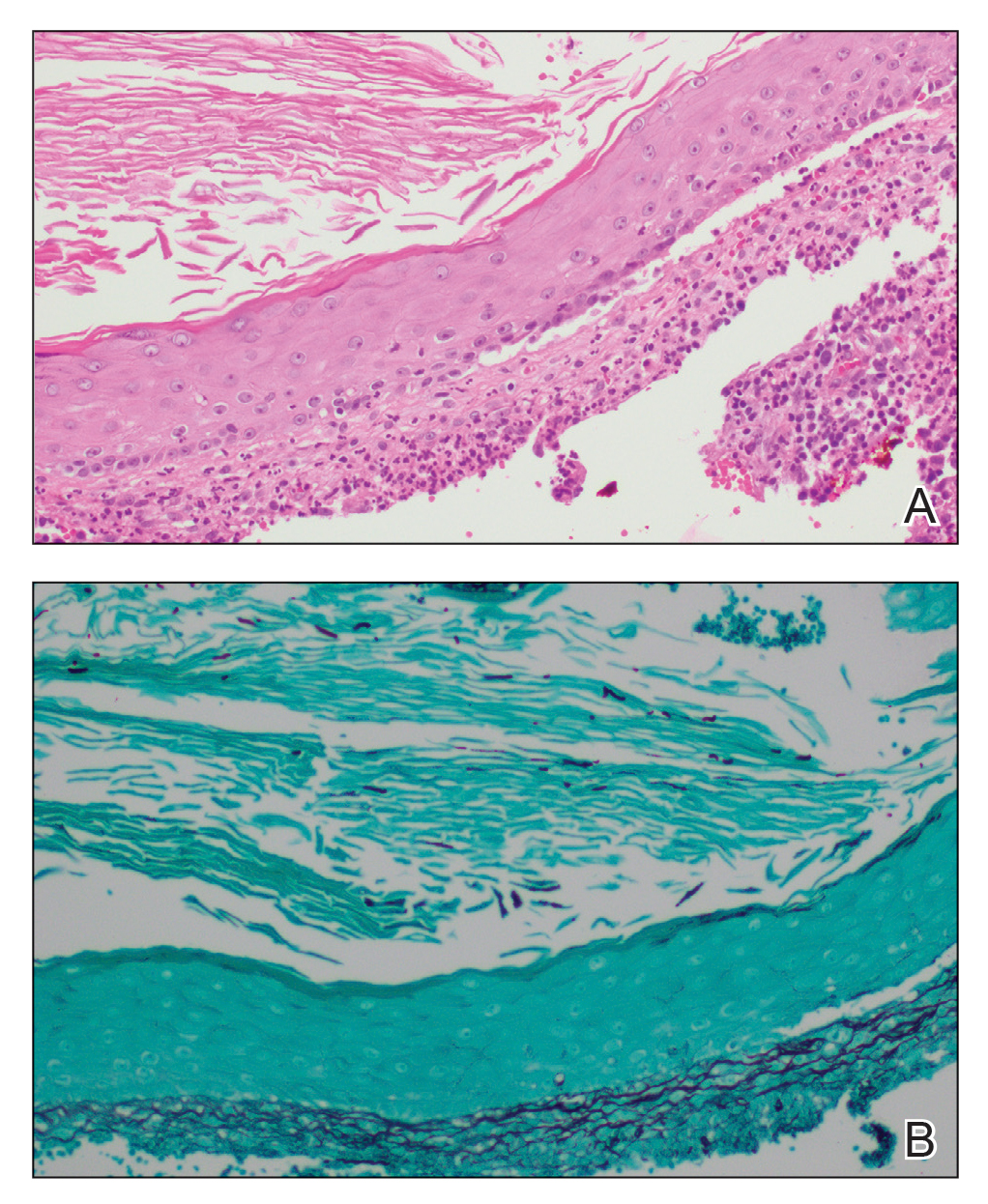

A biopsy and tissue culture showed acute dermal inflammation with granulomatous features and numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 1A), which were confirmed on GrocottGomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 1B). Gram and Fite stains were negative for bacteria. A tissue culture speciated Trichophyton rubrum, which led to a diagnosis of deep dermatophyte infection (Majocchi granuloma) with a highly unusual clinical presentation of vegetative plaques. Predisposing factors included treatment with topical corticosteroids and possibly poor health and nutritional status at baseline. Our patient was treated with fluconazole 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, with near resolution of lesions at 3-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Dermatophytes are a common cause of superficial skin infections. The classic morphology consists of an annular scaly plaque; however, a wide variety of presentations have been observed (eg, verrucous, vesicular, pustular, granulomatous). Therefore, dermatophyte infections often mimic other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, rosacea, psoriasis, bacterial abscess, erythema gyratum repens, lupus, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, Hailey-Hailey disease, scarring alopecia, and syphilis.1

Notably, when dermatophytes grow downward along hair follicles causing deeper infection, disruption of the follicular wall can lead to an excessive inflammatory response with granulomatous features.2 Risk factors include cutaneous trauma, long-standing infection, immunocompromise, and treatment with topical corticosteroids.3 This disease evolution clinically appears as a nodule or infiltrated plaque, often without scale. The most well-known example is a kerion on the scalp. Elsewhere on the body, lesions often are termed Majocchi granulomas.2

Vegetative plaques, as seen in our patient, are a highly unusual morphology for deep tinea infection. Guanziroli et al4 reported a case of vegetative lesions on the forearm of a 67-year-old immunocompromised man that were successfully treated with a 3-month course of oral terbinafine after Trichophyton verrucosum was isolated. Skorepova et al5 reported a case of pyoderma vegetans triggered by recurrent Trichophyton mentagrophytes on the dorsal hands of a 64-year-old man with immunoglobulin deficiency of unknown etiology. The lesions were successfully treated with a prolonged course of doxycycline, topical triamcinolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin following 2 initial courses of terbinafine.

The differential diagnosis for vegetative lesions includes pemphigus vegetans, a vegetative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum; halogenoderma; and a variety of infections, including dimorphic fungi (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis), blastomycosislike pyoderma (bacterial), and candidiasis.6 These conditions usually can be distinguished based on histopathology. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans presents with pustules and vegetative lesions, as in our patient, but usually is more diffuse and favors the intertriginous areas. Histology likely would reveal foci of acantholysis and eosinophils. Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum favors the trunk, particularly in sites of surgical trauma. In our patient, no lesions were present near the abdominal surgical sites, and there was no antecedent cribriform ulceration. Halogenoderma was a strong initial consideration given the localization, presence of large pustules, and history of numerous contrast computed tomography studies; however, our patient’s iodine levels were normal. Infectious etiologies including dimorphic fungi and blastomycosislike pyoderma generally are not restricted to the head and neck, and tissue culture helps exclude them. Vegetative lesions may occur in the setting of other infections, and tissue culture may be necessary to differentiate them if histopathology is not suggestive.

Deep dermatophyte infections require treatment with oral antifungals, as topicals do not penetrate adequately into the hair follicles. Exact regimens vary, but generally oral terbinafine or an oral azole (except ketoconazole) is administered for 2 to 6 weeks, with immunocompromise necessitating longer courses.

We present a rare case of vegetative Majocchi granuloma secondary to T rubrum infection. A dermatophyte infection should be included in the differential for vegetative lesions, especially in dense hair-bearing areas such as the beard. Treatment generally is straightforward with oral antifungals.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, et al. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:410-415.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- Jevremovic L, Ilijin I, Kostic K, et al. Pyoderma vegetans—a case report. Serbian J Dermatol Venereol. 2017;9:22-28.

- Guanziroli E, Pavia G, Guttadauro A, et al. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum in an immunosuppressed patient: successful outcome with terbinafine. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:543-545.

- Skorepová M, Stuchlík D. Chronic pyoderma vegetans triggered by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2006;49:143-144.

- Reinholz M, Hermans C, Dietrich A, et al. A case of cutaneous vegetating candidiasis in a patient with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:537-539.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Vegetative Majocchi Granuloma

A biopsy and tissue culture showed acute dermal inflammation with granulomatous features and numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 1A), which were confirmed on GrocottGomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 1B). Gram and Fite stains were negative for bacteria. A tissue culture speciated Trichophyton rubrum, which led to a diagnosis of deep dermatophyte infection (Majocchi granuloma) with a highly unusual clinical presentation of vegetative plaques. Predisposing factors included treatment with topical corticosteroids and possibly poor health and nutritional status at baseline. Our patient was treated with fluconazole 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, with near resolution of lesions at 3-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Dermatophytes are a common cause of superficial skin infections. The classic morphology consists of an annular scaly plaque; however, a wide variety of presentations have been observed (eg, verrucous, vesicular, pustular, granulomatous). Therefore, dermatophyte infections often mimic other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, rosacea, psoriasis, bacterial abscess, erythema gyratum repens, lupus, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, Hailey-Hailey disease, scarring alopecia, and syphilis.1

Notably, when dermatophytes grow downward along hair follicles causing deeper infection, disruption of the follicular wall can lead to an excessive inflammatory response with granulomatous features.2 Risk factors include cutaneous trauma, long-standing infection, immunocompromise, and treatment with topical corticosteroids.3 This disease evolution clinically appears as a nodule or infiltrated plaque, often without scale. The most well-known example is a kerion on the scalp. Elsewhere on the body, lesions often are termed Majocchi granulomas.2

Vegetative plaques, as seen in our patient, are a highly unusual morphology for deep tinea infection. Guanziroli et al4 reported a case of vegetative lesions on the forearm of a 67-year-old immunocompromised man that were successfully treated with a 3-month course of oral terbinafine after Trichophyton verrucosum was isolated. Skorepova et al5 reported a case of pyoderma vegetans triggered by recurrent Trichophyton mentagrophytes on the dorsal hands of a 64-year-old man with immunoglobulin deficiency of unknown etiology. The lesions were successfully treated with a prolonged course of doxycycline, topical triamcinolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin following 2 initial courses of terbinafine.

The differential diagnosis for vegetative lesions includes pemphigus vegetans, a vegetative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum; halogenoderma; and a variety of infections, including dimorphic fungi (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis), blastomycosislike pyoderma (bacterial), and candidiasis.6 These conditions usually can be distinguished based on histopathology. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans presents with pustules and vegetative lesions, as in our patient, but usually is more diffuse and favors the intertriginous areas. Histology likely would reveal foci of acantholysis and eosinophils. Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum favors the trunk, particularly in sites of surgical trauma. In our patient, no lesions were present near the abdominal surgical sites, and there was no antecedent cribriform ulceration. Halogenoderma was a strong initial consideration given the localization, presence of large pustules, and history of numerous contrast computed tomography studies; however, our patient’s iodine levels were normal. Infectious etiologies including dimorphic fungi and blastomycosislike pyoderma generally are not restricted to the head and neck, and tissue culture helps exclude them. Vegetative lesions may occur in the setting of other infections, and tissue culture may be necessary to differentiate them if histopathology is not suggestive.

Deep dermatophyte infections require treatment with oral antifungals, as topicals do not penetrate adequately into the hair follicles. Exact regimens vary, but generally oral terbinafine or an oral azole (except ketoconazole) is administered for 2 to 6 weeks, with immunocompromise necessitating longer courses.

We present a rare case of vegetative Majocchi granuloma secondary to T rubrum infection. A dermatophyte infection should be included in the differential for vegetative lesions, especially in dense hair-bearing areas such as the beard. Treatment generally is straightforward with oral antifungals.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Vegetative Majocchi Granuloma

A biopsy and tissue culture showed acute dermal inflammation with granulomatous features and numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 1A), which were confirmed on GrocottGomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 1B). Gram and Fite stains were negative for bacteria. A tissue culture speciated Trichophyton rubrum, which led to a diagnosis of deep dermatophyte infection (Majocchi granuloma) with a highly unusual clinical presentation of vegetative plaques. Predisposing factors included treatment with topical corticosteroids and possibly poor health and nutritional status at baseline. Our patient was treated with fluconazole 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, with near resolution of lesions at 3-week follow-up (Figure 2).

Dermatophytes are a common cause of superficial skin infections. The classic morphology consists of an annular scaly plaque; however, a wide variety of presentations have been observed (eg, verrucous, vesicular, pustular, granulomatous). Therefore, dermatophyte infections often mimic other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis, rosacea, psoriasis, bacterial abscess, erythema gyratum repens, lupus, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, Hailey-Hailey disease, scarring alopecia, and syphilis.1

Notably, when dermatophytes grow downward along hair follicles causing deeper infection, disruption of the follicular wall can lead to an excessive inflammatory response with granulomatous features.2 Risk factors include cutaneous trauma, long-standing infection, immunocompromise, and treatment with topical corticosteroids.3 This disease evolution clinically appears as a nodule or infiltrated plaque, often without scale. The most well-known example is a kerion on the scalp. Elsewhere on the body, lesions often are termed Majocchi granulomas.2

Vegetative plaques, as seen in our patient, are a highly unusual morphology for deep tinea infection. Guanziroli et al4 reported a case of vegetative lesions on the forearm of a 67-year-old immunocompromised man that were successfully treated with a 3-month course of oral terbinafine after Trichophyton verrucosum was isolated. Skorepova et al5 reported a case of pyoderma vegetans triggered by recurrent Trichophyton mentagrophytes on the dorsal hands of a 64-year-old man with immunoglobulin deficiency of unknown etiology. The lesions were successfully treated with a prolonged course of doxycycline, topical triamcinolone, and intravenous immunoglobulin following 2 initial courses of terbinafine.

The differential diagnosis for vegetative lesions includes pemphigus vegetans, a vegetative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum; halogenoderma; and a variety of infections, including dimorphic fungi (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis), blastomycosislike pyoderma (bacterial), and candidiasis.6 These conditions usually can be distinguished based on histopathology. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans presents with pustules and vegetative lesions, as in our patient, but usually is more diffuse and favors the intertriginous areas. Histology likely would reveal foci of acantholysis and eosinophils. Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum favors the trunk, particularly in sites of surgical trauma. In our patient, no lesions were present near the abdominal surgical sites, and there was no antecedent cribriform ulceration. Halogenoderma was a strong initial consideration given the localization, presence of large pustules, and history of numerous contrast computed tomography studies; however, our patient’s iodine levels were normal. Infectious etiologies including dimorphic fungi and blastomycosislike pyoderma generally are not restricted to the head and neck, and tissue culture helps exclude them. Vegetative lesions may occur in the setting of other infections, and tissue culture may be necessary to differentiate them if histopathology is not suggestive.

Deep dermatophyte infections require treatment with oral antifungals, as topicals do not penetrate adequately into the hair follicles. Exact regimens vary, but generally oral terbinafine or an oral azole (except ketoconazole) is administered for 2 to 6 weeks, with immunocompromise necessitating longer courses.

We present a rare case of vegetative Majocchi granuloma secondary to T rubrum infection. A dermatophyte infection should be included in the differential for vegetative lesions, especially in dense hair-bearing areas such as the beard. Treatment generally is straightforward with oral antifungals.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, et al. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:410-415.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- Jevremovic L, Ilijin I, Kostic K, et al. Pyoderma vegetans—a case report. Serbian J Dermatol Venereol. 2017;9:22-28.

- Guanziroli E, Pavia G, Guttadauro A, et al. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum in an immunosuppressed patient: successful outcome with terbinafine. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:543-545.

- Skorepová M, Stuchlík D. Chronic pyoderma vegetans triggered by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2006;49:143-144.

- Reinholz M, Hermans C, Dietrich A, et al. A case of cutaneous vegetating candidiasis in a patient with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:537-539.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, et al. Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypica in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:410-415.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- Jevremovic L, Ilijin I, Kostic K, et al. Pyoderma vegetans—a case report. Serbian J Dermatol Venereol. 2017;9:22-28.

- Guanziroli E, Pavia G, Guttadauro A, et al. Deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton verrucosum in an immunosuppressed patient: successful outcome with terbinafine. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:543-545.

- Skorepová M, Stuchlík D. Chronic pyoderma vegetans triggered by Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2006;49:143-144.

- Reinholz M, Hermans C, Dietrich A, et al. A case of cutaneous vegetating candidiasis in a patient with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:537-539.

An 86-year-old man was admitted to the hospital for sigmoid colon perforation secondary to ischemic colitis. His medical history consisted of sequelae from atherosclerotic vascular disease. He had no known personal or family history of skin disease. His bowel perforation was surgically repaired, and his clinical status was stabilized, enabling transfer to a transitional care hospital. His course was complicated by delayed healing of the midline abdominal surgical wounds, leading to multiple computed tomography studies with iodinated contrast. One week following arrival at the transitional care hospital, he was noted to have a pustular rash on the face. He was empirically treated with topical steroids, mupirocin, and sulfacetamide. The rash did not improve, and the appearance changed, at which point dermatology was consulted. On evaluation, the patient was afebrile with a normal white blood cell count. Physical examination revealed gray-brown, moist, vegetative plaques on the cheeks with a few large pustules as well as similar-appearing lesions on the neck and upper chest. Attempted removal of a portion of the plaque left an erosion.

Question 2

Correct answer: A. Intravenous proton pump inhibitor drip.

Rationale

It is important to understand the initial management of patients with bleeding esophageal varices. With voluminous hematemesis, especially from a proximal source like the esophagus, airway protection is crucial so this patient should be intubated. Patients like this are at high risk to develop infected ascites so IV antibiotics should be given. Antibiotics have been shown to decrease mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted with GI bleeding. Somatostatin analogs decrease portal inflow by causing splanchnic vasoconstriction and have been proven to achieve hemostasis and decrease the risk of rebleeding. One has to be cautious with resuscitation efforts, as excessive resuscitation can lead to accelerated bleeding due to increased portal pressures. However, this patient's Hemoglobin concentration is well below the threshold that warrants transfusion, so giving him PRBCs is appropriate. In the acute setting of an upper GI bleed, proton pump inhibitors work to help optimize platelet function by increasing gastric pH. Since the source here is varices in the more pH neutral esophageal environment, intravenous PPI likely has little effect in the acute setting. However after band ligation is performed, it may help decrease the risk of forming post-banding ulcers. Since this patient's banding was performed a month ago, this episode of bleeding is more likely to be from recurrent varices than from a post-banding ulcer.

References

Garcia-Tsao G et al. Hepatology. 2007 Sep;46(3):922-38.

Tripathi D et al. Gut. 2015 Nov;64(11):1680-704.

Correct answer: A. Intravenous proton pump inhibitor drip.

Rationale

It is important to understand the initial management of patients with bleeding esophageal varices. With voluminous hematemesis, especially from a proximal source like the esophagus, airway protection is crucial so this patient should be intubated. Patients like this are at high risk to develop infected ascites so IV antibiotics should be given. Antibiotics have been shown to decrease mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted with GI bleeding. Somatostatin analogs decrease portal inflow by causing splanchnic vasoconstriction and have been proven to achieve hemostasis and decrease the risk of rebleeding. One has to be cautious with resuscitation efforts, as excessive resuscitation can lead to accelerated bleeding due to increased portal pressures. However, this patient's Hemoglobin concentration is well below the threshold that warrants transfusion, so giving him PRBCs is appropriate. In the acute setting of an upper GI bleed, proton pump inhibitors work to help optimize platelet function by increasing gastric pH. Since the source here is varices in the more pH neutral esophageal environment, intravenous PPI likely has little effect in the acute setting. However after band ligation is performed, it may help decrease the risk of forming post-banding ulcers. Since this patient's banding was performed a month ago, this episode of bleeding is more likely to be from recurrent varices than from a post-banding ulcer.

References

Garcia-Tsao G et al. Hepatology. 2007 Sep;46(3):922-38.

Tripathi D et al. Gut. 2015 Nov;64(11):1680-704.

Correct answer: A. Intravenous proton pump inhibitor drip.

Rationale

It is important to understand the initial management of patients with bleeding esophageal varices. With voluminous hematemesis, especially from a proximal source like the esophagus, airway protection is crucial so this patient should be intubated. Patients like this are at high risk to develop infected ascites so IV antibiotics should be given. Antibiotics have been shown to decrease mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted with GI bleeding. Somatostatin analogs decrease portal inflow by causing splanchnic vasoconstriction and have been proven to achieve hemostasis and decrease the risk of rebleeding. One has to be cautious with resuscitation efforts, as excessive resuscitation can lead to accelerated bleeding due to increased portal pressures. However, this patient's Hemoglobin concentration is well below the threshold that warrants transfusion, so giving him PRBCs is appropriate. In the acute setting of an upper GI bleed, proton pump inhibitors work to help optimize platelet function by increasing gastric pH. Since the source here is varices in the more pH neutral esophageal environment, intravenous PPI likely has little effect in the acute setting. However after band ligation is performed, it may help decrease the risk of forming post-banding ulcers. Since this patient's banding was performed a month ago, this episode of bleeding is more likely to be from recurrent varices than from a post-banding ulcer.

References

Garcia-Tsao G et al. Hepatology. 2007 Sep;46(3):922-38.

Tripathi D et al. Gut. 2015 Nov;64(11):1680-704.

Q2. A 52-year-old man with NASH-cirrhosis is admitted to the ICU with red hematemesis and hemodynamic instability. For the past few months, he has been maintained on diuretics but has still required frequent paracenteses for ascites management. An upper endoscopy 44 weeks ago revealed only large esophageal varices that were incompletely eradicated with banding, but the patient did not show up for his scheduled repeat upper endoscopy last week. His initial hemoglobin is 5.8 g/dL. His INR is 1.8, and his platelet count is 94K.

Question 1

Correct answer: A. Diphyllobothrium latum.

Rationale

This is likely a tapeworm infection with Diphyllobothrium latum. D. latum infection can be acquired from ingesting certain forms of freshwater fish, and those who consume raw fish, including sushi, are at increased risk. The classical manifestation of infection with D. latum is megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency. D. latum has a unique affinity for vitamin B12 and therefore competes with the host for absorption. Humans become infected with Taenia by ingesting raw or undercooked infected meat containing cysticerci. Infection with Hymenolepis is common in children secondary to breaches in fecal-oral hygiene. Most infections are asymptomatic.

Reference

Webb C, Cabada MM. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017 Oct;30(5):504-10.

Correct answer: A. Diphyllobothrium latum.

Rationale

This is likely a tapeworm infection with Diphyllobothrium latum. D. latum infection can be acquired from ingesting certain forms of freshwater fish, and those who consume raw fish, including sushi, are at increased risk. The classical manifestation of infection with D. latum is megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency. D. latum has a unique affinity for vitamin B12 and therefore competes with the host for absorption. Humans become infected with Taenia by ingesting raw or undercooked infected meat containing cysticerci. Infection with Hymenolepis is common in children secondary to breaches in fecal-oral hygiene. Most infections are asymptomatic.

Reference

Webb C, Cabada MM. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017 Oct;30(5):504-10.

Correct answer: A. Diphyllobothrium latum.

Rationale

This is likely a tapeworm infection with Diphyllobothrium latum. D. latum infection can be acquired from ingesting certain forms of freshwater fish, and those who consume raw fish, including sushi, are at increased risk. The classical manifestation of infection with D. latum is megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency. D. latum has a unique affinity for vitamin B12 and therefore competes with the host for absorption. Humans become infected with Taenia by ingesting raw or undercooked infected meat containing cysticerci. Infection with Hymenolepis is common in children secondary to breaches in fecal-oral hygiene. Most infections are asymptomatic.

Reference

Webb C, Cabada MM. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017 Oct;30(5):504-10.

Q1. A 36-year-old man presents to the clinic with a history of diarrhea and significant fatigue for the last 2 months. He has no significant past medical history and works as a chef in a local sushi bar. He complains of six to seven watery stools daily with nocturnal symptoms. Diarrhea is associated with abdominal cramps, and he denies any passage of blood. His physical examination, including vital signs, is unremarkable. Laboratory investigation reveals 9.8 g/dL hemoglobin, with a mean corpuscular volume 110 fL. Peripheral eosinophilia is also noted. A stool sample is sent to the lab and is pending.

Woman presents with weight loss and nausea

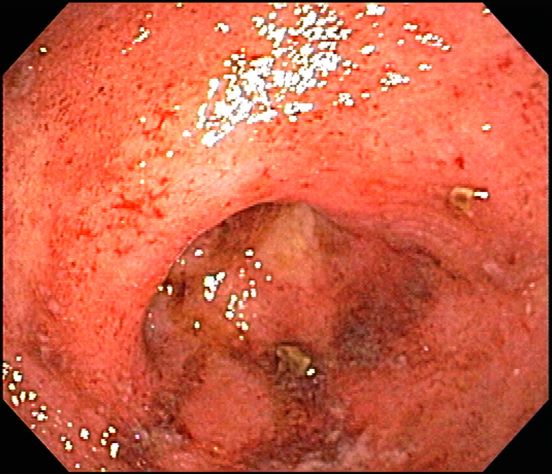

It is likely that the polypoid appearance of the colonic lining is a result of chronic inflammation of longstanding Crohn disease with an ileocolonic manifestation. Crohn disease is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by cycles of relapse and remission. These asymptomatic periods can last for several months up to a few years, as reported by the patient in this case. Up to 50% of cases of Crohn disease are characterized by ileocolitis, or inflammation of the ileum and the colon. Although postinflammatory polyps are a cancer risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease and pseudopolyps are associated with severe disease, their appearance is not necessarily a poor prognostic factor.

When assessing ongoing disease activity in ileocolonic Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis, colonoscopy represents the first-line approach. Endoscopic visualization and biopsy are critical components of the diagnosis. Alternatively, cross-sectional imaging can be used to assess disease phenotype. In addition, plain radiography or a CT scan of the abdomen can identify bowel obstruction and scanning of the pelvis can detect any intra-abdominal abscesses. Ulcerative colitis looms large in the differential diagnosis. Although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease, they are uncommon or rare in ulcerative colitis, although bleeding is observed much more frequently in ulcerative colitis.

Treatment of Crohn disease is based on the severity, location, and subtype (inflammatory, stricturing, or penetrating). There is also now a focus on determining which patients are at risk for a more severe disease course and may require earlier and more aggressive therapies. Crohn disease is primarily managed through the introduction of early immunosuppressive or combination therapy with biologic agents in high-risk patients, as well as complementary diet modification. Although most patients will ultimately undergo surgery, there is no curative approach, unlike in ulcerative colitis.

In its clinical care pathway, the American Gastroenterological Association supports a top-down approach to therapy for adult patients with moderate to severe luminal Crohn disease (defining moderate to severe disease as having a Crohn Disease Activity Index score of 220 or higher, or having a high risk of complications). This approach supports the early use of biologic agents, with or without immunomodulators, over a stepwise strategy. The patient’s response to this new regimen should be determined in the 12-week period after the initiation of therapy. Endoscopy or transmural responses to therapy should be assessed after 6 months.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

It is likely that the polypoid appearance of the colonic lining is a result of chronic inflammation of longstanding Crohn disease with an ileocolonic manifestation. Crohn disease is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by cycles of relapse and remission. These asymptomatic periods can last for several months up to a few years, as reported by the patient in this case. Up to 50% of cases of Crohn disease are characterized by ileocolitis, or inflammation of the ileum and the colon. Although postinflammatory polyps are a cancer risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease and pseudopolyps are associated with severe disease, their appearance is not necessarily a poor prognostic factor.

When assessing ongoing disease activity in ileocolonic Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis, colonoscopy represents the first-line approach. Endoscopic visualization and biopsy are critical components of the diagnosis. Alternatively, cross-sectional imaging can be used to assess disease phenotype. In addition, plain radiography or a CT scan of the abdomen can identify bowel obstruction and scanning of the pelvis can detect any intra-abdominal abscesses. Ulcerative colitis looms large in the differential diagnosis. Although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease, they are uncommon or rare in ulcerative colitis, although bleeding is observed much more frequently in ulcerative colitis.

Treatment of Crohn disease is based on the severity, location, and subtype (inflammatory, stricturing, or penetrating). There is also now a focus on determining which patients are at risk for a more severe disease course and may require earlier and more aggressive therapies. Crohn disease is primarily managed through the introduction of early immunosuppressive or combination therapy with biologic agents in high-risk patients, as well as complementary diet modification. Although most patients will ultimately undergo surgery, there is no curative approach, unlike in ulcerative colitis.

In its clinical care pathway, the American Gastroenterological Association supports a top-down approach to therapy for adult patients with moderate to severe luminal Crohn disease (defining moderate to severe disease as having a Crohn Disease Activity Index score of 220 or higher, or having a high risk of complications). This approach supports the early use of biologic agents, with or without immunomodulators, over a stepwise strategy. The patient’s response to this new regimen should be determined in the 12-week period after the initiation of therapy. Endoscopy or transmural responses to therapy should be assessed after 6 months.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

It is likely that the polypoid appearance of the colonic lining is a result of chronic inflammation of longstanding Crohn disease with an ileocolonic manifestation. Crohn disease is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by cycles of relapse and remission. These asymptomatic periods can last for several months up to a few years, as reported by the patient in this case. Up to 50% of cases of Crohn disease are characterized by ileocolitis, or inflammation of the ileum and the colon. Although postinflammatory polyps are a cancer risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease and pseudopolyps are associated with severe disease, their appearance is not necessarily a poor prognostic factor.

When assessing ongoing disease activity in ileocolonic Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis, colonoscopy represents the first-line approach. Endoscopic visualization and biopsy are critical components of the diagnosis. Alternatively, cross-sectional imaging can be used to assess disease phenotype. In addition, plain radiography or a CT scan of the abdomen can identify bowel obstruction and scanning of the pelvis can detect any intra-abdominal abscesses. Ulcerative colitis looms large in the differential diagnosis. Although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease, they are uncommon or rare in ulcerative colitis, although bleeding is observed much more frequently in ulcerative colitis.

Treatment of Crohn disease is based on the severity, location, and subtype (inflammatory, stricturing, or penetrating). There is also now a focus on determining which patients are at risk for a more severe disease course and may require earlier and more aggressive therapies. Crohn disease is primarily managed through the introduction of early immunosuppressive or combination therapy with biologic agents in high-risk patients, as well as complementary diet modification. Although most patients will ultimately undergo surgery, there is no curative approach, unlike in ulcerative colitis.

In its clinical care pathway, the American Gastroenterological Association supports a top-down approach to therapy for adult patients with moderate to severe luminal Crohn disease (defining moderate to severe disease as having a Crohn Disease Activity Index score of 220 or higher, or having a high risk of complications). This approach supports the early use of biologic agents, with or without immunomodulators, over a stepwise strategy. The patient’s response to this new regimen should be determined in the 12-week period after the initiation of therapy. Endoscopy or transmural responses to therapy should be assessed after 6 months.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 42-year-old woman presents with pain in her right abdomen, nausea, and diarrhea. She reports a weight loss of about 12 lb in the past several weeks because of a disinterest in food, which typically exacerbates her symptoms. She explains that she has been experiencing mounting stress at work and abdominal cramping and fatigue. Her family medical history is significant for pancreatic cancer and multiple sclerosis. She has not experienced any significant medical events in the past few years. Endoscopy shows polypoid appearance of the colonic lining.

Patient with severe lower abdominal pain

The differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in older patients is complicated by comorbid conditions such as infectious colitis, segmental colitis associated with diverticular disease, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced intestinal injury, and ischemia, each of which can mimic the intestinal inflammation characteristic of IBD.

Ulcerative colitis is one of the two major types of IBD, along with Crohn disease. Unlike Crohn disease, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis characteristically causes inflammation in the large bowel (see image).

Acute, severe ulcerative colitis (ie, > six bloody bowel movements per day, with one of the following: temperature > 38 °C [100.4 °F], hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/hr, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL) requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous high-dose corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/day or methylprednisolone 60 mg/day).

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathologic analysis. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon; and uniform inflammation without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to be characteristic of Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall in a patient with ulcerative colitis is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, the accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give the impression of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, but serologic markers can help in the differential diagnosis of IBD. Radiographic imaging has an important role in the workup of patients with suspected IBD and in the differentiation of ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease by demonstrating fistulae or the presence of small bowel disease seen only in Crohn disease.

Much work in the past decade has focused on the development of serologic markers for inflammatory bowel disease. pANCA and anti–Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) have been the most intensely studied. The World Gastroenterology Organization states that ulcerative colitis is more likely when the test results are positive for pANCA and negative for ASCA antigen; however, the pANCA test result may be positive in patients with Crohn disease, and this may complicate obtaining a diagnosis in an otherwise uncomplicated colitis.

According to the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis include tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin-12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). In general, most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in older patients is complicated by comorbid conditions such as infectious colitis, segmental colitis associated with diverticular disease, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced intestinal injury, and ischemia, each of which can mimic the intestinal inflammation characteristic of IBD.

Ulcerative colitis is one of the two major types of IBD, along with Crohn disease. Unlike Crohn disease, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis characteristically causes inflammation in the large bowel (see image).

Acute, severe ulcerative colitis (ie, > six bloody bowel movements per day, with one of the following: temperature > 38 °C [100.4 °F], hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/hr, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL) requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous high-dose corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/day or methylprednisolone 60 mg/day).

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathologic analysis. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon; and uniform inflammation without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to be characteristic of Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall in a patient with ulcerative colitis is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, the accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give the impression of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, but serologic markers can help in the differential diagnosis of IBD. Radiographic imaging has an important role in the workup of patients with suspected IBD and in the differentiation of ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease by demonstrating fistulae or the presence of small bowel disease seen only in Crohn disease.

Much work in the past decade has focused on the development of serologic markers for inflammatory bowel disease. pANCA and anti–Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) have been the most intensely studied. The World Gastroenterology Organization states that ulcerative colitis is more likely when the test results are positive for pANCA and negative for ASCA antigen; however, the pANCA test result may be positive in patients with Crohn disease, and this may complicate obtaining a diagnosis in an otherwise uncomplicated colitis.

According to the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis include tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin-12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). In general, most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in older patients is complicated by comorbid conditions such as infectious colitis, segmental colitis associated with diverticular disease, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced intestinal injury, and ischemia, each of which can mimic the intestinal inflammation characteristic of IBD.

Ulcerative colitis is one of the two major types of IBD, along with Crohn disease. Unlike Crohn disease, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis characteristically causes inflammation in the large bowel (see image).

Acute, severe ulcerative colitis (ie, > six bloody bowel movements per day, with one of the following: temperature > 38 °C [100.4 °F], hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/hr, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL) requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous high-dose corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/day or methylprednisolone 60 mg/day).

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathologic analysis. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon; and uniform inflammation without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to be characteristic of Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall in a patient with ulcerative colitis is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, the accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give the impression of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, but serologic markers can help in the differential diagnosis of IBD. Radiographic imaging has an important role in the workup of patients with suspected IBD and in the differentiation of ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease by demonstrating fistulae or the presence of small bowel disease seen only in Crohn disease.

Much work in the past decade has focused on the development of serologic markers for inflammatory bowel disease. pANCA and anti–Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) have been the most intensely studied. The World Gastroenterology Organization states that ulcerative colitis is more likely when the test results are positive for pANCA and negative for ASCA antigen; however, the pANCA test result may be positive in patients with Crohn disease, and this may complicate obtaining a diagnosis in an otherwise uncomplicated colitis.

According to the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis include tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin-12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). In general, most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 74-year-old woman presents with severe lower abdominal pain and dehydration. She also reports bloody diarrhea of 2 weeks' duration and an unintentional 10-lb weight loss. She reports six to seven bloody stools per day. Dietary alterations and loperamide have not helped. She has a temperature of 101.2 °F.

Physical examination reveals tenderness at the site of the left lower quadrant of her abdomen without rebound tenderness or guarding. Bowel sounds are active. She is found to have a purulent rectal discharge. Stool culture results for the most common pathogens are negative. She has hypoalbuminemia (2.5 g/dL), and her test result is positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA). Her serum carcinoembryonic antigen test result is negative. Her C-reactive protein level is 32 mg/dL.

She is admitted to the hospital and receives intravenous fluids. She undergoes a colonoscopy, which reveals inflammation and visible ulcers in the mucosa through the length of the large bowel.

Weakness in the legs and edema

Carcinomas like prostate cancer possess notable bony tropism and can metastasize to the lumbar‐sacral spine and pelvis, draining through the pelvic plexus of the lumbar region. Approximately 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer develop bone metastasis, the spine being the most common site. Manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer include weight loss and loss of appetite; bone pain, with or without pathologic fracture; and lower-extremity pain and edema. Urinary symptoms are also common. Other physical examination findings are adenopathy, bony tenderness, and lower-extremity edema, as seen in the present case.

Radiologic findings of bone metastases can mimic Paget disease, and even though bone metastases are blastic, lytic lesions may develop and cause pathologic fractures. Such fractures must be distinguished from osteoporotic fractures that can occur after prolonged luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone therapy. Also included in the differential of the present case are lymphomas, which can manifest as pelvic masses and bone lesions and have been reported with prostate cancer. However, considering the patient's history, physical examination, and lab results, bone metastasis is the most likely diagnosis.

Bone imaging should be performed for any patient with suspected bone metastases; specifically, multiparametric MRI outperforms bone scan and targeted x-rays for detection of bone metastases. Because activity in the bone scan may not be observed until 5 years after micrometastasis has occurred, negative bone scan results cannot be used to definitively exclude metastasis.

The alpha emitter radium-223 is a category 1 option to treat symptomatic bone metastases (but should not be used in patients with visceral metastases). It is not recommended for use in combination with docetaxel or any other systemic therapy but may be used with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), as studies have suggested that the addition of ADT improves progression-free survival in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer with metastasis. Concomitant use of denosumab or zoledronic acid is also recommended.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Carcinomas like prostate cancer possess notable bony tropism and can metastasize to the lumbar‐sacral spine and pelvis, draining through the pelvic plexus of the lumbar region. Approximately 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer develop bone metastasis, the spine being the most common site. Manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer include weight loss and loss of appetite; bone pain, with or without pathologic fracture; and lower-extremity pain and edema. Urinary symptoms are also common. Other physical examination findings are adenopathy, bony tenderness, and lower-extremity edema, as seen in the present case.

Radiologic findings of bone metastases can mimic Paget disease, and even though bone metastases are blastic, lytic lesions may develop and cause pathologic fractures. Such fractures must be distinguished from osteoporotic fractures that can occur after prolonged luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone therapy. Also included in the differential of the present case are lymphomas, which can manifest as pelvic masses and bone lesions and have been reported with prostate cancer. However, considering the patient's history, physical examination, and lab results, bone metastasis is the most likely diagnosis.

Bone imaging should be performed for any patient with suspected bone metastases; specifically, multiparametric MRI outperforms bone scan and targeted x-rays for detection of bone metastases. Because activity in the bone scan may not be observed until 5 years after micrometastasis has occurred, negative bone scan results cannot be used to definitively exclude metastasis.

The alpha emitter radium-223 is a category 1 option to treat symptomatic bone metastases (but should not be used in patients with visceral metastases). It is not recommended for use in combination with docetaxel or any other systemic therapy but may be used with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), as studies have suggested that the addition of ADT improves progression-free survival in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer with metastasis. Concomitant use of denosumab or zoledronic acid is also recommended.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Carcinomas like prostate cancer possess notable bony tropism and can metastasize to the lumbar‐sacral spine and pelvis, draining through the pelvic plexus of the lumbar region. Approximately 90% of patients with advanced prostate cancer develop bone metastasis, the spine being the most common site. Manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer include weight loss and loss of appetite; bone pain, with or without pathologic fracture; and lower-extremity pain and edema. Urinary symptoms are also common. Other physical examination findings are adenopathy, bony tenderness, and lower-extremity edema, as seen in the present case.

Radiologic findings of bone metastases can mimic Paget disease, and even though bone metastases are blastic, lytic lesions may develop and cause pathologic fractures. Such fractures must be distinguished from osteoporotic fractures that can occur after prolonged luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone therapy. Also included in the differential of the present case are lymphomas, which can manifest as pelvic masses and bone lesions and have been reported with prostate cancer. However, considering the patient's history, physical examination, and lab results, bone metastasis is the most likely diagnosis.

Bone imaging should be performed for any patient with suspected bone metastases; specifically, multiparametric MRI outperforms bone scan and targeted x-rays for detection of bone metastases. Because activity in the bone scan may not be observed until 5 years after micrometastasis has occurred, negative bone scan results cannot be used to definitively exclude metastasis.

The alpha emitter radium-223 is a category 1 option to treat symptomatic bone metastases (but should not be used in patients with visceral metastases). It is not recommended for use in combination with docetaxel or any other systemic therapy but may be used with androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), as studies have suggested that the addition of ADT improves progression-free survival in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer with metastasis. Concomitant use of denosumab or zoledronic acid is also recommended.

Kyle A. Richards, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Urology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Chief of Urology, William S. Middleton Memorial VA Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin

Kyle A. Richards, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 66-year-old male patient presents with weakness in the legs and edema. He takes medication to control his hypertension. About 8 years ago, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer during screening. Tumor staging was T3 and Gleason score was 8. The patient underwent successful radiation combined with hormone therapy. While he does not have urologic symptoms at this time, he does report that he is easily fatigued. Serum calcium is 10.6 mg/dL and hemoglobin is 10.5 g/dL. There is no evidence of neurologic deficit.

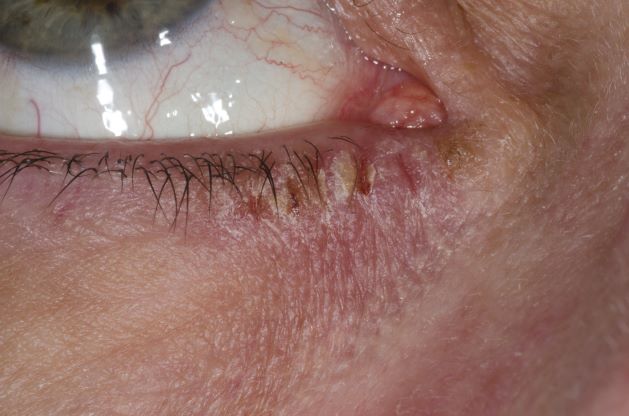

Woman with burning, itchy red eyes

This patient has the “atopic triad” of allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis around the eyes and on the eyelids often develops in teenage years and adulthood but may also occur in older persons. Occasionally, it can be the only manifestation of atopic dermatitis. The upper eyelids may appear scaly and fissured. The so-called "allergic shiners" (symmetric, dark circles beneath the lower eyelid) and Dennie-Morgan lines (extra skin folds under the lower eyelid) are often present.

The thin skin of the eyelids is particularly sensitive to irritants and allergens and is thus prone to develop dermatitis. Contact with the same trigger may not lead to a rash on other areas of skin. Upper, lower or both eyelids on one or both sides can be affected. The patient may report itching, stinging or burning, and the lids are red and scaly. They may swell. With persistence of the dermatitis, the eyelids become thickened with increased skin markings (lichenification). The eyelid margins may become involved (blepharitis). The appearance is similar, whatever the cause.

The basis of treatment for atopic dermatitis is to provide moisturization for dryness, allay pruritus, and manage inflammation of the eczematous lesions. Conservative initial management of eyelid dermatitis also includes gentle skin care and avoidance of fragrance and other known irritants in personal care, hair, and facial skin care products. Bland, fragrance-free emollients, such as petrolatum, may be applied directly to the eyelids.

Topical corticosteroids are one therapeutic option for eyelid dermatitis. However, only low-potency topical corticosteroids are safe, and only for short-term use, on the eyelids. Typically, they are used twice daily for 2-4 weeks. However, even with low-potency topical corticosteroids, the eyelids remain vulnerable to thinning, even atrophy. Because of these issues, topical calcineurin inhibitors are often the preferred treatment.

Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of comorbid eye diseases, including keratitis, conjunctivitis, and keratoconus. A careful clinical examination for associated erythema, crusting, and blepharitis many prompt a referral to an ophthalmologist.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This patient has the “atopic triad” of allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis around the eyes and on the eyelids often develops in teenage years and adulthood but may also occur in older persons. Occasionally, it can be the only manifestation of atopic dermatitis. The upper eyelids may appear scaly and fissured. The so-called "allergic shiners" (symmetric, dark circles beneath the lower eyelid) and Dennie-Morgan lines (extra skin folds under the lower eyelid) are often present.

The thin skin of the eyelids is particularly sensitive to irritants and allergens and is thus prone to develop dermatitis. Contact with the same trigger may not lead to a rash on other areas of skin. Upper, lower or both eyelids on one or both sides can be affected. The patient may report itching, stinging or burning, and the lids are red and scaly. They may swell. With persistence of the dermatitis, the eyelids become thickened with increased skin markings (lichenification). The eyelid margins may become involved (blepharitis). The appearance is similar, whatever the cause.

The basis of treatment for atopic dermatitis is to provide moisturization for dryness, allay pruritus, and manage inflammation of the eczematous lesions. Conservative initial management of eyelid dermatitis also includes gentle skin care and avoidance of fragrance and other known irritants in personal care, hair, and facial skin care products. Bland, fragrance-free emollients, such as petrolatum, may be applied directly to the eyelids.

Topical corticosteroids are one therapeutic option for eyelid dermatitis. However, only low-potency topical corticosteroids are safe, and only for short-term use, on the eyelids. Typically, they are used twice daily for 2-4 weeks. However, even with low-potency topical corticosteroids, the eyelids remain vulnerable to thinning, even atrophy. Because of these issues, topical calcineurin inhibitors are often the preferred treatment.

Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of comorbid eye diseases, including keratitis, conjunctivitis, and keratoconus. A careful clinical examination for associated erythema, crusting, and blepharitis many prompt a referral to an ophthalmologist.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This patient has the “atopic triad” of allergies, asthma, and atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis around the eyes and on the eyelids often develops in teenage years and adulthood but may also occur in older persons. Occasionally, it can be the only manifestation of atopic dermatitis. The upper eyelids may appear scaly and fissured. The so-called "allergic shiners" (symmetric, dark circles beneath the lower eyelid) and Dennie-Morgan lines (extra skin folds under the lower eyelid) are often present.

The thin skin of the eyelids is particularly sensitive to irritants and allergens and is thus prone to develop dermatitis. Contact with the same trigger may not lead to a rash on other areas of skin. Upper, lower or both eyelids on one or both sides can be affected. The patient may report itching, stinging or burning, and the lids are red and scaly. They may swell. With persistence of the dermatitis, the eyelids become thickened with increased skin markings (lichenification). The eyelid margins may become involved (blepharitis). The appearance is similar, whatever the cause.

The basis of treatment for atopic dermatitis is to provide moisturization for dryness, allay pruritus, and manage inflammation of the eczematous lesions. Conservative initial management of eyelid dermatitis also includes gentle skin care and avoidance of fragrance and other known irritants in personal care, hair, and facial skin care products. Bland, fragrance-free emollients, such as petrolatum, may be applied directly to the eyelids.

Topical corticosteroids are one therapeutic option for eyelid dermatitis. However, only low-potency topical corticosteroids are safe, and only for short-term use, on the eyelids. Typically, they are used twice daily for 2-4 weeks. However, even with low-potency topical corticosteroids, the eyelids remain vulnerable to thinning, even atrophy. Because of these issues, topical calcineurin inhibitors are often the preferred treatment.

Patients with atopic dermatitis have an increased risk of comorbid eye diseases, including keratitis, conjunctivitis, and keratoconus. A careful clinical examination for associated erythema, crusting, and blepharitis many prompt a referral to an ophthalmologist.

Brian S. Kim, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Dermatology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Brian S. Kim, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 21-year-old woman presents with burning, itchy red eyes that she rubs incessantly. On examination, she has an erythematic, scaly, pruritic rash on the upper and lower eyelids and below her eyes. She has no other outbreaks on the rest of her skin except for mild acne. A moisturizer has provided minimal relief for the itching but has not helped with the rash. She has a history of asthma, for which she uses an inhaler, and of hay fever, for which she takes an antihistamine. She also reports that she has had two episodes of conjunctivitis within the past year, which were treated with antibiotic eye drops.

Do you use intrapartum warm compresses to the perineum or perineal massage in your practice?

[polldaddy:10937454]

[polldaddy:10937454]

[polldaddy:10937454]