User login

Direct Anterior Versus Posterior Simultaneous Bilateral Total Hip Arthroplasties: No Major Differences at 90 Days

End-stage osteoarthritis of the hip is a debilitating disease that is reliably treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA).1 Up to 35% of patients who undergo THA eventually require contralateral THA.2,3 In patients who present with advanced bilateral disease and undergo unilateral THA, the risk of ultimately requiring a contralateral procedure is as high as 97%.3-6 In patients with bilateral hip disease, function is not fully optimized until both hips have been replaced, particularly in the setting of fixed flexion contractures.7-9 Naturally, there has been some interest in simultaneous bilateral THAs for select patients.

The potential benefits of bilateral THAs over staged procedures include faster overall rehabilitation, exposure to a single anesthetic, reduced hospital length of stay (LOS), and cost savings.10-12 However, opinion on recommending bilateral THAs is mixed. Although bilateral procedures historically have been fraught with perioperative complications,13,14 advances in surgical and anesthetic techniques have led to improved outcomes.15 Whether surgical approach is a factor in these outcomes is unclear.

The popularity of the direct anterior (DA) approach for THA has increased in recent years.16 Although the relative advantages of various approaches remain in debate, one potential benefit of the DA approach is supine positioning, which allows simultaneous bilateral THAs to be performed without the need for repositioning before proceeding with the contralateral side. However, simultaneous bilateral THAs performed through the DA approach and those performed through other surgical approaches are lacking in comparative outcomes data.17In this study, we evaluated operative times, transfusion requirements, hospital discharge data, and 90-day complication rates in patients who had simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach.

Methods

Study Design

This single-center study was conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. After obtaining approval from our Institutional Review Board, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis. We used our institution’s total joint registry to identify all patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach. The first bilateral THAs to use the DA approach at our institution were performed in 2012. To ensure that the DA and posterior groups’ perioperative management would be similar, we included only cases performed between 2012 and 2014.

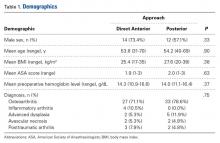

There were 19 patients in the DA group and 21 in the posterior group. The groups were similar in mean age (54 vs 54 years; P = .90), sex (73% vs 57% males; P = .33), body mass index (BMI; 25 vs 28 kg/m2; P = .38), preoperative hemoglobin level (14.3 vs 14.0 g/dL; P = .37), preoperative diagnosis (71.1% vs 78.6% degenerative joint disease; P = .75), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (1.9 vs 2.0; P = .63) (Table 1).

Patient Care

All cases were performed by 1 of 3 dedicated arthroplasty surgeons (Dr. Taunton, Dr. Sierra, Dr. Trousdale). Dr. Taunton exclusively uses the DA approach, and Dr. Sierra and Dr. Trousdale exclusively use the posterior approach. Patients in both groups received preoperative medical clearance and attended the same preoperative education class.

Patients in the DA group were positioned supine on an orthopedic table that allows hyperextension and adduction of the operative leg. Both hips were prepared and draped simultaneously. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first, with a sterile drape covering the contralateral hip. Between hips, fluoroscopy was moved to the other side of the operative suite, but no changes in positioning or preparation were necessary. A deep drain was placed on each side, and then was removed the morning of postoperative day 1. The same set of instruments was used on both sides.

Patients in the posterior group were positioned lateral on a regular operative table with hip rests. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first. After wound closure and dressing application, the patient was flipped to allow access to the contralateral hip and was prepared and draped again. The same instruments were used on each side. Drains were not used.

All patients received the same comprehensive multimodal pain management, which combined general and epidural anesthesia (remaining in place until postoperative day 2) and included an oral pain regimen of scheduled acetaminophen and as-needed tramadol and oxycodone. In all cases, intraoperative blood salvage and intravenous tranexamic acid (1 g at time of incision on first hip, 1 g at wound closure on second hip) were used. Preoperative autologous blood donation was not used. For deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, patients were treated with bilateral sequential compression devices while hospitalized, but chemoprophylaxis was different between groups. Patients in the DA group received prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin for 10 days, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 4 weeks. Patients in the posterior group received warfarin (goal international normalized ratio, 1.7-2.2) for 3 weeks, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 3 weeks. The decision to transfuse allogenic red blood cells was made by the treating surgeon, based on standardized hospital protocols, wherein patients are transfused for hemoglobin levels under 7.0 g/dL, or for hemoglobin levels less than 8.0 g/dL in the presence of persistent symptoms. All patients received care on an orthopedic specialty floor and were assisted by the same physical therapists. Discharge disposition was coordinated with the same group of social workers.

Two to 3 months after surgery, patients returned for routine examination and radiographs. All patients were followed up for at least 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

All outcomes were analyzed with appropriate summary statistics. Chi-square tests or logistic regression analyses (for categorical outcomes) were used to compare baseline covariates with perioperative outcomes, and 2-sample tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare outcomes measured on a continuous scale. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as appropriate. Operative time was calculated by adding time from incision to wound closure for both hips (room turnover time between hips was not included). Anesthesia time was defined as total time patients were in the operating room. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and the threshold for statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

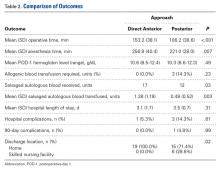

Compared with patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through the posterior approach, patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach had longer mean operative times (153 vs 106 min; P < .001) and anesthesia times (257 vs 221 min; P = .007). The 2 groups’ hospital stays were similar in length (3.1 vs 3.5 days; P = .31), but patients in the DA group were more likely to be discharged home (100.0% vs 71.4%; P = .02) (Table 2).

Patients in the DA group were more likely to have sufficient intraoperative blood salvage for autologous transfusion (89.5% vs 57.1%; OR, 6.4; 95% CI, 1.16-34.94; P = .03) (Table 3) and received more mean units of salvaged autologous blood (1.4 vs 0.5; P = .003) (Table 2). Allogenic blood was not given to any patients in the DA group, but 3 patients in the posterior group (14.3%) required allogenic blood transfusion (P = .23) (Table 2). Salvaged autologous and allogenic blood transfusion was not associated with sex, age 60 years or older, or hospital LOS of 4 days or more (Table 3). The groups’ mean hemoglobin levels, measured the morning of postoperative day 1, were similar: 10.6 g/dL (range, 8.5-12.4 g/dL) for the DA group and 10.3 g/dL (range 8.6-12.3 g/dL) for the posterior group (Table 2).

In-hospital complications were uncommon in both groups (5% vs 14%; P = .61) (Table 2). One patient in the posterior group sustained a unilateral dislocation the day of surgery, and closed reduction was required; other complications (1 ileus, 2 tachyarrhythmias) did not require intervention. Ninety-day complications were also rare; 1 patient in the posterior group developed a hematoma with wound drainage, and this was successfully managed conservatively. There were no reoperations or readmissions in either group (Table 2).

Discussion

Although bilateral procedures account for less than 1% of THAs in the United States,11 debate about their role in patients with severe bilateral hip disease continues. The potential benefits of a single episode of care must be weighed against the slightly increased risk for systemic complications.7,10-15 Recent innovations in perioperative management have been shown to minimize complications,15 but it is unclear whether surgical approach affects perioperative outcomes. Our goals in this study were to evaluate operative times, transfusion requirements, hospital discharge data, and 90-day complication rates in patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach.

Patients in our DA group had longer operative and anesthesia times. Other studies have found longer operative times for the DA approach relative to the posterior approach in unilateral THAs.18 One potential benefit of the DA approach in the setting of simultaneous bilateral THAs is the ability to prepare and drape both sides before surgery and thereby keep the interruption between hips to a minimum. In the present study, however, time saved during turnover between hips was overshadowed by the time added for each THA.

Although it was uncommon for complications to occur within 90 days after surgery in this study, many patients are needed to fully investigate these rare occurrences. Because of inherent selection bias, these risks are difficult to directly compare in patients who undergo unilateral procedures. Although small studies have failed to clarify the issue,7,19,20 a recent review of the almost 20,000 bilateral THA cases in the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample database found that bilateral (vs unilateral) THAs were associated with increased risk of local and systemic complications.11 Therefore, bilateral THAs should be reserved for select cases, with attention given to excluding patients with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease and providing appropriate preoperative counseling.

Most studies have reported a higher transfusion rate in bilateral THAs relative to staged procedures.7,21-23 Allogenic blood transfusion leads to immune suppression, coagulopathy, and other systemic effects in general, and has been specifically associated with infection in patients who undergo total joint arthroplasty.24-29 Parvizi and colleagues17 reported reduced blood loss and fewer blood transfusions in patients who had simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach, compared with the direct lateral approach. Patients in our DA group received more salvaged autologous blood, which we suppose was a function of longer operative times. However, postoperative hemoglobin levels and allogenic blood transfusion rates were statistically similar between the 2 groups. It is important to consider the increased risk of required allogenic blood transfusion associated with simultaneous bilateral THAs, but it is not fully clear if this risk is lower in THAs performed through the DA approach relative to other approaches. In our experience, the required transfusion risk is limited in DA and posterior approaches with use of contemporary perioperative blood management strategies.

Although hospital LOS is longer with simultaneous bilateral THAs than with unilateral THAs, historically it is shorter than the combined LOS of staged bilateral THAs.20 Patients in our study had a relatively short LOS after bilateral THAs, and there was no difference in LOS between groups. However, patients were more likely to be discharged home after bilateral THAs through the DA approach vs the posterior approach. Although discharge location was not affected by age, sex, ASA score, or LOS, unrecognized social factors unrelated to surgical approach likely influenced this finding.

This study should be interpreted in light of important limitations. Foremost, although data were prospectively collected, we examined them retrospectively. Thus, it is possible there may be unaccounted for differences between our DA and posterior THA groups. For example, the DA and posterior approaches were used by different surgeons with differing experience, technique, and preferences, all of which could have affected outcomes. Furthermore, our sample was relatively small (simultaneous bilateral THAs are performed relatively infrequently). Last, although anesthesia, pain management, blood conservation, and physical therapy were similar for the 2 groups, there was no standardized protocol for determining eligibility for simultaneous bilateral THAs.

In conclusion, we found that simultaneous bilateral THAs can be safely performed through either the DA approach or the posterior approach. Although the transition between hips is shorter with the DA approach, this time savings is overshadowed by the increased duration of each procedure. Transfusion rates are low in both groups, and in-hospital and 90-day complications are quite rare. Furthermore, patients can routinely be discharged home without elevating readmission rates. We will continue to perform simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach or the posterior approach, according to surgeon preference.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E373-E378. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet. 2007;370(9597):1508-1519.

2. Sayeed SA, Johnson AJ, Jaffe DE, Mont MA. Incidence of contralateral THA after index THA for osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):535-540.

3. Sayeed SA, Trousdale RT, Barnes SA, Kaufman KR, Pagnano MW. Joint arthroplasty within 10 years after primary Charnley total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(8):E141-E143.

4. Goker B, Doughan AM, Schnitzer TJ, Block JA. Quantification of progressive joint space narrowing in osteoarthritis of the hip: longitudinal analysis of the contralateral hip after total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(5):988-994.

5. Husted H, Overgaard S, Laursen JO, et al. Need for bilateral arthroplasty for coxarthrosis. 1,477 replacements in 1,199 patients followed for 0-14 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(5):421-423.

6. Ritter MA, Carr K, Herbst SA, et al. Outcome of the contralateral hip following total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(3):242-246.

7. Alfaro- Adrián J, Bayona F, Rech JA, Murray DW. One- or two-stage bilateral total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(4):439-445.

8. Wykman A, Olsson E. Walking ability after total hip replacement. A comparison of gait analysis in unilateral and bilateral cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(1):53-56.

9. Yoshii T, Jinno T, Morita S, et al. Postoperative hip motion and functional recovery after simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasty for bilateral osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sci. 2009;14(2):161-166.

10. Lorenze M, Huo MH, Zatorski LE, Keggi KJ. A comparison of the cost effectiveness of one-stage versus two-stage bilateral total hip replacement. Orthopedics. 1998;21(12):1249-1252.

11. Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):142-148.

12. Reuben JD, Meyers SJ, Cox DD, Elliott M, Watson M, Shim SD. Cost comparison between bilateral simultaneous, staged, and unilateral total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(2):172-179.

13. Bracy D, Wroblewski BM. Bilateral Charnley arthroplasty as a single procedure. A report on 400 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63(3):354-356.

14. Ritter MA, Randolph JC. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: a simultaneous procedure. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47(2):203-208.

15. Ritter MA, Stringer EA. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: a single procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;(149):185-190.

16. Matta JM, Shahrdar C, Ferguson T. Single-incision anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty on an orthopaedic table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(441):115-124.

17. Parvizi J, Rasouli MR, Jaberi M, et al. Does the surgical approach in one stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty affect blood loss? Int Orthop. 2013;37(12):2357-2362.

18. Poehling-Monaghan KL, Kamath AF, Taunton MJ, Pagnano MW. Direct anterior versus miniposterior THA with the same advanced perioperative protocols: surprising early clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):623-631.

19. Macaulay W, Salvati EA, Sculco TP, Pellicci PM. Single-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(3):217-221.

20. Romagnoli S, Zacchetti S, Perazzo P, Verde F, Banfi G, Viganò M. Simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasties do not lead to higher complication or allogeneic transfusion rates compared to unilateral procedures. Int Orthop. 2013;37(11):2125-2130.

21. Salvati EA, Hughes P, Lachiewicz P. Bilateral total hip-replacement arthroplasty in one stage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(5):640-644.

22. Parvizi J, Chaudhry S, Rasouli MR, et al. Who needs autologous blood donation in joint replacement? J Knee Surg. 2011;24(1):25-31.

23. Parvizi J, Mui A, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total joint arthroplasty: when do fatal or near-fatal complications occur? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):27-32.

24. Blair SD, Janvrin SB, McCollum CN, Greenhalgh RM. Effect of early blood transfusion on gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1986;73(10):783-785.

25. Blumberg N, Heal JM. Immunomodulation by blood transfusion: an evolving scientific and clinical challenge. Am J Med. 1996;101(3):299-308.

26. Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-417.

27. Iturbe T, Cornudella R, de Miguel R, et al. Hypercoagulability state in hip and knee surgery: influence of ABO antigenic system and allogenic transfusion. Transfus Sci. 1999;20(1):17-20.

28. Murphy P, Heal JM, Blumberg N. Infection or suspected infection after hip replacement surgery with autologous or homologous blood transfusions. Transfusion. 1991;31(3):212-217.

29. Watts CD, Pagnano MW. Minimising blood loss and transfusion in contemporary hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 suppl A):8-10.

End-stage osteoarthritis of the hip is a debilitating disease that is reliably treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA).1 Up to 35% of patients who undergo THA eventually require contralateral THA.2,3 In patients who present with advanced bilateral disease and undergo unilateral THA, the risk of ultimately requiring a contralateral procedure is as high as 97%.3-6 In patients with bilateral hip disease, function is not fully optimized until both hips have been replaced, particularly in the setting of fixed flexion contractures.7-9 Naturally, there has been some interest in simultaneous bilateral THAs for select patients.

The potential benefits of bilateral THAs over staged procedures include faster overall rehabilitation, exposure to a single anesthetic, reduced hospital length of stay (LOS), and cost savings.10-12 However, opinion on recommending bilateral THAs is mixed. Although bilateral procedures historically have been fraught with perioperative complications,13,14 advances in surgical and anesthetic techniques have led to improved outcomes.15 Whether surgical approach is a factor in these outcomes is unclear.

The popularity of the direct anterior (DA) approach for THA has increased in recent years.16 Although the relative advantages of various approaches remain in debate, one potential benefit of the DA approach is supine positioning, which allows simultaneous bilateral THAs to be performed without the need for repositioning before proceeding with the contralateral side. However, simultaneous bilateral THAs performed through the DA approach and those performed through other surgical approaches are lacking in comparative outcomes data.17In this study, we evaluated operative times, transfusion requirements, hospital discharge data, and 90-day complication rates in patients who had simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach.

Methods

Study Design

This single-center study was conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. After obtaining approval from our Institutional Review Board, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis. We used our institution’s total joint registry to identify all patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach. The first bilateral THAs to use the DA approach at our institution were performed in 2012. To ensure that the DA and posterior groups’ perioperative management would be similar, we included only cases performed between 2012 and 2014.

There were 19 patients in the DA group and 21 in the posterior group. The groups were similar in mean age (54 vs 54 years; P = .90), sex (73% vs 57% males; P = .33), body mass index (BMI; 25 vs 28 kg/m2; P = .38), preoperative hemoglobin level (14.3 vs 14.0 g/dL; P = .37), preoperative diagnosis (71.1% vs 78.6% degenerative joint disease; P = .75), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (1.9 vs 2.0; P = .63) (Table 1).

Patient Care

All cases were performed by 1 of 3 dedicated arthroplasty surgeons (Dr. Taunton, Dr. Sierra, Dr. Trousdale). Dr. Taunton exclusively uses the DA approach, and Dr. Sierra and Dr. Trousdale exclusively use the posterior approach. Patients in both groups received preoperative medical clearance and attended the same preoperative education class.

Patients in the DA group were positioned supine on an orthopedic table that allows hyperextension and adduction of the operative leg. Both hips were prepared and draped simultaneously. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first, with a sterile drape covering the contralateral hip. Between hips, fluoroscopy was moved to the other side of the operative suite, but no changes in positioning or preparation were necessary. A deep drain was placed on each side, and then was removed the morning of postoperative day 1. The same set of instruments was used on both sides.

Patients in the posterior group were positioned lateral on a regular operative table with hip rests. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first. After wound closure and dressing application, the patient was flipped to allow access to the contralateral hip and was prepared and draped again. The same instruments were used on each side. Drains were not used.

All patients received the same comprehensive multimodal pain management, which combined general and epidural anesthesia (remaining in place until postoperative day 2) and included an oral pain regimen of scheduled acetaminophen and as-needed tramadol and oxycodone. In all cases, intraoperative blood salvage and intravenous tranexamic acid (1 g at time of incision on first hip, 1 g at wound closure on second hip) were used. Preoperative autologous blood donation was not used. For deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, patients were treated with bilateral sequential compression devices while hospitalized, but chemoprophylaxis was different between groups. Patients in the DA group received prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin for 10 days, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 4 weeks. Patients in the posterior group received warfarin (goal international normalized ratio, 1.7-2.2) for 3 weeks, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 3 weeks. The decision to transfuse allogenic red blood cells was made by the treating surgeon, based on standardized hospital protocols, wherein patients are transfused for hemoglobin levels under 7.0 g/dL, or for hemoglobin levels less than 8.0 g/dL in the presence of persistent symptoms. All patients received care on an orthopedic specialty floor and were assisted by the same physical therapists. Discharge disposition was coordinated with the same group of social workers.

Two to 3 months after surgery, patients returned for routine examination and radiographs. All patients were followed up for at least 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

All outcomes were analyzed with appropriate summary statistics. Chi-square tests or logistic regression analyses (for categorical outcomes) were used to compare baseline covariates with perioperative outcomes, and 2-sample tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare outcomes measured on a continuous scale. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as appropriate. Operative time was calculated by adding time from incision to wound closure for both hips (room turnover time between hips was not included). Anesthesia time was defined as total time patients were in the operating room. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and the threshold for statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Compared with patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through the posterior approach, patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach had longer mean operative times (153 vs 106 min; P < .001) and anesthesia times (257 vs 221 min; P = .007). The 2 groups’ hospital stays were similar in length (3.1 vs 3.5 days; P = .31), but patients in the DA group were more likely to be discharged home (100.0% vs 71.4%; P = .02) (Table 2).

Patients in the DA group were more likely to have sufficient intraoperative blood salvage for autologous transfusion (89.5% vs 57.1%; OR, 6.4; 95% CI, 1.16-34.94; P = .03) (Table 3) and received more mean units of salvaged autologous blood (1.4 vs 0.5; P = .003) (Table 2). Allogenic blood was not given to any patients in the DA group, but 3 patients in the posterior group (14.3%) required allogenic blood transfusion (P = .23) (Table 2). Salvaged autologous and allogenic blood transfusion was not associated with sex, age 60 years or older, or hospital LOS of 4 days or more (Table 3). The groups’ mean hemoglobin levels, measured the morning of postoperative day 1, were similar: 10.6 g/dL (range, 8.5-12.4 g/dL) for the DA group and 10.3 g/dL (range 8.6-12.3 g/dL) for the posterior group (Table 2).

In-hospital complications were uncommon in both groups (5% vs 14%; P = .61) (Table 2). One patient in the posterior group sustained a unilateral dislocation the day of surgery, and closed reduction was required; other complications (1 ileus, 2 tachyarrhythmias) did not require intervention. Ninety-day complications were also rare; 1 patient in the posterior group developed a hematoma with wound drainage, and this was successfully managed conservatively. There were no reoperations or readmissions in either group (Table 2).

Discussion

Although bilateral procedures account for less than 1% of THAs in the United States,11 debate about their role in patients with severe bilateral hip disease continues. The potential benefits of a single episode of care must be weighed against the slightly increased risk for systemic complications.7,10-15 Recent innovations in perioperative management have been shown to minimize complications,15 but it is unclear whether surgical approach affects perioperative outcomes. Our goals in this study were to evaluate operative times, transfusion requirements, hospital discharge data, and 90-day complication rates in patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach.

Patients in our DA group had longer operative and anesthesia times. Other studies have found longer operative times for the DA approach relative to the posterior approach in unilateral THAs.18 One potential benefit of the DA approach in the setting of simultaneous bilateral THAs is the ability to prepare and drape both sides before surgery and thereby keep the interruption between hips to a minimum. In the present study, however, time saved during turnover between hips was overshadowed by the time added for each THA.

Although it was uncommon for complications to occur within 90 days after surgery in this study, many patients are needed to fully investigate these rare occurrences. Because of inherent selection bias, these risks are difficult to directly compare in patients who undergo unilateral procedures. Although small studies have failed to clarify the issue,7,19,20 a recent review of the almost 20,000 bilateral THA cases in the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample database found that bilateral (vs unilateral) THAs were associated with increased risk of local and systemic complications.11 Therefore, bilateral THAs should be reserved for select cases, with attention given to excluding patients with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease and providing appropriate preoperative counseling.

Most studies have reported a higher transfusion rate in bilateral THAs relative to staged procedures.7,21-23 Allogenic blood transfusion leads to immune suppression, coagulopathy, and other systemic effects in general, and has been specifically associated with infection in patients who undergo total joint arthroplasty.24-29 Parvizi and colleagues17 reported reduced blood loss and fewer blood transfusions in patients who had simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach, compared with the direct lateral approach. Patients in our DA group received more salvaged autologous blood, which we suppose was a function of longer operative times. However, postoperative hemoglobin levels and allogenic blood transfusion rates were statistically similar between the 2 groups. It is important to consider the increased risk of required allogenic blood transfusion associated with simultaneous bilateral THAs, but it is not fully clear if this risk is lower in THAs performed through the DA approach relative to other approaches. In our experience, the required transfusion risk is limited in DA and posterior approaches with use of contemporary perioperative blood management strategies.

Although hospital LOS is longer with simultaneous bilateral THAs than with unilateral THAs, historically it is shorter than the combined LOS of staged bilateral THAs.20 Patients in our study had a relatively short LOS after bilateral THAs, and there was no difference in LOS between groups. However, patients were more likely to be discharged home after bilateral THAs through the DA approach vs the posterior approach. Although discharge location was not affected by age, sex, ASA score, or LOS, unrecognized social factors unrelated to surgical approach likely influenced this finding.

This study should be interpreted in light of important limitations. Foremost, although data were prospectively collected, we examined them retrospectively. Thus, it is possible there may be unaccounted for differences between our DA and posterior THA groups. For example, the DA and posterior approaches were used by different surgeons with differing experience, technique, and preferences, all of which could have affected outcomes. Furthermore, our sample was relatively small (simultaneous bilateral THAs are performed relatively infrequently). Last, although anesthesia, pain management, blood conservation, and physical therapy were similar for the 2 groups, there was no standardized protocol for determining eligibility for simultaneous bilateral THAs.

In conclusion, we found that simultaneous bilateral THAs can be safely performed through either the DA approach or the posterior approach. Although the transition between hips is shorter with the DA approach, this time savings is overshadowed by the increased duration of each procedure. Transfusion rates are low in both groups, and in-hospital and 90-day complications are quite rare. Furthermore, patients can routinely be discharged home without elevating readmission rates. We will continue to perform simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach or the posterior approach, according to surgeon preference.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E373-E378. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

End-stage osteoarthritis of the hip is a debilitating disease that is reliably treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA).1 Up to 35% of patients who undergo THA eventually require contralateral THA.2,3 In patients who present with advanced bilateral disease and undergo unilateral THA, the risk of ultimately requiring a contralateral procedure is as high as 97%.3-6 In patients with bilateral hip disease, function is not fully optimized until both hips have been replaced, particularly in the setting of fixed flexion contractures.7-9 Naturally, there has been some interest in simultaneous bilateral THAs for select patients.

The potential benefits of bilateral THAs over staged procedures include faster overall rehabilitation, exposure to a single anesthetic, reduced hospital length of stay (LOS), and cost savings.10-12 However, opinion on recommending bilateral THAs is mixed. Although bilateral procedures historically have been fraught with perioperative complications,13,14 advances in surgical and anesthetic techniques have led to improved outcomes.15 Whether surgical approach is a factor in these outcomes is unclear.

The popularity of the direct anterior (DA) approach for THA has increased in recent years.16 Although the relative advantages of various approaches remain in debate, one potential benefit of the DA approach is supine positioning, which allows simultaneous bilateral THAs to be performed without the need for repositioning before proceeding with the contralateral side. However, simultaneous bilateral THAs performed through the DA approach and those performed through other surgical approaches are lacking in comparative outcomes data.17In this study, we evaluated operative times, transfusion requirements, hospital discharge data, and 90-day complication rates in patients who had simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach.

Methods

Study Design

This single-center study was conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. After obtaining approval from our Institutional Review Board, we performed a retrospective cohort analysis. We used our institution’s total joint registry to identify all patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach. The first bilateral THAs to use the DA approach at our institution were performed in 2012. To ensure that the DA and posterior groups’ perioperative management would be similar, we included only cases performed between 2012 and 2014.

There were 19 patients in the DA group and 21 in the posterior group. The groups were similar in mean age (54 vs 54 years; P = .90), sex (73% vs 57% males; P = .33), body mass index (BMI; 25 vs 28 kg/m2; P = .38), preoperative hemoglobin level (14.3 vs 14.0 g/dL; P = .37), preoperative diagnosis (71.1% vs 78.6% degenerative joint disease; P = .75), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (1.9 vs 2.0; P = .63) (Table 1).

Patient Care

All cases were performed by 1 of 3 dedicated arthroplasty surgeons (Dr. Taunton, Dr. Sierra, Dr. Trousdale). Dr. Taunton exclusively uses the DA approach, and Dr. Sierra and Dr. Trousdale exclusively use the posterior approach. Patients in both groups received preoperative medical clearance and attended the same preoperative education class.

Patients in the DA group were positioned supine on an orthopedic table that allows hyperextension and adduction of the operative leg. Both hips were prepared and draped simultaneously. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first, with a sterile drape covering the contralateral hip. Between hips, fluoroscopy was moved to the other side of the operative suite, but no changes in positioning or preparation were necessary. A deep drain was placed on each side, and then was removed the morning of postoperative day 1. The same set of instruments was used on both sides.

Patients in the posterior group were positioned lateral on a regular operative table with hip rests. The most symptomatic hip was operated on first. After wound closure and dressing application, the patient was flipped to allow access to the contralateral hip and was prepared and draped again. The same instruments were used on each side. Drains were not used.

All patients received the same comprehensive multimodal pain management, which combined general and epidural anesthesia (remaining in place until postoperative day 2) and included an oral pain regimen of scheduled acetaminophen and as-needed tramadol and oxycodone. In all cases, intraoperative blood salvage and intravenous tranexamic acid (1 g at time of incision on first hip, 1 g at wound closure on second hip) were used. Preoperative autologous blood donation was not used. For deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, patients were treated with bilateral sequential compression devices while hospitalized, but chemoprophylaxis was different between groups. Patients in the DA group received prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin for 10 days, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 4 weeks. Patients in the posterior group received warfarin (goal international normalized ratio, 1.7-2.2) for 3 weeks, followed by twice-daily aspirin (325 mg) for 3 weeks. The decision to transfuse allogenic red blood cells was made by the treating surgeon, based on standardized hospital protocols, wherein patients are transfused for hemoglobin levels under 7.0 g/dL, or for hemoglobin levels less than 8.0 g/dL in the presence of persistent symptoms. All patients received care on an orthopedic specialty floor and were assisted by the same physical therapists. Discharge disposition was coordinated with the same group of social workers.

Two to 3 months after surgery, patients returned for routine examination and radiographs. All patients were followed up for at least 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

All outcomes were analyzed with appropriate summary statistics. Chi-square tests or logistic regression analyses (for categorical outcomes) were used to compare baseline covariates with perioperative outcomes, and 2-sample tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare outcomes measured on a continuous scale. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as appropriate. Operative time was calculated by adding time from incision to wound closure for both hips (room turnover time between hips was not included). Anesthesia time was defined as total time patients were in the operating room. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and the threshold for statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Compared with patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through the posterior approach, patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach had longer mean operative times (153 vs 106 min; P < .001) and anesthesia times (257 vs 221 min; P = .007). The 2 groups’ hospital stays were similar in length (3.1 vs 3.5 days; P = .31), but patients in the DA group were more likely to be discharged home (100.0% vs 71.4%; P = .02) (Table 2).

Patients in the DA group were more likely to have sufficient intraoperative blood salvage for autologous transfusion (89.5% vs 57.1%; OR, 6.4; 95% CI, 1.16-34.94; P = .03) (Table 3) and received more mean units of salvaged autologous blood (1.4 vs 0.5; P = .003) (Table 2). Allogenic blood was not given to any patients in the DA group, but 3 patients in the posterior group (14.3%) required allogenic blood transfusion (P = .23) (Table 2). Salvaged autologous and allogenic blood transfusion was not associated with sex, age 60 years or older, or hospital LOS of 4 days or more (Table 3). The groups’ mean hemoglobin levels, measured the morning of postoperative day 1, were similar: 10.6 g/dL (range, 8.5-12.4 g/dL) for the DA group and 10.3 g/dL (range 8.6-12.3 g/dL) for the posterior group (Table 2).

In-hospital complications were uncommon in both groups (5% vs 14%; P = .61) (Table 2). One patient in the posterior group sustained a unilateral dislocation the day of surgery, and closed reduction was required; other complications (1 ileus, 2 tachyarrhythmias) did not require intervention. Ninety-day complications were also rare; 1 patient in the posterior group developed a hematoma with wound drainage, and this was successfully managed conservatively. There were no reoperations or readmissions in either group (Table 2).

Discussion

Although bilateral procedures account for less than 1% of THAs in the United States,11 debate about their role in patients with severe bilateral hip disease continues. The potential benefits of a single episode of care must be weighed against the slightly increased risk for systemic complications.7,10-15 Recent innovations in perioperative management have been shown to minimize complications,15 but it is unclear whether surgical approach affects perioperative outcomes. Our goals in this study were to evaluate operative times, transfusion requirements, hospital discharge data, and 90-day complication rates in patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral THAs through either the DA approach or the posterior approach.

Patients in our DA group had longer operative and anesthesia times. Other studies have found longer operative times for the DA approach relative to the posterior approach in unilateral THAs.18 One potential benefit of the DA approach in the setting of simultaneous bilateral THAs is the ability to prepare and drape both sides before surgery and thereby keep the interruption between hips to a minimum. In the present study, however, time saved during turnover between hips was overshadowed by the time added for each THA.

Although it was uncommon for complications to occur within 90 days after surgery in this study, many patients are needed to fully investigate these rare occurrences. Because of inherent selection bias, these risks are difficult to directly compare in patients who undergo unilateral procedures. Although small studies have failed to clarify the issue,7,19,20 a recent review of the almost 20,000 bilateral THA cases in the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample database found that bilateral (vs unilateral) THAs were associated with increased risk of local and systemic complications.11 Therefore, bilateral THAs should be reserved for select cases, with attention given to excluding patients with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease and providing appropriate preoperative counseling.

Most studies have reported a higher transfusion rate in bilateral THAs relative to staged procedures.7,21-23 Allogenic blood transfusion leads to immune suppression, coagulopathy, and other systemic effects in general, and has been specifically associated with infection in patients who undergo total joint arthroplasty.24-29 Parvizi and colleagues17 reported reduced blood loss and fewer blood transfusions in patients who had simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach, compared with the direct lateral approach. Patients in our DA group received more salvaged autologous blood, which we suppose was a function of longer operative times. However, postoperative hemoglobin levels and allogenic blood transfusion rates were statistically similar between the 2 groups. It is important to consider the increased risk of required allogenic blood transfusion associated with simultaneous bilateral THAs, but it is not fully clear if this risk is lower in THAs performed through the DA approach relative to other approaches. In our experience, the required transfusion risk is limited in DA and posterior approaches with use of contemporary perioperative blood management strategies.

Although hospital LOS is longer with simultaneous bilateral THAs than with unilateral THAs, historically it is shorter than the combined LOS of staged bilateral THAs.20 Patients in our study had a relatively short LOS after bilateral THAs, and there was no difference in LOS between groups. However, patients were more likely to be discharged home after bilateral THAs through the DA approach vs the posterior approach. Although discharge location was not affected by age, sex, ASA score, or LOS, unrecognized social factors unrelated to surgical approach likely influenced this finding.

This study should be interpreted in light of important limitations. Foremost, although data were prospectively collected, we examined them retrospectively. Thus, it is possible there may be unaccounted for differences between our DA and posterior THA groups. For example, the DA and posterior approaches were used by different surgeons with differing experience, technique, and preferences, all of which could have affected outcomes. Furthermore, our sample was relatively small (simultaneous bilateral THAs are performed relatively infrequently). Last, although anesthesia, pain management, blood conservation, and physical therapy were similar for the 2 groups, there was no standardized protocol for determining eligibility for simultaneous bilateral THAs.

In conclusion, we found that simultaneous bilateral THAs can be safely performed through either the DA approach or the posterior approach. Although the transition between hips is shorter with the DA approach, this time savings is overshadowed by the increased duration of each procedure. Transfusion rates are low in both groups, and in-hospital and 90-day complications are quite rare. Furthermore, patients can routinely be discharged home without elevating readmission rates. We will continue to perform simultaneous bilateral THAs through the DA approach or the posterior approach, according to surgeon preference.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E373-E378. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet. 2007;370(9597):1508-1519.

2. Sayeed SA, Johnson AJ, Jaffe DE, Mont MA. Incidence of contralateral THA after index THA for osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):535-540.

3. Sayeed SA, Trousdale RT, Barnes SA, Kaufman KR, Pagnano MW. Joint arthroplasty within 10 years after primary Charnley total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(8):E141-E143.

4. Goker B, Doughan AM, Schnitzer TJ, Block JA. Quantification of progressive joint space narrowing in osteoarthritis of the hip: longitudinal analysis of the contralateral hip after total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(5):988-994.

5. Husted H, Overgaard S, Laursen JO, et al. Need for bilateral arthroplasty for coxarthrosis. 1,477 replacements in 1,199 patients followed for 0-14 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(5):421-423.

6. Ritter MA, Carr K, Herbst SA, et al. Outcome of the contralateral hip following total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(3):242-246.

7. Alfaro- Adrián J, Bayona F, Rech JA, Murray DW. One- or two-stage bilateral total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(4):439-445.

8. Wykman A, Olsson E. Walking ability after total hip replacement. A comparison of gait analysis in unilateral and bilateral cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(1):53-56.

9. Yoshii T, Jinno T, Morita S, et al. Postoperative hip motion and functional recovery after simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasty for bilateral osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sci. 2009;14(2):161-166.

10. Lorenze M, Huo MH, Zatorski LE, Keggi KJ. A comparison of the cost effectiveness of one-stage versus two-stage bilateral total hip replacement. Orthopedics. 1998;21(12):1249-1252.

11. Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):142-148.

12. Reuben JD, Meyers SJ, Cox DD, Elliott M, Watson M, Shim SD. Cost comparison between bilateral simultaneous, staged, and unilateral total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(2):172-179.

13. Bracy D, Wroblewski BM. Bilateral Charnley arthroplasty as a single procedure. A report on 400 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63(3):354-356.

14. Ritter MA, Randolph JC. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: a simultaneous procedure. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47(2):203-208.

15. Ritter MA, Stringer EA. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: a single procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;(149):185-190.

16. Matta JM, Shahrdar C, Ferguson T. Single-incision anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty on an orthopaedic table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(441):115-124.

17. Parvizi J, Rasouli MR, Jaberi M, et al. Does the surgical approach in one stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty affect blood loss? Int Orthop. 2013;37(12):2357-2362.

18. Poehling-Monaghan KL, Kamath AF, Taunton MJ, Pagnano MW. Direct anterior versus miniposterior THA with the same advanced perioperative protocols: surprising early clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):623-631.

19. Macaulay W, Salvati EA, Sculco TP, Pellicci PM. Single-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(3):217-221.

20. Romagnoli S, Zacchetti S, Perazzo P, Verde F, Banfi G, Viganò M. Simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasties do not lead to higher complication or allogeneic transfusion rates compared to unilateral procedures. Int Orthop. 2013;37(11):2125-2130.

21. Salvati EA, Hughes P, Lachiewicz P. Bilateral total hip-replacement arthroplasty in one stage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(5):640-644.

22. Parvizi J, Chaudhry S, Rasouli MR, et al. Who needs autologous blood donation in joint replacement? J Knee Surg. 2011;24(1):25-31.

23. Parvizi J, Mui A, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total joint arthroplasty: when do fatal or near-fatal complications occur? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):27-32.

24. Blair SD, Janvrin SB, McCollum CN, Greenhalgh RM. Effect of early blood transfusion on gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1986;73(10):783-785.

25. Blumberg N, Heal JM. Immunomodulation by blood transfusion: an evolving scientific and clinical challenge. Am J Med. 1996;101(3):299-308.

26. Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-417.

27. Iturbe T, Cornudella R, de Miguel R, et al. Hypercoagulability state in hip and knee surgery: influence of ABO antigenic system and allogenic transfusion. Transfus Sci. 1999;20(1):17-20.

28. Murphy P, Heal JM, Blumberg N. Infection or suspected infection after hip replacement surgery with autologous or homologous blood transfusions. Transfusion. 1991;31(3):212-217.

29. Watts CD, Pagnano MW. Minimising blood loss and transfusion in contemporary hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 suppl A):8-10.

1. Learmonth ID, Young C, Rorabeck C. The operation of the century: total hip replacement. Lancet. 2007;370(9597):1508-1519.

2. Sayeed SA, Johnson AJ, Jaffe DE, Mont MA. Incidence of contralateral THA after index THA for osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):535-540.

3. Sayeed SA, Trousdale RT, Barnes SA, Kaufman KR, Pagnano MW. Joint arthroplasty within 10 years after primary Charnley total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(8):E141-E143.

4. Goker B, Doughan AM, Schnitzer TJ, Block JA. Quantification of progressive joint space narrowing in osteoarthritis of the hip: longitudinal analysis of the contralateral hip after total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(5):988-994.

5. Husted H, Overgaard S, Laursen JO, et al. Need for bilateral arthroplasty for coxarthrosis. 1,477 replacements in 1,199 patients followed for 0-14 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(5):421-423.

6. Ritter MA, Carr K, Herbst SA, et al. Outcome of the contralateral hip following total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(3):242-246.

7. Alfaro- Adrián J, Bayona F, Rech JA, Murray DW. One- or two-stage bilateral total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(4):439-445.

8. Wykman A, Olsson E. Walking ability after total hip replacement. A comparison of gait analysis in unilateral and bilateral cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(1):53-56.

9. Yoshii T, Jinno T, Morita S, et al. Postoperative hip motion and functional recovery after simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasty for bilateral osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sci. 2009;14(2):161-166.

10. Lorenze M, Huo MH, Zatorski LE, Keggi KJ. A comparison of the cost effectiveness of one-stage versus two-stage bilateral total hip replacement. Orthopedics. 1998;21(12):1249-1252.

11. Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):142-148.

12. Reuben JD, Meyers SJ, Cox DD, Elliott M, Watson M, Shim SD. Cost comparison between bilateral simultaneous, staged, and unilateral total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(2):172-179.

13. Bracy D, Wroblewski BM. Bilateral Charnley arthroplasty as a single procedure. A report on 400 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63(3):354-356.

14. Ritter MA, Randolph JC. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: a simultaneous procedure. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47(2):203-208.

15. Ritter MA, Stringer EA. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: a single procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;(149):185-190.

16. Matta JM, Shahrdar C, Ferguson T. Single-incision anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty on an orthopaedic table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(441):115-124.

17. Parvizi J, Rasouli MR, Jaberi M, et al. Does the surgical approach in one stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty affect blood loss? Int Orthop. 2013;37(12):2357-2362.

18. Poehling-Monaghan KL, Kamath AF, Taunton MJ, Pagnano MW. Direct anterior versus miniposterior THA with the same advanced perioperative protocols: surprising early clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):623-631.

19. Macaulay W, Salvati EA, Sculco TP, Pellicci PM. Single-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(3):217-221.

20. Romagnoli S, Zacchetti S, Perazzo P, Verde F, Banfi G, Viganò M. Simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasties do not lead to higher complication or allogeneic transfusion rates compared to unilateral procedures. Int Orthop. 2013;37(11):2125-2130.

21. Salvati EA, Hughes P, Lachiewicz P. Bilateral total hip-replacement arthroplasty in one stage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(5):640-644.

22. Parvizi J, Chaudhry S, Rasouli MR, et al. Who needs autologous blood donation in joint replacement? J Knee Surg. 2011;24(1):25-31.

23. Parvizi J, Mui A, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total joint arthroplasty: when do fatal or near-fatal complications occur? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):27-32.

24. Blair SD, Janvrin SB, McCollum CN, Greenhalgh RM. Effect of early blood transfusion on gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg. 1986;73(10):783-785.

25. Blumberg N, Heal JM. Immunomodulation by blood transfusion: an evolving scientific and clinical challenge. Am J Med. 1996;101(3):299-308.

26. Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-417.

27. Iturbe T, Cornudella R, de Miguel R, et al. Hypercoagulability state in hip and knee surgery: influence of ABO antigenic system and allogenic transfusion. Transfus Sci. 1999;20(1):17-20.

28. Murphy P, Heal JM, Blumberg N. Infection or suspected infection after hip replacement surgery with autologous or homologous blood transfusions. Transfusion. 1991;31(3):212-217.

29. Watts CD, Pagnano MW. Minimising blood loss and transfusion in contemporary hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 suppl A):8-10.

Ceramic Femoral Heads for All Patients? An Argument for Cost Containment in Hip Surgery

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) has revolutionized the practice of orthopedic surgery. The number of primary THAs performed in the United States alone is predicted to rise to 572,000 per year by 2030.1 Increasing demand requires a tighter focus on cost-effectiveness, particularly with regard to expensive postoperative complications. Trunnionosis and taper corrosion have recently emerged as problems in THA.2-7 No longer restricted to metal-on-metal bearings, these phenomena now affect an increasing number of metal-on-polyethylene THAs and are exacerbated by modularity.8 The emergence of these complications adds complexity to the diagnostic algorithm in patients who present with painful THAs. Furthermore, the diagnosis of either trunnionosis or taper corrosion calls for revision surgery. In response to the increase in these complications, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm for managing suspected metal toxicity issues.9 However, increases in toxicity and patient morbidity, and the added costs of toxicity surveillance and revision surgery, will place a substantial economic burden on many health systems at a time when policy makers are implementing substantial changes to health delivery in an effort to contain costs while improving patient outcomes.

Although they are more expensive than cobalt-chrome heads, ceramic femoral heads make metal toxicity a nonissue and eliminate the need for toxicity surveillance protocols. Furthermore, ceramic femoral heads are thought to have longevity advantages (this relationship needs to be confirmed in long-term studies).

In this article, we provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic femoral heads in all THA patients could represent a more cost-effective option over the long term.

Materials and Methods

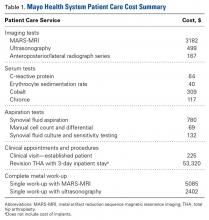

Guidelines for the diagnostic algorithm for painful THA with suspected metal toxicity were obtained from a recent orthopedic professional society consensus statement.9 The cost of this work-up was obtained from the finance department at our institution (Table 1).

We created 2 metrics to analyze the cost difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads. The first metric was “ceramic surplus,” the extra cost of a ceramic femoral head above that of a cobalt-chrome femoral head, and the second was “maximum ceramic surplus,” the ceramic surplus cutoff value for which using ceramic femoral heads in all patients becomes more cost-effective than using cobalt-chrome heads.

The cost of a metal work-up was determined for a single round of imaging tests (stratified by MRI and US), serum tests, aspiration tests, and clinic visit. These data were then combined with the cost of revision THA (Table 1) to create a series of maximum ceramic surplus models. In all these simulations, we assumed that about 7% of patients with metal-on-polyethylene THA would present with groin pain 1 to 2 years after surgery,10 and, working on this assumption, we applied a series of theoretical incidence ratios (12.5%, 25%, 50%) to both the percentage of patients who presented with a painful THA and received a metal toxicity work-up and the percentage of those who received the toxicity work-up and eventually needed revision surgery. For example, in the best-case scenario, the model assumes that 7% of THA patients present with pain and that 12.5% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (0.875% of all THAs). The best-case scenario then assumes that 12.5% of patients who receive a work-up for metal toxicity are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). By contrast, in the worst-case scenario, the model continues to assume that 7% of THA patients present with pain, but it also assumes that 50% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (3.5% of all THAs).

The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values were calculated from the best-case scenario, and the highest from the worst-case scenario. These steps were taken in keeping with the fact that a lower incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions would require the price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome heads (ceramic surplus) to be small in order for ceramic heads in all patients to be cost-effective. The inverse is true for a high incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions: A larger price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads would be tolerable to still be cost-effective.

Results

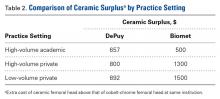

A single metal toxicity work-up cost $5085 with MARS-MRI and $2402 with US (Table 1). Revision THA with a 3-day inpatient stay cost $53,320, and that figure does not include the cost of surgical implants or perioperative medications and devices, all of which have highly variable cost structures (Table 1). Ceramic surplus was as low as $500 in a high-volume academic practice and as high as $1500 in a low-volume private practice (Table 2). Maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $511 to $2044 in the models integrating MARS-MRI and from $488 to $1950 in the models integrating US (Table 3).

Discussion

Trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity are of increasing concern in hip implants that incorporate a cobalt-chrome femoral head, regardless of the counterpart articulation surface (metal, ceramic, polyethylene).2-8 In response to the added diagnostic challenge raised by these phenomena, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm that can guide surgeons in the management of suspected corrosion or metal toxicity.9 In this protocol, toxicity surveillance in conjunction with potential revision surgery for metal-associated complications has the potential to increase patient morbidity and place a significant economic burden on many health systems. Given the recent emergence of trunnionosis, epidemiologic data on this complication are lacking.10 However, there is a substantial body of evidence showing devastating complications associated with adverse reactions to metal debris.11-17

Given the potential complications specific to cobalt-chrome femoral heads, we wanted to provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic heads in all patients has the potential to be a more cost-effective option over the long term. Ceramic femoral heads are premium implants, certainly more expensive at initial point of care. One study based on a large community registry showed premium implants (eg, ceramic femoral heads) add a surplus averaging $1000.18 In our investigation, ceramic surplus varied with practice setting, from $500 to $1500. Lower costs were discovered in high-volume practice settings, indicating that a shift to increased use of ceramic femoral heads would likely decrease ceramic surplus for most institutions.

We used a series of simulations to predict maximum ceramic surplus after manipulation of theoretical incidence ratios. The main limitation of this study was our use of 7% as the incidence of painful THA within 1- to 2-year follow-up. This point estimate was derived from a manuscript that to our knowledge provides the most realistic estimate of this complication10; with use of more complete data in upcoming studies, however, the 7% figure could certainly change. As data are also lacking on the proportion of painful THAs that receive a metal work-up and on the proportion of metal work-ups that indicate revision surgery, we modeled values of 12.5%, 25%, and 50% for each of these metrics to cover a wide range of possibilities.

It is also true the model did not incorporate scenarios to account for the law of unintended consequences, which would caution that using ceramics for all patients may bring a new set of complications. Zirconia ceramic bearings have tended to fracture, with the vast majority of fractures occurring in the liner of ceramic-on-ceramic articulations. Midterm reports and laboratory data suggest this issue has largely been solved with the advent of delta ceramics, a composite containing only a small fraction of zirconia.19,20 Nevertheless, longer term in vivo data are needed to confirm the stability, longevity, and complication profile of these materials.

A final limitation of the present study is that the cost of a single metal toxicity work-up was based on just one institution. Grossly differing cost structures in other markets could alter the economic risk–benefit analysis we have described. However, we should note that the costs of tests, procedures, and appointments at our institution were uniform across a wide variety of practice settings in multiple regions of the United States, and thus are likely similar to the costs at a majority of practices.

Although our model took some liberties by necessity, it was also quite conservative in many respects. Many patients who undergo surveillance for metal toxicity undergo serial follow-ups; for this analysis, however, we considered the cost of only a single work-up. In addition, our proposed cost of revision surgery accounts only for facility and personnel costs during a 3-day inpatient stay and does not include the costs of implants, perioperative medications and devices, follow-up care, and potentially longer hospital stays or subsequent procedures, all of which can be highly variable and add considerable cost. Had any or all of these factors been incorporated into more complex modeling, the potential economic benefits of ceramic femoral heads would have been significantly greater.

After taking all these factors into account, our model found that maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $488 to $2044, depending on theoretical incidence ratio and imaging modality (Table 3). The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values ($511 for MARS-MRI protocol, $488 for US protocol) were based on the assumption that only 12.5% of patients who present with a painful THA receive a single metal work-up (0.875% of all THAs) and that only 12.5% of those patients are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). This outcome suggests ceramic femoral heads could be more cost-effective than cobalt-chrome femoral heads under these conservative projections when considering ceramic surplus is already as low as $500 at some high-volume centers. This figure would likely decline further in parallel with widespread growth in demand. Further study on the epidemiology of trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity in metal-on-polyethylene THA is needed to evaluate the economic validity of this proposal. Nevertheless, the superior safety profile of ceramic femoral heads with regard to metal toxicity indicates that wholesale use in THAs may in fact provide the most economical option on a societal scale.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E362-E366. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

2. Cooper HJ. The local effects of metal corrosion in total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(1):9-18.

3. Cooper HJ, Della Valle CJ, Berger RA, et al. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(18):1655-1661.

4. Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck-body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865-872.

5. Jacobs JJ, Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Della Valle CJ. What do we know about taper corrosion in total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):668-669.

6. Pastides PS, Dodd M, Sarraf KM, Willis-Owen CA. Trunnionosis: a pain in the neck. World J Orthop. 2013;4(4):161-166.

7. Shulman RM, Zywiel MG, Gandhi R, Davey JR, Salonen DC. Trunnionosis: the latest culprit in adverse reactions to metal debris following hip arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(3):433-440.

8. Mihalko WM, Wimmer MA, Pacione CA, Laurent MP, Murphy RF, Rider C. How have alternative bearings and modularity affected revision rates in total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):3747-3758.

9. Kwon YM, Lombardi AV, Jacobs JJ, Fehring TK, Lewis CG, Cabanela ME. Risk stratification algorithm for management of patients with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty: consensus statement of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the Hip Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):e4.

10. Bartelt RB, Yuan BJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ. The prevalence of groin pain after metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty and total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2346-2356.

11. Bozic KJ, Lau EC, Ong KL, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. Comparative effectiveness of metal-on-metal and metal-on-polyethylene bearings in Medicare total hip arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):37-40.

12. Cuckler JM. Metal-on-metal surface replacement: a triumph of hope over reason: affirms. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e439-e441.

13. de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2287-2293.

14. Fehring TK, Odum S, Sproul R, Weathersbee J. High frequency of adverse local tissue reactions in asymptomatic patients with metal-on-metal THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):517-522.

15. Hasegawa M, Yoshida K, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A. Prevalence of adverse reactions to metal debris following metal-on-metal THA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(5):e606-e612.

16. Melvin JS, Karthikeyan T, Cope R, Fehring TK. Early failures in total hip arthroplasty—a changing paradigm. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1285-1288.

17. Wyles CC, Van Demark RE 3rd, Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT. High rate of infection after aseptic revision of failed metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):509-516.

18. Gioe TJ, Sharma A, Tatman P, Mehle S. Do “premium” joint implants add value?: Analysis of high cost joint implants in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):48-54.

19. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. Ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty have high survivorship at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):373-381.

20. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. High survivorship with a titanium-encased alumina ceramic bearing for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):611-616.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) has revolutionized the practice of orthopedic surgery. The number of primary THAs performed in the United States alone is predicted to rise to 572,000 per year by 2030.1 Increasing demand requires a tighter focus on cost-effectiveness, particularly with regard to expensive postoperative complications. Trunnionosis and taper corrosion have recently emerged as problems in THA.2-7 No longer restricted to metal-on-metal bearings, these phenomena now affect an increasing number of metal-on-polyethylene THAs and are exacerbated by modularity.8 The emergence of these complications adds complexity to the diagnostic algorithm in patients who present with painful THAs. Furthermore, the diagnosis of either trunnionosis or taper corrosion calls for revision surgery. In response to the increase in these complications, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm for managing suspected metal toxicity issues.9 However, increases in toxicity and patient morbidity, and the added costs of toxicity surveillance and revision surgery, will place a substantial economic burden on many health systems at a time when policy makers are implementing substantial changes to health delivery in an effort to contain costs while improving patient outcomes.

Although they are more expensive than cobalt-chrome heads, ceramic femoral heads make metal toxicity a nonissue and eliminate the need for toxicity surveillance protocols. Furthermore, ceramic femoral heads are thought to have longevity advantages (this relationship needs to be confirmed in long-term studies).

In this article, we provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic femoral heads in all THA patients could represent a more cost-effective option over the long term.

Materials and Methods

Guidelines for the diagnostic algorithm for painful THA with suspected metal toxicity were obtained from a recent orthopedic professional society consensus statement.9 The cost of this work-up was obtained from the finance department at our institution (Table 1).

We created 2 metrics to analyze the cost difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads. The first metric was “ceramic surplus,” the extra cost of a ceramic femoral head above that of a cobalt-chrome femoral head, and the second was “maximum ceramic surplus,” the ceramic surplus cutoff value for which using ceramic femoral heads in all patients becomes more cost-effective than using cobalt-chrome heads.

The cost of a metal work-up was determined for a single round of imaging tests (stratified by MRI and US), serum tests, aspiration tests, and clinic visit. These data were then combined with the cost of revision THA (Table 1) to create a series of maximum ceramic surplus models. In all these simulations, we assumed that about 7% of patients with metal-on-polyethylene THA would present with groin pain 1 to 2 years after surgery,10 and, working on this assumption, we applied a series of theoretical incidence ratios (12.5%, 25%, 50%) to both the percentage of patients who presented with a painful THA and received a metal toxicity work-up and the percentage of those who received the toxicity work-up and eventually needed revision surgery. For example, in the best-case scenario, the model assumes that 7% of THA patients present with pain and that 12.5% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (0.875% of all THAs). The best-case scenario then assumes that 12.5% of patients who receive a work-up for metal toxicity are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). By contrast, in the worst-case scenario, the model continues to assume that 7% of THA patients present with pain, but it also assumes that 50% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (3.5% of all THAs).

The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values were calculated from the best-case scenario, and the highest from the worst-case scenario. These steps were taken in keeping with the fact that a lower incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions would require the price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome heads (ceramic surplus) to be small in order for ceramic heads in all patients to be cost-effective. The inverse is true for a high incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions: A larger price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads would be tolerable to still be cost-effective.

Results

A single metal toxicity work-up cost $5085 with MARS-MRI and $2402 with US (Table 1). Revision THA with a 3-day inpatient stay cost $53,320, and that figure does not include the cost of surgical implants or perioperative medications and devices, all of which have highly variable cost structures (Table 1). Ceramic surplus was as low as $500 in a high-volume academic practice and as high as $1500 in a low-volume private practice (Table 2). Maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $511 to $2044 in the models integrating MARS-MRI and from $488 to $1950 in the models integrating US (Table 3).

Discussion

Trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity are of increasing concern in hip implants that incorporate a cobalt-chrome femoral head, regardless of the counterpart articulation surface (metal, ceramic, polyethylene).2-8 In response to the added diagnostic challenge raised by these phenomena, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm that can guide surgeons in the management of suspected corrosion or metal toxicity.9 In this protocol, toxicity surveillance in conjunction with potential revision surgery for metal-associated complications has the potential to increase patient morbidity and place a significant economic burden on many health systems. Given the recent emergence of trunnionosis, epidemiologic data on this complication are lacking.10 However, there is a substantial body of evidence showing devastating complications associated with adverse reactions to metal debris.11-17

Given the potential complications specific to cobalt-chrome femoral heads, we wanted to provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic heads in all patients has the potential to be a more cost-effective option over the long term. Ceramic femoral heads are premium implants, certainly more expensive at initial point of care. One study based on a large community registry showed premium implants (eg, ceramic femoral heads) add a surplus averaging $1000.18 In our investigation, ceramic surplus varied with practice setting, from $500 to $1500. Lower costs were discovered in high-volume practice settings, indicating that a shift to increased use of ceramic femoral heads would likely decrease ceramic surplus for most institutions.

We used a series of simulations to predict maximum ceramic surplus after manipulation of theoretical incidence ratios. The main limitation of this study was our use of 7% as the incidence of painful THA within 1- to 2-year follow-up. This point estimate was derived from a manuscript that to our knowledge provides the most realistic estimate of this complication10; with use of more complete data in upcoming studies, however, the 7% figure could certainly change. As data are also lacking on the proportion of painful THAs that receive a metal work-up and on the proportion of metal work-ups that indicate revision surgery, we modeled values of 12.5%, 25%, and 50% for each of these metrics to cover a wide range of possibilities.