User login

Deoxycholic Acid for Dercum Disease: Repurposing a Cosmetic Agent to Treat a Rare Disease

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

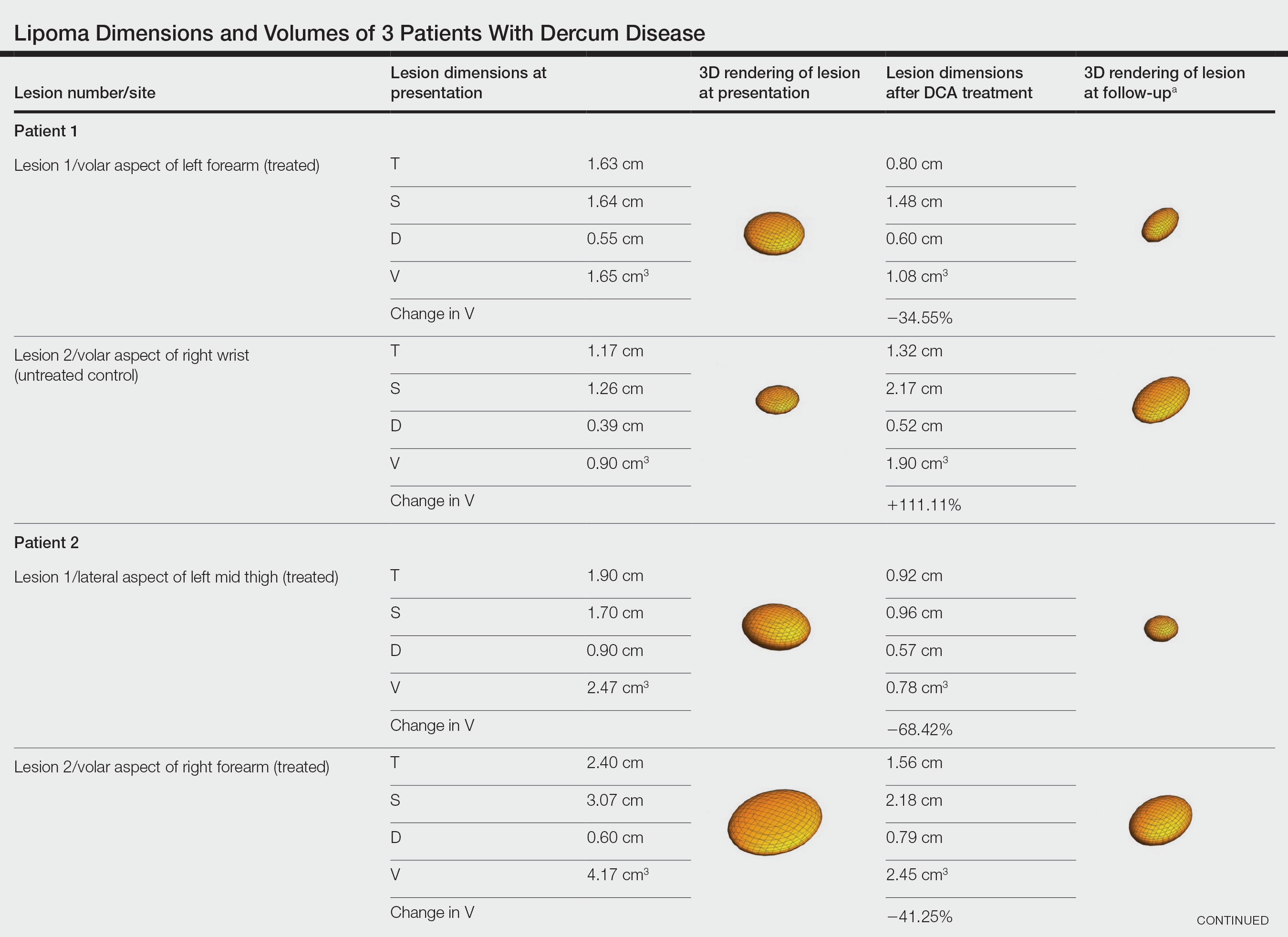

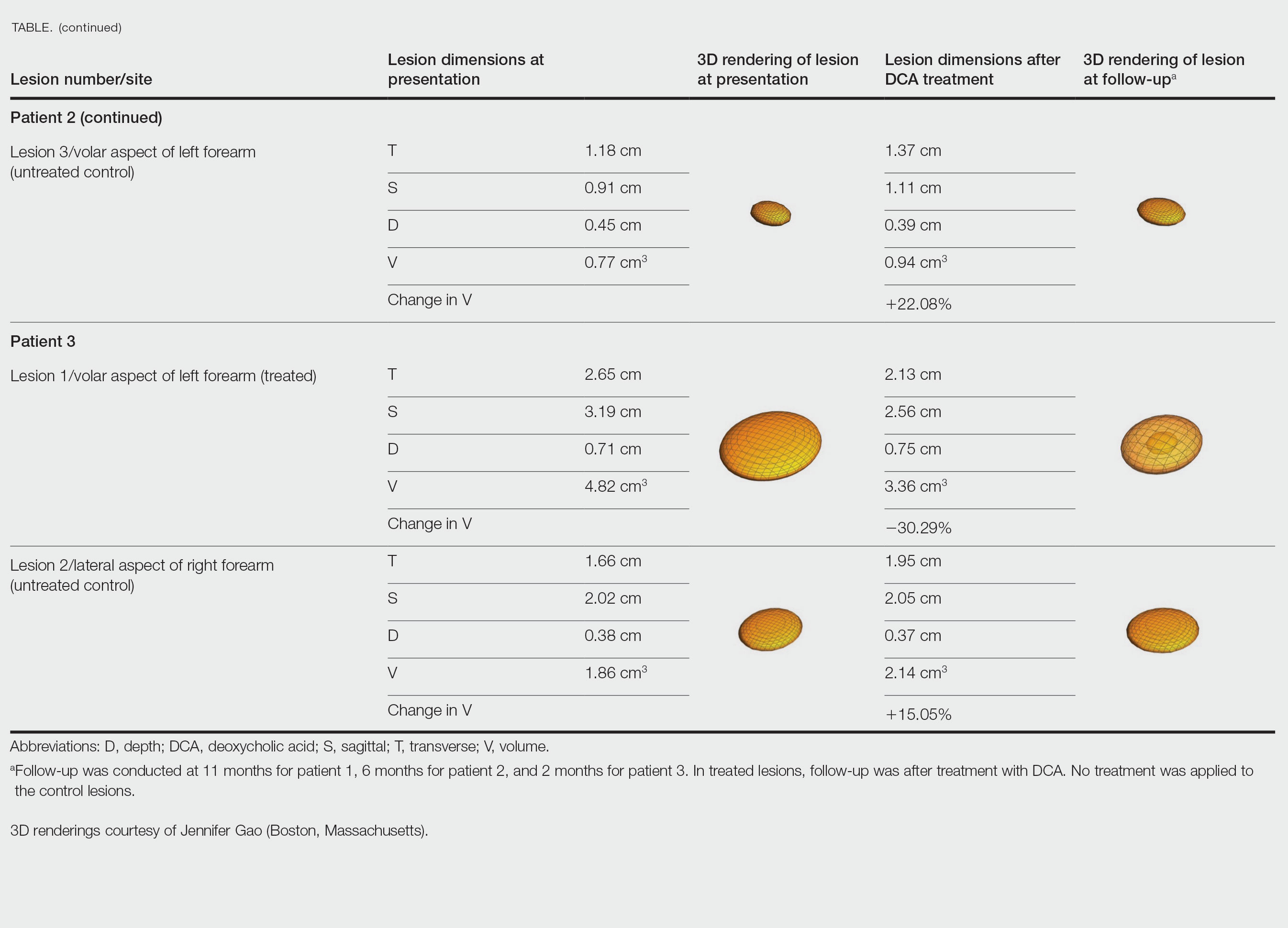

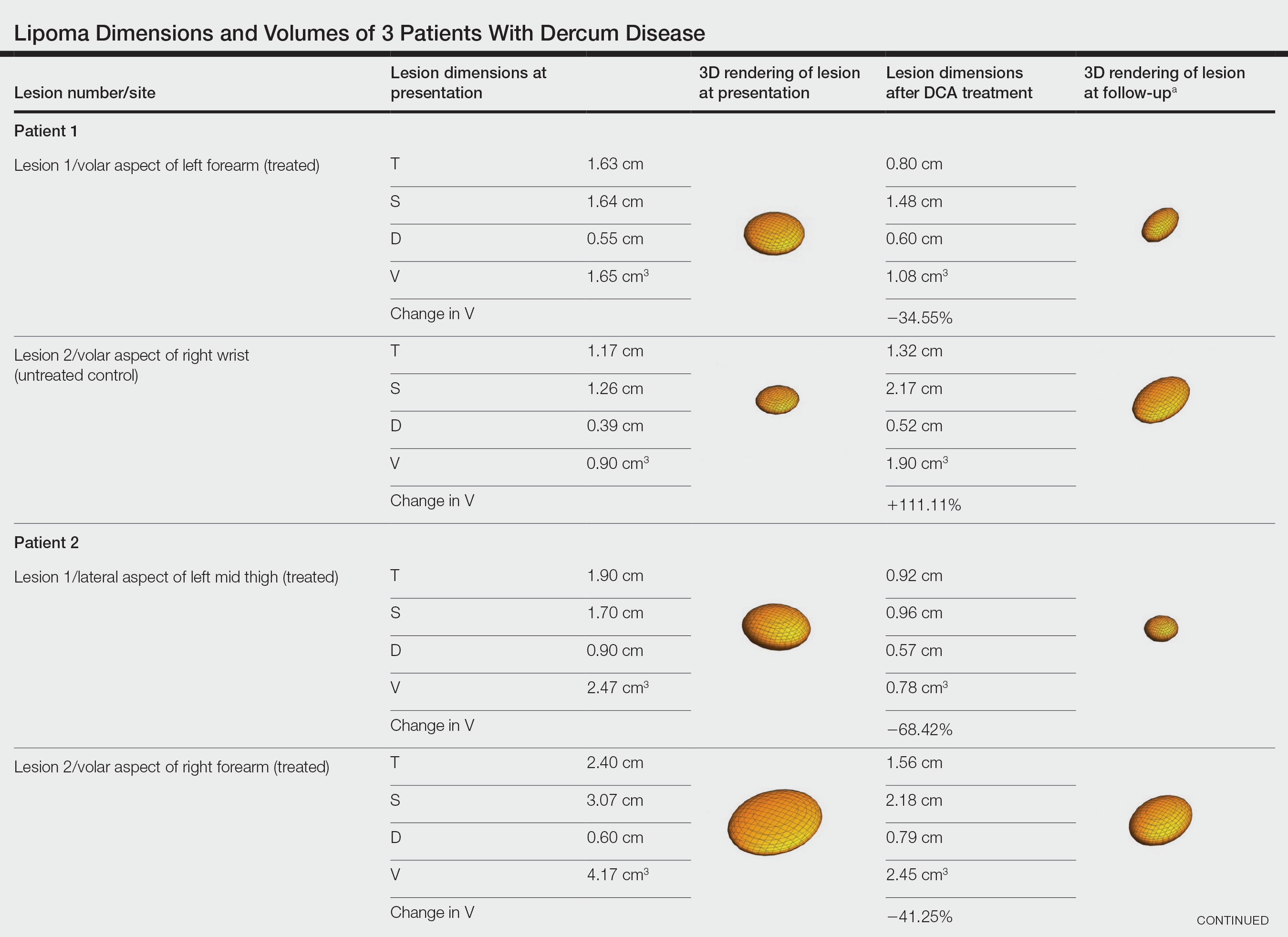

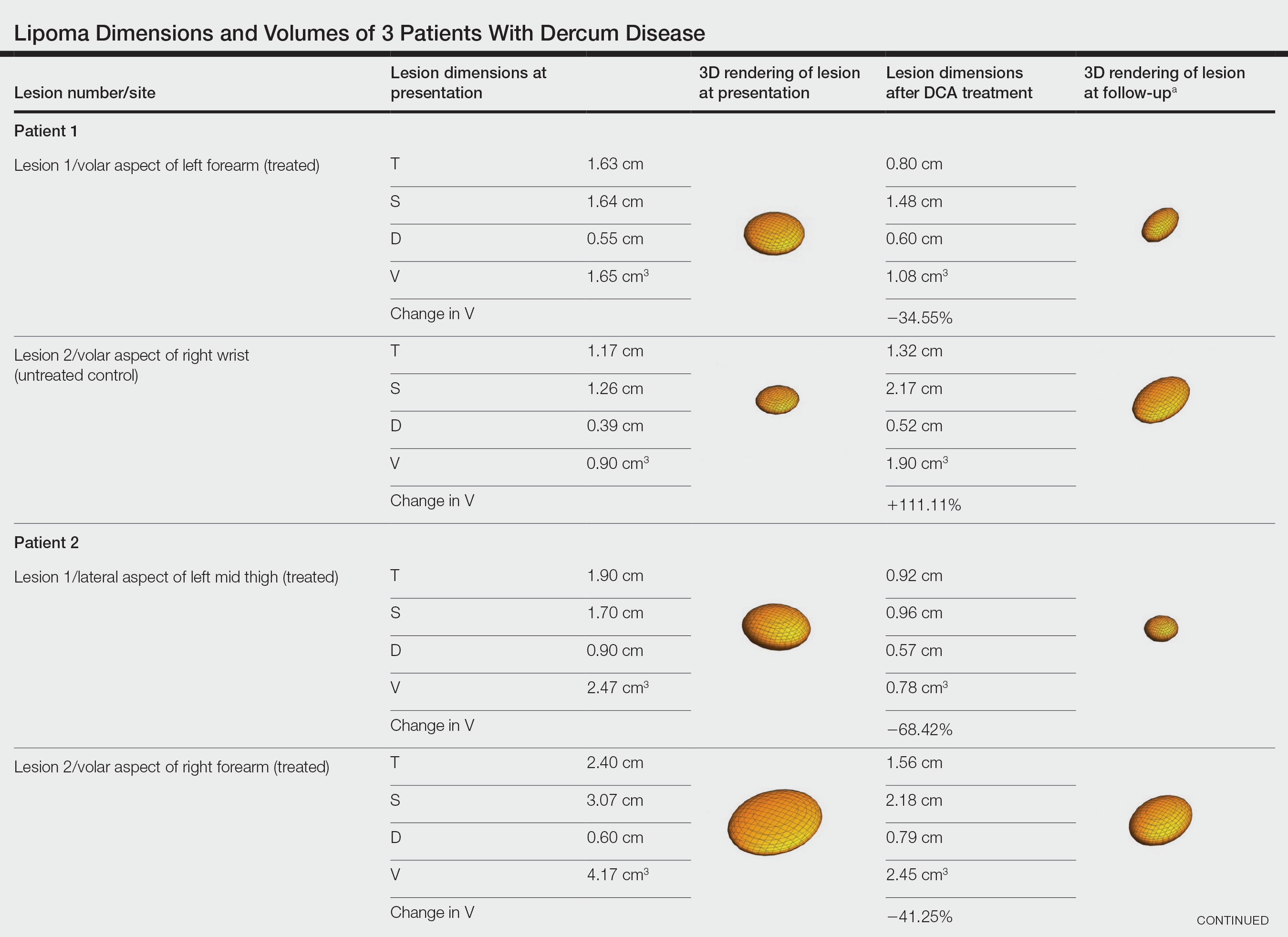

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

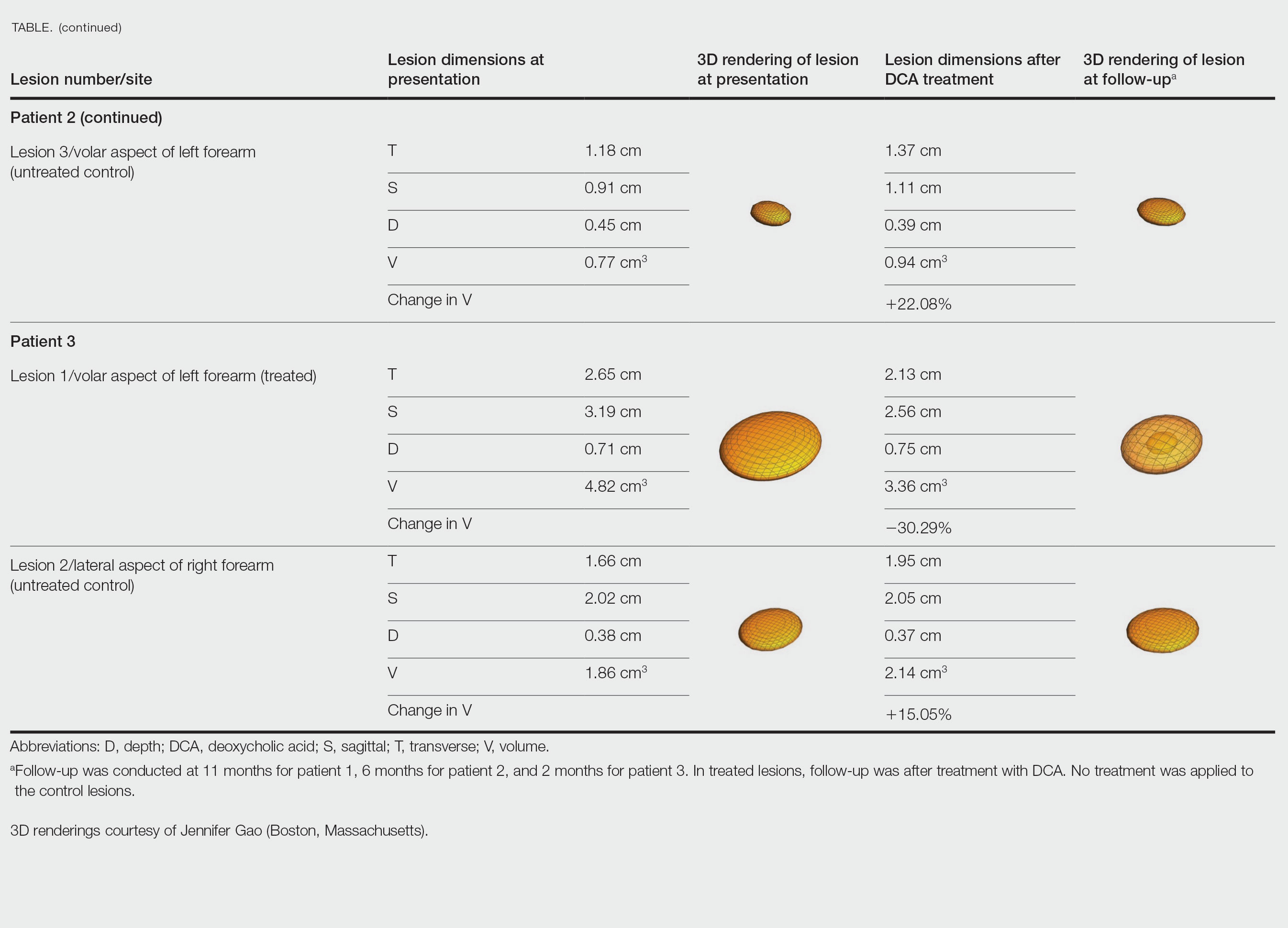

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

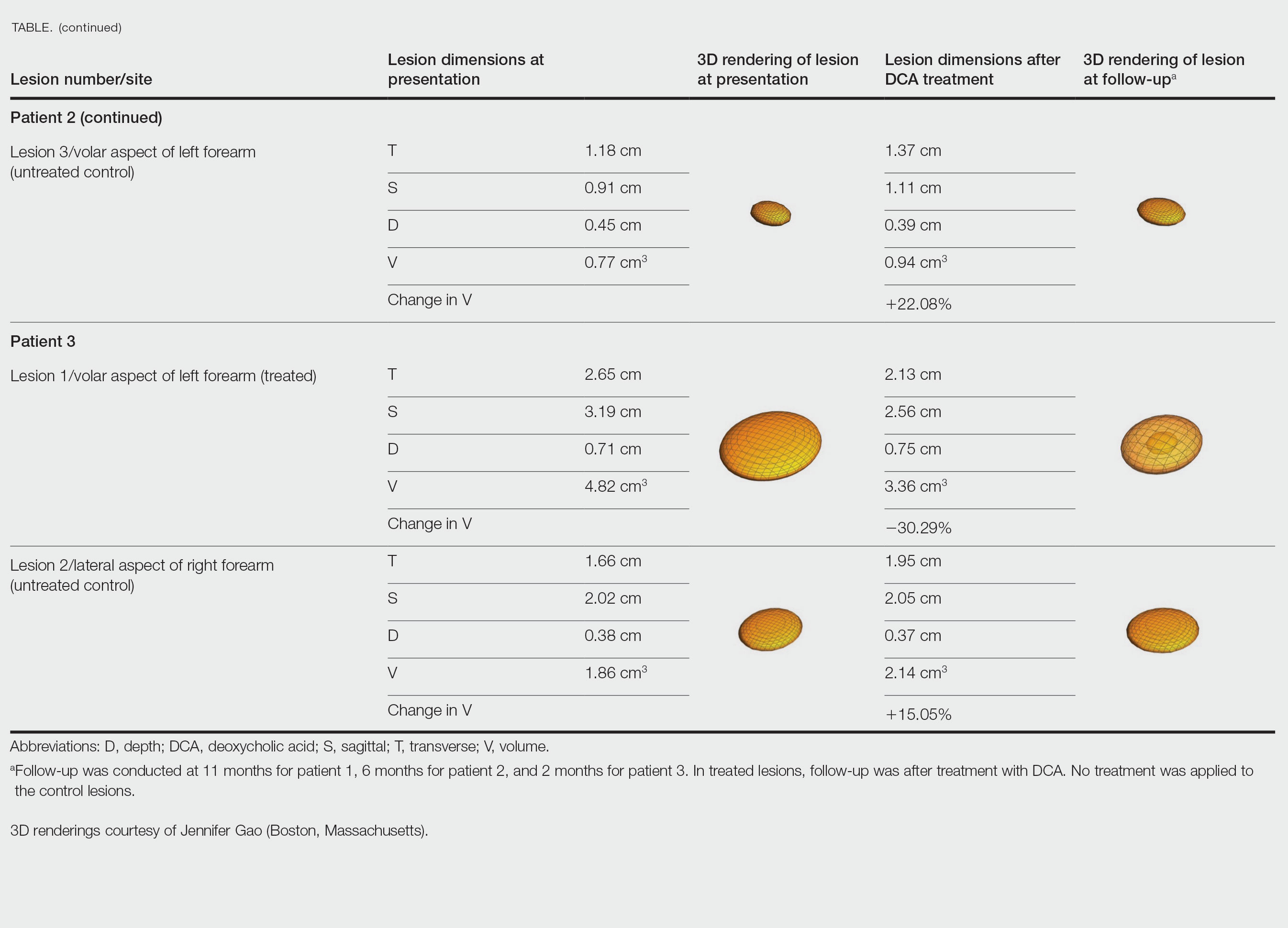

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9

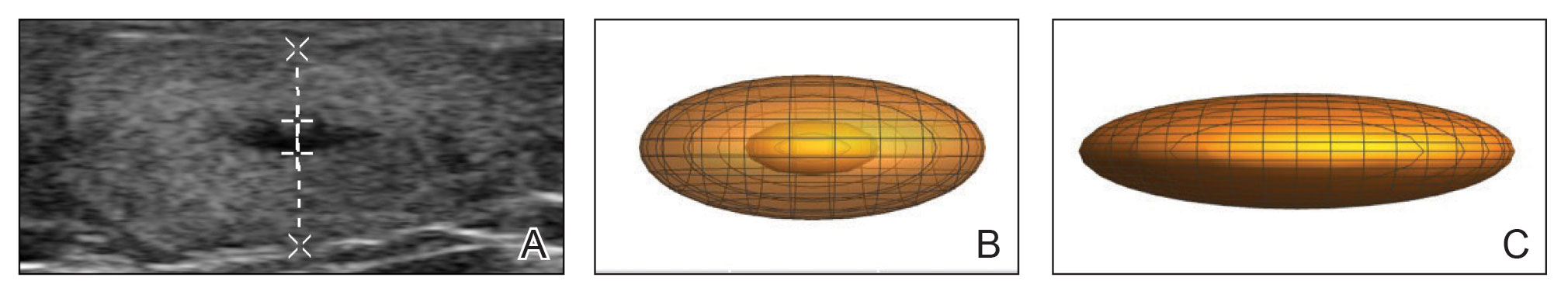

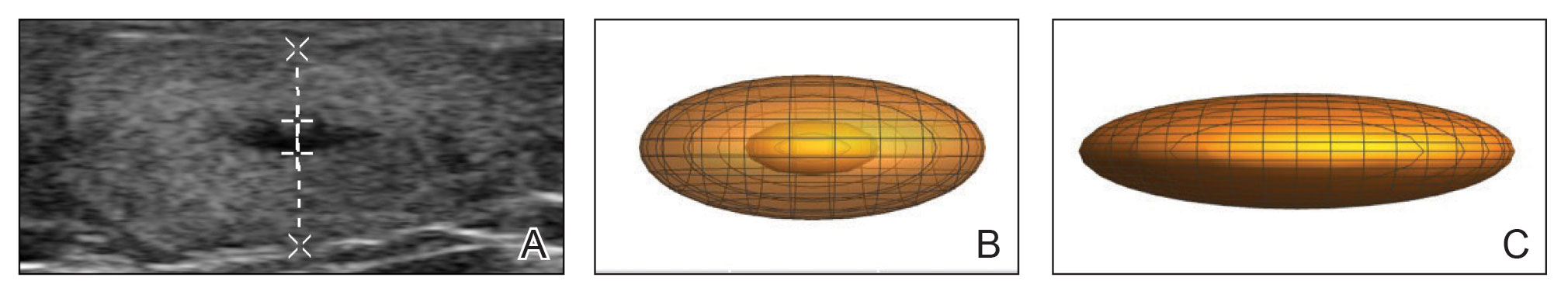

We present 3 patients who requested treatment for numerous painful lipomas. Given the extent of their disease, surgical options were not feasible, and the patients opted to try a nonsurgical alternative. In each case, the painful lipomas that were chosen for treatment were injected with 2 mL of DCA. Injection-associated symptoms included swelling, tenderness, discoloration, and induration, which resolved over a period of months. Patient 1 had a treated lipoma that reduced in volume by approximately 35%, while the control continued to grow and doubled in volume. In patient 2, the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the mid thigh reduced in volume by almost 70%, and the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the right forearm reduced in volume by more than 40%, while the control grew by more than 20%. In patient 3, the volume of the treated lipoma decreased by 30%, and the control increased by 15%. The follow-up interval was shortest in patient 3—2 months as opposed to 11 months and 6 months for patients 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, more progress may be seen in patient 3 with more time. Interestingly, a change in shape of the lipoma was noted in patient 3 (Figure)—an increase in its depth while the center became anechoic, which is a sign of hollowing in the center due to the saponification of fat and a possible cause for the change from an elliptical to a more spherical or doughnutlike shape. Intralesional administration of DCA may offer patients with extensive lipomas, such as those seen in patients with Dercum disease, an alternative, less-invasive option to assist with pain and tumor burden when excision is not feasible. Although treatments with DCA can be associated with side effects, including pain, swelling, bruising, erythema, induration, and numbness, all 3 of our patients had ultimate mitigation of pain and reduction in lipoma size within months of the injection. Additional studies should be explored to determine the optimal dose and frequency of administration of DCA that could benefit patients with Dercum disease.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Dercum’s disease. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛drek M, Kramza J, et al. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281-287. doi:10.5114/reum.2019.89521

- Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-23

- Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (Lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:17-22. doi:10.1007/s00296-008-0635-3

- Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153. doi:10.2147/JPR.S12351

- Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e950. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000950

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 222528, deoxycholic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Deoxycholic-acid. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Liu C, Li MK, Alster TS. Alternative cosmetic and medical applications of injectable deoxycholic acid: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1466-1472. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003159

- Santiago-Vázquez M, Michelen-Gómez EA, Carrasquillo-Bonilla D, et al. Intralesional deoxycholic acid: a potential therapeutic alternative for the treatment of lipomas arising in the face. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:112-114. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.037

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9

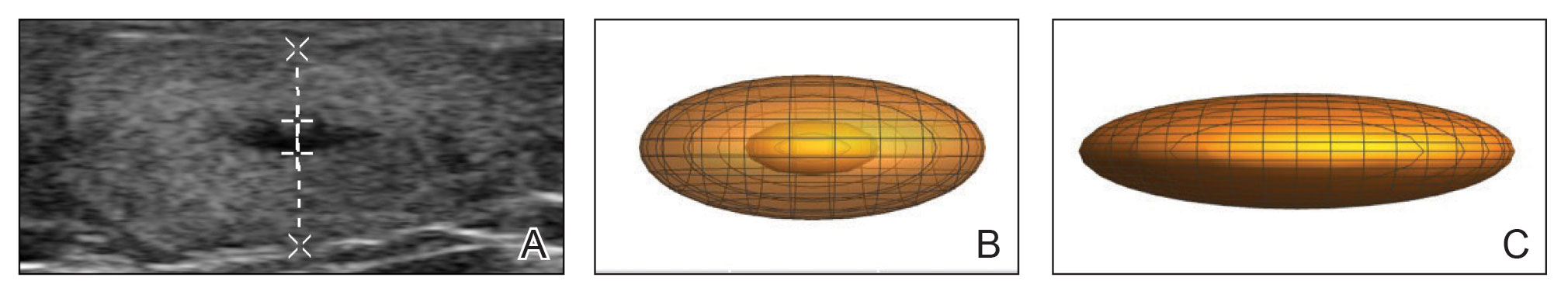

We present 3 patients who requested treatment for numerous painful lipomas. Given the extent of their disease, surgical options were not feasible, and the patients opted to try a nonsurgical alternative. In each case, the painful lipomas that were chosen for treatment were injected with 2 mL of DCA. Injection-associated symptoms included swelling, tenderness, discoloration, and induration, which resolved over a period of months. Patient 1 had a treated lipoma that reduced in volume by approximately 35%, while the control continued to grow and doubled in volume. In patient 2, the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the mid thigh reduced in volume by almost 70%, and the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the right forearm reduced in volume by more than 40%, while the control grew by more than 20%. In patient 3, the volume of the treated lipoma decreased by 30%, and the control increased by 15%. The follow-up interval was shortest in patient 3—2 months as opposed to 11 months and 6 months for patients 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, more progress may be seen in patient 3 with more time. Interestingly, a change in shape of the lipoma was noted in patient 3 (Figure)—an increase in its depth while the center became anechoic, which is a sign of hollowing in the center due to the saponification of fat and a possible cause for the change from an elliptical to a more spherical or doughnutlike shape. Intralesional administration of DCA may offer patients with extensive lipomas, such as those seen in patients with Dercum disease, an alternative, less-invasive option to assist with pain and tumor burden when excision is not feasible. Although treatments with DCA can be associated with side effects, including pain, swelling, bruising, erythema, induration, and numbness, all 3 of our patients had ultimate mitigation of pain and reduction in lipoma size within months of the injection. Additional studies should be explored to determine the optimal dose and frequency of administration of DCA that could benefit patients with Dercum disease.

Dercum disease (or adiposis dolorosa) is a rare condition of unknown etiology characterized by multiple painful lipomas localized throughout the body.1,2 It typically presents in adults aged 35 to 50 years and is at least 5 times more common in women.3 It often is associated with comorbidities such as obesity, fatigue and weakness.1 There currently are no approved treatments for Dercum disease, only therapies tried with little to no efficacy for symptom management, including analgesics, excision, liposuction,1 lymphatic drainage,4 hypobaric pressure,5 and frequency rhythmic electrical modulation systems.6 For patients who continually develop widespread lesions, surgical excision is not feasible, which poses a therapeutic challenge. Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a bile acid that is approved to treat submental fat, disrupts the integrity of cell membranes, induces adipocyte lysis, and solubilizes fat when injected subcutaneously.7 We used DCA to mitigate pain and reduce lipoma size in patients with Dercum disease, which demonstrated lipoma reduction via ultrasonography in 3 patients.

Case Reports

Three patients presented to clinic with multiple painful subcutaneous nodules throughout several areas of the body and were screened using radiography. Ultrasonography demonstrated numerous lipomas consistent with Dercum disease. The lipomas were measured by ultrasonography to obtain 3-dimensional measurements of each lesion. The most painful lipomas identified by the patients were either treated with 2 mL of DCA (10 mg/mL) or served as a control with no treatment. Patients returned for symptom monitoring and repeat measurements of both treated and untreated lipomas. Two physicians with expertise in ultrasonography measured lesions in a blinded fashion. Photographs were obtained with patient consent.

Patient 1—A 45-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease that was confirmed via ultrasonography. A painful 1.63×1.64×0.55-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the left forearm, and a 1.17×1.26×0.39-cm lipoma was measured on the volar aspect of the right wrist. At a follow-up visit 11 months later, 2 mL of DCA was administered to the lipoma on the volar aspect of the left forearm, while the lipoma on the volar aspect of the right wrist was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported 1 week of swelling and tenderness of the treated area. Repeat imaging 4 months after administration of DCA revealed reduction of the treated lesion to 0.80×1.48×0.60 cm and growth of the untreated lesion to 1.32×2.17×0.52 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 34.55%, while the lipoma in the untreated control increased in volume from its original measurement by 111.11% (Table). The patient also reported decreased pain in the treated area at all follow-up visits in the 1 year following the procedure.

Patient 2—A 42-year-old woman with Dercum disease received administration of 2 mL of DCA to a 1.90×1.70×0.90-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh and 2 mL of DCA to a 2.40×3.07×0.60-cm lipoma on the volar aspect of the right forearm 2 weeks later. A 1.18×0.91×0.45-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm was monitored as an untreated control. The patient reported bruising and discoloration a few weeks following the procedure. At subsequent 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, the patient reported induration in the volar aspect of the right forearm and noticeable reduction in size of the lesion in the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported reduction in size of both lesions and improvement of the previously noted side effects. Repeat ultrasonography approximately 6 months after administration of DCA demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the left mid thigh to 0.92×0.96×0.57 cm and the volar aspect of the right forearm to 1.56×2.18×0.79 cm, with growth of the untreated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 1.37×1.11×0.39 cm. The treated lipomas reduced in volume by 68.42% and 41.25%, respectively, and the untreated control increased in volume by 22.08% (Table).

Patient 3—A 75-year-old woman with a family history of lipomas was diagnosed with Dercum disease verified by ultrasonography. The patient was administered 2 mL of DCA to a 2.65×3.19×0.71-cm lipoma of the volar aspect of the left forearm. A 1.66×2.02×0.38-cm lipoma of the lateral aspect of the right forearm was monitored as an untreated control. Following the procedure, the patient reported initial swelling that persisted for a few weeks followed by notable pain relief and a decrease in lipoma size. At 2-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain or other adverse effects, while repeat imaging demonstrated reduction of the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the left forearm to 2.13×2.56×0.75 cm and growth of the untreated lesion on the lateral aspect of the right forearm to 1.95×2.05×0.37 cm. The treated lipoma reduced in volume by 30.29%, and the untreated control increased in volume by 15.05% (Table).

Comment

Deoxycholic acid is a bile acid naturally found in the body that helps to emulsify and solubilize fats in the intestines. When injected subcutaneously, DCA becomes an adipolytic agent that induces inflammation and targets adipose degradation by macrophages, and it has been manufactured to reduce submental fat.7 Off-label use of DCA has been explored for nonsurgical body contouring and lipomas with promising results in some cases; however, these prior studies have been limited by the lack of quantitative objective measurements to effectively demonstrate the impact of treatment.8,9

We present 3 patients who requested treatment for numerous painful lipomas. Given the extent of their disease, surgical options were not feasible, and the patients opted to try a nonsurgical alternative. In each case, the painful lipomas that were chosen for treatment were injected with 2 mL of DCA. Injection-associated symptoms included swelling, tenderness, discoloration, and induration, which resolved over a period of months. Patient 1 had a treated lipoma that reduced in volume by approximately 35%, while the control continued to grow and doubled in volume. In patient 2, the treated lesion on the lateral aspect of the mid thigh reduced in volume by almost 70%, and the treated lesion on the volar aspect of the right forearm reduced in volume by more than 40%, while the control grew by more than 20%. In patient 3, the volume of the treated lipoma decreased by 30%, and the control increased by 15%. The follow-up interval was shortest in patient 3—2 months as opposed to 11 months and 6 months for patients 1 and 2, respectively; therefore, more progress may be seen in patient 3 with more time. Interestingly, a change in shape of the lipoma was noted in patient 3 (Figure)—an increase in its depth while the center became anechoic, which is a sign of hollowing in the center due to the saponification of fat and a possible cause for the change from an elliptical to a more spherical or doughnutlike shape. Intralesional administration of DCA may offer patients with extensive lipomas, such as those seen in patients with Dercum disease, an alternative, less-invasive option to assist with pain and tumor burden when excision is not feasible. Although treatments with DCA can be associated with side effects, including pain, swelling, bruising, erythema, induration, and numbness, all 3 of our patients had ultimate mitigation of pain and reduction in lipoma size within months of the injection. Additional studies should be explored to determine the optimal dose and frequency of administration of DCA that could benefit patients with Dercum disease.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Dercum’s disease. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛drek M, Kramza J, et al. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281-287. doi:10.5114/reum.2019.89521

- Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-23

- Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (Lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:17-22. doi:10.1007/s00296-008-0635-3

- Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153. doi:10.2147/JPR.S12351

- Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e950. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000950

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 222528, deoxycholic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Deoxycholic-acid. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Liu C, Li MK, Alster TS. Alternative cosmetic and medical applications of injectable deoxycholic acid: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1466-1472. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003159

- Santiago-Vázquez M, Michelen-Gómez EA, Carrasquillo-Bonilla D, et al. Intralesional deoxycholic acid: a potential therapeutic alternative for the treatment of lipomas arising in the face. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:112-114. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.037

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Dercum’s disease. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dercums-disease/.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛drek M, Kramza J, et al. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a review of clinical presentation and management. Reumatologia. 2019;57:281-287. doi:10.5114/reum.2019.89521

- Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:23. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-23

- Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (Lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:17-22. doi:10.1007/s00296-008-0635-3

- Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153. doi:10.2147/JPR.S12351

- Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, et al. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e950. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000950

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem compound summary for CID 222528, deoxycholic acid. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Deoxycholic-acid. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Liu C, Li MK, Alster TS. Alternative cosmetic and medical applications of injectable deoxycholic acid: a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1466-1472. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003159

- Santiago-Vázquez M, Michelen-Gómez EA, Carrasquillo-Bonilla D, et al. Intralesional deoxycholic acid: a potential therapeutic alternative for the treatment of lipomas arising in the face. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;13:112-114. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.037

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should consider Dercum disease when encountering a patient with numerous painful lipomas.

- Subcutaneous administration of deoxycholic acid resulted in a notable reduction in pain and size of lipomas by 30% to 68% per radiographic review.

- Deoxycholic acid may provide an alternative therapeutic option for patients who have Dercum disease with substantial tumor burden.

COVID-19 Vaccine Reactions in Dermatology: “Filling” in the Gaps

As we marked the 1-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 100 million Americans had received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, heralding some sense of relief and enabling us to envision a return to something resembling life before lockdown.1 Amid these breakthroughs and vaccination campaigns forging ahead worldwide, we saw new questions and problems arise. Vaccine hesitancy was already an issue in many segments of society where misinformation and mistrust of the medical establishment have served as barriers to the progress of public health. Once reports of adverse reactions following COVID-19 vaccination—such as those linked to use of facial fillers—made news headlines, many in the dermatology community began facing inquiries from patients questioning if they should wait to receive the vaccine or skip it entirely. As dermatologists, we must be informed and prepared to address these situations, to manage adverse reactions when they arise, and to encourage and promote vaccination during this critical time for public health in our society.

Cutaneous Vaccine Reactions and Facial Fillers

As public COVID-19 vaccinations move forward, dermatologic side effects, which were first noted during clinical trials, have received amplified attention, despite the fact that these cutaneous reactions—including localized injection-site redness and swelling, generalized urticarial and morbilliform eruptions, and even facial filler reactions—have been reported as relatively minor and self-limited.2 The excipient polyethylene glycol has been suspected as a possible etiology of vaccine-related allergic and hypersensitivity reactions, suggesting care be taken in those who are patch-test positive or have a history of allergy to polyethylene glycol–containing products (eg, penicillin, laxatives, makeup, certain dermal fillers).2,3 Although rare, facial and lip swelling reactions in those with a prior history of facial fillers in COVID-19 vaccine trials have drawn particular public concern and potential vaccine hesitancy given that more than 2.7 million Americans seek treatment with dermal fillers annually. There has been continued demand for these treatments during the pandemic, particularly due to aesthetic sensitivity surrounding video conferencing.4

Release of trial data from the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine prompted a discourse around safety and recommended protocols for filler procedures in the community of aesthetic medicine, as 3 participants in the experimental arm—all of whom had a history of treatment with facial filler injections—were reported to have facial or lip swelling shortly following vaccination. Two of these cases were considered to be serious adverse events due to extensive facial swelling, with the participants having received filler injections 6 months and 2 weeks prior to vaccination, respectively.5 A third participant experienced lip swelling only, which according to the US Food and Drug Administration briefing document was considered “medically significant” but not a serious adverse event, with unknown timing of the most recent filler injection. In all cases, symptom onset began 1 or 2 days following vaccination, and all resolved with either no or minimal intervention.6 The US Food and Drug Administration briefing document does not detail which type of fillers each participant had received, but subsequent reports indicated hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers. Of note, one patient in the placebo arm of the trial also developed progressive periorbital and facial edema in the setting of known filler injections performed 5 weeks prior, requiring treatment with corticosteroids and barring her from receiving a second injection in the trial.7

After public vaccination started, additional reports have emerged of facial edema occurring following administration of both the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.2,8,9 In one series, 4 cases of facial swelling were reported in patients who had HA filler placed more than 1 year prior to vaccination.9 The first patient, who had a history of HA fillers in the temples and cheeks, developed moderate periorbital swelling 2 days following her second dose of the Pfizer vaccine. Another patient who had received a series of filler injections over the last 3 years experienced facial swelling 24 hours after her second dose of the Moderna vaccine and also reported a similar reaction in the past following an upper respiratory tract infection. The third patient developed perioral and infraorbital edema 18 hours after her first dose of the Moderna vaccine. The fourth patient developed inflammation in filler-treated areas 10 days after the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine and notably had a history of filler reaction to an unknown trigger in 2019 that was treated with hyaluronidase, intralesional steroids, and 5-fluorouracil. All cases of facial edema reportedly resolved.9

The observed adverse events have been proposed as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (DTRs) to facial fillers and are suspected to be triggered by the COVID-19 spike protein and subsequent immunogenic response. This reaction is not unique to the COVID-19 vaccines; in fact, many inflammatory stimuli such as sinus infections, flulike illnesses, facial injury, dental procedures, and exposure to certain medications and chemotherapeutics have triggered DTRs in filler patients, especially in those with genetic or immunologic risk factors including certain human leukocyte antigen subtypes or autoimmune disorders.3

Counseling Patients and Reducing Risks

As reports of DTRs to facial fillers after COVID-19 vaccination continue to emerge, it is not surprising that patients may become confused by potential side effects and postpone vaccination as a result. This evolving situation has called upon aesthetic physicians to adapt our practice and prepare our patients. Most importantly, we must continue to follow the data and integrate evidence-based COVID-19 vaccine–related counseling into our office visits. It is paramount to encourage vaccination and inform patients that these rare adverse events are both temporary and treatable. Given the currently available data, patients with a history of treatment with dermal fillers should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine; however, we may provide suggestions to lessen the likelihood of adverse reactions and ease patient concerns. For example, it may be helpful to consider a time frame between vaccination and filler procedures that is longer than 2 weeks, just as would be advised for those having dental procedures or with recent infections, and potentially longer windows for those with risk factors such as prior sensitivity to dermal fillers, autoimmune disorders, or those on immunomodulatory medications. Dilution of fillers with saline or lidocaine or use of non-HA fillers also may be suggested around the time of vaccination to mitigate the risk of DTRs.3

Managing Vaccine Reactions

If facial swelling does occur despite these precautions and lasts longer than 48 hours, treatment with antihistamines, steroids, and/or hyaluronidase has been successful in vaccine trial and posttrial patients, both alone or in combination, and are likely to resolve edema promptly without altering the effectiveness of the vaccine.3,5,9 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors such as lisinopril more recently have been recommended for treatment of facial edema following COVID-19 vaccination,9 but questions remain regarding the true efficacy in this scenario given that the majority of swelling reactions resolve without this treatment. Additionally, there were no controls to indicate treatment with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor demonstrated an actual impact. Dermatologists generally are wary of adding medications of questionable utility that are associated with potential side effects and drug reactions, given that we often are tasked with managing the consequences of such mistakes. Thus, to avoid additional harm in the setting of insufficient evidence, as was seen following widespread use of hydroxychloroquine at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, well-structured studies are required before such interventions can be recommended.

If symptoms arise following the first vaccine injection, they can be managed if needed while patients are reassured and advised to obtain their second dose, with pretreatment considerations including antihistamines and instruction to present to the emergency department if a more severe reaction is suspected.2 In a larger sense, we also can contribute to the collective knowledge, growth, and preparedness of the medical community by reporting cases of adverse events to vaccine reporting systems and registries, such as the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s V-Safe After Vaccination Health Checker, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Dermatology Registry.

Final Thoughts

As dermatologists, we now find ourselves in the familiar role of balancing the aesthetic goals of our patients with our primary mission of public health and safety at a time when their health and well-being is particularly vulnerable. Adverse reactions will continue to occur as larger segments of the world’s population become vaccinated. Meanwhile, we must continue to manage symptoms, dispel myths, emphasize that any dermatologic risk posed by the COVID-19 vaccines is far outweighed by the benefits of immunization, and promote health and education, looking ahead to life beyond the pandemic.

- Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. Our World in Data website. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases [published online April 7, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.092

- Rice SM, Ferree SD, Mesinkovska NA, et al. The art of prevention: COVID-19 vaccine preparedness for the dermatologist. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:209-212. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.007

- Rice SM, Siegel JA, Libby T, et al. Zooming into cosmetic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: the provider’s perspective. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:213-216.

- FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/144434/download

- Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine may cause swelling, inflammation in those with facial fillers. American Society of Plastic Surgeons website. Published December 27, 2020. Accessed May 11, 2021. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-medical-professionals/publications/psn-extra/news/modernas-covid19-vaccine-may-cause-swelling-inflammation-in-those-with-facial-fillers

- Munavalli GG, Guthridge R, Knutsen-Larson S, et al. COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 virus spike protein-related delayed inflammatory reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: a challenging clinical conundrum in diagnosis and treatment [published online February 9, 2021]. Arch Dermatol Res. doi:10.1007/s00403-021-02190-6

- Schlessinger J. Update on COVID-19 vaccines and dermal fillers. Practical Dermatol. February 2021:46-47. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2021-feb/update-on-covid-19-vaccines-and-dermal-fillers/pdf

- Munavalli GG, Knutsen-Larson S, Lupo MP, et al. Oral angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for treatment of delayed inflammatory reaction to dermal hyaluronic acid fillers following COVID-19 vaccination—a model for inhibition of angiotensin II-induced cutaneous inflammation. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:63-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.02.018

As we marked the 1-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 100 million Americans had received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, heralding some sense of relief and enabling us to envision a return to something resembling life before lockdown.1 Amid these breakthroughs and vaccination campaigns forging ahead worldwide, we saw new questions and problems arise. Vaccine hesitancy was already an issue in many segments of society where misinformation and mistrust of the medical establishment have served as barriers to the progress of public health. Once reports of adverse reactions following COVID-19 vaccination—such as those linked to use of facial fillers—made news headlines, many in the dermatology community began facing inquiries from patients questioning if they should wait to receive the vaccine or skip it entirely. As dermatologists, we must be informed and prepared to address these situations, to manage adverse reactions when they arise, and to encourage and promote vaccination during this critical time for public health in our society.

Cutaneous Vaccine Reactions and Facial Fillers

As public COVID-19 vaccinations move forward, dermatologic side effects, which were first noted during clinical trials, have received amplified attention, despite the fact that these cutaneous reactions—including localized injection-site redness and swelling, generalized urticarial and morbilliform eruptions, and even facial filler reactions—have been reported as relatively minor and self-limited.2 The excipient polyethylene glycol has been suspected as a possible etiology of vaccine-related allergic and hypersensitivity reactions, suggesting care be taken in those who are patch-test positive or have a history of allergy to polyethylene glycol–containing products (eg, penicillin, laxatives, makeup, certain dermal fillers).2,3 Although rare, facial and lip swelling reactions in those with a prior history of facial fillers in COVID-19 vaccine trials have drawn particular public concern and potential vaccine hesitancy given that more than 2.7 million Americans seek treatment with dermal fillers annually. There has been continued demand for these treatments during the pandemic, particularly due to aesthetic sensitivity surrounding video conferencing.4

Release of trial data from the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine prompted a discourse around safety and recommended protocols for filler procedures in the community of aesthetic medicine, as 3 participants in the experimental arm—all of whom had a history of treatment with facial filler injections—were reported to have facial or lip swelling shortly following vaccination. Two of these cases were considered to be serious adverse events due to extensive facial swelling, with the participants having received filler injections 6 months and 2 weeks prior to vaccination, respectively.5 A third participant experienced lip swelling only, which according to the US Food and Drug Administration briefing document was considered “medically significant” but not a serious adverse event, with unknown timing of the most recent filler injection. In all cases, symptom onset began 1 or 2 days following vaccination, and all resolved with either no or minimal intervention.6 The US Food and Drug Administration briefing document does not detail which type of fillers each participant had received, but subsequent reports indicated hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers. Of note, one patient in the placebo arm of the trial also developed progressive periorbital and facial edema in the setting of known filler injections performed 5 weeks prior, requiring treatment with corticosteroids and barring her from receiving a second injection in the trial.7

After public vaccination started, additional reports have emerged of facial edema occurring following administration of both the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.2,8,9 In one series, 4 cases of facial swelling were reported in patients who had HA filler placed more than 1 year prior to vaccination.9 The first patient, who had a history of HA fillers in the temples and cheeks, developed moderate periorbital swelling 2 days following her second dose of the Pfizer vaccine. Another patient who had received a series of filler injections over the last 3 years experienced facial swelling 24 hours after her second dose of the Moderna vaccine and also reported a similar reaction in the past following an upper respiratory tract infection. The third patient developed perioral and infraorbital edema 18 hours after her first dose of the Moderna vaccine. The fourth patient developed inflammation in filler-treated areas 10 days after the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine and notably had a history of filler reaction to an unknown trigger in 2019 that was treated with hyaluronidase, intralesional steroids, and 5-fluorouracil. All cases of facial edema reportedly resolved.9

The observed adverse events have been proposed as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (DTRs) to facial fillers and are suspected to be triggered by the COVID-19 spike protein and subsequent immunogenic response. This reaction is not unique to the COVID-19 vaccines; in fact, many inflammatory stimuli such as sinus infections, flulike illnesses, facial injury, dental procedures, and exposure to certain medications and chemotherapeutics have triggered DTRs in filler patients, especially in those with genetic or immunologic risk factors including certain human leukocyte antigen subtypes or autoimmune disorders.3

Counseling Patients and Reducing Risks

As reports of DTRs to facial fillers after COVID-19 vaccination continue to emerge, it is not surprising that patients may become confused by potential side effects and postpone vaccination as a result. This evolving situation has called upon aesthetic physicians to adapt our practice and prepare our patients. Most importantly, we must continue to follow the data and integrate evidence-based COVID-19 vaccine–related counseling into our office visits. It is paramount to encourage vaccination and inform patients that these rare adverse events are both temporary and treatable. Given the currently available data, patients with a history of treatment with dermal fillers should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine; however, we may provide suggestions to lessen the likelihood of adverse reactions and ease patient concerns. For example, it may be helpful to consider a time frame between vaccination and filler procedures that is longer than 2 weeks, just as would be advised for those having dental procedures or with recent infections, and potentially longer windows for those with risk factors such as prior sensitivity to dermal fillers, autoimmune disorders, or those on immunomodulatory medications. Dilution of fillers with saline or lidocaine or use of non-HA fillers also may be suggested around the time of vaccination to mitigate the risk of DTRs.3

Managing Vaccine Reactions

If facial swelling does occur despite these precautions and lasts longer than 48 hours, treatment with antihistamines, steroids, and/or hyaluronidase has been successful in vaccine trial and posttrial patients, both alone or in combination, and are likely to resolve edema promptly without altering the effectiveness of the vaccine.3,5,9 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors such as lisinopril more recently have been recommended for treatment of facial edema following COVID-19 vaccination,9 but questions remain regarding the true efficacy in this scenario given that the majority of swelling reactions resolve without this treatment. Additionally, there were no controls to indicate treatment with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor demonstrated an actual impact. Dermatologists generally are wary of adding medications of questionable utility that are associated with potential side effects and drug reactions, given that we often are tasked with managing the consequences of such mistakes. Thus, to avoid additional harm in the setting of insufficient evidence, as was seen following widespread use of hydroxychloroquine at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, well-structured studies are required before such interventions can be recommended.

If symptoms arise following the first vaccine injection, they can be managed if needed while patients are reassured and advised to obtain their second dose, with pretreatment considerations including antihistamines and instruction to present to the emergency department if a more severe reaction is suspected.2 In a larger sense, we also can contribute to the collective knowledge, growth, and preparedness of the medical community by reporting cases of adverse events to vaccine reporting systems and registries, such as the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s V-Safe After Vaccination Health Checker, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Dermatology Registry.

Final Thoughts

As dermatologists, we now find ourselves in the familiar role of balancing the aesthetic goals of our patients with our primary mission of public health and safety at a time when their health and well-being is particularly vulnerable. Adverse reactions will continue to occur as larger segments of the world’s population become vaccinated. Meanwhile, we must continue to manage symptoms, dispel myths, emphasize that any dermatologic risk posed by the COVID-19 vaccines is far outweighed by the benefits of immunization, and promote health and education, looking ahead to life beyond the pandemic.

As we marked the 1-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 100 million Americans had received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, heralding some sense of relief and enabling us to envision a return to something resembling life before lockdown.1 Amid these breakthroughs and vaccination campaigns forging ahead worldwide, we saw new questions and problems arise. Vaccine hesitancy was already an issue in many segments of society where misinformation and mistrust of the medical establishment have served as barriers to the progress of public health. Once reports of adverse reactions following COVID-19 vaccination—such as those linked to use of facial fillers—made news headlines, many in the dermatology community began facing inquiries from patients questioning if they should wait to receive the vaccine or skip it entirely. As dermatologists, we must be informed and prepared to address these situations, to manage adverse reactions when they arise, and to encourage and promote vaccination during this critical time for public health in our society.

Cutaneous Vaccine Reactions and Facial Fillers

As public COVID-19 vaccinations move forward, dermatologic side effects, which were first noted during clinical trials, have received amplified attention, despite the fact that these cutaneous reactions—including localized injection-site redness and swelling, generalized urticarial and morbilliform eruptions, and even facial filler reactions—have been reported as relatively minor and self-limited.2 The excipient polyethylene glycol has been suspected as a possible etiology of vaccine-related allergic and hypersensitivity reactions, suggesting care be taken in those who are patch-test positive or have a history of allergy to polyethylene glycol–containing products (eg, penicillin, laxatives, makeup, certain dermal fillers).2,3 Although rare, facial and lip swelling reactions in those with a prior history of facial fillers in COVID-19 vaccine trials have drawn particular public concern and potential vaccine hesitancy given that more than 2.7 million Americans seek treatment with dermal fillers annually. There has been continued demand for these treatments during the pandemic, particularly due to aesthetic sensitivity surrounding video conferencing.4

Release of trial data from the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine prompted a discourse around safety and recommended protocols for filler procedures in the community of aesthetic medicine, as 3 participants in the experimental arm—all of whom had a history of treatment with facial filler injections—were reported to have facial or lip swelling shortly following vaccination. Two of these cases were considered to be serious adverse events due to extensive facial swelling, with the participants having received filler injections 6 months and 2 weeks prior to vaccination, respectively.5 A third participant experienced lip swelling only, which according to the US Food and Drug Administration briefing document was considered “medically significant” but not a serious adverse event, with unknown timing of the most recent filler injection. In all cases, symptom onset began 1 or 2 days following vaccination, and all resolved with either no or minimal intervention.6 The US Food and Drug Administration briefing document does not detail which type of fillers each participant had received, but subsequent reports indicated hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers. Of note, one patient in the placebo arm of the trial also developed progressive periorbital and facial edema in the setting of known filler injections performed 5 weeks prior, requiring treatment with corticosteroids and barring her from receiving a second injection in the trial.7

After public vaccination started, additional reports have emerged of facial edema occurring following administration of both the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines.2,8,9 In one series, 4 cases of facial swelling were reported in patients who had HA filler placed more than 1 year prior to vaccination.9 The first patient, who had a history of HA fillers in the temples and cheeks, developed moderate periorbital swelling 2 days following her second dose of the Pfizer vaccine. Another patient who had received a series of filler injections over the last 3 years experienced facial swelling 24 hours after her second dose of the Moderna vaccine and also reported a similar reaction in the past following an upper respiratory tract infection. The third patient developed perioral and infraorbital edema 18 hours after her first dose of the Moderna vaccine. The fourth patient developed inflammation in filler-treated areas 10 days after the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine and notably had a history of filler reaction to an unknown trigger in 2019 that was treated with hyaluronidase, intralesional steroids, and 5-fluorouracil. All cases of facial edema reportedly resolved.9

The observed adverse events have been proposed as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (DTRs) to facial fillers and are suspected to be triggered by the COVID-19 spike protein and subsequent immunogenic response. This reaction is not unique to the COVID-19 vaccines; in fact, many inflammatory stimuli such as sinus infections, flulike illnesses, facial injury, dental procedures, and exposure to certain medications and chemotherapeutics have triggered DTRs in filler patients, especially in those with genetic or immunologic risk factors including certain human leukocyte antigen subtypes or autoimmune disorders.3

Counseling Patients and Reducing Risks

As reports of DTRs to facial fillers after COVID-19 vaccination continue to emerge, it is not surprising that patients may become confused by potential side effects and postpone vaccination as a result. This evolving situation has called upon aesthetic physicians to adapt our practice and prepare our patients. Most importantly, we must continue to follow the data and integrate evidence-based COVID-19 vaccine–related counseling into our office visits. It is paramount to encourage vaccination and inform patients that these rare adverse events are both temporary and treatable. Given the currently available data, patients with a history of treatment with dermal fillers should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine; however, we may provide suggestions to lessen the likelihood of adverse reactions and ease patient concerns. For example, it may be helpful to consider a time frame between vaccination and filler procedures that is longer than 2 weeks, just as would be advised for those having dental procedures or with recent infections, and potentially longer windows for those with risk factors such as prior sensitivity to dermal fillers, autoimmune disorders, or those on immunomodulatory medications. Dilution of fillers with saline or lidocaine or use of non-HA fillers also may be suggested around the time of vaccination to mitigate the risk of DTRs.3

Managing Vaccine Reactions

If facial swelling does occur despite these precautions and lasts longer than 48 hours, treatment with antihistamines, steroids, and/or hyaluronidase has been successful in vaccine trial and posttrial patients, both alone or in combination, and are likely to resolve edema promptly without altering the effectiveness of the vaccine.3,5,9 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors such as lisinopril more recently have been recommended for treatment of facial edema following COVID-19 vaccination,9 but questions remain regarding the true efficacy in this scenario given that the majority of swelling reactions resolve without this treatment. Additionally, there were no controls to indicate treatment with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor demonstrated an actual impact. Dermatologists generally are wary of adding medications of questionable utility that are associated with potential side effects and drug reactions, given that we often are tasked with managing the consequences of such mistakes. Thus, to avoid additional harm in the setting of insufficient evidence, as was seen following widespread use of hydroxychloroquine at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, well-structured studies are required before such interventions can be recommended.

If symptoms arise following the first vaccine injection, they can be managed if needed while patients are reassured and advised to obtain their second dose, with pretreatment considerations including antihistamines and instruction to present to the emergency department if a more severe reaction is suspected.2 In a larger sense, we also can contribute to the collective knowledge, growth, and preparedness of the medical community by reporting cases of adverse events to vaccine reporting systems and registries, such as the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s V-Safe After Vaccination Health Checker, and the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Dermatology Registry.

Final Thoughts

As dermatologists, we now find ourselves in the familiar role of balancing the aesthetic goals of our patients with our primary mission of public health and safety at a time when their health and well-being is particularly vulnerable. Adverse reactions will continue to occur as larger segments of the world’s population become vaccinated. Meanwhile, we must continue to manage symptoms, dispel myths, emphasize that any dermatologic risk posed by the COVID-19 vaccines is far outweighed by the benefits of immunization, and promote health and education, looking ahead to life beyond the pandemic.

- Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. Our World in Data website. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases [published online April 7, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.092

- Rice SM, Ferree SD, Mesinkovska NA, et al. The art of prevention: COVID-19 vaccine preparedness for the dermatologist. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:209-212. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.007

- Rice SM, Siegel JA, Libby T, et al. Zooming into cosmetic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: the provider’s perspective. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:213-216.

- FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/144434/download

- Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine may cause swelling, inflammation in those with facial fillers. American Society of Plastic Surgeons website. Published December 27, 2020. Accessed May 11, 2021. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-medical-professionals/publications/psn-extra/news/modernas-covid19-vaccine-may-cause-swelling-inflammation-in-those-with-facial-fillers

- Munavalli GG, Guthridge R, Knutsen-Larson S, et al. COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 virus spike protein-related delayed inflammatory reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: a challenging clinical conundrum in diagnosis and treatment [published online February 9, 2021]. Arch Dermatol Res. doi:10.1007/s00403-021-02190-6

- Schlessinger J. Update on COVID-19 vaccines and dermal fillers. Practical Dermatol. February 2021:46-47. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2021-feb/update-on-covid-19-vaccines-and-dermal-fillers/pdf

- Munavalli GG, Knutsen-Larson S, Lupo MP, et al. Oral angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for treatment of delayed inflammatory reaction to dermal hyaluronic acid fillers following COVID-19 vaccination—a model for inhibition of angiotensin II-induced cutaneous inflammation. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:63-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.02.018

- Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. Our World in Data website. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases [published online April 7, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.092

- Rice SM, Ferree SD, Mesinkovska NA, et al. The art of prevention: COVID-19 vaccine preparedness for the dermatologist. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:209-212. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.007

- Rice SM, Siegel JA, Libby T, et al. Zooming into cosmetic procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: the provider’s perspective. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:213-216.

- FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/144434/download

- Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine may cause swelling, inflammation in those with facial fillers. American Society of Plastic Surgeons website. Published December 27, 2020. Accessed May 11, 2021. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-medical-professionals/publications/psn-extra/news/modernas-covid19-vaccine-may-cause-swelling-inflammation-in-those-with-facial-fillers

- Munavalli GG, Guthridge R, Knutsen-Larson S, et al. COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 virus spike protein-related delayed inflammatory reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: a challenging clinical conundrum in diagnosis and treatment [published online February 9, 2021]. Arch Dermatol Res. doi:10.1007/s00403-021-02190-6

- Schlessinger J. Update on COVID-19 vaccines and dermal fillers. Practical Dermatol. February 2021:46-47. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://practicaldermatology.com/articles/2021-feb/update-on-covid-19-vaccines-and-dermal-fillers/pdf

- Munavalli GG, Knutsen-Larson S, Lupo MP, et al. Oral angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for treatment of delayed inflammatory reaction to dermal hyaluronic acid fillers following COVID-19 vaccination—a model for inhibition of angiotensin II-induced cutaneous inflammation. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:63-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.02.018