User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Establishing Financial Literacy: What Every Resident Needs to Know

The average debt of graduating medical students today is $190,000, which has increased from $32,000 since 1986 (or the equivalent of $70,000 in 2017 dollars when adjusted for inflation).1 This fact is especially disconcerting given that medical trainees and professionals are not known for being financially sophisticated, and rising levels of high-interest educational debt, increasing years of training, and stagnant or decreasing physician salaries make this status quo untenable.2 Building foundational financial literacy and establishing good financial practices should start during medical school and residency; these basics are a crucial component of long-term job satisfaction and professional resilience.

One prominent physician finance writer advocates that residents should consider the following 5 big-ticket financial steps: acquire life and disability insurance, open a Roth IRA, engage yearly in some type of financial education, and learn about billing and coding in your specialty.3 These exercises, except life insurance for a resident without dependents, are all nonnegotiable, yet alone are insufficient actions to build a solid financial foundation. The purpose of this article is to address additional steps every resident should take, including establishing a workable budget, learning how and why to calculate net worth yearly, determining what percentage of income to save for retirement and basic investing strategies, and managing student loans.

Establish a Workable Budget

Living on a budget is a form of reality acceptance. It may feel impossible to save or budget on a resident salary, but residents earn approximately the median US household income of $59,039, according to the US Census Bureau from September 2017.4,5 There are many tools that can be used to create a budget and to track monthly expenses. However, the simplest way to budget is to pay yourself first with automatic deductions to retirement and savings accounts as well as automated bill payments. Making a habit of reviewing all expenses at the end of every month allows you to see if expenditures remain aligned to your personal values and to reallocate funds for the upcoming month if they are not.

Calculate Net Worth Yearly

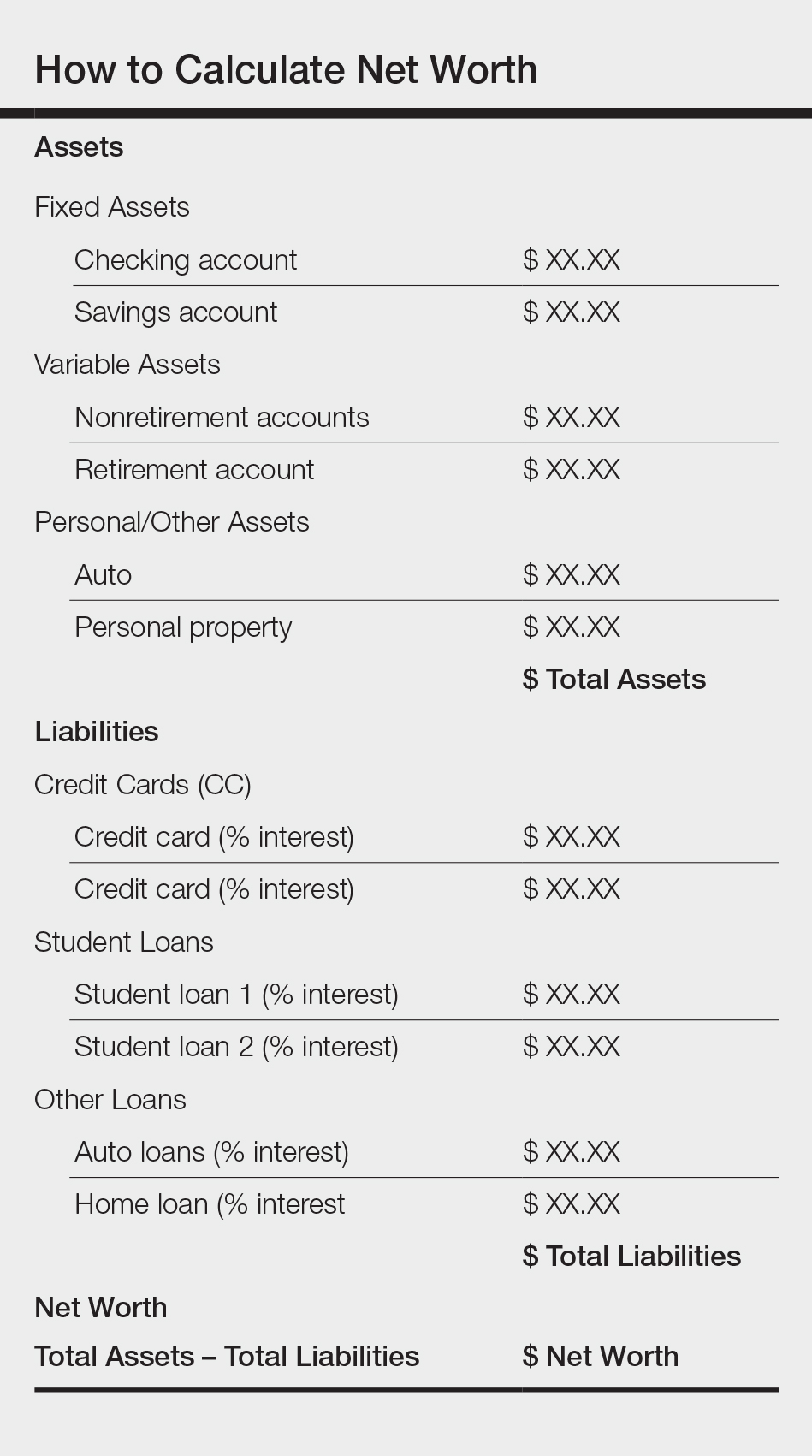

Calculating personal net worth may appear to be a discouraging activity to advocate for residents, as many will have a negative 6-figure net worth. The purpose is two-fold: Firstly, to compel you to become well acquainted with your varying types of debt and their respective interest rates. Secondly, similar to taking serial photographs of vitiligo patients to monitor for improvement, it may be the only thing in a long slow slog that indicates beneficial change is occurring because small daily efforts over time yield surprisingly impressive results and the calculation factors in both debt repayment and contributions to all savings vehicles. An example of a simplified method to calculate net worth is demonstrated in the Table.

Understand Your Retirement Account and Asset Distribution

Contributing to a retirement account should start day 1 of intern year. A simple rule of thumb to estimate how much money you need to save for retirement is to divide how much you expect to spend on a yearly basis by 4%. For example, if you anticipate spending $80,000 per year during retirement, you will need $2 million in savings (0.04×$2,000,000=$80,000). The amount saved depends on the aggressiveness of your financial goals, but it should be a minimum of 10% to 15% of income during residency and at least 20% afterwards. This strategy allows even a resident to save $25,000 to $50,000 over a 4-year period (depending on employer match), which can accrue additional value in the stock market. One advantage of contributing to an employer-based retirement account, which usually is a 403(b) plan for residents, is that it lowers your tax burden for the year because the savings are tax deferred, in contrast to a Roth IRA, which is funded with posttax dollars. Roth accounts often are recommended for residents because contributions are made during a period in which the physician is presumably in the lowest tax bracket, as account earnings and withdrawals from a Roth IRA after 59.5 years of age, when most physicians expect to be in a higher tax bracket, are tax free. Another advantage of contributing to a 403(b) account is that many residency programs offer a match, which provides for an immediate and substantial return on invested money. Because most residents do not have the cash flow to fully fund both a Roth IRA and 403(b) account (2018 contribution limits are $5500 and $18,500, respectively),6,7 one strategy to utilize both is to save enough to the 403(b) to capture the employer match and place whatever additional savings you can afford into the Roth IRA.

Many different investment strategies exist, and a thorough discussion of them is beyond the scope of this article. Simply speaking, there are 4 major asset classes in which to invest: US stocks, foreign stocks, real estate, and bonds. The variation of recommended contributions to each asset is limitless, and every resident should spend time considering the best strategy for his/her goals. One example of a simple effective investing strategy is to utilize index funds, which track the market and therefore rise with the market, as they tend to go up (at least historically, though temporary setbacks occur).8 If you are investing in funds available through your employer-sponsored retirement account, examine the funds you are automatically assigned and their associated fee and expense ratio (ER) disclosures, which are typically available through the online portal. A general rule of thumb is that good funds have ERs of less than 0.5% and bad funds have ERs greater than 1% and additional associated fees. The funds available to you also can be researched on the Morningstar, Inc, website (www.morningstar.com). My institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) offers a variety of options with ERs varying from 0.02% to 1.02%. The difference in the costs associated with these funds over decades is notable, and it pays (literally) to understand the nuances. Reallocation of funds usually can be done easily online and are effective within 24 hours.

Student Loans

Although many residents agonize most over management of student loans, the simple solution is do not defer them. Refinancing federal loans with a private company versus enrolling in an income-based repayment program depends on many factors, including whether you have a high-earning spouse, how many dependents you have, and whether you expect to stay in academia and will be eligible for Public Service Loan Forgiveness, among others. Look critically at your situation and likely future employment to decide what is most appropriate for you; doing so can save you thousands of dollars in interest over the course of your residency.

Final Thoughts

To the detriment of residents and the attending physicians they will become, discussing financial matters in medicine remains rare, perhaps because it seems to shift what should be the singular focus of our profession, namely to help the sick, to thoughts of personal gain, which is a false dichotomy. Unquestionably, the physician’s role that supersedes all others is to care for the patient and to honor the oath we all took: “Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick.” But this commitment should not preclude the mastery of financial concepts that promote personal and professional health and well-being. After all, the joy in work is maximized when you are not enslaved to it.

Your reading assignment, paper revision, or presentation can wait. Making time to understand your current financial health, to build your own financial literacy, and to plan for your future is an important component of a long satisfying career. Start now.

- Grischkan J, George BP, Chaiyachati K, et al. Distribution of medical education debt by specialty, 2010-2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1532-1535.

- Ahmad FA, White AJ, Hiller KM, et al. An assessment of residents’ and fellows’ personal finance literacy: an unmet medical education need. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:192-204.

- The five big money items you should do as a resident. The White Coat Investor website. https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/the-five-big-money-items-you-should-do-as-a-resident. Published July 7, 2011. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Income, poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2016. United States Census Bureau website. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/income-povery.html. Published September 12, 2017. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Levy S. Residents salary and debt report 2017. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/residents-salary-and-debt-report-2017-6008931. Published July 26, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Retirement topics - IRA contribution limits. Internal Revenue Service website. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-ira-contribution-limits. Updated October 20, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Retirement plan FAQs regarding 403(b) tax-sheltered annuity plans. Internal Revenue Service website. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/retirement-plans-faqs-regarding-403b-tax-sheltered-annuity-plans#conts. Updated November 14, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Collins JL. Stock series. JLCollins website. http://jlcollinsnh.com/stock-series/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

The average debt of graduating medical students today is $190,000, which has increased from $32,000 since 1986 (or the equivalent of $70,000 in 2017 dollars when adjusted for inflation).1 This fact is especially disconcerting given that medical trainees and professionals are not known for being financially sophisticated, and rising levels of high-interest educational debt, increasing years of training, and stagnant or decreasing physician salaries make this status quo untenable.2 Building foundational financial literacy and establishing good financial practices should start during medical school and residency; these basics are a crucial component of long-term job satisfaction and professional resilience.

One prominent physician finance writer advocates that residents should consider the following 5 big-ticket financial steps: acquire life and disability insurance, open a Roth IRA, engage yearly in some type of financial education, and learn about billing and coding in your specialty.3 These exercises, except life insurance for a resident without dependents, are all nonnegotiable, yet alone are insufficient actions to build a solid financial foundation. The purpose of this article is to address additional steps every resident should take, including establishing a workable budget, learning how and why to calculate net worth yearly, determining what percentage of income to save for retirement and basic investing strategies, and managing student loans.

Establish a Workable Budget

Living on a budget is a form of reality acceptance. It may feel impossible to save or budget on a resident salary, but residents earn approximately the median US household income of $59,039, according to the US Census Bureau from September 2017.4,5 There are many tools that can be used to create a budget and to track monthly expenses. However, the simplest way to budget is to pay yourself first with automatic deductions to retirement and savings accounts as well as automated bill payments. Making a habit of reviewing all expenses at the end of every month allows you to see if expenditures remain aligned to your personal values and to reallocate funds for the upcoming month if they are not.

Calculate Net Worth Yearly

Calculating personal net worth may appear to be a discouraging activity to advocate for residents, as many will have a negative 6-figure net worth. The purpose is two-fold: Firstly, to compel you to become well acquainted with your varying types of debt and their respective interest rates. Secondly, similar to taking serial photographs of vitiligo patients to monitor for improvement, it may be the only thing in a long slow slog that indicates beneficial change is occurring because small daily efforts over time yield surprisingly impressive results and the calculation factors in both debt repayment and contributions to all savings vehicles. An example of a simplified method to calculate net worth is demonstrated in the Table.

Understand Your Retirement Account and Asset Distribution

Contributing to a retirement account should start day 1 of intern year. A simple rule of thumb to estimate how much money you need to save for retirement is to divide how much you expect to spend on a yearly basis by 4%. For example, if you anticipate spending $80,000 per year during retirement, you will need $2 million in savings (0.04×$2,000,000=$80,000). The amount saved depends on the aggressiveness of your financial goals, but it should be a minimum of 10% to 15% of income during residency and at least 20% afterwards. This strategy allows even a resident to save $25,000 to $50,000 over a 4-year period (depending on employer match), which can accrue additional value in the stock market. One advantage of contributing to an employer-based retirement account, which usually is a 403(b) plan for residents, is that it lowers your tax burden for the year because the savings are tax deferred, in contrast to a Roth IRA, which is funded with posttax dollars. Roth accounts often are recommended for residents because contributions are made during a period in which the physician is presumably in the lowest tax bracket, as account earnings and withdrawals from a Roth IRA after 59.5 years of age, when most physicians expect to be in a higher tax bracket, are tax free. Another advantage of contributing to a 403(b) account is that many residency programs offer a match, which provides for an immediate and substantial return on invested money. Because most residents do not have the cash flow to fully fund both a Roth IRA and 403(b) account (2018 contribution limits are $5500 and $18,500, respectively),6,7 one strategy to utilize both is to save enough to the 403(b) to capture the employer match and place whatever additional savings you can afford into the Roth IRA.

Many different investment strategies exist, and a thorough discussion of them is beyond the scope of this article. Simply speaking, there are 4 major asset classes in which to invest: US stocks, foreign stocks, real estate, and bonds. The variation of recommended contributions to each asset is limitless, and every resident should spend time considering the best strategy for his/her goals. One example of a simple effective investing strategy is to utilize index funds, which track the market and therefore rise with the market, as they tend to go up (at least historically, though temporary setbacks occur).8 If you are investing in funds available through your employer-sponsored retirement account, examine the funds you are automatically assigned and their associated fee and expense ratio (ER) disclosures, which are typically available through the online portal. A general rule of thumb is that good funds have ERs of less than 0.5% and bad funds have ERs greater than 1% and additional associated fees. The funds available to you also can be researched on the Morningstar, Inc, website (www.morningstar.com). My institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) offers a variety of options with ERs varying from 0.02% to 1.02%. The difference in the costs associated with these funds over decades is notable, and it pays (literally) to understand the nuances. Reallocation of funds usually can be done easily online and are effective within 24 hours.

Student Loans

Although many residents agonize most over management of student loans, the simple solution is do not defer them. Refinancing federal loans with a private company versus enrolling in an income-based repayment program depends on many factors, including whether you have a high-earning spouse, how many dependents you have, and whether you expect to stay in academia and will be eligible for Public Service Loan Forgiveness, among others. Look critically at your situation and likely future employment to decide what is most appropriate for you; doing so can save you thousands of dollars in interest over the course of your residency.

Final Thoughts

To the detriment of residents and the attending physicians they will become, discussing financial matters in medicine remains rare, perhaps because it seems to shift what should be the singular focus of our profession, namely to help the sick, to thoughts of personal gain, which is a false dichotomy. Unquestionably, the physician’s role that supersedes all others is to care for the patient and to honor the oath we all took: “Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick.” But this commitment should not preclude the mastery of financial concepts that promote personal and professional health and well-being. After all, the joy in work is maximized when you are not enslaved to it.

Your reading assignment, paper revision, or presentation can wait. Making time to understand your current financial health, to build your own financial literacy, and to plan for your future is an important component of a long satisfying career. Start now.

The average debt of graduating medical students today is $190,000, which has increased from $32,000 since 1986 (or the equivalent of $70,000 in 2017 dollars when adjusted for inflation).1 This fact is especially disconcerting given that medical trainees and professionals are not known for being financially sophisticated, and rising levels of high-interest educational debt, increasing years of training, and stagnant or decreasing physician salaries make this status quo untenable.2 Building foundational financial literacy and establishing good financial practices should start during medical school and residency; these basics are a crucial component of long-term job satisfaction and professional resilience.

One prominent physician finance writer advocates that residents should consider the following 5 big-ticket financial steps: acquire life and disability insurance, open a Roth IRA, engage yearly in some type of financial education, and learn about billing and coding in your specialty.3 These exercises, except life insurance for a resident without dependents, are all nonnegotiable, yet alone are insufficient actions to build a solid financial foundation. The purpose of this article is to address additional steps every resident should take, including establishing a workable budget, learning how and why to calculate net worth yearly, determining what percentage of income to save for retirement and basic investing strategies, and managing student loans.

Establish a Workable Budget

Living on a budget is a form of reality acceptance. It may feel impossible to save or budget on a resident salary, but residents earn approximately the median US household income of $59,039, according to the US Census Bureau from September 2017.4,5 There are many tools that can be used to create a budget and to track monthly expenses. However, the simplest way to budget is to pay yourself first with automatic deductions to retirement and savings accounts as well as automated bill payments. Making a habit of reviewing all expenses at the end of every month allows you to see if expenditures remain aligned to your personal values and to reallocate funds for the upcoming month if they are not.

Calculate Net Worth Yearly

Calculating personal net worth may appear to be a discouraging activity to advocate for residents, as many will have a negative 6-figure net worth. The purpose is two-fold: Firstly, to compel you to become well acquainted with your varying types of debt and their respective interest rates. Secondly, similar to taking serial photographs of vitiligo patients to monitor for improvement, it may be the only thing in a long slow slog that indicates beneficial change is occurring because small daily efforts over time yield surprisingly impressive results and the calculation factors in both debt repayment and contributions to all savings vehicles. An example of a simplified method to calculate net worth is demonstrated in the Table.

Understand Your Retirement Account and Asset Distribution

Contributing to a retirement account should start day 1 of intern year. A simple rule of thumb to estimate how much money you need to save for retirement is to divide how much you expect to spend on a yearly basis by 4%. For example, if you anticipate spending $80,000 per year during retirement, you will need $2 million in savings (0.04×$2,000,000=$80,000). The amount saved depends on the aggressiveness of your financial goals, but it should be a minimum of 10% to 15% of income during residency and at least 20% afterwards. This strategy allows even a resident to save $25,000 to $50,000 over a 4-year period (depending on employer match), which can accrue additional value in the stock market. One advantage of contributing to an employer-based retirement account, which usually is a 403(b) plan for residents, is that it lowers your tax burden for the year because the savings are tax deferred, in contrast to a Roth IRA, which is funded with posttax dollars. Roth accounts often are recommended for residents because contributions are made during a period in which the physician is presumably in the lowest tax bracket, as account earnings and withdrawals from a Roth IRA after 59.5 years of age, when most physicians expect to be in a higher tax bracket, are tax free. Another advantage of contributing to a 403(b) account is that many residency programs offer a match, which provides for an immediate and substantial return on invested money. Because most residents do not have the cash flow to fully fund both a Roth IRA and 403(b) account (2018 contribution limits are $5500 and $18,500, respectively),6,7 one strategy to utilize both is to save enough to the 403(b) to capture the employer match and place whatever additional savings you can afford into the Roth IRA.

Many different investment strategies exist, and a thorough discussion of them is beyond the scope of this article. Simply speaking, there are 4 major asset classes in which to invest: US stocks, foreign stocks, real estate, and bonds. The variation of recommended contributions to each asset is limitless, and every resident should spend time considering the best strategy for his/her goals. One example of a simple effective investing strategy is to utilize index funds, which track the market and therefore rise with the market, as they tend to go up (at least historically, though temporary setbacks occur).8 If you are investing in funds available through your employer-sponsored retirement account, examine the funds you are automatically assigned and their associated fee and expense ratio (ER) disclosures, which are typically available through the online portal. A general rule of thumb is that good funds have ERs of less than 0.5% and bad funds have ERs greater than 1% and additional associated fees. The funds available to you also can be researched on the Morningstar, Inc, website (www.morningstar.com). My institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) offers a variety of options with ERs varying from 0.02% to 1.02%. The difference in the costs associated with these funds over decades is notable, and it pays (literally) to understand the nuances. Reallocation of funds usually can be done easily online and are effective within 24 hours.

Student Loans

Although many residents agonize most over management of student loans, the simple solution is do not defer them. Refinancing federal loans with a private company versus enrolling in an income-based repayment program depends on many factors, including whether you have a high-earning spouse, how many dependents you have, and whether you expect to stay in academia and will be eligible for Public Service Loan Forgiveness, among others. Look critically at your situation and likely future employment to decide what is most appropriate for you; doing so can save you thousands of dollars in interest over the course of your residency.

Final Thoughts

To the detriment of residents and the attending physicians they will become, discussing financial matters in medicine remains rare, perhaps because it seems to shift what should be the singular focus of our profession, namely to help the sick, to thoughts of personal gain, which is a false dichotomy. Unquestionably, the physician’s role that supersedes all others is to care for the patient and to honor the oath we all took: “Into whatsoever houses I enter, I will enter to help the sick.” But this commitment should not preclude the mastery of financial concepts that promote personal and professional health and well-being. After all, the joy in work is maximized when you are not enslaved to it.

Your reading assignment, paper revision, or presentation can wait. Making time to understand your current financial health, to build your own financial literacy, and to plan for your future is an important component of a long satisfying career. Start now.

- Grischkan J, George BP, Chaiyachati K, et al. Distribution of medical education debt by specialty, 2010-2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1532-1535.

- Ahmad FA, White AJ, Hiller KM, et al. An assessment of residents’ and fellows’ personal finance literacy: an unmet medical education need. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:192-204.

- The five big money items you should do as a resident. The White Coat Investor website. https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/the-five-big-money-items-you-should-do-as-a-resident. Published July 7, 2011. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Income, poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2016. United States Census Bureau website. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/income-povery.html. Published September 12, 2017. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Levy S. Residents salary and debt report 2017. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/residents-salary-and-debt-report-2017-6008931. Published July 26, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Retirement topics - IRA contribution limits. Internal Revenue Service website. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-ira-contribution-limits. Updated October 20, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Retirement plan FAQs regarding 403(b) tax-sheltered annuity plans. Internal Revenue Service website. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/retirement-plans-faqs-regarding-403b-tax-sheltered-annuity-plans#conts. Updated November 14, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Collins JL. Stock series. JLCollins website. http://jlcollinsnh.com/stock-series/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Grischkan J, George BP, Chaiyachati K, et al. Distribution of medical education debt by specialty, 2010-2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1532-1535.

- Ahmad FA, White AJ, Hiller KM, et al. An assessment of residents’ and fellows’ personal finance literacy: an unmet medical education need. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:192-204.

- The five big money items you should do as a resident. The White Coat Investor website. https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/the-five-big-money-items-you-should-do-as-a-resident. Published July 7, 2011. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Income, poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2016. United States Census Bureau website. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/income-povery.html. Published September 12, 2017. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Levy S. Residents salary and debt report 2017. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/residents-salary-and-debt-report-2017-6008931. Published July 26, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Retirement topics - IRA contribution limits. Internal Revenue Service website. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-ira-contribution-limits. Updated October 20, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Retirement plan FAQs regarding 403(b) tax-sheltered annuity plans. Internal Revenue Service website. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/retirement-plans-faqs-regarding-403b-tax-sheltered-annuity-plans#conts. Updated November 14, 2017. Accessed May 22, 2018.

- Collins JL. Stock series. JLCollins website. http://jlcollinsnh.com/stock-series/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

Solitary Angiokeratoma of the Vulva Mimicking Malignant Melanoma

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

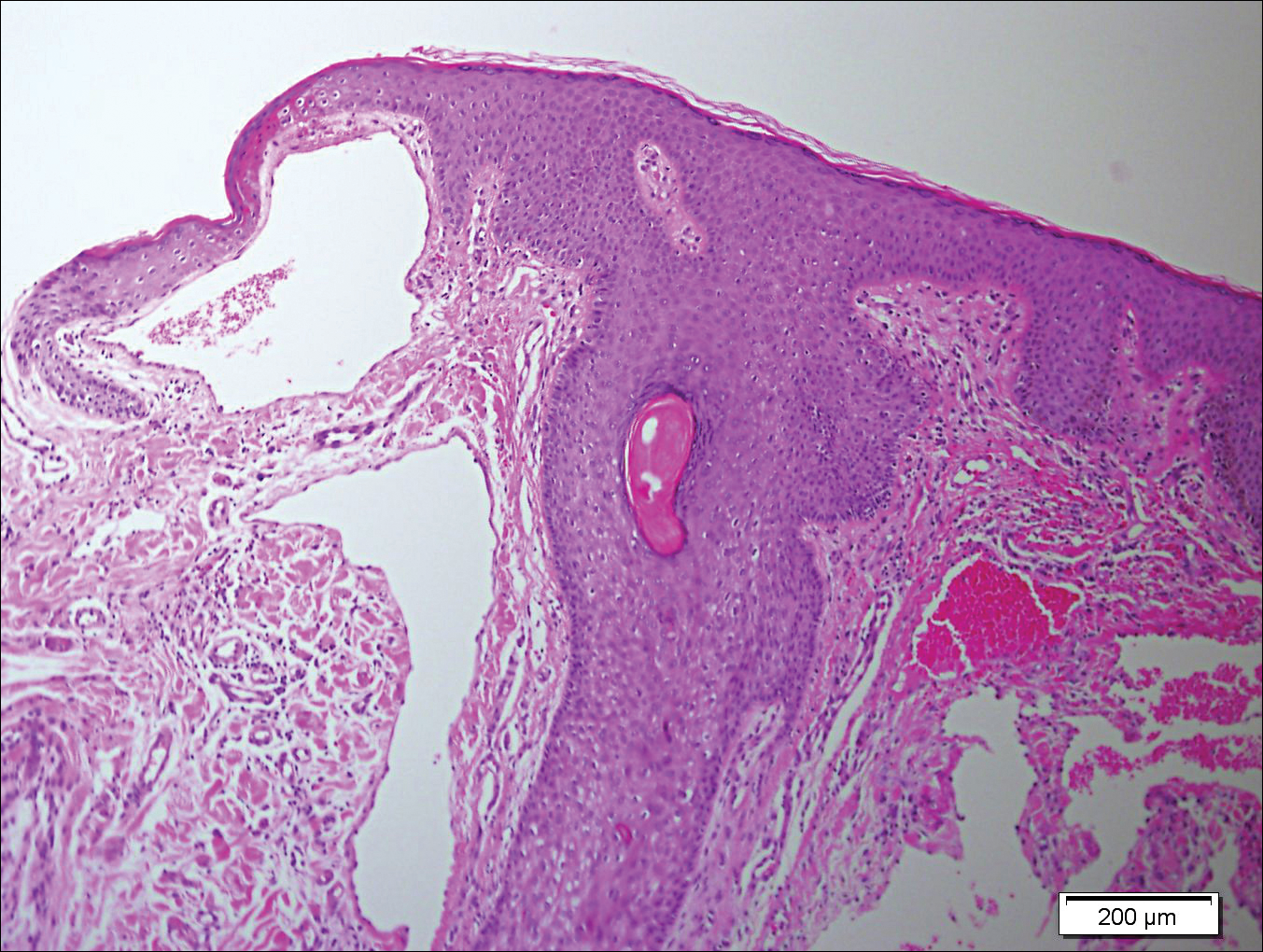

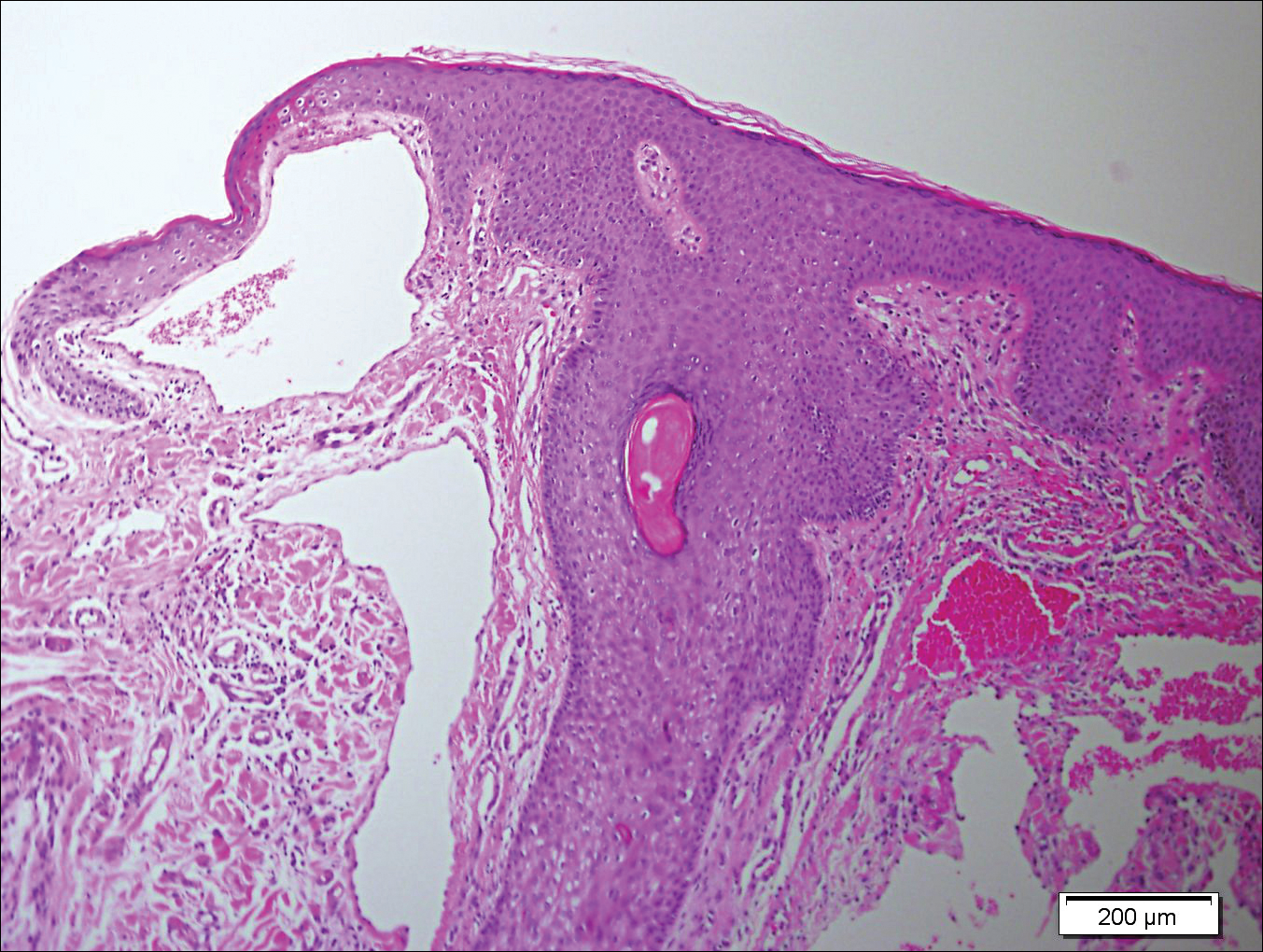

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. part I. hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

- Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

- Gomi H, Eriyama Y, Horikawa E, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma. J Dermatol. 1988;15:349-350.

- Yamazaki M, Hiruma M, Irie H, et al. Angiokeratoma of the clitoris: a subtype of angiokeratoma vulvae. J Dermatol. 1992;19:553-555.

- Cohen PR, Young AW Jr, Tovell HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:339-346.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:296-301.

- De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:127-133.

- Novick NL. Angiokeratoma vulvae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:561-563.

- Yigiter M, Arda IS, Tosun E, et al. Angiokeratoma of clitoris: a rare lesion in an adolescent girl. Urology. 2008;71:604-606.

- Zaballos P, Daufi C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

To the Editor:

Angiokeratoma is a benign vascular tumor characterized by several dilated vessels in the superficial dermis accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.1 Angiokeratoma of the vulva is a rare clinical finding, usually involving multiple lesions as part of the Fordyce type.2 Solitary angiokeratoma occurs predominantly on the lower legs,3 and although other locations have been described, the presence of a solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva is rare.4 We report 2 cases of solitary angiokeratoma on the vulva that was misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma. Both patients were referred to our center for evaluation and excision.

A 65-year-old woman (patient 1) and a 67-year-old woman (patient 2) presented with a bluish black, growing, asymptomatic lesion on the right (Figure 1) and left labia majora, respectively. Both patients were referred by outside physicians for excision because of suspected malignant melanoma. Physical examinations revealed bluish black globular nodules that measured 0.5 and 0.3 cm in diameter, respectively. Dermoscopy (patient 1) revealed dark lacunae. Histopathologic examination of the vulvar lesion (patient 2) showed dilated, blood-filled, vascular spaces in the papillary dermis, accompanied by overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis that was consistent with angiokeratoma (Figure 2).

Angiokeratoma, particularly the solitary type, often is misdiagnosed. Clinical differential diagnoses may include a wide range of pathologic conditions, including condyloma acuminata, basal cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, lymphangioma, nevi, condyloma lata, nodular prurigo, seborrheic keratosis, granuloma inguinale, and deep fungal infection.2,5 However, due to its quickly growing nature and its dark complexion, malignant melanoma often is initially diagnosed. Because patients affected by angiokeratoma of the vulva usually are aged 20 to 40 years,5 and vulvar melanoma is typical for middle-aged women (median age, 68 years),6 this misdiagnosis is more likely in older patients. It should be noted that a high index of suspicion for melanoma often is present when examining the vulva, considering that this area is difficult to monitor, and there is an especially poor prognosis of vulvar melanoma due to its late detection.6,7

In the past, biopsy was considered mandatory for confirming the diagnosis of vulvar angiokeratoma.5,8,9 However, dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for diagnosis of angiokeratoma10 and also was helpful as a diagnostic aid in one of our patients (patient 1). Therefore, we believe that dermoscopy should be performed prior to a biopsy of angiokeratomas of the vulva.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. part I. hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

- Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

- Gomi H, Eriyama Y, Horikawa E, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma. J Dermatol. 1988;15:349-350.

- Yamazaki M, Hiruma M, Irie H, et al. Angiokeratoma of the clitoris: a subtype of angiokeratoma vulvae. J Dermatol. 1992;19:553-555.

- Cohen PR, Young AW Jr, Tovell HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:339-346.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:296-301.

- De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:127-133.

- Novick NL. Angiokeratoma vulvae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:561-563.

- Yigiter M, Arda IS, Tosun E, et al. Angiokeratoma of clitoris: a rare lesion in an adolescent girl. Urology. 2008;71:604-606.

- Zaballos P, Daufi C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. part I. hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:523-549.

- Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282.

- Gomi H, Eriyama Y, Horikawa E, et al. Solitary angiokeratoma. J Dermatol. 1988;15:349-350.

- Yamazaki M, Hiruma M, Irie H, et al. Angiokeratoma of the clitoris: a subtype of angiokeratoma vulvae. J Dermatol. 1992;19:553-555.

- Cohen PR, Young AW Jr, Tovell HM. Angiokeratoma of the vulva: diagnosis and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:339-346.

- Sugiyama VE, Chan JK, Shin JY, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a multivariable analysis of 644 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:296-301.

- De Simone P, Silipo V, Buccini P, et al. Vulvar melanoma: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2008;18:127-133.

- Novick NL. Angiokeratoma vulvae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:561-563.

- Yigiter M, Arda IS, Tosun E, et al. Angiokeratoma of clitoris: a rare lesion in an adolescent girl. Urology. 2008;71:604-606.

- Zaballos P, Daufi C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318-325.

Practice Points

- Solitary angiokeratoma of the vulva often is misdiagnosed as malignant melanoma due to its rapid growth and dark color.

- Dermoscopy is a valuable tool for diagnosing vulvar angiokeratoma to avoid unnecessary excisions.

Carotenoderma Associated With a Diet Rich in Red Palm Oil

To the Editor:

Carotenoderma is a cutaneous manifestation of elevated serum β-carotene levels and classically localizes to fatty tissues and areas rich in sweat glands. We present a case of carotenoderma associated with a diet rich in red palm oil, a common food additive in parts of the world outside of the United States.

A previously healthy 8-year-old boy who recently immigrated to the United States from Liberia was hospitalized for treatment of a febrile illness that subsequently was attributed to a viral syndrome. On physical examination by the dermatology department, the patient was noted to have marked orange discoloration on the palms and soles (Figure). Laboratory workup revealed elevated serum β-carotene levels of 809 μg/dL (reference range, 10–85 μg/dL). Testing of hemoglobin/hematocrit levels and liver, thyroid, and kidney function was normal, and systemic examination revealed no further abnormalities. Upon further inquiry by the dermatology department, the patient’s family reported frequent addition of red palm oil to all of the child’s meals. The patient subsequently was diagnosed with carotenoderma and was instructed to limit inclusion of red palm oil in his diet.

Red palm oil is a rich source of β-carotene and is commonly used outside the United States as a dietary supplement or food flavoring. Excessive consumption of red palm oil or other sources rich in carotenes can result in elevated serum carotene levels or hypercarotenemia. An elevation in serum β-carotene levels may be recognized from 4 to 7 weeks after starting a β-carotene–rich diet.1

While dietary consumption of carotenes is the most common cause of carotenoderma, others include kidney or liver disease, hyperlipidemia, porphyria, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and anorexia nervosa.2-4 Moreover, since carotenoids are enzymatically converted to vitamin A in the small intestine, a mutation of the gene of the conversion enzyme β-carotene 15,15’-monooxygenase 1 (BCMO1) also can cause be a rare cause of hypercarotenemia.3

Carotenoderma, the clinical cutaneous manifestation of hypercarotenemia, occurs as a result of β-carotene deposits in the skin when serum concentration exceeds 250 μg/dL. More specifically, β-carotene accumulates mainly in the lipid-rich stratum corneum as well as in sweat and sebum, which explains the localized discoloration in fatty tissues and areas rich in sweat glands (eg, nasolabial folds, palms, soles).3,4 The sclerae of the eyes are not affected by the surplus of β-carotene in carotenoderma, which helps distinguish it from jaundice.5

The differential diagnosis of yellow discoloration of the skin includes jaundice, encompassing the prehepatic, hepatocellular, and posthepatic categories.4 Also noteworthy in the differential diagnosis is lycopenemia, which occurs as a result of eating lycopene-rich foods (eg, tomatoes), resulting in a deeper orange-yellow pigmentation when compared to the cutaneous manifestation of hypercarotenemia.2,4,6 Several drugs also have been reported to induce yellow discoloration of the skin, including sunitinib,7 sorafenib,8 quinacrine, saffron supplements, santonin, fluorescein, 2,4-dinitrophenol, canthaxanthin, tetryl and picric acids, and acriflavine.2,4

Carotenoderma caused by a diet rich in β-carotene is a benign condition in which a diet low in β-carotene is implicated for treatment. Contrary to popular belief, vitamin A toxicity does not occur in the presence of a surplus of β-carotenes because the enzymatic conversion of β-carotene to vitamin A is strictly regulated.9 Although acknowledging the various causes of carotenoderma is important, a simple history and laboratory testing for elevated serum β-carotene levels can eliminate further unnecessary testing and allow for prompt recognition of the condition. Appropriate dietary modifications also may be warranted.

- Roe DA. Assessment of risk factors for carotenodermia and cutaneous signs of hypervitaminosis A in college-aged populations. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:303-308.

- Manolios N, Samaras K. Hypercarotenaemia. Intern Med J. 2006;36:534.

- Wageesha ND, Ekanayake S, Jansz ER, et al. Studies on hypercarotenemia due to excessive ingestion of carrot, pumpkin and papaw [published online September 27, 2010]. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62:20-25.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

- Maruani A, Labarthe F, Dupré T, et al. Hypercarotenaemia in an infant [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:32-35.

- Shaw JA, Koti M. Clinical images. CMAJ. 2009;180:895.

- Vignand-Courtin C, Martin C, Le Beller C, et al. Cutaneous side effects associated with sunitinib: an analysis of 8 cases. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:286-289.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT, Dutcher J. Yellow skin discoloration associated with sorafenib use for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. South Med J. 2007;100:328-330.

- Lascari AD. Carotenemia. a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20:25-29.

To the Editor:

Carotenoderma is a cutaneous manifestation of elevated serum β-carotene levels and classically localizes to fatty tissues and areas rich in sweat glands. We present a case of carotenoderma associated with a diet rich in red palm oil, a common food additive in parts of the world outside of the United States.

A previously healthy 8-year-old boy who recently immigrated to the United States from Liberia was hospitalized for treatment of a febrile illness that subsequently was attributed to a viral syndrome. On physical examination by the dermatology department, the patient was noted to have marked orange discoloration on the palms and soles (Figure). Laboratory workup revealed elevated serum β-carotene levels of 809 μg/dL (reference range, 10–85 μg/dL). Testing of hemoglobin/hematocrit levels and liver, thyroid, and kidney function was normal, and systemic examination revealed no further abnormalities. Upon further inquiry by the dermatology department, the patient’s family reported frequent addition of red palm oil to all of the child’s meals. The patient subsequently was diagnosed with carotenoderma and was instructed to limit inclusion of red palm oil in his diet.

Red palm oil is a rich source of β-carotene and is commonly used outside the United States as a dietary supplement or food flavoring. Excessive consumption of red palm oil or other sources rich in carotenes can result in elevated serum carotene levels or hypercarotenemia. An elevation in serum β-carotene levels may be recognized from 4 to 7 weeks after starting a β-carotene–rich diet.1

While dietary consumption of carotenes is the most common cause of carotenoderma, others include kidney or liver disease, hyperlipidemia, porphyria, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and anorexia nervosa.2-4 Moreover, since carotenoids are enzymatically converted to vitamin A in the small intestine, a mutation of the gene of the conversion enzyme β-carotene 15,15’-monooxygenase 1 (BCMO1) also can cause be a rare cause of hypercarotenemia.3

Carotenoderma, the clinical cutaneous manifestation of hypercarotenemia, occurs as a result of β-carotene deposits in the skin when serum concentration exceeds 250 μg/dL. More specifically, β-carotene accumulates mainly in the lipid-rich stratum corneum as well as in sweat and sebum, which explains the localized discoloration in fatty tissues and areas rich in sweat glands (eg, nasolabial folds, palms, soles).3,4 The sclerae of the eyes are not affected by the surplus of β-carotene in carotenoderma, which helps distinguish it from jaundice.5

The differential diagnosis of yellow discoloration of the skin includes jaundice, encompassing the prehepatic, hepatocellular, and posthepatic categories.4 Also noteworthy in the differential diagnosis is lycopenemia, which occurs as a result of eating lycopene-rich foods (eg, tomatoes), resulting in a deeper orange-yellow pigmentation when compared to the cutaneous manifestation of hypercarotenemia.2,4,6 Several drugs also have been reported to induce yellow discoloration of the skin, including sunitinib,7 sorafenib,8 quinacrine, saffron supplements, santonin, fluorescein, 2,4-dinitrophenol, canthaxanthin, tetryl and picric acids, and acriflavine.2,4

Carotenoderma caused by a diet rich in β-carotene is a benign condition in which a diet low in β-carotene is implicated for treatment. Contrary to popular belief, vitamin A toxicity does not occur in the presence of a surplus of β-carotenes because the enzymatic conversion of β-carotene to vitamin A is strictly regulated.9 Although acknowledging the various causes of carotenoderma is important, a simple history and laboratory testing for elevated serum β-carotene levels can eliminate further unnecessary testing and allow for prompt recognition of the condition. Appropriate dietary modifications also may be warranted.

To the Editor:

Carotenoderma is a cutaneous manifestation of elevated serum β-carotene levels and classically localizes to fatty tissues and areas rich in sweat glands. We present a case of carotenoderma associated with a diet rich in red palm oil, a common food additive in parts of the world outside of the United States.

A previously healthy 8-year-old boy who recently immigrated to the United States from Liberia was hospitalized for treatment of a febrile illness that subsequently was attributed to a viral syndrome. On physical examination by the dermatology department, the patient was noted to have marked orange discoloration on the palms and soles (Figure). Laboratory workup revealed elevated serum β-carotene levels of 809 μg/dL (reference range, 10–85 μg/dL). Testing of hemoglobin/hematocrit levels and liver, thyroid, and kidney function was normal, and systemic examination revealed no further abnormalities. Upon further inquiry by the dermatology department, the patient’s family reported frequent addition of red palm oil to all of the child’s meals. The patient subsequently was diagnosed with carotenoderma and was instructed to limit inclusion of red palm oil in his diet.

Red palm oil is a rich source of β-carotene and is commonly used outside the United States as a dietary supplement or food flavoring. Excessive consumption of red palm oil or other sources rich in carotenes can result in elevated serum carotene levels or hypercarotenemia. An elevation in serum β-carotene levels may be recognized from 4 to 7 weeks after starting a β-carotene–rich diet.1

While dietary consumption of carotenes is the most common cause of carotenoderma, others include kidney or liver disease, hyperlipidemia, porphyria, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and anorexia nervosa.2-4 Moreover, since carotenoids are enzymatically converted to vitamin A in the small intestine, a mutation of the gene of the conversion enzyme β-carotene 15,15’-monooxygenase 1 (BCMO1) also can cause be a rare cause of hypercarotenemia.3

Carotenoderma, the clinical cutaneous manifestation of hypercarotenemia, occurs as a result of β-carotene deposits in the skin when serum concentration exceeds 250 μg/dL. More specifically, β-carotene accumulates mainly in the lipid-rich stratum corneum as well as in sweat and sebum, which explains the localized discoloration in fatty tissues and areas rich in sweat glands (eg, nasolabial folds, palms, soles).3,4 The sclerae of the eyes are not affected by the surplus of β-carotene in carotenoderma, which helps distinguish it from jaundice.5

The differential diagnosis of yellow discoloration of the skin includes jaundice, encompassing the prehepatic, hepatocellular, and posthepatic categories.4 Also noteworthy in the differential diagnosis is lycopenemia, which occurs as a result of eating lycopene-rich foods (eg, tomatoes), resulting in a deeper orange-yellow pigmentation when compared to the cutaneous manifestation of hypercarotenemia.2,4,6 Several drugs also have been reported to induce yellow discoloration of the skin, including sunitinib,7 sorafenib,8 quinacrine, saffron supplements, santonin, fluorescein, 2,4-dinitrophenol, canthaxanthin, tetryl and picric acids, and acriflavine.2,4

Carotenoderma caused by a diet rich in β-carotene is a benign condition in which a diet low in β-carotene is implicated for treatment. Contrary to popular belief, vitamin A toxicity does not occur in the presence of a surplus of β-carotenes because the enzymatic conversion of β-carotene to vitamin A is strictly regulated.9 Although acknowledging the various causes of carotenoderma is important, a simple history and laboratory testing for elevated serum β-carotene levels can eliminate further unnecessary testing and allow for prompt recognition of the condition. Appropriate dietary modifications also may be warranted.

- Roe DA. Assessment of risk factors for carotenodermia and cutaneous signs of hypervitaminosis A in college-aged populations. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:303-308.

- Manolios N, Samaras K. Hypercarotenaemia. Intern Med J. 2006;36:534.

- Wageesha ND, Ekanayake S, Jansz ER, et al. Studies on hypercarotenemia due to excessive ingestion of carrot, pumpkin and papaw [published online September 27, 2010]. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62:20-25.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

- Maruani A, Labarthe F, Dupré T, et al. Hypercarotenaemia in an infant [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:32-35.

- Shaw JA, Koti M. Clinical images. CMAJ. 2009;180:895.

- Vignand-Courtin C, Martin C, Le Beller C, et al. Cutaneous side effects associated with sunitinib: an analysis of 8 cases. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:286-289.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT, Dutcher J. Yellow skin discoloration associated with sorafenib use for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. South Med J. 2007;100:328-330.

- Lascari AD. Carotenemia. a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20:25-29.

- Roe DA. Assessment of risk factors for carotenodermia and cutaneous signs of hypervitaminosis A in college-aged populations. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:303-308.

- Manolios N, Samaras K. Hypercarotenaemia. Intern Med J. 2006;36:534.

- Wageesha ND, Ekanayake S, Jansz ER, et al. Studies on hypercarotenemia due to excessive ingestion of carrot, pumpkin and papaw [published online September 27, 2010]. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62:20-25.

- Maharshak N, Shapiro J, Trau H. Carotenoderma—a review of the current literature. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:178-181.

- Maruani A, Labarthe F, Dupré T, et al. Hypercarotenaemia in an infant [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:32-35.

- Shaw JA, Koti M. Clinical images. CMAJ. 2009;180:895.

- Vignand-Courtin C, Martin C, Le Beller C, et al. Cutaneous side effects associated with sunitinib: an analysis of 8 cases. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:286-289.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT, Dutcher J. Yellow skin discoloration associated with sorafenib use for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. South Med J. 2007;100:328-330.

- Lascari AD. Carotenemia. a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20:25-29.

Practice Points

- Carotenoderma is a cutaneous manifestation of elevated serum β-carotene levels and classically localizes to fatty tissues and areas rich in sweat glands.

- Carotenoderma caused by a diet rich in β-carotene is a benign condition in which a diet low in β-carotene is implicated for treatment.

Progressive Widespread Telangiectasias

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

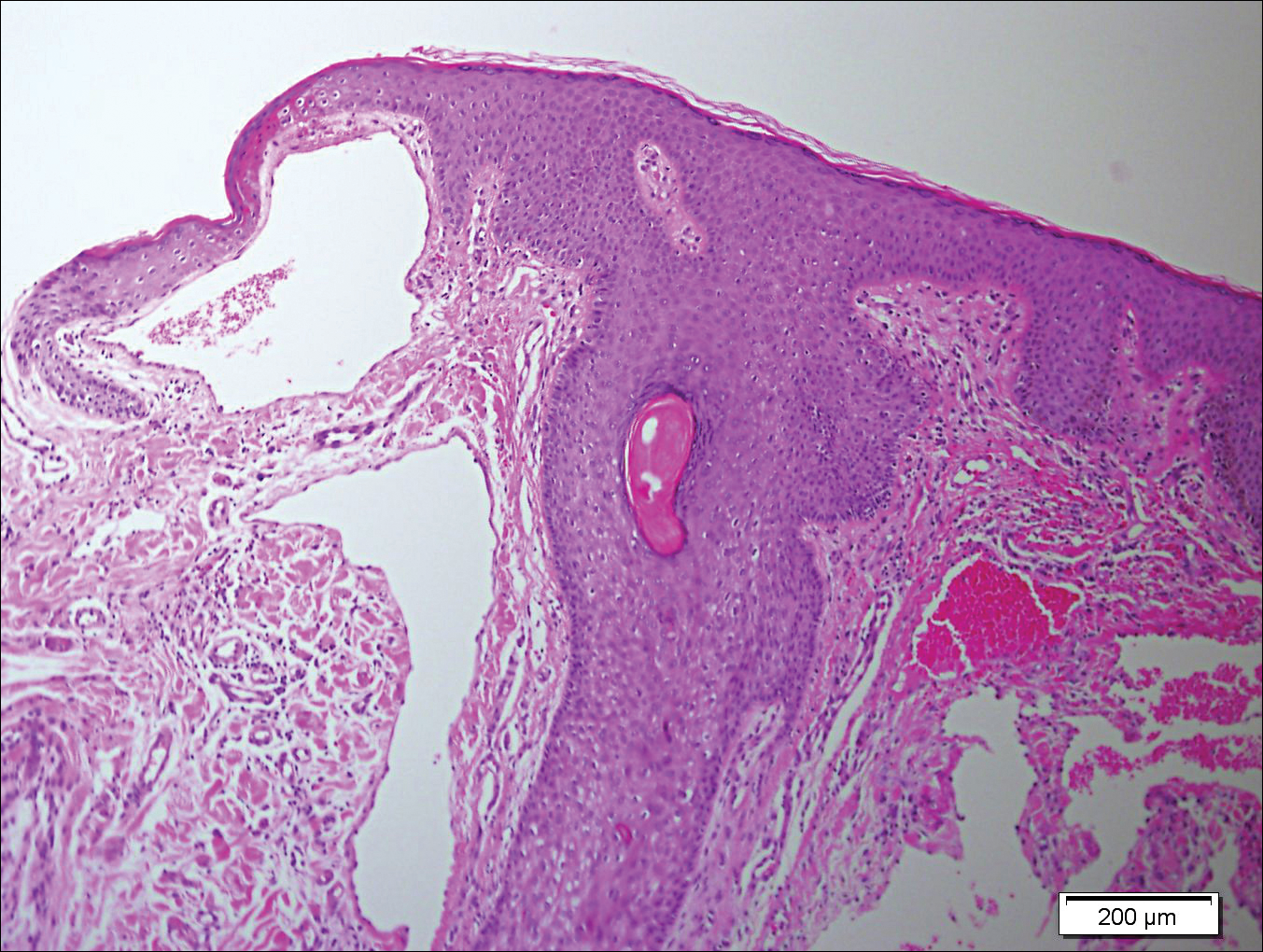

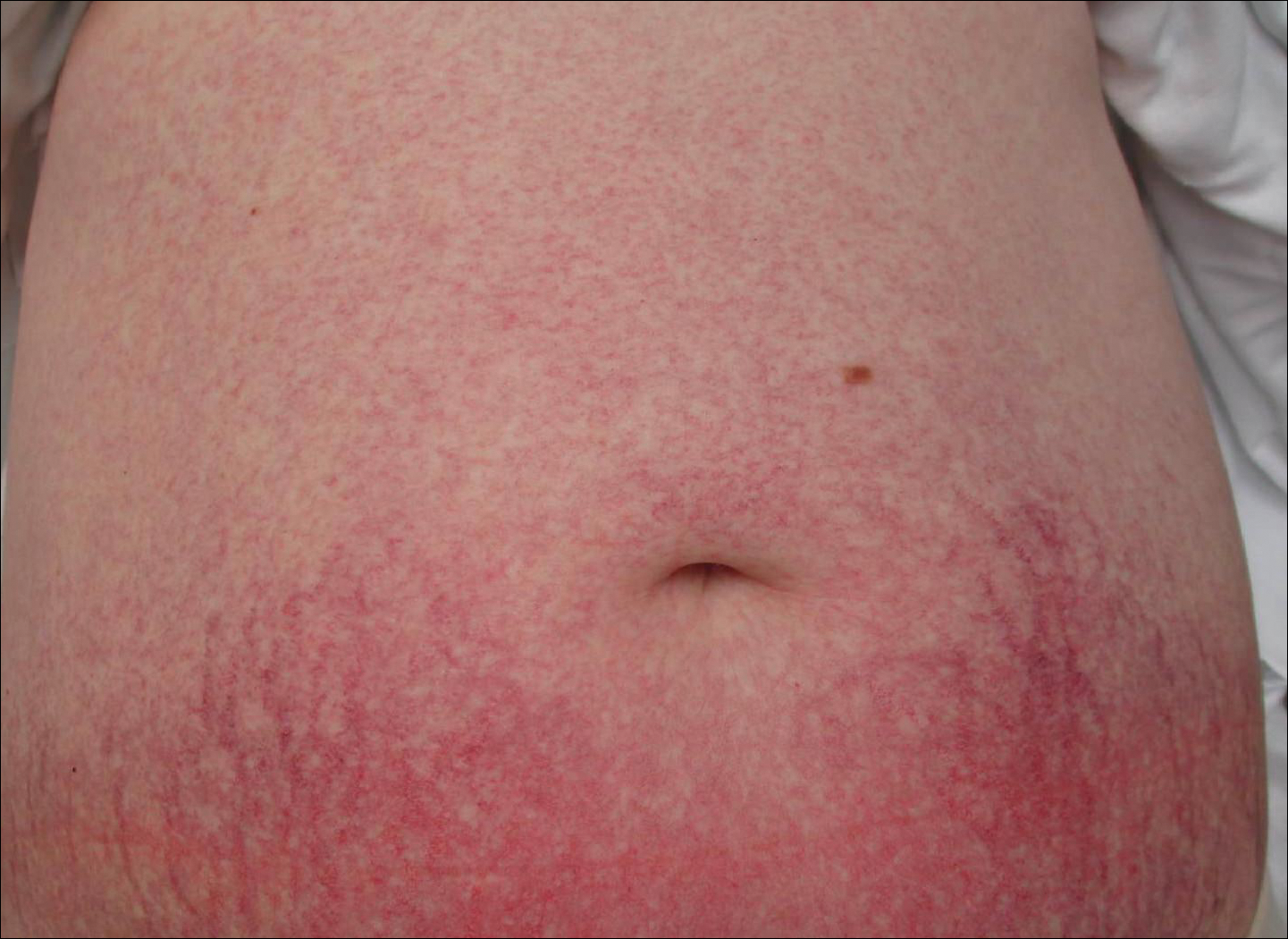

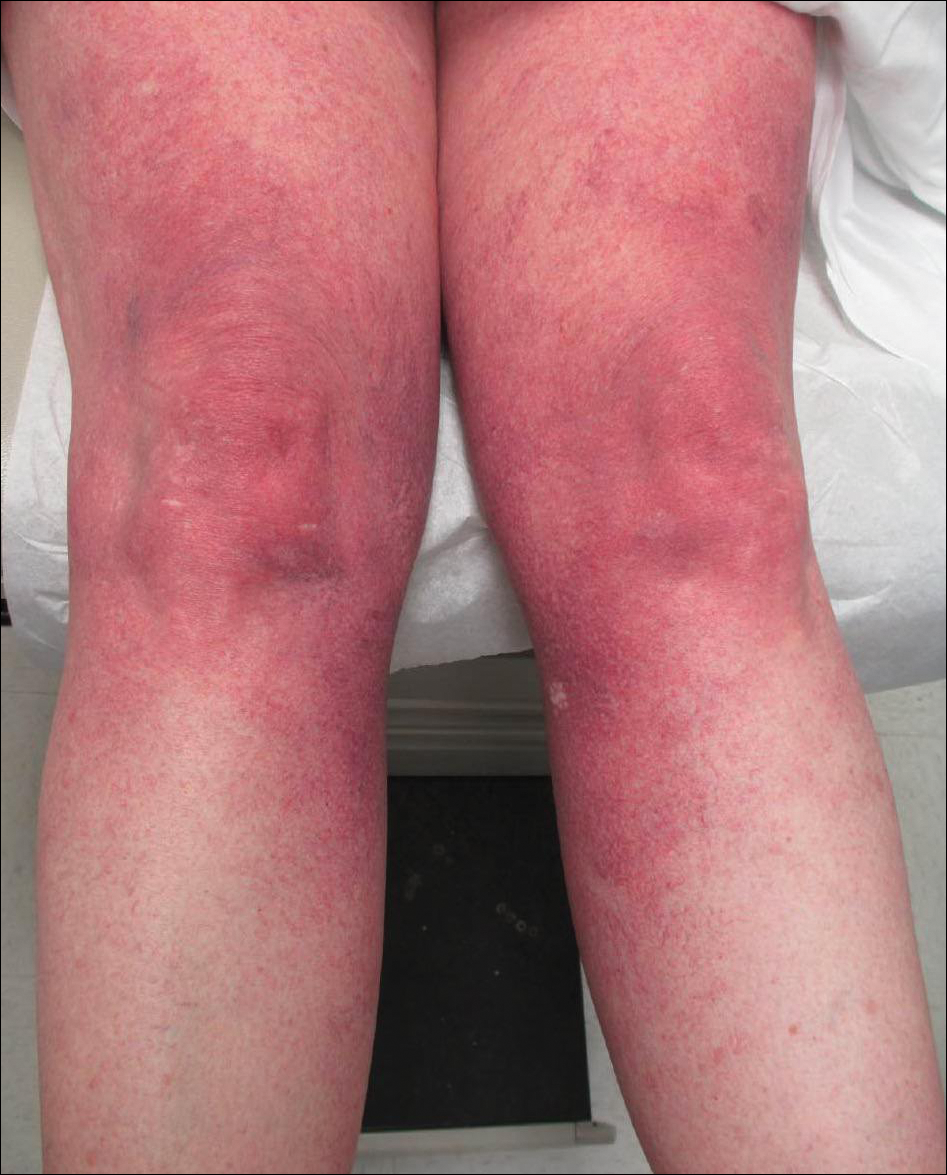

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Histopathologic examination revealed ectatic blood vessels lined with unremarkable endothelial cells and thickened, hyalinized vessel walls scattered within the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The epidermis was unremarkable. There was minimal associated inflammation and no extravasation of erythrocytes. The hyalinized material was weakly positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining (Figure 2) and negative on Congo red staining, which supported of a diagnosis of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV).

The patient previously had been given a suspected diagnosis of generalized essential telangiectasia by an outside dermatologist several years prior to the current presentation, as CCV had yet to be recognized as its own entity and therefore few cases had been described in the literature. She had a known history of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which are associated with the condition. Multiple specialists concluded that the disease was too extensive for laser treatment. A review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE yielded no established treatment options.

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is a rare acquired microangiopathy involving the small vessels of the skin. Its clinical presentation is indistinguishable from that of generalized essential telangiectasia (GET). Patients generally present with asymptomatic, widespread, blanching, symmetric telangiectasias that classically begin on the legs and steadily progress upward with classic sparing of the face (Figure 3). Whereas GET has been reported to involve the oral and conjunctival mucosa, mucosal involvement is not typically observed in CCV and is considered to be a distinguishing factor between the 2 conditions.1,2 However, our patient reported oral symptoms, and oral erosions were seen on multiple physical examinations; therefore, ours is a rare case of mucosal involvement in conjunction with CCV. Given this finding, it is possible that more cases of CCV with mucosal involvement may exist but have been clinically misdiagnosed as GET.

First described by Salama and Rosenthal3 in 2000, CCV remains a rarely reported entity, with approximately 33 reported cases in the worldwide literature.2,4-7 The condition typically arises in adults with an equal predilection for males and females.2 The true incidence of CCV is unknown and likely is underreported given its close similarities to GET, which often is diagnosed clinically. The unique histopathologic finding of superficial ectatic vascular spaces with eosinophilic hyalinized vessel walls in CCV is key to distinguishing these similar entities, and even this finding can be subtle and is easily overlooked. Inflammation is sparse to absent. Deposited material is positive on periodic acid-Schiff and cytokeratin IV staining (representing reduplicated basement membrane-type collagen) and is diastase resistant. Smooth muscle actin staining is diminished or absent. Ultrastructural examination reveals reduplicated, laminated basement membrane; Luse bodies (abnormally long, widely spaced collagen fibers); and a decrease in or loss of pericytes. Of note, Luse bodies are nonspecific and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of CCV.1

The etiology of CCV is unclear, and multiple pathogenetic mechanisms have been proposed. Ultimately, this entity is thought to arise from repeated endothelial cell damage, although the trigger for the endothelial cell injury is not completely understood. Diabetes mellitus sometimes is associated with microangiopathy and may be a confounding but not causative factor in some cases.1 Some investigators believe CCV is caused by a genetic defect that alters collagen production in the small vessels of the skin.5 Others have hypothesized that it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying disease or is associated with a medication; however, no disease or drug has been convincingly implicated in CCV.8

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy is limited to the skin, with no known reports of systemic involvement in the literature.7 There are no recommended laboratory studies to aid in diagnosis.1 It is critical to exclude hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as these patients can have life-threatening systemic involvement. Patients with CCV generally have no history of a bleeding diathesis, patients with HHT classically report recurrent epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding.7 A family history of HHT also is helpful for diagnosis, as the condition is autosomal dominant.1 Neither HHT or telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans, which also can be included in the differential diagnosis, demonstrate vessel wall hyalinization.

Treatment options for CCV are limited. Basso et al6 reported notable improvement in a patient with CCV treated with a combined 595-nm pulsed dye laser and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and optimized pulsed light. In one patient, treatment with a 585-nm pulsed dye laser produced a blanching response, suggesting that this may be a potential treatment option.7 Treatment with sclerotherapy has been ineffective.2

It is critical for both dermatologists and dermatopathologists to recognize and report this newly described entity, as the unique finding of vessel wall hyalinization in CCV may be indicative of a certain pathogenetic mechanism and effective treatment avenue that has yet to be established due to the relatively few number of reports that currently exist in the literature.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.

- Burdick LM, Lohser S, Somach SC, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cutaneous microangiopathy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:741-746.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and structural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Toda-Brito H, Resende C, Catorze G, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare cause of generalised cutaneous telangiectasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210635.

- Ma DL, Vano-Galvan S. Images in clinical medicine: cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:E14.

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111.

- Moteqi SI, Yasuda M, Yamanaka M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of first Japanese case and review of the literature. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:145-149.

- González Fernández D, Gómez Bernal S, Vivanco Allende B, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: description of two new cases in elderly women and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2012;225:1-8.