User login

Patients and Surgeons Diverge on Disclosures

SAN FRANCISCO – Recent surveys of patients and attending surgeons show differing views on disclosures, Dr. Susan Lee Char said at the clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

She and her associates surveyed 353 adult patients at their first postoperative clinic visit and 85 attending surgeons at hospitals affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco. The survey presented a hypothetical case of a patient’s undergoing elective partial hepatectomy and asked respondents to rate the importance of receiving or conveying various items of information on a 6-point Likert scale.

In all, 79% of patients said it’s essential to know if their surgeon would be doing a procedure for the first time on them, but only 55% of attending surgeons felt this was important information to disclose. A total of 63% of patients considered it essential to know the number of times a surgeon had performed a particular procedure and the outcomes in those cases, compared with just 25% and 20% of surgeons, respectively.

"The data suggest that surgeons do have an ethical obligation to disclose volumes and outcomes and if it’s the first time [they’re] doing a procedure," said Dr. Char, a surgical resident at the university who is also a lawyer. "This has possible legal implications."

The main barrier to surgeons’ disclosure may be a practical one, she added. Surgeons often don’t have data on the volumes and outcomes of their procedures.

Patients’ and attending surgeons’ perceptions of the importance of other types of information also differed significantly. A general description of the procedure was rated as important by 65% of patients vs. 58% of surgeons, and technical details of the procedure were important to 48% of patients and 13% of surgeons. Disclosure of risks and benefits of the procedure were deemed essential by 77% and 71% of patients, respectively, compared with 72% and 65% of surgeons, respectively. A total of 41% of patients and 5% of surgeons said the patient should be told the number of times the procedure has been done by other surgeons, and 44% of patients and 20% of surgeons said other surgeons’ outcomes should be disclosed.

A total of 64% of patients and 31% of surgeons believed it was important to discuss any special training by the surgeon doing the procedure. Some 64% of patients said they would want to be informed about the surgeon’s special training for a standard procedure, compared with 68% for a laparoscopic procedure and 71% for a robotic procedure.

Technological innovation made a difference in whether patients deemed certain information essential. Patients scheduled for a laparoscopic or robotic procedure were significantly more likely to want information than those undergoing a standard operation.

In all, 63% of patients said they would want to know the number of times that a standard procedure had been done by their surgeon. That percentage rose to 66% for a laparoscopic procedure and to 68% for a robotic procedure. Outcomes information was considered important by 63% of patients for a standard procedure, 66% for a laparoscopic procedure, and 67% for a robotic procedure. And 24% of patients, compared with 6% of surgeons, said the patient should be told if the surgeon planned to publish an article including the case. Disclosing whether a surgeon is a paid consultant was less important to patients (5%) than to surgeons (40%).

Dr. Char had no conflicts of interest.

This study is an important one for all practicing surgeons. Informed consent is central to the practice of surgery, and disclosure of information is a cornerstone of the consent process. Nevertheless, as Dr. Char’s study so dramatically illustrates, surgeons and patients frequently disagree on which items must be disclosed in order to obtain informed consent.

A few important areas of discrepancy are revealed. For example, patients considered disclosure of how many times a surgeon had performed a specific procedure more important than did surgeons. Similarly, only 55% of surgeons thought it was important to disclose to patients whether they were performing an operation for the first time, whereas 79% of patients said that such information was essential. On the other hand, despite the national movement to disclose financial conflicts of interest, only 5% of patients wanted to know if their surgeon was a paid consultant to industry compared with 40% of surgeons who felt that this is important to disclose.

What conclusions should we draw from these discrepancies between what patients say they want to know and what surgeons say is important to disclose in the informed consent process? Most important, surgeons should realize the difficulties we have in accurately predicting what information will be important to our patients. If we assume that we know how much information our patients want, we will almost certainly guess incorrectly. As a result, a different strategy should be adopted. Surgeons should tailor their disclosure in the consent process to the specific information needs of the individual patient. This can readily be accomplished by asking, "What additional questions do you have?" or "What information do you need in order to feel comfortable consenting to this operation?" If surgeons were to be guided by their patients when tailoring the nature and amount of information they disclose, patients would more likely be satisfied with that disclosure and the consent process would be improved.

Dr. Peter Angelos is an ACS Fellow, professor of surgery, and associate director, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago.

This study is an important one for all practicing surgeons. Informed consent is central to the practice of surgery, and disclosure of information is a cornerstone of the consent process. Nevertheless, as Dr. Char’s study so dramatically illustrates, surgeons and patients frequently disagree on which items must be disclosed in order to obtain informed consent.

A few important areas of discrepancy are revealed. For example, patients considered disclosure of how many times a surgeon had performed a specific procedure more important than did surgeons. Similarly, only 55% of surgeons thought it was important to disclose to patients whether they were performing an operation for the first time, whereas 79% of patients said that such information was essential. On the other hand, despite the national movement to disclose financial conflicts of interest, only 5% of patients wanted to know if their surgeon was a paid consultant to industry compared with 40% of surgeons who felt that this is important to disclose.

What conclusions should we draw from these discrepancies between what patients say they want to know and what surgeons say is important to disclose in the informed consent process? Most important, surgeons should realize the difficulties we have in accurately predicting what information will be important to our patients. If we assume that we know how much information our patients want, we will almost certainly guess incorrectly. As a result, a different strategy should be adopted. Surgeons should tailor their disclosure in the consent process to the specific information needs of the individual patient. This can readily be accomplished by asking, "What additional questions do you have?" or "What information do you need in order to feel comfortable consenting to this operation?" If surgeons were to be guided by their patients when tailoring the nature and amount of information they disclose, patients would more likely be satisfied with that disclosure and the consent process would be improved.

Dr. Peter Angelos is an ACS Fellow, professor of surgery, and associate director, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago.

This study is an important one for all practicing surgeons. Informed consent is central to the practice of surgery, and disclosure of information is a cornerstone of the consent process. Nevertheless, as Dr. Char’s study so dramatically illustrates, surgeons and patients frequently disagree on which items must be disclosed in order to obtain informed consent.

A few important areas of discrepancy are revealed. For example, patients considered disclosure of how many times a surgeon had performed a specific procedure more important than did surgeons. Similarly, only 55% of surgeons thought it was important to disclose to patients whether they were performing an operation for the first time, whereas 79% of patients said that such information was essential. On the other hand, despite the national movement to disclose financial conflicts of interest, only 5% of patients wanted to know if their surgeon was a paid consultant to industry compared with 40% of surgeons who felt that this is important to disclose.

What conclusions should we draw from these discrepancies between what patients say they want to know and what surgeons say is important to disclose in the informed consent process? Most important, surgeons should realize the difficulties we have in accurately predicting what information will be important to our patients. If we assume that we know how much information our patients want, we will almost certainly guess incorrectly. As a result, a different strategy should be adopted. Surgeons should tailor their disclosure in the consent process to the specific information needs of the individual patient. This can readily be accomplished by asking, "What additional questions do you have?" or "What information do you need in order to feel comfortable consenting to this operation?" If surgeons were to be guided by their patients when tailoring the nature and amount of information they disclose, patients would more likely be satisfied with that disclosure and the consent process would be improved.

Dr. Peter Angelos is an ACS Fellow, professor of surgery, and associate director, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago.

SAN FRANCISCO – Recent surveys of patients and attending surgeons show differing views on disclosures, Dr. Susan Lee Char said at the clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

She and her associates surveyed 353 adult patients at their first postoperative clinic visit and 85 attending surgeons at hospitals affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco. The survey presented a hypothetical case of a patient’s undergoing elective partial hepatectomy and asked respondents to rate the importance of receiving or conveying various items of information on a 6-point Likert scale.

In all, 79% of patients said it’s essential to know if their surgeon would be doing a procedure for the first time on them, but only 55% of attending surgeons felt this was important information to disclose. A total of 63% of patients considered it essential to know the number of times a surgeon had performed a particular procedure and the outcomes in those cases, compared with just 25% and 20% of surgeons, respectively.

"The data suggest that surgeons do have an ethical obligation to disclose volumes and outcomes and if it’s the first time [they’re] doing a procedure," said Dr. Char, a surgical resident at the university who is also a lawyer. "This has possible legal implications."

The main barrier to surgeons’ disclosure may be a practical one, she added. Surgeons often don’t have data on the volumes and outcomes of their procedures.

Patients’ and attending surgeons’ perceptions of the importance of other types of information also differed significantly. A general description of the procedure was rated as important by 65% of patients vs. 58% of surgeons, and technical details of the procedure were important to 48% of patients and 13% of surgeons. Disclosure of risks and benefits of the procedure were deemed essential by 77% and 71% of patients, respectively, compared with 72% and 65% of surgeons, respectively. A total of 41% of patients and 5% of surgeons said the patient should be told the number of times the procedure has been done by other surgeons, and 44% of patients and 20% of surgeons said other surgeons’ outcomes should be disclosed.

A total of 64% of patients and 31% of surgeons believed it was important to discuss any special training by the surgeon doing the procedure. Some 64% of patients said they would want to be informed about the surgeon’s special training for a standard procedure, compared with 68% for a laparoscopic procedure and 71% for a robotic procedure.

Technological innovation made a difference in whether patients deemed certain information essential. Patients scheduled for a laparoscopic or robotic procedure were significantly more likely to want information than those undergoing a standard operation.

In all, 63% of patients said they would want to know the number of times that a standard procedure had been done by their surgeon. That percentage rose to 66% for a laparoscopic procedure and to 68% for a robotic procedure. Outcomes information was considered important by 63% of patients for a standard procedure, 66% for a laparoscopic procedure, and 67% for a robotic procedure. And 24% of patients, compared with 6% of surgeons, said the patient should be told if the surgeon planned to publish an article including the case. Disclosing whether a surgeon is a paid consultant was less important to patients (5%) than to surgeons (40%).

Dr. Char had no conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – Recent surveys of patients and attending surgeons show differing views on disclosures, Dr. Susan Lee Char said at the clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

She and her associates surveyed 353 adult patients at their first postoperative clinic visit and 85 attending surgeons at hospitals affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco. The survey presented a hypothetical case of a patient’s undergoing elective partial hepatectomy and asked respondents to rate the importance of receiving or conveying various items of information on a 6-point Likert scale.

In all, 79% of patients said it’s essential to know if their surgeon would be doing a procedure for the first time on them, but only 55% of attending surgeons felt this was important information to disclose. A total of 63% of patients considered it essential to know the number of times a surgeon had performed a particular procedure and the outcomes in those cases, compared with just 25% and 20% of surgeons, respectively.

"The data suggest that surgeons do have an ethical obligation to disclose volumes and outcomes and if it’s the first time [they’re] doing a procedure," said Dr. Char, a surgical resident at the university who is also a lawyer. "This has possible legal implications."

The main barrier to surgeons’ disclosure may be a practical one, she added. Surgeons often don’t have data on the volumes and outcomes of their procedures.

Patients’ and attending surgeons’ perceptions of the importance of other types of information also differed significantly. A general description of the procedure was rated as important by 65% of patients vs. 58% of surgeons, and technical details of the procedure were important to 48% of patients and 13% of surgeons. Disclosure of risks and benefits of the procedure were deemed essential by 77% and 71% of patients, respectively, compared with 72% and 65% of surgeons, respectively. A total of 41% of patients and 5% of surgeons said the patient should be told the number of times the procedure has been done by other surgeons, and 44% of patients and 20% of surgeons said other surgeons’ outcomes should be disclosed.

A total of 64% of patients and 31% of surgeons believed it was important to discuss any special training by the surgeon doing the procedure. Some 64% of patients said they would want to be informed about the surgeon’s special training for a standard procedure, compared with 68% for a laparoscopic procedure and 71% for a robotic procedure.

Technological innovation made a difference in whether patients deemed certain information essential. Patients scheduled for a laparoscopic or robotic procedure were significantly more likely to want information than those undergoing a standard operation.

In all, 63% of patients said they would want to know the number of times that a standard procedure had been done by their surgeon. That percentage rose to 66% for a laparoscopic procedure and to 68% for a robotic procedure. Outcomes information was considered important by 63% of patients for a standard procedure, 66% for a laparoscopic procedure, and 67% for a robotic procedure. And 24% of patients, compared with 6% of surgeons, said the patient should be told if the surgeon planned to publish an article including the case. Disclosing whether a surgeon is a paid consultant was less important to patients (5%) than to surgeons (40%).

Dr. Char had no conflicts of interest.

Major Finding: Only 55% of surgeons believed they should disclose that they would be doing a surgery for the first time on a patient when getting informed consent, compared with 79% of patients.

Data Source: Surveys presenting a hypothetical case to 353 patients at postoperative clinic visits, and to 85 attending surgeons.

Disclosures: Dr. Char said she has no relevant conflicts of interest.

Establishing Acute Pain Service Deemed Worthwhile

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – The University of Louisville has had an acute pain service for nearly a decade, but for many hospitals in the United States this still is a new idea.

"What we’re seeing is the birth of a new modality in treatment" and possibly a new specialty, Dr. Laura Clark said.

An acute pain service (APS) primarily manages pain after traumatic injury or surgery. The basic aspects of an APS include standardization of analgesic techniques, increased pain monitoring and assessment, and the ability to respond to inadequate or excessive doses of analgesics.

Establishing an APS, however, takes a lot of persuasion and education, said Dr. Clark, professor of anesthesiology and director of acute pain and regional anesthesia at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

Hospital administrators must be convinced that an APS can benefit the hospital by increasing patient satisfaction (which is strongly associated with adequate pain relief) and by cutting costs through reducing nausea and vomiting, respiratory depression, the incidence of ileus (and thus the length of hospitalization), and the incidence of chronic pain.

Physicians and pharmacists need to be willing to accept an APS as part of the care team. Many anesthesiologists mistakenly think that a single nerve block that dissipates in 10 hours is sufficient acute pain management, she said. But more than anyone, surgeons need convincing, Dr. Clark said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

Currently, a surgeon must request involvement of the APS and that request must be documented in order for the service to be covered by insurers. "That needs to change," she said.

To get surgeons on board, include them in developing protocols for all analgesic techniques, she suggested.

There are two groups that don’t need convincing about the benefits of an APS – patients and nurses, she said. Still, education of nurses and all staff about the APS is essential. Simply asking nurses to follow written orders is not sufficient, especially for the more advanced pain therapies. Good acute pain care requires a change in culture and attitudes; for example, nurses need to change empty bags of analgesics just as they change other bags of fluids.

Nurses can be certified in pain management, and "I recommend that you have your nurses do that," Dr. Clark said.

The need for better acute pain management has been established by major reports in the United States, England, Australia, Germany, Sweden, and elsewhere. At least eight published studies report that an APS improves pain relief, five studies report a lower incidence of side effects, and three studies suggest that an APS may reduce the incidence of persistent pain after surgery, she said.

One study reported reduced postoperative morbidity and mortality with an APS but noted that "the workload is considerable" (Anesthesia 2006;61:24-8).

A recent study concluded that an APS is "likely" to be cost effective, but the investigators "didn’t even study what we do," Dr. Clark said. Key treatment techniques such as peripheral nerve blocks and epidural patient-controlled analgesia were not included in the study (Anesth. Analg. 2010;111:1042-50). Had it included those, she believes the study would have shown that an APS is very cost effective, she said.

Better studies with hard data are needed, she added.

The service ideally is physician directed but multidisciplinary, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and physical therapists. The most common but least desirable model of an APS in the United States includes a private physician or regionalist who may not do rounds unless called by a surgeon to manage a problem, Dr. Clark said. A second model that may be the most flexible and cost effective for around-the-clock care involves a nurse-led physician consult, in which the nurse makes daily rounds, reports to the physician, and implements therapy based on standard orders and protocols developed by the pain physician and surgeon.

The most common model in academic centers, and Dr. Clark’s favorite, is a physician-led team with a pain management nurse. The team makes rounds and decides on care. The pain physician may or may not be the regionalist. Medical residents are on call for the pain service. The pain nurse is involved in cases before, during, and after surgery and implements advanced pain management techniques, provides consultations, and coordinates with trauma, surgery, and critical care services.

Once you’ve convinced your institution and colleagues to establish an APS, make sure that someone on the APS can be reached by telephone at any hour of every day. Establish "acute pain champions" on every floor and in every area of the hospital, and make sure that at least one champion is available on every shift.

Running an APS can be challenging, but it’s a therapeutic tool that’s worth the effort, she said: "With our twice-a-day rounds, we often hear from the patients that we talk to them more than any other physician. It can be quite rewarding."

Dr. Clark has been a speaker for Covidien and Cadence and an adviser and researcher for Covidien.

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – The University of Louisville has had an acute pain service for nearly a decade, but for many hospitals in the United States this still is a new idea.

"What we’re seeing is the birth of a new modality in treatment" and possibly a new specialty, Dr. Laura Clark said.

An acute pain service (APS) primarily manages pain after traumatic injury or surgery. The basic aspects of an APS include standardization of analgesic techniques, increased pain monitoring and assessment, and the ability to respond to inadequate or excessive doses of analgesics.

Establishing an APS, however, takes a lot of persuasion and education, said Dr. Clark, professor of anesthesiology and director of acute pain and regional anesthesia at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

Hospital administrators must be convinced that an APS can benefit the hospital by increasing patient satisfaction (which is strongly associated with adequate pain relief) and by cutting costs through reducing nausea and vomiting, respiratory depression, the incidence of ileus (and thus the length of hospitalization), and the incidence of chronic pain.

Physicians and pharmacists need to be willing to accept an APS as part of the care team. Many anesthesiologists mistakenly think that a single nerve block that dissipates in 10 hours is sufficient acute pain management, she said. But more than anyone, surgeons need convincing, Dr. Clark said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

Currently, a surgeon must request involvement of the APS and that request must be documented in order for the service to be covered by insurers. "That needs to change," she said.

To get surgeons on board, include them in developing protocols for all analgesic techniques, she suggested.

There are two groups that don’t need convincing about the benefits of an APS – patients and nurses, she said. Still, education of nurses and all staff about the APS is essential. Simply asking nurses to follow written orders is not sufficient, especially for the more advanced pain therapies. Good acute pain care requires a change in culture and attitudes; for example, nurses need to change empty bags of analgesics just as they change other bags of fluids.

Nurses can be certified in pain management, and "I recommend that you have your nurses do that," Dr. Clark said.

The need for better acute pain management has been established by major reports in the United States, England, Australia, Germany, Sweden, and elsewhere. At least eight published studies report that an APS improves pain relief, five studies report a lower incidence of side effects, and three studies suggest that an APS may reduce the incidence of persistent pain after surgery, she said.

One study reported reduced postoperative morbidity and mortality with an APS but noted that "the workload is considerable" (Anesthesia 2006;61:24-8).

A recent study concluded that an APS is "likely" to be cost effective, but the investigators "didn’t even study what we do," Dr. Clark said. Key treatment techniques such as peripheral nerve blocks and epidural patient-controlled analgesia were not included in the study (Anesth. Analg. 2010;111:1042-50). Had it included those, she believes the study would have shown that an APS is very cost effective, she said.

Better studies with hard data are needed, she added.

The service ideally is physician directed but multidisciplinary, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and physical therapists. The most common but least desirable model of an APS in the United States includes a private physician or regionalist who may not do rounds unless called by a surgeon to manage a problem, Dr. Clark said. A second model that may be the most flexible and cost effective for around-the-clock care involves a nurse-led physician consult, in which the nurse makes daily rounds, reports to the physician, and implements therapy based on standard orders and protocols developed by the pain physician and surgeon.

The most common model in academic centers, and Dr. Clark’s favorite, is a physician-led team with a pain management nurse. The team makes rounds and decides on care. The pain physician may or may not be the regionalist. Medical residents are on call for the pain service. The pain nurse is involved in cases before, during, and after surgery and implements advanced pain management techniques, provides consultations, and coordinates with trauma, surgery, and critical care services.

Once you’ve convinced your institution and colleagues to establish an APS, make sure that someone on the APS can be reached by telephone at any hour of every day. Establish "acute pain champions" on every floor and in every area of the hospital, and make sure that at least one champion is available on every shift.

Running an APS can be challenging, but it’s a therapeutic tool that’s worth the effort, she said: "With our twice-a-day rounds, we often hear from the patients that we talk to them more than any other physician. It can be quite rewarding."

Dr. Clark has been a speaker for Covidien and Cadence and an adviser and researcher for Covidien.

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – The University of Louisville has had an acute pain service for nearly a decade, but for many hospitals in the United States this still is a new idea.

"What we’re seeing is the birth of a new modality in treatment" and possibly a new specialty, Dr. Laura Clark said.

An acute pain service (APS) primarily manages pain after traumatic injury or surgery. The basic aspects of an APS include standardization of analgesic techniques, increased pain monitoring and assessment, and the ability to respond to inadequate or excessive doses of analgesics.

Establishing an APS, however, takes a lot of persuasion and education, said Dr. Clark, professor of anesthesiology and director of acute pain and regional anesthesia at the University of Louisville (Ky.).

Hospital administrators must be convinced that an APS can benefit the hospital by increasing patient satisfaction (which is strongly associated with adequate pain relief) and by cutting costs through reducing nausea and vomiting, respiratory depression, the incidence of ileus (and thus the length of hospitalization), and the incidence of chronic pain.

Physicians and pharmacists need to be willing to accept an APS as part of the care team. Many anesthesiologists mistakenly think that a single nerve block that dissipates in 10 hours is sufficient acute pain management, she said. But more than anyone, surgeons need convincing, Dr. Clark said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

Currently, a surgeon must request involvement of the APS and that request must be documented in order for the service to be covered by insurers. "That needs to change," she said.

To get surgeons on board, include them in developing protocols for all analgesic techniques, she suggested.

There are two groups that don’t need convincing about the benefits of an APS – patients and nurses, she said. Still, education of nurses and all staff about the APS is essential. Simply asking nurses to follow written orders is not sufficient, especially for the more advanced pain therapies. Good acute pain care requires a change in culture and attitudes; for example, nurses need to change empty bags of analgesics just as they change other bags of fluids.

Nurses can be certified in pain management, and "I recommend that you have your nurses do that," Dr. Clark said.

The need for better acute pain management has been established by major reports in the United States, England, Australia, Germany, Sweden, and elsewhere. At least eight published studies report that an APS improves pain relief, five studies report a lower incidence of side effects, and three studies suggest that an APS may reduce the incidence of persistent pain after surgery, she said.

One study reported reduced postoperative morbidity and mortality with an APS but noted that "the workload is considerable" (Anesthesia 2006;61:24-8).

A recent study concluded that an APS is "likely" to be cost effective, but the investigators "didn’t even study what we do," Dr. Clark said. Key treatment techniques such as peripheral nerve blocks and epidural patient-controlled analgesia were not included in the study (Anesth. Analg. 2010;111:1042-50). Had it included those, she believes the study would have shown that an APS is very cost effective, she said.

Better studies with hard data are needed, she added.

The service ideally is physician directed but multidisciplinary, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and physical therapists. The most common but least desirable model of an APS in the United States includes a private physician or regionalist who may not do rounds unless called by a surgeon to manage a problem, Dr. Clark said. A second model that may be the most flexible and cost effective for around-the-clock care involves a nurse-led physician consult, in which the nurse makes daily rounds, reports to the physician, and implements therapy based on standard orders and protocols developed by the pain physician and surgeon.

The most common model in academic centers, and Dr. Clark’s favorite, is a physician-led team with a pain management nurse. The team makes rounds and decides on care. The pain physician may or may not be the regionalist. Medical residents are on call for the pain service. The pain nurse is involved in cases before, during, and after surgery and implements advanced pain management techniques, provides consultations, and coordinates with trauma, surgery, and critical care services.

Once you’ve convinced your institution and colleagues to establish an APS, make sure that someone on the APS can be reached by telephone at any hour of every day. Establish "acute pain champions" on every floor and in every area of the hospital, and make sure that at least one champion is available on every shift.

Running an APS can be challenging, but it’s a therapeutic tool that’s worth the effort, she said: "With our twice-a-day rounds, we often hear from the patients that we talk to them more than any other physician. It can be quite rewarding."

Dr. Clark has been a speaker for Covidien and Cadence and an adviser and researcher for Covidien.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PAIN MEDICINE

Side Effects Challenge Opioid Therapy for Acute Pain

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – Balancing pain relief against gastrointestinal side effects of opioid analgesics in treating acute pain is a major challenge, a nationwide survey of nearly 6,000 physicians suggests.

A total of 70% of physicians said they "usually" or "often" prescribe opioid analgesics for patients with moderate to severe acute pain. Alongside that, 63% said they also "usually" or "often" prescribe or recommend treatments to manage opioid-related side effects, especially GI side effects, Dr. Bill H. McCarberg and his associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

The survey also found that 65% of physicians said that patients who receive opioid analgesics for acute pain also take over-the-counter or prescription treatments to manage opioid-related GI side effects. A total of 20% of physicians rated unacceptable GI side effects as the top reason for discontinuing opioid analgesics, and 60% said GI side effects were the top or second-to-the-top reason for discontinuing opioids, reported Dr. McCarberg, a family physician and pain specialist at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego.

The data came from the Physicians Partnering Against Pain survey, which asked 5,982 physicians to identify 10-15 "typical patients who were returning for their first follow-up visits after treatment for moderate to severe acute pain. A majority of respondents (52%) were primary care physicians, 25% were pain specialists, and 23% were other medical specialists.

In all, 55% of physicians ranked unacceptable GI or other side effects as the most common reason patients discontinued opioids. More than 40% of physicians said that patients discontinued opioids, mainly because they believed that their pain had dissipated.

More than 15% of physicians said that they see more than 60 patients with moderate to severe pain in a typical week. More than 20% said they see 31-60 patients per week, more than 35% said they see 16-30 patients per week, and nearly 25% said they see 0-15 patients with moderate to severe pain in a typical week. A majority of physicians (55%) reported that more than 75% of their patients return for a follow-up visit after the initial acute pain treatment.

The participating physicians may not be representative of all U.S. practicing physicians, and there may be some recall bias affecting how well the results represent actual physician behavior.

Despite these limitations, the findings reflect the significant challenges that opioid-related side effects pose for managing moderate to severe acute pain, Dr. McCarberg said.

Janssen Scientific Affairs funded the study and Dr. McCarberg’s associates in the study were Janssen employees. Dr. McCarberg reported having no financial disclosures.

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – Balancing pain relief against gastrointestinal side effects of opioid analgesics in treating acute pain is a major challenge, a nationwide survey of nearly 6,000 physicians suggests.

A total of 70% of physicians said they "usually" or "often" prescribe opioid analgesics for patients with moderate to severe acute pain. Alongside that, 63% said they also "usually" or "often" prescribe or recommend treatments to manage opioid-related side effects, especially GI side effects, Dr. Bill H. McCarberg and his associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

The survey also found that 65% of physicians said that patients who receive opioid analgesics for acute pain also take over-the-counter or prescription treatments to manage opioid-related GI side effects. A total of 20% of physicians rated unacceptable GI side effects as the top reason for discontinuing opioid analgesics, and 60% said GI side effects were the top or second-to-the-top reason for discontinuing opioids, reported Dr. McCarberg, a family physician and pain specialist at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego.

The data came from the Physicians Partnering Against Pain survey, which asked 5,982 physicians to identify 10-15 "typical patients who were returning for their first follow-up visits after treatment for moderate to severe acute pain. A majority of respondents (52%) were primary care physicians, 25% were pain specialists, and 23% were other medical specialists.

In all, 55% of physicians ranked unacceptable GI or other side effects as the most common reason patients discontinued opioids. More than 40% of physicians said that patients discontinued opioids, mainly because they believed that their pain had dissipated.

More than 15% of physicians said that they see more than 60 patients with moderate to severe pain in a typical week. More than 20% said they see 31-60 patients per week, more than 35% said they see 16-30 patients per week, and nearly 25% said they see 0-15 patients with moderate to severe pain in a typical week. A majority of physicians (55%) reported that more than 75% of their patients return for a follow-up visit after the initial acute pain treatment.

The participating physicians may not be representative of all U.S. practicing physicians, and there may be some recall bias affecting how well the results represent actual physician behavior.

Despite these limitations, the findings reflect the significant challenges that opioid-related side effects pose for managing moderate to severe acute pain, Dr. McCarberg said.

Janssen Scientific Affairs funded the study and Dr. McCarberg’s associates in the study were Janssen employees. Dr. McCarberg reported having no financial disclosures.

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – Balancing pain relief against gastrointestinal side effects of opioid analgesics in treating acute pain is a major challenge, a nationwide survey of nearly 6,000 physicians suggests.

A total of 70% of physicians said they "usually" or "often" prescribe opioid analgesics for patients with moderate to severe acute pain. Alongside that, 63% said they also "usually" or "often" prescribe or recommend treatments to manage opioid-related side effects, especially GI side effects, Dr. Bill H. McCarberg and his associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

The survey also found that 65% of physicians said that patients who receive opioid analgesics for acute pain also take over-the-counter or prescription treatments to manage opioid-related GI side effects. A total of 20% of physicians rated unacceptable GI side effects as the top reason for discontinuing opioid analgesics, and 60% said GI side effects were the top or second-to-the-top reason for discontinuing opioids, reported Dr. McCarberg, a family physician and pain specialist at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego.

The data came from the Physicians Partnering Against Pain survey, which asked 5,982 physicians to identify 10-15 "typical patients who were returning for their first follow-up visits after treatment for moderate to severe acute pain. A majority of respondents (52%) were primary care physicians, 25% were pain specialists, and 23% were other medical specialists.

In all, 55% of physicians ranked unacceptable GI or other side effects as the most common reason patients discontinued opioids. More than 40% of physicians said that patients discontinued opioids, mainly because they believed that their pain had dissipated.

More than 15% of physicians said that they see more than 60 patients with moderate to severe pain in a typical week. More than 20% said they see 31-60 patients per week, more than 35% said they see 16-30 patients per week, and nearly 25% said they see 0-15 patients with moderate to severe pain in a typical week. A majority of physicians (55%) reported that more than 75% of their patients return for a follow-up visit after the initial acute pain treatment.

The participating physicians may not be representative of all U.S. practicing physicians, and there may be some recall bias affecting how well the results represent actual physician behavior.

Despite these limitations, the findings reflect the significant challenges that opioid-related side effects pose for managing moderate to severe acute pain, Dr. McCarberg said.

Janssen Scientific Affairs funded the study and Dr. McCarberg’s associates in the study were Janssen employees. Dr. McCarberg reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PAIN MEDICINE

Major Finding: In all, 70% of physicians said that they "usually" or "often" prescribe opioid analgesics for patients with moderate to severe pain, and 63% prescribe or recommend treatments to manage opioid-related side effects.

Data Source: The nationwide survey queried 5,982 physicians.

Disclosures: Janssen Scientific Affairs funded the study, and Dr. McCarberg’s associates in the study were Janssen employees. Dr. McCarberg reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Long-Acting Opioids May Trigger Hypogonadism

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – Low testosterone levels were nearly five times more likely in men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids, compared with equipotent short-acting or immediate-release formulations, judging from the findings of a study of 81 men on daily opioids for chronic pain.

Neither the age of the patient nor the total daily dose of opioid significantly affected the risk of hypogonadism, Dr. Andrea Rubenstein reported in her award-winning poster and a plenary presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

With her associates, Dr. Rubenstein reviewed records on the morning measurements of total testosterone levels in men who were on a stable dose of an opioid for at least 3 months and who had no history of hypogonadism. In all, 46 of the 81 men had total testosterone levels below 25 ng/dl (57%), consistent with published reports of a high rate of hypogonadism in men on chronic opioid therapy ranging from 54% to 86%.

Previous studies, however, evaluated only men on sustained-release or intrathecal formulations and could not identify what aspect of opioid use may be contributing to hypogonadism.

The current study found that 34 of 46 men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids had low total testosterone levels (74%), compared with 12 of 35 men on short-acting or immediate-release opioids (34%), a significant difference, said Dr. Rubenstein, an anesthesiologist and pain specialist at Kaiser Permanente Medical Group, Santa Rosa, Calif.

After adjusting for the effects of dosage and body mass index (BMI), men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids were 4.8 times more likely to have low testosterone levels, compared with men on short-acting or immediate-release formulations.

Higher BMI had a small but significant association, increasing the risk for hypogonadism by 13%.

Opioid-related androgen deficiency has been documented in one fashion or another since the 1970s, and appears to come on quickly, within days or weeks of starting chronic opioid therapy, she said.

"This phenomenon is not new, even though it’s kind of a hot topic this year," Dr. Rubenstein said.

For the past 20 years, the trend has been to put more and more patients on long-acting opioids because these were believed to be safer than short-acting formulations. If the association between hypogonadism and long-acting opioids holds up in further studies, "it will be the first evidence of a difference in safety, though not in the direction we had thought," she said.

Dr. Steven Linder of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif., commented on the study in an interview at the poster presentation. The V.A. is seeing a large number of young veterans with spinal and other injuries who are on long-term opioids, and often these patients are not screened for hypogonadism. Dr. Rubenstein’s study is an important reminder to check testosterone levels in men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids, he said.

If unrecognized and untreated, hypogonadism can lead to osteoporosis, low libido, lower function and mood, insulin resistance, increased pain, and obesity. Often, these are managed with other medications that contribute side effects, Dr. Rubenstein said.

"The last thing we need in a guy on 40 mg of methadone for back pain is to get osteoporosis of the spine," she said.

Patients in the study included 25 on hydrocodone, 8 on continuous-release oxycodone, 10 on immediate-release oxycodone, 12 on continuous-release morphine, 4 on the fentanyl patch, 14 on methadone, and 8 on off-label sublingual buprenorphine. (Only the patch form of buprenorphine is approved to treat pain.)

The study was limited by its small size, "but in the opioid literature, 81 is a nice number," she said. The study also is limited by its retrospective design, potential bias if the symptoms of hypogonadism played a role in the initial referral, and questionable generalizability if the men at this tertiary-care pain clinic are not representative of men with chronic pain in the general population.

The investigators next will repeat the study on a much larger sample of patients, and if the association is replicated, will design a prospective study to see if changing opioid therapy modifies the risk for hypogonadism. The findings of the current study are too preliminary to generate recommendations, she said.

The current study excluded patients with a history of cancer, HIV, or endocrine disease other than hypothyroidism.

Dr. Rubenstein and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – Low testosterone levels were nearly five times more likely in men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids, compared with equipotent short-acting or immediate-release formulations, judging from the findings of a study of 81 men on daily opioids for chronic pain.

Neither the age of the patient nor the total daily dose of opioid significantly affected the risk of hypogonadism, Dr. Andrea Rubenstein reported in her award-winning poster and a plenary presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

With her associates, Dr. Rubenstein reviewed records on the morning measurements of total testosterone levels in men who were on a stable dose of an opioid for at least 3 months and who had no history of hypogonadism. In all, 46 of the 81 men had total testosterone levels below 25 ng/dl (57%), consistent with published reports of a high rate of hypogonadism in men on chronic opioid therapy ranging from 54% to 86%.

Previous studies, however, evaluated only men on sustained-release or intrathecal formulations and could not identify what aspect of opioid use may be contributing to hypogonadism.

The current study found that 34 of 46 men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids had low total testosterone levels (74%), compared with 12 of 35 men on short-acting or immediate-release opioids (34%), a significant difference, said Dr. Rubenstein, an anesthesiologist and pain specialist at Kaiser Permanente Medical Group, Santa Rosa, Calif.

After adjusting for the effects of dosage and body mass index (BMI), men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids were 4.8 times more likely to have low testosterone levels, compared with men on short-acting or immediate-release formulations.

Higher BMI had a small but significant association, increasing the risk for hypogonadism by 13%.

Opioid-related androgen deficiency has been documented in one fashion or another since the 1970s, and appears to come on quickly, within days or weeks of starting chronic opioid therapy, she said.

"This phenomenon is not new, even though it’s kind of a hot topic this year," Dr. Rubenstein said.

For the past 20 years, the trend has been to put more and more patients on long-acting opioids because these were believed to be safer than short-acting formulations. If the association between hypogonadism and long-acting opioids holds up in further studies, "it will be the first evidence of a difference in safety, though not in the direction we had thought," she said.

Dr. Steven Linder of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif., commented on the study in an interview at the poster presentation. The V.A. is seeing a large number of young veterans with spinal and other injuries who are on long-term opioids, and often these patients are not screened for hypogonadism. Dr. Rubenstein’s study is an important reminder to check testosterone levels in men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids, he said.

If unrecognized and untreated, hypogonadism can lead to osteoporosis, low libido, lower function and mood, insulin resistance, increased pain, and obesity. Often, these are managed with other medications that contribute side effects, Dr. Rubenstein said.

"The last thing we need in a guy on 40 mg of methadone for back pain is to get osteoporosis of the spine," she said.

Patients in the study included 25 on hydrocodone, 8 on continuous-release oxycodone, 10 on immediate-release oxycodone, 12 on continuous-release morphine, 4 on the fentanyl patch, 14 on methadone, and 8 on off-label sublingual buprenorphine. (Only the patch form of buprenorphine is approved to treat pain.)

The study was limited by its small size, "but in the opioid literature, 81 is a nice number," she said. The study also is limited by its retrospective design, potential bias if the symptoms of hypogonadism played a role in the initial referral, and questionable generalizability if the men at this tertiary-care pain clinic are not representative of men with chronic pain in the general population.

The investigators next will repeat the study on a much larger sample of patients, and if the association is replicated, will design a prospective study to see if changing opioid therapy modifies the risk for hypogonadism. The findings of the current study are too preliminary to generate recommendations, she said.

The current study excluded patients with a history of cancer, HIV, or endocrine disease other than hypothyroidism.

Dr. Rubenstein and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – Low testosterone levels were nearly five times more likely in men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids, compared with equipotent short-acting or immediate-release formulations, judging from the findings of a study of 81 men on daily opioids for chronic pain.

Neither the age of the patient nor the total daily dose of opioid significantly affected the risk of hypogonadism, Dr. Andrea Rubenstein reported in her award-winning poster and a plenary presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

With her associates, Dr. Rubenstein reviewed records on the morning measurements of total testosterone levels in men who were on a stable dose of an opioid for at least 3 months and who had no history of hypogonadism. In all, 46 of the 81 men had total testosterone levels below 25 ng/dl (57%), consistent with published reports of a high rate of hypogonadism in men on chronic opioid therapy ranging from 54% to 86%.

Previous studies, however, evaluated only men on sustained-release or intrathecal formulations and could not identify what aspect of opioid use may be contributing to hypogonadism.

The current study found that 34 of 46 men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids had low total testosterone levels (74%), compared with 12 of 35 men on short-acting or immediate-release opioids (34%), a significant difference, said Dr. Rubenstein, an anesthesiologist and pain specialist at Kaiser Permanente Medical Group, Santa Rosa, Calif.

After adjusting for the effects of dosage and body mass index (BMI), men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids were 4.8 times more likely to have low testosterone levels, compared with men on short-acting or immediate-release formulations.

Higher BMI had a small but significant association, increasing the risk for hypogonadism by 13%.

Opioid-related androgen deficiency has been documented in one fashion or another since the 1970s, and appears to come on quickly, within days or weeks of starting chronic opioid therapy, she said.

"This phenomenon is not new, even though it’s kind of a hot topic this year," Dr. Rubenstein said.

For the past 20 years, the trend has been to put more and more patients on long-acting opioids because these were believed to be safer than short-acting formulations. If the association between hypogonadism and long-acting opioids holds up in further studies, "it will be the first evidence of a difference in safety, though not in the direction we had thought," she said.

Dr. Steven Linder of the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif., commented on the study in an interview at the poster presentation. The V.A. is seeing a large number of young veterans with spinal and other injuries who are on long-term opioids, and often these patients are not screened for hypogonadism. Dr. Rubenstein’s study is an important reminder to check testosterone levels in men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids, he said.

If unrecognized and untreated, hypogonadism can lead to osteoporosis, low libido, lower function and mood, insulin resistance, increased pain, and obesity. Often, these are managed with other medications that contribute side effects, Dr. Rubenstein said.

"The last thing we need in a guy on 40 mg of methadone for back pain is to get osteoporosis of the spine," she said.

Patients in the study included 25 on hydrocodone, 8 on continuous-release oxycodone, 10 on immediate-release oxycodone, 12 on continuous-release morphine, 4 on the fentanyl patch, 14 on methadone, and 8 on off-label sublingual buprenorphine. (Only the patch form of buprenorphine is approved to treat pain.)

The study was limited by its small size, "but in the opioid literature, 81 is a nice number," she said. The study also is limited by its retrospective design, potential bias if the symptoms of hypogonadism played a role in the initial referral, and questionable generalizability if the men at this tertiary-care pain clinic are not representative of men with chronic pain in the general population.

The investigators next will repeat the study on a much larger sample of patients, and if the association is replicated, will design a prospective study to see if changing opioid therapy modifies the risk for hypogonadism. The findings of the current study are too preliminary to generate recommendations, she said.

The current study excluded patients with a history of cancer, HIV, or endocrine disease other than hypothyroidism.

Dr. Rubenstein and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PAIN MEDICINE

Major Finding: Tests found low testosterone levels in 74% of men on long-acting or sustained-release opioids, compared with 34% of men on equipotent short-acting or immediate-release opioids.

Data Source: The review included records on 81 men treated with daily opioids for chronic pain at one institution.

Disclosures: Dr. Rubenstein and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

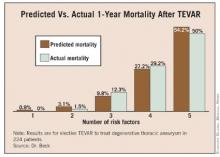

Risk Factors Predict 1-Year Mortality After Elective TEVAR

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A new model for predicting 1-year survival after elective endovascular repair of degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysm suggests that the risks outweigh potential benefits of the procedure in some older patients with multiple comorbidities.

For patients aged 70 years or older who have multiple comorbidities, there is a very high risk of death in the year following thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (TEVAR), so it may be best to wait until the aneurysm is large enough that the risk from not doing TEVAR outweighs the risk of performing the procedure, according to Dr. Adam W. Beck.

Dr. Beck, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his associates analyzed data from a prospective registry of all 526 consecutive TEVARs performed on patients with intact degenerative, asymptomatic thoracic aneurysms at the university between 2000 and 2010. After excluding urgent or emergent cases, the researchers used data from 224 patients who underwent elective TEVAR to identify predictors of death within a year of TEVAR, and compared predictions to survival data from the Social Security Death Index.

Overall, 3% of patients died within 30 days of TEVAR, and 15% died within 1 year – rates that are comparable to those of many studies reported in the medical literature, Dr. Beck said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

In a multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality, being at least 70 years old conferred nearly a sixfold increase in the predicted 1-year risk of death (hazard ratio, 5.8). Patients who had an adjunctive procedure at the time of TEVAR, such as brachiocephalic/visceral stent placement or concomitant visceral debranching procedures, were 4.5 times more likely to die within a year than were patients without an adjunctive procedure.

The predicted risk of death at 1 year was 3 times higher in patients with peripheral vascular occlusive disease and 2.4 times higher in patients with coronary artery disease than in patients without those diseases. All of these associations were statistically significant. The presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease showed a nonsignificant trend toward a 1.9-fold higher risk of death at 1 year (P = .06).

Having a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia appeared to be protective, because it was significantly associated with a 60% decrease in the risk of death at 1 year after TEVAR. When the risk prediction model was created, the lack of a history of hyperlipidemia was considered to be a risk factor.

The risk of death at 1 year rose as the number of significant risk factors increased, and predictive risk correlated well with actual mortality data, Dr. Beck said.

In general, aneurysm diameter was larger in patients with more risk factors, and the risk of death at 1 year increased with aneurysm size and number of risk factors, he added.

The risk of rupture, as reported in the previous literature, is approximately 2% for thoracic aortic aneurysms measuring 5.5 cm in diameter, 10% for aneurysms with a diameter of 6.5 cm, 15% for those measuring 7 cm in diameter, and 45% for aneurysms with a diameter of 8 cm.

When the risk of 1-year mortality is plotted against the number of risk factors, it appears that TEVAR should be delayed in patients with three or more risk factors until their aneurysm diameter is greater than the usual 6-cm threshold commonly used to justify the risk of TEVAR, Dr. Beck said.

"This is an important contribution to our literature," said Dr. Hazim J. Safi, a discussant at the meeting. "Most of us implicitly, when we decide how to manage these patients, would categorize the patient by presumed risk," said Dr. Safi, professor and chair of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at the University of Texas, Houston. "I congratulate the authors for quantifying the relationship between the risk factors and mortality rate."

Usually, surgeons discuss the annual risk of thoracic aneurysm rupture and compare this with the 30-day operative mortality risk when advising patients who are considering TEVAR, Dr. Beck said. To adequately assess the success of aneurysm repair, however, longer survival should be considered, he said.

"It’s important to note that only 21% of deaths within 1 year of repair occurred within 30 days after the procedure, underscoring the importance of looking beyond the first 30 days to determine the benefit of therapy," Dr. Beck said. Even for the groups with multiple risk factors who are at very high risk, the majority of deaths occurred outside the 30-day window.

The risk prediction model should help clinicians select patients who would benefit most from early TEVAR, and delay TEVAR in patients who might be better managed nonoperatively.

To evaluate whether surgeons at his institution were accounting for higher-risk patients, Dr. Beck and his associates performed a secondary analysis. As the number of risk factors for death within 1 year of TEVAR increased, so did the aneurysm diameter at which patients underwent repair. This suggests that surgeons were taking into account risk factors, at least to some extent, in deciding when to operate on these patients.

Patients in the study had a mean age of 61 years, and 63% were male. The average aneurysm diameter was 6.25 cm. At the time of treatment, 38% of patients had coronary artery disease, 28% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 12% had peripheral vascular occlusive disease. Nine percent of patients underwent an intraoperative adjunctive procedure.

Among other comorbidities, 85% had hypertension, 51% had dyslipidemia, 14% had diabetes, 11% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 7% had heart failure.

Eighty percent of patients were taking antiplatelet medications, 55% were on statins, and 67% were considered to be in American Society of Anesthesiologists classification 4.

Dr. Beck reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A new model for predicting 1-year survival after elective endovascular repair of degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysm suggests that the risks outweigh potential benefits of the procedure in some older patients with multiple comorbidities.

For patients aged 70 years or older who have multiple comorbidities, there is a very high risk of death in the year following thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (TEVAR), so it may be best to wait until the aneurysm is large enough that the risk from not doing TEVAR outweighs the risk of performing the procedure, according to Dr. Adam W. Beck.

Dr. Beck, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his associates analyzed data from a prospective registry of all 526 consecutive TEVARs performed on patients with intact degenerative, asymptomatic thoracic aneurysms at the university between 2000 and 2010. After excluding urgent or emergent cases, the researchers used data from 224 patients who underwent elective TEVAR to identify predictors of death within a year of TEVAR, and compared predictions to survival data from the Social Security Death Index.

Overall, 3% of patients died within 30 days of TEVAR, and 15% died within 1 year – rates that are comparable to those of many studies reported in the medical literature, Dr. Beck said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

In a multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality, being at least 70 years old conferred nearly a sixfold increase in the predicted 1-year risk of death (hazard ratio, 5.8). Patients who had an adjunctive procedure at the time of TEVAR, such as brachiocephalic/visceral stent placement or concomitant visceral debranching procedures, were 4.5 times more likely to die within a year than were patients without an adjunctive procedure.

The predicted risk of death at 1 year was 3 times higher in patients with peripheral vascular occlusive disease and 2.4 times higher in patients with coronary artery disease than in patients without those diseases. All of these associations were statistically significant. The presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease showed a nonsignificant trend toward a 1.9-fold higher risk of death at 1 year (P = .06).

Having a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia appeared to be protective, because it was significantly associated with a 60% decrease in the risk of death at 1 year after TEVAR. When the risk prediction model was created, the lack of a history of hyperlipidemia was considered to be a risk factor.

The risk of death at 1 year rose as the number of significant risk factors increased, and predictive risk correlated well with actual mortality data, Dr. Beck said.

In general, aneurysm diameter was larger in patients with more risk factors, and the risk of death at 1 year increased with aneurysm size and number of risk factors, he added.

The risk of rupture, as reported in the previous literature, is approximately 2% for thoracic aortic aneurysms measuring 5.5 cm in diameter, 10% for aneurysms with a diameter of 6.5 cm, 15% for those measuring 7 cm in diameter, and 45% for aneurysms with a diameter of 8 cm.

When the risk of 1-year mortality is plotted against the number of risk factors, it appears that TEVAR should be delayed in patients with three or more risk factors until their aneurysm diameter is greater than the usual 6-cm threshold commonly used to justify the risk of TEVAR, Dr. Beck said.

"This is an important contribution to our literature," said Dr. Hazim J. Safi, a discussant at the meeting. "Most of us implicitly, when we decide how to manage these patients, would categorize the patient by presumed risk," said Dr. Safi, professor and chair of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at the University of Texas, Houston. "I congratulate the authors for quantifying the relationship between the risk factors and mortality rate."

Usually, surgeons discuss the annual risk of thoracic aneurysm rupture and compare this with the 30-day operative mortality risk when advising patients who are considering TEVAR, Dr. Beck said. To adequately assess the success of aneurysm repair, however, longer survival should be considered, he said.

"It’s important to note that only 21% of deaths within 1 year of repair occurred within 30 days after the procedure, underscoring the importance of looking beyond the first 30 days to determine the benefit of therapy," Dr. Beck said. Even for the groups with multiple risk factors who are at very high risk, the majority of deaths occurred outside the 30-day window.

The risk prediction model should help clinicians select patients who would benefit most from early TEVAR, and delay TEVAR in patients who might be better managed nonoperatively.

To evaluate whether surgeons at his institution were accounting for higher-risk patients, Dr. Beck and his associates performed a secondary analysis. As the number of risk factors for death within 1 year of TEVAR increased, so did the aneurysm diameter at which patients underwent repair. This suggests that surgeons were taking into account risk factors, at least to some extent, in deciding when to operate on these patients.

Patients in the study had a mean age of 61 years, and 63% were male. The average aneurysm diameter was 6.25 cm. At the time of treatment, 38% of patients had coronary artery disease, 28% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 12% had peripheral vascular occlusive disease. Nine percent of patients underwent an intraoperative adjunctive procedure.

Among other comorbidities, 85% had hypertension, 51% had dyslipidemia, 14% had diabetes, 11% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 7% had heart failure.

Eighty percent of patients were taking antiplatelet medications, 55% were on statins, and 67% were considered to be in American Society of Anesthesiologists classification 4.

Dr. Beck reported having no financial disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A new model for predicting 1-year survival after elective endovascular repair of degenerative thoracic aortic aneurysm suggests that the risks outweigh potential benefits of the procedure in some older patients with multiple comorbidities.

For patients aged 70 years or older who have multiple comorbidities, there is a very high risk of death in the year following thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (TEVAR), so it may be best to wait until the aneurysm is large enough that the risk from not doing TEVAR outweighs the risk of performing the procedure, according to Dr. Adam W. Beck.

Dr. Beck, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and his associates analyzed data from a prospective registry of all 526 consecutive TEVARs performed on patients with intact degenerative, asymptomatic thoracic aneurysms at the university between 2000 and 2010. After excluding urgent or emergent cases, the researchers used data from 224 patients who underwent elective TEVAR to identify predictors of death within a year of TEVAR, and compared predictions to survival data from the Social Security Death Index.

Overall, 3% of patients died within 30 days of TEVAR, and 15% died within 1 year – rates that are comparable to those of many studies reported in the medical literature, Dr. Beck said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

In a multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality, being at least 70 years old conferred nearly a sixfold increase in the predicted 1-year risk of death (hazard ratio, 5.8). Patients who had an adjunctive procedure at the time of TEVAR, such as brachiocephalic/visceral stent placement or concomitant visceral debranching procedures, were 4.5 times more likely to die within a year than were patients without an adjunctive procedure.

The predicted risk of death at 1 year was 3 times higher in patients with peripheral vascular occlusive disease and 2.4 times higher in patients with coronary artery disease than in patients without those diseases. All of these associations were statistically significant. The presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease showed a nonsignificant trend toward a 1.9-fold higher risk of death at 1 year (P = .06).

Having a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia appeared to be protective, because it was significantly associated with a 60% decrease in the risk of death at 1 year after TEVAR. When the risk prediction model was created, the lack of a history of hyperlipidemia was considered to be a risk factor.

The risk of death at 1 year rose as the number of significant risk factors increased, and predictive risk correlated well with actual mortality data, Dr. Beck said.

In general, aneurysm diameter was larger in patients with more risk factors, and the risk of death at 1 year increased with aneurysm size and number of risk factors, he added.

The risk of rupture, as reported in the previous literature, is approximately 2% for thoracic aortic aneurysms measuring 5.5 cm in diameter, 10% for aneurysms with a diameter of 6.5 cm, 15% for those measuring 7 cm in diameter, and 45% for aneurysms with a diameter of 8 cm.

When the risk of 1-year mortality is plotted against the number of risk factors, it appears that TEVAR should be delayed in patients with three or more risk factors until their aneurysm diameter is greater than the usual 6-cm threshold commonly used to justify the risk of TEVAR, Dr. Beck said.

"This is an important contribution to our literature," said Dr. Hazim J. Safi, a discussant at the meeting. "Most of us implicitly, when we decide how to manage these patients, would categorize the patient by presumed risk," said Dr. Safi, professor and chair of cardiovascular and thoracic surgery at the University of Texas, Houston. "I congratulate the authors for quantifying the relationship between the risk factors and mortality rate."

Usually, surgeons discuss the annual risk of thoracic aneurysm rupture and compare this with the 30-day operative mortality risk when advising patients who are considering TEVAR, Dr. Beck said. To adequately assess the success of aneurysm repair, however, longer survival should be considered, he said.

"It’s important to note that only 21% of deaths within 1 year of repair occurred within 30 days after the procedure, underscoring the importance of looking beyond the first 30 days to determine the benefit of therapy," Dr. Beck said. Even for the groups with multiple risk factors who are at very high risk, the majority of deaths occurred outside the 30-day window.

The risk prediction model should help clinicians select patients who would benefit most from early TEVAR, and delay TEVAR in patients who might be better managed nonoperatively.

To evaluate whether surgeons at his institution were accounting for higher-risk patients, Dr. Beck and his associates performed a secondary analysis. As the number of risk factors for death within 1 year of TEVAR increased, so did the aneurysm diameter at which patients underwent repair. This suggests that surgeons were taking into account risk factors, at least to some extent, in deciding when to operate on these patients.

Patients in the study had a mean age of 61 years, and 63% were male. The average aneurysm diameter was 6.25 cm. At the time of treatment, 38% of patients had coronary artery disease, 28% had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 12% had peripheral vascular occlusive disease. Nine percent of patients underwent an intraoperative adjunctive procedure.

Among other comorbidities, 85% had hypertension, 51% had dyslipidemia, 14% had diabetes, 11% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 7% had heart failure.

Eighty percent of patients were taking antiplatelet medications, 55% were on statins, and 67% were considered to be in American Society of Anesthesiologists classification 4.

Dr. Beck reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN ASSOCIATION FOR VASCULAR SURGERY

Off-label Low-Dose Naltrexone Reduced Fibromyalgia Pain

PALM SPRINGS, CALIF. – Off-label use of daily low-dose naltrexone hydrochloride reduced fibromyalgia pain severity by an average of 48%, compared with a 27% pain reduction on placebo in a double-blind crossover trial in 28 women.

"These are statistically significant results, and I think they are also clinically significant," said Jarred Younger, Ph.D., at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

Tolerability ratings of a regimen of 4.5 mg daily of naltrexone and placebo were statistically equivalent, with scores of 89 (of a possible 100, which represented perfectly tolerated treatment) for both naltrexone and placebo. Side effects associated with use of naltrexone were mild and transient, with significantly more patients reporting vivid dreams (37%) and headaches (16%) on the drug compared with placebo (13% and 3%, respectively).

Low-dose naltrexone, an opioid agonist, is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration and must be custom compounded, but the drug is generic and costs less than $40 per month, said Dr. Younger, director of the adult and pediatric pain laboratory at Stanford (Calif.) University.

"We know it’s cheap, and we know it’s easy to get ahold of," he said.

The 22-week study included women aged 23-65 years living near Stanford who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology’s 1990 criteria for fibromyalgia, including having 11 of 18 tender points. They had had fibromyalgia for a mean of 12 years. Patients were allowed to continue taking their medications as normal, with the exclusion of opioid analgesics.

After a 2-week run-in period, patients were randomized to either 12 weeks of naltrexone or 4 weeks of placebo, taken daily with or without food or water approximately 1 hour before bedtime, in the form of an opaque gelatin capsule with microcrystalline cellulose filler and noncaloric sweetener. The treatment groups then switched to the other regimen for a total of 16 weeks of treatment or placebo, ending with a 4-week follow-up period.

Patients daily rated their pain, fatigue, and other symptoms on a handheld computer; they were assessed every 2 weeks in the laboratory for side effects and were given a new bottle of capsules. Investigators calculated the mean reduction in symptom severity based on measurements in the final 3 days on the drug or placebo.

Three other patients (for a total of 31) were randomized in the study but were excluded from the final analysis, two of them because they stopped taking the capsules.

"Global impression of change" ratings by 30 patients showed that after 12 weeks on naltrexone, 13% reported that their pain was very much improved, 37% said it was much improved, 20% reported minimal improvement, 20% said there was no change in pain, and 10% said pain was minimally worse.

By the end of the naltrexone phase, 57% of patients reported a 30% or greater reduction in pain, Dr. Younger and his associates reported.

Fatigue and sleep quality were not significantly improved on naltrexone, compared with placebo. Patients were not able to guess accurately whether they were receiving the drug or placebo.

The findings confirm results of a 10-patient pilot study by the same investigators (Pain Med. 2009;10:663-72). "We now have two studies" suggesting that low-dose naltrexone reduces the severity of fibromyalgia pain, he said.

Low-dose naltrexone deserves a larger, parallel-group, randomized, controlled trial to further confirm the results in a larger cohort, he added.

Naltrexone is microglia moderator, and the investigators hypothesized that this may be the mechanism of action in reducing fibromyalgia pain. Abnormal functioning of microglia may cause the central sensitivity seen in fibromyalgia and the subsequent overproduction of proinflammatory factors. In-vitro and animal studies have shown that naltrexone reduces microglia hyperexcitability, suppressing the production of proinflammatory cytokines, reducing pain, and serving a neuroprotective function, he said.

Dr. Younger said that future studies also should assess other potential microglia modulators, including ibudilast and 3-hydroxymorphinan. Fluorocitrate, minocycline, and dextromethorphan also are microglia modulators.