User login

New research in otitis media means new controversies

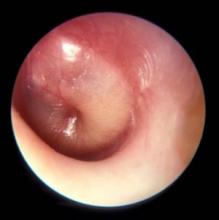

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

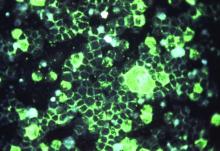

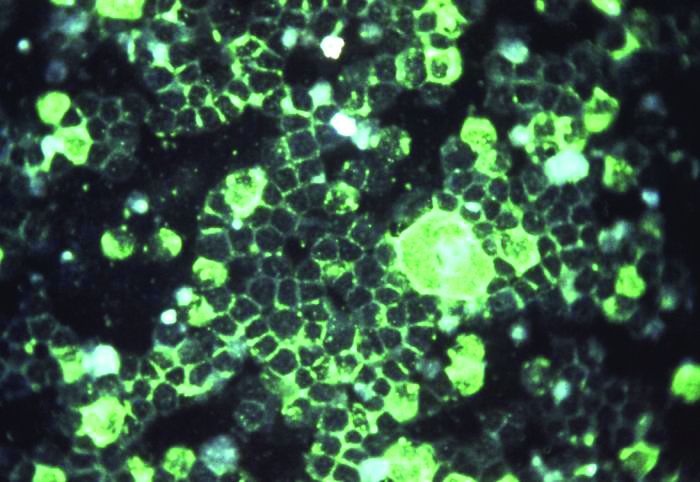

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

Research yields 5 key points about vaccine hesitancy

ATLANTA – While there is no question about the need to address pockets of increasing vaccine refusals, determining how to address it requires a better understanding of the forces underlying vaccine hesitancy.

This area of research is still young, but Glen Nowak, PhD, a visiting communication scientist at the National Vaccine Program Office and director of the Grady College Center for Health & Risk Communication at the University of Georgia in Athens, drew on multiple recent studies and an in-progress review of vaccine hesitancy and confidence literature to distill five key findings from recent research into vaccine hesitancy. He presented that summary at a conference sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The first insight: There is a lot of interest in understanding vaccine hesitancy and confidence. But the rub is that many inconsistencies and uncertainties exist, because efforts remain in the early stages of research.

Dr. Nowak referenced the November 2014 report of the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization to define vaccine hesitancy as the “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services.” But that hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place, and type of vaccine, the report found.

Those who are hesitant about vaccines are not a homogeneous group, Dr. Nowak said. Their degree of indecision ranges from refusing all vaccines, refusing some and accepting others, or delaying some but not others, to full acceptance of all vaccines despite hesitancy. Their attitudes also vary about vaccination overall and about specific vaccines.

“Vaccines hesitancy is influenced by several factors: complacency, convenience, and confidence,” Dr. Nowak said.

“Generally speaking, the end goal of all of our efforts is vaccine coverage, and before that is vaccine acceptance,” he said. “Before acceptance is hesitancy, and confidence is considered the precursor to hesitancy.” But no clear definition or measure of “vaccine confidence” exists yet.

Dr. Nowak next highlighted the second key finding: that research has identified an association between vaccine hesitancy or vaccine-related hesitancy and vaccine acceptance.

A 2016 study found that scores from the Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines Survey predicted under-immunization in children at 19 months of age, and three studies from 2008 through 2012 found a greater likelihood to delay or refuse vaccines among parents who had vaccine-related doubts.

Focus groups have found that parents who express hesitation or a lack of trust in vaccines also tend to mention using “alternative schedules,” including delaying vaccines or only vaccinating their children with select vaccines instead of all the recommended immunizations.

The third key finding Dr. Nowak discussed returned to the idea of “vaccine confidence,” which has aroused more interest in research but which requires refinement before it can become a truly helpful concept. Studies have already found links between confidence and parents vaccinating their children, but the field lacks standard measures.

“There are all different definitions that are out there, but they have not been measured,” Dr. Nowak said.

For example, the 2015 National Vaccine Advisory Committee report defined vaccine confidence as parents’ or health care providers’ trust in three areas: the immunizations recommended by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the providers who administer the vaccines, and the processes that lead to vaccine licensure and vaccine recommendations.

But other definitions might include having faith that a person will benefit from a vaccine or that they won’t experience harm, or lacking any concerns about potential adverse outcomes.

The fourth key finding of recent research delivered positive news, Dr. Nowak noted: “Vaccines do relatively well compared to other health-related products that parents of young children have to make decisions about, such as antibiotics, over-the-counter medicines and vitamins.”

For example, in one study, the mean score (scale 1-10) of parents’ confidence that their child will not have a bad or serious adverse reaction to a recommended vaccine was 6.6, the same as the confidence level for antibiotics and only slightly below the scores of 6.8 for OTC medications and 7.3 for vitamins. Vaccines and antibiotics tied for the highest score for parents’ confidence in their effectiveness: 7.1, compared with 6.3 for OTC medications and 5.8 for vitamins. And of all four products, parents had the highest faith in vaccines as benefiting their children’s health.

But it was the final finding Dr. Nowak discussed that can present some of the greatest challenges to addressing vaccine hesitancy: Parents’ direct and indirect experiences play a significant role in their confidence about vaccines.

One study found that nearly a quarter of parents reported knowing someone who had a “bad reaction” to a vaccine (aside from soreness, fever, redness, or swelling), compared with 16.7% reporting that someone they knew had a bad reaction to an OTC medication. About one-third of parents reported the same for antibiotics.

Similarly, the measles outbreak at Disneyland in 2015 increased parents’ confidence in the safety and effectiveness of the CDC-recommended childhood vaccination schedule, and in the belief that their child’s health would benefit from receiving all the recommended vaccines.

Dr. Nowak reported no disclosures.

ATLANTA – While there is no question about the need to address pockets of increasing vaccine refusals, determining how to address it requires a better understanding of the forces underlying vaccine hesitancy.

This area of research is still young, but Glen Nowak, PhD, a visiting communication scientist at the National Vaccine Program Office and director of the Grady College Center for Health & Risk Communication at the University of Georgia in Athens, drew on multiple recent studies and an in-progress review of vaccine hesitancy and confidence literature to distill five key findings from recent research into vaccine hesitancy. He presented that summary at a conference sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The first insight: There is a lot of interest in understanding vaccine hesitancy and confidence. But the rub is that many inconsistencies and uncertainties exist, because efforts remain in the early stages of research.

Dr. Nowak referenced the November 2014 report of the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization to define vaccine hesitancy as the “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services.” But that hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place, and type of vaccine, the report found.

Those who are hesitant about vaccines are not a homogeneous group, Dr. Nowak said. Their degree of indecision ranges from refusing all vaccines, refusing some and accepting others, or delaying some but not others, to full acceptance of all vaccines despite hesitancy. Their attitudes also vary about vaccination overall and about specific vaccines.

“Vaccines hesitancy is influenced by several factors: complacency, convenience, and confidence,” Dr. Nowak said.

“Generally speaking, the end goal of all of our efforts is vaccine coverage, and before that is vaccine acceptance,” he said. “Before acceptance is hesitancy, and confidence is considered the precursor to hesitancy.” But no clear definition or measure of “vaccine confidence” exists yet.

Dr. Nowak next highlighted the second key finding: that research has identified an association between vaccine hesitancy or vaccine-related hesitancy and vaccine acceptance.

A 2016 study found that scores from the Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines Survey predicted under-immunization in children at 19 months of age, and three studies from 2008 through 2012 found a greater likelihood to delay or refuse vaccines among parents who had vaccine-related doubts.

Focus groups have found that parents who express hesitation or a lack of trust in vaccines also tend to mention using “alternative schedules,” including delaying vaccines or only vaccinating their children with select vaccines instead of all the recommended immunizations.

The third key finding Dr. Nowak discussed returned to the idea of “vaccine confidence,” which has aroused more interest in research but which requires refinement before it can become a truly helpful concept. Studies have already found links between confidence and parents vaccinating their children, but the field lacks standard measures.

“There are all different definitions that are out there, but they have not been measured,” Dr. Nowak said.

For example, the 2015 National Vaccine Advisory Committee report defined vaccine confidence as parents’ or health care providers’ trust in three areas: the immunizations recommended by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the providers who administer the vaccines, and the processes that lead to vaccine licensure and vaccine recommendations.

But other definitions might include having faith that a person will benefit from a vaccine or that they won’t experience harm, or lacking any concerns about potential adverse outcomes.

The fourth key finding of recent research delivered positive news, Dr. Nowak noted: “Vaccines do relatively well compared to other health-related products that parents of young children have to make decisions about, such as antibiotics, over-the-counter medicines and vitamins.”

For example, in one study, the mean score (scale 1-10) of parents’ confidence that their child will not have a bad or serious adverse reaction to a recommended vaccine was 6.6, the same as the confidence level for antibiotics and only slightly below the scores of 6.8 for OTC medications and 7.3 for vitamins. Vaccines and antibiotics tied for the highest score for parents’ confidence in their effectiveness: 7.1, compared with 6.3 for OTC medications and 5.8 for vitamins. And of all four products, parents had the highest faith in vaccines as benefiting their children’s health.

But it was the final finding Dr. Nowak discussed that can present some of the greatest challenges to addressing vaccine hesitancy: Parents’ direct and indirect experiences play a significant role in their confidence about vaccines.

One study found that nearly a quarter of parents reported knowing someone who had a “bad reaction” to a vaccine (aside from soreness, fever, redness, or swelling), compared with 16.7% reporting that someone they knew had a bad reaction to an OTC medication. About one-third of parents reported the same for antibiotics.

Similarly, the measles outbreak at Disneyland in 2015 increased parents’ confidence in the safety and effectiveness of the CDC-recommended childhood vaccination schedule, and in the belief that their child’s health would benefit from receiving all the recommended vaccines.

Dr. Nowak reported no disclosures.

ATLANTA – While there is no question about the need to address pockets of increasing vaccine refusals, determining how to address it requires a better understanding of the forces underlying vaccine hesitancy.

This area of research is still young, but Glen Nowak, PhD, a visiting communication scientist at the National Vaccine Program Office and director of the Grady College Center for Health & Risk Communication at the University of Georgia in Athens, drew on multiple recent studies and an in-progress review of vaccine hesitancy and confidence literature to distill five key findings from recent research into vaccine hesitancy. He presented that summary at a conference sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The first insight: There is a lot of interest in understanding vaccine hesitancy and confidence. But the rub is that many inconsistencies and uncertainties exist, because efforts remain in the early stages of research.

Dr. Nowak referenced the November 2014 report of the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization to define vaccine hesitancy as the “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services.” But that hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place, and type of vaccine, the report found.

Those who are hesitant about vaccines are not a homogeneous group, Dr. Nowak said. Their degree of indecision ranges from refusing all vaccines, refusing some and accepting others, or delaying some but not others, to full acceptance of all vaccines despite hesitancy. Their attitudes also vary about vaccination overall and about specific vaccines.

“Vaccines hesitancy is influenced by several factors: complacency, convenience, and confidence,” Dr. Nowak said.

“Generally speaking, the end goal of all of our efforts is vaccine coverage, and before that is vaccine acceptance,” he said. “Before acceptance is hesitancy, and confidence is considered the precursor to hesitancy.” But no clear definition or measure of “vaccine confidence” exists yet.

Dr. Nowak next highlighted the second key finding: that research has identified an association between vaccine hesitancy or vaccine-related hesitancy and vaccine acceptance.

A 2016 study found that scores from the Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines Survey predicted under-immunization in children at 19 months of age, and three studies from 2008 through 2012 found a greater likelihood to delay or refuse vaccines among parents who had vaccine-related doubts.

Focus groups have found that parents who express hesitation or a lack of trust in vaccines also tend to mention using “alternative schedules,” including delaying vaccines or only vaccinating their children with select vaccines instead of all the recommended immunizations.

The third key finding Dr. Nowak discussed returned to the idea of “vaccine confidence,” which has aroused more interest in research but which requires refinement before it can become a truly helpful concept. Studies have already found links between confidence and parents vaccinating their children, but the field lacks standard measures.

“There are all different definitions that are out there, but they have not been measured,” Dr. Nowak said.

For example, the 2015 National Vaccine Advisory Committee report defined vaccine confidence as parents’ or health care providers’ trust in three areas: the immunizations recommended by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the providers who administer the vaccines, and the processes that lead to vaccine licensure and vaccine recommendations.

But other definitions might include having faith that a person will benefit from a vaccine or that they won’t experience harm, or lacking any concerns about potential adverse outcomes.

The fourth key finding of recent research delivered positive news, Dr. Nowak noted: “Vaccines do relatively well compared to other health-related products that parents of young children have to make decisions about, such as antibiotics, over-the-counter medicines and vitamins.”

For example, in one study, the mean score (scale 1-10) of parents’ confidence that their child will not have a bad or serious adverse reaction to a recommended vaccine was 6.6, the same as the confidence level for antibiotics and only slightly below the scores of 6.8 for OTC medications and 7.3 for vitamins. Vaccines and antibiotics tied for the highest score for parents’ confidence in their effectiveness: 7.1, compared with 6.3 for OTC medications and 5.8 for vitamins. And of all four products, parents had the highest faith in vaccines as benefiting their children’s health.

But it was the final finding Dr. Nowak discussed that can present some of the greatest challenges to addressing vaccine hesitancy: Parents’ direct and indirect experiences play a significant role in their confidence about vaccines.

One study found that nearly a quarter of parents reported knowing someone who had a “bad reaction” to a vaccine (aside from soreness, fever, redness, or swelling), compared with 16.7% reporting that someone they knew had a bad reaction to an OTC medication. About one-third of parents reported the same for antibiotics.

Similarly, the measles outbreak at Disneyland in 2015 increased parents’ confidence in the safety and effectiveness of the CDC-recommended childhood vaccination schedule, and in the belief that their child’s health would benefit from receiving all the recommended vaccines.

Dr. Nowak reported no disclosures.

Pornography warps children’s concept of sex, sexual identity

SAN FRANCISCO – The pornography industry has taken over children’s sense of self and sexuality and warped their concept of what sex and a sexual identity is, said Gail Dines, PhD.

She challenged pediatricians to shape policy and help parents in wrangling back that control in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The culprit, Dr. Dines charged, is the multibillion-dollar porn industry that exploded around the year 2000 with the Internet. Then, in 2011, the business model shifted to free pornography to hook young boys in their adolescence and hopefully maintain them as customers after age 18 when they could get their own credit cards.

The average age of a boy’s first encounter with pornography is age 11, explained Dr. Dines, a professor of sociology and women’s studies at Wheelock College in Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Instead of a father’s Playboy featuring a naked woman in a cornfield, as many male pediatricians in the room might have been introduced to pornography or sexuality, today’s youth are introduced via the brutalization and dehumanization of women, she said. Such experiences traumatize the children viewing them, who become confused about who they are if they are masturbating to images and video of sexual violence, and then they enter a cycle of retraumatization that engenders shame while bringing children back to those sites again and again.

“Hence, in the business model of free porn, you are building in trauma, which is building in addiction,” Dr. Dines said. The effects of this exposure and addiction, based on decades of research, include limited capacity for intimacy, a greater likelihood of using coercive tactics for sex, decreased empathy for rape victims, increased depression and anxiety, and, most recently, rates of erectile dysfunction in males aged 15-27 that mirror the rates in those aged 27-35.

“We have never brought up boys with access to hard core pornography 24-7,” Dr. Dines said. The best way to tackle hard-core pornography is a public health model that educates parents and pediatricians who can band together to raise awareness. Her organization, Culture Reframed, is attempting to do precisely that.

Dr. Dines founded the nonprofit Culture Reframed, which attempts to counter the effects of the pornography industry and media sexuality. Her presentation used no external funding.

SAN FRANCISCO – The pornography industry has taken over children’s sense of self and sexuality and warped their concept of what sex and a sexual identity is, said Gail Dines, PhD.

She challenged pediatricians to shape policy and help parents in wrangling back that control in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The culprit, Dr. Dines charged, is the multibillion-dollar porn industry that exploded around the year 2000 with the Internet. Then, in 2011, the business model shifted to free pornography to hook young boys in their adolescence and hopefully maintain them as customers after age 18 when they could get their own credit cards.

The average age of a boy’s first encounter with pornography is age 11, explained Dr. Dines, a professor of sociology and women’s studies at Wheelock College in Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Instead of a father’s Playboy featuring a naked woman in a cornfield, as many male pediatricians in the room might have been introduced to pornography or sexuality, today’s youth are introduced via the brutalization and dehumanization of women, she said. Such experiences traumatize the children viewing them, who become confused about who they are if they are masturbating to images and video of sexual violence, and then they enter a cycle of retraumatization that engenders shame while bringing children back to those sites again and again.

“Hence, in the business model of free porn, you are building in trauma, which is building in addiction,” Dr. Dines said. The effects of this exposure and addiction, based on decades of research, include limited capacity for intimacy, a greater likelihood of using coercive tactics for sex, decreased empathy for rape victims, increased depression and anxiety, and, most recently, rates of erectile dysfunction in males aged 15-27 that mirror the rates in those aged 27-35.

“We have never brought up boys with access to hard core pornography 24-7,” Dr. Dines said. The best way to tackle hard-core pornography is a public health model that educates parents and pediatricians who can band together to raise awareness. Her organization, Culture Reframed, is attempting to do precisely that.

Dr. Dines founded the nonprofit Culture Reframed, which attempts to counter the effects of the pornography industry and media sexuality. Her presentation used no external funding.

SAN FRANCISCO – The pornography industry has taken over children’s sense of self and sexuality and warped their concept of what sex and a sexual identity is, said Gail Dines, PhD.

She challenged pediatricians to shape policy and help parents in wrangling back that control in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The culprit, Dr. Dines charged, is the multibillion-dollar porn industry that exploded around the year 2000 with the Internet. Then, in 2011, the business model shifted to free pornography to hook young boys in their adolescence and hopefully maintain them as customers after age 18 when they could get their own credit cards.

The average age of a boy’s first encounter with pornography is age 11, explained Dr. Dines, a professor of sociology and women’s studies at Wheelock College in Chestnut Hill, Mass.

Instead of a father’s Playboy featuring a naked woman in a cornfield, as many male pediatricians in the room might have been introduced to pornography or sexuality, today’s youth are introduced via the brutalization and dehumanization of women, she said. Such experiences traumatize the children viewing them, who become confused about who they are if they are masturbating to images and video of sexual violence, and then they enter a cycle of retraumatization that engenders shame while bringing children back to those sites again and again.

“Hence, in the business model of free porn, you are building in trauma, which is building in addiction,” Dr. Dines said. The effects of this exposure and addiction, based on decades of research, include limited capacity for intimacy, a greater likelihood of using coercive tactics for sex, decreased empathy for rape victims, increased depression and anxiety, and, most recently, rates of erectile dysfunction in males aged 15-27 that mirror the rates in those aged 27-35.

“We have never brought up boys with access to hard core pornography 24-7,” Dr. Dines said. The best way to tackle hard-core pornography is a public health model that educates parents and pediatricians who can band together to raise awareness. Her organization, Culture Reframed, is attempting to do precisely that.

Dr. Dines founded the nonprofit Culture Reframed, which attempts to counter the effects of the pornography industry and media sexuality. Her presentation used no external funding.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 16

Mental health integration into pediatric primary care offers multiple benefits

SAN FRANCISCO – Integrating pediatric mental health care into your primary care office can be an effective way to ensure your patients get the care they really need – and it’s easier than you think.

That’s the message Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, delivered to a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

He noted that depression and anxiety are among the top five conditions driving overall health costs in the United States, and a 1999 Surgeon General’s Report found that one in five children have a diagnosable mental disorder – but only a fifth to a quarter of these children receive treatment. The rub is that treatment is highly successful; it’s just difficult to access for many families, so making it a part of a child’s medical home just makes sense, Dr. Rabinowitz said.

To drive home his point, he described a case of a depressed adolescent with cutting and suicidal ideation, and the steps he would need to take without integration: find out their insurance, get a list of covered mental health professionals, refer to someone he may or may not heard of, and then rarely receive follow-up reports, much less confirmation the patient had gone to the appointment. With integrated care, parents can make appointments on their way out, he can read the psychologist’s report immediately after the visit, and he can drop in to say hello during the child’s mental health appointment.

“Sometimes there’s a question abut a medication or something, and sometimes it’s an inopportune moment if the child is sad or crying, but generally it seems to be pretty popular,” he said.

Taking steps toward integration

If providers are interesting in exploring the possibility of integration, they need to consider and decide on several issues before taking any concrete steps, Dr. Rabinowitz said. One is the type of arrangement that would work best for your practice: hiring on mental health professionals as employees of the practice, hiring independent contractors, coordinating a space share agreement or creating an out-of-office agreement.

“In our practice, psychologists are employees of the practice, but there are other arrangements,” he said, and some may depend on what is easiest based on state law or billing procedures.

The next question is what kind of provider(s) you would hire. His office has child psychologists with a PhD and postdoctorate fellowships working with children, but other possibilities include social workers, licensed counselors, psychiatric nurse practitioners, or psychiatrists.

Another consideration is what diagnoses your office will handle because it’s not possible to see everything. His practice sees patients in-house for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, anxiety, drug counseling, and behavioral and adjustment disorders. They choose to refer out educational testing, autism, difficult divorce cases, and complex cases that require more than 20 sessions. They refer out divorce cases because they frequently require specialized knowledge and a lot of court time and phone calls. Aside from ADHD evaluations, his office does not see the staff’s children.

Providers also should consider options for adapting their physical space to accommodate integration. His practice converted an exam room into a consultation room, making it homier with a throw rug, soft chairs, a painted wall, and office decor.

Establishing effective protocols with integration

The next step after providers decide to integrate is to determine the office protocols that govern what forms get used, who can schedule appointments and how long they last, billing, and similar procedures.

“You need to have certain protocols, and some of these things you don’t think about it until you start doing it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. Should mental health appointments be 50 minutes, for example, or 20 to 25 minutes? His office has gradually shrunk these appointments from 50 to 30 minutes, but they give psychologists an hour of time each day for follow-up phone calls.

Forms to consider developing include a disclosure form, notice of privacy practices, late cancel/no show policy, financial policy, and a summary of parent concerns. His office’s charting includes an extensive intake form with medical, treatment, family, and social history, an intake summary, and a progress note.

It’s with reimbursement, of course, that providers will need to do the most research, particularly with regard to their state’s laws and in looking for grants to provide funding – which is more available than many realize.

“Money is often out there if you look for it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.” Mental health is an area where no one is really against it: You get together the NRA (National Rifle Association) and the anti-gun movement, and they are both for it.”

Planning for reimbursement challenges

Reimbursement barriers can include lack of payment if mental health codes are used instead of pediatrics ones (depending on the practice arrangement), lack of “incident to” payments, same day billing of physical and mental health appointments, reimbursement for screening, and lack of payment for non–face-to-face services. Although a concierge or fee-for-service option solves many of these, it excludes Medicaid patients and is an economic barrier for many families.

Mental health networks offer a different route, but they can involve poor reimbursement and an additional layer of administration, which makes financial integration more viable as long as providers investigate their options.

“It’s going to be a regional variation, and you need to look at state rules and regulations,” Dr. Rabinowitz said, explaining that his office then sought insurance contracts to include mental health care reimbursement through their office and then sought the same from Medicaid.

“We weren’t about to see Medicaid patients for fear of an audit unless we got written permission, but we got that,” he said. His office simply asked for it and received in writing a letter starting as follows: “Under Department policy, they (our psychologists) may submit E&M claims to Medicaid under a supervising physician’s billing ID. It is not mandatory they be credentialed into a BHO (Behavioral Healthcare Options) network…”

He also noted that his state allows inclusion of psychologists on medical malpractice insurance policies, which is far less expensive for mental health professionals, compared with medical doctors.

Ultimately, the result of mental health integration into primary care practices is greater satisfaction among patients and pediatricians as well as potentially better health outcomes, Dr. Rabinowitz said. An in-house patient satisfaction survey his office conducted found that 91% of parents felt it was convenient for their child to receive mental health services at the same location as medical care, and 90% were satisfied with their care. Only 9% cited barriers to their child seeing a psychologist at their office, and 89% found the services beneficial for their child. Similarly, providers find integration more convenient, easier for follow-up, less stressful, and more efficient while improving communication, confidence, and follow-up.

Dr. Rabinowitz reported no disclosures. No external funding was used for the presentation.

SAN FRANCISCO – Integrating pediatric mental health care into your primary care office can be an effective way to ensure your patients get the care they really need – and it’s easier than you think.

That’s the message Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, delivered to a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

He noted that depression and anxiety are among the top five conditions driving overall health costs in the United States, and a 1999 Surgeon General’s Report found that one in five children have a diagnosable mental disorder – but only a fifth to a quarter of these children receive treatment. The rub is that treatment is highly successful; it’s just difficult to access for many families, so making it a part of a child’s medical home just makes sense, Dr. Rabinowitz said.

To drive home his point, he described a case of a depressed adolescent with cutting and suicidal ideation, and the steps he would need to take without integration: find out their insurance, get a list of covered mental health professionals, refer to someone he may or may not heard of, and then rarely receive follow-up reports, much less confirmation the patient had gone to the appointment. With integrated care, parents can make appointments on their way out, he can read the psychologist’s report immediately after the visit, and he can drop in to say hello during the child’s mental health appointment.

“Sometimes there’s a question abut a medication or something, and sometimes it’s an inopportune moment if the child is sad or crying, but generally it seems to be pretty popular,” he said.

Taking steps toward integration

If providers are interesting in exploring the possibility of integration, they need to consider and decide on several issues before taking any concrete steps, Dr. Rabinowitz said. One is the type of arrangement that would work best for your practice: hiring on mental health professionals as employees of the practice, hiring independent contractors, coordinating a space share agreement or creating an out-of-office agreement.

“In our practice, psychologists are employees of the practice, but there are other arrangements,” he said, and some may depend on what is easiest based on state law or billing procedures.

The next question is what kind of provider(s) you would hire. His office has child psychologists with a PhD and postdoctorate fellowships working with children, but other possibilities include social workers, licensed counselors, psychiatric nurse practitioners, or psychiatrists.

Another consideration is what diagnoses your office will handle because it’s not possible to see everything. His practice sees patients in-house for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, anxiety, drug counseling, and behavioral and adjustment disorders. They choose to refer out educational testing, autism, difficult divorce cases, and complex cases that require more than 20 sessions. They refer out divorce cases because they frequently require specialized knowledge and a lot of court time and phone calls. Aside from ADHD evaluations, his office does not see the staff’s children.

Providers also should consider options for adapting their physical space to accommodate integration. His practice converted an exam room into a consultation room, making it homier with a throw rug, soft chairs, a painted wall, and office decor.

Establishing effective protocols with integration

The next step after providers decide to integrate is to determine the office protocols that govern what forms get used, who can schedule appointments and how long they last, billing, and similar procedures.

“You need to have certain protocols, and some of these things you don’t think about it until you start doing it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. Should mental health appointments be 50 minutes, for example, or 20 to 25 minutes? His office has gradually shrunk these appointments from 50 to 30 minutes, but they give psychologists an hour of time each day for follow-up phone calls.

Forms to consider developing include a disclosure form, notice of privacy practices, late cancel/no show policy, financial policy, and a summary of parent concerns. His office’s charting includes an extensive intake form with medical, treatment, family, and social history, an intake summary, and a progress note.

It’s with reimbursement, of course, that providers will need to do the most research, particularly with regard to their state’s laws and in looking for grants to provide funding – which is more available than many realize.

“Money is often out there if you look for it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.” Mental health is an area where no one is really against it: You get together the NRA (National Rifle Association) and the anti-gun movement, and they are both for it.”

Planning for reimbursement challenges

Reimbursement barriers can include lack of payment if mental health codes are used instead of pediatrics ones (depending on the practice arrangement), lack of “incident to” payments, same day billing of physical and mental health appointments, reimbursement for screening, and lack of payment for non–face-to-face services. Although a concierge or fee-for-service option solves many of these, it excludes Medicaid patients and is an economic barrier for many families.

Mental health networks offer a different route, but they can involve poor reimbursement and an additional layer of administration, which makes financial integration more viable as long as providers investigate their options.

“It’s going to be a regional variation, and you need to look at state rules and regulations,” Dr. Rabinowitz said, explaining that his office then sought insurance contracts to include mental health care reimbursement through their office and then sought the same from Medicaid.

“We weren’t about to see Medicaid patients for fear of an audit unless we got written permission, but we got that,” he said. His office simply asked for it and received in writing a letter starting as follows: “Under Department policy, they (our psychologists) may submit E&M claims to Medicaid under a supervising physician’s billing ID. It is not mandatory they be credentialed into a BHO (Behavioral Healthcare Options) network…”

He also noted that his state allows inclusion of psychologists on medical malpractice insurance policies, which is far less expensive for mental health professionals, compared with medical doctors.

Ultimately, the result of mental health integration into primary care practices is greater satisfaction among patients and pediatricians as well as potentially better health outcomes, Dr. Rabinowitz said. An in-house patient satisfaction survey his office conducted found that 91% of parents felt it was convenient for their child to receive mental health services at the same location as medical care, and 90% were satisfied with their care. Only 9% cited barriers to their child seeing a psychologist at their office, and 89% found the services beneficial for their child. Similarly, providers find integration more convenient, easier for follow-up, less stressful, and more efficient while improving communication, confidence, and follow-up.

Dr. Rabinowitz reported no disclosures. No external funding was used for the presentation.

SAN FRANCISCO – Integrating pediatric mental health care into your primary care office can be an effective way to ensure your patients get the care they really need – and it’s easier than you think.

That’s the message Jay Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, delivered to a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

He noted that depression and anxiety are among the top five conditions driving overall health costs in the United States, and a 1999 Surgeon General’s Report found that one in five children have a diagnosable mental disorder – but only a fifth to a quarter of these children receive treatment. The rub is that treatment is highly successful; it’s just difficult to access for many families, so making it a part of a child’s medical home just makes sense, Dr. Rabinowitz said.

To drive home his point, he described a case of a depressed adolescent with cutting and suicidal ideation, and the steps he would need to take without integration: find out their insurance, get a list of covered mental health professionals, refer to someone he may or may not heard of, and then rarely receive follow-up reports, much less confirmation the patient had gone to the appointment. With integrated care, parents can make appointments on their way out, he can read the psychologist’s report immediately after the visit, and he can drop in to say hello during the child’s mental health appointment.

“Sometimes there’s a question abut a medication or something, and sometimes it’s an inopportune moment if the child is sad or crying, but generally it seems to be pretty popular,” he said.

Taking steps toward integration

If providers are interesting in exploring the possibility of integration, they need to consider and decide on several issues before taking any concrete steps, Dr. Rabinowitz said. One is the type of arrangement that would work best for your practice: hiring on mental health professionals as employees of the practice, hiring independent contractors, coordinating a space share agreement or creating an out-of-office agreement.

“In our practice, psychologists are employees of the practice, but there are other arrangements,” he said, and some may depend on what is easiest based on state law or billing procedures.

The next question is what kind of provider(s) you would hire. His office has child psychologists with a PhD and postdoctorate fellowships working with children, but other possibilities include social workers, licensed counselors, psychiatric nurse practitioners, or psychiatrists.

Another consideration is what diagnoses your office will handle because it’s not possible to see everything. His practice sees patients in-house for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, anxiety, drug counseling, and behavioral and adjustment disorders. They choose to refer out educational testing, autism, difficult divorce cases, and complex cases that require more than 20 sessions. They refer out divorce cases because they frequently require specialized knowledge and a lot of court time and phone calls. Aside from ADHD evaluations, his office does not see the staff’s children.

Providers also should consider options for adapting their physical space to accommodate integration. His practice converted an exam room into a consultation room, making it homier with a throw rug, soft chairs, a painted wall, and office decor.

Establishing effective protocols with integration

The next step after providers decide to integrate is to determine the office protocols that govern what forms get used, who can schedule appointments and how long they last, billing, and similar procedures.

“You need to have certain protocols, and some of these things you don’t think about it until you start doing it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said. Should mental health appointments be 50 minutes, for example, or 20 to 25 minutes? His office has gradually shrunk these appointments from 50 to 30 minutes, but they give psychologists an hour of time each day for follow-up phone calls.

Forms to consider developing include a disclosure form, notice of privacy practices, late cancel/no show policy, financial policy, and a summary of parent concerns. His office’s charting includes an extensive intake form with medical, treatment, family, and social history, an intake summary, and a progress note.

It’s with reimbursement, of course, that providers will need to do the most research, particularly with regard to their state’s laws and in looking for grants to provide funding – which is more available than many realize.

“Money is often out there if you look for it,” Dr. Rabinowitz said.” Mental health is an area where no one is really against it: You get together the NRA (National Rifle Association) and the anti-gun movement, and they are both for it.”

Planning for reimbursement challenges

Reimbursement barriers can include lack of payment if mental health codes are used instead of pediatrics ones (depending on the practice arrangement), lack of “incident to” payments, same day billing of physical and mental health appointments, reimbursement for screening, and lack of payment for non–face-to-face services. Although a concierge or fee-for-service option solves many of these, it excludes Medicaid patients and is an economic barrier for many families.

Mental health networks offer a different route, but they can involve poor reimbursement and an additional layer of administration, which makes financial integration more viable as long as providers investigate their options.

“It’s going to be a regional variation, and you need to look at state rules and regulations,” Dr. Rabinowitz said, explaining that his office then sought insurance contracts to include mental health care reimbursement through their office and then sought the same from Medicaid.

“We weren’t about to see Medicaid patients for fear of an audit unless we got written permission, but we got that,” he said. His office simply asked for it and received in writing a letter starting as follows: “Under Department policy, they (our psychologists) may submit E&M claims to Medicaid under a supervising physician’s billing ID. It is not mandatory they be credentialed into a BHO (Behavioral Healthcare Options) network…”

He also noted that his state allows inclusion of psychologists on medical malpractice insurance policies, which is far less expensive for mental health professionals, compared with medical doctors.

Ultimately, the result of mental health integration into primary care practices is greater satisfaction among patients and pediatricians as well as potentially better health outcomes, Dr. Rabinowitz said. An in-house patient satisfaction survey his office conducted found that 91% of parents felt it was convenient for their child to receive mental health services at the same location as medical care, and 90% were satisfied with their care. Only 9% cited barriers to their child seeing a psychologist at their office, and 89% found the services beneficial for their child. Similarly, providers find integration more convenient, easier for follow-up, less stressful, and more efficient while improving communication, confidence, and follow-up.

Dr. Rabinowitz reported no disclosures. No external funding was used for the presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 16

New screen time guidelines address rapid changes in media environment

SAN FRANCISCO – A new set of policy statements on children’s media use from the American Academy of Pediatrics brings the recommendations into the 21st century.

The new guidance, released at the annual meeting of the AAP, synthesizes the most current evidence on mobile devices, interactivity, educational technology, sleep, obesity, cognitive development, and other aspects of the pervasive digital environment children now grow up in.

“I think our policy statement reflects the changes in the media landscape because not all media use is the same,” Megan A. Moreno, MD, lead author of the policy statement, “Media Use in School-Aged Children and Adolescents,” said during a press conference (Pediatrics. 2016, Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2592).

The new statement both lowers the overall age at which parents can feel comfortable introducing their children to media and decreases the amount of screen time exposure per day. One key component of the new guidelines includes the unveiling of a new tool parents can use to create a Family Media Plan. The tool, available at https://www.healthychildren.org/English/media/Pages/default.aspx, enables parents to create a plan for each child in the household and reflects the individuality of each child’s use and age-appropriate guidelines.

After parents enter children’s names, the plan provides an editable template for each child that lays out screen-free zones, screen-free times, device curfews, recreational screen-time choices, alternative activities during non-screen time, media manners, digital citizenship, personal safety, sleep, and exercise.

Previous policy statements from the AAP relied primarily on research about television, a passive screen experience. In an age where many children and teens have interactive screens in their pockets and visit grandparents via video conferencing, however, the AAP Council on Communications and Media has likewise broadened its definition of media and noted the problems with applying research about television to other totally different types of screens.

“When we’re using media to connect, this is not what we’re traditionally calling screen time. These are tools,” Jenny S. Radesky, MD, lead author of the policy statement “Media and Young Minds,” said at the press conference (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2592). She referred to the fact that many families who are spread across great distances, such as parents deployed overseas or grandparents in another state, use Skype, FaceTime, Google Hangouts, and similar programs to communicate and remain connected.

“We’re making sure our relationships are staying strong and not something to be discouraged with infants and toddlers, even though infants and toddlers will need their parent’s help to understand what they’re seeing on the screen,” said Dr. Radesky, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The policy statement further notes that some emerging evidence has suggested children aged 2 and older can learn words from live video chatting with a responsive adult or by using an interactive touch screen that scaffolds learning.

An earlier introduction to screens

Among the most significant changes to the recommendations for children up to 5 years old is an allowance for introducing media before age 2, the previous policy’s age recommendation.

“If you want to introduce media, 18 months is the age when kids are cognitively ready to start, but we’re not saying parents need to introduce media then,” Dr. Radesky said, adding that more research is needed regarding devices such as tablets before it’s possible to know whether apps can be beneficial in toddlers that young. “There’s not enough evidence to know if interactivity helps or not right now,” she said.

The “Media and Young Minds” policy statement notes that children under age 2 years develop their cognitive, language, motor, and social-emotional skills through hands-on exploration and social interaction with trusted adults.

“Apps can’t do the things that parents’ minds can do or children’s minds can do on their own,” Dr. Radesky said. The policy notes that digital books, or eBooks, can be beneficial when used like a traditional physical book, but interactive elements to these eBooks could be distracting and decrease children’s comprehension.

When parents do choose to introduce media to their children, it’s “crucial that media be a shared experience” between the caregiving adult and the child, she said. “Think of media as a teaching tool, a way to connect and to create, not just to consume,” Dr. Radesky said.

What can preschoolers learn?

Although some laboratory research shows toddlers as young as 15 months can learn new words from touch screens, they have difficulty transferring that knowledge to the three-dimensional world. For children aged 3-5 years, however, both well-designed television programming and high-quality learning apps from Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and the Sesame Workshop have shown benefits. In addition to early literacy, math, and personal and social development skills learned from shows such as Sesame Street, preschoolers have learned literacy skills from those programs’ apps.

But those apps are unfortunately in the minority.

“Most apps parents find under the ‘educational’ category in app stores have no such evidence of efficacy, target only rote academic skills, are not based on established curricula, and use little or no input from developmental specialists and educators,” the “Media and Young Minds” policy states. “The higher-order thinking skills and executive functions essential for school success, such as task persistence, impulse control, emotion regulation, and creative, flexible thinking, are best taught through unstructured and social (not digital) play, as well as responsive parent-child interactions.”

Risks and recommendations for preschoolers

Heavy media use among preschoolers, meanwhile, carries risks of increased weight – primarily as a result of food advertising and eating while watching TV – as well as reduced sleep and cognitive, language, and social/emotional delays.

“Content is crucial,” the “Media and Young Minds” policy notes. “Experimental evidence shows that switching from violent content to educational/prosocial content results in significant improvement in behavioral symptoms, particularly for low-income boys.”

The key points of the new statement therefore include the following recommendations:

• Limit media use to 1 hour a day in children ages 2 years and older.

• Do not use screens during mealtimes and for 1 hour before bedtime.

• Start discussing family and child media use with parents early in children’s lives.

• Educate parents about early brain development and help families develop a Family Media Use Plan.

• Discourage screen use besides video-chatting in children under 18 months old.

• Encourage caregiving adults to use screen media with children aged 18-24 months, who should not use it on their own.

• Encourage parents to rely on high-quality programming products such as PBS Kids, Sesame Workshop, and Common Sense Media.

• Help parents with challenges such as setting limits, finding alternatives to screen time, and calming children without using media.

• Avoid using screens or media to calm children except during rare extenuating circumstances, such as painful medical procedures and airplane flights.

• Encourage parents to avoid fast-paced programs, apps with distracting content, any media with violent content, and any background television, which can stunt children’s early language development.

Understanding older youth’s media use

As children move into school age and adolescence, the opportunities and utilities for media use expand – and so do the risks. Children and teens can benefit from media through gaining social support, learning about healthy behaviors, and discovering new ideas and knowledge, but youth remain at risk for obesity, sleep problems, cyberbullying, compromised privacy, and exposure to inaccurate, inappropriate or unsafe content, the “Media Use in School-Aged Children and Adolescents” policy statement reports.

Despite the wide range of media types available, TV remains the most commonly used media type among school-aged children and teens and is watched an average of 2 hours a day. Still, 91% of boys have access to a video game console, and 84% report playing games online or on a mobile phone. Further, three-quarters of teens own a smartphone and 76% use at least one social media site, with more than 70% maintaining a “social media portfolio” across several platforms.

Such social media use can provide teens with helpful support networks, particularly for those with ongoing illnesses or disabilities or those needing community support as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, or intersex individuals. Social media can also promote wellness and healthy behaviors such as eating well and not smoking.

Risks for school-aged children and adolescents using media

Yet social media also can open the door to cyberbullying, leading to short-term and long-term social, academic, and health problems. It carries the risk of exploitation of youth or their images, or predation from pornographers and pedophiles. Children and teens must be made aware that the “Internet is forever” and should be taught to consider privacy and confidentiality concerns in their use of social and other media.

Another concern is teens’ “sexting,” in which they share sexually explicit messages and/or partly or fully nude photos. Exposures to unhealthy behaviors, such as substance abuse, sexual behaviors, self-injury, or disordered eating are likewise among the risks of social media, as they are with television and cinema.

In fact, TV/movie content showing alcohol use, smoking, and sexual activity is linked to earlier experimentation among children and adolescents. In addition, each extra hour of television watching is associated with increase in body mass index, as is having a TV set in the bedroom. Enjoying entertainment media while doing school work is linked to poor learning and academics.

Excessive media use may lead to problematic Internet use and Internet gaming disorder as described in the DSM-5, occurring among 4%-8.5% of children and adolescents.

“Symptoms can include a preoccupation with the activity, decreased interest in offline or ‘real life’ relationships, unsuccessful attempts to decrease use and withdrawal symptoms,” the “Media Use in School-Aged Children and Adolescents” policy statement notes.

Recommendations for older children

The policy statement advises pediatricians to help families and schools promote understanding of media’s risks and benefits, including awareness of tools to screen for sexting, cyberbullying, problematic Internet use, and Internet gaming disorder. Pediatricians should advocate for training in media literacy in the community and encourage parents to follow the media, sleep, and physical activity guidelines included in the Family Media Plan.

The research was supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The authors reported no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A new set of policy statements on children’s media use from the American Academy of Pediatrics brings the recommendations into the 21st century.

The new guidance, released at the annual meeting of the AAP, synthesizes the most current evidence on mobile devices, interactivity, educational technology, sleep, obesity, cognitive development, and other aspects of the pervasive digital environment children now grow up in.

“I think our policy statement reflects the changes in the media landscape because not all media use is the same,” Megan A. Moreno, MD, lead author of the policy statement, “Media Use in School-Aged Children and Adolescents,” said during a press conference (Pediatrics. 2016, Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2592).

The new statement both lowers the overall age at which parents can feel comfortable introducing their children to media and decreases the amount of screen time exposure per day. One key component of the new guidelines includes the unveiling of a new tool parents can use to create a Family Media Plan. The tool, available at https://www.healthychildren.org/English/media/Pages/default.aspx, enables parents to create a plan for each child in the household and reflects the individuality of each child’s use and age-appropriate guidelines.

After parents enter children’s names, the plan provides an editable template for each child that lays out screen-free zones, screen-free times, device curfews, recreational screen-time choices, alternative activities during non-screen time, media manners, digital citizenship, personal safety, sleep, and exercise.

Previous policy statements from the AAP relied primarily on research about television, a passive screen experience. In an age where many children and teens have interactive screens in their pockets and visit grandparents via video conferencing, however, the AAP Council on Communications and Media has likewise broadened its definition of media and noted the problems with applying research about television to other totally different types of screens.

“When we’re using media to connect, this is not what we’re traditionally calling screen time. These are tools,” Jenny S. Radesky, MD, lead author of the policy statement “Media and Young Minds,” said at the press conference (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2592). She referred to the fact that many families who are spread across great distances, such as parents deployed overseas or grandparents in another state, use Skype, FaceTime, Google Hangouts, and similar programs to communicate and remain connected.

“We’re making sure our relationships are staying strong and not something to be discouraged with infants and toddlers, even though infants and toddlers will need their parent’s help to understand what they’re seeing on the screen,” said Dr. Radesky, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The policy statement further notes that some emerging evidence has suggested children aged 2 and older can learn words from live video chatting with a responsive adult or by using an interactive touch screen that scaffolds learning.

An earlier introduction to screens

Among the most significant changes to the recommendations for children up to 5 years old is an allowance for introducing media before age 2, the previous policy’s age recommendation.

“If you want to introduce media, 18 months is the age when kids are cognitively ready to start, but we’re not saying parents need to introduce media then,” Dr. Radesky said, adding that more research is needed regarding devices such as tablets before it’s possible to know whether apps can be beneficial in toddlers that young. “There’s not enough evidence to know if interactivity helps or not right now,” she said.

The “Media and Young Minds” policy statement notes that children under age 2 years develop their cognitive, language, motor, and social-emotional skills through hands-on exploration and social interaction with trusted adults.

“Apps can’t do the things that parents’ minds can do or children’s minds can do on their own,” Dr. Radesky said. The policy notes that digital books, or eBooks, can be beneficial when used like a traditional physical book, but interactive elements to these eBooks could be distracting and decrease children’s comprehension.

When parents do choose to introduce media to their children, it’s “crucial that media be a shared experience” between the caregiving adult and the child, she said. “Think of media as a teaching tool, a way to connect and to create, not just to consume,” Dr. Radesky said.

What can preschoolers learn?

Although some laboratory research shows toddlers as young as 15 months can learn new words from touch screens, they have difficulty transferring that knowledge to the three-dimensional world. For children aged 3-5 years, however, both well-designed television programming and high-quality learning apps from Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and the Sesame Workshop have shown benefits. In addition to early literacy, math, and personal and social development skills learned from shows such as Sesame Street, preschoolers have learned literacy skills from those programs’ apps.

But those apps are unfortunately in the minority.

“Most apps parents find under the ‘educational’ category in app stores have no such evidence of efficacy, target only rote academic skills, are not based on established curricula, and use little or no input from developmental specialists and educators,” the “Media and Young Minds” policy states. “The higher-order thinking skills and executive functions essential for school success, such as task persistence, impulse control, emotion regulation, and creative, flexible thinking, are best taught through unstructured and social (not digital) play, as well as responsive parent-child interactions.”

Risks and recommendations for preschoolers