User login

Three popular IBS diets found equivalent

Three widely followed diets for nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) produce similar results, but traditional dietary advice (TDA) is easier to follow, researchers say.

“We recommend TDA as the first-choice dietary option due to its widespread availability and patient friendliness,” Anupam Rej, MBChB, from Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in Sheffield, England, and colleagues write.

According to their study, about half the people following each of three diets – TDA; gluten-free; and low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) – reported at least a 50% reduction in their symptoms.

They noted, however, that the low-FODMAP diet produced the most improvement in depression and dysphoria.

The study was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

What the dietary options entailed

The three diets have different origins and methodologies, but all are designed to reduce the abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits that characterize IBS.

TDA is based on recommendations of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the British Dietetic Association. It includes “sensible eating patterns,” such as regular meals, never having too much or too little, and sufficient hydration. It calls for a reduction in alcoholic, caffeinated, and “fizzy” drinks; spicy, fatty, and processed foods; fresh fruit (a maximum of three per day); and fiber and other gas-producing foods, such as beans, bread, and sweeteners. It also asks people to address any perceived food intolerance, such as dairy.

In North America, the low-FODMAP diet is prescribed as first-line therapy, and the American College of Gastroenterology has given it a conditional recommendation.

FODMAPs are short-chain fermentable carbohydrates found in many fruits, vegetables, dairy products, artificial sweeteners, and wheat. They increase small intestinal water volume and colonic gas production that can induce gastrointestinal symptoms in people with visceral hypersensitivity.

People following the low-FODMAP diet start by eliminating all FODMAPs for 4-6 weeks, then gradually reintroducing them to determine which are most likely to trigger symptoms.

A gluten-free diet, inspired by what is prescribed to treat celiac disease, has gained popularity in recent years. Although researchers debate the mechanism by which this diet improves symptoms, one leading theory is a reduction in fructans that accompany gluten in foods such as bread.

A rare head-to-head comparison trial

The low-FODMAP diet has proved itself in more clinical trials than the other two approaches, but few, if any, trials have compared them head-to-head in a pragmatic randomized trial, Dr. Rej and colleagues found after reviewing the literature.

They set about filling this gap by recruiting 114 people with IBS and randomly assigning each of them to one of the diets. Ninety-nine people finished the trial, with 33 following each of the diets. People with IBS-constipation were excluded.

Participants were a mean age of 37 years. Seventy-one percent were female, and 88% were White. Their mean IBS symptom severity score was 301, with 9% rating their symptoms as mild, 47% as moderate, and 45% as severe.

The proportion who reported at least a 50% reduction in their symptoms was 58% for the gluten-free diet, 55% for the low-FODMAP diet, and 42% for the TDA. The differences in these proportions were not significant (P = .43).

The diets worked about as well regardless of whether the patients had IBS with diarrhea or IBS with mixed diarrhea and constipation.

More of the people on the low-FODMAP diet reported significant improvement in their depression and dysphoria than people on the other two diets.

Changes in anxiety, somatization, and other aspects of IBS quality of life didn’t differ significantly with diet.

Where the diets differ: cost and ease

Fewer people following the TDA rated it as expensive, difficult, or socially awkward, compared with the people following the other two diets.

More of those following the TDA and gluten-free diet found them easy to incorporate into their lives than those following the low-FODMAP diet. About two-thirds of the people in each of these groups said they would consider continuing their diets after the end of the study.

The proportion of people consuming the recommended dietary reference values for macronutrients did not change with any of the diets. However, those in the TDA group reduced their intake of potassium and iron. In the other groups, the researchers noted a reduction in thiamine and magnesium.

Because of COVID-19 restrictions, the researchers were able to collect stool samples from only half of participants. What they did collect showed no difference among the groups in dysbiosis index or functional bacterial profiles.

Baseline factors such as age, gender, IBS subtype, dysbiosis index, somatization, and mood did not predict response to the three diets.

Participants improved as much whether they received dietary instructions face-to-face or through a live virtual consultation.

Applications and limitations

At least one previous study showed that the low-FODMAP diet produced better results than the standard diets patients had been following, said Brian E. Lacy, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., who was not involved in the current study.

He agreed with the study’s conclusion that the TDA could be a good place for people with IBS to start.

“Based on their research, and the findings that patients thought the diet was less expensive, easier to follow, and easier to shop for, this is a reasonable approach,” he told this news organization. “However, if there’s no benefit with the traditional diet, then moving on to the more rigorous low-FODMAP diet makes sense to me.”

Study limitations include a short duration, lack of information about how patients can add foods back into their diet (particularly with the low-FODMAP diet), and insufficient sample size and lack of a placebo group contributing to an inability to detect all clinically significant differences among the diets, he said.

“Although this study is not definitive and doesn’t answer all key questions about which diet is best and how each performs in the long run, it does provide important information for patients and providers,” said Dr. Lacy.

The study was funded by Schaer. One of the study authors has reported receiving an educational grant from Schaer. Dr. Lacy has reported being on scientific advisory boards for Ironwood, Salix, and Allakos.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three widely followed diets for nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) produce similar results, but traditional dietary advice (TDA) is easier to follow, researchers say.

“We recommend TDA as the first-choice dietary option due to its widespread availability and patient friendliness,” Anupam Rej, MBChB, from Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in Sheffield, England, and colleagues write.

According to their study, about half the people following each of three diets – TDA; gluten-free; and low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) – reported at least a 50% reduction in their symptoms.

They noted, however, that the low-FODMAP diet produced the most improvement in depression and dysphoria.

The study was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

What the dietary options entailed

The three diets have different origins and methodologies, but all are designed to reduce the abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits that characterize IBS.

TDA is based on recommendations of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the British Dietetic Association. It includes “sensible eating patterns,” such as regular meals, never having too much or too little, and sufficient hydration. It calls for a reduction in alcoholic, caffeinated, and “fizzy” drinks; spicy, fatty, and processed foods; fresh fruit (a maximum of three per day); and fiber and other gas-producing foods, such as beans, bread, and sweeteners. It also asks people to address any perceived food intolerance, such as dairy.

In North America, the low-FODMAP diet is prescribed as first-line therapy, and the American College of Gastroenterology has given it a conditional recommendation.

FODMAPs are short-chain fermentable carbohydrates found in many fruits, vegetables, dairy products, artificial sweeteners, and wheat. They increase small intestinal water volume and colonic gas production that can induce gastrointestinal symptoms in people with visceral hypersensitivity.

People following the low-FODMAP diet start by eliminating all FODMAPs for 4-6 weeks, then gradually reintroducing them to determine which are most likely to trigger symptoms.

A gluten-free diet, inspired by what is prescribed to treat celiac disease, has gained popularity in recent years. Although researchers debate the mechanism by which this diet improves symptoms, one leading theory is a reduction in fructans that accompany gluten in foods such as bread.

A rare head-to-head comparison trial

The low-FODMAP diet has proved itself in more clinical trials than the other two approaches, but few, if any, trials have compared them head-to-head in a pragmatic randomized trial, Dr. Rej and colleagues found after reviewing the literature.

They set about filling this gap by recruiting 114 people with IBS and randomly assigning each of them to one of the diets. Ninety-nine people finished the trial, with 33 following each of the diets. People with IBS-constipation were excluded.

Participants were a mean age of 37 years. Seventy-one percent were female, and 88% were White. Their mean IBS symptom severity score was 301, with 9% rating their symptoms as mild, 47% as moderate, and 45% as severe.

The proportion who reported at least a 50% reduction in their symptoms was 58% for the gluten-free diet, 55% for the low-FODMAP diet, and 42% for the TDA. The differences in these proportions were not significant (P = .43).

The diets worked about as well regardless of whether the patients had IBS with diarrhea or IBS with mixed diarrhea and constipation.

More of the people on the low-FODMAP diet reported significant improvement in their depression and dysphoria than people on the other two diets.

Changes in anxiety, somatization, and other aspects of IBS quality of life didn’t differ significantly with diet.

Where the diets differ: cost and ease

Fewer people following the TDA rated it as expensive, difficult, or socially awkward, compared with the people following the other two diets.

More of those following the TDA and gluten-free diet found them easy to incorporate into their lives than those following the low-FODMAP diet. About two-thirds of the people in each of these groups said they would consider continuing their diets after the end of the study.

The proportion of people consuming the recommended dietary reference values for macronutrients did not change with any of the diets. However, those in the TDA group reduced their intake of potassium and iron. In the other groups, the researchers noted a reduction in thiamine and magnesium.

Because of COVID-19 restrictions, the researchers were able to collect stool samples from only half of participants. What they did collect showed no difference among the groups in dysbiosis index or functional bacterial profiles.

Baseline factors such as age, gender, IBS subtype, dysbiosis index, somatization, and mood did not predict response to the three diets.

Participants improved as much whether they received dietary instructions face-to-face or through a live virtual consultation.

Applications and limitations

At least one previous study showed that the low-FODMAP diet produced better results than the standard diets patients had been following, said Brian E. Lacy, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., who was not involved in the current study.

He agreed with the study’s conclusion that the TDA could be a good place for people with IBS to start.

“Based on their research, and the findings that patients thought the diet was less expensive, easier to follow, and easier to shop for, this is a reasonable approach,” he told this news organization. “However, if there’s no benefit with the traditional diet, then moving on to the more rigorous low-FODMAP diet makes sense to me.”

Study limitations include a short duration, lack of information about how patients can add foods back into their diet (particularly with the low-FODMAP diet), and insufficient sample size and lack of a placebo group contributing to an inability to detect all clinically significant differences among the diets, he said.

“Although this study is not definitive and doesn’t answer all key questions about which diet is best and how each performs in the long run, it does provide important information for patients and providers,” said Dr. Lacy.

The study was funded by Schaer. One of the study authors has reported receiving an educational grant from Schaer. Dr. Lacy has reported being on scientific advisory boards for Ironwood, Salix, and Allakos.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three widely followed diets for nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) produce similar results, but traditional dietary advice (TDA) is easier to follow, researchers say.

“We recommend TDA as the first-choice dietary option due to its widespread availability and patient friendliness,” Anupam Rej, MBChB, from Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in Sheffield, England, and colleagues write.

According to their study, about half the people following each of three diets – TDA; gluten-free; and low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) – reported at least a 50% reduction in their symptoms.

They noted, however, that the low-FODMAP diet produced the most improvement in depression and dysphoria.

The study was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

What the dietary options entailed

The three diets have different origins and methodologies, but all are designed to reduce the abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits that characterize IBS.

TDA is based on recommendations of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the British Dietetic Association. It includes “sensible eating patterns,” such as regular meals, never having too much or too little, and sufficient hydration. It calls for a reduction in alcoholic, caffeinated, and “fizzy” drinks; spicy, fatty, and processed foods; fresh fruit (a maximum of three per day); and fiber and other gas-producing foods, such as beans, bread, and sweeteners. It also asks people to address any perceived food intolerance, such as dairy.

In North America, the low-FODMAP diet is prescribed as first-line therapy, and the American College of Gastroenterology has given it a conditional recommendation.

FODMAPs are short-chain fermentable carbohydrates found in many fruits, vegetables, dairy products, artificial sweeteners, and wheat. They increase small intestinal water volume and colonic gas production that can induce gastrointestinal symptoms in people with visceral hypersensitivity.

People following the low-FODMAP diet start by eliminating all FODMAPs for 4-6 weeks, then gradually reintroducing them to determine which are most likely to trigger symptoms.

A gluten-free diet, inspired by what is prescribed to treat celiac disease, has gained popularity in recent years. Although researchers debate the mechanism by which this diet improves symptoms, one leading theory is a reduction in fructans that accompany gluten in foods such as bread.

A rare head-to-head comparison trial

The low-FODMAP diet has proved itself in more clinical trials than the other two approaches, but few, if any, trials have compared them head-to-head in a pragmatic randomized trial, Dr. Rej and colleagues found after reviewing the literature.

They set about filling this gap by recruiting 114 people with IBS and randomly assigning each of them to one of the diets. Ninety-nine people finished the trial, with 33 following each of the diets. People with IBS-constipation were excluded.

Participants were a mean age of 37 years. Seventy-one percent were female, and 88% were White. Their mean IBS symptom severity score was 301, with 9% rating their symptoms as mild, 47% as moderate, and 45% as severe.

The proportion who reported at least a 50% reduction in their symptoms was 58% for the gluten-free diet, 55% for the low-FODMAP diet, and 42% for the TDA. The differences in these proportions were not significant (P = .43).

The diets worked about as well regardless of whether the patients had IBS with diarrhea or IBS with mixed diarrhea and constipation.

More of the people on the low-FODMAP diet reported significant improvement in their depression and dysphoria than people on the other two diets.

Changes in anxiety, somatization, and other aspects of IBS quality of life didn’t differ significantly with diet.

Where the diets differ: cost and ease

Fewer people following the TDA rated it as expensive, difficult, or socially awkward, compared with the people following the other two diets.

More of those following the TDA and gluten-free diet found them easy to incorporate into their lives than those following the low-FODMAP diet. About two-thirds of the people in each of these groups said they would consider continuing their diets after the end of the study.

The proportion of people consuming the recommended dietary reference values for macronutrients did not change with any of the diets. However, those in the TDA group reduced their intake of potassium and iron. In the other groups, the researchers noted a reduction in thiamine and magnesium.

Because of COVID-19 restrictions, the researchers were able to collect stool samples from only half of participants. What they did collect showed no difference among the groups in dysbiosis index or functional bacterial profiles.

Baseline factors such as age, gender, IBS subtype, dysbiosis index, somatization, and mood did not predict response to the three diets.

Participants improved as much whether they received dietary instructions face-to-face or through a live virtual consultation.

Applications and limitations

At least one previous study showed that the low-FODMAP diet produced better results than the standard diets patients had been following, said Brian E. Lacy, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., who was not involved in the current study.

He agreed with the study’s conclusion that the TDA could be a good place for people with IBS to start.

“Based on their research, and the findings that patients thought the diet was less expensive, easier to follow, and easier to shop for, this is a reasonable approach,” he told this news organization. “However, if there’s no benefit with the traditional diet, then moving on to the more rigorous low-FODMAP diet makes sense to me.”

Study limitations include a short duration, lack of information about how patients can add foods back into their diet (particularly with the low-FODMAP diet), and insufficient sample size and lack of a placebo group contributing to an inability to detect all clinically significant differences among the diets, he said.

“Although this study is not definitive and doesn’t answer all key questions about which diet is best and how each performs in the long run, it does provide important information for patients and providers,” said Dr. Lacy.

The study was funded by Schaer. One of the study authors has reported receiving an educational grant from Schaer. Dr. Lacy has reported being on scientific advisory boards for Ironwood, Salix, and Allakos.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Weekend catch-up sleep may help fatty liver

People who don’t get enough sleep during the week may be able to reduce their risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by catching up on the weekends, researchers say.

“Our study revealed that people who get enough sleep have a lower risk of developing NAFLD than those who get insufficient sleep,” Sangheun Lee, MD, PhD, from Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Hepatology.

However, they cautioned that further research is needed to verify their finding.

Previous studies have associated insufficient sleep with obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, as well as liver fibrosis.

A busy weekday schedule can make it harder to get enough sleep, and some people try to compensate by sleeping longer on weekends. Studies so far have produced mixed findings on this strategy, with some showing that more sleep on the weekend reduces the risk for obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, and others showing no effect on metabolic dysregulation or energy balance.

Accessing a nation’s sleep data

To explore the relationship between sleep patterns and NAFLD, Dr. Lee and colleagues analyzed data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys collected from 2008 to 2019. They excluded people aged less than 20 years, those with hepatitis B or C infections, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, shift workers and others who “slept irregularly,” and those who consumed alcohol excessively, leaving a cohort of 101,138 participants.

The survey didn’t distinguish between sleep on weekdays and weekends until 2016, so the researchers divided their findings into two: 68,759 people surveyed from 2008 to 2015 (set 1) and 32,379 surveyed from 2016 to 2019 (set 2).

Set 1 was further divided into those who averaged more than 7 hours of sleep per day and those who slept less than that. Set 2 was divided into three groups: one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did not catch up on weekends, one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did catch up on weekends, and one that averaged more than 7 hours of sleep throughout the week.

The researchers used the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) to determine the presence of a fatty liver, calculated as 8 x (ratio of serum ALT to serum AST) + body mass index (+ 2 for female, + 2 in case of diabetes). An HSI of at least36 was considered an indicator of fatty liver.

Less sleep, more risk

Participants in set 1 slept for a mean of 6.8 hours, with 58.6% sleeping more than 7 hours a day. Those in set 2 slept a mean of 6.9 hours during weekdays, with 59.9% sleeping more than 7 hours. They also slept a mean of 7.7 hours on weekends.

In set 1, sleeping at least7 hours was associated with a 16% lower risk for NAFLD (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.89).

In set 2, sleeping at least 7 hours on weekdays was associated with a 19% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.74-0.89). Sleeping at least 7 hours on the weekend was associated with a 22% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.87). Compared with those who slept less than 7 hours throughout the week, those who slept less than 7 hours on weekdays and more than 7 hours on weekends had a 20% lower rate of NAFLD (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70-0.92).

All these associations held true for both men and women.

Why getting your Z’s may have hepatic advantages

One explanation for the link between sleep patterns and NAFLD is that dysregulation of cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, and norepinephrine are associated with both variations in sleep and NAFLD onset, Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

They also pointed out that a lack of sleep can reduce the secretion of two hormones that promote satiety: leptin and glucagonlike peptide–1. As a result, people who sleep less may eat more and gain weight, which increases the risk for NAFLD.

Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, a professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion, who was not involved in the study, noted that it was based on comparing a cross section of a population instead of following the participants over time.

“So, I think it’s an association rather than a cause and effect,” he said in an interview.

The authors don’t report a multivariate analysis to determine whether comorbidities or other characteristics of the patients could explain the association, he pointed out, noting that obesity, for example, can increase the risk for both NAFLD and sleep apnea.

Still, Dr. Singal said, the paper will influence him to mention sleep in the context of lifestyle factors that can affect fatty liver disease. “I’m going to tell my patients, and tell the community physicians to tell their patients, to follow a good sleep hygiene and make sure that they sleep at least 5-7 hours.”

Dr. Singal and the study authors all reported no relevant financial relationships. The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who don’t get enough sleep during the week may be able to reduce their risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by catching up on the weekends, researchers say.

“Our study revealed that people who get enough sleep have a lower risk of developing NAFLD than those who get insufficient sleep,” Sangheun Lee, MD, PhD, from Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Hepatology.

However, they cautioned that further research is needed to verify their finding.

Previous studies have associated insufficient sleep with obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, as well as liver fibrosis.

A busy weekday schedule can make it harder to get enough sleep, and some people try to compensate by sleeping longer on weekends. Studies so far have produced mixed findings on this strategy, with some showing that more sleep on the weekend reduces the risk for obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, and others showing no effect on metabolic dysregulation or energy balance.

Accessing a nation’s sleep data

To explore the relationship between sleep patterns and NAFLD, Dr. Lee and colleagues analyzed data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys collected from 2008 to 2019. They excluded people aged less than 20 years, those with hepatitis B or C infections, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, shift workers and others who “slept irregularly,” and those who consumed alcohol excessively, leaving a cohort of 101,138 participants.

The survey didn’t distinguish between sleep on weekdays and weekends until 2016, so the researchers divided their findings into two: 68,759 people surveyed from 2008 to 2015 (set 1) and 32,379 surveyed from 2016 to 2019 (set 2).

Set 1 was further divided into those who averaged more than 7 hours of sleep per day and those who slept less than that. Set 2 was divided into three groups: one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did not catch up on weekends, one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did catch up on weekends, and one that averaged more than 7 hours of sleep throughout the week.

The researchers used the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) to determine the presence of a fatty liver, calculated as 8 x (ratio of serum ALT to serum AST) + body mass index (+ 2 for female, + 2 in case of diabetes). An HSI of at least36 was considered an indicator of fatty liver.

Less sleep, more risk

Participants in set 1 slept for a mean of 6.8 hours, with 58.6% sleeping more than 7 hours a day. Those in set 2 slept a mean of 6.9 hours during weekdays, with 59.9% sleeping more than 7 hours. They also slept a mean of 7.7 hours on weekends.

In set 1, sleeping at least7 hours was associated with a 16% lower risk for NAFLD (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.89).

In set 2, sleeping at least 7 hours on weekdays was associated with a 19% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.74-0.89). Sleeping at least 7 hours on the weekend was associated with a 22% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.87). Compared with those who slept less than 7 hours throughout the week, those who slept less than 7 hours on weekdays and more than 7 hours on weekends had a 20% lower rate of NAFLD (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70-0.92).

All these associations held true for both men and women.

Why getting your Z’s may have hepatic advantages

One explanation for the link between sleep patterns and NAFLD is that dysregulation of cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, and norepinephrine are associated with both variations in sleep and NAFLD onset, Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

They also pointed out that a lack of sleep can reduce the secretion of two hormones that promote satiety: leptin and glucagonlike peptide–1. As a result, people who sleep less may eat more and gain weight, which increases the risk for NAFLD.

Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, a professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion, who was not involved in the study, noted that it was based on comparing a cross section of a population instead of following the participants over time.

“So, I think it’s an association rather than a cause and effect,” he said in an interview.

The authors don’t report a multivariate analysis to determine whether comorbidities or other characteristics of the patients could explain the association, he pointed out, noting that obesity, for example, can increase the risk for both NAFLD and sleep apnea.

Still, Dr. Singal said, the paper will influence him to mention sleep in the context of lifestyle factors that can affect fatty liver disease. “I’m going to tell my patients, and tell the community physicians to tell their patients, to follow a good sleep hygiene and make sure that they sleep at least 5-7 hours.”

Dr. Singal and the study authors all reported no relevant financial relationships. The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who don’t get enough sleep during the week may be able to reduce their risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by catching up on the weekends, researchers say.

“Our study revealed that people who get enough sleep have a lower risk of developing NAFLD than those who get insufficient sleep,” Sangheun Lee, MD, PhD, from Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon, South Korea, and colleagues wrote in Annals of Hepatology.

However, they cautioned that further research is needed to verify their finding.

Previous studies have associated insufficient sleep with obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, as well as liver fibrosis.

A busy weekday schedule can make it harder to get enough sleep, and some people try to compensate by sleeping longer on weekends. Studies so far have produced mixed findings on this strategy, with some showing that more sleep on the weekend reduces the risk for obesity, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, and others showing no effect on metabolic dysregulation or energy balance.

Accessing a nation’s sleep data

To explore the relationship between sleep patterns and NAFLD, Dr. Lee and colleagues analyzed data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys collected from 2008 to 2019. They excluded people aged less than 20 years, those with hepatitis B or C infections, liver cirrhosis or liver cancer, shift workers and others who “slept irregularly,” and those who consumed alcohol excessively, leaving a cohort of 101,138 participants.

The survey didn’t distinguish between sleep on weekdays and weekends until 2016, so the researchers divided their findings into two: 68,759 people surveyed from 2008 to 2015 (set 1) and 32,379 surveyed from 2016 to 2019 (set 2).

Set 1 was further divided into those who averaged more than 7 hours of sleep per day and those who slept less than that. Set 2 was divided into three groups: one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did not catch up on weekends, one that averaged less than 7 hours of sleep per day and did catch up on weekends, and one that averaged more than 7 hours of sleep throughout the week.

The researchers used the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) to determine the presence of a fatty liver, calculated as 8 x (ratio of serum ALT to serum AST) + body mass index (+ 2 for female, + 2 in case of diabetes). An HSI of at least36 was considered an indicator of fatty liver.

Less sleep, more risk

Participants in set 1 slept for a mean of 6.8 hours, with 58.6% sleeping more than 7 hours a day. Those in set 2 slept a mean of 6.9 hours during weekdays, with 59.9% sleeping more than 7 hours. They also slept a mean of 7.7 hours on weekends.

In set 1, sleeping at least7 hours was associated with a 16% lower risk for NAFLD (odds ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.89).

In set 2, sleeping at least 7 hours on weekdays was associated with a 19% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.74-0.89). Sleeping at least 7 hours on the weekend was associated with a 22% reduced risk for NAFLD (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.70-0.87). Compared with those who slept less than 7 hours throughout the week, those who slept less than 7 hours on weekdays and more than 7 hours on weekends had a 20% lower rate of NAFLD (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70-0.92).

All these associations held true for both men and women.

Why getting your Z’s may have hepatic advantages

One explanation for the link between sleep patterns and NAFLD is that dysregulation of cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, and norepinephrine are associated with both variations in sleep and NAFLD onset, Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

They also pointed out that a lack of sleep can reduce the secretion of two hormones that promote satiety: leptin and glucagonlike peptide–1. As a result, people who sleep less may eat more and gain weight, which increases the risk for NAFLD.

Ashwani K. Singal, MD, MS, a professor of medicine at the University of South Dakota, Vermillion, who was not involved in the study, noted that it was based on comparing a cross section of a population instead of following the participants over time.

“So, I think it’s an association rather than a cause and effect,” he said in an interview.

The authors don’t report a multivariate analysis to determine whether comorbidities or other characteristics of the patients could explain the association, he pointed out, noting that obesity, for example, can increase the risk for both NAFLD and sleep apnea.

Still, Dr. Singal said, the paper will influence him to mention sleep in the context of lifestyle factors that can affect fatty liver disease. “I’m going to tell my patients, and tell the community physicians to tell their patients, to follow a good sleep hygiene and make sure that they sleep at least 5-7 hours.”

Dr. Singal and the study authors all reported no relevant financial relationships. The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF HEPATOLOGY

Freiburg index accurately predicts survival in liver procedure

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

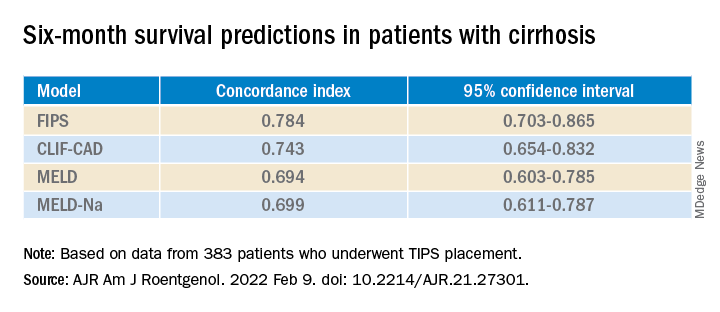

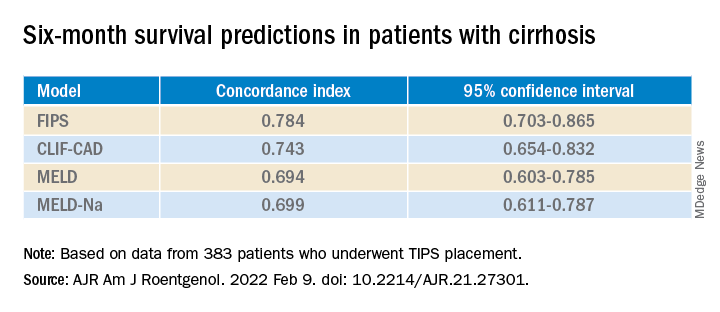

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF ROENTGENOLOGY

Anesthesia care team may be quicker for GI endoscopy

Gastrointestinal endoscopy takes less time when an anesthesiologist oversees the sedation, researchers say.

“We have increased patient access to our GI unit by making these modifications,” said Adeel Faruki, MD, a senior instructor of anesthesiology and fellow in operations at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The finding was presented at the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ ADVANCE 2022, the Anesthesiology Business Event.

Sedation for endoscopy in the United States generally follows one of two models, Dr. Faruki told this news organization: nurse-administered sedation (NAS) or monitored anesthesia care (MAC). During NAS, a GI proceduralist monitors a registered nurse who sedates patients using medications such as fentanyl, midazolam, and diphenhydramine. This was the approach at the researchers’ GI unit until July 1, 2021.

After that date, the GI unit switched to the MAC model, in which an anesthesiologist supervises a certified registered nurse anesthesiologist or an anesthesiology assistant who administers propofol. Propofol is faster acting than the drug combination the GI unit previously used and causes deeper sedation. But it can also cause respiratory or cardiovascular depression or low blood pressure, Dr. Faruki said, so most institutions require an anesthesiologist to oversee its use.

NAS versus MAC: Seeking the superior model

To see which approach was faster, Dr. Faruki and colleagues recorded times for endoscopic procedures from Aug. 1, 2021, to Oct. 31, 2021, and compared them with the data they had logged in electronic medical records from Jan. 1, 2021, to June 30, 2021. They excluded the month of July to allow for a transition period between the two approaches.

After comparing results from 4,606 patients undergoing endoscopy with NAS to 1,034 undergoing it with MAC, they observed that switching to the latter model reduced the time from sedation start to scope-in by 2-2.5 minutes.

Because recovery is faster with propofol, the patients also spent 7 minutes less in the postanesthesia care unit for upper GI endoscopies and 2 minutes less for lower GI endoscopies. Patients also told the researchers they felt less groggy.

At the same time the unit was transitioning from NAS to MAC, they also began requiring patients to sign consent forms for both the anesthesia and GI procedures in the preoperative room rather than in the procedure room. That saved about 19 minutes.

Putting all these changes together, the researchers calculated that they increased the capacity of their GI unit by 25%.

“With a pandemic raging and capacity crises continuing, it becomes very relevant to the care we can provide patients,” Dr. Faruki said. “That’s something we’re actually really proud of.”

The university is now instituting similar procedures at its other ambulatory surgical centers, he added.

How efficient is your endoscopy center?

“Other factors can also affect the efficiency of endoscopy,” said Joseph Vicari, MD, MBA, a partner at Rockford (Ill.) Gastroenterology Associates, who was not involved in this study.

For example, the unit has to have enough endoscopes and enough techs to clean them so they’re always available, he said in an interview. There have to be enough nurses and other staff to turn the rooms over efficiently. There also have to be enough pre- and postoperative beds, so that no one is waiting for either one.

Dr. Vicari recommended that GI endoscopy centers compare their times with those of benchmarks provided by professional societies and in published papers.

Having sorted out these factors, the MAC and NAS approaches both have their pros and cons, said Dr. Vicari.

“I think it’s a good idea for units that are struggling with efficiency, especially hospital-based units, to consider new ways to upload patient information and maybe have a dedicated anesthesia team to improve efficiency,” he said. “Procedure time can be reduced because you generally have a much steadier state of sedation with MAC, and then the recovery is much faster with propofol. Your patients wake up faster.”

But Rockford Gastroenterology continues to use the NAS approach in at least 90% of its endoscopies, because it is already so efficient that it doesn’t believe that MAC would make a significant difference.

“Academic centers tend to be less efficient,” he said. “Units like ours, an ambulatory endoscopy center, are different.”

NAS is also less expensive, Dr. Vicari said. “We have leveraged our lower-cost ambulatory endoscopy center by providing fentanyl and Versed [midazolam], turning it into an advantage in developing bundled contracts. Payers can significantly reduce expenses.”

The involvement of an anesthesiologist could increase the cost, Dr. Faruki acknowledged, and he said the researchers are analyzing that question. But he added that anesthesiologists can also oversee four rooms at once.

Dr. Faruki and Dr. Vicari reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gastrointestinal endoscopy takes less time when an anesthesiologist oversees the sedation, researchers say.

“We have increased patient access to our GI unit by making these modifications,” said Adeel Faruki, MD, a senior instructor of anesthesiology and fellow in operations at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The finding was presented at the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ ADVANCE 2022, the Anesthesiology Business Event.

Sedation for endoscopy in the United States generally follows one of two models, Dr. Faruki told this news organization: nurse-administered sedation (NAS) or monitored anesthesia care (MAC). During NAS, a GI proceduralist monitors a registered nurse who sedates patients using medications such as fentanyl, midazolam, and diphenhydramine. This was the approach at the researchers’ GI unit until July 1, 2021.

After that date, the GI unit switched to the MAC model, in which an anesthesiologist supervises a certified registered nurse anesthesiologist or an anesthesiology assistant who administers propofol. Propofol is faster acting than the drug combination the GI unit previously used and causes deeper sedation. But it can also cause respiratory or cardiovascular depression or low blood pressure, Dr. Faruki said, so most institutions require an anesthesiologist to oversee its use.

NAS versus MAC: Seeking the superior model

To see which approach was faster, Dr. Faruki and colleagues recorded times for endoscopic procedures from Aug. 1, 2021, to Oct. 31, 2021, and compared them with the data they had logged in electronic medical records from Jan. 1, 2021, to June 30, 2021. They excluded the month of July to allow for a transition period between the two approaches.

After comparing results from 4,606 patients undergoing endoscopy with NAS to 1,034 undergoing it with MAC, they observed that switching to the latter model reduced the time from sedation start to scope-in by 2-2.5 minutes.

Because recovery is faster with propofol, the patients also spent 7 minutes less in the postanesthesia care unit for upper GI endoscopies and 2 minutes less for lower GI endoscopies. Patients also told the researchers they felt less groggy.

At the same time the unit was transitioning from NAS to MAC, they also began requiring patients to sign consent forms for both the anesthesia and GI procedures in the preoperative room rather than in the procedure room. That saved about 19 minutes.

Putting all these changes together, the researchers calculated that they increased the capacity of their GI unit by 25%.

“With a pandemic raging and capacity crises continuing, it becomes very relevant to the care we can provide patients,” Dr. Faruki said. “That’s something we’re actually really proud of.”

The university is now instituting similar procedures at its other ambulatory surgical centers, he added.

How efficient is your endoscopy center?

“Other factors can also affect the efficiency of endoscopy,” said Joseph Vicari, MD, MBA, a partner at Rockford (Ill.) Gastroenterology Associates, who was not involved in this study.

For example, the unit has to have enough endoscopes and enough techs to clean them so they’re always available, he said in an interview. There have to be enough nurses and other staff to turn the rooms over efficiently. There also have to be enough pre- and postoperative beds, so that no one is waiting for either one.

Dr. Vicari recommended that GI endoscopy centers compare their times with those of benchmarks provided by professional societies and in published papers.

Having sorted out these factors, the MAC and NAS approaches both have their pros and cons, said Dr. Vicari.

“I think it’s a good idea for units that are struggling with efficiency, especially hospital-based units, to consider new ways to upload patient information and maybe have a dedicated anesthesia team to improve efficiency,” he said. “Procedure time can be reduced because you generally have a much steadier state of sedation with MAC, and then the recovery is much faster with propofol. Your patients wake up faster.”

But Rockford Gastroenterology continues to use the NAS approach in at least 90% of its endoscopies, because it is already so efficient that it doesn’t believe that MAC would make a significant difference.

“Academic centers tend to be less efficient,” he said. “Units like ours, an ambulatory endoscopy center, are different.”

NAS is also less expensive, Dr. Vicari said. “We have leveraged our lower-cost ambulatory endoscopy center by providing fentanyl and Versed [midazolam], turning it into an advantage in developing bundled contracts. Payers can significantly reduce expenses.”

The involvement of an anesthesiologist could increase the cost, Dr. Faruki acknowledged, and he said the researchers are analyzing that question. But he added that anesthesiologists can also oversee four rooms at once.

Dr. Faruki and Dr. Vicari reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gastrointestinal endoscopy takes less time when an anesthesiologist oversees the sedation, researchers say.

“We have increased patient access to our GI unit by making these modifications,” said Adeel Faruki, MD, a senior instructor of anesthesiology and fellow in operations at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

The finding was presented at the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ ADVANCE 2022, the Anesthesiology Business Event.

Sedation for endoscopy in the United States generally follows one of two models, Dr. Faruki told this news organization: nurse-administered sedation (NAS) or monitored anesthesia care (MAC). During NAS, a GI proceduralist monitors a registered nurse who sedates patients using medications such as fentanyl, midazolam, and diphenhydramine. This was the approach at the researchers’ GI unit until July 1, 2021.

After that date, the GI unit switched to the MAC model, in which an anesthesiologist supervises a certified registered nurse anesthesiologist or an anesthesiology assistant who administers propofol. Propofol is faster acting than the drug combination the GI unit previously used and causes deeper sedation. But it can also cause respiratory or cardiovascular depression or low blood pressure, Dr. Faruki said, so most institutions require an anesthesiologist to oversee its use.

NAS versus MAC: Seeking the superior model

To see which approach was faster, Dr. Faruki and colleagues recorded times for endoscopic procedures from Aug. 1, 2021, to Oct. 31, 2021, and compared them with the data they had logged in electronic medical records from Jan. 1, 2021, to June 30, 2021. They excluded the month of July to allow for a transition period between the two approaches.

After comparing results from 4,606 patients undergoing endoscopy with NAS to 1,034 undergoing it with MAC, they observed that switching to the latter model reduced the time from sedation start to scope-in by 2-2.5 minutes.

Because recovery is faster with propofol, the patients also spent 7 minutes less in the postanesthesia care unit for upper GI endoscopies and 2 minutes less for lower GI endoscopies. Patients also told the researchers they felt less groggy.

At the same time the unit was transitioning from NAS to MAC, they also began requiring patients to sign consent forms for both the anesthesia and GI procedures in the preoperative room rather than in the procedure room. That saved about 19 minutes.

Putting all these changes together, the researchers calculated that they increased the capacity of their GI unit by 25%.

“With a pandemic raging and capacity crises continuing, it becomes very relevant to the care we can provide patients,” Dr. Faruki said. “That’s something we’re actually really proud of.”

The university is now instituting similar procedures at its other ambulatory surgical centers, he added.

How efficient is your endoscopy center?

“Other factors can also affect the efficiency of endoscopy,” said Joseph Vicari, MD, MBA, a partner at Rockford (Ill.) Gastroenterology Associates, who was not involved in this study.

For example, the unit has to have enough endoscopes and enough techs to clean them so they’re always available, he said in an interview. There have to be enough nurses and other staff to turn the rooms over efficiently. There also have to be enough pre- and postoperative beds, so that no one is waiting for either one.

Dr. Vicari recommended that GI endoscopy centers compare their times with those of benchmarks provided by professional societies and in published papers.

Having sorted out these factors, the MAC and NAS approaches both have their pros and cons, said Dr. Vicari.

“I think it’s a good idea for units that are struggling with efficiency, especially hospital-based units, to consider new ways to upload patient information and maybe have a dedicated anesthesia team to improve efficiency,” he said. “Procedure time can be reduced because you generally have a much steadier state of sedation with MAC, and then the recovery is much faster with propofol. Your patients wake up faster.”

But Rockford Gastroenterology continues to use the NAS approach in at least 90% of its endoscopies, because it is already so efficient that it doesn’t believe that MAC would make a significant difference.

“Academic centers tend to be less efficient,” he said. “Units like ours, an ambulatory endoscopy center, are different.”

NAS is also less expensive, Dr. Vicari said. “We have leveraged our lower-cost ambulatory endoscopy center by providing fentanyl and Versed [midazolam], turning it into an advantage in developing bundled contracts. Payers can significantly reduce expenses.”

The involvement of an anesthesiologist could increase the cost, Dr. Faruki acknowledged, and he said the researchers are analyzing that question. But he added that anesthesiologists can also oversee four rooms at once.

Dr. Faruki and Dr. Vicari reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ADVANCE 2022

Endoscopic mucosal resection valuable for cancer diagnosis

said a physician presenting at the 2022 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

Vani Konda, MD, a gastroenterologist with Baylor Scott and White Center for Esophageal Diseases, Dallas, participated in an educational session on approaches for treating localized gastroesophageal cancer. In her presentation, she addressed the advantages and disadvantages of EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for esophageal neoplasia for both diagnosis and treatment.

Esophageal neoplasia therapy includes tissue-acquiring (lesion removal and histopathologic samples) and non–tissue-acquiring therapies (which include radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy and hybrid-argon plasma coagulation.

The optimal therapy may vary with the esophageal cancer, and the cancer may vary with geography. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma is predominant, while in Western countries, esophageal adenocarcinoma is most prevalent. The incidence and mortality of esophageal adenocarcinoma has been rising for several decades, Dr. Konda said.

Considering risk factors

Barrett’s esophagus is a known risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. It can be seen endoscopically as salmon-colored lining, and histologically as specialized intestinal metaplasia.

A lesion extending beyond the basement membrane into the lamina propria is an intramucosal carcinoma, or T1a lesion. A lesion extending beyond the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa is a submucosal carcinoma, or T1b tumor, Dr. Konda said.

“The difference between T1a and T1b is important in the selection of treatment approaches due to the risk of [lymph node] metastasis,” she said. She equated a T1a lesion with a 2% or smaller risk of lymph node metastasis, and a T1b tumor with a 20% risk.*

Endoscopic therapy is more reasonable for a T1a lesion, especially since the alternative, esophagectomy, may have a mortality rate of 2% or higher, she said, while for T1b tumors, surgical or systemic treatments are warranted.

A diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia by biopsy is associated with a 40% risk of prevalent cancer, mostly intramucosal carcinoma. On the other hand, submucosal carcinoma is rare in the absence of endoscopically visible lesions. “This risk of prevalent cancer, especially in visible lesions, is the reason that we should address all visible lesions with endoscopic resection, especially in the setting of dysplasia,” Dr. Konda said.

EMR is more accurate than biopsies; diagnoses change up to half the time when EMR is done after a preresection biopsy, and there’s a higher interobserver agreement among pathologists with EMR, she said.

The goal of therapy in Barrett’s esophagus is total Barrett’s eradication to treat not only the known neoplasia, but also the rest of the at-risk epithelium.

Piecemeal EMR for the entire Barrett’s epithelium can bring about a 96% or greater neoplasia eradication rate. But the stricture rate may reach 37%, and bleeding and perforation are also common.

Combining endoscopic mucosal resection for visible lesions with ablation for the rest of the at-risk lining can achieve an eradication rate of 93% with a more favorable complication profile.

Weighing the benefits of ESD

In contrast to EMR, ESD has been practiced more frequently in Asia. It provides an en bloc specimen.

A 2014 systematic review of 380 EMR procedures and 333 ESD procedures for Barret’s associated neoplasia indicated that ESD takes longer. The recurrence rate was 0.7% for ESD versus 2.6% for EMR, but this difference fell just short of statistical significance (P = .06). Bleeding and perforation rates were similar, but stricture rates reached 22.3% with wide-field EMR, 3.4% with ESD and 0.7% with focal EMR.

In a 2016 head-to-head trial, researchers assigned 20 patients each to EMR or ESD. They found the procedure longer, but the en bloc resection was higher in ESD. Complete remission of the neoplasia was not statistically different between the two groups, with 15 of 16 patients achieving this goal with ESD and 16 of 17 with EMR. All the patients had complete remission after one retreatment of residual neoplasia. There were two severe adverse events in the ESD group, and none in the EMR group.

Weighing the pros and cons, Dr. Konda concluded that EMR is technically easier and adequate in most cases of Barrett’s esophagus, while ESD may be preferred in select cases with concern for submucosal carcinoma or nonlifting lesions.

She advocated taking patient characteristics, disease characteristics, and available expertise into account.

Dr. Konda reported financial relationships with Ambu, Cernostics, Exact Sciences, Medtronic, and Lucid Sciences. The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

*Correction, 1/28/22: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized lymph node metastasis.

said a physician presenting at the 2022 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

Vani Konda, MD, a gastroenterologist with Baylor Scott and White Center for Esophageal Diseases, Dallas, participated in an educational session on approaches for treating localized gastroesophageal cancer. In her presentation, she addressed the advantages and disadvantages of EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for esophageal neoplasia for both diagnosis and treatment.

Esophageal neoplasia therapy includes tissue-acquiring (lesion removal and histopathologic samples) and non–tissue-acquiring therapies (which include radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy and hybrid-argon plasma coagulation.

The optimal therapy may vary with the esophageal cancer, and the cancer may vary with geography. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma is predominant, while in Western countries, esophageal adenocarcinoma is most prevalent. The incidence and mortality of esophageal adenocarcinoma has been rising for several decades, Dr. Konda said.

Considering risk factors

Barrett’s esophagus is a known risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. It can be seen endoscopically as salmon-colored lining, and histologically as specialized intestinal metaplasia.

A lesion extending beyond the basement membrane into the lamina propria is an intramucosal carcinoma, or T1a lesion. A lesion extending beyond the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa is a submucosal carcinoma, or T1b tumor, Dr. Konda said.

“The difference between T1a and T1b is important in the selection of treatment approaches due to the risk of [lymph node] metastasis,” she said. She equated a T1a lesion with a 2% or smaller risk of lymph node metastasis, and a T1b tumor with a 20% risk.*

Endoscopic therapy is more reasonable for a T1a lesion, especially since the alternative, esophagectomy, may have a mortality rate of 2% or higher, she said, while for T1b tumors, surgical or systemic treatments are warranted.

A diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia by biopsy is associated with a 40% risk of prevalent cancer, mostly intramucosal carcinoma. On the other hand, submucosal carcinoma is rare in the absence of endoscopically visible lesions. “This risk of prevalent cancer, especially in visible lesions, is the reason that we should address all visible lesions with endoscopic resection, especially in the setting of dysplasia,” Dr. Konda said.

EMR is more accurate than biopsies; diagnoses change up to half the time when EMR is done after a preresection biopsy, and there’s a higher interobserver agreement among pathologists with EMR, she said.

The goal of therapy in Barrett’s esophagus is total Barrett’s eradication to treat not only the known neoplasia, but also the rest of the at-risk epithelium.

Piecemeal EMR for the entire Barrett’s epithelium can bring about a 96% or greater neoplasia eradication rate. But the stricture rate may reach 37%, and bleeding and perforation are also common.

Combining endoscopic mucosal resection for visible lesions with ablation for the rest of the at-risk lining can achieve an eradication rate of 93% with a more favorable complication profile.

Weighing the benefits of ESD

In contrast to EMR, ESD has been practiced more frequently in Asia. It provides an en bloc specimen.

A 2014 systematic review of 380 EMR procedures and 333 ESD procedures for Barret’s associated neoplasia indicated that ESD takes longer. The recurrence rate was 0.7% for ESD versus 2.6% for EMR, but this difference fell just short of statistical significance (P = .06). Bleeding and perforation rates were similar, but stricture rates reached 22.3% with wide-field EMR, 3.4% with ESD and 0.7% with focal EMR.

In a 2016 head-to-head trial, researchers assigned 20 patients each to EMR or ESD. They found the procedure longer, but the en bloc resection was higher in ESD. Complete remission of the neoplasia was not statistically different between the two groups, with 15 of 16 patients achieving this goal with ESD and 16 of 17 with EMR. All the patients had complete remission after one retreatment of residual neoplasia. There were two severe adverse events in the ESD group, and none in the EMR group.

Weighing the pros and cons, Dr. Konda concluded that EMR is technically easier and adequate in most cases of Barrett’s esophagus, while ESD may be preferred in select cases with concern for submucosal carcinoma or nonlifting lesions.

She advocated taking patient characteristics, disease characteristics, and available expertise into account.

Dr. Konda reported financial relationships with Ambu, Cernostics, Exact Sciences, Medtronic, and Lucid Sciences. The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

*Correction, 1/28/22: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized lymph node metastasis.

said a physician presenting at the 2022 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

Vani Konda, MD, a gastroenterologist with Baylor Scott and White Center for Esophageal Diseases, Dallas, participated in an educational session on approaches for treating localized gastroesophageal cancer. In her presentation, she addressed the advantages and disadvantages of EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for esophageal neoplasia for both diagnosis and treatment.

Esophageal neoplasia therapy includes tissue-acquiring (lesion removal and histopathologic samples) and non–tissue-acquiring therapies (which include radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy and hybrid-argon plasma coagulation.

The optimal therapy may vary with the esophageal cancer, and the cancer may vary with geography. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma is predominant, while in Western countries, esophageal adenocarcinoma is most prevalent. The incidence and mortality of esophageal adenocarcinoma has been rising for several decades, Dr. Konda said.

Considering risk factors

Barrett’s esophagus is a known risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. It can be seen endoscopically as salmon-colored lining, and histologically as specialized intestinal metaplasia.

A lesion extending beyond the basement membrane into the lamina propria is an intramucosal carcinoma, or T1a lesion. A lesion extending beyond the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa is a submucosal carcinoma, or T1b tumor, Dr. Konda said.

“The difference between T1a and T1b is important in the selection of treatment approaches due to the risk of [lymph node] metastasis,” she said. She equated a T1a lesion with a 2% or smaller risk of lymph node metastasis, and a T1b tumor with a 20% risk.*

Endoscopic therapy is more reasonable for a T1a lesion, especially since the alternative, esophagectomy, may have a mortality rate of 2% or higher, she said, while for T1b tumors, surgical or systemic treatments are warranted.

A diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia by biopsy is associated with a 40% risk of prevalent cancer, mostly intramucosal carcinoma. On the other hand, submucosal carcinoma is rare in the absence of endoscopically visible lesions. “This risk of prevalent cancer, especially in visible lesions, is the reason that we should address all visible lesions with endoscopic resection, especially in the setting of dysplasia,” Dr. Konda said.

EMR is more accurate than biopsies; diagnoses change up to half the time when EMR is done after a preresection biopsy, and there’s a higher interobserver agreement among pathologists with EMR, she said.

The goal of therapy in Barrett’s esophagus is total Barrett’s eradication to treat not only the known neoplasia, but also the rest of the at-risk epithelium.

Piecemeal EMR for the entire Barrett’s epithelium can bring about a 96% or greater neoplasia eradication rate. But the stricture rate may reach 37%, and bleeding and perforation are also common.

Combining endoscopic mucosal resection for visible lesions with ablation for the rest of the at-risk lining can achieve an eradication rate of 93% with a more favorable complication profile.

Weighing the benefits of ESD

In contrast to EMR, ESD has been practiced more frequently in Asia. It provides an en bloc specimen.

A 2014 systematic review of 380 EMR procedures and 333 ESD procedures for Barret’s associated neoplasia indicated that ESD takes longer. The recurrence rate was 0.7% for ESD versus 2.6% for EMR, but this difference fell just short of statistical significance (P = .06). Bleeding and perforation rates were similar, but stricture rates reached 22.3% with wide-field EMR, 3.4% with ESD and 0.7% with focal EMR.