User login

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

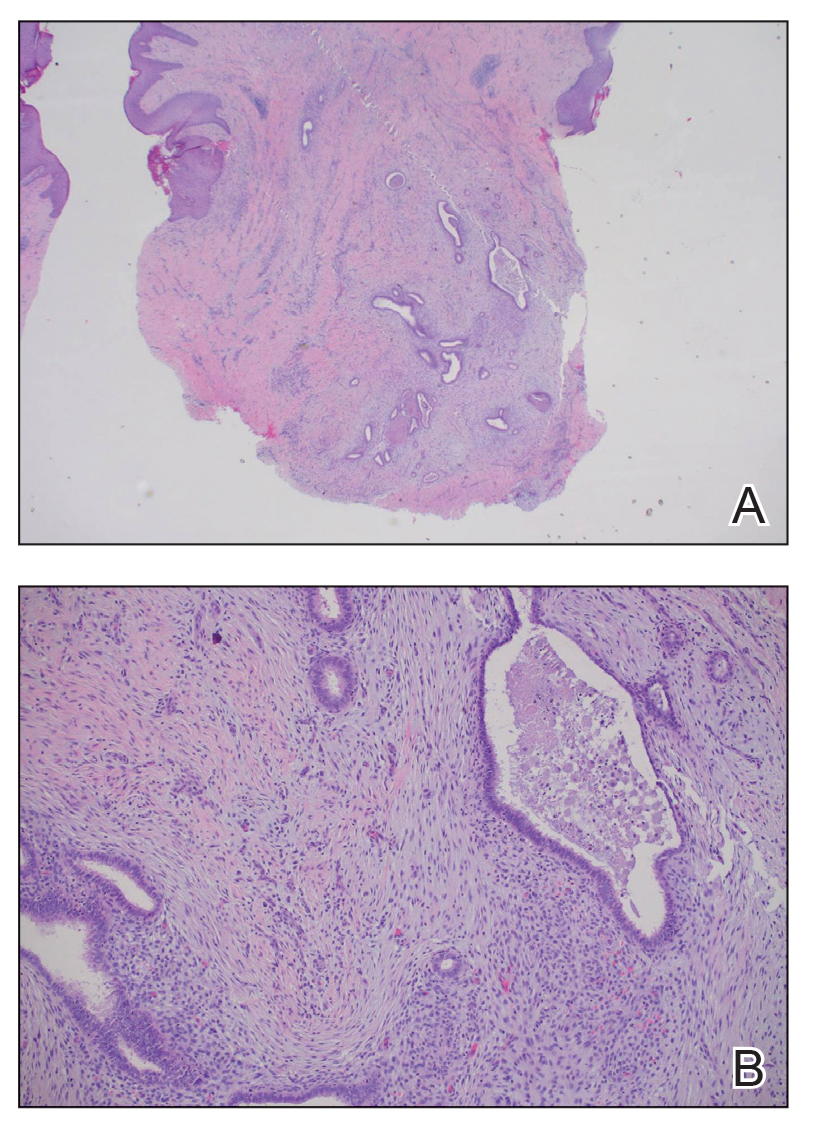

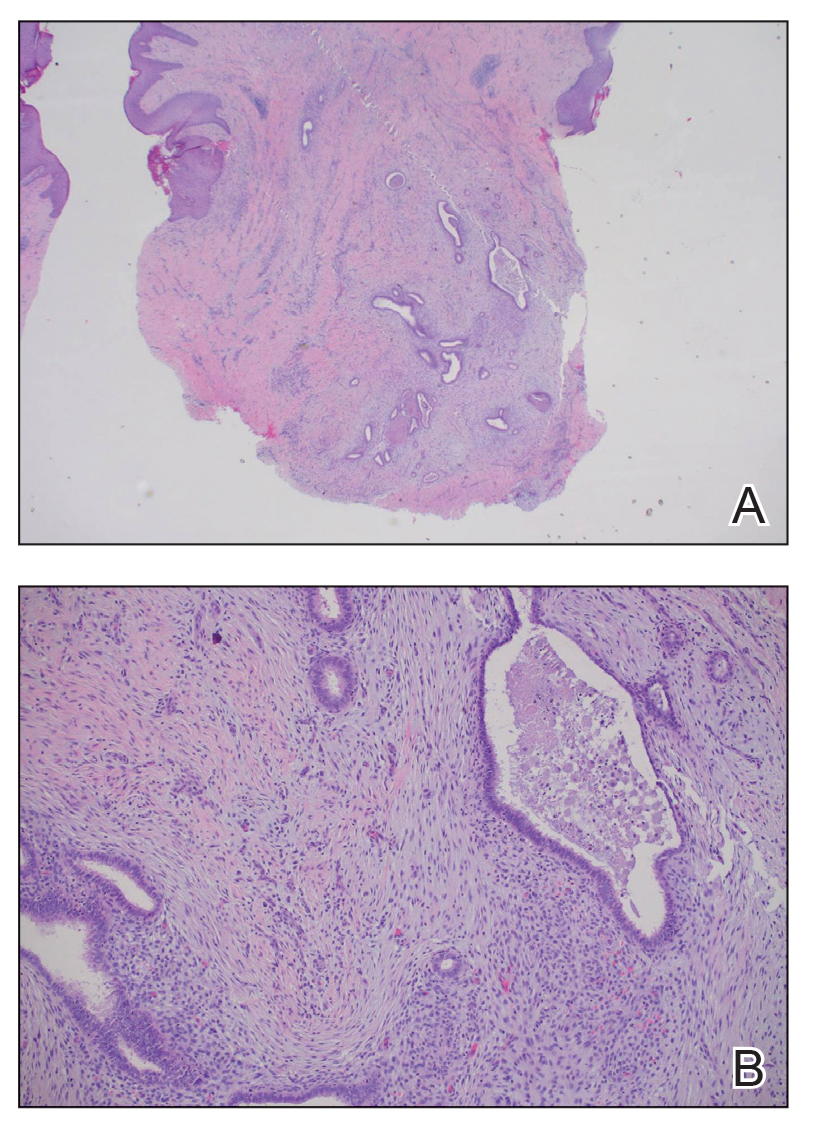

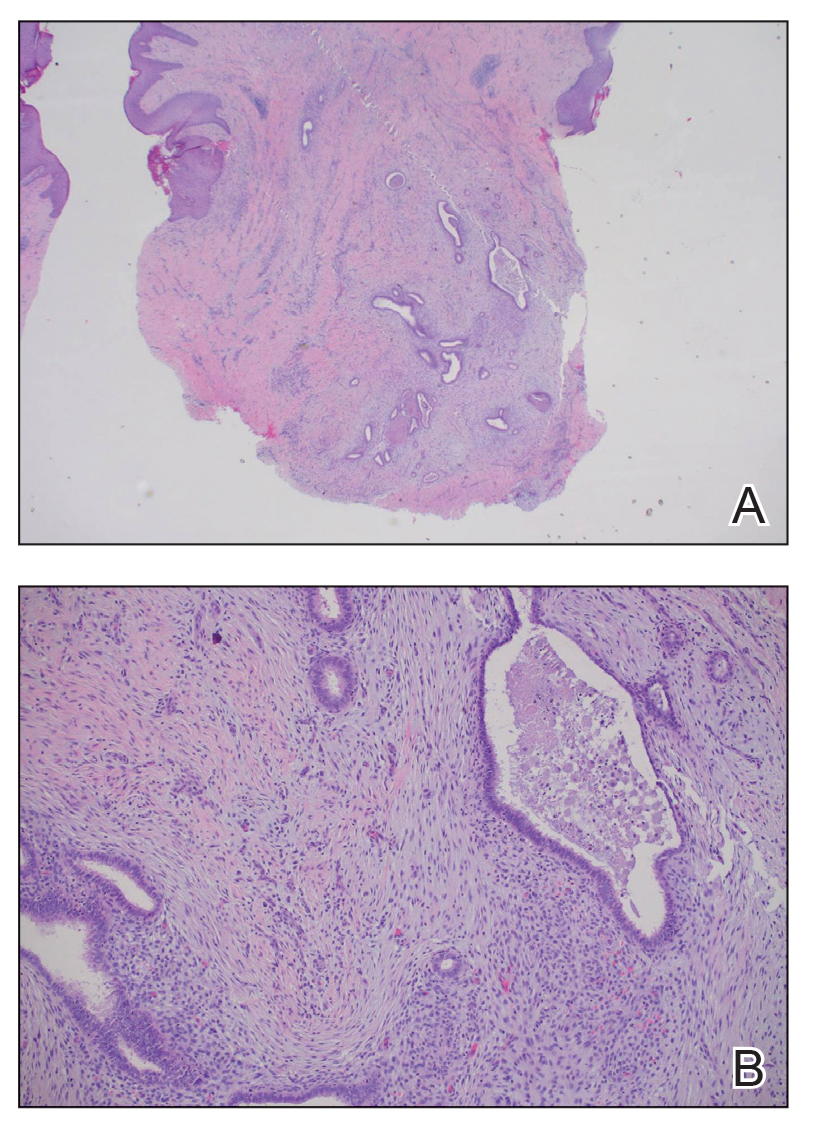

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

A 25-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic by her primary care provider for evaluation of a tender nodule on the inferior umbilicus of 2 years' duration at the site of a preexisting keloid scar. The patient reported that the lesion caused occasional pain and tenderness. A few weeks prior to the current presentation, a dark-red bloody discharge developed at the superior aspect of the lesion that subsequently crusted over. The patient denied any use of oral contraceptives or history of abdominal surgery.

The original keloid scar had been treated successfully by an outside physician with intralesional steroid injections, and the patient was interested in a similar procedure for the current nodule. She also had a history of a hyperpigmented hypertrophic scar on the superior periumbilical area from a previous piercing that had resolved several years prior to presentation.

Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 1.2-cm, soft, tender, violaceous nodule with scant yellow crust along the superior surface of the umbilicus. There was no palpable abdominal wall defect, and the nodule was not reducible into the abdominal cavity. An interval history revealed bleeding of the lesion during the patient's menstrual cycle with persistent pain and tenderness. A punch biopsy was performed.

Progressively Worsening Scaly Patches and Plaques in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

The Diagnosis: Erythrodermic Allergic Contact Dermatitis

The worsening symptoms in our patient prompted intervention rather than observation and reassurance. Contact allergy to lanolin was suspected given the worsening presentation after the addition of Minerin, which was immediately discontinued. The patient’s family applied betamethasone cream 0.1% twice daily to severe plaques, pimecrolimus cream 1% to the face, and triamcinolone cream 0.1% to the rest of the body. At follow-up 1 week later, he experienced complete resolution of symptoms, which supported the diagnosis of erythrodermic allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).

The prevalence of ACD caused by lanolin varies among the general population from 1.2% to 6.9%.1 Lanolin recently was named Allergen of the Year in 2023 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.2 It can be found in various commercial products, including creams, soaps, and ointments. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common pediatric inflammatory skin disorder that typically is treated with these products.3 In a study analyzing 533 products, up to 6% of skin care products for babies and children contained lanolin.4 Therefore, exposure to lanolin-containing products may be fairly common in the pediatric population.

Lanolin is a fatlike substance derived from sheep sebaceous gland secretions and extracted from sheep’s wool. Its composition varies by sheep breed, location, and extraction and purification methods. The most common allergens involve the alcoholic fraction produced by hydrolysis of lanolin.4 In 1996, Wolf5 described the “lanolin paradox,” which argued the difficulty with identifying lanolin as an allergen (similar to Fisher’s “paraben paradox”) based on 4 principles: (1) lanolin-containing topical medicaments tend to be more sensitizing than lanolin-containing cosmetics; (2) patients with ACD after applying lanolin-containing topical medicaments to damaged or ulcerated skin often can apply lanolin-containing cosmetics to normal or unaffected skin without a reaction; (3) false-negative patch test results often occur in lanolin-sensitive patients; and (4) patch testing with a single lanolin-containing agent (lanolin alcohol [30% in petrolatum]) is an unreliable and inadequate method of detecting lanolin allergy.6,7 This theory elucidates the challenge of diagnosing contact allergies, particularly lanolin contact allergies.

Clinical features of acute ACD vary by skin type. Lighter skin types may have well-demarcated, pruritic, eczematous patches and plaques affecting the flexor surfaces. Asian patients may present with psoriasiform plaques with more well-demarcated borders and increased scaling and lichenification. In patients with darker skin types, dermatitis may manifest as papulation, lichenification, and color changes (violet, gray, or darker brown) along extensor surfaces.8 Chronic dermatitis manifests as lichenified scaly plaques. Given the diversity in dermatitis manifestation and the challenges of identifying erythema, especially in skin of color, clinicians may misidentify disease severity. These features aid in diagnosing and treating patients presenting with diffuse erythroderma and worsening eczematous patches and plaques despite use of typical topical treatments.

The differential diagnosis includes irritant contact dermatitis, AD, seborrheic dermatitis, and chronic plaque psoriasis. Negative patch testing suggests contact dermatitis based on exposure to a product. A thorough medication and personal history helps distinguish ACD from AD. Atopic dermatitis classically appears on the flexural areas, face, eyelids, and hands of patients with a personal or family history of atopy. Greasy scaly plaques on the central part of the face, eyelids, and scalp commonly are found in seborrheic dermatitis. In chronic plaque psoriasis, lesions typically are described as welldemarcated, inflamed plaques with notable scale located primarily in the scalp and diaper area in newborns and children until the age of 2 years. Our patient presented with scaly plaques throughout most of the body. The history of Minerin use over the course of 3 to 5 months and worsening skin eruptions involving a majority of the skin surface suggested continued exposure.

Patch testing assists in the diagnosis of ACD, with varying results due to manufacturing and processing inconsistencies in the composition of various substances used in the standard test sets, often making it difficult to diagnose lanolin as an allergen. According to Lee and Warshaw,6 the lack of uniformity within testing of lanolin-containing products may cause false-positive results, poor patch-test reproducibility, and loss of allergic contact response. A 2019 study utilized a combination of Amerchol L101 and lanolin alcohol to improve the diagnosis of lanolin allergy, as standard testing may not identify patients with lanolin sensitivities.1 A study with the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2005 to 2012 demonstrated that positive patch testing among children was the most consistent method for diagnosing ACD, and results were clinically relevant.9 However, the different lanolin-containing products are not standardized in patch testing, which often causes mixed reactions and does not definitely demonstrate classic positive results, even with the use of repeated open application tests.2 Although there has been an emphasis on refining the standardization of the lanolin used for patch testing, lanolin contact allergy remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis.

Both AD and ACD are common pediatric skin findings, and mixed positive and neutral associations between AD and allergy to lanolin have been described in a few studies.1,3,9,10 A history of atopy is more notable in a pediatric patient vs an adult, as sensitivities tend to subside into adulthood.9 Further studies and more precise testing are needed to investigate the relationship between AD and ACD.

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

- Knijp J, Bruynzeel DP, Rustemeyer T. Diagnosing lanolin contact allergy with lanolin alcohol and Amerchol L101. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:298-303. doi:10.1111/cod.13210

- Jenkins BA, Belsito DV. Lanolin. Dermatitis. 2023;34:4-12. doi:10.1089 /derm.2022.0002

- Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, et al. Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:765-770. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol .2016.6136

- Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, de la Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018; 29:81-84. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000348

- Wolf R. The lanolin paradox. Dermatology. 1996;192:198-202. doi:10.1159/000246365

- Lee B, Warshaw E. Lanolin allergy: history, epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. Dermatitis. 2008;19:63-72.

- Miest RY, Yiannias JA, Chang YH, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of lanolin allergy. Dermatitis. 2013;24:119-123. doi:10.1097 /DER.0b013e3182937aa4

- Sangha AM. Dermatological conditions in SKIN OF COLOR-: managing atopic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14(3 Suppl 1):S20-S22.

- Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25:345-355. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000083

- Wakelin SH, Smith H, White IR, et al. A retrospective analysis of contact allergy to lanolin. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:28-31. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2133.2001.04277.x

A 5-month-old male with moderately brown skin that rarely burns and tans profusely presented to the emergency department with a worsening red rash of more than 4 months’ duration. The patient had diffuse erythroderma and eczematous patches and plaques covering 95% of the total body surface area, including lichenified plaques on the arms and elbows, with no signs of infection. He initially presented for his 1-month appointment at the pediatric clinic with scaly patches and plaques on the face and trunk as well as diffuse xerosis. He was prescribed daily oatmeal baths and topical Minerin (Major Pharmaceuticals)—containing water, petrolatum, mineral oil, mineral wax, lanolin alcohol, methylchloroisothiazolinone, and methylisothiazolinone—to be applied to the whole body twice daily. At the patient’s 2-month well visit, symptoms persisted. The patient’s pediatrician increased application of Minerin to 2 to 3 times daily, and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% application 2 to 3 times daily was added.