User login

Health information exchange in US hospitals: The current landscape and a path to improved information sharing

The US healthcare system is highly fragmented, with patients typically receiving treatment from multiple providers during an episode of care and from many more providers over their lifetime.1,2 As patients move between care delivery settings, whether and how their information follows them is determined by a haphazard and error-prone patchwork of telephone, fax, and electronic communication channels.3 The existence of more robust electronic communication channels is often dictated by factors such as which providers share the same electronic health record (EHR) vendor rather than which providers share the highest volume of patients. As a result, providers often make clinical decisions with incomplete information, increasing the chances of misdiagnosis, unsafe or suboptimal treatment, and duplicative utilization.

Providers across the continuum of care encounter challenges to optimal clinical decision-making as a result of incomplete information. These are particularly problematic among clinicians in hospitals and emergency departments (EDs). Clinical decision-making in EDs often involves urgent and critical conditions in which decisions are made under pressure. Time constraints limit provider ability to find key clinical information to accurately diagnose and safely treat patients.4-6 Even for planned inpatient care, providers are often unfamiliar with patients, and they make safer decisions when they have full access to information from outside providers.7,8

Transitions of care between hospitals and primary care settings are also fraught with gaps in information sharing. Clinical decisions made in primary care can set patients on treatment trajectories that are greatly affected by the quality of information available to the care team at the time of initial diagnosis as well as in their subsequent treatment. Primary care physicians are not universally notified when their patients are hospitalized and may not have access to detailed information about the hospitalization, which can impair their ability to provide high quality care.9-11

Widespread and effective electronic health information exchange (HIE) holds the potential to address these challenges.3 With robust, interconnected electronic systems, key pieces of a patient’s health record can be electronically accessed and reconciled during planned and unplanned care transitions. The concept of HIE is simple—make all relevant patient data available to the clinical care team at the point of care, regardless of where that information was generated. The estimated value of nationwide interoperable EHR adoption suggests large savings from the more efficient, less duplicative, and higher quality care that likely results.12,13

There has been substantial funding and activity at federal, state, and local levels to promote the development of HIE in the US. The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act has the specific goal of accelerating adoption and use of certified EHR technology coupled with the ability to exchange clinical information to support patient care.14 The HITECH programs supported specific types of HIE that were believed to be particularly critical to improving patient care and included them in the federally-defined criteria for Meaningful Use (MU) of EHRs (ie, providers receive financial incentives for achieving specific objectives). The MU criteria evolve, moving from data capture in stage 1 to improved patient outcomes in stage 3.15 The HIE criteria focus on sending and receiving summary-of-care records during care transitions.

Despite the clear benefits of HIE and substantial support stated in policy initiatives, the spread of national HIE has been slow. Today, HIE in the US is highly heterogeneous: as a result of multiple federal-, state-, community-, enterprise- and EHR vendor-level efforts, only some provider organizations are able to engage in HIE with the other provider organizations with which they routinely share patients. In this review, we offer a framework and a corresponding set of definitions to understand the current state of HIE in the US. We describe key challenges to HIE progress and offer insights into the likely path to ensure that clinicians have routine, electronic access to patient information.

FOUR KEY DIMENSIONS OF HEALTH INFORMATION EXCHANGE

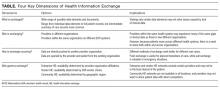

While the concept of HIE is simple—electronic access to clinical information across healthcare settings—the operationalization of HIE occurs in many different ways.16 While the terms “health information exchange” and “interoperability” are often used interchangeably, they can have different meanings. In this section, we describe 4 important dimensions that serve as a framework for understanding any given effort to enable HIE (Table).

(1) What Is Exchanged? Types of Information

The term “health information exchange” is ambiguous with respect to the type(s) of information that are accessible. Health information exchange may refer to the process of 2 providers electronically sharing a wide range of data, from a single type of information (eg, lab test results), summary of care records, to complete patient records.17 Part of this ambiguity may stem from uncertainty about the scope of information that should be shared, and how this varies based on the type of clinical encounter. For example, critical types of information in the ED setting may differ from those relevant to a primary care team after a referral. While the ability to access only particular types of information will not address all information gaps, providing access to complete patient records may result in information overload that inhibits the ability to find the subset of information relevant in a given clinical encounter.

(2) Who is Exchanging? Relationship Between Provider Organizations

The types of information accessed electronically are effectively agnostic to the relationship between the provider organizations that are sharing information. Traditionally, HIE has been considered as information that is electronically shared among 2 or more unaffiliated organizations. However, there is increasing recognition that some providers may not have electronic access to all information about their patients that exists within their organization, often after a merger or acquisition between 2 providers with different EHR systems.18,19 In these cases, a primary care team in a large integrated delivery system may have as many information gaps as a primary care team in a small, independent practice. Fulfilling clinical information needs may require both intra- and interorganizational HIE, which complicates the design of HIE processes and how the care team approaches incorporating information from both types of organizations into their decision-making. It is also important to recognize that some provider organizations, particularly small, rural practices, may not have the information technology and connectivity infrastructure required to engage in HIE.

(3) How Is Information Exchanged? Types of Electronic Access: Push vs Pull Exchange

To minimize information gaps, electronic access to information from external settings needs to offer both “push” and “pull” options. Push exchange, which can direct information electronically to a targeted recipient, works in scenarios in which there is a known information gap and known information source. The classic use for push exchange is care coordination, such as primary care physician-specialist referrals or hospital-primary care physician transitions postdischarge. Pull exchange accommodates scenarios in which there is a known information gap but the source(s) of information are unknown; it requires that clinical care teams search for and locate the clinical information that exists about the patient in external settings. Here, the classic use is emergency care in which the care team may encounter a new patient and want to retrieve records.

Widespread use of provider portals that offer view-only access into EHRs and other clinical data repositories maintained by external organizations complicate the picture. Portals are commonly used by hospitals to enable community providers to view information from a hospitalization.21 While this does not fall under the commonly held notion of HIE because no exchange occurs, portals support a pull approach to accessing information electronically among care settings that treat the same patients but use different EHRs.

Regardless of whether information is pushed or pulled, this may happen with varying degrees of human effort. This distinction gives rise to the difference between HIE and interoperability. Health information exchange reflects the ability of EHRs to exchange information, while interoperability additionally requires that EHRs be able to use exchanged information. From an operational perspective, the key distinction between HIE and interoperability is the extent of human involvement. Health information exchange requires that a human read and decide how to enter information from external settings (eg, a chart in PDF format sent between 2 EHRs), while interoperability enables the EHR that receives the information to understand the content and automatically triage or reconcile information, such as a medication list, without any human action.21 Health information exchange, therefore, relies on the diligence of the receiving clinician, while interoperability does not.

(4) What Governance Entity Defines the “Rules” of Exchange?

When more than 1 provider organization shares patient-identified data, a governance entity must specify the framework that governs the exchange. While the specifics of HIE governance vary, there are 3 predominant types of HIE networks, based on the type of organization that governs exchange: enterprise HIE networks, EHR vendor HIE networks or community HIE networks.

Enterprise HIE networks exist when 1 or more provider organizations electronically share clinical information to support patient care with some restriction, beyond geography, that dictates which organizations are involved. Typically, restrictions are driven by strategic, proprietary interests.22,23 Although broad-based information access across settings would be in the best interest of the patient, provider organizations are sensitive to the competitive implications of sharing data and may pursue such sharing in a strategic way.24 A common scenario is when hospitals choose to strategically affiliate with select ambulatory providers and exclusively exchange information with them. This should facilitate better care coordination for patients shared by the hospital and those providers but can also benefit the hospital by increasing the referrals from those providers. While there is little direct evidence quantifying the extent to which this type of strategic sharing takes place, there have been anecdotal reports as well as indirect findings that for-profit hospitals in competitive markets are less likely to share patient data.19,25

EHR vendor HIE networks exist when exchange occurs within a community of provider organizations that use an EHR from the same vendor. A subset of EHR vendors have made this capability available; EPIC’s CareEverywhere solution27 is the best-known example. Providers with an EPIC EHR are able to query for and retrieve summary of care records and other documents from any provider organization with EPIC that has activated this functionality. There are also multivendor efforts, such as CommonWell27 and the Sequoia Project’s Carequality collaborative,28 which are initiatives that seek to provide a common interoperability framework across a diverse set of stakeholders, including provider organizations with different EHR systems, in a similar fashion to HIE modules like CareEverywhere. To date, growth in these cross-vendor collaborations has been slow, and they have limited participation. While HIE networks that involve EHR vendors are likely to grow, it is difficult to predict how quickly because they are still in an early phase of development, and face nontechnical barriers such as patient consent policies that vary between providers and across states.

Community HIE networks—also referred to as health information organizations (HIOs) or regional health information organizations (RHIOs)—exist when provider organizations in a community, frequently state-level organizations that were funded through HITECH grants,14 set up the technical infrastructure and governance approach to engage in HIE to improve patient care. In contrast to enterprise or vendor HIE networks that have pursued HIE in ways that appear strategically beneficial, the only restriction on participation in community and state HIE networks is usually geography because they view information exchange as a public good. Seventyone percent of hospital service areas (HSAs) are covered by at least 1 of the 106 operational HIOs, with 309,793 clinicians (licensed prescribers) participating in those exchange networks. Even with early infusions of public and other grant-funding, community HIE networks have experienced significant challenges to sustained operation, and many have ceased operating.29

Thus, for any given provider organization, available HIE networks are primarily shaped by 3 factors:

1. Geographic location, which determines the available community and state HIE networks (as well as other basic information technology and connectivity infrastructure); providers located outside the service areas covered by an operational HIE have little incentive to participate because they do not connect them to providers with whom they share patients. Providers in rural areas may simply not have the needed infrastructure to pursue HIE.

2. Type of organization to which they belong, which determines the available enterprise HIE networks; providers who are not members of large health systems may be excluded from participation in these types of networks.

3. EHR vendor, which determines whether they have access to an EHR vendor HIE network.

ONGOING CHALLENGES

Despite agreement about the substantial potential of HIE to reduce costs and increase the quality of care delivered across a broad range of providers, HIE progress has been slow. While HITECH has successfully increased EHR adoption in hospitals and ambulatory practices,30 HIE has lagged. This is largely because many complex, intertwined barriers must be addressed for HIE to be widespread.

Lack of a Defined Goal

The cost and complexity associated with the exchange of a single type of data (eg, medications) is substantially less than the cost and complexity of sharing complete patient records. There has been little industry consensus on the target goal—do we need to enable sharing of complete patient records across all providers, or will summary of care records suffice? If the latter, as is the focus of the current MU criteria, what types of information should be included in a summary of care record, and should content and/or structure vary depending on the type of care transition? While the MU criteria require the exchange of a summary of care record with defined data fields, it remains unclear whether this is the end state or whether we should continue to push towards broad-based sharing of all patient data as structured elements. Without a clear picture of the ideal end state, there has been significant heterogeneity in the development of HIE capabilities across providers and vendors, and difficulty coordinating efforts to continue to advance towards a nationwide approach. Addressing this issue also requires progress to define HIE usability, that is, how information from external organizations should be presented and integrated into clinical workflow and clinical decisions. Currently, where HIE is occurring and clinicians are receiving summary of care records, they find them long, cluttered, and difficult to locate key information.

Numerous, Complex Barriers Spanning Multiple Stakeholders

In the context of any individual HIE effort, even after the goal is defined, there are a myriad of challenges. In a recent survey of HIO efforts, many identified the following barriers as substantially impeding their development: establishing a sustainable business model, lack of funding, integration of HIE into provider workflow, limitations of current data standards, and working with governmental policy and mandates.30 What is notable about this list is that the barriers span an array of areas, including financial incentives and identifying a sustainable business model, technical barriers such as working within the limitations of data standards, and regulatory issues such as state laws that govern the requirements for patient consent to exchange personal health information. Overcoming any of these issues is challenging, but trying to tackle all of them simultaneously clearly reveals why progress has been slow. Further, resolving many of the issues involve different groups of stakeholders. For example, implementing appropriate patient consent procedures can require engaging with and harmonizing the regulations of multiple states, as well as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and regulations specific to substance abuse data.

Weak or Misaligned Incentives

Among the top barriers to HIE efforts are those related to funding and lack of a sustainable business model. This reflects the fact that economic incentives in the current market have not promoted provider engagement in HIE. Traditional fee-for-service payment structures do not reward providers for avoiding duplicative care.31 Further, hospitals perceive patient data as a “key strategic asset, tying physicians and patients to their organization,”24 and are reluctant to share data with competitors. Compounding the problem is that EHR vendors have a business interest in using HIE as a lever to increase revenue. In the short-term, they can charge high fees for interfaces and other HIE-related functionality. In the long-run, vendors may try to influence provider choice of system by making it difficult to engage in cross-vendor exchange.32 Information blocking—when providers or vendors knowingly interfere with HIE33—reflects not only weak incentives, but perverse incentives. While not all providers and vendors experience perverse incentives, the combination of weak and perverse incentives suggests the need to strengthen incentives, so that both types of stakeholders are motivated to tackle the barriers to HIE development. Key to strengthening incentives are payers, who are thought to be the largest beneficiaries of HIE. Payers have been reluctant to make significant investments in HIE without a more active voice in its implementation,34 but a shift to value-based payment may increase their engagement.

THE PATH FORWARD

Despite the continued challenges to nationwide HIE, several policy and technology developments show promise. Stage 3 meaningful use criteria continue to build on previous stages in increasing HIE requirements, raising the threshold for electronic exchange and EHR integration of summary of care documentation in patient transitions. The recently released Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) proposed rule replaces stage 3 meaningful use for Medicare-eligible providers with advancing care information (ACI), which accounts for 25% of a provider’s overall incentive reimbursement and includes multiple HIE criteria for providers to report as part of the base and performance score, and follows a very similar framework to stage 3 MU with its criteria regarding HIE.35 While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has not publicly declared that stage 3 MU will be replaced by ACI for hospitals and Medicaid providers, it is likely it will align those programs with the newly announced Medicare incentives.

MACRA also included changes to the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) EHR certification program in an attempt to further encourage HIE. Vendors and providers must attest that they do not engage in information blocking and will cooperate with the Office’s surveillance programs to that effect. They also must attest that, to the greatest degree possible, their EHR systems allow for bi-directional interoperability with other providers, including those with different EHR vendors, and timely access for patients to view, download, and transmit their health data. In addition, there are emerging federal efforts to pursue a more standardized approach to patient matching and harmonize consent policies across states. These types of new policy initiatives indicate a continued interest in prioritizing HIE and interoperability.21

New technologies may also help spur HIE progress. The newest policy initiatives from CMS, including stage 3 MU and MACRA, have looked to incentivize the creation of application program interfaces (APIs), a set of publicly available tools from EHR vendors to allow developers to build applications that can directly interface with, and retrieve data from, their EHRs. While most patient access to electronic health data to date has been accomplished via patient portals, open APIs would enable developers to build an array of programs for consumers to view, download, and transmit their health data.

Even more promising is the development of the newest Health Level 7 data transmission standard, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), which promises to dramatically simplify the technical aspects of interoperability. FHIR utilizes a human-readable, easy to implement modular “resources” standard that may alleviate many technical challenges that come with implementation of an HIE system, enabling cheaper and simpler interoperability.36 A consortium of EHR vendors are working together to test these standards.28 The new FHIR standards also work in conjunction with APIs to allow easier development of consumer-facing applications37 that may empower patients to take ownership of their health data.

CONCLUSION

While HIE holds great promise to reduce the cost and improve the quality of care, progress towards a nationally interoperable health system has been slow. Simply defining HIE and what types of HIE are needed in different clinical scenarios has proven challenging. The additional challenges to implementing HIE in complex technology, legal/regulatory, governance, and incentive environment are not without solutions. Continued policy interventions, private sector collaborations, and new technologies may hold the keys to realizing the vast potential of electronic HIE.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1130-1139. PubMed

2. Finnell JT, Overhage JM, Dexter PR, Perkins SM, Lane KA, McDonald CJ. Community clinical data exchange for emergency medicine patients. Paper presented at: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2003. PubMed

3. Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care-a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064-1071. PubMed

4. Franczak MJ, Klein M, Raslau F, Bergholte J, Mark LP, Ulmer JL. In emergency departments, radiologists’ access to EHRs may influence interpretations and medical management. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):800-806. PubMed

5. Shapiro JS, Kannry J, Kushniruk AW, Kuperman G; New York Clinical Information Exchange (NYCLIX) Clinical Advisory Subcommittee. Emergency physicians’ perceptions of health information exchange. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(6):700-705. PubMed

6. Shapiro JS, Kannry J, Lipton M, et al. Approaches to patient health information exchange and their impact on emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(4):426-432. PubMed

7. Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med.. 2004;79(2):186-194. PubMed

8. Kaelber DC, Bates DW. Health information exchange and patient safety. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40(suppl 6):S40-S45. PubMed

9. Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. MIssing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA. 2005;293(5):565-571. PubMed

10. Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381-386. PubMed

11. van Walraven C, Taljaard M, Bell CM, et al. A prospective cohort study found that provider and information continuity was low after patient discharge from hospital. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(9):1000-1010. PubMed

12. Walker J, Pan E, Johnston D, Adler-Milstein J, Bates DW, Middleton B. The value of health care information exchange and interoperability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005:(suppl)W5-10-W5-18. PubMed

13. Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Keeler EB. Costs and benefits of health information technology. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2006;132:1-71. PubMed

14. Blumenthal D. Launching HITECH. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):382-385. PubMed

15. Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):501-504. PubMed

16. Kuperman G, McGowan J. Potential unintended consequences of health information exchange. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(12):1663-1666. PubMed

17. Mathematica Policy Research and Harvard School of Public Health. DesRoches CM, Painter MW, Jha AK, eds. Health Information Technology in the United States, 2015: Transition to a Post-HITECH World (Executive Summary). September 18, 2015. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2015.

18. O’Malley AS, Anglin G, Bond AM, Cunningham PJ, Stark LB, Yee T. Greenville & Spartanburg: Surging Hospital Employment of Physicians Poses Opportunities and Challenges. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC); February 2011. 6.

19. Katz A, Bond AM, Carrier E, Docteur E, Quach CW, Yee T. Cleveland Hospital Systems Expand Despite Weak Economy. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC); September 2010. 2.

20. Grossman JM, Bodenheimer TS, McKenzie K. Hospital-physician portals: the role of competition in driving clinical data exchange. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(6):1629-1636. PubMed

21. De Salvo KB, Galvez E. Connecting Health and Care for the Nation A Shared Nationwide Interoperability Roadmap - Version 1.0. In: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ed 2015. https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/electronic-health-and-medical-records/interoperability-electronic-health-and-medical-records/connecting-health-care-nation-shared-nationwide-interoperability-roadmap-version-10/. Accessed September 3, 2016.

22. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches C, Jha AK. Health information exchange among US hospitals. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(11):761-768. PubMed

23. Vest JR. More than just a question of technology: factors related to hospitals’ adoption and implementation of health information exchange. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(12):797-806. PubMed

24. Grossman JM, Kushner KL, November EA. Creating sustainable local health information exchanges: can barriers to stakeholder participation be overcome? Res Brief. 2008;2:1-12. PubMed

25. Grossman JM, Cohen G. Despite regulatory changes, hospitals cautious in helping physicians purchase electronic medical records. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change 2008;123:1-4. PubMed

26. Kaelber DC, Waheed R, Einstadter D, Love TE, Cebul RD. Use and perceived value of health information exchange: one public healthcare system’s experience. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(10 spec no):SP337-SP343. PubMed

27. Commonwell Health Alliance. http://www.commonwellalliance.org/, 2016. Accessed September 3, 2016.

28. Carequality. http://sequoiaproject.org/carequality/, 2016. Accessed September 3, 2016.

29. Adler-Milstein J, Lin SC, Jha AK. The number of health information exchange efforts is declining, leaving the viability of broad clinical data exchange uncertain. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1278-1285. PubMed

30. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches CM, Kralovec P, et al. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: progress continues, but challenges persist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015:34(12):2174-2180. PubMed

31. Health IT Policy Committee Report to Congress: Challenges and Barriers to Interoperability. 2015. https://www.healthit.gov/facas/health-it-policy-committee/health-it-policy-committee-recommendations-national-coordinator-health-it. Accessed September 3, 2016.

32. Everson J, Adler-Milstein J. Engagement in hospital health information exchange is associated with vendor marketplace dominance. Health Aff (MIllwood). 2016;35(7):1286-1293. PubMed

33. Downing K, Mason J. ONC targets information blocking. J AHIMA. 2015;86(7):36-38. PubMed

34. Cross DA, Lin SC, Adler-Milstein J. Assessing payer perspectives on health information exchange. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(2):297-303. PubMed

35. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MACRA: MIPS and APMs. 2016; https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Accessed September 3, 2016.

36. Raths D. Trend: standards development. Catching FHIR. A new HL7 draft standard may boost web services development in healthcare. Healthc Inform. 2014;31(2):13,16. PubMed

37. Alterovitz G, Warner J, Zhang P, et al. SMART on FHIR genomics: facilitating

The US healthcare system is highly fragmented, with patients typically receiving treatment from multiple providers during an episode of care and from many more providers over their lifetime.1,2 As patients move between care delivery settings, whether and how their information follows them is determined by a haphazard and error-prone patchwork of telephone, fax, and electronic communication channels.3 The existence of more robust electronic communication channels is often dictated by factors such as which providers share the same electronic health record (EHR) vendor rather than which providers share the highest volume of patients. As a result, providers often make clinical decisions with incomplete information, increasing the chances of misdiagnosis, unsafe or suboptimal treatment, and duplicative utilization.

Providers across the continuum of care encounter challenges to optimal clinical decision-making as a result of incomplete information. These are particularly problematic among clinicians in hospitals and emergency departments (EDs). Clinical decision-making in EDs often involves urgent and critical conditions in which decisions are made under pressure. Time constraints limit provider ability to find key clinical information to accurately diagnose and safely treat patients.4-6 Even for planned inpatient care, providers are often unfamiliar with patients, and they make safer decisions when they have full access to information from outside providers.7,8

Transitions of care between hospitals and primary care settings are also fraught with gaps in information sharing. Clinical decisions made in primary care can set patients on treatment trajectories that are greatly affected by the quality of information available to the care team at the time of initial diagnosis as well as in their subsequent treatment. Primary care physicians are not universally notified when their patients are hospitalized and may not have access to detailed information about the hospitalization, which can impair their ability to provide high quality care.9-11

Widespread and effective electronic health information exchange (HIE) holds the potential to address these challenges.3 With robust, interconnected electronic systems, key pieces of a patient’s health record can be electronically accessed and reconciled during planned and unplanned care transitions. The concept of HIE is simple—make all relevant patient data available to the clinical care team at the point of care, regardless of where that information was generated. The estimated value of nationwide interoperable EHR adoption suggests large savings from the more efficient, less duplicative, and higher quality care that likely results.12,13

There has been substantial funding and activity at federal, state, and local levels to promote the development of HIE in the US. The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act has the specific goal of accelerating adoption and use of certified EHR technology coupled with the ability to exchange clinical information to support patient care.14 The HITECH programs supported specific types of HIE that were believed to be particularly critical to improving patient care and included them in the federally-defined criteria for Meaningful Use (MU) of EHRs (ie, providers receive financial incentives for achieving specific objectives). The MU criteria evolve, moving from data capture in stage 1 to improved patient outcomes in stage 3.15 The HIE criteria focus on sending and receiving summary-of-care records during care transitions.

Despite the clear benefits of HIE and substantial support stated in policy initiatives, the spread of national HIE has been slow. Today, HIE in the US is highly heterogeneous: as a result of multiple federal-, state-, community-, enterprise- and EHR vendor-level efforts, only some provider organizations are able to engage in HIE with the other provider organizations with which they routinely share patients. In this review, we offer a framework and a corresponding set of definitions to understand the current state of HIE in the US. We describe key challenges to HIE progress and offer insights into the likely path to ensure that clinicians have routine, electronic access to patient information.

FOUR KEY DIMENSIONS OF HEALTH INFORMATION EXCHANGE

While the concept of HIE is simple—electronic access to clinical information across healthcare settings—the operationalization of HIE occurs in many different ways.16 While the terms “health information exchange” and “interoperability” are often used interchangeably, they can have different meanings. In this section, we describe 4 important dimensions that serve as a framework for understanding any given effort to enable HIE (Table).

(1) What Is Exchanged? Types of Information

The term “health information exchange” is ambiguous with respect to the type(s) of information that are accessible. Health information exchange may refer to the process of 2 providers electronically sharing a wide range of data, from a single type of information (eg, lab test results), summary of care records, to complete patient records.17 Part of this ambiguity may stem from uncertainty about the scope of information that should be shared, and how this varies based on the type of clinical encounter. For example, critical types of information in the ED setting may differ from those relevant to a primary care team after a referral. While the ability to access only particular types of information will not address all information gaps, providing access to complete patient records may result in information overload that inhibits the ability to find the subset of information relevant in a given clinical encounter.

(2) Who is Exchanging? Relationship Between Provider Organizations

The types of information accessed electronically are effectively agnostic to the relationship between the provider organizations that are sharing information. Traditionally, HIE has been considered as information that is electronically shared among 2 or more unaffiliated organizations. However, there is increasing recognition that some providers may not have electronic access to all information about their patients that exists within their organization, often after a merger or acquisition between 2 providers with different EHR systems.18,19 In these cases, a primary care team in a large integrated delivery system may have as many information gaps as a primary care team in a small, independent practice. Fulfilling clinical information needs may require both intra- and interorganizational HIE, which complicates the design of HIE processes and how the care team approaches incorporating information from both types of organizations into their decision-making. It is also important to recognize that some provider organizations, particularly small, rural practices, may not have the information technology and connectivity infrastructure required to engage in HIE.

(3) How Is Information Exchanged? Types of Electronic Access: Push vs Pull Exchange

To minimize information gaps, electronic access to information from external settings needs to offer both “push” and “pull” options. Push exchange, which can direct information electronically to a targeted recipient, works in scenarios in which there is a known information gap and known information source. The classic use for push exchange is care coordination, such as primary care physician-specialist referrals or hospital-primary care physician transitions postdischarge. Pull exchange accommodates scenarios in which there is a known information gap but the source(s) of information are unknown; it requires that clinical care teams search for and locate the clinical information that exists about the patient in external settings. Here, the classic use is emergency care in which the care team may encounter a new patient and want to retrieve records.

Widespread use of provider portals that offer view-only access into EHRs and other clinical data repositories maintained by external organizations complicate the picture. Portals are commonly used by hospitals to enable community providers to view information from a hospitalization.21 While this does not fall under the commonly held notion of HIE because no exchange occurs, portals support a pull approach to accessing information electronically among care settings that treat the same patients but use different EHRs.

Regardless of whether information is pushed or pulled, this may happen with varying degrees of human effort. This distinction gives rise to the difference between HIE and interoperability. Health information exchange reflects the ability of EHRs to exchange information, while interoperability additionally requires that EHRs be able to use exchanged information. From an operational perspective, the key distinction between HIE and interoperability is the extent of human involvement. Health information exchange requires that a human read and decide how to enter information from external settings (eg, a chart in PDF format sent between 2 EHRs), while interoperability enables the EHR that receives the information to understand the content and automatically triage or reconcile information, such as a medication list, without any human action.21 Health information exchange, therefore, relies on the diligence of the receiving clinician, while interoperability does not.

(4) What Governance Entity Defines the “Rules” of Exchange?

When more than 1 provider organization shares patient-identified data, a governance entity must specify the framework that governs the exchange. While the specifics of HIE governance vary, there are 3 predominant types of HIE networks, based on the type of organization that governs exchange: enterprise HIE networks, EHR vendor HIE networks or community HIE networks.

Enterprise HIE networks exist when 1 or more provider organizations electronically share clinical information to support patient care with some restriction, beyond geography, that dictates which organizations are involved. Typically, restrictions are driven by strategic, proprietary interests.22,23 Although broad-based information access across settings would be in the best interest of the patient, provider organizations are sensitive to the competitive implications of sharing data and may pursue such sharing in a strategic way.24 A common scenario is when hospitals choose to strategically affiliate with select ambulatory providers and exclusively exchange information with them. This should facilitate better care coordination for patients shared by the hospital and those providers but can also benefit the hospital by increasing the referrals from those providers. While there is little direct evidence quantifying the extent to which this type of strategic sharing takes place, there have been anecdotal reports as well as indirect findings that for-profit hospitals in competitive markets are less likely to share patient data.19,25

EHR vendor HIE networks exist when exchange occurs within a community of provider organizations that use an EHR from the same vendor. A subset of EHR vendors have made this capability available; EPIC’s CareEverywhere solution27 is the best-known example. Providers with an EPIC EHR are able to query for and retrieve summary of care records and other documents from any provider organization with EPIC that has activated this functionality. There are also multivendor efforts, such as CommonWell27 and the Sequoia Project’s Carequality collaborative,28 which are initiatives that seek to provide a common interoperability framework across a diverse set of stakeholders, including provider organizations with different EHR systems, in a similar fashion to HIE modules like CareEverywhere. To date, growth in these cross-vendor collaborations has been slow, and they have limited participation. While HIE networks that involve EHR vendors are likely to grow, it is difficult to predict how quickly because they are still in an early phase of development, and face nontechnical barriers such as patient consent policies that vary between providers and across states.

Community HIE networks—also referred to as health information organizations (HIOs) or regional health information organizations (RHIOs)—exist when provider organizations in a community, frequently state-level organizations that were funded through HITECH grants,14 set up the technical infrastructure and governance approach to engage in HIE to improve patient care. In contrast to enterprise or vendor HIE networks that have pursued HIE in ways that appear strategically beneficial, the only restriction on participation in community and state HIE networks is usually geography because they view information exchange as a public good. Seventyone percent of hospital service areas (HSAs) are covered by at least 1 of the 106 operational HIOs, with 309,793 clinicians (licensed prescribers) participating in those exchange networks. Even with early infusions of public and other grant-funding, community HIE networks have experienced significant challenges to sustained operation, and many have ceased operating.29

Thus, for any given provider organization, available HIE networks are primarily shaped by 3 factors:

1. Geographic location, which determines the available community and state HIE networks (as well as other basic information technology and connectivity infrastructure); providers located outside the service areas covered by an operational HIE have little incentive to participate because they do not connect them to providers with whom they share patients. Providers in rural areas may simply not have the needed infrastructure to pursue HIE.

2. Type of organization to which they belong, which determines the available enterprise HIE networks; providers who are not members of large health systems may be excluded from participation in these types of networks.

3. EHR vendor, which determines whether they have access to an EHR vendor HIE network.

ONGOING CHALLENGES

Despite agreement about the substantial potential of HIE to reduce costs and increase the quality of care delivered across a broad range of providers, HIE progress has been slow. While HITECH has successfully increased EHR adoption in hospitals and ambulatory practices,30 HIE has lagged. This is largely because many complex, intertwined barriers must be addressed for HIE to be widespread.

Lack of a Defined Goal

The cost and complexity associated with the exchange of a single type of data (eg, medications) is substantially less than the cost and complexity of sharing complete patient records. There has been little industry consensus on the target goal—do we need to enable sharing of complete patient records across all providers, or will summary of care records suffice? If the latter, as is the focus of the current MU criteria, what types of information should be included in a summary of care record, and should content and/or structure vary depending on the type of care transition? While the MU criteria require the exchange of a summary of care record with defined data fields, it remains unclear whether this is the end state or whether we should continue to push towards broad-based sharing of all patient data as structured elements. Without a clear picture of the ideal end state, there has been significant heterogeneity in the development of HIE capabilities across providers and vendors, and difficulty coordinating efforts to continue to advance towards a nationwide approach. Addressing this issue also requires progress to define HIE usability, that is, how information from external organizations should be presented and integrated into clinical workflow and clinical decisions. Currently, where HIE is occurring and clinicians are receiving summary of care records, they find them long, cluttered, and difficult to locate key information.

Numerous, Complex Barriers Spanning Multiple Stakeholders

In the context of any individual HIE effort, even after the goal is defined, there are a myriad of challenges. In a recent survey of HIO efforts, many identified the following barriers as substantially impeding their development: establishing a sustainable business model, lack of funding, integration of HIE into provider workflow, limitations of current data standards, and working with governmental policy and mandates.30 What is notable about this list is that the barriers span an array of areas, including financial incentives and identifying a sustainable business model, technical barriers such as working within the limitations of data standards, and regulatory issues such as state laws that govern the requirements for patient consent to exchange personal health information. Overcoming any of these issues is challenging, but trying to tackle all of them simultaneously clearly reveals why progress has been slow. Further, resolving many of the issues involve different groups of stakeholders. For example, implementing appropriate patient consent procedures can require engaging with and harmonizing the regulations of multiple states, as well as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and regulations specific to substance abuse data.

Weak or Misaligned Incentives

Among the top barriers to HIE efforts are those related to funding and lack of a sustainable business model. This reflects the fact that economic incentives in the current market have not promoted provider engagement in HIE. Traditional fee-for-service payment structures do not reward providers for avoiding duplicative care.31 Further, hospitals perceive patient data as a “key strategic asset, tying physicians and patients to their organization,”24 and are reluctant to share data with competitors. Compounding the problem is that EHR vendors have a business interest in using HIE as a lever to increase revenue. In the short-term, they can charge high fees for interfaces and other HIE-related functionality. In the long-run, vendors may try to influence provider choice of system by making it difficult to engage in cross-vendor exchange.32 Information blocking—when providers or vendors knowingly interfere with HIE33—reflects not only weak incentives, but perverse incentives. While not all providers and vendors experience perverse incentives, the combination of weak and perverse incentives suggests the need to strengthen incentives, so that both types of stakeholders are motivated to tackle the barriers to HIE development. Key to strengthening incentives are payers, who are thought to be the largest beneficiaries of HIE. Payers have been reluctant to make significant investments in HIE without a more active voice in its implementation,34 but a shift to value-based payment may increase their engagement.

THE PATH FORWARD

Despite the continued challenges to nationwide HIE, several policy and technology developments show promise. Stage 3 meaningful use criteria continue to build on previous stages in increasing HIE requirements, raising the threshold for electronic exchange and EHR integration of summary of care documentation in patient transitions. The recently released Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) proposed rule replaces stage 3 meaningful use for Medicare-eligible providers with advancing care information (ACI), which accounts for 25% of a provider’s overall incentive reimbursement and includes multiple HIE criteria for providers to report as part of the base and performance score, and follows a very similar framework to stage 3 MU with its criteria regarding HIE.35 While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has not publicly declared that stage 3 MU will be replaced by ACI for hospitals and Medicaid providers, it is likely it will align those programs with the newly announced Medicare incentives.

MACRA also included changes to the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) EHR certification program in an attempt to further encourage HIE. Vendors and providers must attest that they do not engage in information blocking and will cooperate with the Office’s surveillance programs to that effect. They also must attest that, to the greatest degree possible, their EHR systems allow for bi-directional interoperability with other providers, including those with different EHR vendors, and timely access for patients to view, download, and transmit their health data. In addition, there are emerging federal efforts to pursue a more standardized approach to patient matching and harmonize consent policies across states. These types of new policy initiatives indicate a continued interest in prioritizing HIE and interoperability.21

New technologies may also help spur HIE progress. The newest policy initiatives from CMS, including stage 3 MU and MACRA, have looked to incentivize the creation of application program interfaces (APIs), a set of publicly available tools from EHR vendors to allow developers to build applications that can directly interface with, and retrieve data from, their EHRs. While most patient access to electronic health data to date has been accomplished via patient portals, open APIs would enable developers to build an array of programs for consumers to view, download, and transmit their health data.

Even more promising is the development of the newest Health Level 7 data transmission standard, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), which promises to dramatically simplify the technical aspects of interoperability. FHIR utilizes a human-readable, easy to implement modular “resources” standard that may alleviate many technical challenges that come with implementation of an HIE system, enabling cheaper and simpler interoperability.36 A consortium of EHR vendors are working together to test these standards.28 The new FHIR standards also work in conjunction with APIs to allow easier development of consumer-facing applications37 that may empower patients to take ownership of their health data.

CONCLUSION

While HIE holds great promise to reduce the cost and improve the quality of care, progress towards a nationally interoperable health system has been slow. Simply defining HIE and what types of HIE are needed in different clinical scenarios has proven challenging. The additional challenges to implementing HIE in complex technology, legal/regulatory, governance, and incentive environment are not without solutions. Continued policy interventions, private sector collaborations, and new technologies may hold the keys to realizing the vast potential of electronic HIE.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

The US healthcare system is highly fragmented, with patients typically receiving treatment from multiple providers during an episode of care and from many more providers over their lifetime.1,2 As patients move between care delivery settings, whether and how their information follows them is determined by a haphazard and error-prone patchwork of telephone, fax, and electronic communication channels.3 The existence of more robust electronic communication channels is often dictated by factors such as which providers share the same electronic health record (EHR) vendor rather than which providers share the highest volume of patients. As a result, providers often make clinical decisions with incomplete information, increasing the chances of misdiagnosis, unsafe or suboptimal treatment, and duplicative utilization.

Providers across the continuum of care encounter challenges to optimal clinical decision-making as a result of incomplete information. These are particularly problematic among clinicians in hospitals and emergency departments (EDs). Clinical decision-making in EDs often involves urgent and critical conditions in which decisions are made under pressure. Time constraints limit provider ability to find key clinical information to accurately diagnose and safely treat patients.4-6 Even for planned inpatient care, providers are often unfamiliar with patients, and they make safer decisions when they have full access to information from outside providers.7,8

Transitions of care between hospitals and primary care settings are also fraught with gaps in information sharing. Clinical decisions made in primary care can set patients on treatment trajectories that are greatly affected by the quality of information available to the care team at the time of initial diagnosis as well as in their subsequent treatment. Primary care physicians are not universally notified when their patients are hospitalized and may not have access to detailed information about the hospitalization, which can impair their ability to provide high quality care.9-11

Widespread and effective electronic health information exchange (HIE) holds the potential to address these challenges.3 With robust, interconnected electronic systems, key pieces of a patient’s health record can be electronically accessed and reconciled during planned and unplanned care transitions. The concept of HIE is simple—make all relevant patient data available to the clinical care team at the point of care, regardless of where that information was generated. The estimated value of nationwide interoperable EHR adoption suggests large savings from the more efficient, less duplicative, and higher quality care that likely results.12,13

There has been substantial funding and activity at federal, state, and local levels to promote the development of HIE in the US. The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act has the specific goal of accelerating adoption and use of certified EHR technology coupled with the ability to exchange clinical information to support patient care.14 The HITECH programs supported specific types of HIE that were believed to be particularly critical to improving patient care and included them in the federally-defined criteria for Meaningful Use (MU) of EHRs (ie, providers receive financial incentives for achieving specific objectives). The MU criteria evolve, moving from data capture in stage 1 to improved patient outcomes in stage 3.15 The HIE criteria focus on sending and receiving summary-of-care records during care transitions.

Despite the clear benefits of HIE and substantial support stated in policy initiatives, the spread of national HIE has been slow. Today, HIE in the US is highly heterogeneous: as a result of multiple federal-, state-, community-, enterprise- and EHR vendor-level efforts, only some provider organizations are able to engage in HIE with the other provider organizations with which they routinely share patients. In this review, we offer a framework and a corresponding set of definitions to understand the current state of HIE in the US. We describe key challenges to HIE progress and offer insights into the likely path to ensure that clinicians have routine, electronic access to patient information.

FOUR KEY DIMENSIONS OF HEALTH INFORMATION EXCHANGE

While the concept of HIE is simple—electronic access to clinical information across healthcare settings—the operationalization of HIE occurs in many different ways.16 While the terms “health information exchange” and “interoperability” are often used interchangeably, they can have different meanings. In this section, we describe 4 important dimensions that serve as a framework for understanding any given effort to enable HIE (Table).

(1) What Is Exchanged? Types of Information

The term “health information exchange” is ambiguous with respect to the type(s) of information that are accessible. Health information exchange may refer to the process of 2 providers electronically sharing a wide range of data, from a single type of information (eg, lab test results), summary of care records, to complete patient records.17 Part of this ambiguity may stem from uncertainty about the scope of information that should be shared, and how this varies based on the type of clinical encounter. For example, critical types of information in the ED setting may differ from those relevant to a primary care team after a referral. While the ability to access only particular types of information will not address all information gaps, providing access to complete patient records may result in information overload that inhibits the ability to find the subset of information relevant in a given clinical encounter.

(2) Who is Exchanging? Relationship Between Provider Organizations

The types of information accessed electronically are effectively agnostic to the relationship between the provider organizations that are sharing information. Traditionally, HIE has been considered as information that is electronically shared among 2 or more unaffiliated organizations. However, there is increasing recognition that some providers may not have electronic access to all information about their patients that exists within their organization, often after a merger or acquisition between 2 providers with different EHR systems.18,19 In these cases, a primary care team in a large integrated delivery system may have as many information gaps as a primary care team in a small, independent practice. Fulfilling clinical information needs may require both intra- and interorganizational HIE, which complicates the design of HIE processes and how the care team approaches incorporating information from both types of organizations into their decision-making. It is also important to recognize that some provider organizations, particularly small, rural practices, may not have the information technology and connectivity infrastructure required to engage in HIE.

(3) How Is Information Exchanged? Types of Electronic Access: Push vs Pull Exchange

To minimize information gaps, electronic access to information from external settings needs to offer both “push” and “pull” options. Push exchange, which can direct information electronically to a targeted recipient, works in scenarios in which there is a known information gap and known information source. The classic use for push exchange is care coordination, such as primary care physician-specialist referrals or hospital-primary care physician transitions postdischarge. Pull exchange accommodates scenarios in which there is a known information gap but the source(s) of information are unknown; it requires that clinical care teams search for and locate the clinical information that exists about the patient in external settings. Here, the classic use is emergency care in which the care team may encounter a new patient and want to retrieve records.

Widespread use of provider portals that offer view-only access into EHRs and other clinical data repositories maintained by external organizations complicate the picture. Portals are commonly used by hospitals to enable community providers to view information from a hospitalization.21 While this does not fall under the commonly held notion of HIE because no exchange occurs, portals support a pull approach to accessing information electronically among care settings that treat the same patients but use different EHRs.

Regardless of whether information is pushed or pulled, this may happen with varying degrees of human effort. This distinction gives rise to the difference between HIE and interoperability. Health information exchange reflects the ability of EHRs to exchange information, while interoperability additionally requires that EHRs be able to use exchanged information. From an operational perspective, the key distinction between HIE and interoperability is the extent of human involvement. Health information exchange requires that a human read and decide how to enter information from external settings (eg, a chart in PDF format sent between 2 EHRs), while interoperability enables the EHR that receives the information to understand the content and automatically triage or reconcile information, such as a medication list, without any human action.21 Health information exchange, therefore, relies on the diligence of the receiving clinician, while interoperability does not.

(4) What Governance Entity Defines the “Rules” of Exchange?

When more than 1 provider organization shares patient-identified data, a governance entity must specify the framework that governs the exchange. While the specifics of HIE governance vary, there are 3 predominant types of HIE networks, based on the type of organization that governs exchange: enterprise HIE networks, EHR vendor HIE networks or community HIE networks.

Enterprise HIE networks exist when 1 or more provider organizations electronically share clinical information to support patient care with some restriction, beyond geography, that dictates which organizations are involved. Typically, restrictions are driven by strategic, proprietary interests.22,23 Although broad-based information access across settings would be in the best interest of the patient, provider organizations are sensitive to the competitive implications of sharing data and may pursue such sharing in a strategic way.24 A common scenario is when hospitals choose to strategically affiliate with select ambulatory providers and exclusively exchange information with them. This should facilitate better care coordination for patients shared by the hospital and those providers but can also benefit the hospital by increasing the referrals from those providers. While there is little direct evidence quantifying the extent to which this type of strategic sharing takes place, there have been anecdotal reports as well as indirect findings that for-profit hospitals in competitive markets are less likely to share patient data.19,25

EHR vendor HIE networks exist when exchange occurs within a community of provider organizations that use an EHR from the same vendor. A subset of EHR vendors have made this capability available; EPIC’s CareEverywhere solution27 is the best-known example. Providers with an EPIC EHR are able to query for and retrieve summary of care records and other documents from any provider organization with EPIC that has activated this functionality. There are also multivendor efforts, such as CommonWell27 and the Sequoia Project’s Carequality collaborative,28 which are initiatives that seek to provide a common interoperability framework across a diverse set of stakeholders, including provider organizations with different EHR systems, in a similar fashion to HIE modules like CareEverywhere. To date, growth in these cross-vendor collaborations has been slow, and they have limited participation. While HIE networks that involve EHR vendors are likely to grow, it is difficult to predict how quickly because they are still in an early phase of development, and face nontechnical barriers such as patient consent policies that vary between providers and across states.

Community HIE networks—also referred to as health information organizations (HIOs) or regional health information organizations (RHIOs)—exist when provider organizations in a community, frequently state-level organizations that were funded through HITECH grants,14 set up the technical infrastructure and governance approach to engage in HIE to improve patient care. In contrast to enterprise or vendor HIE networks that have pursued HIE in ways that appear strategically beneficial, the only restriction on participation in community and state HIE networks is usually geography because they view information exchange as a public good. Seventyone percent of hospital service areas (HSAs) are covered by at least 1 of the 106 operational HIOs, with 309,793 clinicians (licensed prescribers) participating in those exchange networks. Even with early infusions of public and other grant-funding, community HIE networks have experienced significant challenges to sustained operation, and many have ceased operating.29

Thus, for any given provider organization, available HIE networks are primarily shaped by 3 factors:

1. Geographic location, which determines the available community and state HIE networks (as well as other basic information technology and connectivity infrastructure); providers located outside the service areas covered by an operational HIE have little incentive to participate because they do not connect them to providers with whom they share patients. Providers in rural areas may simply not have the needed infrastructure to pursue HIE.

2. Type of organization to which they belong, which determines the available enterprise HIE networks; providers who are not members of large health systems may be excluded from participation in these types of networks.

3. EHR vendor, which determines whether they have access to an EHR vendor HIE network.

ONGOING CHALLENGES

Despite agreement about the substantial potential of HIE to reduce costs and increase the quality of care delivered across a broad range of providers, HIE progress has been slow. While HITECH has successfully increased EHR adoption in hospitals and ambulatory practices,30 HIE has lagged. This is largely because many complex, intertwined barriers must be addressed for HIE to be widespread.

Lack of a Defined Goal

The cost and complexity associated with the exchange of a single type of data (eg, medications) is substantially less than the cost and complexity of sharing complete patient records. There has been little industry consensus on the target goal—do we need to enable sharing of complete patient records across all providers, or will summary of care records suffice? If the latter, as is the focus of the current MU criteria, what types of information should be included in a summary of care record, and should content and/or structure vary depending on the type of care transition? While the MU criteria require the exchange of a summary of care record with defined data fields, it remains unclear whether this is the end state or whether we should continue to push towards broad-based sharing of all patient data as structured elements. Without a clear picture of the ideal end state, there has been significant heterogeneity in the development of HIE capabilities across providers and vendors, and difficulty coordinating efforts to continue to advance towards a nationwide approach. Addressing this issue also requires progress to define HIE usability, that is, how information from external organizations should be presented and integrated into clinical workflow and clinical decisions. Currently, where HIE is occurring and clinicians are receiving summary of care records, they find them long, cluttered, and difficult to locate key information.

Numerous, Complex Barriers Spanning Multiple Stakeholders

In the context of any individual HIE effort, even after the goal is defined, there are a myriad of challenges. In a recent survey of HIO efforts, many identified the following barriers as substantially impeding their development: establishing a sustainable business model, lack of funding, integration of HIE into provider workflow, limitations of current data standards, and working with governmental policy and mandates.30 What is notable about this list is that the barriers span an array of areas, including financial incentives and identifying a sustainable business model, technical barriers such as working within the limitations of data standards, and regulatory issues such as state laws that govern the requirements for patient consent to exchange personal health information. Overcoming any of these issues is challenging, but trying to tackle all of them simultaneously clearly reveals why progress has been slow. Further, resolving many of the issues involve different groups of stakeholders. For example, implementing appropriate patient consent procedures can require engaging with and harmonizing the regulations of multiple states, as well as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and regulations specific to substance abuse data.

Weak or Misaligned Incentives

Among the top barriers to HIE efforts are those related to funding and lack of a sustainable business model. This reflects the fact that economic incentives in the current market have not promoted provider engagement in HIE. Traditional fee-for-service payment structures do not reward providers for avoiding duplicative care.31 Further, hospitals perceive patient data as a “key strategic asset, tying physicians and patients to their organization,”24 and are reluctant to share data with competitors. Compounding the problem is that EHR vendors have a business interest in using HIE as a lever to increase revenue. In the short-term, they can charge high fees for interfaces and other HIE-related functionality. In the long-run, vendors may try to influence provider choice of system by making it difficult to engage in cross-vendor exchange.32 Information blocking—when providers or vendors knowingly interfere with HIE33—reflects not only weak incentives, but perverse incentives. While not all providers and vendors experience perverse incentives, the combination of weak and perverse incentives suggests the need to strengthen incentives, so that both types of stakeholders are motivated to tackle the barriers to HIE development. Key to strengthening incentives are payers, who are thought to be the largest beneficiaries of HIE. Payers have been reluctant to make significant investments in HIE without a more active voice in its implementation,34 but a shift to value-based payment may increase their engagement.

THE PATH FORWARD

Despite the continued challenges to nationwide HIE, several policy and technology developments show promise. Stage 3 meaningful use criteria continue to build on previous stages in increasing HIE requirements, raising the threshold for electronic exchange and EHR integration of summary of care documentation in patient transitions. The recently released Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) proposed rule replaces stage 3 meaningful use for Medicare-eligible providers with advancing care information (ACI), which accounts for 25% of a provider’s overall incentive reimbursement and includes multiple HIE criteria for providers to report as part of the base and performance score, and follows a very similar framework to stage 3 MU with its criteria regarding HIE.35 While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has not publicly declared that stage 3 MU will be replaced by ACI for hospitals and Medicaid providers, it is likely it will align those programs with the newly announced Medicare incentives.

MACRA also included changes to the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) EHR certification program in an attempt to further encourage HIE. Vendors and providers must attest that they do not engage in information blocking and will cooperate with the Office’s surveillance programs to that effect. They also must attest that, to the greatest degree possible, their EHR systems allow for bi-directional interoperability with other providers, including those with different EHR vendors, and timely access for patients to view, download, and transmit their health data. In addition, there are emerging federal efforts to pursue a more standardized approach to patient matching and harmonize consent policies across states. These types of new policy initiatives indicate a continued interest in prioritizing HIE and interoperability.21

New technologies may also help spur HIE progress. The newest policy initiatives from CMS, including stage 3 MU and MACRA, have looked to incentivize the creation of application program interfaces (APIs), a set of publicly available tools from EHR vendors to allow developers to build applications that can directly interface with, and retrieve data from, their EHRs. While most patient access to electronic health data to date has been accomplished via patient portals, open APIs would enable developers to build an array of programs for consumers to view, download, and transmit their health data.

Even more promising is the development of the newest Health Level 7 data transmission standard, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), which promises to dramatically simplify the technical aspects of interoperability. FHIR utilizes a human-readable, easy to implement modular “resources” standard that may alleviate many technical challenges that come with implementation of an HIE system, enabling cheaper and simpler interoperability.36 A consortium of EHR vendors are working together to test these standards.28 The new FHIR standards also work in conjunction with APIs to allow easier development of consumer-facing applications37 that may empower patients to take ownership of their health data.

CONCLUSION

While HIE holds great promise to reduce the cost and improve the quality of care, progress towards a nationally interoperable health system has been slow. Simply defining HIE and what types of HIE are needed in different clinical scenarios has proven challenging. The additional challenges to implementing HIE in complex technology, legal/regulatory, governance, and incentive environment are not without solutions. Continued policy interventions, private sector collaborations, and new technologies may hold the keys to realizing the vast potential of electronic HIE.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1130-1139. PubMed

2. Finnell JT, Overhage JM, Dexter PR, Perkins SM, Lane KA, McDonald CJ. Community clinical data exchange for emergency medicine patients. Paper presented at: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2003. PubMed

3. Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care-a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064-1071. PubMed

4. Franczak MJ, Klein M, Raslau F, Bergholte J, Mark LP, Ulmer JL. In emergency departments, radiologists’ access to EHRs may influence interpretations and medical management. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):800-806. PubMed

5. Shapiro JS, Kannry J, Kushniruk AW, Kuperman G; New York Clinical Information Exchange (NYCLIX) Clinical Advisory Subcommittee. Emergency physicians’ perceptions of health information exchange. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(6):700-705. PubMed

6. Shapiro JS, Kannry J, Lipton M, et al. Approaches to patient health information exchange and their impact on emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(4):426-432. PubMed

7. Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med.. 2004;79(2):186-194. PubMed

8. Kaelber DC, Bates DW. Health information exchange and patient safety. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40(suppl 6):S40-S45. PubMed

9. Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. MIssing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA. 2005;293(5):565-571. PubMed

10. Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381-386. PubMed

11. van Walraven C, Taljaard M, Bell CM, et al. A prospective cohort study found that provider and information continuity was low after patient discharge from hospital. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(9):1000-1010. PubMed

12. Walker J, Pan E, Johnston D, Adler-Milstein J, Bates DW, Middleton B. The value of health care information exchange and interoperability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005:(suppl)W5-10-W5-18. PubMed

13. Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Keeler EB. Costs and benefits of health information technology. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2006;132:1-71. PubMed

14. Blumenthal D. Launching HITECH. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):382-385. PubMed

15. Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):501-504. PubMed

16. Kuperman G, McGowan J. Potential unintended consequences of health information exchange. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(12):1663-1666. PubMed

17. Mathematica Policy Research and Harvard School of Public Health. DesRoches CM, Painter MW, Jha AK, eds. Health Information Technology in the United States, 2015: Transition to a Post-HITECH World (Executive Summary). September 18, 2015. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2015.

18. O’Malley AS, Anglin G, Bond AM, Cunningham PJ, Stark LB, Yee T. Greenville & Spartanburg: Surging Hospital Employment of Physicians Poses Opportunities and Challenges. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC); February 2011. 6.

19. Katz A, Bond AM, Carrier E, Docteur E, Quach CW, Yee T. Cleveland Hospital Systems Expand Despite Weak Economy. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC); September 2010. 2.

20. Grossman JM, Bodenheimer TS, McKenzie K. Hospital-physician portals: the role of competition in driving clinical data exchange. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(6):1629-1636. PubMed

21. De Salvo KB, Galvez E. Connecting Health and Care for the Nation A Shared Nationwide Interoperability Roadmap - Version 1.0. In: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ed 2015. https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/electronic-health-and-medical-records/interoperability-electronic-health-and-medical-records/connecting-health-care-nation-shared-nationwide-interoperability-roadmap-version-10/. Accessed September 3, 2016.