User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Rituximab Treatment and Improvement of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Pemphigus

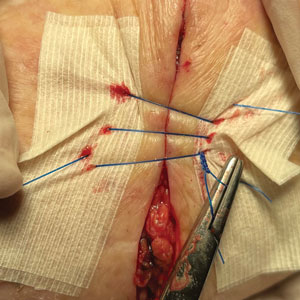

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune blistering diseases characterized by the development of painful and flaccid blisters on the skin and/or mucous membranes. Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF) are 2 major subtypes and can be distinguished by the location of blister formation or the specificity of autoantibodies directed against different desmogleins.1,2 Although rare, pemphigus is considered a serious and life-threatening condition with a great impact on quality of life (QOL) due to disease symptoms (eg, painful lesions, physical appearance of skin lesions) as well as treatment complications (eg, adverse drug effects, cost of treatment).3-6 Moreover, the physical and psychological effects can lead to marked functional morbidity and work-related disability during patients’ productive years.7 Therefore, affected individuals usually have a remarkably compromised health-related quality of life (HRQOL).8 Effective treatments may considerably improve the QOL of patients with pemphigus.6

Despite the available treatment options, finding the best regimen for pemphigus remains a challenge. Corticosteroids are assumed to be the main treatment, though they have considerable side effects.9,10 Adjuvant therapies are used to suppress or modulate immune responses, leading to remission with the least possible need for corticosteroids. Finding an optimal steroid-sparing agent has been the aim of research, and biologic agents seem to be the best option.8 Rituximab (RTX), an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has shown great promise in several studies of its clinical efficacy and has become a first-line treatment in new guidelines.11-14 Rituximab treatment has been associated with notable improvement in physician-assessed outcome measures with a favorable safety profile in patients with pemphigus.11-15 However, it is important to assess response to treatment from a patient’s perspective through the use of outcome-assessment measures that encompass patient-reported outcomes to reflect the complete patient experience and establish the overall impact of RTX as well as its likelihood of acceptance by patients with pemphigus.

In our study, we compared clinical outcomes and HRQOL through the use of disease-specific measures as well as comprehensive generic health status measures among patients with PV and PF who received RTX treatment 3 months earlier and those who received RTX in the last 2 weeks. The clinical relevance of the patient-reported outcomes is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a single-center cross-sectional study of 96 patients with pemphigus aged 18 to 65 years of either sex who were willing to participate in this study. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PV or PF who received RTX 3 months earlier or in the last 2 weeks were enrolled in the study. Patients were identified using Dermatry.ir, an archiving software that contains patients’ medical data. Exclusion criteria included lack of sufficient knowledge of the concepts of the questionnaires as well as age younger than 16 years. The study was conducted from October 2019 to April 2020 by the Autoimmune Bullous Disease Research Center at Razi Hospital in Tehran, Iran, which is the main dermatology-specific center and teaching hospital of Iran. The study protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committee.

Patients were categorized into 2 groups: (1) those who received RTX 3 months earlier (3M group); and (2) those who received RTX in the last 2 weeks (R group).

After an explanation of the study to participants, informed written consent was signed by each patient, and their personal data (eg, age, sex, education, marital status, smoking status), as well as clinical data (eg, type of pemphigus, duration of disease, site of onset, prednisolone dosage, presence of Nikolsky sign, anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values, Pemphigus Disease Area Index [PDAI] score, RTX treatment protocol); any known comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or morbid obesity; and any chronic pulmonary, cardiac, endocrinologic, renal, or hepatic condition, were collected and recorded in a predefined Case Record.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

The effect of RTX on QOL in patients with pemphigus was assessed using 2 HRQOL instruments: (1) a general health status indicator, the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36), and (2) a validated, Persian version of a dermatology-specific questionnaire, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The questionnaires were completed by each patient or by an assistant if needed.

The SF-36 is a widely used 36-item questionnaire measuring functional health and well-being across 8 domains—mental health, pain, physical function, role emotional, role physical, social functioning, vitality, and general health perception—with scores for each ranging from 0 to 100. The physical component scores (PCSs) and mental component scores (MCSs) were derived from these 8 subscales, each ranging from 0 to 400, with higher scores indicating better health status.6

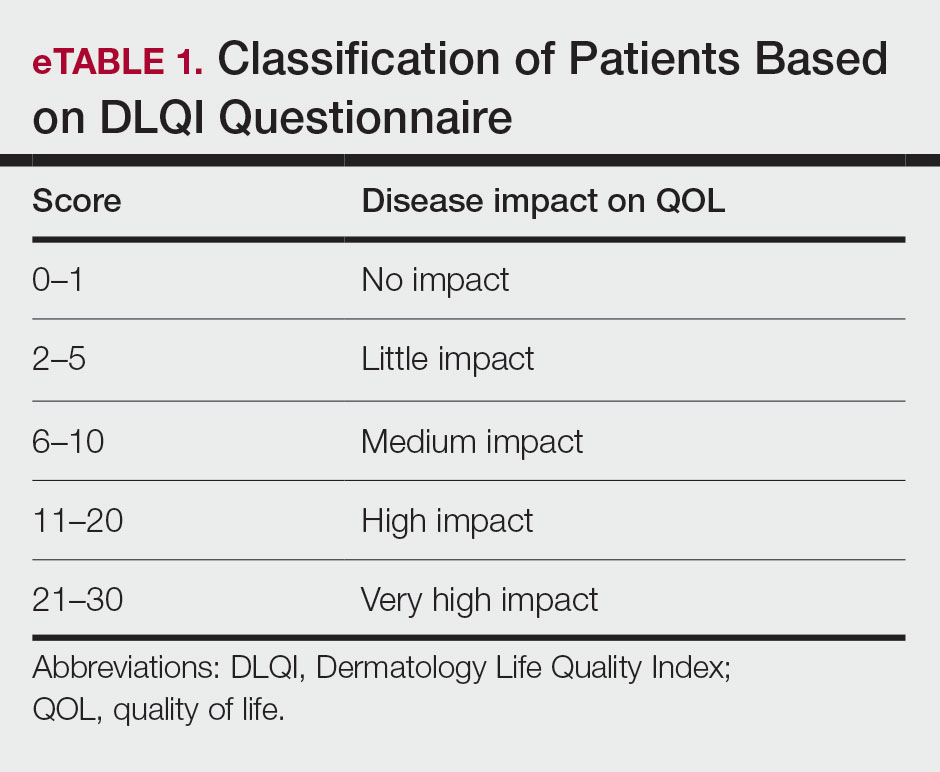

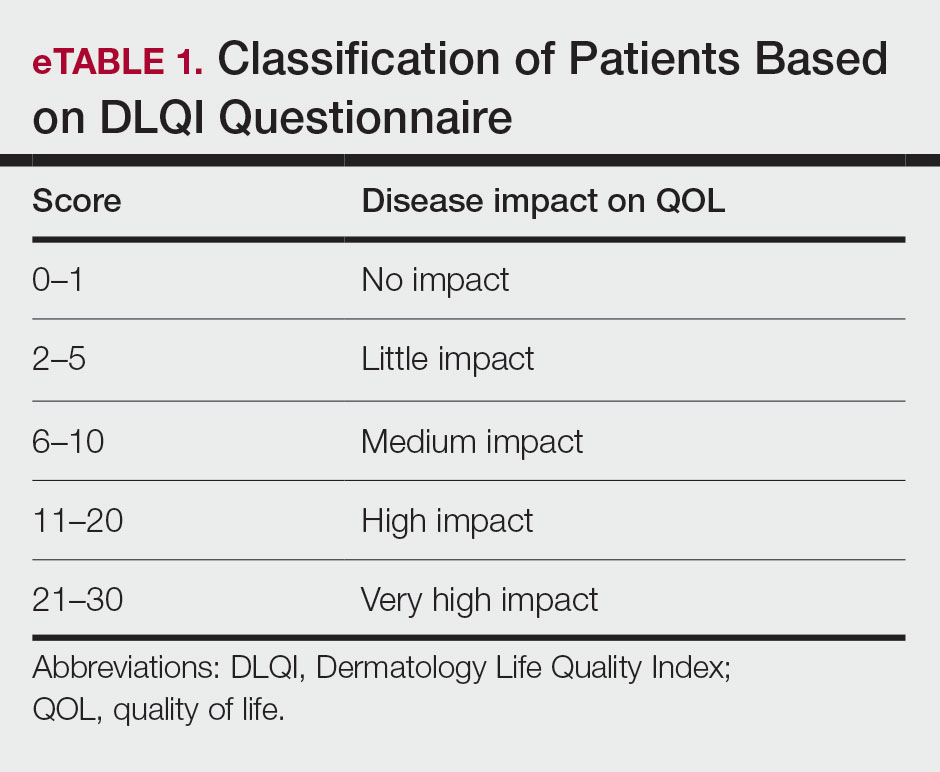

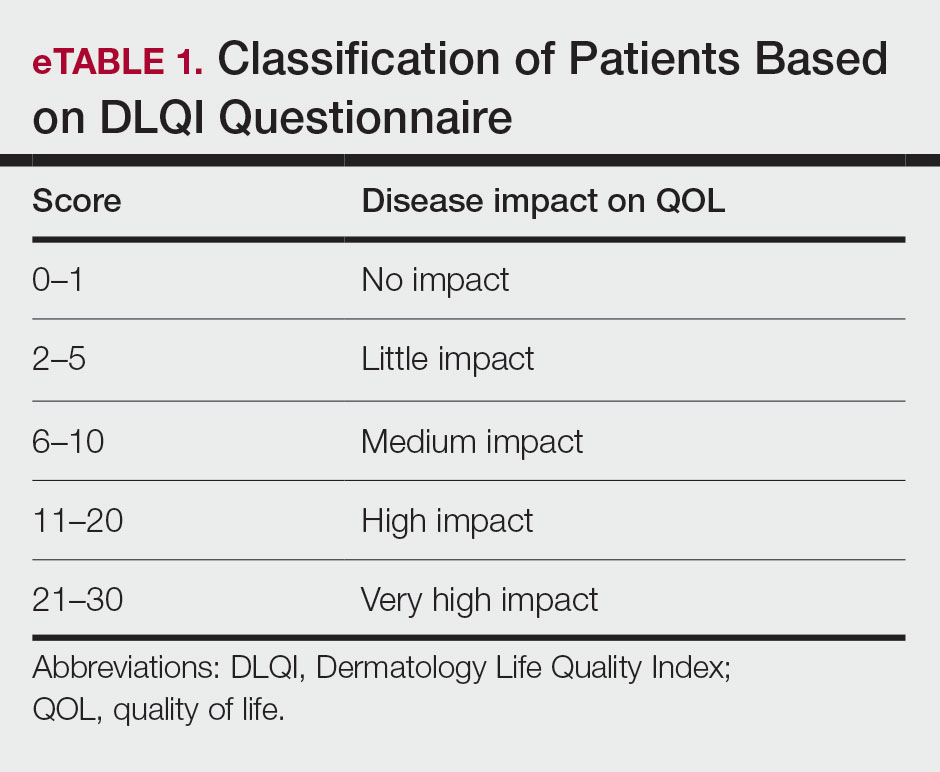

The DLQI, one of the most frequently used QOL measures in dermatology, contains 10 questions, each referring to the prior week and classified in the following 6 subscales: symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, personal relationships, work and school, and treatment.16 The total score ranges from 0 (no impact) to 30 (very high impact), with a higher score indicating a lower QOL (eTable 1). The minimal clinically important difference (MCD) for the DLQI was considered to be 2- to 5-point changes in prior studies.17,18 In this study, we used an MCD of a 5-point change or more between study groups.

Moreover, the patient general assessment (PGA) of disease severity was identified using a 3-point scale (1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 23. P≤.05 was considered significant. Mean and SD were calculated for descriptive data. The t test, Fisher exact test, analysis of variance, multiple regression analysis, and logistic regression analysis were used to identify the relationship between variables.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

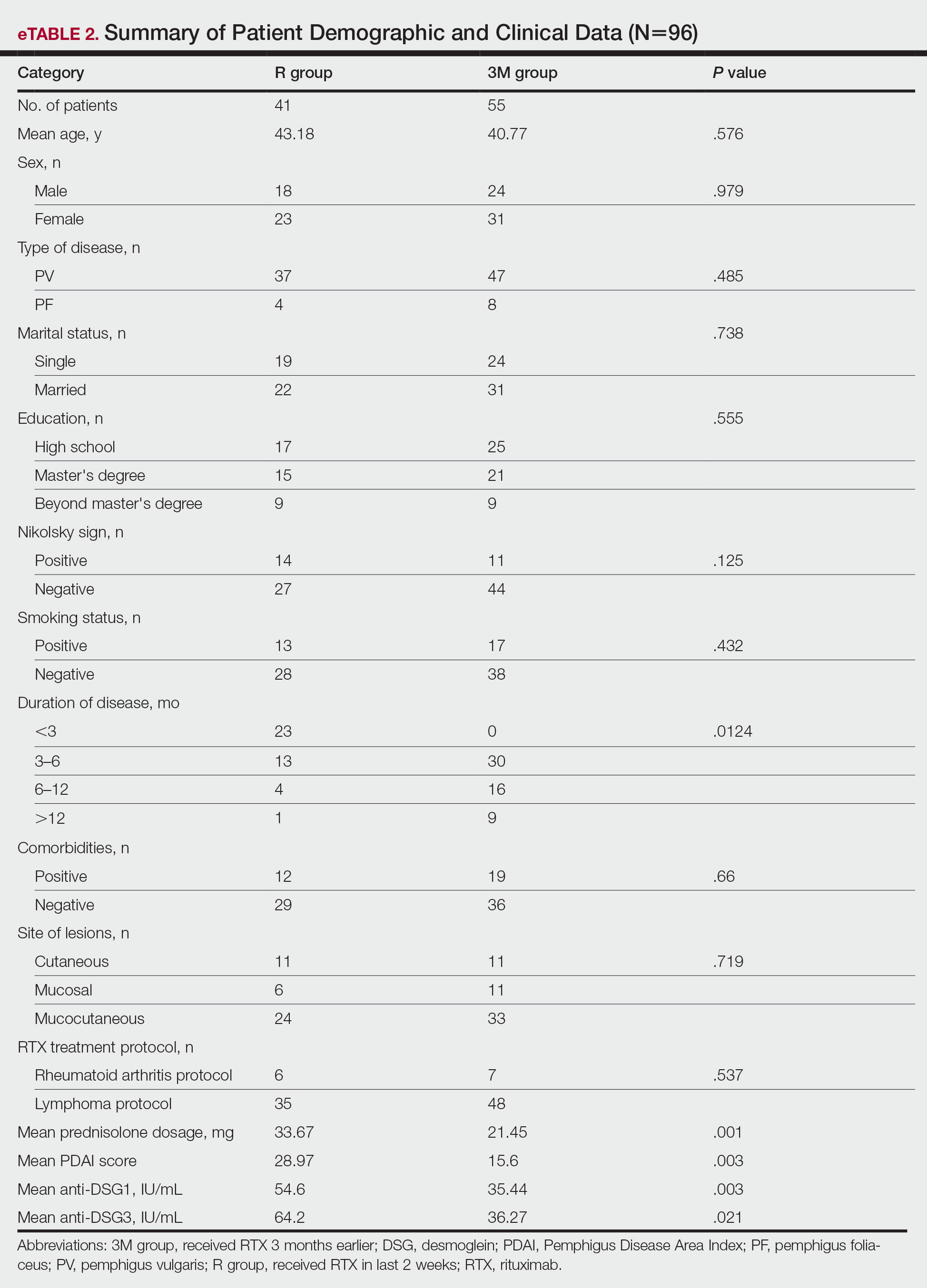

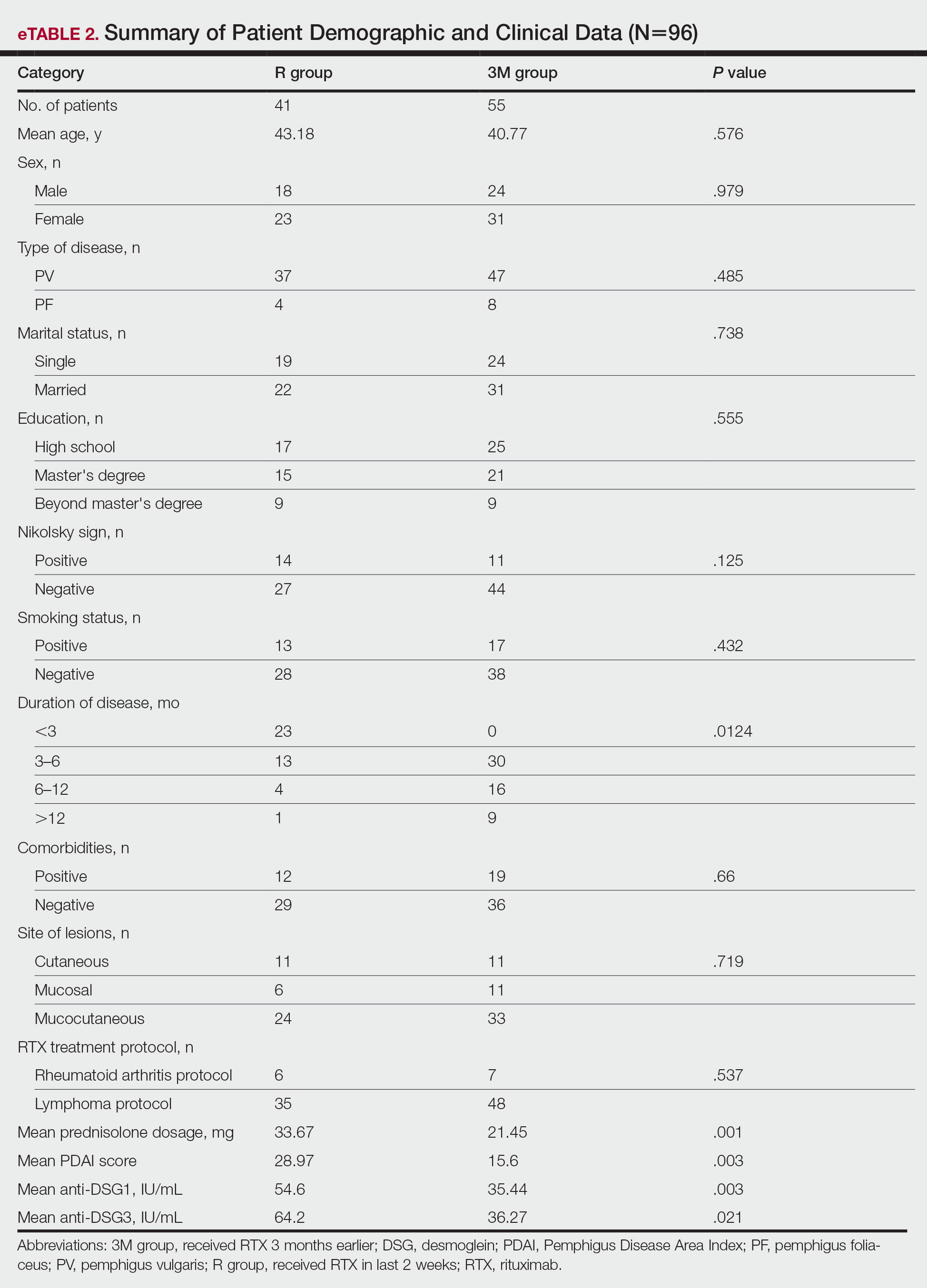

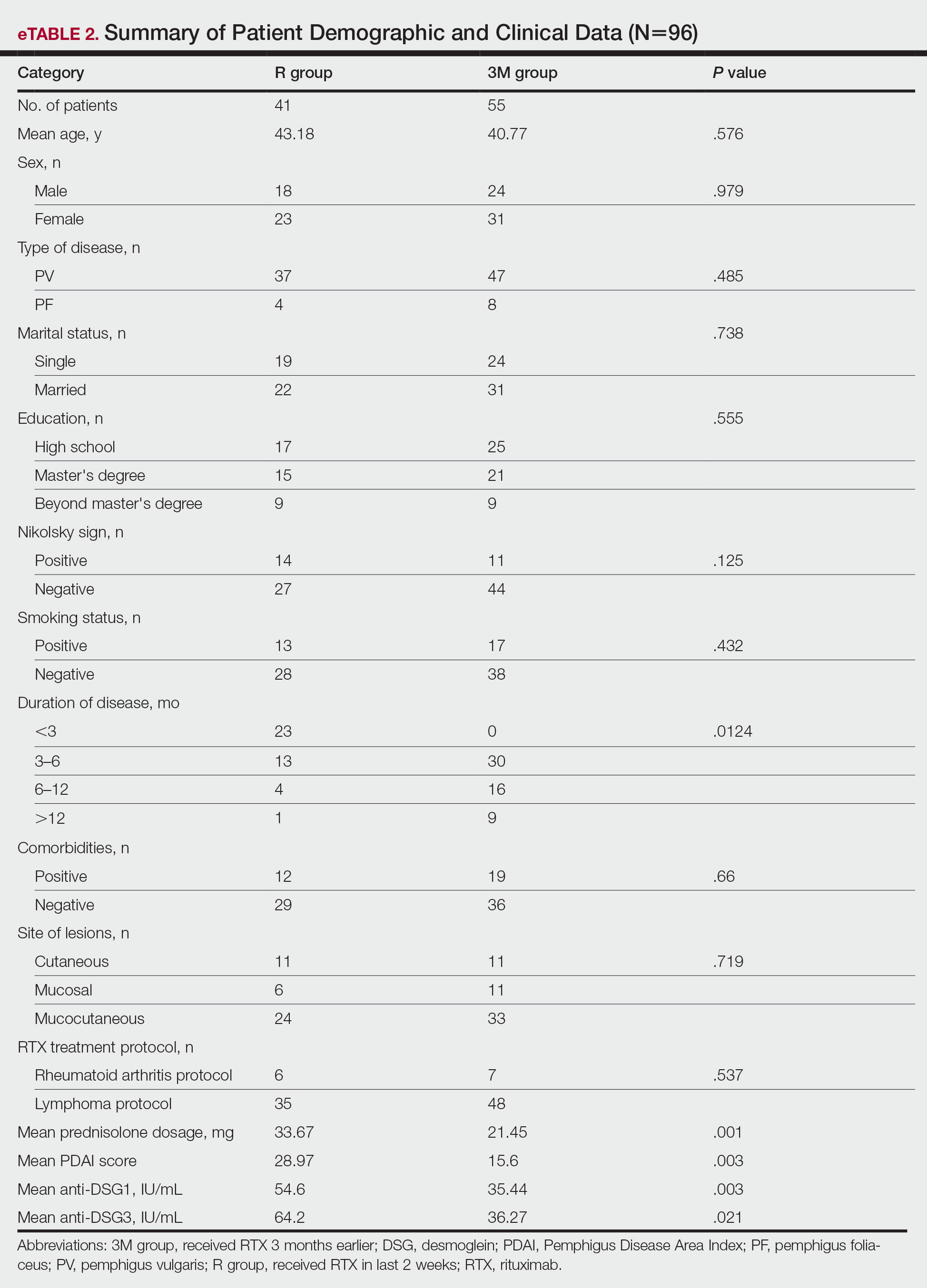

A total of 96 patients were enrolled in this study. The mean (SD) age of participants was 41.42 (15.1) years (range, 18–58 years). Of 96 patients whose data were included, 55 (57.29%) patients had received RTX 3 months earlier (3M group) and 41 (42.71%) received RTX in the last 2 weeks (R group). A summary of study patient characteristics in each group is provided in eTable 2. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of age, sex, type of pemphigus, marital status, education, positive Nikolsky sign, smoking status, existence of comorbidities, site of lesions, and RTX treatment protocol. However, a significant difference was found for duration of disease (P=.0124) and mean prednisolone dosage (P=.001) as well as severity of disease measured by PDAI score (P=.003) and anti-DSG1 (P=.003) and anti-DSG3 (P=.021) values.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

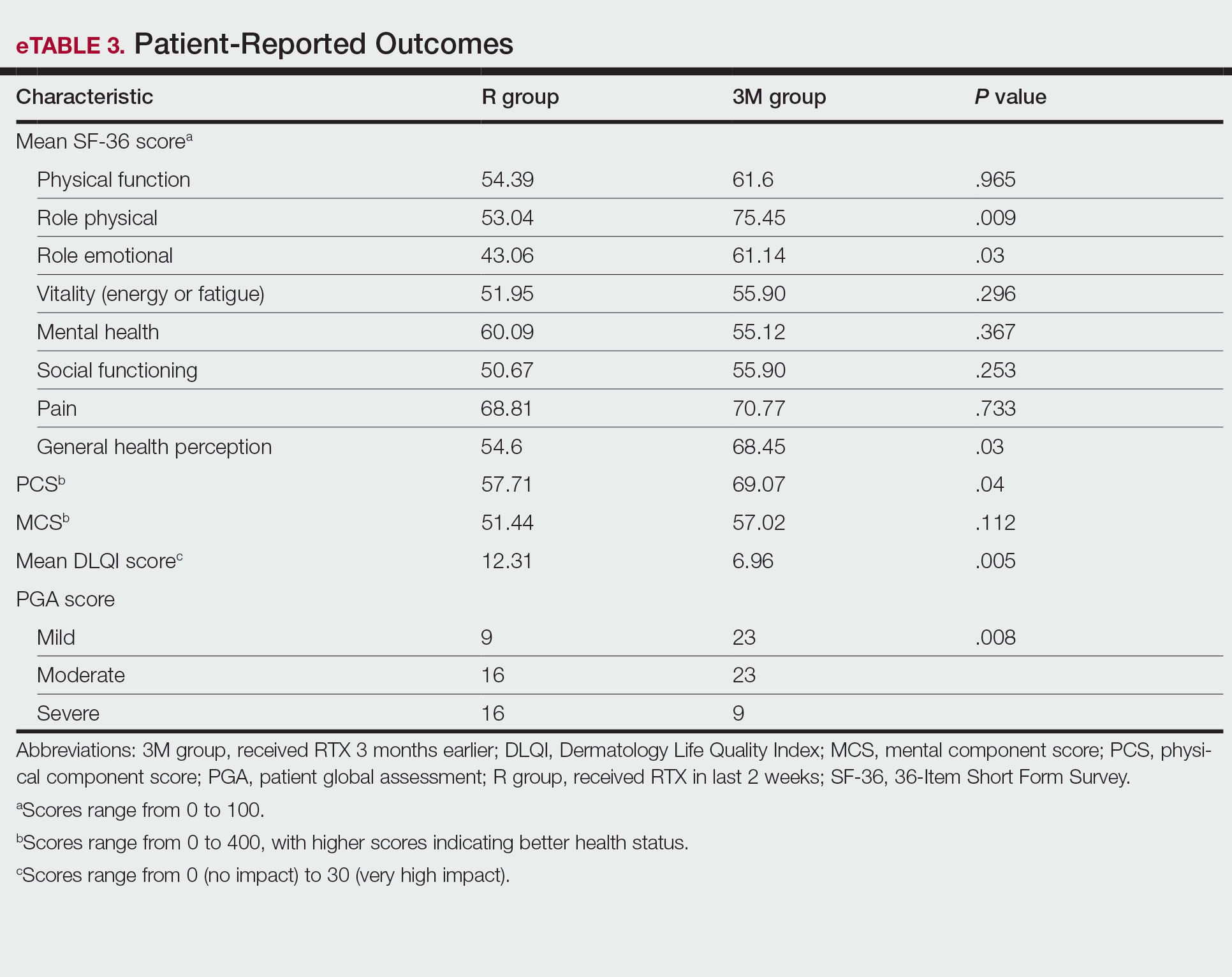

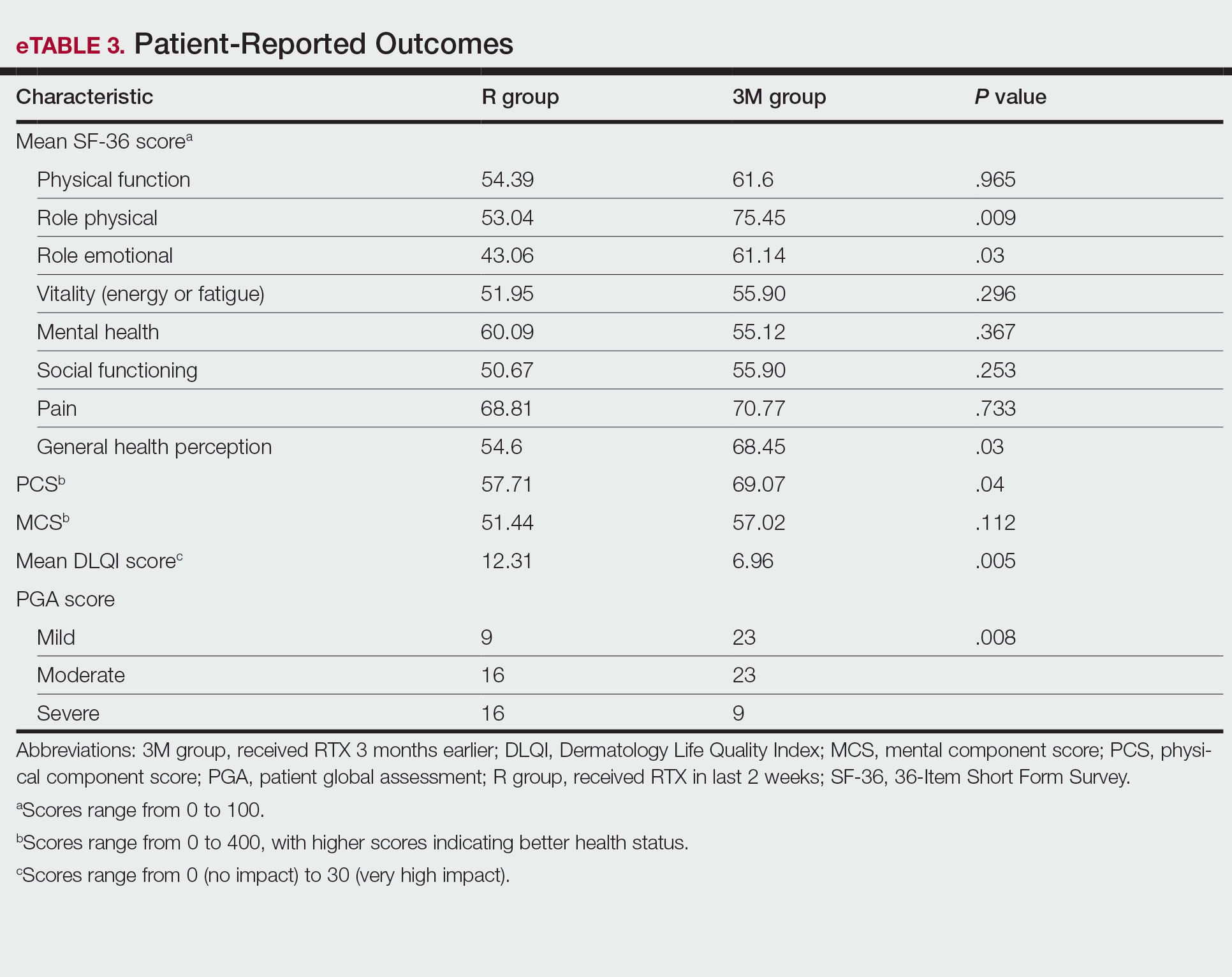

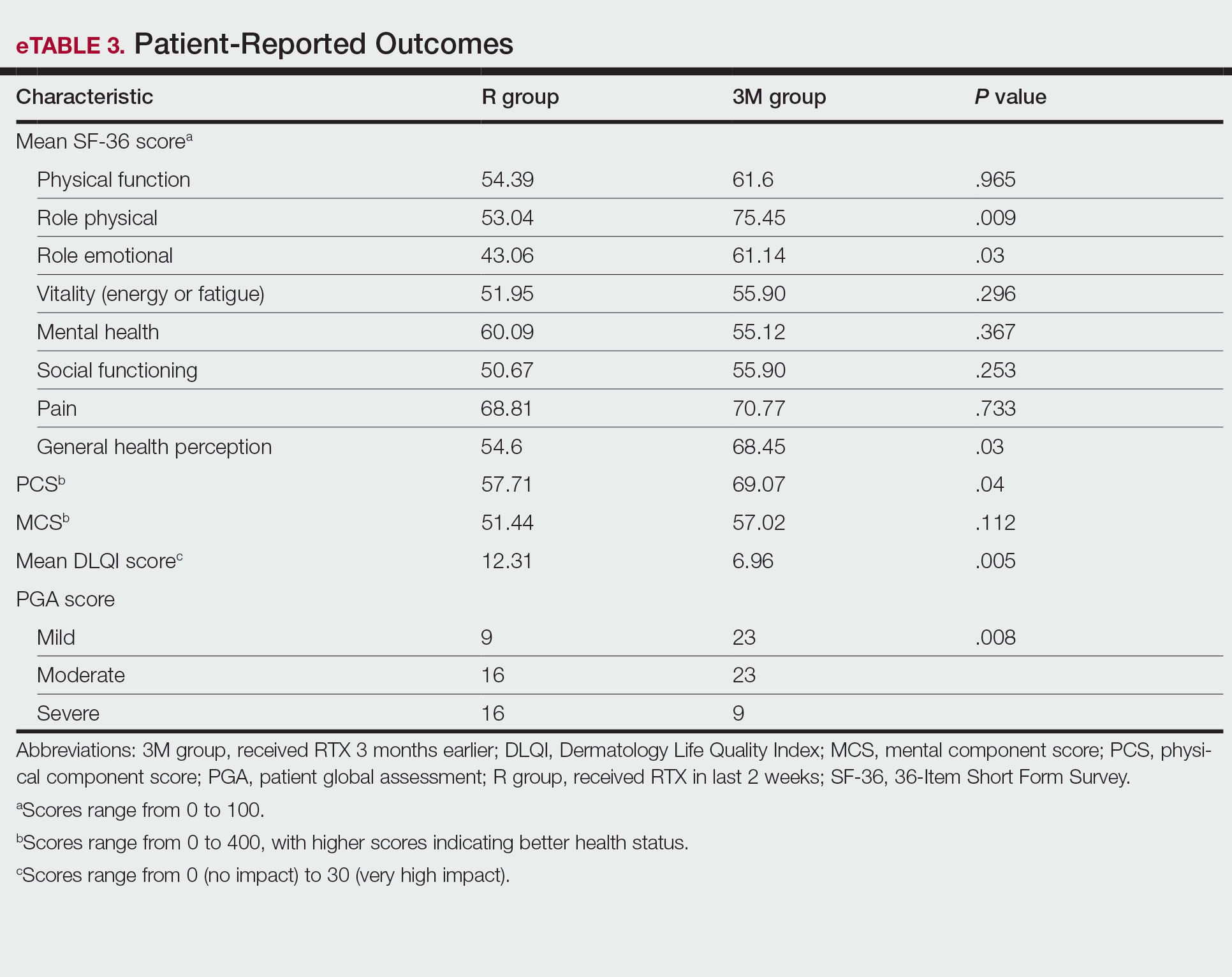

Physical and mental component scores are summarized in eTable 3. Generally, SF-36 scores were improved with RTX treatment in all dimensions except for mental health, though these differences were not statistically significant, with the greatest mean improvement in the role physical index (75.45 in the 3M group vs 53.04 in the R group; P=.009). Mean SF-36 PCS and MCS scores were higher in the 3M group vs the R group, though the difference in MCS score did not reach the level of significance (eTable 3).

Mean DLQI scores in the R and 3M groups were 12.31 and 6.96, respectively, indicating a considerable burden on HRQOL in both groups. However, a statistically significant difference between these values was seen that also was clinically meaningful, indicating a significant improvement of QOL in patients receiving RTX 3 months earlier (P=.005)(eTable 3).

The PGA scores indicated that patients in the 3M group were significantly more likely to report less severe disease vs the R group (P=.008)(eTable 3).

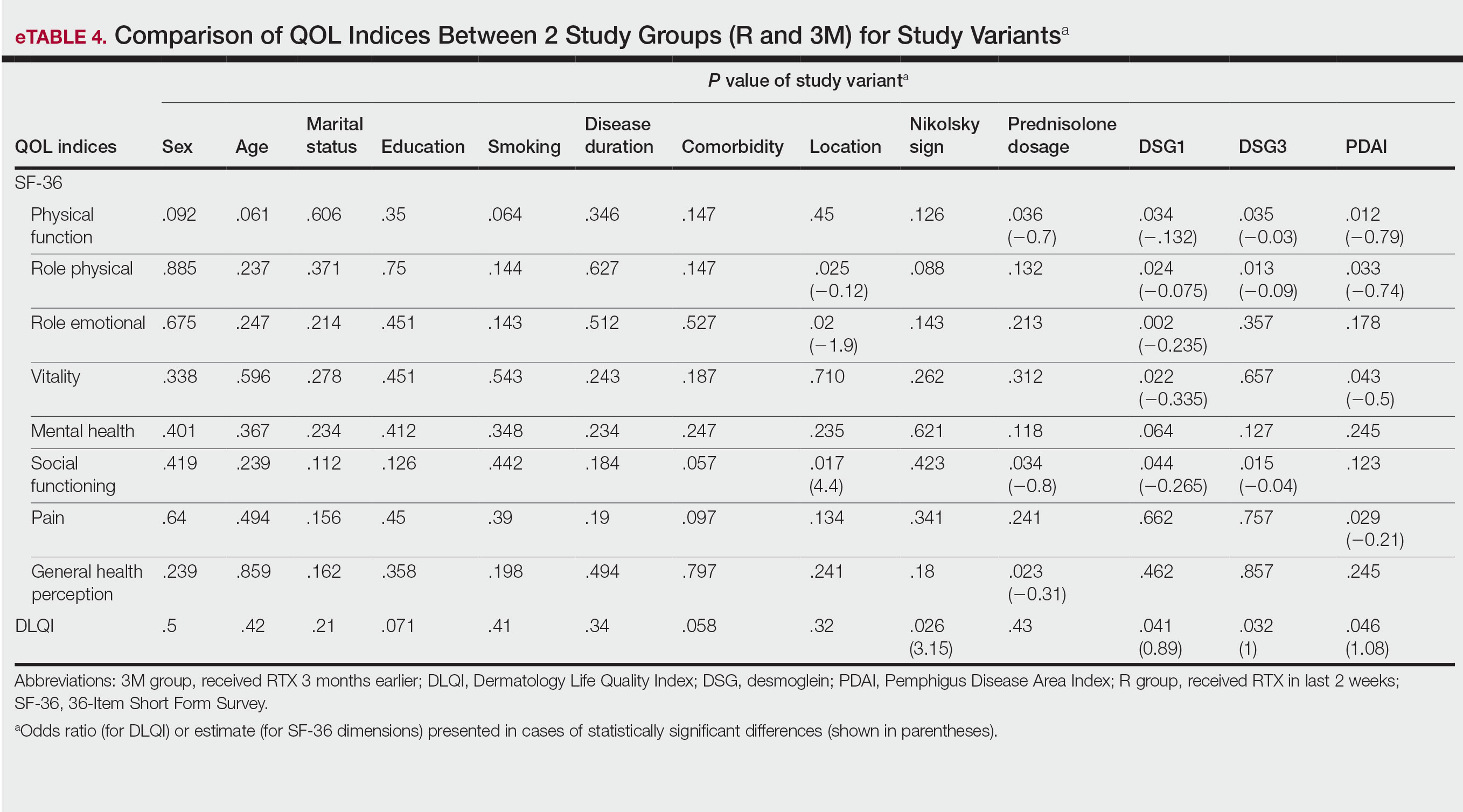

Multivariate Analysis—Effect of the patient characteristics and some disease features on indices of QOL was evaluated using the multiple linear regression model. eTable 4 shows the P values of those analyses.

COMMENT

Pemphigus is a chronic disabling disease with notable QOL impairment due to disease burden as well as the need for long-term use of immunosuppressive agents during the disease course. To study the effect of RTX on QOL of patients with pemphigus, we compared 2 sets of patients. Prior studies have shown that clinically significant effects of RTX take 4 to 12 weeks to appear.19,20 Therefore, we selected patients who received RTX 3 months earlier to measure their HRQOL indices and compare them with patients who had received RTX in the last 2 weeks as a control group to investigate the effect of RTX intrinsically, as this was the focus of this study.

In our study, one of the research tools was the DLQI. Healthy patients typically have an average score of 0.5.21 The mean DLQI score of the patients in R group was 12.31, which was similar to prior analysis8 and reflects a substantial burden of disease comparable to atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.21,22 In patients in the 3M group, the mean DLQI score was lower than the R group (6.96 vs 12.31), indicating a significant (P=.005) and clinically meaningful improvement in QOL of patients due to the dramatic therapeutic effect of RTX. However, this score indicated a moderate effect on HRQOL, even in the context of clinical improvement due to RTX treatment, which may reflect that the short duration of treatment in the 3M group was a limitation of this study. Although the 12-week treatment duration was comparable with other studies19,20 and major differences in objective measures of treatment efficacy were found in PDAI as well as anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values, longer treatment duration may be needed for a more comprehensive assessment of the benefit of RTX on HRQOL indices in patients with pemphigus.

Based on results of the SF-36 questionnaire, PCS and MCS scores were not substantially impaired in the R group considering the fact that a mean score of 50 has been articulated as a normative value for all scales.23 These data demonstrated the importance of using a dermatologic-specific instrument such as the DLQI instead of a general questionnaire to assess QOL in patients with pemphigus. However, better indices were reported with RTX treatment in the 3 SF-36 domains—role physical (P=.009), role emotional (P=.03), and general health perception (P=.03)—with the role physical showing the greatest magnitude of mean change (75.45 in the 3M group vs 53.04 in the R group). Notably, PCS was impaired to a greater extent than MCS in patients in the R group and showed a greater magnitude of improvement after 3 months of treatment. These results could be explained by the fact that MCS can be largely changed in diseases with a direct effect on the central nervous system.23

Our results also revealed that the dose of corticosteroid correlated to HRQOL of patients with pemphigus who recently received RTX therapy. Indeed, it is more likely that patients on lower-dose prednisolone have a higher QOL, especially on physical function and social function dimensions of SF-36. This finding is highly expectable by less severe disease due to RTX treatment and also lower potential dose-dependent adverse effects of long-term steroid therapy.

One of the most striking findings of this study was the correlation of location of lesions to QOL indices. We found that the mucocutaneous phenotype was significantly correlated to greater improvement in role emotional, role physical, and social functioning scores due to RTX treatment compared with cutaneous or mucosal types (P=.02, P=.025, and P=.017, respectively). Although mucosal involvement of the disease can be the most burdensome feature because of its large impact on essential activities such as eating and speaking, cutaneous lesions with unpleasant appearance and undesirable symptoms may have a similar impact on QOL. Therefore, having both mucosal and cutaneous lesions causes a worsened QOL and decreased treatment efficacy vs having only one area involved. This may explain the greater improvement in some QOL indices with RTX treatment.

Limitations—Given the cross-sectional design of this study in which patients were observed at a single time point during their treatment course, it is not possible to establish a clear cause-effect relationship between variables. Moreover, we did not evaluate the impact of RTX or prednisolone adverse effects on QOL. Therefore, further prospective studies with longer treatment durations may help to validate our findings. In addition, MCDs for DLQI and SF-36 in pemphigus need to be determined and validated in future studies.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study demonstrated that patients with pemphigus may benefit from taking RTX, not only in terms of clinical improvement of their disease measured by objective indices such as PDAI and anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values but also in several domains that are important to patients, including physical and mental health status (SF-36), HRQOL (DLQI), and overall disease severity (PGA). Rituximab administration in patients with pemphigus can lead to rapid and significant improvement in HRQOL as well as patient- and physician-assessed measures. Its favorable safety profile along with its impact on patients’ daily lives and mental health makes RTX a suitable treatment option for patients with pemphigus. Moreover, we recommend taking QOL indices into account while evaluating the efficacy of new medications to improve our insight into the patient experience and provide better patient adherence to treatment, which is an important issue for optimal control of chronic disorders.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Ann Rev Pathol. 2016;11:175-197.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, et al. Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17026.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris, result from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435.

- Terrab Z, Benckikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034.

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro, C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269.

- Heelan K, Hitzig SL, Knowles S, et al. Loss of work productivity and quality of life in patients with autoimmune bullous dermatoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:546-554.

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and General Health Questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144.

- Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:2343.

- Mohammad-Javad N, Parvaneh H, Maryam G, et al. Randomized trial of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment versus triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% paste in the treatment of oral pemphigus vulgaris. Iranian J Dermatol. 2012;15:42-46.

- Lunardon L, Tsai KJ, Propert KJ, et al. Adjuvant rituximab therapy of pemphigus: a single-center experience with 31 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1031-1036.

- Colliou N, Picard D, Caillot F, et al. Long-term remissions of severe pemphigus after rituximab therapy are associated with prolonged failure of desmoglein B cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:175ra30.

- Heelan K, Al-Mohammedi F, Smith MJ, et al. Durable remission of pemphigus with a fixed-dose rituximab protocol. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:703-708.

- Joly P, Maho-Vaillant M, Prost-Squarcioni C, et al. First-line rituximab combined with short-term prednisone versus prednisone alone for the treatment of pemphigus (Ritux3): a prospective, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2031-2040

- Aryanian Z, Balighi K, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Rituximab exhibits a better safety profile when used as a first line of treatment for pemphigus vulgaris: a retrospective study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;96:107755.

- Aghai S, Sodaifi M, Jafari P, et al. DLQI scores in vitiligo: reliability and validity of the Persian version. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:8.

- Schünemann HJ, Akl EA, Guyatt GH. Interpreting the results of patient reported outcome measures in clinical trials: the clinician’s perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:62.

- Quality of life questionnaires. Cardiff University website. Accessed December 16, 2022. http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/quality-oflife/dermatology-quality-of-life-index-dlqi/dlqi-instructions-foruse-and-scoring/

- Kanwar AJ, Tsuruta D, Vinay K, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab treatment in Indian pemphigus patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E17-E23.

- Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Cosnes A, et al. First-line treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with a combination of rituximab and high-potency topical corticosteroids. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:200-203.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Aghaei S, Moradi A, Ardekani GS. Impact of psoriasis on quality of life in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:220.

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). 1. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune blistering diseases characterized by the development of painful and flaccid blisters on the skin and/or mucous membranes. Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF) are 2 major subtypes and can be distinguished by the location of blister formation or the specificity of autoantibodies directed against different desmogleins.1,2 Although rare, pemphigus is considered a serious and life-threatening condition with a great impact on quality of life (QOL) due to disease symptoms (eg, painful lesions, physical appearance of skin lesions) as well as treatment complications (eg, adverse drug effects, cost of treatment).3-6 Moreover, the physical and psychological effects can lead to marked functional morbidity and work-related disability during patients’ productive years.7 Therefore, affected individuals usually have a remarkably compromised health-related quality of life (HRQOL).8 Effective treatments may considerably improve the QOL of patients with pemphigus.6

Despite the available treatment options, finding the best regimen for pemphigus remains a challenge. Corticosteroids are assumed to be the main treatment, though they have considerable side effects.9,10 Adjuvant therapies are used to suppress or modulate immune responses, leading to remission with the least possible need for corticosteroids. Finding an optimal steroid-sparing agent has been the aim of research, and biologic agents seem to be the best option.8 Rituximab (RTX), an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has shown great promise in several studies of its clinical efficacy and has become a first-line treatment in new guidelines.11-14 Rituximab treatment has been associated with notable improvement in physician-assessed outcome measures with a favorable safety profile in patients with pemphigus.11-15 However, it is important to assess response to treatment from a patient’s perspective through the use of outcome-assessment measures that encompass patient-reported outcomes to reflect the complete patient experience and establish the overall impact of RTX as well as its likelihood of acceptance by patients with pemphigus.

In our study, we compared clinical outcomes and HRQOL through the use of disease-specific measures as well as comprehensive generic health status measures among patients with PV and PF who received RTX treatment 3 months earlier and those who received RTX in the last 2 weeks. The clinical relevance of the patient-reported outcomes is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a single-center cross-sectional study of 96 patients with pemphigus aged 18 to 65 years of either sex who were willing to participate in this study. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PV or PF who received RTX 3 months earlier or in the last 2 weeks were enrolled in the study. Patients were identified using Dermatry.ir, an archiving software that contains patients’ medical data. Exclusion criteria included lack of sufficient knowledge of the concepts of the questionnaires as well as age younger than 16 years. The study was conducted from October 2019 to April 2020 by the Autoimmune Bullous Disease Research Center at Razi Hospital in Tehran, Iran, which is the main dermatology-specific center and teaching hospital of Iran. The study protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committee.

Patients were categorized into 2 groups: (1) those who received RTX 3 months earlier (3M group); and (2) those who received RTX in the last 2 weeks (R group).

After an explanation of the study to participants, informed written consent was signed by each patient, and their personal data (eg, age, sex, education, marital status, smoking status), as well as clinical data (eg, type of pemphigus, duration of disease, site of onset, prednisolone dosage, presence of Nikolsky sign, anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values, Pemphigus Disease Area Index [PDAI] score, RTX treatment protocol); any known comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or morbid obesity; and any chronic pulmonary, cardiac, endocrinologic, renal, or hepatic condition, were collected and recorded in a predefined Case Record.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

The effect of RTX on QOL in patients with pemphigus was assessed using 2 HRQOL instruments: (1) a general health status indicator, the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36), and (2) a validated, Persian version of a dermatology-specific questionnaire, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The questionnaires were completed by each patient or by an assistant if needed.

The SF-36 is a widely used 36-item questionnaire measuring functional health and well-being across 8 domains—mental health, pain, physical function, role emotional, role physical, social functioning, vitality, and general health perception—with scores for each ranging from 0 to 100. The physical component scores (PCSs) and mental component scores (MCSs) were derived from these 8 subscales, each ranging from 0 to 400, with higher scores indicating better health status.6

The DLQI, one of the most frequently used QOL measures in dermatology, contains 10 questions, each referring to the prior week and classified in the following 6 subscales: symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, personal relationships, work and school, and treatment.16 The total score ranges from 0 (no impact) to 30 (very high impact), with a higher score indicating a lower QOL (eTable 1). The minimal clinically important difference (MCD) for the DLQI was considered to be 2- to 5-point changes in prior studies.17,18 In this study, we used an MCD of a 5-point change or more between study groups.

Moreover, the patient general assessment (PGA) of disease severity was identified using a 3-point scale (1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 23. P≤.05 was considered significant. Mean and SD were calculated for descriptive data. The t test, Fisher exact test, analysis of variance, multiple regression analysis, and logistic regression analysis were used to identify the relationship between variables.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 96 patients were enrolled in this study. The mean (SD) age of participants was 41.42 (15.1) years (range, 18–58 years). Of 96 patients whose data were included, 55 (57.29%) patients had received RTX 3 months earlier (3M group) and 41 (42.71%) received RTX in the last 2 weeks (R group). A summary of study patient characteristics in each group is provided in eTable 2. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of age, sex, type of pemphigus, marital status, education, positive Nikolsky sign, smoking status, existence of comorbidities, site of lesions, and RTX treatment protocol. However, a significant difference was found for duration of disease (P=.0124) and mean prednisolone dosage (P=.001) as well as severity of disease measured by PDAI score (P=.003) and anti-DSG1 (P=.003) and anti-DSG3 (P=.021) values.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Physical and mental component scores are summarized in eTable 3. Generally, SF-36 scores were improved with RTX treatment in all dimensions except for mental health, though these differences were not statistically significant, with the greatest mean improvement in the role physical index (75.45 in the 3M group vs 53.04 in the R group; P=.009). Mean SF-36 PCS and MCS scores were higher in the 3M group vs the R group, though the difference in MCS score did not reach the level of significance (eTable 3).

Mean DLQI scores in the R and 3M groups were 12.31 and 6.96, respectively, indicating a considerable burden on HRQOL in both groups. However, a statistically significant difference between these values was seen that also was clinically meaningful, indicating a significant improvement of QOL in patients receiving RTX 3 months earlier (P=.005)(eTable 3).

The PGA scores indicated that patients in the 3M group were significantly more likely to report less severe disease vs the R group (P=.008)(eTable 3).

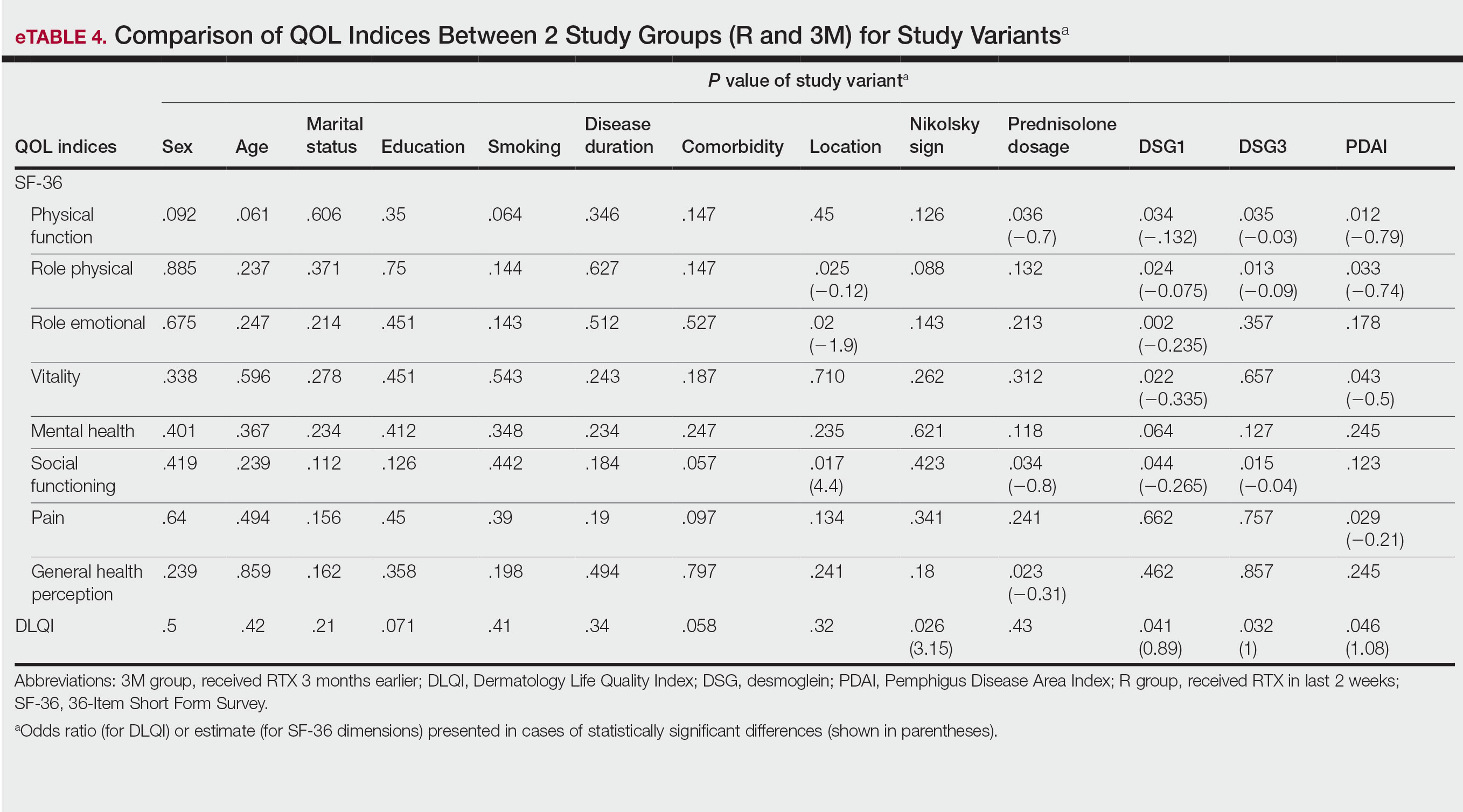

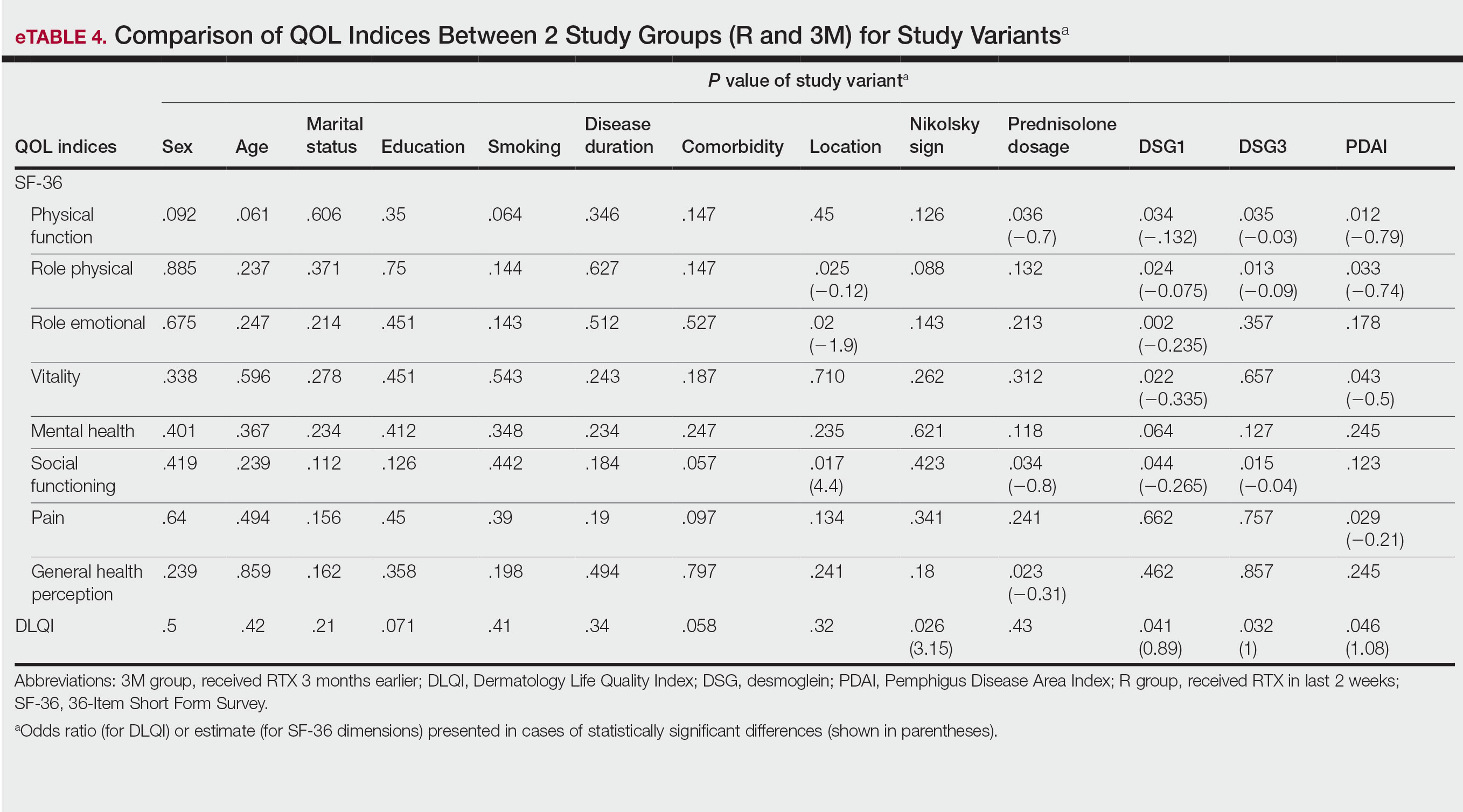

Multivariate Analysis—Effect of the patient characteristics and some disease features on indices of QOL was evaluated using the multiple linear regression model. eTable 4 shows the P values of those analyses.

COMMENT

Pemphigus is a chronic disabling disease with notable QOL impairment due to disease burden as well as the need for long-term use of immunosuppressive agents during the disease course. To study the effect of RTX on QOL of patients with pemphigus, we compared 2 sets of patients. Prior studies have shown that clinically significant effects of RTX take 4 to 12 weeks to appear.19,20 Therefore, we selected patients who received RTX 3 months earlier to measure their HRQOL indices and compare them with patients who had received RTX in the last 2 weeks as a control group to investigate the effect of RTX intrinsically, as this was the focus of this study.

In our study, one of the research tools was the DLQI. Healthy patients typically have an average score of 0.5.21 The mean DLQI score of the patients in R group was 12.31, which was similar to prior analysis8 and reflects a substantial burden of disease comparable to atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.21,22 In patients in the 3M group, the mean DLQI score was lower than the R group (6.96 vs 12.31), indicating a significant (P=.005) and clinically meaningful improvement in QOL of patients due to the dramatic therapeutic effect of RTX. However, this score indicated a moderate effect on HRQOL, even in the context of clinical improvement due to RTX treatment, which may reflect that the short duration of treatment in the 3M group was a limitation of this study. Although the 12-week treatment duration was comparable with other studies19,20 and major differences in objective measures of treatment efficacy were found in PDAI as well as anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values, longer treatment duration may be needed for a more comprehensive assessment of the benefit of RTX on HRQOL indices in patients with pemphigus.

Based on results of the SF-36 questionnaire, PCS and MCS scores were not substantially impaired in the R group considering the fact that a mean score of 50 has been articulated as a normative value for all scales.23 These data demonstrated the importance of using a dermatologic-specific instrument such as the DLQI instead of a general questionnaire to assess QOL in patients with pemphigus. However, better indices were reported with RTX treatment in the 3 SF-36 domains—role physical (P=.009), role emotional (P=.03), and general health perception (P=.03)—with the role physical showing the greatest magnitude of mean change (75.45 in the 3M group vs 53.04 in the R group). Notably, PCS was impaired to a greater extent than MCS in patients in the R group and showed a greater magnitude of improvement after 3 months of treatment. These results could be explained by the fact that MCS can be largely changed in diseases with a direct effect on the central nervous system.23

Our results also revealed that the dose of corticosteroid correlated to HRQOL of patients with pemphigus who recently received RTX therapy. Indeed, it is more likely that patients on lower-dose prednisolone have a higher QOL, especially on physical function and social function dimensions of SF-36. This finding is highly expectable by less severe disease due to RTX treatment and also lower potential dose-dependent adverse effects of long-term steroid therapy.

One of the most striking findings of this study was the correlation of location of lesions to QOL indices. We found that the mucocutaneous phenotype was significantly correlated to greater improvement in role emotional, role physical, and social functioning scores due to RTX treatment compared with cutaneous or mucosal types (P=.02, P=.025, and P=.017, respectively). Although mucosal involvement of the disease can be the most burdensome feature because of its large impact on essential activities such as eating and speaking, cutaneous lesions with unpleasant appearance and undesirable symptoms may have a similar impact on QOL. Therefore, having both mucosal and cutaneous lesions causes a worsened QOL and decreased treatment efficacy vs having only one area involved. This may explain the greater improvement in some QOL indices with RTX treatment.

Limitations—Given the cross-sectional design of this study in which patients were observed at a single time point during their treatment course, it is not possible to establish a clear cause-effect relationship between variables. Moreover, we did not evaluate the impact of RTX or prednisolone adverse effects on QOL. Therefore, further prospective studies with longer treatment durations may help to validate our findings. In addition, MCDs for DLQI and SF-36 in pemphigus need to be determined and validated in future studies.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study demonstrated that patients with pemphigus may benefit from taking RTX, not only in terms of clinical improvement of their disease measured by objective indices such as PDAI and anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values but also in several domains that are important to patients, including physical and mental health status (SF-36), HRQOL (DLQI), and overall disease severity (PGA). Rituximab administration in patients with pemphigus can lead to rapid and significant improvement in HRQOL as well as patient- and physician-assessed measures. Its favorable safety profile along with its impact on patients’ daily lives and mental health makes RTX a suitable treatment option for patients with pemphigus. Moreover, we recommend taking QOL indices into account while evaluating the efficacy of new medications to improve our insight into the patient experience and provide better patient adherence to treatment, which is an important issue for optimal control of chronic disorders.

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune blistering diseases characterized by the development of painful and flaccid blisters on the skin and/or mucous membranes. Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) and pemphigus foliaceus (PF) are 2 major subtypes and can be distinguished by the location of blister formation or the specificity of autoantibodies directed against different desmogleins.1,2 Although rare, pemphigus is considered a serious and life-threatening condition with a great impact on quality of life (QOL) due to disease symptoms (eg, painful lesions, physical appearance of skin lesions) as well as treatment complications (eg, adverse drug effects, cost of treatment).3-6 Moreover, the physical and psychological effects can lead to marked functional morbidity and work-related disability during patients’ productive years.7 Therefore, affected individuals usually have a remarkably compromised health-related quality of life (HRQOL).8 Effective treatments may considerably improve the QOL of patients with pemphigus.6

Despite the available treatment options, finding the best regimen for pemphigus remains a challenge. Corticosteroids are assumed to be the main treatment, though they have considerable side effects.9,10 Adjuvant therapies are used to suppress or modulate immune responses, leading to remission with the least possible need for corticosteroids. Finding an optimal steroid-sparing agent has been the aim of research, and biologic agents seem to be the best option.8 Rituximab (RTX), an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has shown great promise in several studies of its clinical efficacy and has become a first-line treatment in new guidelines.11-14 Rituximab treatment has been associated with notable improvement in physician-assessed outcome measures with a favorable safety profile in patients with pemphigus.11-15 However, it is important to assess response to treatment from a patient’s perspective through the use of outcome-assessment measures that encompass patient-reported outcomes to reflect the complete patient experience and establish the overall impact of RTX as well as its likelihood of acceptance by patients with pemphigus.

In our study, we compared clinical outcomes and HRQOL through the use of disease-specific measures as well as comprehensive generic health status measures among patients with PV and PF who received RTX treatment 3 months earlier and those who received RTX in the last 2 weeks. The clinical relevance of the patient-reported outcomes is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a single-center cross-sectional study of 96 patients with pemphigus aged 18 to 65 years of either sex who were willing to participate in this study. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PV or PF who received RTX 3 months earlier or in the last 2 weeks were enrolled in the study. Patients were identified using Dermatry.ir, an archiving software that contains patients’ medical data. Exclusion criteria included lack of sufficient knowledge of the concepts of the questionnaires as well as age younger than 16 years. The study was conducted from October 2019 to April 2020 by the Autoimmune Bullous Disease Research Center at Razi Hospital in Tehran, Iran, which is the main dermatology-specific center and teaching hospital of Iran. The study protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committee.

Patients were categorized into 2 groups: (1) those who received RTX 3 months earlier (3M group); and (2) those who received RTX in the last 2 weeks (R group).

After an explanation of the study to participants, informed written consent was signed by each patient, and their personal data (eg, age, sex, education, marital status, smoking status), as well as clinical data (eg, type of pemphigus, duration of disease, site of onset, prednisolone dosage, presence of Nikolsky sign, anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values, Pemphigus Disease Area Index [PDAI] score, RTX treatment protocol); any known comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or morbid obesity; and any chronic pulmonary, cardiac, endocrinologic, renal, or hepatic condition, were collected and recorded in a predefined Case Record.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

The effect of RTX on QOL in patients with pemphigus was assessed using 2 HRQOL instruments: (1) a general health status indicator, the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36), and (2) a validated, Persian version of a dermatology-specific questionnaire, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The questionnaires were completed by each patient or by an assistant if needed.

The SF-36 is a widely used 36-item questionnaire measuring functional health and well-being across 8 domains—mental health, pain, physical function, role emotional, role physical, social functioning, vitality, and general health perception—with scores for each ranging from 0 to 100. The physical component scores (PCSs) and mental component scores (MCSs) were derived from these 8 subscales, each ranging from 0 to 400, with higher scores indicating better health status.6

The DLQI, one of the most frequently used QOL measures in dermatology, contains 10 questions, each referring to the prior week and classified in the following 6 subscales: symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, personal relationships, work and school, and treatment.16 The total score ranges from 0 (no impact) to 30 (very high impact), with a higher score indicating a lower QOL (eTable 1). The minimal clinically important difference (MCD) for the DLQI was considered to be 2- to 5-point changes in prior studies.17,18 In this study, we used an MCD of a 5-point change or more between study groups.

Moreover, the patient general assessment (PGA) of disease severity was identified using a 3-point scale (1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 23. P≤.05 was considered significant. Mean and SD were calculated for descriptive data. The t test, Fisher exact test, analysis of variance, multiple regression analysis, and logistic regression analysis were used to identify the relationship between variables.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 96 patients were enrolled in this study. The mean (SD) age of participants was 41.42 (15.1) years (range, 18–58 years). Of 96 patients whose data were included, 55 (57.29%) patients had received RTX 3 months earlier (3M group) and 41 (42.71%) received RTX in the last 2 weeks (R group). A summary of study patient characteristics in each group is provided in eTable 2. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of age, sex, type of pemphigus, marital status, education, positive Nikolsky sign, smoking status, existence of comorbidities, site of lesions, and RTX treatment protocol. However, a significant difference was found for duration of disease (P=.0124) and mean prednisolone dosage (P=.001) as well as severity of disease measured by PDAI score (P=.003) and anti-DSG1 (P=.003) and anti-DSG3 (P=.021) values.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Physical and mental component scores are summarized in eTable 3. Generally, SF-36 scores were improved with RTX treatment in all dimensions except for mental health, though these differences were not statistically significant, with the greatest mean improvement in the role physical index (75.45 in the 3M group vs 53.04 in the R group; P=.009). Mean SF-36 PCS and MCS scores were higher in the 3M group vs the R group, though the difference in MCS score did not reach the level of significance (eTable 3).

Mean DLQI scores in the R and 3M groups were 12.31 and 6.96, respectively, indicating a considerable burden on HRQOL in both groups. However, a statistically significant difference between these values was seen that also was clinically meaningful, indicating a significant improvement of QOL in patients receiving RTX 3 months earlier (P=.005)(eTable 3).

The PGA scores indicated that patients in the 3M group were significantly more likely to report less severe disease vs the R group (P=.008)(eTable 3).

Multivariate Analysis—Effect of the patient characteristics and some disease features on indices of QOL was evaluated using the multiple linear regression model. eTable 4 shows the P values of those analyses.

COMMENT

Pemphigus is a chronic disabling disease with notable QOL impairment due to disease burden as well as the need for long-term use of immunosuppressive agents during the disease course. To study the effect of RTX on QOL of patients with pemphigus, we compared 2 sets of patients. Prior studies have shown that clinically significant effects of RTX take 4 to 12 weeks to appear.19,20 Therefore, we selected patients who received RTX 3 months earlier to measure their HRQOL indices and compare them with patients who had received RTX in the last 2 weeks as a control group to investigate the effect of RTX intrinsically, as this was the focus of this study.

In our study, one of the research tools was the DLQI. Healthy patients typically have an average score of 0.5.21 The mean DLQI score of the patients in R group was 12.31, which was similar to prior analysis8 and reflects a substantial burden of disease comparable to atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.21,22 In patients in the 3M group, the mean DLQI score was lower than the R group (6.96 vs 12.31), indicating a significant (P=.005) and clinically meaningful improvement in QOL of patients due to the dramatic therapeutic effect of RTX. However, this score indicated a moderate effect on HRQOL, even in the context of clinical improvement due to RTX treatment, which may reflect that the short duration of treatment in the 3M group was a limitation of this study. Although the 12-week treatment duration was comparable with other studies19,20 and major differences in objective measures of treatment efficacy were found in PDAI as well as anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values, longer treatment duration may be needed for a more comprehensive assessment of the benefit of RTX on HRQOL indices in patients with pemphigus.

Based on results of the SF-36 questionnaire, PCS and MCS scores were not substantially impaired in the R group considering the fact that a mean score of 50 has been articulated as a normative value for all scales.23 These data demonstrated the importance of using a dermatologic-specific instrument such as the DLQI instead of a general questionnaire to assess QOL in patients with pemphigus. However, better indices were reported with RTX treatment in the 3 SF-36 domains—role physical (P=.009), role emotional (P=.03), and general health perception (P=.03)—with the role physical showing the greatest magnitude of mean change (75.45 in the 3M group vs 53.04 in the R group). Notably, PCS was impaired to a greater extent than MCS in patients in the R group and showed a greater magnitude of improvement after 3 months of treatment. These results could be explained by the fact that MCS can be largely changed in diseases with a direct effect on the central nervous system.23

Our results also revealed that the dose of corticosteroid correlated to HRQOL of patients with pemphigus who recently received RTX therapy. Indeed, it is more likely that patients on lower-dose prednisolone have a higher QOL, especially on physical function and social function dimensions of SF-36. This finding is highly expectable by less severe disease due to RTX treatment and also lower potential dose-dependent adverse effects of long-term steroid therapy.

One of the most striking findings of this study was the correlation of location of lesions to QOL indices. We found that the mucocutaneous phenotype was significantly correlated to greater improvement in role emotional, role physical, and social functioning scores due to RTX treatment compared with cutaneous or mucosal types (P=.02, P=.025, and P=.017, respectively). Although mucosal involvement of the disease can be the most burdensome feature because of its large impact on essential activities such as eating and speaking, cutaneous lesions with unpleasant appearance and undesirable symptoms may have a similar impact on QOL. Therefore, having both mucosal and cutaneous lesions causes a worsened QOL and decreased treatment efficacy vs having only one area involved. This may explain the greater improvement in some QOL indices with RTX treatment.

Limitations—Given the cross-sectional design of this study in which patients were observed at a single time point during their treatment course, it is not possible to establish a clear cause-effect relationship between variables. Moreover, we did not evaluate the impact of RTX or prednisolone adverse effects on QOL. Therefore, further prospective studies with longer treatment durations may help to validate our findings. In addition, MCDs for DLQI and SF-36 in pemphigus need to be determined and validated in future studies.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study demonstrated that patients with pemphigus may benefit from taking RTX, not only in terms of clinical improvement of their disease measured by objective indices such as PDAI and anti-DSG1 and anti-DSG3 values but also in several domains that are important to patients, including physical and mental health status (SF-36), HRQOL (DLQI), and overall disease severity (PGA). Rituximab administration in patients with pemphigus can lead to rapid and significant improvement in HRQOL as well as patient- and physician-assessed measures. Its favorable safety profile along with its impact on patients’ daily lives and mental health makes RTX a suitable treatment option for patients with pemphigus. Moreover, we recommend taking QOL indices into account while evaluating the efficacy of new medications to improve our insight into the patient experience and provide better patient adherence to treatment, which is an important issue for optimal control of chronic disorders.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Ann Rev Pathol. 2016;11:175-197.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, et al. Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17026.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris, result from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435.

- Terrab Z, Benckikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034.

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro, C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269.

- Heelan K, Hitzig SL, Knowles S, et al. Loss of work productivity and quality of life in patients with autoimmune bullous dermatoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:546-554.

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and General Health Questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144.

- Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:2343.

- Mohammad-Javad N, Parvaneh H, Maryam G, et al. Randomized trial of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment versus triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% paste in the treatment of oral pemphigus vulgaris. Iranian J Dermatol. 2012;15:42-46.

- Lunardon L, Tsai KJ, Propert KJ, et al. Adjuvant rituximab therapy of pemphigus: a single-center experience with 31 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1031-1036.

- Colliou N, Picard D, Caillot F, et al. Long-term remissions of severe pemphigus after rituximab therapy are associated with prolonged failure of desmoglein B cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:175ra30.

- Heelan K, Al-Mohammedi F, Smith MJ, et al. Durable remission of pemphigus with a fixed-dose rituximab protocol. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:703-708.

- Joly P, Maho-Vaillant M, Prost-Squarcioni C, et al. First-line rituximab combined with short-term prednisone versus prednisone alone for the treatment of pemphigus (Ritux3): a prospective, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2031-2040

- Aryanian Z, Balighi K, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Rituximab exhibits a better safety profile when used as a first line of treatment for pemphigus vulgaris: a retrospective study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;96:107755.

- Aghai S, Sodaifi M, Jafari P, et al. DLQI scores in vitiligo: reliability and validity of the Persian version. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:8.

- Schünemann HJ, Akl EA, Guyatt GH. Interpreting the results of patient reported outcome measures in clinical trials: the clinician’s perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:62.

- Quality of life questionnaires. Cardiff University website. Accessed December 16, 2022. http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/quality-oflife/dermatology-quality-of-life-index-dlqi/dlqi-instructions-foruse-and-scoring/

- Kanwar AJ, Tsuruta D, Vinay K, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab treatment in Indian pemphigus patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E17-E23.

- Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Cosnes A, et al. First-line treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with a combination of rituximab and high-potency topical corticosteroids. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:200-203.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Aghaei S, Moradi A, Ardekani GS. Impact of psoriasis on quality of life in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:220.

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). 1. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Ann Rev Pathol. 2016;11:175-197.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, et al. Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17026.

- Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris, result from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431-435.

- Terrab Z, Benckikhi H, Maaroufi A, et al. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-328.

- Tabolli S, Mozzetta A, Antinone V, et al. The health impact of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1029-1034.

- Paradisi A, Sampogna F, Di Pietro, C, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in patients with pemphigus using a minimum set of evaluation tools. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:261-269.

- Heelan K, Hitzig SL, Knowles S, et al. Loss of work productivity and quality of life in patients with autoimmune bullous dermatoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:546-554.

- Ghodsi SZ, Chams-Davatchi C, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and General Health Questionnaires. J Dermatol. 2012;39:141-144.

- Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:2343.

- Mohammad-Javad N, Parvaneh H, Maryam G, et al. Randomized trial of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment versus triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% paste in the treatment of oral pemphigus vulgaris. Iranian J Dermatol. 2012;15:42-46.

- Lunardon L, Tsai KJ, Propert KJ, et al. Adjuvant rituximab therapy of pemphigus: a single-center experience with 31 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1031-1036.

- Colliou N, Picard D, Caillot F, et al. Long-term remissions of severe pemphigus after rituximab therapy are associated with prolonged failure of desmoglein B cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:175ra30.

- Heelan K, Al-Mohammedi F, Smith MJ, et al. Durable remission of pemphigus with a fixed-dose rituximab protocol. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:703-708.

- Joly P, Maho-Vaillant M, Prost-Squarcioni C, et al. First-line rituximab combined with short-term prednisone versus prednisone alone for the treatment of pemphigus (Ritux3): a prospective, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2031-2040

- Aryanian Z, Balighi K, Daneshpazhooh M, et al. Rituximab exhibits a better safety profile when used as a first line of treatment for pemphigus vulgaris: a retrospective study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;96:107755.

- Aghai S, Sodaifi M, Jafari P, et al. DLQI scores in vitiligo: reliability and validity of the Persian version. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:8.

- Schünemann HJ, Akl EA, Guyatt GH. Interpreting the results of patient reported outcome measures in clinical trials: the clinician’s perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:62.

- Quality of life questionnaires. Cardiff University website. Accessed December 16, 2022. http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/quality-oflife/dermatology-quality-of-life-index-dlqi/dlqi-instructions-foruse-and-scoring/

- Kanwar AJ, Tsuruta D, Vinay K, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab treatment in Indian pemphigus patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E17-E23.

- Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Cosnes A, et al. First-line treatment of pemphigus vulgaris with a combination of rituximab and high-potency topical corticosteroids. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:200-203.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Aghaei S, Moradi A, Ardekani GS. Impact of psoriasis on quality of life in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:220.

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). 1. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease that can negatively affect patients’ lives.

- Assessing the impact of treatment from a patient’s perspective using outcome assessment measures is important and relevant in trials of new pemphigus treatments including rituximab.

- Rituximab administration in pemphigus patients led to rapid and notable improvement in health-related quality of life and patient-assessed measures.

Cutaneous Manifestations in Hereditary Alpha Tryptasemia

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT

A case series reported by Lyons et al1 in 2014 detailed persistent elevated basal serum tryptase levels in 9 families with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance. In this cohort, 31 of 33 (94%) affected individuals had a history of atopic dermatitis (AD), and 26 of 33 (79%) affected individuals reported symptoms consistent with mast cell degranulation, including urticaria; flushing; and/or crampy abdominal pain unprovoked or triggered by heat, exercise, vibration, stress, certain foods, or minor physical stimulation.1 A later report by Lyons et al2 in 2016 identified the TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequence copy number increase as the causative entity for HaT by examining a group of 96 patients from 35 families with frequent recurrent cutaneous flushing and pruritus, sometimes associated with urticaria and sleep disruption. Flushing and pruritus were found in 45% (33/73) of those with a TPSAB1 duplication and 80% (12/15) of those with a triplication (P=.022), suggesting a gene dose effect regarding α-tryptase encoding sequence copy number and these symptoms.2

A 2019 study further explored the clinical finding of urticaria in patients with HaT by specifically examining if vibration-induced urticaria was affected by TPSAB1 gene dosage.8 A cohort of 56 volunteers—35 healthy and 21 with HaT—underwent tryptase genotyping and cutaneous vibratory challenge. The presence of TPSAB1 was significantly correlated with induction of vibration-induced urticaria (P<.01), as the severity and prevalence of the urticarial response increased along with α- and β-tryptase gene ratios.8

Urticaria and angioedema also were seen in 51% (36/70) of patients in a cohort of HaT patients in the United Kingdom, in which 41% (29/70) also had skin flushing. In contrast to prior studies, these manifestations were not more common in patients with gene triplications or quintuplications than those with duplications.7 In another recent retrospective evaluation conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts)(N=101), 80% of patients aged 4 to 85 years with confirmed diagnoses of HaT had skin manifestations such as urticaria, flushing, and pruritus.4

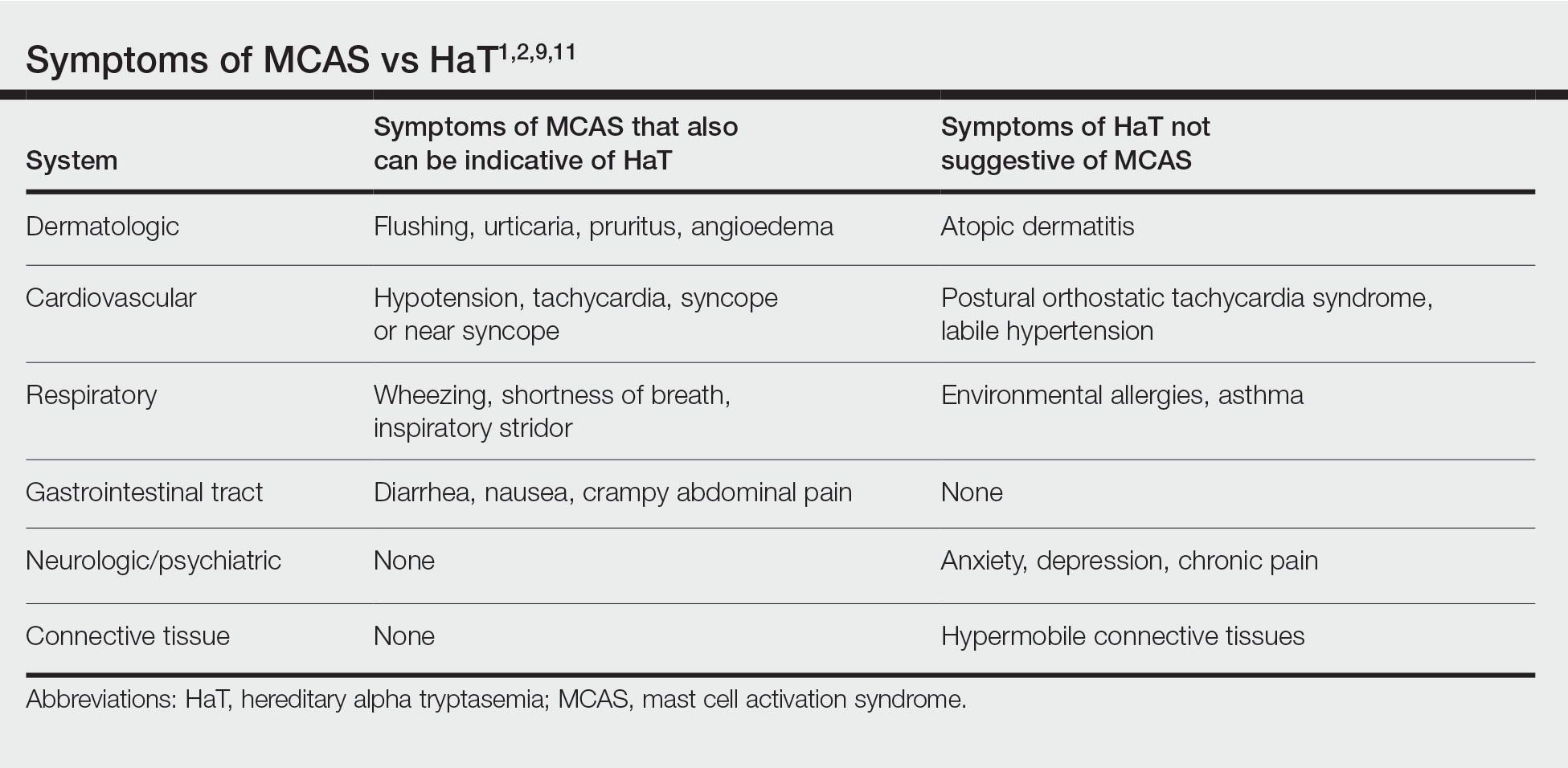

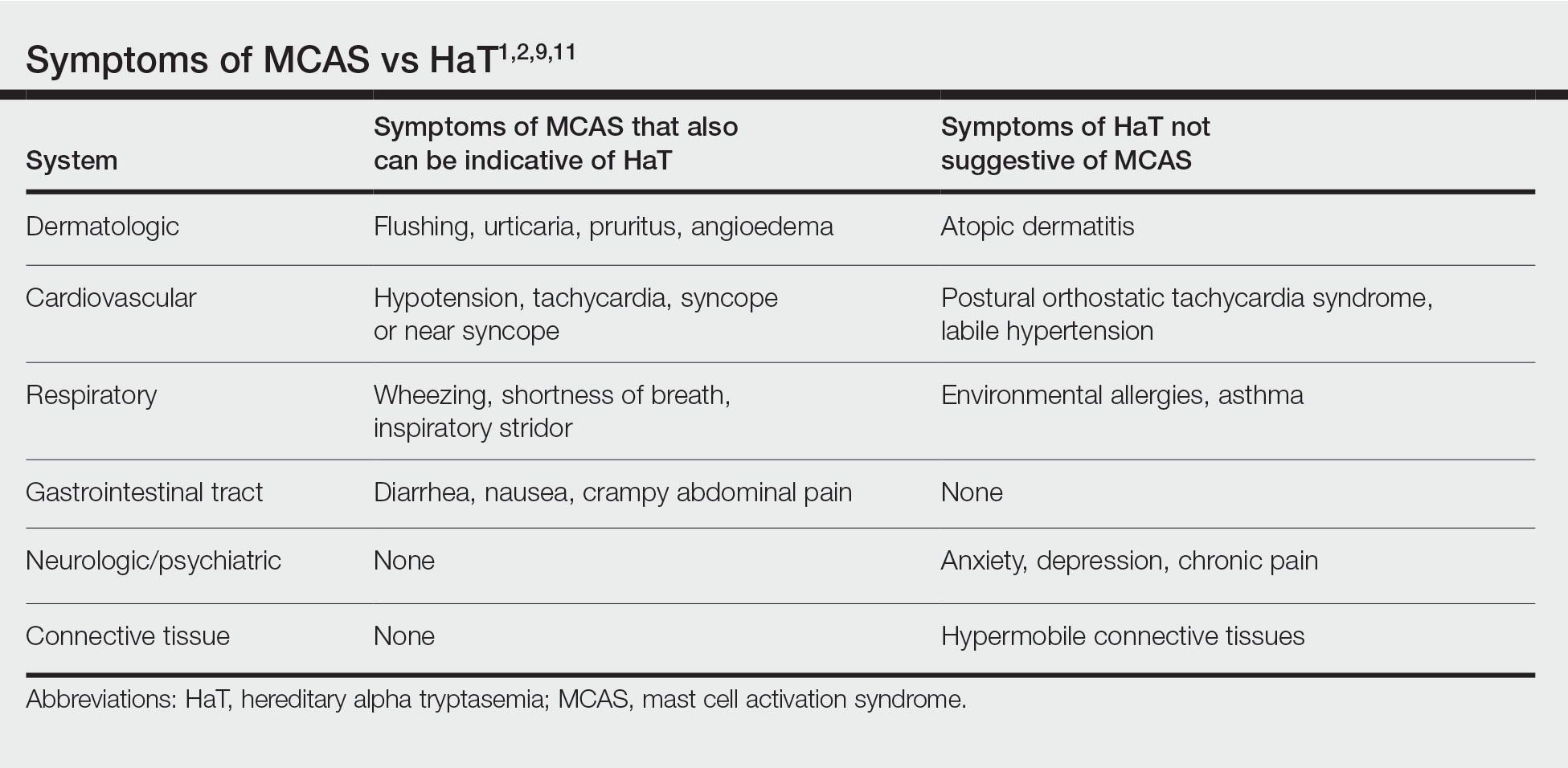

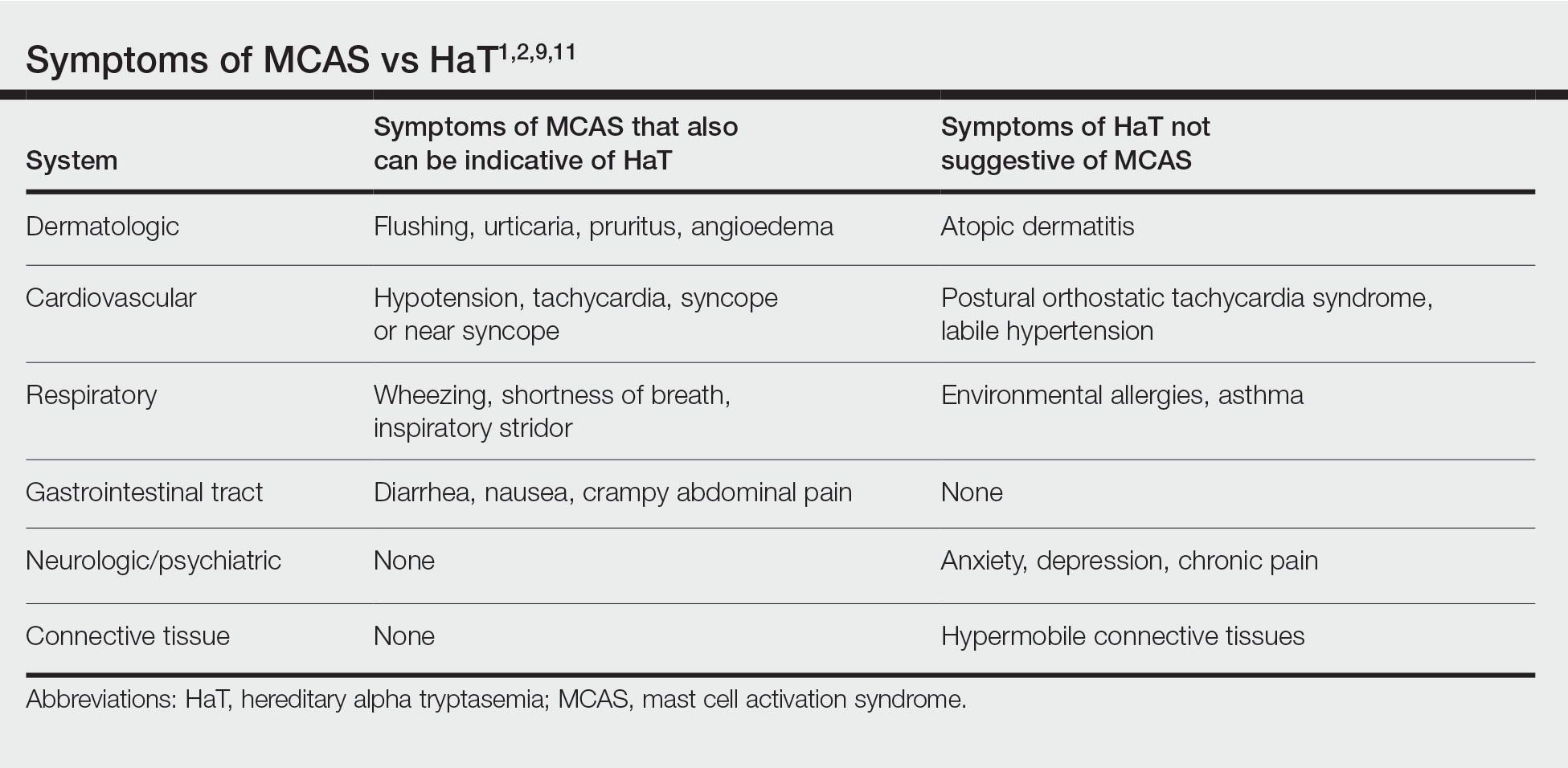

HaT and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome—In 2019, a Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report outlined recommendations for diagnosing and treating primary mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), a disorder in which mast cells seem to be more easily activated. Mast cell activation syndrome is defined as a primary clinical condition in which there are episodic signs and symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (Table) concurrently affecting at least 2 organ systems, resulting from secreted mast cell mediators.9,11 The 2019 report also touched on clinical criteria that lack precision for diagnosing MCAS yet are in use, including dermographism and several types of rashes.9 Episode triggers frequent in MCAS include hot water, alcohol, stress, exercise, infection, hormonal changes, and physical stimuli.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been suggested to be a risk factor for MCAS, which also can be associated with SM and clonal MCAS.9 Patients with MCAS should be tested for increased α-tryptase gene copy number given the overlap in symptoms, the likely predisposition of those with HaT to develop MCAS, and the fact that these patients could be at an increased risk for anaphylaxis.4,7,9,11 However, the clinical phenotype for HaT includes allergic disorders affecting the skin as well as neuropsychiatric and connective tissue abnormalities that are distinctive from MCAS. Although HaT may be considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS, MCAS is only 1 potential phenotype associated with HaT.9

Implications of HaT

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia should be considered in all patients with basal tryptase levels greater than 8 ng/mL. Cutaneous symptoms are among the most common presentations for individuals with HaT and can include AD, chronic or episodic urticaria, pruritus, flushing, and angioedema. However, HaT is unique because of the coupling of these common dermatologic findings with other abnormalities, including abdominal pain and diarrhea, hypermobile joints, and autonomic dysfunction. Patients with HaT also may manifest psychiatric concerns of anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, all of which have been linked to this disorder.

It is unclear in HaT if the presence of extra-allelic copies of tryptase in an individual is directly pathogenic. The effects of increased basal tryptase and α2β2 tetramers have been shown to likely be responsible for some of the clinical features in these individuals but also may magnify other individual underlying disease(s) or diathesis in which mast cells are naturally abundant.8 In the skin, this increased mast cell activation and subsequent histamine release frequently are visible as dermatographia and urticaria. However, mast cell numbers also are known to be increased in both psoriatic and AD skin lesions,12 thus severe presentation of these diseases in conjunction with the other symptoms associated with mast cell activation should prompt suspicion for HaT.

Effects of HaT on Other Cutaneous Disease—Given the increase of mast cells in AD skin lesions and fact that 94% of patients in the 2014 Lyons et al1 study cited a history of AD, HaT may be a risk factor in the development of AD. Interestingly, in addition to the increased mast cells in AD lesions, PAR2+ nerve fibers also are increased in AD lesions and have been implicated in the nonhistaminergic pruritus experienced by patients with AD.12 Thus, given the proposed propensity for α2β2 tetramers to activate PAR2, it is possible this mechanism may contribute to severe pruritus in individuals with AD and concurrent HaT, as those with HaT express increased α2β2 tetramers. However, no study to date has directly compared AD symptoms in patients with concurrent HaT vs patients without it. Further research is needed on how HaT impacts other allergic and inflammatory skin diseases such as AD and psoriasis, but one may reasonably consider HaT when treating chronic inflammatory skin diseases refractory to typical interventions and/or severe presentations. Although HaT is an autosomal-dominant disorder, it is not detected by standard whole exome sequencing or microarrays. A commercial test is available, utilizing a buccal swab to test for TPSAB1 copy number.

HaT and Mast Cell Disorders—When evaluating someone with suspected HaT, it is important to screen for other symptoms of mast cell activation. For instance, in the GI tract increased mast cell activation results in activation of motor neurons and nociceptors and increases secretion and peristalsis with consequent bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.10 Likewise, tryptase also has neuromodulatory effects that amplify the perception of pain and are likely responsible for the feelings of hyperalgesia reported in patients with HaT.13

There is substantial overlap in the clinical pictures of HaT and MCAS, and HaT is considered a heritable risk factor for MCAS. Consequently, any patient undergoing workup for MCAS also should be tested for HaT. Although HaT is associated with consistently elevated tryptase, MCAS is episodic in nature, and an increase in tryptase levels of at least 20% plus 2 ng/mL from baseline only in the presence of other symptoms reflective of mast cell activation (Table) is a prerequisite for diagnosis.9 Chronic signs and symptoms of atopy, chronic urticaria, and severe asthma are not indicative of MCAS but are frequently seen in HaT.

Another cause of persistently elevated tryptase levels is SM. Systemic mastocytosis is defined by aberrant clonal mast cell expansion and systemic involvement11 and can cause persistent symptoms, unlike MCAS alone. However, SM also can be associated with MCAS.9 Notably, a baseline serum tryptase level greater than 20 ng/mL—much higher than the threshold of greater than 8 ng/mL for suspicion of HaT—is seen in 75% of SM cases and is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for the disease.9,11 However, the 2016 study identifying increased TPSAB1 α-tryptase–encoding sequences as the causative entity for HaT by Lyons et al2 found the average (SD) basal serum tryptase level in individuals with α-tryptase–encoding sequence duplications to be 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL in those with triplications. Thus, there likely is no threshold for elevated baseline tryptase levels that would indicate SM over HaT as a more likely diagnosis. However, SM will present with new persistently elevated tryptase levels, whereas the elevation in HaT is believed to be lifelong.5 Also in contrast to HaT, SM can present with liver, spleen, and lymph node involvement; bone sclerosis; and cytopenia.11,14

Mastocytosis is much rarer than HaT, with an estimated prevalence of 9 cases per 100,000 individuals in the United States.11 Although HaT diagnostic testing is noninvasive, SM requires a bone marrow biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Given the likely much higher prevalence of HaT than SM and the patient burden of a bone marrow biopsy, HaT should be considered before proceeding with a bone marrow biopsy to evaluate for SM when a patient presents with persistent systemic symptoms of mast cell activation and elevated baseline tryptase levels. Furthermore, it also would be prudent to test for HaT in patients with known SM, as a cohort study by Lyons et al5 indicated that HaT is likely more common in those with SM (12.2% [10/82] of cohort with known SM vs 5.3% of 398 controls), and patients with concurrent SM and HaT were at a higher risk for severe anaphylaxis (RR=9.5; P=.007).

Studies thus far surrounding HaT have not evaluated timing of initial symptom onset or age of initial presentation for HaT. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that those with increased TPSAB1 copy number will be symptomatic, as there have been reports of asymptomatic individuals with HaT who had basal serum levels greater than 8 ng/mL.7 As research into HaT continues and larger cohorts are evaluated, questions surrounding timing of symptom onset and various factors that may make someone more likely to display a particular phenotype will be answered.

Treatment—Long-term prognosis for individuals with HaT is largely unknown. Unfortunately, there are limited data to support a single effective treatment strategy for managing HaT, and treatment has varied based on predominant symptoms. For cutaneous and GI tract symptoms, trials of maximal H1 and H2 antihistamines twice daily have been recommended.4 Omalizumab was reported to improve chronic urticaria in 3 of 3 patients, showing potential promise as a treatment.4 Mast cell stabilizers, such as oral cromolyn, have been used for severe GI symptoms, while some patients also have reported improvement with oral ketotifen.6 Other medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants, clemastine fumarate, and gabapentin, have been beneficial anecdotally.6 Given the lack of harmful effects seen in individuals who are α-tryptase deficient, α-tryptase inhibition is an intriguing target for future therapies.

Conclusion

Patients who present with a constellation of dermatologic, allergic, GI tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities consistent with HaT may receive a prompt diagnosis if the association is recognized. The full relationship between HaT and other chronic dermatologic disorders is still unknown. Ultimately, heightened interest and research into HaT will lead to more treatment options available for affected patients.

1. Lyons JJ, Sun G, Stone KD, et al. Mendelian inheritance of elevated serum tryptase associated with atopy and connective tissue abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1471-1474.

2. Lyons JJ, Yu X, Hughes JD, et al. Elevated basal serum tryptase identifies a multisystem disorder associated with increased TPSAB1 copy number. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1564-1569.

3. Schwartz L. Diagnostic value of tryptase in anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;6:451-463.

4. Giannetti MP, Weller E, Bormans C, et al. Hereditary alpha-tryptasemia in 101 patients with mast cell activation–related symptomatology including anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:655-660.

5. Lyons JJ, Chovanec J, O’Connell MP, et al. Heritable risk for severe anaphylaxis associated with increased α-tryptase–encoding germline copy number at TPSAB1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;147:622-632.

6. Lyons JJ. Hereditary alpha tryptasemia: genotyping and associated clinical features. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2018;38:483-495.

7. Robey RC, Wilcock A, Bonin H, et al. Hereditary alpha-tryptasemia: UK prevalence and variability in disease expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:3549-3556.

8. Le QT, Lyons JJ, Naranjo AN, et al. Impact of naturally forming human α/β-tryptase heterotetramers in the pathogenesis of hereditary α-tryptasemia. J Exp Med. 2019;216:2348-2361.

9. Weiler CR, Austen KF, Akin C, et al. AAAAI Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report: mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:883-896.

10. Ramsay DB, Stephen S, Borum M, et al. Mast cells in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6:772-777.

11. Giannetti A, Filice E, Caffarelli C, et al. Mast cell activation disorders. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:124.

12. Siiskonen H, Harvima I. Mast cells and sensory nerves contribute to neurogenic inflammation and pruritus in chronic skin inflammation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:422.

13. Varrassi G, Fusco M, Skaper SD, et al. A pharmacological rationale to reduce the incidence of opioid induced tolerance and hyperalgesia: a review. Pain Ther. 2018;7:59-75.

14. Núñez E, Moreno-Borque R, García-Montero A, et al. Serum tryptase monitoring in indolent systemic mastocytosis: association with disease features and patient outcome. PLoS One. 2013;8:E76116.

Hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HaT), an autosomal-dominant disorder of tryptase overproduction, was first described in 2014 by Lyons et al.1 It has been associated with multiple dermatologic, allergic, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, neuropsychiatric, respiratory, autonomic, and connective tissue abnormalities. These multisystem concerns may include cutaneous flushing, chronic pruritus, urticaria, GI tract symptoms, arthralgia, and autonomic dysfunction.2 The diverse symptoms and the recent discovery of HaT make recognition of this disorder challenging. Currently, it also is believed that HaT is associated with an elevated risk for anaphylaxis and is a biomarker for severe symptoms in disorders with increased mast cell burden such as mastocytosis.3-5

Given the potential cutaneous manifestations and the fact that dermatologic symptoms may be the initial presentation of HaT, awareness and recognition of this condition by dermatologists are essential for diagnosis and treatment. This review summarizes the cutaneous presentations consistent with HaT and discusses various conditions that share overlapping dermatologic symptoms with HaT.

Background on HaT

Mast cells are known to secrete several vasoactive mediators including tryptase and histamine when activated by foreign substances, similar to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions. In their baseline state, mast cells continuously secrete immature forms of tryptases called protryptases.6 These protryptases come in 2 forms: α and β. Although mature tryptase is acutely elevatedin anaphylaxis, persistently elevated total serum tryptase levels frequently are regarded as indicative of a systemic mast cell disorder such as systemic mastocytosis (SM).3 Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals with the disorder have an elevated basal serum tryptase level (>8 ng/mL). Hereditary alpha tryptasemia has been identified as another possible cause of persistently elevated levels.2,6

Genetics and Epidemiology of HaT—The humantryptase locus at chromosome 16p13.3 is composed of 4 paralog genes: TPSG1, TPSB2, TPSAB1, and TPSD1.4 Only TPSAB1 encodes for α-tryptase, while both TPSB2 and TPSAB1 encode for β-tryptase.4 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia is an autosomal-dominant disorder resulting from a copy number increase in the α-tryptase encoding sequence within the TPSAB1 gene. Despite the wide-ranging phenotype of HaT, all individuals identified with the disorder have a basal serum tryptase level greater than 8 ng/mL, with mean (SD) levels of 15 (5) ng/mL and 24 (6) ng/mL with gene duplication and triplication, respectively (reference range, 0–11.4 ng/mL).2,6 Hereditary alpha tryptasemia likely is common and largely undiagnosed, with a recently estimated prevalence of 5% in the United Kingdom7 and 5.6% in a cohort of 125 individuals from Italy, Slovenia, and the United States.5

Implications of Increased α-tryptase Levels—After an inciting stimulus, the active portions of α-protryptase and β-protryptase are secreted as tetramers by activated mast cells via degranulation. In vitro, β-tryptase homotetramers have been found to play a role in anaphylaxis, while α-homotetramers are nearly inactive.8,9 Recently, however, it has been discovered that α2β2 tetramers also can form and do so in a higher ratio in individuals with increased α-tryptase–encoding gene copies, such as those with HaT.8 These heterotetramers exhibit unique properties compared with the homotetramers and may stimulate epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2). Epidermal growth factor–like module-containing mucinlike hormone receptor 2 activation likely contributes to vibratory urticaria in patients, while activation of PAR2 may have a range of clinical effects, including worsening asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, pruritus, and the exacerbation of dermal inflammation and hyperalgesia.8,10 Thus, α- and β-tryptase tetramers can be considered mediators that may influence the severity of disorders in which mast cells are naturally prevalent and likely contribute to the phenotype of those with HaT.7 Furthermore, these characteristics have been shown to potentially increase in severity with increasing tryptase levels and with increased TPSAB1 duplications.1,2 In contrast, more than 25% of the population is deficient in α-tryptase without known deleterious effects.5

Cutaneous Manifestations of HaT