User login

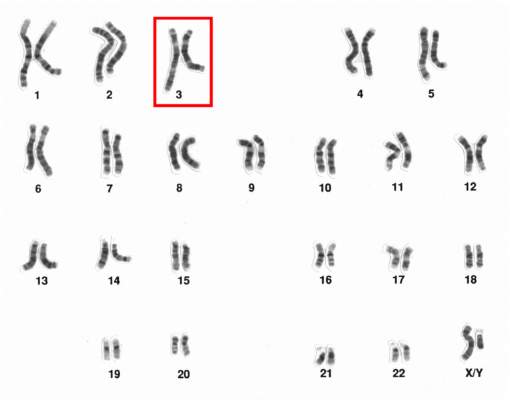

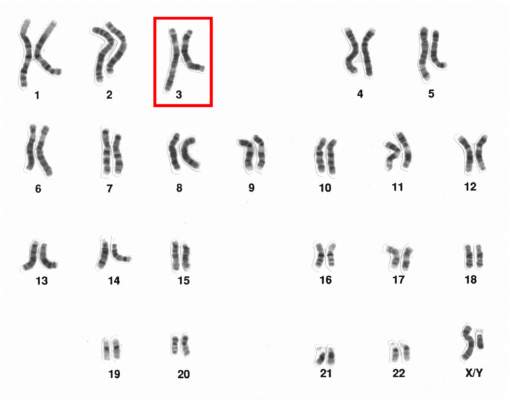

Chromosome 3 abnormalities linked to poor CML outcomes

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities linked to poor CML outcomes

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Chromosome 3 abnormalities, specifically 3q26.2 rearrangements, were associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), report Dr. Wei Wang and coauthors of the department of hematopathology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

A study of 2,013 CML patients found that just 6% of those with 3q26.2 abnormalities achieved complete cytogenetic response during the course of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment. Patients with other chromosome 3 abnormalities had a significantly better response rate of 42% the investigators found.

Additionally, patients with 3q26.2 chromosome rearrangements had significantly worse survival rates than those with abnormalities involving other chromosomes, with 2-year overall survival rates of 22% and 60%, respectively.

The lack of response to TKI treatment “raises the issue of how to manage these patients,” Dr. Wang and associates said in the report.

“TKIs themselves are not sufficient to control the disease with 3q26.2 abnormalities,” they added. “Intensive therapy, stem cell transplantation, or investigational therapy targeted to EVI1 should be considered,” concluded the authors, who declared that they had no competing financial interests.

Read the full article in Blood.

Dear insurance companies: Stop sending me unnecessary reminder letters

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Dear insurance companies: Stop sending me unnecessary reminder letters

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I am, apparently, not a very good doctor. At least, that’s what some mailings I get from insurance companies make me think.

You probably get the same ones. They tell me what guidelines I’m not following or drug interactions I’m not mindful of. I suppose I should be grateful for their efforts to protect patients.

Letters I’ve gotten in the last week have reminded me that:

• Patients with elevated fasting blood sugars should be started on metformin.

• A lady on Eliquis (apixaban) after developing a deep-vein thrombosis should be considered for a less costly alternative, such as warfarin, to help her save money.

• An antihypertensive agent is recommended for a young man with persistently elevated blood pressures.

• An older gentleman’s lipid-lowering agent may interfere with his diabetes medication.

What do these have to do with anything that I, as a neurologist, am doing for the patient? Nothing.

Why are they being sent to me, as opposed to an internist or cardiologist? I have no idea. Of course, for all I know, the other docs might be getting recommendations on how to manage Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

The insurance companies pay the bills. They obviously know which doctors are seeing who and prescribing what. Their billing systems track who practices what specialty. If I were to try submitting a claim for pulmonary evaluation, I’m sure they’d immediately notice and deny it.

So why can’t they get this straight? It seems like a big waste of time, paper, and postage all around.

On rare occasions, they actually get it right … sort of. About a month ago, I received a letter about a migraine patient, telling me that, for those with frequent migraines, a preventive medication should be considered. It even listed her current prescriptions to help me understand.

I absolutely agree with the letter, but it completely ignored that her medication list already included topiramate and nortriptyline, both commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Since she has no other reason to be on either, I have no idea why they thought I’d use them. These kinds of notes all end with some generic comment that these are just suggestions, and only I and my patient can make the correct decisions about treatment, etc. etc.

That letter may be well intentioned, perhaps, but it is also inaccurate, unnecessary, and – to me – even a little demeaning. If you don’t think I know what I’m doing, then why are you sending patients to me? Maybe the software you’re using to screen charts and send these letters should open its own practice instead.

If the real goal of these letters is to save money (and we all know it is), then why is the company wasting it on redundant and inaccurate letters, usually not even sent to the correct doctor?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Technology Allows Independent Living for Elderly

NEW YORK - Shari Cayle, 75, called "Miracle Mama" by her family ever since she beat back advanced colon cancer seven years ago, is still undergoing treatment and living alone.

"I don't want my grandchildren to remember me as the sick one, I want to be the fun one," said Cayle, who is testing a device that passively monitors her activity. "My family knows what I'm doing and I don't think they should have to change their life around to make sure I'm OK."

Onkol, a product inspired by Cayle that monitors her front door, reminds her when to take her medication and can alert her family if she falls, has allowed her to remain independent at home. Devised by her son Marc, it will hit the U.S. market next year.

As more American seniors plan to remain at home rather than enter a nursing facility, new startups and some well-known technology brands are connecting them to family and healthcare providers.

The noninvasive devices sit in the background as users go about their normal routine. Through Bluetooth technology they are able to gather information and send it to family or doctors when, for example, a sensor reads that a pill box was opened or a wireless medical device such as a glucose monitor is used.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers' Health Research Institute, at-home options like these will disrupt roughly $64 billion of traditional U.S. provider revenue in the next 20 years.

Monitoring devices for the elderly started with products like privately-held Life Alert, which leapt into public awareness nearly 30 years ago with TV ads showing the elderly "Mrs. Fletcher" reaching for her Life Alert pendant and telling an operator, "I've fallen and I can't get up!"

Now companies like Nortek Security & Control and small startups are taking that much further.

The challenge though is that older consumers may not be ready to use the technology and their medical, security and wellness needs may differ significantly. There are also safety and privacy risks.

"There's a lot of potential, but a big gap between what seniors want and what the market can provide," said Harry Wang, director of health and mobile product research at Parks Associates.

NURSE MOLLY

Milwaukee-based Onkol developed a rectangular hub, roughly the size of a tissue box, that passively monitors things like what their blood glucose reading is and when they open their refrigerator. There is also a wristband that can be pressed for help in an emergency.

"The advantage of it is that the person, the patient, doesn't have to worry about hooking it up and doing stuff with the computer, their kids do that," said Cayle, whose son co-founded Onkol.

Sensely is another device used by providers like Kaiser Permanente, based in California, and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Since 2013, its virtual nurse Molly has connected patients with doctors from a mobile device. She asks how they are feeling and lets them know when it is time to take a health reading.

Another startup, San Francisco-based Lively began selling its product to consumers in 2012. Similarly, it collects information from sensors and connects to a smart watch that tracks customers' footsteps, routine and can even call emergency services. Next year it will connect with medical devices, send data to physicians and enable video consultations that can replace some doctor's appointments.

Venture firms including Fenox Venture Capital, Maveron, Capital Midwest Fund and LaunchPad Digital Health have contributed millions of dollars to these startups.

Ideal Life, founded in 2002, which sells it own devices to providers, plans to release its own consumer version next year.

"The clinical community is more open than they've even been before in piloting and testing new technology," said founder Jason Goldberg.

Just this summer, Nortek bought a personal emergency response system called Libris and a healthcare platform from Numera, a health technology company, for $12 million. At the same time, Nortek said some of its smart home customers like ADT Corp want to expand into health and wellness offerings. The goal is to offer software that connects with customers' current systems as well as medical, fitness, emergency and security devices.

"In the smart home and health space today you see a lot of single purpose solutions that don't offer a full connectivity platform, like a smart watch or pressure sensor in a bed," said Mike O'Neal, Nortek Security & Control president. "We're creating that connectivity."

A July study from AARP showed Americans 50 years and older want activity monitors like Fitbit and Jawbone to have more relevant sensors to monitor health conditions and 89% cited difficulties with set up.

"They (companies) have great technology, but when you can't open the package or you can't find directions that's a problem," said Jody Holtzman, senior vice president of thought leadership at AARP.

Such products may help doctors keep up with a growing elderly population. Research firm Gartner estimates that in the next 40 years, one-third of the population in developed countries will be 65 years or older, thus making it impossible to keep everyone who needs care in the hospital.

NEW YORK - Shari Cayle, 75, called "Miracle Mama" by her family ever since she beat back advanced colon cancer seven years ago, is still undergoing treatment and living alone.

"I don't want my grandchildren to remember me as the sick one, I want to be the fun one," said Cayle, who is testing a device that passively monitors her activity. "My family knows what I'm doing and I don't think they should have to change their life around to make sure I'm OK."

Onkol, a product inspired by Cayle that monitors her front door, reminds her when to take her medication and can alert her family if she falls, has allowed her to remain independent at home. Devised by her son Marc, it will hit the U.S. market next year.

As more American seniors plan to remain at home rather than enter a nursing facility, new startups and some well-known technology brands are connecting them to family and healthcare providers.

The noninvasive devices sit in the background as users go about their normal routine. Through Bluetooth technology they are able to gather information and send it to family or doctors when, for example, a sensor reads that a pill box was opened or a wireless medical device such as a glucose monitor is used.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers' Health Research Institute, at-home options like these will disrupt roughly $64 billion of traditional U.S. provider revenue in the next 20 years.

Monitoring devices for the elderly started with products like privately-held Life Alert, which leapt into public awareness nearly 30 years ago with TV ads showing the elderly "Mrs. Fletcher" reaching for her Life Alert pendant and telling an operator, "I've fallen and I can't get up!"

Now companies like Nortek Security & Control and small startups are taking that much further.

The challenge though is that older consumers may not be ready to use the technology and their medical, security and wellness needs may differ significantly. There are also safety and privacy risks.

"There's a lot of potential, but a big gap between what seniors want and what the market can provide," said Harry Wang, director of health and mobile product research at Parks Associates.

NURSE MOLLY

Milwaukee-based Onkol developed a rectangular hub, roughly the size of a tissue box, that passively monitors things like what their blood glucose reading is and when they open their refrigerator. There is also a wristband that can be pressed for help in an emergency.

"The advantage of it is that the person, the patient, doesn't have to worry about hooking it up and doing stuff with the computer, their kids do that," said Cayle, whose son co-founded Onkol.

Sensely is another device used by providers like Kaiser Permanente, based in California, and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Since 2013, its virtual nurse Molly has connected patients with doctors from a mobile device. She asks how they are feeling and lets them know when it is time to take a health reading.

Another startup, San Francisco-based Lively began selling its product to consumers in 2012. Similarly, it collects information from sensors and connects to a smart watch that tracks customers' footsteps, routine and can even call emergency services. Next year it will connect with medical devices, send data to physicians and enable video consultations that can replace some doctor's appointments.

Venture firms including Fenox Venture Capital, Maveron, Capital Midwest Fund and LaunchPad Digital Health have contributed millions of dollars to these startups.

Ideal Life, founded in 2002, which sells it own devices to providers, plans to release its own consumer version next year.

"The clinical community is more open than they've even been before in piloting and testing new technology," said founder Jason Goldberg.

Just this summer, Nortek bought a personal emergency response system called Libris and a healthcare platform from Numera, a health technology company, for $12 million. At the same time, Nortek said some of its smart home customers like ADT Corp want to expand into health and wellness offerings. The goal is to offer software that connects with customers' current systems as well as medical, fitness, emergency and security devices.

"In the smart home and health space today you see a lot of single purpose solutions that don't offer a full connectivity platform, like a smart watch or pressure sensor in a bed," said Mike O'Neal, Nortek Security & Control president. "We're creating that connectivity."

A July study from AARP showed Americans 50 years and older want activity monitors like Fitbit and Jawbone to have more relevant sensors to monitor health conditions and 89% cited difficulties with set up.

"They (companies) have great technology, but when you can't open the package or you can't find directions that's a problem," said Jody Holtzman, senior vice president of thought leadership at AARP.

Such products may help doctors keep up with a growing elderly population. Research firm Gartner estimates that in the next 40 years, one-third of the population in developed countries will be 65 years or older, thus making it impossible to keep everyone who needs care in the hospital.

NEW YORK - Shari Cayle, 75, called "Miracle Mama" by her family ever since she beat back advanced colon cancer seven years ago, is still undergoing treatment and living alone.

"I don't want my grandchildren to remember me as the sick one, I want to be the fun one," said Cayle, who is testing a device that passively monitors her activity. "My family knows what I'm doing and I don't think they should have to change their life around to make sure I'm OK."

Onkol, a product inspired by Cayle that monitors her front door, reminds her when to take her medication and can alert her family if she falls, has allowed her to remain independent at home. Devised by her son Marc, it will hit the U.S. market next year.

As more American seniors plan to remain at home rather than enter a nursing facility, new startups and some well-known technology brands are connecting them to family and healthcare providers.

The noninvasive devices sit in the background as users go about their normal routine. Through Bluetooth technology they are able to gather information and send it to family or doctors when, for example, a sensor reads that a pill box was opened or a wireless medical device such as a glucose monitor is used.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers' Health Research Institute, at-home options like these will disrupt roughly $64 billion of traditional U.S. provider revenue in the next 20 years.

Monitoring devices for the elderly started with products like privately-held Life Alert, which leapt into public awareness nearly 30 years ago with TV ads showing the elderly "Mrs. Fletcher" reaching for her Life Alert pendant and telling an operator, "I've fallen and I can't get up!"

Now companies like Nortek Security & Control and small startups are taking that much further.

The challenge though is that older consumers may not be ready to use the technology and their medical, security and wellness needs may differ significantly. There are also safety and privacy risks.

"There's a lot of potential, but a big gap between what seniors want and what the market can provide," said Harry Wang, director of health and mobile product research at Parks Associates.

NURSE MOLLY

Milwaukee-based Onkol developed a rectangular hub, roughly the size of a tissue box, that passively monitors things like what their blood glucose reading is and when they open their refrigerator. There is also a wristband that can be pressed for help in an emergency.

"The advantage of it is that the person, the patient, doesn't have to worry about hooking it up and doing stuff with the computer, their kids do that," said Cayle, whose son co-founded Onkol.

Sensely is another device used by providers like Kaiser Permanente, based in California, and the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Since 2013, its virtual nurse Molly has connected patients with doctors from a mobile device. She asks how they are feeling and lets them know when it is time to take a health reading.

Another startup, San Francisco-based Lively began selling its product to consumers in 2012. Similarly, it collects information from sensors and connects to a smart watch that tracks customers' footsteps, routine and can even call emergency services. Next year it will connect with medical devices, send data to physicians and enable video consultations that can replace some doctor's appointments.

Venture firms including Fenox Venture Capital, Maveron, Capital Midwest Fund and LaunchPad Digital Health have contributed millions of dollars to these startups.

Ideal Life, founded in 2002, which sells it own devices to providers, plans to release its own consumer version next year.

"The clinical community is more open than they've even been before in piloting and testing new technology," said founder Jason Goldberg.

Just this summer, Nortek bought a personal emergency response system called Libris and a healthcare platform from Numera, a health technology company, for $12 million. At the same time, Nortek said some of its smart home customers like ADT Corp want to expand into health and wellness offerings. The goal is to offer software that connects with customers' current systems as well as medical, fitness, emergency and security devices.

"In the smart home and health space today you see a lot of single purpose solutions that don't offer a full connectivity platform, like a smart watch or pressure sensor in a bed," said Mike O'Neal, Nortek Security & Control president. "We're creating that connectivity."

A July study from AARP showed Americans 50 years and older want activity monitors like Fitbit and Jawbone to have more relevant sensors to monitor health conditions and 89% cited difficulties with set up.

"They (companies) have great technology, but when you can't open the package or you can't find directions that's a problem," said Jody Holtzman, senior vice president of thought leadership at AARP.

Such products may help doctors keep up with a growing elderly population. Research firm Gartner estimates that in the next 40 years, one-third of the population in developed countries will be 65 years or older, thus making it impossible to keep everyone who needs care in the hospital.

Living conditions linked to risk of Hodgkin lymphoma

Photo by Pavel Novak

VIENNA—Living in overcrowded conditions may affect a young person’s risk of developing certain subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to researchers.

They studied more than 600 children and young adults with HL in England and found that patients who lived in areas with more overcrowded households had a lower incidence of nodular sclerosis (NS) HL but a higher incidence of the not-otherwise-specified (NOS) subtype of HL.

“Our findings related to the NS subtype may suggest that the recurrent infections to which children living in overcrowded conditions are likely to have been exposed stimulate their immune systems and, hence, protect them against developing this type of cancer later in their childhood and early adult life,” said Richard McNally, PhD, of Newcastle University in the UK.

“Those who have a genetic susceptibility to HL and have been less exposed to infection through not living in such overcrowded conditions may have less developed immune systems as a result and are therefore at greater risk of developing this subtype.”

Dr McNally and his colleagues added that it’s more difficult to interpret the findings in the NOS group because this subtype of HL is very heterogeneous. The team said the role of chance cannot be ruled out.

They presented this research at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (abstract 1414).

Dr McNally and his colleagues wanted to gain a better understanding of factors that cause HL, so they analyzed a cohort of young HL patients in Northern England, looking at factors such as sex, age, and socio-economic deprivation.

The researchers evaluated 621 cases of HL recorded in the Northern Region Young Persons’ Malignant Disease Registry. Patients were ages 0 to 24 at diagnosis and were diagnosed between 1968 and 2003.

There were 5 different subtypes of HL in this group:

- 247 cases of the NS type

- 143 NOS

- 105 of mixed cellularity

- 58 lymphocyte-rich cases

- 68 “others.”

Age and sex

Overall, more males than females had HL, but the male-female ratio varied by both age group and subtype. The age-standardized rate (ASR) of HL for males was 18.15 per million persons per year, and the ASR for females was 10.52 per million persons per year.

For the NS subtype, there were 130 males and 117 females, but this was reversed at ages 20 to 24, with 72 females and 55 males. The ASR for NS HL at 20 to 24 was 14.26 for males and 18.79 for females.

“That this change takes place after puberty seems to suggest that estrogens may be responsible in some way,” Dr McNally said. “There are a lot of genes directly regulated by sex hormones, and they are obvious suspects. Alternatively, epigenetic changes . . . influencing key genes, induced by sex hormones, may be responsible.”

Overcrowding

The researchers calculated socio-economic deprivation using the 4 components of the Townsend deprivation score: household overcrowding, non-home ownership, unemployment, and households with no car.

They observed a lower incidence of NS HL among those patients living in areas with more overcrowded households. The relative risk of NS HL was 0.88 for a 1% increase in household overcrowding (P<0.001).

For the NOS subtype, the reverse was seen. A 1% increase in household overcrowding was associated with an increased incidence of NOS HL—a relative risk of 1.17.

Overcrowding seemed to have no effect on the incidence of mixed-cellularity HL or lymphocyte-rich HL.

“We knew already that recurrent infections may protect against childhood leukemia, and now it looks as we can add Hodgkin lymphoma and, particularly its NS subtype, to the list,” Dr McNally said. “In order to further investigate the factors involved, prospective studies should investigate the hormonal changes and recurrent infections and their direct link to the risk of lymphoma, but such studies are difficult to do in rare diseases.”

“A practical follow-up would be case-control studies examining biological markers related to exposure to a multitude of infectious agents, and indeed to hormonal status itself, while genetic studies are another possibility.” ![]()

Photo by Pavel Novak

VIENNA—Living in overcrowded conditions may affect a young person’s risk of developing certain subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to researchers.

They studied more than 600 children and young adults with HL in England and found that patients who lived in areas with more overcrowded households had a lower incidence of nodular sclerosis (NS) HL but a higher incidence of the not-otherwise-specified (NOS) subtype of HL.

“Our findings related to the NS subtype may suggest that the recurrent infections to which children living in overcrowded conditions are likely to have been exposed stimulate their immune systems and, hence, protect them against developing this type of cancer later in their childhood and early adult life,” said Richard McNally, PhD, of Newcastle University in the UK.

“Those who have a genetic susceptibility to HL and have been less exposed to infection through not living in such overcrowded conditions may have less developed immune systems as a result and are therefore at greater risk of developing this subtype.”

Dr McNally and his colleagues added that it’s more difficult to interpret the findings in the NOS group because this subtype of HL is very heterogeneous. The team said the role of chance cannot be ruled out.

They presented this research at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (abstract 1414).

Dr McNally and his colleagues wanted to gain a better understanding of factors that cause HL, so they analyzed a cohort of young HL patients in Northern England, looking at factors such as sex, age, and socio-economic deprivation.

The researchers evaluated 621 cases of HL recorded in the Northern Region Young Persons’ Malignant Disease Registry. Patients were ages 0 to 24 at diagnosis and were diagnosed between 1968 and 2003.

There were 5 different subtypes of HL in this group:

- 247 cases of the NS type

- 143 NOS

- 105 of mixed cellularity

- 58 lymphocyte-rich cases

- 68 “others.”

Age and sex

Overall, more males than females had HL, but the male-female ratio varied by both age group and subtype. The age-standardized rate (ASR) of HL for males was 18.15 per million persons per year, and the ASR for females was 10.52 per million persons per year.

For the NS subtype, there were 130 males and 117 females, but this was reversed at ages 20 to 24, with 72 females and 55 males. The ASR for NS HL at 20 to 24 was 14.26 for males and 18.79 for females.

“That this change takes place after puberty seems to suggest that estrogens may be responsible in some way,” Dr McNally said. “There are a lot of genes directly regulated by sex hormones, and they are obvious suspects. Alternatively, epigenetic changes . . . influencing key genes, induced by sex hormones, may be responsible.”

Overcrowding

The researchers calculated socio-economic deprivation using the 4 components of the Townsend deprivation score: household overcrowding, non-home ownership, unemployment, and households with no car.

They observed a lower incidence of NS HL among those patients living in areas with more overcrowded households. The relative risk of NS HL was 0.88 for a 1% increase in household overcrowding (P<0.001).

For the NOS subtype, the reverse was seen. A 1% increase in household overcrowding was associated with an increased incidence of NOS HL—a relative risk of 1.17.

Overcrowding seemed to have no effect on the incidence of mixed-cellularity HL or lymphocyte-rich HL.

“We knew already that recurrent infections may protect against childhood leukemia, and now it looks as we can add Hodgkin lymphoma and, particularly its NS subtype, to the list,” Dr McNally said. “In order to further investigate the factors involved, prospective studies should investigate the hormonal changes and recurrent infections and their direct link to the risk of lymphoma, but such studies are difficult to do in rare diseases.”

“A practical follow-up would be case-control studies examining biological markers related to exposure to a multitude of infectious agents, and indeed to hormonal status itself, while genetic studies are another possibility.” ![]()

Photo by Pavel Novak

VIENNA—Living in overcrowded conditions may affect a young person’s risk of developing certain subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to researchers.

They studied more than 600 children and young adults with HL in England and found that patients who lived in areas with more overcrowded households had a lower incidence of nodular sclerosis (NS) HL but a higher incidence of the not-otherwise-specified (NOS) subtype of HL.

“Our findings related to the NS subtype may suggest that the recurrent infections to which children living in overcrowded conditions are likely to have been exposed stimulate their immune systems and, hence, protect them against developing this type of cancer later in their childhood and early adult life,” said Richard McNally, PhD, of Newcastle University in the UK.

“Those who have a genetic susceptibility to HL and have been less exposed to infection through not living in such overcrowded conditions may have less developed immune systems as a result and are therefore at greater risk of developing this subtype.”

Dr McNally and his colleagues added that it’s more difficult to interpret the findings in the NOS group because this subtype of HL is very heterogeneous. The team said the role of chance cannot be ruled out.

They presented this research at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (abstract 1414).

Dr McNally and his colleagues wanted to gain a better understanding of factors that cause HL, so they analyzed a cohort of young HL patients in Northern England, looking at factors such as sex, age, and socio-economic deprivation.

The researchers evaluated 621 cases of HL recorded in the Northern Region Young Persons’ Malignant Disease Registry. Patients were ages 0 to 24 at diagnosis and were diagnosed between 1968 and 2003.

There were 5 different subtypes of HL in this group:

- 247 cases of the NS type

- 143 NOS

- 105 of mixed cellularity

- 58 lymphocyte-rich cases

- 68 “others.”

Age and sex

Overall, more males than females had HL, but the male-female ratio varied by both age group and subtype. The age-standardized rate (ASR) of HL for males was 18.15 per million persons per year, and the ASR for females was 10.52 per million persons per year.

For the NS subtype, there were 130 males and 117 females, but this was reversed at ages 20 to 24, with 72 females and 55 males. The ASR for NS HL at 20 to 24 was 14.26 for males and 18.79 for females.

“That this change takes place after puberty seems to suggest that estrogens may be responsible in some way,” Dr McNally said. “There are a lot of genes directly regulated by sex hormones, and they are obvious suspects. Alternatively, epigenetic changes . . . influencing key genes, induced by sex hormones, may be responsible.”

Overcrowding

The researchers calculated socio-economic deprivation using the 4 components of the Townsend deprivation score: household overcrowding, non-home ownership, unemployment, and households with no car.

They observed a lower incidence of NS HL among those patients living in areas with more overcrowded households. The relative risk of NS HL was 0.88 for a 1% increase in household overcrowding (P<0.001).

For the NOS subtype, the reverse was seen. A 1% increase in household overcrowding was associated with an increased incidence of NOS HL—a relative risk of 1.17.

Overcrowding seemed to have no effect on the incidence of mixed-cellularity HL or lymphocyte-rich HL.

“We knew already that recurrent infections may protect against childhood leukemia, and now it looks as we can add Hodgkin lymphoma and, particularly its NS subtype, to the list,” Dr McNally said. “In order to further investigate the factors involved, prospective studies should investigate the hormonal changes and recurrent infections and their direct link to the risk of lymphoma, but such studies are difficult to do in rare diseases.”

“A practical follow-up would be case-control studies examining biological markers related to exposure to a multitude of infectious agents, and indeed to hormonal status itself, while genetic studies are another possibility.” ![]()

CHMP grants accelerated assessment for MM drug

Photo by Linda Bartlett

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has agreed to provide accelerated assessment for daratumumab.

The drug is under review as monotherapy for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The CHMP grants accelerated assessment when a product is expected to be of major public health interest, particularly from the point of view of therapeutic innovation.

Accelerated assessment shortens the review period from 210 days to 150 days.

About daratumumab

Daratumumab is an investigational monoclonal antibody that works by binding to CD38 on the surface of MM cells. In doing so, daratumumab triggers the patient’s own immune system to attack MM cells, resulting in cell death through multiple mechanisms of action.

In July 2013, daratumumab was granted orphan drug status by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of plasma cell myeloma.

The drug has been accepted for priority review in the US as monotherapy for MM patients who are refractory to both a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent or who have received 3 or more prior lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

In August 2012, Janssen Biotech, Inc. and Genmab entered an agreement that granted Janssen an exclusive worldwide license to develop, manufacture, and commercialize daratumumab.

Daratumumab trials

The marketing authorization application for daratumumab includes data from the phase 2 MMY2002 (SIRIUS) study, the phase 1/2 GEN501 study, and 3 additional supportive studies.

The GEN501 study enrolled 102 patients with relapsed MM or relapsed MM that was refractory to 2 or more prior lines of therapy. The patients received daratumumab at a range of doses and on a number of different schedules.

The results suggested that daratumumab is most effective at a dose of 16 mg/kg. At this dose, the overall response rate was 36%.

Most adverse events in this study were grade 1 or 2, although serious events did occur.

The SIRIUS study enrolled 124 MM patients who had received 3 or more prior lines of therapy. They received daratumumab at different doses and on different schedules, but 106 of the patients received the drug at 16 mg/kg.

Twenty-nine percent of the 106 patients responded to treatment, and the median duration of response was 7 months. Thirty percent of patients experienced serious adverse events. ![]()

Photo by Linda Bartlett

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has agreed to provide accelerated assessment for daratumumab.

The drug is under review as monotherapy for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The CHMP grants accelerated assessment when a product is expected to be of major public health interest, particularly from the point of view of therapeutic innovation.

Accelerated assessment shortens the review period from 210 days to 150 days.

About daratumumab

Daratumumab is an investigational monoclonal antibody that works by binding to CD38 on the surface of MM cells. In doing so, daratumumab triggers the patient’s own immune system to attack MM cells, resulting in cell death through multiple mechanisms of action.

In July 2013, daratumumab was granted orphan drug status by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of plasma cell myeloma.

The drug has been accepted for priority review in the US as monotherapy for MM patients who are refractory to both a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent or who have received 3 or more prior lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

In August 2012, Janssen Biotech, Inc. and Genmab entered an agreement that granted Janssen an exclusive worldwide license to develop, manufacture, and commercialize daratumumab.

Daratumumab trials

The marketing authorization application for daratumumab includes data from the phase 2 MMY2002 (SIRIUS) study, the phase 1/2 GEN501 study, and 3 additional supportive studies.

The GEN501 study enrolled 102 patients with relapsed MM or relapsed MM that was refractory to 2 or more prior lines of therapy. The patients received daratumumab at a range of doses and on a number of different schedules.

The results suggested that daratumumab is most effective at a dose of 16 mg/kg. At this dose, the overall response rate was 36%.

Most adverse events in this study were grade 1 or 2, although serious events did occur.

The SIRIUS study enrolled 124 MM patients who had received 3 or more prior lines of therapy. They received daratumumab at different doses and on different schedules, but 106 of the patients received the drug at 16 mg/kg.

Twenty-nine percent of the 106 patients responded to treatment, and the median duration of response was 7 months. Thirty percent of patients experienced serious adverse events. ![]()

Photo by Linda Bartlett

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has agreed to provide accelerated assessment for daratumumab.

The drug is under review as monotherapy for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The CHMP grants accelerated assessment when a product is expected to be of major public health interest, particularly from the point of view of therapeutic innovation.

Accelerated assessment shortens the review period from 210 days to 150 days.

About daratumumab

Daratumumab is an investigational monoclonal antibody that works by binding to CD38 on the surface of MM cells. In doing so, daratumumab triggers the patient’s own immune system to attack MM cells, resulting in cell death through multiple mechanisms of action.

In July 2013, daratumumab was granted orphan drug status by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of plasma cell myeloma.

The drug has been accepted for priority review in the US as monotherapy for MM patients who are refractory to both a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent or who have received 3 or more prior lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

In August 2012, Janssen Biotech, Inc. and Genmab entered an agreement that granted Janssen an exclusive worldwide license to develop, manufacture, and commercialize daratumumab.

Daratumumab trials

The marketing authorization application for daratumumab includes data from the phase 2 MMY2002 (SIRIUS) study, the phase 1/2 GEN501 study, and 3 additional supportive studies.

The GEN501 study enrolled 102 patients with relapsed MM or relapsed MM that was refractory to 2 or more prior lines of therapy. The patients received daratumumab at a range of doses and on a number of different schedules.

The results suggested that daratumumab is most effective at a dose of 16 mg/kg. At this dose, the overall response rate was 36%.

Most adverse events in this study were grade 1 or 2, although serious events did occur.

The SIRIUS study enrolled 124 MM patients who had received 3 or more prior lines of therapy. They received daratumumab at different doses and on different schedules, but 106 of the patients received the drug at 16 mg/kg.

Twenty-nine percent of the 106 patients responded to treatment, and the median duration of response was 7 months. Thirty percent of patients experienced serious adverse events. ![]()

Group identifies malaria resistance locus

outside of Nairobi, Kenya

Photo by Gabrielle Tenenbaum

Researchers say they have identified genetic variants that protect African children from developing severe malaria, in some cases nearly halving a child’s chance of developing the disease.

The variants are at a locus located next to a cluster of genes that are responsible for creating the receptors the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses to infect red blood cells.

The researchers described their findings in a letter to Nature.

“The risk of developing severe malaria turns out to be strongly linked to the process by which the malaria parasite gains entry to the human red blood cell,” said Dr Kevin Marsh, of the Kemri-Wellcome Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya.

“This study strengthens the argument for focusing on the malaria side of the parasite-human interaction in our search for new vaccine candidates.”

For this study, Dr Marsh and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 different African countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, The Gambia, and Tanzania.

They compared the DNA of 5633 children with severe malaria and the DNA of 5919 children without severe malaria. The researchers then replicated their key findings in a further 14,000 children.

The locus the team identified is near a cluster of genes that code for glycophorins, which are involved in P falciparum’s invasion of red blood cells.

The researchers also found an allele that was common among children in Kenya. Having this allele reduced the risk of severe malaria by about 40% in Kenyan children, with a slightly smaller effect across all the other populations studied.

The team said this difference between populations could be due to the genetic features of the local malaria parasite in East Africa.

Balancing selection

The newly identified malaria resistance locus lies within a region of the genome where humans and chimpanzees have been known to share particular combinations of haplotypes.

This indicates that some of the variation seen in contemporary humans has been present for millions of years. The finding also suggests that this region of the genome is the subject of balancing selection.

Balancing selection happens when a particular genetic variant evolves because it confers health benefits, but it is carried by only a proportion of the population because it also has damaging consequences.

“These findings indicate that balancing selection and resistance to malaria are deeply intertwined themes in our ancient evolutionary history,” said Dr Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This new resistance locus is particularly interesting because it lies so close to genes that are gatekeepers for the malaria parasite’s invasion machinery. We now need to drill down at this locus to characterize these complex patterns of genetic variation more precisely and to understand the molecular mechanisms by which they act.” ![]()

outside of Nairobi, Kenya

Photo by Gabrielle Tenenbaum

Researchers say they have identified genetic variants that protect African children from developing severe malaria, in some cases nearly halving a child’s chance of developing the disease.

The variants are at a locus located next to a cluster of genes that are responsible for creating the receptors the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses to infect red blood cells.

The researchers described their findings in a letter to Nature.

“The risk of developing severe malaria turns out to be strongly linked to the process by which the malaria parasite gains entry to the human red blood cell,” said Dr Kevin Marsh, of the Kemri-Wellcome Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya.

“This study strengthens the argument for focusing on the malaria side of the parasite-human interaction in our search for new vaccine candidates.”

For this study, Dr Marsh and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 different African countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, The Gambia, and Tanzania.

They compared the DNA of 5633 children with severe malaria and the DNA of 5919 children without severe malaria. The researchers then replicated their key findings in a further 14,000 children.

The locus the team identified is near a cluster of genes that code for glycophorins, which are involved in P falciparum’s invasion of red blood cells.

The researchers also found an allele that was common among children in Kenya. Having this allele reduced the risk of severe malaria by about 40% in Kenyan children, with a slightly smaller effect across all the other populations studied.

The team said this difference between populations could be due to the genetic features of the local malaria parasite in East Africa.

Balancing selection

The newly identified malaria resistance locus lies within a region of the genome where humans and chimpanzees have been known to share particular combinations of haplotypes.

This indicates that some of the variation seen in contemporary humans has been present for millions of years. The finding also suggests that this region of the genome is the subject of balancing selection.

Balancing selection happens when a particular genetic variant evolves because it confers health benefits, but it is carried by only a proportion of the population because it also has damaging consequences.

“These findings indicate that balancing selection and resistance to malaria are deeply intertwined themes in our ancient evolutionary history,” said Dr Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This new resistance locus is particularly interesting because it lies so close to genes that are gatekeepers for the malaria parasite’s invasion machinery. We now need to drill down at this locus to characterize these complex patterns of genetic variation more precisely and to understand the molecular mechanisms by which they act.” ![]()

outside of Nairobi, Kenya

Photo by Gabrielle Tenenbaum

Researchers say they have identified genetic variants that protect African children from developing severe malaria, in some cases nearly halving a child’s chance of developing the disease.

The variants are at a locus located next to a cluster of genes that are responsible for creating the receptors the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses to infect red blood cells.

The researchers described their findings in a letter to Nature.

“The risk of developing severe malaria turns out to be strongly linked to the process by which the malaria parasite gains entry to the human red blood cell,” said Dr Kevin Marsh, of the Kemri-Wellcome Research Programme in Kilifi, Kenya.

“This study strengthens the argument for focusing on the malaria side of the parasite-human interaction in our search for new vaccine candidates.”

For this study, Dr Marsh and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 different African countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, The Gambia, and Tanzania.

They compared the DNA of 5633 children with severe malaria and the DNA of 5919 children without severe malaria. The researchers then replicated their key findings in a further 14,000 children.

The locus the team identified is near a cluster of genes that code for glycophorins, which are involved in P falciparum’s invasion of red blood cells.

The researchers also found an allele that was common among children in Kenya. Having this allele reduced the risk of severe malaria by about 40% in Kenyan children, with a slightly smaller effect across all the other populations studied.

The team said this difference between populations could be due to the genetic features of the local malaria parasite in East Africa.

Balancing selection

The newly identified malaria resistance locus lies within a region of the genome where humans and chimpanzees have been known to share particular combinations of haplotypes.

This indicates that some of the variation seen in contemporary humans has been present for millions of years. The finding also suggests that this region of the genome is the subject of balancing selection.

Balancing selection happens when a particular genetic variant evolves because it confers health benefits, but it is carried by only a proportion of the population because it also has damaging consequences.

“These findings indicate that balancing selection and resistance to malaria are deeply intertwined themes in our ancient evolutionary history,” said Dr Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK.

“This new resistance locus is particularly interesting because it lies so close to genes that are gatekeepers for the malaria parasite’s invasion machinery. We now need to drill down at this locus to characterize these complex patterns of genetic variation more precisely and to understand the molecular mechanisms by which they act.” ![]()

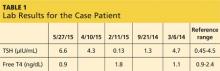

Investigating Unstable Thyroid Function

A 43-year-old man presents for his thyroid checkup. He has known hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. He is taking levothyroxine (LT4) 250 μg (two 125-μg tablets once per day). Review of his prior lab results and notes (see Table 1) reveals frequent dose changes (about every three to six months) and a high dosage of LT4, considering his weight (185 lb).

Patients with little or no residual thyroid function require replacement doses of LT4 at approximately 1.6 μg/kg/d, based on lean body weight.1 Since the case patient weighs 84 kg, the expected LT4 dosage would be around 125 to 150 μg/d.

This patient requires a significantly higher dose than expected, and his thyroid levels are fluctuating. These facts should trigger further investigation.

Important historical questions I consider when patients have frequent or significant fluctuations in TSH include

• Are you consistent in taking your medication?

• How do you take your thyroid medication?

• Are you taking any iron supplements, vitamins with iron, or contraceptive pills containing iron?

• Has there been any change in your other medication regimen(s) or medical condition(s)?

• Did you change pharmacies, or did the shape or color of your pill change?

• Have you experienced significant weight changes?

• Do you have any gastrointestinal complaints (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea/bloating)?

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

It is well known but still puzzling to hear that, overall, patients’ medication adherence is merely 50%.2 It is very important that you verify whether your patient is taking his/her medication consistently. Rather than asking “Are you taking your medications?” (to which they are more likely to answer “yes”), I ask “How many pills do you miss in a given week or month?”

For those who have a hard time remembering to take their medication on a regular basis, I recommend setting up a routine: Keep the medication at their bedside and take it first thing upon awakening, or place it beside the toothpaste so they see it every time they brush their teeth in the morning. Another option is of course to set up an alarm as a reminder.

Continue for rules for taking hypothyroid >>

RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

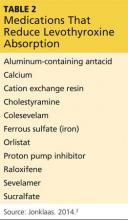

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

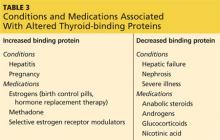

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>

CHANGES IN MANUFACTURER/BRAND

There are currently multiple brands and generic manufacturers supplying hypothyroid medications and reports that absorption rates and bioavailability vary among them.2 Switching products can result in changes in thyroid status and in TSH levels.

Once a patient has reached euthyroid status, it is imperative to stay on the same dose from the same manufacturer. This may be challenging, as it can be affected by the patient’s insurance carrier, policy changes, or even a change in the pharmacy’s medication supplier. Although patients are supposed to be informed by the pharmacy when the manufacturer is being changed, you may want to educate them to check the shape, color, and dose of their pills and also verify that the manufacturer listed on the bottle is consistent each time they refill their hypothyroid medications. This is especially important for those who require a very narrow TSH target, such as young children, thyroid cancer patients, pregnant women, and frail patients.3

WEIGHT CHANGES

As mentioned, thyroid medications are weight-based, and big changes in weight can lead to changes in thyroid function studies. It is the lean body mass, rather than total body weight, that will affect the thyroid requirement.3 A quick review of the patient’s weight history needs to be done when thyroid function test results have changed.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCES

Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the small intestine, and gastric acidity levels have an impact on absorption. Any acute or chronic conditions that affect these areas can alter medication absorption quite significantly. Commonly encountered diseases and conditions are H pylori–related gastritis, atrophic gastritis, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance. Treating these diseases and conditions can improve medication absorption.

I went through the list with the patient, but there was no applicable scenario. I adjusted his medication but went ahead and tested for tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA to rule out celiac disease; results came back mildly positive. The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist, who performed a small intestine biopsy for definitive diagnosis. This revealed “severe” celiac disease. A strict gluten-free diet was started, and the patient’s LT4 dose was adjusted, with regular monitoring, down to 150 μg/d.