User login

A Portrait of the Patient

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

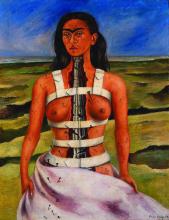

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

The Game We Play Every Day

Words do have power. Names have power. Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer ... They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it. — Ursula K. Le Guin

Every medical student should have a class in linguistics. I’m just unsure what it might replace. Maybe physiology? (When was the last time you used Fick’s or Fourier’s Laws anyway?). Even if we don’t supplant any core curriculum, it’s worth noting that we spend more time in our daily work calculating how to communicate things than calculating cardiac outputs. That we can convey so much so consistently and without specific training is a marvel. Making the diagnosis or a plan is often the easy part.

Linguistics is a broad field. At its essence, it studies how we communicate. It’s fascinating how we use tone, word choice, gestures, syntax, and grammar to explain, reassure, instruct or implore patients. Medical appointments are sometimes high stakes and occur within a huge variety of circumstances. In a single day of clinic, I had a patient with dementia, and one pursuing a PhD in P-Chem. I had English speakers, second language English speakers, and a Vietnamese patient who knew no English. In just one day, I explained things to toddlers and adults, a Black woman from Oklahoma and a Jewish woman from New York. For a brief few minutes, each of them was my partner in a game of medical charades. For each one, I had to figure out how to get them to know what I’m thinking.

I learned of this game of charades concept from a podcast featuring Morten Christiansen, professor of psychology at Cornell University, and professor in Cognitive Science of Language, at Aarhus University, Denmark. The idea is that language can be thought of as a game where speakers constantly improvise based on the topic, each one’s expertise, and the shared understanding. I found this intriguing. In his explanation, grammar and definitions are less important than the mutual understanding of what is being communicated. It helps explain the wide variations of speech even among those speaking the same language. It also flips the idea that brains are designed for language, a concept proposed by linguistic greats such as Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker. Rather, what we call language is just the best solution our brains could create to convey information.

I thought about how each of us instinctively varies the complexity of sentences and tone of voice based on the ability of each patient to understand. Gestures, storytelling and analogies are linguistic tools we use without thinking about them. We’ve a unique communications conundrum in that we often need patients to understand a complex idea, but only have minutes to get them there. We don’t want them to panic. We also don’t want them to be so dispassionate as to not act. To speed things up, we often use a technique known as chunking, short phrases that capture an idea in one bite. For example, “soak and smear” to get atopic patients to moisturize or “scrape and burn” to describe a curettage and electrodesiccation of a basal cell carcinoma or “a stick and a burn” before injecting them (I never liked that one). These are pithy, efficient. But they don’t always work.

One afternoon I had a 93-year-old woman with glossodynia. She had dementia and her 96-year-old husband was helping. When I explained how she’d “swish and spit” her magic mouthwash, he looked perplexed. Is she swishing a wand or something? I shook my head, “No” and gestured with my hands palms down, waving back and forth. It is just a mouthwash. She should rinse, then spit it out. I lost that round.

Then a 64-year-old woman whom I had to advise that the pink bump on her arm was a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor. Do I call it a Merkel cell carcinoma? Do I say, “You know, like the one Jimmy Buffett had?” (Nope, not a good use of storytelling). She wanted to know how she got it. Sun exposure, we think. Or, perhaps a virus. Just how does one explain a virus called MCPyV that is ubiquitous but somehow caused cancer just for you? How do you convey, “This is serious, but you might not die like Jimmy Buffett?” I had to use all my language skills to get this right.

Then there is the Henderson-Hasselbalch problem of linguistics: communicating through a translator. When doing so, I’m cognizant of choosing short, simple sentences. Subject, verb, object. First this, then that. This mitigates what’s lost in translation and reduces waiting for translations (especially when your patient is storytelling in paragraphs). But try doing this with an emotionally wrought condition like alopecia. Finding the fewest words to convey that your FSH and estrogen levels are irrelevant to your telogen effluvium to a Vietnamese speaker is tricky. “Yes, I see your primary care physician ordered these tests. No, the numbers do not matter.” Did that translate as they are normal? Or that they don’t matter because she is 54? Or that they don’t matter to me because I didn’t order them?

When you find yourself exhausted at the day’s end, perhaps you’ll better appreciate how it was not only the graduate level medicine you did today; you’ve practically got a PhD in linguistics as well. You just didn’t realize it.

Dr. Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Words do have power. Names have power. Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer ... They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it. — Ursula K. Le Guin

Every medical student should have a class in linguistics. I’m just unsure what it might replace. Maybe physiology? (When was the last time you used Fick’s or Fourier’s Laws anyway?). Even if we don’t supplant any core curriculum, it’s worth noting that we spend more time in our daily work calculating how to communicate things than calculating cardiac outputs. That we can convey so much so consistently and without specific training is a marvel. Making the diagnosis or a plan is often the easy part.

Linguistics is a broad field. At its essence, it studies how we communicate. It’s fascinating how we use tone, word choice, gestures, syntax, and grammar to explain, reassure, instruct or implore patients. Medical appointments are sometimes high stakes and occur within a huge variety of circumstances. In a single day of clinic, I had a patient with dementia, and one pursuing a PhD in P-Chem. I had English speakers, second language English speakers, and a Vietnamese patient who knew no English. In just one day, I explained things to toddlers and adults, a Black woman from Oklahoma and a Jewish woman from New York. For a brief few minutes, each of them was my partner in a game of medical charades. For each one, I had to figure out how to get them to know what I’m thinking.

I learned of this game of charades concept from a podcast featuring Morten Christiansen, professor of psychology at Cornell University, and professor in Cognitive Science of Language, at Aarhus University, Denmark. The idea is that language can be thought of as a game where speakers constantly improvise based on the topic, each one’s expertise, and the shared understanding. I found this intriguing. In his explanation, grammar and definitions are less important than the mutual understanding of what is being communicated. It helps explain the wide variations of speech even among those speaking the same language. It also flips the idea that brains are designed for language, a concept proposed by linguistic greats such as Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker. Rather, what we call language is just the best solution our brains could create to convey information.

I thought about how each of us instinctively varies the complexity of sentences and tone of voice based on the ability of each patient to understand. Gestures, storytelling and analogies are linguistic tools we use without thinking about them. We’ve a unique communications conundrum in that we often need patients to understand a complex idea, but only have minutes to get them there. We don’t want them to panic. We also don’t want them to be so dispassionate as to not act. To speed things up, we often use a technique known as chunking, short phrases that capture an idea in one bite. For example, “soak and smear” to get atopic patients to moisturize or “scrape and burn” to describe a curettage and electrodesiccation of a basal cell carcinoma or “a stick and a burn” before injecting them (I never liked that one). These are pithy, efficient. But they don’t always work.

One afternoon I had a 93-year-old woman with glossodynia. She had dementia and her 96-year-old husband was helping. When I explained how she’d “swish and spit” her magic mouthwash, he looked perplexed. Is she swishing a wand or something? I shook my head, “No” and gestured with my hands palms down, waving back and forth. It is just a mouthwash. She should rinse, then spit it out. I lost that round.

Then a 64-year-old woman whom I had to advise that the pink bump on her arm was a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor. Do I call it a Merkel cell carcinoma? Do I say, “You know, like the one Jimmy Buffett had?” (Nope, not a good use of storytelling). She wanted to know how she got it. Sun exposure, we think. Or, perhaps a virus. Just how does one explain a virus called MCPyV that is ubiquitous but somehow caused cancer just for you? How do you convey, “This is serious, but you might not die like Jimmy Buffett?” I had to use all my language skills to get this right.

Then there is the Henderson-Hasselbalch problem of linguistics: communicating through a translator. When doing so, I’m cognizant of choosing short, simple sentences. Subject, verb, object. First this, then that. This mitigates what’s lost in translation and reduces waiting for translations (especially when your patient is storytelling in paragraphs). But try doing this with an emotionally wrought condition like alopecia. Finding the fewest words to convey that your FSH and estrogen levels are irrelevant to your telogen effluvium to a Vietnamese speaker is tricky. “Yes, I see your primary care physician ordered these tests. No, the numbers do not matter.” Did that translate as they are normal? Or that they don’t matter because she is 54? Or that they don’t matter to me because I didn’t order them?

When you find yourself exhausted at the day’s end, perhaps you’ll better appreciate how it was not only the graduate level medicine you did today; you’ve practically got a PhD in linguistics as well. You just didn’t realize it.

Dr. Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Words do have power. Names have power. Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer ... They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it. — Ursula K. Le Guin

Every medical student should have a class in linguistics. I’m just unsure what it might replace. Maybe physiology? (When was the last time you used Fick’s or Fourier’s Laws anyway?). Even if we don’t supplant any core curriculum, it’s worth noting that we spend more time in our daily work calculating how to communicate things than calculating cardiac outputs. That we can convey so much so consistently and without specific training is a marvel. Making the diagnosis or a plan is often the easy part.

Linguistics is a broad field. At its essence, it studies how we communicate. It’s fascinating how we use tone, word choice, gestures, syntax, and grammar to explain, reassure, instruct or implore patients. Medical appointments are sometimes high stakes and occur within a huge variety of circumstances. In a single day of clinic, I had a patient with dementia, and one pursuing a PhD in P-Chem. I had English speakers, second language English speakers, and a Vietnamese patient who knew no English. In just one day, I explained things to toddlers and adults, a Black woman from Oklahoma and a Jewish woman from New York. For a brief few minutes, each of them was my partner in a game of medical charades. For each one, I had to figure out how to get them to know what I’m thinking.

I learned of this game of charades concept from a podcast featuring Morten Christiansen, professor of psychology at Cornell University, and professor in Cognitive Science of Language, at Aarhus University, Denmark. The idea is that language can be thought of as a game where speakers constantly improvise based on the topic, each one’s expertise, and the shared understanding. I found this intriguing. In his explanation, grammar and definitions are less important than the mutual understanding of what is being communicated. It helps explain the wide variations of speech even among those speaking the same language. It also flips the idea that brains are designed for language, a concept proposed by linguistic greats such as Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker. Rather, what we call language is just the best solution our brains could create to convey information.

I thought about how each of us instinctively varies the complexity of sentences and tone of voice based on the ability of each patient to understand. Gestures, storytelling and analogies are linguistic tools we use without thinking about them. We’ve a unique communications conundrum in that we often need patients to understand a complex idea, but only have minutes to get them there. We don’t want them to panic. We also don’t want them to be so dispassionate as to not act. To speed things up, we often use a technique known as chunking, short phrases that capture an idea in one bite. For example, “soak and smear” to get atopic patients to moisturize or “scrape and burn” to describe a curettage and electrodesiccation of a basal cell carcinoma or “a stick and a burn” before injecting them (I never liked that one). These are pithy, efficient. But they don’t always work.

One afternoon I had a 93-year-old woman with glossodynia. She had dementia and her 96-year-old husband was helping. When I explained how she’d “swish and spit” her magic mouthwash, he looked perplexed. Is she swishing a wand or something? I shook my head, “No” and gestured with my hands palms down, waving back and forth. It is just a mouthwash. She should rinse, then spit it out. I lost that round.

Then a 64-year-old woman whom I had to advise that the pink bump on her arm was a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor. Do I call it a Merkel cell carcinoma? Do I say, “You know, like the one Jimmy Buffett had?” (Nope, not a good use of storytelling). She wanted to know how she got it. Sun exposure, we think. Or, perhaps a virus. Just how does one explain a virus called MCPyV that is ubiquitous but somehow caused cancer just for you? How do you convey, “This is serious, but you might not die like Jimmy Buffett?” I had to use all my language skills to get this right.

Then there is the Henderson-Hasselbalch problem of linguistics: communicating through a translator. When doing so, I’m cognizant of choosing short, simple sentences. Subject, verb, object. First this, then that. This mitigates what’s lost in translation and reduces waiting for translations (especially when your patient is storytelling in paragraphs). But try doing this with an emotionally wrought condition like alopecia. Finding the fewest words to convey that your FSH and estrogen levels are irrelevant to your telogen effluvium to a Vietnamese speaker is tricky. “Yes, I see your primary care physician ordered these tests. No, the numbers do not matter.” Did that translate as they are normal? Or that they don’t matter because she is 54? Or that they don’t matter to me because I didn’t order them?

When you find yourself exhausted at the day’s end, perhaps you’ll better appreciate how it was not only the graduate level medicine you did today; you’ve practically got a PhD in linguistics as well. You just didn’t realize it.

Dr. Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Doing the Best They Can

Our dermatology department is composed of 25 doctors spread across 4 offices. It can be difficult to sustain cohesion so we have a few rituals to help hold us together. One is the morning huddle. This is a stand-up meeting lasting 3-5 minutes at 8:42 a.m. (just before the 8:45 a.m. patients). Led by our staff, huddle is a quick review of the priorities, issues, and celebrations across our department. While enthusiastically celebrating a staff member’s promotion one morning, a patient swung open the exam door and shouted, “What’s going on out here?! I’m sitting here waiting!” before slamming the door closed again. “Well, that was unnecessary,” our morning lead interjected as she went to reprimand him.

His behavior was easily recognizable to any doctor with children. It was an emotional outburst we call a tantrum. Although a graphic of tantrums by age would show a steep curve that drops precipitously after 4-years-old (please God, I hope), it persists throughout life. Even adults have tantrums. After? When I broke my pinky toe saving the family from flaming tornadoes a few weeks ago (I ran into the sofa), I flung the ice bag across the room in frustration. “You’ve a right to be mad,” my wife said returning the ice to where I was elevating my foot. She was spot on, it is understandable that I would be angry. It will be weeks before I can run again. And also my toe was broken. Both things were true.

“Two things are true” is a technique for managing tantrums in toddlers. I first learned of it from Dr. Becky Kennedy, a clinical psychologist specializing in family therapy. She has a popular podcast called “Good Inside” based on her book of the same name. Her approach is to use positive psychology with an emphasis on connecting with children to not only shape behavior, but also to help them learn to manage their emotions. I read her book to level up dad skills and realized many of her principles are applicable to various types of relationships. Instead of viewing behaviors as an end, she instead recommends using them as an opportunity to probe for understanding. Assume they are doing the best they can. When my 4-year-old obstinately refused to go to bed despite the usual colored night lights and bedtime rituals, it seemed she was being a typical tantrum-y toddler. The more I insisted — lights-out! the more she resisted. It wasn’t until I asked why that I learned she was worried that the trash truck was going to come overnight. What seemed like just a behavioral problem, time for bed, was actually an opportunity for her to be seen and for us to connect.

I was finishing up with a patient last week when my medical assistant interrupted to advise my next patient was leaving. I walked out to see her storm into the corridor heading for the exit. “I am sorry, you must be quite frustrated having to wait for me.” “Yes, you don’t respect my time,” she said loudly enough for everyone pretending to not notice. I coaxed her back into the room and sat down. After apologizing for her wait and explaining it was because an urgent patient had been added to my schedule, she calmed down and allowed me to continue. At her previous visit, I had biopsied a firm dermal papule on her upper abdomen that turned out to be metastatic breast cancer. She was treated years ago and believed she was in complete remission. Now she was alone, terrified, and wanted her full appointment with me. Because I was running late, she assumed I wouldn’t have the time for her. It was an opportunity for me to connect with her and help her feel safe. I would have missed that opportunity if I had labeled her as just another angry “Karen” brassly asserting herself.

Dr. Kennedy talks a lot in her book about taking the “Most generous interpretation” of whatever behavioral issue arises. Take the time to validate what they are feeling and empathize as best as we can. Acknowledge that it’s normal to be angry and also these are the truths we have to work with. Two truths commonly appear in these emotional episodes. One, the immutable facts, for example, insurance doesn’t cover that drug, and two, your right to be frustrated by that. Above all, remember you, the doctor, are good inside as is your discourteous patient, disaffected staff member or sometimes mendacious teenager. “All good decisions start with feeling secure and nothing feels more secure than being recognized for the good people we are,” says Dr. Kennedy. True I believe even if we sometimes slam the door.

Dr. Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Our dermatology department is composed of 25 doctors spread across 4 offices. It can be difficult to sustain cohesion so we have a few rituals to help hold us together. One is the morning huddle. This is a stand-up meeting lasting 3-5 minutes at 8:42 a.m. (just before the 8:45 a.m. patients). Led by our staff, huddle is a quick review of the priorities, issues, and celebrations across our department. While enthusiastically celebrating a staff member’s promotion one morning, a patient swung open the exam door and shouted, “What’s going on out here?! I’m sitting here waiting!” before slamming the door closed again. “Well, that was unnecessary,” our morning lead interjected as she went to reprimand him.

His behavior was easily recognizable to any doctor with children. It was an emotional outburst we call a tantrum. Although a graphic of tantrums by age would show a steep curve that drops precipitously after 4-years-old (please God, I hope), it persists throughout life. Even adults have tantrums. After? When I broke my pinky toe saving the family from flaming tornadoes a few weeks ago (I ran into the sofa), I flung the ice bag across the room in frustration. “You’ve a right to be mad,” my wife said returning the ice to where I was elevating my foot. She was spot on, it is understandable that I would be angry. It will be weeks before I can run again. And also my toe was broken. Both things were true.

“Two things are true” is a technique for managing tantrums in toddlers. I first learned of it from Dr. Becky Kennedy, a clinical psychologist specializing in family therapy. She has a popular podcast called “Good Inside” based on her book of the same name. Her approach is to use positive psychology with an emphasis on connecting with children to not only shape behavior, but also to help them learn to manage their emotions. I read her book to level up dad skills and realized many of her principles are applicable to various types of relationships. Instead of viewing behaviors as an end, she instead recommends using them as an opportunity to probe for understanding. Assume they are doing the best they can. When my 4-year-old obstinately refused to go to bed despite the usual colored night lights and bedtime rituals, it seemed she was being a typical tantrum-y toddler. The more I insisted — lights-out! the more she resisted. It wasn’t until I asked why that I learned she was worried that the trash truck was going to come overnight. What seemed like just a behavioral problem, time for bed, was actually an opportunity for her to be seen and for us to connect.

I was finishing up with a patient last week when my medical assistant interrupted to advise my next patient was leaving. I walked out to see her storm into the corridor heading for the exit. “I am sorry, you must be quite frustrated having to wait for me.” “Yes, you don’t respect my time,” she said loudly enough for everyone pretending to not notice. I coaxed her back into the room and sat down. After apologizing for her wait and explaining it was because an urgent patient had been added to my schedule, she calmed down and allowed me to continue. At her previous visit, I had biopsied a firm dermal papule on her upper abdomen that turned out to be metastatic breast cancer. She was treated years ago and believed she was in complete remission. Now she was alone, terrified, and wanted her full appointment with me. Because I was running late, she assumed I wouldn’t have the time for her. It was an opportunity for me to connect with her and help her feel safe. I would have missed that opportunity if I had labeled her as just another angry “Karen” brassly asserting herself.

Dr. Kennedy talks a lot in her book about taking the “Most generous interpretation” of whatever behavioral issue arises. Take the time to validate what they are feeling and empathize as best as we can. Acknowledge that it’s normal to be angry and also these are the truths we have to work with. Two truths commonly appear in these emotional episodes. One, the immutable facts, for example, insurance doesn’t cover that drug, and two, your right to be frustrated by that. Above all, remember you, the doctor, are good inside as is your discourteous patient, disaffected staff member or sometimes mendacious teenager. “All good decisions start with feeling secure and nothing feels more secure than being recognized for the good people we are,” says Dr. Kennedy. True I believe even if we sometimes slam the door.

Dr. Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Our dermatology department is composed of 25 doctors spread across 4 offices. It can be difficult to sustain cohesion so we have a few rituals to help hold us together. One is the morning huddle. This is a stand-up meeting lasting 3-5 minutes at 8:42 a.m. (just before the 8:45 a.m. patients). Led by our staff, huddle is a quick review of the priorities, issues, and celebrations across our department. While enthusiastically celebrating a staff member’s promotion one morning, a patient swung open the exam door and shouted, “What’s going on out here?! I’m sitting here waiting!” before slamming the door closed again. “Well, that was unnecessary,” our morning lead interjected as she went to reprimand him.

His behavior was easily recognizable to any doctor with children. It was an emotional outburst we call a tantrum. Although a graphic of tantrums by age would show a steep curve that drops precipitously after 4-years-old (please God, I hope), it persists throughout life. Even adults have tantrums. After? When I broke my pinky toe saving the family from flaming tornadoes a few weeks ago (I ran into the sofa), I flung the ice bag across the room in frustration. “You’ve a right to be mad,” my wife said returning the ice to where I was elevating my foot. She was spot on, it is understandable that I would be angry. It will be weeks before I can run again. And also my toe was broken. Both things were true.

“Two things are true” is a technique for managing tantrums in toddlers. I first learned of it from Dr. Becky Kennedy, a clinical psychologist specializing in family therapy. She has a popular podcast called “Good Inside” based on her book of the same name. Her approach is to use positive psychology with an emphasis on connecting with children to not only shape behavior, but also to help them learn to manage their emotions. I read her book to level up dad skills and realized many of her principles are applicable to various types of relationships. Instead of viewing behaviors as an end, she instead recommends using them as an opportunity to probe for understanding. Assume they are doing the best they can. When my 4-year-old obstinately refused to go to bed despite the usual colored night lights and bedtime rituals, it seemed she was being a typical tantrum-y toddler. The more I insisted — lights-out! the more she resisted. It wasn’t until I asked why that I learned she was worried that the trash truck was going to come overnight. What seemed like just a behavioral problem, time for bed, was actually an opportunity for her to be seen and for us to connect.

I was finishing up with a patient last week when my medical assistant interrupted to advise my next patient was leaving. I walked out to see her storm into the corridor heading for the exit. “I am sorry, you must be quite frustrated having to wait for me.” “Yes, you don’t respect my time,” she said loudly enough for everyone pretending to not notice. I coaxed her back into the room and sat down. After apologizing for her wait and explaining it was because an urgent patient had been added to my schedule, she calmed down and allowed me to continue. At her previous visit, I had biopsied a firm dermal papule on her upper abdomen that turned out to be metastatic breast cancer. She was treated years ago and believed she was in complete remission. Now she was alone, terrified, and wanted her full appointment with me. Because I was running late, she assumed I wouldn’t have the time for her. It was an opportunity for me to connect with her and help her feel safe. I would have missed that opportunity if I had labeled her as just another angry “Karen” brassly asserting herself.

Dr. Kennedy talks a lot in her book about taking the “Most generous interpretation” of whatever behavioral issue arises. Take the time to validate what they are feeling and empathize as best as we can. Acknowledge that it’s normal to be angry and also these are the truths we have to work with. Two truths commonly appear in these emotional episodes. One, the immutable facts, for example, insurance doesn’t cover that drug, and two, your right to be frustrated by that. Above all, remember you, the doctor, are good inside as is your discourteous patient, disaffected staff member or sometimes mendacious teenager. “All good decisions start with feeling secure and nothing feels more secure than being recognized for the good people we are,” says Dr. Kennedy. True I believe even if we sometimes slam the door.

Dr. Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

The Rise of the Scribes

“We really aren’t taking care of records — we’re taking care of people.” — Dr. Lawrence Weed

What is the purpose of a progress note? Anyone? Yes, you there. “Insurance billing?” Yes, that’s a good one. Anyone else? “To remember what you did?” Excellent. Another? Yes, that’s right, for others to follow along in your care. These are all good reasons for a progress note to exist. But they aren’t the whole story. Let’s start at the beginning.

Charts were once a collection of paper sheets with handwritten notes. Sometimes illegible, sometimes beautiful, always efficient. A progress note back then could be just 10 characters, AK, LN2, X,X,X,X,X (with X’s marking nitrogen sprays). Then came the healthcare K-Pg event: the conversion to EMRs. Those doctors who survived evolved into computer programmers, creating blocks of text from a few keystrokes. But like toddler-sized Legos, the blocks made it impossible to build a note that is nuanced or precise. Worse yet, many notes consisting of blocks from one note added awkwardly to a new note, creating grotesque structures unrecognizable as anything that should exist in nature. Words and numbers, but no information.

Thanks to the eternity of EMR, these creations live on, hideous and useless. They waste not only the server’s energy but also our time. Few things are more maddening than scrolling to reach the bottom of another physician’s note only to find there is nothing there.

Whose fault is this? Anyone? Yes, that’s right, insurers. As there are probably no payers in this audience, let’s blame them. I agree, the crushing burden of documentation-to-get-reimbursed has forced us to create “notes” that add no value to us but add up points for us to get paid for them. CMS, payers, prior authorizations, and now even patients, it seems we are documenting for lots of people except for us. There isn’t time to satisfy all and this significant burden for every encounter is a proximate cause for doctors despair. Until now.

A fully formed, comprehensive, sometimes pretty note that satisfies all audiences. Dr. Larry Weed must be dancing in heaven. It was Dr. Weed who led us from the nicotine-stained logs of the 1950s to the powerful problem-based notes we use today, an innovation that rivals the stethoscope in its impact.

Professor Weed also predicted that computers would be important to capture and make sense of patient data, helping us make accurate diagnoses and efficient plans. Again, he was right. He would surely be advocating to take advantage of AI scribes’ marvelous ability to capture salient data and present it in the form of a problem-oriented medical record.

AI scribes will be ubiquitous soon; I’m fast and even for me they save time. They also allow, for the first time in a decade, to turn from the glow of a screen to actually face the patient – we no longer have to scribe and care simultaneously. Hallelujah. And yet, lest I disappoint you without a twist, it seems with AI scribes, like EMRs we lose a little something too.

Like self-driving cars or ChatGPT-generated letters, they remove cognitive loads. They are lovely when you have to multitask or are trying to recall a visit from hours (days) ago. Using them, you’ll feel faster, lighter, freer, happier. But what’s missing is the thinking. At the end, you have an exquisite note, but you didn’t write it. It has the salient points, but none of the mental work to create it. AI scribes subvert the valuable work of synthesis. That was the critical part of Dr. Weed’s discovery: writing problem-oriented notes helped us think better.

Writing allows for the friction that helps us process what is going on with a patient. It allows for the discovery of diagnoses and prompts plans. When I was an intern, one of my attendings would hand write notes, succinctly showing what he had observed and was thinking. He’d sketch diagrams in the chart, for example, to help illustrate how we’d work though the toxic, metabolic, and infectious etiologies of acute liver failure. Sublime.

The act of writing also helps remind us there is a person attached to these words. Like a handwritten sympathy card, it is intimate, human. Even using our EMR, I’d still often type sentences that help tell the patient’s story. “Her sister just died. Utterly devastated. I’ll forward chart to Bob (her PCP) to check in on her.” Or: “Scratch golfer wants to know why he is getting so many SCCs now. ‘Like bankruptcy, gradually then suddenly,’ I explained. I think I broke through.”

Since we’ve concluded the purpose of a note is mostly to capture data, AI scribes are a godsend. They do so with remarkable quality and efficiency. We’ll just have to remember if the diagnosis is unclear, then it might help to write the note out yourself. And even when done by the AI machine, we might add human touches now and again lest there be no art left in what we do.

“For sale. Sun hat. Never worn.”

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

“We really aren’t taking care of records — we’re taking care of people.” — Dr. Lawrence Weed

What is the purpose of a progress note? Anyone? Yes, you there. “Insurance billing?” Yes, that’s a good one. Anyone else? “To remember what you did?” Excellent. Another? Yes, that’s right, for others to follow along in your care. These are all good reasons for a progress note to exist. But they aren’t the whole story. Let’s start at the beginning.

Charts were once a collection of paper sheets with handwritten notes. Sometimes illegible, sometimes beautiful, always efficient. A progress note back then could be just 10 characters, AK, LN2, X,X,X,X,X (with X’s marking nitrogen sprays). Then came the healthcare K-Pg event: the conversion to EMRs. Those doctors who survived evolved into computer programmers, creating blocks of text from a few keystrokes. But like toddler-sized Legos, the blocks made it impossible to build a note that is nuanced or precise. Worse yet, many notes consisting of blocks from one note added awkwardly to a new note, creating grotesque structures unrecognizable as anything that should exist in nature. Words and numbers, but no information.

Thanks to the eternity of EMR, these creations live on, hideous and useless. They waste not only the server’s energy but also our time. Few things are more maddening than scrolling to reach the bottom of another physician’s note only to find there is nothing there.

Whose fault is this? Anyone? Yes, that’s right, insurers. As there are probably no payers in this audience, let’s blame them. I agree, the crushing burden of documentation-to-get-reimbursed has forced us to create “notes” that add no value to us but add up points for us to get paid for them. CMS, payers, prior authorizations, and now even patients, it seems we are documenting for lots of people except for us. There isn’t time to satisfy all and this significant burden for every encounter is a proximate cause for doctors despair. Until now.

A fully formed, comprehensive, sometimes pretty note that satisfies all audiences. Dr. Larry Weed must be dancing in heaven. It was Dr. Weed who led us from the nicotine-stained logs of the 1950s to the powerful problem-based notes we use today, an innovation that rivals the stethoscope in its impact.

Professor Weed also predicted that computers would be important to capture and make sense of patient data, helping us make accurate diagnoses and efficient plans. Again, he was right. He would surely be advocating to take advantage of AI scribes’ marvelous ability to capture salient data and present it in the form of a problem-oriented medical record.

AI scribes will be ubiquitous soon; I’m fast and even for me they save time. They also allow, for the first time in a decade, to turn from the glow of a screen to actually face the patient – we no longer have to scribe and care simultaneously. Hallelujah. And yet, lest I disappoint you without a twist, it seems with AI scribes, like EMRs we lose a little something too.

Like self-driving cars or ChatGPT-generated letters, they remove cognitive loads. They are lovely when you have to multitask or are trying to recall a visit from hours (days) ago. Using them, you’ll feel faster, lighter, freer, happier. But what’s missing is the thinking. At the end, you have an exquisite note, but you didn’t write it. It has the salient points, but none of the mental work to create it. AI scribes subvert the valuable work of synthesis. That was the critical part of Dr. Weed’s discovery: writing problem-oriented notes helped us think better.

Writing allows for the friction that helps us process what is going on with a patient. It allows for the discovery of diagnoses and prompts plans. When I was an intern, one of my attendings would hand write notes, succinctly showing what he had observed and was thinking. He’d sketch diagrams in the chart, for example, to help illustrate how we’d work though the toxic, metabolic, and infectious etiologies of acute liver failure. Sublime.

The act of writing also helps remind us there is a person attached to these words. Like a handwritten sympathy card, it is intimate, human. Even using our EMR, I’d still often type sentences that help tell the patient’s story. “Her sister just died. Utterly devastated. I’ll forward chart to Bob (her PCP) to check in on her.” Or: “Scratch golfer wants to know why he is getting so many SCCs now. ‘Like bankruptcy, gradually then suddenly,’ I explained. I think I broke through.”

Since we’ve concluded the purpose of a note is mostly to capture data, AI scribes are a godsend. They do so with remarkable quality and efficiency. We’ll just have to remember if the diagnosis is unclear, then it might help to write the note out yourself. And even when done by the AI machine, we might add human touches now and again lest there be no art left in what we do.

“For sale. Sun hat. Never worn.”

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

“We really aren’t taking care of records — we’re taking care of people.” — Dr. Lawrence Weed

What is the purpose of a progress note? Anyone? Yes, you there. “Insurance billing?” Yes, that’s a good one. Anyone else? “To remember what you did?” Excellent. Another? Yes, that’s right, for others to follow along in your care. These are all good reasons for a progress note to exist. But they aren’t the whole story. Let’s start at the beginning.

Charts were once a collection of paper sheets with handwritten notes. Sometimes illegible, sometimes beautiful, always efficient. A progress note back then could be just 10 characters, AK, LN2, X,X,X,X,X (with X’s marking nitrogen sprays). Then came the healthcare K-Pg event: the conversion to EMRs. Those doctors who survived evolved into computer programmers, creating blocks of text from a few keystrokes. But like toddler-sized Legos, the blocks made it impossible to build a note that is nuanced or precise. Worse yet, many notes consisting of blocks from one note added awkwardly to a new note, creating grotesque structures unrecognizable as anything that should exist in nature. Words and numbers, but no information.

Thanks to the eternity of EMR, these creations live on, hideous and useless. They waste not only the server’s energy but also our time. Few things are more maddening than scrolling to reach the bottom of another physician’s note only to find there is nothing there.

Whose fault is this? Anyone? Yes, that’s right, insurers. As there are probably no payers in this audience, let’s blame them. I agree, the crushing burden of documentation-to-get-reimbursed has forced us to create “notes” that add no value to us but add up points for us to get paid for them. CMS, payers, prior authorizations, and now even patients, it seems we are documenting for lots of people except for us. There isn’t time to satisfy all and this significant burden for every encounter is a proximate cause for doctors despair. Until now.

A fully formed, comprehensive, sometimes pretty note that satisfies all audiences. Dr. Larry Weed must be dancing in heaven. It was Dr. Weed who led us from the nicotine-stained logs of the 1950s to the powerful problem-based notes we use today, an innovation that rivals the stethoscope in its impact.

Professor Weed also predicted that computers would be important to capture and make sense of patient data, helping us make accurate diagnoses and efficient plans. Again, he was right. He would surely be advocating to take advantage of AI scribes’ marvelous ability to capture salient data and present it in the form of a problem-oriented medical record.

AI scribes will be ubiquitous soon; I’m fast and even for me they save time. They also allow, for the first time in a decade, to turn from the glow of a screen to actually face the patient – we no longer have to scribe and care simultaneously. Hallelujah. And yet, lest I disappoint you without a twist, it seems with AI scribes, like EMRs we lose a little something too.

Like self-driving cars or ChatGPT-generated letters, they remove cognitive loads. They are lovely when you have to multitask or are trying to recall a visit from hours (days) ago. Using them, you’ll feel faster, lighter, freer, happier. But what’s missing is the thinking. At the end, you have an exquisite note, but you didn’t write it. It has the salient points, but none of the mental work to create it. AI scribes subvert the valuable work of synthesis. That was the critical part of Dr. Weed’s discovery: writing problem-oriented notes helped us think better.

Writing allows for the friction that helps us process what is going on with a patient. It allows for the discovery of diagnoses and prompts plans. When I was an intern, one of my attendings would hand write notes, succinctly showing what he had observed and was thinking. He’d sketch diagrams in the chart, for example, to help illustrate how we’d work though the toxic, metabolic, and infectious etiologies of acute liver failure. Sublime.

The act of writing also helps remind us there is a person attached to these words. Like a handwritten sympathy card, it is intimate, human. Even using our EMR, I’d still often type sentences that help tell the patient’s story. “Her sister just died. Utterly devastated. I’ll forward chart to Bob (her PCP) to check in on her.” Or: “Scratch golfer wants to know why he is getting so many SCCs now. ‘Like bankruptcy, gradually then suddenly,’ I explained. I think I broke through.”

Since we’ve concluded the purpose of a note is mostly to capture data, AI scribes are a godsend. They do so with remarkable quality and efficiency. We’ll just have to remember if the diagnosis is unclear, then it might help to write the note out yourself. And even when done by the AI machine, we might add human touches now and again lest there be no art left in what we do.

“For sale. Sun hat. Never worn.”

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

How to Make Life Decisions

Halifax, Nova Scotia; American Samoa; Queens, New York; Lansing, Michigan; Gurugram, India. I often ask patients where they’re from. Practicing in San Diego, the answers are a geography lesson. People from around the world come here. I sometimes add the more interesting question: How’d you end up here? Many took the three highways to San Diego: the Navy, the defense industry (like General Dynamics), or followed a partner. My Queens patient had a better answer: Super Bowl XXII. On Sunday, Jan. 31st, 1988, the Redskins played the Broncos in San Diego. John Elway and the Broncos lost, but it didn’t matter. “I was scrapin’ the ice off my windshield that Monday morning when I thought, that’s it. I’m done! I drove to the garage where I worked and quit on the spot. Then I drove home and packed my bags.”

In a paper on how to make life decisions, this guy would be Exhibit A: “Don’t overthink it.” That approach might not be suitable for everyone, or for every decision. It might actually be an example of how not to make life decisions (more on that later). But,

The first treatise on this subject was a paper by one Franklin, Ben in 1772. Providing advice to a friend on how to make a career decision, Franklin argued: “My way is to divide half a sheet of paper by a line into two columns; writing over the one Pro and over the other Con.” This “moral algebra” as he called it was a framework to put rigor to a messy, organic problem.

The flaw in this method is that in the end you have two lists. Then what? Do the length of the lists decide? What if some factors are more important? Well, let’s add tools to help. You could use a spreadsheet and assign weights to each variable. Then sum the values and choose based on that. So if “not scraping ice off your windshield” is twice as important as “doubling your rent,” then you’ve got your answer. But what if you aren’t good at estimating how important things are? Actually, most of us are pretty awful at assigning weights to life variables – having bags of money is the consummate example. Seems important, but because of habituation, it turns out to not be sustainable. Note Exhibit B, our wealthy neighbor who owns a Lambo and G-Wagen (AMG squared, of course), who just parked a Cybertruck in his driveway. Realizing the risk of depending on peoples’ flawed judgment, companies instead use statistical modeling called bootstrap aggregating to “vote” on the weights for variables in a prediction. If you aren’t sure how important a new Rivian or walking to the beach would be, a model can answer that for you! It’s a bit disconcerting, I know. I mean, how can a model know what we’d like? Wait, isn’t that how Netflix picks stuff for you? Exactly.

Ok, so why don’t we just ask our friendly personal AI? “OK, ChatGPT, given what you know about me, where can I have it all?” Alas, here we slam into a glass wall. It seems the answer is out there but even our life-changing magical AI tools fail us. Mathematically, it is impossible to have it all. An illustrative example of this is called the economic “impossible trinity problem.” Even the most sophisticated algorithm cannot find an optional solution to some trinities such as fixed foreign exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy. Economists have concluded you must trade off one to have the other two. Impossible trinities are common in economics and in life. Armistead Maupin in his “Tales of the City” codifies it as Mona’s Law, the essence of which is: You cannot have the perfect job, the perfect partner, and the perfect house at the same time. (See Exhibit C, one Tom Brady).

This brings me to my final point, hard decisions are matters of the heart and experiencing life is the best way to understand its beautiful chaos. If making rash judgments is ill-advised and using technology cannot solve all problems (try asking your AI buddy for the square root of 2 as a fraction) what tools can we use? Maybe try reading more novels. They allow us to experience multiple lifetimes in a short time, which is what we need to learn what matters. Reading Dorothea’s choice at the end of “Middlemarch” is a nice example. Should she give up Lowick Manor and marry the penniless Ladislaw or keep it and use her wealth to help others? Seeing her struggle helps us understand how to answer questions like: Should I give up my academic practice or marry that guy or move to Texas? These cannot be reduced to arithmetic. The only way to know is to know as much of life as possible.

My last visit with my Queens patient was our last together. He’s divorced and moving from San Diego to Gallatin, Tennessee. “I’ve paid my last taxes to California, Doc. I decided that’s it, I’m done!” Perhaps he should have read “The Grapes of Wrath” before he set out for California in the first place.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Halifax, Nova Scotia; American Samoa; Queens, New York; Lansing, Michigan; Gurugram, India. I often ask patients where they’re from. Practicing in San Diego, the answers are a geography lesson. People from around the world come here. I sometimes add the more interesting question: How’d you end up here? Many took the three highways to San Diego: the Navy, the defense industry (like General Dynamics), or followed a partner. My Queens patient had a better answer: Super Bowl XXII. On Sunday, Jan. 31st, 1988, the Redskins played the Broncos in San Diego. John Elway and the Broncos lost, but it didn’t matter. “I was scrapin’ the ice off my windshield that Monday morning when I thought, that’s it. I’m done! I drove to the garage where I worked and quit on the spot. Then I drove home and packed my bags.”

In a paper on how to make life decisions, this guy would be Exhibit A: “Don’t overthink it.” That approach might not be suitable for everyone, or for every decision. It might actually be an example of how not to make life decisions (more on that later). But,

The first treatise on this subject was a paper by one Franklin, Ben in 1772. Providing advice to a friend on how to make a career decision, Franklin argued: “My way is to divide half a sheet of paper by a line into two columns; writing over the one Pro and over the other Con.” This “moral algebra” as he called it was a framework to put rigor to a messy, organic problem.

The flaw in this method is that in the end you have two lists. Then what? Do the length of the lists decide? What if some factors are more important? Well, let’s add tools to help. You could use a spreadsheet and assign weights to each variable. Then sum the values and choose based on that. So if “not scraping ice off your windshield” is twice as important as “doubling your rent,” then you’ve got your answer. But what if you aren’t good at estimating how important things are? Actually, most of us are pretty awful at assigning weights to life variables – having bags of money is the consummate example. Seems important, but because of habituation, it turns out to not be sustainable. Note Exhibit B, our wealthy neighbor who owns a Lambo and G-Wagen (AMG squared, of course), who just parked a Cybertruck in his driveway. Realizing the risk of depending on peoples’ flawed judgment, companies instead use statistical modeling called bootstrap aggregating to “vote” on the weights for variables in a prediction. If you aren’t sure how important a new Rivian or walking to the beach would be, a model can answer that for you! It’s a bit disconcerting, I know. I mean, how can a model know what we’d like? Wait, isn’t that how Netflix picks stuff for you? Exactly.

Ok, so why don’t we just ask our friendly personal AI? “OK, ChatGPT, given what you know about me, where can I have it all?” Alas, here we slam into a glass wall. It seems the answer is out there but even our life-changing magical AI tools fail us. Mathematically, it is impossible to have it all. An illustrative example of this is called the economic “impossible trinity problem.” Even the most sophisticated algorithm cannot find an optional solution to some trinities such as fixed foreign exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy. Economists have concluded you must trade off one to have the other two. Impossible trinities are common in economics and in life. Armistead Maupin in his “Tales of the City” codifies it as Mona’s Law, the essence of which is: You cannot have the perfect job, the perfect partner, and the perfect house at the same time. (See Exhibit C, one Tom Brady).

This brings me to my final point, hard decisions are matters of the heart and experiencing life is the best way to understand its beautiful chaos. If making rash judgments is ill-advised and using technology cannot solve all problems (try asking your AI buddy for the square root of 2 as a fraction) what tools can we use? Maybe try reading more novels. They allow us to experience multiple lifetimes in a short time, which is what we need to learn what matters. Reading Dorothea’s choice at the end of “Middlemarch” is a nice example. Should she give up Lowick Manor and marry the penniless Ladislaw or keep it and use her wealth to help others? Seeing her struggle helps us understand how to answer questions like: Should I give up my academic practice or marry that guy or move to Texas? These cannot be reduced to arithmetic. The only way to know is to know as much of life as possible.

My last visit with my Queens patient was our last together. He’s divorced and moving from San Diego to Gallatin, Tennessee. “I’ve paid my last taxes to California, Doc. I decided that’s it, I’m done!” Perhaps he should have read “The Grapes of Wrath” before he set out for California in the first place.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Halifax, Nova Scotia; American Samoa; Queens, New York; Lansing, Michigan; Gurugram, India. I often ask patients where they’re from. Practicing in San Diego, the answers are a geography lesson. People from around the world come here. I sometimes add the more interesting question: How’d you end up here? Many took the three highways to San Diego: the Navy, the defense industry (like General Dynamics), or followed a partner. My Queens patient had a better answer: Super Bowl XXII. On Sunday, Jan. 31st, 1988, the Redskins played the Broncos in San Diego. John Elway and the Broncos lost, but it didn’t matter. “I was scrapin’ the ice off my windshield that Monday morning when I thought, that’s it. I’m done! I drove to the garage where I worked and quit on the spot. Then I drove home and packed my bags.”

In a paper on how to make life decisions, this guy would be Exhibit A: “Don’t overthink it.” That approach might not be suitable for everyone, or for every decision. It might actually be an example of how not to make life decisions (more on that later). But,

The first treatise on this subject was a paper by one Franklin, Ben in 1772. Providing advice to a friend on how to make a career decision, Franklin argued: “My way is to divide half a sheet of paper by a line into two columns; writing over the one Pro and over the other Con.” This “moral algebra” as he called it was a framework to put rigor to a messy, organic problem.

The flaw in this method is that in the end you have two lists. Then what? Do the length of the lists decide? What if some factors are more important? Well, let’s add tools to help. You could use a spreadsheet and assign weights to each variable. Then sum the values and choose based on that. So if “not scraping ice off your windshield” is twice as important as “doubling your rent,” then you’ve got your answer. But what if you aren’t good at estimating how important things are? Actually, most of us are pretty awful at assigning weights to life variables – having bags of money is the consummate example. Seems important, but because of habituation, it turns out to not be sustainable. Note Exhibit B, our wealthy neighbor who owns a Lambo and G-Wagen (AMG squared, of course), who just parked a Cybertruck in his driveway. Realizing the risk of depending on peoples’ flawed judgment, companies instead use statistical modeling called bootstrap aggregating to “vote” on the weights for variables in a prediction. If you aren’t sure how important a new Rivian or walking to the beach would be, a model can answer that for you! It’s a bit disconcerting, I know. I mean, how can a model know what we’d like? Wait, isn’t that how Netflix picks stuff for you? Exactly.

Ok, so why don’t we just ask our friendly personal AI? “OK, ChatGPT, given what you know about me, where can I have it all?” Alas, here we slam into a glass wall. It seems the answer is out there but even our life-changing magical AI tools fail us. Mathematically, it is impossible to have it all. An illustrative example of this is called the economic “impossible trinity problem.” Even the most sophisticated algorithm cannot find an optional solution to some trinities such as fixed foreign exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy. Economists have concluded you must trade off one to have the other two. Impossible trinities are common in economics and in life. Armistead Maupin in his “Tales of the City” codifies it as Mona’s Law, the essence of which is: You cannot have the perfect job, the perfect partner, and the perfect house at the same time. (See Exhibit C, one Tom Brady).

This brings me to my final point, hard decisions are matters of the heart and experiencing life is the best way to understand its beautiful chaos. If making rash judgments is ill-advised and using technology cannot solve all problems (try asking your AI buddy for the square root of 2 as a fraction) what tools can we use? Maybe try reading more novels. They allow us to experience multiple lifetimes in a short time, which is what we need to learn what matters. Reading Dorothea’s choice at the end of “Middlemarch” is a nice example. Should she give up Lowick Manor and marry the penniless Ladislaw or keep it and use her wealth to help others? Seeing her struggle helps us understand how to answer questions like: Should I give up my academic practice or marry that guy or move to Texas? These cannot be reduced to arithmetic. The only way to know is to know as much of life as possible.

My last visit with my Queens patient was our last together. He’s divorced and moving from San Diego to Gallatin, Tennessee. “I’ve paid my last taxes to California, Doc. I decided that’s it, I’m done!” Perhaps he should have read “The Grapes of Wrath” before he set out for California in the first place.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Rethinking the Rebels

Each month I set out on an expedition to find a topic for this column. I came across a new book Rebel Health by Susannah Fox that I thought might be a good one. It’s both a treatise on the shortcomings of healthcare and a Baedeker for patients on how to find their way to being better served. Her argument is that many patients’ needs are unmet and their conditions are often invisible to us in mainstream healthcare. We fail to find solutions to help them. Patients would benefit from more open access to their records and more resources to take control of their own health, she argues. A few chapters in, I thought, “Oh, here we go, another diatribe on doctors and how we care most about how to keep patients in their rightful, subordinate place.” The “Rebel” title is provocative and implies patients need to overthrow the status quo. Well, I am part of the establishment. I stopped reading. This book doesn’t apply to me, I thought.

After all, I’m a healthcare progressive, right? My notes and results have been open for years. I encourage shared decision-making and try to empower patients as much as treat them. The idea that I or my colleagues are unwilling to do whatever is necessary to meet our patients’ needs was maddening. We dedicate our lives to it. My young daughter often greets me in the morning by asking if I’ll be working tonight. Most nights, I am — answering patient messages, collaborating with colleagues to help patients, keeping up with medical knowledge. I was angry at what felt like unjust criticism, especially that we’d neglect patients because their problems are not obvious or worse, there is not enough money to be made helping them. Harrumph.

That’s when I realized the best thing for me was to read the entire book and digest the arguments. I pride myself on being well-read, but I fall into a common trap: the podcasts I listen to, news I consume, and books I read mostly affirm my beliefs. It is a healthy choice to seek dispositive data and contrasting stories rather than always feeding our personal opinions.

Rebel Health was not written by Robespierre. It was penned by a thoughtful, articulate patient advocate with over 20 years experience. She has far more bona fides than I could achieve in two lifetimes. In the book, she reminds us that She describes four patient archetypes: seekers, networkers, solvers, and champions, and offers a four-quadrant model to visualize how some patients are unhelped by our current healthcare system. She advocates for frictionless, open access to health data and tries to inspire patients to connect, innovate, and create to fill the voids that exist in healthcare. We have come a long way from the immured system of a decade ago; much of that is the result of patient advocates. But healthcare is still too costly, too fragmented and too many patients unhelped. “Community is a superpower,” she writes. I agree, we should assemble all the heroes in the universe for this challenge.

Fox also tells stories of patients who solved diagnostic dilemmas through their own research and advocacy. I thought of my own contrasting experiences of patients whose DIY care was based on misinformation and how their false confidence led to poorer outcomes for them. I want to share with her readers how physicians feel hurt when patients question our competence or place the opinion of an adversarial Redditor over ours. Physicians are sometimes wrong and often in doubt. Most of us care deeply about our patients regardless of how visible their diagnosis or how easy they are to appease.

We don’t have time to engage back-and-forth on an insignificantly abnormal test they find in their open chart or why B12 and hormone testing would not be helpful for their disease. It’s also not the patients’ fault. Having unfettered access to their data might add work, but it also adds value. They are trying to learn and be active in their care. Physicians are frustrated mostly because we don’t have time to meet these unmet needs. Everyone is trying their best and we all want the same thing: patients to be satisfied and well.

As for learning the skill of being open-minded, an excellent reference is Adam Grant’s Think Again. It’s inspiring and instructive of how we can all be more open, including how to have productive arguments rather than fruitless fights. We live in divisive times. Perhaps if we all put in effort to be open-minded, push down righteous indignation, and advance more honest humility we’d all be a bit better off.