User login

ESC: Alirocumab ‘cures’ heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia

LONDON – The largest-ever treatment study of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia shows that the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab achieves “truly astounding” reductions in LDL cholesterol and atherogenic lipid particles through 78 weeks of follow-up, Dr. John J.P. Kastelein said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“These findings show reductions in LDL levels in these individuals that were completely impossible until now. Basically, this therapy in conjunction with statins and ezetimibe cures this genetic disease because LDL levels in these individuals are now lower than in the general population, which is, of course, something that we’ve never seen before,” said Dr. Kastelein, chairman of the department of vascular medicine at the University of Amsterdam.

Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) is the most common autosomal dominant genetic disorder, with an estimated prevalence worldwide of 1 in 200 in the general population. The associated highly elevated LDL levels bring a markedly increased risk of premature cardiovascular events. Only about 20% of patients with HeFH are able to achieve an LDL of 100 mg/dL or less despite maximum-tolerated doses of statins plus ezetimibe (Vytorin).

Dr. Kastelein presented the 78-week lipid-lowering results from four phase III randomized, double-blind clinical trials involving 1,257 HeFH patients unable to attain LDL goals despite maximum-tolerated statin therapy, typically supplemented with ezetimibe.

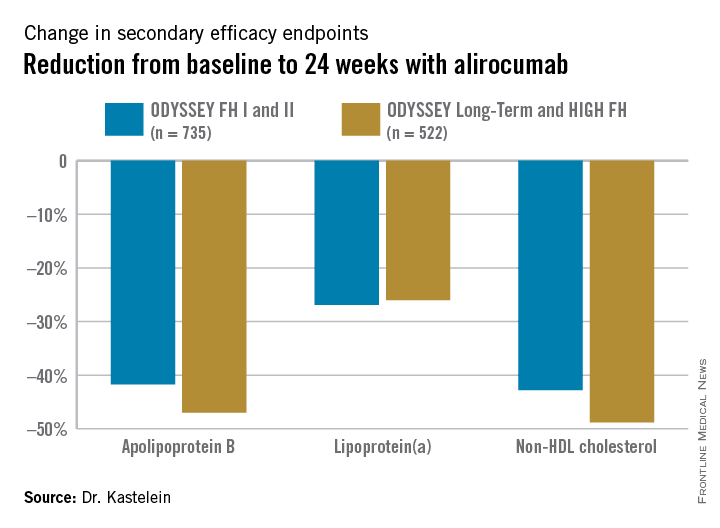

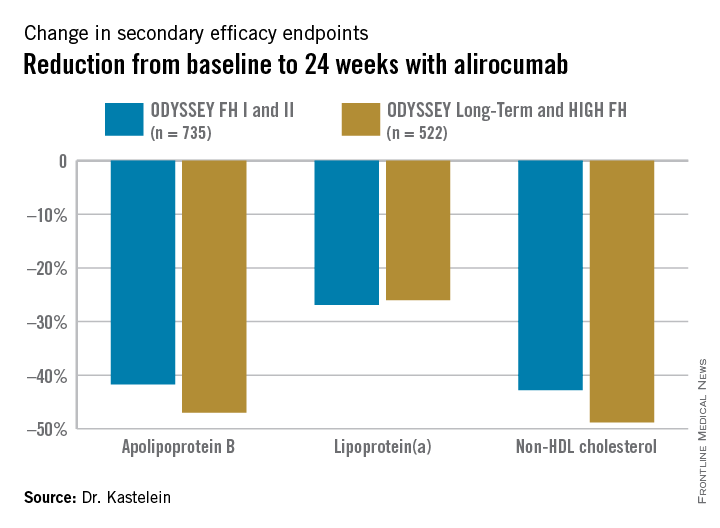

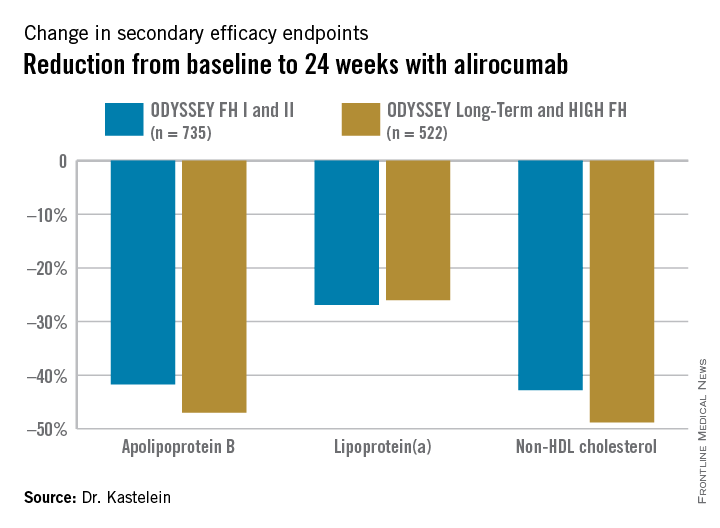

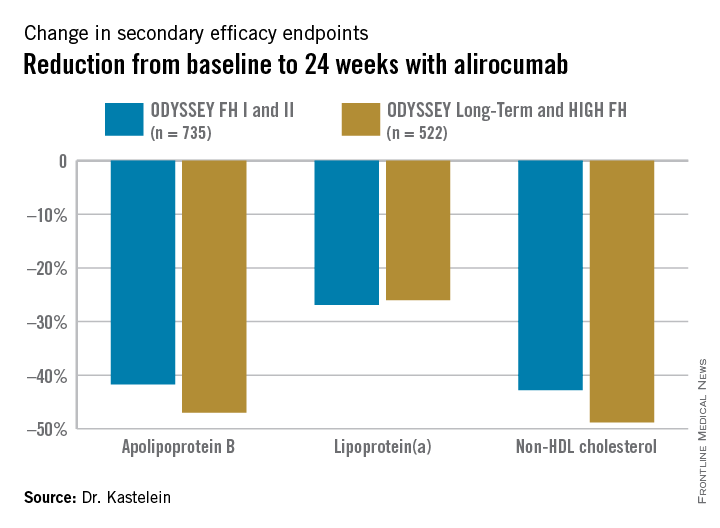

Participants were randomly assigned 2:1 to biweekly subcutaneous injections of alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) or placebo on top of background maximum tolerated statin therapy, usually accompanied by ezetimibe. The ODYSSEY FH I and FH II studies included 735 patients, with the alirocumab group starting on the PCSK9 inhibitor at 75 mg every 2 weeks, with the dose being doubled to 150 mg at 24 weeks in patients who hadn’t achieved an LDL level of 70 mg/dL or less at that point. The 522 HeFH patients in the ODYSSEY Long-Term study and the HIGH FH trial had higher baseline LDL levels and greater cardiovascular risk, and they therefore were on alirocumab at 150 mg every 2 weeks or placebo from the outset.

Fifty percent of alirocumab-treated patients in the FH I and II studies and 63% in the other two trials achieved an LDL level below 70 mg/dL at week 24, as did 0.6% and 1% of control patients, respectively. Dr. Kastelein characterized that as a jaw-dropping result.

“I have seen very few HeFH patients in my clinic – which is one of the largest in the world in terms of numbers of patients – who reached the goal of an LDL below 70 mg/dL,” he commented.

The outcomes in terms of secondary lipid endpoints provided an added bonus.

Absolutely no tachyphylaxis or return toward baseline LDL occurred over the course of 78 weeks of treatment, Dr. Kastelein continued.

The safety performance of alirocumab was highly reassuring: Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 3.9% of 837 alirocumab-treated patients and 3.6% on placebo. Overall, there was no significant difference between the two groups in rates of headache, musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders, infections, injection-site reactions, adjudicated cardiovascular events, allergic reactions, neurocognitive disorders, elevated liver enzymes, or any other safety endpoint.

Both alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha), another PCSK9 inhibitor, have been approved for the treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European regulators.

The next round of PCSK9 inhibitor studies, now ongoing, involves enrolling 70,000 subjects at increased cardiovascular risk in order to assess whether the level of LDL lowering achieved with these novel agents translates into a reduction in cardiovascular events.

Session cochair Dr. Barbara Casadei, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford (England), posed a question: Statin therapy has been shown to increase the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes – how about the PCSK9 inhibitors?

Dr. Kastelein replied that he recently published a study of more than 25,000 Dutch individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia and showed that their prevalence of type 2 diabetes was significantly lower than in their unaffected relatives (JAMA 2015 Mar 10;313[10]:1029-36).

“One of my theories is that the PCSK9 inhibitors reduce the number of LDL receptors on beta cells in the pancreas, so there’s less cholesterol influx, and since cholesterol is toxic to beta cells, the beta cells of PCSK9-inhibitor-treated patients live longer and therefore these individuals will have less type 2 diabetes. Statins do exactly the opposite: They up-regulate LDL receptors, so there will be more cholesterol coming into the beta cell and the theory is that this will result in an increase in type 2 diabetes,” he explained.

The HeFH studies were supported by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kastelein reported having received consulting fees from those pharmaceutical companies and nearly two dozen others.

LONDON – The largest-ever treatment study of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia shows that the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab achieves “truly astounding” reductions in LDL cholesterol and atherogenic lipid particles through 78 weeks of follow-up, Dr. John J.P. Kastelein said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“These findings show reductions in LDL levels in these individuals that were completely impossible until now. Basically, this therapy in conjunction with statins and ezetimibe cures this genetic disease because LDL levels in these individuals are now lower than in the general population, which is, of course, something that we’ve never seen before,” said Dr. Kastelein, chairman of the department of vascular medicine at the University of Amsterdam.

Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) is the most common autosomal dominant genetic disorder, with an estimated prevalence worldwide of 1 in 200 in the general population. The associated highly elevated LDL levels bring a markedly increased risk of premature cardiovascular events. Only about 20% of patients with HeFH are able to achieve an LDL of 100 mg/dL or less despite maximum-tolerated doses of statins plus ezetimibe (Vytorin).

Dr. Kastelein presented the 78-week lipid-lowering results from four phase III randomized, double-blind clinical trials involving 1,257 HeFH patients unable to attain LDL goals despite maximum-tolerated statin therapy, typically supplemented with ezetimibe.

Participants were randomly assigned 2:1 to biweekly subcutaneous injections of alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) or placebo on top of background maximum tolerated statin therapy, usually accompanied by ezetimibe. The ODYSSEY FH I and FH II studies included 735 patients, with the alirocumab group starting on the PCSK9 inhibitor at 75 mg every 2 weeks, with the dose being doubled to 150 mg at 24 weeks in patients who hadn’t achieved an LDL level of 70 mg/dL or less at that point. The 522 HeFH patients in the ODYSSEY Long-Term study and the HIGH FH trial had higher baseline LDL levels and greater cardiovascular risk, and they therefore were on alirocumab at 150 mg every 2 weeks or placebo from the outset.

Fifty percent of alirocumab-treated patients in the FH I and II studies and 63% in the other two trials achieved an LDL level below 70 mg/dL at week 24, as did 0.6% and 1% of control patients, respectively. Dr. Kastelein characterized that as a jaw-dropping result.

“I have seen very few HeFH patients in my clinic – which is one of the largest in the world in terms of numbers of patients – who reached the goal of an LDL below 70 mg/dL,” he commented.

The outcomes in terms of secondary lipid endpoints provided an added bonus.

Absolutely no tachyphylaxis or return toward baseline LDL occurred over the course of 78 weeks of treatment, Dr. Kastelein continued.

The safety performance of alirocumab was highly reassuring: Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 3.9% of 837 alirocumab-treated patients and 3.6% on placebo. Overall, there was no significant difference between the two groups in rates of headache, musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders, infections, injection-site reactions, adjudicated cardiovascular events, allergic reactions, neurocognitive disorders, elevated liver enzymes, or any other safety endpoint.

Both alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha), another PCSK9 inhibitor, have been approved for the treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European regulators.

The next round of PCSK9 inhibitor studies, now ongoing, involves enrolling 70,000 subjects at increased cardiovascular risk in order to assess whether the level of LDL lowering achieved with these novel agents translates into a reduction in cardiovascular events.

Session cochair Dr. Barbara Casadei, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford (England), posed a question: Statin therapy has been shown to increase the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes – how about the PCSK9 inhibitors?

Dr. Kastelein replied that he recently published a study of more than 25,000 Dutch individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia and showed that their prevalence of type 2 diabetes was significantly lower than in their unaffected relatives (JAMA 2015 Mar 10;313[10]:1029-36).

“One of my theories is that the PCSK9 inhibitors reduce the number of LDL receptors on beta cells in the pancreas, so there’s less cholesterol influx, and since cholesterol is toxic to beta cells, the beta cells of PCSK9-inhibitor-treated patients live longer and therefore these individuals will have less type 2 diabetes. Statins do exactly the opposite: They up-regulate LDL receptors, so there will be more cholesterol coming into the beta cell and the theory is that this will result in an increase in type 2 diabetes,” he explained.

The HeFH studies were supported by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kastelein reported having received consulting fees from those pharmaceutical companies and nearly two dozen others.

LONDON – The largest-ever treatment study of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia shows that the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab achieves “truly astounding” reductions in LDL cholesterol and atherogenic lipid particles through 78 weeks of follow-up, Dr. John J.P. Kastelein said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“These findings show reductions in LDL levels in these individuals that were completely impossible until now. Basically, this therapy in conjunction with statins and ezetimibe cures this genetic disease because LDL levels in these individuals are now lower than in the general population, which is, of course, something that we’ve never seen before,” said Dr. Kastelein, chairman of the department of vascular medicine at the University of Amsterdam.

Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) is the most common autosomal dominant genetic disorder, with an estimated prevalence worldwide of 1 in 200 in the general population. The associated highly elevated LDL levels bring a markedly increased risk of premature cardiovascular events. Only about 20% of patients with HeFH are able to achieve an LDL of 100 mg/dL or less despite maximum-tolerated doses of statins plus ezetimibe (Vytorin).

Dr. Kastelein presented the 78-week lipid-lowering results from four phase III randomized, double-blind clinical trials involving 1,257 HeFH patients unable to attain LDL goals despite maximum-tolerated statin therapy, typically supplemented with ezetimibe.

Participants were randomly assigned 2:1 to biweekly subcutaneous injections of alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) or placebo on top of background maximum tolerated statin therapy, usually accompanied by ezetimibe. The ODYSSEY FH I and FH II studies included 735 patients, with the alirocumab group starting on the PCSK9 inhibitor at 75 mg every 2 weeks, with the dose being doubled to 150 mg at 24 weeks in patients who hadn’t achieved an LDL level of 70 mg/dL or less at that point. The 522 HeFH patients in the ODYSSEY Long-Term study and the HIGH FH trial had higher baseline LDL levels and greater cardiovascular risk, and they therefore were on alirocumab at 150 mg every 2 weeks or placebo from the outset.

Fifty percent of alirocumab-treated patients in the FH I and II studies and 63% in the other two trials achieved an LDL level below 70 mg/dL at week 24, as did 0.6% and 1% of control patients, respectively. Dr. Kastelein characterized that as a jaw-dropping result.

“I have seen very few HeFH patients in my clinic – which is one of the largest in the world in terms of numbers of patients – who reached the goal of an LDL below 70 mg/dL,” he commented.

The outcomes in terms of secondary lipid endpoints provided an added bonus.

Absolutely no tachyphylaxis or return toward baseline LDL occurred over the course of 78 weeks of treatment, Dr. Kastelein continued.

The safety performance of alirocumab was highly reassuring: Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 3.9% of 837 alirocumab-treated patients and 3.6% on placebo. Overall, there was no significant difference between the two groups in rates of headache, musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders, infections, injection-site reactions, adjudicated cardiovascular events, allergic reactions, neurocognitive disorders, elevated liver enzymes, or any other safety endpoint.

Both alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha), another PCSK9 inhibitor, have been approved for the treatment of familial hypercholesterolemia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European regulators.

The next round of PCSK9 inhibitor studies, now ongoing, involves enrolling 70,000 subjects at increased cardiovascular risk in order to assess whether the level of LDL lowering achieved with these novel agents translates into a reduction in cardiovascular events.

Session cochair Dr. Barbara Casadei, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford (England), posed a question: Statin therapy has been shown to increase the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes – how about the PCSK9 inhibitors?

Dr. Kastelein replied that he recently published a study of more than 25,000 Dutch individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia and showed that their prevalence of type 2 diabetes was significantly lower than in their unaffected relatives (JAMA 2015 Mar 10;313[10]:1029-36).

“One of my theories is that the PCSK9 inhibitors reduce the number of LDL receptors on beta cells in the pancreas, so there’s less cholesterol influx, and since cholesterol is toxic to beta cells, the beta cells of PCSK9-inhibitor-treated patients live longer and therefore these individuals will have less type 2 diabetes. Statins do exactly the opposite: They up-regulate LDL receptors, so there will be more cholesterol coming into the beta cell and the theory is that this will result in an increase in type 2 diabetes,” he explained.

The HeFH studies were supported by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kastelein reported having received consulting fees from those pharmaceutical companies and nearly two dozen others.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: The PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab lowers LDL cholesterol to unprecedented levels patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia.

Major finding: Of patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia with unacceptably high LDL levels despite intensive conventional lipid-lowering agents, 56% achieved an LDL cholesterol below 70 mg/dL after 24 weeks of alirocumab, compared with 1% of placebo-treated controls.

Data source: This analysis included 1,257 individuals with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in four phase III, randomized, double-blind clinical trials who were randomized 2-to-1 to alirocumab or placebo plus background maximally tolerated conventional lipid-lowering medications and followed prospectively for 78 weeks.

Disclosures: The studies were supported by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kastelein reported having received consulting fees from those pharmaceutical companies and nearly two dozen others.

ESC: Noncardiac surgery in HCM patients warrants special attention

LONDON – Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients undergoing noncardiac surgery posted significantly worse 30-day composite outcomes than did closely matched controls undergoing the same sorts of surgical procedures.

“Our recommendation is that when hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients need noncardiac surgery they should be evaluated and treated at an experienced center,” Dr. Milind Y. Desai concluded at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

There is a dearth of data on outcomes of noncardiac surgery in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). This was the impetus for Dr. Desai and his coinvestigators at the Cleveland Clinic to conduct a case-control study involving 92 consecutive adults with HCM undergoing intermediate- or high-cardiovascular-risk noncardiac surgery and 184 controls matched for age, gender, and type of surgery. Enrollment was restricted to HCM patients who hadn’t previously undergone septal myectomy or alcohol ablation.

The primary outcome was the 30-day composite of postoperative death, MI, stroke, or heart failure. The incidence was 10% in the HCM group, significantly greater than the 3% rate in controls. Moreover, 4% of HCM patients developed postoperative atrial fibrillation, compared with none of the controls. Three deaths occurred among the 92 HCM patients, an incidence twice that in the control group.

The special challenge of noncardiac surgery in HCM patients is that their heart condition is characterized by systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, diastolic dysfunction, and mitral regurgitation. The rapid blood pressure and fluid shifts that occur during noncardiac surgery require special attention in such patients, Dr. Desai observed.

The HCM patients in this series received such attention, he added. They were more likely than controls to be on beta-blocker therapy at surgery, they received lower doses of ephedrine intraoperatively so as to avoid aggravating outflow tract obstruction, and they spent half as much time as controls with a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg or a heart rate greater than 100 bpm.

“Care was taken to make sure these patients did not decompensate,” he noted.

Dr. Desai reported no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LONDON – Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients undergoing noncardiac surgery posted significantly worse 30-day composite outcomes than did closely matched controls undergoing the same sorts of surgical procedures.

“Our recommendation is that when hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients need noncardiac surgery they should be evaluated and treated at an experienced center,” Dr. Milind Y. Desai concluded at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

There is a dearth of data on outcomes of noncardiac surgery in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). This was the impetus for Dr. Desai and his coinvestigators at the Cleveland Clinic to conduct a case-control study involving 92 consecutive adults with HCM undergoing intermediate- or high-cardiovascular-risk noncardiac surgery and 184 controls matched for age, gender, and type of surgery. Enrollment was restricted to HCM patients who hadn’t previously undergone septal myectomy or alcohol ablation.

The primary outcome was the 30-day composite of postoperative death, MI, stroke, or heart failure. The incidence was 10% in the HCM group, significantly greater than the 3% rate in controls. Moreover, 4% of HCM patients developed postoperative atrial fibrillation, compared with none of the controls. Three deaths occurred among the 92 HCM patients, an incidence twice that in the control group.

The special challenge of noncardiac surgery in HCM patients is that their heart condition is characterized by systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, diastolic dysfunction, and mitral regurgitation. The rapid blood pressure and fluid shifts that occur during noncardiac surgery require special attention in such patients, Dr. Desai observed.

The HCM patients in this series received such attention, he added. They were more likely than controls to be on beta-blocker therapy at surgery, they received lower doses of ephedrine intraoperatively so as to avoid aggravating outflow tract obstruction, and they spent half as much time as controls with a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg or a heart rate greater than 100 bpm.

“Care was taken to make sure these patients did not decompensate,” he noted.

Dr. Desai reported no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

LONDON – Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients undergoing noncardiac surgery posted significantly worse 30-day composite outcomes than did closely matched controls undergoing the same sorts of surgical procedures.

“Our recommendation is that when hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients need noncardiac surgery they should be evaluated and treated at an experienced center,” Dr. Milind Y. Desai concluded at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

There is a dearth of data on outcomes of noncardiac surgery in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). This was the impetus for Dr. Desai and his coinvestigators at the Cleveland Clinic to conduct a case-control study involving 92 consecutive adults with HCM undergoing intermediate- or high-cardiovascular-risk noncardiac surgery and 184 controls matched for age, gender, and type of surgery. Enrollment was restricted to HCM patients who hadn’t previously undergone septal myectomy or alcohol ablation.

The primary outcome was the 30-day composite of postoperative death, MI, stroke, or heart failure. The incidence was 10% in the HCM group, significantly greater than the 3% rate in controls. Moreover, 4% of HCM patients developed postoperative atrial fibrillation, compared with none of the controls. Three deaths occurred among the 92 HCM patients, an incidence twice that in the control group.

The special challenge of noncardiac surgery in HCM patients is that their heart condition is characterized by systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, diastolic dysfunction, and mitral regurgitation. The rapid blood pressure and fluid shifts that occur during noncardiac surgery require special attention in such patients, Dr. Desai observed.

The HCM patients in this series received such attention, he added. They were more likely than controls to be on beta-blocker therapy at surgery, they received lower doses of ephedrine intraoperatively so as to avoid aggravating outflow tract obstruction, and they spent half as much time as controls with a systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg or a heart rate greater than 100 bpm.

“Care was taken to make sure these patients did not decompensate,” he noted.

Dr. Desai reported no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients undergoing noncardiac surgery have significantly worse outcomes than do matched controls undergoing similar operations.

Major finding: The 30-day composite endpoint of death, MI, stroke, or heart failure occurred in 10% of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients who underwent noncardiac surgery, compared with 3% of matched controls.

Data source: A case-control study comparing 30-day outcomes in 92 consecutive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients undergoing intermediate- or high-cardiovascular-risk noncardiac surgery and 184 matched controls.

Disclosures: This study was conducted free of commercial support, and the presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

ESC: Nonobstructive CAD spells below-average mortality

LONDON – Patients with stable angina pectoris who are found to have no obstructive coronary artery disease upon diagnostic coronary angiography actually have significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality and acute MI over the next 7 years than the age- and gender-matched general population, according to a large Danish registry study.

“This is a novel finding that’s never been reported before,” Dr. Kris K. Olesen noted in presenting the results at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

His retrospective, population-based cohort study of patients in the Western Denmark Heart Registry who were referred for diagnostic coronary angiography during 2003-2012 included nearly 40,000 individuals with stable angina pectoris who were found on elective coronary angiography to have no obstructive CAD, meaning no lesions involving 50% or greater luminal narrowing. They were compared to the age- and gender-matched general western Danish population without a history of ischemic heart disease.

The upshot: Individuals without angiographic obstructive CAD had an absolute 1.61% lower rate of all-cause mortality, compared with the general western Danish population, during a median 3.9 and maximum 7 years of follow-up. They also had an absolute 0.41% lower risk of acute MI. After adjustment for comorbid conditions, this translated to a 39% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality and a 41% reduction in MI risk, with both results being statistically significant with P values of less than 0.0001, reported Dr. Olesen of Aahus (Denmark) University.

One possible explanation for these surprising results, he said, is that patients with stable angina who elect to undergo diagnostic angiography are more health-aware than the general population and take better care of themselves. Another factor is that the general population with no history of ischemic heart disease probably includes individuals with significant CAD and chest pain who have never sought medical attention; they would drive up rates of MI and all-cause mortality in the comparison group.

Discussant Dr. Elmir Omerovic of the University of Goteborg (Sweden) offered up another possibility: Patients without obstructive CAD avoid percutaneous coronary intervention and are thereby spared the risks associated with an invasive procedure, including the hazard of serious bleeding events due to dual antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. Olesen reported having no financial conflicts with regard to this study, conducted with institutional funds.

LONDON – Patients with stable angina pectoris who are found to have no obstructive coronary artery disease upon diagnostic coronary angiography actually have significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality and acute MI over the next 7 years than the age- and gender-matched general population, according to a large Danish registry study.

“This is a novel finding that’s never been reported before,” Dr. Kris K. Olesen noted in presenting the results at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

His retrospective, population-based cohort study of patients in the Western Denmark Heart Registry who were referred for diagnostic coronary angiography during 2003-2012 included nearly 40,000 individuals with stable angina pectoris who were found on elective coronary angiography to have no obstructive CAD, meaning no lesions involving 50% or greater luminal narrowing. They were compared to the age- and gender-matched general western Danish population without a history of ischemic heart disease.

The upshot: Individuals without angiographic obstructive CAD had an absolute 1.61% lower rate of all-cause mortality, compared with the general western Danish population, during a median 3.9 and maximum 7 years of follow-up. They also had an absolute 0.41% lower risk of acute MI. After adjustment for comorbid conditions, this translated to a 39% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality and a 41% reduction in MI risk, with both results being statistically significant with P values of less than 0.0001, reported Dr. Olesen of Aahus (Denmark) University.

One possible explanation for these surprising results, he said, is that patients with stable angina who elect to undergo diagnostic angiography are more health-aware than the general population and take better care of themselves. Another factor is that the general population with no history of ischemic heart disease probably includes individuals with significant CAD and chest pain who have never sought medical attention; they would drive up rates of MI and all-cause mortality in the comparison group.

Discussant Dr. Elmir Omerovic of the University of Goteborg (Sweden) offered up another possibility: Patients without obstructive CAD avoid percutaneous coronary intervention and are thereby spared the risks associated with an invasive procedure, including the hazard of serious bleeding events due to dual antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. Olesen reported having no financial conflicts with regard to this study, conducted with institutional funds.

LONDON – Patients with stable angina pectoris who are found to have no obstructive coronary artery disease upon diagnostic coronary angiography actually have significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality and acute MI over the next 7 years than the age- and gender-matched general population, according to a large Danish registry study.

“This is a novel finding that’s never been reported before,” Dr. Kris K. Olesen noted in presenting the results at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

His retrospective, population-based cohort study of patients in the Western Denmark Heart Registry who were referred for diagnostic coronary angiography during 2003-2012 included nearly 40,000 individuals with stable angina pectoris who were found on elective coronary angiography to have no obstructive CAD, meaning no lesions involving 50% or greater luminal narrowing. They were compared to the age- and gender-matched general western Danish population without a history of ischemic heart disease.

The upshot: Individuals without angiographic obstructive CAD had an absolute 1.61% lower rate of all-cause mortality, compared with the general western Danish population, during a median 3.9 and maximum 7 years of follow-up. They also had an absolute 0.41% lower risk of acute MI. After adjustment for comorbid conditions, this translated to a 39% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality and a 41% reduction in MI risk, with both results being statistically significant with P values of less than 0.0001, reported Dr. Olesen of Aahus (Denmark) University.

One possible explanation for these surprising results, he said, is that patients with stable angina who elect to undergo diagnostic angiography are more health-aware than the general population and take better care of themselves. Another factor is that the general population with no history of ischemic heart disease probably includes individuals with significant CAD and chest pain who have never sought medical attention; they would drive up rates of MI and all-cause mortality in the comparison group.

Discussant Dr. Elmir Omerovic of the University of Goteborg (Sweden) offered up another possibility: Patients without obstructive CAD avoid percutaneous coronary intervention and are thereby spared the risks associated with an invasive procedure, including the hazard of serious bleeding events due to dual antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. Olesen reported having no financial conflicts with regard to this study, conducted with institutional funds.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Rates of acute MI and all-cause mortality in patients with stable angina pectoris but no obstructive CAD are significantly lower than in the general population.

Major finding: Danish adults with stable angina pectoris but no obstructive CAD upon diagnostic coronary angiography had a 41% lower risk of acute MI and a 39% relative risk reduction in all-cause mortality compared with the age- and gender-matched general Danish population.

Data source: This retrospective population-based cohort study included nearly 40,000 Danish adults with stable angina pectoris who upon elective coronary angiography were found to have no obstructive CAD.

Disclosures: The study was supported by institutional funds. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

ESC: Heart failure risk climbs early in childhood cancer survivors

LONDON – Childhood cancer survivors face an increased risk of developing heart failure starting at a much younger age than the cardiac disease typically appears, according to a Dutch national cohort study.

“Health care professionals need to be aware of these findings and recognize the risk of developing heart failure in young people, even years after their childhood cancer treatment,” Dr. Elizabeth A.M. Feijen advised at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She presented an analysis from the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group LATER (Late Effects of Childhood Cancer) study which entailed collecting followup data on more than 5,000 Dutch 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. After a median followup of 20 years, and at an average age of 27.4 years, 2% of the national cohort had been diagnosed with heart failure.

Of 113 childhood cancer survivors with heart failure, 9 had undergone heart transplantation, 11 required a pacemaker and/or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and 22 had died due to their heart failure, reported Dr. Feijen of the Academic Medical Center of Amsterdam.

The cumulative incidence of heart failure was 1.1% by age 20, 2.3% by age 30, 3.9% by age 40, and 5.4% by 50 years of age.

In a multivariate regression analysis, the significant risk factors for heart failure after childhood cancer were treatment with anthracyclines, with an associated 1.8-fold increased risk per 100 mg/m2 of medication; mitoxantrone, with a 2.3-fold risk per 25 mg/m2; chest radiation to the heart, with a 1.9-fold risk; and the use of cyclophosphamide, with an associated 1.8-fold increased risk of subsequent heart failure.

The DCOG LATER study is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society and the Children Cancer Free Foundation. Dr. Feijen reported having no financial conflicts.

LONDON – Childhood cancer survivors face an increased risk of developing heart failure starting at a much younger age than the cardiac disease typically appears, according to a Dutch national cohort study.

“Health care professionals need to be aware of these findings and recognize the risk of developing heart failure in young people, even years after their childhood cancer treatment,” Dr. Elizabeth A.M. Feijen advised at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She presented an analysis from the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group LATER (Late Effects of Childhood Cancer) study which entailed collecting followup data on more than 5,000 Dutch 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. After a median followup of 20 years, and at an average age of 27.4 years, 2% of the national cohort had been diagnosed with heart failure.

Of 113 childhood cancer survivors with heart failure, 9 had undergone heart transplantation, 11 required a pacemaker and/or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and 22 had died due to their heart failure, reported Dr. Feijen of the Academic Medical Center of Amsterdam.

The cumulative incidence of heart failure was 1.1% by age 20, 2.3% by age 30, 3.9% by age 40, and 5.4% by 50 years of age.

In a multivariate regression analysis, the significant risk factors for heart failure after childhood cancer were treatment with anthracyclines, with an associated 1.8-fold increased risk per 100 mg/m2 of medication; mitoxantrone, with a 2.3-fold risk per 25 mg/m2; chest radiation to the heart, with a 1.9-fold risk; and the use of cyclophosphamide, with an associated 1.8-fold increased risk of subsequent heart failure.

The DCOG LATER study is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society and the Children Cancer Free Foundation. Dr. Feijen reported having no financial conflicts.

LONDON – Childhood cancer survivors face an increased risk of developing heart failure starting at a much younger age than the cardiac disease typically appears, according to a Dutch national cohort study.

“Health care professionals need to be aware of these findings and recognize the risk of developing heart failure in young people, even years after their childhood cancer treatment,” Dr. Elizabeth A.M. Feijen advised at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She presented an analysis from the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group LATER (Late Effects of Childhood Cancer) study which entailed collecting followup data on more than 5,000 Dutch 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. After a median followup of 20 years, and at an average age of 27.4 years, 2% of the national cohort had been diagnosed with heart failure.

Of 113 childhood cancer survivors with heart failure, 9 had undergone heart transplantation, 11 required a pacemaker and/or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and 22 had died due to their heart failure, reported Dr. Feijen of the Academic Medical Center of Amsterdam.

The cumulative incidence of heart failure was 1.1% by age 20, 2.3% by age 30, 3.9% by age 40, and 5.4% by 50 years of age.

In a multivariate regression analysis, the significant risk factors for heart failure after childhood cancer were treatment with anthracyclines, with an associated 1.8-fold increased risk per 100 mg/m2 of medication; mitoxantrone, with a 2.3-fold risk per 25 mg/m2; chest radiation to the heart, with a 1.9-fold risk; and the use of cyclophosphamide, with an associated 1.8-fold increased risk of subsequent heart failure.

The DCOG LATER study is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society and the Children Cancer Free Foundation. Dr. Feijen reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Survivors of childhood cancer face a risk of developing heart failure that grows with time but is already elevated by age 20.

Major finding: The cumulative incidence of heart failure in survivors of childhood cancer is 1.1% by age 20, 2.3% by age 30, and 3.9% by age 40 years.

Data source: This was a national study of more than 5,000 Dutch 5-year survivors of childhood cancer who were followed for a median of 20.2 years.

Disclosures: The DCOG LATER study is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society and the Children Cancer Free Foundation. he presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

ESC: Atrial fibrillation accelerates brain atrophy

LONDON – Atrial fibrillation in the elderly general population was independently associated with accelerated losses of brain volume and cognitive function in a major longitudinal study.

These findings from the population-based Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study (AGES-Reykjavik) have the potential to change the management of atrial fibrillation (AF), Dr. David O. Arnar said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“I think these data potentially suggest it’s better for the brain to remain in sinus rhythm than to pursue rate control in AF. We also have other studies, postablation studies, that show doing an ablation procedure to restore sinus rhythm delays the onset of cognitive dysfunction. So I think we have more and more data that are suggesting AF may be bad for the brain in more ways than just causing cerebral infarcts. That possibility needs to be considered as an endpoint in future studies of treatment strategies,” asserted Dr. Arnar, a cardiologist at Landspítali–The National University Hospital of Iceland, Reykjavik.

The AGES-Reykjavik Study is an ongoing project designed to investigate the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to clinical and subclinical diseases in older-age individuals.

The new data Dr. Arnar presented are an outgrowth of an earlier report from AGES-Reykjavik, which concluded that AF was associated with smaller brain volume and diminished cognitive performance independent of cerebral infarcts. The observed deficits were smallest in subjects with no history of AF, larger in those with paroxysmal AF, and largest of all in participants with persistent/permanent AF (Stroke. 2013 Apr;44[4]:1020-5). However, this was a cross-sectional analysis, which by definition doesn’t permit drawing conclusions regarding cause and effect.

That earlier report was the impetus for the new study featuring a mean of 5.2 years of longitudinal follow-up. The study included 2,472 elderly, nondemented subjects with a mean baseline age of 76 years who underwent brain MRIs and structured cognitive function testing, with repeated assessments roughly a half-decade later.

A total of 121 subjects had ECG-confirmed AF or a history of AF at entry. Another 132 developed new-onset AF during follow-up. Since the participants with prevalent or incident AF had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors, alcohol consumption, history of cerebral infarcts, and other potential confounders, extensive multivariate statistical adjustments were required in analyzing the data, according to the cardiologist.

During the follow-up period, the AF-free subjects experienced a mean 1.8% reduction in gray matter volume, compared with a 2.7% decrease in individuals with prevalent AF and a 3.88% reduction in those with incident AF. All differences were statistically significant.

Loss of white matter volume over time followed a similar pattern: a mean loss of 5.35% in the no-AF group, compared with a 5.5% drop in those with prevalent AF and a 6.56% decrease in individuals with incident AF.

The volume of white matter lesions rose by 31.6% in the elderly no-AF group, 26.9% in those with prevalent AF, and 43.5% in subjects with new-onset AF during follow-up.

“It surprised us that the changes were most pronounced in those with incident AF rather than prevalent AF,” Dr. Arnar confessed. “How do we explain that? Well, I don’t know, but you wonder if the effect of AF on the brain could be most pronounced initially and then as AF goes on, an adaptation process occurs so that the rate of change in the brain becomes less pronounced as the AF becomes more chronic.”

Turning to the results of cognitive function testing, a composite measure of processing speed declined over time by 10% in the no-AF group, 12.7% with prevalent AF, and 13.9% with incident AF. All differences were statistically significant.

The rate of decline in executive function was 8% in the no-AF subjects, 10.2% with prevalent AF, and 11.8% with incident AF.

Similarly, scores on memory testing dropped by 9.3% in the no-AF group, 9.9% with prevalent AF, and 11.9% with incident AF.

The mechanism by which AF accelerates brain aging is unknown. Dr. Arnar strongly suspects it is multifactorial, with candidate processes including altered autonomic regulation of blood flow, microemboli causing brain atrophy, and most assuredly AF-induced diminution of cerebral blood flow.

He presented cerebral blood flow data obtained via phase contrast MRI on 2,125 study participants. Those with no history of AF averaged a total cerebral blood flow of 540 mL/min. Subjects with a history of AF who were in sinus rhythm at the time of the brain scan averaged 520 mL/min. And subjects in AF when they were scanned averaged less than 480 mL/min.

Dr. Arnar also presented preliminary results from an ongoing brain perfusion imaging study conducted in AF patients before and after direct current cardioversion. Among 17 patients who responded to cardioversion by going into sinus rhythm and staying there for at least 10 weeks until their follow-up MRI, total cerebral blood flow improved by a mean of 70 mL/min from a precardioversion figure of 557 mL/min. Both white and gray matter perfusion improved by a mean of 16%.

In contrast, the 10 patients who remained in AF despite the cardioversion attempt showed no improvement in any of these three endpoints over the 10 weeks.

Audience members wondered whether being on warfarin or beta blocker therapy affected the rate of brain volume loss or cognitive function. Not in the cross-sectional study published in Stroke, Dr. Arnar replied. However, those analyses have yet to be conducted in the new longitudinal study.

The AGES-Reykjavik Study is funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Icelandic Heart Association, and the Icelandic Parliament. Dr. Arnar reported having no financial conflicts.

LONDON – Atrial fibrillation in the elderly general population was independently associated with accelerated losses of brain volume and cognitive function in a major longitudinal study.

These findings from the population-based Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study (AGES-Reykjavik) have the potential to change the management of atrial fibrillation (AF), Dr. David O. Arnar said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“I think these data potentially suggest it’s better for the brain to remain in sinus rhythm than to pursue rate control in AF. We also have other studies, postablation studies, that show doing an ablation procedure to restore sinus rhythm delays the onset of cognitive dysfunction. So I think we have more and more data that are suggesting AF may be bad for the brain in more ways than just causing cerebral infarcts. That possibility needs to be considered as an endpoint in future studies of treatment strategies,” asserted Dr. Arnar, a cardiologist at Landspítali–The National University Hospital of Iceland, Reykjavik.

The AGES-Reykjavik Study is an ongoing project designed to investigate the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to clinical and subclinical diseases in older-age individuals.

The new data Dr. Arnar presented are an outgrowth of an earlier report from AGES-Reykjavik, which concluded that AF was associated with smaller brain volume and diminished cognitive performance independent of cerebral infarcts. The observed deficits were smallest in subjects with no history of AF, larger in those with paroxysmal AF, and largest of all in participants with persistent/permanent AF (Stroke. 2013 Apr;44[4]:1020-5). However, this was a cross-sectional analysis, which by definition doesn’t permit drawing conclusions regarding cause and effect.

That earlier report was the impetus for the new study featuring a mean of 5.2 years of longitudinal follow-up. The study included 2,472 elderly, nondemented subjects with a mean baseline age of 76 years who underwent brain MRIs and structured cognitive function testing, with repeated assessments roughly a half-decade later.

A total of 121 subjects had ECG-confirmed AF or a history of AF at entry. Another 132 developed new-onset AF during follow-up. Since the participants with prevalent or incident AF had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors, alcohol consumption, history of cerebral infarcts, and other potential confounders, extensive multivariate statistical adjustments were required in analyzing the data, according to the cardiologist.

During the follow-up period, the AF-free subjects experienced a mean 1.8% reduction in gray matter volume, compared with a 2.7% decrease in individuals with prevalent AF and a 3.88% reduction in those with incident AF. All differences were statistically significant.

Loss of white matter volume over time followed a similar pattern: a mean loss of 5.35% in the no-AF group, compared with a 5.5% drop in those with prevalent AF and a 6.56% decrease in individuals with incident AF.

The volume of white matter lesions rose by 31.6% in the elderly no-AF group, 26.9% in those with prevalent AF, and 43.5% in subjects with new-onset AF during follow-up.

“It surprised us that the changes were most pronounced in those with incident AF rather than prevalent AF,” Dr. Arnar confessed. “How do we explain that? Well, I don’t know, but you wonder if the effect of AF on the brain could be most pronounced initially and then as AF goes on, an adaptation process occurs so that the rate of change in the brain becomes less pronounced as the AF becomes more chronic.”

Turning to the results of cognitive function testing, a composite measure of processing speed declined over time by 10% in the no-AF group, 12.7% with prevalent AF, and 13.9% with incident AF. All differences were statistically significant.

The rate of decline in executive function was 8% in the no-AF subjects, 10.2% with prevalent AF, and 11.8% with incident AF.

Similarly, scores on memory testing dropped by 9.3% in the no-AF group, 9.9% with prevalent AF, and 11.9% with incident AF.

The mechanism by which AF accelerates brain aging is unknown. Dr. Arnar strongly suspects it is multifactorial, with candidate processes including altered autonomic regulation of blood flow, microemboli causing brain atrophy, and most assuredly AF-induced diminution of cerebral blood flow.

He presented cerebral blood flow data obtained via phase contrast MRI on 2,125 study participants. Those with no history of AF averaged a total cerebral blood flow of 540 mL/min. Subjects with a history of AF who were in sinus rhythm at the time of the brain scan averaged 520 mL/min. And subjects in AF when they were scanned averaged less than 480 mL/min.

Dr. Arnar also presented preliminary results from an ongoing brain perfusion imaging study conducted in AF patients before and after direct current cardioversion. Among 17 patients who responded to cardioversion by going into sinus rhythm and staying there for at least 10 weeks until their follow-up MRI, total cerebral blood flow improved by a mean of 70 mL/min from a precardioversion figure of 557 mL/min. Both white and gray matter perfusion improved by a mean of 16%.

In contrast, the 10 patients who remained in AF despite the cardioversion attempt showed no improvement in any of these three endpoints over the 10 weeks.

Audience members wondered whether being on warfarin or beta blocker therapy affected the rate of brain volume loss or cognitive function. Not in the cross-sectional study published in Stroke, Dr. Arnar replied. However, those analyses have yet to be conducted in the new longitudinal study.

The AGES-Reykjavik Study is funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Icelandic Heart Association, and the Icelandic Parliament. Dr. Arnar reported having no financial conflicts.

LONDON – Atrial fibrillation in the elderly general population was independently associated with accelerated losses of brain volume and cognitive function in a major longitudinal study.

These findings from the population-based Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study (AGES-Reykjavik) have the potential to change the management of atrial fibrillation (AF), Dr. David O. Arnar said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“I think these data potentially suggest it’s better for the brain to remain in sinus rhythm than to pursue rate control in AF. We also have other studies, postablation studies, that show doing an ablation procedure to restore sinus rhythm delays the onset of cognitive dysfunction. So I think we have more and more data that are suggesting AF may be bad for the brain in more ways than just causing cerebral infarcts. That possibility needs to be considered as an endpoint in future studies of treatment strategies,” asserted Dr. Arnar, a cardiologist at Landspítali–The National University Hospital of Iceland, Reykjavik.

The AGES-Reykjavik Study is an ongoing project designed to investigate the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to clinical and subclinical diseases in older-age individuals.

The new data Dr. Arnar presented are an outgrowth of an earlier report from AGES-Reykjavik, which concluded that AF was associated with smaller brain volume and diminished cognitive performance independent of cerebral infarcts. The observed deficits were smallest in subjects with no history of AF, larger in those with paroxysmal AF, and largest of all in participants with persistent/permanent AF (Stroke. 2013 Apr;44[4]:1020-5). However, this was a cross-sectional analysis, which by definition doesn’t permit drawing conclusions regarding cause and effect.

That earlier report was the impetus for the new study featuring a mean of 5.2 years of longitudinal follow-up. The study included 2,472 elderly, nondemented subjects with a mean baseline age of 76 years who underwent brain MRIs and structured cognitive function testing, with repeated assessments roughly a half-decade later.

A total of 121 subjects had ECG-confirmed AF or a history of AF at entry. Another 132 developed new-onset AF during follow-up. Since the participants with prevalent or incident AF had significantly higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors, alcohol consumption, history of cerebral infarcts, and other potential confounders, extensive multivariate statistical adjustments were required in analyzing the data, according to the cardiologist.

During the follow-up period, the AF-free subjects experienced a mean 1.8% reduction in gray matter volume, compared with a 2.7% decrease in individuals with prevalent AF and a 3.88% reduction in those with incident AF. All differences were statistically significant.

Loss of white matter volume over time followed a similar pattern: a mean loss of 5.35% in the no-AF group, compared with a 5.5% drop in those with prevalent AF and a 6.56% decrease in individuals with incident AF.

The volume of white matter lesions rose by 31.6% in the elderly no-AF group, 26.9% in those with prevalent AF, and 43.5% in subjects with new-onset AF during follow-up.

“It surprised us that the changes were most pronounced in those with incident AF rather than prevalent AF,” Dr. Arnar confessed. “How do we explain that? Well, I don’t know, but you wonder if the effect of AF on the brain could be most pronounced initially and then as AF goes on, an adaptation process occurs so that the rate of change in the brain becomes less pronounced as the AF becomes more chronic.”

Turning to the results of cognitive function testing, a composite measure of processing speed declined over time by 10% in the no-AF group, 12.7% with prevalent AF, and 13.9% with incident AF. All differences were statistically significant.

The rate of decline in executive function was 8% in the no-AF subjects, 10.2% with prevalent AF, and 11.8% with incident AF.

Similarly, scores on memory testing dropped by 9.3% in the no-AF group, 9.9% with prevalent AF, and 11.9% with incident AF.

The mechanism by which AF accelerates brain aging is unknown. Dr. Arnar strongly suspects it is multifactorial, with candidate processes including altered autonomic regulation of blood flow, microemboli causing brain atrophy, and most assuredly AF-induced diminution of cerebral blood flow.

He presented cerebral blood flow data obtained via phase contrast MRI on 2,125 study participants. Those with no history of AF averaged a total cerebral blood flow of 540 mL/min. Subjects with a history of AF who were in sinus rhythm at the time of the brain scan averaged 520 mL/min. And subjects in AF when they were scanned averaged less than 480 mL/min.

Dr. Arnar also presented preliminary results from an ongoing brain perfusion imaging study conducted in AF patients before and after direct current cardioversion. Among 17 patients who responded to cardioversion by going into sinus rhythm and staying there for at least 10 weeks until their follow-up MRI, total cerebral blood flow improved by a mean of 70 mL/min from a precardioversion figure of 557 mL/min. Both white and gray matter perfusion improved by a mean of 16%.

In contrast, the 10 patients who remained in AF despite the cardioversion attempt showed no improvement in any of these three endpoints over the 10 weeks.

Audience members wondered whether being on warfarin or beta blocker therapy affected the rate of brain volume loss or cognitive function. Not in the cross-sectional study published in Stroke, Dr. Arnar replied. However, those analyses have yet to be conducted in the new longitudinal study.

The AGES-Reykjavik Study is funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Icelandic Heart Association, and the Icelandic Parliament. Dr. Arnar reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Atrial fibrillation appears to accelerate brain aging in the elderly independent of cerebral embolism.

Major finding: Both prevalent and incident atrial fibrillation were associated with accelerated loss of gray matter and total brain volume as well as key aspects of cognitive function.

Data source: This population-based study included 2,472 nondemented participants with a mean baseline age of 76 years who were prospectively followed with brain scans and structured cognitive function tests for a mean of 5.2 years.

Disclosures: The AGES-Reykjavik Study is funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Icelandic Heart Association, and the Icelandic Parliament. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

ESC: Zero risk of death in pregnant women with severe aortic stenosis

LONDON – The mortality risk for pregnant women with moderate or severe aortic stenosis is close to zero in contemporary practice, according to data from the large, international ROPAC registry.

That being said, more than one-third of women with severe aortic stenosis will require hospitalization for cardiac reasons during their pregnancy, with heart failure the number-one cause for admission, Dr. Stefan Orwat reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Severe fetal complications are rare. However, preterm birth, small for gestational age, and neonatal Apgar scores below 7 are quite common in pregnancies involving severe aortic stenosis, as defined by a prepregnancy transaortic peak gradient of 64 mm Hg or more, according to Dr. Orwat of University Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

ROPAC (the Registry on Pregnancy and Cardiac disease) is a unique ongoing, global, prospective, observational registry created in order to advance understanding of the risks of pregnancy in the setting of structural heart disease. Prior reports from other sources have often provided conflicting guidance because of relatively small patient sample sizes. That’s been especially true with regard to aortic stenosis (AS), the cardiologist said.

Out of 2,966 pregnancies in women with various forms of structural heart disease in ROPAC, Dr. Orwat focused on the 99 pregnancies in 96 women with moderate or severe AS, 21 of whom had a prosthetic heart valve in place prior to pregnancy; 65 of the women had moderate AS as evidenced by an echocardiographic prepregnancy peak gradient of 36-63 mm Hg.

No maternal deaths occurred during pregnancy or within 1 week afterward. However, 13% of women with moderate AS and 35% with severe AS were hospitalized for cardiac reasons during their pregnancy. Most of the admissions were for new or worsening heart failure, which occurred at a median of 28 weeks’ gestation.

The risk of heart failure hospitalization during pregnancy was quite low – in the 6%-8% range – among women with baseline prepregnancy asymptomatic or symptomatic moderate AS or asymptomatic severe AS. In contrast, the rate shot up to 26% in women with symptomatic and severe AS prior to pregnancy.

There were a couple of hospitalizations for arrhythmias and one for endocarditis. Unlike in some prior reports by other research groups, there were no cases of pulmonary embolism, valve thrombosis, cerebrovascular events, or deep vein thrombosis. The presence of a mechanical valve with its required rigorous anticoagulation wasn’t related to worse outcomes in this series, unlike in some others.

The heart failure was generally manageable medically. Only two patients required intervention. One developed endocarditis, then underwent balloon aortic valvuloplasty and aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve 4 months into pregnancy, with subsequent vaginal delivery at 38 weeks. The other patient, who was unaware she had AS prior to pregnancy, presented with severe AS and a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction at 20 weeks’ gestation. She responded well to valvuloplasty, had an uneventful vaginal delivery at 38 weeks, then underwent aortic valve replacement.

In a multivariate analysis, only two independent predictors of maternal hospitalization during pregnancy were identified: the presence of symptoms prior to pregnancy, and the prepregnancy hemodynamic severity of AS.

Preterm birth prior to 37 weeks occurred in 16% of pregnancies involving moderate and 36% of those featuring severe AS. An Apgar score below 7 occurred in 5% of cases of moderate and 16% of severe AS. The small for gestational age rate was 3% with moderate AS and ballooned to 21% with severe AS. The only independent predictor of fetal complications was the degree of elevation in peak aortic gradient prior to pregnancy.

Audience questions focused on challenging scenarios. Would you allow a pregnancy to continue, Dr. Orwat was asked, if a woman with AS developed an aortic gradient of 90 mm Hg during the first trimester?

“It depends on whether she was asymptomatic prior to pregnancy. If so, I think it’s a low-risk situation, and you can carry on with the pregnancy,” he replied. Remember, he added, it’s the baseline gradient that’s important. Cardiac output goes up during the first trimester as a matter of course, and so will the gradient.

Dr. Orwat emphasized that symptomatic severe AS is an indication for aortic valve replacement, and he would advise an affected patient to undergo the surgery prior to pregnancy.

Audience member Dr. Fiona Walker rose to advocate ordering a prepregnancy treadmill exercise test in all patients with asymptomatic severe AS in order to learn whether they are likely to remain asymptomatic during the stresses of pregnancy. In a patient with severe AS who remains asymptomatic with exercise, it’s probably safer to go through pregnancy without prior valve replacement than to put in a mechanical valve.

“Patients with mechanical valves in pregnancy are one of the highest-risk groups we look after,” commented Dr. Walker, head of the maternal cardiology program at University College London Hospitals.

But another audience member advocated aortic valve replacement prior to pregnancy in all women with severe AS, asymptomatic or not.

“Nowadays, if you are afraid of a mechanical valve, you can put in a bioprosthetic one, although I know that’s considered controversial. I see that asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis seems quite safe in ROPAC, but I still consider severe aortic stenosis one of the truly dangerous problems in pregnancy. Maybe I’ll change my mind after ROPAC is published, but right now I don’t think we’re going to leave a severe aortic stenosis prior to pregnancy without intervention,” declared Dr. Avraham Shotan, head of the Heart Institute at Hillel Yaffe Medical Center in Hadera, Israel.

Session cochair Dr. Christa Gohlke-Baerwolf of Bad Krozingen (Germany) Hospital mediated the dispute and closed discussion by observing, “Severe aortic stenosis is not just one thing, it’s a continuum, and such patients should be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team very carefully before starting pregnancy.“

ROPAC is sponsored by the ESC. Dr. Orwat reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

LONDON – The mortality risk for pregnant women with moderate or severe aortic stenosis is close to zero in contemporary practice, according to data from the large, international ROPAC registry.

That being said, more than one-third of women with severe aortic stenosis will require hospitalization for cardiac reasons during their pregnancy, with heart failure the number-one cause for admission, Dr. Stefan Orwat reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Severe fetal complications are rare. However, preterm birth, small for gestational age, and neonatal Apgar scores below 7 are quite common in pregnancies involving severe aortic stenosis, as defined by a prepregnancy transaortic peak gradient of 64 mm Hg or more, according to Dr. Orwat of University Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

ROPAC (the Registry on Pregnancy and Cardiac disease) is a unique ongoing, global, prospective, observational registry created in order to advance understanding of the risks of pregnancy in the setting of structural heart disease. Prior reports from other sources have often provided conflicting guidance because of relatively small patient sample sizes. That’s been especially true with regard to aortic stenosis (AS), the cardiologist said.

Out of 2,966 pregnancies in women with various forms of structural heart disease in ROPAC, Dr. Orwat focused on the 99 pregnancies in 96 women with moderate or severe AS, 21 of whom had a prosthetic heart valve in place prior to pregnancy; 65 of the women had moderate AS as evidenced by an echocardiographic prepregnancy peak gradient of 36-63 mm Hg.

No maternal deaths occurred during pregnancy or within 1 week afterward. However, 13% of women with moderate AS and 35% with severe AS were hospitalized for cardiac reasons during their pregnancy. Most of the admissions were for new or worsening heart failure, which occurred at a median of 28 weeks’ gestation.

The risk of heart failure hospitalization during pregnancy was quite low – in the 6%-8% range – among women with baseline prepregnancy asymptomatic or symptomatic moderate AS or asymptomatic severe AS. In contrast, the rate shot up to 26% in women with symptomatic and severe AS prior to pregnancy.

There were a couple of hospitalizations for arrhythmias and one for endocarditis. Unlike in some prior reports by other research groups, there were no cases of pulmonary embolism, valve thrombosis, cerebrovascular events, or deep vein thrombosis. The presence of a mechanical valve with its required rigorous anticoagulation wasn’t related to worse outcomes in this series, unlike in some others.

The heart failure was generally manageable medically. Only two patients required intervention. One developed endocarditis, then underwent balloon aortic valvuloplasty and aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve 4 months into pregnancy, with subsequent vaginal delivery at 38 weeks. The other patient, who was unaware she had AS prior to pregnancy, presented with severe AS and a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction at 20 weeks’ gestation. She responded well to valvuloplasty, had an uneventful vaginal delivery at 38 weeks, then underwent aortic valve replacement.

In a multivariate analysis, only two independent predictors of maternal hospitalization during pregnancy were identified: the presence of symptoms prior to pregnancy, and the prepregnancy hemodynamic severity of AS.

Preterm birth prior to 37 weeks occurred in 16% of pregnancies involving moderate and 36% of those featuring severe AS. An Apgar score below 7 occurred in 5% of cases of moderate and 16% of severe AS. The small for gestational age rate was 3% with moderate AS and ballooned to 21% with severe AS. The only independent predictor of fetal complications was the degree of elevation in peak aortic gradient prior to pregnancy.

Audience questions focused on challenging scenarios. Would you allow a pregnancy to continue, Dr. Orwat was asked, if a woman with AS developed an aortic gradient of 90 mm Hg during the first trimester?

“It depends on whether she was asymptomatic prior to pregnancy. If so, I think it’s a low-risk situation, and you can carry on with the pregnancy,” he replied. Remember, he added, it’s the baseline gradient that’s important. Cardiac output goes up during the first trimester as a matter of course, and so will the gradient.

Dr. Orwat emphasized that symptomatic severe AS is an indication for aortic valve replacement, and he would advise an affected patient to undergo the surgery prior to pregnancy.

Audience member Dr. Fiona Walker rose to advocate ordering a prepregnancy treadmill exercise test in all patients with asymptomatic severe AS in order to learn whether they are likely to remain asymptomatic during the stresses of pregnancy. In a patient with severe AS who remains asymptomatic with exercise, it’s probably safer to go through pregnancy without prior valve replacement than to put in a mechanical valve.

“Patients with mechanical valves in pregnancy are one of the highest-risk groups we look after,” commented Dr. Walker, head of the maternal cardiology program at University College London Hospitals.

But another audience member advocated aortic valve replacement prior to pregnancy in all women with severe AS, asymptomatic or not.

“Nowadays, if you are afraid of a mechanical valve, you can put in a bioprosthetic one, although I know that’s considered controversial. I see that asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis seems quite safe in ROPAC, but I still consider severe aortic stenosis one of the truly dangerous problems in pregnancy. Maybe I’ll change my mind after ROPAC is published, but right now I don’t think we’re going to leave a severe aortic stenosis prior to pregnancy without intervention,” declared Dr. Avraham Shotan, head of the Heart Institute at Hillel Yaffe Medical Center in Hadera, Israel.

Session cochair Dr. Christa Gohlke-Baerwolf of Bad Krozingen (Germany) Hospital mediated the dispute and closed discussion by observing, “Severe aortic stenosis is not just one thing, it’s a continuum, and such patients should be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team very carefully before starting pregnancy.“

ROPAC is sponsored by the ESC. Dr. Orwat reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

LONDON – The mortality risk for pregnant women with moderate or severe aortic stenosis is close to zero in contemporary practice, according to data from the large, international ROPAC registry.

That being said, more than one-third of women with severe aortic stenosis will require hospitalization for cardiac reasons during their pregnancy, with heart failure the number-one cause for admission, Dr. Stefan Orwat reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Severe fetal complications are rare. However, preterm birth, small for gestational age, and neonatal Apgar scores below 7 are quite common in pregnancies involving severe aortic stenosis, as defined by a prepregnancy transaortic peak gradient of 64 mm Hg or more, according to Dr. Orwat of University Hospital in Muenster, Germany.

ROPAC (the Registry on Pregnancy and Cardiac disease) is a unique ongoing, global, prospective, observational registry created in order to advance understanding of the risks of pregnancy in the setting of structural heart disease. Prior reports from other sources have often provided conflicting guidance because of relatively small patient sample sizes. That’s been especially true with regard to aortic stenosis (AS), the cardiologist said.

Out of 2,966 pregnancies in women with various forms of structural heart disease in ROPAC, Dr. Orwat focused on the 99 pregnancies in 96 women with moderate or severe AS, 21 of whom had a prosthetic heart valve in place prior to pregnancy; 65 of the women had moderate AS as evidenced by an echocardiographic prepregnancy peak gradient of 36-63 mm Hg.

No maternal deaths occurred during pregnancy or within 1 week afterward. However, 13% of women with moderate AS and 35% with severe AS were hospitalized for cardiac reasons during their pregnancy. Most of the admissions were for new or worsening heart failure, which occurred at a median of 28 weeks’ gestation.

The risk of heart failure hospitalization during pregnancy was quite low – in the 6%-8% range – among women with baseline prepregnancy asymptomatic or symptomatic moderate AS or asymptomatic severe AS. In contrast, the rate shot up to 26% in women with symptomatic and severe AS prior to pregnancy.

There were a couple of hospitalizations for arrhythmias and one for endocarditis. Unlike in some prior reports by other research groups, there were no cases of pulmonary embolism, valve thrombosis, cerebrovascular events, or deep vein thrombosis. The presence of a mechanical valve with its required rigorous anticoagulation wasn’t related to worse outcomes in this series, unlike in some others.

The heart failure was generally manageable medically. Only two patients required intervention. One developed endocarditis, then underwent balloon aortic valvuloplasty and aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve 4 months into pregnancy, with subsequent vaginal delivery at 38 weeks. The other patient, who was unaware she had AS prior to pregnancy, presented with severe AS and a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction at 20 weeks’ gestation. She responded well to valvuloplasty, had an uneventful vaginal delivery at 38 weeks, then underwent aortic valve replacement.

In a multivariate analysis, only two independent predictors of maternal hospitalization during pregnancy were identified: the presence of symptoms prior to pregnancy, and the prepregnancy hemodynamic severity of AS.

Preterm birth prior to 37 weeks occurred in 16% of pregnancies involving moderate and 36% of those featuring severe AS. An Apgar score below 7 occurred in 5% of cases of moderate and 16% of severe AS. The small for gestational age rate was 3% with moderate AS and ballooned to 21% with severe AS. The only independent predictor of fetal complications was the degree of elevation in peak aortic gradient prior to pregnancy.

Audience questions focused on challenging scenarios. Would you allow a pregnancy to continue, Dr. Orwat was asked, if a woman with AS developed an aortic gradient of 90 mm Hg during the first trimester?

“It depends on whether she was asymptomatic prior to pregnancy. If so, I think it’s a low-risk situation, and you can carry on with the pregnancy,” he replied. Remember, he added, it’s the baseline gradient that’s important. Cardiac output goes up during the first trimester as a matter of course, and so will the gradient.

Dr. Orwat emphasized that symptomatic severe AS is an indication for aortic valve replacement, and he would advise an affected patient to undergo the surgery prior to pregnancy.

Audience member Dr. Fiona Walker rose to advocate ordering a prepregnancy treadmill exercise test in all patients with asymptomatic severe AS in order to learn whether they are likely to remain asymptomatic during the stresses of pregnancy. In a patient with severe AS who remains asymptomatic with exercise, it’s probably safer to go through pregnancy without prior valve replacement than to put in a mechanical valve.

“Patients with mechanical valves in pregnancy are one of the highest-risk groups we look after,” commented Dr. Walker, head of the maternal cardiology program at University College London Hospitals.

But another audience member advocated aortic valve replacement prior to pregnancy in all women with severe AS, asymptomatic or not.

“Nowadays, if you are afraid of a mechanical valve, you can put in a bioprosthetic one, although I know that’s considered controversial. I see that asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis seems quite safe in ROPAC, but I still consider severe aortic stenosis one of the truly dangerous problems in pregnancy. Maybe I’ll change my mind after ROPAC is published, but right now I don’t think we’re going to leave a severe aortic stenosis prior to pregnancy without intervention,” declared Dr. Avraham Shotan, head of the Heart Institute at Hillel Yaffe Medical Center in Hadera, Israel.

Session cochair Dr. Christa Gohlke-Baerwolf of Bad Krozingen (Germany) Hospital mediated the dispute and closed discussion by observing, “Severe aortic stenosis is not just one thing, it’s a continuum, and such patients should be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team very carefully before starting pregnancy.“

ROPAC is sponsored by the ESC. Dr. Orwat reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 20015

Key clinical point: Pregnancy in women with aortic stenosis now carries a near-zero risk of maternal mortality.

Major finding: Maternal mortality was zero in 99 pregnancies in 96 women with moderate or severe aortic stenosis.

Data source: The ROPAC registry is an ongoing, prospective, global, observational registry devoted to women with structural heart disease.

Disclosures: The registry is sponsored by the European Society of Cardiology. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ESC: Too much TV boosts PE risk

LONDON – Middle-aged adults who watch TV for an average of 5 or more hours per night face an adjusted 6.5-fold increased risk of fatal pulmonary embolism, compared with those who watch less than 2.5 hours per night, Toru Shirakawa reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This was the key lesson gleaned from an analysis from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study, the first large-scale prospective investigation of the relationship between prolonged television watching and pulmonary embolism (PE). The study included 86,024 Japanese participants aged 40-79 years prospectively followed for a median of 18.4 years, explained Mr. Shirakawa, a medical student at Osaka (Japan) University.

And while many busy medical professionals might presume 5 hours–plus of TV watching per night constitutes extreme behavior, that’s hardly the case. Indeed, according to the Nielsen survey, American adults watch an average of 4.85 hours of TV nightly.

During the study period there were 59 confirmed deaths from PE. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex and baseline age, cardiovascular risk factors, and physical activity level, a strong dose-response relationship was evident between hours of TV viewing and fatal PE.