User login

Why consults don’t happen

Today our team saw an 89-year-old gentleman on the hospitalist service with dementia, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and problems falling. His last known fall was less than 3 months ago and resulted in a broken hip requiring surgical intervention. This was his fourth hospitalization in 6 months, yet it was the first time he was seen by our service.

The frequency at which palliative care (PC) consults are ordered in a particular hospital varies widely. Some reasons for this are not easy fixes – PC is not available in each hospital (as was the case in two of this gentleman’s four hospitalizations), many PC teams are available only Monday-Friday, and patient volumes within a hospital ebb and flow with much less predictability than the tides.

However, some of the reasons are amenable to change. These might include the particular group of hospitalists, or one attending physician, utilizing PC consults less frequently than another. Or it may simply be that the connection was not made between the patient’s experience and the usefulness of an early PC consults. Screening tools are one method of decreasing variability in PC involvement as well as increasing the appropriateness of our service for a particular patient.

There are quite a few palliative care screening tools available. Many of them focus on what most of us would expect, which are the most common diagnoses we see (late-stage cancer, HF, cirrhosis, end-stage renal disease, dementia, etc.). Multiple studies have estimated that mature PC programs in large hospitals are consulted on 1%-2% of live discharges. However, we estimate that more than 10% of these discharged patients have palliative needs that go unmet. While it is true that we wish PC could be involved in all of these lives, this large number of people who spend time in the hospital with these diagnoses, coupled with a national shortage of PC providers, translates into an unbalanced equation.

Rather than looking at a specific diagnosis, we suggest incorporating inquiries on the presence of "palliative care–related problems." While these might require more thought or investigation into a patient’s situation, we find them to be more fruitful than using diagnosis alone.

Some examples? Mismatch between the expectations of the medical team vs. patient/family when it comes to prognosis or the goals of care would be one of them. Another might be persistent uncontrolled symptoms despite usual medical management. Family members disagreeing or demonstrating concerns about the goals of care is still another.

Having used various screening tools in multiple hospitals and clinical settings, we suggest the following considerations in setting up your own:

• Stakeholder management: The right services and staff need to agree on this being a way to improve quality of care (we always provide an "opt-out" option for those who don’t want us involved for some reason).

• Start small: Implement these on one unit at a time or limit the diagnoses to one or two conditions only. You can make the criteria less stringent if the PC team’s bandwidth is not too narrow.

• Be flexible: Even by starting small, there will be times that the PC teams are overwhelmed on a particular day leaving the occasional patient who meets criteria unseen. If the consult is urgent, a phone call is appropriate so that an assumption isn’t made that the screening tool will catch 100% of the patients.

• Track data: When using these tools, palliative care teams have been able to show things such as improved Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey results and decreased readmissions. Demonstrate what you’re doing for your institution so that you can expand the units or patients served.

PC screening tools are an effective way to decrease variability and improve quality. For examples of tools that we use, please get in touch. Find our contact info and read earlier columns at ehospitalistnews/Palliatively.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Today our team saw an 89-year-old gentleman on the hospitalist service with dementia, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and problems falling. His last known fall was less than 3 months ago and resulted in a broken hip requiring surgical intervention. This was his fourth hospitalization in 6 months, yet it was the first time he was seen by our service.

The frequency at which palliative care (PC) consults are ordered in a particular hospital varies widely. Some reasons for this are not easy fixes – PC is not available in each hospital (as was the case in two of this gentleman’s four hospitalizations), many PC teams are available only Monday-Friday, and patient volumes within a hospital ebb and flow with much less predictability than the tides.

However, some of the reasons are amenable to change. These might include the particular group of hospitalists, or one attending physician, utilizing PC consults less frequently than another. Or it may simply be that the connection was not made between the patient’s experience and the usefulness of an early PC consults. Screening tools are one method of decreasing variability in PC involvement as well as increasing the appropriateness of our service for a particular patient.

There are quite a few palliative care screening tools available. Many of them focus on what most of us would expect, which are the most common diagnoses we see (late-stage cancer, HF, cirrhosis, end-stage renal disease, dementia, etc.). Multiple studies have estimated that mature PC programs in large hospitals are consulted on 1%-2% of live discharges. However, we estimate that more than 10% of these discharged patients have palliative needs that go unmet. While it is true that we wish PC could be involved in all of these lives, this large number of people who spend time in the hospital with these diagnoses, coupled with a national shortage of PC providers, translates into an unbalanced equation.

Rather than looking at a specific diagnosis, we suggest incorporating inquiries on the presence of "palliative care–related problems." While these might require more thought or investigation into a patient’s situation, we find them to be more fruitful than using diagnosis alone.

Some examples? Mismatch between the expectations of the medical team vs. patient/family when it comes to prognosis or the goals of care would be one of them. Another might be persistent uncontrolled symptoms despite usual medical management. Family members disagreeing or demonstrating concerns about the goals of care is still another.

Having used various screening tools in multiple hospitals and clinical settings, we suggest the following considerations in setting up your own:

• Stakeholder management: The right services and staff need to agree on this being a way to improve quality of care (we always provide an "opt-out" option for those who don’t want us involved for some reason).

• Start small: Implement these on one unit at a time or limit the diagnoses to one or two conditions only. You can make the criteria less stringent if the PC team’s bandwidth is not too narrow.

• Be flexible: Even by starting small, there will be times that the PC teams are overwhelmed on a particular day leaving the occasional patient who meets criteria unseen. If the consult is urgent, a phone call is appropriate so that an assumption isn’t made that the screening tool will catch 100% of the patients.

• Track data: When using these tools, palliative care teams have been able to show things such as improved Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey results and decreased readmissions. Demonstrate what you’re doing for your institution so that you can expand the units or patients served.

PC screening tools are an effective way to decrease variability and improve quality. For examples of tools that we use, please get in touch. Find our contact info and read earlier columns at ehospitalistnews/Palliatively.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Today our team saw an 89-year-old gentleman on the hospitalist service with dementia, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and problems falling. His last known fall was less than 3 months ago and resulted in a broken hip requiring surgical intervention. This was his fourth hospitalization in 6 months, yet it was the first time he was seen by our service.

The frequency at which palliative care (PC) consults are ordered in a particular hospital varies widely. Some reasons for this are not easy fixes – PC is not available in each hospital (as was the case in two of this gentleman’s four hospitalizations), many PC teams are available only Monday-Friday, and patient volumes within a hospital ebb and flow with much less predictability than the tides.

However, some of the reasons are amenable to change. These might include the particular group of hospitalists, or one attending physician, utilizing PC consults less frequently than another. Or it may simply be that the connection was not made between the patient’s experience and the usefulness of an early PC consults. Screening tools are one method of decreasing variability in PC involvement as well as increasing the appropriateness of our service for a particular patient.

There are quite a few palliative care screening tools available. Many of them focus on what most of us would expect, which are the most common diagnoses we see (late-stage cancer, HF, cirrhosis, end-stage renal disease, dementia, etc.). Multiple studies have estimated that mature PC programs in large hospitals are consulted on 1%-2% of live discharges. However, we estimate that more than 10% of these discharged patients have palliative needs that go unmet. While it is true that we wish PC could be involved in all of these lives, this large number of people who spend time in the hospital with these diagnoses, coupled with a national shortage of PC providers, translates into an unbalanced equation.

Rather than looking at a specific diagnosis, we suggest incorporating inquiries on the presence of "palliative care–related problems." While these might require more thought or investigation into a patient’s situation, we find them to be more fruitful than using diagnosis alone.

Some examples? Mismatch between the expectations of the medical team vs. patient/family when it comes to prognosis or the goals of care would be one of them. Another might be persistent uncontrolled symptoms despite usual medical management. Family members disagreeing or demonstrating concerns about the goals of care is still another.

Having used various screening tools in multiple hospitals and clinical settings, we suggest the following considerations in setting up your own:

• Stakeholder management: The right services and staff need to agree on this being a way to improve quality of care (we always provide an "opt-out" option for those who don’t want us involved for some reason).

• Start small: Implement these on one unit at a time or limit the diagnoses to one or two conditions only. You can make the criteria less stringent if the PC team’s bandwidth is not too narrow.

• Be flexible: Even by starting small, there will be times that the PC teams are overwhelmed on a particular day leaving the occasional patient who meets criteria unseen. If the consult is urgent, a phone call is appropriate so that an assumption isn’t made that the screening tool will catch 100% of the patients.

• Track data: When using these tools, palliative care teams have been able to show things such as improved Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey results and decreased readmissions. Demonstrate what you’re doing for your institution so that you can expand the units or patients served.

PC screening tools are an effective way to decrease variability and improve quality. For examples of tools that we use, please get in touch. Find our contact info and read earlier columns at ehospitalistnews/Palliatively.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Negotiation: Priceless in good communication

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail sjbekanich@seton.org.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, comments: We all have seen these discussions go well and been impressed by those who lead them. However, too often such conversations and family meetings are not actively pursued simply because they are "hard" - they take time and an investment of one's emotional energy. We should follow the example of many medical schools and training programs in recognizing the immense importance of gaining these skills, and foster the desire to be the one that others aim to emulate.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, comments: We all have seen these discussions go well and been impressed by those who lead them. However, too often such conversations and family meetings are not actively pursued simply because they are "hard" - they take time and an investment of one's emotional energy. We should follow the example of many medical schools and training programs in recognizing the immense importance of gaining these skills, and foster the desire to be the one that others aim to emulate.

Dr. Eric Gartman, FCCP, comments: We all have seen these discussions go well and been impressed by those who lead them. However, too often such conversations and family meetings are not actively pursued simply because they are "hard" - they take time and an investment of one's emotional energy. We should follow the example of many medical schools and training programs in recognizing the immense importance of gaining these skills, and foster the desire to be the one that others aim to emulate.

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail sjbekanich@seton.org.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail sjbekanich@seton.org.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Negotiation: Priceless in good communication

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail sjbekanich@seton.org.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail sjbekanich@seton.org.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

The Society of Hospital Medicine held its annual meeting recently in Las Vegas, and Stephen had the opportunity to speak on the topic of "Family Meetings: The Art and the Evidence." As a special edition of Palliatively Speaking, we thought we would highlight one aspect of this subject, with other elements forthcoming in future pieces.

As a hospitalist, I stumbled and stuttered through many family meetings until I eventually found myself on more comfortable ground. Overall, I found them rewarding when they went well but stressful and deflating when they did not. The latter sensation was enough to create some avoidant behavior on my part.

After a few years of practice, my hospitalist group began shadowing one another periodically on rounds to provide feedback to our colleagues in the hope of improving the quality of our communication skills. It was then that I noticed that one of my partners was a master at these meetings. A real Rembrandt. He had the ability to deliver bad or difficult news without the dynamic in the room becoming inflammatory or out of control.

I will never forget watching him mediate a disagreement between a nurse and a patient suspected of using illicit substances while hospitalized. He flipped an antagonistic, heated situation into one where the patient, nurse, and physician all agreed on putting the past to rest and forging ahead with his proposed plan. We all left the room with a genuine sense that we had mutual purpose. In my admiration I realized that some of these skills must be teachable.

While I didn’t act on learning those communication techniques immediately after that encounter, I would eventually be formally exposed to them during my palliative medicine training. As it turns out, I still have some uncomfortable meetings with patients and families, but they come around much less frequently and when they do I now have a variety of tools to deal with challenges.

My appreciation of these tools doesn’t stop when I walk through the hospital doors each evening. I have found them to be invaluable in my personal life. In fact, learning to communicate better has been a source of renewal for me at work and staves off burnout. These techniques include active listening, motivational interviewing, demonstration of empathy, conflict resolution, and also negotiation. For the Society of Hospital Medicine meeting audience, I dissected negotiation, citing how it and the other skills can inject vitality into your interactions.

In any negotiation, it’s all about the other party. You are the smallest person in the room, the least important.

This is counterintuitive. Oftentimes at work we are trying to convince everyone how important we are. The readmissions committee should implement your plan to reduce recurrent hospitalizations. Your fellow hospitalists should recognize your value and make you the leader of the group. Patients show their appreciation for you making the right diagnosis and averting a medical calamity for them. But when you enter a family meeting, the patient and his or her loved ones are the center stage. To be successful you have to listen more and talk less. Get to understand the pictures in their heads and then summarize those thoughts and ideas back to them to show you’ve listened.

Make emotional payments. I don’t get into the meat of the meeting until I’ve done that with the patient and every family member in the room. No one holds family meetings for patients who are thriving and have outstanding outcomes. We have family meetings to figure out goals in the face of terrible diseases, when elder abuse is a possibility, when insurance-funded resources are depleted, and for a host of other difficult reasons.

This means that everyone in the room is suffering, sacrificing, scared, confused, or worried. Acknowledge them. Hold them up. Thank them. Reflect on similar moments in your life and demonstrate empathy. Apologize when things haven’t gone right for them at your hospital. These payments will pay handsome dividends as your relationship evolves.

Not manipulation. The term negotiation might bring up images of used car salespeople. I strongly disagree. In manipulation, one side wins and the other doesn’t. In negotiation, the goal is improved communication and understanding. Manipulation is about one side of the equation having knowledge that the other side is lacking and using that to achieve its means. Negotiators hope everyone at the table has the same knowledge.

This leads to two key principles of negotiations: transparency and genuineness. Patients and families are excellent at taking the temperature of the room when you sit down to meet with them. Share knowledge. Don’t have any hidden agendas. Following this principle builds trust.

Be incremental. Taking patients from comfortable, familiar territory into that which is uncomfortable or unfamiliar should not be done in one giant leap. Let’s use code status (CS) as an example because of the frequency with which it comes up (though I rarely talk about CS without first understanding the patient’s goals and hopes).

Some patients refuse to talk about CS, so I think incrementally. I ask that they consider talking about CS with me in the future. Very few people refuse to consider something. Two or three days later I ask, "Have you considered talking to me about CS?" That by itself opens up the topic for conversation. In the extremely unusual case where they still won’t engage, I then ask them, "What would it take for you to consider talking to me about this?" More incrementalism.

While this is not nearly an exhaustive list of negotiation techniques, we hope it is stimulating enough that you might be curious enough to learn more on your own and try incorporating this into your practice. If you’re motivated to do so, please feel free to contact us for reading suggestions: E-mail sjbekanich@seton.org.

Dr. Bekanich and Dr. Fredholm are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

‘One call’ pilot program made chronic pain a priority

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

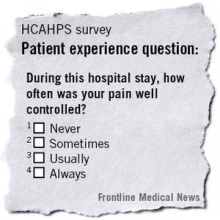

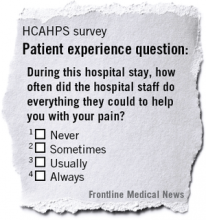

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

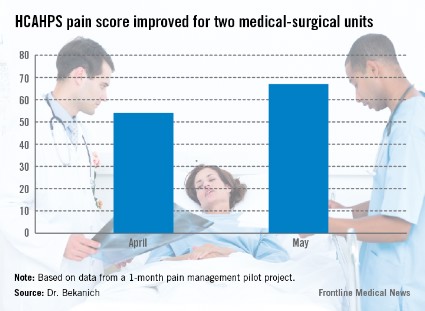

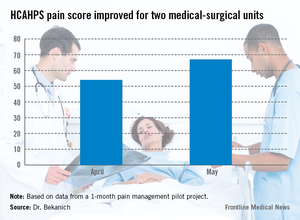

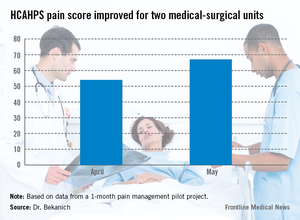

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at SJBekanich@seton.org.

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at SJBekanich@seton.org.

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.