User login

Higher BMI tied to lower breast cancer risk in women before menopause

Although obesity increases the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women, a large multicenter analysis has confirmed the opposite effect in premenopausal women.

The association had “a greater magnitude than previously shown and across the entire distribution of body mass index,” wrote Minouk J. Schoemaker, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research in London, with his associates, on behalf of the Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. The protective effect of adiposity was strongest during young adulthood (ages 18-24 years), when it spanned breast cancer subtypes. “Understanding the biological mechanisms underlying these associations could have important preventive potential,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

Prior studies have linked greater body fat with reduced risk of breast cancer in younger women, but the effect has not been well characterized. For this analysis, the investigators pooled data from 19 cohort studies that included a total of 758,592 premenopausal women; median age was 40.6 years (interquartile range, 35.2-45.5 years).

For each 5-unit increase in BMI, the estimated reduction in risk of breast cancer was 23% among women aged 18-24 years (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.80), 15% in women aged 25-34 years, 13% in women aged 35-44 years, and 12% in women aged 45-54 years. There was no BMI threshold for risk reduction: the inverse correlation existed even when women were not overweight. Risk also did vary significantly among subgroups stratified by other risk factors for breast cancer. Adiposity was more protective against estrogen receptor-positive and progesterone-receptor positive breast cancers and less protective against hormone receptor–negative breast cancers, which “implies a hormonal mechanism,” the investigators said. “Body mass index at ages 25-54 years was not consistently associated with triple-negative or hormone receptor–negative breast cancer overall.”

Funders included Breast Cancer Now, the Institute of Cancer Research, the National Institutes of Health, and many others. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schoemaker MJ et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018; Jun 21. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1771.

Although obesity increases the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women, a large multicenter analysis has confirmed the opposite effect in premenopausal women.

The association had “a greater magnitude than previously shown and across the entire distribution of body mass index,” wrote Minouk J. Schoemaker, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research in London, with his associates, on behalf of the Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. The protective effect of adiposity was strongest during young adulthood (ages 18-24 years), when it spanned breast cancer subtypes. “Understanding the biological mechanisms underlying these associations could have important preventive potential,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

Prior studies have linked greater body fat with reduced risk of breast cancer in younger women, but the effect has not been well characterized. For this analysis, the investigators pooled data from 19 cohort studies that included a total of 758,592 premenopausal women; median age was 40.6 years (interquartile range, 35.2-45.5 years).

For each 5-unit increase in BMI, the estimated reduction in risk of breast cancer was 23% among women aged 18-24 years (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.80), 15% in women aged 25-34 years, 13% in women aged 35-44 years, and 12% in women aged 45-54 years. There was no BMI threshold for risk reduction: the inverse correlation existed even when women were not overweight. Risk also did vary significantly among subgroups stratified by other risk factors for breast cancer. Adiposity was more protective against estrogen receptor-positive and progesterone-receptor positive breast cancers and less protective against hormone receptor–negative breast cancers, which “implies a hormonal mechanism,” the investigators said. “Body mass index at ages 25-54 years was not consistently associated with triple-negative or hormone receptor–negative breast cancer overall.”

Funders included Breast Cancer Now, the Institute of Cancer Research, the National Institutes of Health, and many others. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schoemaker MJ et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018; Jun 21. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1771.

Although obesity increases the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women, a large multicenter analysis has confirmed the opposite effect in premenopausal women.

The association had “a greater magnitude than previously shown and across the entire distribution of body mass index,” wrote Minouk J. Schoemaker, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research in London, with his associates, on behalf of the Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. The protective effect of adiposity was strongest during young adulthood (ages 18-24 years), when it spanned breast cancer subtypes. “Understanding the biological mechanisms underlying these associations could have important preventive potential,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

Prior studies have linked greater body fat with reduced risk of breast cancer in younger women, but the effect has not been well characterized. For this analysis, the investigators pooled data from 19 cohort studies that included a total of 758,592 premenopausal women; median age was 40.6 years (interquartile range, 35.2-45.5 years).

For each 5-unit increase in BMI, the estimated reduction in risk of breast cancer was 23% among women aged 18-24 years (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.80), 15% in women aged 25-34 years, 13% in women aged 35-44 years, and 12% in women aged 45-54 years. There was no BMI threshold for risk reduction: the inverse correlation existed even when women were not overweight. Risk also did vary significantly among subgroups stratified by other risk factors for breast cancer. Adiposity was more protective against estrogen receptor-positive and progesterone-receptor positive breast cancers and less protective against hormone receptor–negative breast cancers, which “implies a hormonal mechanism,” the investigators said. “Body mass index at ages 25-54 years was not consistently associated with triple-negative or hormone receptor–negative breast cancer overall.”

Funders included Breast Cancer Now, the Institute of Cancer Research, the National Institutes of Health, and many others. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schoemaker MJ et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018; Jun 21. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1771.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: In premenopausal women, adiposity inversely correlated with risk of breast cancer, and showed a stronger protective effect than previously documented.

Major finding: For each 5-unit increase in BMI, the estimated reduction in risk of breast cancer was 23% among women aged 18-24 years (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.80), 15% in women aged 25-34 years, 13% in women aged 35-44 years, and 12% in women aged 45-54 years.

Study details: Multicenter analysis of 19 cohort studies.

Disclosures: Funders included Breast Cancer Now, the Institute of Cancer Research, the National Institutes of Health, and many others. The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Schoemaker MJ et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018; Jun 21. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1771.

ASCO 2018: Less is more as ‘tailoring’ takes on new meaning

A record-setting 40,000-plus oncology professionals attended this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago. The outstanding education and scientific program, with the theme of Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, was planned and led by ASCO President Dr Bruce Johnson, professor and director of Thoracic Oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and chaired by Sarah Cannon’s Dr David Spigel and Harvard’s Dr Ann Partridge. A recurring finding throughout the meeting was that “less is more” in several key areas of cancer therapy. From small molecules targeting driver mutations across various tumors to the application of immunotherapy in subsets of common cancers, it is clear that more patients are experiencing dramatic results from novel approaches.

A featured plenary session trial was TAILORx, a study of 10,273 women with hormone-receptor–positive, surgically resected breast cancer that had not spread to the lymph nodes, was less than 5 cm, and was not positive for the HER2 gene amplification. This clinical trial was sponsored by the NCI and initiated in 2006. It used the OncotypeDX genetic test to stratify patients into groups of low, intermediate, or high risk for recurrence. The low-risk patients received only hormonal therapy, and the high-risk patients were treated with hormonal therapy plus chemotherapy.

Dr Joseph Sparano, professor of Medicine and Women’s Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, presented the results from the group of 6,700 intermediate risk women who were randomized to receive hormonal therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. After 9 years of follow-up, 83.3% of the volunteers, as Dr Sparano appropriately referred to them, who were treated with hormonal therapy were still cancer free, compared with 84.3% of those who also received chemotherapy, demonstrating no statistical benefit for the addition of chemotherapy. Of note, breast cancer experts discussing the trial, including Dr Lisa Carey, professor of Breast Cancer Research at the UNC Lineberger Cancer Institute in Chapel Hill, urged that younger women, under the age of 50, with recurrence scores (RS) toward the higher end of the intermediate risk group (RS, 16-25) should still discuss and consider chemotherapy with their physicians. In summary, all patients fitting the study criteria with low (

These landmark and practice changing results mean that each year about 60,000 women in the United States will be spared the side effects of toxic drugs. These 10,273 study volunteers are true heroes to the women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer in coming years.

In the field of lung cancer, many new trial results using immunotherapy were presented, with the most talked about being single-agent pembrolizumab, a PD1 inhibitor, improving survival over traditional chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors, which comprise the majority of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Also in the plenary, Dr Gilberto Lopes of the Sylvester Cancer Center at the University of Miami, presented these results from the KEYNOTE-042 study. In patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of >1%, the benefit in overall survival (OS) of pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy was 16.7 versus 12.1 months, respectively (HR, 0.81). In those patients with a TPS of >20%, the OS benefit was 17.7 versus 1.0 months (HR, 0.77), and in the group with a TPS of >50%, the benefit was 20.0 versus 12.2 months (HR, 0.69). Overall, the quality of life and the occurrence of side effects were substantially better for those patients receiving immunotherapy alone. Other findings presented at the meeting demonstrated the benefit of adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy and of treating with combination immunotherapy (PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors). Many options now exist, much work remains to be done, and accrual to clinical trials is more important than ever.

Another plenary session trial evaluated the benefit of performing a nephrectomy in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a long-held and practiced standard of care. Dr Arnaud Mejean of Paris Descartes University presented findings from the CARMENA trial, which randomized 450 patients with metastatic clear cell RCC to receive cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by sunitinib, or sunitinib alone. The OS results of 18.4 versus 13.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.89) favored sunitinib alone in this noninferiority analysis. Other endpoints lined up in favor of not removing the cancerous kidney, and the presenter and discussants were united in their opinion of the results and the resulting change in doing less surgery in these patients.

In a step away from less therapy, the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study showed that adding 6 months of low-dose maintenance chemotherapy after standard intensive therapy improves survival in children with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. The addition of a vinorelbine and cyclophosphamide low-dose regimen improved 5-year disease-free survival from 69.8% to 77.6% (HR, 0.68) and OS from 73.7% to 86.5% (HR, 0.52) as presented by Dr Gianni Bisogno, University of Padovani, Italy. The maintenance regimen showed no increase in toxicity and actually fewer infections were noted.

In the area of molecular profiling, multiple studies at the meeting demonstrated the importance of assessing cancers for mutations as outstanding results were seen with therapies for NTRK, RET, ROS, and MSI-high driven tumors. In a debate on the role of molecular profiling, I had the opportunity to declare and support our position at Sarah Cannon that all patients with relapsed or metastatic cancers should have this testing performed. It will be through better understanding of the biology of these cancers that we will advance the field for all patients while sometimes finding a target or mutation that will dramatically change the life of a patient.

In keeping with the meeting’s theme, Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, the presentations and the discussions clearly demonstrated that through the use of precision medicine techniques such as prognostic gene assays and molecular profiling, patients can receive the best therapy, even “tailored” therapy, which may often actually be less therapy. It is an exciting time in cancer research, and I have never been more optimistic about the future of cancer treatment for our patients.

A record-setting 40,000-plus oncology professionals attended this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago. The outstanding education and scientific program, with the theme of Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, was planned and led by ASCO President Dr Bruce Johnson, professor and director of Thoracic Oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and chaired by Sarah Cannon’s Dr David Spigel and Harvard’s Dr Ann Partridge. A recurring finding throughout the meeting was that “less is more” in several key areas of cancer therapy. From small molecules targeting driver mutations across various tumors to the application of immunotherapy in subsets of common cancers, it is clear that more patients are experiencing dramatic results from novel approaches.

A featured plenary session trial was TAILORx, a study of 10,273 women with hormone-receptor–positive, surgically resected breast cancer that had not spread to the lymph nodes, was less than 5 cm, and was not positive for the HER2 gene amplification. This clinical trial was sponsored by the NCI and initiated in 2006. It used the OncotypeDX genetic test to stratify patients into groups of low, intermediate, or high risk for recurrence. The low-risk patients received only hormonal therapy, and the high-risk patients were treated with hormonal therapy plus chemotherapy.

Dr Joseph Sparano, professor of Medicine and Women’s Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, presented the results from the group of 6,700 intermediate risk women who were randomized to receive hormonal therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. After 9 years of follow-up, 83.3% of the volunteers, as Dr Sparano appropriately referred to them, who were treated with hormonal therapy were still cancer free, compared with 84.3% of those who also received chemotherapy, demonstrating no statistical benefit for the addition of chemotherapy. Of note, breast cancer experts discussing the trial, including Dr Lisa Carey, professor of Breast Cancer Research at the UNC Lineberger Cancer Institute in Chapel Hill, urged that younger women, under the age of 50, with recurrence scores (RS) toward the higher end of the intermediate risk group (RS, 16-25) should still discuss and consider chemotherapy with their physicians. In summary, all patients fitting the study criteria with low (

These landmark and practice changing results mean that each year about 60,000 women in the United States will be spared the side effects of toxic drugs. These 10,273 study volunteers are true heroes to the women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer in coming years.

In the field of lung cancer, many new trial results using immunotherapy were presented, with the most talked about being single-agent pembrolizumab, a PD1 inhibitor, improving survival over traditional chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors, which comprise the majority of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Also in the plenary, Dr Gilberto Lopes of the Sylvester Cancer Center at the University of Miami, presented these results from the KEYNOTE-042 study. In patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of >1%, the benefit in overall survival (OS) of pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy was 16.7 versus 12.1 months, respectively (HR, 0.81). In those patients with a TPS of >20%, the OS benefit was 17.7 versus 1.0 months (HR, 0.77), and in the group with a TPS of >50%, the benefit was 20.0 versus 12.2 months (HR, 0.69). Overall, the quality of life and the occurrence of side effects were substantially better for those patients receiving immunotherapy alone. Other findings presented at the meeting demonstrated the benefit of adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy and of treating with combination immunotherapy (PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors). Many options now exist, much work remains to be done, and accrual to clinical trials is more important than ever.

Another plenary session trial evaluated the benefit of performing a nephrectomy in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a long-held and practiced standard of care. Dr Arnaud Mejean of Paris Descartes University presented findings from the CARMENA trial, which randomized 450 patients with metastatic clear cell RCC to receive cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by sunitinib, or sunitinib alone. The OS results of 18.4 versus 13.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.89) favored sunitinib alone in this noninferiority analysis. Other endpoints lined up in favor of not removing the cancerous kidney, and the presenter and discussants were united in their opinion of the results and the resulting change in doing less surgery in these patients.

In a step away from less therapy, the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study showed that adding 6 months of low-dose maintenance chemotherapy after standard intensive therapy improves survival in children with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. The addition of a vinorelbine and cyclophosphamide low-dose regimen improved 5-year disease-free survival from 69.8% to 77.6% (HR, 0.68) and OS from 73.7% to 86.5% (HR, 0.52) as presented by Dr Gianni Bisogno, University of Padovani, Italy. The maintenance regimen showed no increase in toxicity and actually fewer infections were noted.

In the area of molecular profiling, multiple studies at the meeting demonstrated the importance of assessing cancers for mutations as outstanding results were seen with therapies for NTRK, RET, ROS, and MSI-high driven tumors. In a debate on the role of molecular profiling, I had the opportunity to declare and support our position at Sarah Cannon that all patients with relapsed or metastatic cancers should have this testing performed. It will be through better understanding of the biology of these cancers that we will advance the field for all patients while sometimes finding a target or mutation that will dramatically change the life of a patient.

In keeping with the meeting’s theme, Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, the presentations and the discussions clearly demonstrated that through the use of precision medicine techniques such as prognostic gene assays and molecular profiling, patients can receive the best therapy, even “tailored” therapy, which may often actually be less therapy. It is an exciting time in cancer research, and I have never been more optimistic about the future of cancer treatment for our patients.

A record-setting 40,000-plus oncology professionals attended this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in Chicago. The outstanding education and scientific program, with the theme of Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, was planned and led by ASCO President Dr Bruce Johnson, professor and director of Thoracic Oncology at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and chaired by Sarah Cannon’s Dr David Spigel and Harvard’s Dr Ann Partridge. A recurring finding throughout the meeting was that “less is more” in several key areas of cancer therapy. From small molecules targeting driver mutations across various tumors to the application of immunotherapy in subsets of common cancers, it is clear that more patients are experiencing dramatic results from novel approaches.

A featured plenary session trial was TAILORx, a study of 10,273 women with hormone-receptor–positive, surgically resected breast cancer that had not spread to the lymph nodes, was less than 5 cm, and was not positive for the HER2 gene amplification. This clinical trial was sponsored by the NCI and initiated in 2006. It used the OncotypeDX genetic test to stratify patients into groups of low, intermediate, or high risk for recurrence. The low-risk patients received only hormonal therapy, and the high-risk patients were treated with hormonal therapy plus chemotherapy.

Dr Joseph Sparano, professor of Medicine and Women’s Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, presented the results from the group of 6,700 intermediate risk women who were randomized to receive hormonal therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. After 9 years of follow-up, 83.3% of the volunteers, as Dr Sparano appropriately referred to them, who were treated with hormonal therapy were still cancer free, compared with 84.3% of those who also received chemotherapy, demonstrating no statistical benefit for the addition of chemotherapy. Of note, breast cancer experts discussing the trial, including Dr Lisa Carey, professor of Breast Cancer Research at the UNC Lineberger Cancer Institute in Chapel Hill, urged that younger women, under the age of 50, with recurrence scores (RS) toward the higher end of the intermediate risk group (RS, 16-25) should still discuss and consider chemotherapy with their physicians. In summary, all patients fitting the study criteria with low (

These landmark and practice changing results mean that each year about 60,000 women in the United States will be spared the side effects of toxic drugs. These 10,273 study volunteers are true heroes to the women who will be diagnosed with breast cancer in coming years.

In the field of lung cancer, many new trial results using immunotherapy were presented, with the most talked about being single-agent pembrolizumab, a PD1 inhibitor, improving survival over traditional chemotherapy in patients with PD-L1 positive tumors, which comprise the majority of squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the lung. Also in the plenary, Dr Gilberto Lopes of the Sylvester Cancer Center at the University of Miami, presented these results from the KEYNOTE-042 study. In patients with PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of >1%, the benefit in overall survival (OS) of pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy was 16.7 versus 12.1 months, respectively (HR, 0.81). In those patients with a TPS of >20%, the OS benefit was 17.7 versus 1.0 months (HR, 0.77), and in the group with a TPS of >50%, the benefit was 20.0 versus 12.2 months (HR, 0.69). Overall, the quality of life and the occurrence of side effects were substantially better for those patients receiving immunotherapy alone. Other findings presented at the meeting demonstrated the benefit of adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy and of treating with combination immunotherapy (PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors). Many options now exist, much work remains to be done, and accrual to clinical trials is more important than ever.

Another plenary session trial evaluated the benefit of performing a nephrectomy in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a long-held and practiced standard of care. Dr Arnaud Mejean of Paris Descartes University presented findings from the CARMENA trial, which randomized 450 patients with metastatic clear cell RCC to receive cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by sunitinib, or sunitinib alone. The OS results of 18.4 versus 13.9 months, respectively (HR, 0.89) favored sunitinib alone in this noninferiority analysis. Other endpoints lined up in favor of not removing the cancerous kidney, and the presenter and discussants were united in their opinion of the results and the resulting change in doing less surgery in these patients.

In a step away from less therapy, the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study showed that adding 6 months of low-dose maintenance chemotherapy after standard intensive therapy improves survival in children with high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. The addition of a vinorelbine and cyclophosphamide low-dose regimen improved 5-year disease-free survival from 69.8% to 77.6% (HR, 0.68) and OS from 73.7% to 86.5% (HR, 0.52) as presented by Dr Gianni Bisogno, University of Padovani, Italy. The maintenance regimen showed no increase in toxicity and actually fewer infections were noted.

In the area of molecular profiling, multiple studies at the meeting demonstrated the importance of assessing cancers for mutations as outstanding results were seen with therapies for NTRK, RET, ROS, and MSI-high driven tumors. In a debate on the role of molecular profiling, I had the opportunity to declare and support our position at Sarah Cannon that all patients with relapsed or metastatic cancers should have this testing performed. It will be through better understanding of the biology of these cancers that we will advance the field for all patients while sometimes finding a target or mutation that will dramatically change the life of a patient.

In keeping with the meeting’s theme, Delivering Discoveries: Expanding the Reach of Precision Medicine, the presentations and the discussions clearly demonstrated that through the use of precision medicine techniques such as prognostic gene assays and molecular profiling, patients can receive the best therapy, even “tailored” therapy, which may often actually be less therapy. It is an exciting time in cancer research, and I have never been more optimistic about the future of cancer treatment for our patients.

The long-term effects of posttreatment exercise on pain in young women with breast cancer

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers in women worldwide, with more than 1 million new cases diagnosed annually.1 Prognosis for the disease has improved significantly, but 25% to 60% of women living with breast cancer experience some level of pain ranging from mild to severe, the nature of which can evolve from acute to chronic.2 Pre-, intra-, and post-treatment risk factors have been found to correlate with the development of acute and chronic pain and include young age, type of breast surgery (lumpectomy or total mastectomy), axillary node dissection, radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy.3-5 Chemotherapy, particularly anthracycline- and taxane-based regimens, has also been shown to induce pain, arthralgia, myalgia, and peripheral neuropathy during treatment.6 In particular, postradiation pain may result from subcutaneous fibrosis with fixation to underlying musculature and the development of fibrous flaps in the internal axilla.7 These tissue changes are commonly subclinical, occurring 4 to 12 months postradiation,8 and can progress undetected until pain and upper-limb disability develop.

The presence of persistent pain has a considerable impact on the quality of life in survivors of breast cancer: psychological distress is prevalent (anxiety, depression, worry, fear), the performance of daily activities is diminished (eg, bathing, dressing, preparing meals, shopping), and economic independence is compromised by the inability to work or reduced employment and income. These factors directly and indirectly contribute to an increase in the use of health care services.9,10

The management of pain is often characterized by pharmacologic-related treatment, such as the use of opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and nonpharmacologic-related treatment, such as exercise. Empirical evidence has shown that rehabilitative exercise programs, which commonly include a combination of resistance training and aerobic exercises, can effectively reduce pain in breast cancer survivors.10-12 Women living with breast cancer who are directed to rehabilitative exercise programs experience an improvement not only in pain levels but also in their ability to engage in activities of daily living, in their psychological health, and in their overall quality of life.13-15 However, despite evidence to support exercise programs to reduce pain related to breast cancer treatment, residual pain and upper-limb discomfort are common complaints in breast cancer survivors, and there is little focus on the duration of effectiveness of such programs for reducing pain after treatment for breast cancer. The objective of this study was to determine if an exercise program initiated postradiation would improve long-term pain levels in a carefully selected population of young women who were living with breast cancer and had no history of shoulder pathology or significant treatment complications.

Methods

Design

We used a pilot randomized control trial to compare the long-term effectiveness of a 12-week postradiation exercise program versus standard care on residual pain levels in young women (aged 18-45 years) living with breast cancer. The program was initiated 3 to 4 weeks postradiation to allow for acute inflammatory reactions to subside. Pain severity and interference were assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF), a tool for assessing cancer pain.16,17 Pain levels for isolated shoulder movements were also recorded on examination by a physical therapist. All measures were collected at 6 time points (T1-T6): postsurgery and preradiation (T1, baseline), postradiation and preintervention (T2), and 4 points during an 18-month period postradiation (T3-T6 at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months postradiation).

Sample

Young women living with breast cancer who met our eligibility criteria were identified from 2 clinics at the Jewish General Hospital – the Segal Cancer Center and the Department of Radiation Oncology in Montréal, Québec, Canada. Inclusion criteria included women with a diagnosis of stage I to stage III breast cancer, who were 18 to 45 years old, were scheduled for postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 or 1 (normal ambulatory function, minimal symptoms), and who consented to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included women with a metastatic (stage IV) diagnosis; significant musculoskeletal, cardiac, pulmonary, or metabolic comorbidities that would not allow for participation in physical activity; a previous breast cancer diagnosis with treatment to the ipsilateral or contralateral sides; postsurgical lymphedema; postsurgical capsulitis, tendonitis, or other shoulder inflammatory complications; and any contraindication to exercise. The recruitment goal was outlined as 50 patients per group; however, a protracted accrual time because of the stringent study criteria yielded a sample of 29 and 30 patients for the intervention and control groups, respectively, which was sufficient for significant testing of differences between the 2 study groups.18

Variables and measures

Clinical characteristics. We used standardized questions and chart review to document the participants’ clinical characteristics and to capture information on the following: the stage and subtype of breast cancer, hormonal and human epidermal growth factor receptors (HER2) (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 status), extent of surgery (lumpectomy or total mastectomy), and other modalities of treatment (eg, chemotherapy, radiation therapy).

Pain assessment. The BPI-SF was used to assess participants’ cancer-related pain. Pain severity ranged from 0 (no pain), 1 to 4 (mild pain), 5 to 6 (moderate pain), to 7 to 10 (severe pain).18,19 The questionnaire also identifies the pain interference in daily activities using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Does not interfere) to 10 (Completely interferes) in the following 7 domains or subscales: General Activity, Walking, Mood, Sleep, Work, Relations with Others, and Enjoyment of Life.16 For the purpose of this study, mean scores were tabulated using both pain intensity and interference scales.

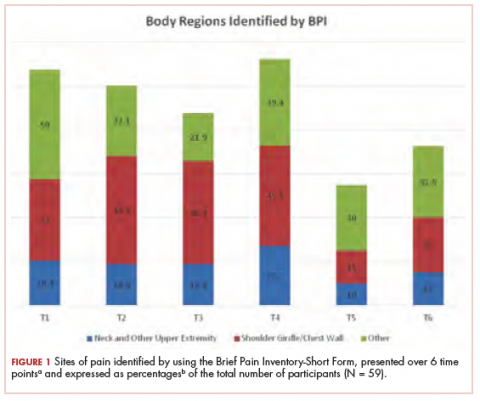

Another important component of the BPI-SF instructs participants to localize pain by means of a body diagram. For purpose of analysis, 3 pain regions were established: shoulder girdle/chest wall on the affected side; neck and other upper extremity, including hand(s), forearm(s), wrist(s), and finger(s); and other regions, including abdominal discomfort, leg(s), hip(s), knee(s), ankle(s), lower back, and feet. In addition, pain levels on movement (Yes/No) were recorded for isolated shoulder flexion, abduction, and horizontal abduction (sitting and standing). The measurements were completed by a single physical therapist throughout the course of the study to minimize variance.

Procedure

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Jewish General Hospital. Recruitment occurred from 2011 through 2015. The research was in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation. Eligible women were recruited by the research coordinator who described the purpose, risks, and benefits of the study; advised on confidentiality, data collection, and intervention allocation procedures; and highlighted voluntary participation. The research coordinator addressed any concerns on the part of the participants before obtaining their written informed consent. Random allocation to the intervention and control groups was established using a web-based randomization plan generator (www.randomization.com). A single individual was responsible for the randomization process, and treatment assignments were revealed after each participant’s name had been entered. A physical therapist performed 6 sequential evaluations (T1-T6) at the time of participants’ medical follow-up appointments.

Intervention

The 12-week exercise intervention started 3 weeks postradiation and was composed of an initial 6-week program of low-level cardiovascular and resistance exercises that progressed to a set of more advanced exercises for the remaining 6 weeks. Participants were instructed to warm up for at least 10 minutes with a cardiovascular exercise of their choice (eg, a recumbent cross trainer, walking, or stairs) before doing a combined strength, endurance, and stretching exercise program for the upper body.20 The final portion of the exercise intervention included a period of light cool-down. Weight training resistance levels were based on a maximum 8 to 10 repetitions for strength and a maximum of 20 repetitions for endurance training exercises, which progressed gradually over the course of the 12-week exercise program to ensure participant safety.21,22 Participants in the intervention group were supervised at least once a week by an exercise physiologist at a center for oncology patients (Hope & Cope Wellness Centre), and patients were encouraged to perform the program at home 2 to 3 times a week. Those who were not able to exercise consistently at the center were provided with equipment and instructed on how to do the program safely at home.

By comparison, the control group received standard care, which included advice on the benefits of an active lifestyle, including exercise, but without a specific intervention. Participants were not restricted in their physical activity and/or sport participation levels, and their weekly activity levels were calculated using the Metabolic Equivalent of Task and recorded at each of the 6 time points.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine participant characteristics. The quantitative data collected through the BPI-SF measures were analyzed with JMP software (version 11.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables were tested for statistical significance (P ≤ .05) through the chi-square (categorical), analysis of variance, and nonparametric Wilcoxon tests. The analyses did not include missing data.

Results

A total of 59 young women were randomized into the intervention (n = 29) and control (n = 30) groups. Of those, 2 participants dropped out of the study because of family and time constraints, and 3 participants died, 2 from the control and 1 from the intervention group, after subsequently developing metastatic disease. Baseline data including comparative tumor characteristics, surgical interventions, and treatment interventions have been published in relation to other elements of this study.23,24 The participants had a mean age of 39.2 years (standard deviation [SD], 5.0). More than half of them had an invasive ductal carcinoma (69.5%) and were estrogen positive (78.0%), progesterone positive (74.6%), or HER2 positive (20.3%), whereas 10.2% were triple negative. Most of the participants had undergone breast-sparing procedures (86.4% lumpectomy), and 18.6% had a total mastectomy. By random chance, the intervention group had higher rates of total mastectomy (24.4% and 13.3%, respectively) and surgical reconstruction (12.2% and 6.7%, respectively) compared with the control group. Most of the women (71.2%) received chemotherapy, and all received radiation therapy. In the intervention group, 37.2% received radiation therapy localized to the axilla, and 88% received a boost of radiation to the surgical bed. Self-reported exercise diaries were returned by 15 of the 29 intervention participants, and training frequencies among them varied significantly (1-6 times a week).

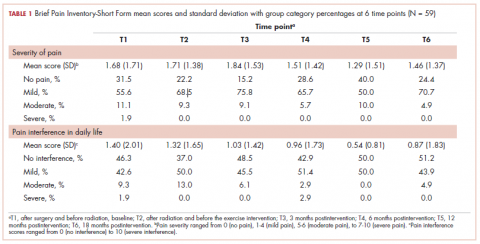

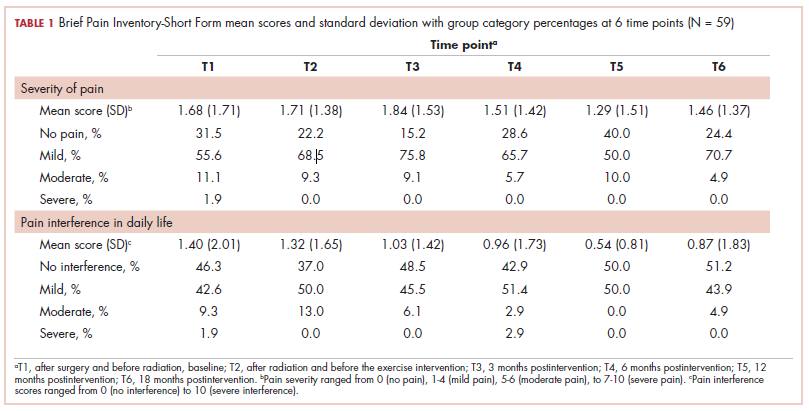

The findings showed that there was little variance between the intervention and control groups in BPI-SF severity scores from T1 to T6, so the means and SDs of the BPI-SF scores were grouped at 6 time points (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between baseline measures at T1 (1.68; SD, 1.17) and measures at 18 months postintervention (T6: 1.46; SD, 1.37). At baseline, 87.7% of the women reported no pain (31.5%) or mild levels of pain (55.6%), and 13% reported moderate or severe pain. Over the duration of the study from T1 to T6, these primarily low levels of pain (BPI-SF, 0-4) remained consistent with a favorable shift toward having no pain (T1: 31.5%; T6: 24.4%). By 18 months postintervention, 95.7% of women reported no or mild pain, with 4.9% reporting moderate pain.

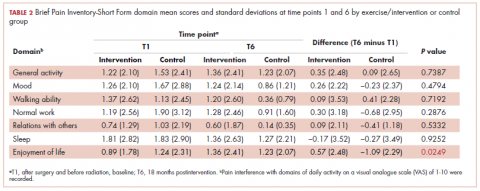

Similarly, there was little variance over time (T1-T6) and no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in BPI-SF–measured levels of pain interference in daily activities (Table 2). Moreover, a domain analysis showed that there were no statistically significant differences in pain interference scores when comparing the type and extent of surgery (total mastectomy: 0.59 [1.17]; lumpectomy: 0.94 [1.96]). By chance – and not related directly to the objectives of this study – there was a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups in the interference of pain on the Enjoyment of Life domain in favor of the control group.

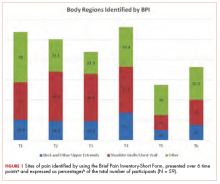

The sites of pain captured by the BPI-SF shed light on the preceding findings (Figure 1). At baseline (T1, postsurgery and preradiation), 37.0% of participants reported pain in the shoulder girdle–chest wall region, whereas 20.4% reported pain in the general neck–upper extremity region and 50% in other regions. Postradiation, shoulder girdle–chest wall pain was identified as the highest reported site of pain (49.1%; T2, postradiation and preintervention) and remained elevated at 3 months (T3) and 6 months (T4) postradiation (46.9% and 45.5%, respectively). At 12 and 18 months postradiation (T5 and T6), the principal focus of pain shifted once again to “other” regions at 30% and 32.5%, respectively, and the neck–upper extremity region at 10% and 15%, respectively. Shoulder girdle–chest wall pain concomitantly improved at those time points (15% and 25% respectively) but was not eliminated.

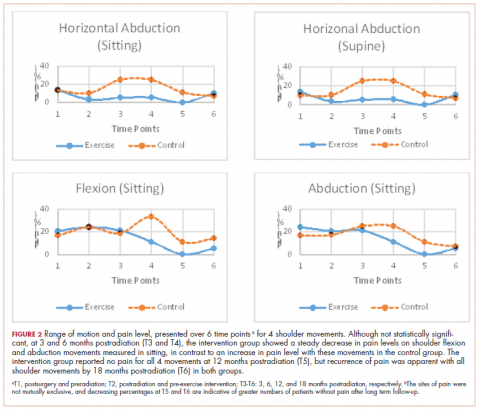

Pain levels recorded on physical examination for isolated shoulder range of movements were recently published,24 and they have been abbreviated and reproduced in this paper (Figure 2) to allow for a comparison of findings between the exercise intervention group and the control group to help determine the sensitivity of these tools for use in breast cancer patients. At baseline, pain levels with active movement were noted to be slightly greater in the intervention group for flexion and abduction.

Following the intervention, at 3 and 6 months postradiation (T3 and T4), the intervention group showed a steady decrease in pain levels in flexion and abduction, whereas the control group showed a 5-fold increase in pain with horizontal abduction. Furthermore, participants in the intervention group reported having no pain on movement 12 months postradiation (T5); however, recurrence of pain was apparent with all shoulder movements by 18 months postradiation (T6) in both the intervention and control groups.

Discussion

Previous studies have hypothesized that younger age (18-39 years), adjuvant radiotherapy, and axillary node dissection are risk factors for chronic pain in breast cancer survivors.22,25 Persistent pain is prevalent in 12% to 51% of breast cancer survivors, with up to one-third experiencing some pain more than 5 years after treatment,26,27 and our study outcomes concur with those findings. In our study, pain, as measured by the BPI-SF, was found to persist for most participants (75.6%) after the 18-month follow-up. The results of our trial showed that a 12-week exercise intervention administered postsurgery and postradiation had no statistically significant effect on long-term (18 months) pain severity and its interference in daily life. It is worth noting that body regions that had not been directly related to either surgical or radiation treatment for breast cancer were commonly identified as areas of pain but were not specifically targeted by our intervention. However, focusing on pain severity (BPI-SF), our findings suggest that the benefits of targeted upper-extremity exercise on pain in the intermediate time course of follow-up (T3, T4, and T5) was notable compared with the control group, which received standard care. The apparent recurrence of pain at 18 months in both groups was not anticipated and needs to be further investigated.

More specific objective assessments of pain on active shoulder movement identified distinct patterns of pain that could not be isolated using the BPI-SF alone. The incidence and localization of pain on movement differed between the population of women who received a specific exercise intervention and those who received standard care (Figure 2). Patterns of pain over time fluctuated in the control group, whereas the intervention group reported a linear decrease in pain. Residual pain on shoulder movement remained apparent in both groups at 18-months postradiation, but that finding was not reflected in the BPI-SF results. The literature supports our findings on persistent pain among breast cancer survivors,3,7,8,28-30 and in our study of young women carefully screened and excluded for pre-existent shoulder conditions or comorbid medical conditions, recurrent articular pain was nonetheless prevalent. It seems that unidentified or multiple factors may be part of the etiology of pain in this young adult cohort.

Although the BPI-SF is a generic measurement tool commonly used to assess and measure cancer patients’ pain levels, the lack of variance in our BPI-SF severity and interference outcomes over time (T1-T6) (Table 1, Table 2), the variety of “other” unrelated regions (Figure 1) identified by the BPI-SF, and the contrast in our findings on specific physical examination emphasize the potential limitations of this clinical tool.

Moreover, the BPI-SF has not been validated specifically for breast cancer. Harrington and colleagues have recommended using the BPI-SF to assess pain in women with breast cancer,31 but the use of a more multidimensional measurement tool that evaluates axillary, chest, trunk, and upper-limb pain may prove to be more valuable in this population.

Limitations

Recruitment of young adult women was difficult because of our stringent inclusion criteria, the long-term follow-up, and the relatively small population of breast cancer patients in this age demographic. Therefore, the duration of the recruitment phase, despite our having access to a specialized young adult and adolescent clinic in our institute, greatly surpassed the expectations we had when we designed the study. In addition, there remains an inherent bias in participants who accept participation in a study that includes exercise interventions. Potential participants who exercise regularly or have a positive inclination toward doing exercise are more likely to participate. Despite the prescription of a targeted 12-week upper-limb intervention in this study, the general activity levels of both groups may have had an impact on the significance of this study. In addition, the low adherence to the use of self-reported logs failed to capture the true compliance rates of our participants because their lack of tracking does not indicate failure to comply with the program. The use of weekly or biweekly telephone calls to monitor compliance rates of activity more vigilantly may be used in future studies.

Conclusions

Advances in clinical management of breast cancer have improved survival outcomes, and morbidity over recent years, yet symptoms such as pain remain prevalent in this population. The results of this study showed that a targeted, 12-week upper-limb exercise intervention postradiation transiently improved levels of shoulder pain without a concomitant impact on chronic pain or any positive influence on activities of daily living 18 months posttreatment. Furthermore, future studies should use a variety of measurement tools to evaluate trunk and upper-limb pain in women with breast cancer and investigate the optimal timing of postradiation exercise interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hope & Cope, the CURE foundation, and the Jewish General Hospital Foundation/Weekend to End Breast Cancer for providing the financial resources needed to sustain this research study. They also thank the McGill Adolescent and Young Adult program for its continued support. Previous oral presentations of research Muanza TM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a progressive exercise program for young women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93(3):s35-s36.

1. World Health Organization. Breast cancer: prevention and control. www.who.int/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/. Updated 2017. Accessed September 16, 2016.

2. Andersen KG, Kehlet H. Persistent pain after breast cancer treatment: a critical review of risk factors and strategies for prevention. J Pain. 2011;12(7):725-746.

3. Ernst MF, Voogd AC, Balder W, Klinkenbijl JH, Roukema JA. Early and late morbidity associated with axillary levels I-III dissection in breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002;79(3):151-155; discussion 156.

4. Gulluoglu BM, Cingi A, Cakir T, Gercek A, Barlas A, Eti Z. Factors related to post-treatment chronic pain in breast cancer survivors: the interference of pain with life functions. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2006;51(2):75-82.

5. Jung BF, Ahrendt GM, Oaklander AL, Dworkin RH. Neuropathic pain following breast cancer surgery: proposed classification and research update. Pain. 2003;104(1-2):1-13.

6. Saibil S, Fitzgerald B, Freedman OC, et al. Incidence of taxane-induced pain and distress in patients receiving chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer: a retrospective, outcomes-based survey. Curr Oncol. 2010;17(4):42-47.

7. Tengrup I, Tennvall-Nittby L, Christiansson I, Laurin M. Arm morbidity after breast-conserving therapy for breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(3):393-397.

8. Johansen J, Overgaard J, Blichert-Toft M, Overgaard M. Treatment of morbidity associated with the management of the axilla in breast-conserving therapy. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(3):349-354.

9. Mittmann N, Porter JM, Rangrej J, et al. Health system costs for stage-specific breast cancer: a population-based approach. Curr Oncol. 2014;21(6):281-293.

10. Page A. Keeping patients safe: transforming the work environment of nurses. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

11. McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, et al. Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD005211. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005211.pub2

12. Wong P, Muanza T, Hijal T, et al. Effect of exercise in reducing breast and chest-wall pain in patients with breast cancer: a pilot study. Curr Oncol. 2012;19(3):e129-e135.

13. Fernández-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, del Moral-Ávila R, Castro-Sánchez AM, Arroyo-Morales M. Effectiveness of a multidimensional physical therapy program on pain, pressure hypersensitivity, and trigger points in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(2):113-121.

14. Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, Jones LW, Field CJ, Fairey AS. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(9):1660-1668.

15. Segal R, Evans W, Johnson D, et al. Structured exercise improves physical functioning in women with stages I and II breast cancer: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):657-665.

16. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129-138.

17. Kumar SP. Utilization of Brief Pain Inventory as an assessment tool for pain in patients with cancer: a focused review. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17(2):108-115.

18. Van Voorhis CRW, Morgan BL. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2007;3(2):43-50.

19. Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61(2):277-284.

20. Lee TS, Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM, Pendlebury SC, Beith JM, Lee MJ. Pectoral stretching program for women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102(3):313-321.

21. Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409-1426.

22. Pollock ML, Gaesser GA, Butcher JD, et al. ACSM position stand: the recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(6):975-991.

23. Ibrahim M, Muanza T, Smirnow N, et al. Time course of upper limb function and return-to-work post-radiotherapy in young adults with breast cancer: a pilot randomized control trial on effects of targeted exercise program. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(6):791-799.

24. Ibrahim M, Muanza T, Smirnow N, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial on the effects of a progressive exercise program on the range of motion and upper extremity grip strength in young adults with breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(1):e55-e64.

25. Gärtner R, Jensen MB, Nielsen J, Ewertz M, Kroman N, Kehlet H. Prevalence of and factors associated with persistent pain following breast cancer surgery. JAMA. 2009;302(18):1985-1992.

26. Hayes SC, Johansson K, Stout NL, et al. Upper-body morbidity after breast cancer: incidence and evidence for evaluation, prevention, and management within a prospective surveillance model of care. Cancer. 2012;118(suppl 8):2237-2249.

27. Kärki A, Simonen R, Mälkiä E, Selfe J. Impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions 6 and 12 months after breast cancer operation. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(3):180-188.

28. Katz J, Poleshuck EL, Andrus CH, et al. Risk factors for acute pain and its persistence following breast cancer surgery. Pain. 2005;119(1-3):16-25.

29. Tasmuth T, von Smitten K, Hietanen P, Kataja M, Kalso E. Pain and other symptoms after different treatment modalities of breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1995;6(5):453-459.

30. Whelan TJ, Levine M, Julian J, Kirkbride P, Skingley P. The effects of radiation therapy on quality of life of women with breast carcinoma: results of a randomized trial. Ontario Clinical Oncology Group. Cancer. 2000;88(10):2260-2266.

31. Harrington S, Gilchrist L, Sander A. Breast cancer EDGE task force outcomes: clinical measures of pain. Rehabil Oncol. 2014;32(1):13-21.

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers in women worldwide, with more than 1 million new cases diagnosed annually.1 Prognosis for the disease has improved significantly, but 25% to 60% of women living with breast cancer experience some level of pain ranging from mild to severe, the nature of which can evolve from acute to chronic.2 Pre-, intra-, and post-treatment risk factors have been found to correlate with the development of acute and chronic pain and include young age, type of breast surgery (lumpectomy or total mastectomy), axillary node dissection, radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy.3-5 Chemotherapy, particularly anthracycline- and taxane-based regimens, has also been shown to induce pain, arthralgia, myalgia, and peripheral neuropathy during treatment.6 In particular, postradiation pain may result from subcutaneous fibrosis with fixation to underlying musculature and the development of fibrous flaps in the internal axilla.7 These tissue changes are commonly subclinical, occurring 4 to 12 months postradiation,8 and can progress undetected until pain and upper-limb disability develop.

The presence of persistent pain has a considerable impact on the quality of life in survivors of breast cancer: psychological distress is prevalent (anxiety, depression, worry, fear), the performance of daily activities is diminished (eg, bathing, dressing, preparing meals, shopping), and economic independence is compromised by the inability to work or reduced employment and income. These factors directly and indirectly contribute to an increase in the use of health care services.9,10

The management of pain is often characterized by pharmacologic-related treatment, such as the use of opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and nonpharmacologic-related treatment, such as exercise. Empirical evidence has shown that rehabilitative exercise programs, which commonly include a combination of resistance training and aerobic exercises, can effectively reduce pain in breast cancer survivors.10-12 Women living with breast cancer who are directed to rehabilitative exercise programs experience an improvement not only in pain levels but also in their ability to engage in activities of daily living, in their psychological health, and in their overall quality of life.13-15 However, despite evidence to support exercise programs to reduce pain related to breast cancer treatment, residual pain and upper-limb discomfort are common complaints in breast cancer survivors, and there is little focus on the duration of effectiveness of such programs for reducing pain after treatment for breast cancer. The objective of this study was to determine if an exercise program initiated postradiation would improve long-term pain levels in a carefully selected population of young women who were living with breast cancer and had no history of shoulder pathology or significant treatment complications.

Methods

Design

We used a pilot randomized control trial to compare the long-term effectiveness of a 12-week postradiation exercise program versus standard care on residual pain levels in young women (aged 18-45 years) living with breast cancer. The program was initiated 3 to 4 weeks postradiation to allow for acute inflammatory reactions to subside. Pain severity and interference were assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF), a tool for assessing cancer pain.16,17 Pain levels for isolated shoulder movements were also recorded on examination by a physical therapist. All measures were collected at 6 time points (T1-T6): postsurgery and preradiation (T1, baseline), postradiation and preintervention (T2), and 4 points during an 18-month period postradiation (T3-T6 at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months postradiation).

Sample

Young women living with breast cancer who met our eligibility criteria were identified from 2 clinics at the Jewish General Hospital – the Segal Cancer Center and the Department of Radiation Oncology in Montréal, Québec, Canada. Inclusion criteria included women with a diagnosis of stage I to stage III breast cancer, who were 18 to 45 years old, were scheduled for postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 or 1 (normal ambulatory function, minimal symptoms), and who consented to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included women with a metastatic (stage IV) diagnosis; significant musculoskeletal, cardiac, pulmonary, or metabolic comorbidities that would not allow for participation in physical activity; a previous breast cancer diagnosis with treatment to the ipsilateral or contralateral sides; postsurgical lymphedema; postsurgical capsulitis, tendonitis, or other shoulder inflammatory complications; and any contraindication to exercise. The recruitment goal was outlined as 50 patients per group; however, a protracted accrual time because of the stringent study criteria yielded a sample of 29 and 30 patients for the intervention and control groups, respectively, which was sufficient for significant testing of differences between the 2 study groups.18

Variables and measures

Clinical characteristics. We used standardized questions and chart review to document the participants’ clinical characteristics and to capture information on the following: the stage and subtype of breast cancer, hormonal and human epidermal growth factor receptors (HER2) (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 status), extent of surgery (lumpectomy or total mastectomy), and other modalities of treatment (eg, chemotherapy, radiation therapy).

Pain assessment. The BPI-SF was used to assess participants’ cancer-related pain. Pain severity ranged from 0 (no pain), 1 to 4 (mild pain), 5 to 6 (moderate pain), to 7 to 10 (severe pain).18,19 The questionnaire also identifies the pain interference in daily activities using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Does not interfere) to 10 (Completely interferes) in the following 7 domains or subscales: General Activity, Walking, Mood, Sleep, Work, Relations with Others, and Enjoyment of Life.16 For the purpose of this study, mean scores were tabulated using both pain intensity and interference scales.

Another important component of the BPI-SF instructs participants to localize pain by means of a body diagram. For purpose of analysis, 3 pain regions were established: shoulder girdle/chest wall on the affected side; neck and other upper extremity, including hand(s), forearm(s), wrist(s), and finger(s); and other regions, including abdominal discomfort, leg(s), hip(s), knee(s), ankle(s), lower back, and feet. In addition, pain levels on movement (Yes/No) were recorded for isolated shoulder flexion, abduction, and horizontal abduction (sitting and standing). The measurements were completed by a single physical therapist throughout the course of the study to minimize variance.

Procedure

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Jewish General Hospital. Recruitment occurred from 2011 through 2015. The research was in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation. Eligible women were recruited by the research coordinator who described the purpose, risks, and benefits of the study; advised on confidentiality, data collection, and intervention allocation procedures; and highlighted voluntary participation. The research coordinator addressed any concerns on the part of the participants before obtaining their written informed consent. Random allocation to the intervention and control groups was established using a web-based randomization plan generator (www.randomization.com). A single individual was responsible for the randomization process, and treatment assignments were revealed after each participant’s name had been entered. A physical therapist performed 6 sequential evaluations (T1-T6) at the time of participants’ medical follow-up appointments.

Intervention

The 12-week exercise intervention started 3 weeks postradiation and was composed of an initial 6-week program of low-level cardiovascular and resistance exercises that progressed to a set of more advanced exercises for the remaining 6 weeks. Participants were instructed to warm up for at least 10 minutes with a cardiovascular exercise of their choice (eg, a recumbent cross trainer, walking, or stairs) before doing a combined strength, endurance, and stretching exercise program for the upper body.20 The final portion of the exercise intervention included a period of light cool-down. Weight training resistance levels were based on a maximum 8 to 10 repetitions for strength and a maximum of 20 repetitions for endurance training exercises, which progressed gradually over the course of the 12-week exercise program to ensure participant safety.21,22 Participants in the intervention group were supervised at least once a week by an exercise physiologist at a center for oncology patients (Hope & Cope Wellness Centre), and patients were encouraged to perform the program at home 2 to 3 times a week. Those who were not able to exercise consistently at the center were provided with equipment and instructed on how to do the program safely at home.

By comparison, the control group received standard care, which included advice on the benefits of an active lifestyle, including exercise, but without a specific intervention. Participants were not restricted in their physical activity and/or sport participation levels, and their weekly activity levels were calculated using the Metabolic Equivalent of Task and recorded at each of the 6 time points.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine participant characteristics. The quantitative data collected through the BPI-SF measures were analyzed with JMP software (version 11.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables were tested for statistical significance (P ≤ .05) through the chi-square (categorical), analysis of variance, and nonparametric Wilcoxon tests. The analyses did not include missing data.

Results

A total of 59 young women were randomized into the intervention (n = 29) and control (n = 30) groups. Of those, 2 participants dropped out of the study because of family and time constraints, and 3 participants died, 2 from the control and 1 from the intervention group, after subsequently developing metastatic disease. Baseline data including comparative tumor characteristics, surgical interventions, and treatment interventions have been published in relation to other elements of this study.23,24 The participants had a mean age of 39.2 years (standard deviation [SD], 5.0). More than half of them had an invasive ductal carcinoma (69.5%) and were estrogen positive (78.0%), progesterone positive (74.6%), or HER2 positive (20.3%), whereas 10.2% were triple negative. Most of the participants had undergone breast-sparing procedures (86.4% lumpectomy), and 18.6% had a total mastectomy. By random chance, the intervention group had higher rates of total mastectomy (24.4% and 13.3%, respectively) and surgical reconstruction (12.2% and 6.7%, respectively) compared with the control group. Most of the women (71.2%) received chemotherapy, and all received radiation therapy. In the intervention group, 37.2% received radiation therapy localized to the axilla, and 88% received a boost of radiation to the surgical bed. Self-reported exercise diaries were returned by 15 of the 29 intervention participants, and training frequencies among them varied significantly (1-6 times a week).

The findings showed that there was little variance between the intervention and control groups in BPI-SF severity scores from T1 to T6, so the means and SDs of the BPI-SF scores were grouped at 6 time points (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference between baseline measures at T1 (1.68; SD, 1.17) and measures at 18 months postintervention (T6: 1.46; SD, 1.37). At baseline, 87.7% of the women reported no pain (31.5%) or mild levels of pain (55.6%), and 13% reported moderate or severe pain. Over the duration of the study from T1 to T6, these primarily low levels of pain (BPI-SF, 0-4) remained consistent with a favorable shift toward having no pain (T1: 31.5%; T6: 24.4%). By 18 months postintervention, 95.7% of women reported no or mild pain, with 4.9% reporting moderate pain.

Similarly, there was little variance over time (T1-T6) and no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in BPI-SF–measured levels of pain interference in daily activities (Table 2). Moreover, a domain analysis showed that there were no statistically significant differences in pain interference scores when comparing the type and extent of surgery (total mastectomy: 0.59 [1.17]; lumpectomy: 0.94 [1.96]). By chance – and not related directly to the objectives of this study – there was a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups in the interference of pain on the Enjoyment of Life domain in favor of the control group.

The sites of pain captured by the BPI-SF shed light on the preceding findings (Figure 1). At baseline (T1, postsurgery and preradiation), 37.0% of participants reported pain in the shoulder girdle–chest wall region, whereas 20.4% reported pain in the general neck–upper extremity region and 50% in other regions. Postradiation, shoulder girdle–chest wall pain was identified as the highest reported site of pain (49.1%; T2, postradiation and preintervention) and remained elevated at 3 months (T3) and 6 months (T4) postradiation (46.9% and 45.5%, respectively). At 12 and 18 months postradiation (T5 and T6), the principal focus of pain shifted once again to “other” regions at 30% and 32.5%, respectively, and the neck–upper extremity region at 10% and 15%, respectively. Shoulder girdle–chest wall pain concomitantly improved at those time points (15% and 25% respectively) but was not eliminated.

Pain levels recorded on physical examination for isolated shoulder range of movements were recently published,24 and they have been abbreviated and reproduced in this paper (Figure 2) to allow for a comparison of findings between the exercise intervention group and the control group to help determine the sensitivity of these tools for use in breast cancer patients. At baseline, pain levels with active movement were noted to be slightly greater in the intervention group for flexion and abduction.

Following the intervention, at 3 and 6 months postradiation (T3 and T4), the intervention group showed a steady decrease in pain levels in flexion and abduction, whereas the control group showed a 5-fold increase in pain with horizontal abduction. Furthermore, participants in the intervention group reported having no pain on movement 12 months postradiation (T5); however, recurrence of pain was apparent with all shoulder movements by 18 months postradiation (T6) in both the intervention and control groups.

Discussion

Previous studies have hypothesized that younger age (18-39 years), adjuvant radiotherapy, and axillary node dissection are risk factors for chronic pain in breast cancer survivors.22,25 Persistent pain is prevalent in 12% to 51% of breast cancer survivors, with up to one-third experiencing some pain more than 5 years after treatment,26,27 and our study outcomes concur with those findings. In our study, pain, as measured by the BPI-SF, was found to persist for most participants (75.6%) after the 18-month follow-up. The results of our trial showed that a 12-week exercise intervention administered postsurgery and postradiation had no statistically significant effect on long-term (18 months) pain severity and its interference in daily life. It is worth noting that body regions that had not been directly related to either surgical or radiation treatment for breast cancer were commonly identified as areas of pain but were not specifically targeted by our intervention. However, focusing on pain severity (BPI-SF), our findings suggest that the benefits of targeted upper-extremity exercise on pain in the intermediate time course of follow-up (T3, T4, and T5) was notable compared with the control group, which received standard care. The apparent recurrence of pain at 18 months in both groups was not anticipated and needs to be further investigated.

More specific objective assessments of pain on active shoulder movement identified distinct patterns of pain that could not be isolated using the BPI-SF alone. The incidence and localization of pain on movement differed between the population of women who received a specific exercise intervention and those who received standard care (Figure 2). Patterns of pain over time fluctuated in the control group, whereas the intervention group reported a linear decrease in pain. Residual pain on shoulder movement remained apparent in both groups at 18-months postradiation, but that finding was not reflected in the BPI-SF results. The literature supports our findings on persistent pain among breast cancer survivors,3,7,8,28-30 and in our study of young women carefully screened and excluded for pre-existent shoulder conditions or comorbid medical conditions, recurrent articular pain was nonetheless prevalent. It seems that unidentified or multiple factors may be part of the etiology of pain in this young adult cohort.

Although the BPI-SF is a generic measurement tool commonly used to assess and measure cancer patients’ pain levels, the lack of variance in our BPI-SF severity and interference outcomes over time (T1-T6) (Table 1, Table 2), the variety of “other” unrelated regions (Figure 1) identified by the BPI-SF, and the contrast in our findings on specific physical examination emphasize the potential limitations of this clinical tool.

Moreover, the BPI-SF has not been validated specifically for breast cancer. Harrington and colleagues have recommended using the BPI-SF to assess pain in women with breast cancer,31 but the use of a more multidimensional measurement tool that evaluates axillary, chest, trunk, and upper-limb pain may prove to be more valuable in this population.

Limitations

Recruitment of young adult women was difficult because of our stringent inclusion criteria, the long-term follow-up, and the relatively small population of breast cancer patients in this age demographic. Therefore, the duration of the recruitment phase, despite our having access to a specialized young adult and adolescent clinic in our institute, greatly surpassed the expectations we had when we designed the study. In addition, there remains an inherent bias in participants who accept participation in a study that includes exercise interventions. Potential participants who exercise regularly or have a positive inclination toward doing exercise are more likely to participate. Despite the prescription of a targeted 12-week upper-limb intervention in this study, the general activity levels of both groups may have had an impact on the significance of this study. In addition, the low adherence to the use of self-reported logs failed to capture the true compliance rates of our participants because their lack of tracking does not indicate failure to comply with the program. The use of weekly or biweekly telephone calls to monitor compliance rates of activity more vigilantly may be used in future studies.

Conclusions

Advances in clinical management of breast cancer have improved survival outcomes, and morbidity over recent years, yet symptoms such as pain remain prevalent in this population. The results of this study showed that a targeted, 12-week upper-limb exercise intervention postradiation transiently improved levels of shoulder pain without a concomitant impact on chronic pain or any positive influence on activities of daily living 18 months posttreatment. Furthermore, future studies should use a variety of measurement tools to evaluate trunk and upper-limb pain in women with breast cancer and investigate the optimal timing of postradiation exercise interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hope & Cope, the CURE foundation, and the Jewish General Hospital Foundation/Weekend to End Breast Cancer for providing the financial resources needed to sustain this research study. They also thank the McGill Adolescent and Young Adult program for its continued support. Previous oral presentations of research Muanza TM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a progressive exercise program for young women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93(3):s35-s36.

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers in women worldwide, with more than 1 million new cases diagnosed annually.1 Prognosis for the disease has improved significantly, but 25% to 60% of women living with breast cancer experience some level of pain ranging from mild to severe, the nature of which can evolve from acute to chronic.2 Pre-, intra-, and post-treatment risk factors have been found to correlate with the development of acute and chronic pain and include young age, type of breast surgery (lumpectomy or total mastectomy), axillary node dissection, radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy.3-5 Chemotherapy, particularly anthracycline- and taxane-based regimens, has also been shown to induce pain, arthralgia, myalgia, and peripheral neuropathy during treatment.6 In particular, postradiation pain may result from subcutaneous fibrosis with fixation to underlying musculature and the development of fibrous flaps in the internal axilla.7 These tissue changes are commonly subclinical, occurring 4 to 12 months postradiation,8 and can progress undetected until pain and upper-limb disability develop.

The presence of persistent pain has a considerable impact on the quality of life in survivors of breast cancer: psychological distress is prevalent (anxiety, depression, worry, fear), the performance of daily activities is diminished (eg, bathing, dressing, preparing meals, shopping), and economic independence is compromised by the inability to work or reduced employment and income. These factors directly and indirectly contribute to an increase in the use of health care services.9,10

The management of pain is often characterized by pharmacologic-related treatment, such as the use of opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and nonpharmacologic-related treatment, such as exercise. Empirical evidence has shown that rehabilitative exercise programs, which commonly include a combination of resistance training and aerobic exercises, can effectively reduce pain in breast cancer survivors.10-12 Women living with breast cancer who are directed to rehabilitative exercise programs experience an improvement not only in pain levels but also in their ability to engage in activities of daily living, in their psychological health, and in their overall quality of life.13-15 However, despite evidence to support exercise programs to reduce pain related to breast cancer treatment, residual pain and upper-limb discomfort are common complaints in breast cancer survivors, and there is little focus on the duration of effectiveness of such programs for reducing pain after treatment for breast cancer. The objective of this study was to determine if an exercise program initiated postradiation would improve long-term pain levels in a carefully selected population of young women who were living with breast cancer and had no history of shoulder pathology or significant treatment complications.

Methods

Design

We used a pilot randomized control trial to compare the long-term effectiveness of a 12-week postradiation exercise program versus standard care on residual pain levels in young women (aged 18-45 years) living with breast cancer. The program was initiated 3 to 4 weeks postradiation to allow for acute inflammatory reactions to subside. Pain severity and interference were assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF), a tool for assessing cancer pain.16,17 Pain levels for isolated shoulder movements were also recorded on examination by a physical therapist. All measures were collected at 6 time points (T1-T6): postsurgery and preradiation (T1, baseline), postradiation and preintervention (T2), and 4 points during an 18-month period postradiation (T3-T6 at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months postradiation).

Sample