User login

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia

THE PRESENTATION

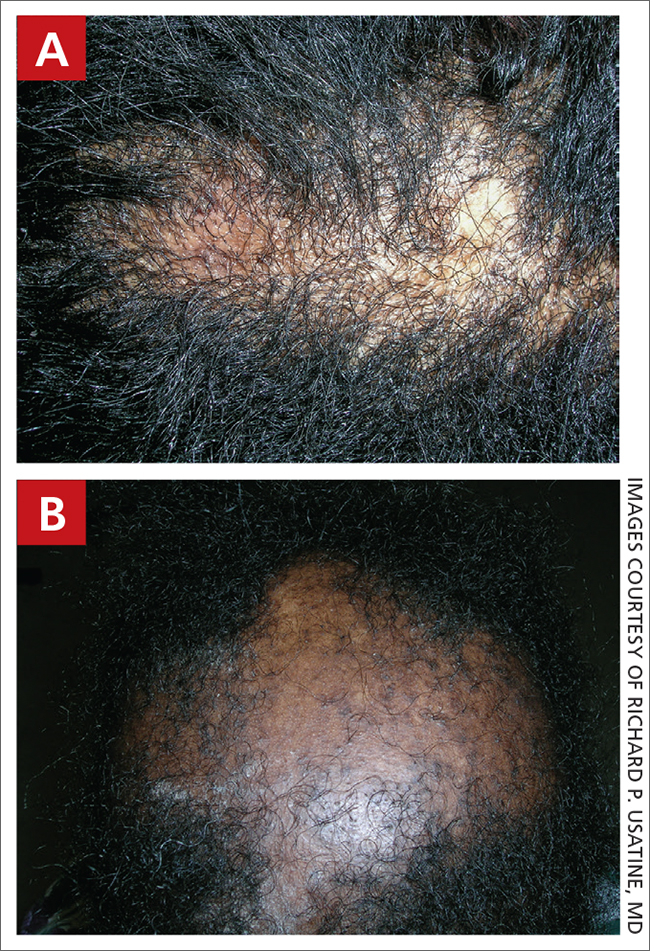

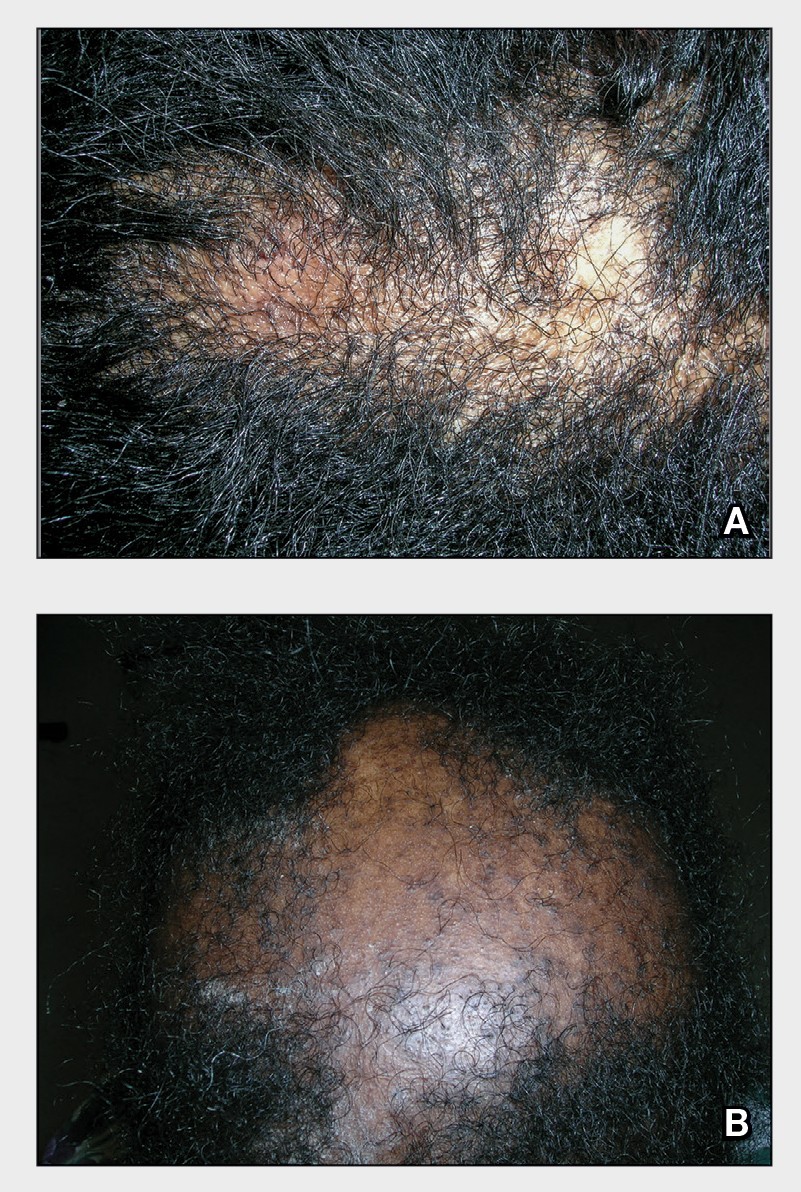

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.1 CCCA (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

CCCA predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. CCCA has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

- CCCA begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

- Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

- Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

- Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

- CCCA can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Continue to: Due to the inflammatory...

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral antiinflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

1. Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/ j.1600-0560.2001.280701.x

2. Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/ archderm.147.12.1453

3. Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111/ 1346-8138.14217

4. Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

5. Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

6. Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

7. Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056/ NEJMe1900042

8. Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

9. Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

10. Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/ j.jdcr.2019.12.008.

THE PRESENTATION

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.1 CCCA (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

CCCA predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. CCCA has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

- CCCA begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

- Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

- Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

- Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

- CCCA can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Continue to: Due to the inflammatory...

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral antiinflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

THE PRESENTATION

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.1 CCCA (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

CCCA predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. CCCA has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

- CCCA begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

- Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

- Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

- Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

- CCCA can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Continue to: Due to the inflammatory...

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral antiinflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

1. Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/ j.1600-0560.2001.280701.x

2. Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/ archderm.147.12.1453

3. Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111/ 1346-8138.14217

4. Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

5. Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

6. Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

7. Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056/ NEJMe1900042

8. Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

9. Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

10. Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/ j.jdcr.2019.12.008.

1. Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/ j.1600-0560.2001.280701.x

2. Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/ archderm.147.12.1453

3. Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111/ 1346-8138.14217

4. Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

5. Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

6. Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

7. Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056/ NEJMe1900042

8. Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

9. Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

10. Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/ j.jdcr.2019.12.008.

Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia

THE PRESENTATION

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA).1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

• Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

• Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

• Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral anti-inflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001 .280701.x

- Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/archderm.147.12.1453

- Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111 /1346-8138.14217

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

- Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

- Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

- Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe1900042

- Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

- Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

- Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/j .jdcr.2019.12.008

THE PRESENTATION

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA).1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

• Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

• Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

• Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral anti-inflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

THE PRESENTATION

A Early central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a small central patch of hair loss in a 45-year-old Black woman.

B Late central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia with a large central patch of hair loss in a 43-year-old Black woman.

Scarring alopecia is a collection of hair loss disorders including chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus), lichen planopilaris, dissecting cellulitis, acne keloidalis, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA).1 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (formerly hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome) is a progressive, scarring, inflammatory alopecia and represents the most common form of scarring alopecia in women of African descent. It results in permanent destruction of hair follicles.

Epidemiology

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects women of African descent but also may affect men. The prevalence of CCCA in those of African descent has varied in the literature. Khumalo2 reported a prevalence of 1.2% for women younger than 50 years and 6.7% in women older than 50 years. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia has been reported in other ethnic groups, such as those of Asian descent.3

Historically, hair care practices that are more common in those of African descent, such as high-tension hairstyles as well as heat and chemical hair relaxers, were implicated in the development of CCCA. However, the causes of CCCA are most likely multifactorial, including family history, genetic mutations, and hair care practices.4-7PADI3 mutations likely predispose some women to CCCA. Mutations in PADI3, which encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase 3 (an enzyme that modifies proteins crucial for the formation of hair shafts), were found in some patients with CCCA.8 Moreover, other genetic defects also likely play a role.7

Key clinical features

Early recognition is key for patients with CCCA.

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia begins in the central scalp (crown area, vertex) and spreads centrifugally.

• Scalp symptoms such as tenderness, pain, a tingling or crawling sensation, and itching may occur.9 Some patients may not have any symptoms at all, and hair loss may progress painlessly.

• Central hair breakage—forme fruste CCCA—may be a presenting sign of CCCA.9

• Loss of follicular ostia and mottled hypopigmented and hyperpigmented macules are common findings.6

• Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia can be diagnosed clinically and by histopathology.

Worth noting

Patients may experience hair loss and scalp symptoms for years before seeking medical evaluation. In some cultures, hair breakage or itching on the top of the scalp may be viewed as a normal occurrence in life.

It is important to set patient expectations that CCCA is a scarring alopecia, and the initial goal often is to maintain the patient's existing hair. However, hair and areas responding to treatment should still be treated. Without any intervention, the resulting scarring from CCCA may permanently scar follicles on the entire scalp.

Due to the inflammatory nature of CCCA, potent topical corticosteroids (eg, clobetasol propionate), intralesional corticosteroids (eg, triamcinolone acetonide), and oral anti-inflammatory agents (eg, doxycycline) are utilized in the treatment of CCCA. Minoxidil is another treatment option. Adjuvant therapies such as topical metformin also have been tried.10 Importantly, treatment of CCCA may halt further permanent destruction of hair follicles, but scalp symptoms may reappear periodically and require re-treatment with anti-inflammatory agents.

Health care highlight

Thorough scalp examination and awareness of clinical features of CCCA may prompt earlier diagnosis and prevent future severe permanent alopecia. Clinicians should encourage patients with suggestive signs or symptoms of CCCA to seek care from a dermatologist.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001 .280701.x

- Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/archderm.147.12.1453

- Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111 /1346-8138.14217

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

- Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

- Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

- Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe1900042

- Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

- Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

- Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/j .jdcr.2019.12.008

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001 .280701.x

- Khumalo NP. Prevalence of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1453-1454. doi:10.1001/archderm.147.12.1453

- Su HJ, Cheng AY, Liu CH, et al. Primary scarring alopecia: a retrospective study of 89 patients in Taiwan [published online January 16, 2018]. J Dermatol. 2018;45:450-455. doi:10.1111 /1346-8138.14217

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE. The histopathology of primary cicatricial alopecia. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:41-50

- Dlova NC, Forder M. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: possible familial aetiology in two African families from South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(supp 1):17-20, 20-23.

- Ogunleye TA, Quinn CR, McMichael A. Alopecia. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. McGraw Hill; 2016:253-264.

- Uitto J. Genetic susceptibility to alopecia [published online February 13, 2019]. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:873-876. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe1900042

- Malki L, Sarig O, Romano MT, et al. Variant PADI3 in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:833-841.

- Callender VD, Wright DR, Davis EC, et al. Hair breakage as a presenting sign of early or occult central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: clinicopathologic findings in 9 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1047-1052.

- Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/j .jdcr.2019.12.008

Discoid lupus

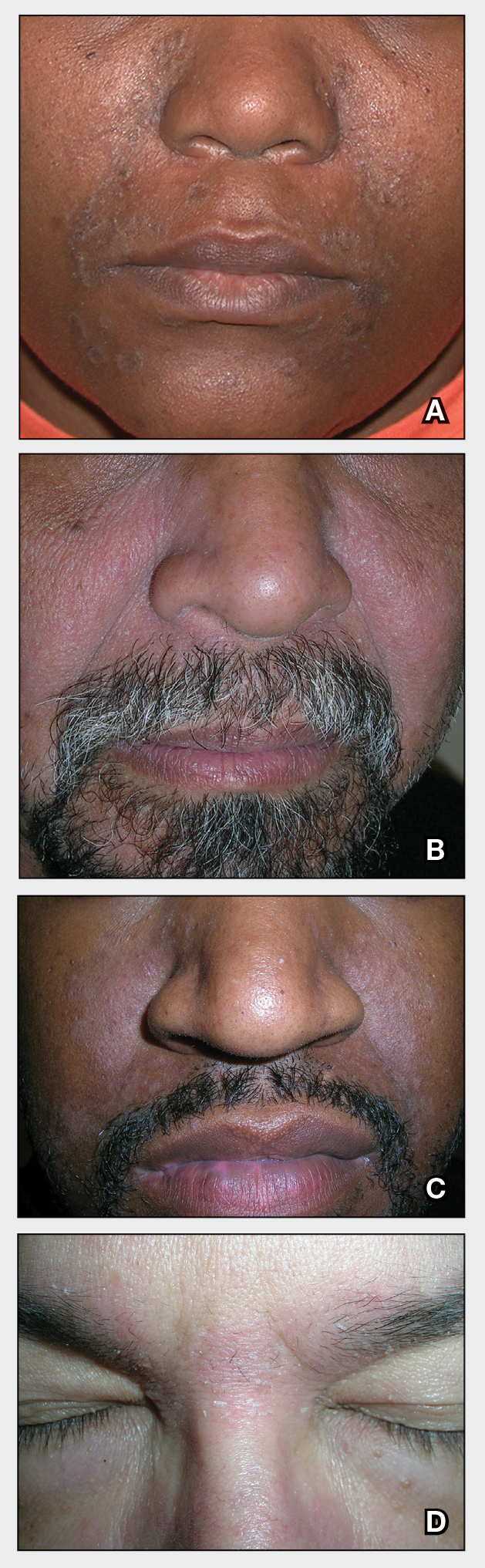

THE COMPARISON

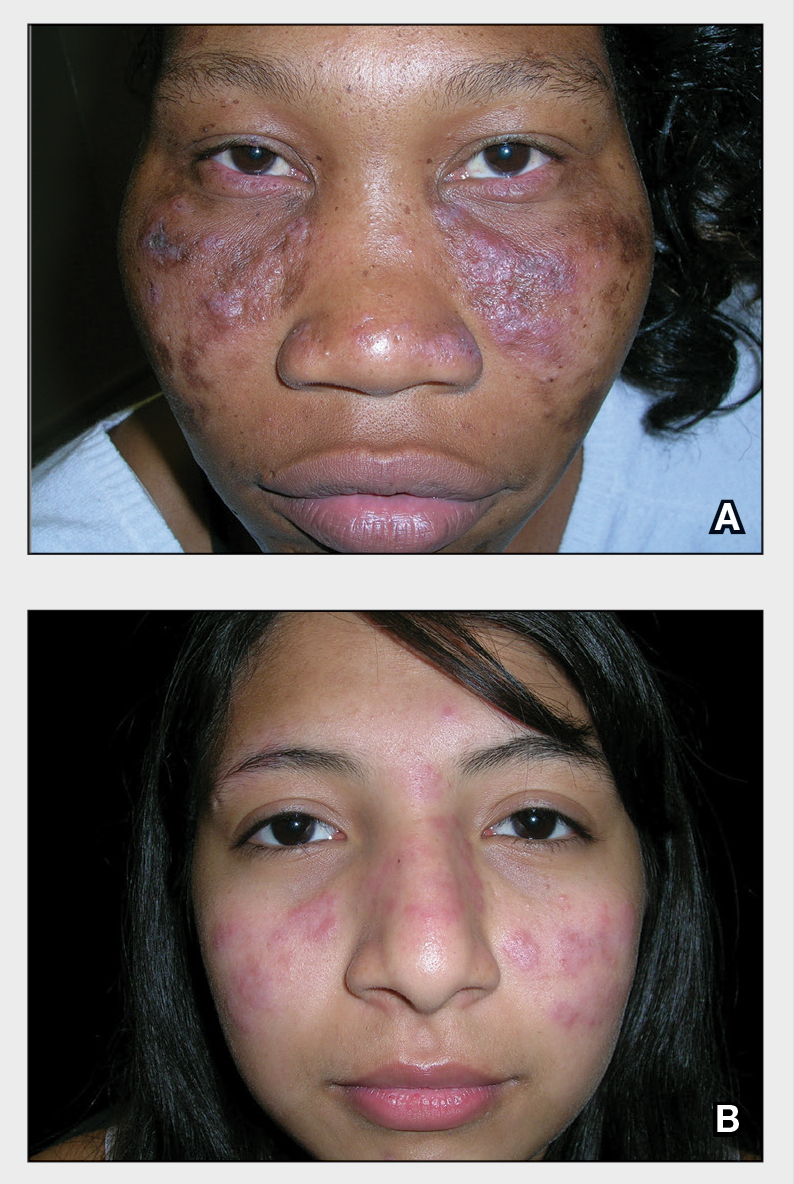

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

DLE is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

DLE lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. DLE lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

2. Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

3. Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

4. McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

5. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

6. Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

7. Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patient-physician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

8. Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

DLE is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

DLE lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. DLE lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

DLE is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

DLE lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. DLE lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

2. Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

3. Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

4. McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

5. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

6. Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

7. Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patient-physician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

8. Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

1. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

2. Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

3. Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

4. McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

5. Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

6. Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

7. Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patient-physician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

8. Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

Discoid Lupus

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

Sarcoidosis

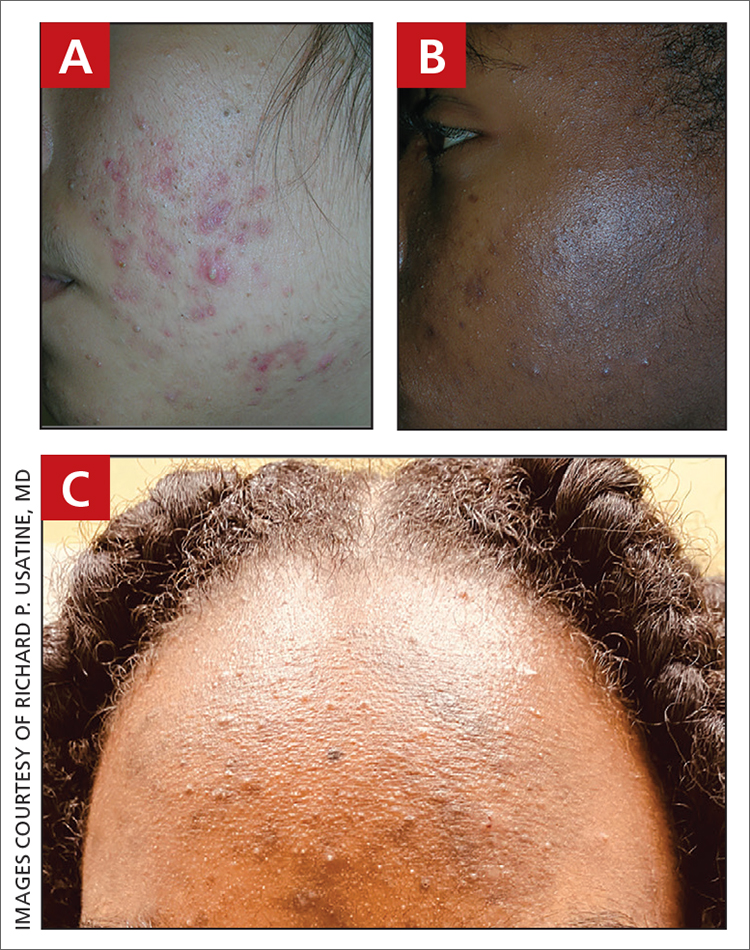

THE COMPARISON

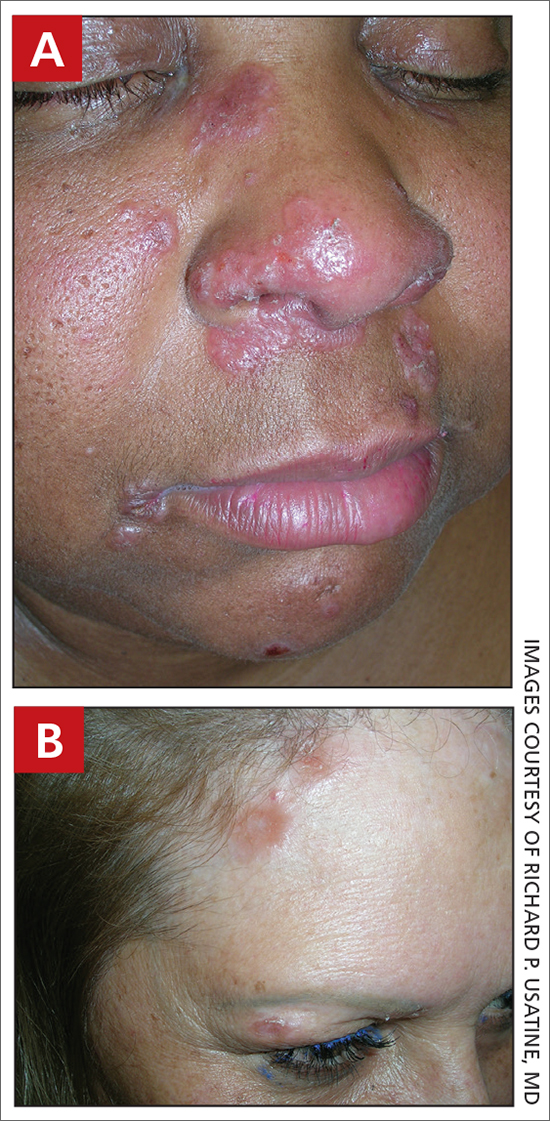

A Pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face, including the nasal alae, of a 52-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Orange and pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face of a 55-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that may affect the skin in addition to multiple body organ systems, including the lungs. Bilateral hilar adenopathy on a chest radiograph is the most common finding. Sarcoidosis also has a variety of cutaneous manifestations. Early diagnosis is vital, as patients with sarcoidosis and pulmonary fibrosis have a shortened life span compared to the overall population.1 With a growing skin of color population, it is important to recognize sarcoidosis as soon as possible.2

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest sarcoidosis prevalence in the United States.3 In the United States, the incidence of sarcoidosis in Black individuals peaks in the fourth decade of life. A 5-year study in a US health maintenance organization found that the age-adjusted annual incidence was 10.9 per 100,000 cases among Whites and 35.5 per 100,000 cases among Blacks.4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

• Papules are seen in sarcoidosis, primarily on the face, and may start as orange hued or yellow-brown and then become brown-red or pink to violaceous before involuting into faint macules.5-7

• When round or oval sarcoid plaques appear, they often are more erythematous.

• In skin of color, plaques may become hypopigmented.8

• Erythema nodosum, the most common nonspecific cutaneous lesion seen in sarcoidosis, is less commonly seen in those of African and Asian descent.9-11 This is in contrast to distinctive forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions such as lupus pernio and scar sarcoidosis, as well as papules and plaques and minor forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions including subcutaneous nodules; hypopigmented macules; psoriasiform lesions; and ulcerative, localized erythrodermic, ichthyosiform, scalp, and nail lesions.

• Lupus pernio is a cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis that appears on the face. It looks similar to lupus erythematosus and occurs most commonly in women of African descent.8,12

• Hypopigmented lesions are more common in those with darker skin tones.9

• Ulcerative lesions are more common in those of African descent and women.13

• Scalp sarcoidosis is more common in patients of African descent.14

• Sarcoidosis may develop at sites of trauma, such as scars and tattoos.15-17

Worth noting

The cutaneous lesions seen in sarcoidosis may be emotionally devastating and disfiguring. Due to the variety of clinical manifestations, sarcoidosis may be misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.18

Health disparity highlight

Patients older than 40 years presenting with sarcoidosis and those of African descent have a worse prognosis.19 Despite adjustment for race, ethnic group, age, and sex, patients with low income and financial barriers present with more severe sarcoidosis.20

1. Nardi A, Brillet P-Y, Letoumelin P, et al. Stage IV sarcoidosis: comparison of survival with the general population and causes of death. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1368-1373.

2. Heath CR, David J, Taylor SC. Sarcoidosis: are there differences in your skin of color patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66: 121.e1-121.e14.

3. Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, et al. Sarcoidosis: a clinical overview from symptoms to diagnosis. Cells. 2021;10:766. doi:10.3390/ cells10040766

4. Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J Jr, et al. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:234-241. doi:10.1093/ oxfordjournals.aje.a009096

5. Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Sharma RC, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical profile of 23 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2007;73:16-21.

6. Yanardag H, Pamuk ON, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978-982.

7. Olive KE, Kartaria YP. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis to other organ system involvement, abnormal laboratory measurements, and disease course. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1811-1814.

8. Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis. relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888. doi:10.1001/archderm.1997.03890430098013

9. Minus HR, Grimes PE. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:361-364.

10. Edmondstone WM, Wilson AG. Sarcoidosis in Caucasians, blacks and Asians in London. Br J Dis Chest. 1985;79:27-36.

11. James DG, Neville E, Siltzbach LE. Worldwide review of sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;278:321-334.

12. Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149-173.

13. Albertini JG, Tyler W, Miller OF III. Ulcerative sarcoidosis: case report and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:215-219.

14. Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

15. Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

16. Chudomirova K, Velichkva L, Anavi B. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2003;17:360-361.

17. Kim YC, Triffet MK, Gibson LE. Foreign bodies in sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:408-412.

18. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2153-2165.

19. Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, et al. Sarcoidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:46. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-46

20. Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885-1889.

THE COMPARISON

A Pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face, including the nasal alae, of a 52-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Orange and pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face of a 55-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that may affect the skin in addition to multiple body organ systems, including the lungs. Bilateral hilar adenopathy on a chest radiograph is the most common finding. Sarcoidosis also has a variety of cutaneous manifestations. Early diagnosis is vital, as patients with sarcoidosis and pulmonary fibrosis have a shortened life span compared to the overall population.1 With a growing skin of color population, it is important to recognize sarcoidosis as soon as possible.2

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest sarcoidosis prevalence in the United States.3 In the United States, the incidence of sarcoidosis in Black individuals peaks in the fourth decade of life. A 5-year study in a US health maintenance organization found that the age-adjusted annual incidence was 10.9 per 100,000 cases among Whites and 35.5 per 100,000 cases among Blacks.4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

• Papules are seen in sarcoidosis, primarily on the face, and may start as orange hued or yellow-brown and then become brown-red or pink to violaceous before involuting into faint macules.5-7

• When round or oval sarcoid plaques appear, they often are more erythematous.

• In skin of color, plaques may become hypopigmented.8

• Erythema nodosum, the most common nonspecific cutaneous lesion seen in sarcoidosis, is less commonly seen in those of African and Asian descent.9-11 This is in contrast to distinctive forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions such as lupus pernio and scar sarcoidosis, as well as papules and plaques and minor forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions including subcutaneous nodules; hypopigmented macules; psoriasiform lesions; and ulcerative, localized erythrodermic, ichthyosiform, scalp, and nail lesions.

• Lupus pernio is a cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis that appears on the face. It looks similar to lupus erythematosus and occurs most commonly in women of African descent.8,12

• Hypopigmented lesions are more common in those with darker skin tones.9

• Ulcerative lesions are more common in those of African descent and women.13

• Scalp sarcoidosis is more common in patients of African descent.14

• Sarcoidosis may develop at sites of trauma, such as scars and tattoos.15-17

Worth noting

The cutaneous lesions seen in sarcoidosis may be emotionally devastating and disfiguring. Due to the variety of clinical manifestations, sarcoidosis may be misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.18

Health disparity highlight

Patients older than 40 years presenting with sarcoidosis and those of African descent have a worse prognosis.19 Despite adjustment for race, ethnic group, age, and sex, patients with low income and financial barriers present with more severe sarcoidosis.20

THE COMPARISON

A Pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face, including the nasal alae, of a 52-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Orange and pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face of a 55-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that may affect the skin in addition to multiple body organ systems, including the lungs. Bilateral hilar adenopathy on a chest radiograph is the most common finding. Sarcoidosis also has a variety of cutaneous manifestations. Early diagnosis is vital, as patients with sarcoidosis and pulmonary fibrosis have a shortened life span compared to the overall population.1 With a growing skin of color population, it is important to recognize sarcoidosis as soon as possible.2

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest sarcoidosis prevalence in the United States.3 In the United States, the incidence of sarcoidosis in Black individuals peaks in the fourth decade of life. A 5-year study in a US health maintenance organization found that the age-adjusted annual incidence was 10.9 per 100,000 cases among Whites and 35.5 per 100,000 cases among Blacks.4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

• Papules are seen in sarcoidosis, primarily on the face, and may start as orange hued or yellow-brown and then become brown-red or pink to violaceous before involuting into faint macules.5-7

• When round or oval sarcoid plaques appear, they often are more erythematous.

• In skin of color, plaques may become hypopigmented.8

• Erythema nodosum, the most common nonspecific cutaneous lesion seen in sarcoidosis, is less commonly seen in those of African and Asian descent.9-11 This is in contrast to distinctive forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions such as lupus pernio and scar sarcoidosis, as well as papules and plaques and minor forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions including subcutaneous nodules; hypopigmented macules; psoriasiform lesions; and ulcerative, localized erythrodermic, ichthyosiform, scalp, and nail lesions.

• Lupus pernio is a cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis that appears on the face. It looks similar to lupus erythematosus and occurs most commonly in women of African descent.8,12

• Hypopigmented lesions are more common in those with darker skin tones.9

• Ulcerative lesions are more common in those of African descent and women.13

• Scalp sarcoidosis is more common in patients of African descent.14

• Sarcoidosis may develop at sites of trauma, such as scars and tattoos.15-17

Worth noting

The cutaneous lesions seen in sarcoidosis may be emotionally devastating and disfiguring. Due to the variety of clinical manifestations, sarcoidosis may be misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.18

Health disparity highlight

Patients older than 40 years presenting with sarcoidosis and those of African descent have a worse prognosis.19 Despite adjustment for race, ethnic group, age, and sex, patients with low income and financial barriers present with more severe sarcoidosis.20

1. Nardi A, Brillet P-Y, Letoumelin P, et al. Stage IV sarcoidosis: comparison of survival with the general population and causes of death. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1368-1373.

2. Heath CR, David J, Taylor SC. Sarcoidosis: are there differences in your skin of color patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66: 121.e1-121.e14.

3. Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, et al. Sarcoidosis: a clinical overview from symptoms to diagnosis. Cells. 2021;10:766. doi:10.3390/ cells10040766

4. Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J Jr, et al. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:234-241. doi:10.1093/ oxfordjournals.aje.a009096

5. Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Sharma RC, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical profile of 23 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2007;73:16-21.

6. Yanardag H, Pamuk ON, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978-982.

7. Olive KE, Kartaria YP. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis to other organ system involvement, abnormal laboratory measurements, and disease course. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1811-1814.

8. Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis. relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888. doi:10.1001/archderm.1997.03890430098013

9. Minus HR, Grimes PE. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:361-364.

10. Edmondstone WM, Wilson AG. Sarcoidosis in Caucasians, blacks and Asians in London. Br J Dis Chest. 1985;79:27-36.

11. James DG, Neville E, Siltzbach LE. Worldwide review of sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;278:321-334.

12. Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149-173.

13. Albertini JG, Tyler W, Miller OF III. Ulcerative sarcoidosis: case report and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:215-219.

14. Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

15. Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

16. Chudomirova K, Velichkva L, Anavi B. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2003;17:360-361.

17. Kim YC, Triffet MK, Gibson LE. Foreign bodies in sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:408-412.

18. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2153-2165.

19. Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, et al. Sarcoidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:46. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-46

20. Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885-1889.

1. Nardi A, Brillet P-Y, Letoumelin P, et al. Stage IV sarcoidosis: comparison of survival with the general population and causes of death. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1368-1373.

2. Heath CR, David J, Taylor SC. Sarcoidosis: are there differences in your skin of color patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66: 121.e1-121.e14.

3. Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, et al. Sarcoidosis: a clinical overview from symptoms to diagnosis. Cells. 2021;10:766. doi:10.3390/ cells10040766

4. Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J Jr, et al. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:234-241. doi:10.1093/ oxfordjournals.aje.a009096

5. Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Sharma RC, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical profile of 23 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2007;73:16-21.

6. Yanardag H, Pamuk ON, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978-982.

7. Olive KE, Kartaria YP. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis to other organ system involvement, abnormal laboratory measurements, and disease course. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1811-1814.

8. Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis. relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888. doi:10.1001/archderm.1997.03890430098013

9. Minus HR, Grimes PE. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:361-364.

10. Edmondstone WM, Wilson AG. Sarcoidosis in Caucasians, blacks and Asians in London. Br J Dis Chest. 1985;79:27-36.

11. James DG, Neville E, Siltzbach LE. Worldwide review of sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;278:321-334.

12. Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149-173.

13. Albertini JG, Tyler W, Miller OF III. Ulcerative sarcoidosis: case report and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:215-219.

14. Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

15. Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

16. Chudomirova K, Velichkva L, Anavi B. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2003;17:360-361.

17. Kim YC, Triffet MK, Gibson LE. Foreign bodies in sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:408-412.

18. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2153-2165.

19. Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, et al. Sarcoidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:46. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-46

20. Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885-1889.

Sarcoidosis

THE COMPARISON

A Pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face, including the nasal alae, of a 52-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Orange and pink, elevated, granulomatous, indurated plaques on the face of a 55-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that may affect the skin in addition to multiple body organ systems, including the lungs. Bilateral hilar adenopathy on a chest radiograph is the most common finding. Sarcoidosis also has a variety of cutaneous manifestations. Early diagnosis is vital, as patients with with sarcoidosis and pulmonary fibrosis have a shortened life span compared to the overall population.1 With a growing skin of color population, it is important to recognize sarcoidosis as soon as possible.2

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest sarcoidosis prevalence in the United States.3 In the United States, the incidence of sarcoidosis in Black individuals peaks in the fourth decade of life. A 5-year study in a US health maintenance organization found that the age-adjusted annual incidence was 10.9 per 100,000 cases among Whites and 35.5 per 100,000 cases among Blacks.4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

• Papules are seen in sarcoidosis, primarily on the face, and may start as orange hued or yellow-brown and then become brown-red or pink to violaceous before involuting into faint macules.5-7

• When round or oval sarcoid plaques appear, they often are more erythematous. In skin of color, plaques may become hypopigmented.8

• Erythema nodosum, the most common nonspecific cutaneous lesion seen in sarcoidosis, is less commonly seen in those of African and Asian descent.9-11 This is in contrast to distinctive forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions such as lupus pernio and scar sarcoidosis, as well as papules and plaques and minor forms of specific sarcoid skin lesions including subcutaneous nodules; hypopigmented macules; psoriasiform lesions; and ulcerative, localized erythrodermic, ichthyosiform, scalp, and nail lesions.

• Lupus pernio is a cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis that appears on the face. It looks similar to lupus erythematosus and occurs most commonly in women of African descent.8,12

• Hypopigmented lesions are more common in those with darker skin tones.9

• Ulcerative lesions are more common in those of African descent and women.13

• Scalp sarcoidosis is more common in patients of African descent.14

• Sarcoidosis may develop at sites of trauma, such as scars and tattoos.15-17

Worth noting

The cutaneous lesions seen in sarcoidosis may be emotionally devastating and disfiguring. Due to the variety of clinical manifestations, sarcoidosis may be misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.18

Health disparity highlight

Patients older than 40 years presenting with sarcoidosis and those of African descent have a worse prognosis.19 Despite adjusting for race, ethnic group, age, and sex, patients with low income and financial barriers present with more severe sarcoidosis.20

- Nardi A, Brillet P-Y, Letoumelin P, et al. Stage IV sarcoidosis: comparison of survival with the general population and causes of death. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1368-1373.

- Heath CR, David J, Taylor SC. Sarcoidosis: are there differences in your skin of color patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:121.e1-121.e14.

- Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, et al. Sarcoidosis: a clinical overview from symptoms to diagnosis. Cells. 2021;10:766. doi:10.3390/cells10040766

- Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J Jr, et al. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:234-241. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009096

- Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Sharma RC, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: clinical profile of 23 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2007;73:16-21.

- Yanardag H, Pamuk ON, Karayel T. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis if the features in 170 patients. Respir Med. 2003;97:978-982.

- Olive KE, Kartaria YP. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis to other organ system involvement, abnormal laboratory measurements, and disease course. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1811-1814.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis. relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888. doi:10.1001/archderm.1997.03890430098013

- Minus HR, Grimes PE. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32:361-364.

- Edmondstone WM, Wilson AG. Sarcoidosis in Caucasians, blacks and Asians in London. Br J Dis Chest. 1985;79:27-36.

- James DG, Neville E, Siltzbach LE. Worldwide review of sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976;278:321-334.

- Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149-173.

- Albertini JG, Tyler W, Miller OF III. Ulcerative sarcoidosis: case report and review of literature. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:215-219.