User login

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus–like Isotopic Response to Herpes Zoster Infection

To the Editor:

Wolf isotopic response describes the development of a skin disorder at the site of another healed and unrelated skin disease. Skin disorders presenting as isotopic responses have included inflammatory, malignant, granulomatous, and infectious processes. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a rare isotopic response. We report a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that presented at the site of a recent herpes zoster infection in a liver transplant recipient.

A 74-year-old immunocompromised woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the right leg. She was being treated with maintenance valganciclovir due to cytomegalovirus viremia, as well as tacrolimus, azathioprine, and prednisone following liver transplantation due to autoimmune hepatitis for 8 months prior to presentation. Eighteen days prior to the current presentation, she was clinically diagnosed with herpes zoster. As the grouped vesicles from the herpes zoster resolved, she developed pink scaly papules in the same distribution as the original vesicular eruption.

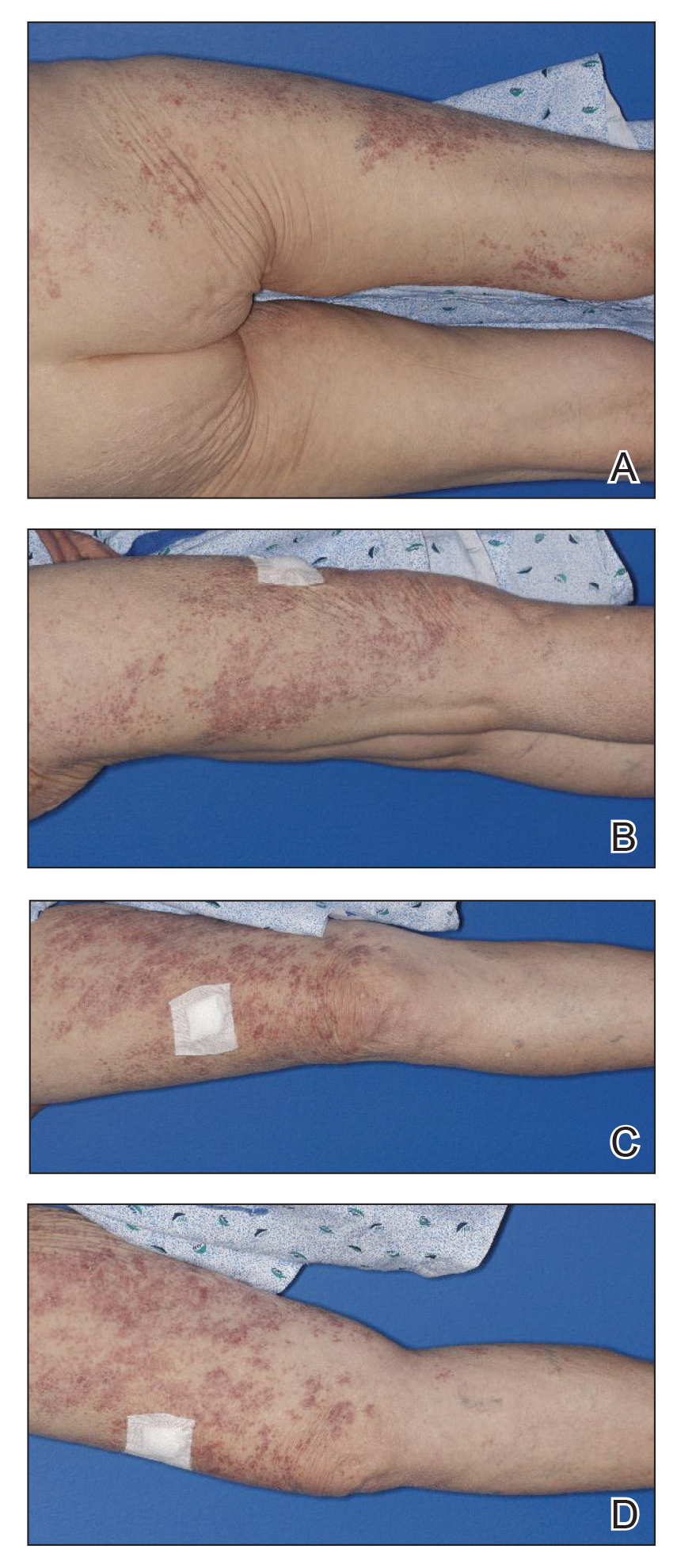

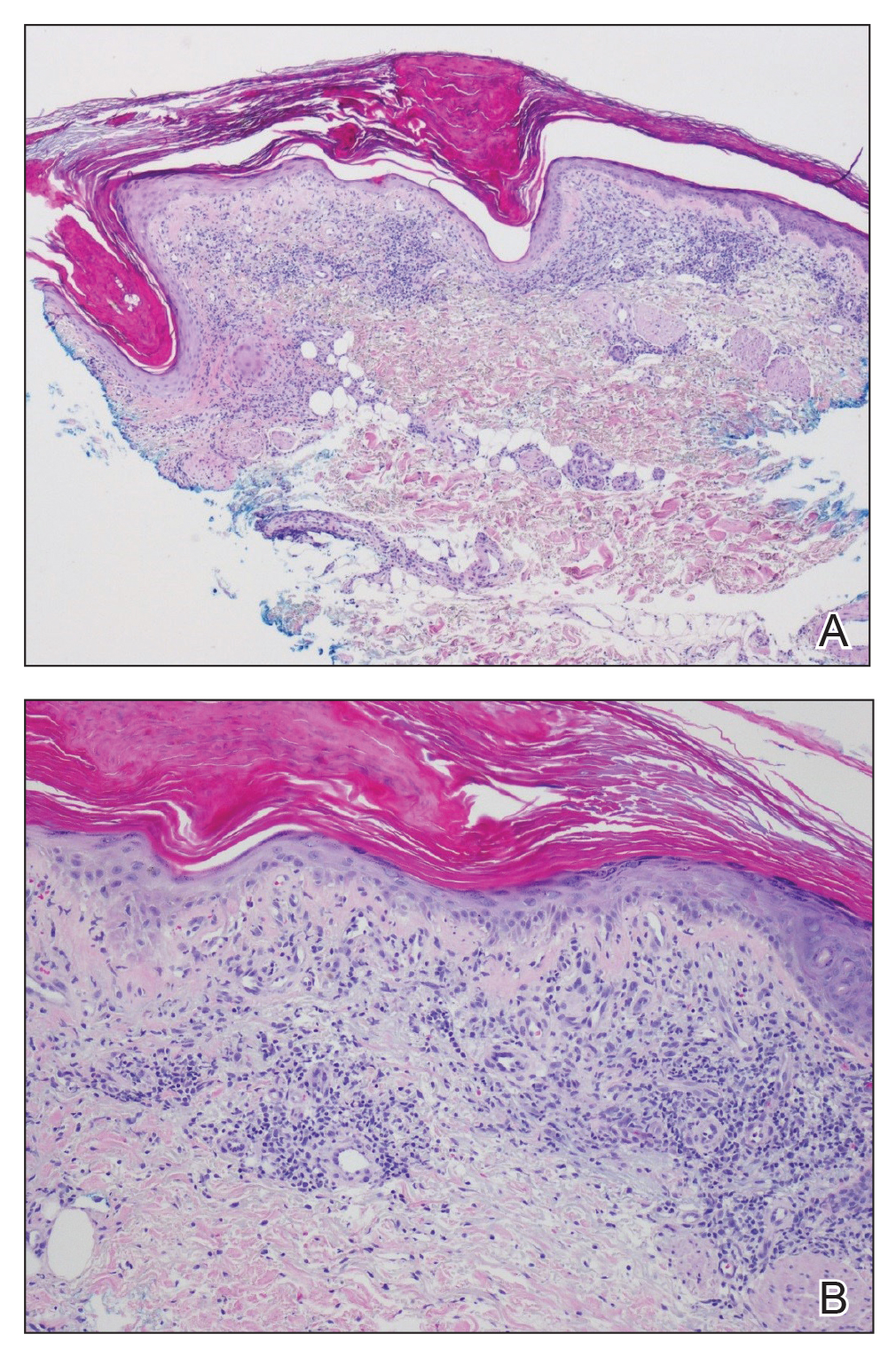

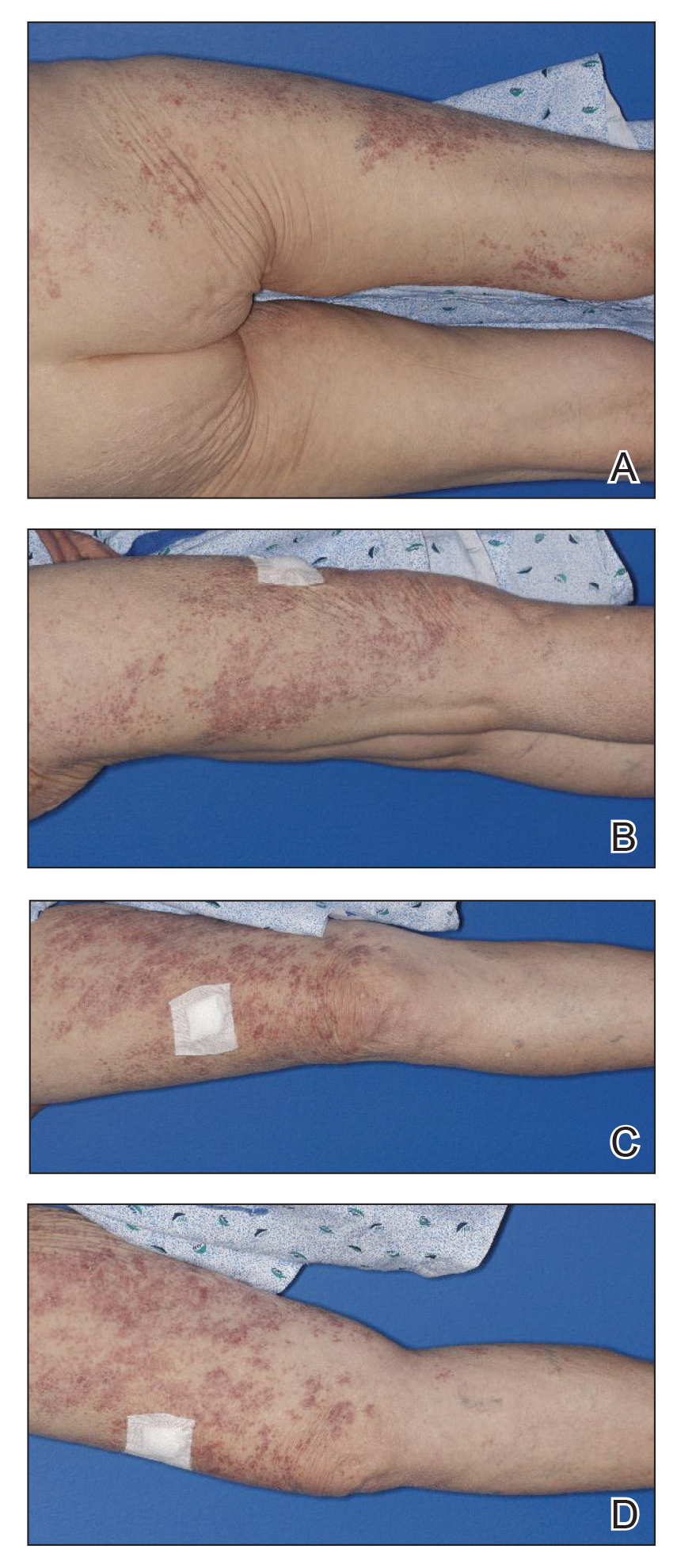

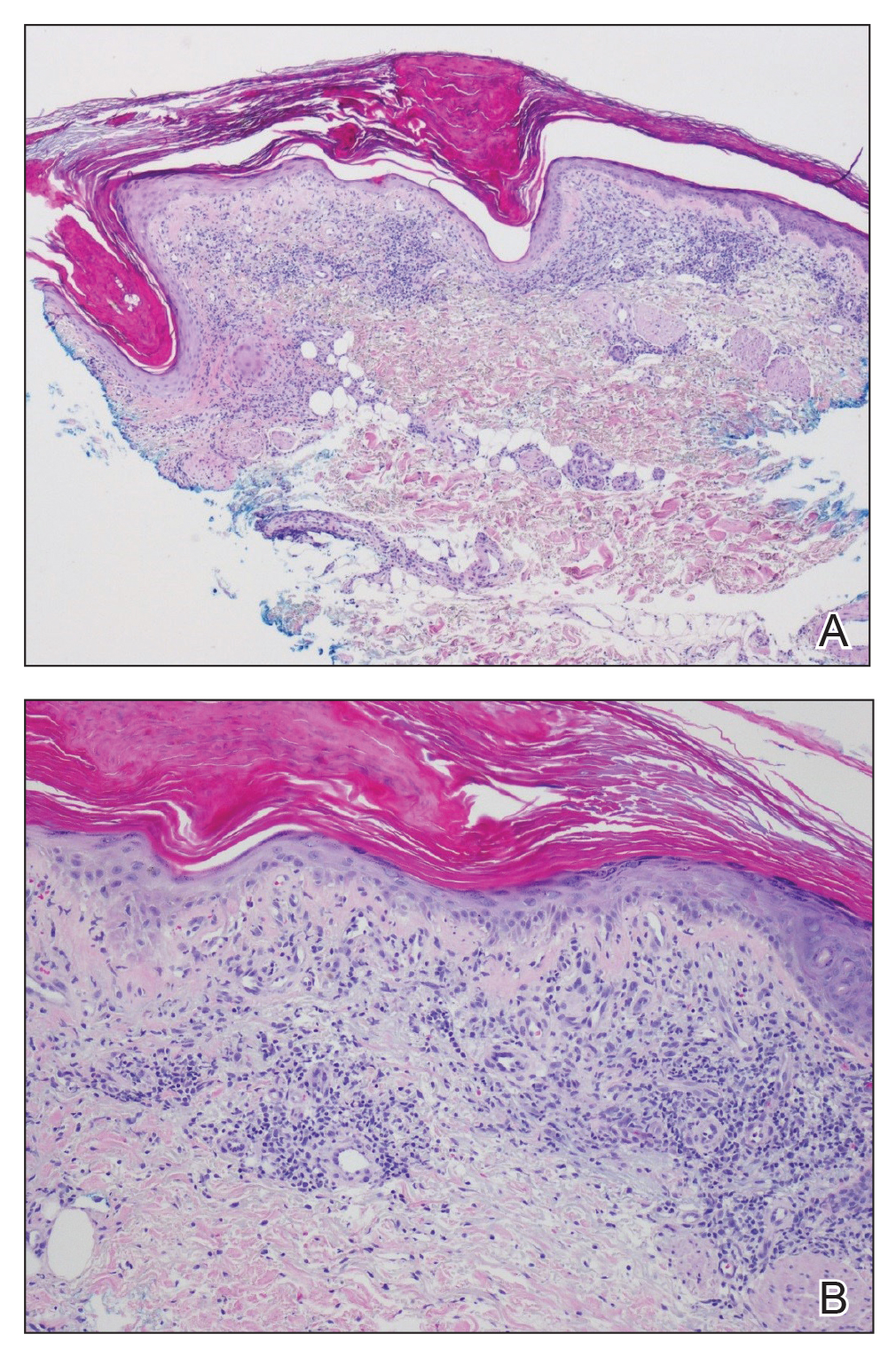

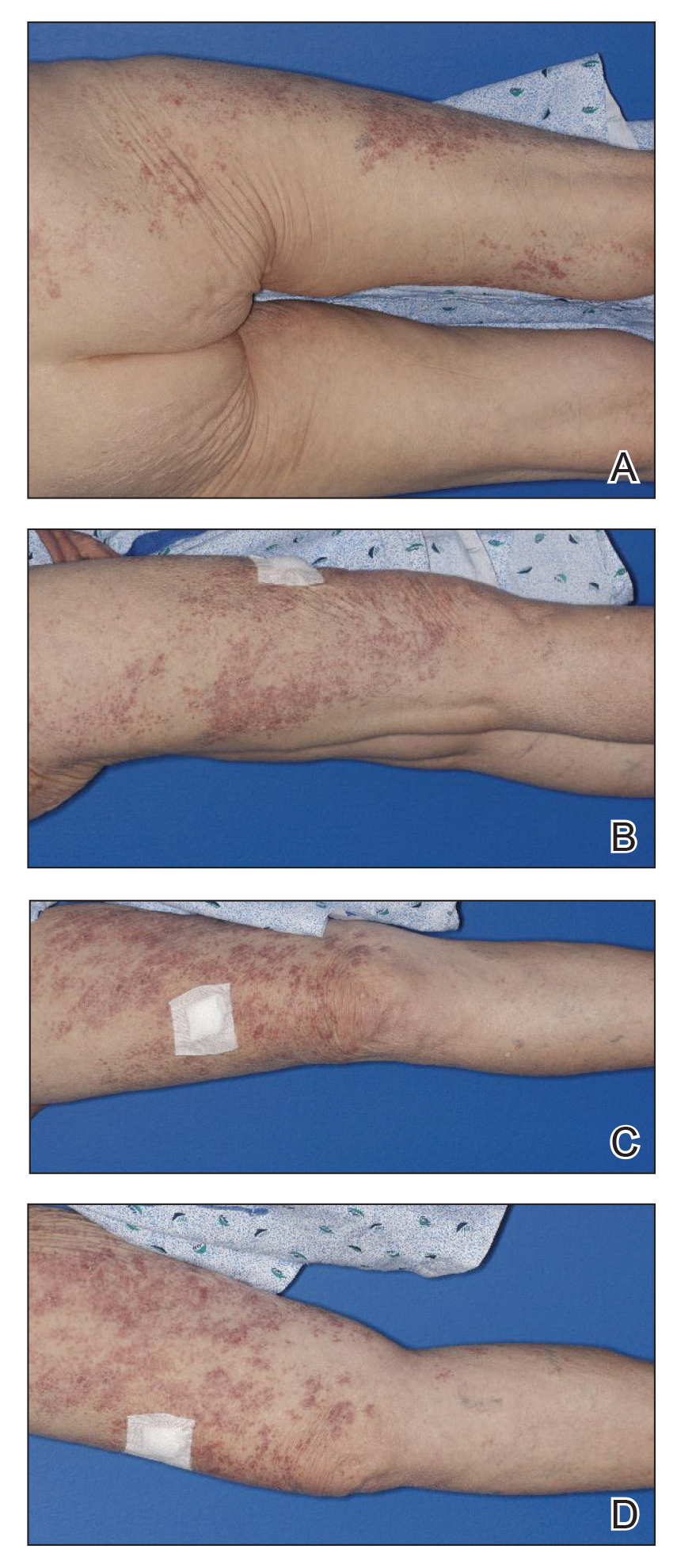

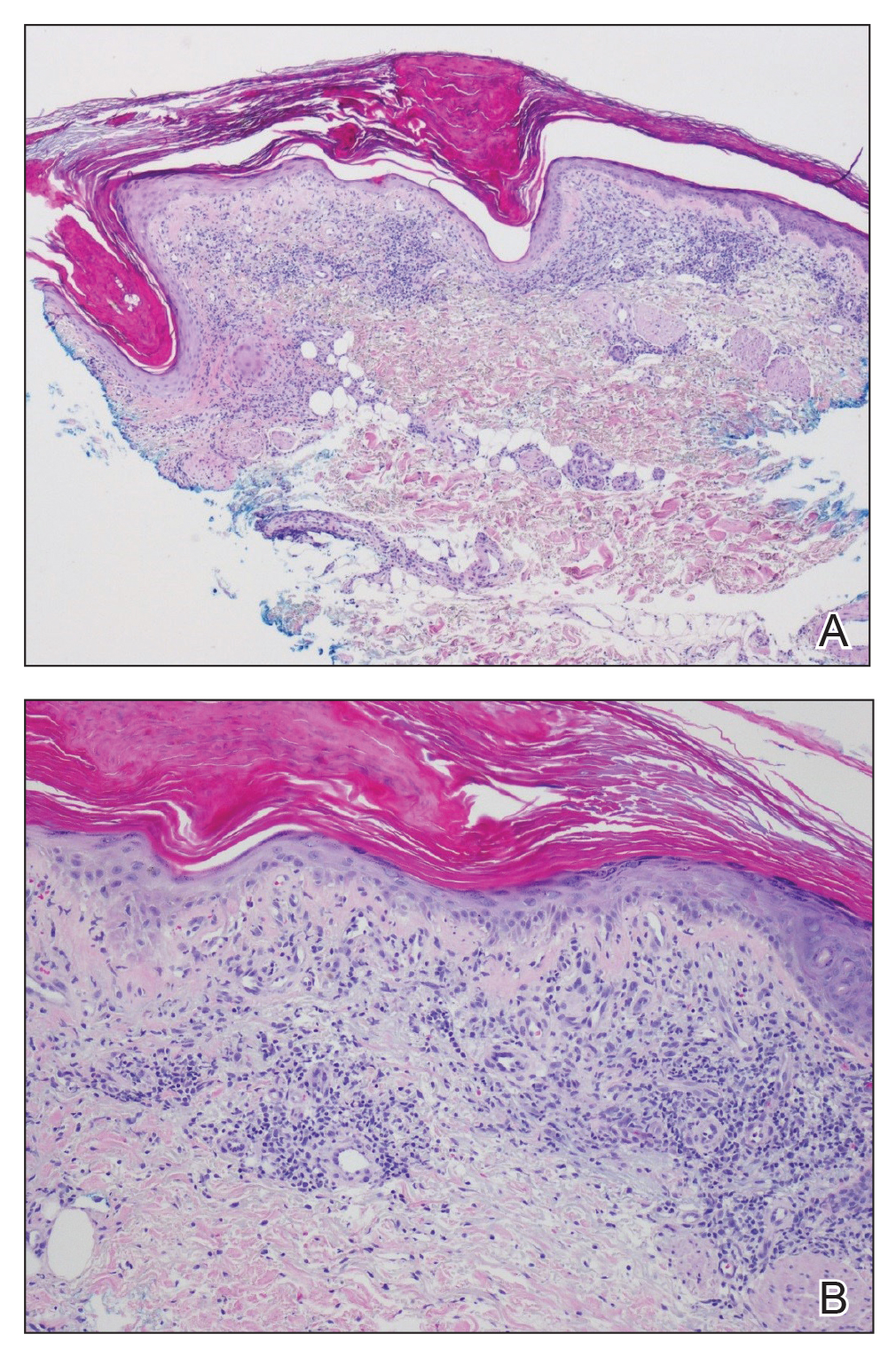

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, 2- to 3-mm, scaly papules that coalesced into small plaques with serous crusts; they originated above the supragluteal cleft and extended rightward in the L3 and L4 dermatomes to the right knee (Figure 1). A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right anterior thigh. Histologic analysis revealed interface lymphocytic inflammation with squamatization of basal keratinocytes, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging by keratin (Figure 2). There was a moderately intense perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate of mature lymphocytes with rare eosinophils within the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. There was no evidence of a viral cytopathic effect, and an immunohistochemical stain for varicella-zoster virus protein was negative. The histologic findings were suggestive of cutaneous involvement by DLE. A diagnosis of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like Wolf isotopic response was made, and the patient’s rash resolved with the use of triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied twice daily for 2 weeks. At 6-week follow-up, there were postinflammatory pigmentation changes at the sites of the prior rash and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Recent antinuclear antibody screening was negative, coupled with the patient’s lack of systemic symptoms and quick resolution of rash, indicating that additional testing for systemic lupus was not warranted.

Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder. The second disease may appear within days to years after the primary disease subsides and is clearly differentiated from the isomorphic response of the Koebner phenomenon, which describes an established skin disorder appearing at a previously uninvolved anatomic site following trauma.1 As in our case, the initial cutaneous eruption resulting in a subsequent Wolf isotopic response frequently is herpes zoster and less commonly is herpes simplex virus.2 The most common reported isotopic response is a granulomatous reaction.2 Rare reports of leukemic infiltration, lymphoma, lichen planus, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus, lichen simplex chronicus, contact dermatitis, xanthomatous changes, malignant tumors, cutaneous graft-vs-host disease, pityriasis rosea, erythema annulare centrifugum, and other infectious-based isotopic responses exist.2-6

Our patient presented with Wolf isotopic response that histologically mimicked DLE. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotopic response and lupus revealed only 3 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as an isotopic response in the English-language literature. One of those cases occurred in a patient with preexisting systemic lupus erythematosus, making a diagnosis of Koebner isomorphic phenomenon more appropriate than an isotopic response at the site of prior herpes zoster infection.7 The remaining 2 cases were clinically defined DLE lesions occurring at sites of prior infection—cutaneous leishmaniasis and herpes zoster—in patients without a prior history of cutaneous or systemic lupus erythematosus.8,9 The latter case of DLE-like isotopic response occurring after herpes zoster infection was further complicated by local injections at the zoster site for herpes-related local pain. Injection sites are reported as a distinct nidus for Wolf isotopic response.9

The pathogenesis of Wolf isotopic response is unclear. Possible explanations include local interactions between persistent viral particles at prior herpes infection sites, vascular injury, neural injury, and an altered immune response.1,5,6,10 The destruction of sensory nerve fibers by herpesviruses cause the release of neuropeptides that then modulate the local immune system and angiogenic responses.5,6 Our patient’s immunocompromised state may have further propagated a local altered immune cell infiltrate at the site of the isotopic response. Despite its unclear etiology, Wolf isotopic response should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with a dermatomal eruption at the site of a prior cutaneous infection, particularly after infection with herpes zoster. Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses with an excellent prognosis.11

We present a case of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that occurred at the site of a recent herpes zoster eruption in an immunocompromised patient without prior history of systemic or cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinical recognition of Wolf isotopic response is important for accurate histopathologic diagnosis and management. Continued investigation into the underlying pathogenesis should be performed to fully understand and better treat this process.

- Sharma RC, Sharma NL, Mahajan V, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: herpes simplex appearing on scrofuloderma scar. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:664-666.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. “Wolf’s isotopic response”: the originators speak their mind and set the record straight. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:416-418.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:110-113.

- Bardazzi F, Giacomini F, Savoia F, et al. Discoid chronic lupus erythematosus at the site of a previously healed cutaneous leishmaniasis: an example of isotopic response. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:44-46.

- Parimalam K, Kumar D, Thomas J. Discoid lupus erythematosis occurring as an isotopic response. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:50-51.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al. Viral diseases. In: James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020:362-420.

To the Editor:

Wolf isotopic response describes the development of a skin disorder at the site of another healed and unrelated skin disease. Skin disorders presenting as isotopic responses have included inflammatory, malignant, granulomatous, and infectious processes. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a rare isotopic response. We report a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that presented at the site of a recent herpes zoster infection in a liver transplant recipient.

A 74-year-old immunocompromised woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the right leg. She was being treated with maintenance valganciclovir due to cytomegalovirus viremia, as well as tacrolimus, azathioprine, and prednisone following liver transplantation due to autoimmune hepatitis for 8 months prior to presentation. Eighteen days prior to the current presentation, she was clinically diagnosed with herpes zoster. As the grouped vesicles from the herpes zoster resolved, she developed pink scaly papules in the same distribution as the original vesicular eruption.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, 2- to 3-mm, scaly papules that coalesced into small plaques with serous crusts; they originated above the supragluteal cleft and extended rightward in the L3 and L4 dermatomes to the right knee (Figure 1). A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right anterior thigh. Histologic analysis revealed interface lymphocytic inflammation with squamatization of basal keratinocytes, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging by keratin (Figure 2). There was a moderately intense perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate of mature lymphocytes with rare eosinophils within the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. There was no evidence of a viral cytopathic effect, and an immunohistochemical stain for varicella-zoster virus protein was negative. The histologic findings were suggestive of cutaneous involvement by DLE. A diagnosis of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like Wolf isotopic response was made, and the patient’s rash resolved with the use of triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied twice daily for 2 weeks. At 6-week follow-up, there were postinflammatory pigmentation changes at the sites of the prior rash and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Recent antinuclear antibody screening was negative, coupled with the patient’s lack of systemic symptoms and quick resolution of rash, indicating that additional testing for systemic lupus was not warranted.

Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder. The second disease may appear within days to years after the primary disease subsides and is clearly differentiated from the isomorphic response of the Koebner phenomenon, which describes an established skin disorder appearing at a previously uninvolved anatomic site following trauma.1 As in our case, the initial cutaneous eruption resulting in a subsequent Wolf isotopic response frequently is herpes zoster and less commonly is herpes simplex virus.2 The most common reported isotopic response is a granulomatous reaction.2 Rare reports of leukemic infiltration, lymphoma, lichen planus, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus, lichen simplex chronicus, contact dermatitis, xanthomatous changes, malignant tumors, cutaneous graft-vs-host disease, pityriasis rosea, erythema annulare centrifugum, and other infectious-based isotopic responses exist.2-6

Our patient presented with Wolf isotopic response that histologically mimicked DLE. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotopic response and lupus revealed only 3 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as an isotopic response in the English-language literature. One of those cases occurred in a patient with preexisting systemic lupus erythematosus, making a diagnosis of Koebner isomorphic phenomenon more appropriate than an isotopic response at the site of prior herpes zoster infection.7 The remaining 2 cases were clinically defined DLE lesions occurring at sites of prior infection—cutaneous leishmaniasis and herpes zoster—in patients without a prior history of cutaneous or systemic lupus erythematosus.8,9 The latter case of DLE-like isotopic response occurring after herpes zoster infection was further complicated by local injections at the zoster site for herpes-related local pain. Injection sites are reported as a distinct nidus for Wolf isotopic response.9

The pathogenesis of Wolf isotopic response is unclear. Possible explanations include local interactions between persistent viral particles at prior herpes infection sites, vascular injury, neural injury, and an altered immune response.1,5,6,10 The destruction of sensory nerve fibers by herpesviruses cause the release of neuropeptides that then modulate the local immune system and angiogenic responses.5,6 Our patient’s immunocompromised state may have further propagated a local altered immune cell infiltrate at the site of the isotopic response. Despite its unclear etiology, Wolf isotopic response should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with a dermatomal eruption at the site of a prior cutaneous infection, particularly after infection with herpes zoster. Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses with an excellent prognosis.11

We present a case of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that occurred at the site of a recent herpes zoster eruption in an immunocompromised patient without prior history of systemic or cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinical recognition of Wolf isotopic response is important for accurate histopathologic diagnosis and management. Continued investigation into the underlying pathogenesis should be performed to fully understand and better treat this process.

To the Editor:

Wolf isotopic response describes the development of a skin disorder at the site of another healed and unrelated skin disease. Skin disorders presenting as isotopic responses have included inflammatory, malignant, granulomatous, and infectious processes. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a rare isotopic response. We report a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that presented at the site of a recent herpes zoster infection in a liver transplant recipient.

A 74-year-old immunocompromised woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the right leg. She was being treated with maintenance valganciclovir due to cytomegalovirus viremia, as well as tacrolimus, azathioprine, and prednisone following liver transplantation due to autoimmune hepatitis for 8 months prior to presentation. Eighteen days prior to the current presentation, she was clinically diagnosed with herpes zoster. As the grouped vesicles from the herpes zoster resolved, she developed pink scaly papules in the same distribution as the original vesicular eruption.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, 2- to 3-mm, scaly papules that coalesced into small plaques with serous crusts; they originated above the supragluteal cleft and extended rightward in the L3 and L4 dermatomes to the right knee (Figure 1). A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the right anterior thigh. Histologic analysis revealed interface lymphocytic inflammation with squamatization of basal keratinocytes, basement membrane thickening, and follicular plugging by keratin (Figure 2). There was a moderately intense perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate of mature lymphocytes with rare eosinophils within the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. There was no evidence of a viral cytopathic effect, and an immunohistochemical stain for varicella-zoster virus protein was negative. The histologic findings were suggestive of cutaneous involvement by DLE. A diagnosis of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like Wolf isotopic response was made, and the patient’s rash resolved with the use of triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied twice daily for 2 weeks. At 6-week follow-up, there were postinflammatory pigmentation changes at the sites of the prior rash and persistent postherpetic neuralgia. Recent antinuclear antibody screening was negative, coupled with the patient’s lack of systemic symptoms and quick resolution of rash, indicating that additional testing for systemic lupus was not warranted.

Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder. The second disease may appear within days to years after the primary disease subsides and is clearly differentiated from the isomorphic response of the Koebner phenomenon, which describes an established skin disorder appearing at a previously uninvolved anatomic site following trauma.1 As in our case, the initial cutaneous eruption resulting in a subsequent Wolf isotopic response frequently is herpes zoster and less commonly is herpes simplex virus.2 The most common reported isotopic response is a granulomatous reaction.2 Rare reports of leukemic infiltration, lymphoma, lichen planus, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, discoid lupus, lichen simplex chronicus, contact dermatitis, xanthomatous changes, malignant tumors, cutaneous graft-vs-host disease, pityriasis rosea, erythema annulare centrifugum, and other infectious-based isotopic responses exist.2-6

Our patient presented with Wolf isotopic response that histologically mimicked DLE. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms isotopic response and lupus revealed only 3 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus presenting as an isotopic response in the English-language literature. One of those cases occurred in a patient with preexisting systemic lupus erythematosus, making a diagnosis of Koebner isomorphic phenomenon more appropriate than an isotopic response at the site of prior herpes zoster infection.7 The remaining 2 cases were clinically defined DLE lesions occurring at sites of prior infection—cutaneous leishmaniasis and herpes zoster—in patients without a prior history of cutaneous or systemic lupus erythematosus.8,9 The latter case of DLE-like isotopic response occurring after herpes zoster infection was further complicated by local injections at the zoster site for herpes-related local pain. Injection sites are reported as a distinct nidus for Wolf isotopic response.9

The pathogenesis of Wolf isotopic response is unclear. Possible explanations include local interactions between persistent viral particles at prior herpes infection sites, vascular injury, neural injury, and an altered immune response.1,5,6,10 The destruction of sensory nerve fibers by herpesviruses cause the release of neuropeptides that then modulate the local immune system and angiogenic responses.5,6 Our patient’s immunocompromised state may have further propagated a local altered immune cell infiltrate at the site of the isotopic response. Despite its unclear etiology, Wolf isotopic response should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any patient who presents with a dermatomal eruption at the site of a prior cutaneous infection, particularly after infection with herpes zoster. Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses with an excellent prognosis.11

We present a case of a cutaneous lupus erythematosus–like isotopic response that occurred at the site of a recent herpes zoster eruption in an immunocompromised patient without prior history of systemic or cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinical recognition of Wolf isotopic response is important for accurate histopathologic diagnosis and management. Continued investigation into the underlying pathogenesis should be performed to fully understand and better treat this process.

- Sharma RC, Sharma NL, Mahajan V, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: herpes simplex appearing on scrofuloderma scar. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:664-666.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. “Wolf’s isotopic response”: the originators speak their mind and set the record straight. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:416-418.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:110-113.

- Bardazzi F, Giacomini F, Savoia F, et al. Discoid chronic lupus erythematosus at the site of a previously healed cutaneous leishmaniasis: an example of isotopic response. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:44-46.

- Parimalam K, Kumar D, Thomas J. Discoid lupus erythematosis occurring as an isotopic response. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:50-51.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al. Viral diseases. In: James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020:362-420.

- Sharma RC, Sharma NL, Mahajan V, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response: herpes simplex appearing on scrofuloderma scar. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:664-666.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Wolf D. “Wolf’s isotopic response”: the originators speak their mind and set the record straight. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:416-418.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:110-113.

- Bardazzi F, Giacomini F, Savoia F, et al. Discoid chronic lupus erythematosus at the site of a previously healed cutaneous leishmaniasis: an example of isotopic response. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:44-46.

- Parimalam K, Kumar D, Thomas J. Discoid lupus erythematosis occurring as an isotopic response. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:50-51.

- Wolf R, Lotti T, Ruocco V. Isomorphic versus isotopic response: data and hypotheses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:123-125.

- James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al. Viral diseases. In: James W, Elston D, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020:362-420.

Practice Points

- Wolf isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new skin condition at the site of a previously healed and unrelated skin disorder; a granulomatous reaction is a commonly reported isotopic response.

- Treatment with topical or intralesional corticosteroids usually suffices for inflammatory-based isotopic responses.

Guttate Psoriasis Outcomes

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

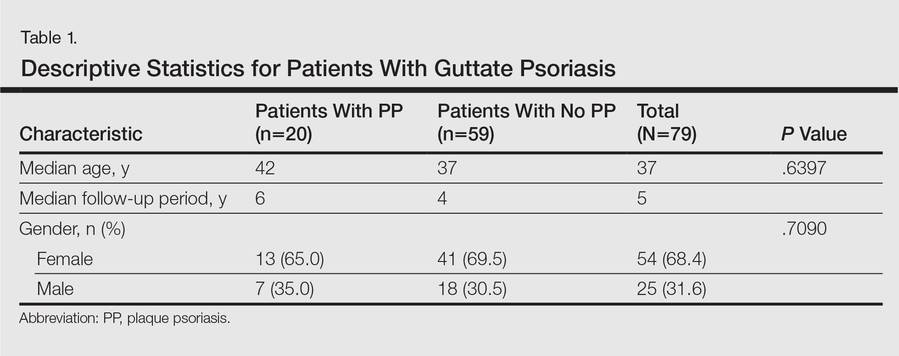

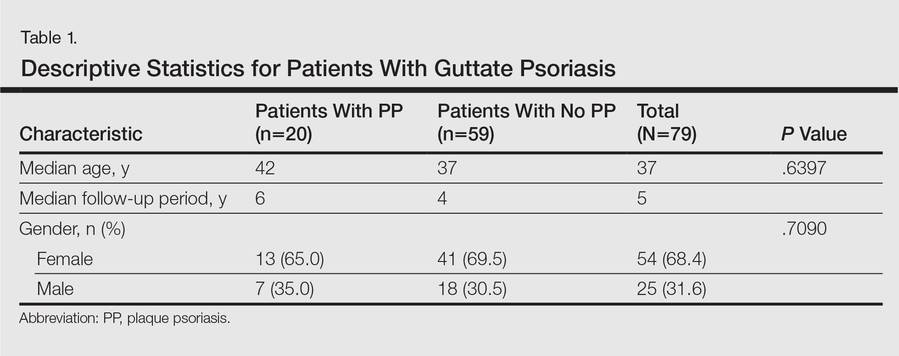

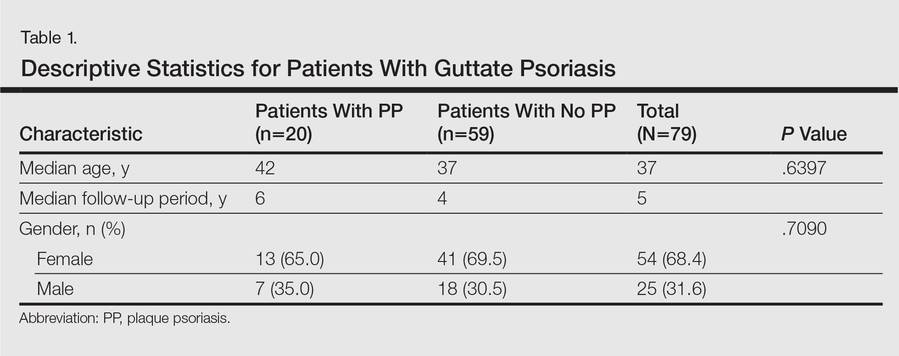

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

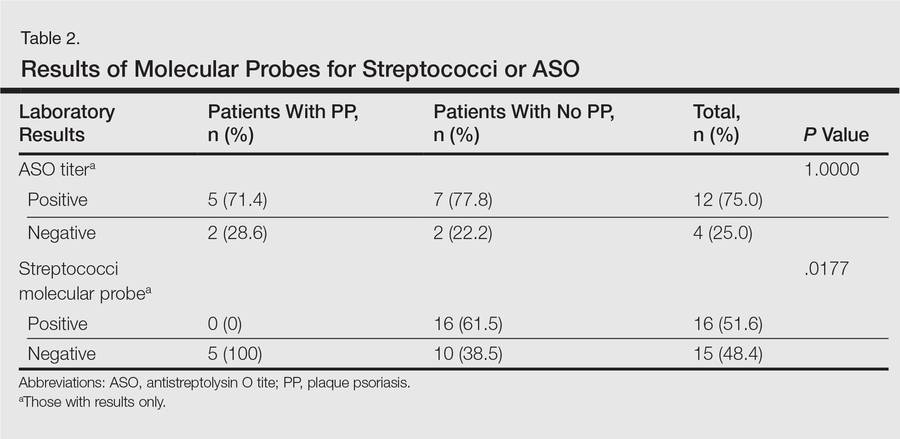

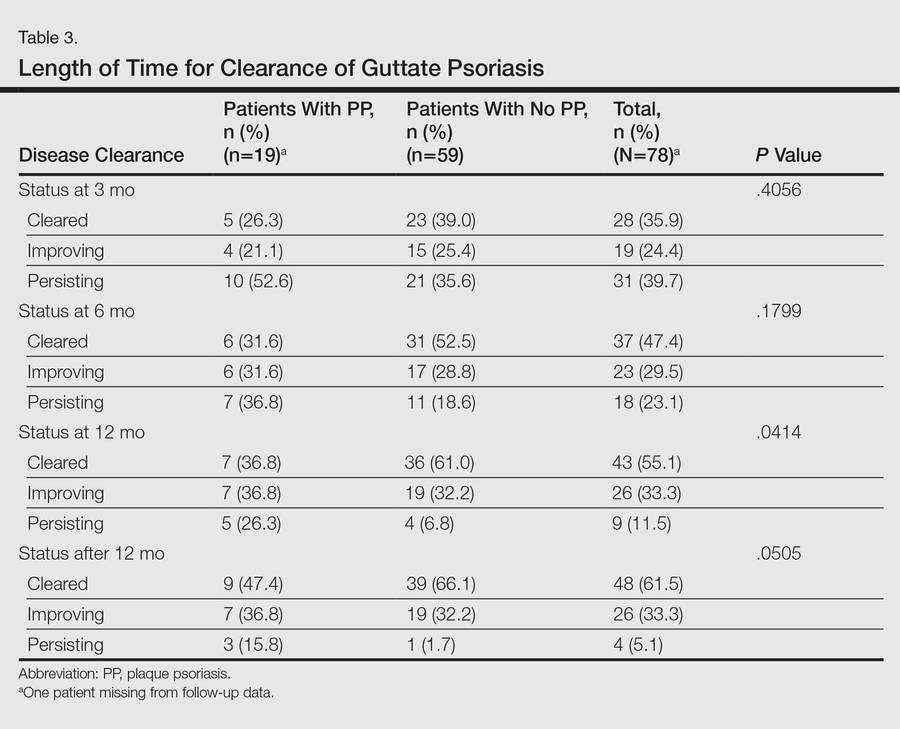

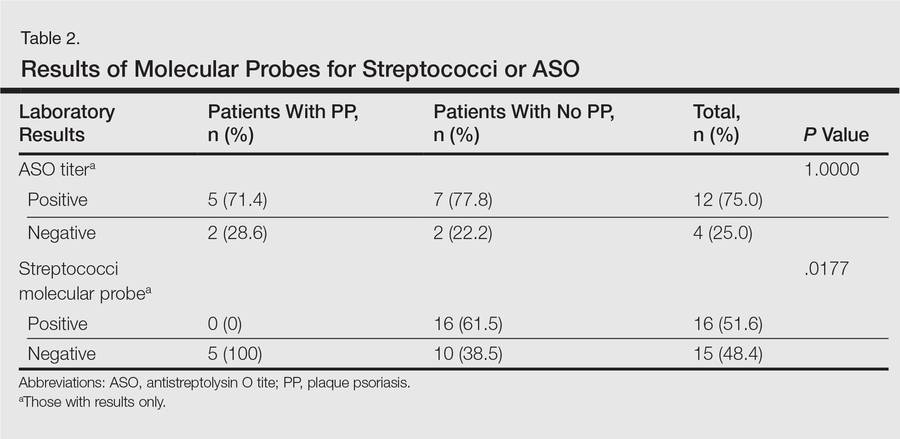

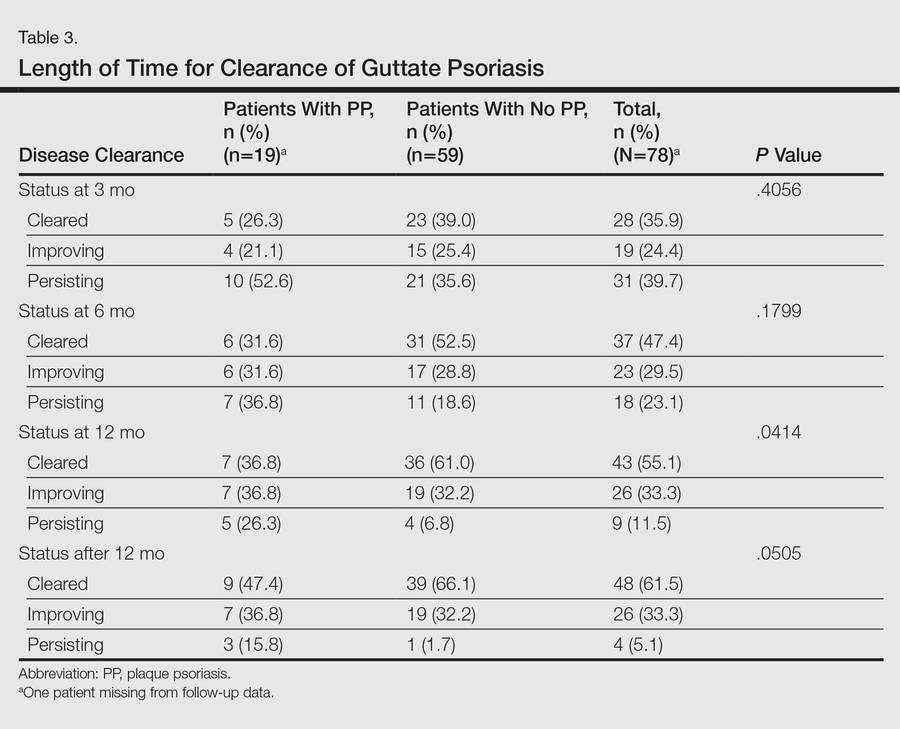

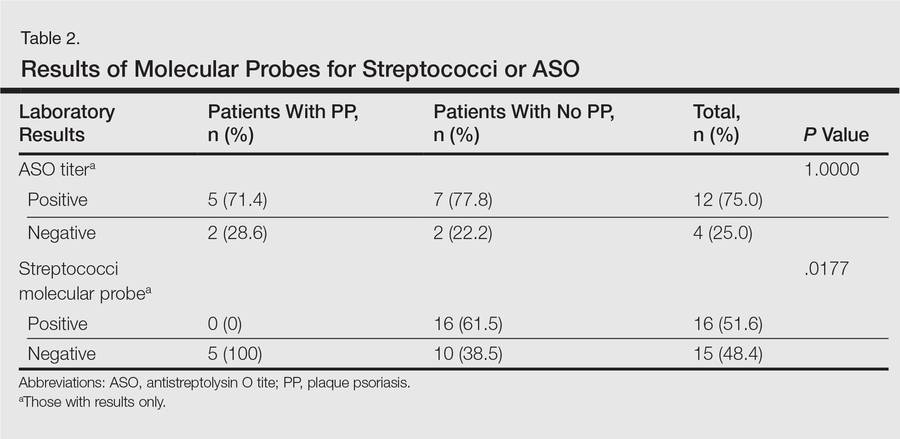

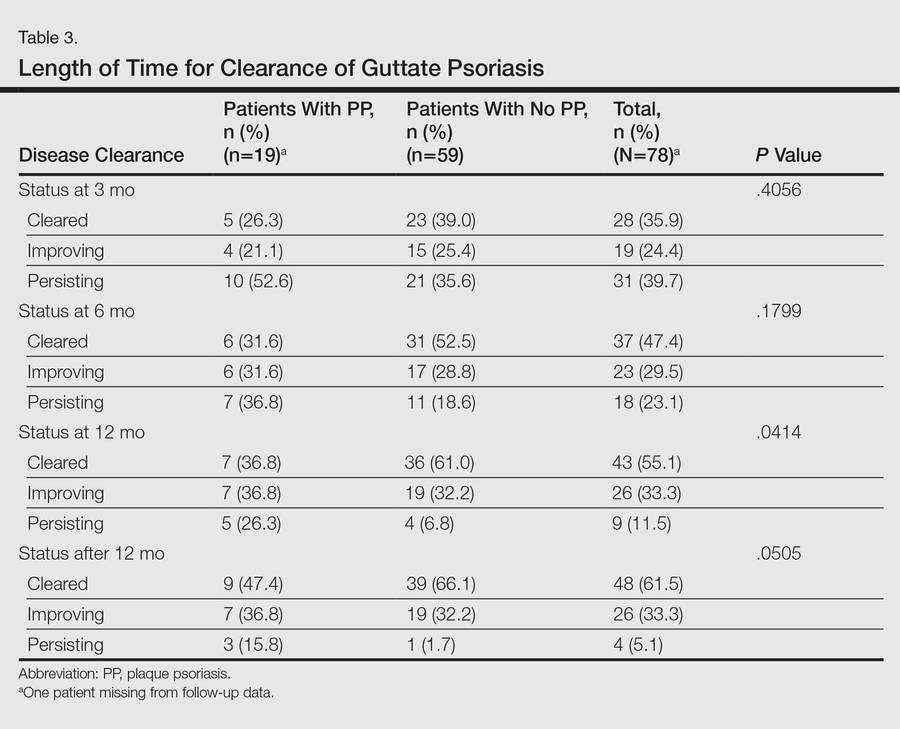

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

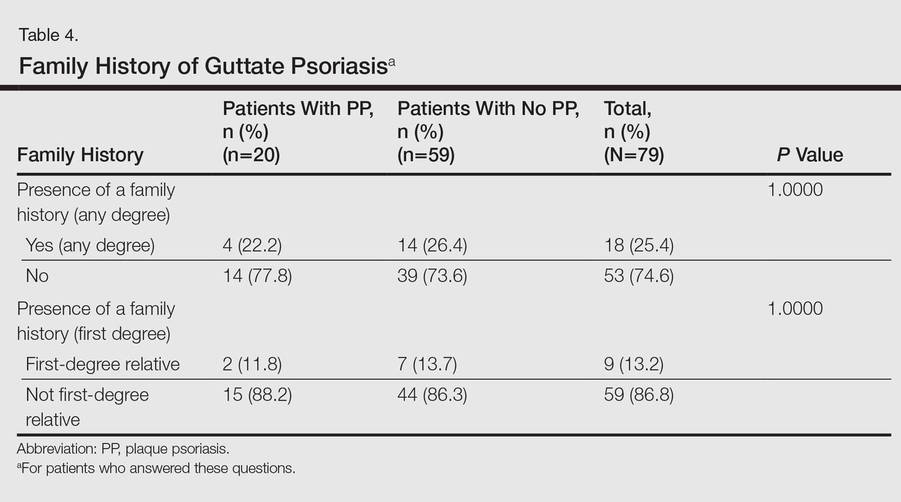

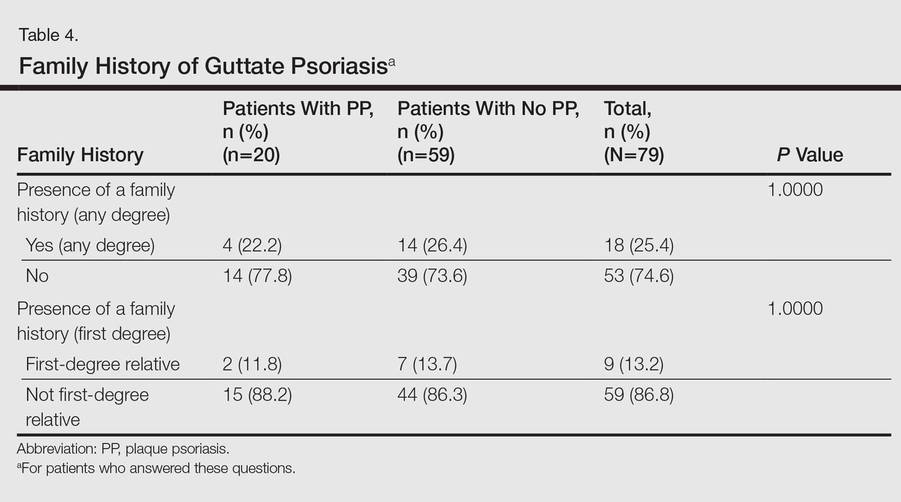

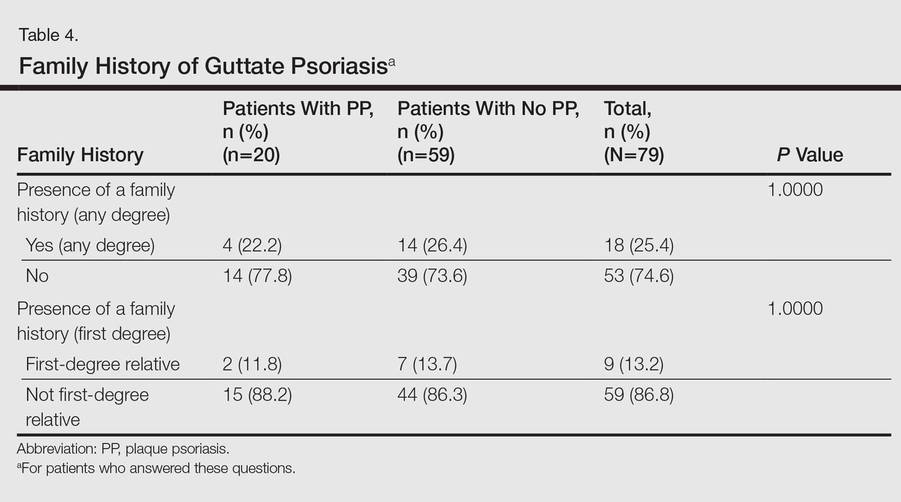

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

Practice Points

- Following an initial episode of guttate psoriasis, a patient has a 25.3% chance of developing plaque psoriasis (PP).

- A streptococci culture can be prognostic; if the culture is positive, the patient is less likely to develop PP.

- If the patient’s rash clears within 1 year, he/she is less likely to develop PP.