User login

Woman with Chest Pain While in Mexico

Answer

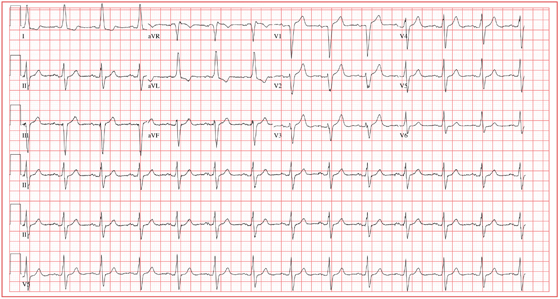

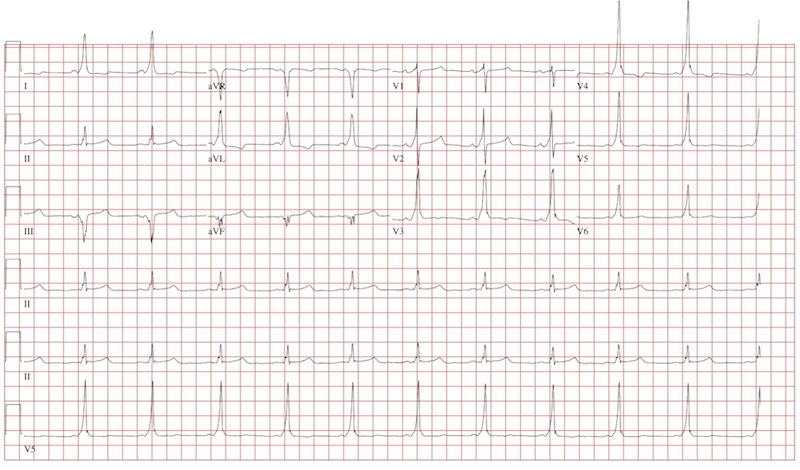

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy with QRS widening and repolarization abnormality, with no evidence of ischemia. Left-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of less than –30° and is determined by examining leads III, aVF, and II. If leads III, aVF, and II are all negative, left-axis deviation is present. In this example, leads III and aVF are negative, while lead II is isoelectric or slightly negative.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is defined by high voltages in the limb leads (R wave in lead I plus S wave in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or in the precordial leads (S wave in V1 plus R wave in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm). The QRS duration, measured from the first deflection of the QRS from baseline to its return to baseline, is normal if ≤ 100 ms (0.10 sec). In this example, the QRS is widened (130 ms) in the absence of a bundle branch block. The delayed depolarization of both ventricles in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy results in delayed repolarization—hence the repolarization abnormality.

This patient underwent cardiac catheterization, which revealed extensive three-vessel coronary artery disease with 99% stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. This case illustrates that severe coronary artery disease can present without ECG evidence of ischemia, particularly in women and in patients with diabetes.

Answer

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy with QRS widening and repolarization abnormality, with no evidence of ischemia. Left-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of less than –30° and is determined by examining leads III, aVF, and II. If leads III, aVF, and II are all negative, left-axis deviation is present. In this example, leads III and aVF are negative, while lead II is isoelectric or slightly negative.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is defined by high voltages in the limb leads (R wave in lead I plus S wave in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or in the precordial leads (S wave in V1 plus R wave in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm). The QRS duration, measured from the first deflection of the QRS from baseline to its return to baseline, is normal if ≤ 100 ms (0.10 sec). In this example, the QRS is widened (130 ms) in the absence of a bundle branch block. The delayed depolarization of both ventricles in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy results in delayed repolarization—hence the repolarization abnormality.

This patient underwent cardiac catheterization, which revealed extensive three-vessel coronary artery disease with 99% stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. This case illustrates that severe coronary artery disease can present without ECG evidence of ischemia, particularly in women and in patients with diabetes.

Answer

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation and left ventricular hypertrophy with QRS widening and repolarization abnormality, with no evidence of ischemia. Left-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of less than –30° and is determined by examining leads III, aVF, and II. If leads III, aVF, and II are all negative, left-axis deviation is present. In this example, leads III and aVF are negative, while lead II is isoelectric or slightly negative.

Left ventricular hypertrophy is defined by high voltages in the limb leads (R wave in lead I plus S wave in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or in the precordial leads (S wave in V1 plus R wave in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm). The QRS duration, measured from the first deflection of the QRS from baseline to its return to baseline, is normal if ≤ 100 ms (0.10 sec). In this example, the QRS is widened (130 ms) in the absence of a bundle branch block. The delayed depolarization of both ventricles in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy results in delayed repolarization—hence the repolarization abnormality.

This patient underwent cardiac catheterization, which revealed extensive three-vessel coronary artery disease with 99% stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. This case illustrates that severe coronary artery disease can present without ECG evidence of ischemia, particularly in women and in patients with diabetes.

For two weeks, a Spanish-speaking woman, 60, has experienced substernal chest pain and shortness of breath. The pain began while she was visiting family in Mexico. She was seen by a local physician, who prescribed a medication that helped but did not relieve the pain completely. She exhausted her supply of this medication shortly after returning from vacation, and her chest pain worsened. The patient’s daughter transported her to your clinic, concerned that her mother may be having a heart attack. According to the daughter, who is interpreting, the pain is described as grade IV/X, intermittent, radiating to the back, and lasting for approximately 10 minutes before subsiding. It is exacerbated with activity, particularly climbing stairs, and resolves when the woman is at rest. She has been awakened by this pain on two occasions. The patient denies fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, or syncope. Medical history is remarkable for hypertension, diabetes, and asthma. She has worked most of her life as a farm worker and as a cook. She does not use alcohol and has a 20–pack-year history of tobacco use. The patient’s medications include aspirin, metformin, pravastatin, telmisartan, verapamil, and a salmeterol inhaler. She is allergic to penicillin. Review of symptoms is remarkable for diarrhea that is resolving and headaches. Physical examination reveals a well-developed, obese woman who is comfortable, alert, and oriented. Her height is 5’3”; weight, 211 lb; blood pressure, 106/40 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and temperature, 99.2°F. The cardiovascular exam reveals a normal rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or extra heart sounds. There are no carotid bruits or peripheral edema. The lungs are remarkable for scattered expiratory wheezes in both bases, with the right greater than the left. The abdomen is large but soft with good bowel tones in all quadrants. There are no palpable bruits or organomegaly. The neurologic exam shows no gross neural deficits. The serum glucose level is 148 mg/dL; hemoglobin, 10.6 g/dL; and troponin, 0.02 ng/mL. All other lab values are within normal limits. An ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, 168 ms; QRS duration, 130 ms; QT/QTc, 384/442 ms; P axis, 29°; R axis, –34°; and T axis, 96°. What is your interpretation of this ECG, and is there any evidence of ongoing ischemia?

Is This Man's Eczema Spreading?

Answer

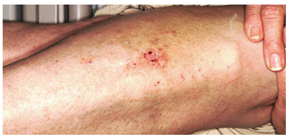

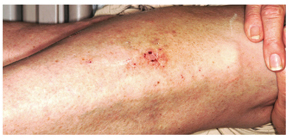

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

A 30-year-old man presents with a pruritic rash that first affected both legs and was followed two weeks later by the appearance of a different but equally pruritic rash on his volar forearms. These rashes have persisted despite the use of OTC topical steroid and antifungal creams, triple-antibiotic ointment, and frequent application of rubbing alcohol. Eczema has been a problem throughout the patient’s life, but since his 20s, it has mostly affected his lower legs. As a result, he has gotten into the habit of scratching, even fantasizing about being able to do so at home. Despite being remarkably atopic, with seasonal allergies and generally sensitive skin, he claims to be otherwise healthy. Examination of the patient’s legs shows heavily lichenified papulosquamous involvement of both legs. There are numerous focal areas of scabbing, redness, and edema, which sharply spare the skin under his socks, thin out, then disappear well below the knees. The patient is even observed scratching these areas as the history is taken, and readily admits doing so several times a day. A fairly dense, symmetrical papulovesicular rash is noted on both volar forearms, with only a few lesions remaining intact because of scratching. Elsewhere, his elbows, knees, scalp, and nail plates are free of significant changes.

Disoriented, Intoxicated, and Hurting All Over

Answer

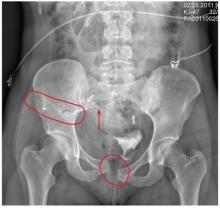

The radiograph demonstrates a mildly displaced fracture of the right iliac wing. In addition, there is moderate diastasis of the pubic symphysis, with the right pubic symphysis being in superior position to the left. Also, a right sacral fracture is present.

The patient was admitted by the trauma service and initially evaluated by the orthopedic trauma team, who planned to take the patient to surgery for subsequent open reduction and internal fixation of these injuries.

Answer

The radiograph demonstrates a mildly displaced fracture of the right iliac wing. In addition, there is moderate diastasis of the pubic symphysis, with the right pubic symphysis being in superior position to the left. Also, a right sacral fracture is present.

The patient was admitted by the trauma service and initially evaluated by the orthopedic trauma team, who planned to take the patient to surgery for subsequent open reduction and internal fixation of these injuries.

Answer

The radiograph demonstrates a mildly displaced fracture of the right iliac wing. In addition, there is moderate diastasis of the pubic symphysis, with the right pubic symphysis being in superior position to the left. Also, a right sacral fracture is present.

The patient was admitted by the trauma service and initially evaluated by the orthopedic trauma team, who planned to take the patient to surgery for subsequent open reduction and internal fixation of these injuries.

A woman, approximately 30 years old, is airlifted to your facility after being “found in a ditch,” presumably as a result of a motor vehicle collision. Details are sketchy. Upon arrival at your facility, she is awake, crying, and complaining of “hurting all over.” She appears to be intoxicated. She is able to give you her name, but not much else in the way of history. Primary survey shows her vital signs to be: blood pressure, 105/75 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. She is afebrile. She has a superficial scalp laceration but no other obvious injuries. You obtain preliminary portable radiographs of the pelvis. What is your impression?

Unrestrained Passenger Injured in Car Accident

ANSWER

There is a cortical irregularity at the medial margin of the left iliac bone at the level of the acetabulum, strongly suggestive of a fracture. In addition, there may be a nondisplaced fracture within the superior/inferior rami on the left.

CT was recommended to further define these areas (and was already pending to evaluate the patient’s abdomen). Fortunately, there were no fractures within the hip joint, just the nondisplaced rami fracture.

ANSWER

There is a cortical irregularity at the medial margin of the left iliac bone at the level of the acetabulum, strongly suggestive of a fracture. In addition, there may be a nondisplaced fracture within the superior/inferior rami on the left.

CT was recommended to further define these areas (and was already pending to evaluate the patient’s abdomen). Fortunately, there were no fractures within the hip joint, just the nondisplaced rami fracture.

ANSWER

There is a cortical irregularity at the medial margin of the left iliac bone at the level of the acetabulum, strongly suggestive of a fracture. In addition, there may be a nondisplaced fracture within the superior/inferior rami on the left.

CT was recommended to further define these areas (and was already pending to evaluate the patient’s abdomen). Fortunately, there were no fractures within the hip joint, just the nondisplaced rami fracture.

A 19-year-old man is transferred to your facility for injuries he sustained in a motor vehicle collision. He was an unrestrained passenger in a vehicle that went out of control and left the road. At the outside facility, he was found to have a chest injury and a pneumothorax, resulting in his transfer for tertiary level care. On arrival, he is complaining of some chest wall pain, but also states that his hips—especially the left one—are causing quite a bit of discomfort. His medical history is unremarkable except for sickle cell trait. Primary survey reveals stable vital signs and no obvious injury. On closer examination, with stress on his pelvis, he does complain of localized pain on the left side. Radiograph of the pelvis is obtained. What is your impression?

Basketball Player with Continuous Palpitations

ANSWER

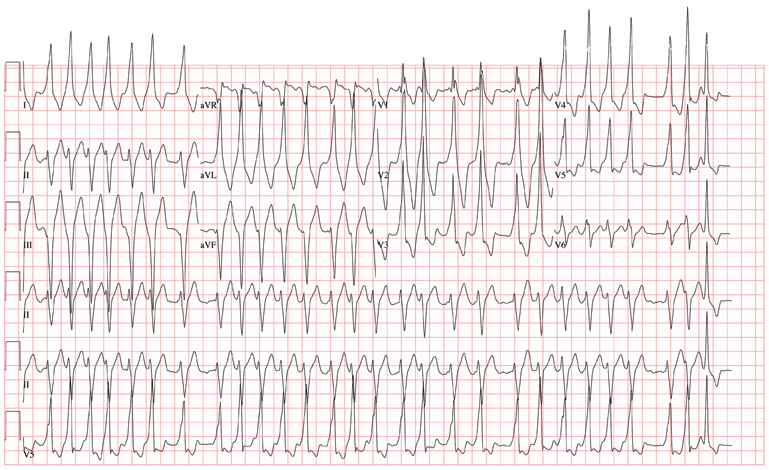

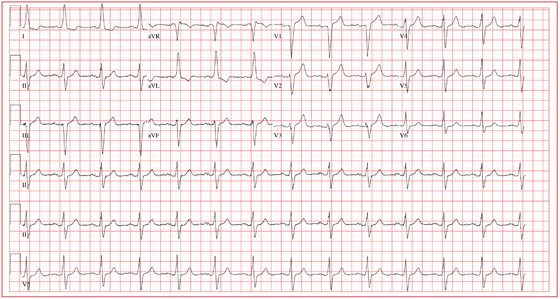

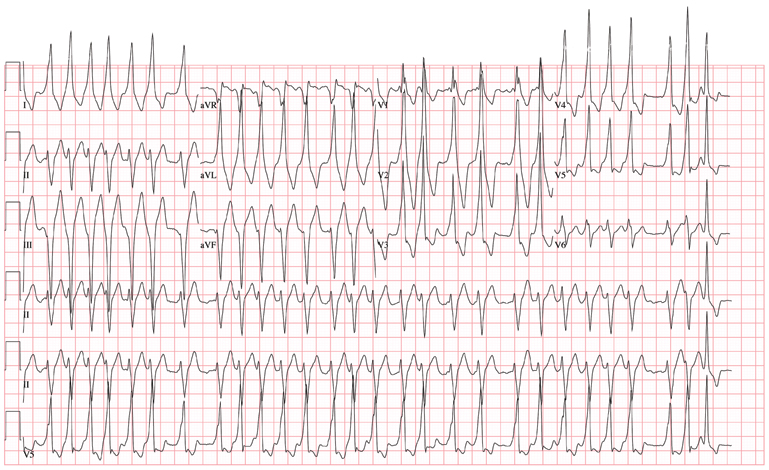

The ECG demonstrates atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response with aberrantly conducted complexes, left-axis deviation, and marked T-wave abnormality. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of WPW with antegrade conduction down the accessory pathway can be life threatening. Unlike the AV node, which can decrementally slow rapid conduction to the ventricle, the accessory pathway can conduct atrial fibrillation impulses into the ventricle in a 1:1 ratio; if uncontrolled, this can result in ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation.

The patient was started on a procainamide drip and converted to normal sinus rhythm. He underwent an electrophysiology study, which demonstrated a single accessory pathway capable of conducting at rates of 250 beats/min located in the lateral wall of the left atrium. It was successfully ablated, resulting in normalization of his ECG.

ANSWER

The ECG demonstrates atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response with aberrantly conducted complexes, left-axis deviation, and marked T-wave abnormality. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of WPW with antegrade conduction down the accessory pathway can be life threatening. Unlike the AV node, which can decrementally slow rapid conduction to the ventricle, the accessory pathway can conduct atrial fibrillation impulses into the ventricle in a 1:1 ratio; if uncontrolled, this can result in ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation.

The patient was started on a procainamide drip and converted to normal sinus rhythm. He underwent an electrophysiology study, which demonstrated a single accessory pathway capable of conducting at rates of 250 beats/min located in the lateral wall of the left atrium. It was successfully ablated, resulting in normalization of his ECG.

ANSWER

The ECG demonstrates atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response with aberrantly conducted complexes, left-axis deviation, and marked T-wave abnormality. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of WPW with antegrade conduction down the accessory pathway can be life threatening. Unlike the AV node, which can decrementally slow rapid conduction to the ventricle, the accessory pathway can conduct atrial fibrillation impulses into the ventricle in a 1:1 ratio; if uncontrolled, this can result in ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular fibrillation.

The patient was started on a procainamide drip and converted to normal sinus rhythm. He underwent an electrophysiology study, which demonstrated a single accessory pathway capable of conducting at rates of 250 beats/min located in the lateral wall of the left atrium. It was successfully ablated, resulting in normalization of his ECG.

The charge nurse in the emergency department (ED) calls to tell you that one of your patients, a 19-year-old man, has just presented with a three-hour history of continuous palpitations. She reports the patient’s pulse as 170 beats/min and adds that although he is awake and stable, he is complaining of chest discomfort and lightheadedness. The tachycardia began abruptly while the patient was playing basketball. Witnesses said he did not lose consciousness but did sit down, complaining of dizziness. The patient admits he thought he “was going to pass out” when he sat up. As you review the patient’s chart, you recall seeing him for palpitations approximately six months ago, at which time an ECG showed Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome with a left-sided accessory pathway. His history is remarkable for palpitations beginning at age 14, with two episodes of near-syncope. None of his episodes of palpitations has lasted as long as the current one, however. Medical history is remarkable for a tonsillectomy at age 7. Family history is positive for coronary artery disease and diabetes. The patient takes no medications and has no known drug allergies. He is a college student, drinks a six-pack of beer on weekends despite being under age, and tried marijuana once. He denies any other use of illegal, illicit, or performance-enhancing drugs. The review of systems is noncontributory. The physical exam reveals a thin, anxious male. His blood pressure is 98/66 mm Hg; pulse, 170 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; temperature, 99°F; and O2 saturation, 98% on 2L of oxygen. There is no jugular venous distention, and carotid upstrokes are rapid and brisk. The chest is clear to auscultation bilaterally with good excursion. The cardiac exam reveals a rapid, regular rate with no murmurs, gallops, or rubs. There are no extra heart sounds. The abdominal, peripheral, and neurologic exams are intact without focal signs. On arrival in the ED, you are handed an ECG, which shows: a ventricular rate of 174 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 164 ms; QT/QTc interval, 302/513 ms; no P axis; R axis, –46°; and T axis, 118°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Infant with Unrelenting Rash

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

A 5-month-old baby is brought for urgent evaluation of a rash that has persisted for more than a month, despite the use of numerous OTC and prescription creams. The latter include clotrimazole and miconazole, neither of which helped much. This morning, the parents started applying starch powder and nystatin cream to the site. It is difficult to tell if the child is suffering from the condition, but the parents and referring pediatrician are certainly worried. The child is otherwise healthy, with appropriate weight increases, and still nursing, taking no solid foods. There is no history of persistent diarrhea and no family history of atopy. On examination, the child’s rash is an impressive red with an erosive center. It covers the entire anterior neck, but is especially accented in the anterior fold of the neck skin. Very little, if any, edema is present, and there is no tenderness elicited on palpation. The site is still covered with excess powder from this morning’s treatment attempt. A survey of the scalp, the diaper area, the mouth, and elsewhere on the face reveals no other areas of rash. The child’s development appears quite normal in all respects.

Woman with Severe Ankle Pain After Fall

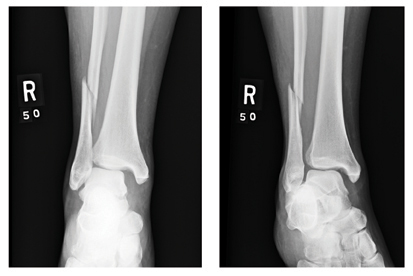

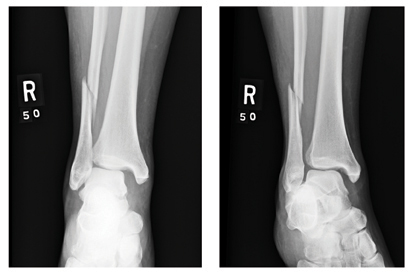

ANSWER

There is an obvious oblique fracture of the distal fibula. In addition, there is widening of the mortise medially—usually suggestive of a ligament injury. Also, there may be a small avulsion at the inferior aspect of the medial malleolus.

The patient was admitted with a plan for her to undergo an open reduction and internal fixation procedure.

ANSWER

There is an obvious oblique fracture of the distal fibula. In addition, there is widening of the mortise medially—usually suggestive of a ligament injury. Also, there may be a small avulsion at the inferior aspect of the medial malleolus.

The patient was admitted with a plan for her to undergo an open reduction and internal fixation procedure.

ANSWER

There is an obvious oblique fracture of the distal fibula. In addition, there is widening of the mortise medially—usually suggestive of a ligament injury. Also, there may be a small avulsion at the inferior aspect of the medial malleolus.

The patient was admitted with a plan for her to undergo an open reduction and internal fixation procedure.

A 39-year-old woman presents to your emergency department complaining of right ankle pain following an injury last night. She states that she got out of bed during the night, somehow misstepped, and fell to the floor. She is unable to bear weight on the ankle and is experiencing severe pain. Her medical history is significant for being one month status post Chiari decompression. She also has a history of bipolar disorder. Examination of the patient’s right ankle shows it to be moderately swollen with some bruising laterally. The patient has limited flexion and extension, and her ankle is extremely tender to palpation. Her distal pulses and her sensation are intact. Radiographs of the right ankle are shown. What is your impression?

Abrupt Onset Palpitations

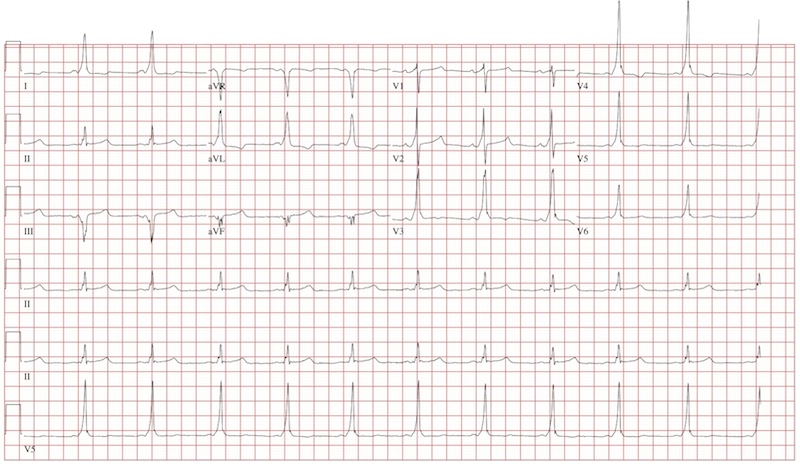

ANSWER

The ECG reveals a short PR interval (< 120 ms), a slurred upstroke (delta wave) of the initiation of the QRS complex indicating ventricular preexcitation, a broad QRS (> 110 ms) as a result of the delta wave, and secondary ST- and T-wave changes consistent with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. The delta wave is an indicator of an electrical impulse that bypasses normal AV nodal conduction through one or more accessory pathways that allow direct antegrade conduction between the atria and ventricles.

If the delta wave is positive in lead V1, the accessory pathway is located between the left atrium and left ventricle. If the delta wave is negative in aVF, as indicated in this ECG, the accessory pathway can be further located to the lateral wall of the left atrium. This localization aids in estimating the location of the accessory pathway prior to electrophysiology study and ablation.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals a short PR interval (< 120 ms), a slurred upstroke (delta wave) of the initiation of the QRS complex indicating ventricular preexcitation, a broad QRS (> 110 ms) as a result of the delta wave, and secondary ST- and T-wave changes consistent with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. The delta wave is an indicator of an electrical impulse that bypasses normal AV nodal conduction through one or more accessory pathways that allow direct antegrade conduction between the atria and ventricles.

If the delta wave is positive in lead V1, the accessory pathway is located between the left atrium and left ventricle. If the delta wave is negative in aVF, as indicated in this ECG, the accessory pathway can be further located to the lateral wall of the left atrium. This localization aids in estimating the location of the accessory pathway prior to electrophysiology study and ablation.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals a short PR interval (< 120 ms), a slurred upstroke (delta wave) of the initiation of the QRS complex indicating ventricular preexcitation, a broad QRS (> 110 ms) as a result of the delta wave, and secondary ST- and T-wave changes consistent with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. The delta wave is an indicator of an electrical impulse that bypasses normal AV nodal conduction through one or more accessory pathways that allow direct antegrade conduction between the atria and ventricles.

If the delta wave is positive in lead V1, the accessory pathway is located between the left atrium and left ventricle. If the delta wave is negative in aVF, as indicated in this ECG, the accessory pathway can be further located to the lateral wall of the left atrium. This localization aids in estimating the location of the accessory pathway prior to electrophysiology study and ablation.

An 18-year-old man has palpitations that occur with variable frequency: sometimes several times per day, and often weeks without an occurrence. The onset is typically abrupt, lasting a few seconds to several minutes before abruptly terminating. He describes them as a “rapid fluttering” sensation in his chest with a “full feeling” in his throat. Associated symptoms include lightheadedness and chest discomfort. He denies chest pain. He had an episode of near-syncope at age 14 and another approximately four weeks ago; the latter prompted him to schedule an appointment in your clinic. He has not been ill recently and has no history to suggest hypovolemia or anemia as a contributing factor for his recent episode of near-syncope. Medical history is unremarkable, with the exception of tonsillectomy at age 7. He is not taking any medications and has no known drug allergies. Family history is positive for coronary artery disease in his father, which required revascularization at age 62, and diabetes in a grandparent. Social history reveals he is a full-time undergraduate student at a local junior college. He drinks approximately one six-pack of beer on weekends despite being under age, but denies use of illegal, illicit, or performance-enhancing drugs. The review of systems is noncontributory. The physical examination reveals a thin, healthy-appearing male in no distress. His blood pressure is 104/62 mm Hg; pulse, 66 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min. The patient is afebrile. The chest is clear to auscultation bilaterally with good excursion. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, gallops, or extra heart sounds. There is no jugular venous distention or peripheral edema. The remainder of the physical exam shows no abnormalities or deficits. Despite the “normal” physical, you are concerned about the patient’s history of frequent palpitations and two previous episodes of near-syncope. You order an ECG, the results of which show: a ventricular rate of 66 beats/min; PR interval, 116 ms; QRS duration, 142 ms; QT/QTc interval, 456/478 ms; P axis, 0°; R axis, –7°; and T axis, 105°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

"Athlete's Foot" That Won't Go Away

ANSWER

The one thing least likely to help is changing to white socks (choice “a”), since there is no reason to believe sock color has any effect, one way or the other, on the problem. There are numerous myths in society regarding athlete’s foot; these will be addressed in the discussion section.

When treatment appears to fail, it is usually a good idea to consider other diagnostic possibilities (choice “b”). In this case, these might have included bacterial or yeast infection, among others.

In stubborn or severe cases of tinea pedis, a 10- to 14-day course of terbinafine (choice “c”) is an acceptable treatment option, with only a modest risk of untoward effects. Continued topical application of terbinafine or other prescription-strength antifungal cream will probably be necessary to prevent flares.

Patient and family education (choice “d”) is arguably the single most important step to take in such cases, for reasons that will be delineated in the discussion.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates several aspects of this diagnosis, which is estimated to affect up to 70% of the general population at one time or another in their lives. Our patient’s age, the presentation of the condition—very specifically affecting the webspace between the fourth and fifth toes (between the third and fourth toes far less commonly)—and the presence of chronic itching and maceration are all quite typical of this most common form of tinea pedis.

But just as typical is the persistent nature of the problem: Despite treatment, it often recurs, much to the patient’s distress. The two creams the patient had tried were among the least effective choices (massive advertising campaigns notwithstanding). Eventually, the patient’s immune system will likely fend off this infection; better bathing habits, less occlusive footwear, and less sweating can help. “Catching” this form of tinea pedis is related far more to these favorable conditions and to individual susceptibility than it is to the inevitable exposure to this ubiquitous dermatophyte.

Surprisingly, the first reports of this diagnosis in the United States were not made until the 1920s. The suspicion was that the organism, Trichophyton rubrum, had spread from very limited endemic areas to the rest of the world as a result of the massive movement of soldiers and civilian populations during and after WWI. The general increase in more occlusive forms of footwear was also thought to be a contributing factor.

Many myths sprang up over time regarding this condition. The “white sock” myth was so prevalent that it was probably responsible for two generations’ predominant choice of sock color. The use of white socks was also mistakenly thought to ward off foot odor, which in turn was thought to be caused by fungi.

Regarding the supposed contagious nature of the interdigital form of tinea pedis: Many a married couple has coexisted for decades without the husband “giving” it to the spouse, who is far less likely to represent a favorable host.

Three other forms of tinea pedis eventually evolved, including the hyperkeratotic type (also known as “moccasin variety” tinea pedis), which presents with a scaly, asymptomatic chronic rash around the rim of the feet; the inflammatory type, which presents with the acute appearance of vesicles and pustules on the soles of the feet, is highly pruritic, and almost always has a zoophilic source (cats being the most common); and the far less common ulcerative type, which presents with extensive vesicles, blisters, and erosions, is most often seen on the feet of patients with severe diabetes living in hot, humid conditions, and is usually from zoophilic sources as well.

When reasonable treatment fails, or KOH is negative, or the diagnosis is in doubt for any reason, consideration must be given to other potential explanations. For example, a similar condition can be caused by gram-negative organisms such as Proteus or Pseudomonas. A gram-positive organism called Corynebacterium minitissimum can eventuate in a chronic interdigital rash. Staph and strep can gain entry to the skin through preexisting, tinea pedis–caused breaks in the skin and eventuate in impressive cases of cellulitis, sometimes affecting the entire leg. Contact dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis also belong in the differential.

Our patient was successfully treated with OTC terbinafine cream.

ANSWER

The one thing least likely to help is changing to white socks (choice “a”), since there is no reason to believe sock color has any effect, one way or the other, on the problem. There are numerous myths in society regarding athlete’s foot; these will be addressed in the discussion section.

When treatment appears to fail, it is usually a good idea to consider other diagnostic possibilities (choice “b”). In this case, these might have included bacterial or yeast infection, among others.

In stubborn or severe cases of tinea pedis, a 10- to 14-day course of terbinafine (choice “c”) is an acceptable treatment option, with only a modest risk of untoward effects. Continued topical application of terbinafine or other prescription-strength antifungal cream will probably be necessary to prevent flares.

Patient and family education (choice “d”) is arguably the single most important step to take in such cases, for reasons that will be delineated in the discussion.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates several aspects of this diagnosis, which is estimated to affect up to 70% of the general population at one time or another in their lives. Our patient’s age, the presentation of the condition—very specifically affecting the webspace between the fourth and fifth toes (between the third and fourth toes far less commonly)—and the presence of chronic itching and maceration are all quite typical of this most common form of tinea pedis.

But just as typical is the persistent nature of the problem: Despite treatment, it often recurs, much to the patient’s distress. The two creams the patient had tried were among the least effective choices (massive advertising campaigns notwithstanding). Eventually, the patient’s immune system will likely fend off this infection; better bathing habits, less occlusive footwear, and less sweating can help. “Catching” this form of tinea pedis is related far more to these favorable conditions and to individual susceptibility than it is to the inevitable exposure to this ubiquitous dermatophyte.

Surprisingly, the first reports of this diagnosis in the United States were not made until the 1920s. The suspicion was that the organism, Trichophyton rubrum, had spread from very limited endemic areas to the rest of the world as a result of the massive movement of soldiers and civilian populations during and after WWI. The general increase in more occlusive forms of footwear was also thought to be a contributing factor.

Many myths sprang up over time regarding this condition. The “white sock” myth was so prevalent that it was probably responsible for two generations’ predominant choice of sock color. The use of white socks was also mistakenly thought to ward off foot odor, which in turn was thought to be caused by fungi.

Regarding the supposed contagious nature of the interdigital form of tinea pedis: Many a married couple has coexisted for decades without the husband “giving” it to the spouse, who is far less likely to represent a favorable host.

Three other forms of tinea pedis eventually evolved, including the hyperkeratotic type (also known as “moccasin variety” tinea pedis), which presents with a scaly, asymptomatic chronic rash around the rim of the feet; the inflammatory type, which presents with the acute appearance of vesicles and pustules on the soles of the feet, is highly pruritic, and almost always has a zoophilic source (cats being the most common); and the far less common ulcerative type, which presents with extensive vesicles, blisters, and erosions, is most often seen on the feet of patients with severe diabetes living in hot, humid conditions, and is usually from zoophilic sources as well.

When reasonable treatment fails, or KOH is negative, or the diagnosis is in doubt for any reason, consideration must be given to other potential explanations. For example, a similar condition can be caused by gram-negative organisms such as Proteus or Pseudomonas. A gram-positive organism called Corynebacterium minitissimum can eventuate in a chronic interdigital rash. Staph and strep can gain entry to the skin through preexisting, tinea pedis–caused breaks in the skin and eventuate in impressive cases of cellulitis, sometimes affecting the entire leg. Contact dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis also belong in the differential.

Our patient was successfully treated with OTC terbinafine cream.

ANSWER

The one thing least likely to help is changing to white socks (choice “a”), since there is no reason to believe sock color has any effect, one way or the other, on the problem. There are numerous myths in society regarding athlete’s foot; these will be addressed in the discussion section.

When treatment appears to fail, it is usually a good idea to consider other diagnostic possibilities (choice “b”). In this case, these might have included bacterial or yeast infection, among others.

In stubborn or severe cases of tinea pedis, a 10- to 14-day course of terbinafine (choice “c”) is an acceptable treatment option, with only a modest risk of untoward effects. Continued topical application of terbinafine or other prescription-strength antifungal cream will probably be necessary to prevent flares.

Patient and family education (choice “d”) is arguably the single most important step to take in such cases, for reasons that will be delineated in the discussion.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates several aspects of this diagnosis, which is estimated to affect up to 70% of the general population at one time or another in their lives. Our patient’s age, the presentation of the condition—very specifically affecting the webspace between the fourth and fifth toes (between the third and fourth toes far less commonly)—and the presence of chronic itching and maceration are all quite typical of this most common form of tinea pedis.

But just as typical is the persistent nature of the problem: Despite treatment, it often recurs, much to the patient’s distress. The two creams the patient had tried were among the least effective choices (massive advertising campaigns notwithstanding). Eventually, the patient’s immune system will likely fend off this infection; better bathing habits, less occlusive footwear, and less sweating can help. “Catching” this form of tinea pedis is related far more to these favorable conditions and to individual susceptibility than it is to the inevitable exposure to this ubiquitous dermatophyte.

Surprisingly, the first reports of this diagnosis in the United States were not made until the 1920s. The suspicion was that the organism, Trichophyton rubrum, had spread from very limited endemic areas to the rest of the world as a result of the massive movement of soldiers and civilian populations during and after WWI. The general increase in more occlusive forms of footwear was also thought to be a contributing factor.

Many myths sprang up over time regarding this condition. The “white sock” myth was so prevalent that it was probably responsible for two generations’ predominant choice of sock color. The use of white socks was also mistakenly thought to ward off foot odor, which in turn was thought to be caused by fungi.

Regarding the supposed contagious nature of the interdigital form of tinea pedis: Many a married couple has coexisted for decades without the husband “giving” it to the spouse, who is far less likely to represent a favorable host.

Three other forms of tinea pedis eventually evolved, including the hyperkeratotic type (also known as “moccasin variety” tinea pedis), which presents with a scaly, asymptomatic chronic rash around the rim of the feet; the inflammatory type, which presents with the acute appearance of vesicles and pustules on the soles of the feet, is highly pruritic, and almost always has a zoophilic source (cats being the most common); and the far less common ulcerative type, which presents with extensive vesicles, blisters, and erosions, is most often seen on the feet of patients with severe diabetes living in hot, humid conditions, and is usually from zoophilic sources as well.

When reasonable treatment fails, or KOH is negative, or the diagnosis is in doubt for any reason, consideration must be given to other potential explanations. For example, a similar condition can be caused by gram-negative organisms such as Proteus or Pseudomonas. A gram-positive organism called Corynebacterium minitissimum can eventuate in a chronic interdigital rash. Staph and strep can gain entry to the skin through preexisting, tinea pedis–caused breaks in the skin and eventuate in impressive cases of cellulitis, sometimes affecting the entire leg. Contact dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis also belong in the differential.

Our patient was successfully treated with OTC terbinafine cream.

An 18-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of bilateral “athlete’s foot” present for months despite the application of tolnaftate and clotrimazole creams. These both relieved itching, but the problem quickly returned, especially when the weather turned warm. Besides objecting to his foot odor, the patient’s family also worries that his condition is contagious—even though the man’s father already has occasional athlete’s foot. Aside from mild seasonal allergies, the patient is reportedly in excellent health. He has never had any significant skin diseases and is not taking any medications regularly. Inspection of the problem reveals marked maceration bilaterally between the fourth and fifth toes, under which is faint erythema. A KOH prep of the readily obtained material is examined microscopically under the usual 10x magnification, and numerous hyphal (fungal) elements are positively identified, in effect confirming the diagnosis of tinea pedis.

Shoulder Pain in Man Hospitalized for Brain Mass

ANSWER

There is no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. However, there is a focal lytic lesion within the scapula. Given a presumed history of renal cell carcinoma, this finding is strongly suspicious for metastasis and must be worked up.

ANSWER

There is no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. However, there is a focal lytic lesion within the scapula. Given a presumed history of renal cell carcinoma, this finding is strongly suspicious for metastasis and must be worked up.

ANSWER

There is no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. However, there is a focal lytic lesion within the scapula. Given a presumed history of renal cell carcinoma, this finding is strongly suspicious for metastasis and must be worked up.

A 53-year-old man is admitted with a possible brain mass. He gives a two-week history of headaches and intermittent left-sided weakness. Outpatient CT of the head showed a possible right frontal mass. His medical history is significant for mild hypertension and for the removal of one kidney seven years ago, due to cancer. He states he received no adjuvant therapy. When you check on the patient today, he mentions that his left shoulder has been bothering him for some time. He denies any injury to it. He states he has decreased range of motion and pain with range of motion. You order a radiograph of the shoulder (shown). What is your impression?