User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Running for Rare Team Participates in Boston Marathon to Raise Funds for Undiagnosed Patients

Braving rain, wind, and frigid conditions, the Running for Rare team of marathon runners participated in the Boston Marathon on April 16, 2018, to raise funds for NORD’s assistance program to help undiagnosed patients. For the past several years, the runners have supported NORD by participating in the Boston Marathon as well as several other full- and half-marathons. Visit the runners’ web page.

Braving rain, wind, and frigid conditions, the Running for Rare team of marathon runners participated in the Boston Marathon on April 16, 2018, to raise funds for NORD’s assistance program to help undiagnosed patients. For the past several years, the runners have supported NORD by participating in the Boston Marathon as well as several other full- and half-marathons. Visit the runners’ web page.

Braving rain, wind, and frigid conditions, the Running for Rare team of marathon runners participated in the Boston Marathon on April 16, 2018, to raise funds for NORD’s assistance program to help undiagnosed patients. For the past several years, the runners have supported NORD by participating in the Boston Marathon as well as several other full- and half-marathons. Visit the runners’ web page.

NORD and Other Patient Organizations Oppose Short-Term, Limited-Duration Health Plans

NORD has joined several other patient organizations in voicing opposition to proposed expansion of short-term, limited-duration health plans. NORD and its advocacy partners believe that expanding these plans would destabilize the insurance marketplace and increase premiums for those who are in the greatest need of care. For information, view the coalition letter to Congress here and letter to the Administration here.

NORD has joined several other patient organizations in voicing opposition to proposed expansion of short-term, limited-duration health plans. NORD and its advocacy partners believe that expanding these plans would destabilize the insurance marketplace and increase premiums for those who are in the greatest need of care. For information, view the coalition letter to Congress here and letter to the Administration here.

NORD has joined several other patient organizations in voicing opposition to proposed expansion of short-term, limited-duration health plans. NORD and its advocacy partners believe that expanding these plans would destabilize the insurance marketplace and increase premiums for those who are in the greatest need of care. For information, view the coalition letter to Congress here and letter to the Administration here.

Medical Nutrition Equity Act Capitol Hill Day Planned for June 1

As part of the Patients and Providers for Medical Nutrition Equity Coalition, NORD will participate in an advocacy day on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on Friday, June 1, 2018, in support of the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (H.R.2587, S.1194). This legislation would require the coverage of medical nutrition in Medicaid, Medicare, the Federal Employee Health Benefit Plan, and certain private insurance. For information on the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, view the coalition letter here.

As part of the Patients and Providers for Medical Nutrition Equity Coalition, NORD will participate in an advocacy day on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on Friday, June 1, 2018, in support of the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (H.R.2587, S.1194). This legislation would require the coverage of medical nutrition in Medicaid, Medicare, the Federal Employee Health Benefit Plan, and certain private insurance. For information on the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, view the coalition letter here.

As part of the Patients and Providers for Medical Nutrition Equity Coalition, NORD will participate in an advocacy day on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on Friday, June 1, 2018, in support of the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (H.R.2587, S.1194). This legislation would require the coverage of medical nutrition in Medicaid, Medicare, the Federal Employee Health Benefit Plan, and certain private insurance. For information on the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, view the coalition letter here.

More Than 100 Patient Organizations Join NORD in Supporting the RARE Act

NORD has sent a letter to Congress, signed by more than 100 patient advocacy organizations, in support of the Rare Disease Advancement, Research, and Education Act of 2018 (H.R.5115) or the “RARE Act of 2018.” Read NORD’s letter to see how this proposed legislation would help patients and families affected by rare diseases, medical researchers, and clinicians seeking to provide optimal care for their patients.

NORD has sent a letter to Congress, signed by more than 100 patient advocacy organizations, in support of the Rare Disease Advancement, Research, and Education Act of 2018 (H.R.5115) or the “RARE Act of 2018.” Read NORD’s letter to see how this proposed legislation would help patients and families affected by rare diseases, medical researchers, and clinicians seeking to provide optimal care for their patients.

NORD has sent a letter to Congress, signed by more than 100 patient advocacy organizations, in support of the Rare Disease Advancement, Research, and Education Act of 2018 (H.R.5115) or the “RARE Act of 2018.” Read NORD’s letter to see how this proposed legislation would help patients and families affected by rare diseases, medical researchers, and clinicians seeking to provide optimal care for their patients.

RFPs Available for the Study of Three Rare Diseases

NORD’s Research Grant Program is still accepting proposals for the study of three rare diseases: cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. All interested US and international researchers are encouraged to apply. Learn more.

NORD’s Research Grant Program is still accepting proposals for the study of three rare diseases: cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. All interested US and international researchers are encouraged to apply. Learn more.

NORD’s Research Grant Program is still accepting proposals for the study of three rare diseases: cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. All interested US and international researchers are encouraged to apply. Learn more.

2018 Marks 35th Anniversary of NORD and the Orphan Drug Act

In January of 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed the Orphan Drug Act, launching a new era of hope for the millions of Americans with diseases so rare that no pharmaceutical company was pursuing development of treatments. A few months later, the patient advocates who had worked together to get that law enacted formally announced their collaboration as the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), to provide advocacy, education, research, and patient services on behalf of all people affected by rare diseases. Throughout 2018, NORD and others in the rare disease community will be celebrating this 35th anniversary year. While only a dozen rare disease treatments had been developed by industry in the decade before 1983, more than 500 have been approved by FDA since then and many more are in the pipeline. Many of these are breakthrough therapies that have been life-saving, or have significantly improved quality of life, for patients who previously had no therapy. View archived video from 30th anniversary about the role of patient advocates in enactment of the Orphan Drug Act.

In January of 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed the Orphan Drug Act, launching a new era of hope for the millions of Americans with diseases so rare that no pharmaceutical company was pursuing development of treatments. A few months later, the patient advocates who had worked together to get that law enacted formally announced their collaboration as the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), to provide advocacy, education, research, and patient services on behalf of all people affected by rare diseases. Throughout 2018, NORD and others in the rare disease community will be celebrating this 35th anniversary year. While only a dozen rare disease treatments had been developed by industry in the decade before 1983, more than 500 have been approved by FDA since then and many more are in the pipeline. Many of these are breakthrough therapies that have been life-saving, or have significantly improved quality of life, for patients who previously had no therapy. View archived video from 30th anniversary about the role of patient advocates in enactment of the Orphan Drug Act.

In January of 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed the Orphan Drug Act, launching a new era of hope for the millions of Americans with diseases so rare that no pharmaceutical company was pursuing development of treatments. A few months later, the patient advocates who had worked together to get that law enacted formally announced their collaboration as the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), to provide advocacy, education, research, and patient services on behalf of all people affected by rare diseases. Throughout 2018, NORD and others in the rare disease community will be celebrating this 35th anniversary year. While only a dozen rare disease treatments had been developed by industry in the decade before 1983, more than 500 have been approved by FDA since then and many more are in the pipeline. Many of these are breakthrough therapies that have been life-saving, or have significantly improved quality of life, for patients who previously had no therapy. View archived video from 30th anniversary about the role of patient advocates in enactment of the Orphan Drug Act.

Register Now for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards Celebration

On Thursday, May 17, 2018, NORD will honor clinicians, researchers, patient advocates, and others who have made outstanding contributions to improving the lives of people with rare diseases. This will take place at the Rare Impact Awards event, which takes place each year at this time in Washington, DC. This year, the venue will be the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium. Individuals being honored include Robert Campbell, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award; Richard Pazdur, MD, of the FDA, who is receiving the Public Health Leadership Award; and Elisabeth Dykens, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, who is being honored for her research related to rare genetic syndromes. Read about all the honorees.

The Rare Impact Awards Celebration is open to the public. Registration is open now on the NORD website.

On Thursday, May 17, 2018, NORD will honor clinicians, researchers, patient advocates, and others who have made outstanding contributions to improving the lives of people with rare diseases. This will take place at the Rare Impact Awards event, which takes place each year at this time in Washington, DC. This year, the venue will be the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium. Individuals being honored include Robert Campbell, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award; Richard Pazdur, MD, of the FDA, who is receiving the Public Health Leadership Award; and Elisabeth Dykens, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, who is being honored for her research related to rare genetic syndromes. Read about all the honorees.

The Rare Impact Awards Celebration is open to the public. Registration is open now on the NORD website.

On Thursday, May 17, 2018, NORD will honor clinicians, researchers, patient advocates, and others who have made outstanding contributions to improving the lives of people with rare diseases. This will take place at the Rare Impact Awards event, which takes place each year at this time in Washington, DC. This year, the venue will be the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium. Individuals being honored include Robert Campbell, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award; Richard Pazdur, MD, of the FDA, who is receiving the Public Health Leadership Award; and Elisabeth Dykens, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, who is being honored for her research related to rare genetic syndromes. Read about all the honorees.

The Rare Impact Awards Celebration is open to the public. Registration is open now on the NORD website.

Metastatic Meningioma of the Scalp

Meningiomas generally present as slow-growing, expanding intracranial lesions and are the most common benign intracranial tumor in adults.1 Rarely, meningioma exhibits malignant potential and presents as an extracranial soft-tissue mass through extension or as a primary extracranial cutaneous neoplasm. The differential diagnosis of scalp neoplasms must be broadened to include uncommon tumors such as meningioma. We present a rare case of a 68-year-old woman with scalp metastasis of meningioma 11 years after initial resection of the primary tumor.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic nodule on the left parietal scalp of 2 years’ duration. She denied any headaches, difficulty with balance, vision changes, or changes in mentation. Her medical history was remarkable for a benign meningioma removed from the right parietal scalp 11 years prior without radiation therapy, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus and arthritis. The patient’s son died from a brain tumor, but the exact tumor type and age at the time of death were unknown. Her current medications included metformin, insulin glargine, aspirin, and a daily multivitamin. She denied any allergies or history of smoking.

Physical examination of the scalp revealed 4 fixed, nontender, flesh-colored nodules: 2 on the left parietal scalp measuring 3.0 cm and 0.8 cm, respectively (Figure 1A); a 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp; and a 1.6-cm sausage-shaped nodule on the right temple (Figure 1B). No positive lymph nodes were appreciated, and no additional lesions were noted. No additional atypical lesions were noted on full cutaneous examination.

A diagnostic 6-mm punch biopsy of the largest nodule was performed. Intraoperatively, there was no apparent cyst wall, but coiled, loose, stringlike, pink-yellow tissue was removed from the base of the wound before closing with sutures.

The primary histologic finding was cells within fibrous tissue containing delicate round-oval nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm with an indistinct border (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical studies for S100 protein were focal and limited to the cytoplasm of a subset of neoplastic cells (Figure 3). Tumor cells stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and were focally positive for progesterone receptor (Figure 4). Tumor cells were negative for CD31 and CD34. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of metastatic meningioma of the scalp was made.

Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography of the head, neck, and chest demonstrated 3 residual subcutaneous nodules on the scalp and an indeterminate subcentimeter nodule in the right lung. The 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp was removed without complication, and no radiation therapy was administered. The rest of the lesions were monitored. She remained under the close observation of a neurosurgeon and underwent repeat imaging of the scalp nodules and lungs, initially at 3 months and then routinely at the patient’s comfort. The patient currently denies any neurologic symptoms.

Comment

Meningiomas are derived from meningothelial cells found in the leptomeninges and in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain.2 They are common intracranial neoplasms that generally are associated with a benign course and present during the fourth to sixth decades of life. Meningiomas constitute 13% to 30% of intracranial neoplasms and usually are female predominant (3:1).3,4 Rarely, malignant transformation can lead to local and distant metastasis to the lungs,5,6 liver,7 and skeletal system.8 In cases of metastatic spread, there is an increased incidence in males versus females.9-11

Risk Factors

Although many meningiomas are sporadic, numerous risk factors have been associated with the disease development. One study showed a link between exposure to ionizing radiation and subsequent development of meningioma.12 Another study found a population link between a higher incidence of meningioma and nuclear exposure in Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bomb blast in 1980.13 There is an increased incidence of meningioma in patients exposed to radiography from frequent dental imaging, particularly when older machines with higher levels of radiation exposure are used.14Another study demonstrated a correlation between meningioma and hormonal factors (eg, estrogen for hormone therapy) and exacerbation of symptoms during pregnancy.15 There also is an increased incidence of meningioma in breast cancer patients.4 Genetic alterations also have been implicated in the development of meningioma. It was found that 50% of patients with a mutation in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene (which codes for the merlin protein) had associated meningiomas.16,17 Scalp nodules in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 increases suspicion of a scalp meningioma and necessitates biopsy.

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous meningiomas typically present as firm, subcutaneous nodules. Scalp nodules ranging from alopecia18,19 to hypertrichosis20 have been reported. These neoplasms can be painless or painful, depending on mass effect and location.

Classification

The primary clinical classification system of metastatic meningioma was first described in 1974.21 Type 1 meningioma refers to congenital lesions that tend to cluster closer to the midline. Type 2 refers to ectopic soft-tissue lesions that extend to the skin from likely remnants of arachnoid cells. These lesions are more likely to be found around the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. Type 3 meningiomas extend from intracranial tumors that secondarily involve the skin through proliferation through bone or anatomic defects. Type 3 is the result of direct extension and the location of the cutaneous presentation depends on the location of the intracranial lesion.4,22,23

Pathology

Meningiomas exhibit a range of morphologic appearances on histopathology. In almost all meningiomas, tumor cells are concentrically wrapped in tight whorls with round-oval nuclei and delicate chromatin, central clearing, and pale pseudonuclear inclusions. Lamellate calcifications known as psammoma bodies are a common finding. Immunohistochemical studies show that most meningiomas are positive for EMA, vimentin, and progesterone receptor. S100 protein expression, if present, usually is focal.

Differential Diagnosis

Asymptomatic nodules on the scalp may present a diagnostic challenge to physicians. Most common scalp lesions tend to be cystic or lipomatous. In children, a broad differential diagnosis should be considered, including dermoid and epidermoid tumors, dermal sinus tumors, hemangiomas, metastasis of another tumor, aplasia cutis congenita, pilomatricoma, and lipoma. In adults, the differential should focus on epidermoid cysts, lipomas, metastasis of other tumors, osteomas, arteriovenous fistulae, and heterotopic brain tissue. Often, microscopic examination is necessary, along with additional immunohistochemical staining (eg, EMA, vimentin).

Treatment

Treatment options for meningioma include observation, surgical resection, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, as well as a combination of these modalities. The choice of therapy depends on such variables as patient age; performance status; comorbidities; presence or absence of symptoms (including focal neurologic deficits); and tumor location, size, and grade. It is important to note that there is limited knowledge looking at the results of various treatment modalities, and no consensus approach has been established.

Conclusion

Our patient’s medical history was remarkable for an intracranial meningioma 11 years prior to the current presentation, and she was found to have biopsy-proven metastatic meningioma without recurrence of the initial tumor. Patients presenting with a scalp nodule warrant a thorough medical history and consideration beyond common cysts and lipomas.

- Mackay B, Bruner JM, Luna MA. Malignant meningioma of the scalp. Ultrastruc Pathol. 1994;18:235-240.

- Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, et al. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535-1543.

- Bauman G, Fisher B, Schild S, et al. Meningioma, ependymoma, and other adult brain tumors. In: Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds. Clinical Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2007:539-566.

- Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1088-1095.

- Tworek JA, Mikhail AA, Blaivas M. Meningioma: local recurrence and pulmonary metastasis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:946-947.

- Shin MS, Holman WL, Herrera GA, et al. Extensive pulmonary metastasis of an intracranial meningioma with repeated recurrence: radiographic and pathologic features. South Med J. 1996;89:313-318.

- Ferguson JM, Flinn J. Intracranial meningioma with hepatic metastases and hypoglycaemia treated by selective hepatic arterial chemo-embolization. Australas Radiol.1995;39:97-99.

- Palmer JD, Cook PL, Ellison DW. Extracranial osseous metastases from intracranial meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:215-218.

- Glasauer FE, Yuan RH. Intracranial tumours with extracranial metastases. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:474-493.

- Shuangshoti S, Hongsaprabhas C, Netsky MG. Metastasizing meningioma. Cancer. 1970;26:832-841.

- Ohta M, Iwaki T, Kitamoto T, et al. MIB-1 staining index and scoring of histological features in meningioma. Cancer. 1994;74:3176-3189.

- Wrensch M, Minn Y, Chew T, et al. Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: current concepts and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4:278-299.

- Shintani T, Hayakawa N, Hoshi M, et al. High incidence of meningioma among Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors. J Rad Res. 1999;40:49-57.

- Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, et al. Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma. Cancer. 2012;118:4530-4537.

- Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279-282.

- Fontaine B, Rouleau GA, Seizinger BR, et al. Molecular genetics of neurofibromatosis 2 and related tumors (acoustic neuromas and meningioma). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:338-343.

- Rabin BM, Meyer JR, Berlin JW, et al. Radiation-induced changes of the central nervous system and head and neck. Radiographics. 1996;16:1055-1072.

- Tanaka S, Okazaki M, Egusa G, et al. A case of pheochromocytoma associated with meningioma. J Intern Med. 1991;229:371-373.

- Zeikus P, Robinson-Bostom L, Stopa E. Primary cutaneous meningioma in association with a sinus pericranii. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Junaid TA, Nkposong EO, Kolawole TM. Cutaneous meningiomas and an ovarian fibroma in a three-year-old girl. J Pathol. 1972;108:165-167.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningioma—a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Shuangshoti S, Boonjunwetwat D, Kaoroptham S. Association of primary intraspinal meningiomas and subcutaneous meningioma of the cervical region: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:129-134.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol. 2012;136:208-211.

Meningiomas generally present as slow-growing, expanding intracranial lesions and are the most common benign intracranial tumor in adults.1 Rarely, meningioma exhibits malignant potential and presents as an extracranial soft-tissue mass through extension or as a primary extracranial cutaneous neoplasm. The differential diagnosis of scalp neoplasms must be broadened to include uncommon tumors such as meningioma. We present a rare case of a 68-year-old woman with scalp metastasis of meningioma 11 years after initial resection of the primary tumor.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic nodule on the left parietal scalp of 2 years’ duration. She denied any headaches, difficulty with balance, vision changes, or changes in mentation. Her medical history was remarkable for a benign meningioma removed from the right parietal scalp 11 years prior without radiation therapy, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus and arthritis. The patient’s son died from a brain tumor, but the exact tumor type and age at the time of death were unknown. Her current medications included metformin, insulin glargine, aspirin, and a daily multivitamin. She denied any allergies or history of smoking.

Physical examination of the scalp revealed 4 fixed, nontender, flesh-colored nodules: 2 on the left parietal scalp measuring 3.0 cm and 0.8 cm, respectively (Figure 1A); a 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp; and a 1.6-cm sausage-shaped nodule on the right temple (Figure 1B). No positive lymph nodes were appreciated, and no additional lesions were noted. No additional atypical lesions were noted on full cutaneous examination.

A diagnostic 6-mm punch biopsy of the largest nodule was performed. Intraoperatively, there was no apparent cyst wall, but coiled, loose, stringlike, pink-yellow tissue was removed from the base of the wound before closing with sutures.

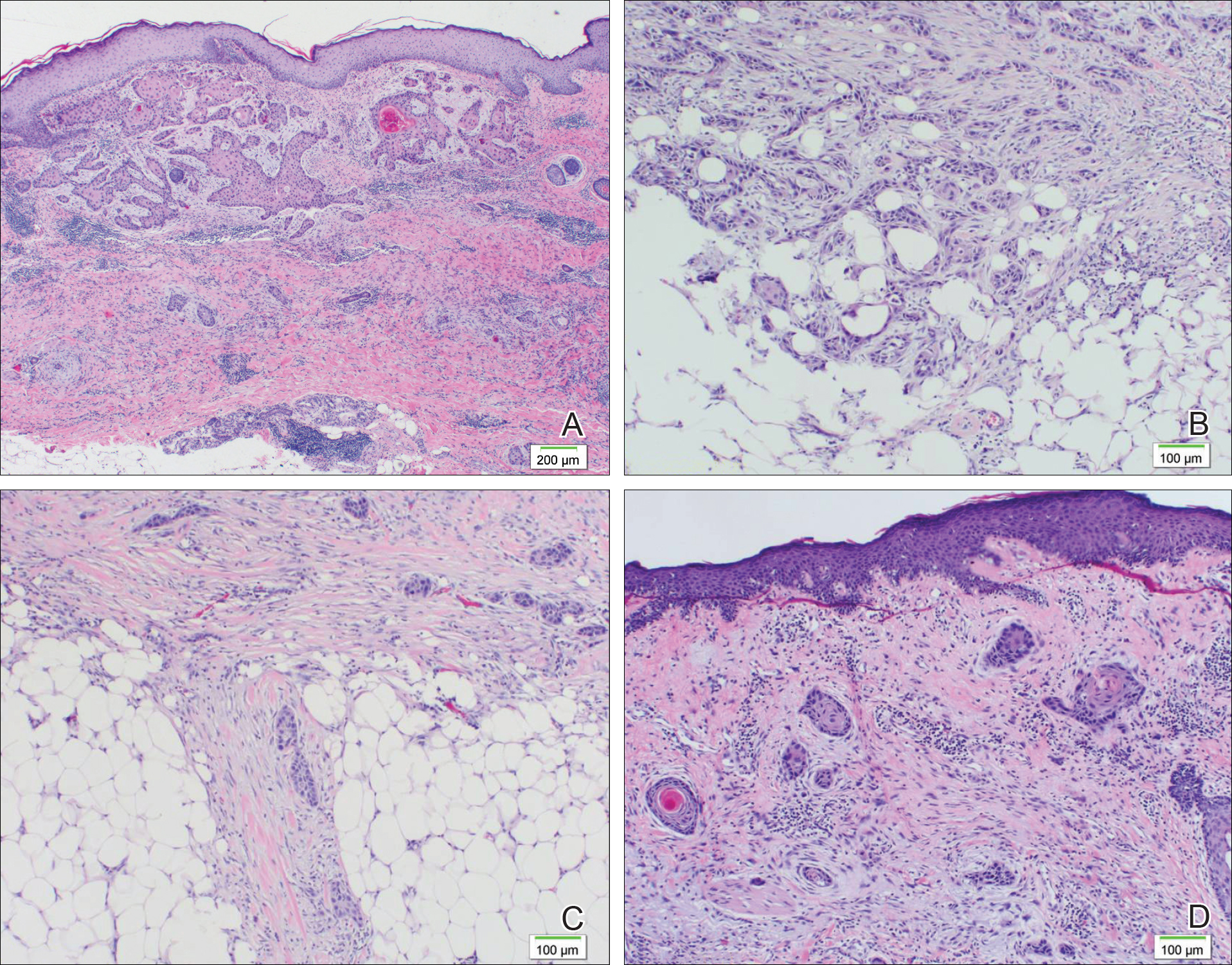

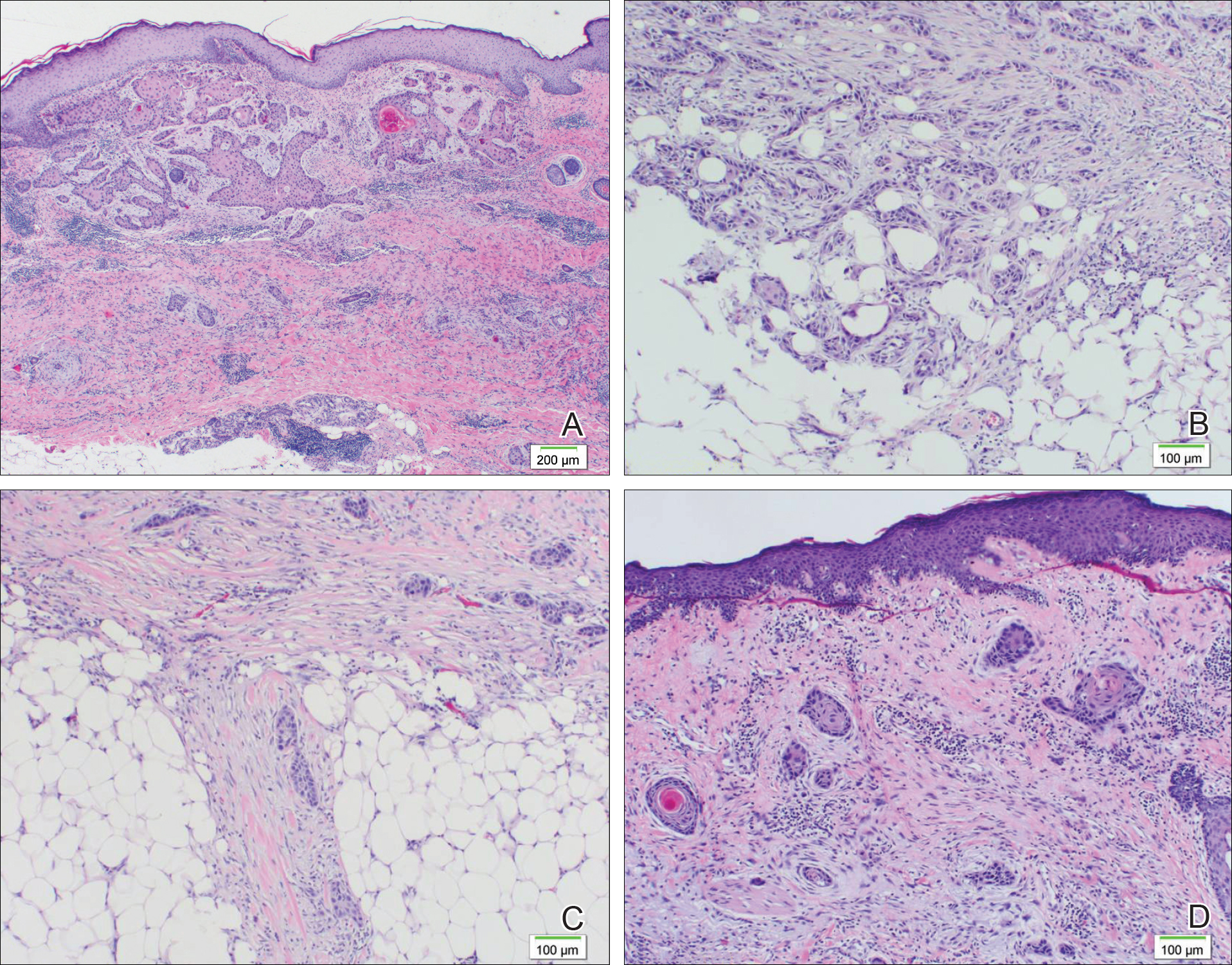

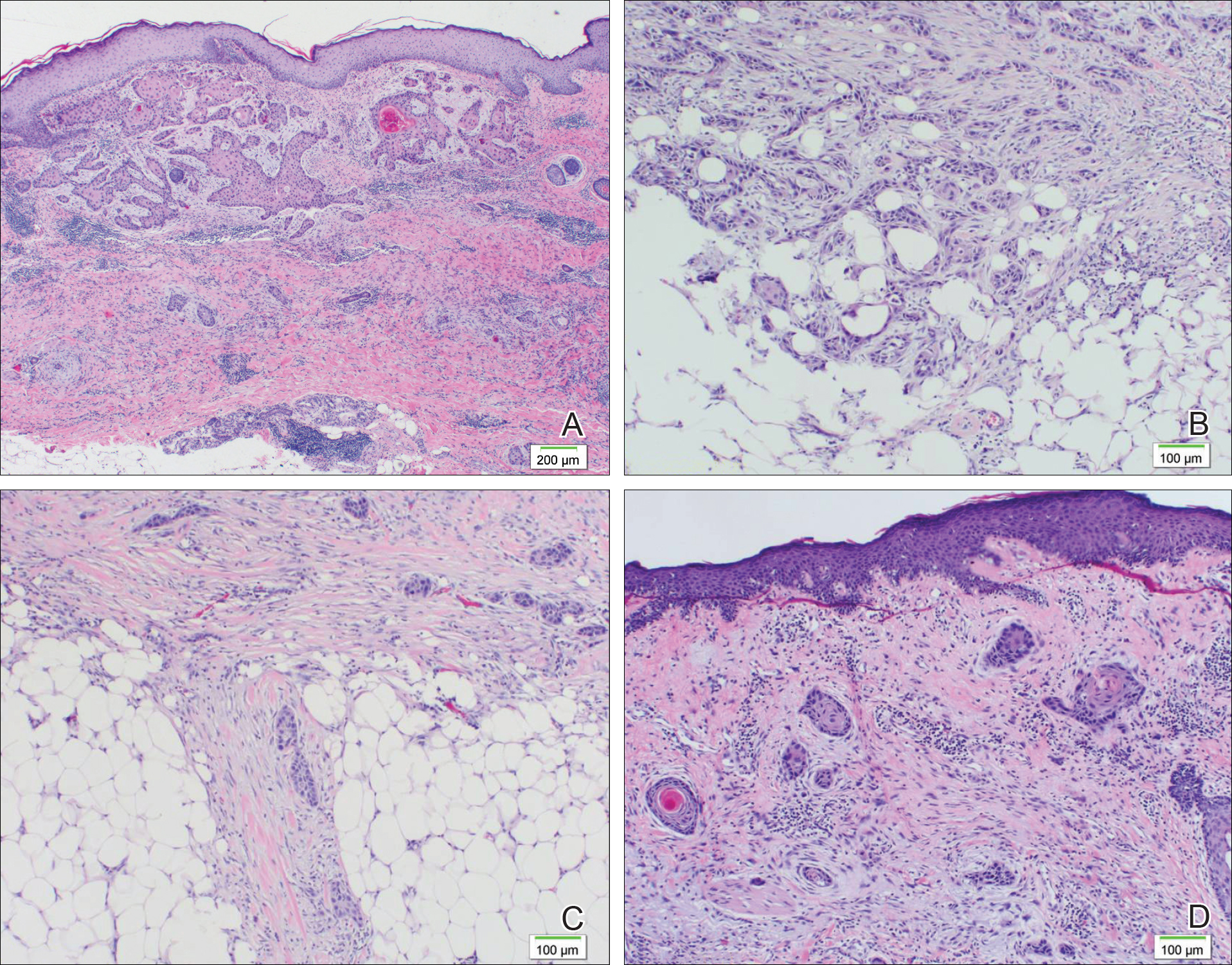

The primary histologic finding was cells within fibrous tissue containing delicate round-oval nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm with an indistinct border (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical studies for S100 protein were focal and limited to the cytoplasm of a subset of neoplastic cells (Figure 3). Tumor cells stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and were focally positive for progesterone receptor (Figure 4). Tumor cells were negative for CD31 and CD34. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of metastatic meningioma of the scalp was made.

Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography of the head, neck, and chest demonstrated 3 residual subcutaneous nodules on the scalp and an indeterminate subcentimeter nodule in the right lung. The 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp was removed without complication, and no radiation therapy was administered. The rest of the lesions were monitored. She remained under the close observation of a neurosurgeon and underwent repeat imaging of the scalp nodules and lungs, initially at 3 months and then routinely at the patient’s comfort. The patient currently denies any neurologic symptoms.

Comment

Meningiomas are derived from meningothelial cells found in the leptomeninges and in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain.2 They are common intracranial neoplasms that generally are associated with a benign course and present during the fourth to sixth decades of life. Meningiomas constitute 13% to 30% of intracranial neoplasms and usually are female predominant (3:1).3,4 Rarely, malignant transformation can lead to local and distant metastasis to the lungs,5,6 liver,7 and skeletal system.8 In cases of metastatic spread, there is an increased incidence in males versus females.9-11

Risk Factors

Although many meningiomas are sporadic, numerous risk factors have been associated with the disease development. One study showed a link between exposure to ionizing radiation and subsequent development of meningioma.12 Another study found a population link between a higher incidence of meningioma and nuclear exposure in Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bomb blast in 1980.13 There is an increased incidence of meningioma in patients exposed to radiography from frequent dental imaging, particularly when older machines with higher levels of radiation exposure are used.14Another study demonstrated a correlation between meningioma and hormonal factors (eg, estrogen for hormone therapy) and exacerbation of symptoms during pregnancy.15 There also is an increased incidence of meningioma in breast cancer patients.4 Genetic alterations also have been implicated in the development of meningioma. It was found that 50% of patients with a mutation in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene (which codes for the merlin protein) had associated meningiomas.16,17 Scalp nodules in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 increases suspicion of a scalp meningioma and necessitates biopsy.

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous meningiomas typically present as firm, subcutaneous nodules. Scalp nodules ranging from alopecia18,19 to hypertrichosis20 have been reported. These neoplasms can be painless or painful, depending on mass effect and location.

Classification

The primary clinical classification system of metastatic meningioma was first described in 1974.21 Type 1 meningioma refers to congenital lesions that tend to cluster closer to the midline. Type 2 refers to ectopic soft-tissue lesions that extend to the skin from likely remnants of arachnoid cells. These lesions are more likely to be found around the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. Type 3 meningiomas extend from intracranial tumors that secondarily involve the skin through proliferation through bone or anatomic defects. Type 3 is the result of direct extension and the location of the cutaneous presentation depends on the location of the intracranial lesion.4,22,23

Pathology

Meningiomas exhibit a range of morphologic appearances on histopathology. In almost all meningiomas, tumor cells are concentrically wrapped in tight whorls with round-oval nuclei and delicate chromatin, central clearing, and pale pseudonuclear inclusions. Lamellate calcifications known as psammoma bodies are a common finding. Immunohistochemical studies show that most meningiomas are positive for EMA, vimentin, and progesterone receptor. S100 protein expression, if present, usually is focal.

Differential Diagnosis

Asymptomatic nodules on the scalp may present a diagnostic challenge to physicians. Most common scalp lesions tend to be cystic or lipomatous. In children, a broad differential diagnosis should be considered, including dermoid and epidermoid tumors, dermal sinus tumors, hemangiomas, metastasis of another tumor, aplasia cutis congenita, pilomatricoma, and lipoma. In adults, the differential should focus on epidermoid cysts, lipomas, metastasis of other tumors, osteomas, arteriovenous fistulae, and heterotopic brain tissue. Often, microscopic examination is necessary, along with additional immunohistochemical staining (eg, EMA, vimentin).

Treatment

Treatment options for meningioma include observation, surgical resection, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, as well as a combination of these modalities. The choice of therapy depends on such variables as patient age; performance status; comorbidities; presence or absence of symptoms (including focal neurologic deficits); and tumor location, size, and grade. It is important to note that there is limited knowledge looking at the results of various treatment modalities, and no consensus approach has been established.

Conclusion

Our patient’s medical history was remarkable for an intracranial meningioma 11 years prior to the current presentation, and she was found to have biopsy-proven metastatic meningioma without recurrence of the initial tumor. Patients presenting with a scalp nodule warrant a thorough medical history and consideration beyond common cysts and lipomas.

Meningiomas generally present as slow-growing, expanding intracranial lesions and are the most common benign intracranial tumor in adults.1 Rarely, meningioma exhibits malignant potential and presents as an extracranial soft-tissue mass through extension or as a primary extracranial cutaneous neoplasm. The differential diagnosis of scalp neoplasms must be broadened to include uncommon tumors such as meningioma. We present a rare case of a 68-year-old woman with scalp metastasis of meningioma 11 years after initial resection of the primary tumor.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic nodule on the left parietal scalp of 2 years’ duration. She denied any headaches, difficulty with balance, vision changes, or changes in mentation. Her medical history was remarkable for a benign meningioma removed from the right parietal scalp 11 years prior without radiation therapy, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus and arthritis. The patient’s son died from a brain tumor, but the exact tumor type and age at the time of death were unknown. Her current medications included metformin, insulin glargine, aspirin, and a daily multivitamin. She denied any allergies or history of smoking.

Physical examination of the scalp revealed 4 fixed, nontender, flesh-colored nodules: 2 on the left parietal scalp measuring 3.0 cm and 0.8 cm, respectively (Figure 1A); a 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp; and a 1.6-cm sausage-shaped nodule on the right temple (Figure 1B). No positive lymph nodes were appreciated, and no additional lesions were noted. No additional atypical lesions were noted on full cutaneous examination.

A diagnostic 6-mm punch biopsy of the largest nodule was performed. Intraoperatively, there was no apparent cyst wall, but coiled, loose, stringlike, pink-yellow tissue was removed from the base of the wound before closing with sutures.

The primary histologic finding was cells within fibrous tissue containing delicate round-oval nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm with an indistinct border (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical studies for S100 protein were focal and limited to the cytoplasm of a subset of neoplastic cells (Figure 3). Tumor cells stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and were focally positive for progesterone receptor (Figure 4). Tumor cells were negative for CD31 and CD34. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of metastatic meningioma of the scalp was made.

Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography of the head, neck, and chest demonstrated 3 residual subcutaneous nodules on the scalp and an indeterminate subcentimeter nodule in the right lung. The 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp was removed without complication, and no radiation therapy was administered. The rest of the lesions were monitored. She remained under the close observation of a neurosurgeon and underwent repeat imaging of the scalp nodules and lungs, initially at 3 months and then routinely at the patient’s comfort. The patient currently denies any neurologic symptoms.

Comment

Meningiomas are derived from meningothelial cells found in the leptomeninges and in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain.2 They are common intracranial neoplasms that generally are associated with a benign course and present during the fourth to sixth decades of life. Meningiomas constitute 13% to 30% of intracranial neoplasms and usually are female predominant (3:1).3,4 Rarely, malignant transformation can lead to local and distant metastasis to the lungs,5,6 liver,7 and skeletal system.8 In cases of metastatic spread, there is an increased incidence in males versus females.9-11

Risk Factors

Although many meningiomas are sporadic, numerous risk factors have been associated with the disease development. One study showed a link between exposure to ionizing radiation and subsequent development of meningioma.12 Another study found a population link between a higher incidence of meningioma and nuclear exposure in Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bomb blast in 1980.13 There is an increased incidence of meningioma in patients exposed to radiography from frequent dental imaging, particularly when older machines with higher levels of radiation exposure are used.14Another study demonstrated a correlation between meningioma and hormonal factors (eg, estrogen for hormone therapy) and exacerbation of symptoms during pregnancy.15 There also is an increased incidence of meningioma in breast cancer patients.4 Genetic alterations also have been implicated in the development of meningioma. It was found that 50% of patients with a mutation in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene (which codes for the merlin protein) had associated meningiomas.16,17 Scalp nodules in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 increases suspicion of a scalp meningioma and necessitates biopsy.

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous meningiomas typically present as firm, subcutaneous nodules. Scalp nodules ranging from alopecia18,19 to hypertrichosis20 have been reported. These neoplasms can be painless or painful, depending on mass effect and location.

Classification

The primary clinical classification system of metastatic meningioma was first described in 1974.21 Type 1 meningioma refers to congenital lesions that tend to cluster closer to the midline. Type 2 refers to ectopic soft-tissue lesions that extend to the skin from likely remnants of arachnoid cells. These lesions are more likely to be found around the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. Type 3 meningiomas extend from intracranial tumors that secondarily involve the skin through proliferation through bone or anatomic defects. Type 3 is the result of direct extension and the location of the cutaneous presentation depends on the location of the intracranial lesion.4,22,23

Pathology

Meningiomas exhibit a range of morphologic appearances on histopathology. In almost all meningiomas, tumor cells are concentrically wrapped in tight whorls with round-oval nuclei and delicate chromatin, central clearing, and pale pseudonuclear inclusions. Lamellate calcifications known as psammoma bodies are a common finding. Immunohistochemical studies show that most meningiomas are positive for EMA, vimentin, and progesterone receptor. S100 protein expression, if present, usually is focal.

Differential Diagnosis

Asymptomatic nodules on the scalp may present a diagnostic challenge to physicians. Most common scalp lesions tend to be cystic or lipomatous. In children, a broad differential diagnosis should be considered, including dermoid and epidermoid tumors, dermal sinus tumors, hemangiomas, metastasis of another tumor, aplasia cutis congenita, pilomatricoma, and lipoma. In adults, the differential should focus on epidermoid cysts, lipomas, metastasis of other tumors, osteomas, arteriovenous fistulae, and heterotopic brain tissue. Often, microscopic examination is necessary, along with additional immunohistochemical staining (eg, EMA, vimentin).

Treatment

Treatment options for meningioma include observation, surgical resection, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, as well as a combination of these modalities. The choice of therapy depends on such variables as patient age; performance status; comorbidities; presence or absence of symptoms (including focal neurologic deficits); and tumor location, size, and grade. It is important to note that there is limited knowledge looking at the results of various treatment modalities, and no consensus approach has been established.

Conclusion

Our patient’s medical history was remarkable for an intracranial meningioma 11 years prior to the current presentation, and she was found to have biopsy-proven metastatic meningioma without recurrence of the initial tumor. Patients presenting with a scalp nodule warrant a thorough medical history and consideration beyond common cysts and lipomas.

- Mackay B, Bruner JM, Luna MA. Malignant meningioma of the scalp. Ultrastruc Pathol. 1994;18:235-240.

- Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, et al. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535-1543.

- Bauman G, Fisher B, Schild S, et al. Meningioma, ependymoma, and other adult brain tumors. In: Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds. Clinical Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2007:539-566.

- Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1088-1095.

- Tworek JA, Mikhail AA, Blaivas M. Meningioma: local recurrence and pulmonary metastasis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:946-947.

- Shin MS, Holman WL, Herrera GA, et al. Extensive pulmonary metastasis of an intracranial meningioma with repeated recurrence: radiographic and pathologic features. South Med J. 1996;89:313-318.

- Ferguson JM, Flinn J. Intracranial meningioma with hepatic metastases and hypoglycaemia treated by selective hepatic arterial chemo-embolization. Australas Radiol.1995;39:97-99.

- Palmer JD, Cook PL, Ellison DW. Extracranial osseous metastases from intracranial meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:215-218.

- Glasauer FE, Yuan RH. Intracranial tumours with extracranial metastases. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:474-493.

- Shuangshoti S, Hongsaprabhas C, Netsky MG. Metastasizing meningioma. Cancer. 1970;26:832-841.

- Ohta M, Iwaki T, Kitamoto T, et al. MIB-1 staining index and scoring of histological features in meningioma. Cancer. 1994;74:3176-3189.

- Wrensch M, Minn Y, Chew T, et al. Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: current concepts and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4:278-299.

- Shintani T, Hayakawa N, Hoshi M, et al. High incidence of meningioma among Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors. J Rad Res. 1999;40:49-57.

- Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, et al. Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma. Cancer. 2012;118:4530-4537.

- Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279-282.

- Fontaine B, Rouleau GA, Seizinger BR, et al. Molecular genetics of neurofibromatosis 2 and related tumors (acoustic neuromas and meningioma). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:338-343.

- Rabin BM, Meyer JR, Berlin JW, et al. Radiation-induced changes of the central nervous system and head and neck. Radiographics. 1996;16:1055-1072.

- Tanaka S, Okazaki M, Egusa G, et al. A case of pheochromocytoma associated with meningioma. J Intern Med. 1991;229:371-373.

- Zeikus P, Robinson-Bostom L, Stopa E. Primary cutaneous meningioma in association with a sinus pericranii. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Junaid TA, Nkposong EO, Kolawole TM. Cutaneous meningiomas and an ovarian fibroma in a three-year-old girl. J Pathol. 1972;108:165-167.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningioma—a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Shuangshoti S, Boonjunwetwat D, Kaoroptham S. Association of primary intraspinal meningiomas and subcutaneous meningioma of the cervical region: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:129-134.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol. 2012;136:208-211.

- Mackay B, Bruner JM, Luna MA. Malignant meningioma of the scalp. Ultrastruc Pathol. 1994;18:235-240.

- Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, et al. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535-1543.

- Bauman G, Fisher B, Schild S, et al. Meningioma, ependymoma, and other adult brain tumors. In: Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds. Clinical Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2007:539-566.

- Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1088-1095.

- Tworek JA, Mikhail AA, Blaivas M. Meningioma: local recurrence and pulmonary metastasis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:946-947.

- Shin MS, Holman WL, Herrera GA, et al. Extensive pulmonary metastasis of an intracranial meningioma with repeated recurrence: radiographic and pathologic features. South Med J. 1996;89:313-318.

- Ferguson JM, Flinn J. Intracranial meningioma with hepatic metastases and hypoglycaemia treated by selective hepatic arterial chemo-embolization. Australas Radiol.1995;39:97-99.

- Palmer JD, Cook PL, Ellison DW. Extracranial osseous metastases from intracranial meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:215-218.

- Glasauer FE, Yuan RH. Intracranial tumours with extracranial metastases. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:474-493.

- Shuangshoti S, Hongsaprabhas C, Netsky MG. Metastasizing meningioma. Cancer. 1970;26:832-841.

- Ohta M, Iwaki T, Kitamoto T, et al. MIB-1 staining index and scoring of histological features in meningioma. Cancer. 1994;74:3176-3189.

- Wrensch M, Minn Y, Chew T, et al. Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: current concepts and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4:278-299.

- Shintani T, Hayakawa N, Hoshi M, et al. High incidence of meningioma among Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors. J Rad Res. 1999;40:49-57.

- Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, et al. Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma. Cancer. 2012;118:4530-4537.

- Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279-282.

- Fontaine B, Rouleau GA, Seizinger BR, et al. Molecular genetics of neurofibromatosis 2 and related tumors (acoustic neuromas and meningioma). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:338-343.

- Rabin BM, Meyer JR, Berlin JW, et al. Radiation-induced changes of the central nervous system and head and neck. Radiographics. 1996;16:1055-1072.

- Tanaka S, Okazaki M, Egusa G, et al. A case of pheochromocytoma associated with meningioma. J Intern Med. 1991;229:371-373.

- Zeikus P, Robinson-Bostom L, Stopa E. Primary cutaneous meningioma in association with a sinus pericranii. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Junaid TA, Nkposong EO, Kolawole TM. Cutaneous meningiomas and an ovarian fibroma in a three-year-old girl. J Pathol. 1972;108:165-167.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningioma—a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Shuangshoti S, Boonjunwetwat D, Kaoroptham S. Association of primary intraspinal meningiomas and subcutaneous meningioma of the cervical region: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:129-134.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol. 2012;136:208-211.

Squamoid Eccrine Ductal Carcinoma

Eccrine carcinomas are uncommon cutaneous neoplasms demonstrating nonuniform histologic features, behavior, and nomenclature. Given the rarity of these tumors, no known criteria by which to diagnose the tumor or guidelines for treatment have been proposed. We report a rare case of an immunocompromised patient with a primary squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) who was subsequently treated with radical resection and axillary dissection. It was later determined that the patient had distant metastasis of SEDC. A review of the literature on the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of SEDC also is provided.

Case Report

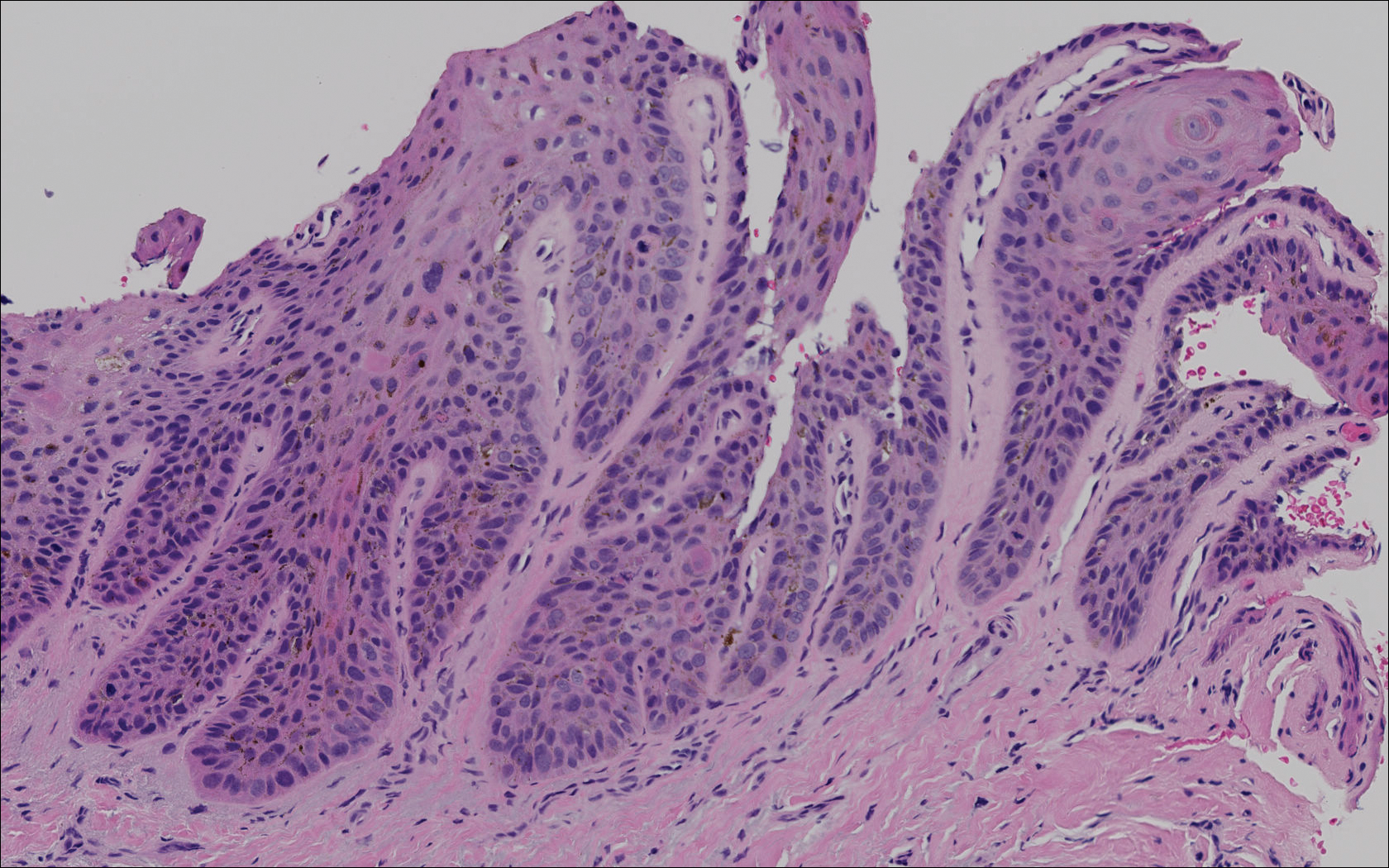

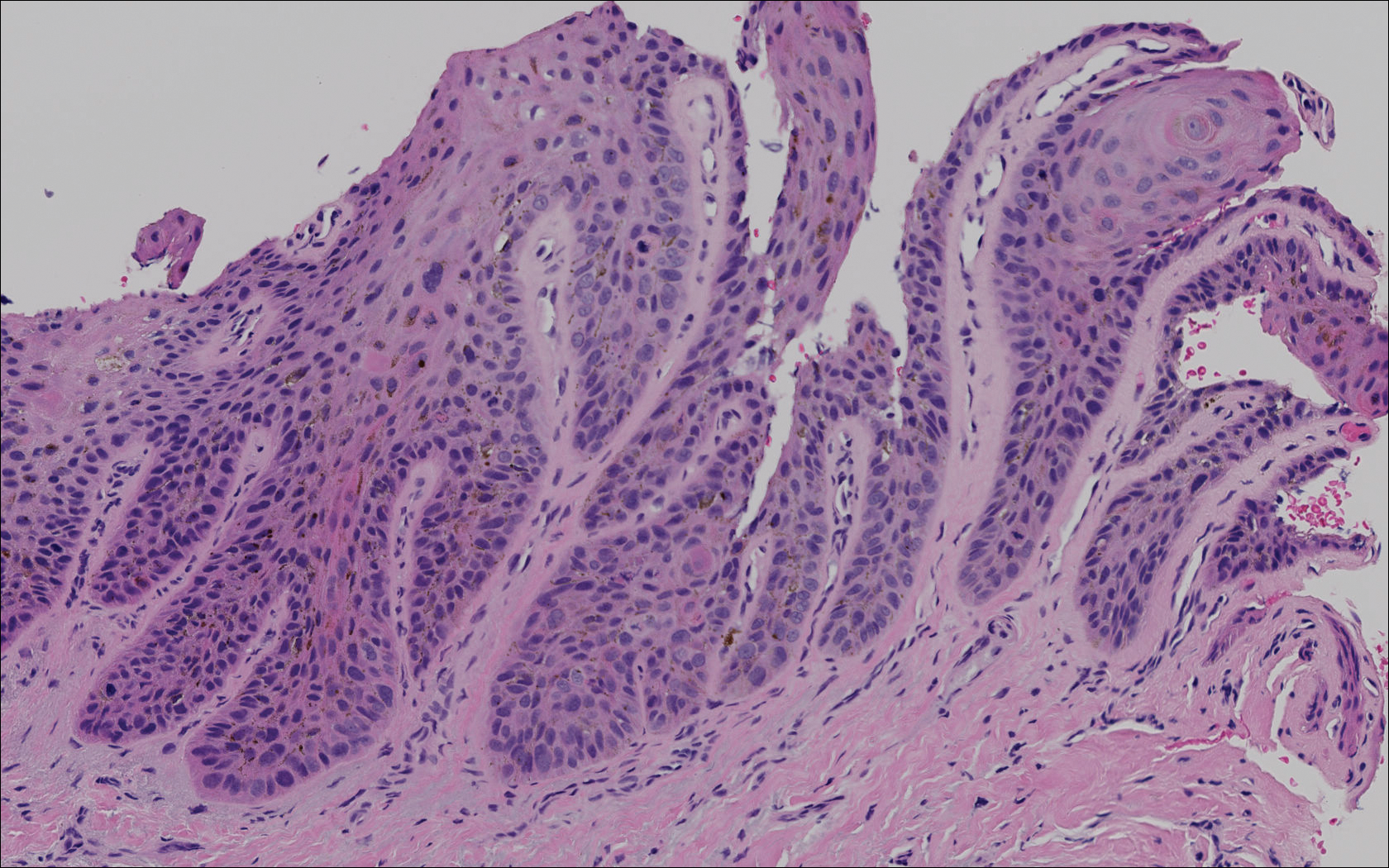

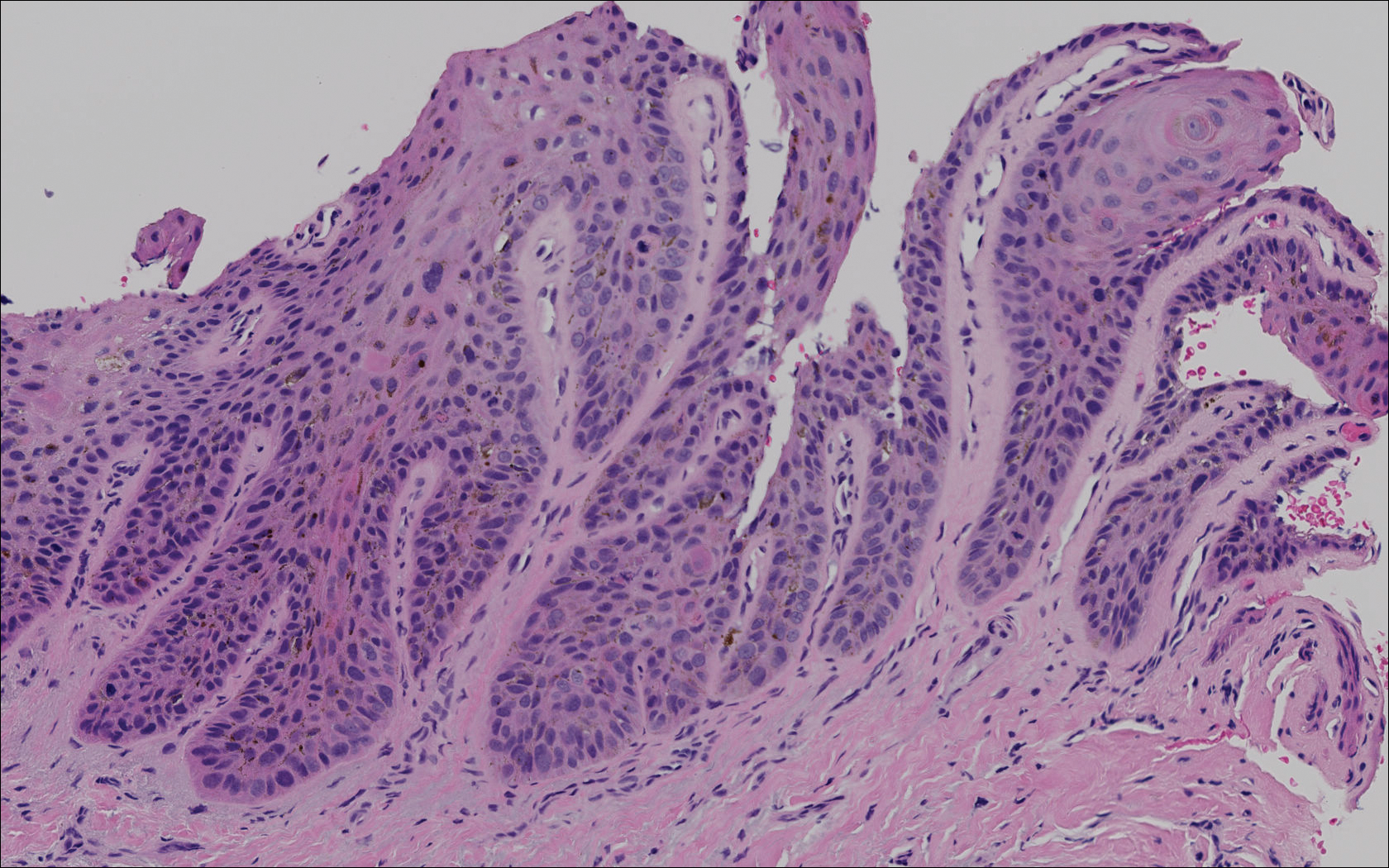

A 77-year-old man whose medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and numerous previous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) presented with a 5-cm, stellate, sclerotic plaque on the left chest of approximately 2 years’ duration (Figure 1) and a 3-mm pink papule on the right nasal sidewall of 2 months’ duration. Initial histology of both lesions revealed carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation extending from the undersurface of the epidermis, favoring a diagnosis of SEDC (Figure 2). At the time of initial presentation, the patient also had a 6-mm pink papule on the right chest of several months duration that was consistent with a well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma on histology.

Further analysis of the lesion on the left chest revealed positive staining for cytokeratin (CK) 5/14 and p63, suggestive of a cutaneous malignancy. Staining for S100 protein highlighted rare cells in the basal layer of tumor aggregates. The immunohistochemical profile showed negative staining for CK7, CK5D3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor 2.

Diagnosis of SEDC of the chest and nasal lesions was based on the morphologic architecture, which included ductal formation noted within the tumor. The chest lesion also had prominent squamoid differentiation. Another histologic feature consistent with SEDC was poorly demarcated, infiltrative neoplastic cells extending into the dermis and subcutis. Although there was some positive focal staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), variegation within the tumor and the prominent squamoid component might have contributed to this unexpected staining pattern.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for excision of the lesion on the chest wall. Initial workup revealed macrocytic anemia, which required transfusion, and an incidental finding of non–small-cell lung cancer. The chest lesion was unrelated to the non–small-cell lung cancer based on the staining profile. Material from the lung stained positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and exhibited rare staining for p63; however, the chest lesion did not stain positive for TTF-1 and had strong staining affinity for p63, indicative of a cutaneous malignancy.

The lesion on the chest wall was definitively excised. Pathologic analysis revealed a dermal-based infiltrative tumor of irregular nests and cords of squamoid cells with focal ductal formation in a fibromyxoid background stroma, suggestive of an adnexal carcinoma with a considerable degree of squamous differentiation and favoring a diagnosis of SEDC. Focal perineural invasion was noted, but no lymphovascular spread was identified; however, metastasis was identified in 1 of 26 axillary lymph nodes. The patient underwent 9 sessions of radiation therapy for the lung cancer and also was given cetuximab.

Three months later, the nasal tumor was subsequently excised in an outpatient procedure, and the final biopsy report indicated a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. One-and-a-half years later, in follow-up with surgery after removal of the chest lesion, a 2×3-cm mass was excised from the left neck that demonstrated lymph nodes consistent with metastatic SEDC. Careful evaluation of this patient, including family history and genetic screening, was considered. Our patient continues to follow-up with the dermatology department every 3 months. He has been doing well and has had multiple additional primary SCCs in the subsequent 5 years of follow-up.

Comment

Eccrine carcinoma is the most common subtype of adnexal carcinoma, representing 0.01% of all cutaneous tumors.1 S

Eccrine carcinoma is observed clinically as a slow-growing, nodular plaque on the scalp, arms, legs, or trunk in middle-aged and elderly individuals.1 Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma also has been reported in a young woman.5 Another immunocompromised patient was identified in the literature with a great toe lesion that showed follicular differentiation along with the usual SEDC features of squamoid and ductal differentiation.6 The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be an SCC arising from eccrine glands, a subtype of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation, or a biphenotypic carcinoma.1,7

Histologically, SEDC is poorly circumscribed with an infiltrative growth pattern and deep extension into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The lesion is characterized by prominent squamous epithelial proliferation superficially with cellular atypia, keratinous cyst formation, squamous eddies, and eccrine ductal differentiation.1

The differential diagnosis of SEDC includes SCC; metastatic carcinoma with squamoid features; and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Immunohistochemistry has a role in the diagnosis of SEDC. Findings include positive staining for S100 protein, EMA, CKs, and CEA. Glandular tissue stains positive for EMA and CEA, supporting an adnexal origin.1 Positivity for p63 and CK5/6 supports the conclusion that this is a primary cutaneous malignancy, not a metastatic disease.1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma has an indeterminate malignant potential. There is a disparity of clinical behavior between SCC and eccrine cancers; however, because squamous differentiation sometimes dominates the histological picture, eccrine carcinomas can be misdiagnosed as SCC.1,8 Eccrine adnexal tumors are characterized by multiple local recurrences (70%–80% of cases); perineural invasion; and metastasis (50% of cases) to regional lymph nodes and viscera, including the lungs, liver, bones, and brain.1 Squamous cell carcinoma, however, has a markedly lower recurrence rate (3.1%–18.7% of cases) and rate of metastasis (5.2%–37.8%).1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is classified as one of the less aggressive eccrine tumors, although the low number of cases makes it a controversial conclusion.1 To our knowledge, no cases of SEDC metastasis have been reported with SEDC. Recurrence of SEDC has been reported locally, and perineural or perivascular invasion (or both) has been demonstrated in 3 cases.1

Since SEDC has invasive and metastatic potential, as demonstrated in our case, along with elevated local recurrence rates, physicians must be able to properly diagnose this rare entity and recommend an appropriate surgical modality. Due to the low incidence of SEDC, there are no known randomized studies comparing treatment modalities.1 O

Surgical extirpation with complete margin examination is recommended, as SEDC tends to be underestimated in size, is aggressive in its infiltration, and is predisposed to perineural and perivascular invasion. T

Along with the rarity of SEDC in our patient, the simultaneous occurrence of 3 primary malignancies also is unusual. Patients with CLL have progressive defects of cell- and humoral-mediated immunity, causing immunosuppression. In a retrospective study, Tsimberidou et al9 reviewed the records of 2028 untreated CLL patients and determined that 27% had another primary malignancy, including skin (30%) and lung cancers (6%), which were two of the malignancies seen in our patient. The investigators concluded that patients with CLL have more than twice the risk of developing a second primary malignancy and an increased frequency of certain cancer types.9 Furthermore, treatment regimens for CLL have been considered to increase cell- and humoral-mediated immune defects at specific cancer sites,10 although the exact mechanism of this action is unknown. Development of a second primary malignancy (or even a third) in patients with SEDC is increasingly being reported in CLL patients.9,10

A high index of suspicion with SEDC in the differential diagnosis should be maintained in elderly men with slow-growing, solitary, nodular lesions of the scalp, nose, arms, legs, or trunk.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;916:799-802.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma)[published online April 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, McLaughlin P, et al. Other malignancies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:904-910.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT. Risk for second nonlymphoid neoplasms in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Gen Med. 2007;9:35.

Eccrine carcinomas are uncommon cutaneous neoplasms demonstrating nonuniform histologic features, behavior, and nomenclature. Given the rarity of these tumors, no known criteria by which to diagnose the tumor or guidelines for treatment have been proposed. We report a rare case of an immunocompromised patient with a primary squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) who was subsequently treated with radical resection and axillary dissection. It was later determined that the patient had distant metastasis of SEDC. A review of the literature on the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of SEDC also is provided.

Case Report

A 77-year-old man whose medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and numerous previous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) presented with a 5-cm, stellate, sclerotic plaque on the left chest of approximately 2 years’ duration (Figure 1) and a 3-mm pink papule on the right nasal sidewall of 2 months’ duration. Initial histology of both lesions revealed carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation extending from the undersurface of the epidermis, favoring a diagnosis of SEDC (Figure 2). At the time of initial presentation, the patient also had a 6-mm pink papule on the right chest of several months duration that was consistent with a well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma on histology.

Further analysis of the lesion on the left chest revealed positive staining for cytokeratin (CK) 5/14 and p63, suggestive of a cutaneous malignancy. Staining for S100 protein highlighted rare cells in the basal layer of tumor aggregates. The immunohistochemical profile showed negative staining for CK7, CK5D3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor 2.

Diagnosis of SEDC of the chest and nasal lesions was based on the morphologic architecture, which included ductal formation noted within the tumor. The chest lesion also had prominent squamoid differentiation. Another histologic feature consistent with SEDC was poorly demarcated, infiltrative neoplastic cells extending into the dermis and subcutis. Although there was some positive focal staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), variegation within the tumor and the prominent squamoid component might have contributed to this unexpected staining pattern.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for excision of the lesion on the chest wall. Initial workup revealed macrocytic anemia, which required transfusion, and an incidental finding of non–small-cell lung cancer. The chest lesion was unrelated to the non–small-cell lung cancer based on the staining profile. Material from the lung stained positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and exhibited rare staining for p63; however, the chest lesion did not stain positive for TTF-1 and had strong staining affinity for p63, indicative of a cutaneous malignancy.

The lesion on the chest wall was definitively excised. Pathologic analysis revealed a dermal-based infiltrative tumor of irregular nests and cords of squamoid cells with focal ductal formation in a fibromyxoid background stroma, suggestive of an adnexal carcinoma with a considerable degree of squamous differentiation and favoring a diagnosis of SEDC. Focal perineural invasion was noted, but no lymphovascular spread was identified; however, metastasis was identified in 1 of 26 axillary lymph nodes. The patient underwent 9 sessions of radiation therapy for the lung cancer and also was given cetuximab.

Three months later, the nasal tumor was subsequently excised in an outpatient procedure, and the final biopsy report indicated a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. One-and-a-half years later, in follow-up with surgery after removal of the chest lesion, a 2×3-cm mass was excised from the left neck that demonstrated lymph nodes consistent with metastatic SEDC. Careful evaluation of this patient, including family history and genetic screening, was considered. Our patient continues to follow-up with the dermatology department every 3 months. He has been doing well and has had multiple additional primary SCCs in the subsequent 5 years of follow-up.

Comment

Eccrine carcinoma is the most common subtype of adnexal carcinoma, representing 0.01% of all cutaneous tumors.1 S

Eccrine carcinoma is observed clinically as a slow-growing, nodular plaque on the scalp, arms, legs, or trunk in middle-aged and elderly individuals.1 Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma also has been reported in a young woman.5 Another immunocompromised patient was identified in the literature with a great toe lesion that showed follicular differentiation along with the usual SEDC features of squamoid and ductal differentiation.6 The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be an SCC arising from eccrine glands, a subtype of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation, or a biphenotypic carcinoma.1,7

Histologically, SEDC is poorly circumscribed with an infiltrative growth pattern and deep extension into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The lesion is characterized by prominent squamous epithelial proliferation superficially with cellular atypia, keratinous cyst formation, squamous eddies, and eccrine ductal differentiation.1

The differential diagnosis of SEDC includes SCC; metastatic carcinoma with squamoid features; and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Immunohistochemistry has a role in the diagnosis of SEDC. Findings include positive staining for S100 protein, EMA, CKs, and CEA. Glandular tissue stains positive for EMA and CEA, supporting an adnexal origin.1 Positivity for p63 and CK5/6 supports the conclusion that this is a primary cutaneous malignancy, not a metastatic disease.1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma has an indeterminate malignant potential. There is a disparity of clinical behavior between SCC and eccrine cancers; however, because squamous differentiation sometimes dominates the histological picture, eccrine carcinomas can be misdiagnosed as SCC.1,8 Eccrine adnexal tumors are characterized by multiple local recurrences (70%–80% of cases); perineural invasion; and metastasis (50% of cases) to regional lymph nodes and viscera, including the lungs, liver, bones, and brain.1 Squamous cell carcinoma, however, has a markedly lower recurrence rate (3.1%–18.7% of cases) and rate of metastasis (5.2%–37.8%).1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is classified as one of the less aggressive eccrine tumors, although the low number of cases makes it a controversial conclusion.1 To our knowledge, no cases of SEDC metastasis have been reported with SEDC. Recurrence of SEDC has been reported locally, and perineural or perivascular invasion (or both) has been demonstrated in 3 cases.1

Since SEDC has invasive and metastatic potential, as demonstrated in our case, along with elevated local recurrence rates, physicians must be able to properly diagnose this rare entity and recommend an appropriate surgical modality. Due to the low incidence of SEDC, there are no known randomized studies comparing treatment modalities.1 O

Surgical extirpation with complete margin examination is recommended, as SEDC tends to be underestimated in size, is aggressive in its infiltration, and is predisposed to perineural and perivascular invasion. T

Along with the rarity of SEDC in our patient, the simultaneous occurrence of 3 primary malignancies also is unusual. Patients with CLL have progressive defects of cell- and humoral-mediated immunity, causing immunosuppression. In a retrospective study, Tsimberidou et al9 reviewed the records of 2028 untreated CLL patients and determined that 27% had another primary malignancy, including skin (30%) and lung cancers (6%), which were two of the malignancies seen in our patient. The investigators concluded that patients with CLL have more than twice the risk of developing a second primary malignancy and an increased frequency of certain cancer types.9 Furthermore, treatment regimens for CLL have been considered to increase cell- and humoral-mediated immune defects at specific cancer sites,10 although the exact mechanism of this action is unknown. Development of a second primary malignancy (or even a third) in patients with SEDC is increasingly being reported in CLL patients.9,10

A high index of suspicion with SEDC in the differential diagnosis should be maintained in elderly men with slow-growing, solitary, nodular lesions of the scalp, nose, arms, legs, or trunk.

Eccrine carcinomas are uncommon cutaneous neoplasms demonstrating nonuniform histologic features, behavior, and nomenclature. Given the rarity of these tumors, no known criteria by which to diagnose the tumor or guidelines for treatment have been proposed. We report a rare case of an immunocompromised patient with a primary squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) who was subsequently treated with radical resection and axillary dissection. It was later determined that the patient had distant metastasis of SEDC. A review of the literature on the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of SEDC also is provided.

Case Report

A 77-year-old man whose medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and numerous previous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) presented with a 5-cm, stellate, sclerotic plaque on the left chest of approximately 2 years’ duration (Figure 1) and a 3-mm pink papule on the right nasal sidewall of 2 months’ duration. Initial histology of both lesions revealed carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation extending from the undersurface of the epidermis, favoring a diagnosis of SEDC (Figure 2). At the time of initial presentation, the patient also had a 6-mm pink papule on the right chest of several months duration that was consistent with a well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma on histology.

Further analysis of the lesion on the left chest revealed positive staining for cytokeratin (CK) 5/14 and p63, suggestive of a cutaneous malignancy. Staining for S100 protein highlighted rare cells in the basal layer of tumor aggregates. The immunohistochemical profile showed negative staining for CK7, CK5D3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor 2.

Diagnosis of SEDC of the chest and nasal lesions was based on the morphologic architecture, which included ductal formation noted within the tumor. The chest lesion also had prominent squamoid differentiation. Another histologic feature consistent with SEDC was poorly demarcated, infiltrative neoplastic cells extending into the dermis and subcutis. Although there was some positive focal staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), variegation within the tumor and the prominent squamoid component might have contributed to this unexpected staining pattern.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for excision of the lesion on the chest wall. Initial workup revealed macrocytic anemia, which required transfusion, and an incidental finding of non–small-cell lung cancer. The chest lesion was unrelated to the non–small-cell lung cancer based on the staining profile. Material from the lung stained positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and exhibited rare staining for p63; however, the chest lesion did not stain positive for TTF-1 and had strong staining affinity for p63, indicative of a cutaneous malignancy.

The lesion on the chest wall was definitively excised. Pathologic analysis revealed a dermal-based infiltrative tumor of irregular nests and cords of squamoid cells with focal ductal formation in a fibromyxoid background stroma, suggestive of an adnexal carcinoma with a considerable degree of squamous differentiation and favoring a diagnosis of SEDC. Focal perineural invasion was noted, but no lymphovascular spread was identified; however, metastasis was identified in 1 of 26 axillary lymph nodes. The patient underwent 9 sessions of radiation therapy for the lung cancer and also was given cetuximab.

Three months later, the nasal tumor was subsequently excised in an outpatient procedure, and the final biopsy report indicated a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. One-and-a-half years later, in follow-up with surgery after removal of the chest lesion, a 2×3-cm mass was excised from the left neck that demonstrated lymph nodes consistent with metastatic SEDC. Careful evaluation of this patient, including family history and genetic screening, was considered. Our patient continues to follow-up with the dermatology department every 3 months. He has been doing well and has had multiple additional primary SCCs in the subsequent 5 years of follow-up.

Comment

Eccrine carcinoma is the most common subtype of adnexal carcinoma, representing 0.01% of all cutaneous tumors.1 S

Eccrine carcinoma is observed clinically as a slow-growing, nodular plaque on the scalp, arms, legs, or trunk in middle-aged and elderly individuals.1 Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma also has been reported in a young woman.5 Another immunocompromised patient was identified in the literature with a great toe lesion that showed follicular differentiation along with the usual SEDC features of squamoid and ductal differentiation.6 The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be an SCC arising from eccrine glands, a subtype of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation, or a biphenotypic carcinoma.1,7

Histologically, SEDC is poorly circumscribed with an infiltrative growth pattern and deep extension into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The lesion is characterized by prominent squamous epithelial proliferation superficially with cellular atypia, keratinous cyst formation, squamous eddies, and eccrine ductal differentiation.1

The differential diagnosis of SEDC includes SCC; metastatic carcinoma with squamoid features; and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Immunohistochemistry has a role in the diagnosis of SEDC. Findings include positive staining for S100 protein, EMA, CKs, and CEA. Glandular tissue stains positive for EMA and CEA, supporting an adnexal origin.1 Positivity for p63 and CK5/6 supports the conclusion that this is a primary cutaneous malignancy, not a metastatic disease.1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma has an indeterminate malignant potential. There is a disparity of clinical behavior between SCC and eccrine cancers; however, because squamous differentiation sometimes dominates the histological picture, eccrine carcinomas can be misdiagnosed as SCC.1,8 Eccrine adnexal tumors are characterized by multiple local recurrences (70%–80% of cases); perineural invasion; and metastasis (50% of cases) to regional lymph nodes and viscera, including the lungs, liver, bones, and brain.1 Squamous cell carcinoma, however, has a markedly lower recurrence rate (3.1%–18.7% of cases) and rate of metastasis (5.2%–37.8%).1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is classified as one of the less aggressive eccrine tumors, although the low number of cases makes it a controversial conclusion.1 To our knowledge, no cases of SEDC metastasis have been reported with SEDC. Recurrence of SEDC has been reported locally, and perineural or perivascular invasion (or both) has been demonstrated in 3 cases.1

Since SEDC has invasive and metastatic potential, as demonstrated in our case, along with elevated local recurrence rates, physicians must be able to properly diagnose this rare entity and recommend an appropriate surgical modality. Due to the low incidence of SEDC, there are no known randomized studies comparing treatment modalities.1 O

Surgical extirpation with complete margin examination is recommended, as SEDC tends to be underestimated in size, is aggressive in its infiltration, and is predisposed to perineural and perivascular invasion. T

Along with the rarity of SEDC in our patient, the simultaneous occurrence of 3 primary malignancies also is unusual. Patients with CLL have progressive defects of cell- and humoral-mediated immunity, causing immunosuppression. In a retrospective study, Tsimberidou et al9 reviewed the records of 2028 untreated CLL patients and determined that 27% had another primary malignancy, including skin (30%) and lung cancers (6%), which were two of the malignancies seen in our patient. The investigators concluded that patients with CLL have more than twice the risk of developing a second primary malignancy and an increased frequency of certain cancer types.9 Furthermore, treatment regimens for CLL have been considered to increase cell- and humoral-mediated immune defects at specific cancer sites,10 although the exact mechanism of this action is unknown. Development of a second primary malignancy (or even a third) in patients with SEDC is increasingly being reported in CLL patients.9,10

A high index of suspicion with SEDC in the differential diagnosis should be maintained in elderly men with slow-growing, solitary, nodular lesions of the scalp, nose, arms, legs, or trunk.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;916:799-802.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma)[published online April 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, McLaughlin P, et al. Other malignancies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:904-910.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT. Risk for second nonlymphoid neoplasms in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Gen Med. 2007;9:35.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;916:799-802.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma)[published online April 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, McLaughlin P, et al. Other malignancies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:904-910.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT. Risk for second nonlymphoid neoplasms in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Gen Med. 2007;9:35.

Practice Points