User login

Assessing Discharge Readiness

Widespread evidence suggests that the period around hospitalization remains a vulnerable time for patients. Nearly 20% of patients experience adverse events, including medication errors and hospital readmissions, within 3 weeks of discharge.[1] Multiple factors contribute to adverse events, including the overwhelming volume of information patients receive on their last day in the hospital and fragmented interdisciplinary communication, both among hospital‐based providers and with community providers.[2, 3, 4] A growing body of literature suggests that to ensure patient understanding and a safe transition, discharge planning should start at time of admission. Yet, in the context of high patient volumes and competing priorities, clinicians often postpone discharge planning until they perceive a patient's discharge is imminent. Discharge bundles, designed to improve the safety of hospital discharge, such as those developed by Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions) or Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge), are not designed to help providers determine when a patient might be approaching discharge.[5, 6] Early identification of a patient's probable discharge date can provide vital information to inpatient and outpatient teams as they establish comprehensive discharge plans. Accurate discharge‐date predictions allow for effective discharge planning, serving to reduce length of stay (LOS) and consequently improving patient satisfaction and patient safety.[7] However, in the complex world of internal medicine, can clinicians accurately predict the timing of discharge?

A study by Sullivan and colleagues[8] in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine explores a physician's ability to predict hospital discharge. Trainees and attending physicians on general internal medicine wards were asked to predict whether each patient under their care would be discharged on the next day, on the same day, or neither. Discharge predictions were recorded at 3 time points: mornings (79 am), midday (122 pm), or afternoons (57 pm). For predictions of next‐day discharges, the sensitivity (SN) and positive predictive value (PPV) were highest in the afternoon (SN 67%, PPV 69%), whereas for same‐day discharges, accuracy was highest midday (SN 88%, PPV 79%). The authors note that physicians' ability to correctly predict discharges continually improved as time to actual discharge fell.

This study is novel; to our knowledge, no other studies have evaluated the accuracy with which physicians can predict the actual day of discharge. Although this study is particular to a trainee setting and more specific to a single academic medical center, the results are thought provoking. Why are attendings and trainees unable to predict next‐day discharges more accurately? Can we do better? The majority of medical patients are not electively admitted and therefore may have complex and unpredictable courses compared to elective or surgical admissions. Subspecialty consultants may be guiding clinical care and potentially even determining readiness for discharge. Furthermore, the additional responsibilities of teaching and supervising trainees in academic medical centers may further delay discussions and decisions about patient discharges. Another plausible hypothesis, however, is that determination of barriers to discharge and discharge readiness is a clinical skill that is underappreciated and not taught or modeled sufficiently.

If we are to do better at predicting and planning for discharge, we need to build prompts for discharge readiness assessment into our daily work and education of trainees. Although interdisciplinary rounds are typically held in the morning, Wertheimer and colleagues show that additional afternoon interdisciplinary rounds can help identify patients who might be discharged before noon the next day.[9] In their study, identifying such patients in advance improved the overall early discharge rate, moved the average discharge time to earlier in the day, and decreased the observed‐to‐expected LOS, all without any adverse effects on readmissions. We also need more communication between members of the physician care team, especially with subspecialists helping manage care. The authors describe moderate agreement with next‐day and substantial agreement with same‐day discharges between trainees and attendings. Although the authors do not reveal whether trainees or attendings were more accurate, the discrepancy with next‐day discharges is notable. The disagreement suggests a lack of communication between team members about discharge barriers that can hinder planning efforts. Assessing a patient's readiness for and needs upon discharge, and anticipating a patient's disease trajectory, are important clinical skills. Trainees may lack clinical judgment and experience to accurately predict a patient's clinical evolution. As hospitalists, we can role model how to continuously assess patients' discharge needs throughout hospitalization by discussing discharge barriers during daily rounds. As part of transitions of care curricula, in addition to learning about best practices in discharge planning (eg, medication reconciliation, teach back, follow‐up appointments, effective discharge summaries), trainees should be encouraged to conduct structured, daily assessment of discharge readiness and anticipated day of discharge.

Starting the discharge planning process earlier in an admission has the potential to create more thoughtful, efficient, and ultimately safer discharges for our patients. By building discharge readiness assessments into the daily workflow and education curricula, we can prompt trainees and attendings to communicate with interdisciplinary team members and address potential challenges that patients may face in managing their health after discharge. Adequately preparing patients for safe discharges has readmission implications. With Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reducing payments to facilities with high rates of readmissions, reducing avoidable readmissions is a priority for all institutions.[10]

We can accomplish safe and early discharges. However, we must get better at accurately assessing our patients' readiness for discharge if we are to take the first step.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Widespread evidence suggests that the period around hospitalization remains a vulnerable time for patients. Nearly 20% of patients experience adverse events, including medication errors and hospital readmissions, within 3 weeks of discharge.[1] Multiple factors contribute to adverse events, including the overwhelming volume of information patients receive on their last day in the hospital and fragmented interdisciplinary communication, both among hospital‐based providers and with community providers.[2, 3, 4] A growing body of literature suggests that to ensure patient understanding and a safe transition, discharge planning should start at time of admission. Yet, in the context of high patient volumes and competing priorities, clinicians often postpone discharge planning until they perceive a patient's discharge is imminent. Discharge bundles, designed to improve the safety of hospital discharge, such as those developed by Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions) or Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge), are not designed to help providers determine when a patient might be approaching discharge.[5, 6] Early identification of a patient's probable discharge date can provide vital information to inpatient and outpatient teams as they establish comprehensive discharge plans. Accurate discharge‐date predictions allow for effective discharge planning, serving to reduce length of stay (LOS) and consequently improving patient satisfaction and patient safety.[7] However, in the complex world of internal medicine, can clinicians accurately predict the timing of discharge?

A study by Sullivan and colleagues[8] in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine explores a physician's ability to predict hospital discharge. Trainees and attending physicians on general internal medicine wards were asked to predict whether each patient under their care would be discharged on the next day, on the same day, or neither. Discharge predictions were recorded at 3 time points: mornings (79 am), midday (122 pm), or afternoons (57 pm). For predictions of next‐day discharges, the sensitivity (SN) and positive predictive value (PPV) were highest in the afternoon (SN 67%, PPV 69%), whereas for same‐day discharges, accuracy was highest midday (SN 88%, PPV 79%). The authors note that physicians' ability to correctly predict discharges continually improved as time to actual discharge fell.

This study is novel; to our knowledge, no other studies have evaluated the accuracy with which physicians can predict the actual day of discharge. Although this study is particular to a trainee setting and more specific to a single academic medical center, the results are thought provoking. Why are attendings and trainees unable to predict next‐day discharges more accurately? Can we do better? The majority of medical patients are not electively admitted and therefore may have complex and unpredictable courses compared to elective or surgical admissions. Subspecialty consultants may be guiding clinical care and potentially even determining readiness for discharge. Furthermore, the additional responsibilities of teaching and supervising trainees in academic medical centers may further delay discussions and decisions about patient discharges. Another plausible hypothesis, however, is that determination of barriers to discharge and discharge readiness is a clinical skill that is underappreciated and not taught or modeled sufficiently.

If we are to do better at predicting and planning for discharge, we need to build prompts for discharge readiness assessment into our daily work and education of trainees. Although interdisciplinary rounds are typically held in the morning, Wertheimer and colleagues show that additional afternoon interdisciplinary rounds can help identify patients who might be discharged before noon the next day.[9] In their study, identifying such patients in advance improved the overall early discharge rate, moved the average discharge time to earlier in the day, and decreased the observed‐to‐expected LOS, all without any adverse effects on readmissions. We also need more communication between members of the physician care team, especially with subspecialists helping manage care. The authors describe moderate agreement with next‐day and substantial agreement with same‐day discharges between trainees and attendings. Although the authors do not reveal whether trainees or attendings were more accurate, the discrepancy with next‐day discharges is notable. The disagreement suggests a lack of communication between team members about discharge barriers that can hinder planning efforts. Assessing a patient's readiness for and needs upon discharge, and anticipating a patient's disease trajectory, are important clinical skills. Trainees may lack clinical judgment and experience to accurately predict a patient's clinical evolution. As hospitalists, we can role model how to continuously assess patients' discharge needs throughout hospitalization by discussing discharge barriers during daily rounds. As part of transitions of care curricula, in addition to learning about best practices in discharge planning (eg, medication reconciliation, teach back, follow‐up appointments, effective discharge summaries), trainees should be encouraged to conduct structured, daily assessment of discharge readiness and anticipated day of discharge.

Starting the discharge planning process earlier in an admission has the potential to create more thoughtful, efficient, and ultimately safer discharges for our patients. By building discharge readiness assessments into the daily workflow and education curricula, we can prompt trainees and attendings to communicate with interdisciplinary team members and address potential challenges that patients may face in managing their health after discharge. Adequately preparing patients for safe discharges has readmission implications. With Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reducing payments to facilities with high rates of readmissions, reducing avoidable readmissions is a priority for all institutions.[10]

We can accomplish safe and early discharges. However, we must get better at accurately assessing our patients' readiness for discharge if we are to take the first step.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Widespread evidence suggests that the period around hospitalization remains a vulnerable time for patients. Nearly 20% of patients experience adverse events, including medication errors and hospital readmissions, within 3 weeks of discharge.[1] Multiple factors contribute to adverse events, including the overwhelming volume of information patients receive on their last day in the hospital and fragmented interdisciplinary communication, both among hospital‐based providers and with community providers.[2, 3, 4] A growing body of literature suggests that to ensure patient understanding and a safe transition, discharge planning should start at time of admission. Yet, in the context of high patient volumes and competing priorities, clinicians often postpone discharge planning until they perceive a patient's discharge is imminent. Discharge bundles, designed to improve the safety of hospital discharge, such as those developed by Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions) or Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge), are not designed to help providers determine when a patient might be approaching discharge.[5, 6] Early identification of a patient's probable discharge date can provide vital information to inpatient and outpatient teams as they establish comprehensive discharge plans. Accurate discharge‐date predictions allow for effective discharge planning, serving to reduce length of stay (LOS) and consequently improving patient satisfaction and patient safety.[7] However, in the complex world of internal medicine, can clinicians accurately predict the timing of discharge?

A study by Sullivan and colleagues[8] in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine explores a physician's ability to predict hospital discharge. Trainees and attending physicians on general internal medicine wards were asked to predict whether each patient under their care would be discharged on the next day, on the same day, or neither. Discharge predictions were recorded at 3 time points: mornings (79 am), midday (122 pm), or afternoons (57 pm). For predictions of next‐day discharges, the sensitivity (SN) and positive predictive value (PPV) were highest in the afternoon (SN 67%, PPV 69%), whereas for same‐day discharges, accuracy was highest midday (SN 88%, PPV 79%). The authors note that physicians' ability to correctly predict discharges continually improved as time to actual discharge fell.

This study is novel; to our knowledge, no other studies have evaluated the accuracy with which physicians can predict the actual day of discharge. Although this study is particular to a trainee setting and more specific to a single academic medical center, the results are thought provoking. Why are attendings and trainees unable to predict next‐day discharges more accurately? Can we do better? The majority of medical patients are not electively admitted and therefore may have complex and unpredictable courses compared to elective or surgical admissions. Subspecialty consultants may be guiding clinical care and potentially even determining readiness for discharge. Furthermore, the additional responsibilities of teaching and supervising trainees in academic medical centers may further delay discussions and decisions about patient discharges. Another plausible hypothesis, however, is that determination of barriers to discharge and discharge readiness is a clinical skill that is underappreciated and not taught or modeled sufficiently.

If we are to do better at predicting and planning for discharge, we need to build prompts for discharge readiness assessment into our daily work and education of trainees. Although interdisciplinary rounds are typically held in the morning, Wertheimer and colleagues show that additional afternoon interdisciplinary rounds can help identify patients who might be discharged before noon the next day.[9] In their study, identifying such patients in advance improved the overall early discharge rate, moved the average discharge time to earlier in the day, and decreased the observed‐to‐expected LOS, all without any adverse effects on readmissions. We also need more communication between members of the physician care team, especially with subspecialists helping manage care. The authors describe moderate agreement with next‐day and substantial agreement with same‐day discharges between trainees and attendings. Although the authors do not reveal whether trainees or attendings were more accurate, the discrepancy with next‐day discharges is notable. The disagreement suggests a lack of communication between team members about discharge barriers that can hinder planning efforts. Assessing a patient's readiness for and needs upon discharge, and anticipating a patient's disease trajectory, are important clinical skills. Trainees may lack clinical judgment and experience to accurately predict a patient's clinical evolution. As hospitalists, we can role model how to continuously assess patients' discharge needs throughout hospitalization by discussing discharge barriers during daily rounds. As part of transitions of care curricula, in addition to learning about best practices in discharge planning (eg, medication reconciliation, teach back, follow‐up appointments, effective discharge summaries), trainees should be encouraged to conduct structured, daily assessment of discharge readiness and anticipated day of discharge.

Starting the discharge planning process earlier in an admission has the potential to create more thoughtful, efficient, and ultimately safer discharges for our patients. By building discharge readiness assessments into the daily workflow and education curricula, we can prompt trainees and attendings to communicate with interdisciplinary team members and address potential challenges that patients may face in managing their health after discharge. Adequately preparing patients for safe discharges has readmission implications. With Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reducing payments to facilities with high rates of readmissions, reducing avoidable readmissions is a priority for all institutions.[10]

We can accomplish safe and early discharges. However, we must get better at accurately assessing our patients' readiness for discharge if we are to take the first step.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Pharmacist Impact on Transitional Care

Hospital readmissions have a significant impact on the healthcare system. Medicare data suggest a 19% all‐cause 30‐day readmission rate, of which 47% may be preventable.[1, 2] The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services continue to expand their criteria of disease states that will be penalized for readmissions, now reducing hospital reimbursement rates up to 3%. Pharmacists, by optimizing patient utilization of medications, can play a valuable role in contributing to preventing readmissions.[3]

Lack of acceptable transitional care is a serious problem that is consistently identified in the literature.[4] Transitional care involves 3 domains of transfer: information, education, and destination. A breakdown in any of these components can negatively impact patients and their caregivers.

Prior studies consistently demonstrated a high likelihood of adverse drug events (ADEs) and patients' lack of knowledge regarding medications postdischarge, both of which can lead to readmission. Forster and colleagues found that 19% to 23% of patients experienced an ADE within 5 weeks of discharge from an inpatient visit, 66% to 72% of which were drug related, and approximately one‐third were deemed preventable.[5, 6] One survey found that less than 60% of patients knew the indication for a new medication prescribed at discharge, whereas only 12% reported knowledge of an anticipated ADE.[7]

Pharmacists can play a large role in the information and education aspect of transitional care. Previous studies demonstrate that pharmacist involvement in the discharge process can reduce the incidence of ADEs and have a positive impact on patient satisfaction. There are conflicting data regarding the effect of comprehensive medication education and follow‐up calls by pharmacy team members on ADEs and medication errors (MEs).[3, 8, 9] Although overall pharmacist participation has shown positive patient‐related outcomes, the impact of pharmacists' involvement on readmissions has not been consistently demonstrated.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Our study evaluated the impact of the pharmacy team in the transitions‐of‐care settings in a unique combination utilizing the pharmacist during medication reconciliation, discharge, and with 3 follow‐up phone call interactions postdischarge. Our study was designed to evaluate the impact of intensive pharmacist involvement during the acute care admission as well as for a 30‐day time period postdischarge on both ADEs and readmissions.

METHODS

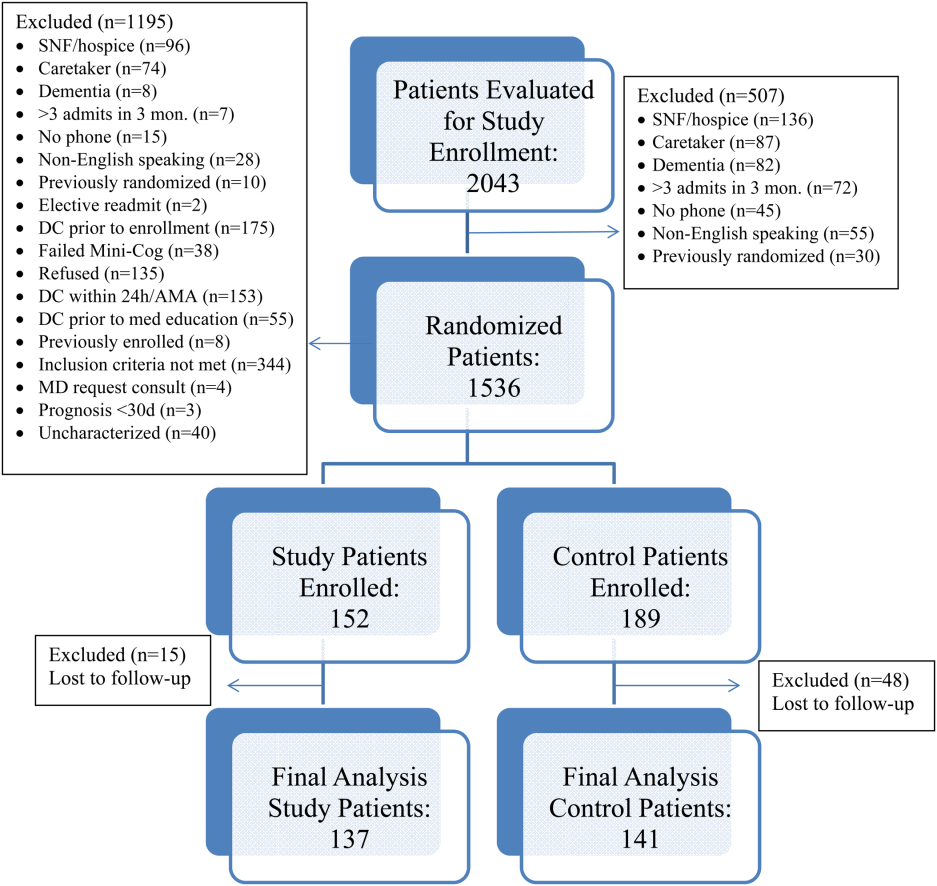

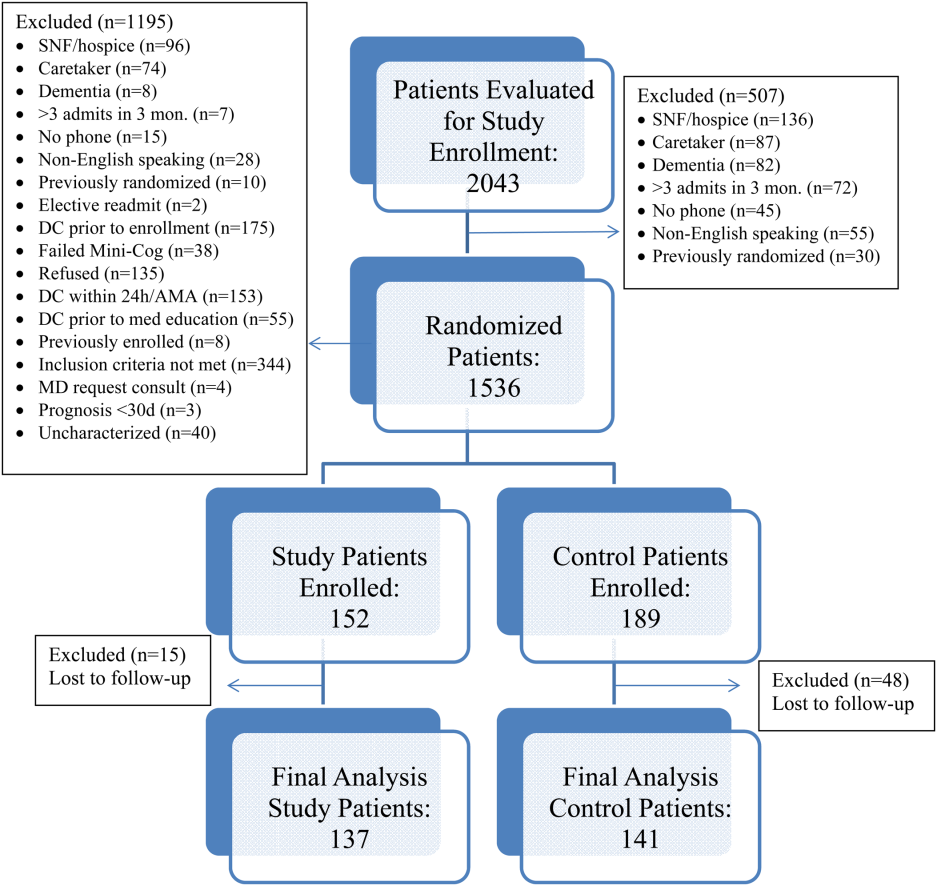

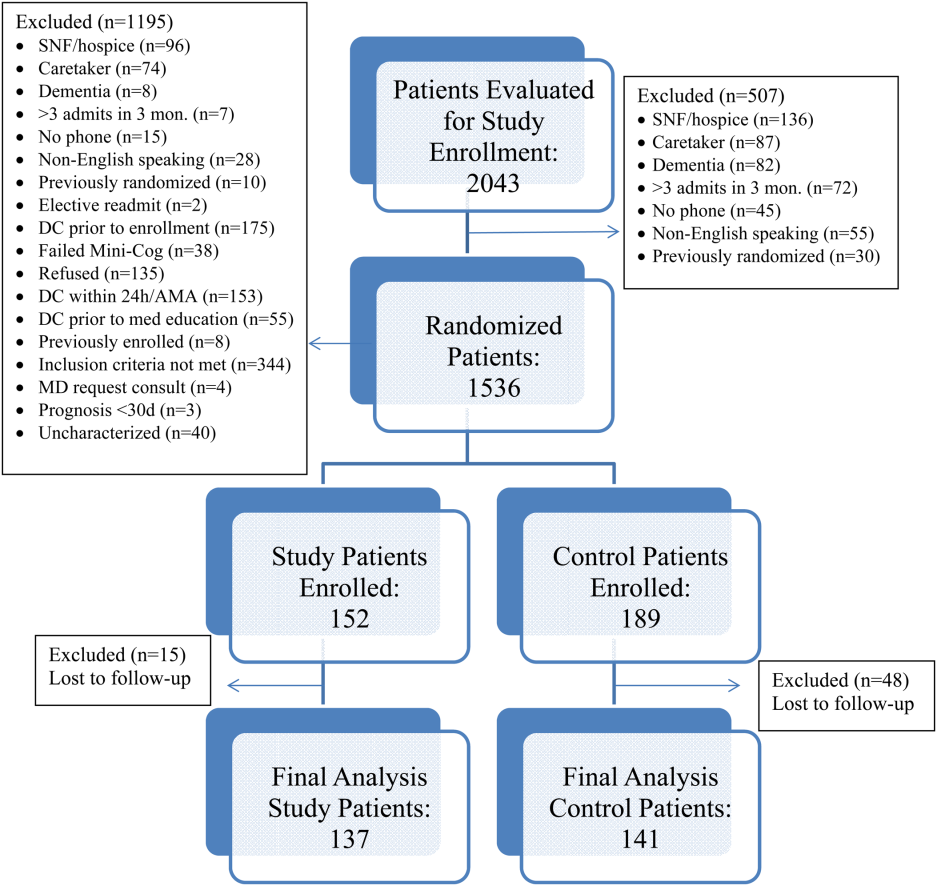

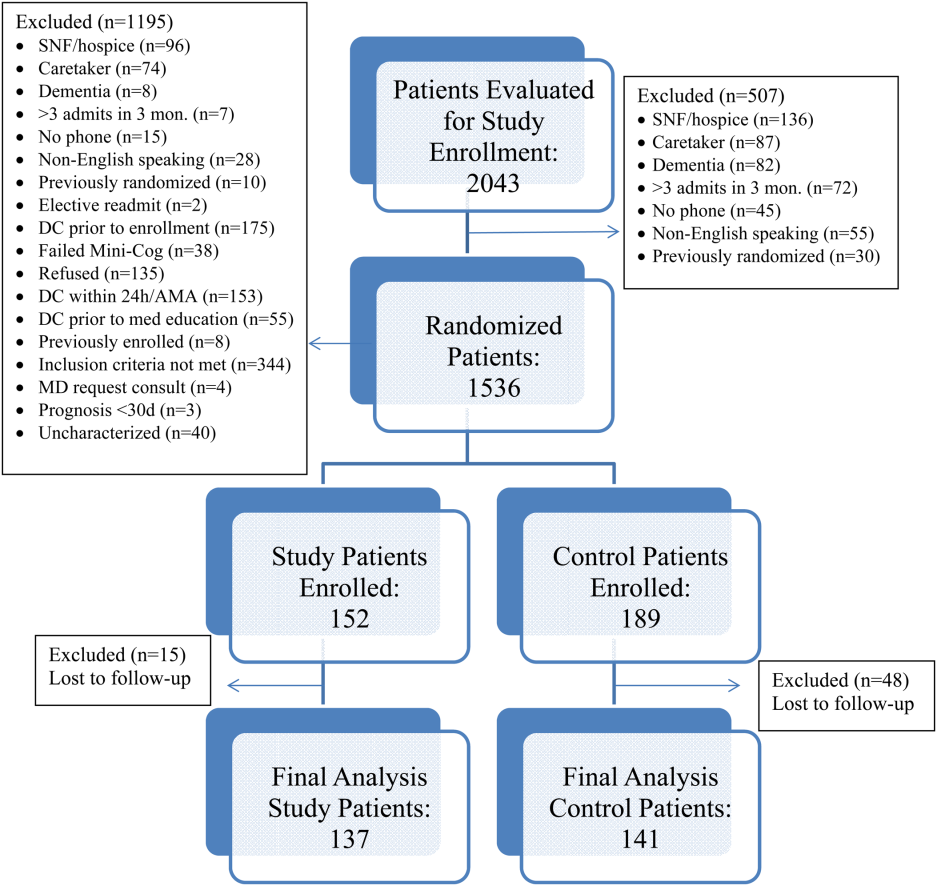

All patients were admitted to hospitalist‐based internal medicine units at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, an 894‐bed academic medical center located in Chicago, Illinois. Patients were randomized by study investigators using a random number generator to either the usual care or intervention arms and then evaluated each day for eligibility to participate in the study. Patients remained blinded throughout the study. Patients met inclusion criteria if they were discharged to home and either discharged on greater than 3 scheduled prescription medications or discharged with at least 1 high‐risk medication. High‐risk medications were classified as anticoagulants, antiplatelets (eg, aspirin and clopidogrel), hypoglycemic agents (eg, insulin), immunosuppressants, or anti‐infectives. Patients also needed to participate in a minimum of 1 postdischarge phone call or experience an emergency department (ED) visit or readmission within 30 days of discharge to meet inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included: impaired cognition based on Mini‐Cog screening assessment scale, unable or unwilling to provide informed consent, lack of a personal phone number, nonEnglish speaking, subsequent elective readmission within 30 days of initial visit, more than 3 previous hospital admissions in the past 2 months, palliative care or home/skilled nursing hospice, anticipated length of survival less than 3 months, discharged within 24 hours of admission, discharged against medical advice, or discharged before medication education was conducted (Figure 1). Patients who met inclusion criteria provided informed consent, received a Mini‐Cog screening assessment, and were given the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine revised (REALM‐R) assessment to evaluate health literacy. The REALM‐R is a word recognition test designed to identify patients at risk for poor health literacy skills. Patients with REALM‐R scores of 6 or less are considered to have low health literacy.[15] Patients were randomized to receive either the usual care or pharmacist‐directed medication evaluation and management as described in Table 1. Patients included in the study were contacted by phone postdischarge, with 3 attempts on consecutive days. Patients who were readmitted as an inpatient or had an ED visit were not contacted for the study after that point.

| Admission Medication Reconciliation | Hospitalist (Confirmation by Pharmacist Reviewing the History and Physical Note in Electronic Medical Record) | Performed by Pharmacy Team Member Face to Face |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Discharge medication reconciliation | Hospitalist | Pharmacy team member |

| Discharge medication education | Hospitalist and/or nurse | Pharmacy team member |

| Individualized medication plan | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 3 | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 14 | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 30 | Yes | Yes |

| Postdischarge call assessment topic(s) | ADEs/MEs, ED visits, inpatient readmissions | ADEs/MEs, ED visits, inpatient readmissions clarify pharmacy/discharge plan, resolve medication‐related issues, identify/overcome adherence barriers |

Patients enrolled in the control group received the usual standard of care by a clinical pharmacist. This included a medication reconciliation completed from the admitting physician's patient history and physical and medication counseling provided by the physician or nursing staff at discharge. Patients were not interviewed face‐to‐face on admission and did not receive discharge counseling by a pharmacy team member. Patients were assessed daily by the pharmacist for evaluation of the pharmacotherapy plans and presence of MEs or safety‐related concerns. The control group received 1 postdischarge phone call from a pharmacist at day 30 to assess for study endpoints of ADEs, MEs, ED visit, and readmission only. The endpoints of ADEs and MEs were determined by professional judgment by the clinical pharmacist based on an algorithm similar to National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, although a specific tool was not utilized.

The study group received face‐to‐face medication reconciliation on admission by a pharmacist or a pharmacy student. Prior to discharge, a personalized medication plan was created by the pharmacist and discussed with the physician. Medication discrepancies were addressed prior to the discharge instructions being given and discussed with the patient. Medication counseling was performed at discharge by the pharmacist or pharmacy student. Patients received 3 phone calls at 3, 14, and 30 days postdischarge. The presence of ADEs and MEs were evaluated during each phone call. The patients were asked to confirm their medication regimens including drug, indication, dose, route, and frequency. They were also asked questions regarding possible side effects, new symptoms, and any changes to their current therapy. The calls focused on clarifying the pharmacy discharge plan, resolving any unanswered questions or medication‐related issues, identifying and overcoming any barriers to adherence, and assistance with providing patients access to medications by contacting pharmacies and physicians to resolve and troubleshoot further prescription claims and clarifications. Pharmacists performed all postdischarge phone calls. Pharmacy students were able to provide face‐to‐face medication reconciliation upon admission and discharge counseling under the supervision of the pharmacist for the intervention arm.

The patient Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) responses to the medication domain question, Did you clearly understand the purpose for taking each of your medications at the time of discharge? were collected for the 2 designated hospitalist units for both the control and study groups. HCAHPS scores were collected at the 6 months point prior to the study initiation and throughout the 6‐month study period for the control and intervention groups. A physician and 2 pharmacists, who were blinded to the study randomization and results, assessed all Northwestern Memorial Hospital readmissions to determine if the readmissions were medication‐related or not.

This study obtained institutional review board approval from Northwestern University.

Data Collected

Data collected from all patients included demographics (age, sex), payer, reason for admission, number of medications at time of discharge, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, number of high‐risk medications prescribed at time of discharge, length of stay, REALM‐R score, ADEs, inpatient readmission or ED visit, and the reason for readmission or ED visit. Only the first occurrence was counted for patients with both an ED visit and an inpatient readmission. It was estimated that a sample size of 150 patients in each group would provide 80% power to demonstrate a 20% improvement in ADE rates in the study group. Data were analyzed utilizing Fischer exact, 2, and Student t tests, and multivariate logistic regression as appropriate. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Over the course of 7 months, 341 patients were enrolled in the study, 189 in the control arm and 152 in the study arm. Forty‐eight patients in the control group and 15 patients in the study group were lost to follow‐up. The final analysis included 278 patients, 141 in the control group and 137 in the study group. Patients were eligible for study inclusion if they received at least 1 phone call, which resulted in more patients being lost to follow‐up in the control arm due to fewer total phone call attempts. Demographic and disposition data for the control and study groups are shown in Table 2. Baseline characteristics between the 2 groups were similar with the exception of total medications at time of discharge. The control group had more total medications at discharge compared to the study group (7.2 vs 6.4, P=0.04). The number of high‐risk medications and the number of scheduled medications were similar between both groups. During medication reconciliation, 380 discrepancies (46.2%) were found in the study group compared to 205 (19.9%) in the control group (P<0.0001). The higher number of identified discrepancies in the study group was expected due to the fact that the pharmacist did not complete a face‐to‐face medication history in the control patients. The average length of stay, REALM‐R scores, and reason for admissions were similar between the 2 groups (Table 2).

| Study, N=137 | Control, N=141 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Sex, male | 52 (37.95%) | 59 (41.8%) | 0.54 |

| Average age, y | 55.4 | 55.8 | 0.87 |

| Average length of stay, d | 5.4 (range, 1104) | 4.6 (range, 028) | 0.67 |

| Average REALM‐R score (range, 08) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 0.67 |

| Average total no. of medications | 6.4 | 7.2 | 0.04 |

| Average no. of scheduled medications | 5.7 | 6.2 | 0.15 |

| Average no. of high‐risk category medications | 2.2 | 2.3 | 0.64 |

| Reason for admission | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 5 (3.4%) | 15 (8.3%) | 0.035 |

| Pneumonia | 11 (7.5%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.48 |

| Respiratory | 11 (7.5%) | 9 (5%) | 0.65 |

| Infectious disease | 39 (26.5%) | 53 (29.3%) | 0.13 |

| Gastrointestinal | 25 (17%) | 28 (15.5%) | 0.13 |

| Endocrine | 20 (13.6%) | 34 (18.8%) | 0.76 |

| Genitourinary | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.05 |

| Hematological | 19 (12.9%) | 20 (11%) | 1 |

| Injury | 10 (6.8%) | 14 (7.7%) | 1 |

| Neurological | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.52 |

| Heart failure | 4 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.24 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.58 |

| Mental/substance abuse | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

A total of 55 patients (39%) in the control arm were readmitted to an inpatient hospital or had an ED visit within 30‐days postdischarge compared to 34 patients (24.8%) in the study group (P=0.001) (Table 3). Of the patients readmitted to the ED, 21 were enrolled in the control arm (14.8%) compared to only 6 patients in the study arm (4.4%) (P=0.005). Reviewers concluded that 24% of the control group readmissions were medication‐related versus 23% of the study group (P=1.0). In total, 78 out of 89 readmissions were to Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Medication‐related causes to outside institutions were not evaluated. The causes for all readmissions were not evaluated.

| Study Group, n=137 | Control Group, n=141 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Composite inpatient readmission and ED visit | 34 (24.8%) | 55 (38.7%) | 0.001 |

| ED visits | 6 (4.4%) | 21 (14.8%) | 0.005 |

| Inpatient readmissions | 28 (20.4%) | 34 (23.9%) | 0.43 |

| Medication‐related readmissions | 8 (23.5%) | 13 (23.6%) | 1.0 |

| ADEs/MEs reported at 30‐day phone call | 11/84 patients | 18/86 patients | 0.22 |

| Days to readmission/ED visit | 7.9 (SD 12.5) | 13.2 (SD 9.61) | 0.03 |

| Preintervention: HCAHPS scores pertaining to knowledge of indication of medication question preintervention | 47% | ||

| Postintervention: HCAHPS scores pertaining to knowledge of indication of medication question postintervention | 56% | ||

A sensitivity analysis was undertaken to understand the impact of the lost to follow‐up rate in both the control and study groups. Undertaking an assumption that all 15 patients lost to follow‐up in the study group were readmitted and that 15 of 48 patients lost to follow‐up in the control group were readmitted, the intervention continued to show a significant benefit in reduction of composite ED and inpatient readmissions (35.7% study group vs 49.6% control group, P=0.022)

Multivariate logistic regression analysis that controlled for Charlson Comorbidity Index score, length of stay, total number of medications on discharge, and payer type showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.55 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.32‐0.94) in the intervention cohort compared to controls for the combined endpoint of readmission and ED visit within 30‐days postdischarge. The adjusted odds ratio for 30‐day readmission alone was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.49‐1.61).

Eighteen of the 86 control patients who received a 30‐day postdischarge phone call experienced an ADE or ME compared to 11 of the 83 study patients (P=0.22). Patient satisfaction scores of both designated units as represented by the HCAHPS score in the medication knowledge domain increased from the prestudy period. Patients selected agree or strongly agree only 47% of the time at the 6‐month prestudy point compared to 56% of the time during the 6‐month study period.

DISCUSSION

Although previous studies show conflicting results regarding the impact of pharmacist interventions on readmissions, our study demonstrated a decrease in the composite measure of inpatient readmissions and ED visits. Its success stresses the need for a comprehensive approach that contains continuity of care by healthcare providers to reconcile and manage medications throughout the hospital stay, extending up to a full month postdischarge with multiple phone calls. This included (1) face‐to‐face medication reconciliation on admission, (2) development of a personalized medication plan discussed with the patient's physician, (3) addressing any medication discrepancies to the discharge instructions being given to the patient, (4) medication counseling performed at discharge, and (5) 3 postdischarge phone calls at 3, 14, and 30 days.

A study conducted in 2001 analyzed the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) and found that living alone, having limited education, and lack of self‐management skills have significant associations with early readmission.[16] Approximately 80 million Americans have limited health literacy and are associated with poor health outcomes and healthcare utilization as seen in a review completed by Berkman and colleagues.[17] Because no difference was found between both groups, it would suggest health literacy did not influence or bias the study group. Additionally, no statistically different medication issues, such as total number of medications or rates of ADEs and MEs, were identified in the patients of this study. This may be explained by the small, final population size at the 30‐day period or that the impact of the pharmacist intervention did not reach the threshold that this study was powered to detect. Also, a lack of statistical significance may be due to the subjective nature of ADEs/MEs and the prevention of ADEs/MEs throughout all patients' hospitalizations from the clinical pharmacist's involvement in care, which was not collected. Although a combined endpoint collecting readmission to either the ED or rehospitalization was lower in the intervention cohort, the isolated rehospitalization endpoint was not significantly different between the 2 groups. ED utilization was markedly decreased, but we may have lacked the power to show a statistically significant decrease in rehospitalization. These results mirror those of the Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge) intervention.[17]

HCAHPS surveys are sent to only a small percent of randomly selected patients who are discharged from the hospital. Thus, respondents may or may not have been included in the study, indicating a possible greater impact of the intervention on individual patients than collected. Importantly, the described interventions appeared to improve patients' perception of understanding the purpose of their medications. We found that HCAHPS scores across the 2 units improved, though the intervention only impacted 16.8% of all patients discharged from these units due to the nature of the survey distribution.

The pharmacists' abilities to educate all eligible patients prior to discharge from 7:30 am to 4:00 pm each day of the week was a limitation of this study, as some patients were discharged outside of the duty hours. This may have allowed for a differential exclusion and could have led to selection bias. Another limitation is that a large number of patients were lost to follow‐up in the control group, likely because the first postdischarge contact with patients was not until the day 30 phone calls. The extensive exclusion criteria caused many patients not to be enrolled. Though the intervention arm received postdischarge phone calls at days 3 and 14, only postdischarge call‐backs at day 30 of the intervention arm were compared to the control arm, which could have led to bias in the 30‐day analysis of the intervention arm, as patients may have not reported previous issues that were resolved in earlier phone calls. Medication‐related readmissions were not statistically different between the groups, which could suggest that the difference in readmissions were not solely due to the intervention, and a decrease in healthcare utilization may be due to chance. The subjective nature of how ADEs and MEs were collected also serves as a limitation, as they were only screened for presence or absence and not classified by severity or category. This study was at a single‐center academic institution, which may limit the ability to apply the results to other institutions. Last, outcome assessments relied on participant report, including ADE and ME occurrence and presentation at outside hospitals. Future study evaluation conducted as a multicenter design while continuing to strengthen the continuity of the healthcare provider and patient relationship at each intervention would be ideal. Also, having an objective measure of ADEs and MEs with severity categorization would be beneficial.

Compared to previous literature, our study design was unique in the number of phone calls made to patients postdischarge and its prospective, randomized design. In the previously mentioned study by Walker et al., phone calls were made only at days 3 and 30.[13] Although the majority of readmissions occurred within the first 14 days of discharge, additional visits to the ED and readmissions may have been avoided by contacting patients twice within the critical 14‐day period. Another distinction of this study design was the expansion of a rather limited and peripheral pharmacist role in transitions of care to a much more integrated participation. We believe the relationship developed between patients and their pharmacy care team provided coordination and the continuity of communication regarding their care. Additionally, our study was unique through the use of pharmacy extenders via fourth‐year pharmacy students who were completing their advanced pharmacy practice rotations. Pharmacy extenders can also be certified and trained pharmacy technicians, which many hospitals utilize to perform medication reconciliations at a lower cost than pharmacists. As hospitals face increased demands to shrink budgets due to decreasing reimbursements, healthcare systems will be forced to find creative new ways to use existing resources.

In conclusion, transition of care is a high‐risk situation for many patients. A comprehensive approach by healthcare providers, including pharmacists and pharmacy extenders, may have a positive impact in reducing or preventing ADEs/MEs, inpatient admissions, and ED visits. Although our study focused directly on the impact of a pharmacy care team on transitions‐of‐care, we cannot conclude this applies strictly to pharmacists. Across the nation, the role of various disciplines of healthcare providers in admission, hospitalization, discharge, and postdischarge is not standardized and varies significantly by institution. Importantly, no mechanism currently exists to directly reimburse for such efforts, but demonstration of cost effectiveness through reduced posthospital utilization may justify this investment for accountable care organizations.[18]

- , , , , , . Medicare readmission rates show meaningful decline in 2012. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(2):E1‐E11.

- , , , et al. Factors contributing to all‐cause 30‐day readmissions: a structured case series across 18 hospitals. Med Care. 2012:50(7):599–605.

- , , , et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;66:565–571.

- , , . Optimizing transitions of care to reduce rehospitalizations. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(5):1–9.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients following discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–167.

- , . Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:317–323.

- . What do discharged patients know about their medications? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:276–282.

- , , , . The impact of telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Dis Mon. 2002;48:239–248.

- , , , et al. Effect of a pharmacist intervention on clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:1–10.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , , , . The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counselling to elderly patients prior to discharge. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:657–664.

- , , , . Postdischarge pharmacist medication reconciliation: impact on readmission rates and financial savings. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(1):78–84.

- , , , et al. Impact of pharmacist‐facilitated hospital discharge program. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2003–2010.

- , , , et al. Does pharmacist‐led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65(3):303–316.

- . The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):878–883.

- , , , , , . Postdischarge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission among community‐dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):495–504.

- , , , , . Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107.

- , , , et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in Medicare. Health Affairs. 2009;28(2):219–231.

Hospital readmissions have a significant impact on the healthcare system. Medicare data suggest a 19% all‐cause 30‐day readmission rate, of which 47% may be preventable.[1, 2] The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services continue to expand their criteria of disease states that will be penalized for readmissions, now reducing hospital reimbursement rates up to 3%. Pharmacists, by optimizing patient utilization of medications, can play a valuable role in contributing to preventing readmissions.[3]

Lack of acceptable transitional care is a serious problem that is consistently identified in the literature.[4] Transitional care involves 3 domains of transfer: information, education, and destination. A breakdown in any of these components can negatively impact patients and their caregivers.

Prior studies consistently demonstrated a high likelihood of adverse drug events (ADEs) and patients' lack of knowledge regarding medications postdischarge, both of which can lead to readmission. Forster and colleagues found that 19% to 23% of patients experienced an ADE within 5 weeks of discharge from an inpatient visit, 66% to 72% of which were drug related, and approximately one‐third were deemed preventable.[5, 6] One survey found that less than 60% of patients knew the indication for a new medication prescribed at discharge, whereas only 12% reported knowledge of an anticipated ADE.[7]

Pharmacists can play a large role in the information and education aspect of transitional care. Previous studies demonstrate that pharmacist involvement in the discharge process can reduce the incidence of ADEs and have a positive impact on patient satisfaction. There are conflicting data regarding the effect of comprehensive medication education and follow‐up calls by pharmacy team members on ADEs and medication errors (MEs).[3, 8, 9] Although overall pharmacist participation has shown positive patient‐related outcomes, the impact of pharmacists' involvement on readmissions has not been consistently demonstrated.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Our study evaluated the impact of the pharmacy team in the transitions‐of‐care settings in a unique combination utilizing the pharmacist during medication reconciliation, discharge, and with 3 follow‐up phone call interactions postdischarge. Our study was designed to evaluate the impact of intensive pharmacist involvement during the acute care admission as well as for a 30‐day time period postdischarge on both ADEs and readmissions.

METHODS

All patients were admitted to hospitalist‐based internal medicine units at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, an 894‐bed academic medical center located in Chicago, Illinois. Patients were randomized by study investigators using a random number generator to either the usual care or intervention arms and then evaluated each day for eligibility to participate in the study. Patients remained blinded throughout the study. Patients met inclusion criteria if they were discharged to home and either discharged on greater than 3 scheduled prescription medications or discharged with at least 1 high‐risk medication. High‐risk medications were classified as anticoagulants, antiplatelets (eg, aspirin and clopidogrel), hypoglycemic agents (eg, insulin), immunosuppressants, or anti‐infectives. Patients also needed to participate in a minimum of 1 postdischarge phone call or experience an emergency department (ED) visit or readmission within 30 days of discharge to meet inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included: impaired cognition based on Mini‐Cog screening assessment scale, unable or unwilling to provide informed consent, lack of a personal phone number, nonEnglish speaking, subsequent elective readmission within 30 days of initial visit, more than 3 previous hospital admissions in the past 2 months, palliative care or home/skilled nursing hospice, anticipated length of survival less than 3 months, discharged within 24 hours of admission, discharged against medical advice, or discharged before medication education was conducted (Figure 1). Patients who met inclusion criteria provided informed consent, received a Mini‐Cog screening assessment, and were given the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine revised (REALM‐R) assessment to evaluate health literacy. The REALM‐R is a word recognition test designed to identify patients at risk for poor health literacy skills. Patients with REALM‐R scores of 6 or less are considered to have low health literacy.[15] Patients were randomized to receive either the usual care or pharmacist‐directed medication evaluation and management as described in Table 1. Patients included in the study were contacted by phone postdischarge, with 3 attempts on consecutive days. Patients who were readmitted as an inpatient or had an ED visit were not contacted for the study after that point.

| Admission Medication Reconciliation | Hospitalist (Confirmation by Pharmacist Reviewing the History and Physical Note in Electronic Medical Record) | Performed by Pharmacy Team Member Face to Face |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Discharge medication reconciliation | Hospitalist | Pharmacy team member |

| Discharge medication education | Hospitalist and/or nurse | Pharmacy team member |

| Individualized medication plan | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 3 | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 14 | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 30 | Yes | Yes |

| Postdischarge call assessment topic(s) | ADEs/MEs, ED visits, inpatient readmissions | ADEs/MEs, ED visits, inpatient readmissions clarify pharmacy/discharge plan, resolve medication‐related issues, identify/overcome adherence barriers |

Patients enrolled in the control group received the usual standard of care by a clinical pharmacist. This included a medication reconciliation completed from the admitting physician's patient history and physical and medication counseling provided by the physician or nursing staff at discharge. Patients were not interviewed face‐to‐face on admission and did not receive discharge counseling by a pharmacy team member. Patients were assessed daily by the pharmacist for evaluation of the pharmacotherapy plans and presence of MEs or safety‐related concerns. The control group received 1 postdischarge phone call from a pharmacist at day 30 to assess for study endpoints of ADEs, MEs, ED visit, and readmission only. The endpoints of ADEs and MEs were determined by professional judgment by the clinical pharmacist based on an algorithm similar to National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, although a specific tool was not utilized.

The study group received face‐to‐face medication reconciliation on admission by a pharmacist or a pharmacy student. Prior to discharge, a personalized medication plan was created by the pharmacist and discussed with the physician. Medication discrepancies were addressed prior to the discharge instructions being given and discussed with the patient. Medication counseling was performed at discharge by the pharmacist or pharmacy student. Patients received 3 phone calls at 3, 14, and 30 days postdischarge. The presence of ADEs and MEs were evaluated during each phone call. The patients were asked to confirm their medication regimens including drug, indication, dose, route, and frequency. They were also asked questions regarding possible side effects, new symptoms, and any changes to their current therapy. The calls focused on clarifying the pharmacy discharge plan, resolving any unanswered questions or medication‐related issues, identifying and overcoming any barriers to adherence, and assistance with providing patients access to medications by contacting pharmacies and physicians to resolve and troubleshoot further prescription claims and clarifications. Pharmacists performed all postdischarge phone calls. Pharmacy students were able to provide face‐to‐face medication reconciliation upon admission and discharge counseling under the supervision of the pharmacist for the intervention arm.

The patient Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) responses to the medication domain question, Did you clearly understand the purpose for taking each of your medications at the time of discharge? were collected for the 2 designated hospitalist units for both the control and study groups. HCAHPS scores were collected at the 6 months point prior to the study initiation and throughout the 6‐month study period for the control and intervention groups. A physician and 2 pharmacists, who were blinded to the study randomization and results, assessed all Northwestern Memorial Hospital readmissions to determine if the readmissions were medication‐related or not.

This study obtained institutional review board approval from Northwestern University.

Data Collected

Data collected from all patients included demographics (age, sex), payer, reason for admission, number of medications at time of discharge, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, number of high‐risk medications prescribed at time of discharge, length of stay, REALM‐R score, ADEs, inpatient readmission or ED visit, and the reason for readmission or ED visit. Only the first occurrence was counted for patients with both an ED visit and an inpatient readmission. It was estimated that a sample size of 150 patients in each group would provide 80% power to demonstrate a 20% improvement in ADE rates in the study group. Data were analyzed utilizing Fischer exact, 2, and Student t tests, and multivariate logistic regression as appropriate. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Over the course of 7 months, 341 patients were enrolled in the study, 189 in the control arm and 152 in the study arm. Forty‐eight patients in the control group and 15 patients in the study group were lost to follow‐up. The final analysis included 278 patients, 141 in the control group and 137 in the study group. Patients were eligible for study inclusion if they received at least 1 phone call, which resulted in more patients being lost to follow‐up in the control arm due to fewer total phone call attempts. Demographic and disposition data for the control and study groups are shown in Table 2. Baseline characteristics between the 2 groups were similar with the exception of total medications at time of discharge. The control group had more total medications at discharge compared to the study group (7.2 vs 6.4, P=0.04). The number of high‐risk medications and the number of scheduled medications were similar between both groups. During medication reconciliation, 380 discrepancies (46.2%) were found in the study group compared to 205 (19.9%) in the control group (P<0.0001). The higher number of identified discrepancies in the study group was expected due to the fact that the pharmacist did not complete a face‐to‐face medication history in the control patients. The average length of stay, REALM‐R scores, and reason for admissions were similar between the 2 groups (Table 2).

| Study, N=137 | Control, N=141 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Sex, male | 52 (37.95%) | 59 (41.8%) | 0.54 |

| Average age, y | 55.4 | 55.8 | 0.87 |

| Average length of stay, d | 5.4 (range, 1104) | 4.6 (range, 028) | 0.67 |

| Average REALM‐R score (range, 08) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 0.67 |

| Average total no. of medications | 6.4 | 7.2 | 0.04 |

| Average no. of scheduled medications | 5.7 | 6.2 | 0.15 |

| Average no. of high‐risk category medications | 2.2 | 2.3 | 0.64 |

| Reason for admission | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 5 (3.4%) | 15 (8.3%) | 0.035 |

| Pneumonia | 11 (7.5%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.48 |

| Respiratory | 11 (7.5%) | 9 (5%) | 0.65 |

| Infectious disease | 39 (26.5%) | 53 (29.3%) | 0.13 |

| Gastrointestinal | 25 (17%) | 28 (15.5%) | 0.13 |

| Endocrine | 20 (13.6%) | 34 (18.8%) | 0.76 |

| Genitourinary | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.05 |

| Hematological | 19 (12.9%) | 20 (11%) | 1 |

| Injury | 10 (6.8%) | 14 (7.7%) | 1 |

| Neurological | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.52 |

| Heart failure | 4 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.24 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.58 |

| Mental/substance abuse | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

A total of 55 patients (39%) in the control arm were readmitted to an inpatient hospital or had an ED visit within 30‐days postdischarge compared to 34 patients (24.8%) in the study group (P=0.001) (Table 3). Of the patients readmitted to the ED, 21 were enrolled in the control arm (14.8%) compared to only 6 patients in the study arm (4.4%) (P=0.005). Reviewers concluded that 24% of the control group readmissions were medication‐related versus 23% of the study group (P=1.0). In total, 78 out of 89 readmissions were to Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Medication‐related causes to outside institutions were not evaluated. The causes for all readmissions were not evaluated.

| Study Group, n=137 | Control Group, n=141 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Composite inpatient readmission and ED visit | 34 (24.8%) | 55 (38.7%) | 0.001 |

| ED visits | 6 (4.4%) | 21 (14.8%) | 0.005 |

| Inpatient readmissions | 28 (20.4%) | 34 (23.9%) | 0.43 |

| Medication‐related readmissions | 8 (23.5%) | 13 (23.6%) | 1.0 |

| ADEs/MEs reported at 30‐day phone call | 11/84 patients | 18/86 patients | 0.22 |

| Days to readmission/ED visit | 7.9 (SD 12.5) | 13.2 (SD 9.61) | 0.03 |

| Preintervention: HCAHPS scores pertaining to knowledge of indication of medication question preintervention | 47% | ||

| Postintervention: HCAHPS scores pertaining to knowledge of indication of medication question postintervention | 56% | ||

A sensitivity analysis was undertaken to understand the impact of the lost to follow‐up rate in both the control and study groups. Undertaking an assumption that all 15 patients lost to follow‐up in the study group were readmitted and that 15 of 48 patients lost to follow‐up in the control group were readmitted, the intervention continued to show a significant benefit in reduction of composite ED and inpatient readmissions (35.7% study group vs 49.6% control group, P=0.022)

Multivariate logistic regression analysis that controlled for Charlson Comorbidity Index score, length of stay, total number of medications on discharge, and payer type showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.55 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.32‐0.94) in the intervention cohort compared to controls for the combined endpoint of readmission and ED visit within 30‐days postdischarge. The adjusted odds ratio for 30‐day readmission alone was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.49‐1.61).

Eighteen of the 86 control patients who received a 30‐day postdischarge phone call experienced an ADE or ME compared to 11 of the 83 study patients (P=0.22). Patient satisfaction scores of both designated units as represented by the HCAHPS score in the medication knowledge domain increased from the prestudy period. Patients selected agree or strongly agree only 47% of the time at the 6‐month prestudy point compared to 56% of the time during the 6‐month study period.

DISCUSSION

Although previous studies show conflicting results regarding the impact of pharmacist interventions on readmissions, our study demonstrated a decrease in the composite measure of inpatient readmissions and ED visits. Its success stresses the need for a comprehensive approach that contains continuity of care by healthcare providers to reconcile and manage medications throughout the hospital stay, extending up to a full month postdischarge with multiple phone calls. This included (1) face‐to‐face medication reconciliation on admission, (2) development of a personalized medication plan discussed with the patient's physician, (3) addressing any medication discrepancies to the discharge instructions being given to the patient, (4) medication counseling performed at discharge, and (5) 3 postdischarge phone calls at 3, 14, and 30 days.

A study conducted in 2001 analyzed the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) and found that living alone, having limited education, and lack of self‐management skills have significant associations with early readmission.[16] Approximately 80 million Americans have limited health literacy and are associated with poor health outcomes and healthcare utilization as seen in a review completed by Berkman and colleagues.[17] Because no difference was found between both groups, it would suggest health literacy did not influence or bias the study group. Additionally, no statistically different medication issues, such as total number of medications or rates of ADEs and MEs, were identified in the patients of this study. This may be explained by the small, final population size at the 30‐day period or that the impact of the pharmacist intervention did not reach the threshold that this study was powered to detect. Also, a lack of statistical significance may be due to the subjective nature of ADEs/MEs and the prevention of ADEs/MEs throughout all patients' hospitalizations from the clinical pharmacist's involvement in care, which was not collected. Although a combined endpoint collecting readmission to either the ED or rehospitalization was lower in the intervention cohort, the isolated rehospitalization endpoint was not significantly different between the 2 groups. ED utilization was markedly decreased, but we may have lacked the power to show a statistically significant decrease in rehospitalization. These results mirror those of the Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge) intervention.[17]

HCAHPS surveys are sent to only a small percent of randomly selected patients who are discharged from the hospital. Thus, respondents may or may not have been included in the study, indicating a possible greater impact of the intervention on individual patients than collected. Importantly, the described interventions appeared to improve patients' perception of understanding the purpose of their medications. We found that HCAHPS scores across the 2 units improved, though the intervention only impacted 16.8% of all patients discharged from these units due to the nature of the survey distribution.

The pharmacists' abilities to educate all eligible patients prior to discharge from 7:30 am to 4:00 pm each day of the week was a limitation of this study, as some patients were discharged outside of the duty hours. This may have allowed for a differential exclusion and could have led to selection bias. Another limitation is that a large number of patients were lost to follow‐up in the control group, likely because the first postdischarge contact with patients was not until the day 30 phone calls. The extensive exclusion criteria caused many patients not to be enrolled. Though the intervention arm received postdischarge phone calls at days 3 and 14, only postdischarge call‐backs at day 30 of the intervention arm were compared to the control arm, which could have led to bias in the 30‐day analysis of the intervention arm, as patients may have not reported previous issues that were resolved in earlier phone calls. Medication‐related readmissions were not statistically different between the groups, which could suggest that the difference in readmissions were not solely due to the intervention, and a decrease in healthcare utilization may be due to chance. The subjective nature of how ADEs and MEs were collected also serves as a limitation, as they were only screened for presence or absence and not classified by severity or category. This study was at a single‐center academic institution, which may limit the ability to apply the results to other institutions. Last, outcome assessments relied on participant report, including ADE and ME occurrence and presentation at outside hospitals. Future study evaluation conducted as a multicenter design while continuing to strengthen the continuity of the healthcare provider and patient relationship at each intervention would be ideal. Also, having an objective measure of ADEs and MEs with severity categorization would be beneficial.

Compared to previous literature, our study design was unique in the number of phone calls made to patients postdischarge and its prospective, randomized design. In the previously mentioned study by Walker et al., phone calls were made only at days 3 and 30.[13] Although the majority of readmissions occurred within the first 14 days of discharge, additional visits to the ED and readmissions may have been avoided by contacting patients twice within the critical 14‐day period. Another distinction of this study design was the expansion of a rather limited and peripheral pharmacist role in transitions of care to a much more integrated participation. We believe the relationship developed between patients and their pharmacy care team provided coordination and the continuity of communication regarding their care. Additionally, our study was unique through the use of pharmacy extenders via fourth‐year pharmacy students who were completing their advanced pharmacy practice rotations. Pharmacy extenders can also be certified and trained pharmacy technicians, which many hospitals utilize to perform medication reconciliations at a lower cost than pharmacists. As hospitals face increased demands to shrink budgets due to decreasing reimbursements, healthcare systems will be forced to find creative new ways to use existing resources.

In conclusion, transition of care is a high‐risk situation for many patients. A comprehensive approach by healthcare providers, including pharmacists and pharmacy extenders, may have a positive impact in reducing or preventing ADEs/MEs, inpatient admissions, and ED visits. Although our study focused directly on the impact of a pharmacy care team on transitions‐of‐care, we cannot conclude this applies strictly to pharmacists. Across the nation, the role of various disciplines of healthcare providers in admission, hospitalization, discharge, and postdischarge is not standardized and varies significantly by institution. Importantly, no mechanism currently exists to directly reimburse for such efforts, but demonstration of cost effectiveness through reduced posthospital utilization may justify this investment for accountable care organizations.[18]

Hospital readmissions have a significant impact on the healthcare system. Medicare data suggest a 19% all‐cause 30‐day readmission rate, of which 47% may be preventable.[1, 2] The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services continue to expand their criteria of disease states that will be penalized for readmissions, now reducing hospital reimbursement rates up to 3%. Pharmacists, by optimizing patient utilization of medications, can play a valuable role in contributing to preventing readmissions.[3]

Lack of acceptable transitional care is a serious problem that is consistently identified in the literature.[4] Transitional care involves 3 domains of transfer: information, education, and destination. A breakdown in any of these components can negatively impact patients and their caregivers.

Prior studies consistently demonstrated a high likelihood of adverse drug events (ADEs) and patients' lack of knowledge regarding medications postdischarge, both of which can lead to readmission. Forster and colleagues found that 19% to 23% of patients experienced an ADE within 5 weeks of discharge from an inpatient visit, 66% to 72% of which were drug related, and approximately one‐third were deemed preventable.[5, 6] One survey found that less than 60% of patients knew the indication for a new medication prescribed at discharge, whereas only 12% reported knowledge of an anticipated ADE.[7]

Pharmacists can play a large role in the information and education aspect of transitional care. Previous studies demonstrate that pharmacist involvement in the discharge process can reduce the incidence of ADEs and have a positive impact on patient satisfaction. There are conflicting data regarding the effect of comprehensive medication education and follow‐up calls by pharmacy team members on ADEs and medication errors (MEs).[3, 8, 9] Although overall pharmacist participation has shown positive patient‐related outcomes, the impact of pharmacists' involvement on readmissions has not been consistently demonstrated.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Our study evaluated the impact of the pharmacy team in the transitions‐of‐care settings in a unique combination utilizing the pharmacist during medication reconciliation, discharge, and with 3 follow‐up phone call interactions postdischarge. Our study was designed to evaluate the impact of intensive pharmacist involvement during the acute care admission as well as for a 30‐day time period postdischarge on both ADEs and readmissions.

METHODS

All patients were admitted to hospitalist‐based internal medicine units at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, an 894‐bed academic medical center located in Chicago, Illinois. Patients were randomized by study investigators using a random number generator to either the usual care or intervention arms and then evaluated each day for eligibility to participate in the study. Patients remained blinded throughout the study. Patients met inclusion criteria if they were discharged to home and either discharged on greater than 3 scheduled prescription medications or discharged with at least 1 high‐risk medication. High‐risk medications were classified as anticoagulants, antiplatelets (eg, aspirin and clopidogrel), hypoglycemic agents (eg, insulin), immunosuppressants, or anti‐infectives. Patients also needed to participate in a minimum of 1 postdischarge phone call or experience an emergency department (ED) visit or readmission within 30 days of discharge to meet inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included: impaired cognition based on Mini‐Cog screening assessment scale, unable or unwilling to provide informed consent, lack of a personal phone number, nonEnglish speaking, subsequent elective readmission within 30 days of initial visit, more than 3 previous hospital admissions in the past 2 months, palliative care or home/skilled nursing hospice, anticipated length of survival less than 3 months, discharged within 24 hours of admission, discharged against medical advice, or discharged before medication education was conducted (Figure 1). Patients who met inclusion criteria provided informed consent, received a Mini‐Cog screening assessment, and were given the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine revised (REALM‐R) assessment to evaluate health literacy. The REALM‐R is a word recognition test designed to identify patients at risk for poor health literacy skills. Patients with REALM‐R scores of 6 or less are considered to have low health literacy.[15] Patients were randomized to receive either the usual care or pharmacist‐directed medication evaluation and management as described in Table 1. Patients included in the study were contacted by phone postdischarge, with 3 attempts on consecutive days. Patients who were readmitted as an inpatient or had an ED visit were not contacted for the study after that point.

| Admission Medication Reconciliation | Hospitalist (Confirmation by Pharmacist Reviewing the History and Physical Note in Electronic Medical Record) | Performed by Pharmacy Team Member Face to Face |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Discharge medication reconciliation | Hospitalist | Pharmacy team member |

| Discharge medication education | Hospitalist and/or nurse | Pharmacy team member |

| Individualized medication plan | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 3 | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 14 | No | Yes |

| Postdischarge callback day 30 | Yes | Yes |

| Postdischarge call assessment topic(s) | ADEs/MEs, ED visits, inpatient readmissions | ADEs/MEs, ED visits, inpatient readmissions clarify pharmacy/discharge plan, resolve medication‐related issues, identify/overcome adherence barriers |

Patients enrolled in the control group received the usual standard of care by a clinical pharmacist. This included a medication reconciliation completed from the admitting physician's patient history and physical and medication counseling provided by the physician or nursing staff at discharge. Patients were not interviewed face‐to‐face on admission and did not receive discharge counseling by a pharmacy team member. Patients were assessed daily by the pharmacist for evaluation of the pharmacotherapy plans and presence of MEs or safety‐related concerns. The control group received 1 postdischarge phone call from a pharmacist at day 30 to assess for study endpoints of ADEs, MEs, ED visit, and readmission only. The endpoints of ADEs and MEs were determined by professional judgment by the clinical pharmacist based on an algorithm similar to National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, although a specific tool was not utilized.

The study group received face‐to‐face medication reconciliation on admission by a pharmacist or a pharmacy student. Prior to discharge, a personalized medication plan was created by the pharmacist and discussed with the physician. Medication discrepancies were addressed prior to the discharge instructions being given and discussed with the patient. Medication counseling was performed at discharge by the pharmacist or pharmacy student. Patients received 3 phone calls at 3, 14, and 30 days postdischarge. The presence of ADEs and MEs were evaluated during each phone call. The patients were asked to confirm their medication regimens including drug, indication, dose, route, and frequency. They were also asked questions regarding possible side effects, new symptoms, and any changes to their current therapy. The calls focused on clarifying the pharmacy discharge plan, resolving any unanswered questions or medication‐related issues, identifying and overcoming any barriers to adherence, and assistance with providing patients access to medications by contacting pharmacies and physicians to resolve and troubleshoot further prescription claims and clarifications. Pharmacists performed all postdischarge phone calls. Pharmacy students were able to provide face‐to‐face medication reconciliation upon admission and discharge counseling under the supervision of the pharmacist for the intervention arm.

The patient Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) responses to the medication domain question, Did you clearly understand the purpose for taking each of your medications at the time of discharge? were collected for the 2 designated hospitalist units for both the control and study groups. HCAHPS scores were collected at the 6 months point prior to the study initiation and throughout the 6‐month study period for the control and intervention groups. A physician and 2 pharmacists, who were blinded to the study randomization and results, assessed all Northwestern Memorial Hospital readmissions to determine if the readmissions were medication‐related or not.

This study obtained institutional review board approval from Northwestern University.

Data Collected

Data collected from all patients included demographics (age, sex), payer, reason for admission, number of medications at time of discharge, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, number of high‐risk medications prescribed at time of discharge, length of stay, REALM‐R score, ADEs, inpatient readmission or ED visit, and the reason for readmission or ED visit. Only the first occurrence was counted for patients with both an ED visit and an inpatient readmission. It was estimated that a sample size of 150 patients in each group would provide 80% power to demonstrate a 20% improvement in ADE rates in the study group. Data were analyzed utilizing Fischer exact, 2, and Student t tests, and multivariate logistic regression as appropriate. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Over the course of 7 months, 341 patients were enrolled in the study, 189 in the control arm and 152 in the study arm. Forty‐eight patients in the control group and 15 patients in the study group were lost to follow‐up. The final analysis included 278 patients, 141 in the control group and 137 in the study group. Patients were eligible for study inclusion if they received at least 1 phone call, which resulted in more patients being lost to follow‐up in the control arm due to fewer total phone call attempts. Demographic and disposition data for the control and study groups are shown in Table 2. Baseline characteristics between the 2 groups were similar with the exception of total medications at time of discharge. The control group had more total medications at discharge compared to the study group (7.2 vs 6.4, P=0.04). The number of high‐risk medications and the number of scheduled medications were similar between both groups. During medication reconciliation, 380 discrepancies (46.2%) were found in the study group compared to 205 (19.9%) in the control group (P<0.0001). The higher number of identified discrepancies in the study group was expected due to the fact that the pharmacist did not complete a face‐to‐face medication history in the control patients. The average length of stay, REALM‐R scores, and reason for admissions were similar between the 2 groups (Table 2).

| Study, N=137 | Control, N=141 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Sex, male | 52 (37.95%) | 59 (41.8%) | 0.54 |

| Average age, y | 55.4 | 55.8 | 0.87 |

| Average length of stay, d | 5.4 (range, 1104) | 4.6 (range, 028) | 0.67 |

| Average REALM‐R score (range, 08) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 0.67 |

| Average total no. of medications | 6.4 | 7.2 | 0.04 |

| Average no. of scheduled medications | 5.7 | 6.2 | 0.15 |

| Average no. of high‐risk category medications | 2.2 | 2.3 | 0.64 |

| Reason for admission | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 5 (3.4%) | 15 (8.3%) | 0.035 |

| Pneumonia | 11 (7.5%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.48 |

| Respiratory | 11 (7.5%) | 9 (5%) | 0.65 |

| Infectious disease | 39 (26.5%) | 53 (29.3%) | 0.13 |

| Gastrointestinal | 25 (17%) | 28 (15.5%) | 0.13 |

| Endocrine | 20 (13.6%) | 34 (18.8%) | 0.76 |

| Genitourinary | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.05 |

| Hematological | 19 (12.9%) | 20 (11%) | 1 |

| Injury | 10 (6.8%) | 14 (7.7%) | 1 |

| Neurological | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.52 |

| Heart failure | 4 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.24 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.58 |

| Mental/substance abuse | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

A total of 55 patients (39%) in the control arm were readmitted to an inpatient hospital or had an ED visit within 30‐days postdischarge compared to 34 patients (24.8%) in the study group (P=0.001) (Table 3). Of the patients readmitted to the ED, 21 were enrolled in the control arm (14.8%) compared to only 6 patients in the study arm (4.4%) (P=0.005). Reviewers concluded that 24% of the control group readmissions were medication‐related versus 23% of the study group (P=1.0). In total, 78 out of 89 readmissions were to Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Medication‐related causes to outside institutions were not evaluated. The causes for all readmissions were not evaluated.

| Study Group, n=137 | Control Group, n=141 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||