User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Disseminated Vesicles and Necrotic Papules

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

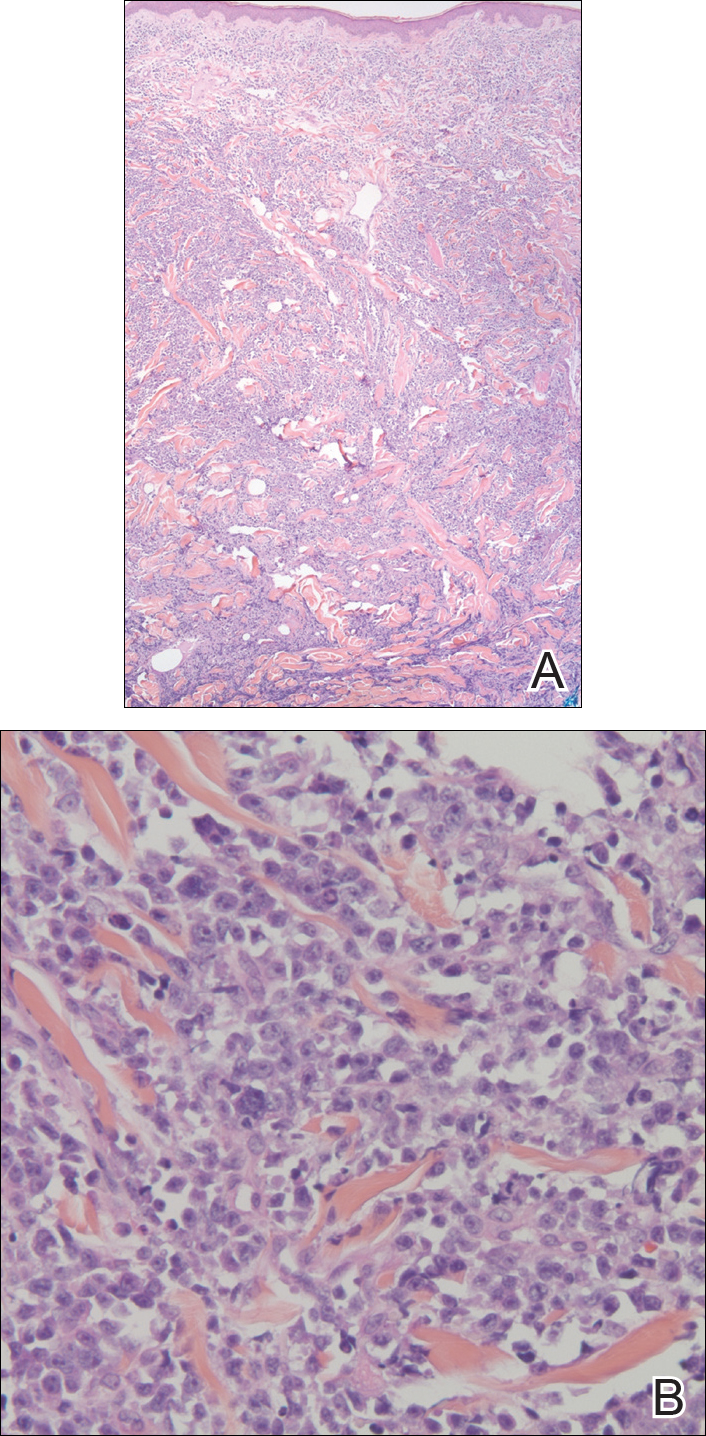

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

A 30-year-old man who had contracted human immunodeficiency virus from a male sexual partner 4 years prior presented to the emergency department with fevers, chills, night sweats, and rhinorrhea of 2 weeks' duration. He reported that he had been off highly active antiretroviral therapy for 2 years. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, papulonecrotic, crusted lesions on the face, neck, chest, back, arms, and legs that had developed over the past 4 days. Fluid-filled vesicles also were noted on the arms and legs, while erythematous, indurated nodules with overlying scaling were noted on the bilateral palms and soles. The patient reported that he had been vaccinated for varicella-zoster virus as a child without primary infection.

Cutting Edge Technology in Dermatology: Virtual Reality and Artificial Intelligence

The clinical practice of dermatology is changing at a rapid pace. Advances in technology and new inventions in rapid diagnostics are revolutionizing how physicians approach medical care.

Given these advances, how does today’s dermatologist integrate into the future of the specialty? If leveraged properly, current technologies such as teledermatology and patient portals integrated with electronic medical records can be beneficial to dermatology practices by improving access to care, facilitating triage of patients, and improving communication between patients and health care team members. Herein, we discuss some of the emerging technologies that have the potential to shape clinical dermatology practice and remove barriers to care.

Virtual Reality

Teledermatology can be practiced through live video or, more commonly, via a store-and-forward method in which dermatologists review clinical photographs and the patient's history asynchronously with the in-office visit.6 Virtual reality has the potential to augment teledermatology services by enabling a live, interactive visit that more closely models the traditional face-to-face visit. Virtual reality already is available for patients at home with the use of a commercially marketed headset and a smartphone, and the marriage of virtual reailty and telemedicine has the potential to transform health care.

Virtual reality also can be used to deliver an essential component of the physical examination of a patient: sensory information from palpation. Haptic feedback, also known as haptics, is used to relay force and tactile information to the user of a device (eg, a haptic glove).7 In dermatology, this information pertains to the skin texture, skin profile, and physical properties (eg, stiffness, temperature).8 Assessing the texture of the skin surface can help when distinguishing epidermal processes such as psoriasis versus atopic dermatitis or when evaluating edema, induration, and depth of a leg ulcer.9

One model for conducting a teledermatology encounter that captures sensory information would consist of a haptic probe located at a referring medical provider’s office for examining patients and a master robot that controls the probe located at the consulting dermatologist’s facility.8 Another model converts 2-dimensional images taken from traditional full-body optical imaging systems into virtual 3-dimensional (3D) images that can be felt using a haptic device.10,11 In this method, the user is able to both visualize and touch the skin surface at the same time. Currently, 3D imaging of skin lesions is available in the form of a specialized handheld imager that allows the dermatologist to appreciate the texture and elevation of single lesions when viewing clinical photographs. Additionally, full-body 3D mapping of the skin surface is available for monitoring pigmented lesions or other diseases of the skin.12,13

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Computer algorithms can be helpful in assisting physicians with disease diagnosis. Machine learning is a subfield of artificial intelligence (AI) in which computer programs learn automatically from experience without explicit programming instructions. A machine learning algorithm uses a labeled data set known as a training set to create a function that can make predictions about new inputs in the future.14 The algorithm can successively compare its predicted outputs with the correct outputs and modify its function as errors are found; for example, a database of images of healthy skin as well as the skin of psoriasis patients can be fed into a machine learning algorithm that picks up features such as color and skin texture from the labeled photographs, allowing it to learn how to diagnose psoriasis.15

In one instance, researchers at Stanford University (Stanford, California) used approximately 130,000 images representing over 2000 different skin diseases in order to train their machine learning algorithm to recognize benign and malignant skin lesions.4 Although the algorithm was able to match the performance of experienced dermatologists in many diagnostic categories, further testing in a real-world clinical setting still needs to be done. In the future, nondermatologists may have the option to consult with decision-support systems that include image analysis software, such as the one developed at Stanford University, for making decisions in triage or diagnosis, which may be critical in areas where access to a dermatologist is limited.4 Future AI systems also may provide supplemental assistance in managing patients to dermatology trainees until they have the experience of a more established dermatologist.

Currently, AI cannot match general human intelligence and life experience; therefore, physicians will continue to make the final decisions when it comes to diagnosis and treatment. In the future, AI algorithms may integrate into clinical dermatology practice, leading to more accurate triage of lesions, potentially streamlined referral to dermatologists for skin conditions that require prompt consultation, and improved quality of care.

Summary

In conclusion, emerging technologies have the power to augment and revolutionize dermatology practice. Savvy dermatologists may incorporate new tools in a way that works for their practice, leading to increased efficiency and improved patient outcomes. Eventually, the technology that is most beneficial to clinical practice will likely be adopted by and integrated into mainstream dermatologic care, making it available for the majority of clinicians to use.

- Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, Pub L No. 111-5, 123 Stat 226 (2009).

- Holmgren AJ, Adler-Milstein J. Health information exchange in US hospitals: the current landscape and a path to improved information sharing. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:193-198.

- The IMLC. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact website. http://www.imlcc.org. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118.

- The Associated Press. Microsoft eyes buffer zone in TV airwaves for rural internet. ABC News website. http://abcnews.go.com/amp/Technology/wireStory/microsoft-announces-rural-broadband-initiative-48562282. Published July 11, 2017. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Practice guidelines for dermatology. American Telemedicine Association website. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AMERICANTELEMED/3c09839a-fffd-46f7-916c-692c11d78933/UploadedImages/SIGs/Teledermatology.Final.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2018. Published April 28, 2016.

- Lee O, Lee K, Oh C, et al. Prototype tactile feedback system for examination by skin touch. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:307-314.

- Waldron KJ, Enedah C, Gladstone H. Stiffness and texture perception for teledermatology. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;111:579-585.

- Cox NH. A literally blinded trial of palpation in dermatologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:949-951.

- Kim K. Roughness based perceptual analysis towards digital skin imaging system with haptic feedback. Skin Res Technol. 2016;22:334-340.

- Kim K, Lee S. Perception-based 3D tactile rendering from a single image for human skin examinations by dynamic touch. Skin Res Technol. 2015;21:164-174.

- How it works. 3Derm website. https://www.3derm.com. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Vectra 3D. Canfield Scientific website. http://www.canfieldsci.com/imaging-systems/vectra-wb360-imaging-system. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Alpaydin E. Introduction to Machine Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2014.

- Shrivastava VK, Londhe ND, Sonawane RS, et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of psoriasis skin images with HOS, texture and color features: a first comparative study of its kind. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;126:98-109.

The clinical practice of dermatology is changing at a rapid pace. Advances in technology and new inventions in rapid diagnostics are revolutionizing how physicians approach medical care.

Given these advances, how does today’s dermatologist integrate into the future of the specialty? If leveraged properly, current technologies such as teledermatology and patient portals integrated with electronic medical records can be beneficial to dermatology practices by improving access to care, facilitating triage of patients, and improving communication between patients and health care team members. Herein, we discuss some of the emerging technologies that have the potential to shape clinical dermatology practice and remove barriers to care.

Virtual Reality

Teledermatology can be practiced through live video or, more commonly, via a store-and-forward method in which dermatologists review clinical photographs and the patient's history asynchronously with the in-office visit.6 Virtual reality has the potential to augment teledermatology services by enabling a live, interactive visit that more closely models the traditional face-to-face visit. Virtual reality already is available for patients at home with the use of a commercially marketed headset and a smartphone, and the marriage of virtual reailty and telemedicine has the potential to transform health care.

Virtual reality also can be used to deliver an essential component of the physical examination of a patient: sensory information from palpation. Haptic feedback, also known as haptics, is used to relay force and tactile information to the user of a device (eg, a haptic glove).7 In dermatology, this information pertains to the skin texture, skin profile, and physical properties (eg, stiffness, temperature).8 Assessing the texture of the skin surface can help when distinguishing epidermal processes such as psoriasis versus atopic dermatitis or when evaluating edema, induration, and depth of a leg ulcer.9

One model for conducting a teledermatology encounter that captures sensory information would consist of a haptic probe located at a referring medical provider’s office for examining patients and a master robot that controls the probe located at the consulting dermatologist’s facility.8 Another model converts 2-dimensional images taken from traditional full-body optical imaging systems into virtual 3-dimensional (3D) images that can be felt using a haptic device.10,11 In this method, the user is able to both visualize and touch the skin surface at the same time. Currently, 3D imaging of skin lesions is available in the form of a specialized handheld imager that allows the dermatologist to appreciate the texture and elevation of single lesions when viewing clinical photographs. Additionally, full-body 3D mapping of the skin surface is available for monitoring pigmented lesions or other diseases of the skin.12,13

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Computer algorithms can be helpful in assisting physicians with disease diagnosis. Machine learning is a subfield of artificial intelligence (AI) in which computer programs learn automatically from experience without explicit programming instructions. A machine learning algorithm uses a labeled data set known as a training set to create a function that can make predictions about new inputs in the future.14 The algorithm can successively compare its predicted outputs with the correct outputs and modify its function as errors are found; for example, a database of images of healthy skin as well as the skin of psoriasis patients can be fed into a machine learning algorithm that picks up features such as color and skin texture from the labeled photographs, allowing it to learn how to diagnose psoriasis.15

In one instance, researchers at Stanford University (Stanford, California) used approximately 130,000 images representing over 2000 different skin diseases in order to train their machine learning algorithm to recognize benign and malignant skin lesions.4 Although the algorithm was able to match the performance of experienced dermatologists in many diagnostic categories, further testing in a real-world clinical setting still needs to be done. In the future, nondermatologists may have the option to consult with decision-support systems that include image analysis software, such as the one developed at Stanford University, for making decisions in triage or diagnosis, which may be critical in areas where access to a dermatologist is limited.4 Future AI systems also may provide supplemental assistance in managing patients to dermatology trainees until they have the experience of a more established dermatologist.

Currently, AI cannot match general human intelligence and life experience; therefore, physicians will continue to make the final decisions when it comes to diagnosis and treatment. In the future, AI algorithms may integrate into clinical dermatology practice, leading to more accurate triage of lesions, potentially streamlined referral to dermatologists for skin conditions that require prompt consultation, and improved quality of care.

Summary

In conclusion, emerging technologies have the power to augment and revolutionize dermatology practice. Savvy dermatologists may incorporate new tools in a way that works for their practice, leading to increased efficiency and improved patient outcomes. Eventually, the technology that is most beneficial to clinical practice will likely be adopted by and integrated into mainstream dermatologic care, making it available for the majority of clinicians to use.

The clinical practice of dermatology is changing at a rapid pace. Advances in technology and new inventions in rapid diagnostics are revolutionizing how physicians approach medical care.

Given these advances, how does today’s dermatologist integrate into the future of the specialty? If leveraged properly, current technologies such as teledermatology and patient portals integrated with electronic medical records can be beneficial to dermatology practices by improving access to care, facilitating triage of patients, and improving communication between patients and health care team members. Herein, we discuss some of the emerging technologies that have the potential to shape clinical dermatology practice and remove barriers to care.

Virtual Reality

Teledermatology can be practiced through live video or, more commonly, via a store-and-forward method in which dermatologists review clinical photographs and the patient's history asynchronously with the in-office visit.6 Virtual reality has the potential to augment teledermatology services by enabling a live, interactive visit that more closely models the traditional face-to-face visit. Virtual reality already is available for patients at home with the use of a commercially marketed headset and a smartphone, and the marriage of virtual reailty and telemedicine has the potential to transform health care.

Virtual reality also can be used to deliver an essential component of the physical examination of a patient: sensory information from palpation. Haptic feedback, also known as haptics, is used to relay force and tactile information to the user of a device (eg, a haptic glove).7 In dermatology, this information pertains to the skin texture, skin profile, and physical properties (eg, stiffness, temperature).8 Assessing the texture of the skin surface can help when distinguishing epidermal processes such as psoriasis versus atopic dermatitis or when evaluating edema, induration, and depth of a leg ulcer.9

One model for conducting a teledermatology encounter that captures sensory information would consist of a haptic probe located at a referring medical provider’s office for examining patients and a master robot that controls the probe located at the consulting dermatologist’s facility.8 Another model converts 2-dimensional images taken from traditional full-body optical imaging systems into virtual 3-dimensional (3D) images that can be felt using a haptic device.10,11 In this method, the user is able to both visualize and touch the skin surface at the same time. Currently, 3D imaging of skin lesions is available in the form of a specialized handheld imager that allows the dermatologist to appreciate the texture and elevation of single lesions when viewing clinical photographs. Additionally, full-body 3D mapping of the skin surface is available for monitoring pigmented lesions or other diseases of the skin.12,13

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Computer algorithms can be helpful in assisting physicians with disease diagnosis. Machine learning is a subfield of artificial intelligence (AI) in which computer programs learn automatically from experience without explicit programming instructions. A machine learning algorithm uses a labeled data set known as a training set to create a function that can make predictions about new inputs in the future.14 The algorithm can successively compare its predicted outputs with the correct outputs and modify its function as errors are found; for example, a database of images of healthy skin as well as the skin of psoriasis patients can be fed into a machine learning algorithm that picks up features such as color and skin texture from the labeled photographs, allowing it to learn how to diagnose psoriasis.15

In one instance, researchers at Stanford University (Stanford, California) used approximately 130,000 images representing over 2000 different skin diseases in order to train their machine learning algorithm to recognize benign and malignant skin lesions.4 Although the algorithm was able to match the performance of experienced dermatologists in many diagnostic categories, further testing in a real-world clinical setting still needs to be done. In the future, nondermatologists may have the option to consult with decision-support systems that include image analysis software, such as the one developed at Stanford University, for making decisions in triage or diagnosis, which may be critical in areas where access to a dermatologist is limited.4 Future AI systems also may provide supplemental assistance in managing patients to dermatology trainees until they have the experience of a more established dermatologist.

Currently, AI cannot match general human intelligence and life experience; therefore, physicians will continue to make the final decisions when it comes to diagnosis and treatment. In the future, AI algorithms may integrate into clinical dermatology practice, leading to more accurate triage of lesions, potentially streamlined referral to dermatologists for skin conditions that require prompt consultation, and improved quality of care.

Summary

In conclusion, emerging technologies have the power to augment and revolutionize dermatology practice. Savvy dermatologists may incorporate new tools in a way that works for their practice, leading to increased efficiency and improved patient outcomes. Eventually, the technology that is most beneficial to clinical practice will likely be adopted by and integrated into mainstream dermatologic care, making it available for the majority of clinicians to use.

- Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, Pub L No. 111-5, 123 Stat 226 (2009).

- Holmgren AJ, Adler-Milstein J. Health information exchange in US hospitals: the current landscape and a path to improved information sharing. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:193-198.

- The IMLC. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact website. http://www.imlcc.org. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118.

- The Associated Press. Microsoft eyes buffer zone in TV airwaves for rural internet. ABC News website. http://abcnews.go.com/amp/Technology/wireStory/microsoft-announces-rural-broadband-initiative-48562282. Published July 11, 2017. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Practice guidelines for dermatology. American Telemedicine Association website. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AMERICANTELEMED/3c09839a-fffd-46f7-916c-692c11d78933/UploadedImages/SIGs/Teledermatology.Final.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2018. Published April 28, 2016.

- Lee O, Lee K, Oh C, et al. Prototype tactile feedback system for examination by skin touch. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:307-314.

- Waldron KJ, Enedah C, Gladstone H. Stiffness and texture perception for teledermatology. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;111:579-585.

- Cox NH. A literally blinded trial of palpation in dermatologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:949-951.

- Kim K. Roughness based perceptual analysis towards digital skin imaging system with haptic feedback. Skin Res Technol. 2016;22:334-340.

- Kim K, Lee S. Perception-based 3D tactile rendering from a single image for human skin examinations by dynamic touch. Skin Res Technol. 2015;21:164-174.

- How it works. 3Derm website. https://www.3derm.com. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Vectra 3D. Canfield Scientific website. http://www.canfieldsci.com/imaging-systems/vectra-wb360-imaging-system. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Alpaydin E. Introduction to Machine Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2014.

- Shrivastava VK, Londhe ND, Sonawane RS, et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of psoriasis skin images with HOS, texture and color features: a first comparative study of its kind. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;126:98-109.

- Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, Pub L No. 111-5, 123 Stat 226 (2009).

- Holmgren AJ, Adler-Milstein J. Health information exchange in US hospitals: the current landscape and a path to improved information sharing. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:193-198.

- The IMLC. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact website. http://www.imlcc.org. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115-118.

- The Associated Press. Microsoft eyes buffer zone in TV airwaves for rural internet. ABC News website. http://abcnews.go.com/amp/Technology/wireStory/microsoft-announces-rural-broadband-initiative-48562282. Published July 11, 2017. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Practice guidelines for dermatology. American Telemedicine Association website. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AMERICANTELEMED/3c09839a-fffd-46f7-916c-692c11d78933/UploadedImages/SIGs/Teledermatology.Final.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2018. Published April 28, 2016.

- Lee O, Lee K, Oh C, et al. Prototype tactile feedback system for examination by skin touch. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:307-314.

- Waldron KJ, Enedah C, Gladstone H. Stiffness and texture perception for teledermatology. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;111:579-585.

- Cox NH. A literally blinded trial of palpation in dermatologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:949-951.

- Kim K. Roughness based perceptual analysis towards digital skin imaging system with haptic feedback. Skin Res Technol. 2016;22:334-340.

- Kim K, Lee S. Perception-based 3D tactile rendering from a single image for human skin examinations by dynamic touch. Skin Res Technol. 2015;21:164-174.

- How it works. 3Derm website. https://www.3derm.com. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Vectra 3D. Canfield Scientific website. http://www.canfieldsci.com/imaging-systems/vectra-wb360-imaging-system. Accessed March 21, 2018.

- Alpaydin E. Introduction to Machine Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2014.

- Shrivastava VK, Londhe ND, Sonawane RS, et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of psoriasis skin images with HOS, texture and color features: a first comparative study of its kind. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;126:98-109.

Violaceous Plaques and Papulonodules on the Umbilicus

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Deposits Of Myeloma

Cutaneous deposits of myeloma are a rare skin manifestation of multiple myeloma that typically occur in less than 5% of patients.1,2 The lesions represent monoclonal proliferations of plasma cells and arise from direct extension of a neoplastic mass or less commonly from hematogenous or lymphatic spread. This secondary cutaneous involvement by plasma cell myeloma has been referred to in the literature as metastatic or extramedullary cutaneous plasmacytoma.1,2 This condition must be distinguished from cutaneous plasma cell infiltrates without underlying bone marrow involvement, classified by the World Health Organization as primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and previously referred to as primary cutaneous plasmacytoma.3

Clinically, cutaneous deposits of myeloma manifest as erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules with a smooth surface and firm consistency.1,2 The lesions typically occur on the trunk and less commonly on the head, neck, arms, and legs. In a review of 83 cases of metastatic cutaneous plasmacytoma and primary cutaneous plasmacytoma in multiple myeloma, Kato et al4 found that 52% (43/83) of cases occurred in IgG myelomas and 23% (19/83) in IgA myelomas.

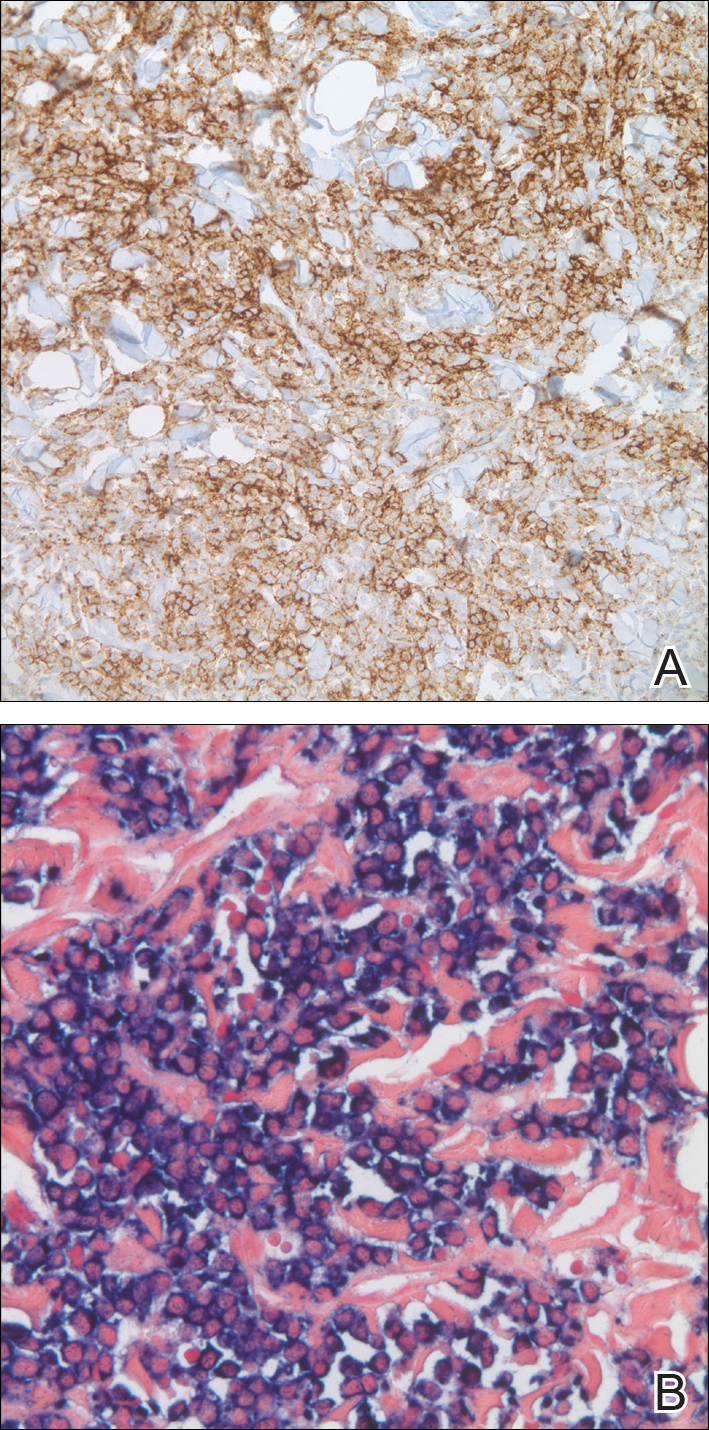

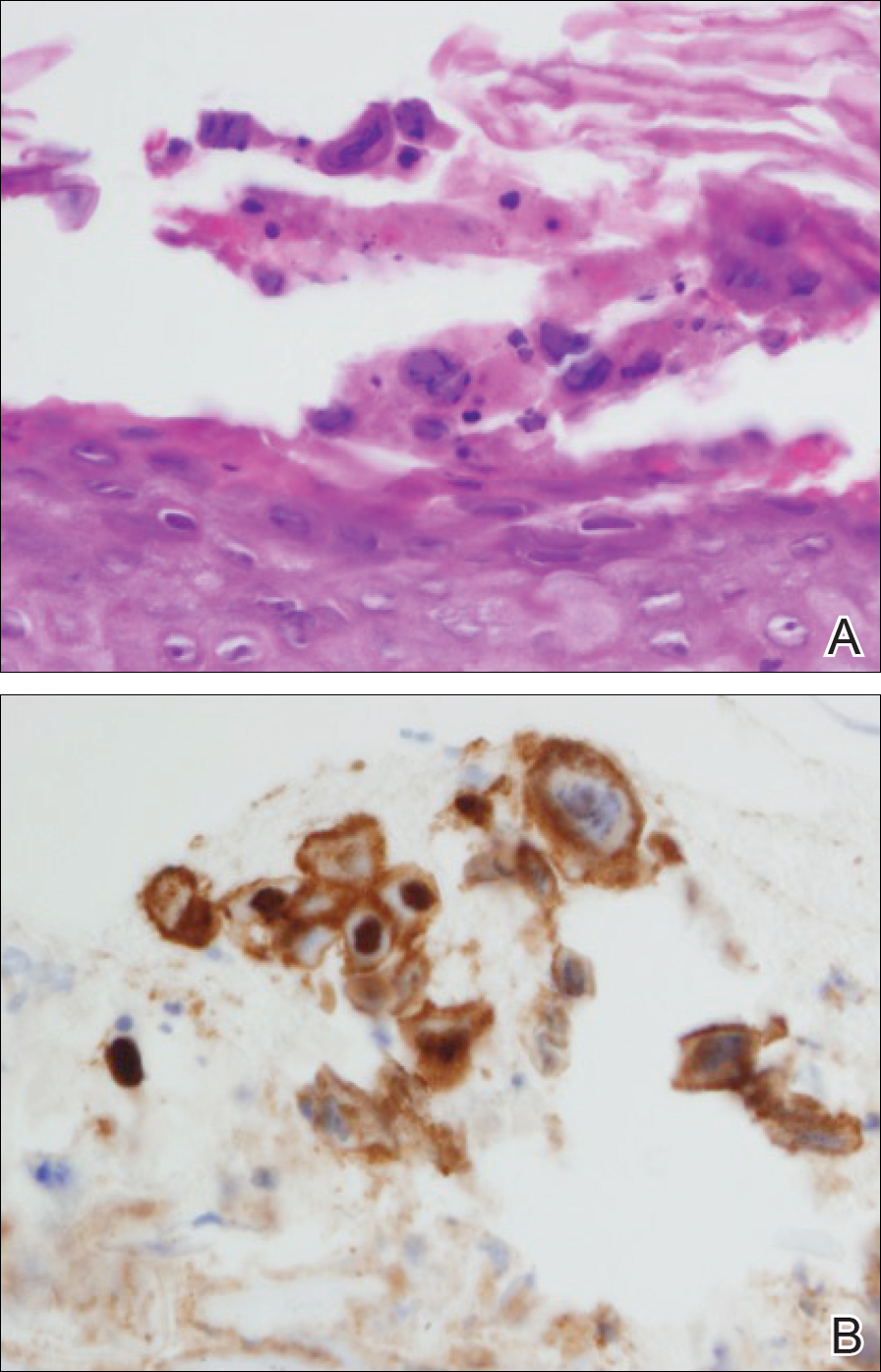

In our patient, a 4-mm punch biopsy of an umbilical plaque demonstrated a dense infiltrate of atypical plasmacytoid cells through the full thickness of the dermis with nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitoses (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for IgA λ light chain (Figure 2A) and CD138 (Figure 2B) and was negative for CD20, which was consistent with the patient's known plasma cell myeloma. Positron emission tomography revealed progression of underlying disease compared to prior studies with hypermetabolic mediastinal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic side wall lymphadenopathy, as well as extensive hypermetabolic soft tissue masses with involvement of the periumbilical region.

The differential diagnosis for violaceous periumbilical plaques includes cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (primary or secondary) or T-cell lymphoma (primary or secondary), cutaneous metastases from solid organ or hematologic malignancies (eg, Sister Mary Joseph nodule), AIDS-associated Kaposi sarcoma (plum-colored plaques that may be extensive), and cutaneous endometriosis (umbilical nodules that may develop in women after surgical excision of endometrial tissue).

The mainstay of therapy for secondary cutaneous involvement of plasma cell myeloma includes treatment with chemotherapy and local radiotherapy.1,2,5 After the diagnosis of cutaneous deposits of myeloma was made in our patient, he was treated with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide with dexamethasone, and local radiotherapy to symptomatic bony lesions; however, he was unresponsive to therapy and the disease progressed with numerous extramedullary lesions of the mediastinum, gastrointestinal tract, and retroperitoneum 2 months later. The patient developed hydronephrosis from external renal compression necessitating nephrostomy tube and malignant pleural effusions requiring intubation. He experienced rapid clinical decline and died 3 months after the initial presentation due to multiorgan failure.

Cutaneous deposits of myeloma are a sign of underlying disease progression in plasma cell myeloma and often herald a fulminant course (eg, death within 12 months of presentation), as seen in our patient.5 Clinicians should be aware of this rare manifestation of plasma cell myeloma and pursue aggressive therapy given the poor prognostic nature of these cutaneous findings.

- Jorizzo JL, Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Cutaneous plasmacytomas: a review and presentation of an unusual case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:59-66.

- Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The spectrum of cutaneous disease in multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:497-507.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Kato N, Kimura K, Yasukawa K, et al. Metastatic cutaneous plasmacytoma: a case report associated with IgA lambda multiple myeloma and a review of the literature of metastatic cutaneous plasmacytomas associated with multiple myeloma and primary cutaneous plasmacytomas. J Dermatol. 1999;26:587-594.

- Sanal SM, Yaylaci M, Mangold KA, et al. Extensive extramedullary disease in myeloma. an uncommon variant with features of poor prognosis and dedifferentiation. Cancer. 1996;77:1298-1302.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Deposits Of Myeloma

Cutaneous deposits of myeloma are a rare skin manifestation of multiple myeloma that typically occur in less than 5% of patients.1,2 The lesions represent monoclonal proliferations of plasma cells and arise from direct extension of a neoplastic mass or less commonly from hematogenous or lymphatic spread. This secondary cutaneous involvement by plasma cell myeloma has been referred to in the literature as metastatic or extramedullary cutaneous plasmacytoma.1,2 This condition must be distinguished from cutaneous plasma cell infiltrates without underlying bone marrow involvement, classified by the World Health Organization as primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and previously referred to as primary cutaneous plasmacytoma.3

Clinically, cutaneous deposits of myeloma manifest as erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules with a smooth surface and firm consistency.1,2 The lesions typically occur on the trunk and less commonly on the head, neck, arms, and legs. In a review of 83 cases of metastatic cutaneous plasmacytoma and primary cutaneous plasmacytoma in multiple myeloma, Kato et al4 found that 52% (43/83) of cases occurred in IgG myelomas and 23% (19/83) in IgA myelomas.

In our patient, a 4-mm punch biopsy of an umbilical plaque demonstrated a dense infiltrate of atypical plasmacytoid cells through the full thickness of the dermis with nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitoses (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for IgA λ light chain (Figure 2A) and CD138 (Figure 2B) and was negative for CD20, which was consistent with the patient's known plasma cell myeloma. Positron emission tomography revealed progression of underlying disease compared to prior studies with hypermetabolic mediastinal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic side wall lymphadenopathy, as well as extensive hypermetabolic soft tissue masses with involvement of the periumbilical region.

The differential diagnosis for violaceous periumbilical plaques includes cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (primary or secondary) or T-cell lymphoma (primary or secondary), cutaneous metastases from solid organ or hematologic malignancies (eg, Sister Mary Joseph nodule), AIDS-associated Kaposi sarcoma (plum-colored plaques that may be extensive), and cutaneous endometriosis (umbilical nodules that may develop in women after surgical excision of endometrial tissue).

The mainstay of therapy for secondary cutaneous involvement of plasma cell myeloma includes treatment with chemotherapy and local radiotherapy.1,2,5 After the diagnosis of cutaneous deposits of myeloma was made in our patient, he was treated with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide with dexamethasone, and local radiotherapy to symptomatic bony lesions; however, he was unresponsive to therapy and the disease progressed with numerous extramedullary lesions of the mediastinum, gastrointestinal tract, and retroperitoneum 2 months later. The patient developed hydronephrosis from external renal compression necessitating nephrostomy tube and malignant pleural effusions requiring intubation. He experienced rapid clinical decline and died 3 months after the initial presentation due to multiorgan failure.

Cutaneous deposits of myeloma are a sign of underlying disease progression in plasma cell myeloma and often herald a fulminant course (eg, death within 12 months of presentation), as seen in our patient.5 Clinicians should be aware of this rare manifestation of plasma cell myeloma and pursue aggressive therapy given the poor prognostic nature of these cutaneous findings.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Deposits Of Myeloma

Cutaneous deposits of myeloma are a rare skin manifestation of multiple myeloma that typically occur in less than 5% of patients.1,2 The lesions represent monoclonal proliferations of plasma cells and arise from direct extension of a neoplastic mass or less commonly from hematogenous or lymphatic spread. This secondary cutaneous involvement by plasma cell myeloma has been referred to in the literature as metastatic or extramedullary cutaneous plasmacytoma.1,2 This condition must be distinguished from cutaneous plasma cell infiltrates without underlying bone marrow involvement, classified by the World Health Organization as primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and previously referred to as primary cutaneous plasmacytoma.3

Clinically, cutaneous deposits of myeloma manifest as erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules with a smooth surface and firm consistency.1,2 The lesions typically occur on the trunk and less commonly on the head, neck, arms, and legs. In a review of 83 cases of metastatic cutaneous plasmacytoma and primary cutaneous plasmacytoma in multiple myeloma, Kato et al4 found that 52% (43/83) of cases occurred in IgG myelomas and 23% (19/83) in IgA myelomas.

In our patient, a 4-mm punch biopsy of an umbilical plaque demonstrated a dense infiltrate of atypical plasmacytoid cells through the full thickness of the dermis with nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitoses (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for IgA λ light chain (Figure 2A) and CD138 (Figure 2B) and was negative for CD20, which was consistent with the patient's known plasma cell myeloma. Positron emission tomography revealed progression of underlying disease compared to prior studies with hypermetabolic mediastinal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic side wall lymphadenopathy, as well as extensive hypermetabolic soft tissue masses with involvement of the periumbilical region.

The differential diagnosis for violaceous periumbilical plaques includes cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (primary or secondary) or T-cell lymphoma (primary or secondary), cutaneous metastases from solid organ or hematologic malignancies (eg, Sister Mary Joseph nodule), AIDS-associated Kaposi sarcoma (plum-colored plaques that may be extensive), and cutaneous endometriosis (umbilical nodules that may develop in women after surgical excision of endometrial tissue).

The mainstay of therapy for secondary cutaneous involvement of plasma cell myeloma includes treatment with chemotherapy and local radiotherapy.1,2,5 After the diagnosis of cutaneous deposits of myeloma was made in our patient, he was treated with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide with dexamethasone, and local radiotherapy to symptomatic bony lesions; however, he was unresponsive to therapy and the disease progressed with numerous extramedullary lesions of the mediastinum, gastrointestinal tract, and retroperitoneum 2 months later. The patient developed hydronephrosis from external renal compression necessitating nephrostomy tube and malignant pleural effusions requiring intubation. He experienced rapid clinical decline and died 3 months after the initial presentation due to multiorgan failure.

Cutaneous deposits of myeloma are a sign of underlying disease progression in plasma cell myeloma and often herald a fulminant course (eg, death within 12 months of presentation), as seen in our patient.5 Clinicians should be aware of this rare manifestation of plasma cell myeloma and pursue aggressive therapy given the poor prognostic nature of these cutaneous findings.

- Jorizzo JL, Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Cutaneous plasmacytomas: a review and presentation of an unusual case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:59-66.

- Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The spectrum of cutaneous disease in multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:497-507.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Kato N, Kimura K, Yasukawa K, et al. Metastatic cutaneous plasmacytoma: a case report associated with IgA lambda multiple myeloma and a review of the literature of metastatic cutaneous plasmacytomas associated with multiple myeloma and primary cutaneous plasmacytomas. J Dermatol. 1999;26:587-594.

- Sanal SM, Yaylaci M, Mangold KA, et al. Extensive extramedullary disease in myeloma. an uncommon variant with features of poor prognosis and dedifferentiation. Cancer. 1996;77:1298-1302.

- Jorizzo JL, Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Cutaneous plasmacytomas: a review and presentation of an unusual case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:59-66.

- Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The spectrum of cutaneous disease in multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:497-507.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Kato N, Kimura K, Yasukawa K, et al. Metastatic cutaneous plasmacytoma: a case report associated with IgA lambda multiple myeloma and a review of the literature of metastatic cutaneous plasmacytomas associated with multiple myeloma and primary cutaneous plasmacytomas. J Dermatol. 1999;26:587-594.

- Sanal SM, Yaylaci M, Mangold KA, et al. Extensive extramedullary disease in myeloma. an uncommon variant with features of poor prognosis and dedifferentiation. Cancer. 1996;77:1298-1302.

A 75-year-old man presented for evaluation of lesions on the umbilicus and lower abdomen that had developed over the past 4 weeks and were asymptomatic. His medical history was notable for plasma cell myeloma (stage III, IgA λ light chain restricted), deep vein thrombosis, and a 30-year history of smoking (20 packs per year). On physical examination, violaceous plaques and papulonodules were noted on the umbilicus. The lesions had a firm consistency and smooth surface without epidermal change. Violaceous papulonodules and subcutaneous plaques were noted on the lower abdomen. The lesions were nontender to palpation. Bilateral edema of the legs also was noted. The remainder of the skin was normal and there was no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

A Recalcitrant Case of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

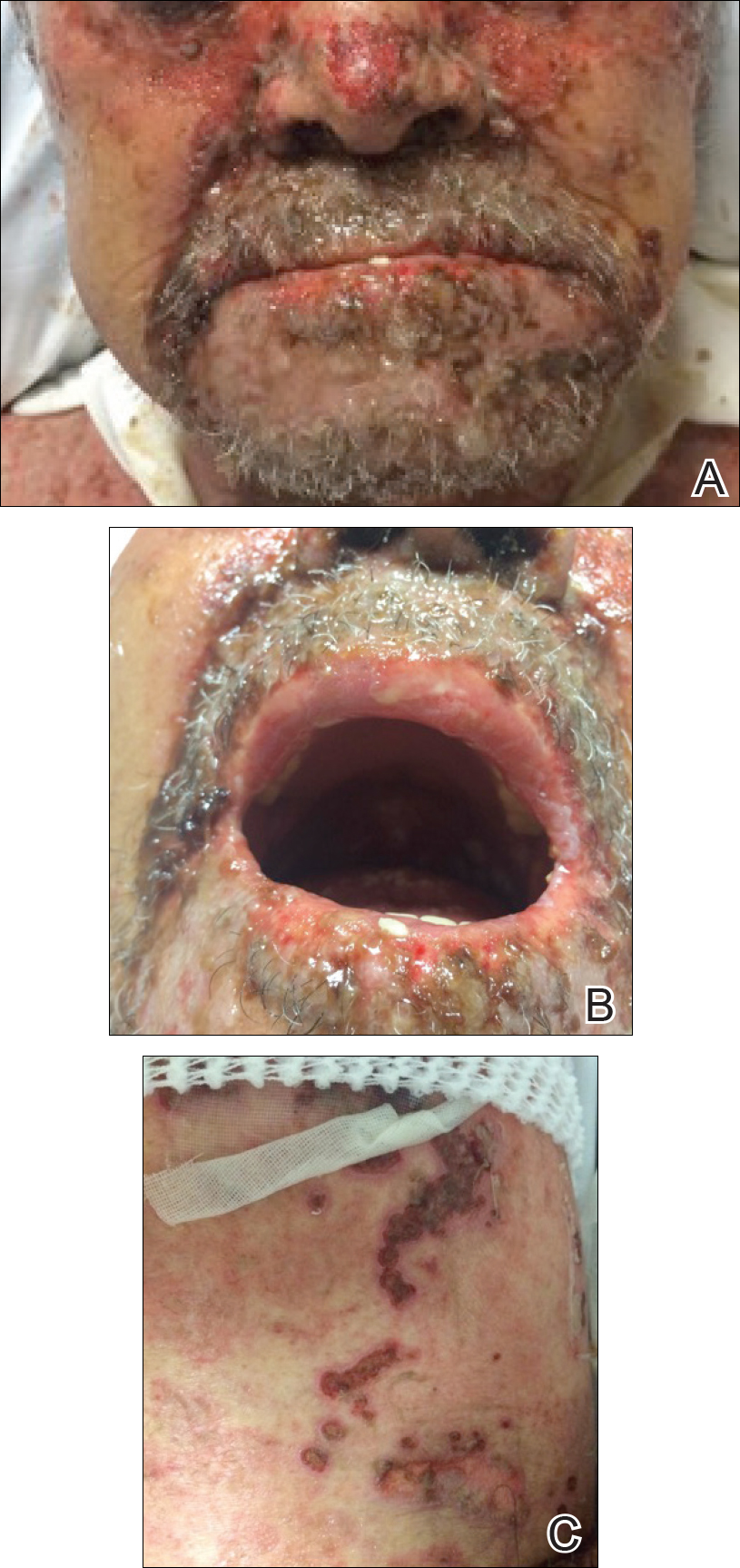

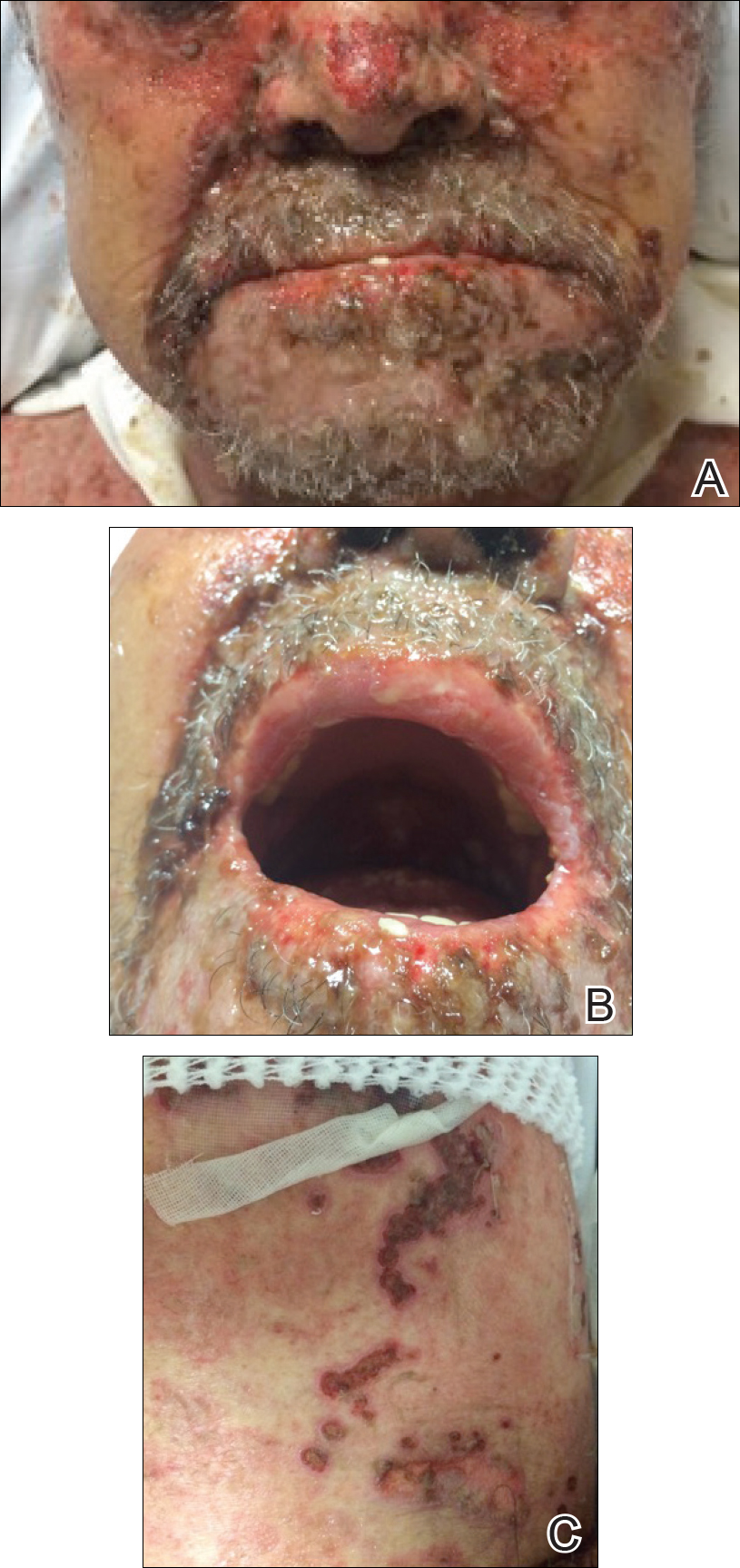

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)

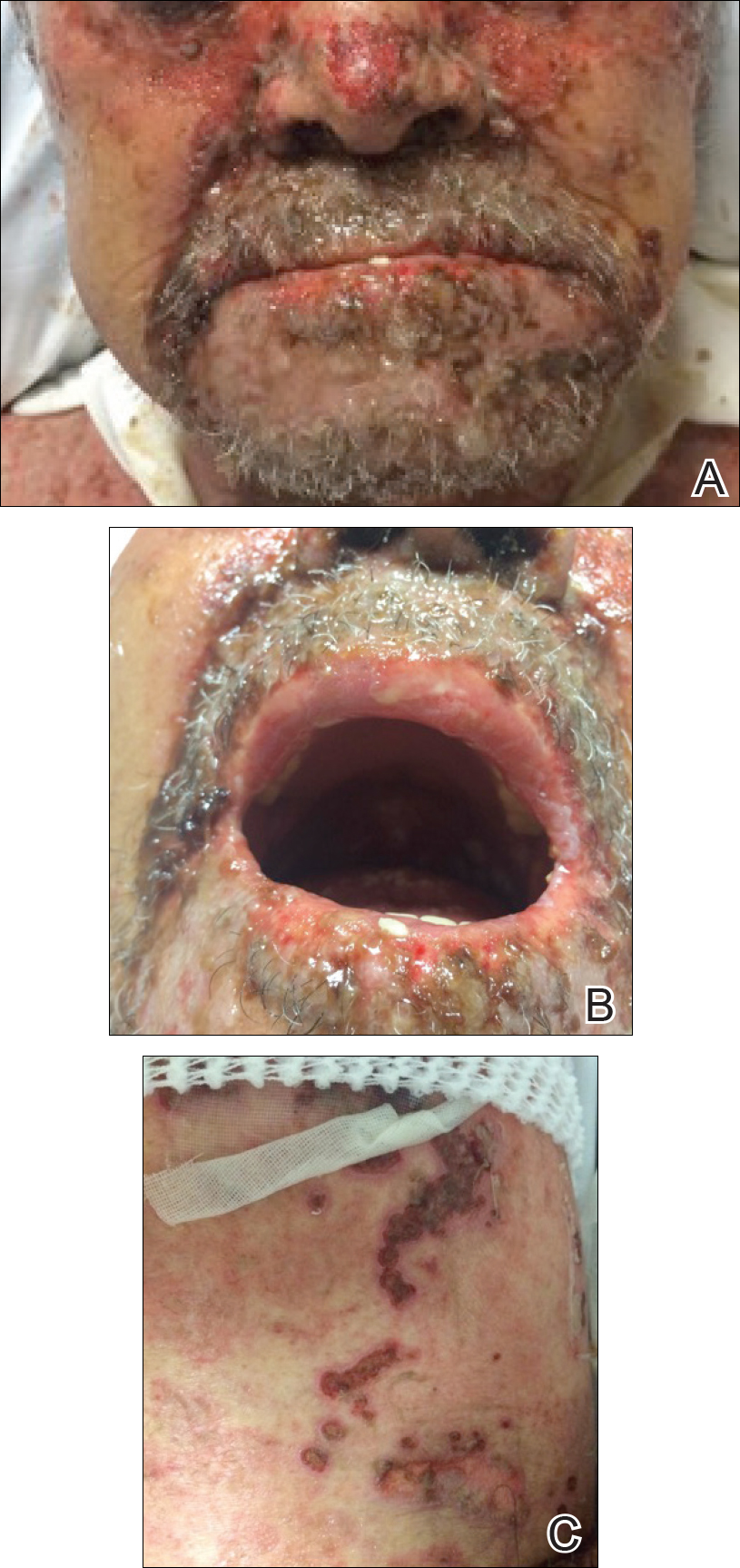

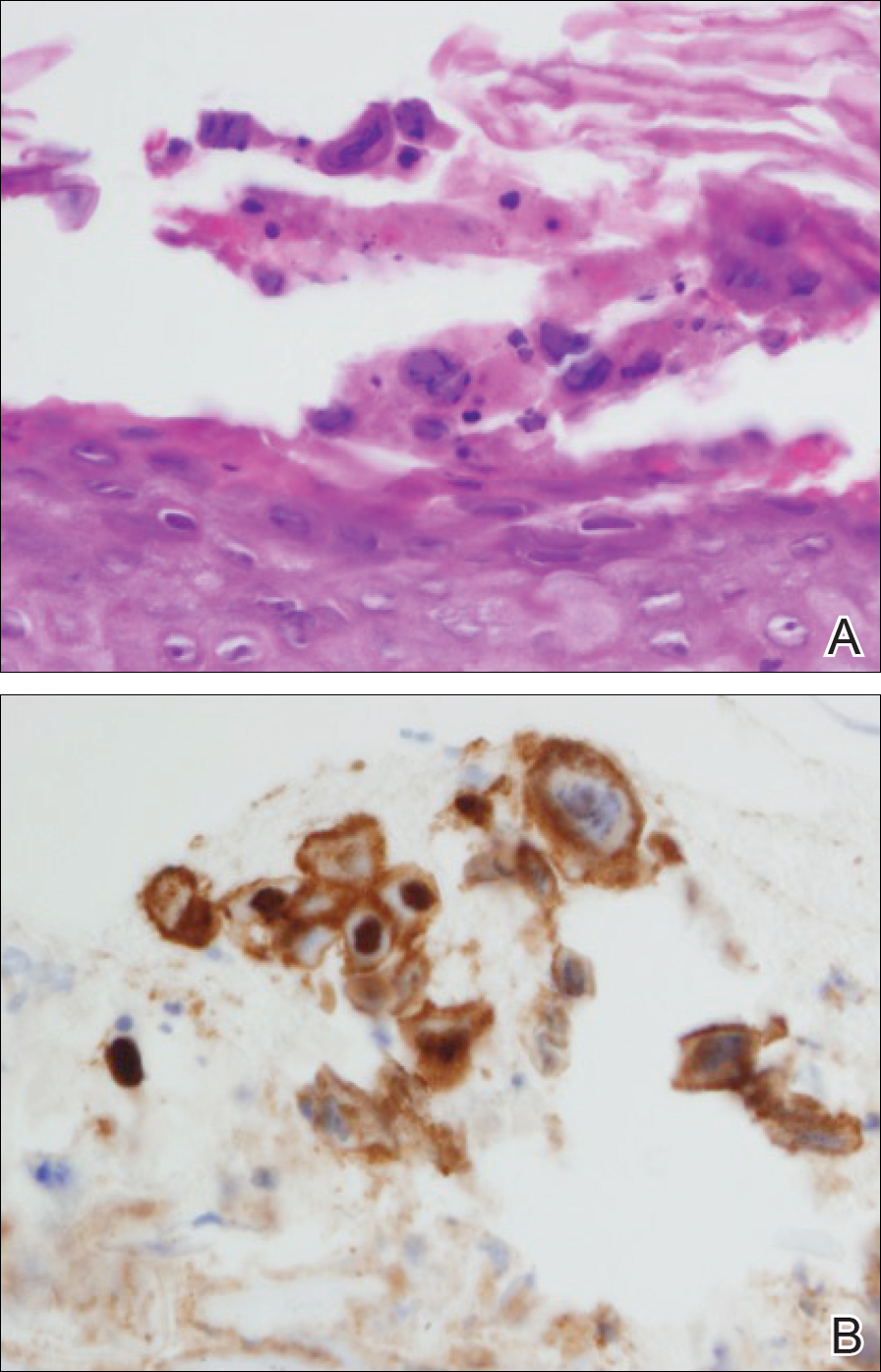

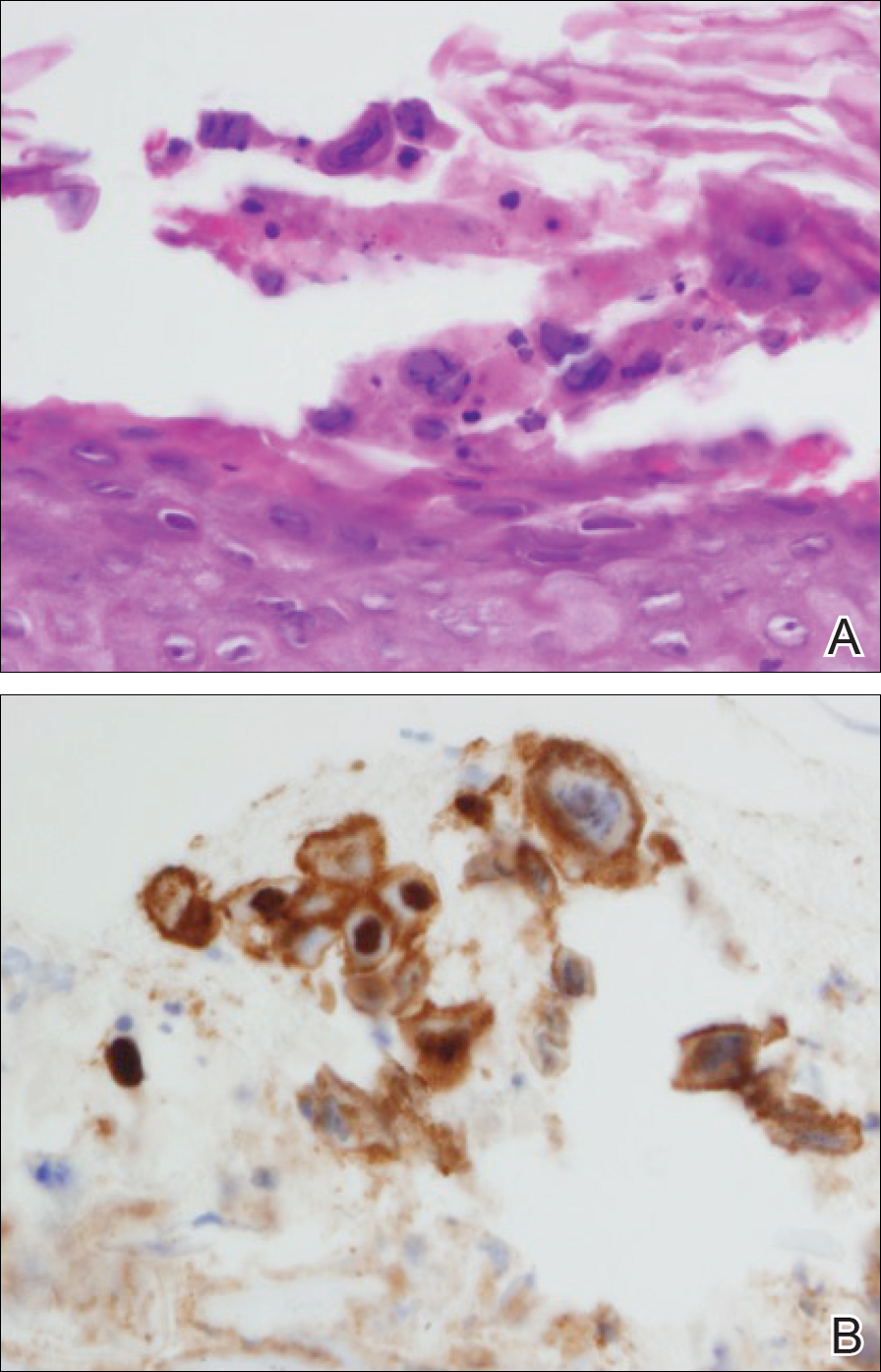

At that time, physical examination revealed numerous confluent erosions with honey-colored crust involving the entire face (Figure 1A) and sharp demarcation at the cutaneous lip (Figure 1B). There was a large erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral mucosa was spared. The trunk and proximal extremities showed numerous grouped, punched-out erosions with scalloped borders (Figure 1C). A repeat skin biopsy showed an ulcer with viral cytopathic changes. Immunoperoxidase studies demonstrated positive staining for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (Figure 2). The original slides were a frozen section from an outside facility and could not be obtained. A tissue culture and direct fluorescent antibody also confirmed HSV-1, and the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes. He was rapidly tapered off of the steroids and started on IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 21 days. All prior erosions reepithelialized within 7 days of treatment (Figure 3). The patient had an otherwise uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on hospital day 21.

Comment

A patient with an acute generalized blistering eruption requires urgent workup and treatment given the potentially devastating sequelae. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and immunobullous diseases often are the first diagnoses to be ruled out. Certainly infections such as HSV can cause a vesicular and erosive eruption, especially in the setting of a poorly controlled dermatitis, but they typically are not in the same differential as the other diagnoses.

Clinical Presentation

This case highlights 2 key physical examination findings that can alert the clinician to a possible underlying herpetic infection. First, the distribution of this patient’s oral lesions was telling. In most cases of TEN or pemphigus vulgaris, there is notable involvement of the oral mucosa, particularly the buccal and labial mucosa. Although herpes can involve any mucocutaneous surface, it does have a predilection for keratinized tissue, with the tongue and cutaneous lip commonly involved.2,3 Our patient had a solitary linear erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral cavity was strikingly spared. In addition, the erosions around the mouth stopped right at the cutaneous lip, sparing the labial mucosa (Figure 1B).

Second, the configuration of the erosions on the trunk, arms, and legs was diagnostic. Herpes classically presents as a cluster of vesicles overlying an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out erosions are left behind. Because these vesicles often are grouped, they can develop a scalloped border, which is a helpful indicator of HSV (Figure 1C). When these erosions become more confluent and irregular, the distinction from other conditions may not be as clear. A careful skin examination often can show areas that have preserved this herpetiform configuration.

Immune Compromise

Additionally, this case is illustrative of how immunosuppression and immunocompromise can affect the clinical presentation of HSV infection. Herpetic infections in the immunocompromised host tend to have a more protracted course, with chronic enlarging ulcers involving multiple sites.

Conclusion

This case is a good reminder that not everything that blisters and involves the mucosa is due to a hypersensitivity state such as TEN and Stevens-Johnson syndrome or an immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans. The fact that this patient was worsening despite drug cessation, high-dose steroids, and IV immunoglobulin should have indicated a misdiagnosis. This case also shows that the early histopathologic findings of disseminated HSV and TEN can be nonspecific, and viral cytopathic changes may not always be obvious early in the disease.

Disseminated HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, and careful history and physical examination should be taken to rule out a viral etiology.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008.

- Woo SB, Lee SF. Oral recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:239-243.

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)

At that time, physical examination revealed numerous confluent erosions with honey-colored crust involving the entire face (Figure 1A) and sharp demarcation at the cutaneous lip (Figure 1B). There was a large erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral mucosa was spared. The trunk and proximal extremities showed numerous grouped, punched-out erosions with scalloped borders (Figure 1C). A repeat skin biopsy showed an ulcer with viral cytopathic changes. Immunoperoxidase studies demonstrated positive staining for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (Figure 2). The original slides were a frozen section from an outside facility and could not be obtained. A tissue culture and direct fluorescent antibody also confirmed HSV-1, and the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes. He was rapidly tapered off of the steroids and started on IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 21 days. All prior erosions reepithelialized within 7 days of treatment (Figure 3). The patient had an otherwise uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on hospital day 21.

Comment

A patient with an acute generalized blistering eruption requires urgent workup and treatment given the potentially devastating sequelae. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and immunobullous diseases often are the first diagnoses to be ruled out. Certainly infections such as HSV can cause a vesicular and erosive eruption, especially in the setting of a poorly controlled dermatitis, but they typically are not in the same differential as the other diagnoses.

Clinical Presentation

This case highlights 2 key physical examination findings that can alert the clinician to a possible underlying herpetic infection. First, the distribution of this patient’s oral lesions was telling. In most cases of TEN or pemphigus vulgaris, there is notable involvement of the oral mucosa, particularly the buccal and labial mucosa. Although herpes can involve any mucocutaneous surface, it does have a predilection for keratinized tissue, with the tongue and cutaneous lip commonly involved.2,3 Our patient had a solitary linear erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral cavity was strikingly spared. In addition, the erosions around the mouth stopped right at the cutaneous lip, sparing the labial mucosa (Figure 1B).

Second, the configuration of the erosions on the trunk, arms, and legs was diagnostic. Herpes classically presents as a cluster of vesicles overlying an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out erosions are left behind. Because these vesicles often are grouped, they can develop a scalloped border, which is a helpful indicator of HSV (Figure 1C). When these erosions become more confluent and irregular, the distinction from other conditions may not be as clear. A careful skin examination often can show areas that have preserved this herpetiform configuration.

Immune Compromise

Additionally, this case is illustrative of how immunosuppression and immunocompromise can affect the clinical presentation of HSV infection. Herpetic infections in the immunocompromised host tend to have a more protracted course, with chronic enlarging ulcers involving multiple sites.

Conclusion

This case is a good reminder that not everything that blisters and involves the mucosa is due to a hypersensitivity state such as TEN and Stevens-Johnson syndrome or an immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans. The fact that this patient was worsening despite drug cessation, high-dose steroids, and IV immunoglobulin should have indicated a misdiagnosis. This case also shows that the early histopathologic findings of disseminated HSV and TEN can be nonspecific, and viral cytopathic changes may not always be obvious early in the disease.

Disseminated HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, and careful history and physical examination should be taken to rule out a viral etiology.

One of the most severe complications of systemic medications is the development of a life-threatening rash, especially toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Most patients can expect a full recovery if the complicating medication is discontinued early on in its course.1 When suspected TEN does not improve despite discontinuation of the detrimental medication, other diseases must be considered, particularly immunobullous and infectious etiologies. Treatment of these diseases differs substantially; therefore, a quick diagnosis is crucial. We present a case of a patient with an acute blistering eruption that was initially diagnosed and managed as TEN but physical examination and histopathologic confirmed another diagnosis. We review key examination findings that can help differentiate the causes of an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Case Report

An 85-year-old immunocompetent man was admitted to an outside hospital with a pruritic blistering eruption associated with myalgia, weakness, and fatigue of 3 weeks’ duration. The eruption initiated on the scalp and face and then spread down to the trunk and proximal arms and legs, with oral erosions also reported. An outside dermatologist was consulted on admission and performed a skin biopsy; the initial pathology was read as TEN. The patient was admitted to our institution on the same day, and all potentially complicating medications were stopped. He was treated with intravenous (IV)

At that time, physical examination revealed numerous confluent erosions with honey-colored crust involving the entire face (Figure 1A) and sharp demarcation at the cutaneous lip (Figure 1B). There was a large erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral mucosa was spared. The trunk and proximal extremities showed numerous grouped, punched-out erosions with scalloped borders (Figure 1C). A repeat skin biopsy showed an ulcer with viral cytopathic changes. Immunoperoxidase studies demonstrated positive staining for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (Figure 2). The original slides were a frozen section from an outside facility and could not be obtained. A tissue culture and direct fluorescent antibody also confirmed HSV-1, and the patient was diagnosed with disseminated herpes. He was rapidly tapered off of the steroids and started on IV acyclovir 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 21 days. All prior erosions reepithelialized within 7 days of treatment (Figure 3). The patient had an otherwise uncomplicated hospital course and was discharged on hospital day 21.

Comment

A patient with an acute generalized blistering eruption requires urgent workup and treatment given the potentially devastating sequelae. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and immunobullous diseases often are the first diagnoses to be ruled out. Certainly infections such as HSV can cause a vesicular and erosive eruption, especially in the setting of a poorly controlled dermatitis, but they typically are not in the same differential as the other diagnoses.

Clinical Presentation

This case highlights 2 key physical examination findings that can alert the clinician to a possible underlying herpetic infection. First, the distribution of this patient’s oral lesions was telling. In most cases of TEN or pemphigus vulgaris, there is notable involvement of the oral mucosa, particularly the buccal and labial mucosa. Although herpes can involve any mucocutaneous surface, it does have a predilection for keratinized tissue, with the tongue and cutaneous lip commonly involved.2,3 Our patient had a solitary linear erosion on the dorsal aspect of the tongue, but the rest of the oral cavity was strikingly spared. In addition, the erosions around the mouth stopped right at the cutaneous lip, sparing the labial mucosa (Figure 1B).

Second, the configuration of the erosions on the trunk, arms, and legs was diagnostic. Herpes classically presents as a cluster of vesicles overlying an erythematous base. When these vesicles rupture, punched-out erosions are left behind. Because these vesicles often are grouped, they can develop a scalloped border, which is a helpful indicator of HSV (Figure 1C). When these erosions become more confluent and irregular, the distinction from other conditions may not be as clear. A careful skin examination often can show areas that have preserved this herpetiform configuration.

Immune Compromise

Additionally, this case is illustrative of how immunosuppression and immunocompromise can affect the clinical presentation of HSV infection. Herpetic infections in the immunocompromised host tend to have a more protracted course, with chronic enlarging ulcers involving multiple sites.

Conclusion

This case is a good reminder that not everything that blisters and involves the mucosa is due to a hypersensitivity state such as TEN and Stevens-Johnson syndrome or an immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans. The fact that this patient was worsening despite drug cessation, high-dose steroids, and IV immunoglobulin should have indicated a misdiagnosis. This case also shows that the early histopathologic findings of disseminated HSV and TEN can be nonspecific, and viral cytopathic changes may not always be obvious early in the disease.

Disseminated HSV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an acute blistering eruption with mucosal involvement, and careful history and physical examination should be taken to rule out a viral etiology.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008.

- Woo SB, Lee SF. Oral recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:239-243.

- Schwartz RA, McDonough PH, Lee BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part I. introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:173.e1-173.e13.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008.

- Woo SB, Lee SF. Oral recrudescent herpes simplex virus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:239-243.

Practice Points

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis can be difficult to diagnose and treat.

- Patients who are refractory to treatment should prompt further management considerations.

Increasing Diversity in the Dermatology Workforce

Brown-Black Papulonodules on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Glochid Dermatitis

Biopsy of a nodule on the upper right arm showed chronic granulomatous inflammation and polarizable foreign material consistent with plant cellulose (Figure). A diagnosis of glochid dermatitis was made. The treatment plan included follow-up skin evaluation and punch excision of persistent papules 1 month after the initial presentation. The patient reported the rash began after he fell on a cactus plant while chasing his grandson. He was seen by various clinicians and was given hydrocortisone and clobetasol, which helped with pruritis but did not resolve the rash. His grandson developed a similar rash at the site of contact with the cactus plant. The patient and his grandson did not detect the presence of any cactus spines.

Injuries from cactus glochids most often occur due to accidental falls on cactus plants, but glochids also may be transferred from clothing to other individuals. The thin, hairlike glochids easily detach from the stem of the cactus and can become deeply embedded with virtually no pressure.1

Glochid implantation from the prickly pear cactus commonly presents as a pruritic papular eruption known as glochid dermatitis. These penetrating injuries can lead to inoculation of Clostridium tetani and Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, unrecognized and unremoved cactus spines may be highly inflammatory and may cause chronic granulomatous inflammation.2

Initially, acute glochid dermatitis occurs due to mechanical damage caused by the detatched cactus spine and may not resolve for up to 4 months. Granuloma formation has been reported several weeks after exposure and may persist for more than 8 months.3 Although an immune mechanism has been suggested, the literature has indicated that delayed hypersensitivity reactions are a more probable cause of the granulomatous inflammation after glochid exposure.3 Madkan et al4 reported that relatively few patients developed granulomas after implantation of glochids in the skin, thus suggesting that granuloma formation is an allergic response.

With regard to the pathogenesis of glochid dermatitis, the initial response to foreign plant matter in the dermis involves a neutrophilic infiltrate, which later is replaced by histiocytes; however, the foreign material remains undegraded in the macrophage cytoplasm.5 Activated macrophages secrete cytokines that intensify the inflammatory response, resulting in formation of a granuloma around the foreign body. The granuloma acts as a wall to isolate the foreign matter from the rest of the body.5