User login

Gastrointestinal and liver diseases remain substantial public health burden

Diseases such as Clostridium difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver cancer continue to cost billions and cause many thousands of deaths in the United States every year, investigators reported in the December issue of Gastroenterology.

“Gastrointestinal and liver diseases are a source of substantial burden and cost,” said Dr. Anne Peery and her associates at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and the Gillings School of Public Health, both in Chapel Hill. The Affordable Care Act has extended health insurance to more than 16 million Americans, which is “expected to change the landscape of care for GI illnesses” and intensifies the need for their comprehensive study, the researchers added.

They analyzed health care visits, costs, and deaths from GI, pancreatic, and hepatic diseases for 2007 through 2012 by using surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Cancer Institute. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection was a leading disease burden, they found. Associated emergency department visits rose by 176% between 2006 and 2012, hospital admissions increased by 225% between 2003 and 2012, and in-hospital mortality approached 6%. These trends reflect the aging of baby boomers, who make up three-quarters of infected patients, the investigators noted. As a result, rates of new liver cancers also are rising, and end-stage liver disease is expected to keep increasing until 2030, they added (Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045). Aging boomers are increasingly seeking care for other age-related GI disorders, the investigators reported. Outpatient visits for hemorrhoids are rising, as are emergency department visits for constipation and lower-GI bleeding, and hospitalizations for acute diverticulitis and C. difficile infection. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage was the most common diagnosis at hospitalization, accounting for more than 500,000 discharges and costing almost $5 billion dollars in 2012 alone, the researchers said.

Despite better treatments, hospital admissions for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis also rose from less than 60,000 in 1993 to about 100,000 in 2012, said Dr. Peery and her associates. “This is congruent with earlier trends using the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Emergency department visits [for inflammatory bowel disease] are also rising,” they added.

In contrast, cases and deaths from colorectal cancer continue to drop, partly because of intensified screening efforts, the investigators said. They called the trend “encouraging,” but noted that CRC still tops cancers of the pancreas, liver, and intrahepatic bile ducts as the leading GI cause of mortality in the United States. In 2012, more than 51,000 Americans died from CRC, and screening efforts captured only 58% of those between 50 and 75 years old. Boosting that percentage to 80% by 2018 http://nccrt.org/tools/80-percent-by-2018/ could prevent 280,000 CRC cases and 200,000 deaths within 20 years, Dr. Peery and her associates noted.

The National Institutes of Health helped fund the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

In the excellent study by Peery and colleagues, statistics on health care utilization in the ambulatory and hospital settings, incidence and mortality from GI cancers, and mortality associated with other GI illnesses from 2007 to 2012 was collected using data from multiple complementary databases. This is the ideal methodology for this type of study because it quantifies utilization data from several complementary national databases. Of course, these data may be limited by systematic errors in ICD coding and costs are estimated using Medicare’s cost-to-charge ratio. Nevertheless, these data provide the best “snap shot” of trends in the burden of gastrointestinal and liver illness as of 2012.

What are the key points? First, the increase in the burden of GI and liver illness probably reflects the aging of the “baby boomer” population. Furthermore, since the Affordable Care Act is expanding access to health care, the burden on gastroenterologists is also likely to expand. Second, although we’re doing a good job with CRC screening, there is also room for improvement. While the incidence of CRC continues to decrease, only 58% of adults aged 50-75 years old had CRC screening in 2010. Third, HCV-associated hospitalizations have doubled from 2003 to 2012. Since HCV-associated cirrhosis is likely to increase until 2030, insurers and public health officials will have to carefully weigh the initial high cost of using new and highly effective regimens of direct-acting antiviral agents versus the downstream costs of managing these individuals after developing decompensated cirrhosis.

Dr. Philip S. Schoenfeld is professor of medicine and director, training program in GI epidemiology, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest.

In the excellent study by Peery and colleagues, statistics on health care utilization in the ambulatory and hospital settings, incidence and mortality from GI cancers, and mortality associated with other GI illnesses from 2007 to 2012 was collected using data from multiple complementary databases. This is the ideal methodology for this type of study because it quantifies utilization data from several complementary national databases. Of course, these data may be limited by systematic errors in ICD coding and costs are estimated using Medicare’s cost-to-charge ratio. Nevertheless, these data provide the best “snap shot” of trends in the burden of gastrointestinal and liver illness as of 2012.

What are the key points? First, the increase in the burden of GI and liver illness probably reflects the aging of the “baby boomer” population. Furthermore, since the Affordable Care Act is expanding access to health care, the burden on gastroenterologists is also likely to expand. Second, although we’re doing a good job with CRC screening, there is also room for improvement. While the incidence of CRC continues to decrease, only 58% of adults aged 50-75 years old had CRC screening in 2010. Third, HCV-associated hospitalizations have doubled from 2003 to 2012. Since HCV-associated cirrhosis is likely to increase until 2030, insurers and public health officials will have to carefully weigh the initial high cost of using new and highly effective regimens of direct-acting antiviral agents versus the downstream costs of managing these individuals after developing decompensated cirrhosis.

Dr. Philip S. Schoenfeld is professor of medicine and director, training program in GI epidemiology, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest.

In the excellent study by Peery and colleagues, statistics on health care utilization in the ambulatory and hospital settings, incidence and mortality from GI cancers, and mortality associated with other GI illnesses from 2007 to 2012 was collected using data from multiple complementary databases. This is the ideal methodology for this type of study because it quantifies utilization data from several complementary national databases. Of course, these data may be limited by systematic errors in ICD coding and costs are estimated using Medicare’s cost-to-charge ratio. Nevertheless, these data provide the best “snap shot” of trends in the burden of gastrointestinal and liver illness as of 2012.

What are the key points? First, the increase in the burden of GI and liver illness probably reflects the aging of the “baby boomer” population. Furthermore, since the Affordable Care Act is expanding access to health care, the burden on gastroenterologists is also likely to expand. Second, although we’re doing a good job with CRC screening, there is also room for improvement. While the incidence of CRC continues to decrease, only 58% of adults aged 50-75 years old had CRC screening in 2010. Third, HCV-associated hospitalizations have doubled from 2003 to 2012. Since HCV-associated cirrhosis is likely to increase until 2030, insurers and public health officials will have to carefully weigh the initial high cost of using new and highly effective regimens of direct-acting antiviral agents versus the downstream costs of managing these individuals after developing decompensated cirrhosis.

Dr. Philip S. Schoenfeld is professor of medicine and director, training program in GI epidemiology, division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest.

Diseases such as Clostridium difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver cancer continue to cost billions and cause many thousands of deaths in the United States every year, investigators reported in the December issue of Gastroenterology.

“Gastrointestinal and liver diseases are a source of substantial burden and cost,” said Dr. Anne Peery and her associates at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and the Gillings School of Public Health, both in Chapel Hill. The Affordable Care Act has extended health insurance to more than 16 million Americans, which is “expected to change the landscape of care for GI illnesses” and intensifies the need for their comprehensive study, the researchers added.

They analyzed health care visits, costs, and deaths from GI, pancreatic, and hepatic diseases for 2007 through 2012 by using surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Cancer Institute. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection was a leading disease burden, they found. Associated emergency department visits rose by 176% between 2006 and 2012, hospital admissions increased by 225% between 2003 and 2012, and in-hospital mortality approached 6%. These trends reflect the aging of baby boomers, who make up three-quarters of infected patients, the investigators noted. As a result, rates of new liver cancers also are rising, and end-stage liver disease is expected to keep increasing until 2030, they added (Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045). Aging boomers are increasingly seeking care for other age-related GI disorders, the investigators reported. Outpatient visits for hemorrhoids are rising, as are emergency department visits for constipation and lower-GI bleeding, and hospitalizations for acute diverticulitis and C. difficile infection. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage was the most common diagnosis at hospitalization, accounting for more than 500,000 discharges and costing almost $5 billion dollars in 2012 alone, the researchers said.

Despite better treatments, hospital admissions for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis also rose from less than 60,000 in 1993 to about 100,000 in 2012, said Dr. Peery and her associates. “This is congruent with earlier trends using the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Emergency department visits [for inflammatory bowel disease] are also rising,” they added.

In contrast, cases and deaths from colorectal cancer continue to drop, partly because of intensified screening efforts, the investigators said. They called the trend “encouraging,” but noted that CRC still tops cancers of the pancreas, liver, and intrahepatic bile ducts as the leading GI cause of mortality in the United States. In 2012, more than 51,000 Americans died from CRC, and screening efforts captured only 58% of those between 50 and 75 years old. Boosting that percentage to 80% by 2018 http://nccrt.org/tools/80-percent-by-2018/ could prevent 280,000 CRC cases and 200,000 deaths within 20 years, Dr. Peery and her associates noted.

The National Institutes of Health helped fund the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Diseases such as Clostridium difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver cancer continue to cost billions and cause many thousands of deaths in the United States every year, investigators reported in the December issue of Gastroenterology.

“Gastrointestinal and liver diseases are a source of substantial burden and cost,” said Dr. Anne Peery and her associates at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and the Gillings School of Public Health, both in Chapel Hill. The Affordable Care Act has extended health insurance to more than 16 million Americans, which is “expected to change the landscape of care for GI illnesses” and intensifies the need for their comprehensive study, the researchers added.

They analyzed health care visits, costs, and deaths from GI, pancreatic, and hepatic diseases for 2007 through 2012 by using surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Cancer Institute. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection was a leading disease burden, they found. Associated emergency department visits rose by 176% between 2006 and 2012, hospital admissions increased by 225% between 2003 and 2012, and in-hospital mortality approached 6%. These trends reflect the aging of baby boomers, who make up three-quarters of infected patients, the investigators noted. As a result, rates of new liver cancers also are rising, and end-stage liver disease is expected to keep increasing until 2030, they added (Gastroenterology. 2015 Aug 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045). Aging boomers are increasingly seeking care for other age-related GI disorders, the investigators reported. Outpatient visits for hemorrhoids are rising, as are emergency department visits for constipation and lower-GI bleeding, and hospitalizations for acute diverticulitis and C. difficile infection. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage was the most common diagnosis at hospitalization, accounting for more than 500,000 discharges and costing almost $5 billion dollars in 2012 alone, the researchers said.

Despite better treatments, hospital admissions for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis also rose from less than 60,000 in 1993 to about 100,000 in 2012, said Dr. Peery and her associates. “This is congruent with earlier trends using the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Emergency department visits [for inflammatory bowel disease] are also rising,” they added.

In contrast, cases and deaths from colorectal cancer continue to drop, partly because of intensified screening efforts, the investigators said. They called the trend “encouraging,” but noted that CRC still tops cancers of the pancreas, liver, and intrahepatic bile ducts as the leading GI cause of mortality in the United States. In 2012, more than 51,000 Americans died from CRC, and screening efforts captured only 58% of those between 50 and 75 years old. Boosting that percentage to 80% by 2018 http://nccrt.org/tools/80-percent-by-2018/ could prevent 280,000 CRC cases and 200,000 deaths within 20 years, Dr. Peery and her associates noted.

The National Institutes of Health helped fund the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Gastrointestinal and liver diseases remain a major cause of health care utilization and associated costs in the United States.

Major finding: Hospital admissions and associated costs for Clostridium difficile infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver disease all rose substantially between 1993 and 2012.

Data source: Analysis of surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and National Cancer Institute.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health helped fund the work. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Prognostic Disclosures Benefit Cancer Patients

When doctors discuss prognosis with advanced cancer patients, those patients have more realistic views of their life expectancy and don't seem to experience a decrease in emotional wellbeing, according to a new study.

"That the vast majority of cancer patients who are dying say that they want to know their prognosis seems surprisingly courageous," said senior author Holly G. Prigerson of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City.

Every patient needs to know their prognosis, including life expectancy, and expected outcomes of treatment; for example, they should know that chemotherapy cannot cure incurable cancer, Prigerson said.

"Providers often are reluctant to communicate grim news, as anyone would be," she said.

The study included 590 patients with advanced, metastatic cancer who had been treated with at least one round of palliative chemotherapy, which is meant to improve comfort rather than to cure.

Researchers asked the patients whether their oncologist had ever given them a prognosis with a life expectancy estimate, then asked the patients to estimate their own life expectancy and to complete assessments of emotional distress, whether they had advance directives and their end-of-life care preferences.

The patients also described their relationship with their doctors.

Half of the patients survived for less than six months after the study began.

About 70 percent wanted to be told their life expectancy, but only about 18 percent recalled having this discussion with their oncologist.

Half of the patients were willing to estimate their own life expectancy, and those who remembered having a prognosis conversation with their doctor estimated a life expectancy closer to their actual survival than those who did not.

Less than 10 percent of those who remembered having a conversation with their doctor made estimates that were more than five years longer than their actual survival. That compares with 35 percent of those who did not remember having the conversation who overestimated their life expectancy by more than five years.

Remembering a prognostic discussion with a doctor decreased patient estimated life expectancy by about 17 months, when the researchers accounted for other factors, according to the results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Talking to a doctor about life expectancy was not tied to worse doctor-patient relationship, more sadness or higher anxiety, the surveys found.

"It is encouraging that the patients who reported a prognostic disclosure by their oncologist were more realistic in their life-expectancy estimate, more likely to complete a [Do Not Resuscitate] order and to want comfort care," Prigerson said by email.

"There was no emotional fallout that damaged their relationship with their oncologist - as reported by the patient," she said.

Often these conversations should happen, but they do not, for a multitude of reasons, she said. The patient may not be ready to hear bad news, some patients may reject information they are given because they believe a miracle may happen, and other reasons, she said.

"Some patients are not able to hear and process poor prognoses and more harm than good can be done by forcing the situation," Prigerson said. "However, we have found that over 90 percent of patients benefit from prognostic disclosures and it is a minority of patients for religious or personal or social reasons that do not benefit."

When doctors discuss prognosis with advanced cancer patients, those patients have more realistic views of their life expectancy and don't seem to experience a decrease in emotional wellbeing, according to a new study.

"That the vast majority of cancer patients who are dying say that they want to know their prognosis seems surprisingly courageous," said senior author Holly G. Prigerson of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City.

Every patient needs to know their prognosis, including life expectancy, and expected outcomes of treatment; for example, they should know that chemotherapy cannot cure incurable cancer, Prigerson said.

"Providers often are reluctant to communicate grim news, as anyone would be," she said.

The study included 590 patients with advanced, metastatic cancer who had been treated with at least one round of palliative chemotherapy, which is meant to improve comfort rather than to cure.

Researchers asked the patients whether their oncologist had ever given them a prognosis with a life expectancy estimate, then asked the patients to estimate their own life expectancy and to complete assessments of emotional distress, whether they had advance directives and their end-of-life care preferences.

The patients also described their relationship with their doctors.

Half of the patients survived for less than six months after the study began.

About 70 percent wanted to be told their life expectancy, but only about 18 percent recalled having this discussion with their oncologist.

Half of the patients were willing to estimate their own life expectancy, and those who remembered having a prognosis conversation with their doctor estimated a life expectancy closer to their actual survival than those who did not.

Less than 10 percent of those who remembered having a conversation with their doctor made estimates that were more than five years longer than their actual survival. That compares with 35 percent of those who did not remember having the conversation who overestimated their life expectancy by more than five years.

Remembering a prognostic discussion with a doctor decreased patient estimated life expectancy by about 17 months, when the researchers accounted for other factors, according to the results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Talking to a doctor about life expectancy was not tied to worse doctor-patient relationship, more sadness or higher anxiety, the surveys found.

"It is encouraging that the patients who reported a prognostic disclosure by their oncologist were more realistic in their life-expectancy estimate, more likely to complete a [Do Not Resuscitate] order and to want comfort care," Prigerson said by email.

"There was no emotional fallout that damaged their relationship with their oncologist - as reported by the patient," she said.

Often these conversations should happen, but they do not, for a multitude of reasons, she said. The patient may not be ready to hear bad news, some patients may reject information they are given because they believe a miracle may happen, and other reasons, she said.

"Some patients are not able to hear and process poor prognoses and more harm than good can be done by forcing the situation," Prigerson said. "However, we have found that over 90 percent of patients benefit from prognostic disclosures and it is a minority of patients for religious or personal or social reasons that do not benefit."

When doctors discuss prognosis with advanced cancer patients, those patients have more realistic views of their life expectancy and don't seem to experience a decrease in emotional wellbeing, according to a new study.

"That the vast majority of cancer patients who are dying say that they want to know their prognosis seems surprisingly courageous," said senior author Holly G. Prigerson of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City.

Every patient needs to know their prognosis, including life expectancy, and expected outcomes of treatment; for example, they should know that chemotherapy cannot cure incurable cancer, Prigerson said.

"Providers often are reluctant to communicate grim news, as anyone would be," she said.

The study included 590 patients with advanced, metastatic cancer who had been treated with at least one round of palliative chemotherapy, which is meant to improve comfort rather than to cure.

Researchers asked the patients whether their oncologist had ever given them a prognosis with a life expectancy estimate, then asked the patients to estimate their own life expectancy and to complete assessments of emotional distress, whether they had advance directives and their end-of-life care preferences.

The patients also described their relationship with their doctors.

Half of the patients survived for less than six months after the study began.

About 70 percent wanted to be told their life expectancy, but only about 18 percent recalled having this discussion with their oncologist.

Half of the patients were willing to estimate their own life expectancy, and those who remembered having a prognosis conversation with their doctor estimated a life expectancy closer to their actual survival than those who did not.

Less than 10 percent of those who remembered having a conversation with their doctor made estimates that were more than five years longer than their actual survival. That compares with 35 percent of those who did not remember having the conversation who overestimated their life expectancy by more than five years.

Remembering a prognostic discussion with a doctor decreased patient estimated life expectancy by about 17 months, when the researchers accounted for other factors, according to the results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Talking to a doctor about life expectancy was not tied to worse doctor-patient relationship, more sadness or higher anxiety, the surveys found.

"It is encouraging that the patients who reported a prognostic disclosure by their oncologist were more realistic in their life-expectancy estimate, more likely to complete a [Do Not Resuscitate] order and to want comfort care," Prigerson said by email.

"There was no emotional fallout that damaged their relationship with their oncologist - as reported by the patient," she said.

Often these conversations should happen, but they do not, for a multitude of reasons, she said. The patient may not be ready to hear bad news, some patients may reject information they are given because they believe a miracle may happen, and other reasons, she said.

"Some patients are not able to hear and process poor prognoses and more harm than good can be done by forcing the situation," Prigerson said. "However, we have found that over 90 percent of patients benefit from prognostic disclosures and it is a minority of patients for religious or personal or social reasons that do not benefit."

High free thyroxine may increase risk of sudden cardiac death

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – High levels of free thyroxine (T4) can double the risk of sudden cardiac death, a large cohort study has determined.

Even people with free T4 in the upper range of normal may face an increased risk – up to 4% over 10 years, Dr. Layal Chaker said at the International Thyroid Conference.

The association remained significant, even when researchers controlled for independent cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and hyperlipidemia, said Dr. Chaker of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The findings were based on a 9-year analysis of about 10,000 people included in the Rotterdam Elderly Study, conducted from 1990 to 2008. That study followed 15,000 people from middle age to old age, assessing cardiovascular and neurological diseases and their relationship to aging.

Dr. Chaker’s study comprised a subset of those who were without frank cardiovascular disease at baseline. She defined sudden cardiac death as a natural death from cardiac causes, heralded by an abrupt loss of consciousness within an hour of the onset of acute symptoms. Unwitnessed deaths were also included in the analysis. All of the death records were reviewed by two clinicians and a senior cardiologist.

The cohort comprised 10,318 subjects who had measurements of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (free T4); the mean age was 65 years.

Dr. Chaker stratified the group into tertiles based on the levels of these biomarkers. She conducted a multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, pulse, hypertension, cholesterol levels, diabetes, body mass index, smoking, and QT interval.

There were 261 sudden cardiac deaths by the end of follow-up.

There was no significant relationship between any level of TSH and sudden cardiac death. However, when she assessed the deaths by tertiles of free T4, she found a significant 40% increase in the risk among those whose levels ranged from 1.29 to 4 ng/L. The absolute 10-year risk rose from 1% at the lowest tertile to 7% in the highest.

Dr. Chaker then included only patients whose free T4 levels were in the euthyroid range of 0.85-1.95 ng/L. Among these, the risk of sudden cardiac death increased as free T4 increased (hazard ratio [HR], 2.25 for the highest level). The absolute 10-year risk rose from 1% at the lowest euthyroid level to 4% at 1.95 ng/L.

The reason for this finding isn’t completely clear, although other studies have shown a relationship between cardiac problems and thyroid function, she said.

“There may be some hemodynamic abnormalities that go along with even subclinical hyperthyroidism. High free T4 also has been associated with atrial fibrillation; both subclinical hyper- and hypothyroidism are associated with a prolongation of the QT interval.”

The meeting was held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society. Dr. Chaker had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – High levels of free thyroxine (T4) can double the risk of sudden cardiac death, a large cohort study has determined.

Even people with free T4 in the upper range of normal may face an increased risk – up to 4% over 10 years, Dr. Layal Chaker said at the International Thyroid Conference.

The association remained significant, even when researchers controlled for independent cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and hyperlipidemia, said Dr. Chaker of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The findings were based on a 9-year analysis of about 10,000 people included in the Rotterdam Elderly Study, conducted from 1990 to 2008. That study followed 15,000 people from middle age to old age, assessing cardiovascular and neurological diseases and their relationship to aging.

Dr. Chaker’s study comprised a subset of those who were without frank cardiovascular disease at baseline. She defined sudden cardiac death as a natural death from cardiac causes, heralded by an abrupt loss of consciousness within an hour of the onset of acute symptoms. Unwitnessed deaths were also included in the analysis. All of the death records were reviewed by two clinicians and a senior cardiologist.

The cohort comprised 10,318 subjects who had measurements of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (free T4); the mean age was 65 years.

Dr. Chaker stratified the group into tertiles based on the levels of these biomarkers. She conducted a multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, pulse, hypertension, cholesterol levels, diabetes, body mass index, smoking, and QT interval.

There were 261 sudden cardiac deaths by the end of follow-up.

There was no significant relationship between any level of TSH and sudden cardiac death. However, when she assessed the deaths by tertiles of free T4, she found a significant 40% increase in the risk among those whose levels ranged from 1.29 to 4 ng/L. The absolute 10-year risk rose from 1% at the lowest tertile to 7% in the highest.

Dr. Chaker then included only patients whose free T4 levels were in the euthyroid range of 0.85-1.95 ng/L. Among these, the risk of sudden cardiac death increased as free T4 increased (hazard ratio [HR], 2.25 for the highest level). The absolute 10-year risk rose from 1% at the lowest euthyroid level to 4% at 1.95 ng/L.

The reason for this finding isn’t completely clear, although other studies have shown a relationship between cardiac problems and thyroid function, she said.

“There may be some hemodynamic abnormalities that go along with even subclinical hyperthyroidism. High free T4 also has been associated with atrial fibrillation; both subclinical hyper- and hypothyroidism are associated with a prolongation of the QT interval.”

The meeting was held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society. Dr. Chaker had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – High levels of free thyroxine (T4) can double the risk of sudden cardiac death, a large cohort study has determined.

Even people with free T4 in the upper range of normal may face an increased risk – up to 4% over 10 years, Dr. Layal Chaker said at the International Thyroid Conference.

The association remained significant, even when researchers controlled for independent cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and hyperlipidemia, said Dr. Chaker of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

The findings were based on a 9-year analysis of about 10,000 people included in the Rotterdam Elderly Study, conducted from 1990 to 2008. That study followed 15,000 people from middle age to old age, assessing cardiovascular and neurological diseases and their relationship to aging.

Dr. Chaker’s study comprised a subset of those who were without frank cardiovascular disease at baseline. She defined sudden cardiac death as a natural death from cardiac causes, heralded by an abrupt loss of consciousness within an hour of the onset of acute symptoms. Unwitnessed deaths were also included in the analysis. All of the death records were reviewed by two clinicians and a senior cardiologist.

The cohort comprised 10,318 subjects who had measurements of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (free T4); the mean age was 65 years.

Dr. Chaker stratified the group into tertiles based on the levels of these biomarkers. She conducted a multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, pulse, hypertension, cholesterol levels, diabetes, body mass index, smoking, and QT interval.

There were 261 sudden cardiac deaths by the end of follow-up.

There was no significant relationship between any level of TSH and sudden cardiac death. However, when she assessed the deaths by tertiles of free T4, she found a significant 40% increase in the risk among those whose levels ranged from 1.29 to 4 ng/L. The absolute 10-year risk rose from 1% at the lowest tertile to 7% in the highest.

Dr. Chaker then included only patients whose free T4 levels were in the euthyroid range of 0.85-1.95 ng/L. Among these, the risk of sudden cardiac death increased as free T4 increased (hazard ratio [HR], 2.25 for the highest level). The absolute 10-year risk rose from 1% at the lowest euthyroid level to 4% at 1.95 ng/L.

The reason for this finding isn’t completely clear, although other studies have shown a relationship between cardiac problems and thyroid function, she said.

“There may be some hemodynamic abnormalities that go along with even subclinical hyperthyroidism. High free T4 also has been associated with atrial fibrillation; both subclinical hyper- and hypothyroidism are associated with a prolongation of the QT interval.”

The meeting was held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society. Dr. Chaker had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT ITC 2015

Key clinical point: Even subclinical hyperthyroidism may increase the risk of sudden cardiac death.

Major finding: High free thyroxine in euthyroid patients doubled the risk of sudden cardiac death.

Data source: A longitudinal cohort study comprising 10,318 subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Chaker had no financial disclosures.

Derm Morphology, Part 1

1. Raised, often itchy, red bumps on the surface of the skin, usually from an allergic reaction.

Diagnosis: Hives/Wheals

For more information on this case, see “Inexperienced runner develops leg rash.” Clin Rev. 2012;22(8):W3.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

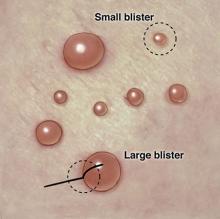

2. Large and small clear-fluid-filled blisters.

Diagnosis: Bullae/Vesicles

For more information, see “High-Yield Biopsy Technique for Subepidermal Blisters.” Cutis. 2015 April;95(ISSUE):4.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

3. Small, inflamed, pus-filled, blister-like lesions on the skin surface, commonly found in acne.

Diagnosis: Pustules

For more information on this case, see “Neonatal and Infantile Acne Vulgaris: An Update.” Cutis. 2014 July;94(1):13-16.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

4. Solid or cystic raised bumps wider than 1 cm but less than 2 cm.

Diagnosis: Nodules

For more information on this case, see “Lesion Has Doubled in Size in Two Weeks.” Clin Rev. 2009;19(10):2.

1. Raised, often itchy, red bumps on the surface of the skin, usually from an allergic reaction.

Diagnosis: Hives/Wheals

For more information on this case, see “Inexperienced runner develops leg rash.” Clin Rev. 2012;22(8):W3.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

2. Large and small clear-fluid-filled blisters.

Diagnosis: Bullae/Vesicles

For more information, see “High-Yield Biopsy Technique for Subepidermal Blisters.” Cutis. 2015 April;95(ISSUE):4.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

3. Small, inflamed, pus-filled, blister-like lesions on the skin surface, commonly found in acne.

Diagnosis: Pustules

For more information on this case, see “Neonatal and Infantile Acne Vulgaris: An Update.” Cutis. 2014 July;94(1):13-16.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

4. Solid or cystic raised bumps wider than 1 cm but less than 2 cm.

Diagnosis: Nodules

For more information on this case, see “Lesion Has Doubled in Size in Two Weeks.” Clin Rev. 2009;19(10):2.

1. Raised, often itchy, red bumps on the surface of the skin, usually from an allergic reaction.

Diagnosis: Hives/Wheals

For more information on this case, see “Inexperienced runner develops leg rash.” Clin Rev. 2012;22(8):W3.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

2. Large and small clear-fluid-filled blisters.

Diagnosis: Bullae/Vesicles

For more information, see “High-Yield Biopsy Technique for Subepidermal Blisters.” Cutis. 2015 April;95(ISSUE):4.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

3. Small, inflamed, pus-filled, blister-like lesions on the skin surface, commonly found in acne.

Diagnosis: Pustules

For more information on this case, see “Neonatal and Infantile Acne Vulgaris: An Update.” Cutis. 2014 July;94(1):13-16.

For the next photograph, proceed to the next page >>

4. Solid or cystic raised bumps wider than 1 cm but less than 2 cm.

Diagnosis: Nodules

For more information on this case, see “Lesion Has Doubled in Size in Two Weeks.” Clin Rev. 2009;19(10):2.

Assay can detect and classify DOACs

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

ANAHEIM, CA—A new assay can detect and classify direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) quickly and effectively, according to researchers.

In tests, the assay detected DOACs with greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity.

The assay classified the direct thrombin inhibitor (DTI) dabigatran correctly 100% of the time and classified factor Xa inhibitors (anti-Xa), which included rivaroxaban and apixaban, correctly 92% of the time.

The researchers believe this assay has the potential to be an effective tool for treating patients on DOACs who experience trauma or stroke, as well as those who require emergency/urgent surgery. And the ability to identify the type of anticoagulant a patient is taking can guide the reversal strategy.

Fowzia Zaman, PhD, of Haemonetics Corporation in Rosemont, Illinois, described the assay at the 2015 AABB Annual Meeting (abstract S60-030K). Haemonetics is the company developing the assay, and this research was supported by the company.

About the assay

“The current coagulation assays are not very sensitive to DOACs, especially in the therapeutic range,” Dr Zaman said. “Right now, there is no assay available that can classify the DOACs. This new assay can both detect and classify, and it will classify the DOACs either as a DTI or an anti-Xa.”

The assay is performed using Haemonetics’ TEG 6s system, a fully automated system for evaluating anticoagulation in a patient. It is based on viscoelasticity measurements using resonance frequency and disposable microfluidic cartridges. Each cartridge has 4 channels, and 2 of the channels are used for detection and classification.

Detection is performed using a factor Xa-based reagent, and classification utilizes an Ecarin-based reagent. All of the reagents are contained within the channel, so there is no reagent preparation required.

Each cartridge is loaded into the unit, and citrated whole blood is added, either with a transfer pipette or a syringe, to start the assay.

Reaction time (R-time) is used for detection and classification. R is defined as the time from the start of the sample run to the point of clot formation. It corresponds to an amplitude of 2 mm on the TEG tracing. It represents the initial enzymatic phase of clotting, and it is recorded in minutes.

Study population

The researchers tested the assay in 26 healthy subjects, 25 patients on DTI (all dabigatran), and 40 on anti-Xa therapy (24 on rivaroxaban, 16 on apixaban).

For healthy subjects, the mean age was 41±13, and 46% of subjects are male. Forty-six percent are Caucasian, 39% are African American, and 15% are Asian/“other”. The partial thromboplastin time (PTT) for these subjects was within the normal range, at 27.2±1.8 seconds.

In the DOAC population, the mean age was 68±12 for the anti-Xa group and 69±10 for the DTI group. Fifty percent and 72%, respectively, are male. And 50% and 64%, respectively, are Caucasian.

Most of the patients receiving DOACs were taking them for atrial fibrillation—88% in the anti-Xa group and 84% in the DTI group. Other underlying conditions were coronary artery disease—28% and 32%, respectively—and hypertension—60% and 64%, respectively.

Some patients were taking aspirin in addition to DOACs—30% in the anti-Xa group and 24% in the DTI group. And some were taking P2Y12 inhibitors—20% in the anti-Xa group and 24% in the DTI group.

The PTT was 30.4±4.6 seconds for the anti-Xa group and 36.6±7 seconds for the DTI group. Creatinine levels were 1.07±0.6 mg/dL and 1.05±0.2 mg/dL, respectively.

Assay results

The researchers analyzed citrated whole blood from the healthy volunteers to establish the baseline reference range. The cutoff for detection was 1.95 minutes, and the cutoff for classification was 1.9 minutes.

“What this means is that a person who does not have DOAC in their system should have an R-time of less than or equal to 1.95 minutes,” Dr Zaman explained.

The researchers also developed an algorithm for the detection and classification of DOACs. According to this algorithm, healthy subjects would have a short R-time in the detection channel and the classification channel.

Patients on anti-Xa would have a long R-time in the detection channel but a short R-time in the classification channel. And patients on a DTI would have a long R-time in both the detection channel and the classification channel.

The researchers found that, in the detection channel, on average, R-time was increased 66% for dabigatran, 125% for rivaroxaban, and 100% for apixaban, compared to the reference range. But the degree of elongation was dependent on the individual patient and the time from last DOAC dosage.

Using a cutoff of 2 minutes, the detection channel demonstrated 94% sensitivity and 96% specificity for all the DOACs combined.

“What this means is that, when a patient had a DOAC in their system, the assay was able to pick it up 94% of the time,” Dr Zaman explained.

In addition, the assay detected dabigatran correctly 100% of the time and anti-Xa therapy correctly 92% of the time.

“This TEG 6s DOAC assay is highly sensitive and specific for detecting and classifying DOACs,” Dr Zaman said in closing. “[T]he cutoffs for both the channels are close to 2 minutes, which means clinically relevant results are available within 5 minutes.”

“There is no reagent prep necessary, and it utilizes whole blood, so [there is] no spinning down to plasma. Therefore, it has the potential to be a point-of-care assay.” ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

ANAHEIM, CA—A new assay can detect and classify direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) quickly and effectively, according to researchers.

In tests, the assay detected DOACs with greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity.

The assay classified the direct thrombin inhibitor (DTI) dabigatran correctly 100% of the time and classified factor Xa inhibitors (anti-Xa), which included rivaroxaban and apixaban, correctly 92% of the time.

The researchers believe this assay has the potential to be an effective tool for treating patients on DOACs who experience trauma or stroke, as well as those who require emergency/urgent surgery. And the ability to identify the type of anticoagulant a patient is taking can guide the reversal strategy.

Fowzia Zaman, PhD, of Haemonetics Corporation in Rosemont, Illinois, described the assay at the 2015 AABB Annual Meeting (abstract S60-030K). Haemonetics is the company developing the assay, and this research was supported by the company.

About the assay

“The current coagulation assays are not very sensitive to DOACs, especially in the therapeutic range,” Dr Zaman said. “Right now, there is no assay available that can classify the DOACs. This new assay can both detect and classify, and it will classify the DOACs either as a DTI or an anti-Xa.”

The assay is performed using Haemonetics’ TEG 6s system, a fully automated system for evaluating anticoagulation in a patient. It is based on viscoelasticity measurements using resonance frequency and disposable microfluidic cartridges. Each cartridge has 4 channels, and 2 of the channels are used for detection and classification.

Detection is performed using a factor Xa-based reagent, and classification utilizes an Ecarin-based reagent. All of the reagents are contained within the channel, so there is no reagent preparation required.

Each cartridge is loaded into the unit, and citrated whole blood is added, either with a transfer pipette or a syringe, to start the assay.

Reaction time (R-time) is used for detection and classification. R is defined as the time from the start of the sample run to the point of clot formation. It corresponds to an amplitude of 2 mm on the TEG tracing. It represents the initial enzymatic phase of clotting, and it is recorded in minutes.

Study population

The researchers tested the assay in 26 healthy subjects, 25 patients on DTI (all dabigatran), and 40 on anti-Xa therapy (24 on rivaroxaban, 16 on apixaban).

For healthy subjects, the mean age was 41±13, and 46% of subjects are male. Forty-six percent are Caucasian, 39% are African American, and 15% are Asian/“other”. The partial thromboplastin time (PTT) for these subjects was within the normal range, at 27.2±1.8 seconds.

In the DOAC population, the mean age was 68±12 for the anti-Xa group and 69±10 for the DTI group. Fifty percent and 72%, respectively, are male. And 50% and 64%, respectively, are Caucasian.

Most of the patients receiving DOACs were taking them for atrial fibrillation—88% in the anti-Xa group and 84% in the DTI group. Other underlying conditions were coronary artery disease—28% and 32%, respectively—and hypertension—60% and 64%, respectively.

Some patients were taking aspirin in addition to DOACs—30% in the anti-Xa group and 24% in the DTI group. And some were taking P2Y12 inhibitors—20% in the anti-Xa group and 24% in the DTI group.

The PTT was 30.4±4.6 seconds for the anti-Xa group and 36.6±7 seconds for the DTI group. Creatinine levels were 1.07±0.6 mg/dL and 1.05±0.2 mg/dL, respectively.

Assay results

The researchers analyzed citrated whole blood from the healthy volunteers to establish the baseline reference range. The cutoff for detection was 1.95 minutes, and the cutoff for classification was 1.9 minutes.

“What this means is that a person who does not have DOAC in their system should have an R-time of less than or equal to 1.95 minutes,” Dr Zaman explained.

The researchers also developed an algorithm for the detection and classification of DOACs. According to this algorithm, healthy subjects would have a short R-time in the detection channel and the classification channel.

Patients on anti-Xa would have a long R-time in the detection channel but a short R-time in the classification channel. And patients on a DTI would have a long R-time in both the detection channel and the classification channel.

The researchers found that, in the detection channel, on average, R-time was increased 66% for dabigatran, 125% for rivaroxaban, and 100% for apixaban, compared to the reference range. But the degree of elongation was dependent on the individual patient and the time from last DOAC dosage.

Using a cutoff of 2 minutes, the detection channel demonstrated 94% sensitivity and 96% specificity for all the DOACs combined.

“What this means is that, when a patient had a DOAC in their system, the assay was able to pick it up 94% of the time,” Dr Zaman explained.

In addition, the assay detected dabigatran correctly 100% of the time and anti-Xa therapy correctly 92% of the time.

“This TEG 6s DOAC assay is highly sensitive and specific for detecting and classifying DOACs,” Dr Zaman said in closing. “[T]he cutoffs for both the channels are close to 2 minutes, which means clinically relevant results are available within 5 minutes.”

“There is no reagent prep necessary, and it utilizes whole blood, so [there is] no spinning down to plasma. Therefore, it has the potential to be a point-of-care assay.” ![]()

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

ANAHEIM, CA—A new assay can detect and classify direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) quickly and effectively, according to researchers.

In tests, the assay detected DOACs with greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity.

The assay classified the direct thrombin inhibitor (DTI) dabigatran correctly 100% of the time and classified factor Xa inhibitors (anti-Xa), which included rivaroxaban and apixaban, correctly 92% of the time.

The researchers believe this assay has the potential to be an effective tool for treating patients on DOACs who experience trauma or stroke, as well as those who require emergency/urgent surgery. And the ability to identify the type of anticoagulant a patient is taking can guide the reversal strategy.

Fowzia Zaman, PhD, of Haemonetics Corporation in Rosemont, Illinois, described the assay at the 2015 AABB Annual Meeting (abstract S60-030K). Haemonetics is the company developing the assay, and this research was supported by the company.

About the assay

“The current coagulation assays are not very sensitive to DOACs, especially in the therapeutic range,” Dr Zaman said. “Right now, there is no assay available that can classify the DOACs. This new assay can both detect and classify, and it will classify the DOACs either as a DTI or an anti-Xa.”

The assay is performed using Haemonetics’ TEG 6s system, a fully automated system for evaluating anticoagulation in a patient. It is based on viscoelasticity measurements using resonance frequency and disposable microfluidic cartridges. Each cartridge has 4 channels, and 2 of the channels are used for detection and classification.

Detection is performed using a factor Xa-based reagent, and classification utilizes an Ecarin-based reagent. All of the reagents are contained within the channel, so there is no reagent preparation required.

Each cartridge is loaded into the unit, and citrated whole blood is added, either with a transfer pipette or a syringe, to start the assay.

Reaction time (R-time) is used for detection and classification. R is defined as the time from the start of the sample run to the point of clot formation. It corresponds to an amplitude of 2 mm on the TEG tracing. It represents the initial enzymatic phase of clotting, and it is recorded in minutes.

Study population

The researchers tested the assay in 26 healthy subjects, 25 patients on DTI (all dabigatran), and 40 on anti-Xa therapy (24 on rivaroxaban, 16 on apixaban).

For healthy subjects, the mean age was 41±13, and 46% of subjects are male. Forty-six percent are Caucasian, 39% are African American, and 15% are Asian/“other”. The partial thromboplastin time (PTT) for these subjects was within the normal range, at 27.2±1.8 seconds.

In the DOAC population, the mean age was 68±12 for the anti-Xa group and 69±10 for the DTI group. Fifty percent and 72%, respectively, are male. And 50% and 64%, respectively, are Caucasian.

Most of the patients receiving DOACs were taking them for atrial fibrillation—88% in the anti-Xa group and 84% in the DTI group. Other underlying conditions were coronary artery disease—28% and 32%, respectively—and hypertension—60% and 64%, respectively.

Some patients were taking aspirin in addition to DOACs—30% in the anti-Xa group and 24% in the DTI group. And some were taking P2Y12 inhibitors—20% in the anti-Xa group and 24% in the DTI group.

The PTT was 30.4±4.6 seconds for the anti-Xa group and 36.6±7 seconds for the DTI group. Creatinine levels were 1.07±0.6 mg/dL and 1.05±0.2 mg/dL, respectively.

Assay results

The researchers analyzed citrated whole blood from the healthy volunteers to establish the baseline reference range. The cutoff for detection was 1.95 minutes, and the cutoff for classification was 1.9 minutes.

“What this means is that a person who does not have DOAC in their system should have an R-time of less than or equal to 1.95 minutes,” Dr Zaman explained.

The researchers also developed an algorithm for the detection and classification of DOACs. According to this algorithm, healthy subjects would have a short R-time in the detection channel and the classification channel.

Patients on anti-Xa would have a long R-time in the detection channel but a short R-time in the classification channel. And patients on a DTI would have a long R-time in both the detection channel and the classification channel.

The researchers found that, in the detection channel, on average, R-time was increased 66% for dabigatran, 125% for rivaroxaban, and 100% for apixaban, compared to the reference range. But the degree of elongation was dependent on the individual patient and the time from last DOAC dosage.

Using a cutoff of 2 minutes, the detection channel demonstrated 94% sensitivity and 96% specificity for all the DOACs combined.

“What this means is that, when a patient had a DOAC in their system, the assay was able to pick it up 94% of the time,” Dr Zaman explained.

In addition, the assay detected dabigatran correctly 100% of the time and anti-Xa therapy correctly 92% of the time.

“This TEG 6s DOAC assay is highly sensitive and specific for detecting and classifying DOACs,” Dr Zaman said in closing. “[T]he cutoffs for both the channels are close to 2 minutes, which means clinically relevant results are available within 5 minutes.”

“There is no reagent prep necessary, and it utilizes whole blood, so [there is] no spinning down to plasma. Therefore, it has the potential to be a point-of-care assay.” ![]()

MM-related ESRD on the decline

Photo by Anna Frodesiak

New research suggests the risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) caused by multiple myeloma (MM) is declining, and survival is lengthening for patients who do develop ESRD due to MM.

Researchers said these findings are encouraging, but efforts are still needed to develop effective MM treatments with fewer side effects.

They noted that MM treatment has changed substantially in the last decade.

But it hasn’t been clear whether the burden of ESRD due to MM has changed or whether survival has improved for patients with ESRD due to MM.

To gain some insight, Robert Foley, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and his colleagues examined data from the US Renal Data System database spanning the period from 2001 to 2010.

They reported their findings in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The team found that, of the 1,069,343 patients with ESRD who were on renal replacement therapy (RRT), 12,703 had developed ESRD due to MM.

However, the incidence of ESRD from MM decreased from 2001 to 2010. Compared to 2001-2002 (1.00), the standardized incidence ratios of ESRD due to MM were 0.96 for 2003-2004 (P<0.05), 0.99 for 2005-2006 (P>0.05), 0.89 for 2007-2008 (P<0.001), and 0.82 for 2009-2010 (P<0.001).

The demography-adjusted incidence ratio for ESRD due to MM decreased (P<0.05) between 2001-2002 and 2009-2010 in the overall population and in most of the subgroups examined.

The exceptions were patients younger than 40, Hispanic patients, and those belonging to the “other” race category. (The race categories were “white,” “black,” and “other,” while the ethnicity categories were “Hispanic” and “non-Hispanic.”)

The data also showed improvements in survival over time among patients with ESRD due to MM.

Compared to 2001-2002, the adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) for death were 1.02 for 2003-2004 (P=0.5), 0.93 for 2005-2006 (P=0.02), 0.86 for 2007-2008 (P<0.001), and 0.74 for 2009-2010 (P<0.001). (This analysis was adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, mode of RRT, estimated glomerular filtration rate, body mass index, serum albumin, and hemoglobin.)

AHRs for death were highest in the first year after RRT initiation (AHR=2.6; P<0.001) and decreased in year 3 (AHR=1.59; P<0.001).

The AHR for death in patients with ESRD due to MM compared to those with ESRD due to all other causes was 2.05 (P<0.001).

“Myeloma is the commonest malignancy leading to kidney failure,” Dr Foley said. “It’s encouraging that we found that kidney failure due to multiple myeloma declined considerably over the last decade.” ![]()

Photo by Anna Frodesiak

New research suggests the risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) caused by multiple myeloma (MM) is declining, and survival is lengthening for patients who do develop ESRD due to MM.

Researchers said these findings are encouraging, but efforts are still needed to develop effective MM treatments with fewer side effects.

They noted that MM treatment has changed substantially in the last decade.

But it hasn’t been clear whether the burden of ESRD due to MM has changed or whether survival has improved for patients with ESRD due to MM.

To gain some insight, Robert Foley, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and his colleagues examined data from the US Renal Data System database spanning the period from 2001 to 2010.

They reported their findings in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The team found that, of the 1,069,343 patients with ESRD who were on renal replacement therapy (RRT), 12,703 had developed ESRD due to MM.

However, the incidence of ESRD from MM decreased from 2001 to 2010. Compared to 2001-2002 (1.00), the standardized incidence ratios of ESRD due to MM were 0.96 for 2003-2004 (P<0.05), 0.99 for 2005-2006 (P>0.05), 0.89 for 2007-2008 (P<0.001), and 0.82 for 2009-2010 (P<0.001).

The demography-adjusted incidence ratio for ESRD due to MM decreased (P<0.05) between 2001-2002 and 2009-2010 in the overall population and in most of the subgroups examined.

The exceptions were patients younger than 40, Hispanic patients, and those belonging to the “other” race category. (The race categories were “white,” “black,” and “other,” while the ethnicity categories were “Hispanic” and “non-Hispanic.”)

The data also showed improvements in survival over time among patients with ESRD due to MM.

Compared to 2001-2002, the adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) for death were 1.02 for 2003-2004 (P=0.5), 0.93 for 2005-2006 (P=0.02), 0.86 for 2007-2008 (P<0.001), and 0.74 for 2009-2010 (P<0.001). (This analysis was adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, mode of RRT, estimated glomerular filtration rate, body mass index, serum albumin, and hemoglobin.)

AHRs for death were highest in the first year after RRT initiation (AHR=2.6; P<0.001) and decreased in year 3 (AHR=1.59; P<0.001).

The AHR for death in patients with ESRD due to MM compared to those with ESRD due to all other causes was 2.05 (P<0.001).

“Myeloma is the commonest malignancy leading to kidney failure,” Dr Foley said. “It’s encouraging that we found that kidney failure due to multiple myeloma declined considerably over the last decade.” ![]()

Photo by Anna Frodesiak

New research suggests the risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) caused by multiple myeloma (MM) is declining, and survival is lengthening for patients who do develop ESRD due to MM.

Researchers said these findings are encouraging, but efforts are still needed to develop effective MM treatments with fewer side effects.

They noted that MM treatment has changed substantially in the last decade.

But it hasn’t been clear whether the burden of ESRD due to MM has changed or whether survival has improved for patients with ESRD due to MM.

To gain some insight, Robert Foley, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and his colleagues examined data from the US Renal Data System database spanning the period from 2001 to 2010.

They reported their findings in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The team found that, of the 1,069,343 patients with ESRD who were on renal replacement therapy (RRT), 12,703 had developed ESRD due to MM.

However, the incidence of ESRD from MM decreased from 2001 to 2010. Compared to 2001-2002 (1.00), the standardized incidence ratios of ESRD due to MM were 0.96 for 2003-2004 (P<0.05), 0.99 for 2005-2006 (P>0.05), 0.89 for 2007-2008 (P<0.001), and 0.82 for 2009-2010 (P<0.001).

The demography-adjusted incidence ratio for ESRD due to MM decreased (P<0.05) between 2001-2002 and 2009-2010 in the overall population and in most of the subgroups examined.

The exceptions were patients younger than 40, Hispanic patients, and those belonging to the “other” race category. (The race categories were “white,” “black,” and “other,” while the ethnicity categories were “Hispanic” and “non-Hispanic.”)

The data also showed improvements in survival over time among patients with ESRD due to MM.

Compared to 2001-2002, the adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) for death were 1.02 for 2003-2004 (P=0.5), 0.93 for 2005-2006 (P=0.02), 0.86 for 2007-2008 (P<0.001), and 0.74 for 2009-2010 (P<0.001). (This analysis was adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, mode of RRT, estimated glomerular filtration rate, body mass index, serum albumin, and hemoglobin.)

AHRs for death were highest in the first year after RRT initiation (AHR=2.6; P<0.001) and decreased in year 3 (AHR=1.59; P<0.001).

The AHR for death in patients with ESRD due to MM compared to those with ESRD due to all other causes was 2.05 (P<0.001).

“Myeloma is the commonest malignancy leading to kidney failure,” Dr Foley said. “It’s encouraging that we found that kidney failure due to multiple myeloma declined considerably over the last decade.” ![]()

Case reports: Ingestion of aripiprazole precedes false positives for amphetamine use

Two children who had ingested aripiprazole but not amphetamines tested positive for amphetamine use in urine drug screens (UDSs) performed within 24 hours of their drug use, according to two case reports by Justin Kaplan, Pharm.D., of Hackensack (N.J.) University Medical Center and his colleagues.

In both cases, aripiprazole had been prescribed to the father of the child and had been taken by the child without the knowledge or auspices of a parent. Both of the children were admitted to hospitals where their urine was screened for drugs.

“To our knowledge this case series is the first to document potential false-positive UDSs after accidental ingestion of aripiprazole,” said the researchers. “In both cases, the presentation of drowsiness, lethargy, and ataxia were more consistent with ingestion of an atypical antipsychotic than with amphetamines.”

In one of the cases, a 2-year-old girl was found holding an open bottle of aripiprazole 15-mg tablets by her parents. The parents’ report of the incident suggested that the child had ingested three such tablets. The child’s urine was screened for amphetamines twice, in the hospital where she was admitted; the first screen, which was performed the morning after the child had been taken to a hospital, revealed an amphetamine concentration of 1,048 ng/mL. The child’s second UDS, which was performed the following day, indicated a 949 ng/mL concentration of amphetamines. Outside of the hospital, laboratory tests were performed on the child’s blood and urine samples from the day following her admittance to the hospital. Both of these additional tests were negative for amphetamines, suggesting that the results of the in-hospital UDSs had been false positives.

The other case involved a 20-month-old girl, whose father found her with pills scattered around her crib. The drugs were part of a 1-week supply of drugs of the father. The medications included alprazolam 2.5 mg, fluvoxamine 2,100 mg, clonazepam 17.5 mg, buspirone 420 mg, and aripiprazole 35 mg. This child’s urine was also screened for drugs twice at the hospital where she was admitted; this child only tested positive for amphetamine in the first assessment, with a 311 ng/mL concentration of amphetamines having been found in that UDS. As with the first case, this child’s urine and blood samples were subjected to off-site laboratory tests, which found no presence of amphetamines.

“There are several limitations to UDS immunoassays. Most important, poor specificity is associated with a risk of false-positive testing. A negative result does not exclude the possibility that the substance is present if it is below the lower threshold of detection. Additionally, there is no way to quantitatively correlate a positive result with the extent of immunoassays. Therefore immunoassays are the first step in a two-step system, in which all positive results must be confirmed by more reliable methods such as [gas chromatography mass spectrometry],” the researchers said.

Read the full study in Pediatrics. doi: 10:1542/peds.2014-3333.

Two children who had ingested aripiprazole but not amphetamines tested positive for amphetamine use in urine drug screens (UDSs) performed within 24 hours of their drug use, according to two case reports by Justin Kaplan, Pharm.D., of Hackensack (N.J.) University Medical Center and his colleagues.

In both cases, aripiprazole had been prescribed to the father of the child and had been taken by the child without the knowledge or auspices of a parent. Both of the children were admitted to hospitals where their urine was screened for drugs.

“To our knowledge this case series is the first to document potential false-positive UDSs after accidental ingestion of aripiprazole,” said the researchers. “In both cases, the presentation of drowsiness, lethargy, and ataxia were more consistent with ingestion of an atypical antipsychotic than with amphetamines.”

In one of the cases, a 2-year-old girl was found holding an open bottle of aripiprazole 15-mg tablets by her parents. The parents’ report of the incident suggested that the child had ingested three such tablets. The child’s urine was screened for amphetamines twice, in the hospital where she was admitted; the first screen, which was performed the morning after the child had been taken to a hospital, revealed an amphetamine concentration of 1,048 ng/mL. The child’s second UDS, which was performed the following day, indicated a 949 ng/mL concentration of amphetamines. Outside of the hospital, laboratory tests were performed on the child’s blood and urine samples from the day following her admittance to the hospital. Both of these additional tests were negative for amphetamines, suggesting that the results of the in-hospital UDSs had been false positives.

The other case involved a 20-month-old girl, whose father found her with pills scattered around her crib. The drugs were part of a 1-week supply of drugs of the father. The medications included alprazolam 2.5 mg, fluvoxamine 2,100 mg, clonazepam 17.5 mg, buspirone 420 mg, and aripiprazole 35 mg. This child’s urine was also screened for drugs twice at the hospital where she was admitted; this child only tested positive for amphetamine in the first assessment, with a 311 ng/mL concentration of amphetamines having been found in that UDS. As with the first case, this child’s urine and blood samples were subjected to off-site laboratory tests, which found no presence of amphetamines.

“There are several limitations to UDS immunoassays. Most important, poor specificity is associated with a risk of false-positive testing. A negative result does not exclude the possibility that the substance is present if it is below the lower threshold of detection. Additionally, there is no way to quantitatively correlate a positive result with the extent of immunoassays. Therefore immunoassays are the first step in a two-step system, in which all positive results must be confirmed by more reliable methods such as [gas chromatography mass spectrometry],” the researchers said.

Read the full study in Pediatrics. doi: 10:1542/peds.2014-3333.

Two children who had ingested aripiprazole but not amphetamines tested positive for amphetamine use in urine drug screens (UDSs) performed within 24 hours of their drug use, according to two case reports by Justin Kaplan, Pharm.D., of Hackensack (N.J.) University Medical Center and his colleagues.

In both cases, aripiprazole had been prescribed to the father of the child and had been taken by the child without the knowledge or auspices of a parent. Both of the children were admitted to hospitals where their urine was screened for drugs.

“To our knowledge this case series is the first to document potential false-positive UDSs after accidental ingestion of aripiprazole,” said the researchers. “In both cases, the presentation of drowsiness, lethargy, and ataxia were more consistent with ingestion of an atypical antipsychotic than with amphetamines.”

In one of the cases, a 2-year-old girl was found holding an open bottle of aripiprazole 15-mg tablets by her parents. The parents’ report of the incident suggested that the child had ingested three such tablets. The child’s urine was screened for amphetamines twice, in the hospital where she was admitted; the first screen, which was performed the morning after the child had been taken to a hospital, revealed an amphetamine concentration of 1,048 ng/mL. The child’s second UDS, which was performed the following day, indicated a 949 ng/mL concentration of amphetamines. Outside of the hospital, laboratory tests were performed on the child’s blood and urine samples from the day following her admittance to the hospital. Both of these additional tests were negative for amphetamines, suggesting that the results of the in-hospital UDSs had been false positives.

The other case involved a 20-month-old girl, whose father found her with pills scattered around her crib. The drugs were part of a 1-week supply of drugs of the father. The medications included alprazolam 2.5 mg, fluvoxamine 2,100 mg, clonazepam 17.5 mg, buspirone 420 mg, and aripiprazole 35 mg. This child’s urine was also screened for drugs twice at the hospital where she was admitted; this child only tested positive for amphetamine in the first assessment, with a 311 ng/mL concentration of amphetamines having been found in that UDS. As with the first case, this child’s urine and blood samples were subjected to off-site laboratory tests, which found no presence of amphetamines.

“There are several limitations to UDS immunoassays. Most important, poor specificity is associated with a risk of false-positive testing. A negative result does not exclude the possibility that the substance is present if it is below the lower threshold of detection. Additionally, there is no way to quantitatively correlate a positive result with the extent of immunoassays. Therefore immunoassays are the first step in a two-step system, in which all positive results must be confirmed by more reliable methods such as [gas chromatography mass spectrometry],” the researchers said.

Read the full study in Pediatrics. doi: 10:1542/peds.2014-3333.

FROM PEDIATRICS

ITC: Study provides first evidence of paclitaxel benefit for anaplastic thyroid cancer

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Weekly infusions of paclitaxel delayed progression in some patients with the very aggressive anaplastic thyroid cancer, a small prospective study determined.

The drug was most effective as adjuvant therapy for patients who had already undergone chemotherapy plus resection of the primary tumor, Dr. Naoyoshi Onoda reported in a poster session at the International Thyroid Conference. They survived for a median of 1 year (112-788 days) – an impressive feat considering that most patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer die within 6 months of diagnosis.

This finding suggests a place for paclitaxel as a standardized therapy for such patients, said Dr. Onoda of Osaka (Japan) City University. “We have objective data supporting standardized chemotherapy for the first time in the world.”

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is a very rare – but very aggressive – disease; there is no standardized treatment option. Dr. Onoda and his colleagues conducted a national prospective open-label study of weekly paclitaxel infusions in 56 patients with the malignancy.

The cohort was a median of 71 years old. All had stage IV disease: 10 were grade A, 18 grade B, 24 grade C, and four grade X. They received 80 mg/m2 infusions once a week. The median number of cycles was 2, although it ranged from 0-23 cycles.

Almost everyone (98%) experienced adverse events; the most common was anemia (77%). About a quarter (28%) experienced adverse events of at least grade 3, but there were no serious events and no deaths related to the study drug.

The objective response rate and the clinical benefit rate were 23% and 79%. The agent was not curative; at the last follow-up, no patient had achieved a complete response, and 43 of 56 in the study had died of their disease. “Overall, the median time to progression was only 47 days, and median overall survival just 227 days. That is so very short. But it’s a little bit longer than we had been seeing rates from reported cases,” he said at the meeting held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society.

The study was sponsored by the Prospective Clinical Study Committee of the Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma Research Consortium of Japan (ATCCJ). Dr. Onoda had no financial disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Weekly infusions of paclitaxel delayed progression in some patients with the very aggressive anaplastic thyroid cancer, a small prospective study determined.

The drug was most effective as adjuvant therapy for patients who had already undergone chemotherapy plus resection of the primary tumor, Dr. Naoyoshi Onoda reported in a poster session at the International Thyroid Conference. They survived for a median of 1 year (112-788 days) – an impressive feat considering that most patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer die within 6 months of diagnosis.

This finding suggests a place for paclitaxel as a standardized therapy for such patients, said Dr. Onoda of Osaka (Japan) City University. “We have objective data supporting standardized chemotherapy for the first time in the world.”

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is a very rare – but very aggressive – disease; there is no standardized treatment option. Dr. Onoda and his colleagues conducted a national prospective open-label study of weekly paclitaxel infusions in 56 patients with the malignancy.

The cohort was a median of 71 years old. All had stage IV disease: 10 were grade A, 18 grade B, 24 grade C, and four grade X. They received 80 mg/m2 infusions once a week. The median number of cycles was 2, although it ranged from 0-23 cycles.

Almost everyone (98%) experienced adverse events; the most common was anemia (77%). About a quarter (28%) experienced adverse events of at least grade 3, but there were no serious events and no deaths related to the study drug.

The objective response rate and the clinical benefit rate were 23% and 79%. The agent was not curative; at the last follow-up, no patient had achieved a complete response, and 43 of 56 in the study had died of their disease. “Overall, the median time to progression was only 47 days, and median overall survival just 227 days. That is so very short. But it’s a little bit longer than we had been seeing rates from reported cases,” he said at the meeting held by the American Thyroid Association, Asia-Oceania Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, and Latin American Thyroid Society.

The study was sponsored by the Prospective Clinical Study Committee of the Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma Research Consortium of Japan (ATCCJ). Dr. Onoda had no financial disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Weekly infusions of paclitaxel delayed progression in some patients with the very aggressive anaplastic thyroid cancer, a small prospective study determined.

The drug was most effective as adjuvant therapy for patients who had already undergone chemotherapy plus resection of the primary tumor, Dr. Naoyoshi Onoda reported in a poster session at the International Thyroid Conference. They survived for a median of 1 year (112-788 days) – an impressive feat considering that most patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer die within 6 months of diagnosis.

This finding suggests a place for paclitaxel as a standardized therapy for such patients, said Dr. Onoda of Osaka (Japan) City University. “We have objective data supporting standardized chemotherapy for the first time in the world.”