User login

Lichenoid Drug Eruption Secondary to Apalutamide Treatment

To the Editor:

Lichenoid drug eruptions are lichen planus–like hypersensitivity reactions induced by medications. These reactions are rare but cause irritation to the skin, as extreme pruritus is common. One review of 300 consecutive cases of drug eruptions submitted to dermatopathology revealed that 12% of cases were classified as lichenoid drug reactions.1 Lichenoid dermatitis is characterized by extremely pruritic, scaly, eczematous or psoriasiform papules, often along the extensor surfaces and trunk.2 The pruritic nature of the rash can negatively impact quality of life. Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the offending medication, although complete resolution can take months, even after the drug is stopped. Although there have been some data suggesting that topical and/or oral corticosteroids can help with resolution, the rash can persist even with steroid treatment.2

The histopathologic findings of lichenoid drug eruptions show lichen planus–like changes such as hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and lichenoid interface dermatitis. Accordingly, idiopathic lichen planus is an important differential diagnosis for lichenoid drug eruptions; however, compared to idiopathic lichen planus, lichenoid drug eruptions are more likely to be associated with eosinophils and parakeratosis.1,3 In some cases, the histopathologic distinction between the 2 conditions is impossible, and clinical history needs to be considered to make a diagnosis.1 Drugs known to cause lichenoid drug reactions more commonly include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, thiazides, gold, penicillamine, and antimalarials.2 Lichenoid drug eruptions also have been documented in patients taking the second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist enzalutamide, which is used for the treatment of prostate cancer.4 More recently, the newer second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist apalutamide has been implicated in several cases of lichenoid drug eruptions.5,6

We present a case of an apalutamide-induced lichenoid drug eruption that was resistant to dose reduction and required discontinuation of treatment due to the negative impact on the patient’s quality of life. Once the rash resolved, the patient transitioned to enzalutamide without any adverse events (AEs).

A 72-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostate cancer (stage IVB) presented to the dermatology clinic with a 4-month history of a dry itchy rash on the face, chest, back, and legs that had developed 2 to 3 months after oncology started him on apalutamide. The patient initially received apalutamide 240 mg/d, which was reduced by his oncologist 3 months later to 180 mg/d following the appearance of the rash. Then apalutamide was held as he awaited improvement of the rash.

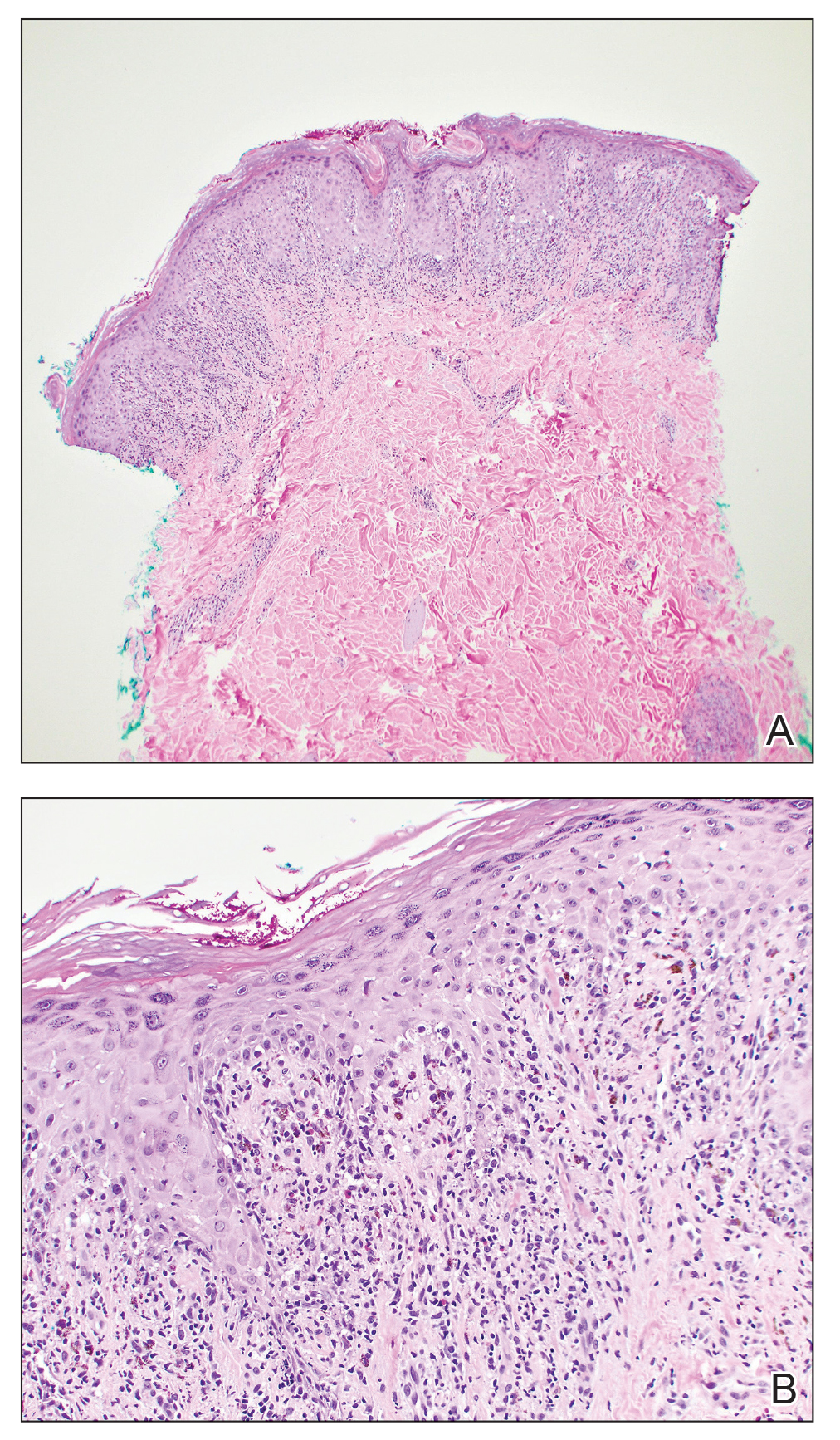

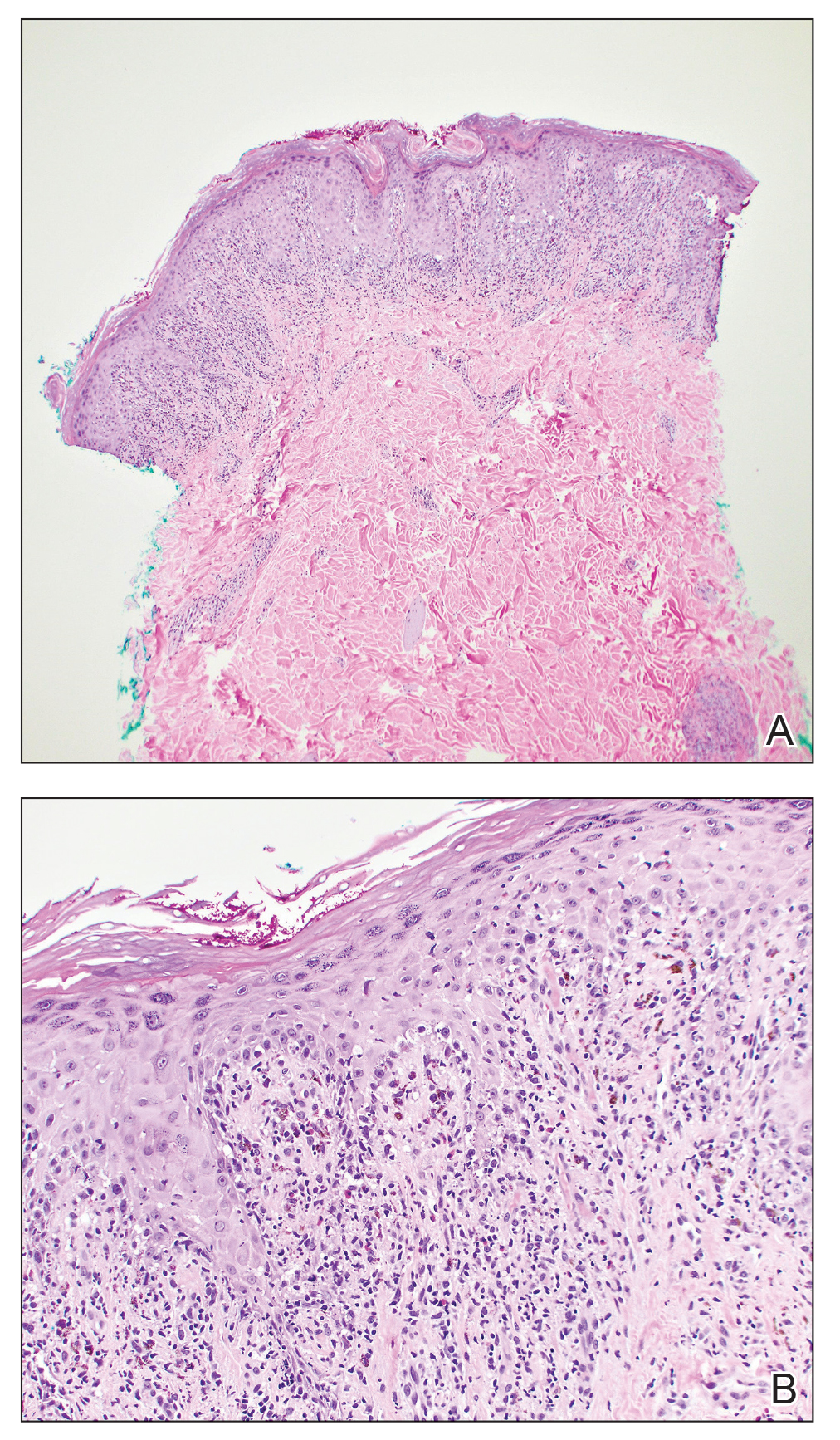

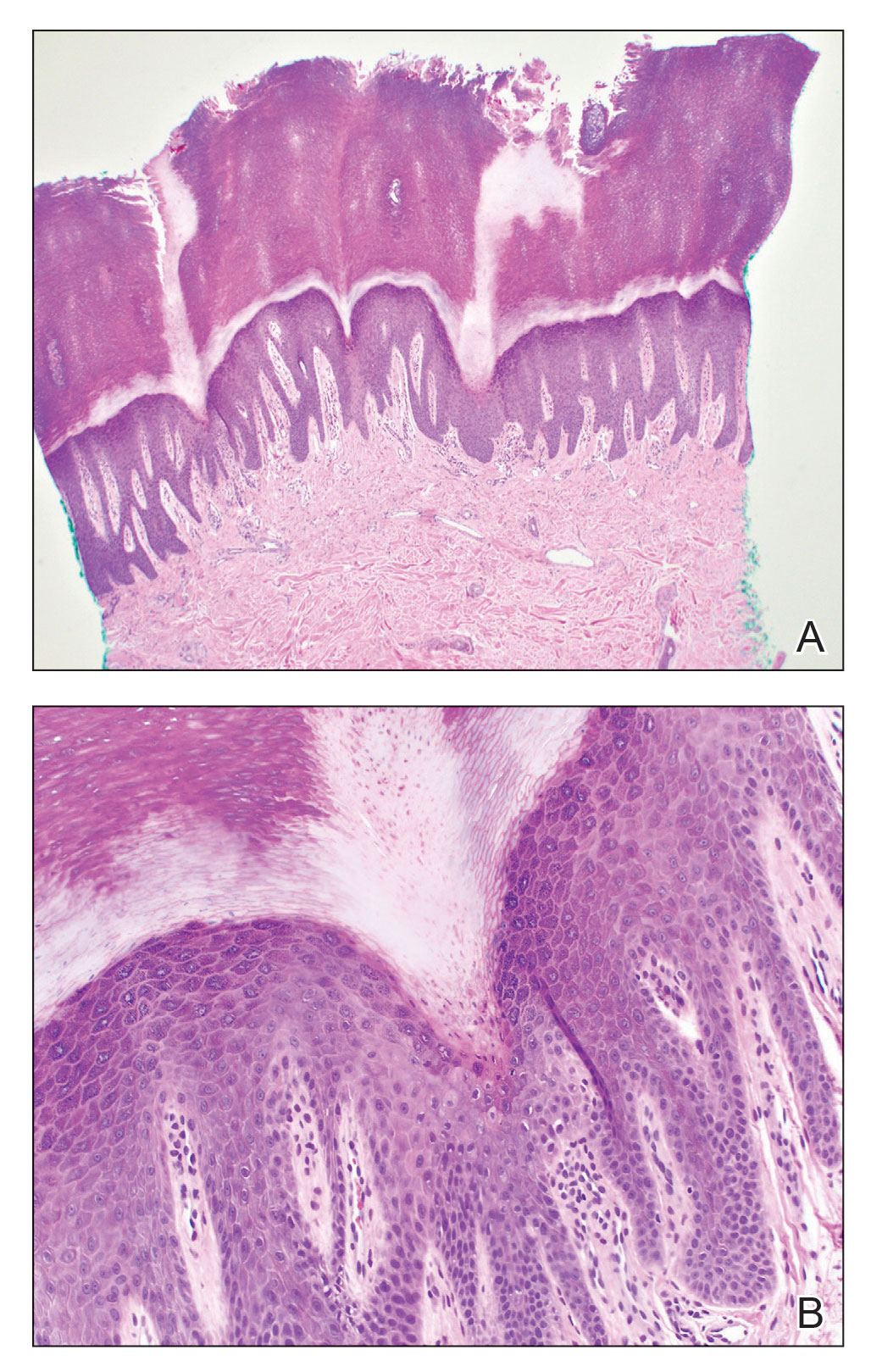

One week after the apalutamide was held, the patient presented to dermatology. He reported that he had tried over-the-counter ammonium lactate 12% lotion twice daily when the rash first developed without improvement. When the apalutamide was held, oncology prescribed mupirocin ointment 2% 3 times daily which yielded minimal relief. On physical examination, widespread lichenified papules and plaques were noted on the face, chest, back, and legs (Figure 1). Dermatology initially prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of the upper back revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with numerous eosinophils compatible with a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 2). Considering the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of lichenoid drug eruption secondary to apalutamide treatment was made.

Two weeks after discontinuation of the medication, the rash improved, and the patient restarted apalutamide at a dosage of 120 mg/d; however, the rash re-emerged within 1 month and was resistant to the triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. Apalutamide was again discontinued, and oncology switched the patient to enzalutamide 160 mg/d in an effort to find a medication the patient could better tolerate. Two months after starting enzalutamide, the patient had resolution of the rash and no further dermatologic complications.

Apalutamide is a second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist used in the treatment of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (CSPC).7 It stops the spread and growth of prostate cancer cells by several different mechanisms, including competitively binding androgen receptors, preventing 5α-dihydrotestosterone from binding to androgen receptors, blocking androgen receptor nuclear translocation, impairing co-activator recruitment, and restraining androgen receptor DNA binding.7 The SPARTAN and TITAN phase 3 clinical trials demonstrated increased overall survival and time to progression with apalutamide in both nonmetastatic CRPC and metastatic CSPC. In both trials, the rash was shown to be an AE more commonly associated with apalutamide than placebo.8,9

Until recently, the characteristics of apalutamide-induced drug rashes have not been well described. One literature review reported 6 cases of cutaneous apalutamide-induced drug eruptions.5 Four (66.7%) of these eruptions were maculopapular rashes, only 2 of which were histologically classified as lichenoid in nature. The other 2 eruptions were classified as toxic epidermal necrosis.5 Another study of 303 patients with prostate cancer who were treated with apalutamide recorded the frequency and time to onset of dermatologic AEs.6 Seventy-one (23.4%) of the patients had dermatologic AEs, and of those, only 20 (28.2%) had AEs that resulted in interruptions in apalutamide therapy (with only 5 [25.0%] requiring medication discontinuation). Thirty-two (45.1%) patients were managed with topical or oral corticosteroids or dose modification. In this study, histopathology was examined in 8 cases (one of which had 2 biopsies for a total of 9 biopsies), 7 of which were consistent with lichenoid interface dermatitis.6

Lichenoid interface dermatitis is a rare manifestation of an apalutamide-induced drug eruption and also has been reported secondary to treatment with enzalutamide, another second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist.4 Enzalutamide was the first second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist approved for the treatment of prostate cancer. It originally was approved only for metastatic CRPC after docetaxel therapy in 2012, then later was expanded to metastatic and nonmetastatic CRPC in 2012 and 2018, respectively, as well as metastatic CSPC in 2019.7 Because enzalutamide is from the same medication class as apalutamide and has been on the market longer for the treatment of nonmetastatic CRPC and metastatic CSPC, it is not surprising that similar drug eruptions now are being reported secondary to apalutamide use as well.

It is important for providers to consider lichenoid drug eruptions in the differential diagnosis of pruritic rashes in patients taking second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonists such as apalutamide or enzalutamide. Although dose reduction or treatment discontinuation have been the standard of care for patients with extremely pruritic lichenoid drug eruptions secondary to these medications, these are not ideal because they are important for cancer treatment. Interestingly, after our patient’s apalutamide-induced rash resolved and he was switched to enzalutamide, he did not develop any AEs. Based on our patient’s experience, physicians could consider switching their patients to another drug of the same class, as they may be able tolerate that medication. More research is needed to determine how commonly patients tolerate a different second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist after not tolerating another medication from the same class.

- Weyers W, Metze D. Histopathology of drug eruptions—general criteria, common patterns, and differential diagnosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2011;1:33-47. doi:10.5826/dpc.0101a09

- Cheraghlou S, Levy LL. Fixed drug eruption, bullous drug eruptions, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:679-692. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.06.010

- Thompson DF, Skaehill PA. Drug-induced lichen planus. Pharmacotherapy. 1994;14:561-571.

- Khan S, Saizan AL, O’Brien K, et al. Diffuse hyperpigmented lichenoid drug eruption secondary to enzalutamide. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;5:100135. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2021.100135

- Katayama H, Saeki H, Osada S-I. Maculopapular drug eruption caused by apalutamide: case report and review of the literature. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89:550-554. doi:10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-503

- Pan A, Reingold RE, Zhao JL, et al. Dermatologic adverse events in prostate cancer patients treated with the androgen receptor inhibitor apalutamide. J Urol. 2022;207:1010-1019. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002425

- Rajaram P, Rivera A, Muthima K, et al. Second-generation androgen receptor antagonists as hormonal therapeutics for three forms of prostate cancer. Molecules. 2020;25:2448. doi:10.3390/molecules25102448

- Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1408-1418. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1715546

- Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensative prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903307

To the Editor:

Lichenoid drug eruptions are lichen planus–like hypersensitivity reactions induced by medications. These reactions are rare but cause irritation to the skin, as extreme pruritus is common. One review of 300 consecutive cases of drug eruptions submitted to dermatopathology revealed that 12% of cases were classified as lichenoid drug reactions.1 Lichenoid dermatitis is characterized by extremely pruritic, scaly, eczematous or psoriasiform papules, often along the extensor surfaces and trunk.2 The pruritic nature of the rash can negatively impact quality of life. Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the offending medication, although complete resolution can take months, even after the drug is stopped. Although there have been some data suggesting that topical and/or oral corticosteroids can help with resolution, the rash can persist even with steroid treatment.2

The histopathologic findings of lichenoid drug eruptions show lichen planus–like changes such as hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and lichenoid interface dermatitis. Accordingly, idiopathic lichen planus is an important differential diagnosis for lichenoid drug eruptions; however, compared to idiopathic lichen planus, lichenoid drug eruptions are more likely to be associated with eosinophils and parakeratosis.1,3 In some cases, the histopathologic distinction between the 2 conditions is impossible, and clinical history needs to be considered to make a diagnosis.1 Drugs known to cause lichenoid drug reactions more commonly include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, thiazides, gold, penicillamine, and antimalarials.2 Lichenoid drug eruptions also have been documented in patients taking the second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist enzalutamide, which is used for the treatment of prostate cancer.4 More recently, the newer second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist apalutamide has been implicated in several cases of lichenoid drug eruptions.5,6

We present a case of an apalutamide-induced lichenoid drug eruption that was resistant to dose reduction and required discontinuation of treatment due to the negative impact on the patient’s quality of life. Once the rash resolved, the patient transitioned to enzalutamide without any adverse events (AEs).

A 72-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostate cancer (stage IVB) presented to the dermatology clinic with a 4-month history of a dry itchy rash on the face, chest, back, and legs that had developed 2 to 3 months after oncology started him on apalutamide. The patient initially received apalutamide 240 mg/d, which was reduced by his oncologist 3 months later to 180 mg/d following the appearance of the rash. Then apalutamide was held as he awaited improvement of the rash.

One week after the apalutamide was held, the patient presented to dermatology. He reported that he had tried over-the-counter ammonium lactate 12% lotion twice daily when the rash first developed without improvement. When the apalutamide was held, oncology prescribed mupirocin ointment 2% 3 times daily which yielded minimal relief. On physical examination, widespread lichenified papules and plaques were noted on the face, chest, back, and legs (Figure 1). Dermatology initially prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of the upper back revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with numerous eosinophils compatible with a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 2). Considering the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of lichenoid drug eruption secondary to apalutamide treatment was made.

Two weeks after discontinuation of the medication, the rash improved, and the patient restarted apalutamide at a dosage of 120 mg/d; however, the rash re-emerged within 1 month and was resistant to the triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. Apalutamide was again discontinued, and oncology switched the patient to enzalutamide 160 mg/d in an effort to find a medication the patient could better tolerate. Two months after starting enzalutamide, the patient had resolution of the rash and no further dermatologic complications.

Apalutamide is a second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist used in the treatment of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (CSPC).7 It stops the spread and growth of prostate cancer cells by several different mechanisms, including competitively binding androgen receptors, preventing 5α-dihydrotestosterone from binding to androgen receptors, blocking androgen receptor nuclear translocation, impairing co-activator recruitment, and restraining androgen receptor DNA binding.7 The SPARTAN and TITAN phase 3 clinical trials demonstrated increased overall survival and time to progression with apalutamide in both nonmetastatic CRPC and metastatic CSPC. In both trials, the rash was shown to be an AE more commonly associated with apalutamide than placebo.8,9

Until recently, the characteristics of apalutamide-induced drug rashes have not been well described. One literature review reported 6 cases of cutaneous apalutamide-induced drug eruptions.5 Four (66.7%) of these eruptions were maculopapular rashes, only 2 of which were histologically classified as lichenoid in nature. The other 2 eruptions were classified as toxic epidermal necrosis.5 Another study of 303 patients with prostate cancer who were treated with apalutamide recorded the frequency and time to onset of dermatologic AEs.6 Seventy-one (23.4%) of the patients had dermatologic AEs, and of those, only 20 (28.2%) had AEs that resulted in interruptions in apalutamide therapy (with only 5 [25.0%] requiring medication discontinuation). Thirty-two (45.1%) patients were managed with topical or oral corticosteroids or dose modification. In this study, histopathology was examined in 8 cases (one of which had 2 biopsies for a total of 9 biopsies), 7 of which were consistent with lichenoid interface dermatitis.6

Lichenoid interface dermatitis is a rare manifestation of an apalutamide-induced drug eruption and also has been reported secondary to treatment with enzalutamide, another second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist.4 Enzalutamide was the first second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist approved for the treatment of prostate cancer. It originally was approved only for metastatic CRPC after docetaxel therapy in 2012, then later was expanded to metastatic and nonmetastatic CRPC in 2012 and 2018, respectively, as well as metastatic CSPC in 2019.7 Because enzalutamide is from the same medication class as apalutamide and has been on the market longer for the treatment of nonmetastatic CRPC and metastatic CSPC, it is not surprising that similar drug eruptions now are being reported secondary to apalutamide use as well.

It is important for providers to consider lichenoid drug eruptions in the differential diagnosis of pruritic rashes in patients taking second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonists such as apalutamide or enzalutamide. Although dose reduction or treatment discontinuation have been the standard of care for patients with extremely pruritic lichenoid drug eruptions secondary to these medications, these are not ideal because they are important for cancer treatment. Interestingly, after our patient’s apalutamide-induced rash resolved and he was switched to enzalutamide, he did not develop any AEs. Based on our patient’s experience, physicians could consider switching their patients to another drug of the same class, as they may be able tolerate that medication. More research is needed to determine how commonly patients tolerate a different second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist after not tolerating another medication from the same class.

To the Editor:

Lichenoid drug eruptions are lichen planus–like hypersensitivity reactions induced by medications. These reactions are rare but cause irritation to the skin, as extreme pruritus is common. One review of 300 consecutive cases of drug eruptions submitted to dermatopathology revealed that 12% of cases were classified as lichenoid drug reactions.1 Lichenoid dermatitis is characterized by extremely pruritic, scaly, eczematous or psoriasiform papules, often along the extensor surfaces and trunk.2 The pruritic nature of the rash can negatively impact quality of life. Treatment typically involves discontinuation of the offending medication, although complete resolution can take months, even after the drug is stopped. Although there have been some data suggesting that topical and/or oral corticosteroids can help with resolution, the rash can persist even with steroid treatment.2

The histopathologic findings of lichenoid drug eruptions show lichen planus–like changes such as hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and lichenoid interface dermatitis. Accordingly, idiopathic lichen planus is an important differential diagnosis for lichenoid drug eruptions; however, compared to idiopathic lichen planus, lichenoid drug eruptions are more likely to be associated with eosinophils and parakeratosis.1,3 In some cases, the histopathologic distinction between the 2 conditions is impossible, and clinical history needs to be considered to make a diagnosis.1 Drugs known to cause lichenoid drug reactions more commonly include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, thiazides, gold, penicillamine, and antimalarials.2 Lichenoid drug eruptions also have been documented in patients taking the second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist enzalutamide, which is used for the treatment of prostate cancer.4 More recently, the newer second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist apalutamide has been implicated in several cases of lichenoid drug eruptions.5,6

We present a case of an apalutamide-induced lichenoid drug eruption that was resistant to dose reduction and required discontinuation of treatment due to the negative impact on the patient’s quality of life. Once the rash resolved, the patient transitioned to enzalutamide without any adverse events (AEs).

A 72-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostate cancer (stage IVB) presented to the dermatology clinic with a 4-month history of a dry itchy rash on the face, chest, back, and legs that had developed 2 to 3 months after oncology started him on apalutamide. The patient initially received apalutamide 240 mg/d, which was reduced by his oncologist 3 months later to 180 mg/d following the appearance of the rash. Then apalutamide was held as he awaited improvement of the rash.

One week after the apalutamide was held, the patient presented to dermatology. He reported that he had tried over-the-counter ammonium lactate 12% lotion twice daily when the rash first developed without improvement. When the apalutamide was held, oncology prescribed mupirocin ointment 2% 3 times daily which yielded minimal relief. On physical examination, widespread lichenified papules and plaques were noted on the face, chest, back, and legs (Figure 1). Dermatology initially prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily. A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of the upper back revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with numerous eosinophils compatible with a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 2). Considering the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of lichenoid drug eruption secondary to apalutamide treatment was made.

Two weeks after discontinuation of the medication, the rash improved, and the patient restarted apalutamide at a dosage of 120 mg/d; however, the rash re-emerged within 1 month and was resistant to the triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. Apalutamide was again discontinued, and oncology switched the patient to enzalutamide 160 mg/d in an effort to find a medication the patient could better tolerate. Two months after starting enzalutamide, the patient had resolution of the rash and no further dermatologic complications.

Apalutamide is a second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist used in the treatment of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (CSPC).7 It stops the spread and growth of prostate cancer cells by several different mechanisms, including competitively binding androgen receptors, preventing 5α-dihydrotestosterone from binding to androgen receptors, blocking androgen receptor nuclear translocation, impairing co-activator recruitment, and restraining androgen receptor DNA binding.7 The SPARTAN and TITAN phase 3 clinical trials demonstrated increased overall survival and time to progression with apalutamide in both nonmetastatic CRPC and metastatic CSPC. In both trials, the rash was shown to be an AE more commonly associated with apalutamide than placebo.8,9

Until recently, the characteristics of apalutamide-induced drug rashes have not been well described. One literature review reported 6 cases of cutaneous apalutamide-induced drug eruptions.5 Four (66.7%) of these eruptions were maculopapular rashes, only 2 of which were histologically classified as lichenoid in nature. The other 2 eruptions were classified as toxic epidermal necrosis.5 Another study of 303 patients with prostate cancer who were treated with apalutamide recorded the frequency and time to onset of dermatologic AEs.6 Seventy-one (23.4%) of the patients had dermatologic AEs, and of those, only 20 (28.2%) had AEs that resulted in interruptions in apalutamide therapy (with only 5 [25.0%] requiring medication discontinuation). Thirty-two (45.1%) patients were managed with topical or oral corticosteroids or dose modification. In this study, histopathology was examined in 8 cases (one of which had 2 biopsies for a total of 9 biopsies), 7 of which were consistent with lichenoid interface dermatitis.6

Lichenoid interface dermatitis is a rare manifestation of an apalutamide-induced drug eruption and also has been reported secondary to treatment with enzalutamide, another second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist.4 Enzalutamide was the first second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist approved for the treatment of prostate cancer. It originally was approved only for metastatic CRPC after docetaxel therapy in 2012, then later was expanded to metastatic and nonmetastatic CRPC in 2012 and 2018, respectively, as well as metastatic CSPC in 2019.7 Because enzalutamide is from the same medication class as apalutamide and has been on the market longer for the treatment of nonmetastatic CRPC and metastatic CSPC, it is not surprising that similar drug eruptions now are being reported secondary to apalutamide use as well.

It is important for providers to consider lichenoid drug eruptions in the differential diagnosis of pruritic rashes in patients taking second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonists such as apalutamide or enzalutamide. Although dose reduction or treatment discontinuation have been the standard of care for patients with extremely pruritic lichenoid drug eruptions secondary to these medications, these are not ideal because they are important for cancer treatment. Interestingly, after our patient’s apalutamide-induced rash resolved and he was switched to enzalutamide, he did not develop any AEs. Based on our patient’s experience, physicians could consider switching their patients to another drug of the same class, as they may be able tolerate that medication. More research is needed to determine how commonly patients tolerate a different second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist after not tolerating another medication from the same class.

- Weyers W, Metze D. Histopathology of drug eruptions—general criteria, common patterns, and differential diagnosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2011;1:33-47. doi:10.5826/dpc.0101a09

- Cheraghlou S, Levy LL. Fixed drug eruption, bullous drug eruptions, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:679-692. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.06.010

- Thompson DF, Skaehill PA. Drug-induced lichen planus. Pharmacotherapy. 1994;14:561-571.

- Khan S, Saizan AL, O’Brien K, et al. Diffuse hyperpigmented lichenoid drug eruption secondary to enzalutamide. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;5:100135. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2021.100135

- Katayama H, Saeki H, Osada S-I. Maculopapular drug eruption caused by apalutamide: case report and review of the literature. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89:550-554. doi:10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-503

- Pan A, Reingold RE, Zhao JL, et al. Dermatologic adverse events in prostate cancer patients treated with the androgen receptor inhibitor apalutamide. J Urol. 2022;207:1010-1019. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002425

- Rajaram P, Rivera A, Muthima K, et al. Second-generation androgen receptor antagonists as hormonal therapeutics for three forms of prostate cancer. Molecules. 2020;25:2448. doi:10.3390/molecules25102448

- Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1408-1418. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1715546

- Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensative prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903307

- Weyers W, Metze D. Histopathology of drug eruptions—general criteria, common patterns, and differential diagnosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2011;1:33-47. doi:10.5826/dpc.0101a09

- Cheraghlou S, Levy LL. Fixed drug eruption, bullous drug eruptions, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:679-692. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.06.010

- Thompson DF, Skaehill PA. Drug-induced lichen planus. Pharmacotherapy. 1994;14:561-571.

- Khan S, Saizan AL, O’Brien K, et al. Diffuse hyperpigmented lichenoid drug eruption secondary to enzalutamide. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 2022;5:100135. doi:10.1016/j.cpccr.2021.100135

- Katayama H, Saeki H, Osada S-I. Maculopapular drug eruption caused by apalutamide: case report and review of the literature. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89:550-554. doi:10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-503

- Pan A, Reingold RE, Zhao JL, et al. Dermatologic adverse events in prostate cancer patients treated with the androgen receptor inhibitor apalutamide. J Urol. 2022;207:1010-1019. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002425

- Rajaram P, Rivera A, Muthima K, et al. Second-generation androgen receptor antagonists as hormonal therapeutics for three forms of prostate cancer. Molecules. 2020;25:2448. doi:10.3390/molecules25102448

- Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1408-1418. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1715546

- Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensative prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903307

Practice Points

- Although it is rare, patients can develop lichenoid drug eruptions secondary to treatment with second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonists such as apalutamide.

- If a patient develops a lichenoid drug eruption while taking a specific second-generation nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist, the entire class of medications should not be ruled out, as some patients can tolerate other drugs from that class.

Symmetric Palmoplantar Papules With a Keratotic Border

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis Plantaris Palmaris et Disseminata

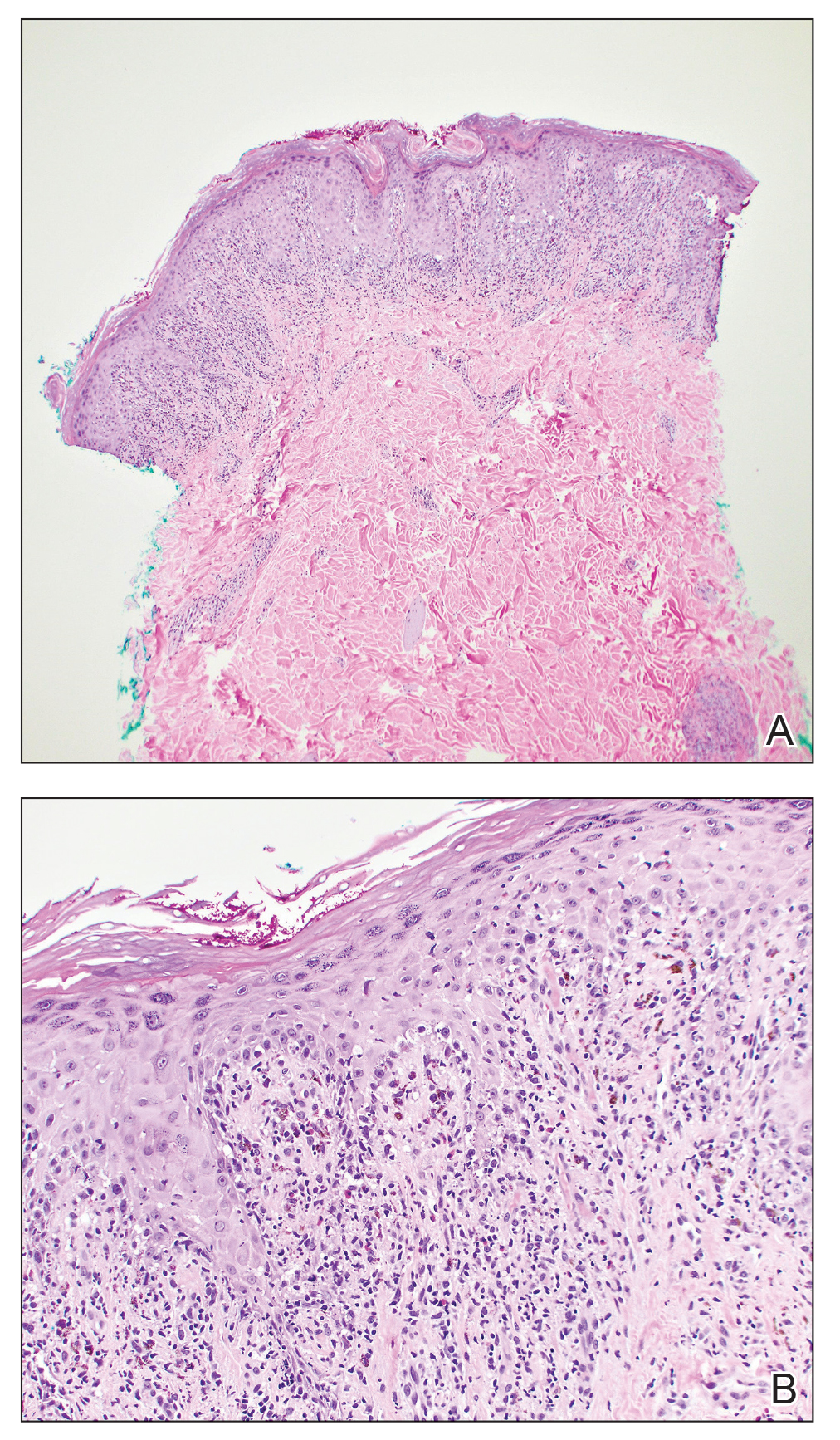

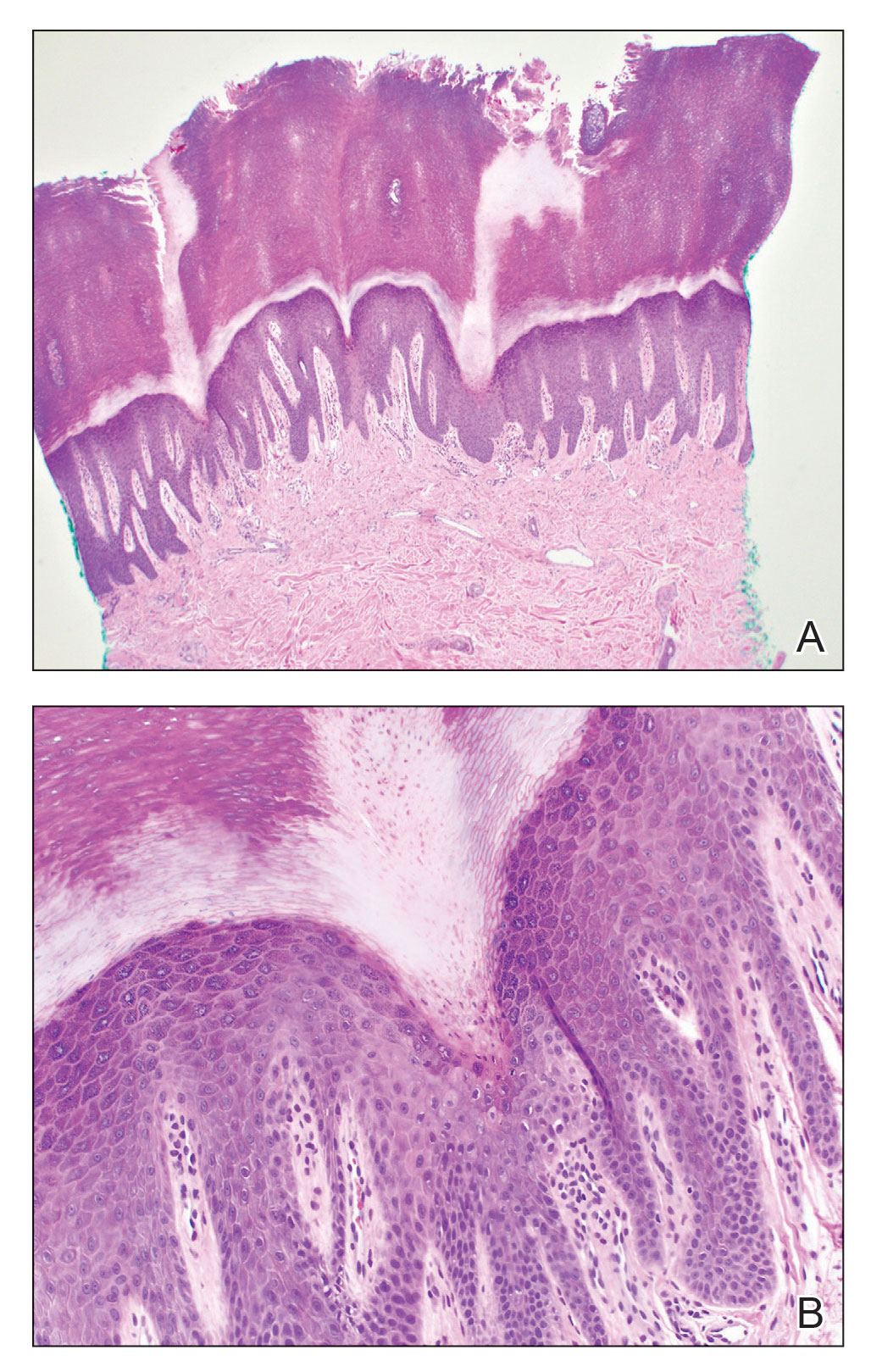

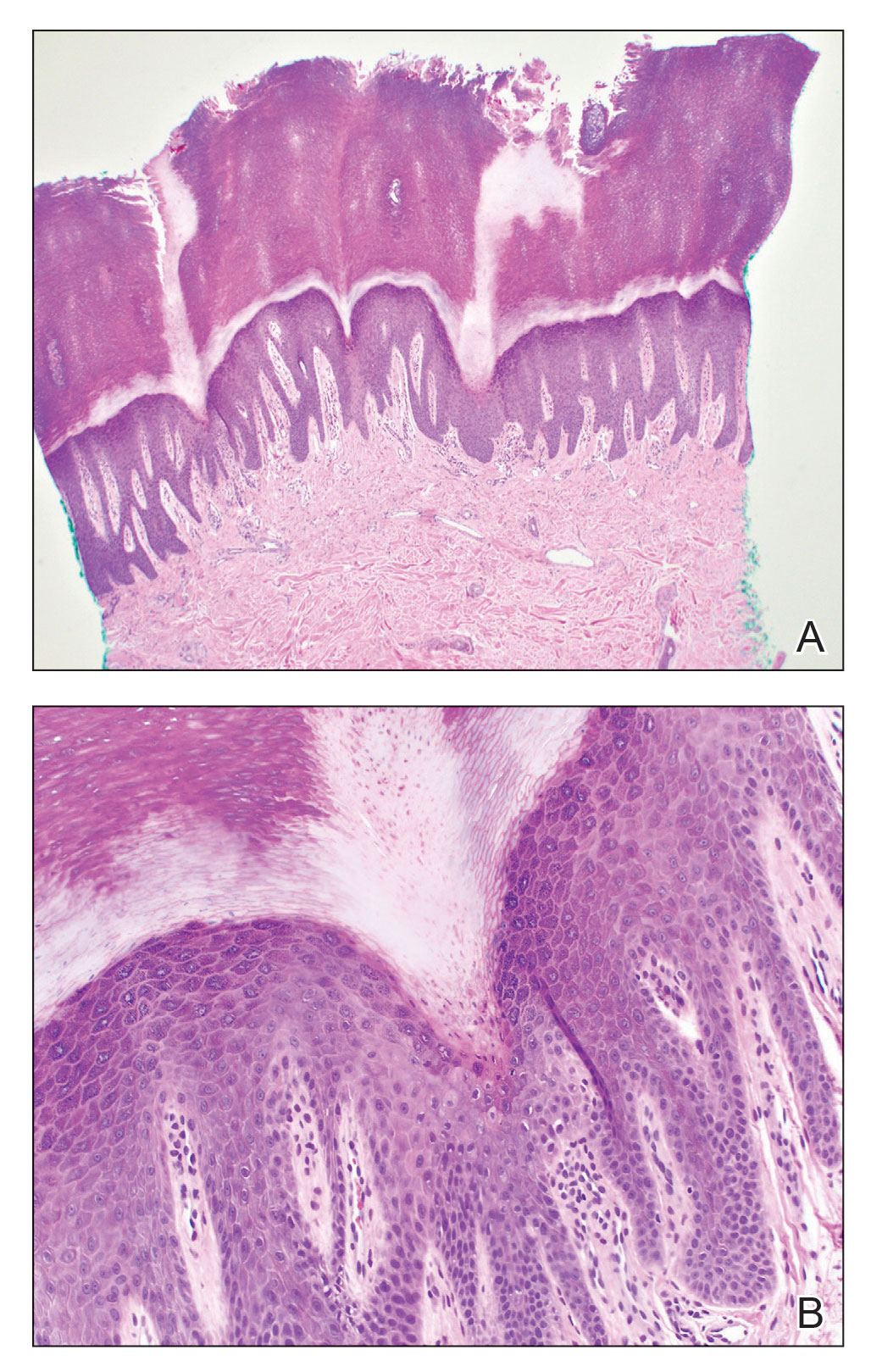

A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right upper arm showed incipient cornoid lamellae formation, pigment incontinence, and sparse dermal lymphocytic inflammation (Figure), suggestive of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (PPPD). The dermatopathologist recommended a second biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to confirm that the lesions on the palms and soles also were suggestive of porokeratosis. A second 4-mm punch biopsy of the left palm was consistent with PPPD.

The risks of PPPD as a precancerous entity along with the benefits and side effects of the various management options were discussed with our patient. We recommended that he start low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d) due to the large body surface area affected, making focal and field treatments likely insufficient. However, our patient opted not to treat and did not return for follow-up.

Subtypes of porokeratosis, including disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) and PPPD, are conditions that disrupt the normal maturation of keratin and present clinically with symmetric, crusted, annular papules.1 The signature but nonspecific histopathologic feature shared among the subtypes is the presence of a cornoid lamellae.2 Several triggers of porokeratosis have been proposed, including trauma and exposure to UV and ionizing radiation.2,3 The clinical variants of porokeratosis are important conditions to diagnose correctly because they portend a risk for Bowen disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma and may indicate the presence of an underlying hematologic and/or solid organ malignancy.4 Management of porokeratosis is difficult, as treatments have shown limited efficacy and variable recurrence rates. Treatment options include focal, field, and systemic options, such as 5-fluorouracil, topical compound of cholesterol and lovastatin, isotretinoin, and acitretin.1,2

Porokeratoses may arise from gene mutations in the mevalonate pathway,5 which is essential for the production of cholesterol.6 Topical cholesterol alone has not been shown to improve porokeratosis, but the combination topical therapy of cholesterol and lovastatin is promising. It is theorized to deliver benefit by both providing the essential end product of the pathway and simultaneously reducing the number of potentially toxic intermediates.6

Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (also known as porokeratosis plantaris) is unique among the subtypes of porokeratosis in that its annular, red-pink, papular rash with scaling and a keratotic border tends to start distally, involving the palms and soles, and progresses proximally to the trunk with smaller lesions.1,7 This centripetal progression can take years, as was seen in our patient.1 The disease is uncommon, with a dearth of published reports on PPPD.2 However, case reports have shown that PPPD is strongly linked to family history and may have an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Penetrance is greater in men than in women, as PPPD is twice as common in men.8 Most cases of PPPD have been diagnosed in patients in their 20s and 30s, but Hartman et al9 reported a case wherein a patient was diagnosed with PPPD after 65 years of age, similar to our patient.

Although the lesions in DSAP can appear similar to those in PPPD, DSAP is more common among the family of porokeratotic conditions, affecting women twice as often as men, with a sporadic pattern of inheritance.2 These same features are present in some other types of porokeratosis but not PPPD. Furthermore, DSAP progresses proximally to distally but often with truncal sparing.2

Akin to PPPD, pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) often presents with palmoplantar keratoderma.10 There are at least 6 types of PRP with varying degrees of similarity to PPPD. However, in many cases PRP is associated with a background of diffuse erythema on the body with islands of spared skin. In addition, cases of PRP have been linked to extracutaneous findings such as ectropion and joint pain.11

Darier disease, especially the acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf variant, is more common in men and involves younger populations, as in PPPD.11 However, the crusted lesions seen in Darier disease frequently involve the skin folds. These intertriginous lesions may coalesce, mimicking warts in appearance, and are at risk for secondary infection. Nail findings in Darier disease also are distinct and include longitudinal white or red stripes running along the nail bed, in addition to V-shaped nicks at the nail tips.

Psoriasis can occur anywhere on the body and is associated with silver scaling atop a salmon-colored dermatitis.12 It results from aberrant proliferation of keratinocytes. Some distinguishing features of psoriasis include a disease course that waxes and wanes as well as pitting of the nails.

Although PPPD typically affects young adults, we presented a case of PPPD in an older man. Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata in older adults may represent a delayed diagnosis, imply a broader range for the age of onset, or suggest its manifestation secondary to radiation treatment or another phenomenon. For example, our patient received 35 radiotherapy cycles for tongue cancer more than 5 years prior to the onset of PPPD.

- Irisawa R, Yamazaki M, Yamamoto T, et al. A case of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Vargas-Mora P, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fusta-Novell X. Porokeratosis: a review of its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:545-560.

- James AJ, Clarke LE, Elenitsas R, et al. Segmental porokeratosis after radiation therapy for follicular lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Schena D, Papagrigoraki A, Frigo A, et al. Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis associated with internal malignancies: a case report. Cutis. 2010;85:156-159.

- Zhang Z, Li C, Wu F, et al. Genomic variations of the mevalonate pathway in porokeratosis. Elife. 2015;4:E06322. doi:10.7554/eLife.06322

- Atzmony L, Lim YH, Hamilton C, et al. Topical cholesterol/lovastatin for the treatment of porokeratosis: a pathogenesis-directed therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:123-131. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.043

- Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

- Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:533-544.

- Hartman R, Mandal R, Sanchez M, et al. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:22.

- Suryawanshi H, Dhobley A, Sharma A, et al. Darier disease: a rare genodermatosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:321. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_170_16

- Eastham AB. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:404. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5030

- Nair PA, Badri T. Psoriasis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 6, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448194/

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis Plantaris Palmaris et Disseminata

A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right upper arm showed incipient cornoid lamellae formation, pigment incontinence, and sparse dermal lymphocytic inflammation (Figure), suggestive of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (PPPD). The dermatopathologist recommended a second biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to confirm that the lesions on the palms and soles also were suggestive of porokeratosis. A second 4-mm punch biopsy of the left palm was consistent with PPPD.

The risks of PPPD as a precancerous entity along with the benefits and side effects of the various management options were discussed with our patient. We recommended that he start low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d) due to the large body surface area affected, making focal and field treatments likely insufficient. However, our patient opted not to treat and did not return for follow-up.

Subtypes of porokeratosis, including disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) and PPPD, are conditions that disrupt the normal maturation of keratin and present clinically with symmetric, crusted, annular papules.1 The signature but nonspecific histopathologic feature shared among the subtypes is the presence of a cornoid lamellae.2 Several triggers of porokeratosis have been proposed, including trauma and exposure to UV and ionizing radiation.2,3 The clinical variants of porokeratosis are important conditions to diagnose correctly because they portend a risk for Bowen disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma and may indicate the presence of an underlying hematologic and/or solid organ malignancy.4 Management of porokeratosis is difficult, as treatments have shown limited efficacy and variable recurrence rates. Treatment options include focal, field, and systemic options, such as 5-fluorouracil, topical compound of cholesterol and lovastatin, isotretinoin, and acitretin.1,2

Porokeratoses may arise from gene mutations in the mevalonate pathway,5 which is essential for the production of cholesterol.6 Topical cholesterol alone has not been shown to improve porokeratosis, but the combination topical therapy of cholesterol and lovastatin is promising. It is theorized to deliver benefit by both providing the essential end product of the pathway and simultaneously reducing the number of potentially toxic intermediates.6

Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (also known as porokeratosis plantaris) is unique among the subtypes of porokeratosis in that its annular, red-pink, papular rash with scaling and a keratotic border tends to start distally, involving the palms and soles, and progresses proximally to the trunk with smaller lesions.1,7 This centripetal progression can take years, as was seen in our patient.1 The disease is uncommon, with a dearth of published reports on PPPD.2 However, case reports have shown that PPPD is strongly linked to family history and may have an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Penetrance is greater in men than in women, as PPPD is twice as common in men.8 Most cases of PPPD have been diagnosed in patients in their 20s and 30s, but Hartman et al9 reported a case wherein a patient was diagnosed with PPPD after 65 years of age, similar to our patient.

Although the lesions in DSAP can appear similar to those in PPPD, DSAP is more common among the family of porokeratotic conditions, affecting women twice as often as men, with a sporadic pattern of inheritance.2 These same features are present in some other types of porokeratosis but not PPPD. Furthermore, DSAP progresses proximally to distally but often with truncal sparing.2

Akin to PPPD, pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) often presents with palmoplantar keratoderma.10 There are at least 6 types of PRP with varying degrees of similarity to PPPD. However, in many cases PRP is associated with a background of diffuse erythema on the body with islands of spared skin. In addition, cases of PRP have been linked to extracutaneous findings such as ectropion and joint pain.11

Darier disease, especially the acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf variant, is more common in men and involves younger populations, as in PPPD.11 However, the crusted lesions seen in Darier disease frequently involve the skin folds. These intertriginous lesions may coalesce, mimicking warts in appearance, and are at risk for secondary infection. Nail findings in Darier disease also are distinct and include longitudinal white or red stripes running along the nail bed, in addition to V-shaped nicks at the nail tips.

Psoriasis can occur anywhere on the body and is associated with silver scaling atop a salmon-colored dermatitis.12 It results from aberrant proliferation of keratinocytes. Some distinguishing features of psoriasis include a disease course that waxes and wanes as well as pitting of the nails.

Although PPPD typically affects young adults, we presented a case of PPPD in an older man. Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata in older adults may represent a delayed diagnosis, imply a broader range for the age of onset, or suggest its manifestation secondary to radiation treatment or another phenomenon. For example, our patient received 35 radiotherapy cycles for tongue cancer more than 5 years prior to the onset of PPPD.

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis Plantaris Palmaris et Disseminata

A 3-mm punch biopsy of the right upper arm showed incipient cornoid lamellae formation, pigment incontinence, and sparse dermal lymphocytic inflammation (Figure), suggestive of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (PPPD). The dermatopathologist recommended a second biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to confirm that the lesions on the palms and soles also were suggestive of porokeratosis. A second 4-mm punch biopsy of the left palm was consistent with PPPD.

The risks of PPPD as a precancerous entity along with the benefits and side effects of the various management options were discussed with our patient. We recommended that he start low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg/d) due to the large body surface area affected, making focal and field treatments likely insufficient. However, our patient opted not to treat and did not return for follow-up.

Subtypes of porokeratosis, including disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) and PPPD, are conditions that disrupt the normal maturation of keratin and present clinically with symmetric, crusted, annular papules.1 The signature but nonspecific histopathologic feature shared among the subtypes is the presence of a cornoid lamellae.2 Several triggers of porokeratosis have been proposed, including trauma and exposure to UV and ionizing radiation.2,3 The clinical variants of porokeratosis are important conditions to diagnose correctly because they portend a risk for Bowen disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma and may indicate the presence of an underlying hematologic and/or solid organ malignancy.4 Management of porokeratosis is difficult, as treatments have shown limited efficacy and variable recurrence rates. Treatment options include focal, field, and systemic options, such as 5-fluorouracil, topical compound of cholesterol and lovastatin, isotretinoin, and acitretin.1,2

Porokeratoses may arise from gene mutations in the mevalonate pathway,5 which is essential for the production of cholesterol.6 Topical cholesterol alone has not been shown to improve porokeratosis, but the combination topical therapy of cholesterol and lovastatin is promising. It is theorized to deliver benefit by both providing the essential end product of the pathway and simultaneously reducing the number of potentially toxic intermediates.6

Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata (also known as porokeratosis plantaris) is unique among the subtypes of porokeratosis in that its annular, red-pink, papular rash with scaling and a keratotic border tends to start distally, involving the palms and soles, and progresses proximally to the trunk with smaller lesions.1,7 This centripetal progression can take years, as was seen in our patient.1 The disease is uncommon, with a dearth of published reports on PPPD.2 However, case reports have shown that PPPD is strongly linked to family history and may have an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern. Penetrance is greater in men than in women, as PPPD is twice as common in men.8 Most cases of PPPD have been diagnosed in patients in their 20s and 30s, but Hartman et al9 reported a case wherein a patient was diagnosed with PPPD after 65 years of age, similar to our patient.

Although the lesions in DSAP can appear similar to those in PPPD, DSAP is more common among the family of porokeratotic conditions, affecting women twice as often as men, with a sporadic pattern of inheritance.2 These same features are present in some other types of porokeratosis but not PPPD. Furthermore, DSAP progresses proximally to distally but often with truncal sparing.2

Akin to PPPD, pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) often presents with palmoplantar keratoderma.10 There are at least 6 types of PRP with varying degrees of similarity to PPPD. However, in many cases PRP is associated with a background of diffuse erythema on the body with islands of spared skin. In addition, cases of PRP have been linked to extracutaneous findings such as ectropion and joint pain.11

Darier disease, especially the acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf variant, is more common in men and involves younger populations, as in PPPD.11 However, the crusted lesions seen in Darier disease frequently involve the skin folds. These intertriginous lesions may coalesce, mimicking warts in appearance, and are at risk for secondary infection. Nail findings in Darier disease also are distinct and include longitudinal white or red stripes running along the nail bed, in addition to V-shaped nicks at the nail tips.

Psoriasis can occur anywhere on the body and is associated with silver scaling atop a salmon-colored dermatitis.12 It results from aberrant proliferation of keratinocytes. Some distinguishing features of psoriasis include a disease course that waxes and wanes as well as pitting of the nails.

Although PPPD typically affects young adults, we presented a case of PPPD in an older man. Porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata in older adults may represent a delayed diagnosis, imply a broader range for the age of onset, or suggest its manifestation secondary to radiation treatment or another phenomenon. For example, our patient received 35 radiotherapy cycles for tongue cancer more than 5 years prior to the onset of PPPD.

- Irisawa R, Yamazaki M, Yamamoto T, et al. A case of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Vargas-Mora P, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fusta-Novell X. Porokeratosis: a review of its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:545-560.

- James AJ, Clarke LE, Elenitsas R, et al. Segmental porokeratosis after radiation therapy for follicular lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Schena D, Papagrigoraki A, Frigo A, et al. Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis associated with internal malignancies: a case report. Cutis. 2010;85:156-159.

- Zhang Z, Li C, Wu F, et al. Genomic variations of the mevalonate pathway in porokeratosis. Elife. 2015;4:E06322. doi:10.7554/eLife.06322

- Atzmony L, Lim YH, Hamilton C, et al. Topical cholesterol/lovastatin for the treatment of porokeratosis: a pathogenesis-directed therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:123-131. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.043

- Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

- Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:533-544.

- Hartman R, Mandal R, Sanchez M, et al. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:22.

- Suryawanshi H, Dhobley A, Sharma A, et al. Darier disease: a rare genodermatosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:321. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_170_16

- Eastham AB. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:404. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5030

- Nair PA, Badri T. Psoriasis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 6, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448194/

- Irisawa R, Yamazaki M, Yamamoto T, et al. A case of porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Vargas-Mora P, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fusta-Novell X. Porokeratosis: a review of its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:545-560.

- James AJ, Clarke LE, Elenitsas R, et al. Segmental porokeratosis after radiation therapy for follicular lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Schena D, Papagrigoraki A, Frigo A, et al. Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis associated with internal malignancies: a case report. Cutis. 2010;85:156-159.

- Zhang Z, Li C, Wu F, et al. Genomic variations of the mevalonate pathway in porokeratosis. Elife. 2015;4:E06322. doi:10.7554/eLife.06322

- Atzmony L, Lim YH, Hamilton C, et al. Topical cholesterol/lovastatin for the treatment of porokeratosis: a pathogenesis-directed therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:123-131. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.043

- Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

- Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:533-544.

- Hartman R, Mandal R, Sanchez M, et al. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris, et disseminata. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:22.

- Suryawanshi H, Dhobley A, Sharma A, et al. Darier disease: a rare genodermatosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:321. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_170_16

- Eastham AB. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:404. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5030

- Nair PA, Badri T. Psoriasis. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated April 6, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448194/

A 67-year-old man presented to our office with a rash on the hands, feet, and periungual skin that began with wartlike growths many years prior and recently had started to involve the proximal arms and legs up to the thighs as well as the trunk. He had a medical history of essential hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He had an 18-year smoking history and had quit more than 25 years prior, with tongue cancer diagnosed more than 5 years prior that was treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. The lesions occasionally were itchy but not painful. He also reported that his nails frequently split down the middle. He denied any oral lesions and was not using any treatments for the rash. He had no history of skin cancer or other skin conditions. His family history was unclear. Physical examination revealed annular red-pink scaling with a keratotic border on the soles of the feet, palms, and periungual skin. There also were small hyperpigmented papules on the arms, legs, thighs, and trunk over a background of dry and discolored skin, as well as dystrophy of all nails.