User login

Man Thrown From All-Terrain Vehicle

ANSWER

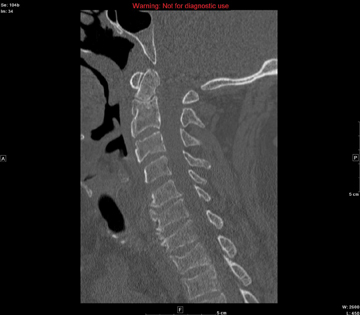

The image shows several things. First, there is a well-corticated lucency through the base of the odontoid process. This most likely represents what is referred to as an os odontoideum (congenital spinal variant). The other possibility is that it could be an old odontoid fracture with nonunion.

In addition, there are superior end-plate fractures noted in C6, C7, T1, and T2. However, no definite fracture lines are evident, suggesting these are subacute or old injuries. MRI can be performed to differentiate old versus new fractures; in this case, it was determined these were old.

ANSWER

The image shows several things. First, there is a well-corticated lucency through the base of the odontoid process. This most likely represents what is referred to as an os odontoideum (congenital spinal variant). The other possibility is that it could be an old odontoid fracture with nonunion.

In addition, there are superior end-plate fractures noted in C6, C7, T1, and T2. However, no definite fracture lines are evident, suggesting these are subacute or old injuries. MRI can be performed to differentiate old versus new fractures; in this case, it was determined these were old.

ANSWER

The image shows several things. First, there is a well-corticated lucency through the base of the odontoid process. This most likely represents what is referred to as an os odontoideum (congenital spinal variant). The other possibility is that it could be an old odontoid fracture with nonunion.

In addition, there are superior end-plate fractures noted in C6, C7, T1, and T2. However, no definite fracture lines are evident, suggesting these are subacute or old injuries. MRI can be performed to differentiate old versus new fractures; in this case, it was determined these were old.

A 57-year-old man is transferred to your facility after being thrown from an all-terrain vehicle. He was not wearing a helmet and was documented to have loss of consciousness. Upon arrival, his primary complaint is severe headache. He gives no significant medical history. Initial assessment shows a male on a backboard with full cervical spine immobilization. His Glasgow Coma Scale score is 14, with a blood pressure of 130/83 mm Hg and a heart rate of 87 beats/min. He has several abrasions on his face, but his pupils are equal and react well. His heart and lungs appear to be clear and the abdomen is benign. He is able to move all extremities well, with no obvious neurovascular compromise. After removal from the backboard, he is sent to the radiology department for multiple scans. A static sagittal image from CT of the cervical spine is shown. What is your impression?

Man Presents with Altered Mental Status and Confusion

ANSWER

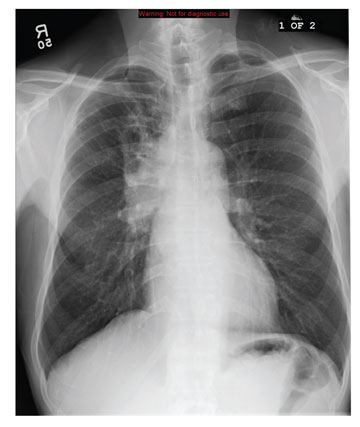

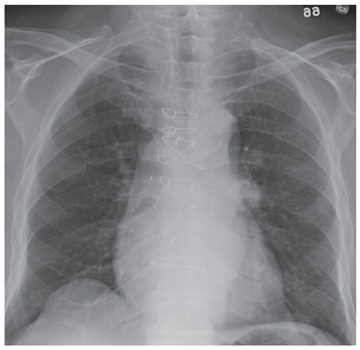

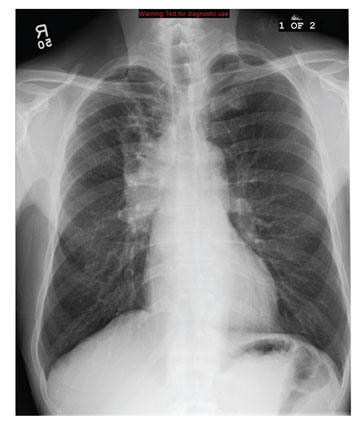

The chest radiograph demonstrates a fairly large right hilar mass with an associated right upper lobe infiltrate. This finding is very worrisome for a bronchogenic carcinoma.

Subsequent CT of the brain also demonstrated a right parietal mass. Thus, this lung lesion is most likely a primary neoplasm with metastatic involvement.

ANSWER

The chest radiograph demonstrates a fairly large right hilar mass with an associated right upper lobe infiltrate. This finding is very worrisome for a bronchogenic carcinoma.

Subsequent CT of the brain also demonstrated a right parietal mass. Thus, this lung lesion is most likely a primary neoplasm with metastatic involvement.

ANSWER

The chest radiograph demonstrates a fairly large right hilar mass with an associated right upper lobe infiltrate. This finding is very worrisome for a bronchogenic carcinoma.

Subsequent CT of the brain also demonstrated a right parietal mass. Thus, this lung lesion is most likely a primary neoplasm with metastatic involvement.

A 59-year-old man presents to your facility for evaluation of altered mental status and confusion that have progressively worsened in the past two months. He denies any injury or trauma. He states he has had associated headaches and dizziness. He denies any weight loss, shortness of breath, or malaise; however, he himself is able to notice that his mentation has “not been right.” His medical history is significant for mild hypertension and hyperlipidemia, both of which are well controlled. He discloses a 50–pack-year history of cigarette use. Physical exam reveals a male in no obvious distress but complaining of a moderate headache. His vital signs are stable. His oxygen saturation is 97% on room air. Breath sounds appear clear. The neurologic exam shows no focal deficits. You order noncontrast CT of the head, as well as a chest radiograph. The chest radiograph is shown. What is your impression?

Diagnosing a Sun Exposed Thumbnail

ANSWER

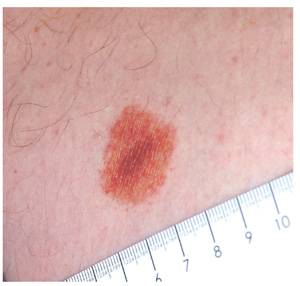

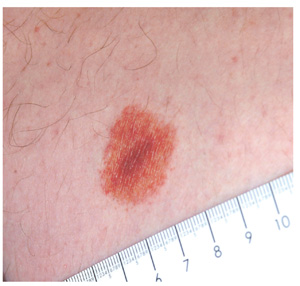

The correct answer is to biopsy the proximal origin of the lesion (choice “d”), because this lesion could represent a subungual melanoma, a potentially lethal cancer. In this patient’s case, with his personal sun damage and family history of melanoma, simple reassurance (choice “a”) would have been inappropriate. Submitting a portion of the distal nail plate to pathology (choice “b”) contributes nothing to the process of distinguishing benign from malignant. Seeing the patient every few months (choice “c”) ignores the present potentially dangerous situation, although it would at least keep the patient in the loop

DISCUSSION

The so-called acral lentiginous (AL) melanomas (by definition, on feet or hands, under nails, in oral tissues, or in perianal, scalp, and genital areas) are especially dangerous by virtue of location. Detection and removal are often delayed as a result.

While ALs constitute only 7% of melanomas overall, they account for more than half of all melanomas in Asian and black people. These patients have a far worse prognosis with AL than would be expected.

Subungual melanonychia is usually benign, but is suspicious for AL melanoma under certain circumstances. Patients at risk include:

• Those in their fifth to seventh decade of life

• Those who have a pigment stripe larger than 3 mm

• Those who experience changes in the lesion.

Thumbnails are especially at risk compared, for example, to the index fingernail or toenail. Other factors include extension of pigment onto surrounding paronychial skin (Hutchinson sign) and positive personal or family history of melanoma.

Our patient’s thumb lesion, his positive family history of melanoma, the width of his lesion, and his age all spoke to the need for biopsy. This can be done directly through the nail plate into the most proximal aspect of the lesion.

Alternatively, the cuticle can be surgically reflected proximally to facilitate removal of a portion of the proximal nail and subsequent biopsy or even removal of the lesion. Obviously, most patients with these lesions will need to be referred to dermatology for this procedure.

It is also important to note that by age 20, 77% of African-American patients will have developed at least one of these lesions. By age 50, virtually 100% of them will display the condition, often in the form of multiple lesions. These are almost always benign but bear watching for substantive change.

One should also be aware that 20% to 30% of all subungual melanomas are amelanotic—that is, they do not display dark pigment. Instead, they can be white, almost colorless, light tan, or even pink, so the key word is change.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to biopsy the proximal origin of the lesion (choice “d”), because this lesion could represent a subungual melanoma, a potentially lethal cancer. In this patient’s case, with his personal sun damage and family history of melanoma, simple reassurance (choice “a”) would have been inappropriate. Submitting a portion of the distal nail plate to pathology (choice “b”) contributes nothing to the process of distinguishing benign from malignant. Seeing the patient every few months (choice “c”) ignores the present potentially dangerous situation, although it would at least keep the patient in the loop

DISCUSSION

The so-called acral lentiginous (AL) melanomas (by definition, on feet or hands, under nails, in oral tissues, or in perianal, scalp, and genital areas) are especially dangerous by virtue of location. Detection and removal are often delayed as a result.

While ALs constitute only 7% of melanomas overall, they account for more than half of all melanomas in Asian and black people. These patients have a far worse prognosis with AL than would be expected.

Subungual melanonychia is usually benign, but is suspicious for AL melanoma under certain circumstances. Patients at risk include:

• Those in their fifth to seventh decade of life

• Those who have a pigment stripe larger than 3 mm

• Those who experience changes in the lesion.

Thumbnails are especially at risk compared, for example, to the index fingernail or toenail. Other factors include extension of pigment onto surrounding paronychial skin (Hutchinson sign) and positive personal or family history of melanoma.

Our patient’s thumb lesion, his positive family history of melanoma, the width of his lesion, and his age all spoke to the need for biopsy. This can be done directly through the nail plate into the most proximal aspect of the lesion.

Alternatively, the cuticle can be surgically reflected proximally to facilitate removal of a portion of the proximal nail and subsequent biopsy or even removal of the lesion. Obviously, most patients with these lesions will need to be referred to dermatology for this procedure.

It is also important to note that by age 20, 77% of African-American patients will have developed at least one of these lesions. By age 50, virtually 100% of them will display the condition, often in the form of multiple lesions. These are almost always benign but bear watching for substantive change.

One should also be aware that 20% to 30% of all subungual melanomas are amelanotic—that is, they do not display dark pigment. Instead, they can be white, almost colorless, light tan, or even pink, so the key word is change.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to biopsy the proximal origin of the lesion (choice “d”), because this lesion could represent a subungual melanoma, a potentially lethal cancer. In this patient’s case, with his personal sun damage and family history of melanoma, simple reassurance (choice “a”) would have been inappropriate. Submitting a portion of the distal nail plate to pathology (choice “b”) contributes nothing to the process of distinguishing benign from malignant. Seeing the patient every few months (choice “c”) ignores the present potentially dangerous situation, although it would at least keep the patient in the loop

DISCUSSION

The so-called acral lentiginous (AL) melanomas (by definition, on feet or hands, under nails, in oral tissues, or in perianal, scalp, and genital areas) are especially dangerous by virtue of location. Detection and removal are often delayed as a result.

While ALs constitute only 7% of melanomas overall, they account for more than half of all melanomas in Asian and black people. These patients have a far worse prognosis with AL than would be expected.

Subungual melanonychia is usually benign, but is suspicious for AL melanoma under certain circumstances. Patients at risk include:

• Those in their fifth to seventh decade of life

• Those who have a pigment stripe larger than 3 mm

• Those who experience changes in the lesion.

Thumbnails are especially at risk compared, for example, to the index fingernail or toenail. Other factors include extension of pigment onto surrounding paronychial skin (Hutchinson sign) and positive personal or family history of melanoma.

Our patient’s thumb lesion, his positive family history of melanoma, the width of his lesion, and his age all spoke to the need for biopsy. This can be done directly through the nail plate into the most proximal aspect of the lesion.

Alternatively, the cuticle can be surgically reflected proximally to facilitate removal of a portion of the proximal nail and subsequent biopsy or even removal of the lesion. Obviously, most patients with these lesions will need to be referred to dermatology for this procedure.

It is also important to note that by age 20, 77% of African-American patients will have developed at least one of these lesions. By age 50, virtually 100% of them will display the condition, often in the form of multiple lesions. These are almost always benign but bear watching for substantive change.

One should also be aware that 20% to 30% of all subungual melanomas are amelanotic—that is, they do not display dark pigment. Instead, they can be white, almost colorless, light tan, or even pink, so the key word is change.

A 51-year-old white man is seen for evaluation of a dark subungual stripe that appeared in his thumbnail six months ago. There are no symptoms to report and no history of trauma to the digit. His health is reportedly perfect otherwise. When questioned, the patient admits to regular unprotected sun exposure. He chalks this up to the necessity of yard work, both at home and at his family’s lake cabin, where they spend several weekends and holidays each year. The patient’s father died of melanoma years ago. On examination, a 3-mm-wide dark brown longitudinal stripe is seen on the affected fingernail, beginning in the distal lunular area and extending to the end of the nail plate. The margins of the stripe are quite even, as is the color. No such color changes are seen in the surrounding paronychial skin. The other fingernails and the toenails are free of changes. The patient is quite fair, with blue eyes, reddish brown hair, and modest dermatoheliosis. However, no distinctly worrisome lesions are seen.

Worsening Symptoms in Woman with Cystic Fibrosis

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus tachycardia with a short PR interval. This ECG illustrates a physiologic sinus rate response to hypercarbic respiratory failure secondary to an infectious exacerbation. A shortened PR interval occurs with an otherwise healthy conduction system in response to a rapid sinus tachycardia.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus tachycardia with a short PR interval. This ECG illustrates a physiologic sinus rate response to hypercarbic respiratory failure secondary to an infectious exacerbation. A shortened PR interval occurs with an otherwise healthy conduction system in response to a rapid sinus tachycardia.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus tachycardia with a short PR interval. This ECG illustrates a physiologic sinus rate response to hypercarbic respiratory failure secondary to an infectious exacerbation. A shortened PR interval occurs with an otherwise healthy conduction system in response to a rapid sinus tachycardia.

A 23-year-old woman with cystic fibrosis presents to the pulmonary medicine clinic for follow-up to a hospitalization one month ago for an infectious exacerbation of her condition. She has had four hospital admissions over the past year and is known to be chronically colonized with multidrug resistant Pseudomonas. Two days ago, she began feeling significantly more short of breath, with increasing home oxygen requirements (4 L at baseline, up to 10 L by nasal cannula), as well as increasing phlegm production and a fever of 100°F. She states she feels dehydrated, sleepy, and nauseous. In addition to cystic fibrosis, her medical history is remarkable for pancreatic insufficiency, diabetes, chronic sinus infections, and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Family history is positive for hyperlipidemia and congestive heart failure. No other family members have a diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Her medication list includes azithromycin, insulin glargine, insulin isophane, insulin lispro sliding scale, insulin regular, loratadine, omeprazole, pancrelipase, prednisone, simvastatin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and a tobramycin inhaler. She is allergic to cephalosporin antibiotics. A quick review of systems reveals no other issues. Physical examination reveals a woman in extreme distress who is able to nod to questions and answer briefly but is unable to speak in full sentences. Her blood pressure is 136/82 mm Hg, with a mean arterial pressure of 99 mm Hg; pulse, 170 beats/min and thready; respiratory rate, 40 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 39.2°C. O2 saturation is 89% on 10 L of oxygen via facemask. The pulmonary exam reveals coarse bilateral crackles, worst at the bases, with associated intercostal and supraclavicular muscular retractions. The cardiac exam reveals no jugular venous distention. Her rate is rapid and regular with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdomen is soft and nontender, with normal bowel sounds. The extremities are warm, well perfused, and without edema. The neurologic exam is grossly normal without focal signs. A stat arterial blood gas reveals respiratory acidosis with a pH of 7.32 and a pCO2 of 83 mm Hg. A complete blood count reveals a white blood cell count of 34 x 109/L. You decide to admit her to the medical intensive care unit. You are concerned that her heart rate of 170 beats/min may be atrial flutter and obtain an ECG, which reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 177 beats/min; PR interval, 88 ms; QRS duration, 60 ms; QT/QTc interval, 238/408 ms; P axis, 67°; R axis, 76°; and T axis, 73°. What is your diagnosis?

What is the Next Step in Dealing With This Lesion?

DISCUSSION

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

DISCUSSION

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

DISCUSSION

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

An 18-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic lesion that has been present on his left inner thigh for several months. The lesion has persisted despite the use of a topical cream containing clotrimazole and betamethasone (applied twice daily for a week) and a subsequent 10-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d). Neither treatment seems to have had any impact. There is no history of antecedent trauma. The patient and his family report that no other lesions have been noted and that the patient is quite healthy in other respects. However, there is a family history of melanoma, which has caused the parents more than a little concern. Examination reveals a 3-cm reddish brown polygonal macule with a darker center, located on the left inner thigh. The lesion is neither palpable nor blanchable with digital pressure. No such lesions are seen elsewhere on the patient’s body.

Elderly Man with Headaches and Weakness

ANSWER

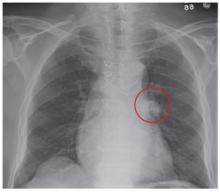

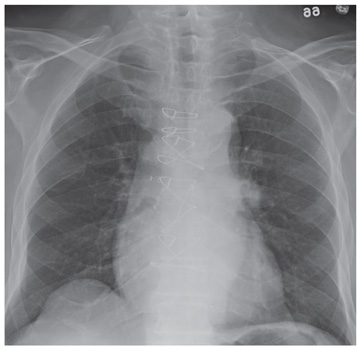

The chest radiograph demonstrates evidence of previous sternotomy. No evidence of acute infiltrate is noted.

However, there is a prominence within the left hilar region. This finding is strongly suggestive of neoplasm until proven otherwise. The patient was promptly referred for CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which confirmed the lesion. Subsequent CT-guided biopsy was performed.

ANSWER

The chest radiograph demonstrates evidence of previous sternotomy. No evidence of acute infiltrate is noted.

However, there is a prominence within the left hilar region. This finding is strongly suggestive of neoplasm until proven otherwise. The patient was promptly referred for CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which confirmed the lesion. Subsequent CT-guided biopsy was performed.

ANSWER

The chest radiograph demonstrates evidence of previous sternotomy. No evidence of acute infiltrate is noted.

However, there is a prominence within the left hilar region. This finding is strongly suggestive of neoplasm until proven otherwise. The patient was promptly referred for CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which confirmed the lesion. Subsequent CT-guided biopsy was performed.

A 71-year-old man presents with complaints of headaches and weakness that have been ongoing for almost a month. He denies any fever, nausea, or vomiting. He has noticed an occasional cough and denies any weight loss. The patient has an extensive history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. History is also significant for coronary artery bypass grafting. He denies any history of smoking. The man is afebrile, and the rest of his vital signs, including pulse oximetry, are within normal limits. Physical exam shows an elderly, ill-appearing man in no obvious distress. Breath sounds bilaterally are clear. You order a chest radiograph along with some bloodwork. The chest radiograph is shown. What is your impression?

Just a Case of The Flu?

ANSWER

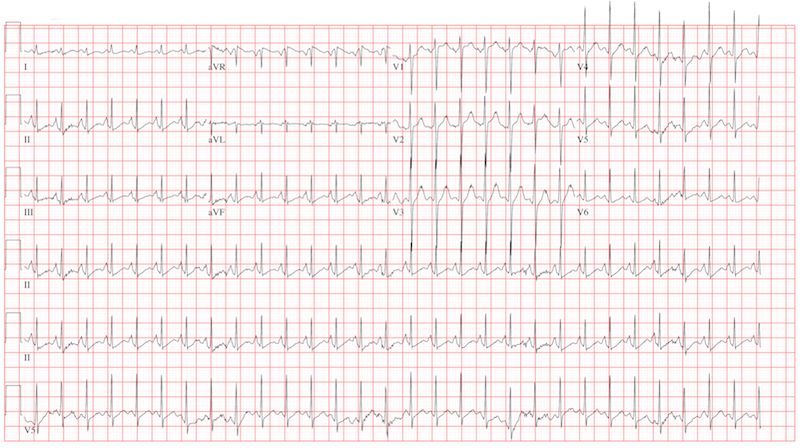

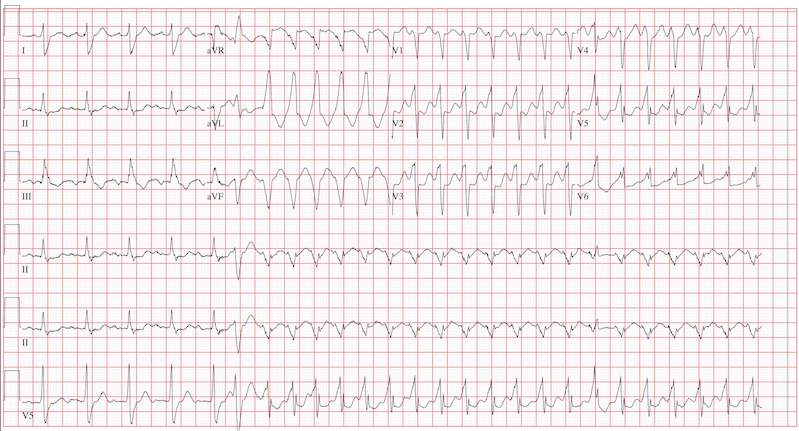

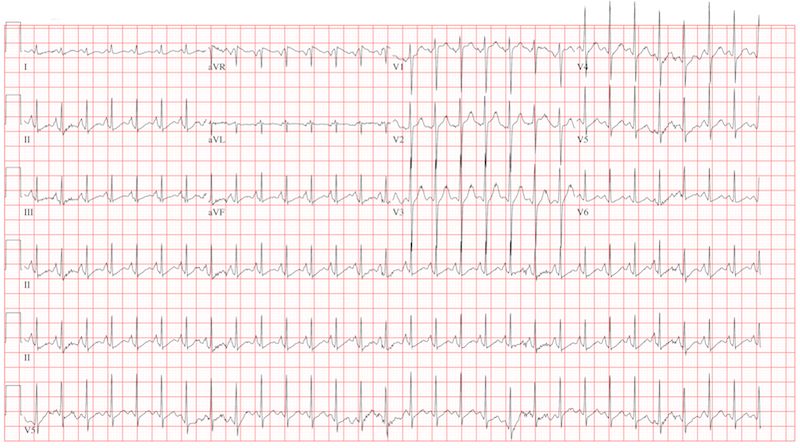

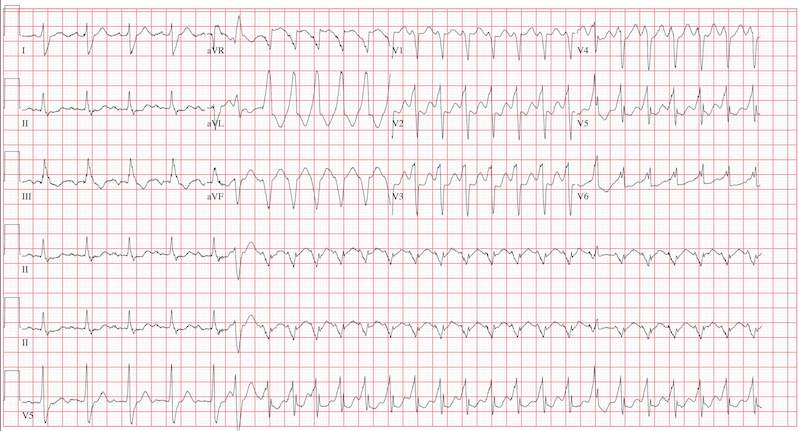

This ECG reveals sinus tachycardia transitioning to a wide complex tachycardia. A fusion complex is present, suggesting this is ventricular tachycardia. T-wave abnormalities in the inferior leads are present and suggest inferior ischemia.

There are two items of note that one must be aware of in order to accurately interpret this ECG. Normally, the computer measurements of heart rate and intervals are correct and often more accurate than a clinician can manually measure. These are typically measured as an average of all beats taken during the 12-second analysis prior to printing. However, when the rate abruptly changes during the analysis of the heart rate and rhythm, these measurements become inaccurate.

In this ECG, the computer notes the rate to be 156 beats/min; however, careful analysis of the sinus tachycardia prior to onset of ventricular tachycardia shows the rate is 107 beats/min, and the ventricular tachycardia rate is 188 beats/min.

The second item of note is that the ECG instrument measures all leads simultaneously over a 12-second period and separates them into the appropriate leads for printing. Hence, the progression from leads I to aVR to V1 to V4 represents a continuous tracing, in a similar fashion to the rhythm strip in lead II at the bottom of the page. Knowing this can help determine the presence of fusion complexes, as well as atrioventricular dissociation between QRS complexes and P waves indicative of ventricular tachycardia.

This patient developed hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia during the 12-second interval required for a 12-lead ECG analysis, a rare occurrence. She was treated with DC cardioversion, which resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm.

ANSWER

This ECG reveals sinus tachycardia transitioning to a wide complex tachycardia. A fusion complex is present, suggesting this is ventricular tachycardia. T-wave abnormalities in the inferior leads are present and suggest inferior ischemia.

There are two items of note that one must be aware of in order to accurately interpret this ECG. Normally, the computer measurements of heart rate and intervals are correct and often more accurate than a clinician can manually measure. These are typically measured as an average of all beats taken during the 12-second analysis prior to printing. However, when the rate abruptly changes during the analysis of the heart rate and rhythm, these measurements become inaccurate.

In this ECG, the computer notes the rate to be 156 beats/min; however, careful analysis of the sinus tachycardia prior to onset of ventricular tachycardia shows the rate is 107 beats/min, and the ventricular tachycardia rate is 188 beats/min.

The second item of note is that the ECG instrument measures all leads simultaneously over a 12-second period and separates them into the appropriate leads for printing. Hence, the progression from leads I to aVR to V1 to V4 represents a continuous tracing, in a similar fashion to the rhythm strip in lead II at the bottom of the page. Knowing this can help determine the presence of fusion complexes, as well as atrioventricular dissociation between QRS complexes and P waves indicative of ventricular tachycardia.

This patient developed hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia during the 12-second interval required for a 12-lead ECG analysis, a rare occurrence. She was treated with DC cardioversion, which resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm.

ANSWER

This ECG reveals sinus tachycardia transitioning to a wide complex tachycardia. A fusion complex is present, suggesting this is ventricular tachycardia. T-wave abnormalities in the inferior leads are present and suggest inferior ischemia.

There are two items of note that one must be aware of in order to accurately interpret this ECG. Normally, the computer measurements of heart rate and intervals are correct and often more accurate than a clinician can manually measure. These are typically measured as an average of all beats taken during the 12-second analysis prior to printing. However, when the rate abruptly changes during the analysis of the heart rate and rhythm, these measurements become inaccurate.

In this ECG, the computer notes the rate to be 156 beats/min; however, careful analysis of the sinus tachycardia prior to onset of ventricular tachycardia shows the rate is 107 beats/min, and the ventricular tachycardia rate is 188 beats/min.

The second item of note is that the ECG instrument measures all leads simultaneously over a 12-second period and separates them into the appropriate leads for printing. Hence, the progression from leads I to aVR to V1 to V4 represents a continuous tracing, in a similar fashion to the rhythm strip in lead II at the bottom of the page. Knowing this can help determine the presence of fusion complexes, as well as atrioventricular dissociation between QRS complexes and P waves indicative of ventricular tachycardia.

This patient developed hemodynamically significant ventricular tachycardia during the 12-second interval required for a 12-lead ECG analysis, a rare occurrence. She was treated with DC cardioversion, which resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm.

An 80-year-old woman presents to the emergency department (ED) with chest tightness and palpitations over the past three hours. She called her primary care provider to make an appointment, but was prompted to go directly to the ED. She was transported by her granddaughter, who remains with her. The patient tries to downplay her symptoms as “a case of the flu”; however, the granddaughter states that for the past two weeks, her grandmother has had increased shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, a six-pound weight gain, and bilateral lower extremity edema not previously present. The patient denies fevers, chills, productive cough, syncope, or near-syncope. Medical history is remarkable for a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement (21-mm Carpentier-Edwards pericardial valve) in May 2008 for critical aortic stenosis, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation requiring cardioversion on two separate occasions (the last, six months ago). Her most recent echocardiogram (one year ago) was remarkable for bioprosthetic aortic valve dysfunction with a peak gradient of 60 mm Hg across the valve, well preserved left ventricular systolic function without segmental contraction abnormalities, and mild diastolic dysfunction with a left ventricular ejection fraction estimated to be 55%. Associated findings included mild to moderate mitral regurgitation and left atrial enlargement. Her right heart and central venous pressures were normal. Medical history is also remarkable for a recent (four months ago) episode of shingles involving her left chest and flank. The patient is a retired librarian, is self-sufficient, and lives alone. Her granddaughter lives across the street from her and checks on her daily. The patient has never smoked and has an occasional glass of wine. Her current medications include furosemide, pravastatin, metoprolol XL, a multivitamin, and sublingual nitroglycerin as needed. Of note, she did not use the sublingual nitroglycerin prior to presenting to the ED, and upon inspection, the prescription is long past its expiration date. Physical examination reveals a blood pressure of 92/66 mm Hg; pulse, 100 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min. The patient is afebrile. Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distention to the level of the jaw, lungs that are clear to auscultation, a musical grade III/VI systolic murmur best heard at the apex with radiation to the carotid arteries bilaterally, a benign abdominal exam, and 3+ pitting edema to the level of the mid-thigh bilaterally. The neurologic exam is grossly intact. Suspecting another episode of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, you order an ECG. The ECG technician arrives, connects the electrodes to the patient, and promptly calls for help as the patient’s chest tightness returns and she becomes lightheaded and dizzy. You arrive promptly and are handed the ECG, which shows: a ventricular rate of 156 beats/min; PR interval, 190 ms; QRS duration, 138 ms; QT/QTc, 362/583 ms; P axis, –5°; R axis, 114°; and T axis, 0°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Car Accident and a Language Barrier

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an obvious deformity in the distal humerus consistent with an old fracture with chronic malunion. There is no evidence of a superimposed acute fracture.

Once family and interpreters became available, it was elicited that the patient, who is originally from Nepal, did sustain a childhood injury and broke his right arm. No acute intervention was required.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an obvious deformity in the distal humerus consistent with an old fracture with chronic malunion. There is no evidence of a superimposed acute fracture.

Once family and interpreters became available, it was elicited that the patient, who is originally from Nepal, did sustain a childhood injury and broke his right arm. No acute intervention was required.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an obvious deformity in the distal humerus consistent with an old fracture with chronic malunion. There is no evidence of a superimposed acute fracture.

Once family and interpreters became available, it was elicited that the patient, who is originally from Nepal, did sustain a childhood injury and broke his right arm. No acute intervention was required.

You are asked to see a 41-year-old man complaining of right upper arm pain. He was brought in by EMS from a reported single-vehicle crash, in which he was one of approximately 15 people traveling in a van. The patient speaks little to no English, and details of the accident are sketchy. Best as can be ascertained, the vehicle either went out of control or was hit and ran off the road. There were known fatalities at the scene. Due to language barriers, history is limited. Physical exam shows a middle-aged Asian man who appears quite uncomfortable. He indicates he is hurting in his chest, back, and right arm. His vital signs are normal, and primary survey appears stable, with the patient having multiple abrasions on his face and whole body. Examination of his right arm shows multiple abrasions with some bruising and swelling, as well as a deformity just above the elbow. The patient is able to slowly move his wrist and fingers. Distal pulses and sensation appear intact. Radiograph of the right humerus is shown. What is your impression?

Exertional Dyspnea Forces Man to Leave Job and Gain Weight

ANSWER

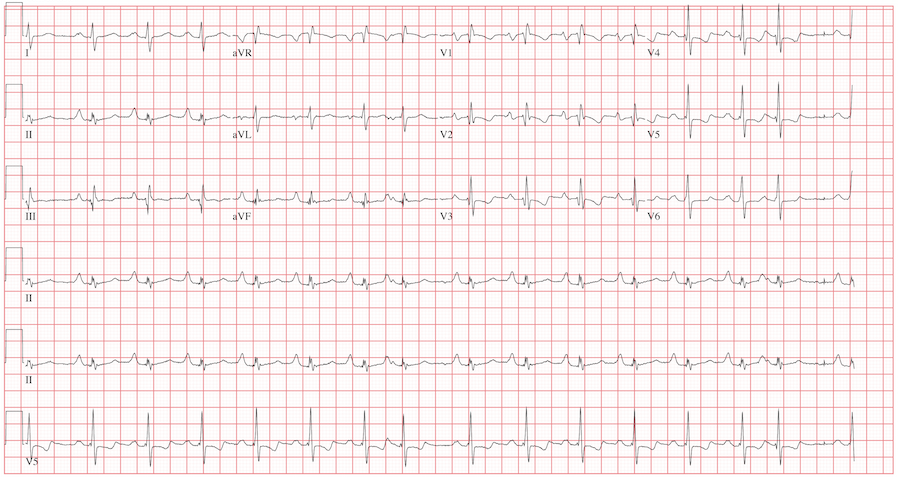

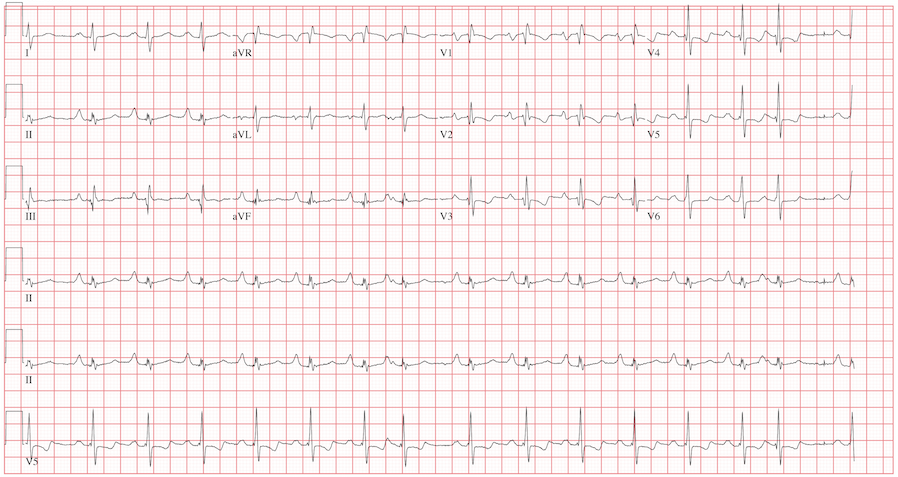

The ECG reveals sinus rhythm with a marked sinus arrhythmia, biatrial enlargement, incomplete right bundle branch block, right ventricular hypertrophy, ST and T wave abnormalities in the anterolateral precordial leads, and a prolonged QT interval.

There is a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, and each P wave is similar in its respective lead (sinus rhythm); however, the rate is irregular, hence the diagnosis of marked sinus arrhythmia. Biatrial enlargement is illustrated by the presence of notched P waves in leads I and V1 with peaked P waves in leads II, III, and aVF (right atrial enlargement) and a P wave ≥ 110 ms in lead I with a terminally negative P wave ≥ 1 mm2 in V1 (left atrial enlargement).

An incomplete right bundle branch block is illustrated by the presence of an RSR’ in lead V1 with a small R and a QRS duration which is borderline normal (< 100 ms). Right ventricular hypertrophy is demonstrated by the presence of a tall R wave in V1 (in this case, R’) that is ≥ S wave in V1, an inverted T wave in V1, borderline right-axis deviation (R axis, 90°), and right atrial enlargement.

ST and T wave changes in the lateral leads are suggestive of anterolateral ischemia; however, in this case they are indicative of repolarization changes from right ventricular enlargement and an incomplete right bundle branch block. Finally, QT prolongation is suggested by the presence of a QT interval > 400 ms in a man when corrected for rate.

The patient’s history, physical examination, and ECG are highly suspicious for right-sided heart failure with the presence of jugular venous distention, a murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, hepatic congestion, and peripheral edema, as well as ECG documentation of right atrial and ventricular enlargement (cor pulmonale). An echocardiogram subsequently confirmed the diagnosis and also revealed pulmonary hypertension, with pulmonary artery pressures of 70 mm Hg.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals sinus rhythm with a marked sinus arrhythmia, biatrial enlargement, incomplete right bundle branch block, right ventricular hypertrophy, ST and T wave abnormalities in the anterolateral precordial leads, and a prolonged QT interval.

There is a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, and each P wave is similar in its respective lead (sinus rhythm); however, the rate is irregular, hence the diagnosis of marked sinus arrhythmia. Biatrial enlargement is illustrated by the presence of notched P waves in leads I and V1 with peaked P waves in leads II, III, and aVF (right atrial enlargement) and a P wave ≥ 110 ms in lead I with a terminally negative P wave ≥ 1 mm2 in V1 (left atrial enlargement).

An incomplete right bundle branch block is illustrated by the presence of an RSR’ in lead V1 with a small R and a QRS duration which is borderline normal (< 100 ms). Right ventricular hypertrophy is demonstrated by the presence of a tall R wave in V1 (in this case, R’) that is ≥ S wave in V1, an inverted T wave in V1, borderline right-axis deviation (R axis, 90°), and right atrial enlargement.

ST and T wave changes in the lateral leads are suggestive of anterolateral ischemia; however, in this case they are indicative of repolarization changes from right ventricular enlargement and an incomplete right bundle branch block. Finally, QT prolongation is suggested by the presence of a QT interval > 400 ms in a man when corrected for rate.

The patient’s history, physical examination, and ECG are highly suspicious for right-sided heart failure with the presence of jugular venous distention, a murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, hepatic congestion, and peripheral edema, as well as ECG documentation of right atrial and ventricular enlargement (cor pulmonale). An echocardiogram subsequently confirmed the diagnosis and also revealed pulmonary hypertension, with pulmonary artery pressures of 70 mm Hg.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals sinus rhythm with a marked sinus arrhythmia, biatrial enlargement, incomplete right bundle branch block, right ventricular hypertrophy, ST and T wave abnormalities in the anterolateral precordial leads, and a prolonged QT interval.

There is a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, and each P wave is similar in its respective lead (sinus rhythm); however, the rate is irregular, hence the diagnosis of marked sinus arrhythmia. Biatrial enlargement is illustrated by the presence of notched P waves in leads I and V1 with peaked P waves in leads II, III, and aVF (right atrial enlargement) and a P wave ≥ 110 ms in lead I with a terminally negative P wave ≥ 1 mm2 in V1 (left atrial enlargement).

An incomplete right bundle branch block is illustrated by the presence of an RSR’ in lead V1 with a small R and a QRS duration which is borderline normal (< 100 ms). Right ventricular hypertrophy is demonstrated by the presence of a tall R wave in V1 (in this case, R’) that is ≥ S wave in V1, an inverted T wave in V1, borderline right-axis deviation (R axis, 90°), and right atrial enlargement.

ST and T wave changes in the lateral leads are suggestive of anterolateral ischemia; however, in this case they are indicative of repolarization changes from right ventricular enlargement and an incomplete right bundle branch block. Finally, QT prolongation is suggested by the presence of a QT interval > 400 ms in a man when corrected for rate.

The patient’s history, physical examination, and ECG are highly suspicious for right-sided heart failure with the presence of jugular venous distention, a murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, hepatic congestion, and peripheral edema, as well as ECG documentation of right atrial and ventricular enlargement (cor pulmonale). An echocardiogram subsequently confirmed the diagnosis and also revealed pulmonary hypertension, with pulmonary artery pressures of 70 mm Hg.

A 42-year-old man has a two-year history of exertional dyspnea. In the past six months, his condition has become significant enough to force him to leave his job as a general contractor. He presents today with dizziness while standing, but not while walking. He denies syncope or near-syncope, angina, or palpitations. He says he has gained weight over the past month, to the extent that his clothes no longer fit. He attributes this to not working or exercising, and he believes this may be the cause of his increased exertional dyspnea. Medical history is remarkable for pneumonia 10 years ago. Surgical history is remarkable for repair of a right femoral fracture sustained in an automobile accident at age 17. The patient has worked in construction and as a general contractor, but had to stop two months ago secondary to dyspnea and chronic fatigue. He is unmarried, is active in his church, does not smoke or drink, and denies recreational drug use. His father died at 66 of lung cancer related to smoking. His mother and three siblings are alive and in good health. He is not allergic to any known medications, and his current medications include ibuprofen as needed for muscular aches and pains and an aspirin a day “because my dad’s doctor recommended it.” The review of systems is remarkable for fatigue despite the fact that the patient has been getting plenty of sleep. His girlfriend says he has been snoring loudly for the past two weeks and has never snored in the past. The man also states that he has had vague abdominal discomfort, without change in his bowel or bladder habits, and has noticed swelling in his lower extremities. He is alarmed to find out he has gained 24 lb in the past month. The physical exam reveals an anxious, obese, white man with a weight of 298 lb. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 114/80 mm Hg; pulse, 94 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 90% on room air. He is afebrile. Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distention to the angle of the jaw and lungs that are clear to auscultation with a few late expiratory wheezes. The cardiac exam reveals distant heart sounds with a grade III/VI holosystolic low-frequency murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border. The abdominal exam is remarkable for mild hepatomegaly, which is tender to deep palpation. The lower extremities demonstrate 2+ pitting edema to the level of the knees bilaterally. The neurologic exam is intact. Laboratory blood work, an echocardiogram, and an ECG are ordered. The ECG is performed first and reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 94 beats/min; PR interval, 186 ms; QRS duration, 98 ms; QT/QTc interval, 384/480 ms; P axis, 62°; R axis, 90°; and T axis, 48°. What is your interpretation of this ECG, and how does it correlate with the history and physical exam?

Soap and Water Will Not Clean Dirty Skin

ANSWER

The correct answer is terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD; choice “d”), also known as “Duncan’s dirty dermatosis.” This relatively common condition usually affects adolescents and is one of the very few causes of hyperpigmentation that can be removed specifically with alcohol.

Dirty skin (choice “a”) is certainly seen, especially in this age-group, but the dirt is easily removed with soap and water.

Acanthosis nigricans (choice “b”) is often mistaken for dirty skin, but it cannot be removed by any nondestructive modality. Moreover, the most common form of acanthosis nigricans presents with a velvety, faintly raised brownish discoloration that usually affects the circumferential neck, axillae, and often, other intertriginous areas.

Reticulated and confluent papillomatosis (choice “c”) is a rare condition seen on the chest, back, and occasionally the face. It involves a slightly papular reticular (a netlike effect) patch, often in a triangular shape. Alcohol has no effect on it.

DISCUSSION

TFFD is surprisingly common, once its existence is recognized. Its etiology is, as one might expect, unknown, but it has been described in the literature (see “Suggested Reading” for examples) and is also defined by predictable histologic features seen on biopsy.

Besides the obvious implications, TFFD is probably most important as an imitator of acanthosis nigricans, which is often seen in overweight adolescents on their way to becoming diabetic. Unlike TFFD, acanthosis nigricans (type III, the most common form) has a multitude of potentially serious implications, although it is most often benign. Besides its well-known potential connection with diabetes, acanthosis nigricans can be seen in a myriad of insulin-resistant states and a bewildering variety of endocrinopathies.

SUMMARY

Unnecessary treatments and/or workups can be avoided by being aware of the existence of this common condition, which is easily diagnosed (and treated!) by wiping with alcohol—effectively ruling out the other items in the differential.

SUGGESTED READING

Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123(5):567-569.

Pavlovic MD, Dragos V, Potocnik M, Adamic M. Terra firma-forme dermatosis in a child. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2008;17(1):41-42.

ANSWER

The correct answer is terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD; choice “d”), also known as “Duncan’s dirty dermatosis.” This relatively common condition usually affects adolescents and is one of the very few causes of hyperpigmentation that can be removed specifically with alcohol.

Dirty skin (choice “a”) is certainly seen, especially in this age-group, but the dirt is easily removed with soap and water.

Acanthosis nigricans (choice “b”) is often mistaken for dirty skin, but it cannot be removed by any nondestructive modality. Moreover, the most common form of acanthosis nigricans presents with a velvety, faintly raised brownish discoloration that usually affects the circumferential neck, axillae, and often, other intertriginous areas.

Reticulated and confluent papillomatosis (choice “c”) is a rare condition seen on the chest, back, and occasionally the face. It involves a slightly papular reticular (a netlike effect) patch, often in a triangular shape. Alcohol has no effect on it.

DISCUSSION

TFFD is surprisingly common, once its existence is recognized. Its etiology is, as one might expect, unknown, but it has been described in the literature (see “Suggested Reading” for examples) and is also defined by predictable histologic features seen on biopsy.

Besides the obvious implications, TFFD is probably most important as an imitator of acanthosis nigricans, which is often seen in overweight adolescents on their way to becoming diabetic. Unlike TFFD, acanthosis nigricans (type III, the most common form) has a multitude of potentially serious implications, although it is most often benign. Besides its well-known potential connection with diabetes, acanthosis nigricans can be seen in a myriad of insulin-resistant states and a bewildering variety of endocrinopathies.

SUMMARY

Unnecessary treatments and/or workups can be avoided by being aware of the existence of this common condition, which is easily diagnosed (and treated!) by wiping with alcohol—effectively ruling out the other items in the differential.

SUGGESTED READING

Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123(5):567-569.

Pavlovic MD, Dragos V, Potocnik M, Adamic M. Terra firma-forme dermatosis in a child. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2008;17(1):41-42.

ANSWER

The correct answer is terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD; choice “d”), also known as “Duncan’s dirty dermatosis.” This relatively common condition usually affects adolescents and is one of the very few causes of hyperpigmentation that can be removed specifically with alcohol.

Dirty skin (choice “a”) is certainly seen, especially in this age-group, but the dirt is easily removed with soap and water.

Acanthosis nigricans (choice “b”) is often mistaken for dirty skin, but it cannot be removed by any nondestructive modality. Moreover, the most common form of acanthosis nigricans presents with a velvety, faintly raised brownish discoloration that usually affects the circumferential neck, axillae, and often, other intertriginous areas.

Reticulated and confluent papillomatosis (choice “c”) is a rare condition seen on the chest, back, and occasionally the face. It involves a slightly papular reticular (a netlike effect) patch, often in a triangular shape. Alcohol has no effect on it.

DISCUSSION

TFFD is surprisingly common, once its existence is recognized. Its etiology is, as one might expect, unknown, but it has been described in the literature (see “Suggested Reading” for examples) and is also defined by predictable histologic features seen on biopsy.

Besides the obvious implications, TFFD is probably most important as an imitator of acanthosis nigricans, which is often seen in overweight adolescents on their way to becoming diabetic. Unlike TFFD, acanthosis nigricans (type III, the most common form) has a multitude of potentially serious implications, although it is most often benign. Besides its well-known potential connection with diabetes, acanthosis nigricans can be seen in a myriad of insulin-resistant states and a bewildering variety of endocrinopathies.

SUMMARY

Unnecessary treatments and/or workups can be avoided by being aware of the existence of this common condition, which is easily diagnosed (and treated!) by wiping with alcohol—effectively ruling out the other items in the differential.

SUGGESTED READING

Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123(5):567-569.

Pavlovic MD, Dragos V, Potocnik M, Adamic M. Terra firma-forme dermatosis in a child. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2008;17(1):41-42.

The mother of a 14-year-old girl brings the child into your clinic, essentially to gain support in her effort to convince the child to wash better. It seems that several times a year, areas of the girl’s arms and neck appear to be dirty, despite protestations of adequate washing by the patient, who will not let her mother (or anyone else, to date) scrub the areas. The patient denies having any symptoms in the affected areas and further denies applying any medication to them. She wears no jewelry that might have touched the areas. According to the mother and the patient, the latter is otherwise healthy. She almost never takes any medication, and she had normal blood work (including blood sugar) as part of a recent physical exam. There is no family history of serious health problems, such as diabetes or skin diseases. The child seldom exerts to the point of perspiration, although she does swim once or twice a week for exercise. You note that the child is moderately overweight and quite reluctant to allow anyone to see or touch the areas in question. But with considerable time and much persuasion, she allows you to examine and palpate her skin, which has a slight olive tone (type IV). The ill-defined, light brown macular discoloration stands out and indeed looks like dirt. However, it is confined to the patient’s anterior neck and lateral arms. Although there is no palpable component to the discoloration, it has a faintly reticular look to it in places. It spares all other locations, such as the axillae, posterior neck, and back. A brief scrub with soap and water fails to have any effect on the discoloration, but a few swipes with an alcohol swab completely restore the skin to its normal, light color, effectively removing the pigmented surface.