User login

Questioning the Specificity and Sensitivity of ELISA for Bullous Pemphigoid Diagnosis

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease. The classic presentation of BP is a generalized, pruritic, bullous eruption in elderly patients, which is occasionally preceded by an urticarial prodrome. Immunopathologically, BP is characterized by IgG and sometimes IgE autoantibodies that target basement membrane zone proteins BP180 and BP230 of the epidermis.1

The diagnosis of BP should be suspected when an elderly patient presents with tense blisters and can be confirmed via diagnostic testing, including tissue histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as the gold standard, as well as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and most recently biochip technology as supportive tests.2 Since its advent, ELISA has gained popularity as a trustworthy diagnostic test for BP. The specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis is reported to be 98% to 100%, which leads clinicians to believe that a positive ELISA equals certain diagnosis of BP; however, misdiagnosis of BP based on a positive ELISA result can occur.3-13 The treatment of BP often involves lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. Complications of immunosuppressive therapy contribute to morbidity and mortality in these patients, thus an accurate diagnosis is paramount before introducing therapy.14

We present the case of a 74-year-old man with a history of a pruritic nonbullous eruption who was diagnosed with BP and treated for 3 years based on positive ELISA results in the absence of confirmatory histology or DIF.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and obstructive sleep apnea presented for further evaluation and confirmation of a prior diagnosis of BP by an outside dermatologist. He reported a pruritic rash on the trunk, back, and extremities of 3 years’ duration. He denied occurrence of blisters at any time.

On presentation to an outside dermatologist 3 years ago, a biopsy was performed along with serologic studies due to the patient’s age and the possibility of an urticarial prodrome in BP. The biopsy revealed epidermal acanthosis, subepidermal separation, and a perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the papillary dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was nondiagnostic with a weak discontinuous pattern of IgG and IgA linearly along the basement membrane zone as well as few scattered and clumped cytoid bodies of IgM and IgA. Indirect immunofluoresence revealed a positive IgG titer of 1:40 on monkey esophagus substrate and a positive epidermal pattern on human split-skin substrate with a titer of 1:80. An ELISA for IgG autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 yielded 15 U and 6 U, respectively (cut off value, 9 U). Based on the positive ELISA for IgG against BP180, a diagnosis of BP was made.

Over the following 3 years, the treatment included prednisone, tetracycline, nicotinamide, doxycycline, and dapsone. Therapy was suboptimal due to the patient’s comorbidities and socioeconomic status. Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus precluded consistent use of prednisone as recommended for BP. Tetracycline and nicotinamide were transiently effective in controlling the patient’s symptoms but were discontinued due to changes in his health insurance. Doxycycline and dapsone were ineffective. Throughout this 3-year period, the patient remained blister free, but the pruritic eruption was persistent.

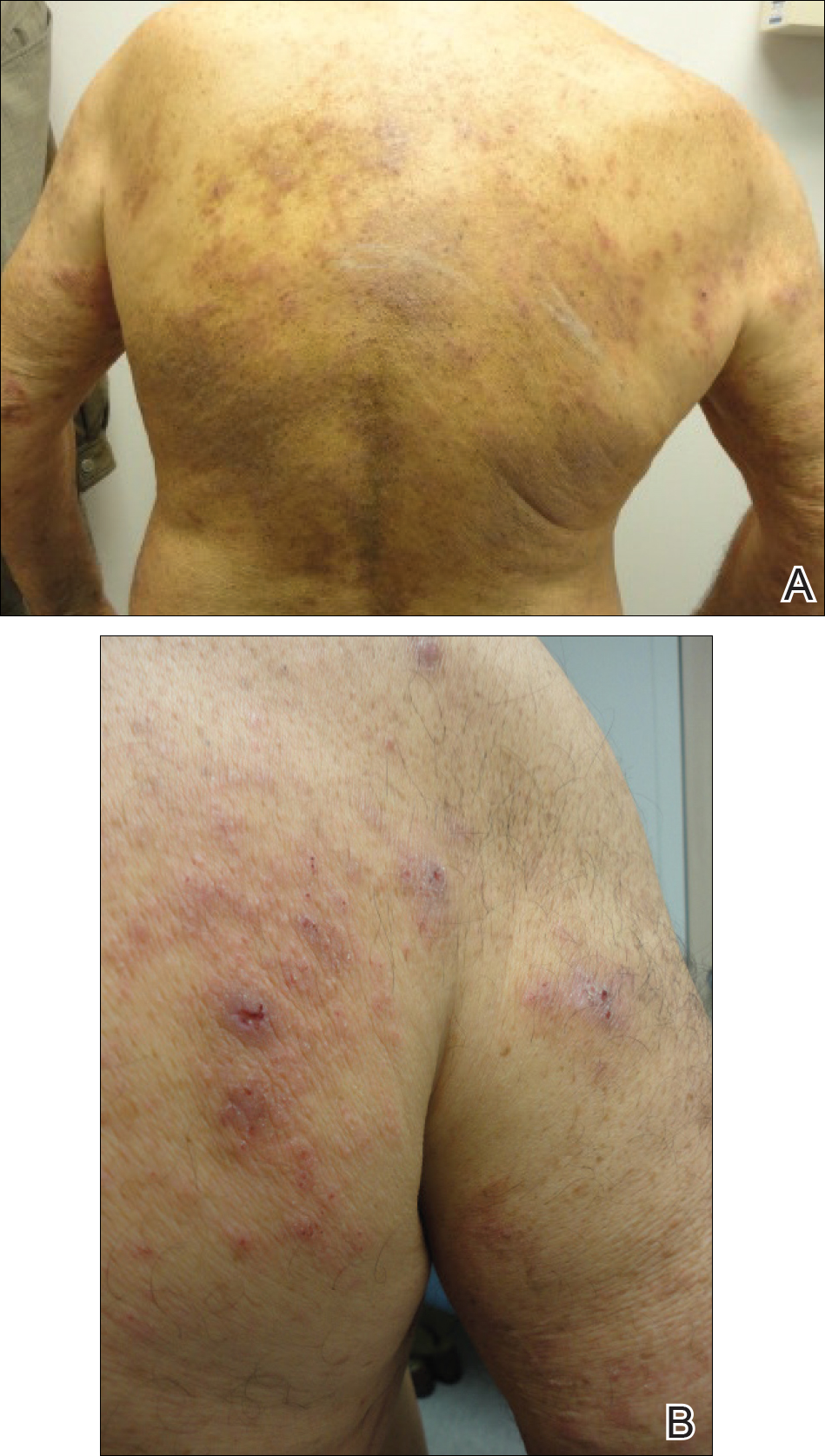

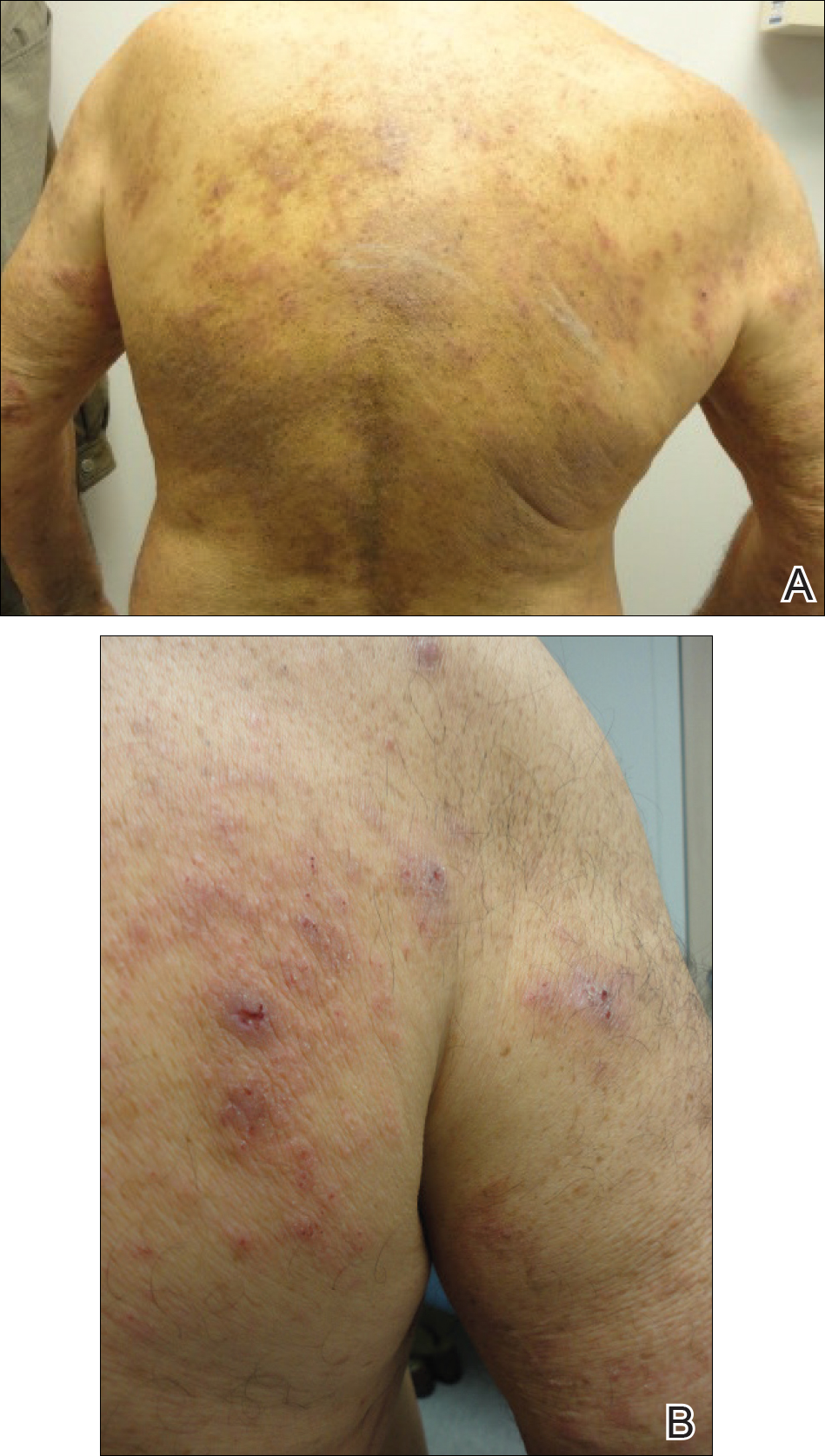

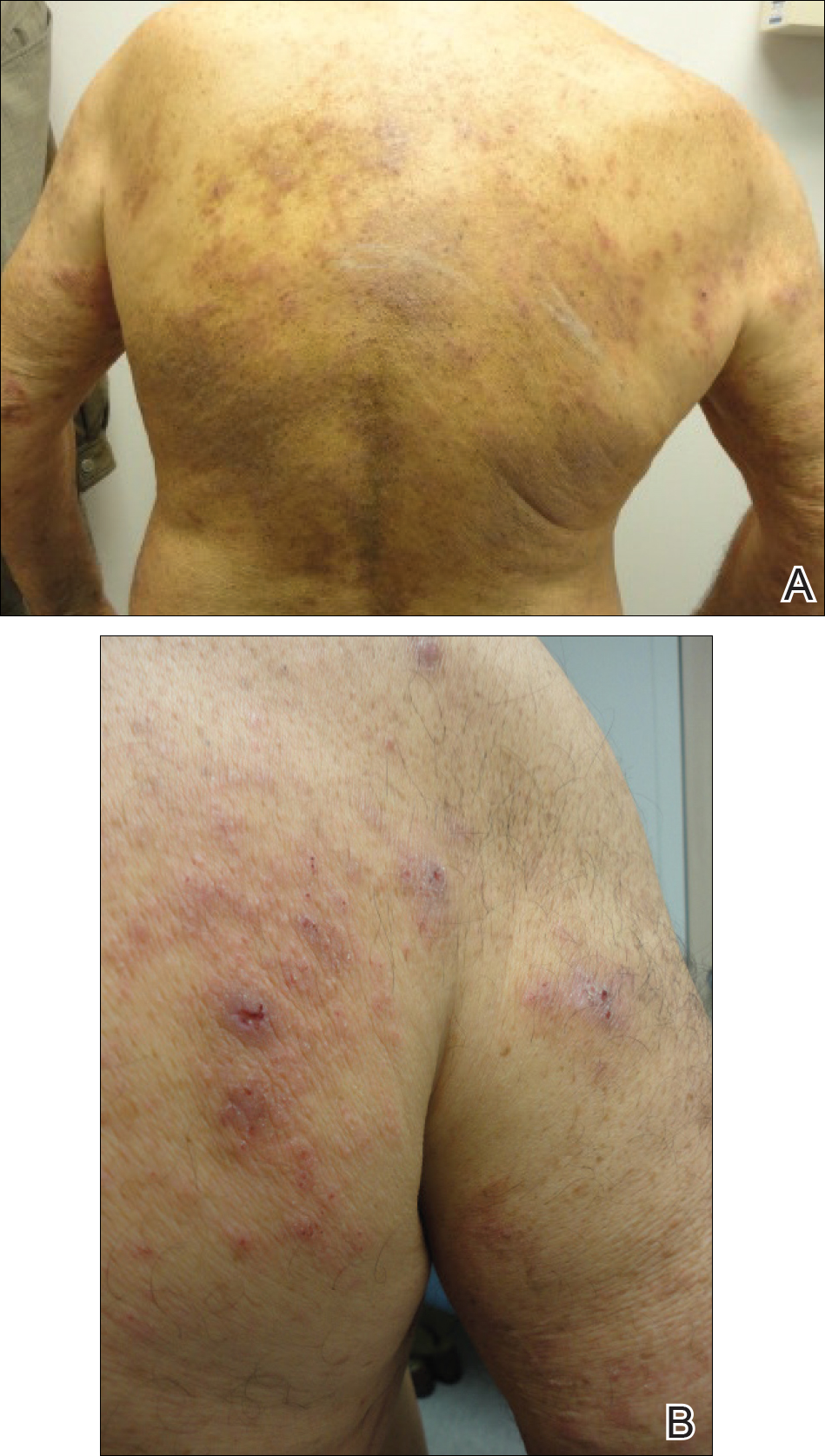

The patient presented to our clinic due to his frustration with the lack of improvement and doubts about the BP diagnosis given the persistent absence of bullous lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous eroded, scaly, crusted papules on erythematous edematous plaques on all extremities, trunk, and back (Figure 1). The head, neck, face, and oral mucosa were spared. His history and clinical findings were atypical for BP and skin biopsies were performed. Histology revealed epidermal erosion with parakeratosis, spongiosis, and superficial perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with rare eosinophils without subepidermal split (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Additionally, further review of the initial histology by another dermatopathologist revealed that the subepidermal separation reported was more likely artifactual clefts. These findings were not consistent with BP.

Given the patient’s clinical history, lack of bullae, and twice-negative DIF, the diagnosis was determined to be more consistent with eczematous spongiotic dermatitis. He refused a referral for phototherapy due to scheduling inconvenience. The patient was started on cyclosporine 0.5 mg/kg twice daily. After 10 days of treatment, he returned for follow-up and reported notable improvement in the pruritus. On physical examination, his dermatitis was improved with decreased erythema and inflammation.

The patient is being continued on extensive dry skin care with thick moisturizers and additional topical corticosteroid application on an as-needed basis.

Comment

Chronic immunosuppression contributes to morbidity and mortality in patients with BP; therefore, accurate diagnosis of BP is of utmost importance.14 A meta-analysis described ELISA as a test with high sensitivity and specificity (87% and 98%–100%, respectively) for diagnosis of BP.3 Nevertheless, there are opportunities for misdiagnosis using ELISA, as demonstrated in our case. To determine if the reported sensitivity and specificity of ELISA is accurate and reliable for clinical use, individual studies from the meta-analysis were reviewed.4,5,7-10,13,15 Issues identified in our review included dissimilar diagnostic procedures and patient populations among individual studies, several reports of positive ELISA in patients without BP, and a lack of explanation for these false-positive results.

There are notable differences in diagnostic procedures and patient populations among reports that establish the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis.3-13 Studies have detected IgG that targets the NC16A domain of the BP180 kD antigen, the C-terminal of the BP180 kD antigen, or the entire ectodomain of the BP180 kD antigen. Study patient populations varied in disease activity, stage, and treatment. Control patients included healthy patients as well as those with many dermatoses, including pemphigus vulgaris, systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, lichen planus, and discoid lupus erythematosus.3-13 Due to these differences between individual studies, we believe the results that determine the overall sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis must be interpreted with caution. For ELISA statistics to be clinically applicable to a specific patient, he/she should be similar to the patients studied. Therefore, we believe each study must be evaluated individually for applicability, given the differences that exist between them.

Furthermore, there have been several reports of false-positive ELISA results in patients with other dermatologic disorders, specifically in elderly patients with pruritus who do not fulfill clinical criteria for diagnosis with BP.16-18 In a population of elderly patients with pruritus for which no specific dermatological or systemic cause was identified, Hofmann et al18 found that 12% (3/25) of patients showed IgG reactivity to BP180 despite having negative DIF results. In another study of elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses, Feliciani et al17 found that 33% (5/15) of patients had IgG reactivity against BP230 or BP180, though they did not fulfill BP criteria based on clinical presentation and showed negative DIF and IIF results. These findings suggest that IgG reactivity against BP autoantibodies as determined by ELISA is not uncommon in pruritic diseases of the elderly.

Explanations for false-positive ELISA results were rare. A few authors suggested that false-positives could be attributed to an excessively low cutoff value,7-9 which was consistent with reports that the titer of autoantibodies to BP180 correlates with disease severity, suggesting that the higher titer of antibodies correlates with more severe disease and likely more accurate diagnosis.10,19,20 It is important to consider that patients who have low titers of BP180 autoantibodies with inconsistent clinical characteristics and DIF results may not truly have BP. Furthermore, to determine the clinical value of ELISA in identifying patients in the initial phase of BP, sera of BP patients should be compared with sera of elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders because they comprise the patient population that often requires diagnosis.18

Given the issues identified in our review of the literature, the published sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis are likely overstated. In conclusion, ELISA should not be relied on as a single criterion adequate for diagnosis of BP.12,21 Rather, the diagnosis of BP can be obtained with a positive predictive value of 95% when a patient meets 3 of 4 clinical criteria (ie, absence of atrophic scars, absence of head and neck involvement, absence of mucosal involvement, and older than 70 years) and demonstrates linear deposits of predominantly IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone of a perilesional biopsy on DIF.15 The gold standard for diagnosis of BP remains clinical presentation along with DIF, which can be supported by histology, IIF, and ELISA.22

- Delaporte E, Dubost-Brama A, Ghohestani R, et al. IgE autoantibodies directed against the major bullous pemphigoid antigen in patients with a severe form of pemphigoid. J Immunol. 1996;157:3642-3647.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Diagnosis and clinical severity markers of bullous pemphigoid. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:15.

- Tampoia M, Giavarina D, Di Giorgio C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to detect anti-skin autoantibodies in autoimmune blistering diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:121-126.

- Zillikens D, Mascaro JM, Rose PA, et al. A highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of circulating anti-BP180 autoantibodies in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:679-683.

- Sitaru C, Dahnrich C, Probst C, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using multimers of the 16th non-collagenous domain of the BP180 antigen for sensitive and specific detection of pemphigoid autoantibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:770-777.

- Yang B, Wang C, Chen S, et al. Evaluation of the combination of BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:722-727.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Oyama N, et al. Evaluation of a BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:126-131.

- Tampoia M, Lattanzi V, Zucano A, et al. Evaluation of a new ELISA assay for detection of BP230 autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:15-20.

- Feng S, Lin L, Jin P, et al. Role of BP180NC16a-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid in China. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:24-28.

- Kobayashi M, Amagai M, Kuroda-Kinoshita K, et al. BP180 ELISA using bacterial recombinant NC16a protein as a diagnostic and monitoring tool for bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:224-232.

- Roussel A, Benichou J, Arivelo Randriamanantany Z, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the combination of bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:293-298.

- Chan, Lawrence S. ELISA instead of indirect IF in patients with BP. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:291-292.

- Barnadas MA, Rubiales V, González J, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence testing in a bullous pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1245-1249.

- Borradori L, Bernard P. Pemphigoid group. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:469.

- Vaillant L, Bernard P, Joly P, et al. Evaluation of clinical criteria for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1075-1080.

- Fania L, Caldarola G, Muller R, et al. IgE recognition of bullous pemphigoid (BP)180 and BP230 in BP patients and elderly individuals with pruritic dermatoses. Clin Immunol. 2012;143:236-245.

- Feliciani C, Caldarola G, Kneisel A, et al. IgG autoantibody reactivity against bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and BP230 in elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2009;61:306-312.

- Hofmann SC, Tamm K, Hertl M, et al. Diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using BP180 recombinant proteins in elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:910-911.

- Schmidt E, Obe K, Brocker EB, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:174-178.

- Feng S, Wu Q, Jin P, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:225-228.

- Di Zenzo G, Joly P, Zambruno G, et al. Sensitivity of immunofluorescence studies vs enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1454-1456.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:84-89.

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease. The classic presentation of BP is a generalized, pruritic, bullous eruption in elderly patients, which is occasionally preceded by an urticarial prodrome. Immunopathologically, BP is characterized by IgG and sometimes IgE autoantibodies that target basement membrane zone proteins BP180 and BP230 of the epidermis.1

The diagnosis of BP should be suspected when an elderly patient presents with tense blisters and can be confirmed via diagnostic testing, including tissue histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as the gold standard, as well as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and most recently biochip technology as supportive tests.2 Since its advent, ELISA has gained popularity as a trustworthy diagnostic test for BP. The specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis is reported to be 98% to 100%, which leads clinicians to believe that a positive ELISA equals certain diagnosis of BP; however, misdiagnosis of BP based on a positive ELISA result can occur.3-13 The treatment of BP often involves lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. Complications of immunosuppressive therapy contribute to morbidity and mortality in these patients, thus an accurate diagnosis is paramount before introducing therapy.14

We present the case of a 74-year-old man with a history of a pruritic nonbullous eruption who was diagnosed with BP and treated for 3 years based on positive ELISA results in the absence of confirmatory histology or DIF.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and obstructive sleep apnea presented for further evaluation and confirmation of a prior diagnosis of BP by an outside dermatologist. He reported a pruritic rash on the trunk, back, and extremities of 3 years’ duration. He denied occurrence of blisters at any time.

On presentation to an outside dermatologist 3 years ago, a biopsy was performed along with serologic studies due to the patient’s age and the possibility of an urticarial prodrome in BP. The biopsy revealed epidermal acanthosis, subepidermal separation, and a perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the papillary dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was nondiagnostic with a weak discontinuous pattern of IgG and IgA linearly along the basement membrane zone as well as few scattered and clumped cytoid bodies of IgM and IgA. Indirect immunofluoresence revealed a positive IgG titer of 1:40 on monkey esophagus substrate and a positive epidermal pattern on human split-skin substrate with a titer of 1:80. An ELISA for IgG autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 yielded 15 U and 6 U, respectively (cut off value, 9 U). Based on the positive ELISA for IgG against BP180, a diagnosis of BP was made.

Over the following 3 years, the treatment included prednisone, tetracycline, nicotinamide, doxycycline, and dapsone. Therapy was suboptimal due to the patient’s comorbidities and socioeconomic status. Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus precluded consistent use of prednisone as recommended for BP. Tetracycline and nicotinamide were transiently effective in controlling the patient’s symptoms but were discontinued due to changes in his health insurance. Doxycycline and dapsone were ineffective. Throughout this 3-year period, the patient remained blister free, but the pruritic eruption was persistent.

The patient presented to our clinic due to his frustration with the lack of improvement and doubts about the BP diagnosis given the persistent absence of bullous lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous eroded, scaly, crusted papules on erythematous edematous plaques on all extremities, trunk, and back (Figure 1). The head, neck, face, and oral mucosa were spared. His history and clinical findings were atypical for BP and skin biopsies were performed. Histology revealed epidermal erosion with parakeratosis, spongiosis, and superficial perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with rare eosinophils without subepidermal split (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Additionally, further review of the initial histology by another dermatopathologist revealed that the subepidermal separation reported was more likely artifactual clefts. These findings were not consistent with BP.

Given the patient’s clinical history, lack of bullae, and twice-negative DIF, the diagnosis was determined to be more consistent with eczematous spongiotic dermatitis. He refused a referral for phototherapy due to scheduling inconvenience. The patient was started on cyclosporine 0.5 mg/kg twice daily. After 10 days of treatment, he returned for follow-up and reported notable improvement in the pruritus. On physical examination, his dermatitis was improved with decreased erythema and inflammation.

The patient is being continued on extensive dry skin care with thick moisturizers and additional topical corticosteroid application on an as-needed basis.

Comment

Chronic immunosuppression contributes to morbidity and mortality in patients with BP; therefore, accurate diagnosis of BP is of utmost importance.14 A meta-analysis described ELISA as a test with high sensitivity and specificity (87% and 98%–100%, respectively) for diagnosis of BP.3 Nevertheless, there are opportunities for misdiagnosis using ELISA, as demonstrated in our case. To determine if the reported sensitivity and specificity of ELISA is accurate and reliable for clinical use, individual studies from the meta-analysis were reviewed.4,5,7-10,13,15 Issues identified in our review included dissimilar diagnostic procedures and patient populations among individual studies, several reports of positive ELISA in patients without BP, and a lack of explanation for these false-positive results.

There are notable differences in diagnostic procedures and patient populations among reports that establish the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis.3-13 Studies have detected IgG that targets the NC16A domain of the BP180 kD antigen, the C-terminal of the BP180 kD antigen, or the entire ectodomain of the BP180 kD antigen. Study patient populations varied in disease activity, stage, and treatment. Control patients included healthy patients as well as those with many dermatoses, including pemphigus vulgaris, systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, lichen planus, and discoid lupus erythematosus.3-13 Due to these differences between individual studies, we believe the results that determine the overall sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis must be interpreted with caution. For ELISA statistics to be clinically applicable to a specific patient, he/she should be similar to the patients studied. Therefore, we believe each study must be evaluated individually for applicability, given the differences that exist between them.

Furthermore, there have been several reports of false-positive ELISA results in patients with other dermatologic disorders, specifically in elderly patients with pruritus who do not fulfill clinical criteria for diagnosis with BP.16-18 In a population of elderly patients with pruritus for which no specific dermatological or systemic cause was identified, Hofmann et al18 found that 12% (3/25) of patients showed IgG reactivity to BP180 despite having negative DIF results. In another study of elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses, Feliciani et al17 found that 33% (5/15) of patients had IgG reactivity against BP230 or BP180, though they did not fulfill BP criteria based on clinical presentation and showed negative DIF and IIF results. These findings suggest that IgG reactivity against BP autoantibodies as determined by ELISA is not uncommon in pruritic diseases of the elderly.

Explanations for false-positive ELISA results were rare. A few authors suggested that false-positives could be attributed to an excessively low cutoff value,7-9 which was consistent with reports that the titer of autoantibodies to BP180 correlates with disease severity, suggesting that the higher titer of antibodies correlates with more severe disease and likely more accurate diagnosis.10,19,20 It is important to consider that patients who have low titers of BP180 autoantibodies with inconsistent clinical characteristics and DIF results may not truly have BP. Furthermore, to determine the clinical value of ELISA in identifying patients in the initial phase of BP, sera of BP patients should be compared with sera of elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders because they comprise the patient population that often requires diagnosis.18

Given the issues identified in our review of the literature, the published sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis are likely overstated. In conclusion, ELISA should not be relied on as a single criterion adequate for diagnosis of BP.12,21 Rather, the diagnosis of BP can be obtained with a positive predictive value of 95% when a patient meets 3 of 4 clinical criteria (ie, absence of atrophic scars, absence of head and neck involvement, absence of mucosal involvement, and older than 70 years) and demonstrates linear deposits of predominantly IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone of a perilesional biopsy on DIF.15 The gold standard for diagnosis of BP remains clinical presentation along with DIF, which can be supported by histology, IIF, and ELISA.22

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease. The classic presentation of BP is a generalized, pruritic, bullous eruption in elderly patients, which is occasionally preceded by an urticarial prodrome. Immunopathologically, BP is characterized by IgG and sometimes IgE autoantibodies that target basement membrane zone proteins BP180 and BP230 of the epidermis.1

The diagnosis of BP should be suspected when an elderly patient presents with tense blisters and can be confirmed via diagnostic testing, including tissue histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as the gold standard, as well as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and most recently biochip technology as supportive tests.2 Since its advent, ELISA has gained popularity as a trustworthy diagnostic test for BP. The specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis is reported to be 98% to 100%, which leads clinicians to believe that a positive ELISA equals certain diagnosis of BP; however, misdiagnosis of BP based on a positive ELISA result can occur.3-13 The treatment of BP often involves lifelong immunosuppressive therapy. Complications of immunosuppressive therapy contribute to morbidity and mortality in these patients, thus an accurate diagnosis is paramount before introducing therapy.14

We present the case of a 74-year-old man with a history of a pruritic nonbullous eruption who was diagnosed with BP and treated for 3 years based on positive ELISA results in the absence of confirmatory histology or DIF.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and obstructive sleep apnea presented for further evaluation and confirmation of a prior diagnosis of BP by an outside dermatologist. He reported a pruritic rash on the trunk, back, and extremities of 3 years’ duration. He denied occurrence of blisters at any time.

On presentation to an outside dermatologist 3 years ago, a biopsy was performed along with serologic studies due to the patient’s age and the possibility of an urticarial prodrome in BP. The biopsy revealed epidermal acanthosis, subepidermal separation, and a perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the papillary dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was nondiagnostic with a weak discontinuous pattern of IgG and IgA linearly along the basement membrane zone as well as few scattered and clumped cytoid bodies of IgM and IgA. Indirect immunofluoresence revealed a positive IgG titer of 1:40 on monkey esophagus substrate and a positive epidermal pattern on human split-skin substrate with a titer of 1:80. An ELISA for IgG autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 yielded 15 U and 6 U, respectively (cut off value, 9 U). Based on the positive ELISA for IgG against BP180, a diagnosis of BP was made.

Over the following 3 years, the treatment included prednisone, tetracycline, nicotinamide, doxycycline, and dapsone. Therapy was suboptimal due to the patient’s comorbidities and socioeconomic status. Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus precluded consistent use of prednisone as recommended for BP. Tetracycline and nicotinamide were transiently effective in controlling the patient’s symptoms but were discontinued due to changes in his health insurance. Doxycycline and dapsone were ineffective. Throughout this 3-year period, the patient remained blister free, but the pruritic eruption was persistent.

The patient presented to our clinic due to his frustration with the lack of improvement and doubts about the BP diagnosis given the persistent absence of bullous lesions. Physical examination revealed numerous eroded, scaly, crusted papules on erythematous edematous plaques on all extremities, trunk, and back (Figure 1). The head, neck, face, and oral mucosa were spared. His history and clinical findings were atypical for BP and skin biopsies were performed. Histology revealed epidermal erosion with parakeratosis, spongiosis, and superficial perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with rare eosinophils without subepidermal split (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Additionally, further review of the initial histology by another dermatopathologist revealed that the subepidermal separation reported was more likely artifactual clefts. These findings were not consistent with BP.

Given the patient’s clinical history, lack of bullae, and twice-negative DIF, the diagnosis was determined to be more consistent with eczematous spongiotic dermatitis. He refused a referral for phototherapy due to scheduling inconvenience. The patient was started on cyclosporine 0.5 mg/kg twice daily. After 10 days of treatment, he returned for follow-up and reported notable improvement in the pruritus. On physical examination, his dermatitis was improved with decreased erythema and inflammation.

The patient is being continued on extensive dry skin care with thick moisturizers and additional topical corticosteroid application on an as-needed basis.

Comment

Chronic immunosuppression contributes to morbidity and mortality in patients with BP; therefore, accurate diagnosis of BP is of utmost importance.14 A meta-analysis described ELISA as a test with high sensitivity and specificity (87% and 98%–100%, respectively) for diagnosis of BP.3 Nevertheless, there are opportunities for misdiagnosis using ELISA, as demonstrated in our case. To determine if the reported sensitivity and specificity of ELISA is accurate and reliable for clinical use, individual studies from the meta-analysis were reviewed.4,5,7-10,13,15 Issues identified in our review included dissimilar diagnostic procedures and patient populations among individual studies, several reports of positive ELISA in patients without BP, and a lack of explanation for these false-positive results.

There are notable differences in diagnostic procedures and patient populations among reports that establish the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis.3-13 Studies have detected IgG that targets the NC16A domain of the BP180 kD antigen, the C-terminal of the BP180 kD antigen, or the entire ectodomain of the BP180 kD antigen. Study patient populations varied in disease activity, stage, and treatment. Control patients included healthy patients as well as those with many dermatoses, including pemphigus vulgaris, systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, lichen planus, and discoid lupus erythematosus.3-13 Due to these differences between individual studies, we believe the results that determine the overall sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis must be interpreted with caution. For ELISA statistics to be clinically applicable to a specific patient, he/she should be similar to the patients studied. Therefore, we believe each study must be evaluated individually for applicability, given the differences that exist between them.

Furthermore, there have been several reports of false-positive ELISA results in patients with other dermatologic disorders, specifically in elderly patients with pruritus who do not fulfill clinical criteria for diagnosis with BP.16-18 In a population of elderly patients with pruritus for which no specific dermatological or systemic cause was identified, Hofmann et al18 found that 12% (3/25) of patients showed IgG reactivity to BP180 despite having negative DIF results. In another study of elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses, Feliciani et al17 found that 33% (5/15) of patients had IgG reactivity against BP230 or BP180, though they did not fulfill BP criteria based on clinical presentation and showed negative DIF and IIF results. These findings suggest that IgG reactivity against BP autoantibodies as determined by ELISA is not uncommon in pruritic diseases of the elderly.

Explanations for false-positive ELISA results were rare. A few authors suggested that false-positives could be attributed to an excessively low cutoff value,7-9 which was consistent with reports that the titer of autoantibodies to BP180 correlates with disease severity, suggesting that the higher titer of antibodies correlates with more severe disease and likely more accurate diagnosis.10,19,20 It is important to consider that patients who have low titers of BP180 autoantibodies with inconsistent clinical characteristics and DIF results may not truly have BP. Furthermore, to determine the clinical value of ELISA in identifying patients in the initial phase of BP, sera of BP patients should be compared with sera of elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders because they comprise the patient population that often requires diagnosis.18

Given the issues identified in our review of the literature, the published sensitivity and specificity of ELISA for BP diagnosis are likely overstated. In conclusion, ELISA should not be relied on as a single criterion adequate for diagnosis of BP.12,21 Rather, the diagnosis of BP can be obtained with a positive predictive value of 95% when a patient meets 3 of 4 clinical criteria (ie, absence of atrophic scars, absence of head and neck involvement, absence of mucosal involvement, and older than 70 years) and demonstrates linear deposits of predominantly IgG and/or C3 along the basement membrane zone of a perilesional biopsy on DIF.15 The gold standard for diagnosis of BP remains clinical presentation along with DIF, which can be supported by histology, IIF, and ELISA.22

- Delaporte E, Dubost-Brama A, Ghohestani R, et al. IgE autoantibodies directed against the major bullous pemphigoid antigen in patients with a severe form of pemphigoid. J Immunol. 1996;157:3642-3647.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Diagnosis and clinical severity markers of bullous pemphigoid. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:15.

- Tampoia M, Giavarina D, Di Giorgio C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to detect anti-skin autoantibodies in autoimmune blistering diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:121-126.

- Zillikens D, Mascaro JM, Rose PA, et al. A highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of circulating anti-BP180 autoantibodies in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:679-683.

- Sitaru C, Dahnrich C, Probst C, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using multimers of the 16th non-collagenous domain of the BP180 antigen for sensitive and specific detection of pemphigoid autoantibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:770-777.

- Yang B, Wang C, Chen S, et al. Evaluation of the combination of BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:722-727.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Oyama N, et al. Evaluation of a BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:126-131.

- Tampoia M, Lattanzi V, Zucano A, et al. Evaluation of a new ELISA assay for detection of BP230 autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:15-20.

- Feng S, Lin L, Jin P, et al. Role of BP180NC16a-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid in China. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:24-28.

- Kobayashi M, Amagai M, Kuroda-Kinoshita K, et al. BP180 ELISA using bacterial recombinant NC16a protein as a diagnostic and monitoring tool for bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:224-232.

- Roussel A, Benichou J, Arivelo Randriamanantany Z, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the combination of bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:293-298.

- Chan, Lawrence S. ELISA instead of indirect IF in patients with BP. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:291-292.

- Barnadas MA, Rubiales V, González J, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence testing in a bullous pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1245-1249.

- Borradori L, Bernard P. Pemphigoid group. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:469.

- Vaillant L, Bernard P, Joly P, et al. Evaluation of clinical criteria for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1075-1080.

- Fania L, Caldarola G, Muller R, et al. IgE recognition of bullous pemphigoid (BP)180 and BP230 in BP patients and elderly individuals with pruritic dermatoses. Clin Immunol. 2012;143:236-245.

- Feliciani C, Caldarola G, Kneisel A, et al. IgG autoantibody reactivity against bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and BP230 in elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2009;61:306-312.

- Hofmann SC, Tamm K, Hertl M, et al. Diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using BP180 recombinant proteins in elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:910-911.

- Schmidt E, Obe K, Brocker EB, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:174-178.

- Feng S, Wu Q, Jin P, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:225-228.

- Di Zenzo G, Joly P, Zambruno G, et al. Sensitivity of immunofluorescence studies vs enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1454-1456.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:84-89.

- Delaporte E, Dubost-Brama A, Ghohestani R, et al. IgE autoantibodies directed against the major bullous pemphigoid antigen in patients with a severe form of pemphigoid. J Immunol. 1996;157:3642-3647.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Diagnosis and clinical severity markers of bullous pemphigoid. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:15.

- Tampoia M, Giavarina D, Di Giorgio C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to detect anti-skin autoantibodies in autoimmune blistering diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:121-126.

- Zillikens D, Mascaro JM, Rose PA, et al. A highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of circulating anti-BP180 autoantibodies in patients with bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:679-683.

- Sitaru C, Dahnrich C, Probst C, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using multimers of the 16th non-collagenous domain of the BP180 antigen for sensitive and specific detection of pemphigoid autoantibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:770-777.

- Yang B, Wang C, Chen S, et al. Evaluation of the combination of BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:722-727.

- Sakuma-Oyama Y, Powell AM, Oyama N, et al. Evaluation of a BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:126-131.

- Tampoia M, Lattanzi V, Zucano A, et al. Evaluation of a new ELISA assay for detection of BP230 autoantibodies in bullous pemphigoid. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:15-20.

- Feng S, Lin L, Jin P, et al. Role of BP180NC16a-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid in China. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:24-28.

- Kobayashi M, Amagai M, Kuroda-Kinoshita K, et al. BP180 ELISA using bacterial recombinant NC16a protein as a diagnostic and monitoring tool for bullous pemphigoid. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:224-232.

- Roussel A, Benichou J, Arivelo Randriamanantany Z, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the combination of bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 in the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:293-298.

- Chan, Lawrence S. ELISA instead of indirect IF in patients with BP. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:291-292.

- Barnadas MA, Rubiales V, González J, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence testing in a bullous pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1245-1249.

- Borradori L, Bernard P. Pemphigoid group. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:469.

- Vaillant L, Bernard P, Joly P, et al. Evaluation of clinical criteria for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1075-1080.

- Fania L, Caldarola G, Muller R, et al. IgE recognition of bullous pemphigoid (BP)180 and BP230 in BP patients and elderly individuals with pruritic dermatoses. Clin Immunol. 2012;143:236-245.

- Feliciani C, Caldarola G, Kneisel A, et al. IgG autoantibody reactivity against bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and BP230 in elderly patients with pruritic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2009;61:306-312.

- Hofmann SC, Tamm K, Hertl M, et al. Diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using BP180 recombinant proteins in elderly patients with pruritic skin disorders. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:910-911.

- Schmidt E, Obe K, Brocker EB, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:174-178.

- Feng S, Wu Q, Jin P, et al. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:225-228.

- Di Zenzo G, Joly P, Zambruno G, et al. Sensitivity of immunofluorescence studies vs enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1454-1456.

- Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:84-89.

Practice Points

- A low serum level of autoantibodies to BP180 should be interpreted with caution because it is more likely to represent a false-positive than a high serum level.

- Rely on the gold standard for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid: clinical presentation along with direct immunofluorescence, which can be supported by histology, indirect immunofluorescence, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) rather than ELISA alone.

Proper Wound Management: How to Work With Patients

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A thorough patient history is imperative for proper diagnosis of wounds, thus detailed information on the onset, duration, temporality, modifying factors, symptoms, and attempted treatments should be provided. Associated comorbidities that may influence wound healing, such as diabetes mellitus or connective tissue diseases, must be considered when formulating a treatment regimen. Patients should disclose current medications, as certain medications (eg, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors) may decrease vascularization or soft tissue matrix regeneration, further complicating the wound healing process. All patients should have a basic understanding of the cause of their wound to have realistic expectations of the prognosis.

What are your go-to treatments?

Treatment ultimately depends on the cause of the wound. In general, proper healing requires a wound bed that is well vascularized and moistened without devitalized tissue or bacterial colonization. Wound dressings should be utilized to reduce dead space, control exudate, prevent bacterial overgrowth, and ensure proper fluid balance. Maintaining good overall health promotes proper healing. Thus, any relevant underlying medical conditions should be properly managed (eg, glycemic control for diabetic patients, management of fluid overload in patients with congestive heart failure).

When treating wounds, it is important to consider several factors. Although all wounds are colonized with microbes, not all wounds are infected. Thus, antibiotic therapy is not necessary for all wounds and should only be used to treat wounds that are clinically infected. Rule out pyoderma gangrenosum prior to wound debridement, as the associated pathergic response will notably worsen the ulcer. Wound dressings have an impact on the speed of wound healing, strength of repaired skin, and cosmetic appearance. Because no single dressing is perfect for all wounds, physicians should use their discretion when determining the type of wound dressing necessary.

Certain wounds require specific treatments. Off-loading and compression dressings/garments are the main components involved in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Protective wound care in conjunction with glycemic control is imperative for diabetic ulcers. Often, the causes of wounds are multifactorial and may complicate treatment. For instance, it is important to confirm that there is no associated arterial insufficiency before treating venous insufficiency with compression. Furthermore, patients with diabetic ulcers in association with venous insufficiency often have minimal response to hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

Several agents have been implicated to improve wound healing. Timolol, a topically applied beta-blocker, may promote keratinocyte migration and epithelialization of chronic refractory wounds. Recombinant human growth factors, most notably becaplermin (a platelet-derived growth factor), have been developed to promote cellular proliferation and angiogenesis, thereby improving healing of chronic wounds. Wounds that have devitalized tissue or contamination require debridement prior to further management.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Because recurrence is a common complication of chronic wounds, it is imperative that patients understand the importance of preventive care and follow-up appointments. Additionally, an open patient-physician dialogue may help address potential lifestyle limitations that may complicate wound care treatment. For instance, home care arrangement may be necessary to assist certain patient populations with wound care management.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

Ultimately, it is hard to enforce treatment if the patient refuses. However, in my experience practicing dermatology, I have found it to be uncommon for patients to refuse treatment without a particular reason. If a patient refuses treatment, try to understand why and then try to alleviate any concerns by clarifying misconceptions and/or recommending alternative therapies.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

Consult the American Academy of Dermatology website (https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Unassigned/Wound-Dressings_Online-BF-DIR-Summer-2016--FINAL.pdf) for more information.

Additional resources include:

- Diabetic Wound Care (Source: American Podiatric Medical Association)(http://www.apma.org/Learn/FootHealth.cfm?ItemNumber=981)

- Pyoderma Gangrenosum (Source: Wound Care Centers)(http://www.woundcarecenters.org/article/wound-types/pyoderma-gangrenosum)

- Take the Pressure Off: A Patient Guide for Preventing and Treating Pressure Ulcers (Source: Association for the Advancement of Wound Care)(http://aawconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Take-the-Pressure-Off.pdf)

- Wound Healing Society (http://woundheal.org/home.aspx)