User login

Hemorrhagic Crusted Papule on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Self-healing Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Histopathologic examination showed an infiltrate of mononuclear cells with indented nuclei admixed with a variable dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated cells that were strongly positive for CD1a (Figure, A) and langerin (Figure, B) antigens as well as S-100 protein (Figure, C), which was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

Histiocytoses are a heterogeneous group of disorders in which the infiltrating cells belong to the mononuclear phagocyte system.1,2 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is the most common dendritic cell-related histiocytosis, occurring in approximately 5 per 1 million children annually, giving it an incidence comparable to pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma and acute myeloid leukemia.1,2

Historically, there has been much debate about the pathogenesis of the disease.2 Until recently it was unknown whether LCH was primarily a neoplastic or an inflammatory disorder. Although the condition initially was thought to have a reactive etiology,1 more recent evidence suggests a clonal neoplastic process. Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions are clonal and display malignancy-associated mechanisms such as immune evasion. Genome sequencing has revealed several mutations in precursor myeloid cells that result in the common downstream hyperactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway that regulates cell proliferation and differentiation.1

Langerhans cell histiocytosis displays a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes, which historically were subclassified as eosinophilic granulomas (localized lesions in bone), Hand-Schüller-Christian disease (multiple organ involvement with the classic triad of skull defects, diabetes insipidus, and exophthalmos), and Letterer-Siwe disease (visceral lesions involving multiple organs).3 However, in 1997 the Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society redefined LCH as single-system single site (SS-s) LCH, single-system multisite LCH, and multisystem LCH.4

In SS-s LCH, the most common site is bone (82%), followed by the skin (12%).5 Skin SS-s LCH classically presents as multiple skin lesions at birth without systemic manifestations; the lesions spontaneously involute within a few months.6 Less commonly, skin SS-s LCH can present as a single lesion. Berger et al7 described 4 neonates with unilesional skin SS-s LCH. Since then, more than 30 cases have been reported in the literature,8 and we report herein another unilesional self-healing LCH.

The morphology of skin lesions in self-healing LCH is highly variable, with the most common being multiple erythematous crusted papules (50%), followed by eczematous scaly lesions resembling seborrheic dermatitis in intertriginous areas (37.5%).3,6 Unilesional self-healing LCH typically presents as an ulcerated or crusted nodule or papule on the trunk. This variability results in a large differential diagnosis. Self-healing LCH is easily mistaken for infectious processes including neonatal herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infection.9 Often, the dermatology department is consulted to rule out LCH when the asymptomatic neonate does not respond to parenteral acyclovir.

Less commonly, the magenta-colored papulonodules of self-healing LCH can mimic blueberry muffin rash and mandate a workup for intrauterine infections, especially cytomegalovirus, rubella, and blood dyscrasia.10 Other noninfectious processes in the differential of self-healing LCH include congenital infantile hemangioma, neonatal lupus erythematosus, seborrheic dermatitis (cradle cap), pyogenic granuloma, and psoriasis.3,10 Definitive diagnosis requires histopathology.

Because unilesional self-healing LCH has an excellent prognosis and usually resolves on its own, therapy is unnecessary.3,8 One large retrospective study (N=146) found that of all patients with skin lesions, 56% were managed with biopsy only.5 Other options include watchful waiting and topical corticosteroids. If the skin lesions are large, ulcerated, and/or painful, alkylating antitumor agents have been used. For extensive cutaneous disease, systemic corticosteroids combined with chemotherapy and psoralen plus UVA can be effective.6

The primary concern in the management of self-healing LCH is that the solitary skin lesion may be the harbinger of an aggressive disorder that can progress to systemic disease.5 Moreover, recurrent visceral or disseminated disease may occur months to years after resolution of solitary skin lesions.9 Studies have shown that localized and disseminated disease cannot be differentiated on the basis of clinical findings, histology, immunohistochemistry, or biomarkers.3,11 As a result, an evaluation for systemic disease should be performed at the time of diagnosis for cutaneous LCH.3,9 Minimum baseline studies recommended by the Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society include a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, coagulation studies, chest radiography, skeletal surveys, and urine osmolality testing.12 Periodic clinical follow-up is recommended for all variants of LCH.9

Our case was diagnosed as self-healing LCH based on histologic findings. No treatment was required, and at 3-month follow-up the infant was asymptomatic without recurrence and was meeting all developmental milestones.

- Berres ML, Merad M, Allen CE. Progress in understanding the pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: back to histiocytosis X? Br J Haematol. 2015;169:3-13.

- Jordan MB, Filipovich AH. Histiocytic disorders. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ Jr, Silberstein LE, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:686-700.

- Stein SL, Paller AS, Haut PR, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting in the neonatal period: a retrospective case series. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:778-783.

- Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 1997;29:157-166.

- Morimoto A, Ishida Y, Suzuki N, et al. Nationwide survey of single-system single site Langerhans cell histiocytosis in Japan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:98-102.

- Morren MA, Broecke KV, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse cutaneous presentations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:486-492.

- Berger TG, Lane AT, Headington JT, et al. A solitary variant of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: solitary Hashimoto-Pritzker disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:230.

- Wheller L, Carman N, Butler G. Unilesional self-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:595-599.

- Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156.

- Mehta V, Balachandran C, Lonikar V. Blueberry muffin baby: a pictoral differential diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:8.

- Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children's Medical Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:290-294.

- Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Lancet. 1987;24:208-209.

The Diagnosis: Self-healing Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Histopathologic examination showed an infiltrate of mononuclear cells with indented nuclei admixed with a variable dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated cells that were strongly positive for CD1a (Figure, A) and langerin (Figure, B) antigens as well as S-100 protein (Figure, C), which was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

Histiocytoses are a heterogeneous group of disorders in which the infiltrating cells belong to the mononuclear phagocyte system.1,2 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is the most common dendritic cell-related histiocytosis, occurring in approximately 5 per 1 million children annually, giving it an incidence comparable to pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma and acute myeloid leukemia.1,2

Historically, there has been much debate about the pathogenesis of the disease.2 Until recently it was unknown whether LCH was primarily a neoplastic or an inflammatory disorder. Although the condition initially was thought to have a reactive etiology,1 more recent evidence suggests a clonal neoplastic process. Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions are clonal and display malignancy-associated mechanisms such as immune evasion. Genome sequencing has revealed several mutations in precursor myeloid cells that result in the common downstream hyperactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway that regulates cell proliferation and differentiation.1

Langerhans cell histiocytosis displays a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes, which historically were subclassified as eosinophilic granulomas (localized lesions in bone), Hand-Schüller-Christian disease (multiple organ involvement with the classic triad of skull defects, diabetes insipidus, and exophthalmos), and Letterer-Siwe disease (visceral lesions involving multiple organs).3 However, in 1997 the Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society redefined LCH as single-system single site (SS-s) LCH, single-system multisite LCH, and multisystem LCH.4

In SS-s LCH, the most common site is bone (82%), followed by the skin (12%).5 Skin SS-s LCH classically presents as multiple skin lesions at birth without systemic manifestations; the lesions spontaneously involute within a few months.6 Less commonly, skin SS-s LCH can present as a single lesion. Berger et al7 described 4 neonates with unilesional skin SS-s LCH. Since then, more than 30 cases have been reported in the literature,8 and we report herein another unilesional self-healing LCH.

The morphology of skin lesions in self-healing LCH is highly variable, with the most common being multiple erythematous crusted papules (50%), followed by eczematous scaly lesions resembling seborrheic dermatitis in intertriginous areas (37.5%).3,6 Unilesional self-healing LCH typically presents as an ulcerated or crusted nodule or papule on the trunk. This variability results in a large differential diagnosis. Self-healing LCH is easily mistaken for infectious processes including neonatal herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infection.9 Often, the dermatology department is consulted to rule out LCH when the asymptomatic neonate does not respond to parenteral acyclovir.

Less commonly, the magenta-colored papulonodules of self-healing LCH can mimic blueberry muffin rash and mandate a workup for intrauterine infections, especially cytomegalovirus, rubella, and blood dyscrasia.10 Other noninfectious processes in the differential of self-healing LCH include congenital infantile hemangioma, neonatal lupus erythematosus, seborrheic dermatitis (cradle cap), pyogenic granuloma, and psoriasis.3,10 Definitive diagnosis requires histopathology.

Because unilesional self-healing LCH has an excellent prognosis and usually resolves on its own, therapy is unnecessary.3,8 One large retrospective study (N=146) found that of all patients with skin lesions, 56% were managed with biopsy only.5 Other options include watchful waiting and topical corticosteroids. If the skin lesions are large, ulcerated, and/or painful, alkylating antitumor agents have been used. For extensive cutaneous disease, systemic corticosteroids combined with chemotherapy and psoralen plus UVA can be effective.6

The primary concern in the management of self-healing LCH is that the solitary skin lesion may be the harbinger of an aggressive disorder that can progress to systemic disease.5 Moreover, recurrent visceral or disseminated disease may occur months to years after resolution of solitary skin lesions.9 Studies have shown that localized and disseminated disease cannot be differentiated on the basis of clinical findings, histology, immunohistochemistry, or biomarkers.3,11 As a result, an evaluation for systemic disease should be performed at the time of diagnosis for cutaneous LCH.3,9 Minimum baseline studies recommended by the Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society include a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, coagulation studies, chest radiography, skeletal surveys, and urine osmolality testing.12 Periodic clinical follow-up is recommended for all variants of LCH.9

Our case was diagnosed as self-healing LCH based on histologic findings. No treatment was required, and at 3-month follow-up the infant was asymptomatic without recurrence and was meeting all developmental milestones.

The Diagnosis: Self-healing Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Histopathologic examination showed an infiltrate of mononuclear cells with indented nuclei admixed with a variable dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated cells that were strongly positive for CD1a (Figure, A) and langerin (Figure, B) antigens as well as S-100 protein (Figure, C), which was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

Histiocytoses are a heterogeneous group of disorders in which the infiltrating cells belong to the mononuclear phagocyte system.1,2 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is the most common dendritic cell-related histiocytosis, occurring in approximately 5 per 1 million children annually, giving it an incidence comparable to pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma and acute myeloid leukemia.1,2

Historically, there has been much debate about the pathogenesis of the disease.2 Until recently it was unknown whether LCH was primarily a neoplastic or an inflammatory disorder. Although the condition initially was thought to have a reactive etiology,1 more recent evidence suggests a clonal neoplastic process. Langerhans cell histiocytosis lesions are clonal and display malignancy-associated mechanisms such as immune evasion. Genome sequencing has revealed several mutations in precursor myeloid cells that result in the common downstream hyperactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway that regulates cell proliferation and differentiation.1

Langerhans cell histiocytosis displays a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes, which historically were subclassified as eosinophilic granulomas (localized lesions in bone), Hand-Schüller-Christian disease (multiple organ involvement with the classic triad of skull defects, diabetes insipidus, and exophthalmos), and Letterer-Siwe disease (visceral lesions involving multiple organs).3 However, in 1997 the Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society redefined LCH as single-system single site (SS-s) LCH, single-system multisite LCH, and multisystem LCH.4

In SS-s LCH, the most common site is bone (82%), followed by the skin (12%).5 Skin SS-s LCH classically presents as multiple skin lesions at birth without systemic manifestations; the lesions spontaneously involute within a few months.6 Less commonly, skin SS-s LCH can present as a single lesion. Berger et al7 described 4 neonates with unilesional skin SS-s LCH. Since then, more than 30 cases have been reported in the literature,8 and we report herein another unilesional self-healing LCH.

The morphology of skin lesions in self-healing LCH is highly variable, with the most common being multiple erythematous crusted papules (50%), followed by eczematous scaly lesions resembling seborrheic dermatitis in intertriginous areas (37.5%).3,6 Unilesional self-healing LCH typically presents as an ulcerated or crusted nodule or papule on the trunk. This variability results in a large differential diagnosis. Self-healing LCH is easily mistaken for infectious processes including neonatal herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infection.9 Often, the dermatology department is consulted to rule out LCH when the asymptomatic neonate does not respond to parenteral acyclovir.

Less commonly, the magenta-colored papulonodules of self-healing LCH can mimic blueberry muffin rash and mandate a workup for intrauterine infections, especially cytomegalovirus, rubella, and blood dyscrasia.10 Other noninfectious processes in the differential of self-healing LCH include congenital infantile hemangioma, neonatal lupus erythematosus, seborrheic dermatitis (cradle cap), pyogenic granuloma, and psoriasis.3,10 Definitive diagnosis requires histopathology.

Because unilesional self-healing LCH has an excellent prognosis and usually resolves on its own, therapy is unnecessary.3,8 One large retrospective study (N=146) found that of all patients with skin lesions, 56% were managed with biopsy only.5 Other options include watchful waiting and topical corticosteroids. If the skin lesions are large, ulcerated, and/or painful, alkylating antitumor agents have been used. For extensive cutaneous disease, systemic corticosteroids combined with chemotherapy and psoralen plus UVA can be effective.6

The primary concern in the management of self-healing LCH is that the solitary skin lesion may be the harbinger of an aggressive disorder that can progress to systemic disease.5 Moreover, recurrent visceral or disseminated disease may occur months to years after resolution of solitary skin lesions.9 Studies have shown that localized and disseminated disease cannot be differentiated on the basis of clinical findings, histology, immunohistochemistry, or biomarkers.3,11 As a result, an evaluation for systemic disease should be performed at the time of diagnosis for cutaneous LCH.3,9 Minimum baseline studies recommended by the Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society include a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, coagulation studies, chest radiography, skeletal surveys, and urine osmolality testing.12 Periodic clinical follow-up is recommended for all variants of LCH.9

Our case was diagnosed as self-healing LCH based on histologic findings. No treatment was required, and at 3-month follow-up the infant was asymptomatic without recurrence and was meeting all developmental milestones.

- Berres ML, Merad M, Allen CE. Progress in understanding the pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: back to histiocytosis X? Br J Haematol. 2015;169:3-13.

- Jordan MB, Filipovich AH. Histiocytic disorders. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ Jr, Silberstein LE, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:686-700.

- Stein SL, Paller AS, Haut PR, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting in the neonatal period: a retrospective case series. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:778-783.

- Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 1997;29:157-166.

- Morimoto A, Ishida Y, Suzuki N, et al. Nationwide survey of single-system single site Langerhans cell histiocytosis in Japan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:98-102.

- Morren MA, Broecke KV, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse cutaneous presentations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:486-492.

- Berger TG, Lane AT, Headington JT, et al. A solitary variant of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: solitary Hashimoto-Pritzker disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:230.

- Wheller L, Carman N, Butler G. Unilesional self-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:595-599.

- Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156.

- Mehta V, Balachandran C, Lonikar V. Blueberry muffin baby: a pictoral differential diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:8.

- Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children's Medical Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:290-294.

- Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Lancet. 1987;24:208-209.

- Berres ML, Merad M, Allen CE. Progress in understanding the pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: back to histiocytosis X? Br J Haematol. 2015;169:3-13.

- Jordan MB, Filipovich AH. Histiocytic disorders. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ Jr, Silberstein LE, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:686-700.

- Stein SL, Paller AS, Haut PR, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting in the neonatal period: a retrospective case series. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:778-783.

- Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 1997;29:157-166.

- Morimoto A, Ishida Y, Suzuki N, et al. Nationwide survey of single-system single site Langerhans cell histiocytosis in Japan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:98-102.

- Morren MA, Broecke KV, Vangeebergen L, et al. Diverse cutaneous presentations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:486-492.

- Berger TG, Lane AT, Headington JT, et al. A solitary variant of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: solitary Hashimoto-Pritzker disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:230.

- Wheller L, Carman N, Butler G. Unilesional self-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:595-599.

- Battistella M, Fraitag S, Teillac DH, et al. Neonatal and early infantile cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis: comparison of self-regressive and non-self-regressive forms. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:149-156.

- Mehta V, Balachandran C, Lonikar V. Blueberry muffin baby: a pictoral differential diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:8.

- Kapur P, Erickson C, Rakheja D, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (Hashimoto-Pritzker disease): ten-year experience at Dallas Children's Medical Center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:290-294.

- Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Lancet. 1987;24:208-209.

Dermatology consultation was called to the delivery room to evaluate a red, hemorrhagic, crusted, 5-mm papule on the right lateral upper arm of a preterm newborn. He appeared vigorous with an Apgar score of 7 at 1 minute and 8 at 5 minutes. Physical examination was otherwise normal. Of note, the mother presented late to prenatal care. Her herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus status was unknown. A shave biopsy of the papule was performed at 3 days of age.

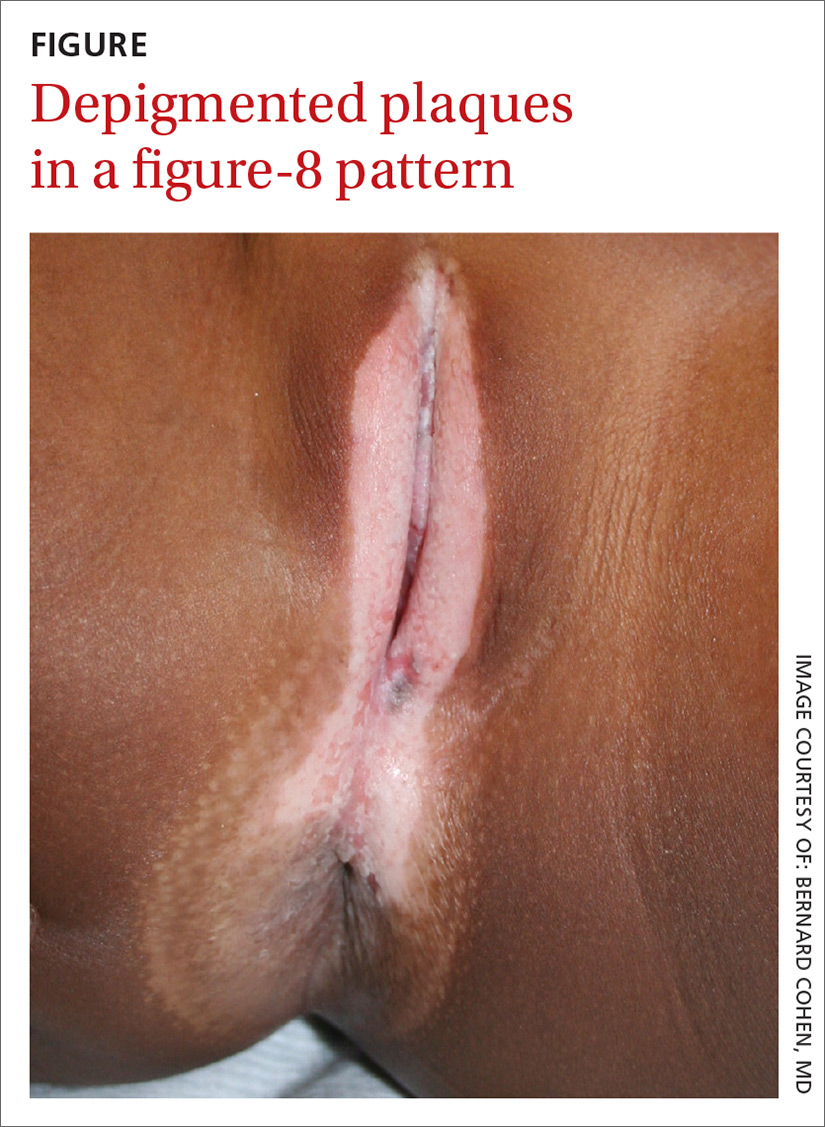

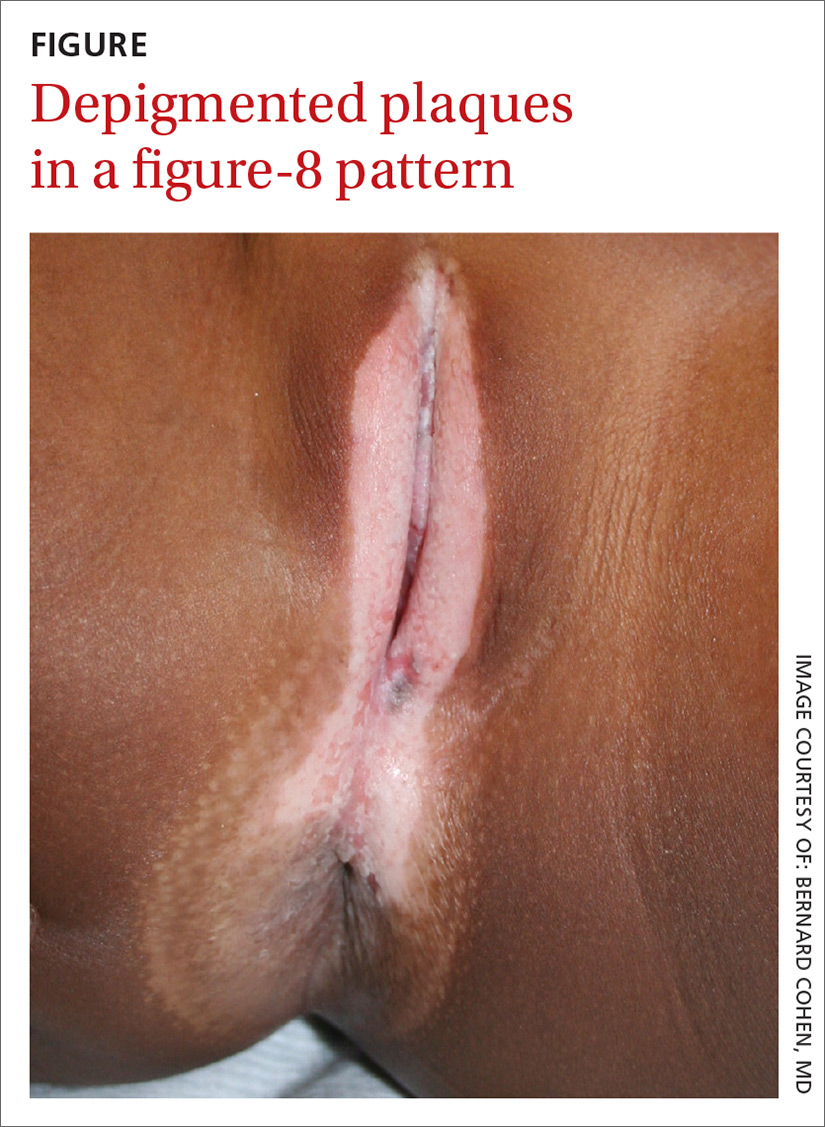

Depigmented plaques on vulva

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; sabubuck@hawaii.edu.

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; sabubuck@hawaii.edu.

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; sabubuck@hawaii.edu.

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.