User login

Case Studies in Toxicology: One Last Kick—Transverse Myelitis After an Overdose of Heroin via Insufflation

Case

A 17-year-old adolescent girl with a history of depression and opioid dependence, for which she was taking buprenorphine until 2 weeks earlier, presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) after her father found her lying on the couch unresponsive and with shallow respirations. Naloxone was administered by EMS and her mental status improved.

At presentation, the patient admitted to insufflation of an unknown amount of heroin and ingestion of 2 mg of alprazolam earlier in the day. She denied any past or current use of intravenous (IV) drugs. During monitoring, she began to complain of numbness in her legs and an inability to urinate. Examination revealed paralysis and decreased sensation of her bilateral lower extremities to the midthigh, with decreased rectal tone. Because of the patient’s history of drug use and temporal association with the heroin overdose, both neurosurgery and toxicology services were consulted.

What can cause lower extremity paralysis in a drug user?

The differential diagnosis for the patient at this point included toxin-induced myelopathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hypokalemic periodic paralysis, spinal compression, epidural abscess, cerebrovascular accident, spinal lesion, and spinal artery dissection or infarction.

Although Guillain-Barré syndrome presents with ascending paralysis, there is usually an antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. While epidural abscess with spinal compression is associated with IV drug use and can present similarly, the patient in this case denied IV use. In the absence of any risk factors, cerebrovascular accident and spinal artery dissection were also unlikely.

Case Continuation

A bladder catheter was placed due to the patient’s inability to urinate, and approximately 1 L of urine output was retrieved. Immediate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated increased T2 signal intensity and expansion of the distal thoracic cord and conus without mass lesion, consistent with transverse myelitis (TM).

What is transverse myelitis and why does it occur?

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory demyelinating disorder that focally affects the spinal cord, resulting in a specific pattern of motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction.1 Signs and symptoms include paresthesia, paralysis of the extremities, and loss of bladder and bowel control. The level of the spinal cord affected determines the clinical effects. Demyelination typically occurs at the thoracic segment, producing findings in the legs, as well as bladder and bowel dysfunction.

The exact cause of TM is unknown, but the inflammation may result from a viral complication or an abnormal immune response. Infectious viral agents suspected of causing TM include varicella zoster, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, influenza, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis A, and rubella. It has also been postulated that an autoimmune reaction is responsible for the condition.

In some individuals, TM represents the first manifestation of an underlying demyelinating disorder such as multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica. A diagnosis of TM is made through patient history, physical examination, and characteristic findings on neuroimaging, specifically MRI.

Heroin use has long been associated with the development of TM, and is usually associated with IV administration of the drug after a period of abstinence.2 This association strengthens the basis for an immunologic etiology—an initial sensitization and subsequent reexposure causing the effects of TM. There have also been cases of TM coexisting with rhabdomyolysis due to the patient being found in a contorted position.3 Another theory of the etiology of heroin-associated TM is a reaction to a possible adulterant or contaminant in the heroin.4

What is the treatment and prognosis of transverse myelitis?

Since there is no cure for TM, treatment is directed at reducing inflammation in the spinal cord. Initial therapy generally includes corticosteroids. In patients with a minimal response to corticosteroids, plasma exchange can be attempted. There are also limited data to suggest a beneficial role for the use of IV immunoglobulin.5 In addition to treatment, general supportive care must also be optimized, such as the use of prophylaxis for thrombophlebitis due to immobility and physical therapy, if possible.

The prognosis of patients with TM is variable, and up to two thirds of patients will have moderate-to-severe residual neurological disability.6 Recovery is slow, with most patients beginning to show improvement within the first 2 to 12 weeks from treatment and supportive care. The recovery process can continue for 2 years. However, if no improvement is made within the first 3 to 6 months, recovery is unlikely.7 Cases of heroin-associated TM may have a more favorable prognosis.8

A majority of individuals will only experience this clinical entity once, but there are rare causes of recurrent or relapsing TM.7 In these situations, a search for underlying demyelinating diseases should be performed.

Case Conclusion

The patient was immediately started on IV corticosteroids, but as there was no improvement after 5 days, plasmapheresis was performed. She received 5 cycles of plasmapheresis and a 5-day course of IV immunoglobulin but still without any improvement. A repeat MRI of the thoracic spine was performed and raised the possibility of cord infarct, but infectious or inflammatory myelitis remained within differential consideration. The patient continued to make minimal improvement with physical therapy and, after a 3-week hospital course, she was transferred to inpatient rehabilitation for further care. Over the next 2 months, the loss of sensation and motor ability of her legs did not improve, but she did regain control of her bowels and bladder.

Dr Regina is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Pandit L. Transverse myelitis spectrum disorders. Neurol India. 2009;57(2):126-133.

- Richter RW, Rosenberg RN. Transverse myelitis associated with heroin addiction. JAMA. 1968;206(6):1255-1257.

- Sahni V, Garg D, Garg S, Agarwal SK, Singh NP. Unusual complications of heroin abuse: transverse myelitis, rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome, and ARF. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(2):153-155.

- Schein PS, Yessayan L, Mayman CI. Acute transverse myelitis associated with intravenous opium. Neurology. 1971;21(1):101-102.

- Absoud M, Gadian J, Hellier J, et al. Protocol for a multicentre randomiSed controlled TRial of IntraVEnous immunoglobulin versus standard therapy for the treatment of transverse myelitis in adults and children (STRIVE). BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e008312.

- West TW. Transverse myelitis--a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med. 2013;16(88):167-177.

- Transverse myelitis fact sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/transversemyelitis/detail_transversemyelitis.htm. Updated June 24, 2015. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- McGuire JL, Beslow LA, Finkel RS, Zimmerman RA, Henretig FM. A teenager with focal weakness. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(12):875-879.

Case

A 17-year-old adolescent girl with a history of depression and opioid dependence, for which she was taking buprenorphine until 2 weeks earlier, presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) after her father found her lying on the couch unresponsive and with shallow respirations. Naloxone was administered by EMS and her mental status improved.

At presentation, the patient admitted to insufflation of an unknown amount of heroin and ingestion of 2 mg of alprazolam earlier in the day. She denied any past or current use of intravenous (IV) drugs. During monitoring, she began to complain of numbness in her legs and an inability to urinate. Examination revealed paralysis and decreased sensation of her bilateral lower extremities to the midthigh, with decreased rectal tone. Because of the patient’s history of drug use and temporal association with the heroin overdose, both neurosurgery and toxicology services were consulted.

What can cause lower extremity paralysis in a drug user?

The differential diagnosis for the patient at this point included toxin-induced myelopathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hypokalemic periodic paralysis, spinal compression, epidural abscess, cerebrovascular accident, spinal lesion, and spinal artery dissection or infarction.

Although Guillain-Barré syndrome presents with ascending paralysis, there is usually an antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. While epidural abscess with spinal compression is associated with IV drug use and can present similarly, the patient in this case denied IV use. In the absence of any risk factors, cerebrovascular accident and spinal artery dissection were also unlikely.

Case Continuation

A bladder catheter was placed due to the patient’s inability to urinate, and approximately 1 L of urine output was retrieved. Immediate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated increased T2 signal intensity and expansion of the distal thoracic cord and conus without mass lesion, consistent with transverse myelitis (TM).

What is transverse myelitis and why does it occur?

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory demyelinating disorder that focally affects the spinal cord, resulting in a specific pattern of motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction.1 Signs and symptoms include paresthesia, paralysis of the extremities, and loss of bladder and bowel control. The level of the spinal cord affected determines the clinical effects. Demyelination typically occurs at the thoracic segment, producing findings in the legs, as well as bladder and bowel dysfunction.

The exact cause of TM is unknown, but the inflammation may result from a viral complication or an abnormal immune response. Infectious viral agents suspected of causing TM include varicella zoster, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, influenza, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis A, and rubella. It has also been postulated that an autoimmune reaction is responsible for the condition.

In some individuals, TM represents the first manifestation of an underlying demyelinating disorder such as multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica. A diagnosis of TM is made through patient history, physical examination, and characteristic findings on neuroimaging, specifically MRI.

Heroin use has long been associated with the development of TM, and is usually associated with IV administration of the drug after a period of abstinence.2 This association strengthens the basis for an immunologic etiology—an initial sensitization and subsequent reexposure causing the effects of TM. There have also been cases of TM coexisting with rhabdomyolysis due to the patient being found in a contorted position.3 Another theory of the etiology of heroin-associated TM is a reaction to a possible adulterant or contaminant in the heroin.4

What is the treatment and prognosis of transverse myelitis?

Since there is no cure for TM, treatment is directed at reducing inflammation in the spinal cord. Initial therapy generally includes corticosteroids. In patients with a minimal response to corticosteroids, plasma exchange can be attempted. There are also limited data to suggest a beneficial role for the use of IV immunoglobulin.5 In addition to treatment, general supportive care must also be optimized, such as the use of prophylaxis for thrombophlebitis due to immobility and physical therapy, if possible.

The prognosis of patients with TM is variable, and up to two thirds of patients will have moderate-to-severe residual neurological disability.6 Recovery is slow, with most patients beginning to show improvement within the first 2 to 12 weeks from treatment and supportive care. The recovery process can continue for 2 years. However, if no improvement is made within the first 3 to 6 months, recovery is unlikely.7 Cases of heroin-associated TM may have a more favorable prognosis.8

A majority of individuals will only experience this clinical entity once, but there are rare causes of recurrent or relapsing TM.7 In these situations, a search for underlying demyelinating diseases should be performed.

Case Conclusion

The patient was immediately started on IV corticosteroids, but as there was no improvement after 5 days, plasmapheresis was performed. She received 5 cycles of plasmapheresis and a 5-day course of IV immunoglobulin but still without any improvement. A repeat MRI of the thoracic spine was performed and raised the possibility of cord infarct, but infectious or inflammatory myelitis remained within differential consideration. The patient continued to make minimal improvement with physical therapy and, after a 3-week hospital course, she was transferred to inpatient rehabilitation for further care. Over the next 2 months, the loss of sensation and motor ability of her legs did not improve, but she did regain control of her bowels and bladder.

Dr Regina is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 17-year-old adolescent girl with a history of depression and opioid dependence, for which she was taking buprenorphine until 2 weeks earlier, presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) after her father found her lying on the couch unresponsive and with shallow respirations. Naloxone was administered by EMS and her mental status improved.

At presentation, the patient admitted to insufflation of an unknown amount of heroin and ingestion of 2 mg of alprazolam earlier in the day. She denied any past or current use of intravenous (IV) drugs. During monitoring, she began to complain of numbness in her legs and an inability to urinate. Examination revealed paralysis and decreased sensation of her bilateral lower extremities to the midthigh, with decreased rectal tone. Because of the patient’s history of drug use and temporal association with the heroin overdose, both neurosurgery and toxicology services were consulted.

What can cause lower extremity paralysis in a drug user?

The differential diagnosis for the patient at this point included toxin-induced myelopathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hypokalemic periodic paralysis, spinal compression, epidural abscess, cerebrovascular accident, spinal lesion, and spinal artery dissection or infarction.

Although Guillain-Barré syndrome presents with ascending paralysis, there is usually an antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. While epidural abscess with spinal compression is associated with IV drug use and can present similarly, the patient in this case denied IV use. In the absence of any risk factors, cerebrovascular accident and spinal artery dissection were also unlikely.

Case Continuation

A bladder catheter was placed due to the patient’s inability to urinate, and approximately 1 L of urine output was retrieved. Immediate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated increased T2 signal intensity and expansion of the distal thoracic cord and conus without mass lesion, consistent with transverse myelitis (TM).

What is transverse myelitis and why does it occur?

Transverse myelitis is an inflammatory demyelinating disorder that focally affects the spinal cord, resulting in a specific pattern of motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction.1 Signs and symptoms include paresthesia, paralysis of the extremities, and loss of bladder and bowel control. The level of the spinal cord affected determines the clinical effects. Demyelination typically occurs at the thoracic segment, producing findings in the legs, as well as bladder and bowel dysfunction.

The exact cause of TM is unknown, but the inflammation may result from a viral complication or an abnormal immune response. Infectious viral agents suspected of causing TM include varicella zoster, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, influenza, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis A, and rubella. It has also been postulated that an autoimmune reaction is responsible for the condition.

In some individuals, TM represents the first manifestation of an underlying demyelinating disorder such as multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica. A diagnosis of TM is made through patient history, physical examination, and characteristic findings on neuroimaging, specifically MRI.

Heroin use has long been associated with the development of TM, and is usually associated with IV administration of the drug after a period of abstinence.2 This association strengthens the basis for an immunologic etiology—an initial sensitization and subsequent reexposure causing the effects of TM. There have also been cases of TM coexisting with rhabdomyolysis due to the patient being found in a contorted position.3 Another theory of the etiology of heroin-associated TM is a reaction to a possible adulterant or contaminant in the heroin.4

What is the treatment and prognosis of transverse myelitis?

Since there is no cure for TM, treatment is directed at reducing inflammation in the spinal cord. Initial therapy generally includes corticosteroids. In patients with a minimal response to corticosteroids, plasma exchange can be attempted. There are also limited data to suggest a beneficial role for the use of IV immunoglobulin.5 In addition to treatment, general supportive care must also be optimized, such as the use of prophylaxis for thrombophlebitis due to immobility and physical therapy, if possible.

The prognosis of patients with TM is variable, and up to two thirds of patients will have moderate-to-severe residual neurological disability.6 Recovery is slow, with most patients beginning to show improvement within the first 2 to 12 weeks from treatment and supportive care. The recovery process can continue for 2 years. However, if no improvement is made within the first 3 to 6 months, recovery is unlikely.7 Cases of heroin-associated TM may have a more favorable prognosis.8

A majority of individuals will only experience this clinical entity once, but there are rare causes of recurrent or relapsing TM.7 In these situations, a search for underlying demyelinating diseases should be performed.

Case Conclusion

The patient was immediately started on IV corticosteroids, but as there was no improvement after 5 days, plasmapheresis was performed. She received 5 cycles of plasmapheresis and a 5-day course of IV immunoglobulin but still without any improvement. A repeat MRI of the thoracic spine was performed and raised the possibility of cord infarct, but infectious or inflammatory myelitis remained within differential consideration. The patient continued to make minimal improvement with physical therapy and, after a 3-week hospital course, she was transferred to inpatient rehabilitation for further care. Over the next 2 months, the loss of sensation and motor ability of her legs did not improve, but she did regain control of her bowels and bladder.

Dr Regina is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Pandit L. Transverse myelitis spectrum disorders. Neurol India. 2009;57(2):126-133.

- Richter RW, Rosenberg RN. Transverse myelitis associated with heroin addiction. JAMA. 1968;206(6):1255-1257.

- Sahni V, Garg D, Garg S, Agarwal SK, Singh NP. Unusual complications of heroin abuse: transverse myelitis, rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome, and ARF. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(2):153-155.

- Schein PS, Yessayan L, Mayman CI. Acute transverse myelitis associated with intravenous opium. Neurology. 1971;21(1):101-102.

- Absoud M, Gadian J, Hellier J, et al. Protocol for a multicentre randomiSed controlled TRial of IntraVEnous immunoglobulin versus standard therapy for the treatment of transverse myelitis in adults and children (STRIVE). BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e008312.

- West TW. Transverse myelitis--a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med. 2013;16(88):167-177.

- Transverse myelitis fact sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/transversemyelitis/detail_transversemyelitis.htm. Updated June 24, 2015. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- McGuire JL, Beslow LA, Finkel RS, Zimmerman RA, Henretig FM. A teenager with focal weakness. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(12):875-879.

- Pandit L. Transverse myelitis spectrum disorders. Neurol India. 2009;57(2):126-133.

- Richter RW, Rosenberg RN. Transverse myelitis associated with heroin addiction. JAMA. 1968;206(6):1255-1257.

- Sahni V, Garg D, Garg S, Agarwal SK, Singh NP. Unusual complications of heroin abuse: transverse myelitis, rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome, and ARF. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(2):153-155.

- Schein PS, Yessayan L, Mayman CI. Acute transverse myelitis associated with intravenous opium. Neurology. 1971;21(1):101-102.

- Absoud M, Gadian J, Hellier J, et al. Protocol for a multicentre randomiSed controlled TRial of IntraVEnous immunoglobulin versus standard therapy for the treatment of transverse myelitis in adults and children (STRIVE). BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e008312.

- West TW. Transverse myelitis--a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med. 2013;16(88):167-177.

- Transverse myelitis fact sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/transversemyelitis/detail_transversemyelitis.htm. Updated June 24, 2015. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- McGuire JL, Beslow LA, Finkel RS, Zimmerman RA, Henretig FM. A teenager with focal weakness. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(12):875-879.

Malpractice Counsel: Cervical Spine Injury

| An 83-year-old man presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) with a chief complaint of neck pain. He was the restrained driver of a car that was struck from behind by another vehicle. The patient denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, chest pain, shortness of breath, or abdominal pain. His medical history was significant for hypertension and coronary artery disease, for which he was taking several medications. Regarding his social history, the patient denied alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking. |

The patient’s physical examination was unremarkable. His vital signs were normal, and there was no obvious external evidence of trauma. The posterior cervical spine was tender to palpation in the midline, but no step-off signs were appreciated. The neurological examination, including strength and sensation in all four extremities, was normal.

Since the patient’s only complaint was neck pain and his physical examination and history were otherwise normal, the emergency physician (EP) ordered radiographs of the cervical spine. The imaging studies were interpreted as showing advanced degenerative changes but no fractures, and the patient was prescribed an analgesic and discharged home.

When the patient woke up the next morning, he was unable to move his extremities, and returned to the same ED via EMS. He was placed in a cervical collar and found to have flaccid extremities on examination. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the cervical spine revealed a transverse fracture through the C6 vertebra. Radiology services also reviewed the cervical spine X-rays from the previous day, noting the presence of fracture.

The patient was taken to the operating room by neurosurgery services but remained paralyzed postoperatively. He never recovered from his injury and died 6 months later. His family sued the EP and the hospital for missed diagnosis of cervical spine fracture at the first ED presentation and the resulting paralysis. The case was settled for $1.3 million prior to trial.

Discussion

The evaluation of suspected cervical spine injury secondary to blunt trauma is a frequent and important skill practiced by EPs. Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of spinal cord injury in the United States (42%), followed by falls (27%), acts of violence (15%), and sports-related injuries (8%).1 A review by Sekon and Fehlings2 showed that 55% of all spinal injuries involve the cervical spine. Interestingly, the majority of cervical spine injuries occur at the upper or lower ends of the cervical spine; C2 vertebral fractures account for 33%, while C6 and C7 vertebral fractures account for approximately 50%.1

There are two commonly used criteria to clinically clear the cervical spine (ie, no imaging studies necessary) in blunt-trauma patients. The first is the National Emergency X-Radiography Use Study (NEXUS), which has a sensitivity of 99.6% of identifying cervical spine fractures.1 According to the NEXUS criteria, no imaging studies are required if: (1) there is no midline cervical spine tenderness; (2) there are no focal neurological deficits; (3) the patient exhibits a normal level of alertness; (4) the patient is not intoxicated; and (5) there is no distracting injury.1

The other set of criteria used to clear the cervical spine is the Canadian Cervical Spine Rule. In these criteria, a patient is considered at very low risk for cervical spine fracture in the following cases: (1) the patient is fully alert with a Glasgow Coma scale of 15; (2) the patient has no high-risk factors (ie, age >65 years, dangerous mechanism of injury, fall greater than five stairs, axial load to the head, high-speed vehicular crash, bicycle or motorcycle crash, or the presence of paresthesias in the extremities); (3) the patient has low-risk factors (eg, simple vehicle crash, sitting position in the ED, ambulatory at any time, delayed onset of neck pain, and the absence of midline cervical tenderness); and (4) the patient can actively rotate his or her neck 45 degrees to the left and to the right. The Canadian group found the above criteria to have 100% sensitivity for predicting the absence of cervical spine injury.1

The patient in this case failed both sets of criteria (ie, presence of cervical spine tenderness and age >65 years) and therefore required imaging. Historically, cervical spine X-ray (three views, anteroposterior, lateral, and odontoid; or five views, three views plus obliques) has been the imaging study of choice for such patients. Unfortunately, however, cervical spine radiographs have severe limitations in identifying spinal injury. In a large retrospective review, Woodring and Lee,3 found that the standard three-view cervical spine series failed to demonstrate 61% of all fractures and 36% of all subluxation and dislocations. Similarly, in a prospective study of 1,006 patients with 72 injuries, Diaz et al,4 found a 52.3% missed fracture rate when five-view radiographs were used to identify cervical spine injury. In addition, radiographic evaluation of elderly patients was found to be even more challenging in identifying cervical spine injury due to age-related degenerative changes.

Given the abovementioned limitations associated with radiographic imaging, CT scan of the cervical spine has become the imaging study of choice in moderate-to-severe risk patients with blunt cervical spine trauma. This modality has been shown to have a higher sensitivity and specificity for evaluating cervical spine injury compared to plain X-ray films, with CT detecting 97% to 100% of cervical spine fractures.5

In addition to demonstrating a higher sensitivity, CT also has the advantage of speed—especially when the patient is undergoing other CT studies (eg, head, abdomen, pelvis). While some clinicians criticize the higher cost of CT versus plain films, CT has been shown to decrease institutional costs (when settlement costs are taken into account) due to the reduction of the incidence of paralysis resulting from false-negative imaging studies.6

Forgotten Tourniquet

| A 33-year-old woman presented to the ED with a chief complaint of left-sided abdominal and flank pain. She described the onset of pain as abrupt, severe, and lasting approximately 3 hours in duration. She admitted to nausea, but no vomiting. She also denied a history of any previous similar symptoms or recent trauma. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. Her last menstrual period began 3 days prior to presentation. Regarding social history, she denied any tobacco or alcohol use. |

The patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 138/82 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; temperature 98.6˚F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air.

The patient appeared uncomfortable overall. The physical examination was remarkable only for mild left-sided costovertebral angle tenderness. Her abdomen was soft, nontender, and without guarding or rebound.

The EP ordered the placement of an intravenous (IV) line, through which the patient was administered normal saline and morphine and promethazine, respectively, for pain and nausea. A complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine pregnancy test were ordered. All of the laboratory bloodwork results were normal, and the urine pregnancy test was negative. The urinalysis was remarkable for 50 to 100 red blood cells.

A noncontrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 3-mm ureteral stone on the left side. When the patient returned from radiology services, her pain was significantly decreased and she felt much improved. She was diagnosed with a kidney stone and discharged home with an analgesic and a strainer, along with instructions to follow-up with urology services. The patient was in the ED for a total of 5 hours.

The plaintiff sued the EP and hospital, claiming that the tourniquet used to start the IV line and draw blood was never removed, which in turn caused nerve damage resulting in reflex sympathetic dystrophy and complex regional pain syndrome. The defense denied all of these allegations, and the ED personnel testified that the tourniquet was removed as soon as the IV was established. The defense cited the plaintiff’s medical records, which contained documentation that the tourniquet had been removed. The defense further argued that if the tourniquet had been left on as the patient alleged, she would have experienced obvious physical signs, such as swelling, redness, infiltration of fluids, pain, and numbness. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

It is very tempting to simply dismiss this case as absurd, with nothing to be learned from it. It does defy common sense that no one would have noticed the tourniquet or, at the very least, that the patient would not have spoken up about it during her stay in the ED. While the jury clearly came to the correct conclusion, it does highlight a real problem: forgotten tourniquets.

According to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory (PPSA), there were 125 reports of tourniquets being left on patients in Pennsylvania healthcare facilities in 1 year alone.1 In 5% of these cases, the tourniquet was discovered within a half hour of application. In approximately 66% of cases, the tourniquet was left on for up to 2 hours, and the remaining were left in place for 2 to 18 hours.

Few locations within the hospital are without risk for this type of accident. The PPSA further noted that approximately 30% of retained tourniquets occurred on medical/surgical units, 14% in the ED, and 14% on inpatient and ambulatory surgical services departments. Approximately 19% were discovered when patients were transferred from one department to another.1

In the analysis of these incidents, contributing factors to forgotten tourniquets included staff failing to follow proper procedures, inadequate staff proficiency, and staff distractions and/or interruptions.1 In addition, some patients appeared to be at increased risk of having a retained tourniquet than others. Sixty percent of 125 patients with a forgotten tourniquet were aged 70 years or older, whereas some patients were younger than age 2 years.1 Not surprisingly, patients who were unable to verbally communicate (eg, patients who were intubated, under anesthesia, had expressive aphasia, severe dementia), were at the highest risk.

In a review of recovery room incidents, Salman and Asfar2 identified two cases of forgotten tourniquets out of approximately 7,000 patients. Potential strategies to avoid this mistake include: (1) only documenting procedures after they have been completed (eg, tourniquet removal); (2) double-checking that the tourniquet has been removed prior to leaving patient bedside; and (3) the use of extra-long tourniquets so the ends are more clearly visible.

Reference - Missed Cervical Spine Injury

- Looby S, Flanders A. Spine trauma. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(1):129-163.

- Sekon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(24 Suppl):S2-S12.

- Woodring JH, Lee C. Limitations of cervical radiography in the evaluation of acute cervical trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34(1):32-39.

- Diaz JJ Jr, Gillman C, Morris JA Jr, May AK, Carrillo YM, Guy J. Are five-view plain films of the cervical spine unreliable? A prospective evaluation in blunt trauma patients with altered mental status. J Trauma. 2003;55(4):658-663.

- Parizel PM, Zijden T, Gaudino S, et al. Trauma of the spine and spinal cord: imagining strategies. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(Suppl 1):S8-S17.

- Grogan EL, Morris JA Jr, Dittus RS, et al. Cervical spine evaluation in urban trauma centers: lowering institutional costs and complications through helical CT scan. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(2):160-165.

Reference - Forgotten Tourniquet

- Pennsylvania Safety Advisory. Forgotten but not gone: tourniquets left on patients. PA PSRS Patient Saf Advis. 2005;2(2):19-21.

- Salman JM, Asfar SN. Recovery room incidents. Bas J Surg. 2007;24:3.

| An 83-year-old man presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) with a chief complaint of neck pain. He was the restrained driver of a car that was struck from behind by another vehicle. The patient denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, chest pain, shortness of breath, or abdominal pain. His medical history was significant for hypertension and coronary artery disease, for which he was taking several medications. Regarding his social history, the patient denied alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking. |

The patient’s physical examination was unremarkable. His vital signs were normal, and there was no obvious external evidence of trauma. The posterior cervical spine was tender to palpation in the midline, but no step-off signs were appreciated. The neurological examination, including strength and sensation in all four extremities, was normal.

Since the patient’s only complaint was neck pain and his physical examination and history were otherwise normal, the emergency physician (EP) ordered radiographs of the cervical spine. The imaging studies were interpreted as showing advanced degenerative changes but no fractures, and the patient was prescribed an analgesic and discharged home.

When the patient woke up the next morning, he was unable to move his extremities, and returned to the same ED via EMS. He was placed in a cervical collar and found to have flaccid extremities on examination. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the cervical spine revealed a transverse fracture through the C6 vertebra. Radiology services also reviewed the cervical spine X-rays from the previous day, noting the presence of fracture.

The patient was taken to the operating room by neurosurgery services but remained paralyzed postoperatively. He never recovered from his injury and died 6 months later. His family sued the EP and the hospital for missed diagnosis of cervical spine fracture at the first ED presentation and the resulting paralysis. The case was settled for $1.3 million prior to trial.

Discussion

The evaluation of suspected cervical spine injury secondary to blunt trauma is a frequent and important skill practiced by EPs. Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of spinal cord injury in the United States (42%), followed by falls (27%), acts of violence (15%), and sports-related injuries (8%).1 A review by Sekon and Fehlings2 showed that 55% of all spinal injuries involve the cervical spine. Interestingly, the majority of cervical spine injuries occur at the upper or lower ends of the cervical spine; C2 vertebral fractures account for 33%, while C6 and C7 vertebral fractures account for approximately 50%.1

There are two commonly used criteria to clinically clear the cervical spine (ie, no imaging studies necessary) in blunt-trauma patients. The first is the National Emergency X-Radiography Use Study (NEXUS), which has a sensitivity of 99.6% of identifying cervical spine fractures.1 According to the NEXUS criteria, no imaging studies are required if: (1) there is no midline cervical spine tenderness; (2) there are no focal neurological deficits; (3) the patient exhibits a normal level of alertness; (4) the patient is not intoxicated; and (5) there is no distracting injury.1

The other set of criteria used to clear the cervical spine is the Canadian Cervical Spine Rule. In these criteria, a patient is considered at very low risk for cervical spine fracture in the following cases: (1) the patient is fully alert with a Glasgow Coma scale of 15; (2) the patient has no high-risk factors (ie, age >65 years, dangerous mechanism of injury, fall greater than five stairs, axial load to the head, high-speed vehicular crash, bicycle or motorcycle crash, or the presence of paresthesias in the extremities); (3) the patient has low-risk factors (eg, simple vehicle crash, sitting position in the ED, ambulatory at any time, delayed onset of neck pain, and the absence of midline cervical tenderness); and (4) the patient can actively rotate his or her neck 45 degrees to the left and to the right. The Canadian group found the above criteria to have 100% sensitivity for predicting the absence of cervical spine injury.1

The patient in this case failed both sets of criteria (ie, presence of cervical spine tenderness and age >65 years) and therefore required imaging. Historically, cervical spine X-ray (three views, anteroposterior, lateral, and odontoid; or five views, three views plus obliques) has been the imaging study of choice for such patients. Unfortunately, however, cervical spine radiographs have severe limitations in identifying spinal injury. In a large retrospective review, Woodring and Lee,3 found that the standard three-view cervical spine series failed to demonstrate 61% of all fractures and 36% of all subluxation and dislocations. Similarly, in a prospective study of 1,006 patients with 72 injuries, Diaz et al,4 found a 52.3% missed fracture rate when five-view radiographs were used to identify cervical spine injury. In addition, radiographic evaluation of elderly patients was found to be even more challenging in identifying cervical spine injury due to age-related degenerative changes.

Given the abovementioned limitations associated with radiographic imaging, CT scan of the cervical spine has become the imaging study of choice in moderate-to-severe risk patients with blunt cervical spine trauma. This modality has been shown to have a higher sensitivity and specificity for evaluating cervical spine injury compared to plain X-ray films, with CT detecting 97% to 100% of cervical spine fractures.5

In addition to demonstrating a higher sensitivity, CT also has the advantage of speed—especially when the patient is undergoing other CT studies (eg, head, abdomen, pelvis). While some clinicians criticize the higher cost of CT versus plain films, CT has been shown to decrease institutional costs (when settlement costs are taken into account) due to the reduction of the incidence of paralysis resulting from false-negative imaging studies.6

Forgotten Tourniquet

| A 33-year-old woman presented to the ED with a chief complaint of left-sided abdominal and flank pain. She described the onset of pain as abrupt, severe, and lasting approximately 3 hours in duration. She admitted to nausea, but no vomiting. She also denied a history of any previous similar symptoms or recent trauma. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. Her last menstrual period began 3 days prior to presentation. Regarding social history, she denied any tobacco or alcohol use. |

The patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 138/82 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; temperature 98.6˚F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air.

The patient appeared uncomfortable overall. The physical examination was remarkable only for mild left-sided costovertebral angle tenderness. Her abdomen was soft, nontender, and without guarding or rebound.

The EP ordered the placement of an intravenous (IV) line, through which the patient was administered normal saline and morphine and promethazine, respectively, for pain and nausea. A complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine pregnancy test were ordered. All of the laboratory bloodwork results were normal, and the urine pregnancy test was negative. The urinalysis was remarkable for 50 to 100 red blood cells.

A noncontrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 3-mm ureteral stone on the left side. When the patient returned from radiology services, her pain was significantly decreased and she felt much improved. She was diagnosed with a kidney stone and discharged home with an analgesic and a strainer, along with instructions to follow-up with urology services. The patient was in the ED for a total of 5 hours.

The plaintiff sued the EP and hospital, claiming that the tourniquet used to start the IV line and draw blood was never removed, which in turn caused nerve damage resulting in reflex sympathetic dystrophy and complex regional pain syndrome. The defense denied all of these allegations, and the ED personnel testified that the tourniquet was removed as soon as the IV was established. The defense cited the plaintiff’s medical records, which contained documentation that the tourniquet had been removed. The defense further argued that if the tourniquet had been left on as the patient alleged, she would have experienced obvious physical signs, such as swelling, redness, infiltration of fluids, pain, and numbness. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

It is very tempting to simply dismiss this case as absurd, with nothing to be learned from it. It does defy common sense that no one would have noticed the tourniquet or, at the very least, that the patient would not have spoken up about it during her stay in the ED. While the jury clearly came to the correct conclusion, it does highlight a real problem: forgotten tourniquets.

According to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory (PPSA), there were 125 reports of tourniquets being left on patients in Pennsylvania healthcare facilities in 1 year alone.1 In 5% of these cases, the tourniquet was discovered within a half hour of application. In approximately 66% of cases, the tourniquet was left on for up to 2 hours, and the remaining were left in place for 2 to 18 hours.

Few locations within the hospital are without risk for this type of accident. The PPSA further noted that approximately 30% of retained tourniquets occurred on medical/surgical units, 14% in the ED, and 14% on inpatient and ambulatory surgical services departments. Approximately 19% were discovered when patients were transferred from one department to another.1

In the analysis of these incidents, contributing factors to forgotten tourniquets included staff failing to follow proper procedures, inadequate staff proficiency, and staff distractions and/or interruptions.1 In addition, some patients appeared to be at increased risk of having a retained tourniquet than others. Sixty percent of 125 patients with a forgotten tourniquet were aged 70 years or older, whereas some patients were younger than age 2 years.1 Not surprisingly, patients who were unable to verbally communicate (eg, patients who were intubated, under anesthesia, had expressive aphasia, severe dementia), were at the highest risk.

In a review of recovery room incidents, Salman and Asfar2 identified two cases of forgotten tourniquets out of approximately 7,000 patients. Potential strategies to avoid this mistake include: (1) only documenting procedures after they have been completed (eg, tourniquet removal); (2) double-checking that the tourniquet has been removed prior to leaving patient bedside; and (3) the use of extra-long tourniquets so the ends are more clearly visible.

| An 83-year-old man presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) with a chief complaint of neck pain. He was the restrained driver of a car that was struck from behind by another vehicle. The patient denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, chest pain, shortness of breath, or abdominal pain. His medical history was significant for hypertension and coronary artery disease, for which he was taking several medications. Regarding his social history, the patient denied alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking. |

The patient’s physical examination was unremarkable. His vital signs were normal, and there was no obvious external evidence of trauma. The posterior cervical spine was tender to palpation in the midline, but no step-off signs were appreciated. The neurological examination, including strength and sensation in all four extremities, was normal.

Since the patient’s only complaint was neck pain and his physical examination and history were otherwise normal, the emergency physician (EP) ordered radiographs of the cervical spine. The imaging studies were interpreted as showing advanced degenerative changes but no fractures, and the patient was prescribed an analgesic and discharged home.

When the patient woke up the next morning, he was unable to move his extremities, and returned to the same ED via EMS. He was placed in a cervical collar and found to have flaccid extremities on examination. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the cervical spine revealed a transverse fracture through the C6 vertebra. Radiology services also reviewed the cervical spine X-rays from the previous day, noting the presence of fracture.

The patient was taken to the operating room by neurosurgery services but remained paralyzed postoperatively. He never recovered from his injury and died 6 months later. His family sued the EP and the hospital for missed diagnosis of cervical spine fracture at the first ED presentation and the resulting paralysis. The case was settled for $1.3 million prior to trial.

Discussion

The evaluation of suspected cervical spine injury secondary to blunt trauma is a frequent and important skill practiced by EPs. Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of spinal cord injury in the United States (42%), followed by falls (27%), acts of violence (15%), and sports-related injuries (8%).1 A review by Sekon and Fehlings2 showed that 55% of all spinal injuries involve the cervical spine. Interestingly, the majority of cervical spine injuries occur at the upper or lower ends of the cervical spine; C2 vertebral fractures account for 33%, while C6 and C7 vertebral fractures account for approximately 50%.1

There are two commonly used criteria to clinically clear the cervical spine (ie, no imaging studies necessary) in blunt-trauma patients. The first is the National Emergency X-Radiography Use Study (NEXUS), which has a sensitivity of 99.6% of identifying cervical spine fractures.1 According to the NEXUS criteria, no imaging studies are required if: (1) there is no midline cervical spine tenderness; (2) there are no focal neurological deficits; (3) the patient exhibits a normal level of alertness; (4) the patient is not intoxicated; and (5) there is no distracting injury.1

The other set of criteria used to clear the cervical spine is the Canadian Cervical Spine Rule. In these criteria, a patient is considered at very low risk for cervical spine fracture in the following cases: (1) the patient is fully alert with a Glasgow Coma scale of 15; (2) the patient has no high-risk factors (ie, age >65 years, dangerous mechanism of injury, fall greater than five stairs, axial load to the head, high-speed vehicular crash, bicycle or motorcycle crash, or the presence of paresthesias in the extremities); (3) the patient has low-risk factors (eg, simple vehicle crash, sitting position in the ED, ambulatory at any time, delayed onset of neck pain, and the absence of midline cervical tenderness); and (4) the patient can actively rotate his or her neck 45 degrees to the left and to the right. The Canadian group found the above criteria to have 100% sensitivity for predicting the absence of cervical spine injury.1

The patient in this case failed both sets of criteria (ie, presence of cervical spine tenderness and age >65 years) and therefore required imaging. Historically, cervical spine X-ray (three views, anteroposterior, lateral, and odontoid; or five views, three views plus obliques) has been the imaging study of choice for such patients. Unfortunately, however, cervical spine radiographs have severe limitations in identifying spinal injury. In a large retrospective review, Woodring and Lee,3 found that the standard three-view cervical spine series failed to demonstrate 61% of all fractures and 36% of all subluxation and dislocations. Similarly, in a prospective study of 1,006 patients with 72 injuries, Diaz et al,4 found a 52.3% missed fracture rate when five-view radiographs were used to identify cervical spine injury. In addition, radiographic evaluation of elderly patients was found to be even more challenging in identifying cervical spine injury due to age-related degenerative changes.

Given the abovementioned limitations associated with radiographic imaging, CT scan of the cervical spine has become the imaging study of choice in moderate-to-severe risk patients with blunt cervical spine trauma. This modality has been shown to have a higher sensitivity and specificity for evaluating cervical spine injury compared to plain X-ray films, with CT detecting 97% to 100% of cervical spine fractures.5

In addition to demonstrating a higher sensitivity, CT also has the advantage of speed—especially when the patient is undergoing other CT studies (eg, head, abdomen, pelvis). While some clinicians criticize the higher cost of CT versus plain films, CT has been shown to decrease institutional costs (when settlement costs are taken into account) due to the reduction of the incidence of paralysis resulting from false-negative imaging studies.6

Forgotten Tourniquet

| A 33-year-old woman presented to the ED with a chief complaint of left-sided abdominal and flank pain. She described the onset of pain as abrupt, severe, and lasting approximately 3 hours in duration. She admitted to nausea, but no vomiting. She also denied a history of any previous similar symptoms or recent trauma. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable. Her last menstrual period began 3 days prior to presentation. Regarding social history, she denied any tobacco or alcohol use. |

The patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 138/82 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/minute; temperature 98.6˚F. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air.

The patient appeared uncomfortable overall. The physical examination was remarkable only for mild left-sided costovertebral angle tenderness. Her abdomen was soft, nontender, and without guarding or rebound.

The EP ordered the placement of an intravenous (IV) line, through which the patient was administered normal saline and morphine and promethazine, respectively, for pain and nausea. A complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine pregnancy test were ordered. All of the laboratory bloodwork results were normal, and the urine pregnancy test was negative. The urinalysis was remarkable for 50 to 100 red blood cells.

A noncontrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 3-mm ureteral stone on the left side. When the patient returned from radiology services, her pain was significantly decreased and she felt much improved. She was diagnosed with a kidney stone and discharged home with an analgesic and a strainer, along with instructions to follow-up with urology services. The patient was in the ED for a total of 5 hours.

The plaintiff sued the EP and hospital, claiming that the tourniquet used to start the IV line and draw blood was never removed, which in turn caused nerve damage resulting in reflex sympathetic dystrophy and complex regional pain syndrome. The defense denied all of these allegations, and the ED personnel testified that the tourniquet was removed as soon as the IV was established. The defense cited the plaintiff’s medical records, which contained documentation that the tourniquet had been removed. The defense further argued that if the tourniquet had been left on as the patient alleged, she would have experienced obvious physical signs, such as swelling, redness, infiltration of fluids, pain, and numbness. A defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

It is very tempting to simply dismiss this case as absurd, with nothing to be learned from it. It does defy common sense that no one would have noticed the tourniquet or, at the very least, that the patient would not have spoken up about it during her stay in the ED. While the jury clearly came to the correct conclusion, it does highlight a real problem: forgotten tourniquets.

According to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Advisory (PPSA), there were 125 reports of tourniquets being left on patients in Pennsylvania healthcare facilities in 1 year alone.1 In 5% of these cases, the tourniquet was discovered within a half hour of application. In approximately 66% of cases, the tourniquet was left on for up to 2 hours, and the remaining were left in place for 2 to 18 hours.

Few locations within the hospital are without risk for this type of accident. The PPSA further noted that approximately 30% of retained tourniquets occurred on medical/surgical units, 14% in the ED, and 14% on inpatient and ambulatory surgical services departments. Approximately 19% were discovered when patients were transferred from one department to another.1

In the analysis of these incidents, contributing factors to forgotten tourniquets included staff failing to follow proper procedures, inadequate staff proficiency, and staff distractions and/or interruptions.1 In addition, some patients appeared to be at increased risk of having a retained tourniquet than others. Sixty percent of 125 patients with a forgotten tourniquet were aged 70 years or older, whereas some patients were younger than age 2 years.1 Not surprisingly, patients who were unable to verbally communicate (eg, patients who were intubated, under anesthesia, had expressive aphasia, severe dementia), were at the highest risk.

In a review of recovery room incidents, Salman and Asfar2 identified two cases of forgotten tourniquets out of approximately 7,000 patients. Potential strategies to avoid this mistake include: (1) only documenting procedures after they have been completed (eg, tourniquet removal); (2) double-checking that the tourniquet has been removed prior to leaving patient bedside; and (3) the use of extra-long tourniquets so the ends are more clearly visible.

Reference - Missed Cervical Spine Injury

- Looby S, Flanders A. Spine trauma. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(1):129-163.

- Sekon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(24 Suppl):S2-S12.

- Woodring JH, Lee C. Limitations of cervical radiography in the evaluation of acute cervical trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34(1):32-39.

- Diaz JJ Jr, Gillman C, Morris JA Jr, May AK, Carrillo YM, Guy J. Are five-view plain films of the cervical spine unreliable? A prospective evaluation in blunt trauma patients with altered mental status. J Trauma. 2003;55(4):658-663.

- Parizel PM, Zijden T, Gaudino S, et al. Trauma of the spine and spinal cord: imagining strategies. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(Suppl 1):S8-S17.

- Grogan EL, Morris JA Jr, Dittus RS, et al. Cervical spine evaluation in urban trauma centers: lowering institutional costs and complications through helical CT scan. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(2):160-165.

Reference - Forgotten Tourniquet

- Pennsylvania Safety Advisory. Forgotten but not gone: tourniquets left on patients. PA PSRS Patient Saf Advis. 2005;2(2):19-21.

- Salman JM, Asfar SN. Recovery room incidents. Bas J Surg. 2007;24:3.

Reference - Missed Cervical Spine Injury

- Looby S, Flanders A. Spine trauma. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(1):129-163.

- Sekon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(24 Suppl):S2-S12.

- Woodring JH, Lee C. Limitations of cervical radiography in the evaluation of acute cervical trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34(1):32-39.

- Diaz JJ Jr, Gillman C, Morris JA Jr, May AK, Carrillo YM, Guy J. Are five-view plain films of the cervical spine unreliable? A prospective evaluation in blunt trauma patients with altered mental status. J Trauma. 2003;55(4):658-663.

- Parizel PM, Zijden T, Gaudino S, et al. Trauma of the spine and spinal cord: imagining strategies. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(Suppl 1):S8-S17.

- Grogan EL, Morris JA Jr, Dittus RS, et al. Cervical spine evaluation in urban trauma centers: lowering institutional costs and complications through helical CT scan. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(2):160-165.

Reference - Forgotten Tourniquet

- Pennsylvania Safety Advisory. Forgotten but not gone: tourniquets left on patients. PA PSRS Patient Saf Advis. 2005;2(2):19-21.

- Salman JM, Asfar SN. Recovery room incidents. Bas J Surg. 2007;24:3.

Hospitalists Can Improve Healthcare Value

As the nation considers how to reduce healthcare costs, hospitalists can play a crucial role in this effort because they control many healthcare services through routine clinical decisions at the point of care. In fact, the government, payers, and the public now look to hospitalists as essential partners for reining in healthcare costs.[1, 2] The role of hospitalists is even more critical as payers, including Medicare, seek to shift reimbursements from volume to value.[1] Medicare's Value‐Based Purchasing program has already tied a percentage of hospital payments to metrics of quality, patient satisfaction, and cost,[1, 3] and Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Burwell announced that by the end of 2018, the goal is to have 50% of Medicare payments tied to quality or value through alternative payment models.[4]

Major opportunities for cost savings exist across the care continuum, particularly in postacute and transitional care, and hospitalist groups are leading innovative models that show promise for coordinating care and improving value.[5] Individual hospitalists are also in a unique position to provide high‐value care for their patients through advocating for appropriate care and leading local initiatives to improve value of care.[6, 7, 8] This commentary article aims to provide practicing hospitalists with a framework to incorporate these strategies into their daily work.

DESIGN STRATEGIES TO COORDINATE CARE

As delivery systems undertake the task of population health management, hospitalists will inevitably play a critical role in facilitating coordination between community, acute, and postacute care. During admission, discharge, and the hospitalization itself, standardizing care pathways for common hospital conditions such as pneumonia and cellulitis can be effective in decreasing utilization and improving clinical outcomes.[9, 10] Intermountain Healthcare in Utah has applied evidence‐based protocols to more than 60 clinical processes, re‐engineering roughly 80% of all care that they deliver.[11] These types of care redesigns and standardization promise to provide better, more efficient, and often safer care for more patients. Hospitalists can play important roles in developing and delivering on these pathways.

In addition, hospital physician discontinuity during admissions may lead to increased resource utilization, costs, and lower patient satisfaction.[12] Therefore, ensuring clear handoffs between inpatient providers, as well as with outpatient providers during transitions in care, is a vital component of delivering high‐value care. Of particular importance is the population of patients frequently readmitted to the hospital. Hospitalists are often well acquainted with these patients, and the myriad of psychosocial, economic, and environmental challenges this vulnerable population faces. Although care coordination programs are increasing in prevalence, data on their cost‐effectiveness are mixed, highlighting the need for testing innovations.[13] Certainly, hospitalists can be leaders adopting and documenting the effectiveness of spreading interventions that have been shown to be promising in improving care transitions at discharge, such as the Care Transitions Intervention, Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge), or the Transitional Care Model.[14, 15, 16]

The University of Chicago, through funding from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, is testing the use of a single physician who cares for frequently admitted patients both in and out of the hospital, thereby reducing the costs of coordination.[5] This comprehensivist model depends on physicians seeing patients in the hospital and then in a clinic located in or near the hospital for the subset of patients who stand to benefit most from this continuity. This differs from the old model of having primary care providers (PCPs) see inpatients and outpatients because the comprehensivist's patient panel is enriched with only patients who are at high risk for hospitalization, and thus these physicians have a more direct focus on hospital‐related care and higher daily hospitalized patient censuses, whereas PCPs were seeing fewer and fewer of their patients in the hospital on a daily basis. Evidence concerning the effectiveness of this model is expected by 2016. Hospitalists have also ventured out of the hospital into skilled nursing facilities, specializing in long‐term care.[17] These physicians are helping provide care to the roughly 1.6 million residents of US nursing homes.[17, 18] Preliminary evidence suggests increased physician staffing is associated with decreased hospitalization of nursing home residents.[18]

ADVOCATE FOR APPROPRIATE CARE

Hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care through avoiding low‐value services at the point of care, as well as learning and teaching about value.

Avoiding Low‐Value Services at the Point of Care

The largest contributor to the approximately $750 billion in annual healthcare waste is unnecessary services, which includes overuse, discretionary use beyond benchmarks, and unnecessary choice of higher‐cost services.[19] Drivers of overuse include medical culture, fee‐for‐service payments, patient expectations, and fear of malpractice litigation.[20] For practicing hospitalists, the most substantial motivation for overuse may be a desire to reassure patients and themselves.[21] Unfortunately, patients commonly overestimate the benefits and underestimate the potential harms of testing and treatments.[22] However, clear communication with patients can reduce overuse, underuse, and misuse.[23]

Specific targets for improving appropriate resource utilization may be identified from resources such as Choosing Wisely lists, guidelines, and appropriateness criteria. The Choosing Wisely campaign has brought together an unprecedented number of medical specialty societies to issue top five lists of things that physicians and patients should question (

| Adult Hospital Medicine Recommendations | Pediatric Hospital Medicine Recommendations |

|---|---|

| 1. Do not place, or leave in place, urinary catheters for incontinence or convenience, or monitoring of output for noncritically ill patients (acceptable indications: critical illness, obstruction, hospice, perioperatively for <2 days or urologic procedures; use weights instead to monitor diuresis). | 1. Do not order chest radiographs in children with uncomplicated asthma or bronchiolitis. |

| 2. Do not prescribe medications for stress ulcer prophylaxis to medical inpatients unless at high risk for gastrointestinal complication. | 2. Do not routinely use bronchodilators in children with bronchiolitis. |

| 3. Avoid transfusing red blood cells just because hemoglobin levels are below arbitrary thresholds such as 10, 9, or even 8 mg/dL in the absence of symptoms. | 3. Do not use systemic corticosteroids in children under 2 years of age with an uncomplicated lower respiratory tract infection. |

| 4. Avoid overuse/unnecessary use of telemetry monitoring in the hospital, particularly for patients at low risk for adverse cardiac outcomes. | 4. Do not treat gastroesophageal reflux in infants routinely with acid suppression therapy. |

| 5. Do not perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability. | 5. Do not use continuous pulse oximetry routinely in children with acute respiratory illness unless they are on supplemental oxygen. |

As an example of this strategy, 1 multi‐institutional group has started training medical students to augment the traditional subjective‐objective‐assessment‐plan (SOAP) daily template with a value section (SOAP‐V), creating a cognitive forcing function to promote discussion of high‐value care delivery.[28] Physicians could include brief thoughts in this section about why they chose a specific intervention, their consideration of the potential benefits and harms compared to alternatives, how it may incorporate the patient's goals and values, and the known and potential costs of the intervention. Similarly, Flanders and Saint recommend that daily progress notes and sign‐outs include the indication, day of administration, and expected duration of therapy for all antimicrobial treatments, as a mechanism for curbing antimicrobial overuse in hospitalized patients.[29] Likewise, hospitalists can also document whether or not a patient needs routine labs, telemetry, continuous pulse oximetry, or other interventions or monitoring. It is not yet clear how effective this type of strategy will be, and drawbacks include creating longer progress notes and requiring more time for documentation. Another approach would be to work with the electronic health record to flag patients who are scheduled for telemetry or other potentially wasteful practices to inspire a daily practice audit to question whether the patient still meets criteria for such care. This approach acknowledges that patient's clinical status changes, and overcomes the inertia that results in so many therapies being continued despite a need or indication.

Communicating With Patients Who Want Everything

Some patients may be more worried about not getting every possible test, rather than concerns regarding associated costs. This may oftentimes be related to patients routinely overestimating the benefits of testing and treatments while not realizing the many potential downstream harms.[22] The perception is that patient demands frequently drive overtesting, but studies suggest the demanding patient is actually much less common than most physicians think.[30]

The Choosing Wisely campaign features video modules that provide a framework and specific examples for physician‐patient communication around some of the Choosing Wisely recommendations (available at:

Clinicians can explain why they do not believe that a test will help a patient and can share their concerns about the potential harms and downstream consequences of a given test. In addition, Consumer Reports and other groups have created trusted resources for patients that provide clear information for the public about unnecessary testing and services.

Learn and Teach Value

Traditionally, healthcare costs have largely remained hidden from both the public and medical professionals.[31, 32] As a result, hospitalists are generally not aware of the costs associated with their care.[33, 34] Although medical education has historically avoided the topic of healthcare costs,[35] recent calls to teach healthcare value have led to new educational efforts.[35, 36, 37] Future generations of medical professionals will be trained in these skills, but current hospitalists should seek opportunities to improve their knowledge of healthcare value and costs.

Fortunately, several resources can fill this gap. In addition to Choosing Wisely and ACR appropriateness criteria discussed above, newer tools focus on how to operationalize these recommendations with patients. The American College of Physicians (ACP) has launched a high‐value care educational platform that includes clinical recommendations, physician resources, curricula and public policy recommendations, and patient resources to help them understand the benefits, harms, and costs of tests and treatments for common clinical issues (

In an effort to provide frontline clinicians with the knowledge and tools necessary to address healthcare value, we have authored a textbook, Understanding Value‐Based Healthcare.[38] To identify the most promising ways of teaching these concepts, we also host the annual Teaching Value & Choosing Wisely Challenge and convene the Teaching Value in Healthcare Learning Network (bit.ly/teachingvaluenetwork) through our nonprofit, Costs of Care.[39]

In addition, hospitalists can also advocate for greater price transparency to help improve cost awareness and drive more appropriate care. The evidence on the effect of transparent costs in the electronic ordering system is evolving. Historically, efforts to provide diagnostic test prices at time of order led to mixed results,[40] but recent studies show clear benefits in resource utilization related to some form of cost display.[41, 42] This may be because physicians care more about healthcare costs and resource utilization than before. Feldman and colleagues found in a controlled clinical trial at Johns Hopkins that providing the costs of lab tests resulted in substantial decreases of certain lab tests and yielded a net cost reduction (based on 2011 Medicare Allowable Rate) of more than $400,000 at the hospital level during the 6‐month intervention period.[41] A recent systematic review concluded that charge information changed ordering and prescribing behavior in the majority of studies.[42] Some hospitalist programs are developing dashboards for various quality and utilization metrics. Sharing ratings or metrics internally or publically is a powerful way to motivate behavior change.[43]

LEAD LOCAL VALUE INITIATIVES

Hospitalists are ideal leaders of local value initiatives, whether it be through running value‐improvement projects or launching formal high‐value care programs.

Conduct Value‐Improvement Projects

Hospitalists across the country have largely taken the lead on designing value‐improvement pilots, programs, and groups within hospitals. Although value‐improvement projects may be built upon the established structures and techniques for quality improvement, importantly these programs should also include expertise in cost analyses.[8] Furthermore, some traditional quality‐improvement programs have failed to result in actual cost savings[44]; thus, it is not enough to simply rebrand quality improvement with a banner of value. Value‐improvement efforts must overcome the cultural hurdle of more care as better care, as well as pay careful attention to the diplomacy required with value improvement, because reducing costs may result in decreased revenue for certain departments or even decreases in individuals' wages.

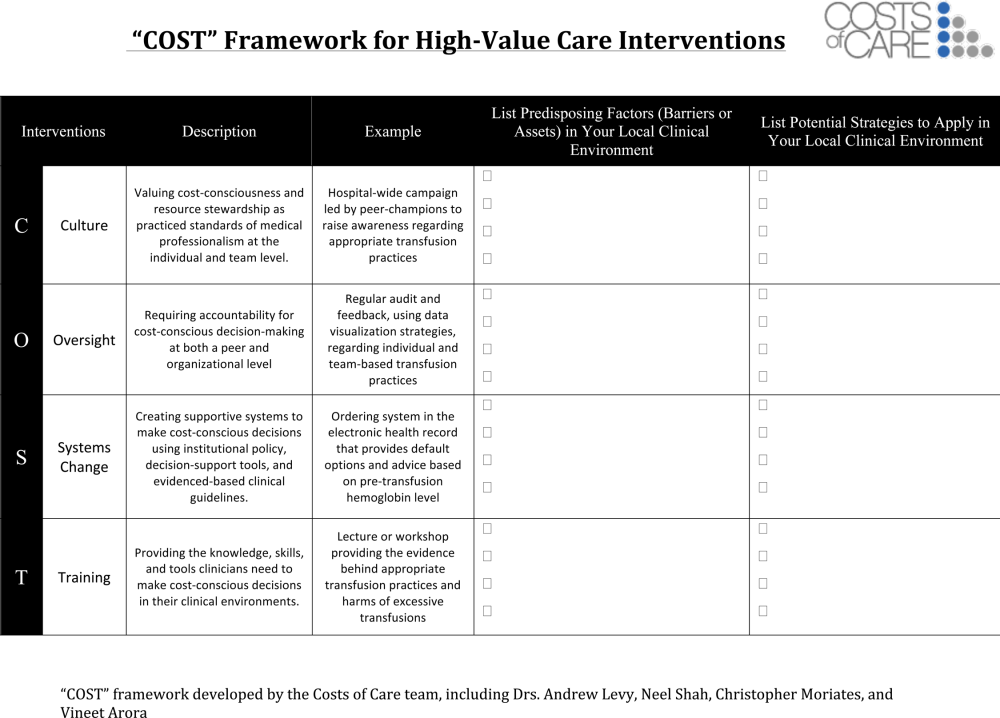

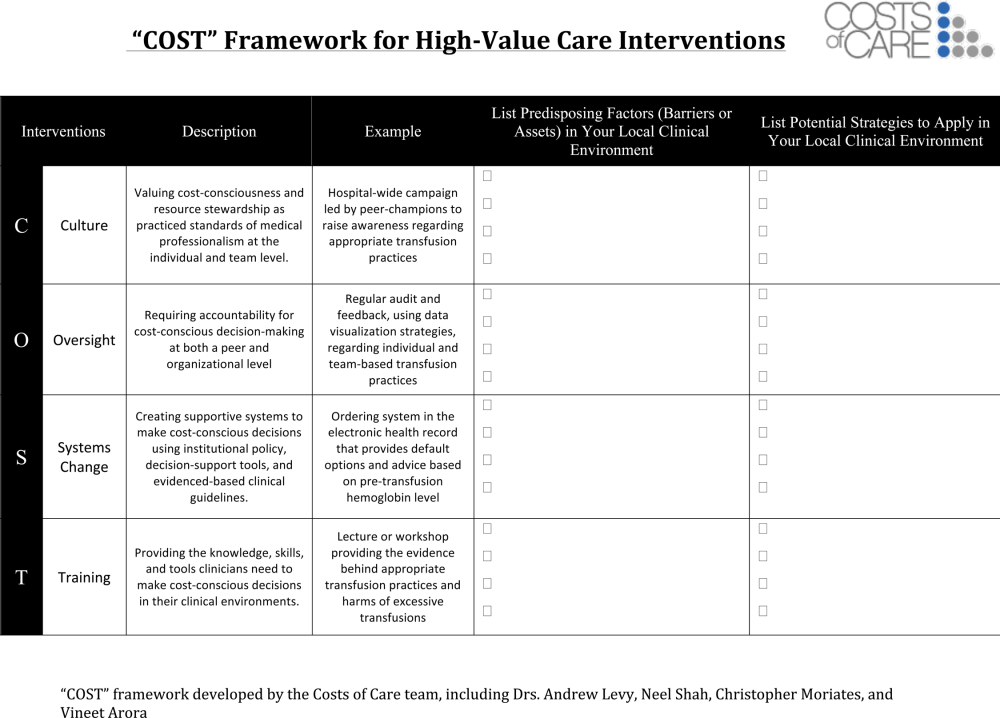

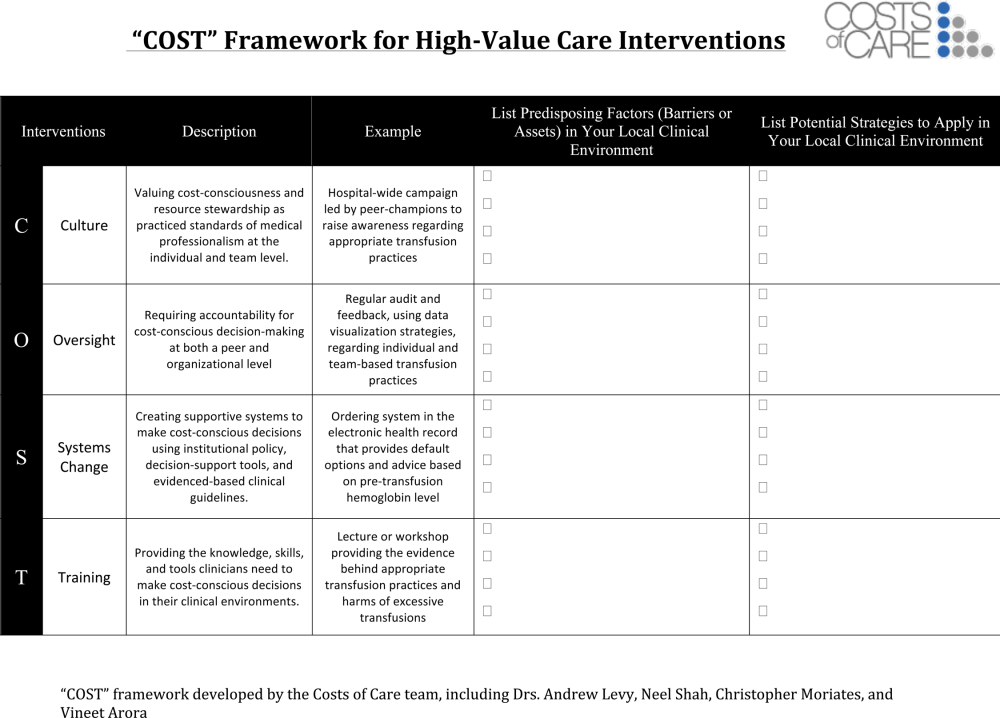

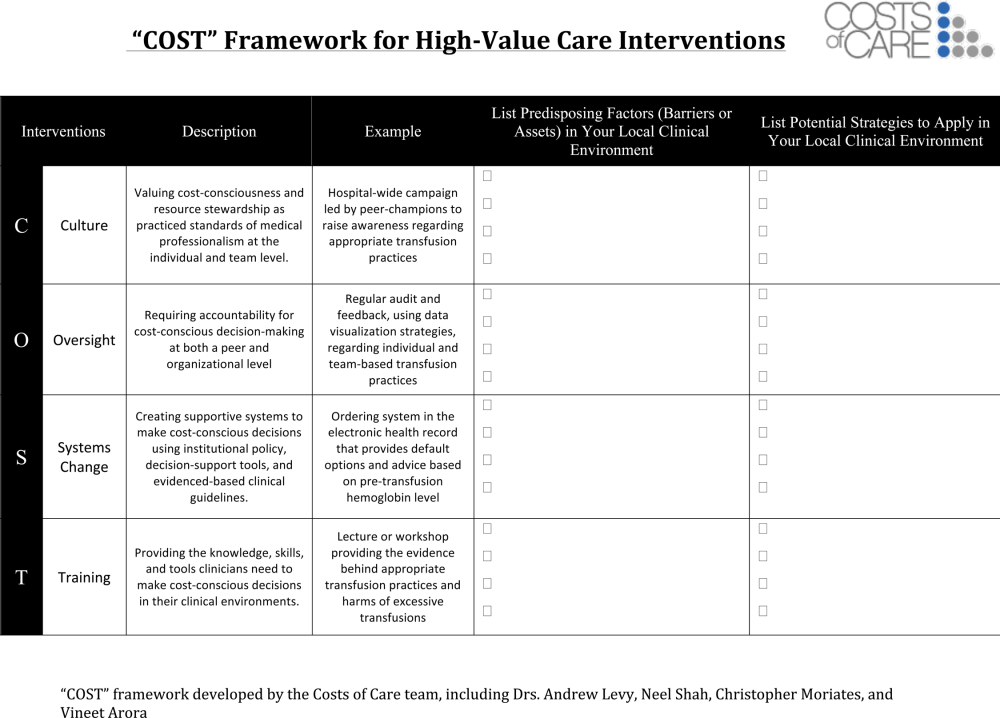

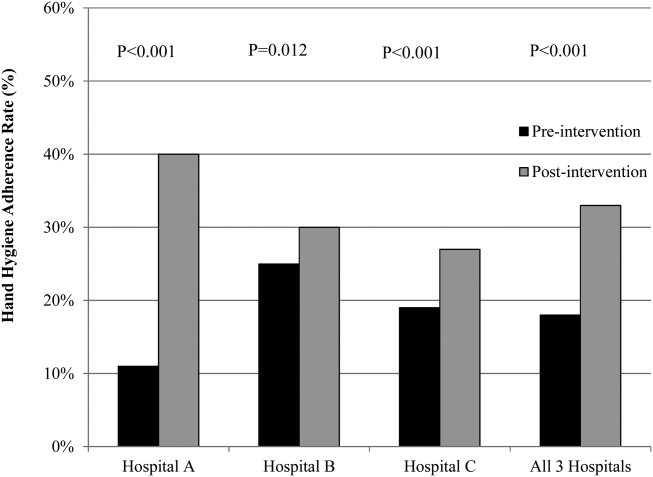

One framework that we have used to guide value‐improvement project design is COST: culture, oversight accountability, system support, and training.[45] This approach leverages principles from implementation science to ensure that value‐improvement projects successfully provide multipronged tactics for overcoming the many barriers to high‐value care delivery. Figure 1 includes a worksheet for individual clinicians or teams to use when initially planning value‐improvement project interventions.[46] The examples in this worksheet come from a successful project at the University of California, San Francisco aimed at improving blood utilization stewardship by supporting adherence to a restrictive transfusion strategy. To address culture, a hospital‐wide campaign was led by physician peer champions to raise awareness about appropriate transfusion practices. This included posters that featured prominent local physician leaders displaying their support for the program. Oversight was provided through regular audit and feedback. Each month the number of patients on the medicine service who received transfusion with a pretransfusion hemoglobin above 8 grams per deciliter was shared at a faculty lunch meeting and shown on a graph included in the quality newsletter that was widely distributed in the hospital. The ordering system in the electronic medical record was eventually modified to include the patient's pretransfusion hemoglobin level at time of transfusion order and to provide default options and advice based on whether or not guidelines would generally recommend transfusion. Hospitalists and resident physicians were trained through multiple lectures and informal teaching settings about the rationale behind the changes and the evidence that supported a restrictive transfusion strategy.

Launch High‐Value Care Programs

As value‐improvement projects grow, some institutions have created high‐value care programs and infrastructure. In March 2012, the University of California, San Francisco Division of Hospital Medicine launched a high‐value care program to promote healthcare value and clinician engagement.[8] The program was led by clinical hospitalists alongside a financial administrator, and aimed to use financial data to identify areas with clear evidence of waste, create evidence‐based interventions that would simultaneously improve quality while cutting costs, and pair interventions with cost awareness education and culture change efforts. In the first year of this program, 6 projects were launched targeting: (1) nebulizer to inhaler transitions,[47] (2) overuse of proton pump inhibitor stress ulcer prophlaxis,[48] (3) transfusions, (4) telemetry, (5) ionized calcium lab ordering, and (6) repeat inpatient echocardiograms.[8]

Similar hospitalist‐led groups have now formed across the country including the Johns Hopkins High‐Value Care Committee, Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians for Responsible Ordering, and High‐Value Carolina. These groups are relatively new, and best practices and early lessons are still emerging, but all focus on engaging frontline clinicians in choosing targets and leading multipronged intervention efforts.

What About Financial Incentives?

Hospitalist high‐value care groups thus far have mostly focused on intrinsic motivations for decreasing waste by appealing to hospitalists' sense of professionalism and their commitment to improve patient affordability. When financial incentives are used, it is important that they are well aligned with internal motivations for clinicians to provide the best possible care to their patients. The Institute of Medicine recommends that payments are structured in a way to reward continuous learning and improvement in the provision of best care at lower cost.[19] In the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, physician incentives are designed to reward teamwork and collaboration. For example, endocrinologists' goals are based on good control of glucose levels for all diabetes patients in the system, not just those they see.[49] Moreover, a collaborative approach is encouraged by bringing clinicians together across disciplinary service lines to plan, budget, and evaluate one another's performance. These efforts are partly credited with a 43% reduction in hospitalized days and $100 per member per month in savings among diabetic patients.[50]

Healthcare leaders, Drs. Tom Lee and Toby Cosgrove, have made a number of recommendations for creating incentives that lead to sustainable changes in care delivery[49]: avoid attaching large sums to any single target, watch for conflicts of interest, reward collaboration, and communicate the incentive program and goals clearly to clinicians.

In general, when appropriate extrinsic motivators align or interact synergistically with intrinsic motivation, it can promote high levels of performance and satisfaction.[51]

CONCLUSIONS

Hospitalists are now faced with a responsibility to reduce financial harm and provide high‐value care. To achieve this goal, hospitalist groups are developing innovative models for care across the continuum from hospital to home, and individual hospitalists can advocate for appropriate care and lead value‐improvement initiatives in hospitals. Through existing knowledge and new frameworks and tools that specifically address value, hospitalists can champion value at the bedside and ensure their patients get the best possible care at lower costs.