User login

Acute heart failure: What works, what doesn’t

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The primary treatment goal in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure is aggressive decongestion to get them feeling better and out of the hospital quicker – and the best way to achieve that is with high-dose loop diuretics administered intravenously at a dose equivalent to 2.5 times the previous oral dose, Dr. Akshay S. Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

This was the key lesson of the Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial, a prospective double-blind randomized trial that provides physicians with the best available data on how to decongest patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), according to Dr. Desai, a coinvestigator. The study was conducted by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Heart Failure Clinical Research Network.

The DOSE trial showed that it really doesn’t matter whether the diuretic is administered intravenously by continuous infusion or a bolus every 12 hours. The important thing is the high-dose strategy. It proved to be safe and was associated with accelerated decongestion as manifest in greater relief of dyspnea, greater weight loss and fluid loss, and a larger reduction in serum brain natriuretic peptide at 72 hours than low-dose therapy equivalent to the patient’s previous oral dose (N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 3;364[9]:797-805).

“The message for you in practice is that the route of diuretic administration is probably not important as long as you give an adequate dose. I would consider giving the higher dose of diuretic because it’s associated with more effective decongestion and perhaps shorter length of stay,” said Dr. Desai, director of heart failure disease management at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

There is a trade-off in ADHF between effective decongestion and worsening renal function as reflected in increased serum creatinine levels. Transient worsening of renal function occurred more frequently with the high-dose strategy in the DOSE trial, but it had no impact on clinical outcomes at 60 days follow-up. This finding is consistent with the results of an important Italian study showing that worsening renal function alone isn’t independently associated with increased risk of death or ADHF readmission; the problems arise in patients with worsening renal function and persistent congestion (Circ Heart Fail. 2012 Jan;5[1]:54-62).

Worsening congestion drives most hospitalizations for heart failure. And patients who are still congested at discharge are at dramatically increased risk for death or readmission in the ensuing 6 months. Yet the limitations of current therapy mean that even in expert hands, a substantial proportion of patients are discharged with clinically significant congestion. For example, in a retrospective analysis of nearly 500 patients enrolled in ADHF studies conducted by physicians in the NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network, only 52% were discharged free of congestion (Circ Heart Fail. 2015 Jul;8[4]:741-8).

Beyond aggressive treatment with loop diuretics, what else is useful in achieving the goal of hospital discharge with normalized filling pressures? Not much, according to a considerable body of research on the topic.

“The data tell us more about what not to do than what to do,” according to Dr. Desai.

For example, even though aggressive salt and fluid restriction is often forced upon patients hospitalized for ADHF on the rationale that this strategy may make it easier for diuretics to work, it’s not an evidence-based practice. Indeed, in a randomized clinical trial with blinded outcome assessments, an in-hospital diet restricted to a maximum intake of 800 mg of sodium and 800 mL of fluid daily had no effect on weight loss or a clinical congestion score (JAMA Intern Med. 2013 June 24;173[12]:1058-64).

“What it did very effectively was make patients thirsty. There are probably some patients where restriction of sodium and fluid intake is important, but routine use of tight restrictions is probably more harmful than helpful,” he observed.

The list of failed once-promising alternatives to diuretics in the setting of ADHF is impressive. It includes milrinone, tolvaptan, nesiritide, levosimendan, tezosentan, low-dose dopamine, and ultrafiltration. All had a sound mechanistic basis for the belief that they might improve outcomes, but in clinical trials none of them did.

Although routine use of pulmonary artery catheters to guide decongestion therapy in ADHF isn’t warranted because it has not been shown to be better than clinical assessment, there are certain situations where it is extremely helpful. For example, in the patient who isn’t responding to adequate doses of loop diuretics, it becomes important to understand the hemodynamics, which may involve systemic vascular resistance or a cardiac output problem.

Other situations where it’s worthwhile to consider placement of a pulmonary artery catheter include the patient of uncertain fluid status where it’s not possible to confidently estimate cardiac output at the bedside or markedly worsening renal function with empiric therapy.

Dr. Desai reported receiving research funding from Novartis and St. Jude Medical and serving as a paid consultant to Merck, Relypsa, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The primary treatment goal in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure is aggressive decongestion to get them feeling better and out of the hospital quicker – and the best way to achieve that is with high-dose loop diuretics administered intravenously at a dose equivalent to 2.5 times the previous oral dose, Dr. Akshay S. Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

This was the key lesson of the Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial, a prospective double-blind randomized trial that provides physicians with the best available data on how to decongest patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), according to Dr. Desai, a coinvestigator. The study was conducted by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Heart Failure Clinical Research Network.

The DOSE trial showed that it really doesn’t matter whether the diuretic is administered intravenously by continuous infusion or a bolus every 12 hours. The important thing is the high-dose strategy. It proved to be safe and was associated with accelerated decongestion as manifest in greater relief of dyspnea, greater weight loss and fluid loss, and a larger reduction in serum brain natriuretic peptide at 72 hours than low-dose therapy equivalent to the patient’s previous oral dose (N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 3;364[9]:797-805).

“The message for you in practice is that the route of diuretic administration is probably not important as long as you give an adequate dose. I would consider giving the higher dose of diuretic because it’s associated with more effective decongestion and perhaps shorter length of stay,” said Dr. Desai, director of heart failure disease management at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

There is a trade-off in ADHF between effective decongestion and worsening renal function as reflected in increased serum creatinine levels. Transient worsening of renal function occurred more frequently with the high-dose strategy in the DOSE trial, but it had no impact on clinical outcomes at 60 days follow-up. This finding is consistent with the results of an important Italian study showing that worsening renal function alone isn’t independently associated with increased risk of death or ADHF readmission; the problems arise in patients with worsening renal function and persistent congestion (Circ Heart Fail. 2012 Jan;5[1]:54-62).

Worsening congestion drives most hospitalizations for heart failure. And patients who are still congested at discharge are at dramatically increased risk for death or readmission in the ensuing 6 months. Yet the limitations of current therapy mean that even in expert hands, a substantial proportion of patients are discharged with clinically significant congestion. For example, in a retrospective analysis of nearly 500 patients enrolled in ADHF studies conducted by physicians in the NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network, only 52% were discharged free of congestion (Circ Heart Fail. 2015 Jul;8[4]:741-8).

Beyond aggressive treatment with loop diuretics, what else is useful in achieving the goal of hospital discharge with normalized filling pressures? Not much, according to a considerable body of research on the topic.

“The data tell us more about what not to do than what to do,” according to Dr. Desai.

For example, even though aggressive salt and fluid restriction is often forced upon patients hospitalized for ADHF on the rationale that this strategy may make it easier for diuretics to work, it’s not an evidence-based practice. Indeed, in a randomized clinical trial with blinded outcome assessments, an in-hospital diet restricted to a maximum intake of 800 mg of sodium and 800 mL of fluid daily had no effect on weight loss or a clinical congestion score (JAMA Intern Med. 2013 June 24;173[12]:1058-64).

“What it did very effectively was make patients thirsty. There are probably some patients where restriction of sodium and fluid intake is important, but routine use of tight restrictions is probably more harmful than helpful,” he observed.

The list of failed once-promising alternatives to diuretics in the setting of ADHF is impressive. It includes milrinone, tolvaptan, nesiritide, levosimendan, tezosentan, low-dose dopamine, and ultrafiltration. All had a sound mechanistic basis for the belief that they might improve outcomes, but in clinical trials none of them did.

Although routine use of pulmonary artery catheters to guide decongestion therapy in ADHF isn’t warranted because it has not been shown to be better than clinical assessment, there are certain situations where it is extremely helpful. For example, in the patient who isn’t responding to adequate doses of loop diuretics, it becomes important to understand the hemodynamics, which may involve systemic vascular resistance or a cardiac output problem.

Other situations where it’s worthwhile to consider placement of a pulmonary artery catheter include the patient of uncertain fluid status where it’s not possible to confidently estimate cardiac output at the bedside or markedly worsening renal function with empiric therapy.

Dr. Desai reported receiving research funding from Novartis and St. Jude Medical and serving as a paid consultant to Merck, Relypsa, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The primary treatment goal in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure is aggressive decongestion to get them feeling better and out of the hospital quicker – and the best way to achieve that is with high-dose loop diuretics administered intravenously at a dose equivalent to 2.5 times the previous oral dose, Dr. Akshay S. Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

This was the key lesson of the Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial, a prospective double-blind randomized trial that provides physicians with the best available data on how to decongest patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), according to Dr. Desai, a coinvestigator. The study was conducted by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Heart Failure Clinical Research Network.

The DOSE trial showed that it really doesn’t matter whether the diuretic is administered intravenously by continuous infusion or a bolus every 12 hours. The important thing is the high-dose strategy. It proved to be safe and was associated with accelerated decongestion as manifest in greater relief of dyspnea, greater weight loss and fluid loss, and a larger reduction in serum brain natriuretic peptide at 72 hours than low-dose therapy equivalent to the patient’s previous oral dose (N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 3;364[9]:797-805).

“The message for you in practice is that the route of diuretic administration is probably not important as long as you give an adequate dose. I would consider giving the higher dose of diuretic because it’s associated with more effective decongestion and perhaps shorter length of stay,” said Dr. Desai, director of heart failure disease management at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

There is a trade-off in ADHF between effective decongestion and worsening renal function as reflected in increased serum creatinine levels. Transient worsening of renal function occurred more frequently with the high-dose strategy in the DOSE trial, but it had no impact on clinical outcomes at 60 days follow-up. This finding is consistent with the results of an important Italian study showing that worsening renal function alone isn’t independently associated with increased risk of death or ADHF readmission; the problems arise in patients with worsening renal function and persistent congestion (Circ Heart Fail. 2012 Jan;5[1]:54-62).

Worsening congestion drives most hospitalizations for heart failure. And patients who are still congested at discharge are at dramatically increased risk for death or readmission in the ensuing 6 months. Yet the limitations of current therapy mean that even in expert hands, a substantial proportion of patients are discharged with clinically significant congestion. For example, in a retrospective analysis of nearly 500 patients enrolled in ADHF studies conducted by physicians in the NHLBI Heart Failure Clinical Research Network, only 52% were discharged free of congestion (Circ Heart Fail. 2015 Jul;8[4]:741-8).

Beyond aggressive treatment with loop diuretics, what else is useful in achieving the goal of hospital discharge with normalized filling pressures? Not much, according to a considerable body of research on the topic.

“The data tell us more about what not to do than what to do,” according to Dr. Desai.

For example, even though aggressive salt and fluid restriction is often forced upon patients hospitalized for ADHF on the rationale that this strategy may make it easier for diuretics to work, it’s not an evidence-based practice. Indeed, in a randomized clinical trial with blinded outcome assessments, an in-hospital diet restricted to a maximum intake of 800 mg of sodium and 800 mL of fluid daily had no effect on weight loss or a clinical congestion score (JAMA Intern Med. 2013 June 24;173[12]:1058-64).

“What it did very effectively was make patients thirsty. There are probably some patients where restriction of sodium and fluid intake is important, but routine use of tight restrictions is probably more harmful than helpful,” he observed.

The list of failed once-promising alternatives to diuretics in the setting of ADHF is impressive. It includes milrinone, tolvaptan, nesiritide, levosimendan, tezosentan, low-dose dopamine, and ultrafiltration. All had a sound mechanistic basis for the belief that they might improve outcomes, but in clinical trials none of them did.

Although routine use of pulmonary artery catheters to guide decongestion therapy in ADHF isn’t warranted because it has not been shown to be better than clinical assessment, there are certain situations where it is extremely helpful. For example, in the patient who isn’t responding to adequate doses of loop diuretics, it becomes important to understand the hemodynamics, which may involve systemic vascular resistance or a cardiac output problem.

Other situations where it’s worthwhile to consider placement of a pulmonary artery catheter include the patient of uncertain fluid status where it’s not possible to confidently estimate cardiac output at the bedside or markedly worsening renal function with empiric therapy.

Dr. Desai reported receiving research funding from Novartis and St. Jude Medical and serving as a paid consultant to Merck, Relypsa, and St. Jude Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Biosimilar program reshapes FDA’s objectivity

The U.S. program to develop biosimilar agents – somewhat akin to generic drugs for complex, biologic molecules that have come off patent protection – is gathering momentum, with the first U.S. biosimilar, Zarxio, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in March 2015 and with the second, a biosimilar to infliximab, recommended by an FDA advisory committee on Feb. 9 of this year.

What’s striking about the burgeoning biosimilar development process, created by the Affordable Care Act, is how it has morphed the FDA from its traditional role as an objective arbiter of a drug’s safety and efficacy into an active partner in shepherding biosimilars onto the market.

As explained on Feb. 4 in testimony before a Congressional committee by Dr. Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, the Biologic Price Competition and Innovation Act that was part of the Affordable Care Act launched a new U.S. drug-development pathway expressly for biosimilars. To implement that law, the FDA created an entirely new infrastructure within the agency – the Biosimilar Product Development Program – to help guide prospective manufacturers (called sponsors) of biosimilars through the regulatory and research hurdles to get a new biosimilar approved and into the hands of U.S. patients.

According to Dr. Woodcock, this program involves many steps where FDA staffers provide “review” and “advice” to sponsors on the studies they need to conduct and the analysis they need to perform to get their new products to market. The sponsor joins this program by paying an upfront fee that the FDA uses to keep the program running. Once a sponsor of a prospective biosimilar is in the program, the FDA’s staff helps guide the biosimilar development to a smooth conclusion.

To some extent, the FDA staff fills a similar role for conventional drug-development enterprises, conferring with manufacturers from the outset on matters such as the types and design of studies needed to insure success. What’s different about the biosimilar program is that conventional-drug development went on well before the FDA (or its predecessor) entered the scene, and the U.S. government created the FDA to police and regulate the drug production industry and protect the public against unscrupulous manufacturers of ineffective or dangerous drugs.

In contrast, the FDA itself created this new biosimilar development structure, and Dr. Woodcock noted that the in-depth review and advice meetings that the FDA offers to prospective biosimilar sponsors “has no counterpart in the Prescription Drug User Fee Act program and is unique” to the biosimilar program.

The consequence of having the FDA create the biosimilar development program from the ground up and structure it to provide such intimate input from the agency to sponsors at every step of the way seems to give the agency a notable and somewhat unnerving investment in the program’s success.

Dr. Woodcock called the approval of Zarxio an “exciting accomplishment,” and in her testimony before Congress she trumpeted the fact that as of January 2016 the biosimilar program was working on 59 proposed products that would mimic 18 different reference-product biologics. She also said that the FDA is “excited about the growing demand” for biosimilar-oriented meetings and marketing applications.

Don’t get me wrong: I think that the biosimilar concept is great, and has the potential to make what have become life-changing treatments more affordable and more available. And making the FDA such an active participant in getting biosimilar drugs created and approved is undoubtedly the most efficient way to accomplish this.

But in the process, the biosimilar program has changed the FDA from its more disengaged role as objective pharmaceutical judge into an active and seemingly not completely neutral codeveloper, risking at least the appearance of lost impartiality. Given that the FDA now wears two very different hats, we need to trust that the integrity and dedication of its staff will keep them from confusing their roles as proponent and gatekeeper.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The U.S. program to develop biosimilar agents – somewhat akin to generic drugs for complex, biologic molecules that have come off patent protection – is gathering momentum, with the first U.S. biosimilar, Zarxio, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in March 2015 and with the second, a biosimilar to infliximab, recommended by an FDA advisory committee on Feb. 9 of this year.

What’s striking about the burgeoning biosimilar development process, created by the Affordable Care Act, is how it has morphed the FDA from its traditional role as an objective arbiter of a drug’s safety and efficacy into an active partner in shepherding biosimilars onto the market.

As explained on Feb. 4 in testimony before a Congressional committee by Dr. Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, the Biologic Price Competition and Innovation Act that was part of the Affordable Care Act launched a new U.S. drug-development pathway expressly for biosimilars. To implement that law, the FDA created an entirely new infrastructure within the agency – the Biosimilar Product Development Program – to help guide prospective manufacturers (called sponsors) of biosimilars through the regulatory and research hurdles to get a new biosimilar approved and into the hands of U.S. patients.

According to Dr. Woodcock, this program involves many steps where FDA staffers provide “review” and “advice” to sponsors on the studies they need to conduct and the analysis they need to perform to get their new products to market. The sponsor joins this program by paying an upfront fee that the FDA uses to keep the program running. Once a sponsor of a prospective biosimilar is in the program, the FDA’s staff helps guide the biosimilar development to a smooth conclusion.

To some extent, the FDA staff fills a similar role for conventional drug-development enterprises, conferring with manufacturers from the outset on matters such as the types and design of studies needed to insure success. What’s different about the biosimilar program is that conventional-drug development went on well before the FDA (or its predecessor) entered the scene, and the U.S. government created the FDA to police and regulate the drug production industry and protect the public against unscrupulous manufacturers of ineffective or dangerous drugs.

In contrast, the FDA itself created this new biosimilar development structure, and Dr. Woodcock noted that the in-depth review and advice meetings that the FDA offers to prospective biosimilar sponsors “has no counterpart in the Prescription Drug User Fee Act program and is unique” to the biosimilar program.

The consequence of having the FDA create the biosimilar development program from the ground up and structure it to provide such intimate input from the agency to sponsors at every step of the way seems to give the agency a notable and somewhat unnerving investment in the program’s success.

Dr. Woodcock called the approval of Zarxio an “exciting accomplishment,” and in her testimony before Congress she trumpeted the fact that as of January 2016 the biosimilar program was working on 59 proposed products that would mimic 18 different reference-product biologics. She also said that the FDA is “excited about the growing demand” for biosimilar-oriented meetings and marketing applications.

Don’t get me wrong: I think that the biosimilar concept is great, and has the potential to make what have become life-changing treatments more affordable and more available. And making the FDA such an active participant in getting biosimilar drugs created and approved is undoubtedly the most efficient way to accomplish this.

But in the process, the biosimilar program has changed the FDA from its more disengaged role as objective pharmaceutical judge into an active and seemingly not completely neutral codeveloper, risking at least the appearance of lost impartiality. Given that the FDA now wears two very different hats, we need to trust that the integrity and dedication of its staff will keep them from confusing their roles as proponent and gatekeeper.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The U.S. program to develop biosimilar agents – somewhat akin to generic drugs for complex, biologic molecules that have come off patent protection – is gathering momentum, with the first U.S. biosimilar, Zarxio, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in March 2015 and with the second, a biosimilar to infliximab, recommended by an FDA advisory committee on Feb. 9 of this year.

What’s striking about the burgeoning biosimilar development process, created by the Affordable Care Act, is how it has morphed the FDA from its traditional role as an objective arbiter of a drug’s safety and efficacy into an active partner in shepherding biosimilars onto the market.

As explained on Feb. 4 in testimony before a Congressional committee by Dr. Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, the Biologic Price Competition and Innovation Act that was part of the Affordable Care Act launched a new U.S. drug-development pathway expressly for biosimilars. To implement that law, the FDA created an entirely new infrastructure within the agency – the Biosimilar Product Development Program – to help guide prospective manufacturers (called sponsors) of biosimilars through the regulatory and research hurdles to get a new biosimilar approved and into the hands of U.S. patients.

According to Dr. Woodcock, this program involves many steps where FDA staffers provide “review” and “advice” to sponsors on the studies they need to conduct and the analysis they need to perform to get their new products to market. The sponsor joins this program by paying an upfront fee that the FDA uses to keep the program running. Once a sponsor of a prospective biosimilar is in the program, the FDA’s staff helps guide the biosimilar development to a smooth conclusion.

To some extent, the FDA staff fills a similar role for conventional drug-development enterprises, conferring with manufacturers from the outset on matters such as the types and design of studies needed to insure success. What’s different about the biosimilar program is that conventional-drug development went on well before the FDA (or its predecessor) entered the scene, and the U.S. government created the FDA to police and regulate the drug production industry and protect the public against unscrupulous manufacturers of ineffective or dangerous drugs.

In contrast, the FDA itself created this new biosimilar development structure, and Dr. Woodcock noted that the in-depth review and advice meetings that the FDA offers to prospective biosimilar sponsors “has no counterpart in the Prescription Drug User Fee Act program and is unique” to the biosimilar program.

The consequence of having the FDA create the biosimilar development program from the ground up and structure it to provide such intimate input from the agency to sponsors at every step of the way seems to give the agency a notable and somewhat unnerving investment in the program’s success.

Dr. Woodcock called the approval of Zarxio an “exciting accomplishment,” and in her testimony before Congress she trumpeted the fact that as of January 2016 the biosimilar program was working on 59 proposed products that would mimic 18 different reference-product biologics. She also said that the FDA is “excited about the growing demand” for biosimilar-oriented meetings and marketing applications.

Don’t get me wrong: I think that the biosimilar concept is great, and has the potential to make what have become life-changing treatments more affordable and more available. And making the FDA such an active participant in getting biosimilar drugs created and approved is undoubtedly the most efficient way to accomplish this.

But in the process, the biosimilar program has changed the FDA from its more disengaged role as objective pharmaceutical judge into an active and seemingly not completely neutral codeveloper, risking at least the appearance of lost impartiality. Given that the FDA now wears two very different hats, we need to trust that the integrity and dedication of its staff will keep them from confusing their roles as proponent and gatekeeper.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Use preventive strategies to lower cardiovascular risks in bipolar I

The significantly increased risk of myocardial infarction or stroke in patients with bipolar I disorder appears to be tied more to preventive factors than to cardiovascular risk factors. However, bipolar I patients with a history of psychosis have an marginally increased risk of MI or stroke, a population-based cohort study showed.

The researchers came to those conclusions after analyzing residents’ health records and death certificates in Olmsted County, Minn., which were contained within the Rochester Epidemiology Project database. The study’s participants included 334 patients with bipolar I disorder and 334 people without bipolar disorder, although one of the patients who did not have bipolar I at the beginning of the study was later diagnosed with the disorder. All participants had been residents of Olmsted County from Jan. 1, 1966, through Dec. 31,1996.

Patients continued to be followed until Dec. 31, 2013, unless one of the following events occurred before that date: the patient had an MI or stroke, was lost to follow-up, or died before the end of the study. A patient experiencing an MI, stroke, or death or a patient disappearing from the database triggered an end to that patient’s participation in the study.

When an individual having an MI or a stroke was treated as a composite outcome, bipolar I disorder patients had a significantly increased risk of experiencing a fatal or non-fatal MI or stroke, compared with the individuals in the control group (P = .04). The risk was no longer significant after the researchers adjusted for the following potential baseline confounders of the association between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular disease: alcohol use disorder, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking (P = .46).

Meanwhile, a secondary analysis of the data showed that history of psychosis was indeed tied to a marginally increased risk of MI or stroke (P =.06).

“It will be fundamental to improve current preventive strategies to decrease the prevalence of smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, and diabetes among patients with bipolar disorder,” said Dr. Miguel L. Prieto of the department of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues. “Moreover, we detected a possible higher risk of MI/stroke in the subgroup of patients with history of psychosis that certainly warrants replication.”

Future research also should seek to determine early biomarkers of atherosclerosis, the researchers said.

Read the study in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.015).

The significantly increased risk of myocardial infarction or stroke in patients with bipolar I disorder appears to be tied more to preventive factors than to cardiovascular risk factors. However, bipolar I patients with a history of psychosis have an marginally increased risk of MI or stroke, a population-based cohort study showed.

The researchers came to those conclusions after analyzing residents’ health records and death certificates in Olmsted County, Minn., which were contained within the Rochester Epidemiology Project database. The study’s participants included 334 patients with bipolar I disorder and 334 people without bipolar disorder, although one of the patients who did not have bipolar I at the beginning of the study was later diagnosed with the disorder. All participants had been residents of Olmsted County from Jan. 1, 1966, through Dec. 31,1996.

Patients continued to be followed until Dec. 31, 2013, unless one of the following events occurred before that date: the patient had an MI or stroke, was lost to follow-up, or died before the end of the study. A patient experiencing an MI, stroke, or death or a patient disappearing from the database triggered an end to that patient’s participation in the study.

When an individual having an MI or a stroke was treated as a composite outcome, bipolar I disorder patients had a significantly increased risk of experiencing a fatal or non-fatal MI or stroke, compared with the individuals in the control group (P = .04). The risk was no longer significant after the researchers adjusted for the following potential baseline confounders of the association between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular disease: alcohol use disorder, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking (P = .46).

Meanwhile, a secondary analysis of the data showed that history of psychosis was indeed tied to a marginally increased risk of MI or stroke (P =.06).

“It will be fundamental to improve current preventive strategies to decrease the prevalence of smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, and diabetes among patients with bipolar disorder,” said Dr. Miguel L. Prieto of the department of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues. “Moreover, we detected a possible higher risk of MI/stroke in the subgroup of patients with history of psychosis that certainly warrants replication.”

Future research also should seek to determine early biomarkers of atherosclerosis, the researchers said.

Read the study in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.015).

The significantly increased risk of myocardial infarction or stroke in patients with bipolar I disorder appears to be tied more to preventive factors than to cardiovascular risk factors. However, bipolar I patients with a history of psychosis have an marginally increased risk of MI or stroke, a population-based cohort study showed.

The researchers came to those conclusions after analyzing residents’ health records and death certificates in Olmsted County, Minn., which were contained within the Rochester Epidemiology Project database. The study’s participants included 334 patients with bipolar I disorder and 334 people without bipolar disorder, although one of the patients who did not have bipolar I at the beginning of the study was later diagnosed with the disorder. All participants had been residents of Olmsted County from Jan. 1, 1966, through Dec. 31,1996.

Patients continued to be followed until Dec. 31, 2013, unless one of the following events occurred before that date: the patient had an MI or stroke, was lost to follow-up, or died before the end of the study. A patient experiencing an MI, stroke, or death or a patient disappearing from the database triggered an end to that patient’s participation in the study.

When an individual having an MI or a stroke was treated as a composite outcome, bipolar I disorder patients had a significantly increased risk of experiencing a fatal or non-fatal MI or stroke, compared with the individuals in the control group (P = .04). The risk was no longer significant after the researchers adjusted for the following potential baseline confounders of the association between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular disease: alcohol use disorder, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking (P = .46).

Meanwhile, a secondary analysis of the data showed that history of psychosis was indeed tied to a marginally increased risk of MI or stroke (P =.06).

“It will be fundamental to improve current preventive strategies to decrease the prevalence of smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, and diabetes among patients with bipolar disorder,” said Dr. Miguel L. Prieto of the department of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues. “Moreover, we detected a possible higher risk of MI/stroke in the subgroup of patients with history of psychosis that certainly warrants replication.”

Future research also should seek to determine early biomarkers of atherosclerosis, the researchers said.

Read the study in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.015).

FROM JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

What’s next for Watchman stroke prevention device

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The goal is finally in sight following an odyssey to develop the Watchman left atrial appendage closure device as a safe and effective alternative to oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

It’s all coming together: The Watchman, a small percutaneously delivered parachute-like device, has received FDA marketing approval as the sole authorized left atrial appendage closure device in this country on the strength of two compellingly positive randomized controlled trials. A recent meta-analysis of those trials showed significantly fewer hemorrhagic strokes, fewer cardiovascular or unexplained deaths, and fewer nonprocedural bleeding events in Watchman recipients than in patients randomized to warfarin. And a cost-effectiveness analysis has concluded that after 8 years, the Watchman becomes “the dominant strategy” – meaning more effective and less costly for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) having a contraindication to warfarin – compared with the novel oral anticoagulant apixaban (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 22;66[24]:2728-39).

Moreover, the final pieces required for the Watchman to become a mainstream reimbursable therapy are falling into place. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), the American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) have jointly issued institutional and operator requirements for left atrial appendage occlusion programs (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 8. pii: S0735-1097[15]07550-6). The ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry has set up a new left atrial occlusion registry. And most important of all from a reimbursement standpoint, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has released a preliminary National Coverage Determination for left atrial appendage occlusion.

“This will affect your patients and your lives,” noted Dr. Holmes of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He and the Mayo Clinic share a financial interest in the Watchman technology, which has been licensed to Boston Scientific.

The CMS will cover the Watchman only when the catheter procedure is performed by an experienced interventional cardiologist or electrophysiologist in an experienced center as defined by the SCAI/ACC/HRS standards, and only in patients enrolled in the national prospective registry. The registry will monitor operator and device-related complications, stroke and systemic embolism rates, deaths, and major bleeding rates for 5 years post-procedure.

“If you want to be in this field, you will be in that registry because reimbursement will depend on that,” Dr. Holmes explained. “This registry will be incredibly important. It will tell us how we’re doing, what we should be doing, and what we could potentially be doing in the future.”

One hitch is that the preliminary National Coverage Determination states that coverage will be limited to AF patients with high stroke-risk and HAS-BLED scores as well as a contraindication to warfarin, whereas the FDA-approved indication says patients must be deemed by their physician to be suitable for warfarin.

“In this particular case, CMS was not talking with FDA. We don’t know how that will get sorted out,” according to the cardiologist. “But as soon as CMS comes through with their final regulatory coverage determination, I think we will finally be there. We’ll then be able to offer this as a treatment strategy for stroke prevention in selected patients with atrial fibrillation, realizing that with this device there’s a 40% reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular or unexplained death, stroke, and systemic embolism compared to warfarin.”

That figure of a 40% relative risk reduction comes from the 46-month follow-up data in the randomized PROTECT AF trial (JAMA. 2014 Nov 19;312[19]:1988-98).

More recently, Dr. Holmes and his coinvestigators published a patient-level meta-analysis of data from PROTECT AF and PREVAIL, the other randomized trial of the Watchman versus warfarin. They reported that Watchman recipients had a 78% reduction in hemorrhagic strokes, a 52% reduction in cardiovascular or unexplained deaths, and a 49% lower rate of nonprocedural bleeding, compared with patients assigned to warfarin (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Jun 23;65[24]:2614-23).

There have been no randomized trials comparing the Watchman to novel oral anticoagulants.

Dr. Holmes said the worldwide experience to date has been that roughly 95% of AF patients are able to safely go off warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant 12 months after Watchman placement.

“So instead of taking eight drugs when you’re 75 years old, you can take seven. Most patients think that’s a pretty good deal,” the cardiologist observed.

Session moderator Dr. Samuel J. Asirvatham posed a question: Since recurrence of AF following catheter ablation is common and it’s now thought that up to 20% of AF arises from foci located in the left atrial appendage, what about combining standard catheter ablation of AF via pulmonary vein isolation with placement of the Watchman in a single procedure?

If such a combined procedure can be done efficiently, it should enable recipients of AF catheter ablation to safely go off oral anticoagulation, noted Dr. Asirvatham, an electrophysiologist who is professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Holmes said several small studies of patients who have received combined AF ablation and Watchman implantation have been published.

“It’s uncertain whether left atrial appendage closure will affect AF recurrence rates post ablation, but it should reduce stroke risk. It’s a terribly important field of exploration that will be pursued in registries both in Europe and the United States,” he said.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The goal is finally in sight following an odyssey to develop the Watchman left atrial appendage closure device as a safe and effective alternative to oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

It’s all coming together: The Watchman, a small percutaneously delivered parachute-like device, has received FDA marketing approval as the sole authorized left atrial appendage closure device in this country on the strength of two compellingly positive randomized controlled trials. A recent meta-analysis of those trials showed significantly fewer hemorrhagic strokes, fewer cardiovascular or unexplained deaths, and fewer nonprocedural bleeding events in Watchman recipients than in patients randomized to warfarin. And a cost-effectiveness analysis has concluded that after 8 years, the Watchman becomes “the dominant strategy” – meaning more effective and less costly for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) having a contraindication to warfarin – compared with the novel oral anticoagulant apixaban (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 22;66[24]:2728-39).

Moreover, the final pieces required for the Watchman to become a mainstream reimbursable therapy are falling into place. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), the American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) have jointly issued institutional and operator requirements for left atrial appendage occlusion programs (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 8. pii: S0735-1097[15]07550-6). The ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry has set up a new left atrial occlusion registry. And most important of all from a reimbursement standpoint, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has released a preliminary National Coverage Determination for left atrial appendage occlusion.

“This will affect your patients and your lives,” noted Dr. Holmes of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He and the Mayo Clinic share a financial interest in the Watchman technology, which has been licensed to Boston Scientific.

The CMS will cover the Watchman only when the catheter procedure is performed by an experienced interventional cardiologist or electrophysiologist in an experienced center as defined by the SCAI/ACC/HRS standards, and only in patients enrolled in the national prospective registry. The registry will monitor operator and device-related complications, stroke and systemic embolism rates, deaths, and major bleeding rates for 5 years post-procedure.

“If you want to be in this field, you will be in that registry because reimbursement will depend on that,” Dr. Holmes explained. “This registry will be incredibly important. It will tell us how we’re doing, what we should be doing, and what we could potentially be doing in the future.”

One hitch is that the preliminary National Coverage Determination states that coverage will be limited to AF patients with high stroke-risk and HAS-BLED scores as well as a contraindication to warfarin, whereas the FDA-approved indication says patients must be deemed by their physician to be suitable for warfarin.

“In this particular case, CMS was not talking with FDA. We don’t know how that will get sorted out,” according to the cardiologist. “But as soon as CMS comes through with their final regulatory coverage determination, I think we will finally be there. We’ll then be able to offer this as a treatment strategy for stroke prevention in selected patients with atrial fibrillation, realizing that with this device there’s a 40% reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular or unexplained death, stroke, and systemic embolism compared to warfarin.”

That figure of a 40% relative risk reduction comes from the 46-month follow-up data in the randomized PROTECT AF trial (JAMA. 2014 Nov 19;312[19]:1988-98).

More recently, Dr. Holmes and his coinvestigators published a patient-level meta-analysis of data from PROTECT AF and PREVAIL, the other randomized trial of the Watchman versus warfarin. They reported that Watchman recipients had a 78% reduction in hemorrhagic strokes, a 52% reduction in cardiovascular or unexplained deaths, and a 49% lower rate of nonprocedural bleeding, compared with patients assigned to warfarin (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Jun 23;65[24]:2614-23).

There have been no randomized trials comparing the Watchman to novel oral anticoagulants.

Dr. Holmes said the worldwide experience to date has been that roughly 95% of AF patients are able to safely go off warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant 12 months after Watchman placement.

“So instead of taking eight drugs when you’re 75 years old, you can take seven. Most patients think that’s a pretty good deal,” the cardiologist observed.

Session moderator Dr. Samuel J. Asirvatham posed a question: Since recurrence of AF following catheter ablation is common and it’s now thought that up to 20% of AF arises from foci located in the left atrial appendage, what about combining standard catheter ablation of AF via pulmonary vein isolation with placement of the Watchman in a single procedure?

If such a combined procedure can be done efficiently, it should enable recipients of AF catheter ablation to safely go off oral anticoagulation, noted Dr. Asirvatham, an electrophysiologist who is professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Holmes said several small studies of patients who have received combined AF ablation and Watchman implantation have been published.

“It’s uncertain whether left atrial appendage closure will affect AF recurrence rates post ablation, but it should reduce stroke risk. It’s a terribly important field of exploration that will be pursued in registries both in Europe and the United States,” he said.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The goal is finally in sight following an odyssey to develop the Watchman left atrial appendage closure device as a safe and effective alternative to oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

It’s all coming together: The Watchman, a small percutaneously delivered parachute-like device, has received FDA marketing approval as the sole authorized left atrial appendage closure device in this country on the strength of two compellingly positive randomized controlled trials. A recent meta-analysis of those trials showed significantly fewer hemorrhagic strokes, fewer cardiovascular or unexplained deaths, and fewer nonprocedural bleeding events in Watchman recipients than in patients randomized to warfarin. And a cost-effectiveness analysis has concluded that after 8 years, the Watchman becomes “the dominant strategy” – meaning more effective and less costly for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) having a contraindication to warfarin – compared with the novel oral anticoagulant apixaban (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 22;66[24]:2728-39).

Moreover, the final pieces required for the Watchman to become a mainstream reimbursable therapy are falling into place. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), the American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) have jointly issued institutional and operator requirements for left atrial appendage occlusion programs (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 8. pii: S0735-1097[15]07550-6). The ACC’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry has set up a new left atrial occlusion registry. And most important of all from a reimbursement standpoint, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has released a preliminary National Coverage Determination for left atrial appendage occlusion.

“This will affect your patients and your lives,” noted Dr. Holmes of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He and the Mayo Clinic share a financial interest in the Watchman technology, which has been licensed to Boston Scientific.

The CMS will cover the Watchman only when the catheter procedure is performed by an experienced interventional cardiologist or electrophysiologist in an experienced center as defined by the SCAI/ACC/HRS standards, and only in patients enrolled in the national prospective registry. The registry will monitor operator and device-related complications, stroke and systemic embolism rates, deaths, and major bleeding rates for 5 years post-procedure.

“If you want to be in this field, you will be in that registry because reimbursement will depend on that,” Dr. Holmes explained. “This registry will be incredibly important. It will tell us how we’re doing, what we should be doing, and what we could potentially be doing in the future.”

One hitch is that the preliminary National Coverage Determination states that coverage will be limited to AF patients with high stroke-risk and HAS-BLED scores as well as a contraindication to warfarin, whereas the FDA-approved indication says patients must be deemed by their physician to be suitable for warfarin.

“In this particular case, CMS was not talking with FDA. We don’t know how that will get sorted out,” according to the cardiologist. “But as soon as CMS comes through with their final regulatory coverage determination, I think we will finally be there. We’ll then be able to offer this as a treatment strategy for stroke prevention in selected patients with atrial fibrillation, realizing that with this device there’s a 40% reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular or unexplained death, stroke, and systemic embolism compared to warfarin.”

That figure of a 40% relative risk reduction comes from the 46-month follow-up data in the randomized PROTECT AF trial (JAMA. 2014 Nov 19;312[19]:1988-98).

More recently, Dr. Holmes and his coinvestigators published a patient-level meta-analysis of data from PROTECT AF and PREVAIL, the other randomized trial of the Watchman versus warfarin. They reported that Watchman recipients had a 78% reduction in hemorrhagic strokes, a 52% reduction in cardiovascular or unexplained deaths, and a 49% lower rate of nonprocedural bleeding, compared with patients assigned to warfarin (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Jun 23;65[24]:2614-23).

There have been no randomized trials comparing the Watchman to novel oral anticoagulants.

Dr. Holmes said the worldwide experience to date has been that roughly 95% of AF patients are able to safely go off warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant 12 months after Watchman placement.

“So instead of taking eight drugs when you’re 75 years old, you can take seven. Most patients think that’s a pretty good deal,” the cardiologist observed.

Session moderator Dr. Samuel J. Asirvatham posed a question: Since recurrence of AF following catheter ablation is common and it’s now thought that up to 20% of AF arises from foci located in the left atrial appendage, what about combining standard catheter ablation of AF via pulmonary vein isolation with placement of the Watchman in a single procedure?

If such a combined procedure can be done efficiently, it should enable recipients of AF catheter ablation to safely go off oral anticoagulation, noted Dr. Asirvatham, an electrophysiologist who is professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Holmes said several small studies of patients who have received combined AF ablation and Watchman implantation have been published.

“It’s uncertain whether left atrial appendage closure will affect AF recurrence rates post ablation, but it should reduce stroke risk. It’s a terribly important field of exploration that will be pursued in registries both in Europe and the United States,” he said.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Fibromyalgia found in 20% with spondyloarthritis; could affect management decisions

The presence of fibromyalgia in patients who are undergoing treatment of spondyloarthritis (SpA) is associated with higher measures of disease activity and shorter duration of first-time treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, according to results of a study measuring the impact and prevalence of fibromyalgia coexisting with SpA.

The results confirm “that the existence of concomitant FM [fibromyalgia] in SpA might complicate the evaluation of treatment response and [suggest] that coexistence of FM should be carefully screened when initiating a TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] and/or evaluating its treatment effect, especially in the presence of peripheral and/or enthesitic symptoms and in the presence of very severe disease activity and patient-reported scores,” wrote Dr. Natalia Bello and her colleagues at Cochin Hospital, Paris (Arthritis Res Ther. 2016 Feb 9;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0943-z).

They recruited patients from Cochin Hospital, a tertiary care facility, and its rheumatology department’s outpatient clinic. Rather than use the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria of FM or the 2010 ACR or modified 2010 ACR diagnostic criteria, which were developed for research and classification purposes, the investigators diagnosed FM based on a score of 5 or 6 on the six-question, self-reported Fibromyalgia Rapid Screening Tool (FiRST), which has 90.5% sensitivity and 85.7% specificity for FM. Patients’ SpA diagnoses were made by their rheumatologists. Overall, 30% of the cohort was female and had a mean age of 43 years.

The overall FM prevalence in the cohort was 21.4% (42 of 196 patients) and did not differ significantly according to whether the patients met either the clinical or imaging ASAS (Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society) criteria (21.3% vs. 18.8%, respectively) or whether they did or did not fulfill the ASAS criteria (21.1% vs. 30.0%, respectively).

Previous studies have shown the prevalence of FM at 12.6%-15.0% in SpA patients. Classifying axial SpA based on the clinical arm criteria alone has been controversial, the investigators said, mainly because it does not require an objective sign of inflammation (abnormal C-reactive protein or presence of inflammatory lesions seen on MRI of the sacroiliac joint) or structural damage in the sacroiliac joint seen on pelvic radiographs. But at least in this study there was no difference in FM prevalence in regard to whether patients met either the imaging and clinical arms of the ASAS classification criteria for axial SpA or both.

The study, according to the best knowledge of the investigators, is the first “to evaluate the prevalence of FM in a population of patients with SpA with regard to the fulfillment of the ASAS classification criteria.”

FM patients had as expected a significantly higher rate of either history of depression, or use of psychotropic drugs or strong opioids, compared with patients without FM (67% vs. 35%; P less than .01). Rates of exposure to treatment with different drug types (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or conventional antirheumatic disease-modifying drugs) did not differ between those with and without FM, but FM patients switched significantly more often from their first TNFi (15.2% vs. 4.0%) and used it for a significantly shorter mean duration (1.7 vs. 3.5 years). The percentage of patients still taking their first TNFi after 2 years also was significantly lower among FM patients (28.1% vs. 41.7%).

Within the entire cohort, FM patients more often had enthesitis (59.5% vs. 39.0%, P = .01), a higher total Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (4.7 vs. 2.6; P less than .01), higher global visual analog scale (5.9 vs. 3.0; P less than .01), and higher Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (4.8 vs. 2.0; P less than .01).

The authors suggested that FM patients’ higher rates of peripheral symptoms and enthesitis may warrant the use of the FiRST questionnaire in clinical practice before starting a TNFi in SpA patients to detect potentially coexisting FM.

The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

The presence of fibromyalgia in patients who are undergoing treatment of spondyloarthritis (SpA) is associated with higher measures of disease activity and shorter duration of first-time treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, according to results of a study measuring the impact and prevalence of fibromyalgia coexisting with SpA.

The results confirm “that the existence of concomitant FM [fibromyalgia] in SpA might complicate the evaluation of treatment response and [suggest] that coexistence of FM should be carefully screened when initiating a TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] and/or evaluating its treatment effect, especially in the presence of peripheral and/or enthesitic symptoms and in the presence of very severe disease activity and patient-reported scores,” wrote Dr. Natalia Bello and her colleagues at Cochin Hospital, Paris (Arthritis Res Ther. 2016 Feb 9;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0943-z).

They recruited patients from Cochin Hospital, a tertiary care facility, and its rheumatology department’s outpatient clinic. Rather than use the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria of FM or the 2010 ACR or modified 2010 ACR diagnostic criteria, which were developed for research and classification purposes, the investigators diagnosed FM based on a score of 5 or 6 on the six-question, self-reported Fibromyalgia Rapid Screening Tool (FiRST), which has 90.5% sensitivity and 85.7% specificity for FM. Patients’ SpA diagnoses were made by their rheumatologists. Overall, 30% of the cohort was female and had a mean age of 43 years.

The overall FM prevalence in the cohort was 21.4% (42 of 196 patients) and did not differ significantly according to whether the patients met either the clinical or imaging ASAS (Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society) criteria (21.3% vs. 18.8%, respectively) or whether they did or did not fulfill the ASAS criteria (21.1% vs. 30.0%, respectively).

Previous studies have shown the prevalence of FM at 12.6%-15.0% in SpA patients. Classifying axial SpA based on the clinical arm criteria alone has been controversial, the investigators said, mainly because it does not require an objective sign of inflammation (abnormal C-reactive protein or presence of inflammatory lesions seen on MRI of the sacroiliac joint) or structural damage in the sacroiliac joint seen on pelvic radiographs. But at least in this study there was no difference in FM prevalence in regard to whether patients met either the imaging and clinical arms of the ASAS classification criteria for axial SpA or both.

The study, according to the best knowledge of the investigators, is the first “to evaluate the prevalence of FM in a population of patients with SpA with regard to the fulfillment of the ASAS classification criteria.”

FM patients had as expected a significantly higher rate of either history of depression, or use of psychotropic drugs or strong opioids, compared with patients without FM (67% vs. 35%; P less than .01). Rates of exposure to treatment with different drug types (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or conventional antirheumatic disease-modifying drugs) did not differ between those with and without FM, but FM patients switched significantly more often from their first TNFi (15.2% vs. 4.0%) and used it for a significantly shorter mean duration (1.7 vs. 3.5 years). The percentage of patients still taking their first TNFi after 2 years also was significantly lower among FM patients (28.1% vs. 41.7%).

Within the entire cohort, FM patients more often had enthesitis (59.5% vs. 39.0%, P = .01), a higher total Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (4.7 vs. 2.6; P less than .01), higher global visual analog scale (5.9 vs. 3.0; P less than .01), and higher Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (4.8 vs. 2.0; P less than .01).

The authors suggested that FM patients’ higher rates of peripheral symptoms and enthesitis may warrant the use of the FiRST questionnaire in clinical practice before starting a TNFi in SpA patients to detect potentially coexisting FM.

The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

The presence of fibromyalgia in patients who are undergoing treatment of spondyloarthritis (SpA) is associated with higher measures of disease activity and shorter duration of first-time treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, according to results of a study measuring the impact and prevalence of fibromyalgia coexisting with SpA.

The results confirm “that the existence of concomitant FM [fibromyalgia] in SpA might complicate the evaluation of treatment response and [suggest] that coexistence of FM should be carefully screened when initiating a TNFi [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor] and/or evaluating its treatment effect, especially in the presence of peripheral and/or enthesitic symptoms and in the presence of very severe disease activity and patient-reported scores,” wrote Dr. Natalia Bello and her colleagues at Cochin Hospital, Paris (Arthritis Res Ther. 2016 Feb 9;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0943-z).

They recruited patients from Cochin Hospital, a tertiary care facility, and its rheumatology department’s outpatient clinic. Rather than use the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria of FM or the 2010 ACR or modified 2010 ACR diagnostic criteria, which were developed for research and classification purposes, the investigators diagnosed FM based on a score of 5 or 6 on the six-question, self-reported Fibromyalgia Rapid Screening Tool (FiRST), which has 90.5% sensitivity and 85.7% specificity for FM. Patients’ SpA diagnoses were made by their rheumatologists. Overall, 30% of the cohort was female and had a mean age of 43 years.

The overall FM prevalence in the cohort was 21.4% (42 of 196 patients) and did not differ significantly according to whether the patients met either the clinical or imaging ASAS (Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society) criteria (21.3% vs. 18.8%, respectively) or whether they did or did not fulfill the ASAS criteria (21.1% vs. 30.0%, respectively).

Previous studies have shown the prevalence of FM at 12.6%-15.0% in SpA patients. Classifying axial SpA based on the clinical arm criteria alone has been controversial, the investigators said, mainly because it does not require an objective sign of inflammation (abnormal C-reactive protein or presence of inflammatory lesions seen on MRI of the sacroiliac joint) or structural damage in the sacroiliac joint seen on pelvic radiographs. But at least in this study there was no difference in FM prevalence in regard to whether patients met either the imaging and clinical arms of the ASAS classification criteria for axial SpA or both.

The study, according to the best knowledge of the investigators, is the first “to evaluate the prevalence of FM in a population of patients with SpA with regard to the fulfillment of the ASAS classification criteria.”

FM patients had as expected a significantly higher rate of either history of depression, or use of psychotropic drugs or strong opioids, compared with patients without FM (67% vs. 35%; P less than .01). Rates of exposure to treatment with different drug types (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or conventional antirheumatic disease-modifying drugs) did not differ between those with and without FM, but FM patients switched significantly more often from their first TNFi (15.2% vs. 4.0%) and used it for a significantly shorter mean duration (1.7 vs. 3.5 years). The percentage of patients still taking their first TNFi after 2 years also was significantly lower among FM patients (28.1% vs. 41.7%).

Within the entire cohort, FM patients more often had enthesitis (59.5% vs. 39.0%, P = .01), a higher total Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (4.7 vs. 2.6; P less than .01), higher global visual analog scale (5.9 vs. 3.0; P less than .01), and higher Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (4.8 vs. 2.0; P less than .01).

The authors suggested that FM patients’ higher rates of peripheral symptoms and enthesitis may warrant the use of the FiRST questionnaire in clinical practice before starting a TNFi in SpA patients to detect potentially coexisting FM.

The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

FROM ARTHRITIS RESEARCH & THERAPY

Key clinical point: Coexistence of fibromyalgia in patients diagnosed with spondyloarthritis might be slightly more frequent than previously reported and does not differ according to whether SpA was classified based on imaging or clinical criteria.

Major finding: The overall FM prevalence in the cohort was 21.4% (42 of 196 patients) and did not differ significantly according to whether the patients met either the clinical or imaging ASAS criteria (21.3% vs. 18.8%, respectively).

Data source: A cohort study of 196 patients diagnosed with spondyloarthritis.

Disclosures: The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

Gretchen Tietjen, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dronabinol: A Controversial Acute Leukemia Treatment

Researchers from University Hospital Tübingen, Germany, say that although the data for treating acute leukemia with dronabinol (THC), a cannabinoid derivative, are “controversial,” it has been shown to have antitumor potential for several cancers. When the researchers tested THC in several leukemia cell lines and native leukemia blasts cultured ex vivo, they found “meaningful” antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects.

Related: Lawmakers Urge VA to Reform Medical Marijuana Rules

From the data, they also found cannabinoid receptor agonists may be useful as low-toxic agents, especially for patients who are “heavily pretreated,” elderly, or have refractory disease. Evidence was cited that THC retained antileukemic activity in a sample from a patient with otherwise chemotherapy- and steroid-refractory acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL).

Related: Veterans’ Use of Designer Cathinones and Cannabinoids

Due to the excellent safety profile of THC, the researchers say, effective doses are achievable in vivo, although tolerable doses may vary widely. They suggest starting with a subeffective dose and increasing gradually, which will help the patient build tolerance to the well-known psychoactive effects, which have been a drawback to widespread use of THC for patients with cancer.

They add that, due to sparse densities of cannabinoid receptors in lower brain stem areas, severe intoxications with THC rarely have been reported.

Related: Surgeon General Murthy Discusses Marijuana Efficacy

In addition to the direct antileukemic effects, the researchers suggest that therapeutic use of THC has many desirable adverse effects, such as general physical well-being, cachexia control, and relief of pain, anxiety and stress—which, they note, should “facilitate the decision process.”

Source:

Kampa-Schittenhelm KM, Salitzky O, Akmut F, et al. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(25)1-12.

doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-2029.

Researchers from University Hospital Tübingen, Germany, say that although the data for treating acute leukemia with dronabinol (THC), a cannabinoid derivative, are “controversial,” it has been shown to have antitumor potential for several cancers. When the researchers tested THC in several leukemia cell lines and native leukemia blasts cultured ex vivo, they found “meaningful” antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects.

Related: Lawmakers Urge VA to Reform Medical Marijuana Rules

From the data, they also found cannabinoid receptor agonists may be useful as low-toxic agents, especially for patients who are “heavily pretreated,” elderly, or have refractory disease. Evidence was cited that THC retained antileukemic activity in a sample from a patient with otherwise chemotherapy- and steroid-refractory acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL).

Related: Veterans’ Use of Designer Cathinones and Cannabinoids

Due to the excellent safety profile of THC, the researchers say, effective doses are achievable in vivo, although tolerable doses may vary widely. They suggest starting with a subeffective dose and increasing gradually, which will help the patient build tolerance to the well-known psychoactive effects, which have been a drawback to widespread use of THC for patients with cancer.

They add that, due to sparse densities of cannabinoid receptors in lower brain stem areas, severe intoxications with THC rarely have been reported.

Related: Surgeon General Murthy Discusses Marijuana Efficacy

In addition to the direct antileukemic effects, the researchers suggest that therapeutic use of THC has many desirable adverse effects, such as general physical well-being, cachexia control, and relief of pain, anxiety and stress—which, they note, should “facilitate the decision process.”

Source:

Kampa-Schittenhelm KM, Salitzky O, Akmut F, et al. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(25)1-12.

doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-2029.

Researchers from University Hospital Tübingen, Germany, say that although the data for treating acute leukemia with dronabinol (THC), a cannabinoid derivative, are “controversial,” it has been shown to have antitumor potential for several cancers. When the researchers tested THC in several leukemia cell lines and native leukemia blasts cultured ex vivo, they found “meaningful” antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects.

Related: Lawmakers Urge VA to Reform Medical Marijuana Rules

From the data, they also found cannabinoid receptor agonists may be useful as low-toxic agents, especially for patients who are “heavily pretreated,” elderly, or have refractory disease. Evidence was cited that THC retained antileukemic activity in a sample from a patient with otherwise chemotherapy- and steroid-refractory acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL).

Related: Veterans’ Use of Designer Cathinones and Cannabinoids

Due to the excellent safety profile of THC, the researchers say, effective doses are achievable in vivo, although tolerable doses may vary widely. They suggest starting with a subeffective dose and increasing gradually, which will help the patient build tolerance to the well-known psychoactive effects, which have been a drawback to widespread use of THC for patients with cancer.

They add that, due to sparse densities of cannabinoid receptors in lower brain stem areas, severe intoxications with THC rarely have been reported.

Related: Surgeon General Murthy Discusses Marijuana Efficacy

In addition to the direct antileukemic effects, the researchers suggest that therapeutic use of THC has many desirable adverse effects, such as general physical well-being, cachexia control, and relief of pain, anxiety and stress—which, they note, should “facilitate the decision process.”

Source:

Kampa-Schittenhelm KM, Salitzky O, Akmut F, et al. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(25)1-12.

doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-2029.

Bert Vargas, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

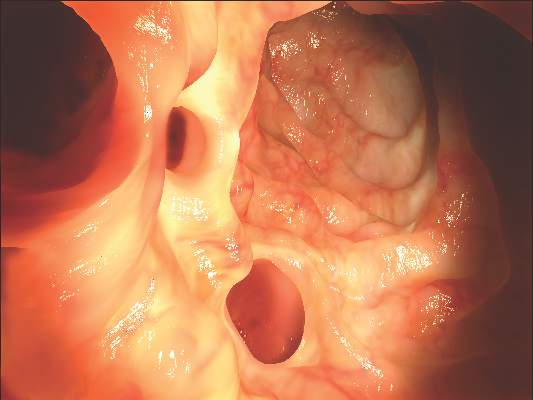

Early elective colon resection common in diverticulitis

A significant number of elective colon resections for uncomplicated diverticulitis are done in individuals who have experienced fewer than three episodes.

Researchers analyzed nationwide data from 87,461 immunocompetent patients with at least one claim for diverticulitis, of whom 5,604 (6.4%) underwent a resection.

According to a paper published online Feb. 10 in JAMA Surgery, 94.9% of resections, in a final cohort of 3,054 patients, occurred in individuals with fewer than three episodes of diverticulitis, if only inpatient claims were counted (doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5478).

If both inpatient and outpatient claims for diverticulitis were counted, 80.5% of patients who underwent resection had experienced fewer than three episodes, and if all types of claims (including antibiotic prescription claims for diverticulitis) were counted, that figure dropped to 56.3%.

Individuals who underwent early resection were slightly more likely to be male (risk ratio [RR], 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.13; P = .004) but were of a similar age to those who underwent resection after three or more episodes of diverticulitis.

The mean time between the last two episodes of diverticulitis was longer in individuals who underwent early surgery compared to those who delayed surgery (157 days vs. 96 days; P less than .001).

Patients residing in the South were also significantly more likely to undergo early surgery than were those residing in an other regions, with 60.5% of policy holders there undergoing early surgery compared to 50.7% in the West.

Insurance status also influenced the likelihood of early surgery, as patients with HMO or capitated insurance plans were less likely to undergo early surgery than were patients with other plan types.

In the last decade, professional guidelines have moved toward recommending elective surgery for diverticulitis after three or more episodes, but at the same time, the incidence of elective resection has more than doubled, reported Dr. Vlad V. Simianu of the University of Washington, Seattle, and coauthors.

This study covered a period of data in which guidelines on elective resection have remained in a relatively steady state, offering an opportunity to assess guideline adherence.

“Within this context, the suspected drivers of early elective surgery (younger age, laparoscopy, more frequent episodes, and personal financial risk) were not found to be associated with earlier operations for diverticulitis,” the authors wrote.

The analysis found laparoscopy was not associated with early surgery, which the authors said challenged the hypothesis that the threshold for early surgical resection might be lowered by the availability of laparoscopy.

The lack of an age difference between those undergoing early resection also challenged the notion that younger patients may experience more severe diverticulitis and suffer a greater impact on their quality of life and that this may drive physicians to operate earlier.

The authors noted that patient factors such as quality of life and anxiety about future episodes of diverticulitis, and surgeon-related factors such as training, local practice, and referral patterns were not tested, and that these may account for some of decisions about early surgery.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the University of Washington supported the study. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A significant number of elective colon resections for uncomplicated diverticulitis are done in individuals who have experienced fewer than three episodes.

Researchers analyzed nationwide data from 87,461 immunocompetent patients with at least one claim for diverticulitis, of whom 5,604 (6.4%) underwent a resection.

According to a paper published online Feb. 10 in JAMA Surgery, 94.9% of resections, in a final cohort of 3,054 patients, occurred in individuals with fewer than three episodes of diverticulitis, if only inpatient claims were counted (doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5478).

If both inpatient and outpatient claims for diverticulitis were counted, 80.5% of patients who underwent resection had experienced fewer than three episodes, and if all types of claims (including antibiotic prescription claims for diverticulitis) were counted, that figure dropped to 56.3%.

Individuals who underwent early resection were slightly more likely to be male (risk ratio [RR], 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.13; P = .004) but were of a similar age to those who underwent resection after three or more episodes of diverticulitis.

The mean time between the last two episodes of diverticulitis was longer in individuals who underwent early surgery compared to those who delayed surgery (157 days vs. 96 days; P less than .001).