User login

Medical Education and Firearm-Related Deaths

For the third straight year, firearms killed more children and teens than any other cause, including motor vehicle crashes and cancer. The population-wide toll taken by guns is equally as discouraging. Finally, this elephant in the room is getting some attention from the medical community, but the voices asking for change have most recently been coming from medical students who feel that gun violence deserves to be given a larger role in their education. It’s unclear why this plea is coming from the younger end of the medical community. It may be that, unlike most of their older instructors, these 18- to 25-year-olds have grown up under the growing threat of school shootings and become uncomfortably accustomed to active shooter drills.

Should We Look to Medical School for Answers?

But, does the medical community need to take gun violence more seriously than the rest of the population? What should our response look like? To answer those questions we need to take several steps back to view the bigger picture.

Is the medical community more responsible for this current situation than any other segment of the population? Do physicians bear any more culpability than publishers who sell gun-related magazines? Since its inception pediatrics has taken on the role of advocate for children and their health and well-being. But, is there more we can and should do other than turn up the volume on our advocacy?

While still taking the longer view, let’s ask ourselves what the role of medical school should be. Not just with respect to gun violence but in producing physicians and healthcare providers. We are approaching a crisis in primary care as it loses appeal with physicians at both ends of the age continuum. It could be because it pays poorly — certainly in relation to the cost of medical school — or because the awareness that if done well primary care requires a commitment that is difficult to square with many individuals’ lifestyle expectations.

Is the traditional medical school the right place to be training primary care providers? Medical school is currently aimed at broad and deep exposure. The student will be exposed to the all the diseases to which he or she might be seeing anywhere in the world and at the same time will have learned the mechanisms down to the cellular level that lies behind that pathology. Does a primary care pediatrician practicing in a small city or suburbia need that depth of training? He or she might benefit from some breadth. But maybe it should be focused on socioeconomic and geographic population the doctor is likely to see. This is particularly true for gun-related deaths.

Returning our attention to gun violence and its relation to healthcare, let’s ask ourselves what role the traditional medical school should play. Should it be a breeding ground for gun control advocates? When physicians speak people tend to listen but our effectiveness on issues such as immunizations and gun control has not been what many have hoped for. The supply of guns available to the public in this country is staggering and certainly contributes to gun-related injuries and death. However, I’m afraid that making a significant dent in that supply, given our political history and current climate, is an issue whose ship has sailed.

On the other hand, as gun advocates are often quoted as saying, “it’s not guns that kill, it’s people.” We don’t need to go into to the fallacy of this argument, but it gives us a starting point from which a medical school might focus its efforts on addressing the fallout from gun violence. A curriculum that begins with a presentation of the grizzly statistics and moves on to research about gun-related mental health issues and the social environments that breed violence makes good sense. Recanting the depressing history of how our society got to this place, in which guns outnumber people, should be part of the undergraduate curriculum.

Addressing the specifics of gun safety and suicide prevention in general with families and individuals would be more appropriate during clinical specialty training.

How big a chunk of the curriculum should be committed to gun violence and its fallout? Some of the call for change seems to be suggesting a semester-long course. However, we must accept the reality that instructional time in medical school is a finite asset. Although gunshots are the leading cause of death in children, how effective will even the most cleverly crafted curriculum be in moving the needle on the embarrassing data?

Given what is known about the problem, a day, or at most a week would be sufficient in class time. This could include personal presentations by victims or family members. I’m sure there are some who would see that as insufficient. But I see it as realistic. For the large urban schools, observing an evening shift in the trauma unit of an ER could be a potent addition.

Beyond this, a commitment by the school to host seminars and workshops devoted to gun violence could be an important component. It might also be helpful for a school or training program to promote the habit of whenever an instructor is introducing a potentially fatal disease to the students for the first time, he or she would begin with “To put this in perspective, you should remember that xxx thousand children die of gunshot wounds every year.”

Unfortunately, like obesity, gun-related deaths and injuries are the result of our society’s failure to muster the political will to act in our best interest as a nation. The medical community is left to clean up the collateral damage. There is always more that we could do, but we must be thoughtful in how we invest our energies in the effort.

Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

For the third straight year, firearms killed more children and teens than any other cause, including motor vehicle crashes and cancer. The population-wide toll taken by guns is equally as discouraging. Finally, this elephant in the room is getting some attention from the medical community, but the voices asking for change have most recently been coming from medical students who feel that gun violence deserves to be given a larger role in their education. It’s unclear why this plea is coming from the younger end of the medical community. It may be that, unlike most of their older instructors, these 18- to 25-year-olds have grown up under the growing threat of school shootings and become uncomfortably accustomed to active shooter drills.

Should We Look to Medical School for Answers?

But, does the medical community need to take gun violence more seriously than the rest of the population? What should our response look like? To answer those questions we need to take several steps back to view the bigger picture.

Is the medical community more responsible for this current situation than any other segment of the population? Do physicians bear any more culpability than publishers who sell gun-related magazines? Since its inception pediatrics has taken on the role of advocate for children and their health and well-being. But, is there more we can and should do other than turn up the volume on our advocacy?

While still taking the longer view, let’s ask ourselves what the role of medical school should be. Not just with respect to gun violence but in producing physicians and healthcare providers. We are approaching a crisis in primary care as it loses appeal with physicians at both ends of the age continuum. It could be because it pays poorly — certainly in relation to the cost of medical school — or because the awareness that if done well primary care requires a commitment that is difficult to square with many individuals’ lifestyle expectations.

Is the traditional medical school the right place to be training primary care providers? Medical school is currently aimed at broad and deep exposure. The student will be exposed to the all the diseases to which he or she might be seeing anywhere in the world and at the same time will have learned the mechanisms down to the cellular level that lies behind that pathology. Does a primary care pediatrician practicing in a small city or suburbia need that depth of training? He or she might benefit from some breadth. But maybe it should be focused on socioeconomic and geographic population the doctor is likely to see. This is particularly true for gun-related deaths.

Returning our attention to gun violence and its relation to healthcare, let’s ask ourselves what role the traditional medical school should play. Should it be a breeding ground for gun control advocates? When physicians speak people tend to listen but our effectiveness on issues such as immunizations and gun control has not been what many have hoped for. The supply of guns available to the public in this country is staggering and certainly contributes to gun-related injuries and death. However, I’m afraid that making a significant dent in that supply, given our political history and current climate, is an issue whose ship has sailed.

On the other hand, as gun advocates are often quoted as saying, “it’s not guns that kill, it’s people.” We don’t need to go into to the fallacy of this argument, but it gives us a starting point from which a medical school might focus its efforts on addressing the fallout from gun violence. A curriculum that begins with a presentation of the grizzly statistics and moves on to research about gun-related mental health issues and the social environments that breed violence makes good sense. Recanting the depressing history of how our society got to this place, in which guns outnumber people, should be part of the undergraduate curriculum.

Addressing the specifics of gun safety and suicide prevention in general with families and individuals would be more appropriate during clinical specialty training.

How big a chunk of the curriculum should be committed to gun violence and its fallout? Some of the call for change seems to be suggesting a semester-long course. However, we must accept the reality that instructional time in medical school is a finite asset. Although gunshots are the leading cause of death in children, how effective will even the most cleverly crafted curriculum be in moving the needle on the embarrassing data?

Given what is known about the problem, a day, or at most a week would be sufficient in class time. This could include personal presentations by victims or family members. I’m sure there are some who would see that as insufficient. But I see it as realistic. For the large urban schools, observing an evening shift in the trauma unit of an ER could be a potent addition.

Beyond this, a commitment by the school to host seminars and workshops devoted to gun violence could be an important component. It might also be helpful for a school or training program to promote the habit of whenever an instructor is introducing a potentially fatal disease to the students for the first time, he or she would begin with “To put this in perspective, you should remember that xxx thousand children die of gunshot wounds every year.”

Unfortunately, like obesity, gun-related deaths and injuries are the result of our society’s failure to muster the political will to act in our best interest as a nation. The medical community is left to clean up the collateral damage. There is always more that we could do, but we must be thoughtful in how we invest our energies in the effort.

Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

For the third straight year, firearms killed more children and teens than any other cause, including motor vehicle crashes and cancer. The population-wide toll taken by guns is equally as discouraging. Finally, this elephant in the room is getting some attention from the medical community, but the voices asking for change have most recently been coming from medical students who feel that gun violence deserves to be given a larger role in their education. It’s unclear why this plea is coming from the younger end of the medical community. It may be that, unlike most of their older instructors, these 18- to 25-year-olds have grown up under the growing threat of school shootings and become uncomfortably accustomed to active shooter drills.

Should We Look to Medical School for Answers?

But, does the medical community need to take gun violence more seriously than the rest of the population? What should our response look like? To answer those questions we need to take several steps back to view the bigger picture.

Is the medical community more responsible for this current situation than any other segment of the population? Do physicians bear any more culpability than publishers who sell gun-related magazines? Since its inception pediatrics has taken on the role of advocate for children and their health and well-being. But, is there more we can and should do other than turn up the volume on our advocacy?

While still taking the longer view, let’s ask ourselves what the role of medical school should be. Not just with respect to gun violence but in producing physicians and healthcare providers. We are approaching a crisis in primary care as it loses appeal with physicians at both ends of the age continuum. It could be because it pays poorly — certainly in relation to the cost of medical school — or because the awareness that if done well primary care requires a commitment that is difficult to square with many individuals’ lifestyle expectations.

Is the traditional medical school the right place to be training primary care providers? Medical school is currently aimed at broad and deep exposure. The student will be exposed to the all the diseases to which he or she might be seeing anywhere in the world and at the same time will have learned the mechanisms down to the cellular level that lies behind that pathology. Does a primary care pediatrician practicing in a small city or suburbia need that depth of training? He or she might benefit from some breadth. But maybe it should be focused on socioeconomic and geographic population the doctor is likely to see. This is particularly true for gun-related deaths.

Returning our attention to gun violence and its relation to healthcare, let’s ask ourselves what role the traditional medical school should play. Should it be a breeding ground for gun control advocates? When physicians speak people tend to listen but our effectiveness on issues such as immunizations and gun control has not been what many have hoped for. The supply of guns available to the public in this country is staggering and certainly contributes to gun-related injuries and death. However, I’m afraid that making a significant dent in that supply, given our political history and current climate, is an issue whose ship has sailed.

On the other hand, as gun advocates are often quoted as saying, “it’s not guns that kill, it’s people.” We don’t need to go into to the fallacy of this argument, but it gives us a starting point from which a medical school might focus its efforts on addressing the fallout from gun violence. A curriculum that begins with a presentation of the grizzly statistics and moves on to research about gun-related mental health issues and the social environments that breed violence makes good sense. Recanting the depressing history of how our society got to this place, in which guns outnumber people, should be part of the undergraduate curriculum.

Addressing the specifics of gun safety and suicide prevention in general with families and individuals would be more appropriate during clinical specialty training.

How big a chunk of the curriculum should be committed to gun violence and its fallout? Some of the call for change seems to be suggesting a semester-long course. However, we must accept the reality that instructional time in medical school is a finite asset. Although gunshots are the leading cause of death in children, how effective will even the most cleverly crafted curriculum be in moving the needle on the embarrassing data?

Given what is known about the problem, a day, or at most a week would be sufficient in class time. This could include personal presentations by victims or family members. I’m sure there are some who would see that as insufficient. But I see it as realistic. For the large urban schools, observing an evening shift in the trauma unit of an ER could be a potent addition.

Beyond this, a commitment by the school to host seminars and workshops devoted to gun violence could be an important component. It might also be helpful for a school or training program to promote the habit of whenever an instructor is introducing a potentially fatal disease to the students for the first time, he or she would begin with “To put this in perspective, you should remember that xxx thousand children die of gunshot wounds every year.”

Unfortunately, like obesity, gun-related deaths and injuries are the result of our society’s failure to muster the political will to act in our best interest as a nation. The medical community is left to clean up the collateral damage. There is always more that we could do, but we must be thoughtful in how we invest our energies in the effort.

Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Study Supports Pediatric Concussion Management Approach

“With that result, it means we don’t need to change management protocols” depending on the cause of the concussion, study author Andrée-Anne Ledoux, PhD, a scientist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, said in an interview. “That’s kind of good news. We’re applying the right management protocols with them.”

The data were published on December 4 in JAMA Network Open.

Secondary Analysis

The results stem from a planned secondary analysis of the prospective Predicting and Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics study. Conducted from August 2013 to June 2015 at nine pediatric emergency departments in Canada, it included children of different ages (5 to < 18 years), genders, demographic characteristics, and comorbidities. All participants had a concussion.

The secondary analysis focused on study participants who were aged 5-12 years and had presented within 48 hours of injury. The primary outcome was symptom change, which was defined as current ratings minus preinjury ratings, across time (1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks), measured using the Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory.

No significant differences in postinjury recovery curves were found between participants with sport-related concussions (SRC) and those with non-SRC. The latter injuries resulted from causes such as falls and objects dropped on heads. SRC and non-SRC showed a nonlinear association with time, with symptoms decreasing over time.

Perhaps surprisingly, the researchers also reported a higher rate of persisting symptoms after concussion (PSAC) following limited contact sports than following contact sports such as hockey, soccer, rugby, lacrosse, and football. Limited contact sports include activities such as bicycling, horseback riding, tobogganing, gymnastics, and cheerleading.

This finding suggests that the management of SRC may not require distinct strategies based on sports classification, the researchers wrote. “Instead, it may be more appropriate for clinicians to consider the specific dynamics of the activity, such as velocity and risk of falls from heights. This nuanced perspective can aid in assessing the likelihood of persisting symptoms.” The researchers urged more investigation of this question. “A larger sample with more information on injury height and velocity would be required to confirm whether an association exists.”

In addition, the researchers cited guidelines that include a recommendation for a gradual return to low to moderate physical and cognitive activity starting 24-48 hours after a concussion at a level that does not result in recurrence or exacerbation of symptoms.

“Children do need to return to their lives. They need to return to school,” said Ledoux. “They can have accommodations while they return to school, but just returning to school has huge benefits because you’re reintegrating the child into their typical lifestyle and socialization as well.”

A potential limitation of the study was its reliance on participants who had been seen in emergency departments and thus may have been experiencing more intense symptoms than those seen elsewhere.

The researchers also excluded cases of concussion resulting from assaults and motor vehicle crashes. This decision may explain why they didn’t reproduce the previous observation that patients with SRC tended to recover faster than those with concussions from other causes.

Injuries resulting from assaults and motor vehicle crashes can involve damage beyond concussions, Ledoux said. Including these cases would not allow for an apples-to-apples comparison of SRC and non-SRC.

‘Don’t Cocoon Kids’

The authors of an accompanying editorial wrote that the researchers had done “a beautiful job highlighting this important nuance.” Noncontact sports with seemingly little risk “actually carry substantial risks when one imagines the high-impact forces that can occur with a fall from height, albeit rare,” Scott Zuckerman, MD, MPH, assistant professor of neurological surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, and colleagues wrote.

The new analysis suggests a need to rethink a “somewhat archaic way of classifying sport risk, which may oversimplify how we categorize risk of brain and spine injuries.”

The commentary also noted how the researchers used the term PSAC to describe lingering symptoms instead of more widely used terms like “persistent postconcussive symptoms” or “postconcussive syndrome.”

“These traditional terms often connote a permanent syndrome or assumption that the concussion itself is solely responsible for 100% of symptoms, which can be harmful to a patient’s recovery,” the editorialists wrote. “Conversely, PSAC offers room for the clinician to discuss how other causes may be maintaining, magnifying, or mimicking concussion symptoms.”

Commenting on the findings, Richard Figler, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, praised the researchers for addressing concussion in younger children, a field in which little research has been conducted. The research supports the current approaches to treatment. The approach has shifted toward easing children quickly and safely back into normal routines. “We don’t cocoon kids. We don’t send them to dark rooms,” Figler added.

He also commended the researchers’ decision to examine data about concussions linked to limited contact sports. In contact sports, participants may be more likely to anticipate and prepare for a hit. That’s not the case with injuries sustained in limited contact sports.

“Dodgeball is basically a sucker punch. That’s why these kids have so many concussions,” said Figler. “They typically don’t see the ball coming, or they can’t get out of the way, and they can’t tense themselves to take that blow.”

The Predicting and Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research-Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Team. Ledoux reported receiving grants from the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Foundation, Ontario Brain Institute, and University of Ottawa Brain and Mind Research Institute. She received nonfinancial support from Mobio Interactive outside the submitted work. Zuckerman reported receiving personal fees from the National Football League and Medtronic outside the submitted work. Figler had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“With that result, it means we don’t need to change management protocols” depending on the cause of the concussion, study author Andrée-Anne Ledoux, PhD, a scientist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, said in an interview. “That’s kind of good news. We’re applying the right management protocols with them.”

The data were published on December 4 in JAMA Network Open.

Secondary Analysis

The results stem from a planned secondary analysis of the prospective Predicting and Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics study. Conducted from August 2013 to June 2015 at nine pediatric emergency departments in Canada, it included children of different ages (5 to < 18 years), genders, demographic characteristics, and comorbidities. All participants had a concussion.

The secondary analysis focused on study participants who were aged 5-12 years and had presented within 48 hours of injury. The primary outcome was symptom change, which was defined as current ratings minus preinjury ratings, across time (1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks), measured using the Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory.

No significant differences in postinjury recovery curves were found between participants with sport-related concussions (SRC) and those with non-SRC. The latter injuries resulted from causes such as falls and objects dropped on heads. SRC and non-SRC showed a nonlinear association with time, with symptoms decreasing over time.

Perhaps surprisingly, the researchers also reported a higher rate of persisting symptoms after concussion (PSAC) following limited contact sports than following contact sports such as hockey, soccer, rugby, lacrosse, and football. Limited contact sports include activities such as bicycling, horseback riding, tobogganing, gymnastics, and cheerleading.

This finding suggests that the management of SRC may not require distinct strategies based on sports classification, the researchers wrote. “Instead, it may be more appropriate for clinicians to consider the specific dynamics of the activity, such as velocity and risk of falls from heights. This nuanced perspective can aid in assessing the likelihood of persisting symptoms.” The researchers urged more investigation of this question. “A larger sample with more information on injury height and velocity would be required to confirm whether an association exists.”

In addition, the researchers cited guidelines that include a recommendation for a gradual return to low to moderate physical and cognitive activity starting 24-48 hours after a concussion at a level that does not result in recurrence or exacerbation of symptoms.

“Children do need to return to their lives. They need to return to school,” said Ledoux. “They can have accommodations while they return to school, but just returning to school has huge benefits because you’re reintegrating the child into their typical lifestyle and socialization as well.”

A potential limitation of the study was its reliance on participants who had been seen in emergency departments and thus may have been experiencing more intense symptoms than those seen elsewhere.

The researchers also excluded cases of concussion resulting from assaults and motor vehicle crashes. This decision may explain why they didn’t reproduce the previous observation that patients with SRC tended to recover faster than those with concussions from other causes.

Injuries resulting from assaults and motor vehicle crashes can involve damage beyond concussions, Ledoux said. Including these cases would not allow for an apples-to-apples comparison of SRC and non-SRC.

‘Don’t Cocoon Kids’

The authors of an accompanying editorial wrote that the researchers had done “a beautiful job highlighting this important nuance.” Noncontact sports with seemingly little risk “actually carry substantial risks when one imagines the high-impact forces that can occur with a fall from height, albeit rare,” Scott Zuckerman, MD, MPH, assistant professor of neurological surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, and colleagues wrote.

The new analysis suggests a need to rethink a “somewhat archaic way of classifying sport risk, which may oversimplify how we categorize risk of brain and spine injuries.”

The commentary also noted how the researchers used the term PSAC to describe lingering symptoms instead of more widely used terms like “persistent postconcussive symptoms” or “postconcussive syndrome.”

“These traditional terms often connote a permanent syndrome or assumption that the concussion itself is solely responsible for 100% of symptoms, which can be harmful to a patient’s recovery,” the editorialists wrote. “Conversely, PSAC offers room for the clinician to discuss how other causes may be maintaining, magnifying, or mimicking concussion symptoms.”

Commenting on the findings, Richard Figler, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, praised the researchers for addressing concussion in younger children, a field in which little research has been conducted. The research supports the current approaches to treatment. The approach has shifted toward easing children quickly and safely back into normal routines. “We don’t cocoon kids. We don’t send them to dark rooms,” Figler added.

He also commended the researchers’ decision to examine data about concussions linked to limited contact sports. In contact sports, participants may be more likely to anticipate and prepare for a hit. That’s not the case with injuries sustained in limited contact sports.

“Dodgeball is basically a sucker punch. That’s why these kids have so many concussions,” said Figler. “They typically don’t see the ball coming, or they can’t get out of the way, and they can’t tense themselves to take that blow.”

The Predicting and Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research-Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Team. Ledoux reported receiving grants from the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Foundation, Ontario Brain Institute, and University of Ottawa Brain and Mind Research Institute. She received nonfinancial support from Mobio Interactive outside the submitted work. Zuckerman reported receiving personal fees from the National Football League and Medtronic outside the submitted work. Figler had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“With that result, it means we don’t need to change management protocols” depending on the cause of the concussion, study author Andrée-Anne Ledoux, PhD, a scientist at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, said in an interview. “That’s kind of good news. We’re applying the right management protocols with them.”

The data were published on December 4 in JAMA Network Open.

Secondary Analysis

The results stem from a planned secondary analysis of the prospective Predicting and Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics study. Conducted from August 2013 to June 2015 at nine pediatric emergency departments in Canada, it included children of different ages (5 to < 18 years), genders, demographic characteristics, and comorbidities. All participants had a concussion.

The secondary analysis focused on study participants who were aged 5-12 years and had presented within 48 hours of injury. The primary outcome was symptom change, which was defined as current ratings minus preinjury ratings, across time (1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks), measured using the Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory.

No significant differences in postinjury recovery curves were found between participants with sport-related concussions (SRC) and those with non-SRC. The latter injuries resulted from causes such as falls and objects dropped on heads. SRC and non-SRC showed a nonlinear association with time, with symptoms decreasing over time.

Perhaps surprisingly, the researchers also reported a higher rate of persisting symptoms after concussion (PSAC) following limited contact sports than following contact sports such as hockey, soccer, rugby, lacrosse, and football. Limited contact sports include activities such as bicycling, horseback riding, tobogganing, gymnastics, and cheerleading.

This finding suggests that the management of SRC may not require distinct strategies based on sports classification, the researchers wrote. “Instead, it may be more appropriate for clinicians to consider the specific dynamics of the activity, such as velocity and risk of falls from heights. This nuanced perspective can aid in assessing the likelihood of persisting symptoms.” The researchers urged more investigation of this question. “A larger sample with more information on injury height and velocity would be required to confirm whether an association exists.”

In addition, the researchers cited guidelines that include a recommendation for a gradual return to low to moderate physical and cognitive activity starting 24-48 hours after a concussion at a level that does not result in recurrence or exacerbation of symptoms.

“Children do need to return to their lives. They need to return to school,” said Ledoux. “They can have accommodations while they return to school, but just returning to school has huge benefits because you’re reintegrating the child into their typical lifestyle and socialization as well.”

A potential limitation of the study was its reliance on participants who had been seen in emergency departments and thus may have been experiencing more intense symptoms than those seen elsewhere.

The researchers also excluded cases of concussion resulting from assaults and motor vehicle crashes. This decision may explain why they didn’t reproduce the previous observation that patients with SRC tended to recover faster than those with concussions from other causes.

Injuries resulting from assaults and motor vehicle crashes can involve damage beyond concussions, Ledoux said. Including these cases would not allow for an apples-to-apples comparison of SRC and non-SRC.

‘Don’t Cocoon Kids’

The authors of an accompanying editorial wrote that the researchers had done “a beautiful job highlighting this important nuance.” Noncontact sports with seemingly little risk “actually carry substantial risks when one imagines the high-impact forces that can occur with a fall from height, albeit rare,” Scott Zuckerman, MD, MPH, assistant professor of neurological surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, and colleagues wrote.

The new analysis suggests a need to rethink a “somewhat archaic way of classifying sport risk, which may oversimplify how we categorize risk of brain and spine injuries.”

The commentary also noted how the researchers used the term PSAC to describe lingering symptoms instead of more widely used terms like “persistent postconcussive symptoms” or “postconcussive syndrome.”

“These traditional terms often connote a permanent syndrome or assumption that the concussion itself is solely responsible for 100% of symptoms, which can be harmful to a patient’s recovery,” the editorialists wrote. “Conversely, PSAC offers room for the clinician to discuss how other causes may be maintaining, magnifying, or mimicking concussion symptoms.”

Commenting on the findings, Richard Figler, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, praised the researchers for addressing concussion in younger children, a field in which little research has been conducted. The research supports the current approaches to treatment. The approach has shifted toward easing children quickly and safely back into normal routines. “We don’t cocoon kids. We don’t send them to dark rooms,” Figler added.

He also commended the researchers’ decision to examine data about concussions linked to limited contact sports. In contact sports, participants may be more likely to anticipate and prepare for a hit. That’s not the case with injuries sustained in limited contact sports.

“Dodgeball is basically a sucker punch. That’s why these kids have so many concussions,” said Figler. “They typically don’t see the ball coming, or they can’t get out of the way, and they can’t tense themselves to take that blow.”

The Predicting and Preventing Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research-Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Team. Ledoux reported receiving grants from the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Foundation, Ontario Brain Institute, and University of Ottawa Brain and Mind Research Institute. She received nonfinancial support from Mobio Interactive outside the submitted work. Zuckerman reported receiving personal fees from the National Football League and Medtronic outside the submitted work. Figler had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Clinicians More Likely to Flag Black Kids’ Injuries as Abuse

TOPLINE:

Among children with traumatic injury, those of Black ethnicity are more likely than those of White ethnicity to be suspected of experiencing child abuse. Young patients and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds also face an increased likelihood of suspicion for child abuse (SCA).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data on pediatric patients admitted to hospitals after sustaining a traumatic injury between 2006 and 2016 using the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) to investigate racial and ethnic disparities in cases in which SCA codes from the 9th and 10th editions of the International Classification of Diseases were used.

- The analysis included a weighted total of 634,309 pediatric patients with complete data, comprising 13,579 patients in the SCA subgroup and 620,730 in the non-SCA subgroup.

- Patient demographics, injury severity, and hospitalization characteristics were classified by race and ethnicity.

- The primary outcome was differences in racial and ethnic composition between the SCA and non-SCA groups, as well as compared with the overall US population using 2010 US Census data.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black patients had 75% higher odds of having a SCA code, compared with White patients; the latter ethnicity was relatively underrepresented in the SCA subgroup, compared with the distribution reported by the US Census.

- Black patients had 10% higher odds of having a SCA code (odds ratio, 1.10; P =.004) than White patients, after socioeconomic factors such as insurance type, household income based on zip code, and injury severity were controlled for.

- Black patients in the SCA subgroup experienced a 26.5% (P < .001) longer hospital stay for mild to moderate injuries and a 40.1% (P < .001) longer stay for serious injuries compared with White patients.

- Patients in the SCA subgroup were significantly younger (mean, 1.70 years vs 9.70 years), were more likely to have Medicaid insurance (76.6% vs 42.0%), and had higher mortality rates (5.6% vs 1.0%) than those in the non-SCA subgroup; they were also more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and present with more severe injuries.

IN PRACTICE:

“However, we can identify and appropriately respond to patients with potential child abuse in an equitable way by using clinical decision support tools, seeking clinical consultation of child abuse pediatricians, practicing cultural humility, and enhancing the education and training for health care professionals on child abuse recognition, response, and prevention,” Allison M. Jackson, MD, MPH, of the Child and Adolescent Protection Center at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Fereshteh Salimi-Jazi, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine in California. It was published online on December 18, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study relied on data from KID, which has limitations such as potential coding errors and the inability to follow patients over time. The database combines race and ethnicity in a single field as well. The study only included hospitalized patients, which may not represent all clinician suspicions of SCA cases.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among children with traumatic injury, those of Black ethnicity are more likely than those of White ethnicity to be suspected of experiencing child abuse. Young patients and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds also face an increased likelihood of suspicion for child abuse (SCA).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data on pediatric patients admitted to hospitals after sustaining a traumatic injury between 2006 and 2016 using the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) to investigate racial and ethnic disparities in cases in which SCA codes from the 9th and 10th editions of the International Classification of Diseases were used.

- The analysis included a weighted total of 634,309 pediatric patients with complete data, comprising 13,579 patients in the SCA subgroup and 620,730 in the non-SCA subgroup.

- Patient demographics, injury severity, and hospitalization characteristics were classified by race and ethnicity.

- The primary outcome was differences in racial and ethnic composition between the SCA and non-SCA groups, as well as compared with the overall US population using 2010 US Census data.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black patients had 75% higher odds of having a SCA code, compared with White patients; the latter ethnicity was relatively underrepresented in the SCA subgroup, compared with the distribution reported by the US Census.

- Black patients had 10% higher odds of having a SCA code (odds ratio, 1.10; P =.004) than White patients, after socioeconomic factors such as insurance type, household income based on zip code, and injury severity were controlled for.

- Black patients in the SCA subgroup experienced a 26.5% (P < .001) longer hospital stay for mild to moderate injuries and a 40.1% (P < .001) longer stay for serious injuries compared with White patients.

- Patients in the SCA subgroup were significantly younger (mean, 1.70 years vs 9.70 years), were more likely to have Medicaid insurance (76.6% vs 42.0%), and had higher mortality rates (5.6% vs 1.0%) than those in the non-SCA subgroup; they were also more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and present with more severe injuries.

IN PRACTICE:

“However, we can identify and appropriately respond to patients with potential child abuse in an equitable way by using clinical decision support tools, seeking clinical consultation of child abuse pediatricians, practicing cultural humility, and enhancing the education and training for health care professionals on child abuse recognition, response, and prevention,” Allison M. Jackson, MD, MPH, of the Child and Adolescent Protection Center at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Fereshteh Salimi-Jazi, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine in California. It was published online on December 18, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study relied on data from KID, which has limitations such as potential coding errors and the inability to follow patients over time. The database combines race and ethnicity in a single field as well. The study only included hospitalized patients, which may not represent all clinician suspicions of SCA cases.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among children with traumatic injury, those of Black ethnicity are more likely than those of White ethnicity to be suspected of experiencing child abuse. Young patients and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds also face an increased likelihood of suspicion for child abuse (SCA).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers analyzed data on pediatric patients admitted to hospitals after sustaining a traumatic injury between 2006 and 2016 using the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) to investigate racial and ethnic disparities in cases in which SCA codes from the 9th and 10th editions of the International Classification of Diseases were used.

- The analysis included a weighted total of 634,309 pediatric patients with complete data, comprising 13,579 patients in the SCA subgroup and 620,730 in the non-SCA subgroup.

- Patient demographics, injury severity, and hospitalization characteristics were classified by race and ethnicity.

- The primary outcome was differences in racial and ethnic composition between the SCA and non-SCA groups, as well as compared with the overall US population using 2010 US Census data.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black patients had 75% higher odds of having a SCA code, compared with White patients; the latter ethnicity was relatively underrepresented in the SCA subgroup, compared with the distribution reported by the US Census.

- Black patients had 10% higher odds of having a SCA code (odds ratio, 1.10; P =.004) than White patients, after socioeconomic factors such as insurance type, household income based on zip code, and injury severity were controlled for.

- Black patients in the SCA subgroup experienced a 26.5% (P < .001) longer hospital stay for mild to moderate injuries and a 40.1% (P < .001) longer stay for serious injuries compared with White patients.

- Patients in the SCA subgroup were significantly younger (mean, 1.70 years vs 9.70 years), were more likely to have Medicaid insurance (76.6% vs 42.0%), and had higher mortality rates (5.6% vs 1.0%) than those in the non-SCA subgroup; they were also more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and present with more severe injuries.

IN PRACTICE:

“However, we can identify and appropriately respond to patients with potential child abuse in an equitable way by using clinical decision support tools, seeking clinical consultation of child abuse pediatricians, practicing cultural humility, and enhancing the education and training for health care professionals on child abuse recognition, response, and prevention,” Allison M. Jackson, MD, MPH, of the Child and Adolescent Protection Center at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Fereshteh Salimi-Jazi, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine in California. It was published online on December 18, 2024, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study relied on data from KID, which has limitations such as potential coding errors and the inability to follow patients over time. The database combines race and ethnicity in a single field as well. The study only included hospitalized patients, which may not represent all clinician suspicions of SCA cases.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Nodding Off While Feeding an Infant

In a recent survey of 1259 mothers published in the journal Pediatrics, 28% reported they had fallen asleep while feeding their babies, and 83% of those mothers reported that the sleep was unplanned. Although the study sample was small, the investigators found that sociodemographic factors did not increase the odds that a mother would fall asleep while feeding.

These numbers are not surprising, but nonetheless they are concerning because co-sleeping is a known risk factor for sudden unexplained infant death (SUID). Every parent will tell you during the first 6 months of their adventure in parenting they didn’t get enough sleep. In fact some will tell you that sleep deprivation was their chronic state for the child’s first year.

Falling asleep easily at times and places not intended for sleep is the primary symptom of sleep deprivation. SUID is the most tragic event associated with parental sleep deprivation, but it is certainly not the only one. Overtired parents are more likely to be involved in accidents and are more likely to make poor decisions, particularly those regarding how to respond to a crying or misbehaving child.

The investigators found that 24% of mothers who reported that their usual nighttime feeding location was a chair or sofa (14%). Not surprisingly, mothers who fed in chairs were less likely to fall asleep while feeding. Many of these mothers reported that they chose the chair because they thought they would be less likely to fall asleep and/or disturb other family members. One wonders how we should interpret these numbers in light of other research that has found it is “relatively less hazardous to fall asleep with an infant in the adult bed than on a chair or sofa.” Had these chair feeding mothers made the better choice under the circumstances? It would take a much larger and more granular study to answer that question.

Mothers who exclusively breastfed were more likely to fall asleep feeding than were those who partially breastfed or used formula. The investigators postulated that the infants of mothers who exclusively breastfed may have required more feedings because breast milk is more easily and quickly digested. I know this is a common explanation, but in my experience I have found that exclusively breastfed infants often use nursing as pacification and a sleep trigger and spend more time at the breast regardless of how quickly they emptied their stomachs.

This study also examined the effect of repeated educational interventions and support and found that mothers who received an intervention based on safe sleep practices were less likely to fall asleep while feeding than were the mothers who had received the intervention focused on exclusive breastfeeding value and barriers to its adoption.

Education is one avenue, particularly when it includes the mother’s partner who can play an important role as standby lifeguard to make sure the mother doesn’t fall asleep. Obviously, this is easier said than done because when there is a new baby in the house sleep deprivation is usually a shared experience.

Although I believe that my family is on the verge of gifting me a smartwatch to protect me from my own misadventures, I don’t have any personal experience with these wonders of modern technology. However, I suspect with very little tweaking a wearable sensor could be easily programmed to detect when a mother is beginning to fall asleep while she is feeding her infant. A smartwatch would be an expensive intervention and is unlikely to filter down to economically challenged families. On the other hand, this paper has reinforced our suspicions that sleep-deprived infant feeding is a significant problem. A subsidized loaner program for those families that can’t afford a smartwatch is an option that should be considered.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In a recent survey of 1259 mothers published in the journal Pediatrics, 28% reported they had fallen asleep while feeding their babies, and 83% of those mothers reported that the sleep was unplanned. Although the study sample was small, the investigators found that sociodemographic factors did not increase the odds that a mother would fall asleep while feeding.

These numbers are not surprising, but nonetheless they are concerning because co-sleeping is a known risk factor for sudden unexplained infant death (SUID). Every parent will tell you during the first 6 months of their adventure in parenting they didn’t get enough sleep. In fact some will tell you that sleep deprivation was their chronic state for the child’s first year.

Falling asleep easily at times and places not intended for sleep is the primary symptom of sleep deprivation. SUID is the most tragic event associated with parental sleep deprivation, but it is certainly not the only one. Overtired parents are more likely to be involved in accidents and are more likely to make poor decisions, particularly those regarding how to respond to a crying or misbehaving child.

The investigators found that 24% of mothers who reported that their usual nighttime feeding location was a chair or sofa (14%). Not surprisingly, mothers who fed in chairs were less likely to fall asleep while feeding. Many of these mothers reported that they chose the chair because they thought they would be less likely to fall asleep and/or disturb other family members. One wonders how we should interpret these numbers in light of other research that has found it is “relatively less hazardous to fall asleep with an infant in the adult bed than on a chair or sofa.” Had these chair feeding mothers made the better choice under the circumstances? It would take a much larger and more granular study to answer that question.

Mothers who exclusively breastfed were more likely to fall asleep feeding than were those who partially breastfed or used formula. The investigators postulated that the infants of mothers who exclusively breastfed may have required more feedings because breast milk is more easily and quickly digested. I know this is a common explanation, but in my experience I have found that exclusively breastfed infants often use nursing as pacification and a sleep trigger and spend more time at the breast regardless of how quickly they emptied their stomachs.

This study also examined the effect of repeated educational interventions and support and found that mothers who received an intervention based on safe sleep practices were less likely to fall asleep while feeding than were the mothers who had received the intervention focused on exclusive breastfeeding value and barriers to its adoption.

Education is one avenue, particularly when it includes the mother’s partner who can play an important role as standby lifeguard to make sure the mother doesn’t fall asleep. Obviously, this is easier said than done because when there is a new baby in the house sleep deprivation is usually a shared experience.

Although I believe that my family is on the verge of gifting me a smartwatch to protect me from my own misadventures, I don’t have any personal experience with these wonders of modern technology. However, I suspect with very little tweaking a wearable sensor could be easily programmed to detect when a mother is beginning to fall asleep while she is feeding her infant. A smartwatch would be an expensive intervention and is unlikely to filter down to economically challenged families. On the other hand, this paper has reinforced our suspicions that sleep-deprived infant feeding is a significant problem. A subsidized loaner program for those families that can’t afford a smartwatch is an option that should be considered.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In a recent survey of 1259 mothers published in the journal Pediatrics, 28% reported they had fallen asleep while feeding their babies, and 83% of those mothers reported that the sleep was unplanned. Although the study sample was small, the investigators found that sociodemographic factors did not increase the odds that a mother would fall asleep while feeding.

These numbers are not surprising, but nonetheless they are concerning because co-sleeping is a known risk factor for sudden unexplained infant death (SUID). Every parent will tell you during the first 6 months of their adventure in parenting they didn’t get enough sleep. In fact some will tell you that sleep deprivation was their chronic state for the child’s first year.

Falling asleep easily at times and places not intended for sleep is the primary symptom of sleep deprivation. SUID is the most tragic event associated with parental sleep deprivation, but it is certainly not the only one. Overtired parents are more likely to be involved in accidents and are more likely to make poor decisions, particularly those regarding how to respond to a crying or misbehaving child.

The investigators found that 24% of mothers who reported that their usual nighttime feeding location was a chair or sofa (14%). Not surprisingly, mothers who fed in chairs were less likely to fall asleep while feeding. Many of these mothers reported that they chose the chair because they thought they would be less likely to fall asleep and/or disturb other family members. One wonders how we should interpret these numbers in light of other research that has found it is “relatively less hazardous to fall asleep with an infant in the adult bed than on a chair or sofa.” Had these chair feeding mothers made the better choice under the circumstances? It would take a much larger and more granular study to answer that question.

Mothers who exclusively breastfed were more likely to fall asleep feeding than were those who partially breastfed or used formula. The investigators postulated that the infants of mothers who exclusively breastfed may have required more feedings because breast milk is more easily and quickly digested. I know this is a common explanation, but in my experience I have found that exclusively breastfed infants often use nursing as pacification and a sleep trigger and spend more time at the breast regardless of how quickly they emptied their stomachs.

This study also examined the effect of repeated educational interventions and support and found that mothers who received an intervention based on safe sleep practices were less likely to fall asleep while feeding than were the mothers who had received the intervention focused on exclusive breastfeeding value and barriers to its adoption.

Education is one avenue, particularly when it includes the mother’s partner who can play an important role as standby lifeguard to make sure the mother doesn’t fall asleep. Obviously, this is easier said than done because when there is a new baby in the house sleep deprivation is usually a shared experience.

Although I believe that my family is on the verge of gifting me a smartwatch to protect me from my own misadventures, I don’t have any personal experience with these wonders of modern technology. However, I suspect with very little tweaking a wearable sensor could be easily programmed to detect when a mother is beginning to fall asleep while she is feeding her infant. A smartwatch would be an expensive intervention and is unlikely to filter down to economically challenged families. On the other hand, this paper has reinforced our suspicions that sleep-deprived infant feeding is a significant problem. A subsidized loaner program for those families that can’t afford a smartwatch is an option that should be considered.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Fibrosis Risk High in Young Adults With Both Obesity and T2D

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers aimed to assess the prevalence of hepatic steatosis and clinically significant fibrosis (stage ≥ 2) in young adults without a history of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), hypothesizing that the rates would be comparable with those in older adults, especially in the presence of cardiometabolic risk factors.

- Overall, 1420 participants aged 21-79 years with or without T2D (63% or 37%, respectively) were included from outpatient clinics at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, and divided into two age groups: < 45 years (n = 243) and ≥ 45 years (n = 1177).

- All the participants underwent assessment of liver stiffness via transient elastography, with magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) or liver biopsy recommended when indicated.

- Participants also underwent a medical history review, physical examination, and fasting blood tests to rule out secondary causes of liver disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 52% of participants had hepatic steatosis, and 9.5% had clinically significant fibrosis.

- There were no significant differences in the frequencies of hepatic steatosis (50.2% vs 52.7%; P = .6) or clinically significant hepatic fibrosis (7.5% vs 9.9%; P = .2) observed between young and older adults.

- The presence of either T2D or obesity was linked to an increased prevalence of both hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in both the age groups (P < .01).

- In young and older adults, the presence of both T2D and obesity led to the highest rates of both hepatic steatosis and clinically significant fibrosis, with the latter rate being statistically similar between the groups (15.7% vs 17.3%; P = .2).

- The presence of T2D and obesity was the strongest risk factors for hepatic fibrosis in young adults (odds ratios, 4.33 and 1.16, respectively; P < .05 for both).

IN PRACTICE:

“The clinical implication is that young adults with obesity and T2D carry a high risk of future cirrhosis, possibly as high as older adults, and must be aggressively screened at the first visit and carefully followed,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Anu Sharma, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, was published online in Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The diagnosis of clinically significant hepatic fibrosis was confirmed via MRE and/or liver biopsy in only 30% of all participants. The study population included a slightly higher proportion of young adults with obesity, T2D, and other cardiometabolic risk factors than that in national averages, which may have limited its generalizability. Genetic variants associated with MASLD were not included in this study.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded partly by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Echosens. One author disclosed receiving research support and serving as a consultant for various pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers aimed to assess the prevalence of hepatic steatosis and clinically significant fibrosis (stage ≥ 2) in young adults without a history of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), hypothesizing that the rates would be comparable with those in older adults, especially in the presence of cardiometabolic risk factors.

- Overall, 1420 participants aged 21-79 years with or without T2D (63% or 37%, respectively) were included from outpatient clinics at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, and divided into two age groups: < 45 years (n = 243) and ≥ 45 years (n = 1177).

- All the participants underwent assessment of liver stiffness via transient elastography, with magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) or liver biopsy recommended when indicated.

- Participants also underwent a medical history review, physical examination, and fasting blood tests to rule out secondary causes of liver disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 52% of participants had hepatic steatosis, and 9.5% had clinically significant fibrosis.

- There were no significant differences in the frequencies of hepatic steatosis (50.2% vs 52.7%; P = .6) or clinically significant hepatic fibrosis (7.5% vs 9.9%; P = .2) observed between young and older adults.

- The presence of either T2D or obesity was linked to an increased prevalence of both hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in both the age groups (P < .01).

- In young and older adults, the presence of both T2D and obesity led to the highest rates of both hepatic steatosis and clinically significant fibrosis, with the latter rate being statistically similar between the groups (15.7% vs 17.3%; P = .2).

- The presence of T2D and obesity was the strongest risk factors for hepatic fibrosis in young adults (odds ratios, 4.33 and 1.16, respectively; P < .05 for both).

IN PRACTICE:

“The clinical implication is that young adults with obesity and T2D carry a high risk of future cirrhosis, possibly as high as older adults, and must be aggressively screened at the first visit and carefully followed,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Anu Sharma, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, was published online in Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The diagnosis of clinically significant hepatic fibrosis was confirmed via MRE and/or liver biopsy in only 30% of all participants. The study population included a slightly higher proportion of young adults with obesity, T2D, and other cardiometabolic risk factors than that in national averages, which may have limited its generalizability. Genetic variants associated with MASLD were not included in this study.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded partly by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Echosens. One author disclosed receiving research support and serving as a consultant for various pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers aimed to assess the prevalence of hepatic steatosis and clinically significant fibrosis (stage ≥ 2) in young adults without a history of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), hypothesizing that the rates would be comparable with those in older adults, especially in the presence of cardiometabolic risk factors.

- Overall, 1420 participants aged 21-79 years with or without T2D (63% or 37%, respectively) were included from outpatient clinics at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, and divided into two age groups: < 45 years (n = 243) and ≥ 45 years (n = 1177).

- All the participants underwent assessment of liver stiffness via transient elastography, with magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) or liver biopsy recommended when indicated.

- Participants also underwent a medical history review, physical examination, and fasting blood tests to rule out secondary causes of liver disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 52% of participants had hepatic steatosis, and 9.5% had clinically significant fibrosis.

- There were no significant differences in the frequencies of hepatic steatosis (50.2% vs 52.7%; P = .6) or clinically significant hepatic fibrosis (7.5% vs 9.9%; P = .2) observed between young and older adults.

- The presence of either T2D or obesity was linked to an increased prevalence of both hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in both the age groups (P < .01).

- In young and older adults, the presence of both T2D and obesity led to the highest rates of both hepatic steatosis and clinically significant fibrosis, with the latter rate being statistically similar between the groups (15.7% vs 17.3%; P = .2).

- The presence of T2D and obesity was the strongest risk factors for hepatic fibrosis in young adults (odds ratios, 4.33 and 1.16, respectively; P < .05 for both).

IN PRACTICE:

“The clinical implication is that young adults with obesity and T2D carry a high risk of future cirrhosis, possibly as high as older adults, and must be aggressively screened at the first visit and carefully followed,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study, led by Anu Sharma, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, was published online in Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The diagnosis of clinically significant hepatic fibrosis was confirmed via MRE and/or liver biopsy in only 30% of all participants. The study population included a slightly higher proportion of young adults with obesity, T2D, and other cardiometabolic risk factors than that in national averages, which may have limited its generalizability. Genetic variants associated with MASLD were not included in this study.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded partly by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Echosens. One author disclosed receiving research support and serving as a consultant for various pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Limb loss is a significant and growing concern in the United States. Nearly 2 million Americans are living with limb loss, and up to 185,000 people undergo amputations annually.1-4 Of these patients, about 35% are women.5 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides about 10% of US amputations.6-8 Between 2015 and 2019, the number of prosthetic devices provided to female veterans increased from 3.3 million to 4.6 million.5,9,10

Previous research identified disparities in prosthetic care between men and women, both within and outside the VHA. These disparities include slower prosthesis prescription and receipt among women, in addition to differences in self-reported mobility, satisfaction, rates of prosthesis rejection, and challenges related to prosthesis appearance and fit.5,10,11 Recent studies suggest women tend to have worse outcomes following amputation, and are underrepresented in amputation research.12,13 However, these disparities are poorly described in a large, national sample. Because women represent a growing portion of patients with limb loss in the VHA, understanding their needs is critical.14

The Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, MD Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020 was enacted, in part, to improve the care provided to women veterans.15 The law required the VHA to conduct a survey of ≥ 50,000 veterans to assess the satisfaction of women veterans with prostheses provided by the VHA. To comply with this legislation and understand how women veterans rate their prostheses and related care in the VHA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for Collaborative Evaluation (VACE) conducted a large national survey of veterans with limb loss that oversampled women veterans. This article describes the survey results, including characteristics of female veterans with limb loss receiving care from the VHA, assesses their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care, and highlights where their responses differ from those of male veterans.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, mixedmode survey of eligible amputees in the VHA Support Service Capital Assets Amputee Data Cube. We identified a cohort of veterans with any major amputation (above the ankle or wrist) or partial hand or foot amputation who received VHA care between October 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020. The final cohort yielded 46,646 potentially eligible veterans. Thirty-three had invalid contact information, leaving 46,613 veterans who were asked to participate, including 1356 women.

Survey

We created a survey instrument de novo that included questions from validated instruments, including the Trinity Amputation Prosthesis and Experience Scales to assess prosthetic device satisfaction, the Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire to assess quality of life (QOL) satisfaction, and the Orthotics Prosthetics Users Survey to assess prosthesis-related care satisfaction. 16-18 Additional questions were incorporated from a survey of veterans with upper limb amputation to assess the importance of cosmetic considerations related to the prosthesis and comfort with prosthesis use in intimate relationships.19 Questions were also included to assess amputation type, year of amputation, if a prosthesis was currently used, reasons for ceasing use of a prosthesis, reasons for never using a prosthesis, the types of prostheses used, intensity of prosthesis use, satisfaction with time required to receive a prosthetic limb, and if the prosthesis reflected the veteran’s selfidentified gender. Veterans were asked to answer questions based on their most recent amputation.

We tested the survey using cognitive interviews with 6 veterans to refine the survey and better understand how veterans interpreted the questions. Pilot testers completed the survey and participated in individual interviews with experienced interviewers (CL and RRK) to describe how they selected their responses.20 This feedback was used to refine the survey. The online survey was programmed using Qualtrics Software and manually translated into Spanish.

Given the multimodal design, surveys were distributed by email, text message, and US Postal Service (USPS). Surveys were emailed to all veterans for whom a valid email address was available. If emails were undeliverable, veterans were contacted via text message or the USPS. Surveys were distributed by text message to all veterans without an email address but with a cellphone number. We were unable to consistently identify invalid numbers among all text message recipients. Invitations with a survey URL and QR code were sent via USPS to veterans who had no valid email address or cellphone number. Targeted efforts were made to increase the response rate for women. A random sample of 200 women who had not completed the survey 2 weeks prior to the closing date (15% of women in sample) was selected to receive personal phone calls. Another random sample of 400 women was selected to receive personalized outreach emails. The survey data were confidential, and responses could not be traced to identifying information.

Data Analyses

We conducted a descriptive analysis, including percentages and means for responses to variables focused on describing amputation characteristics, prosthesis characteristics, and QOL. All data, including missing values, were used to document the percentage of respondents for each question. Removing missing data from the denominator when calculating percentages could introduce bias to the analysis because we cannot be certain data are missing at random. Missing variables were removed to avoid underinflation of mean scores.

We compared responses across 2 groups: individuals who self-identified as men and individuals who self-identified as women. For each question, we assessed whether each of these groups differed significantly from the remaining sample. For example, we examined whether the percentage of men who answered affirmatively to a question was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as male, and whether the percentage of women who answered affirmatively was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as female. We utilized x2 tests to determine significant differences for percentage calculations and t tests to determine significant differences in means across gender.

Since conducting multiple comparisons within a dataset may result in inflating statistical significance (type 1 errors), we used a more conservative estimate of statistical significance (α = 0.01) and high significance (α = 0.001). This study was deemed quality improvement by the VHA Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services (12RPS) and acknowledged by the VA Research Office at Eastern Colorado Health Care System and was not subject to institutional review board review.

Results

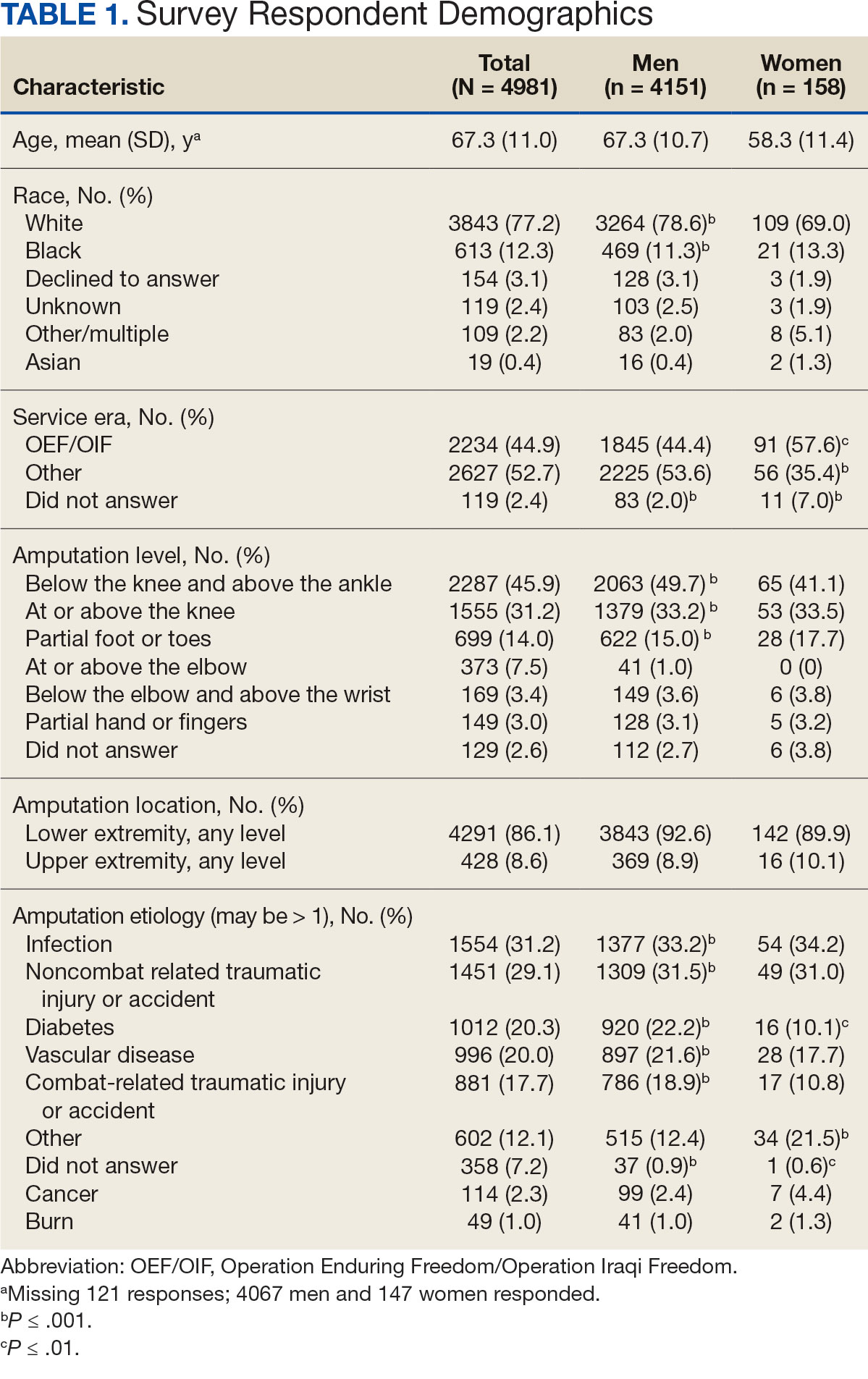

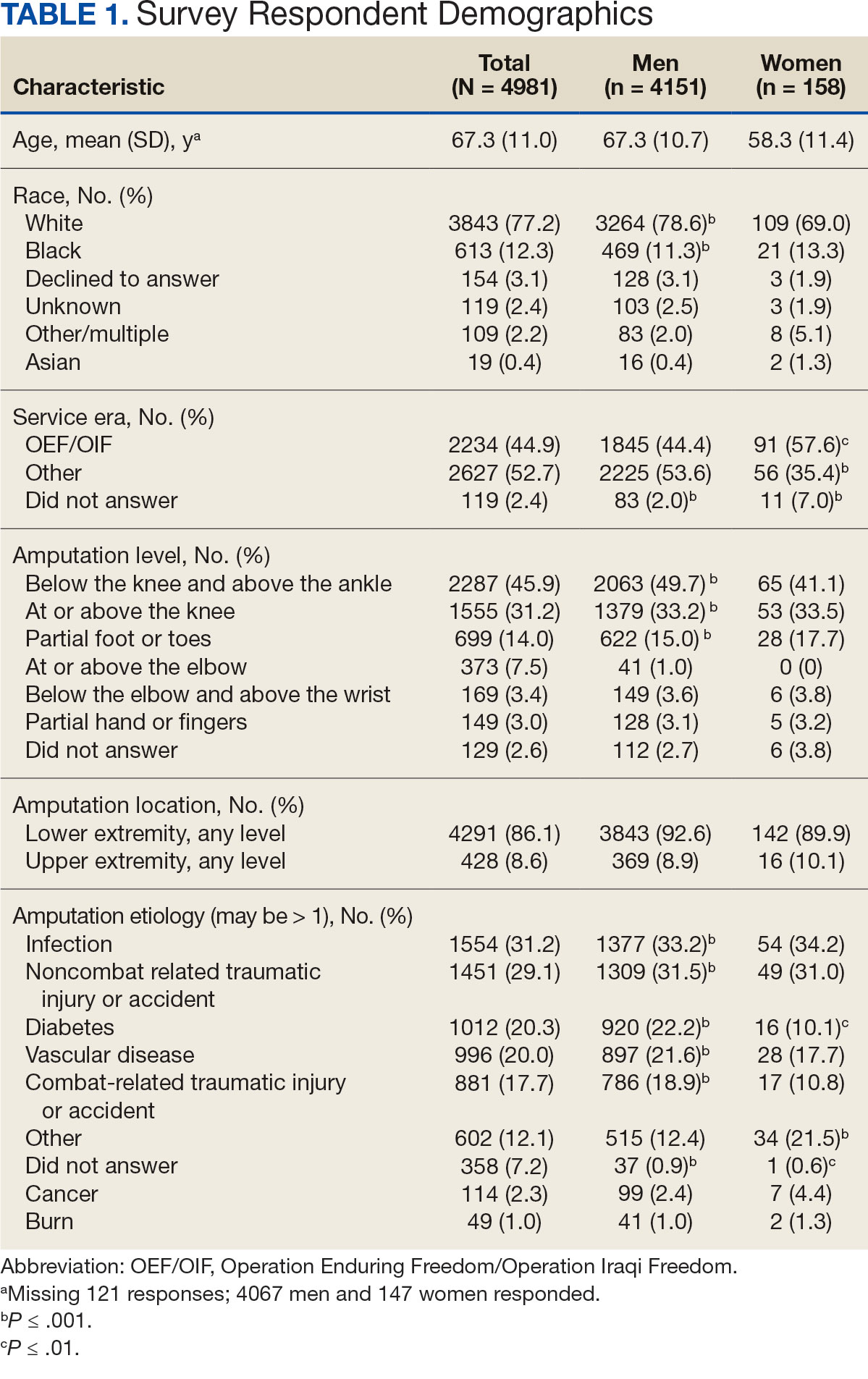

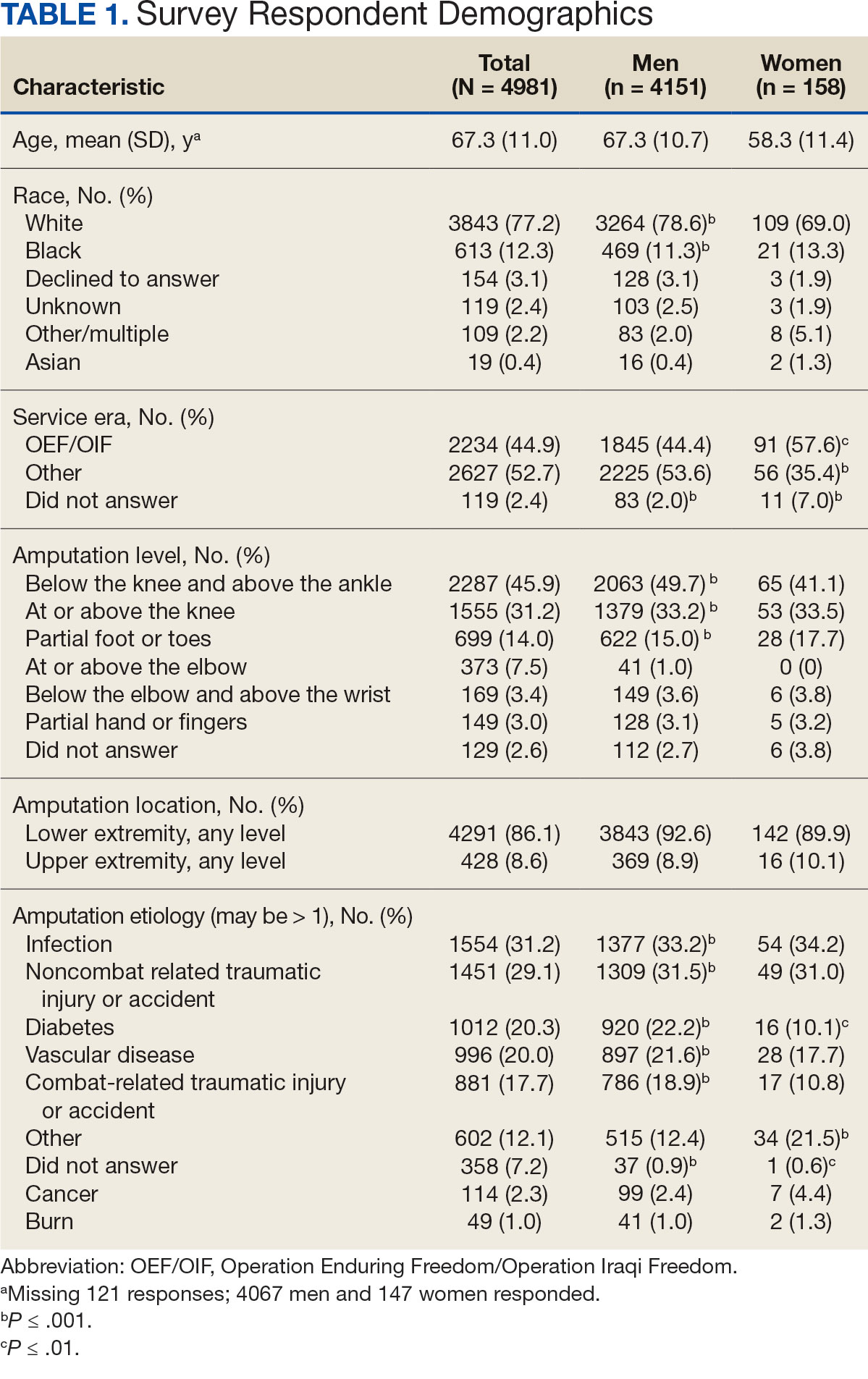

Surveys were distributed to 46,613 veterans and were completed by 4981 respondents for a 10.7% overall response rate. Survey respondents were generally similar to the eligible population invited to participate, but the proportion of women who completed the survey was higher than the proportion of women eligible to participate (2.0% of eligible population vs 16.7% of respondents), likely due to specific efforts to target women. Survey respondents were slightly younger than the general population (67.3 years vs 68.7 years), less likely to be male (97.1% vs 83.3%), showed similar representation of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans (4.4% vs 4.1%), and were less likely to have diabetes (58.0% vs 52.7% had diabetes) (Table 1).