User login

Psychiatry can promote growth amid chronic illness

Promoting resilience, benefit finding, and post-traumatic growth help patients and families cope well with chronic illness. A resilient family has good problem-solving skills and communication, and a shared belief system (Fam Process. 2003; 42:1-18). Benefit finding coexists with feelings of burden, grief, and loss, and post-traumatic growth can occur despite grief and loss. Convening family meetings, for example, is a way to provide a therapeutic space for families and an opportunity to reflect on ways that chronic illness has affected the family, both negatively and positively.

What is coping well?

Resilient families cope well by identifying and solving illness-related problems, communicating about symptoms, negotiating role changes, and developing new interests as a family and new ways of emotionally being together. In addition, resilient families are able to adapt or change their life goals or health behaviors, such as improving diet, increasing exercise, and stopping smoking. A family member may work fewer hours, for example, and older children may give up some childhood activities to take on caregiving responsibilities.

Families do not usually think about how they cope; they just get along the best they can. Families may not consider how each family member’s individual coping style meshes with the coping styles of other family members. Illness management often is punctuated by crises where change happens quickly, without the family having time to deliberate on what coping styles might work best. Family changes can become fixed, therefore, not by choice, but by happenstance.

The initial stage of coping is “assimilative.” This is when the impact of the illness is being understood and absorbed. Emotional coping occurs when distress is highest, for example, at the beginning of an illness – when uncertainty exists about the diagnosis. Another characteristic of emotional coping is that it is characterized by attempts to regulate negative emotions. For example, family members may blame themselves or others, engage in wishful thinking, or become avoidant.

At later stages of illness, coping becomes “accommodative” after attempts to change or cure the illness have been found to be ineffective. Emotional coping can then be replaced with a problem-based coping style, allowing a stressor to be discussed and a solution chosen from several alternatives. Reflective coping, a related concept, is the ability to generate and consider coping options, and to recognize the usefulness of a particular coping strategy in a particular situation.

Psychiatric imperatives

While providing psychotherapy with these couples, it is helpful to:

• Help families differentiate between emotional difficulties such as “I am the primary caregiver, and I feel overburdened,” and more general practical problems, such as “I am happy to be the primary caregiver, but I need some extra help.”

• Describe coping to the family. Coping is a dynamic process, and coping styles change over time. Each person copes in their own way, depending on their experiences of illness and expectations of living with illness. In a family, the experiences and behaviors of all the individuals influence the way the family unit functions as a whole.

• Promote a balance between acceptance and change.

• Encourage the family to talk about their experience with others who are experiencing the same stressors.

• Give the family a handout that outlines different coping styles to get the discussion started.

• Provide a therapeutic space for family members to think together about how they want to cope and what coping well means to their family.

Developing dyadic coping

When dyadic coping takes place, couples cope as a single entity. Dyadic coping research is relatively new; most studies have been conducted in the past 15 years. Couples who use positive dyadic coping employ joint problem solving, joint information seeking, sharing of feelings, mutual commitment, and relaxing together. Meanwhile, couples who use negative dyadic coping hide concerns from each other and avoid shared discussion. A systemic review of dyadic coping in couples with cancer found that couples using positive dyadic coping styles experienced higher relationship functioning (Br J Health Psychol. 2015 Feb;20[1]:85-114).

Couples with good dyadic coping view the illness as “our problem.” This approach necessitates a shared understanding of the illness. The couple usually has prior experience working together as a team, for example, parenting and dividing roles within the house. They are able to relax together and provide emotional support, such as mutual calming and expressions of solidarity. Talking together about one’s worries and needs allows couples to share the experience more adequately. Dyadic coping is reflected in the amount of “we” talk.

The person in the family who copes “best” may provide the model for developing the family coping style. In a study of 66 couples faced with the stress of forced relocation, nearly all the couples adapted to the stress “as a couple,” rather than “as individuals” (Fam Process. 1991 Sep;30[3]:347-61). At the 2-year follow-up, each husband and wife developed similar coping styles, with one individual’s coping ability driving the adjustment of his or her partner. The need to adjust together or to adapt as a couple lessened the stress of relocation. Adaptation occurred through the development of shared meaning of the relocation that emerged from conversation within the couples. In other words, the couple developed a shared worldview. The coping style of the person who coped best was the strongest predictor of adjustment for both members of the couple. For most couples, the style of the person who coped best dominated.

Questions to ask during therapy

While working with these couples, assess their motivation to develop dyadic coping, by asking:

• “Do either of you feel that the patient should do this alone?” If the answer is yes, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to move the couple to a dyadic coping style.

• “Do your efforts to work together result in greater conflict?”

• “How much do you want this to change?” This questions clarifies their motivation to work together.

• “When you think about problems related to your heart condition, to what extent do you view those as ‘our problem’ [shared by the patient and the spouse equally] or mainly as ‘your own problem?’ ”

• “When a problem related to your heart condition arises, to what extent do you and your partner work together to solve it?”

• “When you both talk about the illness, how much do you use ‘we-talk’?”

• “It is important that you both agree about what is causing the illness. Can I answer any questions that might help you reach this understanding?”

• “Are there times in the past where you have successfully solved difficult problems? How did you do that?”

• “How do you respond when your spouse becomes ill?”

• “What can your spouse do that will help you get better?”

• “Can you ask your spouse for help and support?”

• “Can you work on your spouse’s health problem together?”

‘Benefit finding’ and PTG

Benefit finding emerges later in the adjustment to chronic illness. For example, caregivers may develop a greater appreciation of their own health and ability to enjoy their own pursuits. Family connectedness is a frequent source of meaning, and a critical aspect of well-being and benefit finding. Seven factors make up benefit finding: compassion/empathy, spiritual growth, mindfulness, family relations growth, lifestyle gains, personal growth, and new opportunities (Psychol Health. 2009 Apr;24[4]:373-93). Benefit finding is associated with higher marital adjustment, improved life satisfaction, and a more positive affect, especially at high levels of stress.

Post-traumatic growth, or PTG, refers to positive changes that occur after traumatic life events. People who experience PTG are transformed by their struggles with adversity. It is the struggle after the trauma, not the trauma itself, that produces PTG. In contrast to resilience, PTG refers to changes that go beyond pretrauma levels of adaptation and beyond benefit finding. Relational benefits in the aftermath of a cancer diagnosis are well recognized. An instrument used to assess these outcomes is called the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory, or PTGI (J Trauma Stress. 1996 Jul;9:455-71).

Interventions for couples coping with cancer resulted in improvements in communication, dyadic coping, quality of life, psychosocial distress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction (Psychooncology. 2014 Apr;23[7]:731-9). PTG may, however, be more apparent in patients than spouses.

Potential interventions

Promoting dyadic coping is effective if the couple wants to engage in intervention. According to one study, a partner-assisted emotional disclosure improved relationship functioning and intimacy (J Marital Fam Ther. 2012 Jun;38 Suppl 1:284-95). Couples therapy improves relational functioning in couples coping with cancer, at 1-year follow-up (Psychooncology. 2009 Mar;18[3]:276-83). Most important, as a first step, the couple must agree that they want to develop dyadic coping. The concept of individual versus dyadic coping may be novel for couples, and it is worth spending time on this review before offering couples intervention.

A psychoeducational program also can teach dyadic coping. The Resilient Partners discussion group developed in collaboration with the Multiple Sclerosis Society focused on developing couples’ strengths in coping with multiple sclerosis (Rolland, J., McPheters, J., and Carbonell, E., 2008). This multifamily group program is based on the Family Systems Illness Model, which integrates the demands of multiple sclerosis over time within a family developmental framework. In a comparison of a couple skills intervention with a psychoeducation program, women in the couple skills intervention benefited more in terms of their relationship functioning (Ann Behav Med. 2012 Apr;43[2]:239-52).

Dr. John S. Rolland’s Family Systems Illness (FSI) model provides a framework for the psychoeducation, assessment, and intervention with families dealing with chronic illness. This model, developed in clinical experience with more than 1,000 families, views families as valued partners and resources, and emphasizes resilience and growth. The FSI model takes into account the interaction of an illness with the individual’s development and the family’s development, the multigenerational ways of coping with illness, the family’s health/illness belief system, available resources, and relationships between health care providers.

The PTGI includes five domains: improved relationships, new possibilities for one’s life, a greater appreciation for life, a greater sense of personal strength, and spiritual development. Several family oriented themes within the PTGI can be used by the psychiatrist to inquire about positive change. These themes are:

• Knowing that I can count on people in times of trouble.

• A sense of closeness with others.

• Having compassion for others.

• Putting effort into my relationships.

• I learned a great deal about how wonderful people are.

• I accept needing others.

To promote PTG, the psychiatrists can listen for accounts of the experience of growth, label the experience, decide when the patient is ready for more focused questioning, and recognize that a life narrative including the aftermath of a trauma has value. In order to get the patient to recognize PTG, the psychiatrist can state and ask: “You may have heard people say that they have found some benefit in their struggle with trauma. Given what has happened to you, do you think that is possible?” Another exchange might flow like this: “You mentioned last time that you noticed that you and your wife have grown closer since this happened. Can you tell me more about this closeness. What is it about this struggle that has produced this closeness?”

Conclusion

Strengths, resilience, and post-traumatic growth are distinct constructs that share conceptual overlap. Using these constructs, the psychiatrist can help the patients and their families move forward. At the time of diagnosis/trauma/bereavement, family and couple interventions provide support, education, and symptom management. Specific psychoeducational interventions or family therapy can be used if needed. As the illness progresses and the family moves from an assimilative stance to an accommodative stance, and as problem-solving moves from emotional problem solving to reflective problem solving, the possibility of benefit finding and PTG emerge. Most importantly, the psychiatrist can provide the family with a therapeutic space to consider their coping styles, and offer the family a path forward through discussion of dyadic coping and family growth.

Further reading

1. Tedeschi and Kilmer, “Assessing Strengths, Resilience, and Growth to Guide Clinical Interventions,” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36(3), p. 230-7.

2. Heru A.M., “Working With Families in Medical Settings,” (New York: Routledge), 2013.

3. Rolland J.S. “Families, Illness, & Disability: An Integrative Treatment Model,” (New York: Basic Books), 1994. New edition in press.

Thank you to Dr. Jennifer Caspari for assisting with resources for this article.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Denver, Aurora. She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Promoting resilience, benefit finding, and post-traumatic growth help patients and families cope well with chronic illness. A resilient family has good problem-solving skills and communication, and a shared belief system (Fam Process. 2003; 42:1-18). Benefit finding coexists with feelings of burden, grief, and loss, and post-traumatic growth can occur despite grief and loss. Convening family meetings, for example, is a way to provide a therapeutic space for families and an opportunity to reflect on ways that chronic illness has affected the family, both negatively and positively.

What is coping well?

Resilient families cope well by identifying and solving illness-related problems, communicating about symptoms, negotiating role changes, and developing new interests as a family and new ways of emotionally being together. In addition, resilient families are able to adapt or change their life goals or health behaviors, such as improving diet, increasing exercise, and stopping smoking. A family member may work fewer hours, for example, and older children may give up some childhood activities to take on caregiving responsibilities.

Families do not usually think about how they cope; they just get along the best they can. Families may not consider how each family member’s individual coping style meshes with the coping styles of other family members. Illness management often is punctuated by crises where change happens quickly, without the family having time to deliberate on what coping styles might work best. Family changes can become fixed, therefore, not by choice, but by happenstance.

The initial stage of coping is “assimilative.” This is when the impact of the illness is being understood and absorbed. Emotional coping occurs when distress is highest, for example, at the beginning of an illness – when uncertainty exists about the diagnosis. Another characteristic of emotional coping is that it is characterized by attempts to regulate negative emotions. For example, family members may blame themselves or others, engage in wishful thinking, or become avoidant.

At later stages of illness, coping becomes “accommodative” after attempts to change or cure the illness have been found to be ineffective. Emotional coping can then be replaced with a problem-based coping style, allowing a stressor to be discussed and a solution chosen from several alternatives. Reflective coping, a related concept, is the ability to generate and consider coping options, and to recognize the usefulness of a particular coping strategy in a particular situation.

Psychiatric imperatives

While providing psychotherapy with these couples, it is helpful to:

• Help families differentiate between emotional difficulties such as “I am the primary caregiver, and I feel overburdened,” and more general practical problems, such as “I am happy to be the primary caregiver, but I need some extra help.”

• Describe coping to the family. Coping is a dynamic process, and coping styles change over time. Each person copes in their own way, depending on their experiences of illness and expectations of living with illness. In a family, the experiences and behaviors of all the individuals influence the way the family unit functions as a whole.

• Promote a balance between acceptance and change.

• Encourage the family to talk about their experience with others who are experiencing the same stressors.

• Give the family a handout that outlines different coping styles to get the discussion started.

• Provide a therapeutic space for family members to think together about how they want to cope and what coping well means to their family.

Developing dyadic coping

When dyadic coping takes place, couples cope as a single entity. Dyadic coping research is relatively new; most studies have been conducted in the past 15 years. Couples who use positive dyadic coping employ joint problem solving, joint information seeking, sharing of feelings, mutual commitment, and relaxing together. Meanwhile, couples who use negative dyadic coping hide concerns from each other and avoid shared discussion. A systemic review of dyadic coping in couples with cancer found that couples using positive dyadic coping styles experienced higher relationship functioning (Br J Health Psychol. 2015 Feb;20[1]:85-114).

Couples with good dyadic coping view the illness as “our problem.” This approach necessitates a shared understanding of the illness. The couple usually has prior experience working together as a team, for example, parenting and dividing roles within the house. They are able to relax together and provide emotional support, such as mutual calming and expressions of solidarity. Talking together about one’s worries and needs allows couples to share the experience more adequately. Dyadic coping is reflected in the amount of “we” talk.

The person in the family who copes “best” may provide the model for developing the family coping style. In a study of 66 couples faced with the stress of forced relocation, nearly all the couples adapted to the stress “as a couple,” rather than “as individuals” (Fam Process. 1991 Sep;30[3]:347-61). At the 2-year follow-up, each husband and wife developed similar coping styles, with one individual’s coping ability driving the adjustment of his or her partner. The need to adjust together or to adapt as a couple lessened the stress of relocation. Adaptation occurred through the development of shared meaning of the relocation that emerged from conversation within the couples. In other words, the couple developed a shared worldview. The coping style of the person who coped best was the strongest predictor of adjustment for both members of the couple. For most couples, the style of the person who coped best dominated.

Questions to ask during therapy

While working with these couples, assess their motivation to develop dyadic coping, by asking:

• “Do either of you feel that the patient should do this alone?” If the answer is yes, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to move the couple to a dyadic coping style.

• “Do your efforts to work together result in greater conflict?”

• “How much do you want this to change?” This questions clarifies their motivation to work together.

• “When you think about problems related to your heart condition, to what extent do you view those as ‘our problem’ [shared by the patient and the spouse equally] or mainly as ‘your own problem?’ ”

• “When a problem related to your heart condition arises, to what extent do you and your partner work together to solve it?”

• “When you both talk about the illness, how much do you use ‘we-talk’?”

• “It is important that you both agree about what is causing the illness. Can I answer any questions that might help you reach this understanding?”

• “Are there times in the past where you have successfully solved difficult problems? How did you do that?”

• “How do you respond when your spouse becomes ill?”

• “What can your spouse do that will help you get better?”

• “Can you ask your spouse for help and support?”

• “Can you work on your spouse’s health problem together?”

‘Benefit finding’ and PTG

Benefit finding emerges later in the adjustment to chronic illness. For example, caregivers may develop a greater appreciation of their own health and ability to enjoy their own pursuits. Family connectedness is a frequent source of meaning, and a critical aspect of well-being and benefit finding. Seven factors make up benefit finding: compassion/empathy, spiritual growth, mindfulness, family relations growth, lifestyle gains, personal growth, and new opportunities (Psychol Health. 2009 Apr;24[4]:373-93). Benefit finding is associated with higher marital adjustment, improved life satisfaction, and a more positive affect, especially at high levels of stress.

Post-traumatic growth, or PTG, refers to positive changes that occur after traumatic life events. People who experience PTG are transformed by their struggles with adversity. It is the struggle after the trauma, not the trauma itself, that produces PTG. In contrast to resilience, PTG refers to changes that go beyond pretrauma levels of adaptation and beyond benefit finding. Relational benefits in the aftermath of a cancer diagnosis are well recognized. An instrument used to assess these outcomes is called the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory, or PTGI (J Trauma Stress. 1996 Jul;9:455-71).

Interventions for couples coping with cancer resulted in improvements in communication, dyadic coping, quality of life, psychosocial distress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction (Psychooncology. 2014 Apr;23[7]:731-9). PTG may, however, be more apparent in patients than spouses.

Potential interventions

Promoting dyadic coping is effective if the couple wants to engage in intervention. According to one study, a partner-assisted emotional disclosure improved relationship functioning and intimacy (J Marital Fam Ther. 2012 Jun;38 Suppl 1:284-95). Couples therapy improves relational functioning in couples coping with cancer, at 1-year follow-up (Psychooncology. 2009 Mar;18[3]:276-83). Most important, as a first step, the couple must agree that they want to develop dyadic coping. The concept of individual versus dyadic coping may be novel for couples, and it is worth spending time on this review before offering couples intervention.

A psychoeducational program also can teach dyadic coping. The Resilient Partners discussion group developed in collaboration with the Multiple Sclerosis Society focused on developing couples’ strengths in coping with multiple sclerosis (Rolland, J., McPheters, J., and Carbonell, E., 2008). This multifamily group program is based on the Family Systems Illness Model, which integrates the demands of multiple sclerosis over time within a family developmental framework. In a comparison of a couple skills intervention with a psychoeducation program, women in the couple skills intervention benefited more in terms of their relationship functioning (Ann Behav Med. 2012 Apr;43[2]:239-52).

Dr. John S. Rolland’s Family Systems Illness (FSI) model provides a framework for the psychoeducation, assessment, and intervention with families dealing with chronic illness. This model, developed in clinical experience with more than 1,000 families, views families as valued partners and resources, and emphasizes resilience and growth. The FSI model takes into account the interaction of an illness with the individual’s development and the family’s development, the multigenerational ways of coping with illness, the family’s health/illness belief system, available resources, and relationships between health care providers.

The PTGI includes five domains: improved relationships, new possibilities for one’s life, a greater appreciation for life, a greater sense of personal strength, and spiritual development. Several family oriented themes within the PTGI can be used by the psychiatrist to inquire about positive change. These themes are:

• Knowing that I can count on people in times of trouble.

• A sense of closeness with others.

• Having compassion for others.

• Putting effort into my relationships.

• I learned a great deal about how wonderful people are.

• I accept needing others.

To promote PTG, the psychiatrists can listen for accounts of the experience of growth, label the experience, decide when the patient is ready for more focused questioning, and recognize that a life narrative including the aftermath of a trauma has value. In order to get the patient to recognize PTG, the psychiatrist can state and ask: “You may have heard people say that they have found some benefit in their struggle with trauma. Given what has happened to you, do you think that is possible?” Another exchange might flow like this: “You mentioned last time that you noticed that you and your wife have grown closer since this happened. Can you tell me more about this closeness. What is it about this struggle that has produced this closeness?”

Conclusion

Strengths, resilience, and post-traumatic growth are distinct constructs that share conceptual overlap. Using these constructs, the psychiatrist can help the patients and their families move forward. At the time of diagnosis/trauma/bereavement, family and couple interventions provide support, education, and symptom management. Specific psychoeducational interventions or family therapy can be used if needed. As the illness progresses and the family moves from an assimilative stance to an accommodative stance, and as problem-solving moves from emotional problem solving to reflective problem solving, the possibility of benefit finding and PTG emerge. Most importantly, the psychiatrist can provide the family with a therapeutic space to consider their coping styles, and offer the family a path forward through discussion of dyadic coping and family growth.

Further reading

1. Tedeschi and Kilmer, “Assessing Strengths, Resilience, and Growth to Guide Clinical Interventions,” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36(3), p. 230-7.

2. Heru A.M., “Working With Families in Medical Settings,” (New York: Routledge), 2013.

3. Rolland J.S. “Families, Illness, & Disability: An Integrative Treatment Model,” (New York: Basic Books), 1994. New edition in press.

Thank you to Dr. Jennifer Caspari for assisting with resources for this article.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Denver, Aurora. She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Promoting resilience, benefit finding, and post-traumatic growth help patients and families cope well with chronic illness. A resilient family has good problem-solving skills and communication, and a shared belief system (Fam Process. 2003; 42:1-18). Benefit finding coexists with feelings of burden, grief, and loss, and post-traumatic growth can occur despite grief and loss. Convening family meetings, for example, is a way to provide a therapeutic space for families and an opportunity to reflect on ways that chronic illness has affected the family, both negatively and positively.

What is coping well?

Resilient families cope well by identifying and solving illness-related problems, communicating about symptoms, negotiating role changes, and developing new interests as a family and new ways of emotionally being together. In addition, resilient families are able to adapt or change their life goals or health behaviors, such as improving diet, increasing exercise, and stopping smoking. A family member may work fewer hours, for example, and older children may give up some childhood activities to take on caregiving responsibilities.

Families do not usually think about how they cope; they just get along the best they can. Families may not consider how each family member’s individual coping style meshes with the coping styles of other family members. Illness management often is punctuated by crises where change happens quickly, without the family having time to deliberate on what coping styles might work best. Family changes can become fixed, therefore, not by choice, but by happenstance.

The initial stage of coping is “assimilative.” This is when the impact of the illness is being understood and absorbed. Emotional coping occurs when distress is highest, for example, at the beginning of an illness – when uncertainty exists about the diagnosis. Another characteristic of emotional coping is that it is characterized by attempts to regulate negative emotions. For example, family members may blame themselves or others, engage in wishful thinking, or become avoidant.

At later stages of illness, coping becomes “accommodative” after attempts to change or cure the illness have been found to be ineffective. Emotional coping can then be replaced with a problem-based coping style, allowing a stressor to be discussed and a solution chosen from several alternatives. Reflective coping, a related concept, is the ability to generate and consider coping options, and to recognize the usefulness of a particular coping strategy in a particular situation.

Psychiatric imperatives

While providing psychotherapy with these couples, it is helpful to:

• Help families differentiate between emotional difficulties such as “I am the primary caregiver, and I feel overburdened,” and more general practical problems, such as “I am happy to be the primary caregiver, but I need some extra help.”

• Describe coping to the family. Coping is a dynamic process, and coping styles change over time. Each person copes in their own way, depending on their experiences of illness and expectations of living with illness. In a family, the experiences and behaviors of all the individuals influence the way the family unit functions as a whole.

• Promote a balance between acceptance and change.

• Encourage the family to talk about their experience with others who are experiencing the same stressors.

• Give the family a handout that outlines different coping styles to get the discussion started.

• Provide a therapeutic space for family members to think together about how they want to cope and what coping well means to their family.

Developing dyadic coping

When dyadic coping takes place, couples cope as a single entity. Dyadic coping research is relatively new; most studies have been conducted in the past 15 years. Couples who use positive dyadic coping employ joint problem solving, joint information seeking, sharing of feelings, mutual commitment, and relaxing together. Meanwhile, couples who use negative dyadic coping hide concerns from each other and avoid shared discussion. A systemic review of dyadic coping in couples with cancer found that couples using positive dyadic coping styles experienced higher relationship functioning (Br J Health Psychol. 2015 Feb;20[1]:85-114).

Couples with good dyadic coping view the illness as “our problem.” This approach necessitates a shared understanding of the illness. The couple usually has prior experience working together as a team, for example, parenting and dividing roles within the house. They are able to relax together and provide emotional support, such as mutual calming and expressions of solidarity. Talking together about one’s worries and needs allows couples to share the experience more adequately. Dyadic coping is reflected in the amount of “we” talk.

The person in the family who copes “best” may provide the model for developing the family coping style. In a study of 66 couples faced with the stress of forced relocation, nearly all the couples adapted to the stress “as a couple,” rather than “as individuals” (Fam Process. 1991 Sep;30[3]:347-61). At the 2-year follow-up, each husband and wife developed similar coping styles, with one individual’s coping ability driving the adjustment of his or her partner. The need to adjust together or to adapt as a couple lessened the stress of relocation. Adaptation occurred through the development of shared meaning of the relocation that emerged from conversation within the couples. In other words, the couple developed a shared worldview. The coping style of the person who coped best was the strongest predictor of adjustment for both members of the couple. For most couples, the style of the person who coped best dominated.

Questions to ask during therapy

While working with these couples, assess their motivation to develop dyadic coping, by asking:

• “Do either of you feel that the patient should do this alone?” If the answer is yes, it will be difficult, if not impossible, to move the couple to a dyadic coping style.

• “Do your efforts to work together result in greater conflict?”

• “How much do you want this to change?” This questions clarifies their motivation to work together.

• “When you think about problems related to your heart condition, to what extent do you view those as ‘our problem’ [shared by the patient and the spouse equally] or mainly as ‘your own problem?’ ”

• “When a problem related to your heart condition arises, to what extent do you and your partner work together to solve it?”

• “When you both talk about the illness, how much do you use ‘we-talk’?”

• “It is important that you both agree about what is causing the illness. Can I answer any questions that might help you reach this understanding?”

• “Are there times in the past where you have successfully solved difficult problems? How did you do that?”

• “How do you respond when your spouse becomes ill?”

• “What can your spouse do that will help you get better?”

• “Can you ask your spouse for help and support?”

• “Can you work on your spouse’s health problem together?”

‘Benefit finding’ and PTG

Benefit finding emerges later in the adjustment to chronic illness. For example, caregivers may develop a greater appreciation of their own health and ability to enjoy their own pursuits. Family connectedness is a frequent source of meaning, and a critical aspect of well-being and benefit finding. Seven factors make up benefit finding: compassion/empathy, spiritual growth, mindfulness, family relations growth, lifestyle gains, personal growth, and new opportunities (Psychol Health. 2009 Apr;24[4]:373-93). Benefit finding is associated with higher marital adjustment, improved life satisfaction, and a more positive affect, especially at high levels of stress.

Post-traumatic growth, or PTG, refers to positive changes that occur after traumatic life events. People who experience PTG are transformed by their struggles with adversity. It is the struggle after the trauma, not the trauma itself, that produces PTG. In contrast to resilience, PTG refers to changes that go beyond pretrauma levels of adaptation and beyond benefit finding. Relational benefits in the aftermath of a cancer diagnosis are well recognized. An instrument used to assess these outcomes is called the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory, or PTGI (J Trauma Stress. 1996 Jul;9:455-71).

Interventions for couples coping with cancer resulted in improvements in communication, dyadic coping, quality of life, psychosocial distress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction (Psychooncology. 2014 Apr;23[7]:731-9). PTG may, however, be more apparent in patients than spouses.

Potential interventions

Promoting dyadic coping is effective if the couple wants to engage in intervention. According to one study, a partner-assisted emotional disclosure improved relationship functioning and intimacy (J Marital Fam Ther. 2012 Jun;38 Suppl 1:284-95). Couples therapy improves relational functioning in couples coping with cancer, at 1-year follow-up (Psychooncology. 2009 Mar;18[3]:276-83). Most important, as a first step, the couple must agree that they want to develop dyadic coping. The concept of individual versus dyadic coping may be novel for couples, and it is worth spending time on this review before offering couples intervention.

A psychoeducational program also can teach dyadic coping. The Resilient Partners discussion group developed in collaboration with the Multiple Sclerosis Society focused on developing couples’ strengths in coping with multiple sclerosis (Rolland, J., McPheters, J., and Carbonell, E., 2008). This multifamily group program is based on the Family Systems Illness Model, which integrates the demands of multiple sclerosis over time within a family developmental framework. In a comparison of a couple skills intervention with a psychoeducation program, women in the couple skills intervention benefited more in terms of their relationship functioning (Ann Behav Med. 2012 Apr;43[2]:239-52).

Dr. John S. Rolland’s Family Systems Illness (FSI) model provides a framework for the psychoeducation, assessment, and intervention with families dealing with chronic illness. This model, developed in clinical experience with more than 1,000 families, views families as valued partners and resources, and emphasizes resilience and growth. The FSI model takes into account the interaction of an illness with the individual’s development and the family’s development, the multigenerational ways of coping with illness, the family’s health/illness belief system, available resources, and relationships between health care providers.

The PTGI includes five domains: improved relationships, new possibilities for one’s life, a greater appreciation for life, a greater sense of personal strength, and spiritual development. Several family oriented themes within the PTGI can be used by the psychiatrist to inquire about positive change. These themes are:

• Knowing that I can count on people in times of trouble.

• A sense of closeness with others.

• Having compassion for others.

• Putting effort into my relationships.

• I learned a great deal about how wonderful people are.

• I accept needing others.

To promote PTG, the psychiatrists can listen for accounts of the experience of growth, label the experience, decide when the patient is ready for more focused questioning, and recognize that a life narrative including the aftermath of a trauma has value. In order to get the patient to recognize PTG, the psychiatrist can state and ask: “You may have heard people say that they have found some benefit in their struggle with trauma. Given what has happened to you, do you think that is possible?” Another exchange might flow like this: “You mentioned last time that you noticed that you and your wife have grown closer since this happened. Can you tell me more about this closeness. What is it about this struggle that has produced this closeness?”

Conclusion

Strengths, resilience, and post-traumatic growth are distinct constructs that share conceptual overlap. Using these constructs, the psychiatrist can help the patients and their families move forward. At the time of diagnosis/trauma/bereavement, family and couple interventions provide support, education, and symptom management. Specific psychoeducational interventions or family therapy can be used if needed. As the illness progresses and the family moves from an assimilative stance to an accommodative stance, and as problem-solving moves from emotional problem solving to reflective problem solving, the possibility of benefit finding and PTG emerge. Most importantly, the psychiatrist can provide the family with a therapeutic space to consider their coping styles, and offer the family a path forward through discussion of dyadic coping and family growth.

Further reading

1. Tedeschi and Kilmer, “Assessing Strengths, Resilience, and Growth to Guide Clinical Interventions,” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36(3), p. 230-7.

2. Heru A.M., “Working With Families in Medical Settings,” (New York: Routledge), 2013.

3. Rolland J.S. “Families, Illness, & Disability: An Integrative Treatment Model,” (New York: Basic Books), 1994. New edition in press.

Thank you to Dr. Jennifer Caspari for assisting with resources for this article.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Denver, Aurora. She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus (LS) is a benign, uncommon, self-limited, linear inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects children up to 15 years of age, most commonly around 2 to 3 years of age, and is seen more frequently in girls.1 It presents with a sudden eruption of asymptomatic small, flat-topped, lichenoid, scaly papules in a linear array on a single extremity. The lesions may be erythematous, flesh colored, or hypopigmented.1,2 Multiple lesions appear over days to weeks and coalesce into linear plaques in a continuous or interrupted pattern along the lines of Blaschko, indicating possible somatic mosaicism.1 Although typically asymptomatic, it may be pruritic. Most cases spontaneously resolve within 1 year.3 Recurrences are unusual. Digital involvement may result in onycholysis, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and nail loss.1 The underlying cause of LS may be an abnormal immunologic reaction or genetic predisposition that is precipitated by some trigger such as a viral infection, trauma, hypersensitivity reaction, vaccine, seasonal variation, medication, or pregnancy.1,2 An association with atopy has been described. Treatment is not necessary but options include topical steroids, topical retinoids, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.2

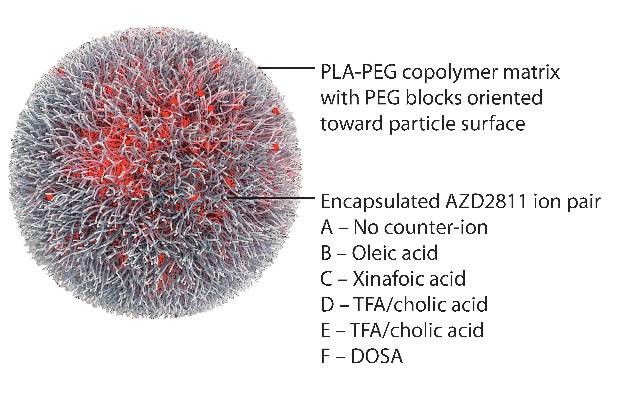

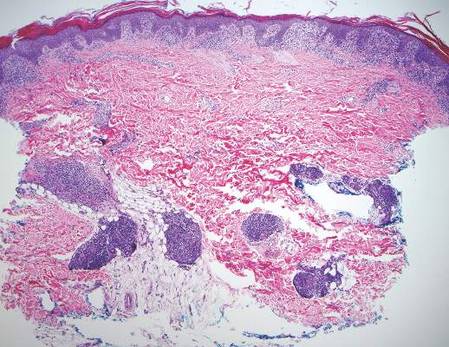

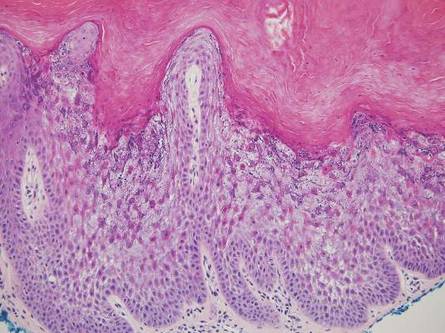

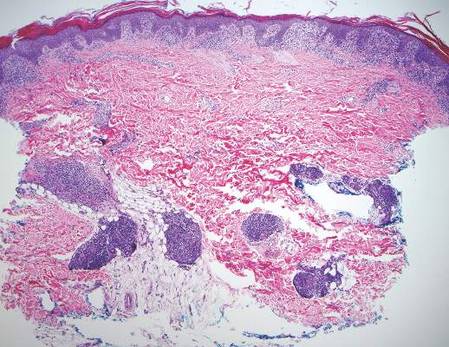

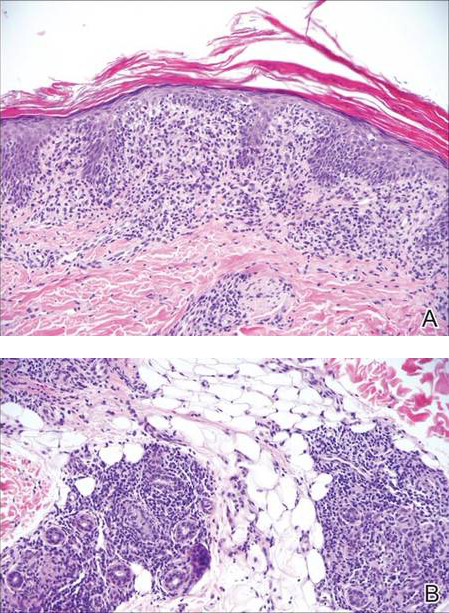

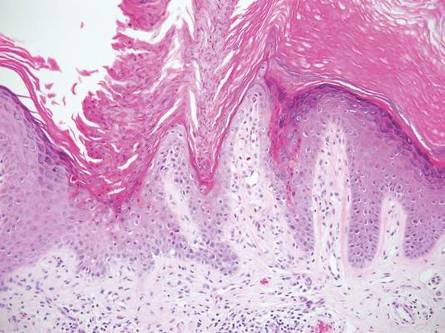

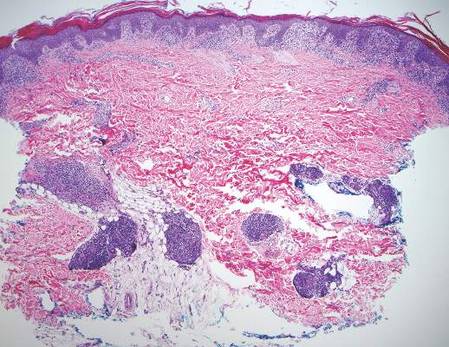

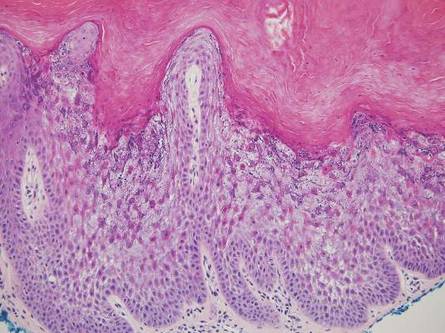

Histologically, findings in LS are somewhat variable but typically show a combination of spongiotic and lichenoid interface dermatitis with a perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Epidermal changes include intercellular and intracellular edema, focal spongiosis, lymphocytic exocytosis, parakeratosis, patchy hyperkeratosis, and keratinocyte necrosis (Figure 2A).1,3 The epidermis is normal or slightly acanthotic, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes can be found in the granular and horny layers or at the dermoepidermal junction.2 The lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the superficial and deep dermis surrounds vascular plexuses and cutaneous adnexa such as eccrine glands and hair follicles.1 Perivascular lymphoid aggregates and eccrine coil involvement are particularly distinctive of LS (Figure 2B).4 Pigment incontinence also may be seen.

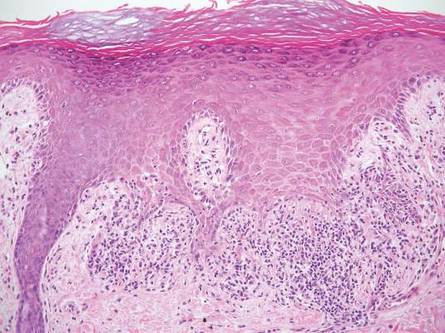

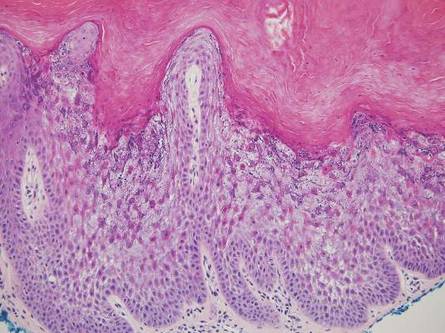

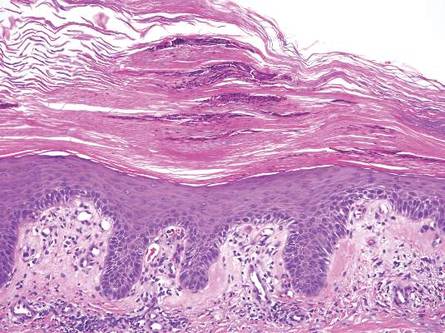

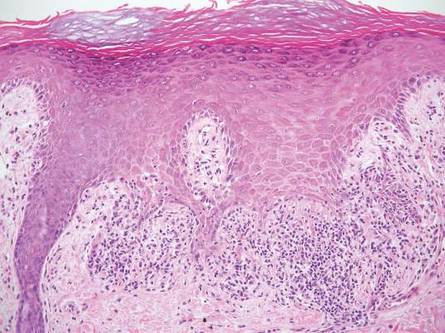

Another condition that distributes linearly along the lines of Blaschko is linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK). Similar to LS, histology shows hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis.5 However, EHK shows epidermolysis, acantholysis, and perinuclear vacuolization in spinous and granular layers (Figure 3).5 The lack of perivascular and periadnexal inflammation also can help differentiate EHK from LS.

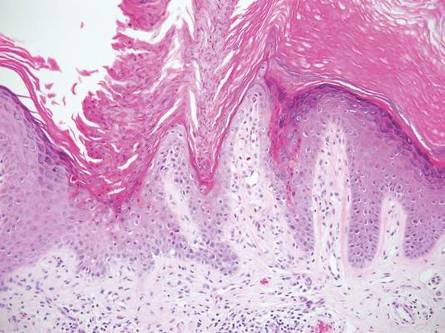

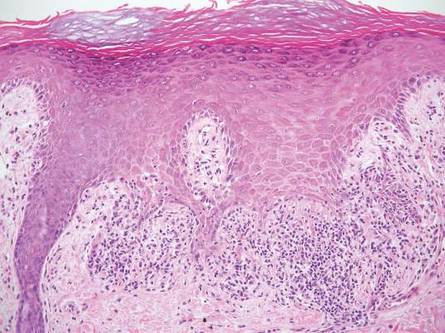

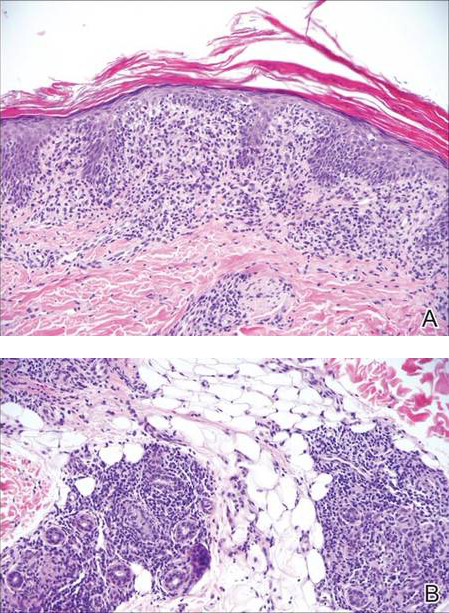

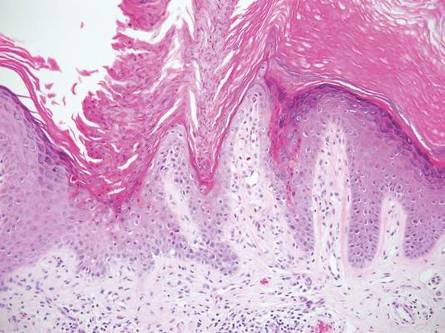

Linear lichen planus (LLP), similar to LS, histologically shows a lichenoid lymphocytic bandlike infiltrate obscuring the dermoepidermal junction, vacuolization of the basal cell layer, and pigment incontinence.1,2 Although LS and LLP can have histologic overlap, the absence of adnexal or perieccrine lymphocytic inflammation can help distinguish the two.3 The histopathologic changes of intercellular edema or mild spongiosis, exocytosis, and parakeratosis present in LS also are typically absent in LLP. Linear lichen planus characteristically consists of wedge-shaped hypergranulosis and irregular acanthosis with saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 4).2 In addition, lobular eosinophilic deposits known as cytoid or Civatte bodies representing degenerated keratinocytes can be visualized at the dermoepidermal junction in LLP.2 Immunofluorescence will highlight Civatte bodies with IgM, IgG, and C3, also helping to differentiate these 2 conditions.1

Linear porokeratosis can be mistaken for the linear lesion of LS. Both entities may reveal perivascular lymphocytes in the dermis, and porokeratosis can be lichenoid in the central portion of the lesion.6 However, porokeratosis is unique in that it contains a cornoid lamella, characterized by a thin column of tightly packed parakeratotic cells extending from an invagination of the epidermis through the adjacent stratum corneum (Figure 5).6 Beneath the cornoid lamella, the granular layer is either absent or markedly attenuated, and pyknotic keratinocytes with perinuclear edema are present in the spinous layer.6 The epidermis in the central portion of the porokeratotic lesion may be normal, hyperplastic, or atrophic with effacement of rete ridges.

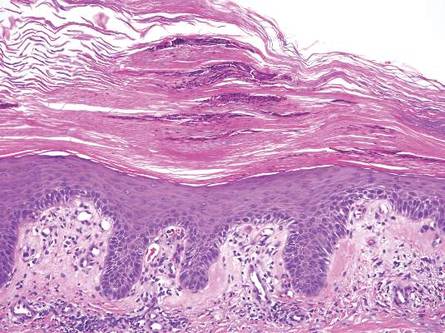

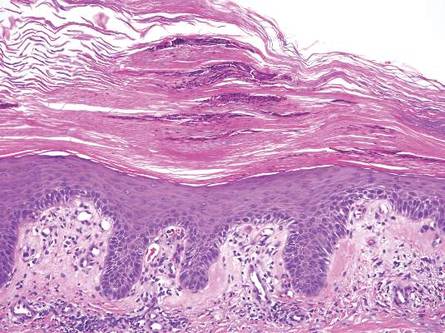

Similar to LS, linear psoriasis follows lines of Blaschko clinically. However, it is distinguished by its characteristic psoriatic epidermal changes as well as its lack of lichenoid or perieccrine inflammation.3 Typical findings in linear psoriasis include hyperkeratosis, confluent parakeratosis with entrapped neutrophilic microabscesses, acanthosis with regular elongation of rete ridges, intraepidermal neutrophils, thinned suprapapillary plates, dilated capillaries in the tips of the dermal papillae, and a chronic dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 6).4

- Wang WL, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011:219-258.

- Shiohara T, Kano Y. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:183-202.

- Zhang Y, McNutt NS. Lichen striatus. histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of 37 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:65-71.

- Johnson M, Walker D, Galloway W, et al. Interface dermatitis along Blaschko’s lines. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:950-954.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell C. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1795-1815.

Lichen striatus (LS) is a benign, uncommon, self-limited, linear inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects children up to 15 years of age, most commonly around 2 to 3 years of age, and is seen more frequently in girls.1 It presents with a sudden eruption of asymptomatic small, flat-topped, lichenoid, scaly papules in a linear array on a single extremity. The lesions may be erythematous, flesh colored, or hypopigmented.1,2 Multiple lesions appear over days to weeks and coalesce into linear plaques in a continuous or interrupted pattern along the lines of Blaschko, indicating possible somatic mosaicism.1 Although typically asymptomatic, it may be pruritic. Most cases spontaneously resolve within 1 year.3 Recurrences are unusual. Digital involvement may result in onycholysis, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and nail loss.1 The underlying cause of LS may be an abnormal immunologic reaction or genetic predisposition that is precipitated by some trigger such as a viral infection, trauma, hypersensitivity reaction, vaccine, seasonal variation, medication, or pregnancy.1,2 An association with atopy has been described. Treatment is not necessary but options include topical steroids, topical retinoids, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.2

Histologically, findings in LS are somewhat variable but typically show a combination of spongiotic and lichenoid interface dermatitis with a perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Epidermal changes include intercellular and intracellular edema, focal spongiosis, lymphocytic exocytosis, parakeratosis, patchy hyperkeratosis, and keratinocyte necrosis (Figure 2A).1,3 The epidermis is normal or slightly acanthotic, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes can be found in the granular and horny layers or at the dermoepidermal junction.2 The lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the superficial and deep dermis surrounds vascular plexuses and cutaneous adnexa such as eccrine glands and hair follicles.1 Perivascular lymphoid aggregates and eccrine coil involvement are particularly distinctive of LS (Figure 2B).4 Pigment incontinence also may be seen.

Another condition that distributes linearly along the lines of Blaschko is linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK). Similar to LS, histology shows hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis.5 However, EHK shows epidermolysis, acantholysis, and perinuclear vacuolization in spinous and granular layers (Figure 3).5 The lack of perivascular and periadnexal inflammation also can help differentiate EHK from LS.

Linear lichen planus (LLP), similar to LS, histologically shows a lichenoid lymphocytic bandlike infiltrate obscuring the dermoepidermal junction, vacuolization of the basal cell layer, and pigment incontinence.1,2 Although LS and LLP can have histologic overlap, the absence of adnexal or perieccrine lymphocytic inflammation can help distinguish the two.3 The histopathologic changes of intercellular edema or mild spongiosis, exocytosis, and parakeratosis present in LS also are typically absent in LLP. Linear lichen planus characteristically consists of wedge-shaped hypergranulosis and irregular acanthosis with saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 4).2 In addition, lobular eosinophilic deposits known as cytoid or Civatte bodies representing degenerated keratinocytes can be visualized at the dermoepidermal junction in LLP.2 Immunofluorescence will highlight Civatte bodies with IgM, IgG, and C3, also helping to differentiate these 2 conditions.1

Linear porokeratosis can be mistaken for the linear lesion of LS. Both entities may reveal perivascular lymphocytes in the dermis, and porokeratosis can be lichenoid in the central portion of the lesion.6 However, porokeratosis is unique in that it contains a cornoid lamella, characterized by a thin column of tightly packed parakeratotic cells extending from an invagination of the epidermis through the adjacent stratum corneum (Figure 5).6 Beneath the cornoid lamella, the granular layer is either absent or markedly attenuated, and pyknotic keratinocytes with perinuclear edema are present in the spinous layer.6 The epidermis in the central portion of the porokeratotic lesion may be normal, hyperplastic, or atrophic with effacement of rete ridges.

Similar to LS, linear psoriasis follows lines of Blaschko clinically. However, it is distinguished by its characteristic psoriatic epidermal changes as well as its lack of lichenoid or perieccrine inflammation.3 Typical findings in linear psoriasis include hyperkeratosis, confluent parakeratosis with entrapped neutrophilic microabscesses, acanthosis with regular elongation of rete ridges, intraepidermal neutrophils, thinned suprapapillary plates, dilated capillaries in the tips of the dermal papillae, and a chronic dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 6).4

Lichen striatus (LS) is a benign, uncommon, self-limited, linear inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects children up to 15 years of age, most commonly around 2 to 3 years of age, and is seen more frequently in girls.1 It presents with a sudden eruption of asymptomatic small, flat-topped, lichenoid, scaly papules in a linear array on a single extremity. The lesions may be erythematous, flesh colored, or hypopigmented.1,2 Multiple lesions appear over days to weeks and coalesce into linear plaques in a continuous or interrupted pattern along the lines of Blaschko, indicating possible somatic mosaicism.1 Although typically asymptomatic, it may be pruritic. Most cases spontaneously resolve within 1 year.3 Recurrences are unusual. Digital involvement may result in onycholysis, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and nail loss.1 The underlying cause of LS may be an abnormal immunologic reaction or genetic predisposition that is precipitated by some trigger such as a viral infection, trauma, hypersensitivity reaction, vaccine, seasonal variation, medication, or pregnancy.1,2 An association with atopy has been described. Treatment is not necessary but options include topical steroids, topical retinoids, and topical calcineurin inhibitors.2

Histologically, findings in LS are somewhat variable but typically show a combination of spongiotic and lichenoid interface dermatitis with a perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Epidermal changes include intercellular and intracellular edema, focal spongiosis, lymphocytic exocytosis, parakeratosis, patchy hyperkeratosis, and keratinocyte necrosis (Figure 2A).1,3 The epidermis is normal or slightly acanthotic, and dyskeratotic keratinocytes can be found in the granular and horny layers or at the dermoepidermal junction.2 The lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the superficial and deep dermis surrounds vascular plexuses and cutaneous adnexa such as eccrine glands and hair follicles.1 Perivascular lymphoid aggregates and eccrine coil involvement are particularly distinctive of LS (Figure 2B).4 Pigment incontinence also may be seen.

Another condition that distributes linearly along the lines of Blaschko is linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK). Similar to LS, histology shows hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis.5 However, EHK shows epidermolysis, acantholysis, and perinuclear vacuolization in spinous and granular layers (Figure 3).5 The lack of perivascular and periadnexal inflammation also can help differentiate EHK from LS.

Linear lichen planus (LLP), similar to LS, histologically shows a lichenoid lymphocytic bandlike infiltrate obscuring the dermoepidermal junction, vacuolization of the basal cell layer, and pigment incontinence.1,2 Although LS and LLP can have histologic overlap, the absence of adnexal or perieccrine lymphocytic inflammation can help distinguish the two.3 The histopathologic changes of intercellular edema or mild spongiosis, exocytosis, and parakeratosis present in LS also are typically absent in LLP. Linear lichen planus characteristically consists of wedge-shaped hypergranulosis and irregular acanthosis with saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 4).2 In addition, lobular eosinophilic deposits known as cytoid or Civatte bodies representing degenerated keratinocytes can be visualized at the dermoepidermal junction in LLP.2 Immunofluorescence will highlight Civatte bodies with IgM, IgG, and C3, also helping to differentiate these 2 conditions.1

Linear porokeratosis can be mistaken for the linear lesion of LS. Both entities may reveal perivascular lymphocytes in the dermis, and porokeratosis can be lichenoid in the central portion of the lesion.6 However, porokeratosis is unique in that it contains a cornoid lamella, characterized by a thin column of tightly packed parakeratotic cells extending from an invagination of the epidermis through the adjacent stratum corneum (Figure 5).6 Beneath the cornoid lamella, the granular layer is either absent or markedly attenuated, and pyknotic keratinocytes with perinuclear edema are present in the spinous layer.6 The epidermis in the central portion of the porokeratotic lesion may be normal, hyperplastic, or atrophic with effacement of rete ridges.

Similar to LS, linear psoriasis follows lines of Blaschko clinically. However, it is distinguished by its characteristic psoriatic epidermal changes as well as its lack of lichenoid or perieccrine inflammation.3 Typical findings in linear psoriasis include hyperkeratosis, confluent parakeratosis with entrapped neutrophilic microabscesses, acanthosis with regular elongation of rete ridges, intraepidermal neutrophils, thinned suprapapillary plates, dilated capillaries in the tips of the dermal papillae, and a chronic dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 6).4

- Wang WL, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011:219-258.

- Shiohara T, Kano Y. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:183-202.

- Zhang Y, McNutt NS. Lichen striatus. histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of 37 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:65-71.

- Johnson M, Walker D, Galloway W, et al. Interface dermatitis along Blaschko’s lines. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:950-954.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell C. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1795-1815.

- Wang WL, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. London, England: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011:219-258.

- Shiohara T, Kano Y. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:183-202.

- Zhang Y, McNutt NS. Lichen striatus. histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of 37 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:65-71.

- Johnson M, Walker D, Galloway W, et al. Interface dermatitis along Blaschko’s lines. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:950-954.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Requena L, Requena C, Cockerell C. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1795-1815.

Subcision: The benefits of a classic technique

We’re always working toward medical breakthroughs so we can provide the most effective treatments for our patients with cutting-edge technology; however, there is a lot to be said about the techniques that have paved the way for new medical devices.

For certain conditions, the efficacy of classic procedures often cannot be matched by their modern successors. Subcision for treatment of deep depressed scars, for example, is often a more effective option than microneedling and can produce results with less healing time and fewer treatments, and at a more cost-effective price.

Both subcision and microneedling improve the appearance of scars by creating wounds in an effort to break up scar tissue and trigger collagen regrowth. Microneedling involves the use of a microneedling pen with several small needles that glide across the skin at different depths and speeds. Subcision is achieved with one larger gauge needle that is injected into scars at different angles and depths to break up scar tissue. Microneedling needles yield more epidermal damage than does subcision, causing more bleeding and ultimately lengthening the healing time.

The mechanism of subcising deeper scar tissue also seems to be more effective than that of microneedling. It often takes fewer subcision treatments than microneedling treatments to achieve comparable improvement of depressed scars. Microneedling needles are limited to penetrating at best 2.5 mm beneath the skin surface, while subcision allows the freedom to penetrate deeper into the dermis to reach deeper dermal scars. Subcising also creates larger channels within the scar tissue, which create more space for collagen regrowth, while microneedling does not.

A technique that has shown to improve treatment outcomes is the use of a 26- or 30-gauge needle, moving back and forth in a fanning pattern under the scar tissue while simultaneously injecting lidocaine or saline in those channels. The injection of a fluid component, particularly that of lidocaine, can both decrease the pain as well as inflate the scar in question, allowing more collagen regrowth and wound growth factors to fill the “gaps” created.

Unless scars have a significant epidermal component in addition to their dermal component, subcising the scar is a more effective and has faster healing times. Both procedures can cause bruising , edema, and erythema. However, the epidermal damage that can occur in microneedling has significantly more downtime.

In addition, subcision is a more cost-effective treatment than microneedling. The required materials for subcision are limited to materials that are readily used within practices: needles, syringes, saline, and lidocaine. Microneedling, on the other hand, requires purchase of expensive tools, including microneedling pens, sterile single-use microneedling tips, and protective sleeves for the device, in addition to topical skin care products to apply after the treatment to promote safe healing.

While microneedling is remarkably effective for treatment of superficial scars, fine lines, and hypopigmentation, subcision tends to be more effective for the treatment of deeper scars such as box-car acne scars.

We love new technology in our practices; however, sometimes our tried and true procedures may prove to be a better option in the appropriate patient.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

We’re always working toward medical breakthroughs so we can provide the most effective treatments for our patients with cutting-edge technology; however, there is a lot to be said about the techniques that have paved the way for new medical devices.

For certain conditions, the efficacy of classic procedures often cannot be matched by their modern successors. Subcision for treatment of deep depressed scars, for example, is often a more effective option than microneedling and can produce results with less healing time and fewer treatments, and at a more cost-effective price.

Both subcision and microneedling improve the appearance of scars by creating wounds in an effort to break up scar tissue and trigger collagen regrowth. Microneedling involves the use of a microneedling pen with several small needles that glide across the skin at different depths and speeds. Subcision is achieved with one larger gauge needle that is injected into scars at different angles and depths to break up scar tissue. Microneedling needles yield more epidermal damage than does subcision, causing more bleeding and ultimately lengthening the healing time.

The mechanism of subcising deeper scar tissue also seems to be more effective than that of microneedling. It often takes fewer subcision treatments than microneedling treatments to achieve comparable improvement of depressed scars. Microneedling needles are limited to penetrating at best 2.5 mm beneath the skin surface, while subcision allows the freedom to penetrate deeper into the dermis to reach deeper dermal scars. Subcising also creates larger channels within the scar tissue, which create more space for collagen regrowth, while microneedling does not.

A technique that has shown to improve treatment outcomes is the use of a 26- or 30-gauge needle, moving back and forth in a fanning pattern under the scar tissue while simultaneously injecting lidocaine or saline in those channels. The injection of a fluid component, particularly that of lidocaine, can both decrease the pain as well as inflate the scar in question, allowing more collagen regrowth and wound growth factors to fill the “gaps” created.

Unless scars have a significant epidermal component in addition to their dermal component, subcising the scar is a more effective and has faster healing times. Both procedures can cause bruising , edema, and erythema. However, the epidermal damage that can occur in microneedling has significantly more downtime.

In addition, subcision is a more cost-effective treatment than microneedling. The required materials for subcision are limited to materials that are readily used within practices: needles, syringes, saline, and lidocaine. Microneedling, on the other hand, requires purchase of expensive tools, including microneedling pens, sterile single-use microneedling tips, and protective sleeves for the device, in addition to topical skin care products to apply after the treatment to promote safe healing.

While microneedling is remarkably effective for treatment of superficial scars, fine lines, and hypopigmentation, subcision tends to be more effective for the treatment of deeper scars such as box-car acne scars.

We love new technology in our practices; however, sometimes our tried and true procedures may prove to be a better option in the appropriate patient.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

We’re always working toward medical breakthroughs so we can provide the most effective treatments for our patients with cutting-edge technology; however, there is a lot to be said about the techniques that have paved the way for new medical devices.

For certain conditions, the efficacy of classic procedures often cannot be matched by their modern successors. Subcision for treatment of deep depressed scars, for example, is often a more effective option than microneedling and can produce results with less healing time and fewer treatments, and at a more cost-effective price.

Both subcision and microneedling improve the appearance of scars by creating wounds in an effort to break up scar tissue and trigger collagen regrowth. Microneedling involves the use of a microneedling pen with several small needles that glide across the skin at different depths and speeds. Subcision is achieved with one larger gauge needle that is injected into scars at different angles and depths to break up scar tissue. Microneedling needles yield more epidermal damage than does subcision, causing more bleeding and ultimately lengthening the healing time.

The mechanism of subcising deeper scar tissue also seems to be more effective than that of microneedling. It often takes fewer subcision treatments than microneedling treatments to achieve comparable improvement of depressed scars. Microneedling needles are limited to penetrating at best 2.5 mm beneath the skin surface, while subcision allows the freedom to penetrate deeper into the dermis to reach deeper dermal scars. Subcising also creates larger channels within the scar tissue, which create more space for collagen regrowth, while microneedling does not.

A technique that has shown to improve treatment outcomes is the use of a 26- or 30-gauge needle, moving back and forth in a fanning pattern under the scar tissue while simultaneously injecting lidocaine or saline in those channels. The injection of a fluid component, particularly that of lidocaine, can both decrease the pain as well as inflate the scar in question, allowing more collagen regrowth and wound growth factors to fill the “gaps” created.

Unless scars have a significant epidermal component in addition to their dermal component, subcising the scar is a more effective and has faster healing times. Both procedures can cause bruising , edema, and erythema. However, the epidermal damage that can occur in microneedling has significantly more downtime.

In addition, subcision is a more cost-effective treatment than microneedling. The required materials for subcision are limited to materials that are readily used within practices: needles, syringes, saline, and lidocaine. Microneedling, on the other hand, requires purchase of expensive tools, including microneedling pens, sterile single-use microneedling tips, and protective sleeves for the device, in addition to topical skin care products to apply after the treatment to promote safe healing.

While microneedling is remarkably effective for treatment of superficial scars, fine lines, and hypopigmentation, subcision tends to be more effective for the treatment of deeper scars such as box-car acne scars.

We love new technology in our practices; however, sometimes our tried and true procedures may prove to be a better option in the appropriate patient.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

Nanoparticles deliver Aurora kinase inhibitor with increased safety and efficacy

Using nanoparticles to encapsulate an Aurora B kinase inhibitor improved the efficacy and tolerability of the drug and allowed less frequent dosing in preclinical models, according to researchers.

“The AZD2811 nanoparticles identified in this study have the potential to increase efficacy at tolerable doses using a more convenient dosing regimen, which may in turn extend the utility of Aurora B kinase inhibition to a broader range of hematological and solid tumor cancer indications,” wrote Susan Ashton of AstraZeneca, and her colleagues (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad2355).

“The improved bone marrow profile observed with slow-releasing nanoparticles may enable efficacious combination treatments” with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

The study was undertaken because a free-drug version of the agent, known as AZD1152, had led to a significant improvement in the complete response rate of acute myeloid leukemia compared to standard of care in a phase II trial. Efficacy, however, was associated with major toxicities, including myelosuppression. Further, AZD1152 had to be administered as a 7-day continuous intravenous infusion.

By using the Accurin nanoparticle platform to vary drug release kinetics, the researchers devised a formulation to maximize the therapeutic effect of the kinase inhibitor while sparing healthy tissue. AZD1152 is a water-soluble prodrug of AZD2811, which the researchers used to develop their the nanoparticle formulation.

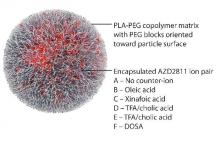

AZD2811 was encapsulated in polymeric nanoparticles termed Accurins, which are composed of block copolymers of poly-D,L-lactide (PLA) and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). Accurins accumulate in tumors, increasing the drug’s concentration and duration of exposure to the cancer cells. Organic acid counterions were used to increase encapsulation efficiency and decrease the release rate of AZD2811.

“We identified a formulation profile that could deliver active drug for more than 1 week, resulting in prolonged target inhibition in tumor tissue together with improved preclinical efficacy and therapeutic index over the AZD1152 prodrug in several animal models,” they wrote.

In nude rats bearing human colorectal adenocarcinoma SW620 xenografts, the nanoparticles inhibited kinase over a 96-hour time course, while the free drug resulted in complete enzyme recovery at 24 hours. Nanoparticles inhibited tumor growth by over 90%, compared with 58% for the free drug at twice the dose, and showed little toxicity as evidenced by stable body weight. Nanoparticles were retained in the tumor xenografts for up to 6 days, while the free drug was undetected in tumors 24 hours after administration.

“Although we selected a lead formulation using a tumor model (SW620) that supported the AZD1152 program – and, as such, we had extensive comparator data from which to benchmark the tolerability, PD, and efficacy of candidate nanoparticles – the model is subject to the known limitations of xenografted human tumor cell lines in assessing therapeutic candidates in oncology. Moreover, although rat bone marrow is commonly used to model myelotoxicity in humans, interrogation of the nanoparticle dose and schedule in patients may be required to achieve optimal clinical results,” they concluded.

AstraZeneca funded the study. Dr. Ashton and several coauthors are current or former employees and shareholders of AstraZeneca or BIND. The companies are developing the drug and technologies.

By encapsulating an Aurora B kinase inhibitor in Accurin particles, the researchers appear to have succeeded in enhancing the drug’s therapeutic activity and safety in mouse xenograft models. It remains to be seen how widely applicable this technology will be, and whether these results will be replicated in patients as the AZD1151-hQPA Accurin formulation heads toward first-in-human clinical trials. If the Accurin technology can solve the pharmacokinetic and toxicity issues for Aurora kinase inhibitors, it will likely also be applicable to other compounds that have encountered similar difficulties in clinical development and will add a formulation approach to address very meaningful and challenging issues that face many new molecules during clinical development.

David J. Bearss, Ph.D., is the chief executive officer of Tolero Pharmaceutical, Lehi, Utah. His remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report in Science Translational Medicine (2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1417).

By encapsulating an Aurora B kinase inhibitor in Accurin particles, the researchers appear to have succeeded in enhancing the drug’s therapeutic activity and safety in mouse xenograft models. It remains to be seen how widely applicable this technology will be, and whether these results will be replicated in patients as the AZD1151-hQPA Accurin formulation heads toward first-in-human clinical trials. If the Accurin technology can solve the pharmacokinetic and toxicity issues for Aurora kinase inhibitors, it will likely also be applicable to other compounds that have encountered similar difficulties in clinical development and will add a formulation approach to address very meaningful and challenging issues that face many new molecules during clinical development.

David J. Bearss, Ph.D., is the chief executive officer of Tolero Pharmaceutical, Lehi, Utah. His remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report in Science Translational Medicine (2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1417).

By encapsulating an Aurora B kinase inhibitor in Accurin particles, the researchers appear to have succeeded in enhancing the drug’s therapeutic activity and safety in mouse xenograft models. It remains to be seen how widely applicable this technology will be, and whether these results will be replicated in patients as the AZD1151-hQPA Accurin formulation heads toward first-in-human clinical trials. If the Accurin technology can solve the pharmacokinetic and toxicity issues for Aurora kinase inhibitors, it will likely also be applicable to other compounds that have encountered similar difficulties in clinical development and will add a formulation approach to address very meaningful and challenging issues that face many new molecules during clinical development.

David J. Bearss, Ph.D., is the chief executive officer of Tolero Pharmaceutical, Lehi, Utah. His remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report in Science Translational Medicine (2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1417).

Using nanoparticles to encapsulate an Aurora B kinase inhibitor improved the efficacy and tolerability of the drug and allowed less frequent dosing in preclinical models, according to researchers.

“The AZD2811 nanoparticles identified in this study have the potential to increase efficacy at tolerable doses using a more convenient dosing regimen, which may in turn extend the utility of Aurora B kinase inhibition to a broader range of hematological and solid tumor cancer indications,” wrote Susan Ashton of AstraZeneca, and her colleagues (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad2355).

“The improved bone marrow profile observed with slow-releasing nanoparticles may enable efficacious combination treatments” with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

The study was undertaken because a free-drug version of the agent, known as AZD1152, had led to a significant improvement in the complete response rate of acute myeloid leukemia compared to standard of care in a phase II trial. Efficacy, however, was associated with major toxicities, including myelosuppression. Further, AZD1152 had to be administered as a 7-day continuous intravenous infusion.

By using the Accurin nanoparticle platform to vary drug release kinetics, the researchers devised a formulation to maximize the therapeutic effect of the kinase inhibitor while sparing healthy tissue. AZD1152 is a water-soluble prodrug of AZD2811, which the researchers used to develop their the nanoparticle formulation.

AZD2811 was encapsulated in polymeric nanoparticles termed Accurins, which are composed of block copolymers of poly-D,L-lactide (PLA) and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). Accurins accumulate in tumors, increasing the drug’s concentration and duration of exposure to the cancer cells. Organic acid counterions were used to increase encapsulation efficiency and decrease the release rate of AZD2811.

“We identified a formulation profile that could deliver active drug for more than 1 week, resulting in prolonged target inhibition in tumor tissue together with improved preclinical efficacy and therapeutic index over the AZD1152 prodrug in several animal models,” they wrote.

In nude rats bearing human colorectal adenocarcinoma SW620 xenografts, the nanoparticles inhibited kinase over a 96-hour time course, while the free drug resulted in complete enzyme recovery at 24 hours. Nanoparticles inhibited tumor growth by over 90%, compared with 58% for the free drug at twice the dose, and showed little toxicity as evidenced by stable body weight. Nanoparticles were retained in the tumor xenografts for up to 6 days, while the free drug was undetected in tumors 24 hours after administration.

“Although we selected a lead formulation using a tumor model (SW620) that supported the AZD1152 program – and, as such, we had extensive comparator data from which to benchmark the tolerability, PD, and efficacy of candidate nanoparticles – the model is subject to the known limitations of xenografted human tumor cell lines in assessing therapeutic candidates in oncology. Moreover, although rat bone marrow is commonly used to model myelotoxicity in humans, interrogation of the nanoparticle dose and schedule in patients may be required to achieve optimal clinical results,” they concluded.