User login

Widower Experiencing Fatigue

ANSWER

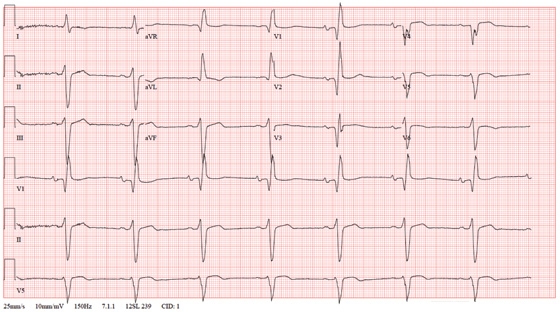

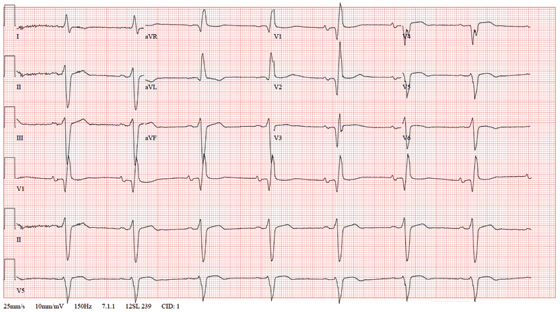

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes marked sinus bradycardia, left atrial enlargement, right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block, left ventricular hypertrophy, and an old anteroseptal myocardial infarction.

Marked sinus bradycardia is represented by a heart rate of 46 beats/min. Left atrial enlargement is evident from P waves ≥ 110 ms in lead I (difficult to see in this ECG) and a terminally negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2 (easier to see in this ECG).

Findings of a right bundle branch block include a QRS complex > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. (In this ECG, the RSR’ complex is not obvious.)

A left anterior fascicular block is indicated by S waves > R waves in leads II, III, and aVF with marked left-axis deviation (R axis, –77°). Left ventricular hypertrophy is evident if the sum of the R wave in lead I and the S wave in III ≥ 25 mm or if the sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is ≥ 35 mm.

Finally, the diagnosis of an old anteroseptal myocardial infarction is evidenced by Q waves in leads V1 through V3 and a QS pattern in lead V4.

The patient’s bradycardia was responsible for his symptoms of fatigue. Careful questioning revealed that he had inadvertently doubled his dose of atenolol for the preceding two weeks. Upon correction of his dose, his heart rate increased and his symptoms resolved.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes marked sinus bradycardia, left atrial enlargement, right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block, left ventricular hypertrophy, and an old anteroseptal myocardial infarction.

Marked sinus bradycardia is represented by a heart rate of 46 beats/min. Left atrial enlargement is evident from P waves ≥ 110 ms in lead I (difficult to see in this ECG) and a terminally negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2 (easier to see in this ECG).

Findings of a right bundle branch block include a QRS complex > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. (In this ECG, the RSR’ complex is not obvious.)

A left anterior fascicular block is indicated by S waves > R waves in leads II, III, and aVF with marked left-axis deviation (R axis, –77°). Left ventricular hypertrophy is evident if the sum of the R wave in lead I and the S wave in III ≥ 25 mm or if the sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is ≥ 35 mm.

Finally, the diagnosis of an old anteroseptal myocardial infarction is evidenced by Q waves in leads V1 through V3 and a QS pattern in lead V4.

The patient’s bradycardia was responsible for his symptoms of fatigue. Careful questioning revealed that he had inadvertently doubled his dose of atenolol for the preceding two weeks. Upon correction of his dose, his heart rate increased and his symptoms resolved.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes marked sinus bradycardia, left atrial enlargement, right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block, left ventricular hypertrophy, and an old anteroseptal myocardial infarction.

Marked sinus bradycardia is represented by a heart rate of 46 beats/min. Left atrial enlargement is evident from P waves ≥ 110 ms in lead I (difficult to see in this ECG) and a terminally negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2 (easier to see in this ECG).

Findings of a right bundle branch block include a QRS complex > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. (In this ECG, the RSR’ complex is not obvious.)

A left anterior fascicular block is indicated by S waves > R waves in leads II, III, and aVF with marked left-axis deviation (R axis, –77°). Left ventricular hypertrophy is evident if the sum of the R wave in lead I and the S wave in III ≥ 25 mm or if the sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is ≥ 35 mm.

Finally, the diagnosis of an old anteroseptal myocardial infarction is evidenced by Q waves in leads V1 through V3 and a QS pattern in lead V4.

The patient’s bradycardia was responsible for his symptoms of fatigue. Careful questioning revealed that he had inadvertently doubled his dose of atenolol for the preceding two weeks. Upon correction of his dose, his heart rate increased and his symptoms resolved.

A 72-year-old man presents for a routine appointment. He was doing well until two months ago, when he started to notice that he fatigues easily. He is unable to go up and down stairs at home without pausing and has difficulty working in his garden. He says he does not become short of breath but just feels fatigued. The patient denies chest pain, palpitations, tachycardia, syncope, or near-syncope. He denies recent weight gain or peripheral extremity edema. He has had no recent changes to his medications, and he has not recently been ill. The man’s cardiac history is remarkable for coronary artery disease, a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) in 2007, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, and an ischemic cardiomyopathy. His most recent echocardiogram (six months ago) showed global left ventricular dysfunction with inferior akinesis, a left ventricular end-diastolic dimension of 8.1 cm, and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35%. His pulmonary artery pressure was 25 to 29 mm Hg. A nuclear viability study performed at the same time showed a nonviable myocardial infarction involving the anterior and inferior septal walls of the left ventricle. A cardiac catheterization performed one year ago showed 30% stenosis of the left main coronary artery, an occluded left anterior descending (LAD) artery with myocardial perfusion supplied by right-to-left collateral vessels, 50% stenosis of the left circumflex artery, 70% stenosis of the left circumflex artery, and 70% to 80% stenosis of the mid right coronary artery (RCA). The saphenous vein grafts to the LAD, RCA, circumflex, and diagonal branches were occluded. Medical history is remarkable for dyslipidemia, arthritis, and depression. In addition to CABG, surgical history includes cholecystectomy and a left hip replacement. The patient is a retired beer distributor who has lived alone since his wife’s death three years ago. He drinks two or three glasses of wine in the evenings. Prior to quitting 10 years ago, he had a 30-pack-year history of smoking; however, he started again after his wife’s death and currently smokes half a pack of cigarettes per day. His medication list includes aspirin, atenolol, hydrochlorothiazide, lisinopril, atorvastatin, and trazodone. The review of systems is negative. Vital statistics include a blood pressure of 106/58 mm Hg; pulse, 50 beats/min; temperature, 97.5°F; and O2 saturation, 94% on room air. His weight is 172.4 lb and is unchanged from his last clinic visit. Pertinent findings on the physical exam include clear lung fields, a regular rhythm, and bradycardia with no murmurs or extra heart sounds, no bruits, no jugular venous distention, and no peripheral edema. All pulses are equal and normal. Based on the patient’s symptoms and the finding of bradycardia on physical exam, you order an ECG, which shows the following: a ventricular rate of 46 beats/min; PR interval, 202 ms; QRS duration, 200 ms; QT/QTc interval, 578/505 ms; P axis, 71°; R axis, –77°; and T axis, 109°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Man Continually Cuts Facial Lesion While Shaving

ANSWER

The best answer is to send the slides to a dermatopathologist (choice “a”), for reasons that will become clear in the discussion. It is true that by re-excising with margins (choice “b”), the lesion would certainly be gone, but that does nothing to address the potential pathologic implications of some of the items in the differential diagnosis for this type of lesion.

The same could be said for rechecking the lesion periodically (choice “c”), which would otherwise be an intelligent option. It is almost never wrong to consult with a supervising/collaborating physician (choice “d”), but that does not relieve the PA/NP of the ultimate responsibility for resolving the dilemma.

DISCUSSION

Odd little papules in the nasolabial fold can have implications far beyond the usual “benign versus malignant” issue. With its surface devoid of adnexal structures, and firm feel, this lesion was a bit suspicious, history of stability notwithstanding.

Generally termed skin adnexal tumors (SATs), these lesions are derived from local adnexal structures, such as eccrine or apocrine sweat glands or pilosebaceous unit tissue. But they may originate from pluripotent stem cells located in the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, residing in an area called “the bulge.”

Their final designation is based on the predominant cell type seen on pathology, but differentiation can be difficult, even for experienced pathologists. Many benign types have been described, but for every benign category, a malignant counterpart exists. The latter tend to be aggressive and involve nodes, metastasis, and generally poor outcomes.

Heredity, skin type, and UV exposure play significant roles in some types of skin cancer, but an intracellular signaling pathway is also thought to determine the ultimate differentiation of these cells. Loss of inhibition of this pathway, which normally occurs, is apparently the main deciding factor in malignant transformation.

But the importance of a precise diagnosis for an SAT is more than mere benign versus malignant considerations. These lesions can serve as markers for syndromes associated with internal malignancies, such as Cowden’s disease (trichilemmomas) or Muir-Torre syndrome (sebaceous neoplasm), to name just two.

The person most likely to be able to discriminate between these various possibilities is the dermatopathologist, who is not only an expert in what is seen microscopically, but is also typically a practicing dermatologist who regularly sees the conditions he diagnoses. The biopsying provider has an obligation to insist on a crystal-clear diagnosis, when it can be obtained. And that “diagnosis” isn’t always about what the lesion is. Sometimes it’s as much about what the lesion means.

SUGGESTED READING

Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129-144.

ANSWER

The best answer is to send the slides to a dermatopathologist (choice “a”), for reasons that will become clear in the discussion. It is true that by re-excising with margins (choice “b”), the lesion would certainly be gone, but that does nothing to address the potential pathologic implications of some of the items in the differential diagnosis for this type of lesion.

The same could be said for rechecking the lesion periodically (choice “c”), which would otherwise be an intelligent option. It is almost never wrong to consult with a supervising/collaborating physician (choice “d”), but that does not relieve the PA/NP of the ultimate responsibility for resolving the dilemma.

DISCUSSION

Odd little papules in the nasolabial fold can have implications far beyond the usual “benign versus malignant” issue. With its surface devoid of adnexal structures, and firm feel, this lesion was a bit suspicious, history of stability notwithstanding.

Generally termed skin adnexal tumors (SATs), these lesions are derived from local adnexal structures, such as eccrine or apocrine sweat glands or pilosebaceous unit tissue. But they may originate from pluripotent stem cells located in the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, residing in an area called “the bulge.”

Their final designation is based on the predominant cell type seen on pathology, but differentiation can be difficult, even for experienced pathologists. Many benign types have been described, but for every benign category, a malignant counterpart exists. The latter tend to be aggressive and involve nodes, metastasis, and generally poor outcomes.

Heredity, skin type, and UV exposure play significant roles in some types of skin cancer, but an intracellular signaling pathway is also thought to determine the ultimate differentiation of these cells. Loss of inhibition of this pathway, which normally occurs, is apparently the main deciding factor in malignant transformation.

But the importance of a precise diagnosis for an SAT is more than mere benign versus malignant considerations. These lesions can serve as markers for syndromes associated with internal malignancies, such as Cowden’s disease (trichilemmomas) or Muir-Torre syndrome (sebaceous neoplasm), to name just two.

The person most likely to be able to discriminate between these various possibilities is the dermatopathologist, who is not only an expert in what is seen microscopically, but is also typically a practicing dermatologist who regularly sees the conditions he diagnoses. The biopsying provider has an obligation to insist on a crystal-clear diagnosis, when it can be obtained. And that “diagnosis” isn’t always about what the lesion is. Sometimes it’s as much about what the lesion means.

SUGGESTED READING

Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129-144.

ANSWER

The best answer is to send the slides to a dermatopathologist (choice “a”), for reasons that will become clear in the discussion. It is true that by re-excising with margins (choice “b”), the lesion would certainly be gone, but that does nothing to address the potential pathologic implications of some of the items in the differential diagnosis for this type of lesion.

The same could be said for rechecking the lesion periodically (choice “c”), which would otherwise be an intelligent option. It is almost never wrong to consult with a supervising/collaborating physician (choice “d”), but that does not relieve the PA/NP of the ultimate responsibility for resolving the dilemma.

DISCUSSION

Odd little papules in the nasolabial fold can have implications far beyond the usual “benign versus malignant” issue. With its surface devoid of adnexal structures, and firm feel, this lesion was a bit suspicious, history of stability notwithstanding.

Generally termed skin adnexal tumors (SATs), these lesions are derived from local adnexal structures, such as eccrine or apocrine sweat glands or pilosebaceous unit tissue. But they may originate from pluripotent stem cells located in the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, residing in an area called “the bulge.”

Their final designation is based on the predominant cell type seen on pathology, but differentiation can be difficult, even for experienced pathologists. Many benign types have been described, but for every benign category, a malignant counterpart exists. The latter tend to be aggressive and involve nodes, metastasis, and generally poor outcomes.

Heredity, skin type, and UV exposure play significant roles in some types of skin cancer, but an intracellular signaling pathway is also thought to determine the ultimate differentiation of these cells. Loss of inhibition of this pathway, which normally occurs, is apparently the main deciding factor in malignant transformation.

But the importance of a precise diagnosis for an SAT is more than mere benign versus malignant considerations. These lesions can serve as markers for syndromes associated with internal malignancies, such as Cowden’s disease (trichilemmomas) or Muir-Torre syndrome (sebaceous neoplasm), to name just two.

The person most likely to be able to discriminate between these various possibilities is the dermatopathologist, who is not only an expert in what is seen microscopically, but is also typically a practicing dermatologist who regularly sees the conditions he diagnoses. The biopsying provider has an obligation to insist on a crystal-clear diagnosis, when it can be obtained. And that “diagnosis” isn’t always about what the lesion is. Sometimes it’s as much about what the lesion means.

SUGGESTED READING

Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(2):129-144.

A 53-year-old man self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his left maxilla that has been basically unchanged for several years. He is concerned for two reasons: First, it is a rare day on which he fails to cut the lesion while shaving, and he is afraid this repeated trauma will “turn it into skin cancer.” Second, a co-worker who recently had a basal cell carcinoma diagnosed in the same location constantly asks the patient when he is “going to see someone about that lesion.” Additional history taking reveals that the patient has had little sun exposure in his life. He is otherwise healthy. Examination of the lesion shows a nevoid pink 6-mm intradermal nodule in the lower left nasolabial/upper maxillary area. Closer inspection reveals that the surface of the lesion is totally smooth and devoid of adnexae (pores, hairs). On palpation, the lesion is notably firmer than expected. The lesion has a slightly translucent appearance, almost as if light could pass through it. In light of the recurring trauma caused by shaving, and at his co-worker’s urging, the patient decides to have the lesion excised. The lesion is sent for pathologic examination, in this case by a general dermatologist from a laboratory of his insurance provider’s choosing. Calling the lesion a desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, the general pathologist nonetheless expressed his uncertainty, advising “clinical correlation.”

Dehydration Leads to Incidental Finding

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates that the nasogastric tube is within a decompressed stomach. Normal gas pattern is noted within the bowel and colon.

Of note, however, are tiny calcifications within the right upper quadrant. This finding is suggestive of cholelithiasis—in this case, likely an incidental finding.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates that the nasogastric tube is within a decompressed stomach. Normal gas pattern is noted within the bowel and colon.

Of note, however, are tiny calcifications within the right upper quadrant. This finding is suggestive of cholelithiasis—in this case, likely an incidental finding.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates that the nasogastric tube is within a decompressed stomach. Normal gas pattern is noted within the bowel and colon.

Of note, however, are tiny calcifications within the right upper quadrant. This finding is suggestive of cholelithiasis—in this case, likely an incidental finding.

A 57-year-old man is admitted to your facility for weakness and dehydration. His medical history is significant for rectal carcinoma, diabetes, and hypertension. His family states that his oral intake has been progressively less in the past several weeks. The patient’s vital signs are stable. Overall examination demonstrates a weak, frail-appearing man with dry mucous membranes and no other acute abnormalities. Lab work reveals that his serum sodium level and BUN/creatinine ratio are slightly elevated. To facilitate hydration, administration of medications, and nourishment, placement of a nasogastric tube is ordered; this is done just prior to your arrival at the patient’s room during rounds. As per protocol, an abdominal radiograph is obtained, and the nurses ask you to check it to confirm placement. The radiograph is shown. What is your impression?

Man Found Unconscious In a Park

ANSWER

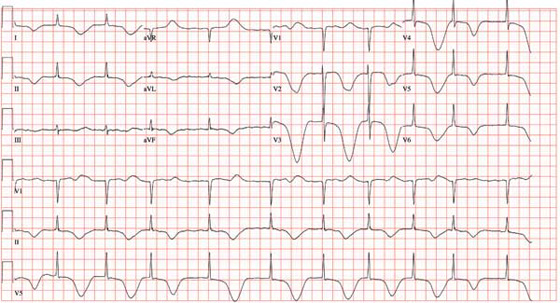

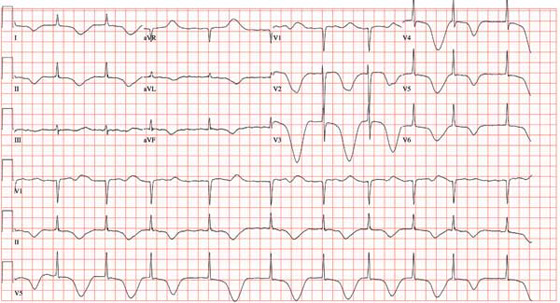

The ECG shows atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular response, a significantly prolonged QTc interval, and deep ST-T wave changes. The patient has chronic atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular response, so this arrhythmia is not unusual.

The deep ST-T wave changes and a prolonged QTc interval not seen on the previous ECG are consistent with a central nervous system injury. Cerebral disorders affect ventricular repolarization, as evidenced by depressed ST segments, flat or inverted T waves, and prolongation of the QTc interval. It is important to note that ST-segment elevations and deep T-wave changes do not always signify myocardial ischemia or injury.

This patient’s CT and MRI scans of the head showed no evidence of an intracranial bleed or cerebrovascular accident. A subsequent EEG showed epileptiform discharges, but no seizure activity.

The most likely cause of the ST-T wave changes is global intracranial hypoperfusion as a result of ventricular fibrillation with a prolonged resuscitation period. Over the course of the following two weeks, the ST-T wave changes and QTc prolongation normalized.

ANSWER

The ECG shows atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular response, a significantly prolonged QTc interval, and deep ST-T wave changes. The patient has chronic atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular response, so this arrhythmia is not unusual.

The deep ST-T wave changes and a prolonged QTc interval not seen on the previous ECG are consistent with a central nervous system injury. Cerebral disorders affect ventricular repolarization, as evidenced by depressed ST segments, flat or inverted T waves, and prolongation of the QTc interval. It is important to note that ST-segment elevations and deep T-wave changes do not always signify myocardial ischemia or injury.

This patient’s CT and MRI scans of the head showed no evidence of an intracranial bleed or cerebrovascular accident. A subsequent EEG showed epileptiform discharges, but no seizure activity.

The most likely cause of the ST-T wave changes is global intracranial hypoperfusion as a result of ventricular fibrillation with a prolonged resuscitation period. Over the course of the following two weeks, the ST-T wave changes and QTc prolongation normalized.

ANSWER

The ECG shows atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular response, a significantly prolonged QTc interval, and deep ST-T wave changes. The patient has chronic atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular response, so this arrhythmia is not unusual.

The deep ST-T wave changes and a prolonged QTc interval not seen on the previous ECG are consistent with a central nervous system injury. Cerebral disorders affect ventricular repolarization, as evidenced by depressed ST segments, flat or inverted T waves, and prolongation of the QTc interval. It is important to note that ST-segment elevations and deep T-wave changes do not always signify myocardial ischemia or injury.

This patient’s CT and MRI scans of the head showed no evidence of an intracranial bleed or cerebrovascular accident. A subsequent EEG showed epileptiform discharges, but no seizure activity.

The most likely cause of the ST-T wave changes is global intracranial hypoperfusion as a result of ventricular fibrillation with a prolonged resuscitation period. Over the course of the following two weeks, the ST-T wave changes and QTc prolongation normalized.

A 69-year-old man is found unconscious in a public park by a couple out for a walk. The husband tries to arouse the man to no avail; checking for a pulse and finding none, he asks his wife to call 911 while he begins CPR. His wife joins him after making the call, and they continue CPR for approximately 11 minutes, until paramedics arrive. An automatic external defibrillator is placed on the patient, who is found to be in ventricular fibrillation. The patient is intubated, and epinephrine and lidocaine are administered along with three shocks; the third restores the rhythm to normal sinus. The total resuscitation time is about 17 minutes. The patient is placed on a lidocaine drip and transported to the emergency department. On arrival, the man is unconscious but responsive to deep pain stimuli. An initial ECG shows atrial fibrillation with a controlled ventricular response. His serum troponin measures 2.7 µg/L and peaks at 3.1 µg/L. The medical record shows a history of coronary artery disease with coronary artery revascularization (left internal mammary artery–left anterior descending artery, saphenous vein graft–second diagonal artery) four years ago. The man also has a history of chronic atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, peptic ulcer disease, and a pulmonary embolus. The record also indicates that he smokes 1-1/2 packs of cigarettes per day, and drinks shots of tequila on weekends. Family history is remarkable for hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, and breast cancer. He is allergic to aspirin (peptic ulcers), enalapril (cough), and penicillin. His most recent medication list includes atenolol, amlodipine, diltiazem, simvastatin, omeprazole, and warfarin. Because the patient is unconscious, a review of systems cannot be obtained. You assume care of the patient in the ICU. The nurse states that the patient’s vital signs were stable overnight, and there were no new arrhythmias. An abbreviated physical exam reveals no changes to his condition. The patient remains cool, sedated, and intubated. As you finish rounds, his nurse expresses concern that the patient has ongoing ischemia and asks you to review an ECG that was just obtained. The ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 62 beats/min; PR interval, indeterminate; QRS duration, 88 ms; QT/QTc interval, 718/728 ms; R axis, 35°; and T axis, 209°. What is your interpretation of this ECG, and what is the explanation for the dramatic changes overnight?

How Should This Young Girl Be Diagnosed?

ANSWER

The correct answer is test treatment with liquid nitrogen (choice “c”), which would elicit the pathognomic umbilication seen in most molluscum papules. Cultures for bacteria or viruses (choice “a” or “b”) would not help, since this is not a bacterial condition and since the poxvirus is difficult to grow in culture. Punch or shave biopsy (choice “d”) would establish the diagnosis and is occasionally necessary, but it is not called for in this case.

DISCUSSION

This combination of molluscum papules, which occasionally become inflamed and pustular, and underlying eczematous changes is quite common. It has been called “eczematized molluscum.”

The antecubital distribution and personal and family history of atopy should put the provider on notice immediately. The diagnosis usually can be made on empiric grounds, without the diagnostic liquid nitrogen or biopsy. But when in doubt, confirmation is quick and easy.

The majority of molluscum patients will be atopic or will have parents or siblings who are. Patients with atopy are notoriously susceptible to skin infections, especially from viral organisms.

Most children with molluscum will acquire immunity within a few months, with or without treatment. But it is arguably sensible to treat a few lesions with topical preparations such as cantharidin, a blistering agent that destroys the treated lesions and may prompt the immune system to destroy the rest.

As with molluscum’s cousin, the wart, many different treatments for removing the papules have been tried, including destructive modalities such as liquid nitrogen. All have drawbacks, such as pain and blistering.

With this combination of atopy and warts or molluscum, a healthy dose of patient (or, more importantly, parent!) education is essential before treatment is attempted, since parents of these patients are often confused and worried. Parents and providers are often frightened by the occasional red, pustular molluscum. However, only rarely does this represent secondary bacterial infection.

ANSWER

The correct answer is test treatment with liquid nitrogen (choice “c”), which would elicit the pathognomic umbilication seen in most molluscum papules. Cultures for bacteria or viruses (choice “a” or “b”) would not help, since this is not a bacterial condition and since the poxvirus is difficult to grow in culture. Punch or shave biopsy (choice “d”) would establish the diagnosis and is occasionally necessary, but it is not called for in this case.

DISCUSSION

This combination of molluscum papules, which occasionally become inflamed and pustular, and underlying eczematous changes is quite common. It has been called “eczematized molluscum.”

The antecubital distribution and personal and family history of atopy should put the provider on notice immediately. The diagnosis usually can be made on empiric grounds, without the diagnostic liquid nitrogen or biopsy. But when in doubt, confirmation is quick and easy.

The majority of molluscum patients will be atopic or will have parents or siblings who are. Patients with atopy are notoriously susceptible to skin infections, especially from viral organisms.

Most children with molluscum will acquire immunity within a few months, with or without treatment. But it is arguably sensible to treat a few lesions with topical preparations such as cantharidin, a blistering agent that destroys the treated lesions and may prompt the immune system to destroy the rest.

As with molluscum’s cousin, the wart, many different treatments for removing the papules have been tried, including destructive modalities such as liquid nitrogen. All have drawbacks, such as pain and blistering.

With this combination of atopy and warts or molluscum, a healthy dose of patient (or, more importantly, parent!) education is essential before treatment is attempted, since parents of these patients are often confused and worried. Parents and providers are often frightened by the occasional red, pustular molluscum. However, only rarely does this represent secondary bacterial infection.

ANSWER

The correct answer is test treatment with liquid nitrogen (choice “c”), which would elicit the pathognomic umbilication seen in most molluscum papules. Cultures for bacteria or viruses (choice “a” or “b”) would not help, since this is not a bacterial condition and since the poxvirus is difficult to grow in culture. Punch or shave biopsy (choice “d”) would establish the diagnosis and is occasionally necessary, but it is not called for in this case.

DISCUSSION

This combination of molluscum papules, which occasionally become inflamed and pustular, and underlying eczematous changes is quite common. It has been called “eczematized molluscum.”

The antecubital distribution and personal and family history of atopy should put the provider on notice immediately. The diagnosis usually can be made on empiric grounds, without the diagnostic liquid nitrogen or biopsy. But when in doubt, confirmation is quick and easy.

The majority of molluscum patients will be atopic or will have parents or siblings who are. Patients with atopy are notoriously susceptible to skin infections, especially from viral organisms.

Most children with molluscum will acquire immunity within a few months, with or without treatment. But it is arguably sensible to treat a few lesions with topical preparations such as cantharidin, a blistering agent that destroys the treated lesions and may prompt the immune system to destroy the rest.

As with molluscum’s cousin, the wart, many different treatments for removing the papules have been tried, including destructive modalities such as liquid nitrogen. All have drawbacks, such as pain and blistering.

With this combination of atopy and warts or molluscum, a healthy dose of patient (or, more importantly, parent!) education is essential before treatment is attempted, since parents of these patients are often confused and worried. Parents and providers are often frightened by the occasional red, pustular molluscum. However, only rarely does this represent secondary bacterial infection.

A 6-year-old girl has been seen by at least three providers, each of whom offered a different diagnosis for the dermatologic changes to her arm (staph infection, warts, and dermatitis). None of the prescribed treatments for these conditions—a 10-day course of cephalexin; salicylic acid; and hydrocortisone cream, respectively—have resolved the problem. Therefore, her mother brings the child to dermatology. Further questioning reveals a marked history of atopy, characterized by seasonal allergies, occasional hives, and asthma. Both parents experienced these same problems as children. Examination reveals a 5-cm ill-defined collection of firm 2- to 4-mm papules covering the bilateral antecubital areas. These are superimposed on a background of slightly erythematous, slightly scaly skin. A total of three angry-looking pustules are interspersed among the smaller shiny, firm papules.

Post PICC Placement

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a right PICC line terminating at the superior vena cava. There is no evidence of pneumothorax.

Of note, however, is a large oval density within the right upper lobe, measuring 4.5 x 7 cm. This lesion could represent a loculated mass such as an abscess or hematoma. Further workup with additional imaging is warranted.

The working theory on this patient was that the density likely represented abscess or infection. Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest suggested likely abscess. The patient then underwent successful CT-guided needle biopsy, which returned positive results for Cryptococcus.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a right PICC line terminating at the superior vena cava. There is no evidence of pneumothorax.

Of note, however, is a large oval density within the right upper lobe, measuring 4.5 x 7 cm. This lesion could represent a loculated mass such as an abscess or hematoma. Further workup with additional imaging is warranted.

The working theory on this patient was that the density likely represented abscess or infection. Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest suggested likely abscess. The patient then underwent successful CT-guided needle biopsy, which returned positive results for Cryptococcus.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a right PICC line terminating at the superior vena cava. There is no evidence of pneumothorax.

Of note, however, is a large oval density within the right upper lobe, measuring 4.5 x 7 cm. This lesion could represent a loculated mass such as an abscess or hematoma. Further workup with additional imaging is warranted.

The working theory on this patient was that the density likely represented abscess or infection. Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest suggested likely abscess. The patient then underwent successful CT-guided needle biopsy, which returned positive results for Cryptococcus.

A 31-year-old man is admitted to your facility with presumed cryptococcal meningitis. He has a one-month history of progressively worsening headaches, malaise, weight loss, and blurred vision. A lumbar puncture demonstrates an extremely elevated opening pressure and yields samples that are positive for Cryptococcus on microscopic examination. The patient denies any significant medical history. Specifically, there is no history of HIV, which was confirmed by recent serologic testing at another hospital. As a result of poor peripheral access and with anticipated need for lengthy IV antifungal therapy, a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) line is ordered. It is placed without incident at the bedside, and as per protocol, a post-placement portable chest radiograph is obtained. What is your impression?

Chest Pain has "Gone On Long Enough"

ANSWER

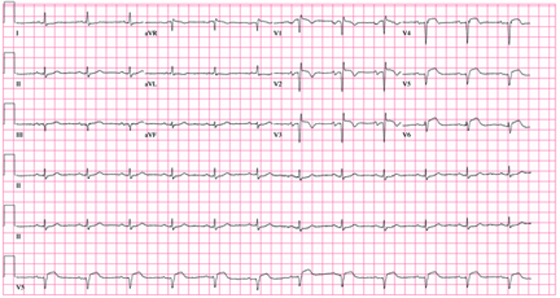

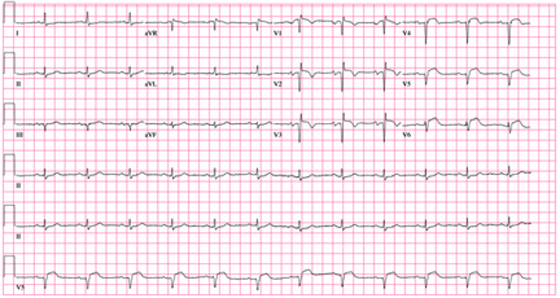

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and an anteroseptal myocardial infarction.

The diagnostic criteria for left atrial enlargement include a P-wave duration of ≥ 120 ms in lead II and/or a terminal negative component of a biphasic P wave in lead V1. In this example, the biphasic P wave is better seen in lead V2, while a large negative P wave is present in V1.

The diagnostic criteria for anteroseptal myocardial infarction include Q, QS, or QRS complexes in leads V1 through V4 along with evolving ST-T changes. In this example, leads V1 through V3 have large Q waves, while lead V4 has a large QS complex. All precordial leads contain ST-T wave elevations.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and an anteroseptal myocardial infarction.

The diagnostic criteria for left atrial enlargement include a P-wave duration of ≥ 120 ms in lead II and/or a terminal negative component of a biphasic P wave in lead V1. In this example, the biphasic P wave is better seen in lead V2, while a large negative P wave is present in V1.

The diagnostic criteria for anteroseptal myocardial infarction include Q, QS, or QRS complexes in leads V1 through V4 along with evolving ST-T changes. In this example, leads V1 through V3 have large Q waves, while lead V4 has a large QS complex. All precordial leads contain ST-T wave elevations.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and an anteroseptal myocardial infarction.

The diagnostic criteria for left atrial enlargement include a P-wave duration of ≥ 120 ms in lead II and/or a terminal negative component of a biphasic P wave in lead V1. In this example, the biphasic P wave is better seen in lead V2, while a large negative P wave is present in V1.

The diagnostic criteria for anteroseptal myocardial infarction include Q, QS, or QRS complexes in leads V1 through V4 along with evolving ST-T changes. In this example, leads V1 through V3 have large Q waves, while lead V4 has a large QS complex. All precordial leads contain ST-T wave elevations.

A 62-year-old African-American man presents to the urgent care center with a six-hour history of chest pain. He describes the pain as a “burning, achy” sensation with radiation to his left neck and shoulder. The pain started while the man was at rest but did not increase with activity. The patient denies symptoms such as shortness of breath, orthopnea, nausea, or vomiting. He says he had hoped the pain would resolve, but he now thinks it has “gone on long enough.” The patient has a history of similar chest pain four years ago. At that time, cardiac catheterization showed an 80% proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. A drug-eluting stent was placed from the origin to the mid vessel of the LAD. Although the patient has a prescription for nitroglycerin, he hasn’t filled it in three months because he hasn’t experienced chest pain in more than a year and wanted to save money. Medical history is remarkable for type 1 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, COPD, migraine, and diverticulitis. Surgical history is remarkable for an appendectomy during childhood. The patient is allergic to penicillin and cephalosporins. His current medication list includes insulin glargine, carvedilol, clopidogrel, ezetimibe, fenofibrate, hydrochlorothiazide, and aspirin (in addition to the nitroglycerin), but he has not taken any of these for two weeks due to financial constraints. The patient smokes 1½ packs of cigarettes daily and drinks an average of one case of beer per week. He does not know any details of his family history. The review of systems is remarkable for increased fatigue and weakness during the past week and for a migraine that the patient says is starting now. The physical exam reveals a blood pressure of 188/105 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 min-1; and temperature, 99°F. His weight is 119 lb, and his height is 68”. He is anxious, uncomfortable, and chronically ill appearing. Pertinent physical findings include pulmonary crackles in both bases, jugular venous distention to the angle of the jaw, a regular rate and rhythm with an S3 gallop, and a soft early systolic murmur at the left sternal border. He has no lower extremity edema, and his neurologic exam is intact. Abnormal laboratory data include: serum glucose of 318 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.6 mg/dL; troponin, 72 ng/mL; and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), 2,499 pg/mL. A stat ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 73 beats/min; PR interval, 160 ms; QRS duration, 88 ms; QT/QTc interval, 358/394; P axis, 39°; R axis, -3°; and T axis, 88°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

30-Year Rash that Flares in the Summertime

ANSWER

The correct answer is tinea pedis (choice “a”) of the moccasin variety (see “Discussion”). Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) is highly unlikely, given the lack of symptoms, the absence of vesiculation, and the duration of the problem. Unna-Thost syndrome (choice “c”) manifests with, among other things, plantar hyperkeratosis that is thick and fissured and looks like exaggerated callous formation. Plantar psoriasis (choice “d”) waxes and wanes and is seldom relegated to the sides of the feet. And while it is possible for psoriasis to affect only one area of the body (scalp, nails, or elbows), it is far more common for it to be seen in multiple areas, particularly in cases with a long duration, such as this one.

DISCUSSION

There are three common types of tinea pedis (dermatophytosis of the foot), but the moccasin variety (also called chronic hyperkeratotic type) is by far the most common and probably the least known. The classic interdigital type, with maceration and inflammation between either the fourth and fifth or third and fourth toes, is better known and therefore easier to diagnose. The third type of tinea pedis is inflammatory and typically presents with the sudden appearance of discrete vesicles and pustules on the non–weight-bearing portion of the sole; it is quite pruritic.

Given the appearance and complete lack of symptoms, moccasin-variety tinea pedis often goes unnoticed by the patient, or is written off as mere “dry skin” until a flare (usually in the summer) brings it back to mind. Patients often have a family history of similar problems; in this case, the patient’s mother was affected.

The KOH prep was positive in this case, showing numerous fungal elements that probably represented Trichophyton rubrum. This common dermatophyte also causes jock itch and onychomycosis, among other conditions. Fortunately, it is sensitive to most of the allylamines (eg, terbinafine) and imidazoles (eg, econazole or oxiconazole) in topical form.

Although the use of these medications can lead to marked improvement, a cure is most unlikely. Patients with this type of tinea pedis are probably susceptible to this “infection” and cannot avoid repeated re-exposure to the organism, which will be present in great numbers in their environment (shoes, socks, bedding, carpet).

After a thorough discussion of the diagnosis and prognosis, this patient was initially treated with OTC terbinafine cream, applied twice daily. Within two weeks, the frequency of application can be reduced to once or twice per week, especially during colder months; this should be sufficient to control the condition.

Of note, none of this woman’s immediate family has contracted tinea pedis, despite many years of exposure. This demonstrates the principle that susceptibility is probably more important than exposure.

ANSWER

The correct answer is tinea pedis (choice “a”) of the moccasin variety (see “Discussion”). Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) is highly unlikely, given the lack of symptoms, the absence of vesiculation, and the duration of the problem. Unna-Thost syndrome (choice “c”) manifests with, among other things, plantar hyperkeratosis that is thick and fissured and looks like exaggerated callous formation. Plantar psoriasis (choice “d”) waxes and wanes and is seldom relegated to the sides of the feet. And while it is possible for psoriasis to affect only one area of the body (scalp, nails, or elbows), it is far more common for it to be seen in multiple areas, particularly in cases with a long duration, such as this one.

DISCUSSION

There are three common types of tinea pedis (dermatophytosis of the foot), but the moccasin variety (also called chronic hyperkeratotic type) is by far the most common and probably the least known. The classic interdigital type, with maceration and inflammation between either the fourth and fifth or third and fourth toes, is better known and therefore easier to diagnose. The third type of tinea pedis is inflammatory and typically presents with the sudden appearance of discrete vesicles and pustules on the non–weight-bearing portion of the sole; it is quite pruritic.

Given the appearance and complete lack of symptoms, moccasin-variety tinea pedis often goes unnoticed by the patient, or is written off as mere “dry skin” until a flare (usually in the summer) brings it back to mind. Patients often have a family history of similar problems; in this case, the patient’s mother was affected.

The KOH prep was positive in this case, showing numerous fungal elements that probably represented Trichophyton rubrum. This common dermatophyte also causes jock itch and onychomycosis, among other conditions. Fortunately, it is sensitive to most of the allylamines (eg, terbinafine) and imidazoles (eg, econazole or oxiconazole) in topical form.

Although the use of these medications can lead to marked improvement, a cure is most unlikely. Patients with this type of tinea pedis are probably susceptible to this “infection” and cannot avoid repeated re-exposure to the organism, which will be present in great numbers in their environment (shoes, socks, bedding, carpet).

After a thorough discussion of the diagnosis and prognosis, this patient was initially treated with OTC terbinafine cream, applied twice daily. Within two weeks, the frequency of application can be reduced to once or twice per week, especially during colder months; this should be sufficient to control the condition.

Of note, none of this woman’s immediate family has contracted tinea pedis, despite many years of exposure. This demonstrates the principle that susceptibility is probably more important than exposure.

ANSWER

The correct answer is tinea pedis (choice “a”) of the moccasin variety (see “Discussion”). Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) is highly unlikely, given the lack of symptoms, the absence of vesiculation, and the duration of the problem. Unna-Thost syndrome (choice “c”) manifests with, among other things, plantar hyperkeratosis that is thick and fissured and looks like exaggerated callous formation. Plantar psoriasis (choice “d”) waxes and wanes and is seldom relegated to the sides of the feet. And while it is possible for psoriasis to affect only one area of the body (scalp, nails, or elbows), it is far more common for it to be seen in multiple areas, particularly in cases with a long duration, such as this one.

DISCUSSION

There are three common types of tinea pedis (dermatophytosis of the foot), but the moccasin variety (also called chronic hyperkeratotic type) is by far the most common and probably the least known. The classic interdigital type, with maceration and inflammation between either the fourth and fifth or third and fourth toes, is better known and therefore easier to diagnose. The third type of tinea pedis is inflammatory and typically presents with the sudden appearance of discrete vesicles and pustules on the non–weight-bearing portion of the sole; it is quite pruritic.

Given the appearance and complete lack of symptoms, moccasin-variety tinea pedis often goes unnoticed by the patient, or is written off as mere “dry skin” until a flare (usually in the summer) brings it back to mind. Patients often have a family history of similar problems; in this case, the patient’s mother was affected.

The KOH prep was positive in this case, showing numerous fungal elements that probably represented Trichophyton rubrum. This common dermatophyte also causes jock itch and onychomycosis, among other conditions. Fortunately, it is sensitive to most of the allylamines (eg, terbinafine) and imidazoles (eg, econazole or oxiconazole) in topical form.

Although the use of these medications can lead to marked improvement, a cure is most unlikely. Patients with this type of tinea pedis are probably susceptible to this “infection” and cannot avoid repeated re-exposure to the organism, which will be present in great numbers in their environment (shoes, socks, bedding, carpet).

After a thorough discussion of the diagnosis and prognosis, this patient was initially treated with OTC terbinafine cream, applied twice daily. Within two weeks, the frequency of application can be reduced to once or twice per week, especially during colder months; this should be sufficient to control the condition.

Of note, none of this woman’s immediate family has contracted tinea pedis, despite many years of exposure. This demonstrates the principle that susceptibility is probably more important than exposure.

A 53-year-old woman presents with a 30-year history of an asymptomatic rash on both feet. According to the patient, her mother had a similar condition. Over the years, the patient has tried any number of OTC moisturizers, thinking the rash was just dry skin that always worsened in the summertime. She has mentioned it to several medical providers, none of whom had any useful ideas about what it is or what to do about it. The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. She is not immunosuppressed and is taking no prescription medications. She further denies a personal or family history of any other skin problems. Examination reveals extensive marked desquamation of the sides of both feet. The scaling is quite fine and slightly erythematous. The well-demarcated annular proximal borders stop abruptly about halfway up the heel, involving the medial aspects of both big toes and the lateral aspects of both fifth toes. There is no involvement or maceration in the interdigital areas, and both soles are completely spared. Her skin elsewhere—including elbows, knees, nails, and scalp—is completely free of notable changes.

Parents Fear Infant May Have Skin Cancer

ANSWER

The correct answer is Mongolian spot (choice “a”), which is seen in about 90% of newborn Native Americans. True ecchymosis (choice “b”) would not persist beyond a few days at most. Blue nevus (choice “c”) is still possible, but unlikely given the archetypical presentation and commonality of this Mongolian spot. If serious consideration were to be given to either blue nevus or nevus of Ito (choice “d”), biopsy would have to be done. However, the latter is quite unusual, while the former is usually much smaller than the patient’s lesion.

DISCUSSION

The Mongolian spot, also known as congenital dermal melanocytosis, usually presents either at birth or shortly thereafter and disappears by age 4. It only involves the skin and results from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis. This case illustrates a typical location, but Mongolian spots can present as multiple lesions, usually on the posterior trunk, or as one large (> 20 cm) lesion. Fortunately, they are not associated with significant mortality or morbidity.

In addition to its high prevalence in Native Americans, Mongolian spots are seen on approximately 80% of Asian and 70% of Hispanic newborns, but less than 10% of white babies.

Blue nevi are quite common, representing a type of melanocytic nevus that is totally benign. Their color is actually brown, but these lesions develop relatively deep in the dermis and when viewed through the skin, appear blue—hence the name. Blue nevi, typically much smaller than our patient’s Mongolian spot, are often removed to rule out melanoma, which they can resemble at times.

The rare nevus of Ito represents a benign dermal melanocytic condition. It most commonly affects the shoulder.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Mongolian spot (choice “a”), which is seen in about 90% of newborn Native Americans. True ecchymosis (choice “b”) would not persist beyond a few days at most. Blue nevus (choice “c”) is still possible, but unlikely given the archetypical presentation and commonality of this Mongolian spot. If serious consideration were to be given to either blue nevus or nevus of Ito (choice “d”), biopsy would have to be done. However, the latter is quite unusual, while the former is usually much smaller than the patient’s lesion.

DISCUSSION

The Mongolian spot, also known as congenital dermal melanocytosis, usually presents either at birth or shortly thereafter and disappears by age 4. It only involves the skin and results from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis. This case illustrates a typical location, but Mongolian spots can present as multiple lesions, usually on the posterior trunk, or as one large (> 20 cm) lesion. Fortunately, they are not associated with significant mortality or morbidity.

In addition to its high prevalence in Native Americans, Mongolian spots are seen on approximately 80% of Asian and 70% of Hispanic newborns, but less than 10% of white babies.

Blue nevi are quite common, representing a type of melanocytic nevus that is totally benign. Their color is actually brown, but these lesions develop relatively deep in the dermis and when viewed through the skin, appear blue—hence the name. Blue nevi, typically much smaller than our patient’s Mongolian spot, are often removed to rule out melanoma, which they can resemble at times.

The rare nevus of Ito represents a benign dermal melanocytic condition. It most commonly affects the shoulder.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Mongolian spot (choice “a”), which is seen in about 90% of newborn Native Americans. True ecchymosis (choice “b”) would not persist beyond a few days at most. Blue nevus (choice “c”) is still possible, but unlikely given the archetypical presentation and commonality of this Mongolian spot. If serious consideration were to be given to either blue nevus or nevus of Ito (choice “d”), biopsy would have to be done. However, the latter is quite unusual, while the former is usually much smaller than the patient’s lesion.

DISCUSSION

The Mongolian spot, also known as congenital dermal melanocytosis, usually presents either at birth or shortly thereafter and disappears by age 4. It only involves the skin and results from entrapment of melanocytes in the dermis during their migration from the neural crest to the epidermis. This case illustrates a typical location, but Mongolian spots can present as multiple lesions, usually on the posterior trunk, or as one large (> 20 cm) lesion. Fortunately, they are not associated with significant mortality or morbidity.

In addition to its high prevalence in Native Americans, Mongolian spots are seen on approximately 80% of Asian and 70% of Hispanic newborns, but less than 10% of white babies.

Blue nevi are quite common, representing a type of melanocytic nevus that is totally benign. Their color is actually brown, but these lesions develop relatively deep in the dermis and when viewed through the skin, appear blue—hence the name. Blue nevi, typically much smaller than our patient’s Mongolian spot, are often removed to rule out melanoma, which they can resemble at times.

The rare nevus of Ito represents a benign dermal melanocytic condition. It most commonly affects the shoulder.

A 3-week-old infant is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on the sacral area. The lesion has been present since the child’s birth and has not changed since then. The child is otherwise healthy, and a pediatrician diagnosed the lesion as benign. However, the parents, who are both Native American, are nonetheless alarmed. Part of their concern relates to the possibility of trauma or skin cancer. The lesion is round, located on the lower left sacral area, and uniformly purple. The surface is totally macular and measures about 2.5 cm. Its margins are uniform, and no underlying induration or other changes can be palpated. No other notable lesions can be found on the child. Dermatoscopic examination shows uniform faint, bluish pigment.

Should This Man be Worried About Sudden Death?

ANSWER

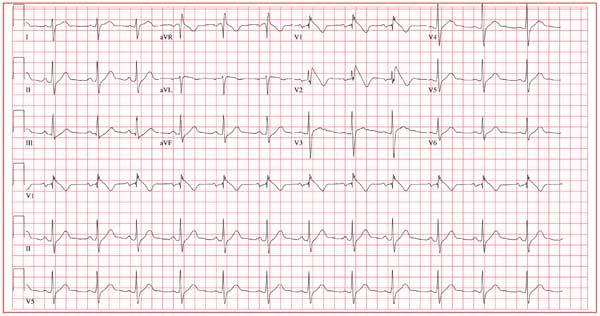

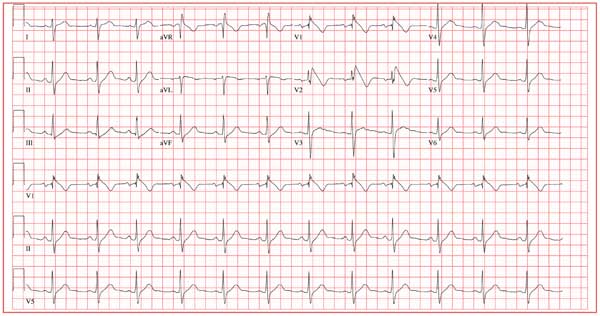

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, with a right-axis deviation (R wave axis > 90°) and a significant ST elevation noted in the anterior precordial leads consistent with a type 1 Brugada pattern. In this ECG, the elevated ST segment (≥ 2 mm) descends into an inverted T wave in leads V1 and V2.

The Brugada syndrome is due to a mutation in SCN5A, the alpha subunit of the cardiac sodium channel gene. Any clinical expression of the Brugada syndrome is related to ventricular arrhythmias, which are life-threatening.

Given his family history and his ECG, the patient is correct to be concerned. Genetic testing should be performed, and he should be referred for evaluation, including placement of an implantable defibrillator system for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

ANSWER

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, with a right-axis deviation (R wave axis > 90°) and a significant ST elevation noted in the anterior precordial leads consistent with a type 1 Brugada pattern. In this ECG, the elevated ST segment (≥ 2 mm) descends into an inverted T wave in leads V1 and V2.

The Brugada syndrome is due to a mutation in SCN5A, the alpha subunit of the cardiac sodium channel gene. Any clinical expression of the Brugada syndrome is related to ventricular arrhythmias, which are life-threatening.

Given his family history and his ECG, the patient is correct to be concerned. Genetic testing should be performed, and he should be referred for evaluation, including placement of an implantable defibrillator system for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

ANSWER

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, with a right-axis deviation (R wave axis > 90°) and a significant ST elevation noted in the anterior precordial leads consistent with a type 1 Brugada pattern. In this ECG, the elevated ST segment (≥ 2 mm) descends into an inverted T wave in leads V1 and V2.

The Brugada syndrome is due to a mutation in SCN5A, the alpha subunit of the cardiac sodium channel gene. Any clinical expression of the Brugada syndrome is related to ventricular arrhythmias, which are life-threatening.

Given his family history and his ECG, the patient is correct to be concerned. Genetic testing should be performed, and he should be referred for evaluation, including placement of an implantable defibrillator system for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

A 25-year-old Vietnamese man has lived in the United States since age 14. He was in his usual state of “excellent” health until one week ago, when he had an episode of syncope while walking along the shore of a lake with a friend. His friend told him that he lost consciousness without warning, fell to the ground, and promptly regained consciousness. He did not lose bowel or bladder control and did not injure himself. He attributed this episode to an insufficient intake of water on a hot, humid afternoon. Two days later, while talking to his father about the episode, he learned that he had a paternal uncle who died suddenly in his late 20s and a maternal aunt who died in her early 30s after similar episodes of syncope. Frightened that he may meet the same end, he presents to your clinic. He has no history of chest pain, palpitations, or dyspnea. Medical history is remarkable for an episode of pneumonia as a child. He has no known drug allergies and is currently taking no medications. He has smoked one pack of cigarettes per day since age 14, and he uses marijuana approximately twice a month. He drinks a six-pack of beer on weekends. He is married with no children and works in the IT department at a local community college. A detailed review of systems reveals no pertinent positive findings. He has had no loss of energy, trouble sleeping, or weight change (loss or gain). Physical examination reveals a blood pressure of 110/72 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min and regular; and respiratory rate, 14 min-1. He is afebrile. His height is 68”, and his weight, 151 lb. He is well nourished and in no acute distress. The HEENT, neck, chest, cardiovascular, abdominal, musculoskeletal, and neurologic exams are all normal. Blood chemistries, complete blood count, lipid profile, liver profile, and thyroid function studies are all normal. You assure the patient that he is in excellent health. He remains concerned, however, and asks that you order an ECG—a request to which you reluctantly agree. The ECG reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 75 beats/min; PR interval, 168 ms; QRS duration, 88 ms; QT/QTc interval, 390/435 ms; P axis, 73°; R axis, 112°; and T axis, 63°. What is your interpretation—and does the patient have a legitimate concern regarding his risk for dying suddenly?