User login

Woman, 78, With Dyspnea, Dry Cough, and Fatigue

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of shortness of breath, a dry nonproductive cough, fatigue, hypoxia, and general malaise lasting for several months and worsening over a two-week period. She denied having fever, chills, hemoptysis, weight loss, headache, rashes, or joint pain. She reported sweats, decrease in appetite, wheezing, cough without sputum production, and slight swelling of the legs. The patient complained of chest pain upon admission, but it resolved quickly.

The patient, a retired widow with five grown children, denied recent surgery or exposure to sick people, had not travelled, and reported no changes in her home environment. She claimed to have no pets but admitted to currently smoking about four cigarettes a day; she had previously smoked, on average, three packs of cigarettes per day for 60 years. She denied using alcohol or drugs, including intravenous agents.

The patient’s medical history was significant for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. She had also been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), transient ischemic attack, patent foramen ovale, hyperlipidemia, seizure disorder, and hypothyroidism. She had no known HIV risk factors and had had no exposure to asbestos or tuberculosis.

The patient’s current medications included amiodarone (200 mg/d) for four years; valproic acid (500 mg/d); aspirin (325 mg/d); levothyroxine (50 g/d); rosuvastatin (10 mg/d); daily warfarin, dosed according to the international normalized ratio (INR); and budesonide/formoterol (160/4.5 mg, one puff bid). She denied having any drug allergies.

Physical examination in the ED revealed a pulse of 63 beats/min; blood pressure, 108/50 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 16 to 20 breaths/min. The patient’s O2 saturation was 84% on room air; 82% to 84% on 4 L to 6 L of supplemental oxygen; 87% to 92% with a venturi mask; and 95% on biphasic positive airway pressure (BiPAP) device. She was afebrile with hypoxia and able to speak in full sentences. Crackles were detected in the upper lung fields, best heard anteriorly, as well as a few scattered wheezes and rhonchi. Her heart sounds were normal with a regular rhythm; her extremities exhibited trace edema bilaterally. The remainder of the physical exam was normal.

The patient’s laboratory values included a normal white blood cell (WBC) count, elevated lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) at 448 IU/L (reference range, 84 to 246 IU/L), and no eosinophils. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was not measured on admission. Blood analysis of her N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was 4,877 pg/mL; for women older than 75, a level higher than 1,800 pg/mL is abnormal.

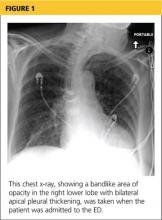

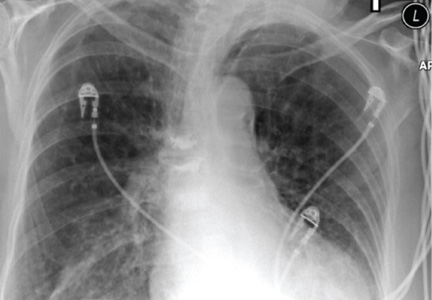

A chest x-ray was performed on admission, showing hyperinflation of the lungs with mild coarsening of the lung markings. A bandlike area of opacity in the right lower lobe with bilateral apical pleural thickening was noted (see Figure 1). Noncontrast CT of the chest revealed diffuse upper lobe ground glass opacities in both lungs, extending into the right middle lobe and lingula as well the superior segments of the lower lobes, with areas of emphysema and septal thickening. Numerous nodules, some of which appeared cavitary, were apparent in the lower lobes.

A two-dimensional echocardiogram demonstrated normal left ventricular size and systolic function, mild tricuspid regurgitation without evidence of pulmonary hypertension, and mild left atrial enlargement.

The patient was admitted to the cardiac unit for evaluation. While there, she received one dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg IV), three doses of ipratropium bromide/albuterol, one dose of ceftriaxone (1 g IV), and one dose of azithromycin (500 mg po). In the absence of significant leg edema and an elevation of jugular venous distention with a normal two-dimensional echocardiogram, heart failure was ruled out. The chest pains reported on initial presentation were ultimately felt to be noncardiac in nature.

After the patient was transferred to the medical floor with an initial diagnosis of exacerbation of her COPD, she was treated with antibiotics, nebulizers, and corticosteroids. She continued to experience episodes of O2 desaturation while on 4 L to 6 L of oxygen via nasal cannula and on a venturi mask. She was then placed on a BiPAP device, set to 12/5, and 50% Fio2 (fraction of inspired oxygen), which improved her oxygenation.

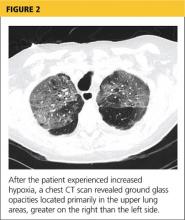

Her hypoxia prompted further radiographic studies. The resulting chest CT scan showed ground glass opacities located primarily in the upper lung areas, greater on the right than on the left side (see Figure 2). The radiologist suggested that the hypoxia was caused by an infection, but because the patient’s presenting symptoms were chronic in nature, drug-induced causes were considered as well. Amiodarone was discontinued.

Cardiology was consulted and agreed that stopping amiodarone was acceptable since the patient was in sinus rhythm at the time. The patient continued to take antibiotics and prednisone. Her symptoms slowly improved during hospitalization, and she required less oxygen. Based on the patient’s presentation, physical exam findings, imaging studies, and laboratory findings, amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity (APT) was diagnosed.

She was discharged home on supplemental oxygen at 4 L via cannula, a tapering dosage of prednisone, and metered-dose inhalers for fluticasone/salmeterol and tiotropium bromide. She also had outpatient appointments scheduled, one with the pulmonologist to follow up on her imaging studies and to manage the prednisone taper and the other with the cardiologist to manage her atrial fibrillation.

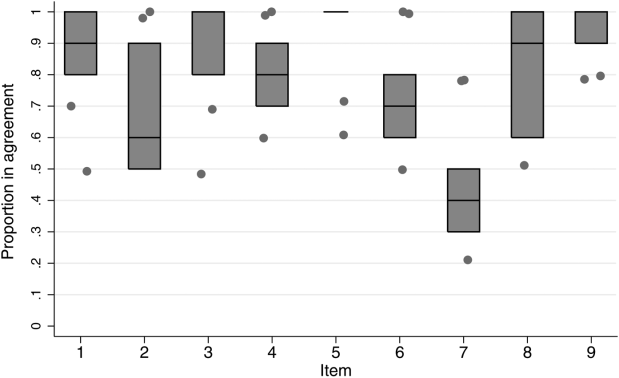

At pulmonology two months later, she had a chest x-ray (see Figure 3) and pulmonary function tests (PFTs). The patient reported feeling progressively better in the past month. Her dyspnea on exertion had improved, and she did not require supplemental oxygen anymore. She stopped smoking cigarettes.

The patient continued to use fluticasone/salmeterol but stopped tiotropium bromide. On physical exam, her O2 saturation was 95% on room air, heart rhythm and rate were regular, and her lungs revealed very minimal crackles at the right base but were otherwise clear.

The plan specified continuing the prednisone taper. The patient was asked to call the office if she had any worsening shortness of breath, cough, and sputum production. She was also encouraged to continue refraining from smoking cigarettes. This patient had done very well, with near complete resolution of symptoms and a clear chest x-ray.

Continue reading for discussion...

DISCUSSION

Amiodarone, a highly effective antiarrhythmic drug, is FDA approved for suppressing ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. It is also used off-label as a second- or third-line choice for atrial fibrillation.1

Standard of care requires that, prior to starting amiodarone therapy, patients have a baseline chest x-ray and PFTs with diffusing capacity performed. Thereafter, the patient should be monitored with annual chest x-rays, with one performed promptly if new symptoms develop. Serial PFTs have not offered any benefit for monitoring, but a decrease of more than 15% in total lung capacity or more than 20% in diffusing capacity from baseline is consistent with APT.2

Adverse effects, both cardiac and noncardiac, are common with amiodarone therapy. They include proarrhythmias, bradycardia, and heart block, as well as thyroid and liver dysfunctions; dermatologic conditions such as blue-gray discoloration of the skin and photosensitivity; neurologic effects such as ataxia, paresthesias, and tremor; ocular problems, including corneal microdeposits; gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, anorexia, and constipation; and lung problems such as pulmonary toxicity, pleural effusion, and pleural thickening.3-6 Of these, pulmonary toxicity is the most severe and life threatening.7

APT, also known as amiodarone pneumonitis and amiodarone lung, typically manifests from a few months to a year and a half after treatment is commenced.6 APT can occur even after the drug is discontinued, because amiodarone has a very long elimination half-life of approximately 15 to 45 days and a tendency to concentrate in organs with high blood perfusion and in adipose tissues.8 Patients taking 400 mg/d for two months or longer or 200 mg/d for more than two years are considered at higher risk for APT.9 The severity of disease appears to correlate with the cumulative dose and length of treatment.10

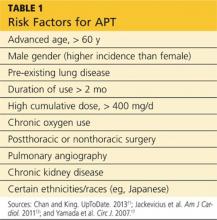

Numerous risk factors for pulmonary toxicity have been reported, including high drug dosage, pre-existing lung disease, patient age, and prior surgery (see Table 1).11 According to an analysis of a database of 237 patients, only age and duration of amiodarone therapy were significant risk factors for APT.9 Its incidence is not precisely known; reported rates range from 1% to 17%.6,12,13

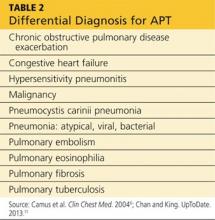

Presentation with such nonspecific symptoms as shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, fatigue, hypoxia, and general malaise is typical for many pulmonary and cardiac illnesses (see Table 2), making APT difficult to diagnose.14 Occasionally, rapid onset with progression to pneumonitis and respiratory failure masquerades as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).15

Notable, however, is that APT can manifest with nonproductive cough and dyspnea in 50% to 75% of cases. In addition, presenting symptoms will include fever (33% to 50% of cases) with associated malaise, fatigue, chest pain, and weight loss. In patients with APT, the physical exam usually reveals bilateral crackles on inspiration, but diffuse rales may be heard as well.11

Laboratory studies are not very helpful in diagnosing APT. Patients may present with nonspecific elevated WBCs without eosinophilia and an elevated LDH level.11 An elevated ESR may be detected before symptoms of APT manifest and can be present at the time of diagnosis.6

Imaging studies are far more helpful and specific in diagnosing APT. The typical chest x-ray shows bilateral patchy diffuse infiltrates.12 CT of the chest is usually more revealing, demonstrating ground glass opacities in the periphery and subpleural thickening, especially where infiltrates are denser. This thickening may result in pleuritic chest pain.6

The right upper lobe is more often affected in these cases than the left lung.6 Numerous pulmonary nodules in the upper lobes are found rarely and can be confused with lung cancer. These nodules are likely the result of an accumulation of the drug in areas of previous inflammation; a lung mass should prompt the addition of APT in the differential.2,16

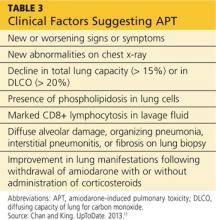

APT is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring clinical suspicion, drug history, imaging, and consideration of the differential. The presence of three or more clinical factors supports a diagnosis of APT (see Table 3).11

Once APT is recognized, the first action is to have the patient stop taking amiodarone, followed by the administration of corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 40 to 60 mg/d11) for four to 12 months.17 Patients, especially those with underlying lung disease, will typically require temporary oxygen supplementation until hypoxia resolves. Even after the drug has been discontinued, some patients experience worsening symptoms before they see improvement simply because the drug can persist in lung tissue for up to a year following cessation of therapy.6

If APT is diagnosed early, the prognosis is favorable. In one study, a significant number of APT patients stabilized or improved after withdrawal of the drug, regardless of concurrent treatment with corticosteroids.18 Follow-up studies, both imaging and PFT, indicate complete clearing of lung opacities in the majority of patients treated for APT.19 Radiologic improvement may be seen six months after cessation of amiodarone.20 Patients who develop ARDS tend to do poorly and have a mortality rate of approximately 50%.11

Continue reading for the conclusion...

CONCLUSION

Among patients who are taking long-term or high-dose amiodarone, particularly those older than 60, new-onset nonproductive cough and dyspnea signal the need for pulmonary and cardiac work-up. Once the diagnosis of APT is made, treatment is straightforward: Withdraw the amiodarone, and initiate corticosteroid therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Fuster V, Rydén LE, Asinger RW, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation); North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Circulation. 2001; 104(17):2118-2150.

2. Jarand J, Lee A, Leigh R. Amiodaronoma: an unusual form of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. CMAJ. 2007;176(10):1411-1413.

3. Connolly S. Evidence-based analysis of amiodarone efficacy and safety. Circulation. 1999;100:2025-2034.

4. Amiodarone Trials Meta-Analysis Investigators. Effect of prophylactic amiodarone on mortality after acute myocardial infarction and in congestive heart failure: meta-analysis of individual data from 6500 patients in randomised trials. Lancet. 1997;350(9089):1417-1424.

5. Pollak PT. Clinical organ toxicity of antiarrhythmic compounds: ocular and pulmonary manifestations. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(9A):37R-45R.

6. Camus P, Martin W, Rosenow E. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25(1):65-75.

7. Rady MY, Ryan T, Starr NJ. Preoperative therapy with amiodarone and the incidence of acute organ dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(3):489-497.

8. Canada A, Lesko L, Haffajee C, et al. Amiodarone for tachyarrhythmias: kinetics, and efficacy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1983;17(2):100-104.

9. Ernawati DK, Stafford L, Hughes JD. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):82-87.

10. Liu FL, Cohen RD, Downar E, et al. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity: functional and ultrastructural evaluation. Thorax. 1986;41(2):100-105.

11. Chan E, King TE. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. UpToDate. 2013. www.uptodate.com/contents/amiodarone-pulmonary-toxicity. Accessed January 17, 2014.

12. Wolkove N, Baltzan M. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Can Respir J. 2009;16(2):43-48.

13. Jackevicius CA, Tom A, Essebag V, et al. Population-level incidence and risk factors for pulmonary toxicity associated with amiodarone. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:705-710.

14. Jessurun G, Crijns H. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity [editorial]. BMJ. 1997;314(7081):619-620.

15. Nacca N, Castigliano B, Yuhico L, et al. Severe amiodarone induced pulmonary toxicity. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(6):667-670.

16. Arnon R, Raz I, Chajek-Shaul T, et al. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity presenting as a solitary lung mass. Chest. 1988;93(2):425-427.

17. Yamada Y, Shiga T, Matsuda N, et al. Incidence and predictors of pulmonary toxicity in Japanese patients receiving low-dose amiodarone. Circ J. 2007;71(10):1610-1616.

18. Coudert B, Bailly F, Lombard JN, et al. Amiodarone pneumonitis: bronchoalveolar lavage findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. Chest. 1992;102(4):1005-1012.

19. Vernhet H, Bousquet C, Durand G, et al. Reversible amiodarone-induced lung disease: HRCT findings. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(9):1697-1703.

20. Olson LK, Forrest JV, Friedman PJ, et al. Pneumonitis after amiodarone therapy. Radiology. 1984;150(2):327-330.

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of shortness of breath, a dry nonproductive cough, fatigue, hypoxia, and general malaise lasting for several months and worsening over a two-week period. She denied having fever, chills, hemoptysis, weight loss, headache, rashes, or joint pain. She reported sweats, decrease in appetite, wheezing, cough without sputum production, and slight swelling of the legs. The patient complained of chest pain upon admission, but it resolved quickly.

The patient, a retired widow with five grown children, denied recent surgery or exposure to sick people, had not travelled, and reported no changes in her home environment. She claimed to have no pets but admitted to currently smoking about four cigarettes a day; she had previously smoked, on average, three packs of cigarettes per day for 60 years. She denied using alcohol or drugs, including intravenous agents.

The patient’s medical history was significant for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. She had also been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), transient ischemic attack, patent foramen ovale, hyperlipidemia, seizure disorder, and hypothyroidism. She had no known HIV risk factors and had had no exposure to asbestos or tuberculosis.

The patient’s current medications included amiodarone (200 mg/d) for four years; valproic acid (500 mg/d); aspirin (325 mg/d); levothyroxine (50 g/d); rosuvastatin (10 mg/d); daily warfarin, dosed according to the international normalized ratio (INR); and budesonide/formoterol (160/4.5 mg, one puff bid). She denied having any drug allergies.

Physical examination in the ED revealed a pulse of 63 beats/min; blood pressure, 108/50 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 16 to 20 breaths/min. The patient’s O2 saturation was 84% on room air; 82% to 84% on 4 L to 6 L of supplemental oxygen; 87% to 92% with a venturi mask; and 95% on biphasic positive airway pressure (BiPAP) device. She was afebrile with hypoxia and able to speak in full sentences. Crackles were detected in the upper lung fields, best heard anteriorly, as well as a few scattered wheezes and rhonchi. Her heart sounds were normal with a regular rhythm; her extremities exhibited trace edema bilaterally. The remainder of the physical exam was normal.

The patient’s laboratory values included a normal white blood cell (WBC) count, elevated lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) at 448 IU/L (reference range, 84 to 246 IU/L), and no eosinophils. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was not measured on admission. Blood analysis of her N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was 4,877 pg/mL; for women older than 75, a level higher than 1,800 pg/mL is abnormal.

A chest x-ray was performed on admission, showing hyperinflation of the lungs with mild coarsening of the lung markings. A bandlike area of opacity in the right lower lobe with bilateral apical pleural thickening was noted (see Figure 1). Noncontrast CT of the chest revealed diffuse upper lobe ground glass opacities in both lungs, extending into the right middle lobe and lingula as well the superior segments of the lower lobes, with areas of emphysema and septal thickening. Numerous nodules, some of which appeared cavitary, were apparent in the lower lobes.

A two-dimensional echocardiogram demonstrated normal left ventricular size and systolic function, mild tricuspid regurgitation without evidence of pulmonary hypertension, and mild left atrial enlargement.

The patient was admitted to the cardiac unit for evaluation. While there, she received one dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg IV), three doses of ipratropium bromide/albuterol, one dose of ceftriaxone (1 g IV), and one dose of azithromycin (500 mg po). In the absence of significant leg edema and an elevation of jugular venous distention with a normal two-dimensional echocardiogram, heart failure was ruled out. The chest pains reported on initial presentation were ultimately felt to be noncardiac in nature.

After the patient was transferred to the medical floor with an initial diagnosis of exacerbation of her COPD, she was treated with antibiotics, nebulizers, and corticosteroids. She continued to experience episodes of O2 desaturation while on 4 L to 6 L of oxygen via nasal cannula and on a venturi mask. She was then placed on a BiPAP device, set to 12/5, and 50% Fio2 (fraction of inspired oxygen), which improved her oxygenation.

Her hypoxia prompted further radiographic studies. The resulting chest CT scan showed ground glass opacities located primarily in the upper lung areas, greater on the right than on the left side (see Figure 2). The radiologist suggested that the hypoxia was caused by an infection, but because the patient’s presenting symptoms were chronic in nature, drug-induced causes were considered as well. Amiodarone was discontinued.

Cardiology was consulted and agreed that stopping amiodarone was acceptable since the patient was in sinus rhythm at the time. The patient continued to take antibiotics and prednisone. Her symptoms slowly improved during hospitalization, and she required less oxygen. Based on the patient’s presentation, physical exam findings, imaging studies, and laboratory findings, amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity (APT) was diagnosed.

She was discharged home on supplemental oxygen at 4 L via cannula, a tapering dosage of prednisone, and metered-dose inhalers for fluticasone/salmeterol and tiotropium bromide. She also had outpatient appointments scheduled, one with the pulmonologist to follow up on her imaging studies and to manage the prednisone taper and the other with the cardiologist to manage her atrial fibrillation.

At pulmonology two months later, she had a chest x-ray (see Figure 3) and pulmonary function tests (PFTs). The patient reported feeling progressively better in the past month. Her dyspnea on exertion had improved, and she did not require supplemental oxygen anymore. She stopped smoking cigarettes.

The patient continued to use fluticasone/salmeterol but stopped tiotropium bromide. On physical exam, her O2 saturation was 95% on room air, heart rhythm and rate were regular, and her lungs revealed very minimal crackles at the right base but were otherwise clear.

The plan specified continuing the prednisone taper. The patient was asked to call the office if she had any worsening shortness of breath, cough, and sputum production. She was also encouraged to continue refraining from smoking cigarettes. This patient had done very well, with near complete resolution of symptoms and a clear chest x-ray.

Continue reading for discussion...

DISCUSSION

Amiodarone, a highly effective antiarrhythmic drug, is FDA approved for suppressing ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. It is also used off-label as a second- or third-line choice for atrial fibrillation.1

Standard of care requires that, prior to starting amiodarone therapy, patients have a baseline chest x-ray and PFTs with diffusing capacity performed. Thereafter, the patient should be monitored with annual chest x-rays, with one performed promptly if new symptoms develop. Serial PFTs have not offered any benefit for monitoring, but a decrease of more than 15% in total lung capacity or more than 20% in diffusing capacity from baseline is consistent with APT.2

Adverse effects, both cardiac and noncardiac, are common with amiodarone therapy. They include proarrhythmias, bradycardia, and heart block, as well as thyroid and liver dysfunctions; dermatologic conditions such as blue-gray discoloration of the skin and photosensitivity; neurologic effects such as ataxia, paresthesias, and tremor; ocular problems, including corneal microdeposits; gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, anorexia, and constipation; and lung problems such as pulmonary toxicity, pleural effusion, and pleural thickening.3-6 Of these, pulmonary toxicity is the most severe and life threatening.7

APT, also known as amiodarone pneumonitis and amiodarone lung, typically manifests from a few months to a year and a half after treatment is commenced.6 APT can occur even after the drug is discontinued, because amiodarone has a very long elimination half-life of approximately 15 to 45 days and a tendency to concentrate in organs with high blood perfusion and in adipose tissues.8 Patients taking 400 mg/d for two months or longer or 200 mg/d for more than two years are considered at higher risk for APT.9 The severity of disease appears to correlate with the cumulative dose and length of treatment.10

Numerous risk factors for pulmonary toxicity have been reported, including high drug dosage, pre-existing lung disease, patient age, and prior surgery (see Table 1).11 According to an analysis of a database of 237 patients, only age and duration of amiodarone therapy were significant risk factors for APT.9 Its incidence is not precisely known; reported rates range from 1% to 17%.6,12,13

Presentation with such nonspecific symptoms as shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, fatigue, hypoxia, and general malaise is typical for many pulmonary and cardiac illnesses (see Table 2), making APT difficult to diagnose.14 Occasionally, rapid onset with progression to pneumonitis and respiratory failure masquerades as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).15

Notable, however, is that APT can manifest with nonproductive cough and dyspnea in 50% to 75% of cases. In addition, presenting symptoms will include fever (33% to 50% of cases) with associated malaise, fatigue, chest pain, and weight loss. In patients with APT, the physical exam usually reveals bilateral crackles on inspiration, but diffuse rales may be heard as well.11

Laboratory studies are not very helpful in diagnosing APT. Patients may present with nonspecific elevated WBCs without eosinophilia and an elevated LDH level.11 An elevated ESR may be detected before symptoms of APT manifest and can be present at the time of diagnosis.6

Imaging studies are far more helpful and specific in diagnosing APT. The typical chest x-ray shows bilateral patchy diffuse infiltrates.12 CT of the chest is usually more revealing, demonstrating ground glass opacities in the periphery and subpleural thickening, especially where infiltrates are denser. This thickening may result in pleuritic chest pain.6

The right upper lobe is more often affected in these cases than the left lung.6 Numerous pulmonary nodules in the upper lobes are found rarely and can be confused with lung cancer. These nodules are likely the result of an accumulation of the drug in areas of previous inflammation; a lung mass should prompt the addition of APT in the differential.2,16

APT is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring clinical suspicion, drug history, imaging, and consideration of the differential. The presence of three or more clinical factors supports a diagnosis of APT (see Table 3).11

Once APT is recognized, the first action is to have the patient stop taking amiodarone, followed by the administration of corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 40 to 60 mg/d11) for four to 12 months.17 Patients, especially those with underlying lung disease, will typically require temporary oxygen supplementation until hypoxia resolves. Even after the drug has been discontinued, some patients experience worsening symptoms before they see improvement simply because the drug can persist in lung tissue for up to a year following cessation of therapy.6

If APT is diagnosed early, the prognosis is favorable. In one study, a significant number of APT patients stabilized or improved after withdrawal of the drug, regardless of concurrent treatment with corticosteroids.18 Follow-up studies, both imaging and PFT, indicate complete clearing of lung opacities in the majority of patients treated for APT.19 Radiologic improvement may be seen six months after cessation of amiodarone.20 Patients who develop ARDS tend to do poorly and have a mortality rate of approximately 50%.11

Continue reading for the conclusion...

CONCLUSION

Among patients who are taking long-term or high-dose amiodarone, particularly those older than 60, new-onset nonproductive cough and dyspnea signal the need for pulmonary and cardiac work-up. Once the diagnosis of APT is made, treatment is straightforward: Withdraw the amiodarone, and initiate corticosteroid therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Fuster V, Rydén LE, Asinger RW, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation); North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Circulation. 2001; 104(17):2118-2150.

2. Jarand J, Lee A, Leigh R. Amiodaronoma: an unusual form of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. CMAJ. 2007;176(10):1411-1413.

3. Connolly S. Evidence-based analysis of amiodarone efficacy and safety. Circulation. 1999;100:2025-2034.

4. Amiodarone Trials Meta-Analysis Investigators. Effect of prophylactic amiodarone on mortality after acute myocardial infarction and in congestive heart failure: meta-analysis of individual data from 6500 patients in randomised trials. Lancet. 1997;350(9089):1417-1424.

5. Pollak PT. Clinical organ toxicity of antiarrhythmic compounds: ocular and pulmonary manifestations. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(9A):37R-45R.

6. Camus P, Martin W, Rosenow E. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25(1):65-75.

7. Rady MY, Ryan T, Starr NJ. Preoperative therapy with amiodarone and the incidence of acute organ dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(3):489-497.

8. Canada A, Lesko L, Haffajee C, et al. Amiodarone for tachyarrhythmias: kinetics, and efficacy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1983;17(2):100-104.

9. Ernawati DK, Stafford L, Hughes JD. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):82-87.

10. Liu FL, Cohen RD, Downar E, et al. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity: functional and ultrastructural evaluation. Thorax. 1986;41(2):100-105.

11. Chan E, King TE. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. UpToDate. 2013. www.uptodate.com/contents/amiodarone-pulmonary-toxicity. Accessed January 17, 2014.

12. Wolkove N, Baltzan M. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Can Respir J. 2009;16(2):43-48.

13. Jackevicius CA, Tom A, Essebag V, et al. Population-level incidence and risk factors for pulmonary toxicity associated with amiodarone. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:705-710.

14. Jessurun G, Crijns H. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity [editorial]. BMJ. 1997;314(7081):619-620.

15. Nacca N, Castigliano B, Yuhico L, et al. Severe amiodarone induced pulmonary toxicity. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(6):667-670.

16. Arnon R, Raz I, Chajek-Shaul T, et al. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity presenting as a solitary lung mass. Chest. 1988;93(2):425-427.

17. Yamada Y, Shiga T, Matsuda N, et al. Incidence and predictors of pulmonary toxicity in Japanese patients receiving low-dose amiodarone. Circ J. 2007;71(10):1610-1616.

18. Coudert B, Bailly F, Lombard JN, et al. Amiodarone pneumonitis: bronchoalveolar lavage findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. Chest. 1992;102(4):1005-1012.

19. Vernhet H, Bousquet C, Durand G, et al. Reversible amiodarone-induced lung disease: HRCT findings. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(9):1697-1703.

20. Olson LK, Forrest JV, Friedman PJ, et al. Pneumonitis after amiodarone therapy. Radiology. 1984;150(2):327-330.

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of shortness of breath, a dry nonproductive cough, fatigue, hypoxia, and general malaise lasting for several months and worsening over a two-week period. She denied having fever, chills, hemoptysis, weight loss, headache, rashes, or joint pain. She reported sweats, decrease in appetite, wheezing, cough without sputum production, and slight swelling of the legs. The patient complained of chest pain upon admission, but it resolved quickly.

The patient, a retired widow with five grown children, denied recent surgery or exposure to sick people, had not travelled, and reported no changes in her home environment. She claimed to have no pets but admitted to currently smoking about four cigarettes a day; she had previously smoked, on average, three packs of cigarettes per day for 60 years. She denied using alcohol or drugs, including intravenous agents.

The patient’s medical history was significant for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. She had also been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), transient ischemic attack, patent foramen ovale, hyperlipidemia, seizure disorder, and hypothyroidism. She had no known HIV risk factors and had had no exposure to asbestos or tuberculosis.

The patient’s current medications included amiodarone (200 mg/d) for four years; valproic acid (500 mg/d); aspirin (325 mg/d); levothyroxine (50 g/d); rosuvastatin (10 mg/d); daily warfarin, dosed according to the international normalized ratio (INR); and budesonide/formoterol (160/4.5 mg, one puff bid). She denied having any drug allergies.

Physical examination in the ED revealed a pulse of 63 beats/min; blood pressure, 108/50 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 16 to 20 breaths/min. The patient’s O2 saturation was 84% on room air; 82% to 84% on 4 L to 6 L of supplemental oxygen; 87% to 92% with a venturi mask; and 95% on biphasic positive airway pressure (BiPAP) device. She was afebrile with hypoxia and able to speak in full sentences. Crackles were detected in the upper lung fields, best heard anteriorly, as well as a few scattered wheezes and rhonchi. Her heart sounds were normal with a regular rhythm; her extremities exhibited trace edema bilaterally. The remainder of the physical exam was normal.

The patient’s laboratory values included a normal white blood cell (WBC) count, elevated lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) at 448 IU/L (reference range, 84 to 246 IU/L), and no eosinophils. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was not measured on admission. Blood analysis of her N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was 4,877 pg/mL; for women older than 75, a level higher than 1,800 pg/mL is abnormal.

A chest x-ray was performed on admission, showing hyperinflation of the lungs with mild coarsening of the lung markings. A bandlike area of opacity in the right lower lobe with bilateral apical pleural thickening was noted (see Figure 1). Noncontrast CT of the chest revealed diffuse upper lobe ground glass opacities in both lungs, extending into the right middle lobe and lingula as well the superior segments of the lower lobes, with areas of emphysema and septal thickening. Numerous nodules, some of which appeared cavitary, were apparent in the lower lobes.

A two-dimensional echocardiogram demonstrated normal left ventricular size and systolic function, mild tricuspid regurgitation without evidence of pulmonary hypertension, and mild left atrial enlargement.

The patient was admitted to the cardiac unit for evaluation. While there, she received one dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg IV), three doses of ipratropium bromide/albuterol, one dose of ceftriaxone (1 g IV), and one dose of azithromycin (500 mg po). In the absence of significant leg edema and an elevation of jugular venous distention with a normal two-dimensional echocardiogram, heart failure was ruled out. The chest pains reported on initial presentation were ultimately felt to be noncardiac in nature.

After the patient was transferred to the medical floor with an initial diagnosis of exacerbation of her COPD, she was treated with antibiotics, nebulizers, and corticosteroids. She continued to experience episodes of O2 desaturation while on 4 L to 6 L of oxygen via nasal cannula and on a venturi mask. She was then placed on a BiPAP device, set to 12/5, and 50% Fio2 (fraction of inspired oxygen), which improved her oxygenation.

Her hypoxia prompted further radiographic studies. The resulting chest CT scan showed ground glass opacities located primarily in the upper lung areas, greater on the right than on the left side (see Figure 2). The radiologist suggested that the hypoxia was caused by an infection, but because the patient’s presenting symptoms were chronic in nature, drug-induced causes were considered as well. Amiodarone was discontinued.

Cardiology was consulted and agreed that stopping amiodarone was acceptable since the patient was in sinus rhythm at the time. The patient continued to take antibiotics and prednisone. Her symptoms slowly improved during hospitalization, and she required less oxygen. Based on the patient’s presentation, physical exam findings, imaging studies, and laboratory findings, amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity (APT) was diagnosed.

She was discharged home on supplemental oxygen at 4 L via cannula, a tapering dosage of prednisone, and metered-dose inhalers for fluticasone/salmeterol and tiotropium bromide. She also had outpatient appointments scheduled, one with the pulmonologist to follow up on her imaging studies and to manage the prednisone taper and the other with the cardiologist to manage her atrial fibrillation.

At pulmonology two months later, she had a chest x-ray (see Figure 3) and pulmonary function tests (PFTs). The patient reported feeling progressively better in the past month. Her dyspnea on exertion had improved, and she did not require supplemental oxygen anymore. She stopped smoking cigarettes.

The patient continued to use fluticasone/salmeterol but stopped tiotropium bromide. On physical exam, her O2 saturation was 95% on room air, heart rhythm and rate were regular, and her lungs revealed very minimal crackles at the right base but were otherwise clear.

The plan specified continuing the prednisone taper. The patient was asked to call the office if she had any worsening shortness of breath, cough, and sputum production. She was also encouraged to continue refraining from smoking cigarettes. This patient had done very well, with near complete resolution of symptoms and a clear chest x-ray.

Continue reading for discussion...

DISCUSSION

Amiodarone, a highly effective antiarrhythmic drug, is FDA approved for suppressing ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. It is also used off-label as a second- or third-line choice for atrial fibrillation.1

Standard of care requires that, prior to starting amiodarone therapy, patients have a baseline chest x-ray and PFTs with diffusing capacity performed. Thereafter, the patient should be monitored with annual chest x-rays, with one performed promptly if new symptoms develop. Serial PFTs have not offered any benefit for monitoring, but a decrease of more than 15% in total lung capacity or more than 20% in diffusing capacity from baseline is consistent with APT.2

Adverse effects, both cardiac and noncardiac, are common with amiodarone therapy. They include proarrhythmias, bradycardia, and heart block, as well as thyroid and liver dysfunctions; dermatologic conditions such as blue-gray discoloration of the skin and photosensitivity; neurologic effects such as ataxia, paresthesias, and tremor; ocular problems, including corneal microdeposits; gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, anorexia, and constipation; and lung problems such as pulmonary toxicity, pleural effusion, and pleural thickening.3-6 Of these, pulmonary toxicity is the most severe and life threatening.7

APT, also known as amiodarone pneumonitis and amiodarone lung, typically manifests from a few months to a year and a half after treatment is commenced.6 APT can occur even after the drug is discontinued, because amiodarone has a very long elimination half-life of approximately 15 to 45 days and a tendency to concentrate in organs with high blood perfusion and in adipose tissues.8 Patients taking 400 mg/d for two months or longer or 200 mg/d for more than two years are considered at higher risk for APT.9 The severity of disease appears to correlate with the cumulative dose and length of treatment.10

Numerous risk factors for pulmonary toxicity have been reported, including high drug dosage, pre-existing lung disease, patient age, and prior surgery (see Table 1).11 According to an analysis of a database of 237 patients, only age and duration of amiodarone therapy were significant risk factors for APT.9 Its incidence is not precisely known; reported rates range from 1% to 17%.6,12,13

Presentation with such nonspecific symptoms as shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, fatigue, hypoxia, and general malaise is typical for many pulmonary and cardiac illnesses (see Table 2), making APT difficult to diagnose.14 Occasionally, rapid onset with progression to pneumonitis and respiratory failure masquerades as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).15

Notable, however, is that APT can manifest with nonproductive cough and dyspnea in 50% to 75% of cases. In addition, presenting symptoms will include fever (33% to 50% of cases) with associated malaise, fatigue, chest pain, and weight loss. In patients with APT, the physical exam usually reveals bilateral crackles on inspiration, but diffuse rales may be heard as well.11

Laboratory studies are not very helpful in diagnosing APT. Patients may present with nonspecific elevated WBCs without eosinophilia and an elevated LDH level.11 An elevated ESR may be detected before symptoms of APT manifest and can be present at the time of diagnosis.6

Imaging studies are far more helpful and specific in diagnosing APT. The typical chest x-ray shows bilateral patchy diffuse infiltrates.12 CT of the chest is usually more revealing, demonstrating ground glass opacities in the periphery and subpleural thickening, especially where infiltrates are denser. This thickening may result in pleuritic chest pain.6

The right upper lobe is more often affected in these cases than the left lung.6 Numerous pulmonary nodules in the upper lobes are found rarely and can be confused with lung cancer. These nodules are likely the result of an accumulation of the drug in areas of previous inflammation; a lung mass should prompt the addition of APT in the differential.2,16

APT is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring clinical suspicion, drug history, imaging, and consideration of the differential. The presence of three or more clinical factors supports a diagnosis of APT (see Table 3).11

Once APT is recognized, the first action is to have the patient stop taking amiodarone, followed by the administration of corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 40 to 60 mg/d11) for four to 12 months.17 Patients, especially those with underlying lung disease, will typically require temporary oxygen supplementation until hypoxia resolves. Even after the drug has been discontinued, some patients experience worsening symptoms before they see improvement simply because the drug can persist in lung tissue for up to a year following cessation of therapy.6

If APT is diagnosed early, the prognosis is favorable. In one study, a significant number of APT patients stabilized or improved after withdrawal of the drug, regardless of concurrent treatment with corticosteroids.18 Follow-up studies, both imaging and PFT, indicate complete clearing of lung opacities in the majority of patients treated for APT.19 Radiologic improvement may be seen six months after cessation of amiodarone.20 Patients who develop ARDS tend to do poorly and have a mortality rate of approximately 50%.11

Continue reading for the conclusion...

CONCLUSION

Among patients who are taking long-term or high-dose amiodarone, particularly those older than 60, new-onset nonproductive cough and dyspnea signal the need for pulmonary and cardiac work-up. Once the diagnosis of APT is made, treatment is straightforward: Withdraw the amiodarone, and initiate corticosteroid therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Fuster V, Rydén LE, Asinger RW, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation); North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Circulation. 2001; 104(17):2118-2150.

2. Jarand J, Lee A, Leigh R. Amiodaronoma: an unusual form of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. CMAJ. 2007;176(10):1411-1413.

3. Connolly S. Evidence-based analysis of amiodarone efficacy and safety. Circulation. 1999;100:2025-2034.

4. Amiodarone Trials Meta-Analysis Investigators. Effect of prophylactic amiodarone on mortality after acute myocardial infarction and in congestive heart failure: meta-analysis of individual data from 6500 patients in randomised trials. Lancet. 1997;350(9089):1417-1424.

5. Pollak PT. Clinical organ toxicity of antiarrhythmic compounds: ocular and pulmonary manifestations. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(9A):37R-45R.

6. Camus P, Martin W, Rosenow E. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25(1):65-75.

7. Rady MY, Ryan T, Starr NJ. Preoperative therapy with amiodarone and the incidence of acute organ dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(3):489-497.

8. Canada A, Lesko L, Haffajee C, et al. Amiodarone for tachyarrhythmias: kinetics, and efficacy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1983;17(2):100-104.

9. Ernawati DK, Stafford L, Hughes JD. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):82-87.

10. Liu FL, Cohen RD, Downar E, et al. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity: functional and ultrastructural evaluation. Thorax. 1986;41(2):100-105.

11. Chan E, King TE. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. UpToDate. 2013. www.uptodate.com/contents/amiodarone-pulmonary-toxicity. Accessed January 17, 2014.

12. Wolkove N, Baltzan M. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Can Respir J. 2009;16(2):43-48.

13. Jackevicius CA, Tom A, Essebag V, et al. Population-level incidence and risk factors for pulmonary toxicity associated with amiodarone. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:705-710.

14. Jessurun G, Crijns H. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity [editorial]. BMJ. 1997;314(7081):619-620.

15. Nacca N, Castigliano B, Yuhico L, et al. Severe amiodarone induced pulmonary toxicity. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(6):667-670.

16. Arnon R, Raz I, Chajek-Shaul T, et al. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity presenting as a solitary lung mass. Chest. 1988;93(2):425-427.

17. Yamada Y, Shiga T, Matsuda N, et al. Incidence and predictors of pulmonary toxicity in Japanese patients receiving low-dose amiodarone. Circ J. 2007;71(10):1610-1616.

18. Coudert B, Bailly F, Lombard JN, et al. Amiodarone pneumonitis: bronchoalveolar lavage findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. Chest. 1992;102(4):1005-1012.

19. Vernhet H, Bousquet C, Durand G, et al. Reversible amiodarone-induced lung disease: HRCT findings. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(9):1697-1703.

20. Olson LK, Forrest JV, Friedman PJ, et al. Pneumonitis after amiodarone therapy. Radiology. 1984;150(2):327-330.

Small AAA: To treat or not to treat

Once again our authorities choose to agree rather than disagree. Although there may be some minor differences in opinion, it appears that both suggest that careful observation is the preferred management for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. However, there may still be some controversy since I believe the data they use to support observation is confounded by including patients whose aneurysms were less than 5 cm. I think almost everyone would agree that it is safe to monitor the <5 cm AAA. But what about the 5.2 cm in a small woman or a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or a strong family history of rupture or, for that matter, in any patient? If you have an opinion one way or another I invite you to send your comments to info@vascularspecialistonline.com for inclusion in a future edition of Vascular Specialist. In the meantime if you go to www.Vascularspecialistonline.com you can respond to our "Online Question of the Month" about the treatment of these small AAA.

--Dr. Russell Samson is the medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Procedural risks remain an issue.

By Kenneth Ouriel, M.D.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are treated to prevent death from aneurysm rupture. Depending on the patient’s baseline medical status, however, the risks of the procedure itself may outweigh the risks of leaving the aneurysm untreated.1 Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), originally developed as a less invasive alternative to traditional open surgery,2 has incompletely addressed this issue. While prospective randomized clinical trials demonstrated reduction in early morbidity and mortality with EVAR, early benefits have not translated into long-term survival benefit over open surgical repair.3,4

Several studies have demonstrated improved results with EVAR when performed in patients with smaller aneurysms.5,6 This observation may relate to the frequency of more challenging anatomy in larger aneurysms, with a higher frequency of shorter, larger diameter, angulated, and conical proximal aortic necks. While the potential benefit of repair in patients with larger aneurysms is greatest with respect to the prevention of rupture, some of this benefit may be offset by poorer long-term outcome. These results are only in part a function of complications related to the device, such as proximal endoleaks and migration. In addition, patients with larger aneurysms are slightly older and sicker than those with smaller aneurysms, accounting for an increased frequency of non-aneurysm related events.

Noting the less challenging aortic anatomy and younger, healthier characteristics of the subpopulation with smaller AAA, two randomized studies were organized to compare the results of early endovascular repair versus ultrasound or computed tomographic (CT) surveillance.7 The PIVOTAL trial enrolled 728 subjects with AAA between 4 and 5 cm in diameter, randomizing to either early EVAR with the AneuRx or Talent endografts or to ultrasound/CT imaging studies every 6 months. The perioperative mortality rate was 0.6% in the early EVAR group. Over a mean follow-up period of 20 months, there were no differences in all-cause mortality between the two groups, each with 15 deaths (4.1%). The primary endpoint of rupture or aneurysm-related death was similar in the two groups, with a hazard ratio of 0.99 in the early EVAR group. However, at 36 months almost 50% of the surveillance group underwent aneurysm repair for sac enlargement, the development of aneurysm-related symptoms, or patient choice. Interestingly, a follow-up economic substudy documented similar health care costs in the two treatment groups at 48 months of follow-up, even though 36.3% of the surveyed patients did not undergo repair.

A second study, the CEASAR trial, randomized 360 patients with AAA 4.1-5.4 cm in diameter to early EVAR with the Cook Zenith device or to serial ultrasound surveillance. After 4.5 years of follow-up, no significant difference was detected in the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality. The Kaplan-Meier estimates of all-cause mortality was 14.5% in the early repair group versus 10.1% in the surveillance group. Aneurysm-related mortality, aneurysm rupture, and major morbidity rates were similar. Like the PIVOTAL trial, the majority of subjects underwent delayed repair, with a frequency of 60% at 3-years and 85% at 4.5 years.

The findings of these two randomized studies suggest that there is no survival advantage to early EVAR in patients with smaller AAA. With the increasing use of statins, ACE inhibitors, and better overall medical management in patients with AAA, the rate of aneurysm enlargement and risk of rupture are quite low in patients with small AAA.8 While survival benefits have not been demonstrated, however, there appear to be few quantifiable disadvantages to early repair. Moreover, the long-term financial impact to the healthcare system appears to be similar when patients are treated early compared to surveillance with serial imaging studies,9 and patient quality of life may be improved with early EVAR.10 These observations suggest that the repair of smaller AAA should be individualized, based upon the particular clinical presentation and the wishes of a patient. The summary of available data suggests that either approach protects a patient from rupture and surveillance culminates in the eventual repair of the aneurysm in the majority of patients.

Dr. Ouriel is a vascular surgeon and president and CEO of Syntactx.

References

1. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 55(5): p. 1263-7.

2. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2012. 23(7): p. 866-72; quiz 872.

3. J Endovasc Ther, 2012. 19(2): p. 182-92.

4. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 55(1): p. 33-40.

5. Ann Vasc Surg, 2012. 26(6): p. 860 e1-7.

6. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2013. 24(1): p. 49-55

7. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 56(3): p. 630-6.

8. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino), 2013. 1. Br J Surg 2007;94:702-8.

2. Semin Interv Cardiol 2000;5:3-6.

3. NEnglJMed 2010;362:1863-71.

4. JAMA 2009;302:1535-42.

5.. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1206-12.

6. J Vasc Surg 2006;44:920-29; discussion 9-31.

7. J Vasc Surg 2010;51:1081-7.

8. EurJVascEndovascSurg 2011;41:2-10.

9. J Vasc Surg 2013;58:302-10.

10. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41:324-31.

Small aneurysms should be left alone.

By Karl A. Illig, M.D.

The currently accepted recommendation to delay repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms until they reach 5-5.5 cm is based on the historical mortality and morbidity of open repair.1 Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) has clearly been shown to reduce the risk of operation, perhaps by as much as two-thirds. Should we now change the threshold for aneurysm repair, especially if the patient is a candidate for EVAR?

There are many arguments to repair small aneurysms. However, the answer really depends upon empirical data. At least three major papers address this question. In the U.K. Small Aneurysm Trial, 1,090 patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms measuring 4.0-5.5 cm in diameter were randomized to undergo early elective open surgery versus ultrasonic surveillance.2 There was an early survival disadvantage for those undergoing open surgery, as expected, but the curves evened out at 3 years or so, and no survival advantage occurred in either group, obviously favoring observation alone. Similarly, the ADAM group, pursuing the same protocol in 1,136 U.S. veterans, found the same thing, despite a low operative mortality of 2.7%. No advantage to early open repair could be seen.3

What of the situation after endovascular repair? The PIVOTAL trial, the lead author of which wrote the accompanying commentary, randomly assigned 728 patients with aneurysms measuring 4.0-5.0 cm to early endovascular repair with the Medtronic device versus ultrasonic surveillance.4 Aneurysm rupture or aneurysm-related death occurred in only two patients in each group (0.6%). The authors appropriately concluded that surveillance alone was equally as efficacious as early endovascular repair for patients with small aneurysms.

Finally, what of the arguments that, by waiting until the aneurysm is larger, you lose the window of opportunity for endovascular repair? We recently explored this in a cohort of 221 patients undergoing preoperative CT scanning for aneurysms of all sizes.5 With receiver operator curve analysis, a cutoff of 5.7 cm best differentiated those who were endovascular candidates from those who were not. Put another way, the rate of endovascular suitability hovered right around 80% until the aneurysm reached 6 cm, at which point it dropped off. In other words, waiting until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm doesn’t reduce the chance that a patient will be a candidate for EVAR.

There are many arguments for early intervention in small aneurysms. The concept that EVAR is safer than the procedure originally used to make the recommendation to wait until 5.5 cm is a valid point. However, empiric data still do not show any benefit for either open or endovascular repair as opposed to surveillance at sizes smaller than this. The operative mortality difference is only a couple of percentage points or so, and long-term survival appears to be identical after the initial risk has passed. This 2% or 3% early survival benefit does not seem to impart any long-term advantage, and long-term survival does not seem to be impaired by being a bit conservative. Until data come along that definitively show benefit for early repair, current guidelines remain valid.

Dr. Illig is the director of vascular surgery at USF Health, Tampa.

References:

1. J Vasc Surg 2009;50(8S):1S-49S.

2. Lancet 1998; 352:1649-55.

3. NEJM 2002; 346 (19): 1437-44.

4. J Vasc Surg 2010; 51:1081-7.

5. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:873-7.

Once again our authorities choose to agree rather than disagree. Although there may be some minor differences in opinion, it appears that both suggest that careful observation is the preferred management for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. However, there may still be some controversy since I believe the data they use to support observation is confounded by including patients whose aneurysms were less than 5 cm. I think almost everyone would agree that it is safe to monitor the <5 cm AAA. But what about the 5.2 cm in a small woman or a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or a strong family history of rupture or, for that matter, in any patient? If you have an opinion one way or another I invite you to send your comments to info@vascularspecialistonline.com for inclusion in a future edition of Vascular Specialist. In the meantime if you go to www.Vascularspecialistonline.com you can respond to our "Online Question of the Month" about the treatment of these small AAA.

--Dr. Russell Samson is the medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Procedural risks remain an issue.

By Kenneth Ouriel, M.D.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are treated to prevent death from aneurysm rupture. Depending on the patient’s baseline medical status, however, the risks of the procedure itself may outweigh the risks of leaving the aneurysm untreated.1 Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), originally developed as a less invasive alternative to traditional open surgery,2 has incompletely addressed this issue. While prospective randomized clinical trials demonstrated reduction in early morbidity and mortality with EVAR, early benefits have not translated into long-term survival benefit over open surgical repair.3,4

Several studies have demonstrated improved results with EVAR when performed in patients with smaller aneurysms.5,6 This observation may relate to the frequency of more challenging anatomy in larger aneurysms, with a higher frequency of shorter, larger diameter, angulated, and conical proximal aortic necks. While the potential benefit of repair in patients with larger aneurysms is greatest with respect to the prevention of rupture, some of this benefit may be offset by poorer long-term outcome. These results are only in part a function of complications related to the device, such as proximal endoleaks and migration. In addition, patients with larger aneurysms are slightly older and sicker than those with smaller aneurysms, accounting for an increased frequency of non-aneurysm related events.

Noting the less challenging aortic anatomy and younger, healthier characteristics of the subpopulation with smaller AAA, two randomized studies were organized to compare the results of early endovascular repair versus ultrasound or computed tomographic (CT) surveillance.7 The PIVOTAL trial enrolled 728 subjects with AAA between 4 and 5 cm in diameter, randomizing to either early EVAR with the AneuRx or Talent endografts or to ultrasound/CT imaging studies every 6 months. The perioperative mortality rate was 0.6% in the early EVAR group. Over a mean follow-up period of 20 months, there were no differences in all-cause mortality between the two groups, each with 15 deaths (4.1%). The primary endpoint of rupture or aneurysm-related death was similar in the two groups, with a hazard ratio of 0.99 in the early EVAR group. However, at 36 months almost 50% of the surveillance group underwent aneurysm repair for sac enlargement, the development of aneurysm-related symptoms, or patient choice. Interestingly, a follow-up economic substudy documented similar health care costs in the two treatment groups at 48 months of follow-up, even though 36.3% of the surveyed patients did not undergo repair.

A second study, the CEASAR trial, randomized 360 patients with AAA 4.1-5.4 cm in diameter to early EVAR with the Cook Zenith device or to serial ultrasound surveillance. After 4.5 years of follow-up, no significant difference was detected in the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality. The Kaplan-Meier estimates of all-cause mortality was 14.5% in the early repair group versus 10.1% in the surveillance group. Aneurysm-related mortality, aneurysm rupture, and major morbidity rates were similar. Like the PIVOTAL trial, the majority of subjects underwent delayed repair, with a frequency of 60% at 3-years and 85% at 4.5 years.

The findings of these two randomized studies suggest that there is no survival advantage to early EVAR in patients with smaller AAA. With the increasing use of statins, ACE inhibitors, and better overall medical management in patients with AAA, the rate of aneurysm enlargement and risk of rupture are quite low in patients with small AAA.8 While survival benefits have not been demonstrated, however, there appear to be few quantifiable disadvantages to early repair. Moreover, the long-term financial impact to the healthcare system appears to be similar when patients are treated early compared to surveillance with serial imaging studies,9 and patient quality of life may be improved with early EVAR.10 These observations suggest that the repair of smaller AAA should be individualized, based upon the particular clinical presentation and the wishes of a patient. The summary of available data suggests that either approach protects a patient from rupture and surveillance culminates in the eventual repair of the aneurysm in the majority of patients.

Dr. Ouriel is a vascular surgeon and president and CEO of Syntactx.

References

1. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 55(5): p. 1263-7.

2. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2012. 23(7): p. 866-72; quiz 872.

3. J Endovasc Ther, 2012. 19(2): p. 182-92.

4. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 55(1): p. 33-40.

5. Ann Vasc Surg, 2012. 26(6): p. 860 e1-7.

6. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2013. 24(1): p. 49-55

7. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 56(3): p. 630-6.

8. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino), 2013. 1. Br J Surg 2007;94:702-8.

2. Semin Interv Cardiol 2000;5:3-6.

3. NEnglJMed 2010;362:1863-71.

4. JAMA 2009;302:1535-42.

5.. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1206-12.

6. J Vasc Surg 2006;44:920-29; discussion 9-31.

7. J Vasc Surg 2010;51:1081-7.

8. EurJVascEndovascSurg 2011;41:2-10.

9. J Vasc Surg 2013;58:302-10.

10. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41:324-31.

Small aneurysms should be left alone.

By Karl A. Illig, M.D.

The currently accepted recommendation to delay repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms until they reach 5-5.5 cm is based on the historical mortality and morbidity of open repair.1 Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) has clearly been shown to reduce the risk of operation, perhaps by as much as two-thirds. Should we now change the threshold for aneurysm repair, especially if the patient is a candidate for EVAR?

There are many arguments to repair small aneurysms. However, the answer really depends upon empirical data. At least three major papers address this question. In the U.K. Small Aneurysm Trial, 1,090 patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms measuring 4.0-5.5 cm in diameter were randomized to undergo early elective open surgery versus ultrasonic surveillance.2 There was an early survival disadvantage for those undergoing open surgery, as expected, but the curves evened out at 3 years or so, and no survival advantage occurred in either group, obviously favoring observation alone. Similarly, the ADAM group, pursuing the same protocol in 1,136 U.S. veterans, found the same thing, despite a low operative mortality of 2.7%. No advantage to early open repair could be seen.3

What of the situation after endovascular repair? The PIVOTAL trial, the lead author of which wrote the accompanying commentary, randomly assigned 728 patients with aneurysms measuring 4.0-5.0 cm to early endovascular repair with the Medtronic device versus ultrasonic surveillance.4 Aneurysm rupture or aneurysm-related death occurred in only two patients in each group (0.6%). The authors appropriately concluded that surveillance alone was equally as efficacious as early endovascular repair for patients with small aneurysms.

Finally, what of the arguments that, by waiting until the aneurysm is larger, you lose the window of opportunity for endovascular repair? We recently explored this in a cohort of 221 patients undergoing preoperative CT scanning for aneurysms of all sizes.5 With receiver operator curve analysis, a cutoff of 5.7 cm best differentiated those who were endovascular candidates from those who were not. Put another way, the rate of endovascular suitability hovered right around 80% until the aneurysm reached 6 cm, at which point it dropped off. In other words, waiting until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm doesn’t reduce the chance that a patient will be a candidate for EVAR.

There are many arguments for early intervention in small aneurysms. The concept that EVAR is safer than the procedure originally used to make the recommendation to wait until 5.5 cm is a valid point. However, empiric data still do not show any benefit for either open or endovascular repair as opposed to surveillance at sizes smaller than this. The operative mortality difference is only a couple of percentage points or so, and long-term survival appears to be identical after the initial risk has passed. This 2% or 3% early survival benefit does not seem to impart any long-term advantage, and long-term survival does not seem to be impaired by being a bit conservative. Until data come along that definitively show benefit for early repair, current guidelines remain valid.

Dr. Illig is the director of vascular surgery at USF Health, Tampa.

References:

1. J Vasc Surg 2009;50(8S):1S-49S.

2. Lancet 1998; 352:1649-55.

3. NEJM 2002; 346 (19): 1437-44.

4. J Vasc Surg 2010; 51:1081-7.

5. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:873-7.

Once again our authorities choose to agree rather than disagree. Although there may be some minor differences in opinion, it appears that both suggest that careful observation is the preferred management for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. However, there may still be some controversy since I believe the data they use to support observation is confounded by including patients whose aneurysms were less than 5 cm. I think almost everyone would agree that it is safe to monitor the <5 cm AAA. But what about the 5.2 cm in a small woman or a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or a strong family history of rupture or, for that matter, in any patient? If you have an opinion one way or another I invite you to send your comments to info@vascularspecialistonline.com for inclusion in a future edition of Vascular Specialist. In the meantime if you go to www.Vascularspecialistonline.com you can respond to our "Online Question of the Month" about the treatment of these small AAA.

--Dr. Russell Samson is the medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Procedural risks remain an issue.

By Kenneth Ouriel, M.D.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are treated to prevent death from aneurysm rupture. Depending on the patient’s baseline medical status, however, the risks of the procedure itself may outweigh the risks of leaving the aneurysm untreated.1 Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), originally developed as a less invasive alternative to traditional open surgery,2 has incompletely addressed this issue. While prospective randomized clinical trials demonstrated reduction in early morbidity and mortality with EVAR, early benefits have not translated into long-term survival benefit over open surgical repair.3,4

Several studies have demonstrated improved results with EVAR when performed in patients with smaller aneurysms.5,6 This observation may relate to the frequency of more challenging anatomy in larger aneurysms, with a higher frequency of shorter, larger diameter, angulated, and conical proximal aortic necks. While the potential benefit of repair in patients with larger aneurysms is greatest with respect to the prevention of rupture, some of this benefit may be offset by poorer long-term outcome. These results are only in part a function of complications related to the device, such as proximal endoleaks and migration. In addition, patients with larger aneurysms are slightly older and sicker than those with smaller aneurysms, accounting for an increased frequency of non-aneurysm related events.

Noting the less challenging aortic anatomy and younger, healthier characteristics of the subpopulation with smaller AAA, two randomized studies were organized to compare the results of early endovascular repair versus ultrasound or computed tomographic (CT) surveillance.7 The PIVOTAL trial enrolled 728 subjects with AAA between 4 and 5 cm in diameter, randomizing to either early EVAR with the AneuRx or Talent endografts or to ultrasound/CT imaging studies every 6 months. The perioperative mortality rate was 0.6% in the early EVAR group. Over a mean follow-up period of 20 months, there were no differences in all-cause mortality between the two groups, each with 15 deaths (4.1%). The primary endpoint of rupture or aneurysm-related death was similar in the two groups, with a hazard ratio of 0.99 in the early EVAR group. However, at 36 months almost 50% of the surveillance group underwent aneurysm repair for sac enlargement, the development of aneurysm-related symptoms, or patient choice. Interestingly, a follow-up economic substudy documented similar health care costs in the two treatment groups at 48 months of follow-up, even though 36.3% of the surveyed patients did not undergo repair.

A second study, the CEASAR trial, randomized 360 patients with AAA 4.1-5.4 cm in diameter to early EVAR with the Cook Zenith device or to serial ultrasound surveillance. After 4.5 years of follow-up, no significant difference was detected in the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality. The Kaplan-Meier estimates of all-cause mortality was 14.5% in the early repair group versus 10.1% in the surveillance group. Aneurysm-related mortality, aneurysm rupture, and major morbidity rates were similar. Like the PIVOTAL trial, the majority of subjects underwent delayed repair, with a frequency of 60% at 3-years and 85% at 4.5 years.

The findings of these two randomized studies suggest that there is no survival advantage to early EVAR in patients with smaller AAA. With the increasing use of statins, ACE inhibitors, and better overall medical management in patients with AAA, the rate of aneurysm enlargement and risk of rupture are quite low in patients with small AAA.8 While survival benefits have not been demonstrated, however, there appear to be few quantifiable disadvantages to early repair. Moreover, the long-term financial impact to the healthcare system appears to be similar when patients are treated early compared to surveillance with serial imaging studies,9 and patient quality of life may be improved with early EVAR.10 These observations suggest that the repair of smaller AAA should be individualized, based upon the particular clinical presentation and the wishes of a patient. The summary of available data suggests that either approach protects a patient from rupture and surveillance culminates in the eventual repair of the aneurysm in the majority of patients.

Dr. Ouriel is a vascular surgeon and president and CEO of Syntactx.

References

1. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 55(5): p. 1263-7.

2. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2012. 23(7): p. 866-72; quiz 872.

3. J Endovasc Ther, 2012. 19(2): p. 182-92.

4. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 55(1): p. 33-40.

5. Ann Vasc Surg, 2012. 26(6): p. 860 e1-7.

6. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2013. 24(1): p. 49-55

7. J Vasc Surg, 2012. 56(3): p. 630-6.

8. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino), 2013. 1. Br J Surg 2007;94:702-8.

2. Semin Interv Cardiol 2000;5:3-6.

3. NEnglJMed 2010;362:1863-71.

4. JAMA 2009;302:1535-42.

5.. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1206-12.

6. J Vasc Surg 2006;44:920-29; discussion 9-31.

7. J Vasc Surg 2010;51:1081-7.

8. EurJVascEndovascSurg 2011;41:2-10.

9. J Vasc Surg 2013;58:302-10.

10. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41:324-31.

Small aneurysms should be left alone.

By Karl A. Illig, M.D.

The currently accepted recommendation to delay repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms until they reach 5-5.5 cm is based on the historical mortality and morbidity of open repair.1 Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) has clearly been shown to reduce the risk of operation, perhaps by as much as two-thirds. Should we now change the threshold for aneurysm repair, especially if the patient is a candidate for EVAR?

There are many arguments to repair small aneurysms. However, the answer really depends upon empirical data. At least three major papers address this question. In the U.K. Small Aneurysm Trial, 1,090 patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms measuring 4.0-5.5 cm in diameter were randomized to undergo early elective open surgery versus ultrasonic surveillance.2 There was an early survival disadvantage for those undergoing open surgery, as expected, but the curves evened out at 3 years or so, and no survival advantage occurred in either group, obviously favoring observation alone. Similarly, the ADAM group, pursuing the same protocol in 1,136 U.S. veterans, found the same thing, despite a low operative mortality of 2.7%. No advantage to early open repair could be seen.3

What of the situation after endovascular repair? The PIVOTAL trial, the lead author of which wrote the accompanying commentary, randomly assigned 728 patients with aneurysms measuring 4.0-5.0 cm to early endovascular repair with the Medtronic device versus ultrasonic surveillance.4 Aneurysm rupture or aneurysm-related death occurred in only two patients in each group (0.6%). The authors appropriately concluded that surveillance alone was equally as efficacious as early endovascular repair for patients with small aneurysms.

Finally, what of the arguments that, by waiting until the aneurysm is larger, you lose the window of opportunity for endovascular repair? We recently explored this in a cohort of 221 patients undergoing preoperative CT scanning for aneurysms of all sizes.5 With receiver operator curve analysis, a cutoff of 5.7 cm best differentiated those who were endovascular candidates from those who were not. Put another way, the rate of endovascular suitability hovered right around 80% until the aneurysm reached 6 cm, at which point it dropped off. In other words, waiting until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm doesn’t reduce the chance that a patient will be a candidate for EVAR.

There are many arguments for early intervention in small aneurysms. The concept that EVAR is safer than the procedure originally used to make the recommendation to wait until 5.5 cm is a valid point. However, empiric data still do not show any benefit for either open or endovascular repair as opposed to surveillance at sizes smaller than this. The operative mortality difference is only a couple of percentage points or so, and long-term survival appears to be identical after the initial risk has passed. This 2% or 3% early survival benefit does not seem to impart any long-term advantage, and long-term survival does not seem to be impaired by being a bit conservative. Until data come along that definitively show benefit for early repair, current guidelines remain valid.

Dr. Illig is the director of vascular surgery at USF Health, Tampa.

References:

1. J Vasc Surg 2009;50(8S):1S-49S.

2. Lancet 1998; 352:1649-55.

3. NEJM 2002; 346 (19): 1437-44.

4. J Vasc Surg 2010; 51:1081-7.

5. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:873-7.

Online Question of the Month

New and Noteworthy Information—February 2014

Alcohol consumption may reduce the risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) and attenuate the effect of smoking, according to research published online ahead of print January 6 in JAMA Neurology. Scientists examined data from the Epidemiological Investigation of MS (EIMS), which included 745 cases and 1,761 controls, and from the Genes and Environment in MS (GEMS) study, which recruited 5,874 cases and 5,246 controls. In EIMS, women who reported high alcohol consumption (>112 g/week) had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.6 of developing MS, compared with nondrinking women. Men with high alcohol consumption (>168 g/week) in EIMS had an OR of 0.5, compared with nondrinking men. The OR for the comparison in GEMS was 0.7 for women and 0.7 for men. In both studies, the detrimental effect of smoking was more pronounced among nondrinkers.

A lentiviral vector-based gene therapy may be safe and improve motor behavior in patients with Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published online ahead of print January 10 in Lancet. In a phase I–II open-label trial, 15 patients received bilateral injections of gene therapy into the putamen and were followed up for 12 months. Participants received a low dose (1.9 × 107 transducing units [TU]), medium dose (4.0 × 107 TU), or a high dose (1 × 108 TU) of gene therapy. Patients reported 51 mild adverse events, three moderate adverse events, and no serious adverse events. The investigators noted a significant improvement in mean Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III motor scores off medication in all patients at six months, compared with baseline.

The FDA has approved a three-times-per-week formulation of Copaxone 40 mg/mL. The new formulation will enable a less-frequent dosing regimen to be administered subcutaneously to patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). The approval is based on data from the Phase III Glatiramer Acetate Low-Frequency Administration study of more than 1,400 patients. In the trial, investigators found that a 40-mg/mL dose of Copaxone administered subcutaneously three times per week significantly reduced relapse rates at 12 months and demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. In addition to the newly approved dose, daily Copaxone 20 mg/mL will continue to be available. The daily subcutaneous injection was approved in 1996. Both formulations are manufactured by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, which is headquartered in Jerusalem.